Factors associated with connectedness to social media influencers among Italian and Dutch young adults

Vol.20,No.1(2026)

Parasocial bonds with Social Media Influencers (SMIs) can significantly influence followers’ behaviors, attitudes, and well-being, especially during adolescence and young adulthood. This study examined how diverse dimensions of connectedness with SMIs (i.e., escape, imitation, modeling, and aspiration) relate to perceived social connectedness in offline, combined offline-online social connectedness and online contexts, as well as to social self-efficacy and problematic social media use, age and sex. A total of 554 respondents (346 from Italy and 308 from the Netherlands) aged 18 to 35 years (Mage = 23.85; SDage = 3.63; 67.6% female) completed an online survey. Structural equation modeling was employed to test the hypothesized associations, followed by multigroup analysis to assess cross-cultural differences. Findings revealed that offline social connectedness was negatively associated with the escape dimension, while offline-online connectedness showed negative associations with escape and imitation. In contrast, online connectedness was positively associated with these same dimensions. Thus, the form in which social connectedness is experienced seems to relate to more immediate and superficial forms of parasocial engagement. Social self-efficacy was positively associated only with aspiration, highlighting a selective, identity-driven engagement with SMIs. Problematic social media use was positively linked to all connectedness dimensions, suggesting its broad influence. Younger respondents were more inclined to imitation, modeling and aspiration compared to older respondents, while male respondents reported higher scores than females across all dimensions. Finally, multigroup analysis revealed significant differences between Italian and Dutch respondents, emphasizing the role of cultural context in shaping parasocial dynamics with SMs.

connectedness to influencers; online and offline social connectedness; problematic social media use; social self-efficacy; cross-countries study

Maria Rosaria Nappa

Department of Systems Medicine, Tor Vergata University of Rome, Rome

Maria Rosaria Nappa, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the Department of Systems Medicine of Tor Vergata University of Rome, Italy. Her research focuses on bullying and cyberbullying dynamics in school settings, and on psychosocial processes in adolescence and young adulthood in both online and offline contexts.

Sara Pabian

Department of Communication and Cognition, Tilburg University, Tilburg

Sara Pabian, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Communication and Cognition of Tilburg University and is also an affiliated researcher of the Department of Communication Studies of University of Antwerp. Her research focuses on risks and opportunities of online interactions among both adolescents and adults.

Mara Morelli

Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, and Health Studies, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome

Mara Morelli, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Developmental Psychology at Sapienza University of Rome, Italy. Her interests are focused on online risky behaviors during adolescence, parent-child relationships and risk factors in early-adolescence and adolescence.

Angela Costabile

Department of Culture, Education and Society (DiCES), University of Calabria, Cosenza

Angela Costabile, PhD, is Full Professor in Developmental and Educational Psychology. Her main research fields are primary relationships, aggressive behavior among peers, and risk of radicalization in youth.

Elena Cattelino

Department of Human and Social Science, University of Valle d'Aosta, Aosta

Elena Cattelino, PhD, is Full Professor of Developmental and Educational Psychology at the University of Aosta Valley, Italy. Her interests focus on family relationships, risky and protective factors during adolescence and young adulthood.

Roberto Baiocco

Department of Developmental & Social Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome

Roberto Baiocco, PhD, is a Full Professor of Developmental Psychology at the Sapienza University of Rome, Italy. His research focuses on family functioning, friendship quality, and risk factors in early adolescence, adolescence and young adulthood.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Allen, K.-A., Kern, M. L., Rozek, C. S., McInerney, D. M., & Slavich, G. M. (2021). Belonging: A review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1883409

Arnett, J. J. (2023). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197695937.001.0001

Baek, Y. M., Bae, Y., & Jang, H. (2013). Social and parasocial relationships on social network sites and their differential relationships with users' psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(7), 512–517. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0510

Baiocco, R., Chirumbolo, A., Bianchi, D., Ioverno, S., Morelli, M., & Nappa, M. R. (2016). How HEXACO personality traits predict different selfie-posting behaviors among adolescents and young adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 2080. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02080

Ballantine, P. W., & Martin, B. A. (2005). Forming parasocial relationships in online communities. Advances in Consumer Research, 32(1), 197–201. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267374790_Forming_Parasocial_Relationships_in_Online_Communities

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Blight, M. G., Ruppel, E. K., & Schoenbauer, K. V. (2017). Sense of community on Twitter and Instagram: Exploring the roles of motives and parasocial relationships. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(5), 314–319. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0505

Bond, B. J. (2018). Parasocial relationships with media personae: Why they matter and how they differ among heterosexual, lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Media Psychology, 21(3), 457–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2017.1416295

Branch, S. E., Wilson, K. M., & Agnew, C. R. (2013). Committed to Oprah, Homer, or House: Using the investment model to understand parasocial relationships. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(2), 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030938

Brooks, S., & Longstreet, P. (2015). Social networking’s peril: Cognitive absorption, social networking usage, and depression. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 9(4), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2015-4-5

Chae, J. (2018). Explaining females’ envy toward social media influencers. Media Psychology, 21(2), 246–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2017.1328312

Chang, C.-H., Chang, Y.-C., Yang, L., & Tzang, R.-F. (2022). The comparative efficacy of treatments for children and young adults with internet addiction/internet gaming disorder: An updated meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052612

Chauvin, K., Van Gerven, L. A., Madison, T. P., & Auter, P. J. (2024). “I learned it from watching YOU!”: Parasocial relationships with YouTubers and self-efficacy. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 13(1), 27–52. https://thejsms.org/index.php/JSMS/article/view/1231

Chung, S., & Cho, H. (2017). Fostering parasocial relationships with celebrities on social media: Implications for celebrity endorsement. Psychology & Marketing, 34(4), 481–495. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21001

Connolly, J. (1989). Social self-efficacy in adolescence: Relations with self-concept, social adjustment, and mental health. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 21(3), 258–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079809

de Bérail, P., & Bungener, C. (2022). Parasocial relationships and YouTube addiction: The role of viewer and YouTuber video characteristics. Psychology of Language and Communication, 26(1), 169–206. https://doi.org/10.2478/plc-2022-0009

de Lenne, O., Vandenbosch, L., Eggermont, S., Karsay, K., & Trekels, J. (2020). Picture-perfect lives on social media: A cross-national study on the role of media ideals in adolescent well-being. Media Psychology, 23(1), 52–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2018.1554494

Derrick, J., Gabriel, S., & Tippin, B. (2008). Parasocial relationships and self-discrepancies: Faux relationships have benefits for low self-esteem individuals. Personal Relationships, 15(2), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2008.00197.x

Dhanesh, G. S., & Duthler, G. (2019). Relationship management through social media influencers: Effects of followers’ awareness of paid endorsement. Public Relations Review, 45(3), Article 101765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.03.002

Di Giunta, L., Eisenberg, N., Kupfer, A., Steca, P., Tramontano, C., & Caprara, G. V. (2010). Assessing perceived empathic and social self-efficacy across countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000012

Dinh, T. C. T., & Lee, Y. (2022). “I want to be as trendy as influencers”–how “fear of missing out” leads to buying intention for products endorsed by social media influencers. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 16(3), 346–364. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-04-2021-0127

Dinkha, J., Mitchel, C., & Dakhli, M. (2015). Attachment styles and parasocial relationships: A collectivist society perspective. In B. Mohan (Ed.), Construction of social psychology: Advances in psychology and psychological trends (pp. 105–121). InScience Press.

Djafarova, E., & Rushworth, C. (2017). Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.009

Eyal, K., & Te’eniHarari, T. (2013). Explaining the relationship between media exposure and early adolescents’ body image perceptions: The role of favorite characters. Journal of Media Psychology, 25(3), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000094

Eyal, K., Te'eni-Harari, T., & Katz, K. (2020). A content analysis of teen-favored celebrities' posts on social networking sites: Implications for parasocial relationships and fame-valuation. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 14(2). Article 7. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2020-2-7.

