Striving for accuracy attenuates the positive relationship between cyberbullying bystanders’ dispositional empathy and tendencies to help victims

Vol.20,No.1(2026)

Empathy is a key predictor of bystanders’ helping behaviors, yet its role in cyberbullying contexts has yielded inconsistent findings. This study investigated whether accuracy motivation, the drive to form correct and well-reasoned judgments, moderates the relationship between dispositional empathy and helping tendencies among cyberbullying bystanders. In Study 1, 164 Taiwanese undergraduates (61 males, 100 females, 3 unknown; Mage = 22.96, SD = 14.25) read a cyberbullying scenario and completed measures of empathy, helping tendencies, and need for cognition (NFC), a personality trait reflecting enjoyment of cognitively effortful tasks, widely used as a proxy for accuracy motivation. Results showed that the positive association between empathy and helping tendencies was weaker among participants with higher NFC scores (i.e., higher accuracy motivation). In Study 2, 180 undergraduates (67 males, 113 females; Mage = 20.96, SD = 5.44) were randomly assigned to either control or high accuracy motivation group. Findings revealed that, for participants in the control group, empathy predicted helping through increased feelings of responsibility. This mediational pathway was not observed in the high accuracy motivation condition. These findings suggest that accuracy motivation may attenuate the influence of empathy on helping behavior in cyberbullying contexts. Theoretically, this provides a possible explanation for the mixed results observed in prior research. Practically, it highlights the importance of encouraging individuals to prioritize providing timely support in cyberbullying incidents, rather than becoming overly focused on verifying the authenticity of online messages.

empathy; accuracy motivation; cyberbullying; helping behaviours; need for cognition

Cheng-Hong Liu

Department of Educational Psychology and Counseling, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu City, Taiwan

Cheng-Hong Liu is an educational psychologist specializing in adolescent research and quantitative research methods. His research interests include motivation and emotion, self, attitudes, and cyberbullying. He is particularly interested in studying how to increase the propensity and behavior of bystanders to actively assist victims of cyberbullying and how to maintain and improve student’s motivation and well-being in learning.

Fa-Chung Chiu

Department of Counseling, Chinese Culture University, Taipei, Taiwan

Fa-Chung Chiu is a professor in the Department of Counseling, Chinese Culture University, Taiwan, He is an educational psychologist and cognitive psychologist specializing in creativity, humor, emotion, positive psychology, and education research.

Po-Sheng Huang

Graduate Institute of Digital Learning and Education & Empower Vocational Education Research Center, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taipei, Taiwan

Po-Sheng Huang is an educational psychologist and cognitive psychologist, specializing in adolescent research and quantitative research. His research interests include creativity, motivation and emotion, interpersonal communication, the impact of digital environments on human behavior, and cyberbullying. He is particularly interested in how to effectively facilitate adolescents' creative expression, the quality of interpersonal interactions, and learning performance.

Ting-Huan Lin

Department of Educational Psychology and Counseling, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu City, Taiwan

Ting-Huan Lin received her M.S. in Psychology from National Tsing Hua University. She is currently working with Dr. Liu and his teammates. Broadly, she is interested in factors that may affect helping behaviors of bystanders.

Chia-Lin Chang

Department of Educational Psychology and Counseling, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu City, Taiwan

Chia-Lin Chang is a master’s graduate in the Department of Educational Psychology and Counseling at National Tsing Hua University. In general, she works and researches in the area of cyberbullying.

Ang, R. P., Li, X., & Seah, S. L. (2017). The role of normative beliefs about aggression in the relationship between empathy and cyberbullying. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(8), 1138–1152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022116678928

Balakrishnan, V., & Fernandez, T. (2018). Self-esteem, empathy and their impacts on cyberbullying among young adults. Telematics and Informatics, 35(7), 2028–2037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.07.006

Bastiaensens, S., Vandebosch, H., Poels, K., Van Cleemput, K., DeSmet, A., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2014). Cyberbullying on social network sites. An experimental study into bystanders’ behavioural intentions to help the victim or reinforce the bully. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 259–271. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.036

Bayes, R., Druckman, J. N., Goods, A., & Molden, D. C. (2020). When and how different motives can drive motivated political reasoning. Political Psychology, 41(5), 1031–1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12663

Biesanz, J. C., & Human, L. J. (2010). The cost of forming more accurate impressions: Accuracy-motivated perceivers see the personality of others more distinctively but less normatively than perceivers without an explicit goal. Psychological Science, 21(4), 589–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610364121

Bjärehed, M., Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Gini, G. (2019). Mechanisms of moral disengagement and their Associations with indirect Bullying, direct bullying, and pro-aggressive bystander behavior. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 40, Article 027243161882474. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431618824745

Bravo, M. J., Galiana, L., Rodrigo, M. F., Navarro-Pérez, J. J., & Oliver, A. (2020). An adaptation of the Critical Thinking Disposition Scale in Spanish youth. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 38, Article 100748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100748

Brody, N., & Vangelisti, A. L. (2016). Bystander intervention in cyberbullying. Communication Monographs, 83(1), 94–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2015.1044256

Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1982). The need for cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.116

Chang, C. L., Liu, C. H., Yin, X. R., Chen, K. M., & Lin, T. H. (2025). Effects of normative beliefs about stopping cyberbullying on bystander helping behavior. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 18, Article 100633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2025.100633

Chapin, J., & Coleman, G. (2017). Children and adolescent victim blaming. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 23(4), 438–440. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000282

Chen, S., & Chaiken, S. (1999). The heuristic-systematic model in its broader context. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp.73–96). Guilford Press.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cronley, M. L., Mantel, S. P., & Kardes, F. R. (2010). Effects of accuracy motivation and need to evaluate on mode of attitude formation and attitude–behavior consistency. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20(3), 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2010.06.003

Darley, J. M., & Latane, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(4, Pt.1), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025589

Davis, M. H. (2015). Empathy and prosocial behavior. In D. A. Schroeder & W. G. Graziano (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of prosocial behavior (pp. 282–306). Oxford University Press. http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399813.013.026

DeSmet, A., Bastiaensens, S., Van Cleemput, K., Poels, K., Vandebosch, H., Cardon, G., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2016). Deciding whether to look after them, to like it, or leave it: A multidimensional analysis of predictors of positive and negative bystander behavior in cyberbullying among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 398–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.051

Dimberg, U., & Thunberg, M. (2012). Empathy, emotional contagion, and rapid facial reactions to angry and happy facial expressions. PsyCh Journal, 1(2), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.4

Dodaj, A., Sesar, K., Barisic, M., & Pandza, M. (2012). The effect of empathy on involving in bullying behavior. Central European Journal of Paediatrics, 9(1), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.5457/p2005-114.66

Eisenberg, N., Shea, C. L., Carlo, G., & Knight, G. P. (1991). Empathy-related responding and cognition: A ‘‘chicken and the egg’’ dilemma. In W. M. Kurtines (Ed.), Handbook of moral behavior and development: Vol. 2. research (pp. 63–88). Erlbaum.

Ford, T. E., & Kruglanski, A. W. (1995). Effects of epistemic motivations on the use of accessible constructs in social judgment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(9), 950–962. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295219009

Freis, S. D., & Gurung, R. A. R. (2013). A Facebook analysis of helping behavior in online bullying. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(1), 11–19. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0030239

Garland, T. S., Policastro, C., Richards, T. N., & Miller, K. S. (2017). Blaming the victim: University student attitudes toward bullying. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 26(1), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2016.1194940

Garrett, R. K., & Weeks, B. E. (2017). Epistemic beliefs’ role in promoting misperceptions and conspiracist ideation. PLoS ONE, 12(9), Article e0184733. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184733

González, R., & Lay, S. (2017). Sense of responsibility and empathy: Bridging the gap between attributions and helping behaviours. In E. van Leeuwen & H. Zagefka (Eds.), Intergroup helping (pp. 331–347). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-53026-0_16

Haddock, A. D., & Jimerson, S. R. (2017). An examination of differences in moral disengagement and empathy among bullying participant groups. Journal of Relationships Research, 8(15), Article e15. http://doi.org/10.1017/jrr.2017.15

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Jenkins, L. N., & Nickerson, A. B. (2019). Bystander intervention in bullying: Role of social skills and gender. Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(2), 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431617735652

Kazerooni, F., Taylor, S. H., Bazarova, N. N., & Whitlock, J. (2018). Cyberbullying bystander intervention: The number of offenders and retweeting predict likelihood of helping a cyberbullying victim. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(3), 146–162. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy005

Kennedy, R. S. (2019). Bullying trends in the United States: A meta-regression. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(4), 914–927. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019888555

Knauf, R., Eschenbeck, H., & Hock, M. (2018). Bystanders of bullying: Social-cognitive and affective reactions to school bullying and cyberbullying. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 12(4), Article 3. http://dx.doi.org/10.5817/CP2018-4-3

Koehler, C., & Weber, M. (2018). ”Do I really need to help?!” Perceived severity of cyberbullying, victim blaming, and bystanders’ willingness to help the victim. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 12(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2018-4-4

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

Kunda, Z. (1999). Social cognition: Making sense of people. MIT Press.

