A systematic literature review of factors that moderate bystanders’ actions in cyberbullying

Vol.12,No.4(2018)

Special Issue: Bystanders of Online Aggression

Cyberbullying is an incipient phenomenon which occurs by means of digital devices, in virtual environments, which often overlaps with traditional bullying. Research reveals the relevant role played by bystanders in stopping bullying and cyberbullying. The aim of this work is to identify those factors which encourage or hamper the mobilisation of young bystanders under 20 years of age in instances of cyberbullying, through a systematic literature review spanning 2005 to 2016 in the databases Web of Science Core Collection and SciELO Citation Index. A total of 19 articles were analysed. We identified two types of factors. Firstly, there are contextual factors, which refer to the relationships at play, the interactions and the environment, and are grouped into the following categories: friendship, social environment, bystander effect, incident severity, action of other bystanders, request for assistance, evaluation of the situation, knowledge of effective strategies, characteristics of virtual environments, and fear of retaliation. Secondly, there are personal factors, referring to individual traits, categorised into: empathy, moral disengagement, self-efficacy, behavioural determinants, previous experience of bullying and cyberbullying, and demographic and socio-economic data. Of particular influence seem to be the factors of friendship and social context, as well as empathy, moral disengagement and self-efficacy. To formulate practical recommendations to guide the development of educational programmes aimed at preventing cyberbullying using the bystander approach, further evidence is needed in relation to all factors, although certain general directions can be discerned even at this early stage. This is a new and exciting field of research which carries the hope of eradicating bullying in all its forms.

Cyberbullying; personal factors; contextual factors; bystanders; systematic literature review

Fernando Domínguez-Hernández

Faculty of Education, UNED (National University of Distance Education), Madrid, Spain

Fernando Domínguez-Hernández is a Ph.D. Student at the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED) in Madrid, Spain. His main lines of research are school coexistence and violence educational prevention, specifically the role of bystanders in instances of bullying and cyberbullying.

Lars Bonell

Department of Social Work and Social Education, Centro Universitario La Salle, Madrid, Spain

Lars Bonell García (Ph.D. University of Valladolid (UVa), 2016) is a lecturer at the University of La Salle in Madrid, Spain. His main lines of research are family-community-school partnerships for academic success and improved coexistence, and family-professionals partnerships in the field of intellectual disability to improve quality of life. His most recent research focuses on the analysis of barriers and facilitators for the participation in school of families belonging to vulnerable groups.

Alejandro Martínez-González

Department of Social Work and Social Education, Centro Universitario La Salle, Madrid, Spain

Alejandro Martínez-González, (Ph.D. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2006) is a full professor at the Univsersity of La Salle in Madrid, Spain (Department of Social Work and Social Education). His main lines of research are school coexistence, social and educational work with groups, gender violence prevention and the use of media in educational settings. His most recent research focuses on the overcoming of gender violence in Roma community, and on the improve of school coexistence and academic outcomes in primary and secondary education.

Allison, K. R., & Bussey, K. (2016). Cyber-bystanding in context: A review of the literature on witnesses’ responses to cyberbullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, 183-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.03.026

American Educational Research Association. (2013). Prevention of bullying in schools, colleges, and universities: Research report and recommendations. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 364-374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364

* Barlinska, J., Szuster, A., & Winiewski, M. (2013). Cyberbullying among adolescent bystanders: Role of the communication medium, form of violence, and empathy. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23, 37-51. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2137

* Barlinska, J., Szuster, A., & Winiewski, M. (2015). The Role of short- and long-term cognitive empathy activation in preventing cyberbystander reinforcing cyberbullying behavior. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18, 241-244. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0412

* Bastiaensens, S., Pabian, S., Vandebosch, H., Poels, K., Van Cleemput, K., DeSmet, A., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2016). From normative influence to social pressure: How relevant others affect whether bystanders join in cyberbullying. Social Development, 25, 193-211. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12134

* Bastiaensens, S., Vandebosch, H., Poels, K., Van Cleemput, K., DeSmet, A., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2014). Cyberbullying on social network sites. An experimental study into bystanders’ behavioural intentions to help the victim or reinforce the bully. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 259-271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.036

* Bastiaensens, S., Vandebosch, H., Poels, K., Van Cleemput, K., DeSmet, A., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2015). ‘Can I afford to help?’ How affordances of communication modalities guide bystanders’ helping intentions towards harassment on social network sites. Behaviour & Information Technology, 34, 425-435. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2014.983979

Bollmer, J. M., Milich, R., Harris, M. J., & Maras, M. A. (2005). A friend in need: The role of friendship quality as a protective factor in peer victimization and bullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 701-712. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504272897

Boulton, M. J., Trueman, M., Chau, C., Whitehand, C., & Amatya, K. (1999). Concurrent and longitudinal links between friendship and peer victimization: implications for befriending interventions. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 461-466. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0240

Del Rey, R., Elipe, P., & Ortega, R. (2012). Bullying and cyberbullying: overlapping and predictive value of the co-occurrence. Psicothema, 24, 608-613. Retrieved from https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4650378

* DeSmet, A., Bastiaensens, S., Van Cleemput, K., Poels, K., Vandebosch, H., Cardon, G., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2016). Deciding whether to look after them, to like it, or leave it: A multidimensional analysis of predictors of positive and negative bystander behavior in cyberbullying among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 398-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.051

* DeSmet, A., Bastiaensens, S., Van Cleemput, K., Poels, K., Vandebosch, H., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2012). Mobilizing bystanders of cyberbullying: An exploratory study into behavioural determinants of defending the victim. In B. K. Wiederhold & G. Riva (Eds.), Annual review of cybertherapy and telemedicine 2012: Advanced technologies in the behavioral, social and neurosciences (pp. 58-63). Amsterdam: IOS Press BV. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-121-2-58

* DeSmet, A., Veldeman, C., Poels, K., Bastiaensens, S., Van Cleemput, K., Vandebosch, H., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2014). Determinants of self-reported bystander behavior in cyberbullying incidents amongst adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17, 207-215. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0027

* Erreygers, S., Pabian, S., Vandebosch, H., & Baillien, E. (2016). Helping behavior among adolescent bystanders of cyberbullying: The role of impulsivity. Learning and Individual Differences, 48, 61-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.03.003

EU Kids Online. (2014). EU Kids Online: findings, methods, recommendations. London, UK: EU Kids Online, LSE. Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/60512/

Farrington, D. P., & Ttofi, M. M. (2009). School-based programs to reduce bullying and victimization. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 5. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2009.6

Frisén, A., Sofia, B., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Naruskov, K., Luik, P., … Zukauskiene, R. (2013). Measurement issues: A systematic review of cyberbullying instruments. In P. K. Smith & G. Steffgen (Eds.), Cyberbullying through the new media: Findings from an international network (pp. 37-62). New York: Psychology Press.

Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., & Altoe, G. (2008). Determinants of adolescents’ active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 93-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.002

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2013). Social influences on cyberbullying behaviors among middle and high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 711-722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9902-4

Hodges, E. V., Boivin, M., Vitaro, F., & Bukowski, W. M. (1999). The power of friendship: Protection against and escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology, 35, 94-101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.94

* Holfeld, B. (2014). Perceptions and attributions of bystanders to cyber bullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.012

* Huang, Y., & Chou, C. (2010). An analysis of multiple factors of cyberbullying among junior high school students in Taiwan. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 1581-1590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.005

* Jones, S. E., Manstead, A. S. R., & Livingstone, A. G. (2011). Ganging up or sticking together? Group processes and children’s responses to text-message bullying. British Journal of Psychology, 102, 71-96. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712610X502826

Latane, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander intervention in emergencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10, 215-221. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0026570

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., … Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

* Macháčková, H., Dedkova, L., & Mezulanikova, K. (2015). Brief report: The bystander effect in cyberbullying incidents. Journal of Adolescence, 43, 96-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.05.010

* Macháčková, H., Dedkova, L., Sevcikova, A., & Cerna, A. (2013). Bystanders’ support of cyberbullied schoolmates. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23, 25-36. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2135

Martín Casabona, N., & Tellado, I. (2012). Violencia de género y resolución comunitaria de conflictos en los centros educativos [Gender violence and community resolution of conflicts in the educational centres]. Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies, 1, 300-319. https://doi.org/10.4471/generos.2012.14

Menesini, E., Codecasa, E., Benelli, B., & Cowie, H. (2003). Enhancing children’s responsibility to take action against bullying: Evaluation of a befriending intervention in Italian middle schools. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.80012

O’Connell, P., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: Insights and challenges for intervention. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 437-452. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0238

* Olenik-Shemesh, D., Heiman, T., & Eden, S. (2015). Bystanders’ behavior in cyberbullying episodes: Active and passive patterns in the context of personal-socio-emotional factors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32, 23-48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515585531

Olweus, D. (1998). Conductas de acoso y amenaza entre escolares [Bullying at school. What we know and what we can do]. Madrid: Morata.

* Pabian, S., Vandebosch, H., Poels, K., Van Cleemput, K., & Bastiaensens, S. (2016). Exposure to cyberbullying as a bystander: An investigation of desensitization effects among early adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 480-487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.022

Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2006). Bullies move beyond the schoolyard: A preliminary look at cyberbullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 4, 148-169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204006286288

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41, 47-65.

Pöyhönen, V., Juvonen, J., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). What does it take to stand up for the victim of bullying? The interplay between personal and social factors. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56, 143-163. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.0.0046

Pozzoli, T., & Gini, G. (2010). Active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: The role of personal characteristics and perceived peer pressure. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 815-827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9399-9

* Price, D., Green, D., Spears, B., Scrimgeour, M., Barnes, A., Geer, R., & Johnson, B. (2014). A qualitative exploration of cyber-bystanders and moral engagement. Australian Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 24, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2013.18

Pyżalski, J. (2012). From cyberbullying to electronic aggression: Typology of the phenomenon. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 17, 305-317. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2012.704319

Quirk, R., & Campbell, M. (2015). On standby? A comparison of online and offline witnesses to bullying and their bystander behaviour. Educational Psychology, 35, 430-448. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2014.893556

Rosenberg, M., Schooler, C., Schoenbach, C., & Rosenberg, F. (1995). Global self-esteem and specific self-esteem: Different concepts, different outcomes. American Sociological Review, 60, 141-156. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096350

Royen, K. Van, Poels, K., Vandebosch, H., & Adam, P. (2017). “Thinking before posting?” Reducing cyber harassment on social networking sites through a reflective message. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 345-352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.040

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Bjorkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22

Salmivalli, C., & Voeten, M. (2004). Connections between attitudes, group norms, and behaviour in bullying situations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 246-258. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000488

Slonje, R., Smith, P. K., & Frisén, A. (2013). The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 26-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.024

Smith, P. K. (2016). School-based interventions to address bullying. Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri, 4(2), 142-164. https://doi.org/10.12697/eha.2016.4.2.06a

Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 376-385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

Smith, P. K., Salmivalli, C., & Cowie, H. (2012). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A commentary. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 8, 433-441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-012-9142-3

* Thomas, L., Falconer, S., Cross, D., Monks, H., & Brown, D. (2012). Cyberbullying and the Bystander (Report prepared for the Australian Human Rights Commission). Perth, Australia: Child Health Promotion Research Centre, Edith Cowan University. Retrieved from: https://bullying.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/bullying/bystanders/bystanders_results_insights_report.pdf

Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2012). Bullying prevention programs: The importance of peer intervention, disciplinary methods and age variations. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 8, 443-462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-012-9161-0

* Van Cleemput, K., Vandebosch, H., & Pabian, S. (2014). Personal characteristics and contextual factors that determine “Helping,” “Joining In,” and “Doing Nothing” when witnessing cyberbullying. Aggressive Behavior, 40, 383-396. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21534

Wolak, J., Mitchell, K. J., & Finkelhor, D. (2007). Does online harassment constitute bullying? An exploration of online harassment by known peers and online-only contacts. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, S51-S58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.019

Editorial Record:

First submission received:

April 30, 2018

Revisions received:

August 10, 2018

November 20, 2018

Accepted for publication:

November 19, 2018

The article is part of the Special Issue "Bystanders of Online Aggression" guest edited:

Hana Machackova (Masaryk University, Brno, Czechia), Jan Pfetsch (Technische Universität, Berlin, Germany), and Georges Steffgen (University of Luxembourg, Luxembourg)

Introduction

In today’s world, we witness new forms of aggression committed by and against young people, by means of digital devices. According to Royen, Poels, Vandebosch, and Adam (2017) ‘cyber harassment’ can be understood as ‘rude, threatening or offensive content directed at others by friends or strangers and performed via electronic means’ (p. 345). Meanwhile, bullying has been conceptualised as taking place among peers in a school context, and for this reason, only certain forms of ‘online harassment’ can be considered cyberbullying (Wolak, Mitchell, & Finkelhor, 2007). Although there are numerous forms of electronic aggression (Pyżalski, 2012), this paper is limited to cyberbullying (Slonje, Smith, & Frisén, 2013).