Ezzat, H. (2020). Social media influencers and the online identity of Egyptian youth. Catalan Journal of Communication & Cultural Studies, 12(1), 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1386/cjcs_00017_1

Farivar, S., Wang, F., & Turel, O. (2022). Followers' problematic engagement with influencers on social media: An attachment theory perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 133, Article 107288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107288

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Genner, S., & Süss, D. (2017). Socialization as media effect. In P. Rössler, C. A. Hoffner, & L. van Zoonen (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of media effects. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0138

Giles, D. C. (2002). Parasocial interaction: A review of the literature and a model for future research. Media Psychology, 4(3), 279–305. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0403_04

Giles, D. C., & Maltby, J. (2004). The role of media figures in adolescent development: Relations between autonomy, attachment, and interest in celebrities. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(4), 813–822. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00154-5

Gleason, T. R., Theran, S. A., & Newberg, E. M. (2017). Parasocial interactions and relationships in early adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 255. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00255

Gong, A.-D., & Huang, Y.-T. (2023). Finding love in online games: Social interaction, parasocial phenomenon, and in-game purchase intention of female game players. Computers in Human Behavior, 143, Article 107681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107681

Grieve, R., Indian, M., Witteveen, K., Tolan, G. A., & Marrington, J. (2013). Face-to-face or Facebook: Can social connectedness be derived online? Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 604–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.017

Hartmann, T. (2017). Parasocial interaction, parasocial relationships, and well-being. In L. Reinecke & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of media use and well-being: International perspectives on theory and research on positive media effects (pp. 131–144). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Hoffner, C. A., & Bond, B. J. (2022). Parasocial relationships, social media, & well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, Article 101306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101306

Horton, D., & Wohl, R. R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

Jarzyna, C. L. (2021). Parasocial interaction, the COVID-19 quarantine, and digital age media. Human Arenas, 4(3), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-020-00156-0

Joshi, Y., Lim, W. M., Jagani, K., & Kumar, S. (2025). Social media influencer marketing: Foundations, trends, and ways forward. Electronic Commerce Research, 25(2), 1199–1253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-023-09719-z

Keil, M., Tan, B. C., Wei, K.-K., Saarinen, T., Tuunainen, V., & Wassenaar, A. (2000). A cross-cultural study on escalation of commitment behavior in software projects. MIS Quarterly, 24(2), 299–326. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3250940

Ki, C.-W. C., & Kim, Y.-K. (2019). The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Psychology & Marketing, 36(10), 905–922. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21244

Kim, H. (2022). Keeping up with influencers: Exploring the impact of social presence and parasocial interactions on Instagram. International Journal of Advertising, 41(3), 414–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1886477

La Ferle, C., & Chan, K. (2008). Determinants for materialism among adolescents in Singapore. Young Consumers: Insight and Ideas for Responsible Marketers, 9(3), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473610810901633

Lajnef, K. (2023). The effect of social media influencers' on teenagers behavior: An empirical study using cognitive map technique. Current Psychology, 42(22), 19364–19377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04273-1

Lakey, B., Cooper, C., Cronin, A., & Whitaker, T. (2014). Symbolic providers help people regulate affect relationally: Implications for perceived support. Personal Relationships, 21(3), 404–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12038

Lee, R. M., Draper, M., & Lee, S. (2001). Social connectedness, dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors, and psychological distress: Testing a mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(3), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.48.3.310

Lee, R. M., & Robbins, S. B. (1995). Measuring belongingness: The Social Connectedness and the Social Assurance scales. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(2), 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.42.2.232

Lee, R. M., & Robbins, S. B. (1998). The relationship between social connectedness and anxiety, self-esteem, and social identity [Editorial]. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45(3), 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.338

Lee, Y.-H., Yuan, C. W., & Wohn, D. Y. (2021). How video streamers’ mental health disclosures affect viewers’ risk perceptions. Health Communication, 36(14), 1931–1941. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1808405

Liebes, T., & Katz, E. (1990). The export of meaning: Cross‑cultural readings of Dallas. Oxford University Press.

Liebers, N., & Schramm, H. (2019). Parasocial interactions and relationships with media characters – An inventory of 60 years of research. Communication Research Trends, 38(2), 4–31.

Liebers, N., & Schramm, H. (2022). Intimacy despite distance: The dark triad and romantic parasocial interactions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(2), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211038051

Liu, J. (2025). Virtual presence, real connections: Exploring the role of parasocial relationships in virtual idol fan community participation. Global Media and China 10(4), 490–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/20594364231222976

Liu, J., & Lee, J.-S. (2024). Social media influencers and followers’ loneliness: The mediating roles of parasocial relationship, sense of belonging, and social support. Online Media and Global Communication, 3(4), 607–630. https://doi.org/10.1515/omgc-2024-0025

Lou, C. (2022). Social media influencers and followers: Theorization of a trans-parasocial relation and explication of its implications for influencer advertising. Journal of Advertising, 51(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1880345

Lowe-Calverley, E., & Grieve, R. (2021). Do the metrics matter? An experimental investigation of Instagram influencer effects on mood and body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 36, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.10.003

Madison, T. P., Porter, L. V., & Greule, A. (2016). Parasocial compensation hypothesis: Predictors of using parasocial relationships to compensate for real-life interaction. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 35(3), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276236615595232

Martino, L. D. (2019). Realisms and Idealisms in Italian Culture, 1300-2017: Edited by Brendan Hennessey, Laurence E. Hooper, and Charles L. Leavitt IV. Pp. 463. Special Issue of The Italianist, vol. 37, no. (3), 2017. Italian Culture, 37(2), 169–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/01614622.2019.1683270

Moore, T. L. (2006). Social connectedness and social support of doctoral students in counselor education [Doctoral dissertation, Idaho State University].

Naranjo-Zolotov, M., Turel, O., Oliveira, T., & Lascano, J. E. (2021). Drivers of online social media addiction in the context of public unrest: A sense of virtual community perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 121, Article 106784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106784

Phua, J. (2016). The effects of similarity, parasocial identification, and source credibility in obesity public service announcements on diet and exercise self-efficacy. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(5), 699–708. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314536452

Reuter, C., Kaufhold, M. A., Schmid, S., Spielhofer, T., & Hahne, A. S. (2019). The impact of risk cultures: Citizens’ perception of social media use in emergencies across Europe. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 148, Article 119724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119724

Riedl, C., Köbler, F., Goswami, S., & Krcmar, H. (2013). Tweeting to feel connected: A model for social connectedness in online social networks. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 29(10), 670–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2013.768137

Rubin, A. M., & Perse, E. M. (1987). Audience activity and soap opera involvement: A uses and effects investigation. Human Communication Research, 14(2), 246–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1987.tb00129.x

Rubin, A. M., Perse, E. M., & Powell, R. A. (1985). Loneliness, parasocial interaction, and local television news viewing. Human Communication Research, 12(2), 155–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1985.tb00071.x

Rubin, R. B., & McHugh, M. P. (1987). Development of parasocial interaction relationships. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 31(3), 279‒292. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838158709386664

Russell, C. A., Norman, A. T., & Heckler, S. E. (2004). The consumption of television programming: Development and validation of the connectedness scale. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 150–161. https://doi.org/10.1086/383431

Savci, M., & Aysan, F. (2017). Technological addictions and social connectedness: Predictor effect of internet addiction, social media addiction, digital game addiction and smartphone addiction on social connectedness. Dusunen Adam: Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 30(3), 202–216 https://doi.org/10.5350/DAJPN2017300304.

Schmid, H., & Klimmt, C. (2011). A magically nice guy: Parasocial relationships with Harry Potter across different cultures. International Communication Gazette, 73(3), 252–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048510393658

Sheldon, K. M., Abad, N., & Hinsch, C. (2011). A two-process view of Facebook use and relatedness need-satisfaction: Disconnection drives use and connection rewards it. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(4), 766–775. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022407

Subrahmanyam, K., Reich, S. M., Wächter, N., & Espinoza, G. (2008). Online and offline social networks: Use of social networking sites by emerging adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29(6), 420–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.07.003

Taddeo, G. (2023). Life long/insta-learning: The use of influencers as informal educators. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 15(2), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.14658/PUPJ-IJSE-2023-2-8

Tatem, C. P., & Ingram, J. (2022). Social media habits but not social interaction anxiety predict parasocial relationships. Journal of Social Psychology Research, 1(2), 198–211. https://doi.org/10.37256/jspr.1220221496

Trombin, M., & Veglianti, E. (2020). Influencer marketing for museums: A comparison between Italy and the Netherlands. International Journal of Digital Culture and Electronic Tourism, 3(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJDCET.2020.105893

Tukachinsky, R., & Dorros, S. M. (2018). Parasocial romantic relationships, romantic beliefs, and relationship outcomes in USA adolescents: Rehearsing love or setting oneself up to fail? Journal of Children and Media, 12(3), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2018.1463917

Tukachinsky, R., Walter, N., & Saucier, C. J. (2020). Antecedents and effects of parasocial relationships: A meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 70(6), 868–894. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa034

Turel, O., & Serenko, A. (2012). The benefits and dangers of enjoyment with social networking websites. European Journal of Information Systems, 21(5), 512–528. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2012.1.

