Threatened individuals prefer positive information during Internet search: An experimental laboratory study

Vol.12,No.1(2018)

The Internet is the main source for information search and it is increasingly used in the health domain. Such self- relevant Internet searches are most probably accompanied by affective states such as threat (e.g., being afraid of a serious illness). Thus, threat can influence the entire Internet search process. Threat is known to elicit a preference for positive information. This positive bias has recently been shown for separate steps of the Internet search process (i.e., selection of links, scanning of webpages, and recall of information). To extend this research, the present study aimed at investigating the influence of threat across the Internet search process. We expected that threatened individuals similarly prefer positive information during this process. An experimental laboratory study was conducted with undergraduate students (N = 114) enrolled in a broad range of majors. In this study, threat

was manipulated and then participants were to complete a preprogrammed, realistic Internet search task which was used to assess selection of links, scanning of webpages, and recall of information. The results supported our hypothesis and revealed that, during the Internet search task, threatened individuals directed more attention to positive information (i.e., selected more positive links and scanned positive webpages longer) and, as a consequence, also recalled more positive information than non-threatened individuals. Thus, our study shows that not only separate steps but also the Internet search process as such is susceptible to being influenced by affective states such as threat.

Internet search; health-related information; threat; counter-regulation; self-relevance

Hannah Greving

Leibniz-Institut für Wissensmedien, Tübingen, Germany

Hannah Greving is a research scientist at the Leibniz-Institut für Wissensmedien, Tübingen, Germany. She is

interested in information processing and emotions as well as knowledge construction processes on the Internet.

Kai Sassenberg

Leibniz-Institut für Wissensmedien, Tübingen, Germany Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany

Kai Sassenberg is head of the Social Processes Lab at the Leibniz-Institut für Wissensmedien, Tübingen, and full

professor at the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Germany. His research focuses on self- and emotion-

regulation in the context of Internet use and social relationships (e.g., group membership, social power,

leadership).

Andrewes, D. (2001). Neuropsychology: From theory to practice. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Becker, D., Grapendorf, J., Greving, H., & Sassenberg, K. (2018). Perceived threat and Internet use predict intentions to get bowel cancer screening (colonoscopy): A longitudinal questionnaire study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20, e46. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9144

Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1996). The biopsychosocial model of arousal regulation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 28, 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60235-X

Brand-Gruwel, S., Wopereis, I., & Vermetten, Y. (2005). Information problem solving by experts and novices: Analysis of a complex cognitive skill. Computers in Human Behavior, 21, 487–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2004.10.005

Brand-Gruwel, S., Wopereis, I., & Walraven, A. (2009). A descriptive model of information problem solving while using internet. Computers & Education, 53, 1207–1217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.06.004

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Davis, M. J. (2010). Contrast coding in multiple regression analysis: Strengths, weaknesses, and utility of popular coding structures. Journal of Data Science, 8, 61–73.

Fallows, D. (2008). Search engine use. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2008/PIP_Search_Aug08.pdf.pdf

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Fox, S. (2011). Health topics. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2011/PIP_Health_Topics.pdf

Fox, S., & Duggan, M. (2013). Health online 2013. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/PIP_HealthOnline.pdf

Fox, S., & Jones, S. (2009). The social life of health information. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/PIP_HealthOnline.pdf

Fu, W.-T., & Pirolli, P. (2007). SNIF-ACT: A cognitive model of user navigation on the World Wide Web. Human– Computer Interaction, 22, 355–412.

Gerjets, P., Kammerer, Y., & Werner, B. (2011). Measuring spontaneous and instructed evaluation processes during web search: Integrating concurrent thinking-aloud protocols and eye-tracking data. Learning and Instruction, 21, 220–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.02.005

Ginsberg, J., Mohebbi, M. H., Patel, R. S., Brammer, L., Smolinski, M. S., & Brilliant, L. (2009). Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature, 457, 1012–1014. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07634

Greving, H., & Sassenberg, K. (2015). Counter-regulation online: Threat biases retrieval of information during Internet search. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.077

Greving, H., Sassenberg, K., & Fetterman, A. (2015). Counter-regulating on the Internet: Threat elicits preferential processing of positive information. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 21, 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000053

Jonas, E., McGregor, I., Klackl, J., Agroskin, D., Fritsche, I., Holbrook, C., … Quirin, M. (2014). Threat and defense: From anxiety to approach. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 219–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800052-6.00004-4

Kammerer, Y., & Gerjets, P. (2011). Searching and evaluating information on the WWW: Cognitive processes and user support. In K.-P. L. Vu & R. W. Proctor (Eds.), Handbook of human factors in Web design (2nd ed., pp. 283–302). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Kammerer, Y., & Gerjets, P. (2012). Effects of search interface and internet-specific epistemic beliefs on source evaluations during web search for medical information: An eye-tracking study. Behaviour & Information Technology, 31, 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2011.599040

Kammerer, Y., & Gerjets, P. (2014). The role of search result position and source trustworthiness in the selection of Web search results when using a list or a grid interface. International Journal of Human-Computer-Interaction, 30, 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2013.846790

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Free Press.

Lo, B., & Parham, L. (2010). The impact of Web 2.0 on the doctor–patient relationship. Journal of Law, Medicine, & Ethics, 38, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-720X.2010.00462.x

Morahan-Martin, J. M. (2004). How internet users find, evaluate, and use online health information: A cross-cultural review. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7, 497–510.