Lambe, L. J., Cioppa, V. D., Hong, I. K., & Craig, W. M. (2019). Standing up to bullying: A social ecological review of peer defending in offline and online contexts. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 51–74. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.05.007

Lins de Holanda Coelho, G., Hanel, P. H. P., & Wolf, L. J. (2020). The very efficient assessment of need for cognition: Developing a six-item version. Assessment, 27(8), 1870–1885. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191118793208

Liu, C. H. (2017). Evaluating arguments during instigations of defence motivation and accuracy motivation. British Journal of Psychology, 108(2), 296–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12196

Liu, C. H., Lee, H. W., Huang, P. S., Chen, H. C., & Sommers, S. (2016). Do incompatible arguments cause extensive processing in the evaluation of arguments? The role of congruence between argument compatibility and argument quality. British Journal of Psychology, 107(1), 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12133

Liu, C. H., Yin, X. R., & Huang, P. S. (2021). Cyberbullying: Effect of emergency perception on the helping tendencies of bystanders. Telematics and Informatics, 62, Article 101627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101627

Machackova, H., & Pfetsch, J. (2016). Bystanders’ responses to offline bullying and cyberbullying: The role of empathy and normative beliefs about aggression. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12277

Machackova, H., Dedkova, L., & Mezulanikova, K. (2015). Brief report: The bystander effect in cyberbullying incidents. Journal of Adolescence, 43(1), 96–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.05.010

Nickerson, A. B., Aloe, A. M., & Werth, J. M. (2015). The relation of empathy and defending in bullying: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Review, 44(4), 372–390. http://doi.org/10.17105/spr-15-0035.1

Nir, L. (2011). Motivated reasoning and public opinion perception. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(3), 504–532. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfq076

Obermaier, M., Fawzi, N., & Koch, T. (2016). Bystanding or standing by? How the number of bystanders affects the intention to intervene in cyberbullying. New Media & Society, 18(8), 1491–1507. http://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814563519

Petty, R. E., & Wegener, D. T. (1999). The elaboration likelihood model: Current status and controversies. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp. 41–72). Guilford Press.

Poon, K. T., & Chen, Z. (2015). How does the source of rejection perceive innocent victims? The Journal of Social Psychology, 155(5), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2015.1061972

Raskauskas, J., & Stoltz, A. D. (2007). Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 43(3), 564–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.564

Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

Sosu, E. M. (2013). The development and psychometric validation of a Critical Thinking Disposition Scale. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 9, 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2012.09.002

Spreng, R. N., McKinnon, M. C., Mar, R. A., & Levine, B. (2009). The Toronto empathy questionnaire: Scale development and initial validation of a factor-analytic solution to multiple empathy measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(1), 62–71. http://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802484381

Stapel, D. A., Koomen, W., & Zeelenberg, M. (1998). The impact of accuracy motivation on interpretation, comparison, and correction processes: Accuracy × knowledge accessibility effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(4), 878–893. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.4.878

Steffgen, G., König, A., Pfetsch, J., & Melzer, A. (2011). Are cyberbullies less empathic? Adolescents' cyberbullying behavior and empathic responsiveness. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(11), 643–648. http://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0445

Thompson, E. P., Roman, R. J., Moskowitz, G. B., Chaiken, S., & Bargh, J. A. (1994). Accuracy motivation attenuates covert priming: The systematic reprocessing of social information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(3), 474–489. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.3.474

Van Cleemput, K., Vandebosch, H., & Pabian, S. (2014). Personal characteristics and contextual factors that determine “helping,” “joining in,” and “doing nothing” when witnessing cyberbullying. Aggressive Behavior, 40(5), 383–1396. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21534

van Noorden, T. H. J., Haselager, G. J. T., Cillessen, A. H. N., & Bukowski, W. M. (2015). Empathy and involvement in bullying in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(3), 637–357. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0135-6

Ybarra, M. L., Diener-West, M., & Leaf, P. J. (2007). Examining the overlap in Internet harassment and school bullying: Implications for school intervention. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(6), S42–S50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.004

Zhao, X., Li, X., Song, Y., & Shi, W. (2019). Autistic traits and prosocial behaviour in the general population: Test of the mediating effects of trait empathy and state empathic concern. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(10), 3925–3938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3745-0

Zhao, Y., Chu, X., & Rong, K. (2023). Cyberbullying experience and bystander behavior in cyberbullying incidents: The serial mediating roles of perceived incident severity and empathy. Computers in Human Behavior, 138, Article 107484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107484

Zych, I., Baldry, A. C., Farrington, D. P., & Llorent, V. J. (2019). Are children involved in cyberbullying low on empathy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of research on empathy versus different cyberbullying roles. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.03.004

Zych, I., Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2019). Empathy and callous–unemotional traits in different bullying roles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 20(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016683456

Authors´ Contribution

Cheng-Hong Liu: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, funding acquisition. Fa-Chung Chiu: conceptualization, data curation. Po-Sheng Huang: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, funding acquisition. Ting-Huan Lin: data curation. Chia-Lin Chang: data curation.

Editorial record

First submission received:

April 9, 2025

Revisions received:

October 17, 2025

January 11, 2026

Accepted for publication:

January 12, 2026

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

Cyberbullying, also called “online bullying,” is defined as the use of electronic devices or network communication technology by individuals or groups to transmit information to a specific target or group, with the deliberate intent to attack (Ang et al., 2017; Balakrishnan & Fernandez, 2018; Brody & Vangelisti, 2016; Smith et al., 2008). Cyberbullying is a growing problem (Kennedy, 2019), and many cyberbullying victims experience considerable stress and even physical and mental health problems (Raskauskas & Stoltz, 2007; Ybarra et al., 2007). Thus, identifying the factors that can reduce cyberbullying is essential. Given that the willingness of cyberbullying bystanders to help victims is a key factor in reducing the occurrence of cyberbullying, research has focused on bystanders’ perspectives to understand what factors are associated with enhancing their helping behaviors (e.g., Bastiaensens et al., 2014; Kazerooni et al., 2018; Machackova et al., 2015; Obermaier et al., 2016).