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2007). Online communication and adolescent well-being: Testing the stimulation versus the displacement hypothesis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1169–1182, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00368.x

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2009). Social consequences of the internet for adolescents: A decade of research. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01595

Valkenburg, P. M., Koutamanis, M., & Vossen, H. G. (2017). The concurrent and longitudinal relationships between adolescents' use of social network sites and their social self-esteem. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.008

van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Lemmens, J. S., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2016). The Social Media Disorder Scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 478–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2016.03.038

van Zalk, M. H. W., Van Zalk, N., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2014). Influences between online–exclusive, conjoint and offline–exclusive friendship networks: The moderating role of shyness. European Journal of Personality, 28(2), 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1895

Vandebosch, H., & Eggermont, S. (2002). Elderly people’s media use: At the crossroads of personal and societal developments. Communications, 27(4), 437–455. https://doi.org/10.1515/comm.2002.002

Willoughby, J. F., & Myrick, J. G. (2019). Entertainment, social media use and young women’s tanning behaviours. Health Education Journal, 78(3), 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896918819643

Wu, Y.-J., Outley, C., Matarrita-Cascante, D., & Murphrey, T. P. (2016). A systematic review of recent research on adolescent social connectedness and mental health with internet technology use. Adolescent Research Review, 1, 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-015-0013-9

Authors´ Contribution

Maria Rosaria Nappa: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. Sara Pabian: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing—review & editing. Mara Morelli: formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft. Angela Costabile: supervision, writing—review & editing. Elena Cattelino: methodology, writing—review & editing. Roberto Baiocco: project administration, supervision, writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

October 1, 2024

Revisions received:

March 31, 2025

August 4, 2025

November 5, 2025

Accepted for publication:

November 7, 2025

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

In the last decades, the rise of social media has transformed the way young adults form and experience social relationships, including those with social media influencers (SMIs; e.g., Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023). Previous research has primarily examined the formation of bonds with SMIs by focusing on the amount and the good quality of the relationship, commonly referred to as the level of parasocial relationship (PSR; Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lou, 2022), often within the context of influencer marketing (Joshi et al., 2025). However, limited attention has been paid to theoretical models that account for different parasocial patterns, and to how various sources of social connectedness may influence the development of these bonds. To address this gap, the present study adopts a cross-country design to investigate how demographic and psychosocial factors, along with cultural background, are associated with different dimensions of connectedness with SMIs, specifically considering the influence of distinct sources of social connectedness across offline and online contexts.

Against this backdrop, a SMI “is a person who, through personal branding, builds and maintains relationships with multiple followers on social media, and has the ability to inform, entertain, and potentially influence followers’ thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors” (Dhanesh & Duthler, 2019, p. 3). Specifically, due to the characteristics of SMIs that followers admire or aspire to possess, they can be considered identification models who portray idealized images (Dinh & Lee, 2022; Ki & Y.-K. Kim, 2019; La Ferle & Chan, 2008). In other words, SMIs serve as a social reference across various identity domains, influencing the exploration of different roles and behaviors (de Lenne et al., 2020; Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023).

The identification process stimulated by SMIs has been linked to the formation of PSRs (e.g., Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Rubin et al., 1985; Rubin & McHugh, 1987). PSRs refer to enduring, one-sided socio-emotional bonds between media users and media personas (Rubin et al., 1985; Rubin & Perse, 1987), which typically evolve from initial parasocial interactions (PSIs) as originally conceptualized by Horton and Wohl (1956). These relationships tend to develop in ways that mirror non-mediated, interpersonal ones (Branch et al., 2013; Lakey et al., 2014). The audience develops this bond with SMIs through daily content observation, participation in related discussion groups, and attempts to engage via comments, tags, or other attention-seeking methods (Liu, 2025). However, recent research has also highlighted the complexity and dynamics of PSRs by describing the relationship between SMIs and their followers as characterized by greater interaction and reciprocity, connected to the social media context (Lou, 2022).

In line with the concept PSRs, Russell et al. (2004) introduced the construct of connectedness with media characters, which captures the various faces of relationships that followers could develop with a SMI. This construct is conceptualized as a spectrum reflecting varying levels of intensity in the bond with media figures, each corresponding to a distinct parasocial pattern. At the low end of the spectrum, “escape” represents passive and temporary entertainment, where viewers feel positive toward characters without forming deeper involvement. At the high end, “paraphernalia” refers to obsessive engagement, where viewers integrate media figures into their daily lives through frequent interaction and the collection of related objects.

Between these poles lie intermediate stages such as “fashion”, “imitation”, “modeling”, and “aspiration”, which involve increasing cognitive and emotional engagement. “Fashion” reflects influence over clothing and style choices. “Imitation” refers to the viewers’ inclinations to replicate the media character’s words, voice, and behaviors, instead “modeling” refers to the degree to which individuals relate their own life to the lives of the media character. Imitation and modeling refer both to processes of identification. Finally, “aspiration” denotes the desire to emulate the character as a personal ideal. Lastly, with a greater degree of connectedness, there is “aspiration”, which refers to the desire to become closely like one’s media character, such as aspiring to occupy the same role (Russell et al., 2004).

Due to the characteristics and potential impact of PSRs with SMIs, a growing body of research has begun to investigate their associations with social adjustment across different developmental stages (e.g., Hartmann, 2017). Specifically, late adolescence and young adulthood, marked by greater opportunities for self-exploration as parental control decreases and normative pressures remain low (Arnett, 2023), combined with increased access to new communication technologies, create a context in which parasocial processes can significantly influence identity formation and socialization, leading to both potential negative (Chae, 2018; Ezzat, 2020; Y.-H. Lee et al., 2021; Lowe-Calverley & Grieve, 2021) and positive outcomes (Bond, 2018; Chauvin et al., 2024). Moreover, research has shown that media and PSRs not only impact offline socialization processes but also that offline relationships can influence parasocial processes and media consumption (Genner & Süss, 2017). For example, studies focused on the COVID-19 pandemic period demonstrated that people increasingly relied on PSRs via social media, aligning with previous research on how social deprivation, whether due to isolation or long-term remote work, can heighten engagement in parasocial interactions (Jarzyna, 2021).

However, the literature review highlights the need for further research on factors that contribute to the development of connections with SMIs (e.g., Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Liebers & Schramm, 2019; Tukachinsky et al., 2020).

Social Connectedness and Connectedness With SMIs

Scholars underline that new communication technologies play a crucial role in the development and maintenance of social connectedness, especially for adolescents and young adults (Wu et al., 2016). According to R. M. Lee and Robbins (1995), social connectedness is an internal sense of belonging, defined as the subjective awareness of closeness with others. This sense is developed through social experiences and influences one's perception of the world and one’s self-esteem (R. M. Lee & Robbins, 1998, Lee et al., 2001). It is crucial for forming significant relationships and developmental tasks especially from adolescence to adulthood (Moore, 2006). Indeed, individuals with low social connectedness often feel isolated, struggle with belonging, and have negative self and other perceptions, including distrust (Allen et al., 2021; R. M. Lee & Robbins, 1998).

With regard to the link between social connectedness and the bond with SMIs, research points out contradictory results (e.g., Tukachinsky et al. 2020). For example, it has been demonstrated that young people with insecure attachment styles may develop strong PSRs with a SMI to fulfill social needs (Dinkha et al., 2015). Additionally, scholars have noted that high involvement with media figures or SMIs is associated with a greater sense of loneliness and distrust in offline social relationships compared to face-to-face relationships (Baek et al., 2013). Taken together, these results support the parasocial compensation or substitution hypothesis, suggesting that parasocial experiences, including those with SMIs, are sought to compensate for poor social adjustment, thereby representing an additional risk (e.g., Liebers & Schramm, 2022; Madison et al., 2016; Vandebosch & Eggermont, 2002).