Murray, E., Lo, B., Pollack, L., Donelan, K., Catania, J., White, M., … Turner, R. (2003). The impact of health information on the Internet on the physician–patient relationship. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163, 1727–1734. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.14.1727

Neter, J., Kutner, M. H., Nachtschiem, C. J., & Wasserman, W. (1996). Applied linear statistical models (4th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Pirolli, P. (2005). Rational analyses of information foraging on the Web. Cognitive Science, 29, 343–373. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog0000_20

Pirolli, P. (2007). Information foraging theory. Adaptive interaction with information. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pirolli, P., & Card, S. (1999). Information foraging. Psychological Review, 106, 643–675. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.643

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Purcell, K. (2011). Search and email still top the list of most popular online activities. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2011/PIP_Search-and-Email.pdf

Purcell, K., Brenner, J., & Rainie, L. (2012). Search engine use 2012. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2012/PIP_Search_Engine_Use_2012.pdf

Rothermund, K. (2011). Counter-regulation and control-dependency. Social Psychology, 42, 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000043

Rothermund, K., Gast, A., & Wentura, D. (2011). Incongruency effects in affective processing: Automatic motivational counter-regulation or mismatch-induced salience? Cognition and Emotion, 25, 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.537075

Rothermund, K., Voss, A., & Wentura, D. (2008). Counter-regulation in affective attentional biases: A basic mechanism that warrants flexibility in emotion and motivation. Emotion, 8, 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.1.34

Rouet, J.-F., Ros, C., Goumi, A., Macedo-Rouet, M., & Dinet, J. (2011). The influence of surface and deep cues on primary and secondary school students’ assessment of relevance in web menues. Learning and Instruction, 21, 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.02.007

Sassenberg, K., & Greving, H. (2016). Internet searching about disease elicits a positive perception of own health when severity of illness is high: A longitudinal questionnaire study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18, e56. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5140

Sassenberg, K., Sassenrath, C., & Fetterman, A. K. (2015). Threat ≠ prevention, challenge ≠ promotion: The impact of threat, challenge, and regulatory focus on attention to negative stimuli. Cognition and Emotion, 29, 188–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2014.898612

Schwager, S., & Rothermund, K. (2013a). Counter-regulation triggered by emotions: Positive/negative affective states elicit opposite valence biases in affective processing. Cognition and Emotion, 27, 839–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2012.750599

Schwager, S., & Rothermund, K. (2013b). Motivation and affective processing biases in risky decision making: A counter-regulation account. Journal of Economic Psychology, 38, 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2012.08.005

Schwager, S., & Rothermund, K. (2014). On the dynamics of implicit emotion regulation: Counter-regulation after remembering events of high but not of low emotional intensity. Cognition and Emotion, 28, 971–992. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.866074

Shepperd, J., Malone, W., & Sweeny, K. (2008). Exploring causes of the self-serving bias. Social and Personality Compass, 2, 895–908. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00078.x

Taylor, S. E. (1991). Asymmetrical effects of positive and negative events: The mobilization-minimization hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.67

Tomaka, J., Blascovich, J., Kibler, J., & Ernst, J. M. (1997). Cognitive and physiological antecedents of threat and challenge appraisal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.63

Walraven, A., Brand-Gruwel, S., & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (2013). Fostering students‘ evaluation behaviour while searching the internet. Instructional Science, 41, 125–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-012-9221-x

Ward, A. F. (2013). One with the Cloud: Why people mistake the Internet’s knowledge for their own [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Editorial Record:

First submission received:

November 30, 2016

Revisions received:

December 6, 2017

January 16, 2018

April 5, 2018

Accepted for publication:

April 6, 2018

Introduction

The Internet has become the central, non-human source for information searches (Fallows, 2008; Purcell, 2011; Purcell, Brenner, & Rainie, 2012). Hence, Internet searches are frequently conducted in self-relevant domains providing important information influencing how the self or one’s current situation are assessed. For example, the Internet is increasingly used for searches in the health domain (Fox, 2011; Fox & Duggan, 2013; Morahan-Martin, 2004). Searches in this domain are conducted that frequently that even influenza epidemics can be traced back by log files of search engines (Ginsberg et al., 2009).

Due to their self-relevance, Internet searches for health purposes are most probably accompanied by emotions and affect (Fox, 2011; Fox & Duggan, 2013; Morahan-Martin, 2004). For example, when doing health-related Internet searches, individuals may fear to be severely ill and feel threatened. In turn, affect and emotions, such as threat, will impact on the entire process of Internet search. Threat and other similarly negative affective states are known to elicit a preference for positive information (Rothermund, Voss, & Wentura, 2008; Schwager & Rothermund, 2013a, 2014; Shepperd, Malone, & Sweeny, 2008; Taylor, 1991; for an overview see Jonas et al., 2014). This positive bias has recently also been demonstrated for Internet search (e.g., Becker, Grapendorf, Greving, & Sassenberg, 2018; Greving & Sassenberg, 2015; Greving, Sassenberg, & Fetterman, 2015; Sassenberg & Greving, 2016).

Yet, the aforementioned research focused primarily on separate steps of the Internet search process and their search outcomes (Greving & Sassenberg, 2015; Greving et al., 2015), but it did not investigate the entire Internet search process (with one exception, see Greving et al., 2015, Study 1, discussed below) in a controlled manner. The aim of the present research was to investigate the influence of threat on the Internet search process (i.e., selection of links, scanning of webpages, and recall of information). For this purpose, we used an experimental procedure that (1) examined the Internet search process with one single task and (2) allowed for spontaneous search behavior but still provided sufficient experimental control. Therefore, the current study contributed to existing research by extending the understanding of the impact of threat on the Internet search process.