According to the definitions most widely accepted in academia, cyberbullying refers to those aggressive and intentional actions which are repeatedly carried out electronically or by means of texts by an individual or group towards victims who cannot easily defend themselves (Smith et al., 2008), or the harm caused by such actions (Patchin & Hinduja, 2006). Both definitions are based on the three elements of traditional bullying, as defined by Olweus (1998): intentional harm-doing, an imbalance of power and repetition over time. Cyberbullying occurs in contexts, and using tools, which mean that specific conditions must be taken into account. For instance, the constancy of harassment, 24 hours a day; the extremely broad potential audience that may be reached by a single act; or various aspects pertaining to anonymity and impersonation (Frisén et al., 2013). The study by EU Kids Online (2014) revealed that cyberbullying affects 12% of children between 11 and 16. Cyberbullying, in the same way as traditional bullying, has been shown to have serious psychosocial consequences, causing misery, fear, isolation, depression, anxiety, stress or even attempted suicide (Hinduja & Patchin, 2013). In view of all of the above, cyberbullying is a phenomenon that demands intervention and evidence-based prevention as a matter of priority.

Despite the fact that there have been certain controversies about the effectiveness of ‘work with peers’ in the prevention of traditional bullying (Farrington & Ttofi, 2009; Smith, 2016; Smith, Salmivalli, & Cowie, 2012; Ttofi & Farrington, 2012), we have evidence of the importance of bystander intervention in the prevention of bullying (American Educational Research Association, 2013; Polanin, Espelage, & Pigott, 2012; Pöyhönen, Juvonen, & Salmivalli, 2010), and increasingly that of cyberbullying (Thomas, Falconer, Cross, Monks, & Brown, 2012). The concept of a bystander refers to participants’ roles in the bullying, where they are neither victim nor perpetrator (such as those who reinforce or support the bully, those who defend the victim and those who remain on the sidelines as onlookers) (Salmivalli, Lagerspetz, Bjorkqvist, Österman, & Kaukiainen, 1996). Given the overlap between bullying and cyberbullying (Del Rey, Elipe, & Ortega, 2012; Quirk & Campbell, 2015), which results from the fact that the online and offline environments in which young people interact are a sort of continuum, the term ‘hybrid bystander’ has been coined (Price et al., 2014). Bystander intervention focuses on mobilising peers to defend the victim; typically, these peers would be the victim’s fellow students or friends, but could also be other adults in their social circles. Hence, the position of the educational community as a whole is absolutely crucial in putting an end to bullying and violence (Martín Casabona & Tellado, 2012).

The primary goal of this article is to identify factors that act as barriers or facilitators in the mobilisation of bystanders to intervene on behalf of the cyberbullying victim – that is, we are interested in what helps or hinders bystanders in becoming ‘upstanders’ in support of the victim. As noted by DeSmet et al. (2014), the factors influencing bystanders’ behaviour in offline and online contexts are quite similar. There may be various reasons for this. Firstly, the two phenomena are similar; in fact, the concept of cyberbullying is based on the definition of bullying (Smith et al., 2008). Moreover, in many cases, given the overlap between the two phenomena, the victimisation and the experience of it in both online and offline environments could be viewed as a continuum. Hence, secondly, those involved in the bullying and those who witness it will likely be the same players, and their motives will be the same whether they are interacting online or offline. Thirdly, the study of the factors prompting online bystanders to take action is a relatively young area of research, where, hitherto, study has focused on the same influence factors that are already known in relation to traditional bullying. As yet, very little research has been done which analyses factors relating to the specific environment of the web, such as the type of communication, the technical possibilities and limitations, new types of relationships and their interactions, among other factors.

Research distinguishes between contextual/environmental and personal/individual factors. Although more multidimensional studies are needed, some believe personal factors could carry more weight in cyberbullying (DeSmet et al., 2016). It should be assumed that contextual factors also have an important influence in online contexts given that such bullying takes hybrid (online/offline) forms.

The goal of this systematic literature review is to ‘collate all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a specific research question’ according to the Cochrane Collaboration (Liberati et al., 2009, p. 2). It is demonstrably relevant in the absence of similar reviews, beyond that of Allison and Bussey (2016), which includes some factors and focuses on the two most widely used theoretical frameworks influencing bystanders’ behaviour (bystander effect and socio-cognitive theory).

Methods

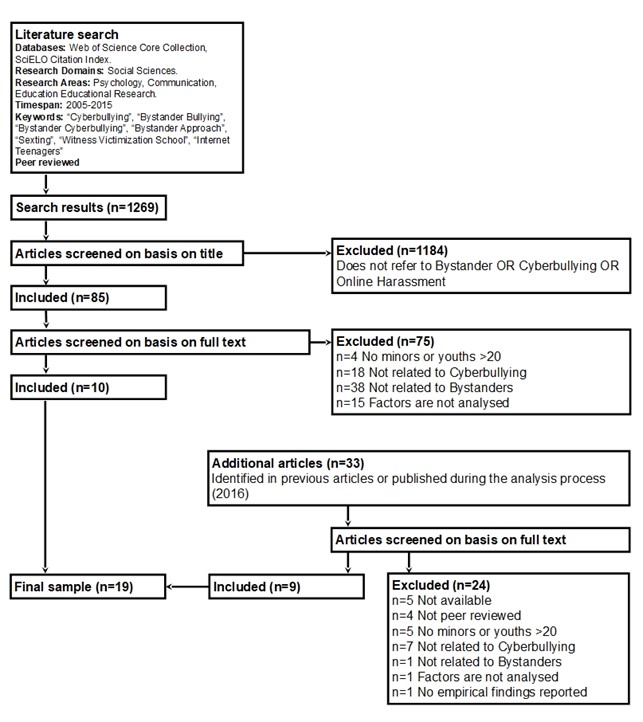

The systematic review was carried out by following the steps outlined below, in Figure 1:

Figure 1. Flowchart of selection process of articles for the systematic review.

Firstly, selection criteria were established to include research:

- a) published in peer-reviewed journals;

b) in which empirical findings (quantitative and/or qualitative data) were reported;

c) focusing on cyberbullying;

d) in which the subjects are under the age of 20;

e) addressing the role of bystanders;

f) analysing the factors which influence bystander behaviour;

g) published between 2005 and 2015.