On the other hand, some literature suggests that connections with media characters and SMIs can enrich social experiences by fostering a sense of closeness and friendship, enhancing perceived social support, increasing feelings of social connection, and strengthening the sense of community (e.g., Blight et al., 2017; Bond, 2018; Hartmann, 2017; Hoffner & Bond, 2022). Offering a possible explanation for these conflicting results and underlining a lack of significant correlation between social deficiencies and parasocial experiences, a recent meta-analysis by Tukachinsky et al. (2020) suggested that the bond with media characters and SMIs represents an extension of social relationships rather than a replacement. This perspective underscores not only the similarity to face-to-face social relationships but also their inherent complexity. Indeed, these conclusions align with Giles’ interpretative model (2002), which places parasocial processes within a continuum that describes social relationships. In this framework, parasocial bonds can be linked to individual relational styles observed in offline contexts. However, Liu and J.-S. Lee (2024) demonstrated that interactions with SMIs can lead to feelings of loneliness through the increase of PSRs and social support. Thus, as an online phenomenon, some scholars have examined the development of bonds with SMIs in connection with social interactions specifically originating from online sources, such as social media (Grieve et al., 2013; Riedl et al., 2013; Valkenburg & Peter, 2009). For example, it has been demonstrated that the amount of social media use and engagement with an online community predicts increased parasocial interaction, which in turn leads to increased community participation (Ballantine & Martin, 2005; Gong & Huang, 2023; Liu, 2025). Chung and Cho (2017) demonstrated that the engagement in an online fan community can reinforce the connection with a SMI, both because it provides the opportunity for interactions with the SMI or online celebrity and, in the case of non-participative community members, by allowing them to observe interactions between active members and the SMI or celebrity reinforcing community involvement and connectedness with the SMI (Ballantine & Martin, 2005). These studies raise further questions about the differentiation of online contexts and their use. In many cases, individuals’ offline and online lives intersect (Subrahmanyam et al., 2008), while in others, social media create spaces for friendships and interactions that originate and remain exclusively online (van Zalk et al., 2014). Both types of online interactions, those that strengthen offline relationships and those that exist solely in digital spaces, can shape the perception of social connection across online and offline contexts (Riedl et al., 2013; van Zalk et al., 2014), with potential different effects on parasocial processes, which should be further explored.

In summary, the literature presents two complementary perspectives on the relationship between social connectedness and parasocial bonds. On one hand, several scholars suggest that PSRs may reflect an extension of real-life relational competencies and status (Giles, 2002; Hartmann, 2017; Tukachinsky et al., 2020). Based on this view, we expect that offline social connectedness will be positively associated with identification, aspiration, and modeling with SMIs, such as constructive dimensions of engagement with them. On the other hand, evidence also points to a compensatory function of parasocial relationships, especially for individuals who experience low levels of offline connectedness. In such cases, PSRs may serve as a form of escape or substitution for offline ties (Baek et al., 2013; Tukachinsky & Dorros, 2018). Therefore, we hypothesize that higher offline social connectedness will be negatively associated with the use of SMIs for escape. Finally, interactions within online communities and social media environments appear to enhance the sense of connection with SMIs by enabling both direct and vicarious engagement (Ballantine & Martin, 2005; Chung & Cho, 2017; Liu, 2025). In line with this, we expect that both exclusively online and combined offline–online social connectedness will be positively associated with all dimensions of parasocial connectedness.

Social Self-Efficacy and Connectedness With SMIs

Adolescents and young adults often choose SMIs as sources of inspiration in developing socio-emotional skills (Chauvin et al., 2024; Taddeo, 2023; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). In other words, they actively select online role models to guide them through social developmental tasks. Observing SMIs may serve as a form of vicarious learning, reinforcing individuals’ beliefs in their ability to initiate and manage social interactions, defined as social self-efficacy (Di Giunta et al., 2010). According to Bandura (1977), self-efficacy also influences the choice of role models, affecting whether individuals seek attainable versus idealized social targets. Although high levels of social self-efficacy have been linked to psychosocial adjustment and adaptive social media use (Connolly, 1989; Valkenburg et al., 2017), limited evidence exists regarding its direct role in the formation of parasocial bonds with SMIs. Some scholars have found that PSRs with SMIs perceived as positive and realistic role models are associated with increased self-efficacy in specific domains (Ezzat et al., 2020; Phua, 2016). Conversely, identifying with unrealistic media figures may foster negative self-comparisons and lower self-esteem (Eyal & Te’eni-Harari, 2013).

Taken together, these findings suggest that social self-efficacy may influence how individuals perceive and internalize media content from SMIs, particularly affecting their inclination to imitate and emulate figures they perceive as successful. Therefore, we hypothesize that higher levels of social self-efficacy are positively associated with those dimensions of parasocial connectedness that are most closely tied to modeling and identification processes, i.e., namely, imitation, modeling, and aspiration. In contrast, low levels of social self-efficacy may lead individuals to gravitate toward idealized, unattainable figures, using them primarily as tools for escape rather than realistic sources of inspiration.

Problematic Social Media Use and Connectedness With SMIs

Previous studies demonstrated that the attachment to a SMI, and a strong sense of belonging to the influencer’s community, could lead to problematic engagement with them, such as the necessity to constantly check or find contact with favorite SMI, which is associated with internet and social media problematic use (Baek et al., 2013; Farivar et al., 2022; Naranjo-Zolotov et al., 2021). Scholars have revealed that internet and social media addiction, an increasing phenomenon with prevalence rates ranging from 0 to 82%, primarily affects adolescents and young adults (Chang et al., 2022). Excessive or problematic internet and social media use is conceived as a behavioral disorder, with symptoms resembling those of behavioral addictions. Specifically, social media addiction, a specific form of internet addiction, includes using social media excessively, having an unsatisfied desire to use social media, neglecting other activities, having disrupted social relations, using social media as an escape from negative emotions and life stress, having difficulty in reducing use, being nervous and anxious when unable to use, and deceiving others about the duration and amount of use (Turel & Serenko, 2012; van den Eijnden et al., 2016).

Generally, excessive or problematic internet usage has been linked to online community dependency, which in turn increases interaction with a SMI (Ballantine & Martin, 2005). Specifically, social media addiction has been related to a negative impact on the perception of face-to-face social connections (Savci & Aysan, 2017), leading to a tendency to fulfill communication and connection needs through social media and predisposing individuals to parasocial interactions and relationships (de Bérail & Bungener, 2022; Hartmann, 2017; Tatem & Ingram, 2022). Therefore, this study examines whether higher levels of problematic social media use are associated with stronger parasocial connectedness with SMIs across all its dimensions, from escape oriented interactions to deeper processes of identification, such as imitation, modeling, and aspiration.

Demographics Variables (i.e., Age, Sex) and Connectedness With SMIs

Beyond psychosocial predictors, sociodemographic characteristics such as age, sex, and cultural background have also been considered in the literature as relevant factors in shaping parasocial experiences. Research has shown that young people generally exhibit stronger bonds with SMIs compared to older individuals (Liebers & Schramm, 2019). Specifically, during adolescence and into young adulthood, a period characterized by raised interest in social media, PSRs and connections with SMIs are more common as they address various needs related to identity and relational changes (Eyal et al., 2020; Gleason et al., 2017; Madison et al., 2016). In line with the literature, in the present study, age will be examined as a predictor of parasocial involvement across its multiple dimensions, with the expectation that younger individuals will report higher levels of engagement with SMIs.

Furthermore, most of the literature indicates that women report stronger parasocial bonds than men (Liebers & Schramm, 2019), possibly because women and girls tend to be more active on social media platforms (Baiocco et al., 2016). However, sex differences in PSRs are not limited to their intensity or frequency. Research has also shown that male and female users differ in their preferences for SMI content (Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017) and in their engagement styles (Gleason et al., 2017). For instance, Gleason et al. (2017) found that boys and girls perceive parasocial relationships differently in terms of relational symmetry: boys are more likely to view media figures as authority figures or mentors, while girls tend to imagine more egalitarian and reciprocal relationships, often engaging more effectively with SMIs. Thus, given the mixed findings in prior research, sex will be examined using an exploratory approach, with particular attention to potential differences across the various facets of parasocial bonds with SMIs.

