Exploring personal characteristics associated with selfie-liking

Vol.10,No.2(2016)

Although taking selfies has become a popular trend among teenagers in many countries, concerns have been raised about the negative personality traits associated with it. However, empirical research that explores the selfie-associated personal characteristics of individuals is still scant. In the present study, the author aims to investigate four personal characteristics that might explain why some individuals like to take selfies more than others. They include the following: (1) narcissism, (2) attention-seeking behavior, (3) self-centered behavior, and (4) loneliness. Questionnaire data were collected from a sample of 300 students from a public university in Thailand; the majority of students were ages between 21 to 24 years old. The results from partial least square regression showed that the degree of selfie-liking that the respondents reported was positively associated with all of these characteristics. The overall findings imply that, although selfies provide the opportunity for individuals to enhance self-disclosure, they can reflect some unhealthy behavior on their part.

Selfie; narcissism; attention seeking; self-centered behavior; loneliness

Peerayuth Charoensukmongkol

National Institute of Development Administration, Bangkok, Thailand

Dr. Peerayuth Charoensukmongkol is an Assistant Professor at the International College of National Institute of Development Administration. His research projects center around an interest in the motivations and outcomes associated with social media use behaviors.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Ames, D. R., Rose, P., & Anderson, C. P. (2006). The NPI-16 as a short measure of narcissism. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 440–450.

Angstman, K. B., & Rasmussen, N. H. (2011). Personality disorders: Review and clinical application in daily practice. American Family Physician, 8, 1253–1260.

Bleske-Rechek, A., Remiker, M. W., & Baker, J. P. (2008). Narcissistic men and women think they are so hot – But they are not. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 420–424. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.05.018

Carpenter, C. J. (2012). Narcissism on Facebook: Self-promotional and anti-social behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 482–486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.011

Chin, W., & Newsted, P. (1999). Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. In R. Hoyle (Ed.), Statistical strategies for small sample research (pp. 307–334). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

DeWall, C. N., Buffardi, L. E., Bonser, I., & Campbell, W. K. (2011). Narcissism and implicit attention seeking: Evidence from linguistic analyses of social networking and online presentation. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 57–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.011

DiTommaso, E., Brannen, C., & Best, L. A. (2004). Measurement and validity characteristics of the short version of the social and emotional loneliness scale for adults. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 64, 99–119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0013164403258450

Ellison, N., Heino, R., & Gibbs, J. (2006). Managing impressions online: Self-presentation processes in the online dating environment. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11, 415–441. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083- 6101.2006.00020.x

Emmons, R. A. (1987). Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 11- 17.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117-140.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

Fox, J., & Rooney, M. C. (2015). The Dark Triad and trait self-objectification as predictors of men’s use and self- presentation behaviors on social networking sites. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 161-165. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.017

Gilbert, P. (2000). The relationship of shame, social anxiety and depression: The role of the evaluation of social rank. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 7, 174–189.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Houghton, D., Joinson, A., Caldwell, N., & Marder, B. (2013). Tagger's Delight? Disclosure and liking behaviour in Facebook: The effects of sharing photographs amongst multiple known social circles. Discussion Paper: 2013-03. University of Birmingham.

Hunter, J. E., Gerbing, D. W., & Boster, F. J. (1982). Machiavellian beliefs and personality: Construct invalidity of the Machiavellianism dimension. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 1293-1305.

Jonason, P. K., & Krause, L. (2013). The emotional deficits associated with the Dark Triad traits: Cognitive empathy, affective empathy, and alexithymia. Personality & Individual Differences, 55, 532–537.

Kock, N., & Lynn, G. S. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13, 546-580.

Lou, L. L., Yan, Z., Nickerson, A., & McMorris, R. (2012). An examination of the reciprocal relationship of loneliness and facebook use among first-year college students. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 46(1), 105-117

Mehdizadeh, S. (2010). Self-presentation 2.0: Narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13, 357-364.

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 556–563.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879- 903.

Qiu, L., Lu, J., Yang, S., Qu, W., & Zhu, T. (2015). What does your selfie say about you? Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 443-449. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.032

Skues, J. L., Williams, B., & Wise, L. (2012). The effects of personality traits, self-esteem, loneliness, and narcissism on Facebook use among university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 2414-2419. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.012

Sorokowski, P., Sorokowska, A., Oleszkiewicz, A., Frackowiak, T., Huk, A., & Pisanski, K. (2015). Selfie posting behaviors are associated with narcissism among men. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 123–127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.004

Steinfield, C., Ellison, N. B., & Lampe, C. (2008). Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29, 434–445.