Internet Search

On the Internet, a heterogeneous breadth and wealth of information is available. In order to examine how individuals deal with such information, several models were suggested. One line of models conceptualizes Internet search in a cognitive way: Internet search takes place when the semantic similarity between textual cues online and individuals’ information needs is high (for an overview see Pirolli, 2007; Pirolli & Card, 1999). This similarity is also called informational relevance and can be modeled by computer programs (e.g., Fu & Pirolli, 2007; Pirolli, 2005).

Another line of models we are focusing on represents Internet search as a process where searchers go through consecutive steps (e.g., Brand-Gruwel, Wopereis, & Vermetten, 2005; Brand-Gruwel, Wopereis, & Walraven, 2009; Rouet, Ros, Goumi, Macedo-Rouet, & Dinet, 2011). The Internet search process involves that individuals deal with information by selecting links from search engine result pages (SERPs), scanning webpages, and thoroughly processing and recalling information from webpages (Brand-Gruwel et al., 2005, 2009; Greving et al., 2015). The process of Internet search is, in other words, a complex process (Brand-Gruwel et al., 2005, 2009; see also Kammerer & Gerjets, 2011). Yet, individuals often do not perceive Internet search as such a process. Although they believe in their searching abilities and the accuracy of information provided online (Brand-Gruwel et al., 2009; Fallows, 2008; Purcell et al., 2012; Ward, 2013), individuals nevertheless often fail to identify correct or incorrect information because they mostly attend to surface cues (e.g., select the first links of a SERP; Gerjets, Kammerer, & Werner, 2011; Kammerer & Gerjets, 2012, 2014; Rouet et al., 2011; Walraven, Brand-Gruwel, & Boshuizen, 2013). As individuals already struggle with finding valid information when they are supposedly motivated to find accurate information, affective and motivational states accompanying Internet search should affect successful Internet searches even more. In the current research, we focus on the influence of the negative affective state of threat.

Threat and its Influence on Internet Search

Threat is defined as a negative affective state in which individuals have the feeling of not being able to deal with high situational demands (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996). The counterpart of threat is challenge under which individuals assume to be able to deal with high situational demands (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996). Thus, threat is a negative affective state, whereas challenge is an engaging and positive affective state. For example, individuals may feel threatened by an illness when they are not able to participate in everyday life due to their illness. Or students may feel threatened by an upcoming exam when they perceive themselves as not being able and not sufficiently prepared to pass the exam.

Threat influences a range of behaviors (for an overview see Jonas et al., 2014). In particular, threat has an influence on information processing (Rothermund, 2011; Rothermund et al., 2008; Rothermund, Gast, & Wentura, 2011; Schwager & Rothermund, 2013a, 2013b, 2014). That is, threat elicits counter-regulation (Rothermund, 2011; Rothermund et al., 2008, 2011; Schwager & Rothermund, 2013a, 2013b, 2014). Counter-regulation (Rothermund, 2011) is defined as selective attention allocation towards information which is in contrast to one’s own current state: Individuals in a negative affective state preferably attend to and process positive information whereas individuals in a positive affective state preferably attend to and process negative information. For example, several studies have illustrated that in a negative (affective) state (e.g., when participants were at risk to lose money or when they felt bad), participants’ attention was directed more towards positive information than in a positive (affective) state (e.g., when participants had the opportunity to win money or felt good; Rothermund et al., 2008, 2011, Study 1; Schwager & Rothermund, 2013a). Such a valence bias has similarly been demonstrated for threat and challenge that are prototypical instances of a negative and a positive state (Sassenberg, Sassenrath, & Fetterman, 2015). Under threat individuals pay more attention to positive information whereas when feeling challenged, they pay more attention to negative information.

According to Rothermund (2011), selective attention allocation of counter-regulation is functional because it helps deescalate motivational orientations. Directing one’s attention to merely positive information in a positive affective state, such as challenge, would be careless because important negative information could be overlooked which may hinder goal attainment. The focus on negative information in a positive affective state may help staying focused and support successful goal attainment. In contrast, directing one’s attention only to negative information in a negative affective state, such as threat, would be dysfunctional and would hinder successful goal attainment. Yet, the focus on positive information could help prevent an escalation of the negative affective state and may contribute to successful goal attainment. Therefore, this principle is referred to as counter-regulation.

Recent research has shed light on the fact that preferring positive information under threat also occurs during Internet search (Greving & Sassenberg, 2015; Greving et al., 2015). Following the counter-regulation principle (Rothermund, 2011), counter-regulation should particularly occur under conditions that allow individuals to flexibly and adaptively deal with information. Internet search provides these particular conditions as it is a highly self-directed process and, thus, gives individuals sufficient opportunities to counter-regulate threat (e.g., Rothermund, 2011). To be more specific, recent research has shown that threatened individuals selected more positive links, scanned positive webpages longer, and processed and recalled more positive information than non-threatened individuals (Greving et al., 2015). Thus, this research demonstrated that threat influences Internet search behavior.

Yet, the above-mentioned research had three limitations. First, across all studies either a challenge condition (Greving et al., 2015), that is, a control condition commonly used in research on threat (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996), or a neutral condition (Greving & Sassenberg, 2015) served as control condition. Hence, threat has not been investigated in comparison to both of these adequate control conditions. Second, the studies under this research focused mainly on separate steps of Internet search (e.g., the generation of search terms, the selection of links from a predefined SERP; Greving & Sassenberg, 2015; Greving et al., 2015, Study 2 + 3), even though Internet search certainly involves going through an iterative process (e.g., Brand-Gruwel et al., 2009). Only one of these studies focused on the entire Internet search process (Greving et al., 2015, Study 1). Although externally valid, this study lacked experimental control in the procedure and the materials as participants were not restricted in their searching behavior. Such a lack of experimental control may have caused confounds. Third, in the only study dealing with the entire search process, one third of the sample had to be excluded because the participants concerned did not follow the manipulation instructions (i.e., applying post-hoc generated criteria), which was suboptimal and which could have similarly limited the study results. In order to deal with these limitations, we conducted the present study.