Country Differences in Connectedness With SMIs

Additionally, research has explored parasocial dynamics based on sample national origin and cultural background. Although some studies suggest that cultural background may shape how users perceive and appreciate the same media characters Liebes & Katz, 1990; Schmid & Klimmt, 2011), other research has found no significant differences in the factors influencing or resulting from PSRs between collective and individualist cultures (Tukachinsky et al., 2020). Regarding the specific comparison between two individualistic and Western countries, Italy and the Netherlands, a comparative study by Trombin and Veglianti (2020) revealed differences limited to influencer type and content preferences: Italian respondents tended to favor local micro-influencers and preferred informative or debunking content, while Dutch respondents were more drawn to visually appealing and aesthetic-driven formats. Reuter et al. (2019) found that Italian and Dutch respondents exhibited similar digital socialization practices, including comparable levels of media use and trust in online information sources. Taken together, these findings suggest that while cultural background may shape preferences for the form and content of engagement with SMIs, the underlying mechanisms of parasocial connectedness appear to remain broadly consistent across Italy and the Netherlands. While these findings indicate that the broader mechanisms underpinning parasocial connectedness may remain relatively stable across the two contexts, they also suggest that cultural background can influence specific preferences in how audiences engage with SMIs. Therefore, further research is needed to disentangle the respective roles of nationality, cultural values, and media ecosystems in shaping users’ engagement with SMIs.

The Current Study

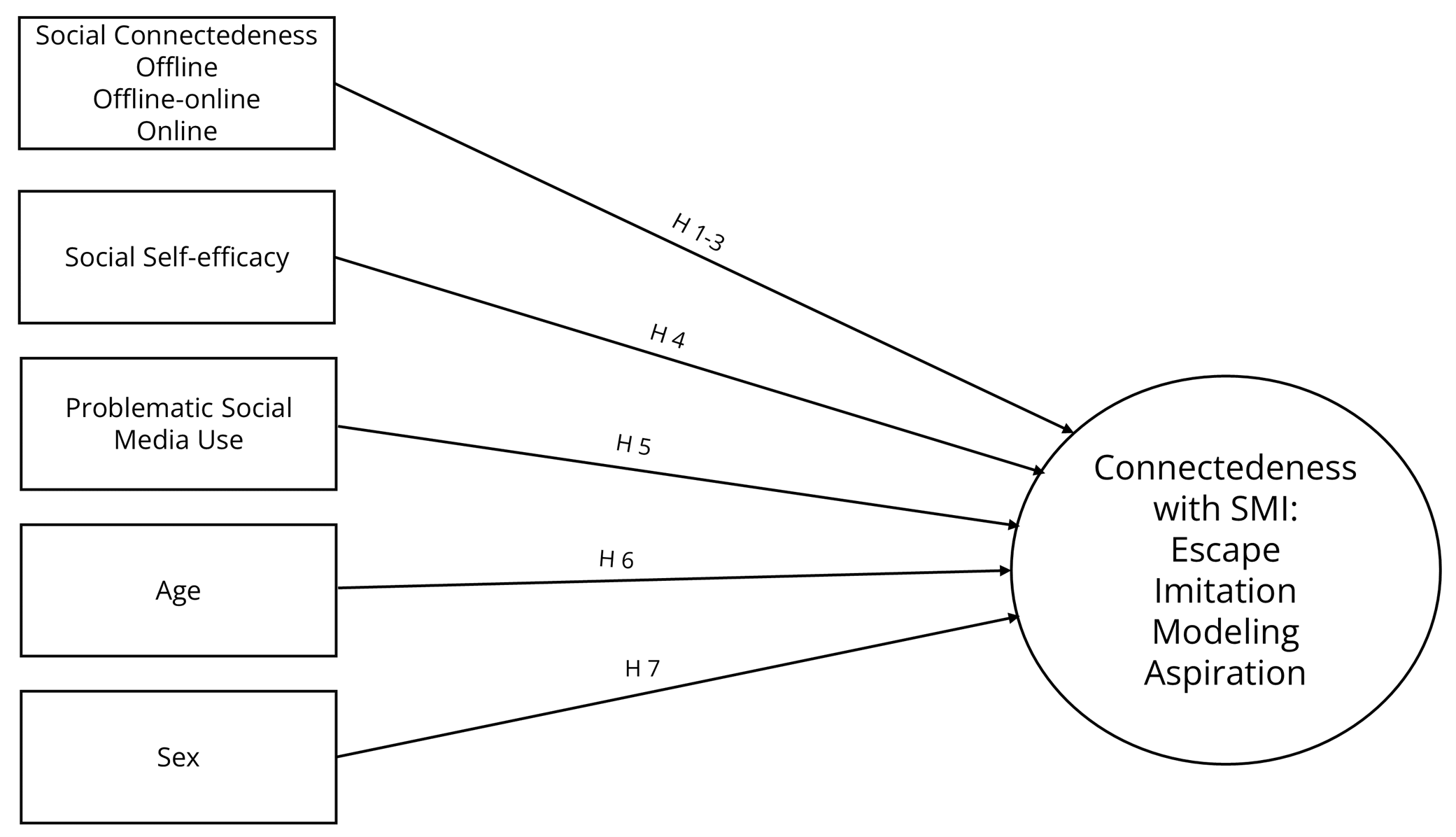

The present study aims to examine how different sources of social connectedness (offline, combined offline–online, exclusively online), social self-efficacy, problematic social media use, and demographic variables (age, sex, and country) predict various dimensions of connectedness with one’s favorite SMI, as conceptualized by Russell et al. (2004) among Italian and Dutch young adults. We focus specifically on four dimensions, escape, imitation, modeling, and aspiration, which are particularly relevant for understanding relational engagement with SMIs. In contrast, we exclude “fashion” and “paraphernalia,” which are more commonly investigated in the context of influencer marketing or traditional media celebrities.

Below, we outline the specific objectives and related hypotheses.

Social Connectedness and Connectedness With SMIs

Literature suggests that individuals with strong offline relationships are more likely to engage in meaningful parasocial processes (Giles, 2002; Hartmann, 2017; Tukachinsky et al., 2020). Conversely, lower offline connectedness has been linked to using media figures as compensatory substitutes (Baek et al., 2013; Tukachinsky & Dorros, 2018). Meanwhile, exclusively online and combined social connectedness may enhance engagement with SMIs by increasing access to parasocial interaction opportunities and social reinforcement (Ballantine & Martin, 2005; Liu, 2025).

H1a. Offline social connectedness is negatively associated with escape.

H1b. Offline social connectedness is positively associated with imitation toward SMIs.

H1c. Offline social connectedness is positively associated with modeling toward SMIs.

H1d. Offline social connectedness is positively associated with aspiration toward SMIs.

H2a-d: Combined offline–online social connectedness is positively associated with a) escape, (b) imitation, (c) modeling, and (d) aspiration.

H3a-d: Online social connectedness is positively associated with (a) escape, (b) imitation, (c) modeling, and (d) aspiration.

Social Self-Efficacy and Connectedness With SMIs

Respondents with high social self-efficacy are more likely to choose attainable role models and to internalize their behaviors in a constructive manner (Chauvin et al., 2024; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). Conversely, individuals with low levels of social self-efficacy may tend to select idealized and unrealistic models or engage with them through escape-oriented motivations (Eyal & Te’eni-Harari, 2013).

H4a. Social self-efficacy is negatively associated with escape toward SMIs.

H4b. Social self-efficacy is positively associated with imitation toward SMIs.

H4c. Social self-efficacy is positively associated with modeling toward SMIs.

H4d. Social self-efficacy is positively associated with aspiration toward SMIs.

Problematic Social Media Use and Connectedness With SMIs

Problematic social media use has been associated with stronger parasocial attachment and emotional reliance on SMIs (Ballantine & Martin, 2014; de Bérail & Bungener, 2022; Hartmann, 2017; Tatem & Ingram, 2022). Individuals may seek out SMIs to fulfill entertainment and relational needs, increasing engagement across all parasocial dimensions.

H5a-d. Problematic social media use is positively associated with (a) escape, (b) imitation, (c) modeling, and (d) aspiration.