Tandoc, E. C., Jr., Ferrucci, P., & Duffy, M. (2015). Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is facebooking depressing? Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 139–146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.053

Vazire, S., Naumann, L. P., Rentfrow, P. J., & Gosling, S. D. (2008). Portrait of a narcissist: Manifestations of narcissism in physical. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 1439–1447.

Wade, N. J. (2014). The first scientific 'selfie'? Perception, 43, 1141-1144.

Weiser, E. B. (2015). #Me: Narcissism and its facets as predictors of selfie-posting frequency. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 477–481. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.007

Introduction

“Selfie”, which refers to a self-portrait photograph taken using a digital camera or smartphone, has become a buzzword and the biggest trend among teenagers in recent years. Nowadays, people, especially teenagers, are often seen holding cameras at arm’s length and pointing them toward themselves to take photos at almost every location. More specifically, taking selfies has become a popular activity through which people present themselves to the public. They usually upload selfie photos to social networking sites (SNSs), such as Facebook and Instagram, and share them among friends in their networks. Although selfies allow individuals to promote self-disclosure, there has been criticism concerning some unhealthy personalities associated with this behavior (Weiser, 2015). For example, a few journalists have criticized taking selfies as a selfish act because people tend to care too much about their appearance in the photos and that sometimes makes them ignore the people around them. Some have also indicated that addiction to selfies may cause individuals to develop narcissistic behaviors and may negatively affect their relationships with others (Fox & Rooney, 2015; Weiser, 2015).

Despite society’s concerns about the negative personality traits associated with selfies, empirical evidence in this area is still limited. The pioneer work on the personalities associated with of taking selfies is the study that Fox and Rooney (2015) conducted using a sample from the U.S. It focused on the association of selfies with narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Following this initial work, Sorokowski et al (2015) and Weiser (2015) further explored the linkage between selfies and narcissism. They used samples from Poland and the U.S., respectively. Recently, the research of Qiu et al (2015) explored the connection between big five personality traits and the selfie behavior of a Chinese sample. Given that prior research on personalities associated with selfies has not been widely explored, the aim of this study is to offer more on the subject using a sample from Thailand. In particular, the present research investigates some personal characteristics of individuals that might be associated with selfie-liking. Selfie-liking is defined in this paper as the degree to which individuals feel emotionally connected to selfies and integrate them into their daily activities. Generally, individuals who like selfies tend to enjoy them and feel that taking them is an important activity in their daily lives. Moreover, they always look for places where they can take selfies and are upset if they are prevented from taking selfies.

In the present study, the author focuses on four personal characteristics that may associate with selfie-liking, including: (1) narcissism, (2) attention-seeking behavior, (3) self-centered behavior, and (4) loneliness. While attention-seeking behavior and self-centered behavior are aspects of the narcissistic trait, they are not treated similarly in this research. Here, narcissism is conceptualized as a perception that individuals have about themselves, while attention-seeking behavior and self-centered behavior are conceptualized as behaviors that individuals frequently express. These characteristics have been selected for this research because they are the issues concerning selfie-taking behavior about which society has expressed concern. In particular, narcissism, attention-seeking behavior, and self-centered behavior are consistent with what Fox and Rooney (2015) described as ‘the dark triad of personalities’ associated with selfies. Results from this study will provide additional insight into some personal characteristics that explain why some individuals tend to enjoy taking selfies more than others.

Literature review

Selfies

The Oxford Dictionary officially defines the selfie as a photograph that one has taken of oneself, usually with a webcam or smartphone. According to Wade (2014), although the term “selfie” has become a fad word in recent years, the selfie’s history actually began in the year 1523, when artists first created self-portrait paintings in convex mirrors. In addition, it was documented that the first photographic selfie was taken in 1939 by the American photographer named Robert Cornelius, who took a photo of himself by taking advantage of the slow photographing process of the era (Wade, 2014). Today, advances in smartphone technology and the increase in the number of smartphone users are the main reasons why selfies have become a prevalent trend almost everywhere. Because people who take selfies usually share the photos they take on SNSs, the photos normally portray specific impressions of the self through individuals’ physical appearances and photography styles (Carpenter, 2012). As a result, some individuals spend considerable time and effort adjusting or improving their selfie photos to make them look impressive before posting them on SNSs (Weiser, 2015).

