The Tacit Dimension of Parental Mediation

Vol.11,No.3(2017)

Special issue: Young Children’s Use of Digital Media and Parental Mediation

Studies into the way parents mediate their children’s (digital) media use are challenging. A reason for this is that parents are not always aware of what they do and why, as their choices do not necessarily involve rational decision-making. In the present study we adopted the notion of “tacit knowledge” (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Polanyi, 1966) to explore how and why parents of young children mediate digital media use. In-depth interviews were conducted with 24 Dutch parents from 15 families who were selected to represent a range of socioeconomic backgrounds and different family compositions. Through qualitative analysis we first distinguished three mediation styles of “regulation”, “guidance” and “space”. Furthermore, we revealed seven values that drive parental mediation: three core values of “balance”, “freedom” and “protection” that are foundational in the sense that they explain why parents mediate; three orientational values of “qualification”, “Bildung” and “health/fitness” that explain to which end parents mediate; and one additional value of “flexibility” that accounts for parents’ exception-making. Finally, we showed that the most important emotions associated with these values were anger and disapproval (with balance and protection) and love and joy (with orientational values); fear was mentioned occasionally (in relation to protection).

Parental mediation; young children; digital media; emotions; values; tacit knowledge; qualitative research

Claudia van Kruistum

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

Claudia van Kruistum, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Educational and Family Studies of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and a member of LEARN! Research Institute. Her research concerns children’s and adolescents’ literacy practices in- and outside of school, with a focus on new literacies. She is a member of the COST action the Digital literacy and multimodal practices of young children (DigiLitEY).

Roel van Steensel

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

Roel van Steensel, PhD, is a professor at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam with a chair in reading behavior. He also works as an assistant professor at the Department of Psychology, Education, and Child Studies at the Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam. His research interests include reading motivation and the effects of family literacy programs on children’s literacy skills. He is a member of the DigiLitEY COST action.

Akkerman, S., Admiraal, W., Brekelmans, M., & Oos, H. (2006). Auditing quality of research in social sciences. Quality & Quantity, 42, 257-274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-006-9044-4

Boeije, H. (2010). Analysis in qualitative research. Los Angeles: Sage.

Bucx, F. (Ed.). (2011). Gezinsrapport 2011: Een portret van het gezinsleven in Nederland [Family report 2011: A portrait of family life in the Netherlands]. The Hague: The Netherlands Institute for Social Research.

Chaudron, S. (2015). Young children (0–8) and digital technology. A qualitative exploratory study across seven countries. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrieved from http://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC93239

Clark, L.S. (2011). Parental mediation theory for the digital age. Communication Theory, 21, 323-343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2011.01391.x

Danner, H. (1994). ‘Bildung’: A basic term of German education. Retrieved from http://www.helmut- danner.info/pdfs/German_term_Bildung.pdf

Eastin, M., Greenberg, B. S., & Hofschire, L. (2006). Parenting the Internet. Journal of Communication, 56, 486–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00297.x

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A.L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85, 551– 575. https://doi.org/10.1086/227049

James, W. (1884). What is an emotion? Mind, 9, 188-205. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/2246769

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge Universiy Press.

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E.J. (2008). Parental mediation of children's Internet use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52, 581-599. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150802437396

Mascheroni, G. (2014). Parenting the mobile internet in Italian households: Parents' and children's discourses. Journal of Children and Media, 8, 440-456. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2013.830978

Nikken, P., & Jansz, J. (2013). Developing scales to measure parental mediation of young children's internet use. Learning, Media and Technology, 39, 250-266. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2013.782038

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nussbaum, M. (2004). Emotions as judgements of value and importance. In R. C. Solomon (Ed.), Thinking about feeling (pp. 183-213). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Paavola, S., Lipponen, L., & Hakkarainen, K. (2004). Models of innovative knowledge communities and three metaphors of learning. Review of Educational Research, 74, 557-576. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074004557

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Coyne, S. M., Fraser, A. M., Dyer, W. J., & Yorgason, J. B. (2012). Parents and adolescents growing up in the digital age: Latent growth curve analysis of proactive media monitoring. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 1153–1165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.03.005

Polanyi, M. (1966). The tacit dimension. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Shaver, P., Schwartz, J., Kirson, D., & O'Connor, C. (2001). Emotion knowledge: Further exploration of a prototype approach. In W.G. Parrott (Ed.), Emotions in social psychology: Essential readings (pp. 26-56). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press.

Solomon, R. C. (2004). Emotions, thoughts, and feelings: Emotions as engagements with the world. In R. C. Solomon (Ed.), Thinking about feeling (pp. 76-88). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van der Voort, T. H. A., Nikken, P., & van Lil, J. E. (1992). Determinants of parental guidance of children’s television viewing: A Dutch replication study. Journal of Broadcasting &Electronic Media, 36, 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838159209364154

Valkenburg, P. M., Krcmar, M., Peeters, A. L., & Marseille, N. M. (1999). Developing a scale to assess three styles of television mediation: “Instructive mediation,” “restrictive mediation” and “social coviewing.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 43, 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838159909364474

Zaman, B., Nouwen, M., Vanattenhoven, J., De Ferrerre, E., & Van Looy, J. (2016). A qualitative inquiry into the contextualized parental mediation practices of young children’s digital media use at Home. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 60, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2015.1127240

Editorial Record:

First submission received:

April 25, 2017

Revisions received:

July 10, 2017

October 2, 2017

October 24, 2017

Accepted for publication:

October 30, 2017

Edited by:

Bieke Zaman

Charles Mifsud

Introduction

A rich tradition exists of research into the ways parents manage and regulate their children’s experiences with media. Several scholars have translated insights from studies focused on parental mediation of children’s television use to the emerging research field of digital media. In earlier studies on television use three common strategies have been identified for parents to adopt, namely to restrict use, to explain content and express opinions about it, and to watch television together with their children (Valkenburg, Krcmar, Peeters, & Marseille, 1999; van der Voort, Nikken, & van Lil, 1992). These three strategies are echoed in more recent studies into digital media and findings suggest that parents adopt roughly the same strategies to meet the new challenges posed by the internet (Eastin, Greenberg, & Hofschire, 2006; Livingstone & Helsper, 2008; Nikken & Jansz, 2013).

Making a distinction between different mediation strategies (or styles) is potentially useful, as it enables researchers to establish which parental practices minimize the risks and maximize the benefits associated with children’s digital media use. However, straightforward models and quantitative, large-scale studies can also obscure the dynamic and often paradoxical nature of parental mediation. For example, parents who disapprove of digital media use may at the same time believe they cannot counter the digital media advent, resulting in a mixture of restrictive and permissive parenting strategies. Clark (2011) explains such seemingly contradictory behaviors by putting forward that researchers tend to focus on parenting decisions as rational choices, whereas parents’ decision making is mostly emotionally charged. Specifically, it involves their feelings about what it means to be a “good parent”. So if we want to understand how parents mediate their children’s digital media use, we need to address the complexity involved in child-rearing.