Demographic Variables and Connectedness With SMIs

Developmental literature indicates that parasocial bonds are more frequent and intense during adolescence and young adulthood (Liebers & Schramm, 2019; Eyal et al., 2020). Additionally, the literature presents mixed findings regarding sex differences in parasocial processes. While some studies report stronger PSRs among females (Liebers & Schramm, 2019), others emphasize differences in the quality and nature of parasocial involvement (Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017; Gleason et al., 2017).

H6a-d. Younger age is positively associated with (a) escape, (b) imitation, (c) modeling, and (d) aspiration.

H7a-d. Sex is associated with (a) escape, (b) imitation, (c) modeling, and (d) aspiration. However, regarding the specific directions of the associations across the individual dimensions, we adopt an exploratory approach.

Country Differences in Connectedness With SMIs

Lastly, the hypothesized model will be tested among samples collected in two countries, Italy and the Netherlands. By means of multigroup modeling, potential country differences in the hypothesized relationships will be investigated. However, previous studies suggest minimal differences in digital socialization and PSR development across these two contexts (Reuter et al., 2019; Trombin & Veglianti, 2020).

Figure 1. Hypothesized Model.

Methods

Respondents and Procedure

Cross-sectional data via an online survey were collected between March 2022 and June 2022, both in Italy and the Netherlands. An inclusion criterion for the present study was to follow at least one SMI. Specifically, only respondents who answered yes to the following question, Do you follow any influencers through your social media profiles (e.g., Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, etc.)? were included in the sample. Therefore, the total sample resulted in a total of 554 respondents (346 from Italy and 208 from Netherland) aged 17 to 28 years old (Mage = 21.14; SDage = 2.56; 78.0% girls). Of the Italian sample, two respondents were non-Italian (99.42% had the Italian nationality), whereas of the Dutch sample, 72 respondents were non-Dutch (65.39% had the Dutch nationality). Although 34.61% of participants in the Dutch sample reported a non-Dutch nationality, all were enrolled at Tilburg University and shared the same academic and sociocultural environment. Therefore, the categorization of Italian and Dutch students was based not only on self-reported nationality but also on the institutional context in which participants were embedded. The required sample size was 543, this number resulted from a power analysis conducted in G*Power 3.1.9.7 (Faul et al., 2009) for linear multiple regressions with a rather small effect size (f² = .05), with an ɑ error probability of .05 and 13 predictors (including the interactions with country, see subchapter Data Analysis) for each dependent variable. The sample is composed of Bachelor and Master students recruited from Italian and Dutch Universities. An English version of the questionnaire was shared between Italian and Dutch researchers. Therefore, before starting data collection, Italian researchers worked on a language adaptation of the survey. Native speaker researchers translated and back-translated the survey. Then, the two final versions (Italian and English) were compared. This process did not highlight any specific differences between the Italian and English versions of the survey. Finally, two survey links have been created and shared on the Qualtrics platform: one in English for the students at the Tilburg University, and one in Italian for the students at the Mediterranea University. Specifically, Dutch respondents completed the English version, as Tilburg University is an international institution where English is the primary language of instruction and all students demonstrate at least B2/C1 proficiency, ensuring full comprehension of the study materials. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sapienza University of Rome and the Research Ethics and Data Management Committee of Tilburg University. Respondents were invited to take part in a study through university mailing lists. The participation was voluntary and unpaid. The anonymity was guaranteed, and respondents gave their informed consent by clicking on yes, I accept to participate on the first page of the survey. Only the questionnaires filled out were considered valid among all the respondents reached. Thus, the response rate was 93%. The duration of the survey was 30–35 min.

Measures

Socio-Demographic Information

Respondents reported their age, sex (0 = male; 1 = female).

Connectedness With SMIs

To measure the intensity of PSRs that respondents develop with their favorite influencer(s) adapted version of four subscale of Connectedness Scale (CA; Russel et al., 2004) were used. Specifically, Escape, Imitation, Modeling, and Aspiration subscales were included in the survey. Escape (3 items) refers to the degree in which following influencers helps people to forget about their problems (e.g., Watching my favorite influencer’s posts and videos is an escape for me); Imitation (3 items) relates to the inclination for people to imitate their favorite influencers (e.g., I try to speak like my favorite influencer); Modeling (3 items) measures a social learning process by capturing the degree to which individuals relate their own life to the lives of their favorite influencers (e.g., I get ideas from my favorite influencer's posts and videos about how to interact in my own life); Aspiration (2 items) refers to the desire to be as the favorite influencer and meet the favorite influencer expressed by respondents (i.e., I would love to be an influencer; I would love to meet my favorite influencer). Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree.

Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFAs) for the Italian and Dutch sample separately to confirm the structure of the four subscales of connectedness with an influencer were performed. The fit indices of the CFA for each sample indicated a good fit: (1) Italian sample: CFI = .959; RMSEA = .085, 90% CI [.070, .100]; χ² (38) = 141.74, p < .001; and (2) Dutch sample: CFI = .975; RMSEA = .051, 90% CI [.026, .074]; χ² (38) = 61.44, p < .01. Standardized factor loadings of the items of the four subscales ranged between .50 and .92. for the Italian sample and between .48 and .92 for the Dutch sample. These four forms of connectedness with SMIs are included in the analyses as latent variables (each formed by the number of items described above). To test whether the factor loadings of these four latent constructs are different for Italian and Dutch respondents (invariance testing), the fit values of a model assuming group invariance (the same factor structure for Italian and Dutch respondents; fully constrained model; χ²(94) = 360.503, p < .001) were compared with the fit values of a model in which group invariance was not assumed (different factor structure for Italian and Dutch respondents; χ²(83) = 318.045, p < .001). This comparison showed a significant difference between the chi-square values of the unconstrained model and the fully constrained model (Δχ² = 42.458, Δdf = 11, p < .001). This indicates that the factor loadings differ for the two samples and group comparisons should be interpreted cautiously. The Cronbach’s Alphas of each form of connectedness with SMIs are reported in Table 1. Note that Cronbach’s Alpha for ‘Aspiration’ is low, therefore results related to this dimension should also be interpreted with caution.

Social Connectedness in Offline, Offline-Online and Exclusively Online Contexts

To measure enduring interpersonal closeness related to social interactions with peers (i.e., not influencers or celebrities), 9 items from the Social Connectedness Scale (Lee et al., 2001) and the Online Social Connectedness Scale (Riedl et al., 2013) were adapted for offline, offline-online, and exclusively online contexts, respectively. Respondents rated their feelings of closeness, connection and ability to connect with people on a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree. Items related to the offline context refer to face-to-face situations or interactions (e.g., I feel disconnected from the real world around me). Items related to the offline-online context refer to online interactions with social media contacts who are also known in face-to-face settings (e.g., I feel disconnected from my social media network—think only of contacts you also know in real life). Finally, items related to the exclusively online context refer to interactions with social media contacts who are exclusively known and engaged in online contexts (e.g., I feel disconnected from the social media world around me—think only of contacts you exclusively know online). Negatively worded items were reverse-coded. Thus, a higher score represents a stronger connection with people in a diverse context.

Two CFAs were performed to test the structure of the subscales of social connectedness in different contexts (offline, offline-online, and exclusively online, see next paragraphs) for both countries. Because of low factor loadings of multiple items, four items were deleted (same four items for each context). Based on the remaining five items, a composite mean score was calculated for each context. The fit of the CFAs were acceptable after deletion of the four items for each context in each sample: (1) Italian sample: CFI = .932; RMSEA = .086, 90% CI [.077, .096]; χ² (84) = 348.65, p < .001; and (2) Dutch sample: CFI = .950; RMSEA = .073, 90% CI [.059, .087]; χ²(84) = 188.50, p < .001. Standardized factor loadings of the items ranged between .62 and .86 in the Italian sample and between .71 and .87 in the Dutch sample. The Cronbach’s Alpha for each subscale is reported in Table 1.