Research suggests that individuals are motivated to take selfies for many reasons. Basically, because people normally take selfies and post photos on SNS to impress others; the amount of time that individuals regularly spend on SNS was found as a factor that strongly explains the intensity of selfie posting (Fox & Rooney, 2015; Weiser, 2015). Prior research also identifies personal characteristics associated with the selfie. For example, Fox and Rooney (2015) found that males tend report higher selfie-posting frequency than females. However, Sorokowski et al (2015) discovered that females tended to report posting more selfies and group selfies than did men. In terms of age, Weiser (2015) found that older people tended to report a higher-frequency of selfie-posting than younger people. In addition, Qiu et al (2015) suggested that selfies may be associated with personality traits such as agreeableness and extraversion, which are the characteristics that reflect sociability of individuals; thus, individuals who generally like to develop social relationships with others tend to have high motivation to take selfies. Furthermore, social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954) and social rank theory (Gilbert, 2000), which emphasize the role of social environment in explaining SNS behavior imply that individuals who are in peer groups characterized by high degrees of social comparison and competition among members are more likely to take selfies and post photos on SNS to make themselves look more outstanding than their peers (Tandoc Jr et al, 2015).

While selfies allow individuals to promote themselves to the public, critics have argued that they can potentially lead to unhealthy behaviors such as narcissism and selfishness (Fox & Rooney, 2015; Sorokowski et al, 2015; Weiser, 2015). In particular, Fox and Rooney (2015) argued that selfies can be associated with three negative personality traits, including Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy. Fox and Rooney (2015) labeled the three the dark triad of personalities associated with selfies (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). According to Fox and Rooney (2015), Machiavellianism is characterized by the desire to satisfy one’s own needs with little regard for morals (Hunter et al, 1982); narcissism is characterized by a sense of grandiosity, dominance, and entitlement that makes individuals perceive themselves as being superior to others (Mehdizadeh, 2010); and psychopathy is characterized by lack of empathy and impulsive and thrill-seeking behaviors, regardless of the cost to others (Jonason & Krause, 2013). Based on the dark triad of personalities that Fox and Rooney (2015) described, this research proposes four personal characteristics that might be associated with selfie-liking. They include narcissism, attention-seeking behavior, self-centered behavior, and loneliness. The next section will discuss the aforementioned characteristics and the connection between each personal characteristic and selfie intensity in greater detail.

Individual characteristics associated with selfie intensity

Narcissism. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), which the American Psychiatric Association (2013) published, defines narcissism as "self-admiration that is characterized by tendencies toward grandiose ideas, fantasized talents, exhibitionism, and defensiveness in response to criticism; and by interpersonal relations that are characterized by feelings of entitlement, exploitativeness, and lack of empathy.” Narcissistic individuals tend to develop positive self-views of agentic traits, including intelligence, physical attractiveness, and power (Emmons, 1987; Mehdizadeh, 2010). These characteristics of narcissism can potentially explain why some individuals are obsessed with selfies. Basically, narcissists tend to be concerned about physical appearance (Bleske-Rechek et al, 2008). They like to dress and adorn themselves in provocative, attention-grabbing ways and overestimate their attractiveness in the eyes of others (Vazire et al, 2008). Because of this behavior, narcissists tend to enjoy taking selfies. Doing so allows them to gain full control of how they look in the photos. Normally, selfie photos are flattering images of oneself with which one seeks to make an impression on others (Fox & Rooney, 2015; Weiser, 2015). As Weiser (2015) mentioned, selfies normally include the most explicit elements of ostentation and self-propagation. Taking selfies can serve as a novel psychological maneuver through which narcissistic individuals can easily fulfill their motivations. Moreover, narcissists tend to be fonder of selfies because they can upload them on SNSs, allowing them to satisfy their desire to engage in self-promoting behavior (Sorokowski et al, 2015).