The aim of the present article is to examine which ideas, feelings and intuitions explain if and how parents establish rules and guidelines for young children’s use of digital media. None of these three terms in themselves – ideas, feelings or intuitions – captures the spirit of the emotionally laden perspectives Clark (2011) refers to, as it is neither pure feeling nor pure rational thought that determines parents’ decision making. In order to explore both the thinking and the feeling aspect of parental mediation without assuming a sharp boundary between them, we draw upon the notion of “tacit knowledge” (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Polanyi, 1966) to refer to beliefs parents have that convey emotions and values, beliefs they are not always aware of but committed to nonetheless.

In the next sections we will discuss more thoroughly why we need to pay attention to emotions, understood as judgmements of value, and how the concept of tacit knowledge might provide a fruitful theoretical perspective. Then results will be presented of in-depth interviews that were conducted with 24 parents from 15 families to analyze their tacit knowledge of how and why they mediate the digital media use of their young children (aged six or seven). With the discussion of these findings we hope to enrich existing theories on mediation. Ultimately, our aim is to develop an elaborate understanding of what parents do that can be used in future qualitative studies, for instance in cross-cultural comparisons, to further unravel why parents mediate the way they do.

Emotions as Judgements of Value

In Western thinking a dichotomy prevails between thinking and feeling (as argued by Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Nussbaum, 2004; Solomon, 2004). Emotions such as anger, fear and infatuation are typically assumed to be physiological responses that we do not choose to have; they are instantaneous and instinctual. Thoughts, on the contrary, are intelligent and enable reflection, distancing and, consequently, control over our behaviors. From such a perspective on thinking and feeling, a view often traced back to the psychologist James (1884), emotions are suspect. For instance, when parents are controlling out of fear of something happening to their child or lenient because of feelings of guilt after a divorce, society at large urges them to use their brains instead of going with their gut feeling.

Some scholars have challenged the sharp divide between emotion and rationality. Solomon (2004), for instance, has been arguing for several decades that there is an intelligent component to emotions, thus questioning the established notion that they render us passive. Enduring passions such as love and righteous indignation are not spontaneous and individual creations, he claims, but they develop within relations between people; in other words, they are shared and cultivated. Even the most primitive of emotions, fear, is more often learned than not. These considerations lead Solomon (2004) to conclude that emotions are a type of judgment that contains essential insights. Nussbaum (2004) similarly argues that emotions are “judgements about important things” (p. 184); they are concerned with value and often embody very complex beliefs.

It is precisely this dimension of emotions that has been neglected in research on parental mediation, Clark (2011) argues. She claims that the study of emotions in media research mostly draws upon the psychology rather than the sociology of emotions. From a psychological perspective, emotions are the type of physiological phenomena discussed previously: they are the province of individuals and concern supposedly instantaneous and instinctual responses such as fear and joy. From a sociological perspective, Clark (2011) explains on the basis of ideas developed by Hochschild (1979), emotions are deeply social. This implies that parents’ emotions reflect (culturally) transmitted values regarding good parenting. Emotions parents might have when they deal with their children’s media use are pride in children’s ability to manage risks on their own or anxiety about the unknown in the digital realm. These emotions are related to valuing autonomy and protection respectively as parenting goals.

Emotion and Parental Mediation

We believe that a meaningful investigation of why parents adopt certain mediation strategies necessitates a view on emotions that counters the traditional Western dichotomy between thinking and feeling and takes emotions as legitimate judgements of value. In some studies on parental mediation conducted from a sociocultural perspective such a view on emotions has been present implicitly.

Mascheroni (2014), for instance, explored how parents of children aged 10 to 13 legitimized the regulation of smartphone use, starting from the assumption that a new medium gives rise to controversy and thus occasions emotions of hope and fear. The study indeed shows that some parents, particularly mothers, were fearful of addiction and isolation, expressing concerns about children being exposed to inappropriate content and contact. Fathers, however, were more enthusiastic about new devices and considered keeping pace with technological change an ingredient of good parenting. Our understanding of these findings is that fathers and mothers embrace different emotions that reflect distinct values, causing mothers to be more inclined to restrict children’s access to smartphones.

Zaman, Nouwen, Vanattenhoven, De Ferrerre, and Van Looy (2016) included parental attidues in their research on contextual factors that shape the digital media engagement of children aged 3 to 9. In the study three types of what the authors label attitudes (but we would call values) are distinguished, namely the desire to encourage balanced life, to protect against inappropriate content and to invest in skills (social skills, digital media literacy and cognitive development). For instance, when parents used technical safety measures or discussed media use with their child, a reason could be that they were concerned about exposure to inappropriate content (which we, again, understand as an emotion that reflects a value).

In both of these studies parents seemed to rely on emotions as judgements of value to legitimize their mediation strategies. We argue that this dimension has been neglected or, at the least, underemphasized by empirical researchers and that it might be fruitful to explore emotions parents have more directly. A study of emotions can account for parental mediation as a decision-making process that does not involve conscious and rational choice. Thus, it leaves room for ambivalence among parents towards digital media (Mascheroni, 2014), resulting in what otherwise seems to be inconsistency in mediation practices (Zaman et al., 2016). In the next section we introduce a theoretical framework that allows us to study parents’ emotions regarding mediation as a form of “tacit knowledge” that can be externalized.

Tacit Knowledge

In 1966 Polanyi’s philosophical work The Tacit Dimension was published, which revolves around the basic insight that “we can know more than we can tell” (p. 4). He calls this “tacit knowledge” and proposes that it is a central feature of our knowledge of the world, even though it is hard to formalize and put into exact words. Polanyi’s book has inspired others to build upon and expand his work, particularly in the field of organization studies. Most notably, Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) developed a model to study how knowledge-creation takes place in Japanese companies. They explain that fundamental differences exist between Japanese and Western views on what “knowledge” is and how it comes about. According to the Western view knowledge is explicit, formal, and systematic; it is considered objective and often loosely referred to as “data” and “information”; and, consequently, it can be easily communicated and shared. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) describe a different view that encapsulates the more hybrid approach to emotion and cognition discussed in the previous sections: tacit knowledge is essential yet highly personal, hard to formalize, and deeply rooted in the emotions and values an individual embraces.

While Polanyi (1966) emphasizes that formalization seeks “the kind of lucidity which destroys its subject matter” (p. 25), Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) uphold that it is possible to make tacit knowledge explicit, namely through a process they call “externalization”. To achieve this a person’s individual knowledge has to be shared with others, for instance through a group discussion or brainstorm session. Tacit knowledge cannot be transferred in a straightforward fashion though: when people attempt to externalize their tacit knowledge ambiguities, redundancies and inconsistencies may arise. However, these are not seen as hindrances but as opportunities, as they encourage further dialogue and may open up new avenues. Specifically, figurative language (e.g., metaphor and analogy) can prove useful to express what is intuitively understood but hard to articulate, as it relies on imagery and symbolism.

Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) model of knowledge-creation has (to our knowledge) not been used in relation to parental mediation before, but commonalities exist with situated learning theory. Situated learning theory criticizes the view that human cognition relies on explicit propositional knowledge and instead upholds that learning occurs through a process of participating in the sociocultural practices of a community (Lave & Wenger, 1991). Clark (2011) argues that this perspective can be used to study the situatedness of parental mediation, such as how media might be experienced differently in diffent families and how families negotiate the changing needs of children. In situated learning theory tacit knowledge is an important concept, especially the notion of know-how (Paavola, Lipponen, & Hakkarainen, 2004). Differences with the knowledge-creation model consist in the emphasis Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) place on (1) tacit knowledge as a form of knowing that relies on subjective insights such as emotions and values, and (2) modes of conversion beween tacit and explicit knowledge.

We believe the latter two components make the model by Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) suitable for studying parental knowledge. Entering with parents into a dialogue requires them to articulate, attend to and deliberate regarding their reasons. This may be difficult for them, as a family is like an organization in the sense that a shared understanding might arise from spending time together. Because of this, parents might not always be aware of what they do or why. The dialogue can therefore involve ambiguities, redundancies, metaphors, analogies and even contradictions, which can be used by the interviewer to encourage further reflection. When parents are interviewed together and can respond to each other, more conflict may arise. All of this is assumed to facilitate the transformation of tacit knowledge – what parents feel and value – to explicit knowledge.

The Present Study

In the next sections we will describe an in-depth, qualitative study we conducted to explore the following questions: (1) how do parents of young children (aged six or seven) mediate their children’s digital media use, and (2) which reasons do they have for engaging in certain types of mediation practices? Posing the first question was necessary for answering the second, which is our prime focus. We conceived of parents’ reasons for adopting a mediation practice as “tacit knowledge”; the method section describes our procedure for eliciting parents’ tacit knowledge.

We chose to incorporate parents of young children in our study because children use digital media at an increasingly younger age due to new technologies such as tablets and smart toys. At the same time, when children are at the age of six or seven they receive formal education and start to read and write, which provides them with more independence and allows them to enter into activities such as searching online. We were particularly interested in the extent to which parents were aware of risks and opportunities during this phase of children’s development and whether the mediation practices they adopted were guided by hope, fear or other emotions.

Several studies have been conducted already into the first research question (e.g., Eastin et al., 2006; Livingstone & Helsper, 2008; Nikken & Jansz, 2013). From these large-scale, survey-based studies we know that parents adopt the following strategies: they enforce rules and limit or control children’s media usage (restrictive mediation); they explain media content in order to provide instructional guidance or share their opinions in order to express (dis)approval (active mediation); they watch or use media together with their children, often driven by a common interest, which may lead to discussions (co-use); they supervise their children’s media use and do not intervene as long as this is not deemed necessary (monitoring). These mediation practices correspond to three general strategies distinguished in the wider parenting literature: avoiding exposure to negative content (cocooning); engaging in discussions and offering strategies to deal with or avoid questionable content (prearming); and actively choosing to do nothing as long as the child is not negatively impacted (deference) (Padilla-Walker, Coyne, Fraser, Dyer, & Yorgason, 2012). A relatively new mediation method due to opportunities created by new technologies is to employ technical measures (Nikken & Jansz, 2013), which may fit within different strategies such as monitoring or restriction through filtering . We expected to find in our sample a relatively high reliance on restrictive mediation and monitoring, considering that parents tend to implement more rules and supervision for younger children (Livingstone & Helsper, 2008).

Method

Research Context

The data for the present study were collected between September–December 2015 as part of the second round of data gathering for the Young Children (0-8) and Digital Technology project coordinated by the European Union’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) (Chaudron, 2015). The research was conducted in and around the two largest cities in The Netherlands in urban as well as rural regions.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Scientific and Ethical Review Board (VCWE) of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Prior to the visit to their homes, parents who had agreed to participate were informed about the purpose and the procedures of the research by telephone. After this phone call a consent form with further information was sent to them, provided by the JRC and translated in Dutch. At the start of the visit, the researchers discussed the main points in the consent form with the parents, answered questions and asked parents to sign the form. The researchers emphasized that participation was voluntary and that, at any given time, the visit could be terminated. None of the family members objected to the procedures, with the exception of one parent who requested only audio and no video recordings be made. All data obtained during the study were carefully and anonymously processed and saved. The names used in the present article are pseudonyms.

Participants

The main goal of the sampling procedure was, in accordance with guidelines from the larger research project, to select a small and maximally diverse sample of families with at least one child aged six or seven (typically in grade 2) who used digital media. We chose for maximal diversity in terms of SES and family composition as a sampling criterion in order to document a variety of mediation practices within different conditions and to identify common patterns that cut across these variations.

Ten schools with children with a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds were asked to distribute a (paper and/or online) questionnaire about children’s out-of-school media environments. As one aim of the questionnaire was to select participants for the present study, parents were asked to provide information regarding SES and family composition and to indicate whether they would be willing to participate in a follow-up interview.

Twenty-four parents (nine fathers, 15 mothers) from 15 families participated in the study (see Appendix A for a full overview). They represented a range of socioeconomic backgrounds, defined in terms of educational level obtained: 11 parents (four fathers, seven mothers) had received higher professional or university education and 13 parents (five fathers, eight mothers) had received secondary education at the most. Four single parents (all mothers) participated in the study and two parents (in both cases fathers) were not present during the visit for unspecified reasons. The mean age of the parents was 41 years (fathers 46 years, mothers 38 years). In most families two children were present: in seven of these families the six/seven-year-old had one younger sibling and in three families one older sibling. In three families the child had no siblings, in one family two siblings, and in one family three siblings.

Interview Procedure

In-depth interviews were conducted at the families’ homes by the first author. Visits generally lasted one-and-a-half hour and in no case exceeded two hours. After an introduction and briefing, both parents were interviewed simultaneously (naturally with the exception of the single parents). We wanted to obtain the perspective of both caretakers and also believed on the basis of the methods employed by Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) that this dynamic would aid the process of externalization. The interview with both parents was structured around the following activities (see Appendix B for the materials used):

- sorting 30 cards depicting a variety of activities, toys and devices into three piles of very fun, fun and not so fun for the six/seven-year-old child;

- selecting from a set of 30 word cards those words parents associated with the child’s digital media use;

- writing down on a blanc page tips parents might have for other parents concerning their children’s digital media use.

The first activity was a prompt for discussing how parents mediated their children’s media use (Research Question 1): after establishing which were the children’s favorite media activities, the interviewer was required to ask parents which mediation practices they adopted (although this question appeared to be mostly unnecessary, as parents generally discussed their mediation practices automatically during the sorting task). The second and third activity prompted parents to discuss why they adopted a mediation practice, which emotions were involved and what parents found most important (Research Question 2).

