How does Chinese millennials’ active social media use relate to their future goals? A moderated mediation model

Vol.17,No.1(2023)

China has achieved great economic and technological development, with the internet emerging as a further significant factor. Chinese millennials have grown up with the internet, which has shaped their ideas and behaviors. According to social change and human development theory, rapid development and popularization of communication technologies drive human change. Compared with traditional media, social media has become more integrated into people’s daily lives, which makes the effects of social media more potent. The current study tested the mediating role of desire for fame in relation to the connection between active WeChat use and future goals, including intrinsic and extrinsic goals. A sample of 422 Chinese university students completed a survey measuring active WeChat use, future goals, desire for fame, and narcissism. Results indicated that active WeChat use was associated with both extrinsic and intrinsic goals. Moreover, desire for fame mediated the association between active WeChat use and external and intrinsic goals. The mediation path linking active social media use to intrinsic goals differed from that linking active social media use to external goals. Compared with individuals with low-level narcissism, individuals with high-level narcissism who actively use WeChat were more likely to desire fame, which further drives them to pursue external goals. These findings advance understanding of how and when active WeChat use is associated with future goals for millennials, thus providing more empirical data at an individual level to enrich theory in the Chinese context.

active social media use; extrinsic goals; intrinsic goals; desire for fame; narcissism

Yu-Ting Hu

School of Business, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China; Key Laboratory of Adolescent Cyberpsychology and Behavior (CCNU), Ministry of Education, Wuhan, China

Yu-ting Hu is an assistant professor at the Business School of Jiangnan University. She works in cyber-psychology and internet consumption till now.

Yi-Duo Ye

School of Psychology, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou, China

Yi-Duo Ye is a professor at the Psychology School of Fujian Normal University. He focuses on cyber-psychology and adolescent mental health.

Jian-Zhong Hong

Key Laboratory of Adolescent Cyberpsychology and Behavior (CCNU), Ministry of Education, Wuhan, China; School of Psychology, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China

Jian-Zhong Hong is a professor at the Psychology School of Central China Normal University. He is interested in culture psychology and knowledge management in the internet environment.

Cai, H., Kwan, V. S. Y., & Sedikides, C. (2012). A sociocultural approach to narcissism: The case of modern China. European Journal of Personality, 26(5), 529–535. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.852

Cai, H., Zou, X., Feng, Y., Liu, Y. Z., & Jing, Y. M. (2018). Increasing need for uniqueness in contemporary China: Empirical evidence. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 554. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00554

Cain, N. M., Pincus, A. L., & Ansell, E. B. (2008). Narcissism at the crossroads: Phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(4), 638–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.006

China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). (2022). The 50th China statistical report on Internet development. http://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2022/0914/c88-10226.html

Deci, E. L., & Ryan. R. M. (2000). The ‘‘what’’ and ‘‘why’’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Fan, C.-y., Chu, X.-w., Zhang, M., & Zhou, Z.-k. (2019). Are narcissists more likely to be involved in cyberbullying? Examining the mediating role of self-esteem. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(15), 3127–3150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516666531

Fu, J., & Cook, J. (2020). Browsing for Cunzaigan on WeChat: Young people’s social media presence in accelerated urban China. YOUNG, 28(4), 404–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308819877787

Gentile, B., Twenge, J. M., Freeman, E. C., & Campbell, W. K. (2012). The effect of social networking websites on positive self-views: An experimental investigation. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1929–1933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.012

Gountas, J., Gountas, S., Reeves, R. A., & Moran, L. (2012). Desire for fame: Scale development and association with personal goals and aspirations. Psychology and Marketing, 29(9), 680–689. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20554

Greene, B. A., & Debacker, T. K. (2004). Gender and orientations toward the future: Links to motivation. Educational Psychology Review, 16(2), 91–120. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000026608.50611.b4

Greenfield, P. M. (2009a). Linking social change and developmental change: Shifting pathways of human development. Developmental Psychology, 45(2), 401–418. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014726

Greenfield, P. M. (2009b). Technology and informal education: What is taught, what is learned. Science, 323(5910), 69–71. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1167190

Greenfield, P. M. (2013). The changing psychology of culture from 1800 through 2000. Psychological Science, 24(9), 1722–1731. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613479387

Greenwood, D., Long, C. R., & Dal Cin, S. (2013). Fame and the social self: The need to belong, narcissism, and relatedness predict the appeal of fame. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(5), 490–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.020

Greenwood, D., McCutcheon, L. E., Collisson, B., & Wong, M. (2018). What's fame got to do with it? Clarifying links among celebrity attitudes, fame appeal, and narcissistic subtypes. Personality and Individual Differences, 131, 238–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.04.032

Halpern, D., Valenzuela, S., & Katz, J. E. (2016). “Selfie-ists” or “Narci-selfiers”?: A cross-lagged panel analysis of selfie taking and narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences, 97, 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.019

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Hu, Y.-T., Hong, J. Z., Ye, Y. D., & Chai, H. Y. (2021). Desire for fame in the era of internet: Studies and prospects. Journal of Huazhong Normal University (Humanities and Social Sciences), 60(1), 174–182. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-2456.2021.01.023

Hu, Y.-T., & Liu, Q.-Q. (2020). Passive social network site use and adolescent materialism: Upward social comparison as a mediator. Social Behavior and Personality, 48(1), Article e8833. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.8833

Huang, H., & Zhang, X. (2017). The adoption and use of WeChat among middle-aged residents in urban China. Chinese Journal of Communication, 10(2), 134–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2016.1211545

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.410

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(3), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296223006

Li, C., Shi, X., & Dang, J. (2014). Online communication and subjective well-being in Chinese college students: The mediating role of shyness and social self-efficacy. Computers in Human Behavior, 34, 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.032

Lin, K.-Y., & Lu, H.-P. (2011). Why people use social networking sites: An empirical study integrating network externalities and motivation theory. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(3), 1152–1161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.12.009

Liu, D., & Brown, B. B. (2014). Self-disclosure on social networking sites, positive feedback, and social capital among Chinese college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.003