Findings are inconsistent on whether the dispositional empathy of cyberbullying bystanders constitutes a vital factor in enhancing helping behaviors (see Lambe et al., 2019; Zych, Baldry et al., 2019). Specifically, dispositional empathy refers to an individual’s ability to generate consistent emotional responses to other people’s emotional states or situations (Eisenberg et al., 1991, p. 65), encompassing an understanding of others’ emotions (cognitive empathy) and the ability to share their emotional states (emotional empathy; Steffgen et al., 2011; Y. Zhao et al., 2023; Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019). Prosocial behavior evidence generally indicates that a person with higher dispositional empathy is more likely to exhibit helping behaviors toward individuals in crisis situations (see Davis, 2015). Studies on offline bullying also note that people with higher dispositional empathy tend to engage in more helping behaviors and exhibit less aggressive behaviors toward targets of bullying (Haddock & Jimerson, 2017; Lambe et al., 2019; Machackova & Pfetsch, 2016; Nickerson et al., 2015; van Noorden et al., 2015; Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019). However, the strong, consistent positive relationship observed in offline contexts has not been reliably replicated in the field of cyberbullying research. Although several cyberbullying studies have suggested that bystanders with higher dispositional empathy are more likely to help victims (Freis & Gurung, 2013; Lambe et al., 2019; Machackova & Pfetsch, 2016; Machackova et al., 2015; Van Cleemput et al., 2014; Y. Zhao et al., 2023, who, for instance, found a correlation between a combined measure of cognitive and emotional empathy and bystander support), few studies have made concrete observations (see Balakrishnan & Fernandez, 2018, p.5). Conversely, other research indicates that compared to offline bullying, bystanders’ dispositional empathy in cyberbullying is a less potent predictor of supportive bystander behaviors such as defending, reporting, and comforting the victim (DeSmet et al., 2016). Furthermore, empirical evidence from both DeSmet et al. (2016) and Balakrishnan and Fernandez (2018) suggests that in cyberbullying, empathy may even fail to have a significant predictive effect on helping behaviors. This implies that the relationship between dispositional empathy and cyberbullying bystanders’ helping behaviors is inconsistent across studies. This inconsistency represents a critical theoretical paradox that limits the predictive utility of empathy in the online environment, demanding further investigation into its boundary conditions. In other words, in the context of cyberbullying, research is warranted to clarify the relationship between dispositional empathy and bystanders’ helping behaviors (Zych, Baldry et al., 2019, p. 21), and to identify factors that may moderate this relationship (Lambe et al., 2019).

Unlike offline bullies, cyberbullies mainly attack the victim by sending messages over the Internet. In these messages, cyberbullies often indicate that the victims are at fault for being bullied because of their own mistakes, inappropriate speeches, actions, attitudes, and traits (Bjärehed et al., 2019; Chapin & Coleman, 2017; Garland et al., 2017; Koehler & Weber, 2018; Poon et al., 2015). However, unlike in many offline situations, cyberbullying bystanders are often not physically present during the incident (Machackova et al., 2015). They frequently learn about it indirectly, for instance, by seeing the messages shared or forwarded online; therefore, verifying the messages’ authenticity is often challenging. This situation establishes cyberbullying as fundamentally an information-processing problem for the bystander. We postulated that in this context, the degree to which cyberbullying bystanders are motivated to understand these messages correctly (i.e., accuracy motivation; Bayes et al., 2020; Biesanz & Human, 2010; Chen & Chaiken, 1999) is a key reason for the inconsistent relationship between dispositional empathy and helping behaviors, which has been overlooked in previous cyberbullying studies. Our unique theoretical perspective is the proposition that simply possessing empathy may be insufficient when bystanders are driven by an epistemic motivation to discern the truth of a complex online accusation. This exploration may offer crucial practical insights into why highly empathetic individuals fail to assist, which can inform the development of targeted intervention methods to promote helping behavior.

Specifically, drawing on the Heuristic-Systematic Model (HSM; Chen & Chaiken, 1999) as our integrated theoretical framework, we argue that the cyberbullying bystander’s response is determined by their processing path: heuristic (cursory, relying on shortcuts) or systematic (effortful, scrutinizing evaluation). A critical factor influencing engagement in either path is the individual’s accuracy motivation (Liu, 2017), the desire to hold correct attitudes and beliefs (Biesanz & Human, 2010; Chen & Chaiken, 1999; Kunda, 1990, 1999; Petty & Wegener, 1999). Research shows that people with higher accuracy motivation process information more deeply and carefully, grounding their attitudes and behaviors in whether the information is factual and reasonable (Bayes et al., 2020; Chen & Chaiken, 1999; Liu, 2017; Liu et al., 2016). Consequently, bystanders with higher accuracy motivation are more likely to engage in the systematic path, focusing on the message’s accuracy and processing it deeply. Conversely, those with lower accuracy motivation process the information more cursorily, relying instead on heuristic cues.

Thus, in the HSM context, we hypothesize that a cyberbullying bystander’s accuracy motivation moderates the effect of dispositional empathy on helping behavior. When cyberbullying bystanders with lower accuracy motivation possess higher dispositional empathy, they are more likely to empathize with the victim’s situation, just as bystanders in general crisis situations or offline bullying situations are likely to do (Davis, 2015; Dimberg & Thunberg, 2012; X. Zhao, 2019). This represents the heuristic processing path, where the emotional cue (empathy) acts as an affective heuristic and immediately strengthens their intention to aid the victim out of feelings of responsibility. This path is supported by literature linking empathy to enhanced feelings of responsibility (González & Lay, 2017; Knauf et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2021), as more empathetic individuals are prone to internalizing the moral obligation and accepting responsibility for intervention (Chang et al., 2025; Jenkins & Nickerson, 2019). By contrast, bystanders with higher accuracy motivation are compelled into the systematic processing path, even when possessing high empathy. They must process cyberbullying messages deeply and carefully, deciding whether to intervene based on their perception of the message’s veracity and reasonableness. Since verifying the authenticity of online claims is often difficult, this ambiguity leads to cognitive deliberation, essentially suspending both judgment and action. Consequently, the systematic processing path inhibits the effect of dispositional empathy on enhancing feelings of responsibility and helping tendencies. Thus, the positive relationship between dispositional empathy and helping tendencies is weaker for those with higher accuracy motivation.

It is important to note that while dispositional empathy comprises both affective and cognitive components, we chose to emphasize affective empathy for several reasons. First, most previous research consistently shows a stronger association between emotional empathy and helping or aggressive behaviors toward bullying victims compared to cognitive empathy (see Ang et al., 2017; Dodaj et al., 2012; Machackova, 2016; van Noorden et al., 2015). Consequently, several cyberbullying studies have exclusively measured affective empathy (e.g., Balakrishnan & Fernandez, 2018; DeSmet et al., 2016). Second, affective empathy better aligns with our core theoretical claim regarding the heuristic processing path, where the emotional cue acts as an affective heuristic. Therefore, our measurement of dispositional empathy primarily focused on affective empathy.

Present Study

We investigated whether accuracy motivation moderates the relationship between the dispositional empathy of cyberbullying bystanders and their helping tendencies and examined the relevant mechanisms. In Study 1, we measured accuracy motivation by assessing the participants’ need for cognition, a personality trait that reflects enjoyment of effortful cognitive activities (Cacioppo & Petty, 1982). The higher individuals’ need for cognition is, the more likely they are to engage in effortful, in-depth processing and cautious judgments of the information to which they are exposed. The need for cognition is correlated with accuracy motivation and has been used in certain studies to represent accuracy motivation. It is considered equivalent to the experimental manipulation of accuracy motivation (see Nir, 2011). We expected that the strength of the positive relationship between participants’ dispositional empathy and helping tendencies to cyberbullying victims would decrease as the need for cognition increases. In Study 2, we manipulated accuracy motivation on the basis of whether participants were reminded of the importance of correctly understanding online events and whether they needed to explain the reasoning for their questionnaire responses (Cronley et al., 2010; Ford & Kruglanski, 1995; Liu, 2017; Stapel et al., 1998; Thompson et al., 1994). We expected to observe a weaker positive relationship between dispositional empathy and helping tendencies in the high accuracy motivation group than in the control group. We also examined whether feelings of responsibility to help mediated the moderating effect of accuracy motivation in the relationship between dispositional empathy and helping tendencies. Both studies followed the ethical principles established by the APA and were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of National Tsing Hua University in Taiwan.

Study 1

Method

Participants

An a priori power analysis for a multiple regression with three predictors (dispositional empathy, need for cognition, and dispositional empathy × need for cognition) suggested that we needed 77 participants to achieve .80 power for detecting a medium-sized effect (f2 = .15) with an α of .05. This effect size estimate was based on Cohen’s (1988) standard conventions for behavioral science research. A convenience sampling method was employed to recruit 181 participants (61 male, 117 female, 3 unknown; Mage = 22.96, SD = 14.25, range = 18–37) from two universities in northern Taiwan between January 2023 and July 2023. The recruitment was conducted via classroom announcements and oral invitations during regular lecture hours. To be eligible, participants had to be enrolled university students aged 18 or above. Participation was entirely voluntary. Each participant received a convenience store voucher worth NT$100 (about US$3.5). Eight participants failing attention checks and seven failing to complete all the measures were excluded from the analysis, leaving a final sample of 164.