These activities were designed with the aim of encouraging parents to reflect on reasons without steering them in a particular direction. For instance, during the second activity parents were presented cards with words such as “educational” and “addictive”. Then the interviewer asked as much as possible open-ended questions such as “Could you tell me more about that?” and “How so?” to stimulate parents to associate freely, thus revealing their tacit knowledge.

Analysis

Procedure. The interviews were transcribed by research assistants and then coded by the first author according to the principles of Grounded Theory, a qualitative method through which theory is developed inductively from a corpus of data (Boeije, 2010; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This method requires the researcher to first read through the data and create tentative labels (open coding); to then organize the open codes into central categories and to describe the relationships between these categories (axial coding); and finally to identify a core category, to relate it systematically to other categories, and to further theory development by exploring how it contributes to existing insights (selective coding). Existing theoretical concepts function as “sensitizing concepts” with broad and general descriptions that inform the analysis and are gradually clarified.

As the primary aim of the present study was to explore the reasons parents have for the way they mediate their children’s digital media use, the first author first highlighted fragments in the transcripts pertaining to mediation, distinguishing . In this process tentative codes were developed for five transcripts and a so-called audit trail (Akkerman, Admiraal, Brekelmans, & Oost, 2006) was prepared in order to document the analysis procedure for the second author. The first and second author discussed the codes and some adjustments were made. Next, both authors coded three additional transcripts (20%) independently and inter-rater reliability was calculated (κ=.80). As agreement was strong, the authors resolved disagreements and the first author coded the remaining seven transcripts. Saturation was reached after coding 13 interviews, meaning that from that point onward no new codes were introduced.

Coding scheme. During the process of coding three main categories of parental mediation were identified: mediation practices (related to how parents mediated), and values and emotions (related to why parents mediated). With regard to these three categories parents regularly relied on figurative language, as we expected on the basis of the model by Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995). For instance, they used analogies but also colorful anecdotes that allowed them to illustrate what they did and why. We see this as an indication that parents were tapping into their tacit knowledge and were going through a process of externalization.

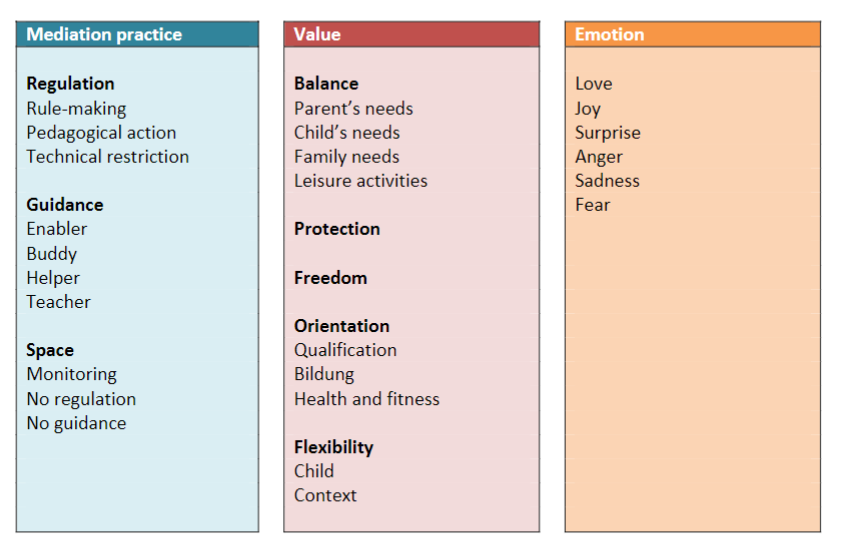

The final coding scheme is presented in Figure 1. For the categorization into three types of mediation practices the studies by Padilla-Walker et al. (2012) and Zaman et al. (2016) provided sensitizing concepts and the categories “pedagogical action”, “enabler” and “teacher” were added. “Balance”, “protection” and several “orientational values” have also been distinguished in the study by Zaman et al. (2016) (although they are called “internal contextual factors” and “attitudes” there). Emotions of parents were classified with the help of the six basic emotions distinguished by love/affinity, joy/contentment/exhilaration, surprise/distraction, anger/disgust/disapproval, sadness/sorrow and fear/fright. We departed from the words used by parents literally. Sometimes the emotion was clear, as when a parent spoke of anger explicitly: . Otherwise, we relied on the three-component structure by Shaver et al. (2011) depicting tertiary, secondary and primary emotions. For instance, when a parent said “I always become a bit grumpy because of it myself, the lounging about” the emotion was initially classified as grumpiness and subsequently as irritation and anger/disgust/disapproval.

Figure 1. Coding scheme.

Results

A Model of Parental Mediation

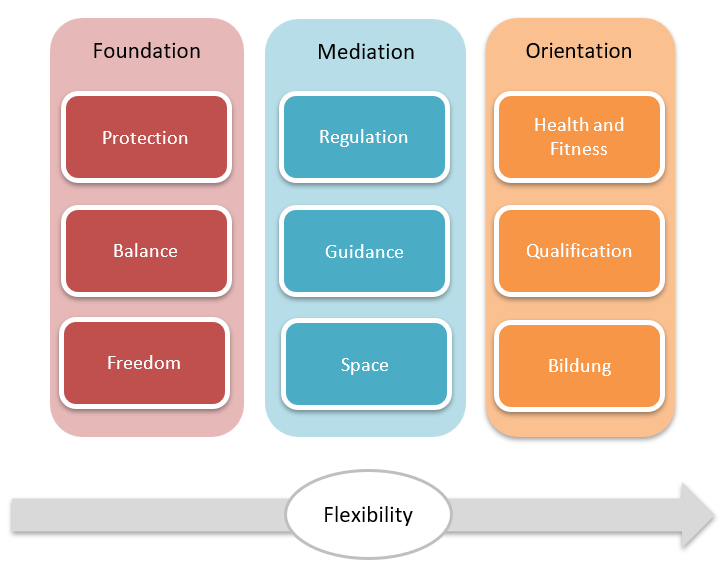

Starting from the coding scheme presented in the method section, we construed a model that explains why, how and to which end parents mediated their child’s media behavior. The model (depicted in Figure 2) first distinguishes practices from the values that drive these practices. Second, it distinguishes three broad categories of values. The first is labelled “foundation values”: these values represent basic stances towards children’s media use. The second is labelled “orientational values”: these reflect to which end parents mediate their children’s media use, that is, what the desired outcomes for children are. The third category of “flexibility” was added to reflect the weight parents attach to adapting their mediation practices to individual children and circumstances.

Figure 2. Model showing why, how and whereto parents mediate children’s digital media use.

Mediation practices. In the model three mediation practices are distinguished that more or less correspond to the three parenting styles discussed in the introduction: “regulation” (cocooning), “guidance” (prearming) and “space” (deference). We chose for the term “regulation” rather than the commonly used label “restriction” because the practices parents reported were not always aimed at restricting media use. For instance, Josephita (Family 4) obliged her daughter Lilou to take her phone with her when she went outdoors, “so she knows when she has to come home.” The most commonly adopted rules pertained to when and how long a child was permitted to use a device, although such rules were regularly implicit or vague: some parents clocked the time whereas others relied on gut feeling. Besides rule-making, technical restrictions were also subsumed under the category of regulatory practices, but the parents in our sample scarcely made use of them. For other parental practices aimed at regulation we distinguished a third category of “pedagogical actions”. In most of these cases parents made an on-the-spot decision to restrict media use by telling a child to stop using a digital medium, instructing a child to do something else, or saying no to a request to use a device. In other cases parents kept a device out of the child’s reach.