The Current Study

The general aim of the current study was to investigate the influence of threat on the Internet search process. In order to extend earlier research, we aimed to address the three above-mentioned limitations of previous research on the impact of threat during Internet searches, namely that there was no study comparing threat to challenge and a neutral control condition, that there was no study covering the whole search process, and that an ineffective manipulation had been applied in earlier research. Therefore, we (1) implemented both a challenge and a neutral control condition in the present study, (2) investigated the process of Internet search with a more experimentally controlled procedure, and (3) applied an effective manipulation that was sufficiently strong and clear. Thus, the current study increases the understanding of the impact of threat on the Internet search process, which has so far not been investigated.

First, we hypothesized that threatened individuals select more positive links and scan positive webpages longer than challenged individuals and individuals in a neutral state. Second, we hypothesized that, because threatened individuals select more positive links and scan positive webpages longer, they recall more positive information than individuals in both control conditions. These hypotheses were tested in a study in which we manipulated threat and then asked participants to complete an Internet search task. This task was completely preprogrammed but designed in a way to make it appear as if it were a usual Internet search surface. Thereby, participants’ behavior during the search task resembled actual searching behavior, but, due to the programming, we could nonetheless assess it precisely.

Method

Participants and Design

One hundred and fourteen participants (86 female, 28 male, Mage = 22.04, SD = 3.24, range: 18 – 33 years) took part in the study which was conducted in Germany. Participants were all undergraduate students (Msemester = 4.28, SD = 3.56) who were enrolled in majors such as natural sciences, physics, biology, geography, social sciences, history, philosophy, sociology, theology, law, and business sciences. They were recruited via an online recruiting system that allowed participants to autonomously sign up. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions of a one-factorial design (affective state: threat vs. neutral vs. challenge).

The study was part of a one hour lab session. In this session, for time and efficiency reasons two different studies were conducted. The present study was done as second study and was not influenced by any manipulation from the first study which was unrelated with regard to the content.1 Participants received €8 (approx. $9) for taking part in the entire one hour lab session. Two participants were excluded from the analyses reported below. They were residuals in regression analyses of the main dependent variables positive bias in link selection, positive bias in webpage scanning, and positive bias in recall on affective state based on studentized deleted residuals (> 2.65; Neter, Kutner, Nachtschiem, & Wasserman, 1996).

Procedure and Materials

The study took place in a laboratory with six semiprivate cubicles, each equipped with a computer. Participants received all instructions and measures via the computer screen. After participants had signed the consent form, we induced affective state with the manipulation. To manipulate affective state, we did not use health-related threat, because this would not only ethically be problematic, but it would also lead to a confound from an experimental perspective. Manipulating affective state within the domain in which participants conduct an Internet search might have altered the valence of the domain (e.g., a health domain might have been more negative for health threatened individuals than for non-threatened individuals) and, thus, also the information reception. Hence, a manipulation in the health domain might have caused a confound. In order to make experimentally valid statements and to ensure that only the manipulation and nothing else caused the effects, we decided to use an incidental manipulation of threat. This manipulation targets the same process described in the literature (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996; Rothermund, 2011), is known to be effective, and has successfully been used before (Greving & Sassenberg, 2015; Greving et al., 2015). In particular, participants in the threat/challenge condition were asked to think about a situation in which they were unable/able to deal with high situational demands and received the following instructions:

“Please think about a situation of your studies or private life that is highly demanding at the moment and that you have great difficulties to deal with.” / “Please think about a situation of your studies or private life that is highly demanding at the moment and that you are very well able to deal with.”

These instructions exactly match the definitions of threat and challenge (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996) and have been successfully used before (cf. Greving & Sassenberg, 2015; Greving et al., 2015). In contrast, participants in the control condition were asked to think about a neutral situation and received this instruction:

”Please think about a common and typical situation of your studies or private life.”

This instruction has also been successfully implemented before (cf. Greving & Sassenberg, 2015). In all conditions, participants had to describe the situation and their feelings in a few sentences. After that, a manipulation check followed. The subsequent tasks were presented as a separate study. This was done to ensure that participants were unaware of the relation between the affective state manipulation and the subsequent assessment of the dependent measures. Thus, we wanted to rule out demand effects in the subsequent tasks.

Next, an information search task followed in which participants were to inform themselves about living organ donation. For students, who usually make up the largest part of our samples, living organ donation is a quite relevant topic. That is because students could all be suitable organ donors due to their age. Students are also in a stage of life in which own decisions, such as about living organ donation, are becoming increasingly common. Moreover, living organ donation has clear positive (e.g., it can save and extend lives), negative (e.g., it necessitates a painful surgery with possible side effects), and neutral aspects (e.g., it has a history and involves the decision of a committee). Therefore, it is an appropriate topic for our materials and the assessment of valence biases. To ensure experimental control over the materials, the information search process started with a SERP for the search term ‘living organ donation’ which was identical for all participants and looked like a common SERP containing 16 links. These links were presented in a 4x4 table format rather than a list format to prevent selection effects due to the order of results (Kammerer & Gerjets, 2011). Four links were neutral links (e.g., organ donation committee), 6 links were positive links (e.g., living organ donation gives a new life), and the other 6 links were negative links (e.g., severe pain after operation). In the 4x4 table, each row and each column contained one neutral and alternately two positive links and one negative link, or two negative links and one positive link (see Appendix). Each of these links referred to a webpage (i.e., 4 neutral, 6 positive, and 6 negative webpages). Each of these webpages contained a header with the exact wording of the respective link and a short text which provided more information on the topic of the link. The length of these texts ranged between 72 and 95 words.