To assess the statistical power for our key hypothesis, a post hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted using G*Power (Version 3.1). We utilized the F-test for “Linear multiple regression: Fixed model, R² increase” to specifically determine the power to detect the contribution of the interaction term. With our final sample of 164 participants, and power set at .80 (α = .05), the analysis revealed that our study was sensitive enough to detect a minimum effect size of f² = .048 for the interaction. According to Cohen’s (1988) conventions, this is considered a small effect, indicating that our study was adequately powered to detect the hypothesized interaction.

Procedure

Data were collected in group sessions, with approximately 20–30 participants per session. Following the recruitment announcements, those interested in the study remained in their classrooms after lectures to complete the survey in a paper-and-pencil format. In addition to demographic questions and filler scales (e.g., Self-Esteem Scale; see Supplementary Materials), participants first completed the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire and the Need for Cognition Scale (see Measures).

Next, participants read an adaptation of a real-life cyberbullying incident. The following description is a summary of the scenario presented to participants (see Appendix for the full text in both English and the original language). In the scenario, a mother was involved in a car accident while driving, leaving her 3-year-old daughter paralyzed from the neck down. Later, the mother would often share videos of her daughter’s recovery on the Internet, asking Internet users to support her. However, some users began to question the mother’s motives and condemn for several reasons. First, some users noted that the mother had been negligent and had made serious mistakes in driving carelessly and failing to secure her daughter in a booster seat, which they believed led to the accident and the daughter’s injuries. Second, Internet users argued that instead of following the rules when applying for a special government-approved operation to save her daughter’s life, the mother attempted to rally the Internet into pushing her daughter to the front of the line. Third, some people noted that after the daughter returned home from the hospital, she was taken to a charity fundraising event by her mother although she was feeling unwell. Consequently, the girl developed a high fever and was immediately admitted to the intensive care unit. Moreover, a few months after the girl’s recovery, the woman received praise and an award for caring for her daughter. Internet users claimed that the woman used her daughter for Internet clout and attention. The mother stated that she was distressed by these comments and tried to explain her side of the story. However, the controversy continued.

After reading the extract, participants completed the survey, which included filler scales (e.g., aggressive tendencies toward the victim; see Supplementary Materials) and measures of their tendencies to help the victim (see Measures). Finally, participants were debriefed, thanked, and dismissed.

Measures

Dispositional Empathy. Participants completed the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (Spreng et al., 2009) on a 5-point scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). This questionnaire consists of 16 items measuring emotional empathy (e.g., It upsets me to see someone being treated disrespectfully; α = .82). In the current study, the scale demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .82). The final score was computed by averaging the items (after reverse-scoring the appropriate items), with higher scores indicating higher levels of dispositional empathy.

Need for Cognition. Participants completed a six-item version of the Need for Cognition Scale (Lins de Holanda Coelho et al., 2020) on a 7-point scale from 1 (extremely uncharacteristic of me) to 7 (extremely characteristic of me). The six items possessed high internal consistency (α = .85; e.g., I would prefer complex to simple problems). The final score was computed as the average across the six items, where higher scores reflect greater accuracy motivation.

Helping Tendencies. Participants completed four items measuring their tendencies to comfort and support the mother (e.g., If a friend questions or condemns the mother, I am more likely to speak up for the mother). These items were adapted from Liu et al.’s (2021) items measuring participants’ intentions to help another victim of cyberbullying. The four items possessed high internal consistency (α = .89). The final score was calculated by averaging the items, with higher scores indicating a greater inclination to provide support.

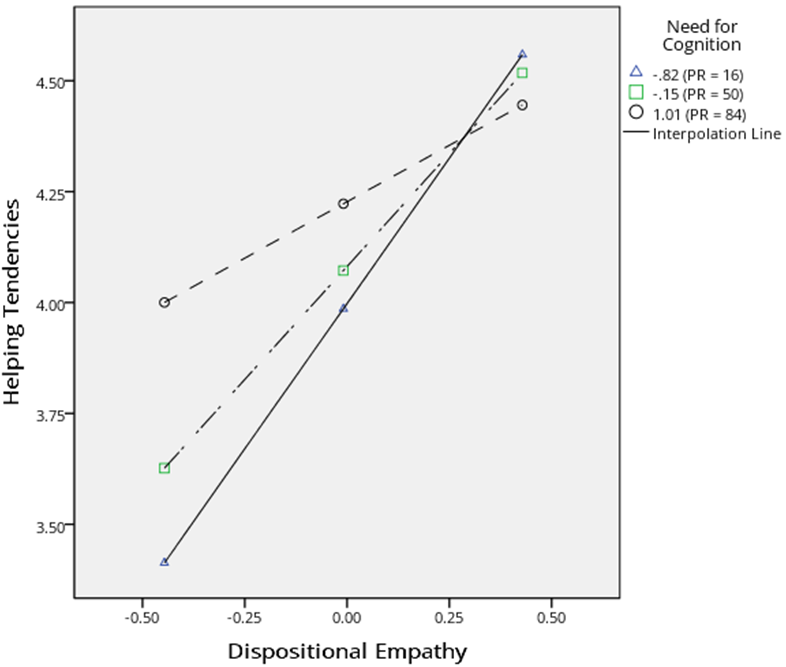

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and correlation matrix for all measures. After the predictors were centered at their means, a moderation model was tested according to Hayes PROCESS Model 1 (Hayes, 2022). Using the PROCESS program, we entered need for cognition as a moderator of dispositional empathy on helping tendencies. The results revealed that participants with higher dispositional empathy generally exhibited higher tendencies to help the mother, b = 0.95, t (160) = 6.03, p < .01. However, the interactive effect of dispositional empathy and need for cognition was significant, b = −0.44, t (160) = −2.36, p = .019. Figure 1 shows the graph of helping tendencies as a function of dispositional empathy and need for cognition. As predicted, simple slopes analysis revealed that the positive relationship between the dispositional empathy and helping tendencies was stronger among participants with lower need for cognition scores (16th percentile; b = 1.31, t = 6.41, p < .001) and weaker among those with higher need for cognition scores (84th percentile; b = 0.51, t = 1.96, p = .052).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Variables in Study 1.

|

Variables |

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

1. Dispositional empathy |

3.82 |

0.46 |

— |

|

|

|

|

2. Need for cognition |

4.32 |

0.97 |

.16* |

— |

|

|

|

3. Helping tendencies |

3.81 |

0.96 |

.46* |

.25* |

— |

|

|

Note. *p < .05. N = 164. |

|

|||||

Discussion

Our initial exploration aimed to preliminarily verify whether the positive relationship between cyberbullying bystanders’ dispositional empathy and helping tendencies is moderated by accuracy motivation. The results of Study 1 found that the positive association between dispositional empathy and helping tendencies was significantly weaker for participants higher in need for cognition (our proxy measure for accuracy motivation). This provides initial support for our core hypothesis: when bystanders are motivated to engage in deeper information processing, the predictive power of dispositional empathy on their helping tendencies is inhibited.

Despite these supportive initial findings, several limitations in Study 1 informed the design of Study 2. Specifically, accuracy motivation was measured through the Need for Cognition Scale instead of being manipulated, which limited the causal inferences that could be drawn. To address this and strengthen the causal evidence, we manipulated accuracy motivation in Study 2. Another limitation was the lack of investigation into the underlying mechanism. In the Introduction, we postulated that for cyberbullying bystanders with lower accuracy motivation and higher dispositional empathy, the tendency to help would be mediated by feelings of responsibility, a process that would not exist for those with higher accuracy motivation. To explore the mechanism responsible for the moderating effect, we therefore measured participants’ feelings of responsibility to help in Study 2.

Figure 1. Helping Tendencies as a Function of Dispositional Empathy and Need for Cognition.

Note. PR = percentile rank.