Guidance refers to a practice in which parents supported children’s media use and, contrary to regulation, did not exert control or did so to a lesser degree. We distinguished four roles a parent could adopt: they could act as an “enabler” of media use (e.g., by buying a device or handing one down), a “buddy” (i.e., by using a device together with the child), a “helper” (e.g., by helping out in case of technical difficulties), and a “teacher” (e.g., by adopting active mediation). In previous studies the focus has been mostly on the first three roles of the parent and one specific interpretation of parent-as-teacher, namely to talk about media content. By approximately half of the families participating in the present study other teaching practices were mentioned, namely to encourage the use of educational apps, to teach the child search strategies, and to provide guidance while using digital media for informational purposes such as learning a foreign language. However, such practices occurred only occasionally according to the parents. Josephita (Family 4), for instance, shared an anecdote about a game she had recently played with her daughter Inci in which she functioned as a teacher:

And then you have to [come up with] names of boys, names of girls, names of animals, names of countries, names of fruits and vegetables and those kinds of things. And then I go get my telephone and we look it up. Does it exist? What kinds of fruit are there with a P? What kinds of fruit are there with an R? So it is very useful and educational and informative.

We used the label “space” to denote the practice of doing nothing as long as the child was not negatively impacted. In approximately two-third of the families parents indicated to have no rules, no strict rules or few rules. These parents allowed their child to use at least one device independently, to select and install apps, and/or to regulate their own behavior. For example, when the interviewer asked parents whether they had any rules, Patrick (Family 3) answered: “No, not very strict ones. It is more so the case that every now and then I just pull the iPad away, when I feel enough is enough.” The tablet was the device children most often used on their own. The majority of parents did monitor media use by keeping an eye on what the child did. Some parents also checked afterwards which information the child had sought, whom the child had contacted, or which apps had been installed. Jan and Marlies (Family 11) recounted the time their son Rik had been acting secretively while using the tablet, which incited them to check afterwards what he had been doing. They discovered he had been searching for a girl band “dancing naked” and looking at pornographic pictures. Later they confronted Rik, talked to him about their finding and explained why they considered this content inappropriate.

Foundational values. Foundational values that explain why parents adopted a mediation practice were mentioned in each interview, the one most frequently discussed being balance. Parents found balance between digital media use and other leisure time activities important, such as playing outdoors. For example, when asked to write down tips for other parents, Arjen and Daphne (Family 6) stressed the need to limit digital media use and promote “real” playing:

Arjen: Let them use it but limit it, yeah.

Daphne: So they can be a child, indeed. Also, real playing, because that is important for the rest of their development, everything… cognitive, motor skills. They also need to just ride their bike and play outdoors.

Parents also weighed between the different needs within a family: parental needs (e.g., their desire to have “me” time), needs of the individual child (e.g., to give the child attention and show an interest in the child’s affinities), and family needs (e.g., to conform to daily routines, to be mindful of finances, and to do things together as a family). The second most often mentioned foundational value was protection, for instance protection from harmful content and sensory-overstimulation. Approximately half of the parents mentioned freedom as a value, specifically not intervening as long as there is no perceived need to do so. Simone (Family 10) felt strongly about this: “Let everyone do their own thing. Of course it is unhealthy if a child does not play outdoors at all, but sometimes you have to let things be.”

Orientational values. All parents discussed orientational values in the interviews, meaning to which end they adopted a mediation practice. Most of these goals pertained to qualification: parents found an activity important because it was educational or because cognitive, social or linguistic skills were promoted. In a number of families the wider development of the child as an autonomous, active, creative and/or imaginative person was mentioned as an aim. The label “Bildung” here is ours and refers to the traditionally German ideal of self-cultivation (Danner, 1994). For instance, Piet (Family 1) explained how his goal was to incite in his children a broad interest, not only in digital media but also in craft. When speaking about this he referred to his own childhood and his father allowing him to use the saw under supervision when he was ten or eleven years old: “The fact that you are given responsibility, that you were allowed to do that, you know. That in itself is important. And that instills a certain confidence.” In line with this, Katja (Family 12) called handing down devices to her children a form of empowerment. Some parents furthermore mentioned health and fitness as an orientational value, specifically the promotion of exercise and/or motor skills.

Flexibility. During the interviews parents regularly indicated valuing flexibility and explained how they attuned their mediation practices to a certain context with particular social norms and expectations. For instance, in families in which usage of parents’ devices was off-limits an exception could be made during a formal dinner in order to keep the child quiet.

Parents also explained how they attuned their mediation practices to the child’s needs and abilities by being sensitive as to whether a child accepted a rule, taking a child’s request seriously, acknowledging differences between siblings, or by taking into account the developmental phase the child was in. For instance, Piet and Annejet (Family 1) as a rule did not pay for apps, but made an exception because their son Ingmar was no longer challenged by the demo version of the game he enjoyed playing and he badly wanted the full version. Monica (Family 14) is another good example. She did not allow her son Colin to use the tablet in the evenings because some games contained scary elements, but she regularly made exceptions:

And yeah, he started dreaming about that sometimes. So then I said, we don’t do it anymore in the evenings, just during the day for an hour or so. There are always exceptions. If he has a friend over and the hour has just gone by and he asks: “Can I use the iPad?” Then every now and then I say, well okay.

Emotions and Values

Starting from the assumption that emotions are judgements about value, we established during the analysis which emotions parents expressed when they spoke of how and why they adopted mediation practices. The identification of emotions thus aided the process of identifying values. In this section emotions parents brought up during their conversation are discussed in relation to the values they embraced.

Anger. When parents spoke of their emotions anger, dislike and irritation were mentioned most often. These emotions typically occurred when digital media elicited in children behaviors parents found annoying or unhealthy. Television was mentioned often because parents either had a dislike of cartoons that overstimulated the child (pointing to the value of protection) or because television in general was found annoying because it created unrest and distraction (pointing to the value of balance). Sometimes parents were not in agreement with each other. For instance, Bart (Family 2) enjoyed the television being turned on constantly, which the children also found pleasant, whereas Annemarie preferred a quiet atmosphere:

Annemarie: I dislike watching television.

Bart: I even put one in the bedroom. I enjoy nothing more than turning on that television early in the mornings and then the news.

Annemarie: No, I am taken up by the newspaper and I also prefer the kids quiet when I am reading the newspaper in the mornings. (…)

Bart: Now it is turned off and that is a coincidence. It is mostly turned on.

Annemarie: I don’t mind the image moving but I don’t want to hear someone chattering in the background constantly.