After this task, a 5-minute filler task followed, which is a common procedure in research including memory measures (cf. Greving & Sassenberg, 2015; Greving et al., 2015). This filler task was used to prevent that the information participants had dealt with last during the information search task and which was still in their short-term memory affected the subsequent free recall task. In this filler task, participants were asked to count all triangles in an abstract drawing with lines (Andrewes, 2001, p. 169). Subsequently, participants had to recall what they had learned about living organ donation. Finally, participants were debriefed, received their compensation, and were dismissed.

Measures

Manipulation check. The manipulation check was assessed with two items (e.g., Tomaka, Blascovich, Kibler, & Ernst, 1997). The first item measured the demands of the situation participants had described during the manipulation (i.e., “How demanding is the situation you just described?”) on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all demanding) to 7 (very demanding). The second item measured participants’ ability (i.e., resources) to deal with this situation (i.e., “How well can you deal with the situation you just described?”) on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all well) to 7 (very well). These items directly match the definitions of threat and challenge (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996). On average, participants appraised the demands and resources as relatively high and above the midpoint of the scale (Mdemands = 5.65, SD = 1.29; Mresources = 4.82, SD = 1.48).

Positive bias in attention. With the information search task, we first assessed the number and frequency of selected neutral, positive, and negative links. To calculate the positive bias in link selection, we subtracted the number of selected negative links from the number of selected positive links and divided the result by the total number of selected links. On average, participants selected M = 2.48 neutral links (SD = 1.39, range: 0–5), M = 2.79 positive links (SD = 2.23, range: 0–7), and M = 3.19 negative links (SD = 2.21, range: 0 – 8), and clicked overall on M = 8.46 links (SD = 5.12, range: 0–18). Second, we measured the time spent on neutral, positive, and negative webpages. The duration from entering the webpage to leaving the webpage was measured in seconds. To calculate the positive bias in webpage scanning, we subtracted the time spent on negative webpages from the time spent on positive webpages and divided the result by the total amount of time spent on webpages. On average, participants stayed on neutral webpages for M = 47 seconds (SD = 34, range: 0–122), on positive webpages for M = 48 seconds (SD = 45, range: 0–178), and on negative webpages for M = 54 seconds (SD = 43, range: 0–182), and stayed overall on the webpages for M = 149 seconds (SD = 103, range: 0–427). Positive bias in webpage scanning and positive bias in link selection were correlated (r = .89).

Positive bias in recall. Using the texts participants had written during the free recall task, we determined the valence of the recall. To this end, a coding scheme related to the content was developed beforehand, based on the valence of specific pieces of information. To be more precise, the coding scheme categorized 192 meaningful pieces of information from the texts on the webpages into a neutral category (60 pieces of information), a positive category (66 pieces of information), and a negative category (66 pieces of information; for examples of information within each category, see description of the procedure and Appendix). Based on this coding scheme, two independent raters coded participants’ texts by classifying each piece of recalled information into the neutral, positive, or negative category (agreement all r’s > .85). Thus, the raters created the scores proceeding from the counts in each category, and the scores were averaged later. To calculate the positive bias in recall, we subtracted the number of recalled negative pieces of information from the number of recalled positive pieces of information and divided the result by the total number of recalled pieces of information. On average, participants recalled M = 3.90 pieces of neutral information (SD = 3.49, range: 0–17), M = 1.83 pieces of positive information (SD = 2.04, range: 0–8), and M = 3.13 pieces of negative information (SD = 2.71, range: 0–14), and recalled overall M = 8.86 pieces of information (SD = 5.68, range: 0–29).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Before running the main analyses, we checked whether the manipulation was successful. We conducted a univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) for each of the two manipulation check items. The analyses revealed that participants in the threat condition (M = 6.08, SD = 0.84) and the challenge condition (M = 5.92, SD = 0.98) experienced higher situational demands than participants in the neutral condition (M = 4.86, SD = 1.63), F (2, 110) = 11.45, p < .001, ηp2 = .172. Moreover, participants in the threat condition felt less able to deal with the situation (M = 3.90, SD = 1.43) than participants in the challenge condition (M = 5.41, SD = 1.09) and the neutral condition (M = 5.20, SD = 1.45), F (2, 110) = 14.65, p < .001, ηp2 = .210. This pattern of results exactly matches the definitions of threat and challenge (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996) and, consequently, our manipulation was successful.