Liu, Q.-Q., Zhang, D.-J., Yang, X.-J., Zhang, C.-Y., Fan, C.-Y., & Zhou, Z.-K. (2018). Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction in Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.06.006

Maltby, J. (2010). An interest in fame: Confirming the measurement and empirical conceptualization of fame interest. British Journal of Psychology, 101(3), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712609X466568

Maltby, J., Day, L., Giles, D., Gillett, R., Quick, M., Langcaster-James, H., & Linley, P. A. (2008). Implicit theories of a desire for fame. British Journal of Psychology, 99(2), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712607X226935

McHoskey, J. W. (1999). Machiavellianism, intrinsic versus extrinsic goals, and social interest: A self-determination theory analysis. Motivation and Emotion, 23(4), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021338809469

Michou, A., Vansteenkiste, M., Mouratidis, A., & Lens, W. (2014). Enriching the hierarchical model of achievement motivation: Autonomous and controlling reasons underlying achievement goals. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(4), 650–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12055

Moreno, M. A., & Whitehill, J. M. (2014). Influence of social media on alcohol use in adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Research Current Reviews, 36(1), 91–100. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4432862/

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12(4), 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1204_1

Muller, D., Judd, C. M., & Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2005). When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 852-863. https://doi.org/1.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852

Nadkarni, A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2012). Why do people use Facebook? Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.007

Niemiec, C. P., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2009). The path taken: Consequences of attaining intrinsic and extrinsic aspirations in post-college life. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(3), 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.09.001

Nostrand, D. F.-V., & Ojanen, T. (2022). Interpersonal rejection and social motivation in adolescence: Moderation by narcissism and gender. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 183(2), 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2021.2017258

Olasupo, M. O., & Idemudia, E. S. (2017). Influence of age, gender, and perceived self-control on future goals of children in adversities. Child Indicators Research, 10(4), 1107–1119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9439-2

Peat, C. M., Von Holle, A., Watson, H., Huang, L., Thornton, L. M., Zhang, B., Du, S., Kleiman, S. C., & Bulik, C. M. (2015). The association between internet and television access and disordered eating in a Chinese sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(6), 663–669. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22359

Pueschel, O., Schulte, D., & Michalak, J. (2011). Be careful what you strive for: The significance of motive-goal congruence for depressivity. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.697

Raskin, R., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 890–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.890

Santos, H. C., Varnum, M. E. W., & Grossmann, I. (2017). Global increases in individualism. Psychological Science, 28(9), 1228−1239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617700622

Shamloo, Z. S., & Cox, W. M. (2010). The relationship between motivational structure, sense of control, intrinsic motivation, and university students’ alcohol consumption. Addictive Behaviors, 35(2), 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.021

Sheldon, K. M., Gunz, A., Nichols, C. P., & Ferguson, Y. (2010). Extrinsic value orientation and affective forecasting: Overestimating the rewards, underestimating the costs. Journal of Personality, 78(1), 149–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00612.x

Sheldon, K. M., Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., & Kasser, T. (2004). The independent effects of goal contents and motives on well-being: It’s both what you pursue and why you pursue it. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(4), 475–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203261883

Sosik, J. J., Chun, J. U., & Zhu, W. (2014). Hang on to your ego: The moderating role of leader narcissism on relationships between leader charisma and follower psychological empowerment and moral identity. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1651-0

Southard, A. C., & Zeigler–Hill, V. (2016). The dark triad traits and fame interest: Do dark personalities desire stardom? Current Psychology, 35(2), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9416-4

Tams, S., Legoux, R., & Leger, P.-M. (2018). Smartphone withdrawal creates stress: A moderated mediation model of nomophobia, social threat, and phone withdrawal context. Computers in Human Behavior, 81, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.026

Teng, F., You, J., Poon, K.-T., Yang, Y., You, J., & Jiang, Y. (2017). Materialism predicts young Chinese women’s self-objectification and body surveillance. Sex Roles, 76, 448–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0671-5

Twenge, J. M., & Foster, J. D. (2010). Birth cohort increases in narcissistic personality traits among American college students, 1982–2009. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1(1), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550609355719

Uhls, Y. T., & Greenfield, P. M. (2011). The rise of fame: An historical content analysis. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 5(1), Article 1. https://cyberpsychology.eu/article/view/4243

Uhls, Y. T., & Greenfield, P. M. (2012). The value of fame: Preadolescent perceptions of popular media and their relationship to future aspirations. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 315–326. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026369

Uhls, Y. T., Zgourou, E., & Greenfield, P. (2014). 21st century media, fame, and other future aspirations: A national survey of 9–15 year olds. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 8(4), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2014-4-5

Williams, G. C., Hedberg, V. A., Cox, E. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Extrinsic life goals and health-risk behaviors in adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(8), 1756–1771. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02466.x

Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 590-597. https://doi.org/1.1037//0022-3514.61.4.590

Xie, W. (2014). Social network site use, mobile personal talk and social capital among teenagers. Computers in Human Behavior, 41, 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.042

Xu, Y., & Hamamura, T. (2014). Folk beliefs of cultural changes in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 1066. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01066

Zeng, R., & Greenfield, P. M. (2015). Cultural evolution over the last 40 years in China: Using the Google Ngram Viewer to study implications of social and political change for cultural values. International Journal of Psychology, 50(1), 47−55. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12125

Zhang, W., Chen, L., Yu, F., Wang, S., & Nurmi, J.-E. (2015). Hopes and fears for the future among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25(4), 622−629. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12166

Zheng, Y., & Huang, L. (2005). Overt and covert narcissism: A psychological exploration of narcissistic personality. Journal of Psychological Science, 28(5), 1259−1262. http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-XLKX200505063.htm

Authors’ Contribution

Yu-ting Hu: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. Yi-Duo Ye: conceptualization, data curation, writing—review & editing. Jian-Zhong Hong: conceptualization, validation, writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

July 14, 2021

Revisions received:

August 9, 2022

September 18, 2022

October 7, 2022

Accepted for publication:

October 24, 2022

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

In the past four decades, China has achieved great economic as well as technological development, within which the emergence of the internet has been especially noticeable. According to a report by the China Internet Network Information Center (2022), by the end of June 2022, the number of Chinese netizens amounted to 1,051 million, with an internet penetration rate of 74.4%. A total population of 181 million millennials aged 20–29 has become the dominant group of Chinese netizens (China Internet Network Information Center, 2022). Social networking sites have been one of the most popular internet applications accessed by the above-mentioned population group. Among various social networking sites in China, WeChat stands out, with almost 97.7% of Chinese netizens using it. Given the rapid development of the internet, it is crucial to know how social media influence Chinese millennials’ values in life (i.e., their future goals).