Bart: Television, yes, I always enjoy that so much. Yesterday I was alone with Klaas, pizza and the television on.

Annemarie: Yes.

Bart: Wonderful, always.

Annemarie: But the kids find it cosy.

Not only television but also tablets and smartphones caused dislike and irritation. Parents generally wanted to protect their children from excessive use, passivity, isolation and exposure to inappropriate content. They felt frustrated or even angry when children resisted or when the social environment made protection harder. Annemarie (Family 2), for instance, shared an anecdeote about a visit to the local library that made her angry when she discovered that the children’s department suddenly featured a computer, as it made books less attractive for her son Simon:

And then I was really mad. And then when we were in the car Simon said, also when we were walking towards the car: “Mum, are you mad?” “Yeah , I told you three times to get away from that thing.” But later I thought, well, that was just too hard.

The balancing of different preferences, such as Bart and Annemarie did, was a recurrent theme throughout the interviews. When discussing their dislikes parents in those instances most often explained that they had no affinity with a device (categorized as disapproval). For example, Fatma (Family 9) had a strong dislike of new technology in general and indicated to become angry quickly when her daughter Esra used her phone, of which Esra was very fond: “She wants to look often at the phone. But no longer than half an hour, that is bad for you. So if she grabs the phone, I become angry quickly. She is better off watching tv.” Later Fatma added: “I feel it is a waste of time myself.”

Love and joy. Parents not only spoke of their dislikes but also their likes and preferences. Several parents indicated to be more likely to endorse digital media when they were used by the children for purposes they appreciated, such as physical activity and educational apps and television programs. Parents also regularly explained nonmediated activities gave them a pleasant feeling, in particular regular play. For instance, Monica (Family 14) preferred when her two sons played a game that made them physically active and did not count this as “digital media time”:

So recently I bought Just Dance. And yeah, I really like that because, well, it is just a work-out. They are jumping and dancing. When they come downstairs they are all sweaty, as though you sent them to the gym.

Thus, parents’ discussions of their likes mostly pointed towards the orientational values of qualification, Bildung and healh and fitness. Apart from this, parents frequently mentioned togetherness as something they found nice, such as playing games together. This points to the foundational value of balance with family needs. Monica (Family 14), for example, enjoyed the time she built a virtual farm together with her sons: “Then they came to me with the iPad. And then I said, you have to do this and that. And then we sat together snugly, the three of us, building a farm. So that is nice.”

Fear, sadness and surprise. Sadness was hardly expressed throughout the interviews and surprise was not mentioned explicitly at all. An emotion that did occur – but much less frequently than anger, love and joy – was fear. Speaking from the foundational value of protection, some parents indicated being afraid of harm to their children such as exposure to inappropriate content or excessive usage. Single mum Joke (Family 15), for instance, disliked and distrusted new technology. Because her former husband bought devices for the children she allowed them into the house, albeit reluctantly: “I sometimes have fears that they will end up at the wrong page.” Yet the general sentiment was that digital media use was not something parents were concerned about yet. “This might come when the children grow older,” Philip (Family 8) explained.

Three Family Portraits

To further illustrate the working of the model and the emotions involved in parents’ discussion of their mediation pracices, we end the results section with three family portraits. The three families were selected because their mediation styles stood out: in the first family parents strongly regulated and provided little guidance; in the second family parents hardly regulated but provided some guidance; in the third family parents strongly regulated and provided a lot of guidance.

“We are not allowed to do anything here”. The mediation style of Marco and Sheila from the Heerschop family (Family 13) is characterized by a high level of regulation. Their four children children are only allowed to use digital media during the weekends and for a maximum of half an hour. Sheila keeps track of the time by using an alarm clock: “Why? Well, because they have to share one device among the four of them. So two hours will have gone by once everyone has had their turn. Yes, that will be different in another family.”

The restrictive measures Sheila adopts are mostly aimed at creating a balance between the needs of different family members, taking into account her own lack of affinity with digital media as well. Being strict is something her parents did, as they had six children as well as six or seven foster children. She takes pride in not caving in when her children nag or complain:

“Occasionally when they are pissed off, they will say: ‘We are not allowed to do anything here!’ But I used to say that as well. I was never allowed to do anything and other children were allowed to do whenever whatever at home. That is just your subjective experience, but of course it isn’t true. It is important to establish boundaries. They do rebel, but it is pointless. You are allowed to rebel, you are allowed to protest, you are allowed to express your opinion, but those are our rules, period.”

“There are no agreed upon rules”. The Driessen family (Family 8) forms a stark contrast to the Heerschop family. Philip in particular enables his daughter Felicia’s digital media use: she has several devices of her own, such as a mini laptop and a telephone handed down by her dad. Also present in the home are a tablet, a game console and a streaming device that allows family members to stream movie clips from mobile devices onto the digital television. Philip moreover functions as a buddy to Felicia: he sends messages to her through social media and watches videos with her that they stream onto the television. According to Philip they do not have any rules and hardly regulate Felicia’s digital media use: “There are no agreed upon rules. She doesn’t do it that much and if we feel it is too much, then we will ask her to stop.” Michelle doesn’t mind as long as she can keep an eye on what Felicia is doing. Philip agrees: “You are also near her and you know what she is doing, so it is not something I am particularly worried about.”

Both parents attribute little value to protecting Felicia from harmful effects of digital media, as they believe this is not necessary yet and do not experience fear. Philip does value the development of digital skills and feels he could take on the role of parent-as-teacher more in the future:

You see, and that is a problem, that she considers all digital media at the moment just as fun. And if it isn’t fun, she wants to quit. And that is something she has to learn still. We will need to guide her in this.

“It’s just like riding a bike”. In the Mulder family (Family 5) parents do take on the role of parent-as-teacher. John and Petra place great value on the developmental goals of Bildung, qualification and health and fitness. They wish for their only child Sophie to become a skilled, autonomous, imaginative and healthy digital media user. John has his own vision on how to promote this, which he makes clear by means of an analogy:

It’s just like riding a bike. You start practicing here in the backyard and gradually you move towards the street. And the same applies to digital media: You start with small steps, learn to operate independently, learn that when your parents are present you are somewhat protected from dangers and that in due time you will slowly but surely be set free.

During this stage of Sophie’s development John and Petra value protection most of all and strongly regulate Sophie’s digital media use, partly driven by fear of harmful content but mostly by dislike of excessive use and sensory overload. John finds privacy important and screens the terms and conditions of new apps. He also makes sure only apps are installed he considers beneficial for Sophie. Petra is the one who is more inclined to encourage Sophie to do other things besides using digital media, such as reading a cartoon. She particularly dislikes television cartoons that overstimulate Sophie’s senses. John and Petra both take on the role of teacher, occasionally by explaining to her how to look for information online and more frequently by discussing media content with her. Sophie is a child that is easily frightened and John and Petra are sensitive about this. When a picture was shown on a children’s news program of the three-year-old Syrian boy whose body was washed up on a Turkish beach, they made sure they remained near to talk about it. John:

I was there. I knew that it was tricky. If it were broadcasted then I would be near, then I would at least be able to comment on it. It did make an impression on her, but she mostly felt sorry for the boy.