Next, a search was run in the Web of Science Core Collection and SciELO Citation Index in the Research Domain ‘Social Sciences’ and the Research Areas of ‘Psychology’, ‘Communication’ and ‘Education Educational Research’, between 2005 and 2015. The keywords ‘Cyberbullying’, ‘Bystander Bullying’, ‘Bystander Cyberbullying’, ‘Bystander Approach’, ‘Sexting’, ‘Witness Victimization School’ and ‘Internet Teenagers’ were used. The search yielded a total of 1269 citations, which were screened by title, using inclusion criteria that referenced ‘Bystanders’, ‘Cyberbullying’ or ‘Online Harassment’. On the basis of this initial strategy, 1184 articles were excluded and 85 were included. Those 85 articles were screened on the basis of their full text by two researchers. The final systematic review included 10 articles, excluding 75 which did not match the inclusion criteria.

Finally, 33 new articles were added to the potential corpus, drawn from:

- a) research referenced in the previously selected 10 articles;

b) research published over the course of the review process (2016).

The two researchers screened the 33 articles on the basis of the full text; 25 did not match the inclusion criteria. One (Thomas et al., 2012) matched all the criteria, but being a research report, it had not been peer reviewed. Nonetheless, we ultimately chose to include this article because of its relevant findings. Thus, 24 were excluded and the remaining 9 were added to the previous 10, giving us a total of 19 documents to include in the review. These are detailed in Table 1, below.

Although studies based on quantitative methods clearly predominate, 4 articles present the results of qualitative studies that use interview and discussion group techniques (DeSmet et al., 2012, 2014; Price et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2012), and one is part of a broader, mixed-method study (Price et al., 2014). The ages in the samples vary widely between 8 and 20, with very different margins in different studies, including 8-12, 10-20 and 12-18, among others.

The analysis and subsequent data mining were based on a detailed review of the full text. The analysis was performed as follows:

- a) identifying the factors for analysis;

b) differentiating personal factors from contextual ones;

c) dividing the large number of factors into categories, owing to the different expressions and nuances found between various studies – especially those on contextual factors (Table 2). By selecting these categories, our intention was not to construct a conceptual model, but rather to create thematic groupings which would make subsequent analysis easier.

Table 1. Articles Included in the Systematic Review.

Authors (year) |

Age range |

Method |

Personal factors a |

Contextual factors a |

|

Barlinska, Szuster, & Winiewski (2013) |

11-18 |

Quantitative |

Victimisation and perpetration cyberbullying experience Empathy Gender |

Characteristics of online interaction: computer-mediated communication Forms of cyberbullying: Private vs. Public |

|

Barlinska, Szuster, & Winiewski (2015) |

12-17 |

Quantitative |

Cognitive empathy Age Gender |

|

|

Bastiaensens et al. (2014) |

M = 13 SD = 0.58 |

Quantitative |

Gender |

Incident severity Bystander Identity Bystander behaviour |

|

Bastiaensens et al. (2015) |

M = 13 SD = 0.58 |

Quantitative |

|

Mediacy: Via communication technology or face-to-face Privacy: Private or public communication Incident severity Bystander identity Bystander behaviour |

|

Bastiaensens et al. (2016) |

M = 15.42 SD = 1.69 |

Quantitative |

Age Gender |

Injunctive norms of friends, class group members, teachers and parents Descriptive norms of friends, class group members, teachers and parents Social pressure |

|

DeSmet et al. (2012) |

12-16 |

Qualitative |

Behavioural determinants: Attitudes, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, subjective norm Moral disengagement |

Behaviour and behavioural intention: Victim identity, bully identity, circumstances Behavioural determinants: Knowledge, cues to action Incident severity |

|

DeSmet et al. (2014) |

12-16 |

Qualitative |

Behavioural determinants: Attitudes, self-efficacy Moral disengagement |

Behaviour and behavioural intention: Victim identity, bully identity, circumstances Behavioural determinants: Knowledge, facilitators (incident severity) Norms |

|

DeSmet et al. (2016) |

M = 13.61 SD = 1.03 |

Quantitative |

Age Gender Type of education Living situation Family affluence Country of birth Traditional bullying involvement Cyberbullying involvement Moral disengagement Attitudes Self-efficacy |

Victim is a good friend Bully is a good friend Norms Skills and facilitators |

|

Erreygers, Pabian, Vandebosch, & Baillien (2016) |

9-16 |

Quantitative |

Impulsivity Empathy Age Gender |

|

|

Holfeld (2014) |

10-14 |

Quantitative |

|

Victim behaviour: Bystander’s perception of control, attributions of responsibility and blame |

|

Huang & Chou (2010) |

7th, 8th, 9th grade |

Quantitative + open-ended questions |

|

Friendship Responsibility Fear of getting in trouble Sense of uselessness in looking to adults for assistance Collectivism vs. individualism |

|

Jones, Manstead, & Livingstone (2011) |

10-11 |

Quantitative |

|

Group membership Identification with the group Group norms Group-based emotions: Pride, shame, anger, guilt Responsibility or legitimacy |

|

Macháčková, Dedkova, & Mezulanikova (2015) |

11-19 |

Quantitative |

Empathic concern Social self-efficacy Immediate empathic response Age Gender |

Victim identity Bystander Effect: Number of bystanders |

|

Macháčková, Dedkova, Sevcikova, & Cerna (2013) |

12-18 |

Quantitative |

Self-esteem Age Gender Prosocial behaviour |

Problematic relationships with peers Victim identity Bully identity Fear of intervening Upset feelings Request for help |

|

Olenik-Shemesh, Heiman, & Eden (2015) |

9-18 |

Quantitative |

Self-efficacy (social and emotional) Age Gender Loneliness (social and emotional) |

Social support of friends, family and significant others Internet literacy: Time and amount of Internet use Bystander Effect |

|

Pabian, Vandebosch, Poels, Van Cleemput, & Bastiaensens (2016) |

10-13 |

Quantitative |

Empathy Attitude Age Gender |

|

|

Price et al. (2014) |

8-12 |

Qualitative (part of a larger mixed method study) |

Moral Responsibility Empathy and Emotional Engagement |

Social Conventions / Friendships Power relations |

|

Thomas et al. (2012) |

13-17 |

Qualitative |

Facilitators: Self confidence |

Barriers: Fear, peer rejection, lack of knowledge of the history, uncertainty to get help Facilitators: Friendship, peer group support, knowing what to do and from whom to get help also, knowing how hurt the victim is, hope of reciprocated helping action, severity of situation |

|

Van Cleemput, Vandebosch, & Pabian (2014) |

9-16 |

Quantitative + open answers |

Empathy Previous experience in cyberbullying: Victim or perpetrator Self-efficacy Social anxiety Age Gender |

Difficult to interpret situation It was not necessary to get involved Out of fear Because of relationship with perpetrator Because of relationship with victim Timing Victim’s behavior Lack of social skills

|

|

Note: a Factors are showed as they exactly appear in the original text. |

||||

Table 2. Categories in Which Contextual and Personal Factors Were Included.