Study 2

Method

Participants

Using a convenience sampling method, we recruited 195 participants (67 male, 128 female; Mage = 20.96, SD = 5.44, range = 18–58) from two universities in northern Taiwan between July 2023 and January 2024. The recruitment and eligibility criteria were identical to those in Study 1. For this experiment, accuracy motivation was the manipulated between-subject variable. The participants were randomly assigned to either a control group (n = 96) or a high accuracy motivation group (n = 99). Preliminary analyses confirmed that randomization was successful, with no significant differences found between the two groups in terms of age, t (193) = 0.41, p = .683; gender distribution, χ2 (1) = .09, p = .759; or dispositional empathy, t (189) = 0.29, p = .775. Each participant received a convenience store voucher worth NT$100. Nine participants failing attention checks and six failing to complete all the measures were eliminated from the analysis, leaving a final sample of 180 (90 in each group).

A post hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted for Study 2 using G*Power (Version 3.1) to assess the power to detect the key interaction effect. Based on the F-test for “Linear multiple regression: Fixed model, R² increase” and our final model (which included three predictors: dispositional empathy, accuracy motivation, and their interaction), the analysis showed that our sample of 180 participants provided .80 power to detect a minimum effect size of f² = .044 for the interaction term (at α = .05). This indicates the study was adequately powered to identify small interaction effects.

Procedure

Data were collected in group sessions held in university classrooms, with 20 to 25 participants per session. Participants completed the survey in a paper-and-pencil format. Following the recruitment announcements, those who volunteered to participate were randomly assigned to different experimental conditions and led to separate classrooms. As in Study 1, participants first completed the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire followed by several filler scales, including the Need for Cognition Scale (see Study 1) and a self-esteem scale (see Supplementary Materials).

Next, the participants were instructed to read a story about a real-life cyberbullying incident that occurred in Taiwan. Studies have demonstrated that reminding participants of the importance of correctly making judgments and that instructing participants to explain the reasoning behind their responses would increase their accuracy motivation (Cronley et al., 2010; Ford & Kruglanski, 1995; Liu, 2017; Stapel et al., 1998; Thompson et al., 1994). Thus, participants in the high accuracy motivation group were told, “Being able to understand online events rationally and correctly is a crucial skill in modern society, and we want to assess your ability in this regard. You will be asked to read a passage on an event that occurred on the Internet and then to complete a questionnaire based on it. On the last page of the questionnaire, please explain the reasons for your answers to some key questions (we will tell you which questions are the key questions).” Participants in the control group were told, “Internet events are getting more and more attention in modern society. We would like to know what people really think and how they tend to behave in relation to some online incidents. You will be asked to read a passage on an event that occurred on the Internet and then to complete a questionnaire based on it. You may offer comments about this event in space on the last page of the questionnaire.” Two groups of participants read a passage on the same cyberbullying event adapted by Liu et al. (2021). The event related to a girl who had experienced cyberbullying. The description below is a summary of the material presented to participants; the full text is provided in the Appendix in both English and the original language. In the scenario, a female college student auditioned to host online auctions on a live broadcast as a model. Because she was attractive and had an appealing personality, she garnered many fans, received various job opportunities, and made large amounts of money. However, starting last year, people on the Internet began posting in a popular public fan club that allowed anonymous posting. These posts indicated that the student was not as pleasant as how she presented herself to the public. The posts implied that her behavior was offensive - for example, that she was rude to her coworkers and disrespectful to those around her after becoming famous - and that her actions must be exposed. This explosive post was followed by an increasing number of posts about the negative side of the student’s personality. She was described as disingenuous, catty, and a smoker and excessive drinker. The student responded to these negative messages online, arguing that the negative posts about her were false. She also mentioned that she understood that she must learn to handle being the target of such accusations because of her line of work. She thanked those who made comments and said she would review every suggestion. However, she also asked those who had fabricated stories about her to stop. Fans and other Internet users helped her refute the accusations, offering comfort and showing support. However, the negative publicity did not stop; some people continued to attest to the accusations against her or make even more.

Participants then completed measures regarding the accuracy motivation manipulation and their responsibility to help the victim, followed by items assessing their tendencies to help the victim (see Measures). Finally, participants were debriefed, thanked, and dismissed.

Measures

Dispositional Empathy. The measurement of dispositional empathy was identical to that in Study 1. Participants completed the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire, which demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample

(α = .82).

Accuracy Motivation Check. Two items were adapted from Liu (2017) to evaluate the effectiveness of the accuracy motivation manipulation (e.g., “I believe that I have read each question carefully and considered it thoughtfully”). Responses were rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The final score was computed by averaging the two items, which were highly correlated (r = .73, p < .001). Higher scores indicated a greater degree of accuracy motivation, confirming the effectiveness of the experimental manipulation.

Feelings of Responsibility to Help. A five-item scale was adapted from Liu et al. (2021) to assess participants’ felt responsibility to help the victim (e.g., “In this situation, I feel responsible to stand up for this student and denounce her negative portrayal in online news”). Responses were rated on the same 7-point scale. The scale demonstrated high internal consistency in the present study (α = .87). The final score was computed as the average across the five items, with higher scores indicating a stronger sense of responsibility.

Helping Tendencies. Participants completed the same four-item scale used in Study 1, adapted for the specific scenario in Study 2. The items were identical to those in Study 1, with the exception that the victim was changed to “the female student” to fit the current context. The scale demonstrated high internal consistency in the present study

(α = .86).

Results

Paired comparisons demonstrated that the high accuracy motivation group was more inclined to understand the event they read about and to answer each question carefully and thoughtfully (n = 90, M = 6.25, SD = 0.68) than was the control group (n = 90, M = 6.04, SD = 0.89), t (178) = 1.78, p = .038 (one-tailed), d = 0.27. The results indicated that accuracy motivation was effectively manipulated.

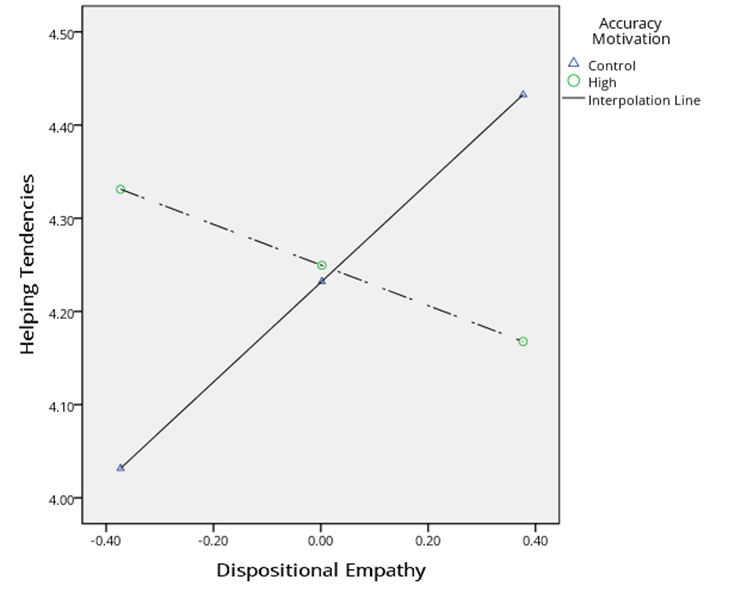

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and correlation matrix for all measures. After accuracy motivation was effect-coded (control group = −0.5; high accuracy group = 0.5) and dispositional empathy was centered at its mean, a moderation model was tested according to Hayes PROCESS Model 1. In this moderation analysis, we examined the effects of dispositional empathy, accuracy motivation, and their interaction on the helping tendencies. The results revealed that the interactive effect of dispositional empathy and accuracy motivation was significant, b = −.75, t = −2.36, p = .019 (see Model 1 in Table 3). Over 81 percent of the total explained variance (from .031/.038) was attributed to the moderated effect. Figure 2 shows the graph of helping tendencies as a function of dispositional empathy and accuracy motivation. Simple slopes analysis showed that for participants in the control group, dispositional empathy predicted greater helping tendencies, b = 0.53, t = 2.47, p = .015. For participants in the high accuracy motivation group, dispositional empathy was not associated with helping tendencies, b = −.22, t = −0.93, p = .351. This result revealed that when accuracy motivation was manipulated, the effect of dispositional empathy on the enhancement of helping tendencies was attenuated.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Variables in Study 2.