Discussion

Main Findings

The aim of the present study was to explore how and why parents mediated their young children’s digital media use. We distinguished three mediation styles of regulation, guidance and space that have also been observed in previous studies (Padilla-Walker et al., 2012; Zaman et al., 2016). In order to explicate parents’ reasons we relied on the concept of tacit knowledge (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Polanyi, 1966), referring to emotions as judgements of value. This notion proved useful in revealing seven values that drive parental mediation: three core values of balance, freedom and protection that are foundational in the sense that they explain why parents mediate; three orientational values of qualification, Bildung and health/fitness that explain to which end parents mediate and what desired outcomes are; and an additional value of flexibility that accounts for the importance parent attach to adapting mediation practices to the individual child and the situational context. Furthermore, we showed that anger/disapproval was the most important emotion associated with the foundational values of balance and protection. Love and joy were expressed in relation to orientational values. Fear was mentioned only occasionally and in relation to protection.

We conducted our study with families of children who were six or seven years old because we were interested in the extent to which parents were aware of risks and opportunities during this developmental phase and whether their mediation practices were guided by hope, fear or other emotions. From previous research we know that parents adopt more rules and guidelines for younger children (Livingstone & Helsper, 2008). Yet new technologies such as tablets and smart toys make it easier to use digital media without parental guidance and the onset of formal education in reading and writing further promotes children’s independence. As expected, we found that parents made use of regulatory strategies such as restricting time. The family portrait of the Heerschop Family (Family 13) illustrated a rather extreme focus on regulation, with Sheila using an alarm clock to track the time her four children spent with digital media. However, most parents gave their children space to use digital devices independently, particularly the tablet. Two-third of the parents indicated to have no rules, no strict rules or few rules, similar to Philip and Michelle from the Driessen family (Family 8) in the second portrait. Instead, they tended to monitor media use loosely and did nothing as long as the child was not negatively impacted, a strategy labeled “deference” in the wider parenting literature (Padilla-Walker et al., 2012).

Can the emotions and values that we focused on explain this liberal parenting style? The values parents mentioned largely coincide with the “internal contextual factors” distinguished in the study by Zaman et al. (2016), specifically balance, protection and the promotion of certain skills. The emphasis that the parents in our sample placed on freedom, Bildung and flexibility – values not mentioned in the aforementioned study – forms a tentative explanation for the space they gave their children to explore digital media on their own. To be more precise, they felt children should be able to “do their own thing”, embraced the ideal of self-cultivation, and/or considered it important to be flexible with rules. The latter also partially explains why there is no one-to-one correspondence between a value and a mediation practice. For instance, when a parent who desires to protect the child does not have set rules or makes an exception, this is easily mistaken for irrationality, permissiveness or parenting out of convenience. Instead, it may (but does not necessarily) signal that this parent values flexibility over consistency. From this it does not follow though that giving space is a good thing in itself. The third portrait of the Mulder family (Family 5) shows that more control may be accompanied by a larger degree of involvement and guidance on behalf of the parents. Philip (Family 4) acknowledges this when he states that he could take on the role of parent-as-teacher more to help his daughter use digital media for purposes beyond immediate gratification.

A second way to explain parents giving their young children space is to look at the emotions they expressed – or did not express. In previous research fear featured prominently in parents’ discussions of their children’s media use (Mascheroni, 2014; Zaman et al., 2016). This was much less the case in our study, which does not mean that parents were blind optimists, as anger and disapproval played a large role in why they adopted a mediation practice. For instance, Sheila (Family 13) strongly regulated media use because she had to balance the needs of her four children and her own dislike of digital media. The lack of fear could explain though why most parents did not experience an urgent need to keep digital media away from their children and granted freedom instead.

Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

We attempted to help parents externalize their tacit knowledge (i.e. emotions that reflect important values) by having open-ended conversations and inviting them to discuss their mediation practices loosely while using prompts such as word cards. Also, we interviewed both parents together so they could complement and correct each other. In our experience this worked well in revealing values and emotions that drive parental mediation. Nevertheless, our outcomes are still based on self-reports. The question thus remains whether the abstractions reflected in our conceptual model are optimal representations of an often messy and elusive reality. Parents might not know exactly why they do what they do or they might have a clear vision that gets lost in the struggles of daily life. For future research observations could be useful, for instance to identify key incidents and, subsequently, discuss with parents the emotions and values involved in their decision making.

Another limitation pertains to the composition of the sample. As our main goal was to contribute to existing theories on parental mediation rather than to generalize findings, the small yet diverse sample of families fits the purpose of the study. However, there are indications that different results might be obtained in samples of parents with older children. Emotions of fear might start to play a larger role when children become even more independent and parents cannot supervise as much. Yet it could also be that the lack of fear in our sample of parents was not primarily related to the age of their children but to the authoritative parenting style Dutch parents tend to adopt (Bucx, 2011). This perhaps makes them more likely to put faith in their children rather than be concerned. More research is necessary to explore whether the values and emotions are similar in different age groups and other cultural settings.

Despite these limitations, we believe this study to be of value. We found that more work needs to be done with respect to how parents mediate, as the practice of giving space has hardly received attention in the mediation literature. Large-scale, survey-based studies mostly focus on restriction as a form of regulation and on co-use and active mediation as a form of guidance (Eastin et al., 2006; Livingstone & Helsper, 2008; Nikken & Jansz, 2006; 2013). Also, in active mediation the role of the parent is confined to talking about media content. This might have suited the teaching opportunities parents had in the television era, but in the digital era parents have many more ways to support, promote and deepen children’s media use. Parents mentioned several of such practices, for instance teaching the child search strategies. We feel quantitative studies can be strengthened by including the practice of giving space and by deepening the definition of active mediation, as is done in some qualitative studies (e.g., Zaman et al., 2016).

Conclusion

With respect to the tacit knowledge we exposed, we believe that the most important lesson is that parents adopt different mediation practices because they embrace different values and emotions. Restriction may come from having to balance different needs within the family, giving space may come from an absence of fear, and guidance may come from importance attributed to the child’s development. Yet there is no one-to-one correspondence beween a value and a mediation practice, as for many parents an element of good parenting also seems to be flexibility. Contexts may vary and each child has unique abilities and desires. This requires parents to be sensitive and make exceptions, or in other words: to do the right thing at the right time.