In prior research, evidence about the linkage between selfies and narcissism is apparent. For example, the study of Fox and Rooney (2015) initially found a strong connection between narcissism and the number of selfies posted. The study by Weiser (2015) focused on three sub-dimensions of narcissism, including Leadership/Authority, Grandiose Exhibitionism, and Entitlement/Exploitativeness; it found that the selfie-posting frequency was strongly associated with the Leadership/Authority and Grandiose Exhibitionism dimensions alone. Sorokowski et al (2015) used four sub-scales of narcissism, including self-sufficiency, vanity, leadership, and admiration demand; they found that the linkage between overall narcissism scores and own selfie-posting was stronger for males than for females. Given all the evidence for the connection between selfies and narcissism in prior research, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: There is a positive association between selfie-liking and narcissism.

Attention-seeking behavior. In addition to the association that narcissism might have with selfie-liking, the study argues that their association can present indirectly through behavior that is strongly linked to narcissism, including attention-seeking behavior and self-centered behavior. First, attention-seeking behavior normally happens when people act or behave in a way that is intended to make others pay attention to them. In fact, attention-seeking behavior is linked to the narcissistic trait because being the center of attention fulfills the goal of being agentic (Nathan DeWall et al, 2011). For example, Weiser (2015) suggested that narcissists are motivated to gain others' attention and admiration to maintain their inflated self-views. Although this behavior usually happens in children, it is also normal in adults. In many cases, attention seeking can result in productive behavior (e.g., working hard to gain acknowledgment from others). However, excessive attention seeking can affect the psychological well-being of some individuals, and that may cause them to engage in some inappropriate behavior (Angstman & Rasmussen, 2011). Generally, because those with attention-seeking behavior like to engage in behavior that aims to attract others’ attention, they tend to like selfies and perceive doing so as important because they can post their selfies on SNSs to attract and obtain positive feedback from their peers. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2: There is a positive association between narcissism and attention-seeking behavior.

H3: There is a positive association between selfie-liking and attention-seeking behavior.

Self-centered behavior

Another behavior that is linked to narcissism and might also be associated with selfie-liking is self-centered behavior. Generally, individuals with self-centered behavior tend to care more about themselves than other people. They tend to think of their own needs and wants and, instead of trying to understand or be empathetic to others, they expect others to understand them. More particularly, because individuals tend to focus mainly on themselves when they take selfies, this tendency might relate to the self-centered behavior that they exhibit. As mentioned in the beginning of the article, society has recently begun to express concern that taking selfies may be considered a selfish act because it makes people care too much about their appearance in photos and fail to consider other people around them. A study by Fox and Rooney (2015) supported this argument, showing that people who regularly posted selfies on SNSs tended to display lack of empathy. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: There is a positive association between narcissism and self-centered behavior.

H5: There is a positive association between selfie-liking and self-centered behavior.

Loneliness. Last, this research proposes that the degree of selfie-liking may be related to the level of loneliness that an individual experiences. Loneliness was defined as “initial social relationships being less than desired or achieved, including uneasy feelings, distress, and perceptions of deficiencies in one’s social relations” (Lou et al, 2012, p. 106). Loneliness is considered to be a personal characteristic associated with selfies because prior research showed that it tended to relate strongly to the intensity of SNS activities, particularly information posting and sharing (Lou et al, 2012; Skues et al, 2012). Given that selfie-taking is an activity aimed at enhancing self-disclosure and social communication on SNSs (Steinfield et al, 2008), it can be considered to be important to those who experience loneliness. More specifically, people may enjoy taking selfies to reduce their loneliness because posting selfie photos on SNSs and gaining feedback from their friends helps to enhance self-disclosure and social communication (Steinfield et al, 2008). However, Steinfield et al (2008) argued that taking selfies can cause individuals to develop shallow relationships with others, and that can create more loneliness. This argument is supported by a research indicating that participants who reported that they posted more selfies tended to score lower on the intimacy measure (Houghton et al, 2013). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6: There is a positive relationship between selfie-liking and loneliness.

Control variables. In addition to the main variables hypothesized to relate to selfie-liking, control variables were included in the analysis to capture the effect of other factors that might affect selfie behavior. First, the author controlled for the effects of age and education because selfies tend to be more popular among teenagers than adults. Second, the study controlled for the effect of gender due to the evidence that females took selfies more frequently than males (Fox & Rooney, 2015; Sorokowski et al, 2015). Third, because people normally take selfies and post photos on SNSs, the author also controlled for the effect of the intensity of SNS use. Fourth, the study took into consideration the level of friendliness that individuals exhibited. More particularly, it could be expected that those who were friendly and liked to develop social relationships with others tended to have more connections on SNSs, and that motivated them to enjoy selfie more than others. Finally, the study controlled for the effect of peer pressure on selfie intensity. More specifically, it was possible that individuals in peer groups characterized by high degrees of social comparison and competition among members tend to enjoy selfies because it makes themselves look more outstanding than their peers.