According to social change and human development theory, sociodemographic shifts promote changes in cultural values, which in turn modify the learning environment. Thereafter, the transformational learning environment alters individual development (Greenfield, 2009a, 2009b, 2013). Previous research indicates that the rapid development and popularization of communication technologies drives cultural values and learning environments in an individualistic direction (Uhls & Greenfield, 2011). Wealth, fame, and personal attractiveness are typical individualistic values (Kasser & Ryan, 1993, 1996), which are core components of extrinsic goals. However, excessively desiring extrinsic values and neglecting intrinsic values has a negative impact on millennials’ self-growth and social development (Hu et al., 2021; Teng et al., 2017). Thus, it is likely to be useful to focus on the impact of social network use on the values of millennials.

Previous research has primarily focused on the direct link between social media use and extrinsic goals (e.g., Uhls & Greenfield, 2012; Uhls et al., 2014). However, little is known about how social media use is related to intrinsic goals and the mediation process (i.e., how social media use is linked to future goals) and the moderation process (i.e., when social media use is linked to future goals) in a Chinese context. From a theoretical perspective, previous studies have only partly confirmed the hypothesis of social change and human development theory, namely, that sociodemographic shifts (i.e., increasing use of communication technology) promote changes in human development. Overall human development involves variables such as motivations and goals. Individuals with different personality traits may have different pathways of human development, so it is necessary to provide more empirical data at an individual level to support the hypothesis of social change and human development theory. Therefore, this study tested the mediating role of desire for fame and the moderating role of narcissism in the association between active social media use and desire for fame.

Active Social Media Usage and Future Goals

The future goals of millennials comprise core factors of the values that influence how they perceive and assess their environment, and which intentional efforts they choose to apply (Sheldon et al., 2004, 2010). According to goal-content theory, future goals can be generally classified as either intrinsic or extrinsic in terms of their content (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Intrinsic goals (e.g., self-acceptance, affiliation) involve behaviors that are dependent on satisfying inherently rewarding basic psychological needs, whereas extrinsic goals (e.g., financial success, popularity) involve behaviors that are dependent on external rewards or the reactions of others (Kasser & Ryan, 1993, 1996). Future goals can have significant effects on an individual’s well-being (Niemiec et al., 2009), depression (Pueschel et al., 2011), health-risk behaviors (Shamloo & Cox, 2010; Williams et al., 2000), and physical health (Kasser & Ryan, 1993).

Various studies have found that communication technologies lead cultural values to develop in an individualistic direction (Greenfield, 2009a; Uhls & Greenfield, 2011; Uhls et al., 2014). Wealth, fame, and personal attractiveness are typical individualistic goals (Kasser & Ryan, 1993, 1996), which are also core components of extrinsic goals. Social networking sites encourage individuals to self-disclose facts and information about themselves via status updates, photos, and picture posts, which termed as active usage. Active usage can not only provide satisfactory self-presentation but also fulfill a need to belong (Nadkarni & Hofmann, 2012). Social media provide active users with an accessible enactive learning (learning by doing) tool with which they can obtain media information that matches their own concepts and values. Chinese millennials have grown up with the internet, which has predominantly shaped their ideas and behaviors (Li et al., 2014; Peat et al., 2015). Social networking sites tend to be overly embellished, emphasizing materialistic objects, beautiful appearances, and other extrinsic values (Hu & Q.-Q. Liu, 2020), which are likely to promote personal extrinsic goals (Greenfield, 2013; Uhls & Greenfield, 2011). Thus, we posited the following hypothesis:

H1: Active social media usage is positively related to extrinsic goals.

Intrinsic goals aim toward self-acceptance, emotional intimacy, and community involvement (Kasser & Ryan, 1996). Additionally, active social media use can influence users’ traits and beliefs (Gentile et al., 2012; Halpern et al., 2016). Some studies have found that active social media use is beneficial for developing positive self-views (Gentile et al., 2012) and social self-efficacy (Li et al., 2014). Furthermore, social networking sites can help individuals to establish and maintain good interpersonal relationships with their friends, families, and peers (Lin & Lu, 2011; Xie, 2014). Thus, active social media use has an intrinsic utility for users. According to social change and human development theory, sociodemographic shifts promote changes in cultural values and human development. In this regard, recent development trends in social and cultural values in China have shown rising individualism and declining collectivism in many respects, which is basically consistent with worldwide trends in social and cultural changes in the past half century (Cai et al., 2018; Santos et al., 2017). Nevertheless, some studies have found that not all collectivist values show a declining trend, and that some collectivist values are still relevant. For example, Zeng and Greenfield (2015) found that traditional Chinese values, such as responsibility and obligation, had remained stable or become more widespread in recent decades. Xu and Hamamura (2014) reported that the importance of traditional values in relation to family, friends, affinity, and patriotism had not decreased. Chinese millennials who actively use social media might be more likely to maintain relationships rather than focus on gaining wealth and fame for themselves. Considering the social function and intrinsic utility of social media, as well as current trends in Chinese cultural values, active social media use might promote intrinsic goals in millennials. However, a prior study did not find an association between media use and intrinsic ideas (Uhls et al., 2014). Thus, this study aimed to clarify the relationship between active social media use and intrinsic goals. We posited the following hypothesis:

H2: Active social media usage is positively related to intrinsic goals.