Appendix A. Overview of Families

|

Family number |

Pseudonym |

Gender |

Age |

Parents’ highest educational level: (A) secondary education, (B) higher professional or university education |

|

1 |

Piet Achterkamp |

m |

56 |

A |

|

|

Annejet Achterkamp |

f |

41 |

A |

|

|

Rosalie Achterkamp |

f |

7 |

|

|

|

Ingmar Achterkamp |

m |

5 |

|

|

2 |

Bart Bergmans |

m |

58 |

A |

|

|

Annemarie Bergmans |

f |

43 |

B |

|

|

Simon Bergmans |

m |

7 |

|

|

|

Klaas Bergmans |

m |

5 |

|

|

3 |

Patrick Hendriks |

m |

46 |

B |

|

|

Willemijn Hendriks |

f |

35 |

B |

|

|

Debby Hendriks |

f |

7 |

|

|

|

Masha Hendriks |

f |

5 |

|

|

4 |

Peter van Dam |

m |

42 |

A |

|

|

Josephita van Dam |

f |

35 |

B |

|

|

Lilou van Dam |

f |

6 |

|

|

|

Inci van Dam |

f |

4 |

|

|

5 |

John Mulder |

m |

47 |

B |

|

|

Petra Mulder |

f |

47 |

B |

|

|

Sophie Mulder |

f |

7 |

|

|

6 |

Arjen Sneijder |

m |

39 |

A |

|

|

Daphne Sneijder |

f |

37 |

A |

|

|

Irene Sneijder |

f |

7 |

|

|

|

Naomi Sneijder |

f |

9 |

|

|

7 |

Cynthia Staring |

f |

28 |

B |

|

|

Haylee Staring |

f |

7 |

|

|

8 |

Philip Driessen |

m |

45 |

B |

|

|

Michelle Driessen |

f |

42 |

A |

|

|

Felicia Driessen |

f |

7 |

|

|

|

Olivia Driessen |

f |

2 |

|

|

9 |

Fatma Özgül |

f |

39 |

A |

|

|

Esra Özgül |

f |

7 |

|

|

10 |

Simone van Aalst |

f |

36 |

A |

|

|

Sven van Aalst |

m |

11 |

|

|

|

Matthijs van Aalst |

m |

7 |

|

|

|

Kars van Aalst |

m |

7 |

|

|

11 |

Jan de Jong |

m |

50 |

A |

|

|

Marlies de Jong |

f |

39 |

B |

|

|

Rik de Jong |

m |

7 |

|

|

|

Julian de Jong |

m |

4 |

|

|

12 |

Gijs Bosch |

m |

41 |

B |

|

|

Katja Bosch |

f |

42 |

B |

|

|

Ties Bosch |

m |

10 |

|

|

|

Lisa Bosch |

f |

6 |

|

|

13 |

Marco Heerschop |

m |

36 |

A |

|

|

Sheila Heerschop |

f |

33 |

A |

|

|

Adwen Heerschop |

f |

10 |

|

|

|

Dex Heerschop |

m |

8 |

|

|

|

Billy Heerschop |

m |

5 |

|

|

|

Esmeralda Heerschop |

f |

4 |

|

|

14 |

Steven van Bunschoten |

m |

44 |

B |

|

|

Monica van Bunschoten |

f |

35 |

A |

|

|

Colin van Bunschoten |

b |

7 |

|

|

|

Roan van Bunschoten |

b |

5 |

|

|

15 |

Joke Scholten |

f |

35 |

A |

|

|

Abigail Scholten |

m |

8 |

|

|

|

Devin Scholten |

f |

6 |

|

| Note: Highlighted in boldface are the parents who participated in the interviews. | ||||

Appendix B. Interview Materials

Activity 1

Activity: sorting 30 cards depicting a variety of activities, toys and devices into three piles of very fun, fun and not so fun for the six/seven-year-old child. These picture show the result of the first activitiy in Family 1:

Materials: 30 cards with the following devices, objects and activities depicted: radio, laptop, toy laptop, Playstation, MP3 player, Nintento DS, television, smartphone, tablet, Duplo, baby doll, books, basketball, car, Playmobil, Barbie, magnetic drawing board, Ninento Wii, toy tablet, e-reader, bicycle, playground, swimming, animals, tennis, boardgame, dancing, drawing, music, iWatch.

Procedure: The interviewer places the materials on the table and gives the following instruction, leaving it to the parents to decide who picks up the cards and puts them with the smileys: “I would now like to do a card game with you. I have put three smileys on the table: a sad smiley, a happy smiley and a very happy smiley. And I have a pile of cards. Can you have a look at the cards and put the things your child does not really like to do with the sad smiley, the things your child likes to do with the happy smiley and the things your child likes to do most with the very happy smiley?”

The interviewer then selects two or three devices that are the child’s favorite according to the parents. For each device, the interviewer asks parents: “You have indicated that your child likes to use this device. Could you tell me more about this?” Follow-up questions are posed for the topics listed below if the parents do not cover these spontaneously. These are phrased as follows: “I am curious [insert topic]. Could you tell me more about this?” The topics are:

- why your child uses the device;

- what your child does with the device;

- when your child uses the device;

- where your child uses the device;

- whether you youself use the device;

- whether siblings use the device;

- whether you manage your child using the device.

Activity 2

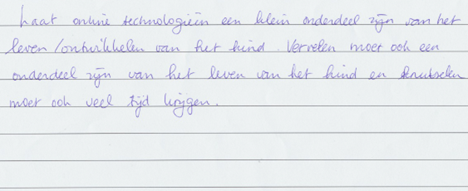

Activitiy: selecting from a set of 30 word cards those words parents associated with the child’s digital media use. The pictures below show the end result of the second activity in Family 1 (left) and Family 15 (right):

Materials: 30 cards with the following words (translated here from Dutch to English): boring, fun, distractive, educational, necessary competences, babysitter, family activity, challenging, difficult, confusing, cosy, isolated, necessary, with dad, with mum, redundant, useful, addictive, explore together, annoying, tension, arguments, fantasy, social, anti-social, curious, relaxing, easy, interesting, informative.

Procedure: The interviewer puts the pile of cards on the table and gives the following instruction, leaving it to the parents to decide who picks up the cards and how to select them: “I would now like to know how you perceive of your child’s use of digital media. I have a pile of cards with words on them. Can you select for me those cards you associate with your child’s digital media use?” The interviewer then clusters the words while deliberating with the parents, for example: “I think challenging and educational go together, do you agree or disagree?” After clusters are formed, the interviewer asks parents to provide more information regarding each cluster: “You have chosen these cards and we have put them together. Could you tell me more about these cards?”

Activity 3

Activity: writing down on a blanc page tips parents might have for other parents concerning children’s digital media use. Below pictures are shown of the end result of the third activity in Family 2. Mum (top example) wrote: “Let online technologies be a small part of the life/developing of the child. Boredom also needs to be a part of the life of the child and crafts also need to get a lot of time. Dad (bottom example) wrote: “Don’t let it replace the “regular” play but let it be only an addition. Be wary of addiction/dependence.”

Materials: lined paper.

Procedure: The interviewer hands each parent lined paper and asks them the following: “Could you write down for me tips you have for other parens about how they can best manage their children’s use of digital media?” After the parents have written down their tips, the interviewer reads the tips out loud and asks parents: “Could you tell me more about that?”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2017 Claudia van Kruistum, Roel van Steensel