Main Analyses

We hypothesized that threatened individuals select more positive links and scan positive webpages longer than challenged individuals and individuals in a neutral state. These hypotheses were derived from previous research on threat (Becker et al., 2018; Greving & Sassenberg, 2015; Greving et al., 2015; Sassenberg & Greving, 2016; see also Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996; Jonas et al., 2014; Rothermund, 2011). As we had clear predictions that the results for threat should be different from the two control conditions and that the two control conditions should not differ in positive bias in link selection and webpage scanning, we conducted orthogonal contrast analyses (e.g., Davis, 2010). Compared to analyses with, for instance, dummy codes, the contrast analyses have the advantage that (1) they have increased statistical power and do not inflate the type I error, (2) they make the interpretation of the results easier because neither irrelevant nor unimportant results have to be interpreted, and (3) they allow researchers to directly test clear, a priori predictions (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003; Davis, 2010; Field, 2013). Like for other codings for categorical variables with more than two levels, k – 1 contrast codes needed to be created. As we had three conditions, we thus needed 2 contrasts. Moreover, the contrast codes had to be consistent with two rules: First, the sum of the contrast coefficients within each contrast code should be zero; second, the sum of the products of each pair of contrast codes should be zero (Cohen et al., 2003; Field, 2013). In line with our prediction, the threat condition was compared with the two control conditions in the first contrast, and the challenge condition was compared with the neutral condition in the second contrast. We therefore determined the first, focal contrast, that is, the contrast of main interest, as threat = 2, neutral = -1, and challenge = -1, which tests the difference between threat and the two control conditions. Moreover, we determined the second, residual contrast as threat = 0, neutral = -1, and challenge = 1, which tests the (unexpected) difference between the two control conditions.2 We consistently used these contrast codes—hereafter referred to as focal contrast and residual contrast—throughout the analyses as predictors in regression analyses.

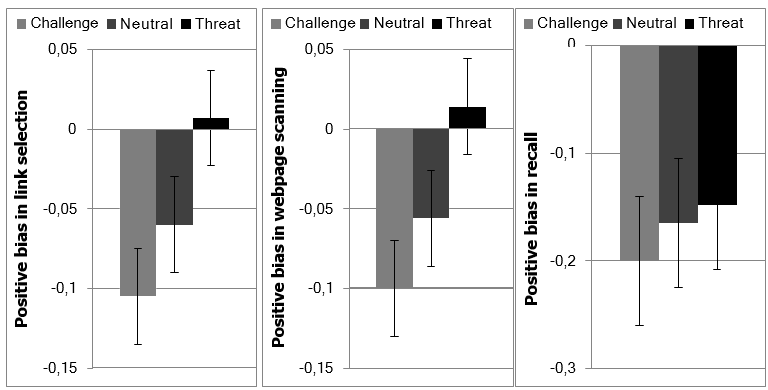

Table 1. Means (Standard Deviations) for the Challenge Condition, the Neutral Condition, and the Threat Condition Separately for the Dependent Variables Positive Bias in Link Selection, Positive Bias in Webpage Scanning, and Positive Bias in Recall.

|

|

Positive bias in: |

Challenge |

Neutral |

Threat |

|

|

Link selection |

-0.105 (0.22) |

- 0.060 (0.17) |

0.007 (0.21) |

|

|

Webpage scanning |

-0.100 (0.21) |

-0.056 (0.20) |

0.014 (0.23) |

|

|

Recall |

-0.200 (0.37) |

-0.165 (0.31) |

-0.148 (0.39) |

Figure 1. Means and standard errors of the dependent variables positive bias in link selection,

positive bias in webpage scanning, and positive bias in recall for

the challenge condition, the neutral condition, and the threat condition.

We regressed positive bias in link selection and positive bias in webpage scanning each on the focal and the residual contrast. These regression analyses revealed that participants in the threat condition selected more positive links (M = 0.007, SD = 0.21) than participants in the neutral condition (M = - 0.060, SD = 0.17) and the challenge condition (M = -0.105, SD = 0.22), bfocal = 0.03, SE = 0.01, β = 0.21, t(111) = 2.24, p = .027, whereas the two control conditions did not differ, bresidual = 0.02, SE = 0.02, β = 0.09, t(111) = 0.96, p = .338 (see Table 1 and Figure 1, on the left). Likewise, participants in the threat condition scanned positive webpages longer (M = 0.014, SD = 0.23) than participants in the neutral condition (M = -0.056, SD = 0.20) and the challenge condition (M = -0.100, SD = 0.21), bfocal = 0.03, SE = 0.01, β = 0.20, t(111) = 2.17, p = .032, but the two control conditions did not differ, bresidual = 0.02, SE = 0.03, β = 0.08, t(111) = 0.90, p = .368 (see Table 1 and Figure 1, in the middle).3

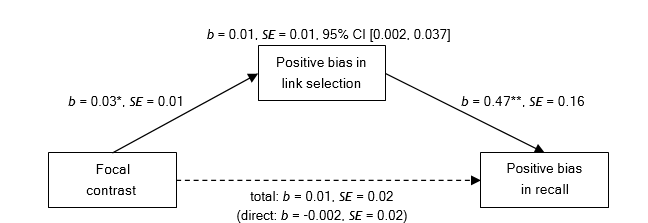

Figure 2. Mediation analysis containing the focal contrast (threat = 2, neutral = -1, challenge = -1),

the positive bias in link selection as mediator, and the positive bias in recall as dependent variable.

We also expected that because threatened individuals select more positive links and scan positive webpages longer, they recall more positive information than individuals in the two control conditions. We again used the same two contrasts as described above following the same rationale and regressed positive bias in recall on the focal and the residual contrast. This regression analysis did not reveal any significant effect, bfocal = 0.01, SE = 0.02, β = 0.05, t(111) = 0.50, p = .622, bresidual = 0.02, SE = 0.04, β = 0.04, t(111) = 0.42, p = .678 (see Table 1 and Figure 1, on the right). We, then, tested whether there was the predicted indirect effect of affective state via positive bias in link selection and positive bias in webpage scanning on positive bias in recall with the SPSS macro provided by Preacher and Hayes (2008). The first mediation analysis with positive bias in link selection as mediator revealed an indirect effect for the focal contrast, b = 0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.002, 0.037] (see Figure 2), but not for the residual contrast, b = 0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [-0.007, 0.046]. The second mediation analysis with positive bias in webpage scanning as mediator similarly revealed an indirect effect for the focal contrast, b = 0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.003, 0.036] (see Figure 3), but not for the residual contrast, b = 0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [-0.008, 0.045]. Thus, these analyses indicated that participants in the threat condition recalled more positive information because they selected more positive links and scanned positive webpages longer compared to participants in the neutral condition and the challenge condition.