Desire for Fame as a Mediator

Desire for fame is defined as a desire to look for public recognition on a large scale beyond one’s immediate social network of friends, community, and family (Greenwood et al., 2018; Uhls & Greenfield, 2012). Some studies have shown that media use is significantly correlated with desire for fame (Greenwood et al., 2013; Maltby, 2010). According to social change and human development theory, communication technology is a strong driving force promoting change in our society (Uhls & Greenfield, 2012). Some researchers have reported that the information presented in social media reinforces values of fame and material achievement among the younger generation (Gountas et al., 2012; Uhls & Greenfield, 2011, 2012). One study found that observational learning is a significant factor on social networking sites (Moreno & Whitehill, 2014). Through such sites, young people can learn about topics including “what is fame,” “what fame can bring about,” and “how to become famous.” Thus, they would be more likely to desire fame through their interaction with such sites. In addition to information browsing behavior, active social media use (e.g., status updates, posting photos and videos) may have more potent effects on desire for fame. Social networking sites can provide a platform with large audiences beyond the daily intercommunication scope. Users can easily update their statuses or post photos and videos to display themselves and their lives to gain attention and feedback, which might intensify the desire for fame. Indeed, more people now desire to achieve fame and believe they will be famous one day (Maltby, 2010; Uhls et al., 2014). In China, WeChat is the most popular social networking site. The senior vice president of Tencent Holdings reported that, every day, 1.09 billion people use the WeChat application, and 780 million enter WeChat circle. The continuous expansion of WeChat friend lists makes the WeChat’s social relationship chain larger and more stable, which also makes it difficult for other social networking sites to compete with WeChat (iiMedia Research, 2021). Individuals are inclined to present themselves in overly flattering ways on WeChat, which gives rise to social comparisons amongst users’ peers and friend circles (Hu & Q.-Q. Liu, 2020). Thus, it has been found that WeChat has a significant effect on millennials (Fu & Cook, 2020; Huang & Zhang, 2017). Therefore, it is plausible that active usage of WeChat (e.g., status update states, posting photos and videos) could be positively associated with millennials’ desire for fame.

Desire for fame has a close relation with future goals. Recently used future goal measures have overemphasized the content of future goals (Kasser & Ryan, 1993, 1996) while ignoring the motives behind them (Sheldon et al., 2004, 2010). Particular attention should be paid to both the what and why of goal pursuit (Michou et al., 2014). Future goals involve distal outcomes while the underlying motivations, such as desire for fame, provide proximal reasons. Many people regard fame as a route to achieve extrinsic goals such as wealth, attractive appearance, and status. Various studies have shown the association between desire for fame and extrinsic goals (Gountas et al., 2012; Maltby et al., 2008; Uhls et al., 2014).

Moreover, some research has indicated that desire for fame derives from the need to belong (Greenwood et al., 2013), and includes elementary prosocial behaviors (Greenwood et al., 2013; Maltby, 2010). The need to belong and altruistic motives are closely associated with intrinsic goals (McHoskey, 1999). Moreover, in China, collectivist values encourage individuals to make contributions to the group (e.g., family, organizations; Zeng & Greenfield, 2015). Chinese people might be considered as more likely to strive to achieve fame for group benefits. Therefore, to some extent, desire for fame might also be associated with intrinsic goals (e.g., affiliation, community feeling). Given that active social media use is positively associated with desire for fame, which in turn might be positively associated with future goals, desire for fame might mediate the connection between active social media use and future goals. Thus, we posited the following hypothesis:

H3: Desire for fame mediates the relationships between active social media use and both intrinsic and extrinsic goals.

Narcissism as a Moderator

Narcissism is a personality trait encompassing grandiosity, selfishness, need for admiration, authority, and entitlement (Raskin & Terry, 1988). In recent decades, the level of narcissism among the younger population has been rising continuously (Twenge & Foster, 2010). In China, Cai et al. (2012) found that young people from urban areas are becoming increasingly narcissistic. According to self-regulation theory, people with high-level narcissism are highly invested in promoting their self-perceived superiority (Cain et al., 2008). They tend to set goals to affirm their grandiose sense of self (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). Gaining fame and being admired by society can help meet the expectations of individuals with high levels of narcissism more effectively. Some research has also found that narcissism is positively associated with the desire for fame (Greenwood et al., 2013; Maltby, 2010; Southard & Zeigler-Hill, 2016) and extrinsic goals (Kasser & Ryan, 1996).

One type of moderating model has been used to focus on individuals with the same level of independent variables that influence dependent variables at different levels due to differing levels of moderating variables (Nostrand & Ojanen, 2022; Sosik et al., 2014). Another dynamic self-regulatory processing model of narcissism proposes that narcissists generally use self-regulatory strategies and actively construct their social set-ups and environments to verify their grandiose self-images and satisfy their self-evaluative needs (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). Compared with low-level narcissistic individuals, high-level narcissistic individuals who have the same level of active social media use tend to promote a highly positive self-image to advertise themselves to others to maintain their grandiose sense of self. Low-level narcissists who actively use social media are more likely to maintain relationships rather than highlight themselves, and they are less likely to desire fame. Therefore, we proposed that narcissism may intensify the positive association between active social media use and desire for fame. Therefore, we put forward the following hypothesis:

H4: Narcissism moderates the mediating effect of desire for fame between active social media use and future goals.

The Present Study

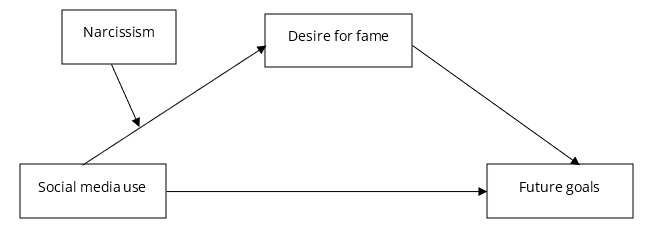

To summarize, the present study investigated the relationship between active social media use and future goals. First, based on previous studies, we expected to confirm the relationship between active social media use and future goals (intrinsic/extrinsic goals). Thereafter, we constructed a moderated mediation model to answer two questions: (a) whether desire for fame would mediate the connection between active social media use and future goals, and (b) whether narcissism would moderate the mediating effect of desire for fame. The moderated mediation model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

We selected two public universities by means of convenience sampling. Recruitment information was posted on social networking sites, including WeChat group, QQ group, as well as the campus forums of the two selected universities. A total of 422 undergraduate students were recruited for this study. The data were collected face-to-face using pen and paper in a laboratory. All questionnaires were written in Chinese. The data collection took place from November 2019 to December 2019. Well-trained psychology graduate students working as assistants verified the authenticity, independence, and comprehensiveness of all answers as well as ensuring the confidentiality of the information collected. Each participant was rewarded ¥15 for their participation. The average age of participants was 19.50 years (standard deviation [SD] = 1.32, range = 17–25) and the gender composition of the sample was 160 (37.9%) males and 262 (62.1%) females.