|

Variables |

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

1. Dispositional empathy |

3.81 |

0.43 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

2. Accuracy motivation |

0.5 |

0.5 |

–.02 |

— |

|

|

|

|

3. Helping tendencies |

4.24 |

0.9 |

.09 |

.01 |

— |

|

|

|

4. Feelings of responsibility to help |

3.33 |

1.11 |

.08 |

.02 |

.46* |

— |

|

|

Note. *p < .05; N = 180; Accuracy motivation: control group = −0.5, high accuracy group = 0.5. |

|

||||||

Table 3. Regression Model Coefficients in Study 2.

|

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||||||||

|

Outcome |

Helping tendencies |

Feelings of responsibility to help |

Helping tendencies |

|||||||||

|

Predictors |

b |

SE |

t |

p |

b |

SE |

t |

p |

b |

SE |

t |

p |

|

Intercept |

4.24 |

0.07 |

61.63* |

< .001 |

3.33 |

0.08 |

40.77* |

< .001 |

3.01 |

0.2 |

15.02* |

< .001 |

|

Dispositional empathy |

0.16 |

0.16 |

1 |

.321 |

0.16 |

0.19 |

0.85 |

.397 |

0.1 |

0.14 |

0.69 |

.491 |

|

Accuracy motivation |

0.02 |

0.14 |

0.14 |

.892 |

0.06 |

0.16 |

0.34 |

.731 |

–0.002 |

0.12 |

–0.02 |

.987 |

|

Dispositional empathy × Accuracy motivation |

–0.75 |

0.32 |

–2.36* |

.019 |

–0.96 |

0.38 |

–2.53* |

.012 |

–0.4 |

0.29 |

–1.37 |

.173 |

|

Feelings of responsibility to help |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.37 |

0.06 |

6.44* |

< .001 |

|

Interation ∆R2 |

.031, F (1, 176) = 5.59* |

.035, F (1, 176) = 6.42* |

.01, F (1, 175) = 1.87 |

|||||||||

|

Note. N = 180; Accuracy motivation: control group = −0.5, high accuracy group = 0.5. * p < .05. |

||||||||||||

Figure 2. Helping Tendencies as a Function of Dispositional Empathy and Accuracy Motivation.

To test the mediating role of feelings of responsibility to help underlying the interactive effect of dispositional empathy and accuracy motivation on the helping tendencies, a moderated mediation model was tested according to Hayes (2022) PROCESS Model 8. All analyses using the PROCESS program included a bias-corrected bootstrap 95% confidence interval (CI) based on 5000 bootstrap samples. First, we conducted a regression analysis to examine the effects of dispositional empathy, accuracy motivation, and their interaction on feelings of responsibility to help (see Model 2 in Table 3). The results showed that the interactive effect of dispositional empathy and accuracy motivation was significant, b = −.96, t = −2.53, p = .012. Over 85 percent of the total explained variance (from .035/.041) was attributed to the moderated effect. Simple slopes analysis showed that for participants in the control group, dispositional empathy predicted stronger feelings of responsibility to help, b = 0.64, t = 2.48, p = .014. For participants in the high accuracy motivation group, dispositional empathy was not associated with feelings of responsibility to help, b = −.32, t = −1.15, p = .251. This result revealed that when accuracy motivation was increased, the effect of dispositional empathy on the enhancement of feelings of responsibility to help was attenuated.

Finally, to determine whether the effect of dispositional empathy on helping tendencies was mediated by feelings of responsibility to help and whether this mediated relationship was moderated by accuracy motivation, we not only entered the effects of all previously constructed regression terms in Model 1 on helping tendencies but also included mean-centered feelings of responsibility to help in the equation (see Model 3 in Table 3). The results revealed that participants with higher feelings of responsibility exhibited greater tendencies to help the victim, b = 0.37, t = 6.44, p < .001. In addition, with feelings of responsibility in the model, the interactive effect of dispositional empathy and accuracy motivation on helping tendencies was smaller and turned out to be not significant compared to the interactive effect of dispositional empathy and accuracy motivation found in Model 1, b = −.4, t = −1.37, p = .173. More importantly, the index of moderated mediation was significant, effect = −0.35, 95% Boot CI = [−0.72, −0.07], indicating that accuracy motivation moderated the indirect effect of dispositional empathy on helping tendencies through feelings of responsibility to help. The results for the conditional indirect effects revealed that in the control group, the relationship between dispositional empathy and helping tendencies was mediated by feelings of responsibility to help; with a positive indirect effect = 0.24, 95% Boot CI = [0.05, 0.48]. However, in the high accuracy motivation group, there was no evidence that feelings of responsibility to help mediated the relationship between dispositional empathy and helping tendencies; indirect effect = −0.12, 95% Boot CI = [−0.35, 0.07].

Discussion

Building upon the correlational findings of Study 1, the experimental results of Study 2 replicated and extended them using an experimental manipulation of accuracy motivation. The results confirmed that the effect of dispositional empathy on helping tendencies was significantly attenuated in the high accuracy motivation group compared to the control group. This provides causal evidence that high accuracy motivation acts as a critical boundary condition, inhibiting the predictive power of dispositional empathy on helping tendencies.

More importantly, the moderated mediation analysis confirmed the underlying theoretical mechanism. In the control group, the relationship between dispositional empathy and helping tendencies was mediated by feelings of responsibility to help. Crucially, this indirect effect was eliminated in the high accuracy motivation group, as the effect of dispositional empathy on feelings of responsibility was effectively inhibited. This pattern of results provides empirical support for our proposed framework.

General Discussion

In Study 1, the results revealed that the positive relationship between dispositional empathy and helping tendencies was stronger among individuals with a lower need for cognition and weaker among individuals with a higher need for cognition. In Study 2, accuracy motivation moderated the direct effect of dispositional empathy on helping tendencies as well as the indirect effect of dispositional empathy on helping tendencies through feelings of responsibility. In the control group, dispositional empathy predicted stronger helping tendencies, mediated by feelings of responsibility. In the high accuracy motivation group, no evidence of this process was observed. Overall, the results indicate that when cyberbullying bystanders have higher levels of accuracy motivation (e.g., with high levels of need for cognition or high context-evoked accuracy motivation), the effect of dispositional empathy on the enhancement of their feelings of responsibility and their tendencies to help the victim would be attenuated.

The findings have critical theoretical implications, primarily by challenging and refining existing models of prosocial behavior and extending dual-process models into the study of bystanderism. Studies on general crisis situations or offline bullying have determined that bystanders with higher dispositional empathy are more likely to engage in helping behaviors and less likely to exhibit aggression (e.g., Haddock & Jimerson, 2017; Lambe et al., 2019; Machackova & Pfetsch, 2016; Nickerson et al., 2015; van Noorden et al., 2015; Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019). However, the relationship between bystanders’ dispositional empathy and helping behaviors in the context of cyberbullying is unclear (e.g., Balakrishnan & Fernandez, 2018; DeSmet et al., 2016; Zych, Baldry et al., 2019). Our results challenge the often-oversimplified assumption that “more empathy is always better” for prosocial outcomes. This inconsistency may be associated with bystanders’ accuracy motivation. For cyberbullying bystanders with lower accuracy motivation, higher dispositional empathy remains a significant predictor of helping behaviors, aligning with findings from general crisis or offline bullying contexts (Davis, 2015; Dimberg & Thunberg, 2012; X. Zhao, 2019). However, for cyberbullying bystanders with higher accuracy motivation, they may not be more likely to exhibit helping behaviors despite having higher dispositional empathy. This finding forces models of bystander behavior to evolve beyond a simple main-effect focus on empathy. Accuracy motivation constitutes an essential inhibitor of the positive relationship between cyberbullying bystanders’ dispositional empathy and helping behaviors.