Figure 3. Mediation analysis containing the focal contrast (threat = 2, neutral = -1, challenge = -1),

the positive bias in webpage scanning as mediator, and the positive bias in recall as dependent variable.

Discussion

On the Internet, individuals have the opportunity to search for self-relevant information. Such Internet searches can be accompanied by affective states such as threat. Threat is known to elicit a preference for positive information (Rothermund, 2011; Rothermund et al., 2008, 2011; for an overview see Jonas et al., 2014). Such preference is also elicited when threatened individuals perform separate steps of the Internet search process (Greving & Sassenberg, 2015; Greving et al., 2015). We extended this recent research by demonstrating that threatened individuals prefer positive information across the Internet search process: Threatened individuals directed more attention to positive information (i.e., they selected more positive links and scanned positive webpages longer) and, thereby, also recalled more positive information than non-threatened individuals. These results, thus, indicate that threatened individuals seem to deal with their current negative state by attending more to positive information and, consequently, recalling more positive information.

Although we reported the (mediation) analyses separately for positive bias in link selection and webpage scanning, our findings refer to one and the same process. Both, selection of positive links and scanning of positive pages, are (highly correlated) indicators of attention to positive information. By focusing on positive information during Internet search, threatened individuals seem to counter-regulate their state of threat. Thus, the findings reveal that threat does not solely affect single isolated steps of Internet search. Instead, they suggest that threat has an impact on behaviors closely related to the intertwined steps of the Internet search process, which had not been demonstrated before.

The current results are consistent with research on the influence of threat on information processing (Jonas et al., 2014; Rothermund, 2011; Rothermund et al., 2008, 2011). They similarly show a preference for positive information under threat: Threatened individuals allocated more attention to positive information than non-

threatened individuals which is in line with the counter-regulation principle (Rothermund, 2011). Notably, the study also replicates recent research on the influence of threat on Internet search (Greving & Sassenberg, 2015; Greving et al., 2015). That is, the results of the present study illustrate in a similar way that under threat the selection of links, the scanning of webpages, and, consequently, also the recall of information are positively biased. Thus, the present findings complement previous research, suggesting that counter-regulation may play an important role for threatened individuals across the process of Internet search.

The findings of the current study may also extend models of Internet search. These models mainly perceive Internet search as being directed by cognitive aspects (Pirolli, 2007; Pirolli & Card, 1999) or informational relevance (Brand-Gruwel et al., 2009; Gerjets et al., 2011; Kammerer & Gerjets, 2011; Rouet et al., 2011; Walraven et al., 2013). Yet, the present study sheds light on the fact that Internet search is also driven by affective states such as threat which influence the Internet search process. Hence, this study adds to the recent line of studies by consolidating the affective effects of threat on the process of Internet search in a highly experimentally controlled and internally valid setting.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

First, threat was compared to a challenge and a neutral condition which had only separately been investigated before (Greving & Sassenberg, 2015; Greving et al., 2015). The challenge state and the neutral state do not differ regarding the ability to deal with a situation as both states allow doing so. They differ regarding the situational demands: Challenged individuals are facing high demands whereas individuals in a neutral state are facing low or medium demands. Despite this difference, our study illustrates that challenge and the neutral state do not differently influence the Internet search process when they are compared to threat. Probably, in particular the feeling to be able or unable to deal with demands is relevant for Internet search behavior, but not the very level of demands. These results may be relevant for future studies on the influence of threat on Internet search.

Second, the present study used experimental procedures and materials which resembled real Internet searches but simultaneously provided high experimental control. Thus, we could precisely monitor spontaneous and realistic searching behavior. Moreover, with our materials, we could assess the whole Internet search process, starting with the link selection and ending with the recall of information from the Internet search. Third, we used a strong manipulation. It produced exactly the pattern of results on the manipulation check which is predicted by theory (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996). Therefore, we can be confident that the effects obtained in the present study were driven by the manipulation.

Apart from its strengths, the current study has also limitations. First, for ethical reasons, we did not manipulate threat in the health domain. Although the manipulation was quite clear and strong, we might have obtained stronger effects if the manipulation had referred to the same domain as the searching task. For students, for example, exam preparation may be a suitable and ethically unproblematic domain which might result in stronger effects and which could be addressed in future research. On the other hand, the topic of living organ donation is an adequate example of a health-related topic which may increasingly be searched for (Fox, 2011; Fox & Duggan, 2013; Morahan-Martin, 2004). Therefore, we used it in the present study and decided for an incidental manipulation of threat.