Type |

Categories |

Factors |

|

Personal |

Empathy |

Empathy Cognitive empathy Empathic concern Immediate empathic response Empathy and Emotional Engagement |

|

Moral disengagement |

Moral disengagement Moral Responsibility |

|

|

Behavioural determinants |

Attitudes Self-efficacy (social and emotional) Outcome expectations Impulsivity Social anxiety Self confidence Self-esteem Loneliness (social and emotional) |

|

|

Previous experience in bullying and cyberbullying |

Victimisation and perpetration cyberbullying experience Traditional bullying involvement Cyberbullying involvement Previous experience in cyberbullying: victim or perpetrator |

|

|

Demographic and Socio-economic data |

Age Country of birth Family affluence Gender Living situation Type of education |

|

|

Social environment |

Collectivism vs. individualism Descriptive norms of friends, class group members, teachers and parents Group-based emotions: pride, shame, anger, guilt Group norms Hope of reciprocated helping action Injunctive norms of friends, class group members, teachers and parents Norms Peer group support Power relations Responsibility or legitimacy Social pressure Social support of friends, family and significant others Sense of uselessness in looking to adults for assistance |

|

|

Contextual |

Friendship |

Friendship Bully identity Bully is a good friend Bystander Identity Group membership Identification with the group Behaviour and behavioural intention: victim identity, bully identity Problematic relationships with peers Because of relationship with perpetrator Because of relationship with victim Peer rejection Social Conventions / Friendships Victim identity Victim is a good friend |

|

Contextual |

Bystander Effect |

Bystander Effect: Number of bystanders |

|

Incident severity |

Incident severity Severity of situation Upset feelings |

|

|

Action of other bystanders |

Bystander behaviour |

|

|

Request for assistance |

Bystander’s perception of control, attributions of responsibility and blame. Request for help Victim behaviour |

|

|

Evaluation of the situation |

Behaviour and behavioural intention: circumstances Behavioural determinants: cues to action Difficult to interpret situation It was not necessary to get involved Lack of knowledge of the history, Timing |

|

|

Knowledge of effective strategies to address cyberbullying |

Behavioural determinants: Knowledge Knowing what to do and from whom to get help also, knowing how hurt the victim is Lack of social skills Skills and facilitators Uncertainty to get help |

|

|

Characteristics of virtual environments |

Characteristics of online interaction: computer-mediated communication Forms of cyberbullying: Private vs. Public Mediacy: Via communication technology or face-to-face Privacy: Private or public communication Internet literacy: Time and amount of Internet use |

|

|

Fear of retaliation |

Fear of getting in trouble Fear of intervening Out of fear |

Results

The factors unearthed were analysed, and the results are presented below. The discussion is divided into two broad sections distinguishing between contextual and personal factors. These, in turn, are grouped into the selected categories for the sake of ease.

Contextual Factors

Friendship. In cyberbullying incidents, friendship is a key contextual factor in bystander behaviour, often determining what type of action they ultimately take. According to 9 out of 19 articles of the final sample (Bastiaensens et al., 2014, 2015; DeSmet et al., 2012, 2014, 2016; Huang & Chou, 2010; Jones et al., 2011; Macháčková et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2012).

On one side, a good relationship between the bystander and offender can be a barrier that favours passive behaviour, or inhibits the bystander from helping the victim (Jones et al., 2011; Macháčková et al., 2013). For Jones et al. (2011), and Huang and Chou (2010), the fact of not knowing the victim, or having only a low degree of identification with them (meaning the relationship between bystander and victim is non-existent or insignificant), makes it less likely for bystanders to intervene on behalf of the victim.

As for positive ties between bystanders and victims, the existing body of research indicates two relational elements which do not necessarily coincide. However, they are usually associated with school contexts and may be considered important components of a good relationship between the two players: friendship and membership of a group. Both the bond of friendship between bystanders and victims and in-group relationships encourage bystanders to act in support of the victim (DeSmet et al., 2012, 2014; Jones et al., 2011; Price et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2012). For instance, in the qualitative research of Price et al. (2014) the young people consider mutual help is part of the universal social convention of friendship. One should be able to trust and not expect to be betrayed by their best friends.

As observed, friendship is an essential facilitator in mobilising bystanders which, according to DeSmet et al. (2014), can even overcome the conventional fear of becoming the next victim. As explained by DeSmet et al. (2012), this could be due to the moral implications of friendship, or to the risk of being excluded from the group or losing friends if they do not stand up for them. At the same time, paradoxically, they hold that young people expect their friends to comfort and help them indirectly if they are victims of online aggression rather than confronting the offender, because such direct confrontation can be difficult and risky (DeSmet et al., 2012). This can lead bystanders to take apparently conflicting actions; they at once reinforce the perpetrator and help the victim in private, establishing a continuum between the various roles, rather than the independent categories found in traditional bullying (DeSmet et al., 2014).

Despite the results of the different studies presented here, other research (without contradicting said results) attaches little influence to the relationship between bystander and victim. Macháčková et al. (2013) consider that a positive relationship with the victim encourages assistance, but only if other contextual factors are not at play.

In the view of Price et al. (2014), true friendship in itself carries complex meaning which includes social conventions, characteristics and moral obligations that, in turn, interact with group membership, norms, power factors and the hierarchical nature of social groups. Finally, Olenik-Shemesh et al. (2015) find that those who feel less perceived loneliness are most likely to offer help to victims.

Social environment. Under the heading of ‘social environment’ come results related to group norms, the attitudes and behaviours to which group members are expected to adhere (Jones et al., 2011); social norms, the expectations of peers, family or teachers (DeSmet et al., 2014); injunctive and descriptive norms, what you think others expect you to do and what you perceive others do (DeSmet et al., 2016); social support, the perception of being cared for and included by family, friends and other people in the surrounding circle (Olenik-Shemesh et al., 2015); social pressure, the process that usually encourages peers to act or think in a certain way (Bastiaensens et al., 2016). When studying bystander behaviour in relation to cyberbullying, both the online and offline social environments need to be taken into consideration (Bastiaensens et al., 2016).