Measurements

Active Social Network Site Use

The participants were asked three questions concerning how frequently they performed a series of activities on WeChat. The participants were specifically asked how many times they had posted photos or videos on WeChat in the past month, how many times they had posted status updates, or shared others’ content on their own profile in the past month. To avoid recall bias, the participants needed to check past data before recording the information. Additionally, how frequently they gave “likes” or commented on others’ statuses in the past month was also recorded on a five-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (very often). Given that these three items were recorded by different methods, we counted the average of three standardized scores as the index of active social network site use. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was .65. The factor loadings of the three items were .70, .61, .36, respectively.

Desire for Fame

Desire for fame was divided into three dimensions including celebrity lifestyle (i.e., I want to see my picture on the cover of a magazine), psychological satisfaction (i.e., Fame meets my sense of superiority), and altruism (i.e., I want to be famous so I can spread positive energy via the media) in accordance with prior studies (Greenwood et al., 2013; Maltby, 2010; Maltby et al., 2008). We used a self-compiled scale containing 18 items to assess the above three dimensions (seven items for celebrity lifestyle, seven for psychological satisfaction, and four for altruism). The participants were asked how much they agreed with these items on a six-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). In our study, the scale showed good reliability and validity. The total Cronbach’s α for this scale was .95. Cronbach’s α was .96 for celebrity lifestyle, .94 for psychological satisfaction, and .92 for altruism. The data showed a good fit: χ2 = 471.83, df = 132, p < 0.001, comparative fit index (CFI) = .95, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = .95, standardized root mean residual (SRMR) = .04, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .08, and confidence interval (CI) for RMSEA = .07, .09. The factor loadings for the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) ranged from .76 to .91.

Narcissism

This study used a 20-item subscale of the Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire (NPQ; Fan et al., 2019; Zheng & Huang, 2005). The scale contains four dimensions: superiority including six items, self-admiration including three items, entitlement including five items, and authority including six items. The participants were asked to give a response on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Items such as I have the talent to influence others and I want to be a leader were included. In the present study, the Cronbach’s α for this scale was .91. The data showed a good fit as follows: χ2 = 533.10, df = 164, p < .001, CFI = .91, TLI = .90, SRMR = .06, RMSEA =.07, and CI for RMSEA = .07, .08. The factor loadings for the CFA ranged from .45 to .84.

Future Goals

Participants completed a 27-item revised version of the Aspirations Index in this study (Kasser & Ryan, 1996; Sheldon et al., 2010), which assesses three extrinsic aspirations (i.e., financial success, attractive appearance, and social recognition; 13 items) and three intrinsic aspirations (i.e., self-acceptance, community feeling, and affiliation; 14 items; Sheldon et al., 2004, 2010). Three items in original questionnaire (Sheldon et al., 2010) were deleted because of low factor loadings. The participants answered a question on how important it is to you that the goal be attained in the future?. They rated their responses on a scale from 1 (not significant at all) to 5 (extremely significant). In the current study, the Cronbach’s α for the extrinsic aspirations subscale was .88 and that for the intrinsic subscale was .94. The data showed a relatively good fit: χ2= 920.05, df = 317, p < .001, CFI = .91, TLI = .90, SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .07, and CI for RMSEA = .06, .07. The factor loadings for the CFA ranged from .55 to .83.

Covariates

In previous research, age has been associated with life aspirations (Olasupo & Idemudia, 2017; Uhls et al., 2014). Additionally, gender differences have been found in life aspirations (Greene & Debacker, 2004; Zhang et al., 2015). We thus regarded these variables as covariates. Gender was coded as 0 = female and 1 = male. Age was standardized prior to the statistical analyses.

Statistical Analysis

In our study, we first conducted a descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. Thereafter, we used SPSS 21 macro PROCESS (Hayes, 2013) software to test the mediation model and moderated mediation model. SPSS macro PROCESS software has been widely applied to test moderated mediation models (e.g., Q.-Q. Liu et al., 2018; Tams et al., 2018). We used bootstrapping to test indirect effects; the number of bootstrapping samples used was 5,000.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

The descriptive statistics and correlation matrix are presented in Table 1. Active WeChat use was positively correlated with three dimensions of desire for fame, narcissism, extrinsic goals, and intrinsic goals. Psychological satisfaction and altruism were each positively correlated with both extrinsic and intrinsic goals. Celebrity life was significantly correlated with extrinsic goals only, whereas narcissism was positively correlated with both extrinsic and intrinsic goals.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations Between Variables.

|

Variables |

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

1. Active WeChat use |

0.00 |

0.73 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Psychological satisfaction |