We further explain the possible mechanisms by which accuracy motivation attenuated the dispositional empathy–helping tendency relationship by applying and extending the Heuristic-Systematic Model (HSM; Chen & Chaiken, 1999). In Study 2, the results revealed that in the control group, dispositional empathy predicted stronger helping tendencies through the reinforcement of feelings of responsibility to help (González & Lay, 2017; Knauf et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2021). This demonstrates the operation of the heuristic processing path, where empathy acts as an affective heuristic that swiftly leads to prosocial action. However, in the high accuracy motivation group, dispositional empathy was not correlated with feelings of responsibility to help or with helping tendencies. This inhibition occurred because high accuracy motivation compelled bystanders into the systematic processing path, a mechanism that extends classic dual-process models into explaining bystander inaction (e.g., Bayes et al., 2020; Chen & Chaiken, 1999; Liu, 2017; Liu et al., 2016). Furthermore, this finding offers a refinement to the foundational Bystander Intervention Model (BIM; Darley & Latane, 1968), which primarily frames intervention as a sequential cognitive decision-making process. The BIM outlines five sequential steps leading to intervention: noticing the event, interpreting it as an emergency, assuming responsibility, knowing how to help, and deciding to intervene. Our study not only acknowledges the crucial role of the affective factor, empathy, in the transition to assuming responsibility (Step 3), but also highlights a key cognitive hurdle. High accuracy motivation complicates the interpretation stage (Step 2) of the BIM. For cyberbullying, interpreting the event is not merely about recognizing harm; it also involves verifying information and assigning fault. Since verifying the authenticity and reasonableness of complex online accusations is often difficult, this informational ambiguity leads to prolonged cognitive deliberation, essentially suspending both judgment and action and preventing the bystander from assuming personal responsibility (BIM Step 3). Consequently, even when cyberbullying bystanders have high dispositional empathy, those driven by higher accuracy motivation may not develop stronger feelings of responsibility to aid the victim or exhibit stronger helping tendencies.

The findings have notable practical implications. In the face of rampant online disinformation, the public is rightly encouraged and expected to possess high levels of accuracy motivation to critically judge the veracity of information and make informed decisions. However, this positive motivation for accuracy presents a critical, overlooked risk when rapid helping action is required online. In cyberbullying situations, bystanders with high dispositional empathy are theoretically more likely to help the victim. Yet, if they simultaneously possess higher accuracy motivation, they may focus on verifying the messages’ authenticity. Since the veracity of cyberbullying messages is often difficult to determine, the effect of high empathy on enhancing their feelings of responsibility and helping tendencies is likely to be inhibited. This occurs because when the public focuses on verifying the reasonableness of various messages, even the most empathetic individuals may halt their intervention toward the victim, and the resulting lack of bystander aid can lead to serious consequences.

Therefore, anti-cyberbullying organizations or public media outlets should launch educational campaigns and public service announcements to educate the public, who often assumes the role of bystanders to cyberbullying, about this critical risk that accuracy motivation may pose. These campaigns should directly encourage the public to set aside their motivation to examine the veracity of cyberbullying messages in an urgent cyberbullying situation and instead prioritize providing the victim with immediate assistance, as this constitutes a viable strategy for mitigating negative outcomes. Furthermore, educational institutions should leverage these results to develop more effective anti-cyberbullying programs. These programs should integrate training courses focused on risk awareness, specifically designed to teach students to recognize the inhibiting risk that the tendency for ‘seeking accuracy’ poses on bystander helping behavior during a cyberbullying incident. Students should be actively taught to momentarily set aside their motivation for seeking accuracy in favor of immediate prosocial action.

This study has some limitations and implications for further research. The first limitation concerns the generalizability of our results. Both Study 1 and Study 2 utilized undergraduate students, which restricts the direct application of our findings to the broader population. Future research should replicate these findings across diverse age groups to confirm the robustness of the proposed interaction and its underlying mechanism. Second, while we used two different real-life inspired scenarios, these may not represent the full spectrum of cyberbullying. Future research could explore whether our findings generalize to incidents varying in severity, ambiguity, or the relationship between the bystander and the victim. Third, in Study 1, we measured the participants’ accuracy motivation by assessing their need for cognition. However, there are other characteristics that correlate with need for cognition or accuracy motivation, such as critical thinking (see Bravo et al., 2020; Sosu, 2013) and need for evidence (see Garrett & Weeks, 2017). In Study 2, we manipulated accuracy motivation by emphasizing the importance of correctly understanding online events and the need to explain the reasoning behind their responses to the participants. Other manipulation methods that can enhance accuracy motivation were not employed. Thus, studies can adopt alternative measures and manipulation approaches to determine the stability of the moderating effect of accuracy motivation in the relationship between cyberbullying bystanders’ dispositional empathy and helping behaviors. Fourth, our studies measured helping tendencies rather than actual helping behaviors. While self-reported intentions are a common proxy in this field, future research should employ more behaviorally-oriented measures. A final limitation of this study concerns our measurement of empathy. While we chose to emphasize affective empathy based on its consistent empirical link to prosocial behavior toward victims and its theoretical fit as an affective heuristic within our dual-process framework, we did not separately measure the cognitive component. We recommend that future research address this by separately measuring both components to clarify cognitive empathy’s unique role in the bystander process.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Use of AI Services

The authors declare they have used AI services for grammar correction and minor style refinements. They carefully reviewed all suggestions from these services to ensure the original meaning and factual accuracy were preserved.

Acknowledgement

This study is supported by the Research Grant MOST 111-2410-H-007-065-MY2 and MOST 111-2410-H-011-021-MY2 from National Science and Technology Council (Taiwan).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Appendix

Scenario Used in Study 1

English Translation

Recently, a high-profile social incident occurred in Taiwan. A mother created a Facebook fan page to ask netizens to pray for and send support to her three-year-old daughter, who was critically injured and paralyzed from the neck down following a car accident. The incident attracted significant attention from both netizens and the news media. The accident happened when the mother was driving with her daughter and collided with a utility truck. Anxious and helpless, the mother could not wait for rescue personnel; she rushed to the passenger seat, carried her daughter out, and crouched by the roadside. Nearby bystanders also hurried over to help expedite the trip to the hospital. Upon arrival, the daughter had a coma scale of only 3. After ten days of emergency treatment, she regained movement in her head, but her body remained paralyzed from the neck down. Later, the mother frequently shared videos of her daughter’s rehabilitation on the fan page. In these videos, she expressed her love for her daughter, accompanied her through rehabilitation exercises, and offered encouragement, hoping her daughter would persevere. She also expressed her hope for a miracle and asked netizens to support and pray for her daughter, wishing that she would not have to spend her life bedridden. Many netizens left messages of blessing on the fan page, and the story was widely reported by Taiwanese news media.

However, dissenting voices began to emerge at this time, including the following: (1) Some netizens pointed out that the mother was suspected of speeding at the time of the accident, failed to use a child safety seat as required by law, and illegally allowed her daughter to sit in the front seat. Netizens also argued that the mother might have caused secondary injury to her daughter by moving her unauthorized after the impact. They claimed that the mother’s negligence and ignorance were the primary causes of her daughter’s paralysis. (2) Some netizens alleged that the mother was adept at using the popularity of her fan page to make demands on others. For instance, when she wanted to apply for a special government-approved surgery for which many were on the waiting list, she allegedly mobilized netizens to pressure the Department of Health into granting her daughter priority. (3) Some netizens who were at the hospital accused the mother of rarely staying outside her daughter’s intensive care unit. They claimed she put on an act in front of the media but would immediately start using her phone once the cameras were off, showing little genuine care for her daughter. (4) After the daughter was discharged, netizens further accused the mother of forcing her daughter, whose injured cervical spine impaired her ability to regulate body heat, to attend a charity event under the sun despite her poor health. They criticized the mother for sacrificing her daughter’s well-being to “grab headlines.” Furthermore, the mother even received a “Model Mother” award from the government for her role in the incident. Many netizens characterized her as a hypocritical attention-seeker who built her sense of achievement and gained benefits from her paralyzed daughter.

Later, the mother issued clarifications, but the controversy persisted. While some netizens continued to cheer for the mother, others continued to question and condemn her. Additionally, some netizens argued that “in the online world, since the mother chose to establish a fan page and gain attention, she must naturally accept that some netizens will make negative comments about her; this is something she has to bear.”