On the negative side, we find that, in a given social environment or reference group, where there is a positive view of bullying behaviours, bystanders are more likely to tend to reinforce or join in with the aggressor. According to Bastiaensens et al. (2016), the perception that friends or family approve of cyberbullying is positively related to social pressure to join in and consequently take part in the action of bullying. In addition, for Jones et al. (2011), belonging to groups that support harassment leads to feelings of pride in its members who associate with the perpetrator. DeSmet et al. (2014) proposed that another barrier to the mobilisation of observers is the youths’ feeling that their environment offers them little incentive to act positively. In such a context, they do not receive much parental support to act, and end up accepting the fact that their peers do not defend them. Especially when rejection of the bystanders’ actions comes from their peers, as stated in Thomas et al. (2012), this barrier becomes more pronounced. For DeSmet et al. (2014) expectations partly account for bystanders’ behaviour. For example, bystanders tend to comply with certain subjective norms or expectations which others have about their behaviour. For instance, teachers expect students to report cases of bullying to them; peers expect to be comforted rather than defended if they are attacked; or there is a belief (in certain families, for instance) that one should not meddle in other people’s affairs, and that the they should fix their own problems themselves.

Huang & Chou (2010) attribute passive responses in bystanders to the collectivism which is so typical of eastern culture, where the good of the group is placed above personal wellbeing. Young people argue that bullying incidents are not their responsibility, but are private matters between others, in which they should not intervene. Furthermore, they report feeling there would be no point in reporting it to adults.

However, context can also have an impact on positive actions taken by bystanders and on reducing aggression. One key element is the appraisal and social support that bystanders’ actions actually receive. If support and recognition is expected, particularly from peer groups but also from adults, perceived self-efficacy or confidence is greater when it comes to confronting the perpetrator, encouraging victim assistance (DeSmet et al., 2014; Olenik-Shemesh et al., 2015; Price et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2012). In particular, according to Thomas et al. (2012), young people are motivated to help when they receive an appropriate response from the adults and the approval of their peers, as well as the expectation of reciprocal behaviour if they are bullied in the future. As stated by Olenik-Shemesh et al. (2015), the value and meaning which significant others give to bystanders' behaviour in cyberbullying influences their subsequent involvement.

Bystander effect. The bystander effect proposed by Latané and Darley (1968) suggests that the greater the number of passive individuals who witness an emergency situation, the less likely it is that any one of them will help the victim. This can be partly be explained by the mechanisms of diffusion of responsibility. In addition to being a social-psychological phenomenon, the bystander effect is also one of the most widely used theoretical frameworks in the study of bystander behaviour, along with social cognitive theory (Allison & Bussey, 2016).

Despite the difficulties in replicating the bystander effect in online contexts (Allison & Bussey, 2016) – in view of factors such as asynchronicity, the difficulty in evaluating the situation and the large number of participants in certain online communities – there have been a few studies which corroborate the existence of the bystander effect in cyberbullying among young people (Macháčková et al., 2015; Olenik-Shemesh et al., 2015), though these studies have identified that the relation between the number of bystanders and the offering of help is not a linear one (Macháčková et al., 2015). The same authors dispute the relevance of the bystander effect as, when we take account of other personal and contextual factors, the difference attributable to the bystander effect is minimal. They hold that the important thing is the subjective perception of the number of witnesses present.

Incident severity. When observers see situations as being very serious, they are positively motivated to assist the victim (Bastiaensens et al., 2014; DeSmet et al., 2012, 2014).

In addition the degree of distress caused by the bullying (which is a factor associated with incident severity) is found to be the most effective predictor out of all the factors analysed in the model of Macháčková et al. (2013).

Action of other bystanders. According to Bastiaensens et al. (2014), bystanders’ actions alone (without taking other variables into account) have not been demonstrated to affect how other people behave. However, when we consider friendship between bystanders and the actions they take, they have a stronger intention of doing what others do when their bystander friends support the bully. On the other hand, they are inhibited to do so when their bystander friends defend the victim. At the same time, bystanders generally prefer to help the victims in private regardless of other bystanders’ actions (Bastiaensens et al., 2015).

Request for assistance. In virtual environments, the responses of all the different players (if not explicitly expressed), and any harm caused, remain invisible, which lessens any emotional responses created in the bystanders. Macháčková et al. (2013) state that it can help to overcome these barriers if there is a direct request for help. According to Holfeld (2014), active responses (such as asking for help) and reactive ones (such as confronting the offender) mean that an incident is more likely to be viewed as a serious situation from which the victim is trying to escape, which could help mobilise bystanders to offer support. On the other hand, passive responses, such as ignoring the bully, could discourage bystanders from intervening.

Evaluation of the situation. Van Cleemput et al. (2014) point out that the lack of knowledge of the situation may hinder bystanders from taking action. For instance, they may not know whether the situation is already over, whether it has been resolved or whether other people are already intervening. DeSmet et al. (2012, 2014) found that ignorance of the psychological consequences of cyberbullying is also a barrier. Meanwhile, Thomas et al. (2012) found knowledge of the damage caused to the victims to be a facilitator.

Moreover, according to DeSmet et al. (2012, 2014), when bystanders analyse the bullying, they tend not to take action if they feel the circumstances are unclear or blame the victim and the victim is not a friend. If, on the other hand, the circumstances are perceived as unfair, they are more likely to take action, unless the victim is considered a loner.

Knowledge of effective strategies to address cyberbullying. DeSmet et al. (2012, 2014, 2016) and Thomas et al. (2012) state that knowing effective and assertive strategies, as well as intervention support resources, is essential in motivating bystanders to take action, especially if asking adults for help entails a response that remedies the problem. Van Cleemput et al. (2014) recognise that lack of knowledge is a barrier, and for DeSmet et al. (2016), having the specific skill set to be able to deal with the bullying encourages positive actions on the part of bystanders.

Characteristics of virtual environments. According to Barlinska et al. (2013), disinhibition in online environments and the possibility, pointed out by Bastiaensens et al. (2014), of interacting with people outside the social circle are associated with bystanders’ negative behaviour or the ease with which aggressors can bully. On the other hand, the public nature of communication via open channels reduces bystanders’ negative behaviour (Barlinska et al., 2013).

Fear of retaliation. Thomas et al. (2012) and Van Cleemput et al. (2014) found that the fear of retaliation could be a barrier to bystanders taking positive actions. However, we have already seen that friendship with the victim can help bystanders to overcome this fear. Nevertheless, Macháčková et al. (2013) found that fear had no effect on supportive behaviour.

Personal Factors

Empathy. Empathy is ‘an affective response more appropriate to someone else’s situation than to one’s own’ (Hoffman, as cited in Barlinska et al., 2013), or the ability to recognise, understand and share the emotions of others (Singer & de Vignemont, as cited in Barlinska et al., 2013). Thus, there is a type of empathy – cognitive empathy – which involves putting oneself in another’s shoes, and another – affective – type of empathy which allows one to experience another person’s emotions. In virtual environments, this distinction is particularly relevant, as the activation of cognitive empathy appears to be key in the absence of certain emotional aspects which are present in face-to-face communication (Barlinska et al., 2015).