3.24 |

1.19 |

.27*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Altruism |

3.76 |

1.27 |

.23*** |

.67*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

4. Celebrity life |

2.54 |

1.14 |

.18*** |

.66*** |

.36*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

5. Narcissism |

2.73 |

0.61 |

.29*** |

.49*** |

.32*** |

.56*** |

— |

|

|

|

6. Intrinsic goals |

3.94 |

0.71 |

.12* |

.12* |

.31*** |

−.02 |

.13** |

— |

|

|

7. Extrinsic goals |

3.47 |

0.89 |

.22*** |

.41*** |

.34*** |

.36*** |

.56*** |

.43*** |

— |

|

Note. N = 422. *p < .05, **p < .01, *** p < .001. |

|||||||||

Testing the Proposed Model

Results generated by Hayes’ (2013) SPSS macro-PROCESS (model 4) are presented in Table 2. The mediator variable model tested the effects of active WeChat use on desire for fame (psychological satisfaction, altruism, celebrity life), while the dependent variable model tested the effects of active WeChat use and desire for fame (psychological satisfaction, altruism, celebrity life) on extrinsic goals. The direct path coefficient from active WeChat use to Chinese millennials’ extrinsic goals in the absence of the mediator was significant (β = .21, p < .001). After controlling for gender and age, active WeChat use positively predicted psychological satisfaction, altruism, and celebrity life. Extrinsic goals were positively predicted by psychological satisfaction, altruism, and celebrity life. Active WeChat use positively predicted extrinsic goals. The results showed that desire for fame partly mediated the link between active WeChat use and extrinsic aspirations. The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method showed that the mediating effect of psychological satisfaction was .05, 95% CI [.01, .10]. The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method showed that the mediating effect of altruism was .02, 95% CI [−.0,002, .06]. The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method showed that the mediating effect of celebrity life was .04, 95% CI [.01, .08]. These results indicated that psychological satisfaction and celebrity life mediated the relationship between active WeChat use and extrinsic goals.

Table 2. Mediation Analysis of Extrinsic Goals.

|

|

β |

SE |

t |

p |

LLCI |

ULCI |

|

Mediator variable model predicting psychological satisfaction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gender (female = 0, male = 1) |

.02 |

0.10 |

0.23 |

.817 |

−.17 |

.22 |

|

Age |

−.03 |

0.05 |

−0.69 |

.492 |

−.13 |

.06 |

|

Active WeChat use |

.28 |

0.05 |

5.47 |

< .001 |

.18 |

.38 |

|

Altruism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gender |

−.14 |

0.10 |

−1.38 |

.168 |

−.34 |

.06 |

|

Age |

.07 |

0.05 |

1.44 |

.151 |

−.02 |

.16 |

|

Active WeChat use |

.21 |

0.05 |

4.49 |

< .001 |

.12 |

.31 |

|

Celebrity life |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gender (female = 0, male = 1) |

.19 |

0.10 |

1.81 |

.070 |

−.02 |

.39 |

|

Age |

−.07 |

0.05 |

−1.42 |

.155 |

−.17 |

.03 |

|

Active WeChat use |

.20 |

0.06 |

3.49 |

< .001 |

.09 |

.32 |

|

Dependent variable model predicting extrinsic goals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gender (female = 0, male = 1) |

−.13 |

0.09 |

−1.37 |

.170 |

−.30 |

.05 |

|

Age |

.05 |

0.05 |

1.12 |

.265 |

−.04 |

.14 |

|

Active WeChat use |

.10 |

0.04 |

2.28 |

.023 |

.01 |

.19 |

|

Psychological satisfaction |

.19 |

0.08 |

2.30 |

.022 |

.03 |

.35 |

|

Altruism |

.12 |

0.07 |

1.75 |

.081 |

−.01 |

.25 |

|

Celebrity life |

.18 |

0.07 |

2.71 |

.007 |

.05 |

.31 |

|

Note. N = 422. Bootstrap sample size = 5,000. LL = lower limit, CI = confidence interval, UL = upper limit. |

||||||

Table 3 presents the mediation analysis in terms of intrinsic goals. The direct path coefficient from active WeChat use to Chinese millennials’ intrinsic goals in the absence of the mediator was significant (β = .10, p = .037). After controlling for gender and age, active WeChat use positively predicted psychological satisfaction, altruism, and celebrity life. Altruism positively predicted intrinsic goals whereas active WeChat use did not predict intrinsic goals. The results indicated that altruism fully mediated the link between active WeChat use and intrinsic goals. The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method showed that the mediating effect of altruism was .08, 95% CI [.04, .13]. This finding indicated that the relationship between active WeChat use and millennials’ intrinsic goals was mediated by altruism. However, psychological satisfaction and celebrity life did not predict intrinsic goals (p = .359, p = .096). The mediating effect of psychological satisfaction was −.02, 95% CI [−.07, .02]. The mediating effect of celebrity life was −.02, 95% CI [−.06, .001]. These results indicated that psychological satisfaction and celebrity life did not mediate the relationship between active WeChat use and intrinsic goals.

Macro-PROCESS (model 7) indicated that the interaction between active WeChat use and narcissism significantly predicted desire for fame. We tested three dimensions of desire for fame; the results showed that the interaction between narcissism and celebrity life was significant (β = .14, p < .001). In individuals with high narcissism (1 SD above the mean), the indirect effect of celebrity life had a significant positive effect (.03), while in individuals with low-level narcissism, the indirect effect of celebrity life had a significant negative effect (−.02). In individuals with mid-level narcissism (at the mean), the indirect effect of celebrity life was not significant. The interaction between narcissism and psychological satisfaction was not significant (β = .08, p = .070). The interaction between narcissism and altruism was also not significant (β = .003, p = .950). Thus, it would appear that the indirect effects of celebrity life in the link between active WeChat use and extrinsic goals were moderated by narcissism presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Mediation Analysis of Intrinsic Goals.

|

|

β |

SE |

t |

p |

LLCI |

ULCI |

|

Mediator variable model predicting psychological satisfaction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gender (female = 0, male = 1) |

.02 |

0.10 |

0.23 |

.817 |

−.17 |

.22 |

|

Age |

−.03 |

0.05 |

−0.69 |

.492 |

−.13 |

.06 |

|

Active WeChat use |

.28 |

0.05 |

5.47 |

< .001 |

.18 |

.38 |

|

Altruism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gender |

−.14 |

0.10 |

−1.38 |

.168 |

−.34 |

.06 |

|

Age |

.07 |

0.05 |

1.44 |

.151 |

−.02 |

.16 |

|

Active WeChat use |

.21 |

0.05 |

4.49 |

< .001 |

.12 |

.31 |

|

Celebrity life |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gender (female = 0, male = 1) |

.19 |

0.10 |

1.81 |

.070 |

−.02 |

.39 |

|

Age |

−.07 |

0.05 |

−1.42 |

.155 |

−.17 |

.03 |

|

Active WeChat use |

.20 |

0.06 |

3.49 |

< .001 |

.09 |

.31 |

|

Dependent variable model predicting intrinsic goals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gender (female = 0, male = 1) |