Original Language (Traditional Chinese)

之前台灣發生一個受關注的社會事件。有一位媽媽因為三歲女兒車禍重傷,全身癱瘓,開設了FB粉絲團,請網友幫忙集氣加油,引起了網友與新聞媒體的大量關注。這位媽媽開車載著女兒,撞上電信公司的工程車。媽媽等不及救援人員,跑到前座抱出女兒,蹲在路邊焦急又無助,附近民眾也紛紛趕來幫忙,協助盡快送醫。而女兒到院時昏迷指數只有3,經過10天搶救後頭部可以活動了,頸部以下卻全身癱瘓。後來媽媽常常在粉絲團上分享女兒復健的影片。在影片中,媽媽會跟女兒說愛她,也努力陪著女兒復健,幫女兒加油、打氣,希望女兒堅持下去。同時,她也說期待奇蹟,並請網友為女兒加油、集氣,希望讓她的人生不要在病床上度過。許多網友至粉絲團為母女留下祝福的話語,台灣的新聞媒體也大量報導這個事件。

然而此時開始有不同的聲音傳出,包括:(1)有網友指出「車禍當時媽媽疑似超速,且未依規定讓女兒使用汽車安全座椅,並違規讓女兒坐在前座」。同時,網友也指出「媽媽可能因為擅自移動受到撞擊的女兒,讓女兒受到二度傷害」。網友指出「媽媽的疏忽和無知是造成女兒癱瘓的主要原因」;(2)有網友指出「媽媽擅於利用粉絲專頁的人氣對別人予取予求,如:媽媽想申請衛生署專案核可的手術,但有許多人在排隊,她會利用粉絲團網友來圍剿衛生署取得優先手術的機會」;(3)有些在醫院的網友則出面指控,「媽媽不常待在女兒的加護病房外面,且在媒體前會裝模作樣,鏡頭移開就開始滑手機,根本沒有在照顧女兒」。(4)在女兒出院後,有網友進一步指控「媽媽明明知道女兒的身體狀況不好,還讓頸椎受傷無法散熱的女兒抱病參加要曬太陽的公益活動」,痛斥媽媽硬要犧牲女兒來「搏版面」;另外,媽媽甚至因女兒的事件領取了政府「慈馨媽媽」的獎項,並接受表揚。許多網友指出「這位媽媽是個表裡不一、好出鋒頭,把成就感建立在癱瘓女兒身上並獲得好處的人」。

之後,媽媽做出澄清,但是爭議仍然持續。有網友持續幫媽媽加油,但也有網友在此時則是針對媽媽繼續進行質疑與譴責。另外也有些網友認為「在網路世界中,媽媽選擇成立粉絲團,獲得了網友的關注,自然也會有網友對她做出負向的評論,這是媽媽自己本來就需要承擔的」。

Scenario Used in Study 2

English Translation

In recent years, more and more people have aspired to work in performance-related fields, such as modeling, live streaming, becoming a YouTuber (Internet celebrity or content creator), or working in the entertainment industry. While there are attractive aspects to working in this field, individuals are also prone to encountering unpleasant experiences, such as criticism. Last year, a female university student actively pursued performance-related work, including auditioning for online fashion modeling, performing, hosting, and live streaming. Because of her attractive appearance and her confident, somewhat innocent, and occasionally humorous demeanor, she garnered significant attention from netizens. Many considered her to be a simple, straightforward, funny, and sunny person. She continuously managed her blog and fan page, periodically uploading her own creative works or funny videos to interact with netizens. Consequently, she accumulated a growing number of fans, leading to more job offers and financial opportunities.

However, starting last year, a netizen posted in a famous public fan group that allows anonymous submissions, stating that they “could not stand this student’s behavior and wanted to unmask her,” and proceeded to expose some real-life negative experiences of interacting with her in private. Following this initial post, more netizens began posting to corroborate the student's alleged true private persona. These netizens claimed, "This student is extremely hypocritical and manipulative. She pretends to be well-behaved, simple, and sunny in public to win everyone’s favor, but she is not like that in private. For instance, her nature is neither simple nor sunny; she has habits of smoking and excessive drinking, and she is quite petty and competitive.” Some netizens also confirmed, “After gaining some fame, she developed a 'big-head' syndrome (became arrogant). Her work attitude is poor; she often puts on a smiling, easy-going face in front of the camera, but immediately turns sour-faced once off-camera.” Additionally, other netizens pointed out, “She plagiarizes other people’s ideas. The content she posts online is clearly copied from others, yet she pretends it is her original work.” One netizen even escalated the allegations, claiming, “She is very money-oriented and likes to associate with the wealthy and powerful. She even once sold her body and actively seduced a rich man in hopes of marrying into wealth.”

In response to these negative allegations, the student posted a statement. She pointed out that “the negative news exposed by netizens does not reflect behavior she has ever engaged in; she does not have habits of smoking or excessive drinking in private, nor has she ever sold her body for any purpose.” Furthermore, she stated, “She understands that working in this industry requires enduring such fabricated stories. She thanks those who offered guidance and will humbly review every suggestion, but she also asks those making irresponsible comments to conduct themselves with dignity.”

After her response, while some fans and netizens posted to “clarify on her behalf and express comfort and support,” many others continued to post confirmations of the negative news and even added further allegations. Additionally, some netizens argued that “since she chose to work in this industry and gained attention and benefits, she must naturally accept that netizens will make negative comments about her; this is something she has to bear.”

Original Language (Traditional Chinese)

近年來有越來越多人嚮往從事表演相關工作,例如擔任模特兒、網路直播主、Youtuber(網路紅人或網路影片創作者)或在演藝圈工作等。在這一行工作有一些令人嚮往之處,但也容易遭遇一些不愉快的事情(如遭遇批評)。去年有一個大學女同學積極投入表演相關工作,包括去應徵網拍模特兒,也從事表演、主持與網路直播工作等。因為她的外表不錯,顯露出來的談吐舉止大方,有點天真,有時也很好笑,因此受到了不少網友的關注,許多網友都認為她是個單純、直率、搞笑與健康陽光的人。她也持續經營自己的部落格與粉絲團,不定時會上傳一些自己創作的作品或好笑影片到網路上和網友互動,因此累積了越來越多的粉絲,工作邀約與賺錢機會也越來越多。

但去年開始,有一個網友先在一個可以匿名發文的著名公開粉絲團中,發文表示「因為看不慣這位女同學的所作所為,想要揭穿她的假面具」,所以爆料了一些自己和這位女同學私下相處的真實負面經驗。在這篇爆料文出現之後,有越來越多網友跟著發文證實這位女同學私下真實的樣子。這些網友指出「這位女同學相當虛偽,心機很重,她在大眾面前會裝成乖巧、單純、陽光的樣子,來博得大家喜歡,但其實她私底下並不是這樣的人,例如她本性並不單純與陽光,有抽煙、酗酒的習慣,且相當小心眼與愛比較。」;也有網友證實指出,「這位女同學有點名氣之後,有大頭症,工作態度不佳,常常鏡頭前裝成一個笑臉迎人,好相處的樣子,但下了鏡頭後馬上就臭臉對人。」;另外,有網友指出,「這位女同學會抄襲別人的點子,她在網路上發表的東西明明是抄襲別人的內容,但會裝成是自己自創的作品。」;甚至有網友加碼爆料,「這位女同學很愛錢,喜歡跟有錢有勢的人來往,甚至曾經為了嫁給有錢人,出賣自己的肉體,主動引誘有錢人。」

針對這些網友爆料的負面消息,這位女同學發文做出回應。她指出「網友爆料的負面消息並不像是她有做過的行為,她私下並無抽菸酗酒的習慣,也沒有因為任何目的出賣自己的身體。」另外,她也指出「她瞭解從事這些工作,需要承受這些子虛烏有的事情,謝謝指教她的人,她會虛心檢討每個對她的建議,但也請不負責任亂發言的人自重。」

在這位女同學做出回應之後,雖然有些粉絲或網友發文「幫這位女同學澄清,並對她表達安慰與支持」,但也有不少的網友持續發文證實這些負面消息,甚至加碼爆料。另外有些網友則指出「這位女同學選擇從事這一行的工作,獲得了關注和好處,自然也會有網友對她做出負向評論,這是她自己本來就需要承擔的」。

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2026 Cheng-Hong Liu, Fa-Chung Chiu, Po-Sheng Huang, Ting-Huan Lin, Chia-Lin Chang