Methods

Sample and data collection

The sample employed in this research encompasses undergraduate and graduate students at a public university in Bangkok, Thailand. Data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire survey. The questionnaires were distributed in person to students on campus using the convenient sampling method. The students were informed that participation in the survey was voluntary and the survey was completely anonymous. A total of 300 students agreed to participate. The majority of the respondents were female, aged between 21 and 24 years, and held bachelor’s degrees. Most of them reported that they spent more than 50 percent of their leisure time on SNSs. The demographic characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the sample.

|

Demographic |

N (%) |

|

Age |

Under 21 years: 106 (35.3%) 21-24 years: 125 (41.7%) 25-34 years: 52 (17.3%) 35-44 years: 9 (3%) 45-54 years: 6 (2%) Over 55 years: 2 (1%) |

|

Gender |

Male: 119 (39.7%) Female: 181 (60.3%) |

|

Education |

Below bachelor’s degree: 97 (32.2%) Bachelor’s degree: 163 (54.3%) Master’s degree or higher: 40 (13.3%) |

|

Intensity of SNS-use (measured as a percentage of total leisure time) |

Less than 10 percent: 13 (4.3%) 10-20 percent: 33 (11%) 21-30 percent: 56 (18.7%) 31-40 percent: 63 (21%) 41-50 percent: 45 (15%) More than 50 percent: 90 (30%) |

Measures

Selfie-liking. To date, there is no existing scale for the measurement of selfie-liking. Thus, the author developed a scale to measure this construct. Selfie-liking is measured in terms of the perceived importance that individuals attach to selfies. Individuals were asked to evaluate their selfie behavior in six categories as part of their daily activities. Sample items included “Taking selfies makes me happy” and “I take selfies whenever I have a chance.” All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Narcissism. Narcissism was measured using eight items from the NPI-16 narcissism scale that Ames et al (2006) developed. The official scale consists of sixteen items. Because the data were collected voluntarily from the respondents on campus and they did not receive any incentive for participation, the author had to use a parsimonious questionnaire to encourage them to participate and to ensure that they would not experience fatigue from answering a lengthy survey (as that would subsequently affect the quality of the data). Thus, only eight items out of the original sixteen items were selected. The criteria for selecting the items to be included in the final questionnaire came from the pilot testing of the original sixteen items. The pilot testing was conducted with a group of graduate students. In particular, the questions that the respondents indicated they did not understand clearly and those that had similar meanings to other questions were not included in the final questionnaire. Sample items used to measure narcissism in the final questionnaire included “I am an extraordinary person” and “I expect a great deal from other people.” All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Attention-seeking behavior. Attention-seeking behavior was measured using four items developed by the author. Sample items included “I like to display behaviors that make other people pay attention to me” and “I normally behave in a way that can draw the attention of people around me.” All items were rated on five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

Self-centered behavior. Self-centered behavior was measured using five items developed by the author. Sample items included “I normally care more about benefits to me than about benefits to others” and “People around me think that I am a selfish person.” All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

Loneliness. Loneliness was measured using a scale that the author adapted from the social and emotional loneliness scale, which DiTommaso et al (2004) originally developed. Three items belonged to the social loneliness category and three items belonged to the emotional loneliness category. Although the original scale consisted of ten questions, only six questions were selected in order to ensure that the questionnaire was parsimonious. In particular, the reverse coded items were not included in the survey. Sample items used to measure loneliness in the final questionnaire included “I feel alone when I am with my family” and “I do not have any friends who share my views, but I wish I did.” All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

Control variables. Control variables including age, gender, intensity of SNS use, friendliness, and peer pressure were measured as follows. Age was measured on the ordinal scale. Gender was measured with a dummy variable (Male=1; Female=0). Intensity of SNS use was measured ordinally by asking the respondents what percentage of their leisure time they normally spent on SNSs. Friendliness was measured using five items developed by the author. Some example items include “I consider myself a sociable person” and “I get along well with other people easily”. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Peer pressure on selfie-liking was also measured with three items developed by the author. Two examples include “Peers in my group like to show off about being better than others in the group” and “Peers in my group normally compete to be the best in the group”. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Constructs that were measured using multiple-item items, including selfie-liking, attention-seeking behavior, self-centered behavior, loneliness, friendliness, and peer pressure, were treated as reflective latent variables, whereas other variables were treated as manifest variables. PLS created latent variable component scores using the weighted sum of indicators (Chin & Newsted, 1999). The items that were used to measure all reflective latent variables are shown in Table 2.