−.20 |

0.10 |

−2.01 |

.045 |

−.39 |

−.004 |

|

Age |

.03 |

0.05 |

0.51 |

.611 |

−.07 |

.12 |

|

Active WeChat use |

.07 |

0.05 |

1.35 |

.176 |

−.03 |

.17 |

|

Psychological satisfaction |

−.07 |

0.08 |

−0.92 |

.359 |

−.23 |

.08 |

|

Altruism |

.37 |

0.07 |

5.54 |

< .001 |

.24 |

.50 |

|

Celebrity life |

−.11 |

0.07 |

−1.67 |

.096 |

−.24 |

.02 |

|

Note. N = 422. Bootstrap sample size = 5,000. LL = lower limit, CI = confidence interval, UL = upper limit. |

||||||

Table 4. Conditional Indirect Effect Analysis of Extrinsic Goals on Moderating Values.

|

|

Narcissism |

β |

BootLLCI |

BootULCI |

|

Desire for fame |

M − SD |

.01 |

−.01 |

.04 |

|

M |

.02 |

.004 |

.06 |

|

|

M + SD |

.04 |

.01 |

.09 |

|

|

Psychological satisfaction |

M − SD |

.01 |

−.001 |

.05 |

|

M |

.01 |

−.001 |

.04 |

|

|

M + SD |

.01 |

−.001 |

.05 |

|

|

Celebrity life |

M − SD |

−.02 |

−.05 |

−.004 |

|

M |

.003 |

−.01 |

.02 |

|

|

M + SD |

.03 |

.01 |

.07 |

|

|

Note. N = 422. Bootstrap sample size = 5,000. BootLLCI = bootstrap lower limit. confidence interval, BootULCI = bootstrap upper limit confidence interval. |

||||

According to the results of the mediator variable model, only the altruism dimension mediated the relationship between active WeChat use and millennials’ intrinsic goals; therefore, we analyzed the altruism dimension as the mediator. The interaction between active WeChat use and narcissism did not significantly predict altruism (β = .003, p = .950). Thus, narcissism did not have a moderating effect in the relationship between active WeChat use and millennials’ intrinsic goals.

In general, desire for fame mediated the associations between active WeChat use and extrinsic goals, and between active WeChat use and intrinsic goals. However, there were different mediating mechanisms involved between active WeChat use and extrinsic goals, and between active WeChat use and intrinsic goals. Psychological satisfaction and celebrity life mediated the associations between active WeChat use and extrinsic goals. In contrast, only the relationship between active WeChat use and millennials’ intrinsic goals was mediated by altruism, whereas psychological satisfaction and celebrity life did not mediate this relationship. Furthermore, the indirect effect of desire for fame between active WeChat use and extrinsic goals was moderated by narcissism, with these effects being stronger for individuals with elevated levels of narcissism than for those with low levels of narcissism. However, the indirect effect of desire for fame between active WeChat use and intrinsic goals was not moderated by narcissism. Therefore, H1 and H2 were only partly supported.

Discussion

This study tested a moderated mediation model in which the indirect effect of active WeChat use on future goals through desire for fame was moderated by narcissism. The results partly confirmed our hypotheses and demonstrated the mediating effect of desire for fame between active WeChat use and future goals including extrinsic goals and intrinsic goals. The mediating effect of desire for fame between active WeChat use and extrinsic goals varied at different levels of narcissism.

Our study found a direct link between active social media use and extrinsic goals, which was consistent with previous research (Uhls & Greenfield, 2012; Uhls et al., 2014). Prior studies have found that, compared with people using social networking sites passively, people who engaged in more frequent activities were more eager to achieve extrinsic goals (Uhls & Greenfield, 2012; Uhls et al., 2014). Social change and human development theory suggests that the rapid development and popularization of communication technologies has driven cultural values and learning environments in an individualistic direction (Uhls & Greenfield, 2011). Wealth, fame, and personal attractiveness are typical individualistic values (Kasser & Ryan, 1993, 1996), which are core components of extrinsic goals. To some extent, Chinese millennials’ ideas and behaviors have been shaped by the internet because they have grown up with the internet (Li et al., 2014; Peat et al., 2015). Social media provides an accessible enactive learning (learning by doing) platform to obtain media information that matches their own values. Social media platforms often propagate images of beauty, wealth, and fame (Greenfield, 2013; Hu & Q.-Q. Liu, 2020; Uhls & Greenfield, 2011), which can rapidly promote extrinsic personal goals.

Furthermore, our research found that active social media use was associated with intrinsic goals. Previous studies have also found that active social media use is associated with developing positive self-views (Gentile et al., 2012) and social self-efficacy (Li et al., 2014). Additionally, social networking sites can help individuals to establish and maintain good interpersonal relationships with their friends, families, and peers (Lin & Lu, 2011; Xie, 2014). This may explain why active social media use was found to be linked to intrinsic goals.

In the mediated model, the desire for fame comprising two components partly mediated the link between active WeChat use and extrinsic goals. Moreover, one component of desire for fame, namely, altruism, fully mediated the link between active WeChat use and intrinsic goals. For the first stage of the mediation process (i.e., the relation between active WeChat use and desire for fame), the result accords with social change and human development theory (Greenfield, 2009b; Uhls et al., 2014). Today, social media is flooded with information about celebrities, fame, success, and wealth, which is likely to become gradually integrated into people’s values and concepts (Uhls & Greenfield, 2012; Uhls et al., 2014). Social media provides people with a new platform to observe celebrities and learn from them. They can imitate such celebrities by presenting themselves on social networking sites as being just like them. Moreover, active social media use generally brings about intensive attention and positive feedback (D. Liu & Brown, 2014), which may further act as a catalyst to increase the desire for fame.