Second, although the materials were realistic and allowed for close monitoring, they were nevertheless artificial because we wanted to ensure the internal validity of the study. So, all links were related to the topic of living organ donation. There were, for example, no links to other topics related to the search topic (e.g., donation in general), as often happens during Internet search. The information on the webpages was only plain text without, for instance, additional comments, pictures, or advertisements which are otherwise often presented together with textual information. Therefore, future research could, firstly, investigate whether such effects of threat on the Internet search process also occur for more externally valid materials. One could, for example, program a huge and extensive hypertext document for one topic that allows for the assessment of even more realistic searching behavior. At the same time, such research would have to take close care that the search behavior can precisely be monitored so that the usual disadvantages of externally valid studies are not a problem (cf. Greving et al., 2015, Study 1). Secondly, future research could investigate not only the Internet search process. Searching the Internet for information often implies that a decision needs to be made (e.g., Fox & Duggan, 2013; Fox & Jones, 2009; Lo & Parham, 2010; see also Becker et al., 2018). Therefore, future research could also address the question whether the preference for positive information under threat also applies to actual decision making resulting from Internet searches.

Implications for the Health Domain

The current findings have important implications for the Internet as information source. That is because Internet searches are increasingly conducted in the health domain (Fox, 2011; Fox & Duggan, 2013; Morahan-Martin, 2004; see also Ginsberg et al., 2009). Internet portal administrators, health-threatened patients, and medical experts, they all need to be aware of the preference for positive information under threat. In particular, Internet portal administrators need to know that providing balanced health information may not guarantee appropriate information processing by health-threatened individuals. These individuals may need more assistance to be able to collect information in a balanced way. For example, online communication with medical experts could help them process online information more appropriately. Checklists could also be helpful with Internet search. Health-threatened individuals for their part may need to be aware of the ambivalent consequences of their Internet search. On the one hand, their preference for positive information may provide them with quite relevant emotional support (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) in dealing with the health-related threat (e.g., Becker et al., 2018; Sassenberg & Greving, 2016). On the other hand, due to preferring positive information, health-threatened individuals may run the risk to make wrong or suboptimal decisions based on their Internet search (Fox & Duggan, 2013; Fox & Jones, 2009; Lo & Parham, 2010; Murray et al., 2003). Such decisions could in turn have negative effects for their health. Finally, medical experts should be aware of this potential risk and may need to take into account that their patients may already have collected information using the Internet. The experts should, for example, invest some time and effort to explain online information to their patients when those come to see them. Giving support by explaining and interpreting online information could also help foster their relationship with the patients.

Conclusion

In sum, the current study illustrates that threatened individuals prefer positive information during the process of Internet search and counter-regulate their negative affective state. It demonstrates that threatened individuals allocate more attention to positive information (i.e., they select more positive links and scan positive webpages longer) and, thereby, also recall more positive information than non-threatened individuals. Thus, affective states such as threat influence the Internet search process and should be taken more into account in future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Soraja Fejzuli, Leona Goebbels, Marie Mückstein, Franziska Rück, Lara Scatturin, Kerstin Treiber, and Marc Werth for their help with data collection and data coding, and Philipp Weber and Stephan Wenninger for their help with programming the information search task. They would also like to kindly thank Margarete Ocker for proofreading the manuscript.

Notes

- This study investigated the influence of deviant group behavior on exclusion and leaving intentions of the group members. In this study, participants solved anagrams together with other (supposed) group members and then also interacted with them. After that, identity subversion, experienced control, and exclusion and leaving intentions were assessed.

- These two contrasts were consistent with the two rules of contrast codes, namely, that (1) the sum of the contrast coefficients within each contrast code should be zero and (2) the sum of the products of each pair of contrast codes should be zero:

Focal contrast: threat = 2, neutral = -1, challenge = -1: 2 – 1 – 1 = 0

Residual contrast: threat = 0, neutral = -1, challenge = 1: 0 – 1 + 1 = 0 2*0 + (-1)*(-1) + (-1)*1 = 0 + 1 – 1 = 0

- When the two dependent variables positive bias in link selection and positive bias in webpage scanning were collapsed in a mixed ANOVA to form an indicator of positive bias in attention, we obtained the same result. That is, the mixed ANOVA with affective state (threat vs. neutral vs. challenge) as between-subjects factor and positive bias in attention (link selection vs. webpage scanning) as within-subjects factor revealed a main effect for affective state, F (2, 111) = 3.09, p = .049, ηp2 = .053, but no other main effect, F (1, 111) = 0.39, p = .535, or interaction effect, F (2, 111) = 0.01, p = .992.

Appendix

Figure A1. Presented SERP in the information search task containing 4 neutral links, 6 positive links, and 6 negative links.

Table A1. English Translation of the SERP in the Information Search Task.

|

What is living organ donation? Organ donation, also known as living organ donation, means… |

Organ donors under psychological stress Those in the environment of the person concerned… |

Better quality of organs and higher therapy compliance Proper functioning of transplanted donated living organs is… |

Low metabolism after organ donation Moreover, it is unclear whether and how well metabolism is functioning… |

|

High physical and psychological risk Even though organ transplantations are in principal routine operations… |

Organ donors’ quality of life is higher Recent research on the psychosocial consequences of organ donation… |

Transplantation law Since 1997, the transplantation law has covered all issues… |

Children can grow up untroubled For example, spouses or partners often… |

|

Couples are more satisfied with their relationship In a new study, scientists of the University of Zurich investigated… |

Organ donation committee If a person decides to donate an organ… |

Help by donating a kidney and live on happily Through a living kidney donation, many severely ill patients can be… |

Severe pain after operation Annually, around 250.000 people register to the German Bone Marrow Donation registry |

|

Long hospital stay and long inability to work Regarding the hospital stay for organ donation… |

Living organ donation gives a new life Yet, living organ donation is a means to give individuals a second life… |

High financial costs Possibilities for organ donation have increased… |

History of living organ donation The history of organ donation and organ transplantation… |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2018 Hannah Greving, Kai Sassenberg