Perceived Social Self-Efficacy

To assess individuals’ beliefs in their capability to initiate and maintain social relationships, work cooperatively, and share personal experiences with others the Perceived Social Self-Efficacy (PSSE; Di Giunta et al., 2010) was utilized. respondents were asked to respond to five items on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 = Not well at all to 5 = Very well (e.g., How well can you express your opinion to people who are talking about something of interest to you?). The Cronbach’s Alpha is reported in Table 1. Two CFAs were performed to test, for each country, the structure of the perceived social self-efficacy scale. The fit statistics of both CFAs were good (Italian sample: CFI = .989; RMSEA = .064, 90% CI [.023, .106]; χ² (5) = 13.48, p = .019; and (2) Dutch sample: CFI = .977; RMSEA = .058, 90% CI [.000, .126]; χ²(5) = 10.32, p = .067., standardized factor loadings of the five items ranged between .70 and .80 for the Italian sample and between .46 and .73 for the Dutch sample. The Cronbach’s Alphas are reported in Table 1.

Problematic Social Media Use

The Social Media Disorder Scale (van den Eijnden et al., 2016). Problematic social media use was assessed using 9 items from the Social Media Disorder Scale (van den Eijnden et al., 2016). Respondents were asked to answer questions thinking about their behaviors and feelings when they used social media in the last year (e.g., During the past year, have you regularly felt dissatisfied because you wanted to spend more time on social media?). Items rated on a five-point scale from 1 = Never to 5 = Always. Two CFAs were performed to test, for each country, the structure of the problematic social media use scale. The fit statistics of both CFAs were relatively low (Italian sample: CFI = .803; RMSEA = .161, 90% CI [.146, .177]; χ²(27) = 323.35, p < .001; and (2) Dutch sample: CFI = .804; RMSEA = .131, 90% CI [.109, .153]; χ²(27) = 134.70, p < .001. Standardized factor loadings of the five items ranged between .50 and .74 for the Italian sample and between .41 and .72 for the Dutch sample. The Cronbach’s Alphas (.85 for the Italian sample and .80 for the Dutch sample) are reported in Table 1.

Data Analysis

The data described in this article are openly available at https://osf.io/kxc5u. In order to test the hypothesized model, structural equation modeling with Maximum Likelihood Estimation was used in Mplus v7.4, consisting of both latent and observed variables. More precisely, all variables were included in the model as observed variables, except for the dependent variables, which were the four subscales of connectedness with an influencer (Escape, Imitation, Modeling, and Aspiration). There were no missing values for all variables included. In a first step, the structural model was tested for the whole sample (including both Italian and Dutch respondents). In a second step, a multigroup analysis with country as grouping variable was calculated to allow different parameter estimates for Italian and Dutch respondents.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Cronbach’s Alphas for the Italian and Dutch Samples.

|

|

M (I) |

SD (I) |

α (I) |

Range (I) |

M (D) |

SD (D) |

α (D) |

Range (D) |

|

Escape |

3.93 |

1.83 |

.89 |

1–7 |

4.54 |

1.52 |

.86 |

1–7 |

|

Imitation |

2.25 |

1.57 |

.87 |

1–7 |

3.03 |

1.38 |

.77 |

1–7 |

|

Modeling |

2.67 |

1.60 |

.88 |

1–7 |

3.51 |

1.46 |

.81 |

1–7 |

|

Aspiration |

4.05 |

1.70 |

.42 |

1–7 |

4.02 |

1.45 |

.55 |

1–7 |

|

Social connectedness in the offline context |

5.48 |

1.50 |

.89 |

1–7 |

5.16 |

1.39 |

.92 |

1–7 |

|

Social connectedness in the offline-online context |

4.92 |

1.38 |

.87 |

1–7 |

4.58 |

1.24 |

.86 |

1–7 |

|

Social connectedness in the online context |

4.14 |

1.71 |

.90 |

1–7 |

3.76 |

1.33 |

.88 |

1–7 |

|

Social self-efficacy |

3.96 |

0.80 |

.84 |

1–5 |

3.86 |

0.68 |

.74 |

1–5 |

|

Problematic social media use |

2.08 |

0.77 |

.85 |

1–5 |

2.15 |

0.63 |

.80 |

1–5 |

|

Age |

21.55 |

2.60 |

— |

17–28 |

20.43 |

2.26 |

— |

17–28 |

|

Sex |

0.85 |

0.37 |

— |

0–1 |

0.69 |

0.47 |

— |

0–1 |

Results

Testing the Hypothesized Model

The fit indices of the structural model, for the whole sample, had an acceptable fit: CFI = .955; RMSEA = .057, 90% CI [.049, .065]; χ²(87) = 243.108, p < .001. Unstandardized and standardized paths are presented in Table 3. All four subscales of connectedness with an influencer were significantly positively correlated with each other, with standardized correlation coefficients ranging from .45 to .59 (Table 2).

For the first subscale of connectedness with an influencer, escape, the model showed that social connectedness in the offline and offline–online contexts was significantly and negatively related to this dimension, whereas social connectedness in the online context was positively related. Specifically, individuals who feel less interpersonally close to others in the offline and offline-online contexts tend to perceive their favorite influencer as helping them forget their problems, whereas those who feel more interpersonally connected to others in online contexts report higher scores on escape. These results are consistent with H1a and H3a, but not with H2a. Furthermore, problematic social media use and sex were significantly associated with escape, meaning that those with more problematic social media use feel more strongly that their favorite influencer helps them with forgetting their problems and males scored higher on escape compared to females. These results are in line with H5a and H7a. The included variables in the model explained 13.7% of the variance of escape (R²). The detailed statistical results are reported in Table 3.

Second, regarding imitation, the model showed a significant negative association with social connectedness in the offline-online context and a significant positive association with social connectedness in the online context, which indicates that those who feel interpersonally less close with others in the offline-online context are more likely to imitate their favorite influencer, whereas those who feel interpersonally more close with others exclusively in the online context are more likely to imitate their favorite influencer. No significant association emerged with social connectedness in the offline context. These findings are consistent with H3b, but not with H1b or H2b. Furthermore, in line with H5b, a significant positive association was also found between problematic social media use and imitation, meaning that those who are more strongly addicted to social media are more inclined to imitate their favorite influencer. Finally, age and sex were found to be associated with imitation: younger and male adults were more inclined to imitate their favorite influencer. These results are in line with H6b and H7b. Together, the included variables in the model explained 24.6% of the variance of imitation (R²). The detailed statistical results are reported in Table 3.

For the third subscale of connectedness with an influencer, modeling, problematic social media use was significantly associated with this dimension, confirming H5c. This means that young adults who score higher on problematic social media use relate their own life stronger to the lives of their favorite influencer. Age and sex were found to be associated with modeling: younger and male adults were more likely to relate their own life stronger to the lives of their favorite influencer. These findings are in line with H6c, and H7c. All included variables explained together 14.0% of the variance in modeling (R²). The detailed statistical results are reported in Table 3.

Finally, for the fourth subscale, aspiration, significant associations were found with social self-efficacy, problematic social media use, age, and sex. These results are consistent with H4d, H5d, H6d, and H7d. Young adults who score higher on problematic social media use and social self-efficacy, who have a younger age, and males are associated with a greater desire to be as their favorite influencer and meet their favorite influencer. In total, the included variables explained 28.7% of the variance in aspiration (R²). The detailed statistical results are reported in Table 3.

Table 2. Correlation Coefficients Between Variables.