The second stage of the mediation process assessed two paths: the positive association between desire for fame and extrinsic goals, and the positive association between desire for fame and intrinsic goals. To some extent, the results were consistent with prior studies in America and Europe (Gountas et al., 2012; Uhls et al., 2014) suggesting that desire for fame is positively associated with extrinsic goals. However, the relationship found in this study between desire for fame and intrinsic goals differed from previous research indicating that desire for fame was negatively or not significantly related to intrinsic goals (Gountas et al., 2012; Uhls et al., 2014). Some research has indicated that desire for fame might derive from the need to belong, which is an altruistic motive (Greenwood et al., 2013). Prosocial motives are closely associated with intrinsic goals (McHoskey, 1999). Additionally, in China, collectivist values encourage individuals to make contributions to the group (e.g., family, organizations; Zeng & Greenfield, 2015). Influenced by traditional values, Chinese people might believe that fame could bring their families a better quality of life; they might believe that they could help more people by being famous, which is associated with intrinsic goals (e.g., community feeling, affiliation). Chinese people might strive to achieve fame for group benefits. Therefore, to some extent, desire for fame might also be associated with intrinsic goals (e.g., affiliation, community feeling). Moreover, the psychological satisfaction dimension means fame can affirm an individual’s sense of superiority, satisfy their vanity, and help them overcome feelings of inferiority. The celebrity life dimension indicates that fame can bring about a luxurious life. These two components of desire for fame were not found to be associated with intrinsic goals, so they had no mediating effects. Moreover, compared with intrinsic goals, desire for fame had a closer relationship with extrinsic goals. Fame is more closely associated with wealth and luxurious living that results in a stylish lifestyle. Both the link between active WeChat use and extrinsic goals, and the link between active WeChat use and intrinsic goals, were partly mediated by one or more of the dimensions of desire for fame, although the specific mechanism differed in each case. In this regard, Active WeChat use could directly and indirectly affect extrinsic goals. However, active WeChat use was only linked to intrinsic goals through altruism, which is a component of desire for fame. Thus, active WeChat users were more likely to attach importance to intrinsic goals when social media aroused intrinsic motivation (i.e., prosociality). The association between desire for fame and intrinsic goals was weaker. However, it remains a key factor in the relationship between active social network usage and intrinsic goals.

Furthermore, the results showed that narcissism moderated the indirect path between active WeChat use and extrinsic goals through desire for fame. Specifically, a more potent indirect effect of desire for fame existed between active WeChat use and extrinsic goals among individuals who had high-level narcissism. The indirect effect did not exist for individuals with medium-level narcissism. The finding that there were individual differences in the association between active WeChat use and desire for fame was consistent with self-regulation theory and previous studies (Greenwood et al., 2013; Maltby, 2010; Southard & Zeigler-Hill, 2016). There are some specific reasons that may explain the moderating effect of narcissism. One dynamic self-regulatory processing model of narcissism suggests that narcissists tend to adopt certain behaviors to verify grandiose self-images and satisfy self-evaluative needs (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). On social media, users can easily obtain positive feedback, which may create a feeling of being sought after and allow narcissists to actively maintain grandiose self-images and satisfy the need to be admired. Compared with low-level narcissistic individuals, high-level narcissistic individuals who have the same level of active social media use tend to promote a highly positive self-image to advertise themselves to others to maintain their grandiose self-images and satisfy self-evaluative needs. Low-level narcissists who actively use social media are more likely to maintain relationships rather than highlight themselves and are less likely to desire fame. This can explain why the association between active WeChat use and desire for fame was moderated by narcissism.

Limitations and Implications

Several potential limitations of the current study should also be considered. First, this study used self-report measures. Therefore, we could not completely exclude social desirability bias, which might lead to inaccurate results. Future research may apply big data or diary methods to record actual daily behaviors. Second, since the study’s participants were recruited from universities, the results may be difficult to generalize to other population groups. To address this limitation, future research may explore the proposed model in various populations. Third, this study explored the association between active WeChat use and future goals. Although WeChat is the most popular social media in China, some new applications (e.g., Tik Tok and live broadcast) have also come into fashion. Future research needs to pay more attention to these new phenomena. Finally, this cross-sectional survey study could not comprehensively determine the causal pathways involved. We only sampled a month of usage data, which cannot fully represent large and long-term conditions. Future researchers may consider adopting longitudinal or experimental studies to explore causation.

In spite of the above limitations, this study is the first to explore the mediating role of desire for fame and the moderating role of narcissism in the relation between active social media use and future goals. It provides an explanation of what kind of social media use is associated with future goals, which fills a gap in previous research (Uhls et al., 2014). Furthermore, this study adds new evidence about the association between social media use and intrinsic goals. Previous studies have only partly confirmed the hypothesis of social change and human development theory, namely, that sociodemographic shifts (i.e., increasing use of communication technology) promote changes in human development. However, overall human development involves multiple variables including motivations and goals. This study clarified the mediating and moderating factors in the connection between network media and future goals, which supports social change and human development theory at the individual level in the Chinese context.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Humanities and Social Science Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China (22YJC630037); Open Research Fund of Key Laboratory of Adolescent Cyberpsychology and Behavior (Central China Normal University), Ministry of Education (CCNUCYPSYLAB2022B04); National Natural Science Foundation of China (71832005) and the Philosophy and Social Science Research Base of Jiangsu Colleges and Universities (2018ZDJD-A011).

Appendix

Desire for Fame Scale

How much do you agree with these items on a six-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree):

I want to be famous so that I can see my picture on the cover of a magazine.

If I am famous, I will be recognized in public.

I want to be famous so that I can do press interviews.

If I am famous, I will be asked for an autograph.

I want to be famous so that I can be talked about.

I want to be famous so that I can attend awards shows.

I want to be famous so I can become a spokesperson for my favorite products or brands.

Being famous would bring me a sense of superiority.

Being famous would bring a sense of meaning to my life.

I want to be famous because it would help me overcome issues l have about myself.

I want to be famous because it would make me happy with myself.

Becoming famous would help me feel better.

Being famous can satisfy my vanity.

Being famous can help me overcome inferiority.

I want to be famous so I can spread positive energy through media.

I want to be famous so I can help others in need.

I want to be famous so I can financially support my family.

If I am famous, I can be a role model for others.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2023 Yu-ting Hu, Yi-Duo Ye, Jian-Zhong Hong