Research such as that of Barlinska et al. (2013, 2015) emphasise the importance of cognitive and affective empathy in reducing negative behaviours carried out by bystanders who reinforce an aggressor or bully. However, it should be noted that affective empathy is only activated momentarily, and does not remain active in the medium or long term (Barlinska et al., 2015). At the same time, Erreygers et al. (2016), Macháčková et al. (2015) and Van Cleemput et al. (2014) link high empathy levels with victim-support behaviours. In general, Price et al. (2014) find empathy in young bystanders to be a facilitator for positive behaviour. Meanwhile, Van Cleemput et al. (2014) associate low levels of affective empathy with bystander actions such as joining in the bullying, or doing nothing at all. Such low levels can occur through exposure to cyberbullying, as demonstrated by Pabian et al. (2016).

Moral disengagement. Social Cognitive Theory defines moral disengagement as the selective or total deactivation of the self-regulatory system that controls moral behaviour through specific cognitive mechanisms which legitimise inhumane behaviours (Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 1996).

The results found by DeSmet et al. (2016) show, as one might expect, that higher levels of moral disengagement are associated with bad intentions and negative behaviours on the part of bystanders, while low levels of moral disengagement in the blaming of the victim encourage bystanders to try and help them. These results corroborate the findings of a number of qualitative studies, including DeSmet et al. (2012, 2014) and Price et al. (2014), which show that justifications related to moral disengagement act as a barrier to aiding the victim. Nevertheless, Price et al. (2014) predominantly found high levels of moral commitment among youths, and DeSmet et al. (2012) cite these high levels as being a facilitator for positive bystander behaviour. For their part, Van Cleemput et al. (2014) draw upon the theory of moral disengagement to explain passive bystander behaviour.

Behavioural determinants. The label ‘behavioural determinants’ includes the following individual factors used in the research projects analysed in this literature review, which belong to social cognitive theory or are related to it: Attitudes, Self-efficacy (social and emotional), Outcome expectations, Impulsivity, Social anxiety, Self confidence, Self-esteem and Loneliness (social and emotional).

Self-efficacy, people’s perception of their own ability to achieve set goals and control the events of their own lives (Bandura, as cited in Van Cleemput et al., 2014) in its social and emotional dimensions (Olenik-Shemesh et al., 2015), is positively related to the desire to help the victim (DeSmet et al., 2016). In particular, DeSmet et al. (2012) found higher levels of self-efficacy in offering consolation or advice to the victim than in actually standing up to the aggressor directly. In addition, this perception increases when one expects to receive social support, which may happen because a circumstance is obviously unfair, because the bystander is popular, or because they proactively seek that support from others. On the other hand, Olenik-Shemesh et al. (2015) found no differences in levels of self-efficacy between those active bystanders who defend the victim and those who remain passive. Thomas et al. (2012) and Macháčková et al. (2015) argue that social self-efficacy acts as a facilitator of bystander behaviour in defence of the victim.

The polar opposite of self-efficacy is the fear of negative judgement on the part of others, which is part of social anxiety (Van Cleemput et al., 2014). However, this factor is not found to be a good predictor of bystander behaviour, and is not related to joining in the bullying, assisting the victim or sitting on the sidelines.

Whilst attitudes toward cyberbullying, or the overall affective value attached to the phenomenon (Pabian et al., 2016), are negative, we know that they are associated with positive bystander behaviour in online and offline bullying situations (Nickerson, Aloe, Livingston, & Feeley, as cited in Pabian et al., 2016). Other views collected by DeSmet et al. (2016), such as a negative attitude towards remaining passive, a positive attitude toward reporting the incident and a negative attitude toward laughing at the victim, are associated with the intention to help the victim or confront the bully, whilst a positive attitude towards passive behaviour is associated with the intention of behaving negatively on the part of bystanders.

Another positive predictor of victim support, according to Macháčková et al. (2013), is prosocial behaviour, which refers to the tendency to offer comfort or support to anyone who needs it. These authors also included self-esteem as a variable in their study, defined as a person’s overall negative or positive attitude towards themselves (Rosenberg, Schooler, Schoenbach, & Rosenberg, 1995), though the results show that self-esteem does not influence assistive behaviour in bystanders.

Investigations such as that by Erreygers et al. (2016), into impulsivity and poor self-control, conclude that the most impulsive bystanders are less likely to help the victim, perhaps because to offer help in that situation is somewhat complex, and requires certain inhibitory skills.

Finally, DeSmet et al. (2012) found that expectations partly account for bystanders’ behaviour; this factor is directly related to the category of social environment. In addition, outcome expectations, such as the risk of defending the victim or reporting the incident to the teachers, if they do not preserve the bystanders’ anonymity or blame them for reporting the incident, to a certain degree, act as barriers to mobilisation in support of the victim. On the other hand, if the actions are expected to benefit the victim, this expectation acts as a facilitator to assistance (DeSmet et al., 2016).

Previous experience with bullying and cyberbullying. Some of the studies took account of whether the bystanders in cyberbullying had previously been victims or aggressors in offline and/or online bullying (Barlinska et al., 2013; DeSmet et al., 2016; Van Cleemput et al., 2014). Those who admit to having been victims of bullying or cyberbullying in the past manifest a stronger intention to help the victims, as revealed by DeSmet et al. (2016) and Van Cleemput et al. (2014). On the other hand, in the view of Barlinska et al. (2013), actually having been a bully in an online context is a factor which increases bystanders’ negative behaviour. Van Cleemput et al. (2014) add that joining in the bullying is related to prior experience of being a bully, be it online or off.

Demographic and socio-economic data. The variables of age and gender have been widely used in these studies as control variables. In some cases, they are analysed and an attempt is made to link them with the observed behaviour, but the results are contradictory or relatively meaningless (Barlinska et al., 2013, 2015, Bastiaensens et al., 2014, 2016; DeSmet et al., 2016; Erreygers et al., 2016; Macháčková et al., 2013; Olenik-Shemesh et al., 2015; Van Cleemput et al., 2014). For instance Barlinska et al. (2015) state that age and gender have no influence in bystander’s behaviour. But for Olenik-Shemesh et al. (2015), DeSmet et al. (2016) and Bastiaensens et al. (2016) girls tend more to act on behalf of the victim. On the other hand in the study of Van Cleemput et al. (2014) the younger are more likely to help, while for Olenik-Shemesh et al. (2015) are the older ones.