|

|

1. |

2. |

3. |

4. |

5. |

6. |

7. |

8. |

9. |

10. |

11. |

|

1. Escape |

— |

.42*** |

.19** |

.28*** |

–.11 |

–.06 |

–.01 |

.02 |

.23*** |

–.06 |

–.06 |

|

2. Imitation |

.49*** |

— |

.32*** |

.30*** |

–.10 |

–.09 |

.10 |

–.08 |

.20** |

–.11 |

–.12 |

|

3. Modeling |

.57*** |

.58*** |

— |

.44*** |

–.28*** |

–.21*** |

.08 |

–.16** |

.37*** |

–.12* |

–.05 |

|

4. Aspiration |

.44*** |

.42*** |

.44*** |

— |

–.02 |

.05 |

.09 |

.00 |

.33*** |

–.29*** |

–.12* |

|

5. Social connectedness in the offline context |

−.22*** |

–.24*** |

–.28*** |

–.15** |

— |

.42*** |

.14* |

.42*** |

–.37*** |

.03 |

.06 |

|

6. Social connectedness in the offline-online context |

–.18*** |

–.18*** |

–.21*** |

–.07 |

.57*** |

— |

.37*** |

.54*** |

–.10 |

.11 |

–.01 |

|

7. Social connectedness in the online context |

.05 |

.01 |

–.01 |

.02 |

.20*** |

.39*** |

— |

.28*** |

–.30*** |

–.06 |

.04 |

|

8. Social self-efficacy |

–.10 |

–.17*** |

–.16** |

.04 |

.11 |

.26*** |

.03 |

— |

–.34*** |

.14 |

.02 |

|

9. Problematic social media use |

.27*** |

.33*** |

.37*** |

.33*** |

–.37*** |

–.30*** |

–.11* |

.06 |

— |

–.26*** |

–.22*** |

|

10. Age |

–.09 |

–.13* |

–.12* |

–.29*** |

–.15* |

.03 |

.01 |

.02 |

–.34*** |

— |

.04 |

|

11. Sex (0 = male, 1 = female) |

–.13* |

–.20*** |

–.12 |

–.12* |

–.08 |

.06 |

.00 |

.04 |

.23*** |

–.01 |

— |

|

Note. Correlations below the diagonal refer to the Italian sample, and those above the diagonal refer to the Dutch sample. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. |

|||||||||||

Table 3. Unstandardized and Standardized Paths of the Structural Model for Escape and Imitation in the Whole Sample (N = 554).

|

|

Connectedness with SMIs |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

Escape (R² = .137) |

Imitation (R² = .246) |

Modeling (R² = .140) |

Aspiration (R² = .287) |

||||||||||||

|

|

B |

SE |

β |

p |

B |

SE |

β |

p |

B |

SE |

β |

p |

B |

SE |

β |

p |

|

Social connectedness in the offline context |

−0.12 |

.06 |

−.12 |

.031 |

−0.08 |

.06 |

−.08 |

.130 |

−0.09 |

.06 |

−.08 |

.131 |

−0.06 |

.06 |

−.07 |

.289 |

|

Social connectedness in the offline-online context |

−0.13 |

.06 |

−.11 |

.038 |

−0.16 |

.06 |

−.14 |

.009 |

−0.10 |

.06 |

−.09 |

.102 |

−0.00 |

.06 |

−.00 |

.969 |

|

Social connectedness in the online context |

0.10 |

.04 |

.10 |

.025 |

0.10 |

.04 |

.10 |

.022 |

0.05 |

.05 |

.05 |

.255 |

0.05 |

.04 |

.08 |

.190 |

|

Social self-efficacy |

0.15 |

.09 |

.08 |

.105 |

0.03 |

.09 |

.01 |

.758 |

0.02 |

.10 |

.01 |

836 |

0.31 |

.09 |

.22 |

.000 |

|

Problematic social media use |

0.50 |

.10 |

25 |

.000 |

0.70 |

.09 |

.34 |

.000 |

0.59 |

.10 |

.28 |

.000 |

0.61 |

.11 |

.40 |

.000 |

|

Age |

−0.05 |

.03 |

−.08, |

.056 |

−0.08 |

.03 |

−.13 |

.002 |

−0.06 |

.03 |

−.09 |

.030 |

−0.12 |

.03 |

−.27 |

.000 |

|

Sex (0 = male, 1 = female) |

−0.59 |

.15 |

−.10, |

.016 |

−0.90 |

.15 |

−.25 |

.000 |

−0.34 |

.16 |

−.10 |

.016 |

−0.58 |

.11 |

−.22 |

.000 |

Analysis of Country Differences

To assess whether the associations differed between Italian and Dutch respondents, a multigroup analysis with country as grouping variable was performed. For this estimation, the hypothesized model was used f, all paths were allowed to vary by country; CFI = .921; RMSEA = .072, 90% CI [.064, .080]; χ² (188) = 458.73, p < .001. Tables 4.1 and 4.2 present the standardized paths and their p-value for each country. By means of t-tests, applying the formula of Keil et al. (2000, p. 315), the regression coefficients of each path for each of the two samples were compared (similar to, e.g., Brooks & Longstreet, 2015). These are also reported in Tables 4.1 and 4.2. We can conclude that the coefficients differed between the two countries. In particular, some of the hypothesized associations were significant in one country, but not in the other.

More precisely, for escape, social connectedness in the offline–online and online contexts, as well as sex, significantly predicted the outcome in the Italian sample but not in the Dutch one. In the Italian group, offline-online connectedness was negatively, whereas online connectedness was positively, related to escape, and a negative association with sex was also observed. In both samples, problematic social media use was significantly positively associated with escape.

Second, for imitation, in contrast to escape, social connectedness in the offline-online context and in the online context were significant predictors in the Dutch sample, but not in the Italian sample. Specifically, in the Dutch sample, social connectedness in the offline-online context was negatively related to imitation, whereas social connectedness in the online context was positively related. In both samples, problematic social media use and sex were significant predictors for imitation.

Third, for modeling, problematic social media use was a significant predictor in the Italian sample, but not in the Dutch sample. In the Italian group, higher levels of problematic social media use were positively associated with modeling. None of the other variables were significant predictors for modeling in both samples.

Fourth, for aspiration, social self-efficacy, age, and sex were significant predictors in the Italian sample but not in the Dutch sample. Specifically, among Italian participants, higher levels of social self-efficacy were associated with stronger aspirations toward SMIs, whereas younger and male participants reported a greater desire to resemble or meet their favorite influencer. In both samples, problematic social media use was significantly and positively related to aspiration.

Finally, it is also worth noting that the explained variance also differed between countries, being generally higher in the Italian sample, particularly for modeling, aspiration, and imitation.

Concluding Remarks

In the present results section, firstly results related to the whole sample were presented, as no differences between the countries were expected. However, the multigroup analyses did show some differences. Some of the hypothesized relationships were present in one sample, but not in the other, as described above. To conclude the results section, we want to highlight some of the significant associations that were found for the whole sample but not in the separate samples. Note that not any “new” significant associations emerged in the multigroup model in one sample, that were not found in the structural model for the whole sample.

The structural model for the whole sample indicated a negative association between social connectedness in the offline context and escape, but the multigroup model did not show any significant associations between these two variables in any of the two countries. Furthermore, age was found to be negatively associated with imitation in the structural model for the whole sample, but not in the multigroup model (for none of the two countries). Finally, age and sex were found to be significantly negatively associated with modeling in the structural model for the whole sample, but not in the multigroup model (for none of the two countries).

Table 4. Standardized Path Coefficients of the Multigroup Model for Escape and Imitation in Italian

and Dutch Respondents (N = 554) With T-Test Results to Compare Coefficients.

|

|

Connectedness with SMIs |

|||||||||||

|

|

Escape |

Imitation |

||||||||||

|

|

Italian |

Dutch |

t-test |

Italian |

Dutch |

t-test |

||||||

|

|

β |

p |

β |

p |

t |

p |

β |

p |

β |

p |

t |

p |

|

Social connectedness in the offline context |

−.09 |

.177 |

−.17 |

.056 |

8.78 |

< .001 |

−.12 |

.071 |

.04 |

.677 |

24.17 |

< .001 |

|

Social connectedness in the offline-online context |

−.15 |

.030 |

−.03 |

.732 |

18.84 |

< .001 |

−.09 |

.160 |

−.20 |

.026 |

13.86 |

< .001 |

|

Social connectedness in the online context |

.16 |

.005 |

.01 |

.929 |

25.33 |

< .001 |

.09 |

.092 |

.19 |

.016 |

18.68 |

< .001 |

|

Social self-efficacy |

.06 |

.334 |

.13 |

.117 |

12.17 |

< .001 |

.02 |

.679 |

−.02 |

.796 |

7.55 |

< .001 |

|

Problematic social media use |

.21 |

.001 |

.30 |

.000 |

16.42 |

< .001 |

.35 |

.000 |

.32 |

.000 |

4.50 |

< .001 |

|

Age |

−.09 |

.113 |

−.04 |

.564 |

9.30 |

< .001 |

−.09 |

.090 |

−.12 |

.114 |

3.84 |

< .001 |

|

Sex (0 = male, 1 = female) |

−.17 |

.001 |

−.12 |

.101 |

19.37 |

< .001 |

−.24 |

.000 |

−.18 |

.019 |

27.75 |

< .001 |

Table 5. Standardized Path Coefficients of the Multigroup Model for Modeling and Aspiration in Italian