Discussion

Of all the factors analysed, friendship and the social environment are particularly relevant contextual factors. To begin with, most of the research that examines the relationship between bystanders and victims/perpetrators views friendship as an influential factor in peer behaviour, both in online contexts (Bastiaensens et al., 2014, 2015; DeSmet et al., 2012, 2014, 2016; Huang & Chou, 2010; Jones et al., 2011; Macháčková et al., 2013; Price et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2012; Van Cleemput et al., 2014) and offline ones (Bollmer, Milich, Harris, & Maras, 2005; Boulton, Trueman, Chau, Whitehand, & Amatya, 1999; Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro, & Bukowski; 1999; Menesini, Codecasa, Benelli, & Cowie, 2003). When the victim has friendly relations with the bystanders, they are more likely to act directly or indirectly in support of the victim. Meanwhile, if there is a prevailing friendship between bystanders and bully, they will tend to do nothing or indeed join in. Secondly, the phenomenon of bullying has a social and group aspect to it, which must be taken into account in order to gain an understanding (O'Connell, Pepler, & Craig, 1999, Salmivalli et al., 1996). In view of the influence one’s peers have and the weight which friendship carries, we believe that research in this area could be moved forward by seeking to answer the question: which bystander behaviours are capable of spurring their friends, and others, to action in support of the victim in cases of cyberbullying?

Additionally, having established the continuity and overlap in the social relationships that exist between youths’ online and offline worlds, we can see that it is crucially important to take both environments and the influence of the group, peers or adults, on bystanders’ behaviour into account. Published studies in traditional bullying and cyberbullying both concur as to the importance of the social environment as a condition for action taken by peers (Bastiaensens et al., 2016; DeSmet et al., 2014, 2016; Hinduja & Patchin, 2013; Olenik-Shemesh et al., 2015; Pozzoli & Gini, 2010; Price et al., 2014; Salmivalli & Voeten, 2004; Thomas et al., 2012).

It is also worth noting that Bastiaensens et al. (2016) found that the behaviour of other bystanders in itself does not have much of an effect, but needs to be viewed in relation to other factors, such as the identity of those other bystanders. For example, there is a positive correlation between the action of bystanders who defend the victim and the inhibition to reinforce the bully if the defenders are one’s own friends, although there is also a positive correlation with backing up the bully if other friends do likewise.

Furthermore, some investigations have studied novel factors referring to the characteristics of technology-mediated communication. For example, it is often challenging to assess the situation being witnessed in virtual environments (DeSmet et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2012; Van Cleemput et al., 2014). In addition, time management is different from face-to-face situations: it is difficult to know whether a situation has been resolved and is already over, or on the contrary whether it is still unfolding and whether or not others are already intervening. Other intervention barriers are: the online disinhibition effect, relations with people outside of one’s own social context, not being able to instantly determine the consequences of the bullying for the victim, the offender and other witnesses (Barlinska et al., 2013; Bastiaensens et al., 2015). Yet while these characteristics inhibit people from defending the victims or confronting the perpetrators, it has been reported that an explicit request for help is an effective strategy that favours the victim (Holfeld, 2014; Macháčková et al., 2013).

Of the personal factors at play, empathy, moral disengagement and self-efficacy are particularly important. Yet, as we have seen, attitudes and expectations can also play a significant role.

In relation to empathy, we have seen that the studies analysed in this review link high levels of empathy with positive bystander behaviours (Barlinska et al., 2013, 2015; Erreygers et al., 2016; Macháčková et al., 2015; Van Cleemput et al., 2014), and low empathy levels with negative behaviours (Van Cleemput et al., 2014). These results are similar to those obtained in research into bystander behaviour in the context of conventional bullying (Gini, Albiero, Benelli, & Altoe, 2008; Pöyhönen et al., 2010). These studies do, however, highlight that defensive behaviour on the part of bystanders is attributable not only to their empathy levels, but to the interaction with other factors such as their perceived social self-efficacy or their level of popularity (Gini et al., 2008; Pöyhönen et al., 2010). On the other hand, there is a unanimous finding that there is a positive link between high levels of moral disengagement and negative behaviours by bystanders (DeSmet et al., 2012, 2014, 2016; Price et al., 2014; Van Cleemput et al., 2014). Similarly, there is consensus as to the link between high levels of self-efficacy and positive behaviour (DeSmet et al., 2012, 2016; Macháčková et al., 2015; Olenik-Shemesh et al., 2015; Thomas et al., 2012). It should not go unnoted, though, that Olenik-Shemesh et al. (2015) also found high levels of self-efficacy in passive bystanders.

In view of these results, it can be deduced that high levels of cognitive and affective empathy, low levels of moral disengagement and high levels of self-efficacy serve as facilitators in the mobilisation of bystanders to defend and support the victim in cases of cyberbullying. However, it would also be of interest to examine the interrelation between these factors in the behaviour of cyberbystanders, as with traditional bullying (Gini et al., 2008; Pöyhönen et al., 2010).

In general, if we take account of the wide range of factors studied here and their behavioural impact, it can be observed that there is no single determining factor in whether or how bystanders assist the victim; rather, there is an interaction between all these different factors, contextual and personal, which have a moderating effect on the end result.

The literature review presented above is not without a few limitations. First of all, the factors that moderate bystanders’ actions in online contexts are a relatively new field of study. Therefore, we do not have strong evidence of the factors presented, given that the number of studies relative to each factor is limited. Secondly, it must be highlighted that in some of the categories, various factors have been grouped together. For instance, in friendships, we have included the variety of relationships that bystanders establish with peers – victim or perpetrator. Likewise, the social environment incorporates factors such as social and group norms, social pressure and social support, injunctive and descriptive norms. Friendships and social environment are not specific factors which have been conceived of to be studied in a functional way. Thirdly, there is only limited research currently available into the particular constraints of technology-mediated communication and virtual environments; it might be expected that as this research grows, new evidence could be uncovered.

Ultimately, in light of our analysis of the range of factors identified, it is possible to make a number of prudent suggestions which should be taken into account when devising strategies to prevent cyberbullying, listed below: (a) focus on the importance of victims asking their friends for help in dealing with the bullies; (b) promote a school climate which weighs against bullying and in support of the victims, attaching relevance to bystander intervention; (c) foster relations of friendship in the contexts where they can occur – especially in school; (d) activate and publicise resources for the prevention and detection of bullying, both on and offline, which involve the young people and other members of the community and improve perceived self-efficacy; (e) show the psychological harm that cyberbullying causes in the victims; (f) increase whole-group empathy to prevent desensitisation to cyberbullying and encourage bystander mobilisation (Pabian et al., 2016); and finally, (g) reduce levels of moral disengagement.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2018 ernando Domínguez-Hernández, Lars Bonell, Alejandro Martínez-González