Construct reliability and validity

The reliability and validity of all reflective latent variables were checked. First, construct reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient and the composite reliability coefficient. All values exceeded the widely suggested value of .7, indicating that the level of reliability of all the constructs was satisfactory (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Second, convergent validity was assessed to make sure that all items that aimed to measure the underlying constructs truly belonged to the constructs. Convergent validity was estimated using factor loadings. The results indicated that all loadings exceeded .5, which was the value that Hair et al (2009) recommended as a minimum threshold for good convergent validity. Third, discriminant validity was evaluated to make sure that items that measured different constructs did not overlap with one another. Discriminant validity was assessed using the average variance extracted (AVE). The results showed that the square root of the AVE of each construct was greater than other correlations involving that construct, thereby confirming that discriminant validity was satisfactory (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Results from factor loadings are reported in Table 2; AVEs and the correlation matrix are reported in Table 3.

Table 2. Construct reliability and validity.

|

Constructs |

Factor loading |

Cronbach’s alpha |

Composite reliability |

|

Selfie-liking |

|

|

|

|

Taking selfies makes me happy. |

.864 |

.919 |

.937 |

|

I take selfies whenever I have a chance. |

.847 |

|

|

|

Taking selfies is an important activity in my daily life. |

.905 |

|

|

|

I would be upset if someone tried to stop me from taking selfies. |

.853 |

|

|

|

I am very good at taking selfies. |

.739 |

|

|

|

I am always looking for a place at which to take selfies. |

.857 |

|

|

|

Narcissism |

|

|

|

|

I like to be the center of attention. |

.747 |

.885 |

.908 |

|

I like having authority over people. |

.796 |

|

|

|

I find it easy to manipulate people. |

.716 |

|

|

|

I am apt to show off if I get the chance. |

.785 |

|

|

|

Everybody likes to hear my stories. |

.650 |

|

|

|

I can make anybody believe anything I want them to. |

.811 |

|

|

|

I am an extraordinary person. |

.735 |

|

|

|

I expect a great deal from other people. |

.757 |

|

|

|

Loneliness |

|

|

|

|

I feel alone when I am with my family. |

.757 |

.880 |

.909 |

|

I can’t depend on my family for support and encouragement. |

.739 |

|

|

|

No one in my family understands me. |

.756 |

|

|

|

I do not have any friends who understand me, but I wish I did. |

.826 |

|

|

|

I do not have any friends who share my views, but I wish I did. |

.843 |

|

|

|

I am unable to depend on my friends for help, but I wish I could. |

.818 |

|

|

|

Attention-seeking behavior |

|

|

|

|

I normally behave in a way that can draw the attention of people around me. |

.817 |

.866 |

.909 |

|

I like to display behaviors that make other people pay attention to me. |

.888 |

|

|

|

I feel proud when I am able to draw the attention of people around me. |

.817 |

|

|

|

I normally behave in a way that makes me stand out from the crowd. |

.856 |

|

|

|

Self-centered behavior |

|

|

|

|

I normally care more about benefits to me than about benefits to others. |

.665 |

.780 |

.851 |

|

I don’t normally allow other people to borrow my personal belongings. |

.769 |

|

|

|

I prefer talking about myself to listening to others. |

.778 |

|

|

|

People around me think that I am a selfish person. |

.760 |

|

|

|

When I know something good, I normally keep it to myself instead of sharing. |

.673 |

|

|

|

Peer pressure |

|

|

|

|

Peers in my group like to show off about being better than others in the group. |

.859 |

.847 |

.908 |

|

Peers in my group like to compare themselves to each other in terms of their possessions. |

.909 |

|

|

|

Peers in my group normally compete to be the best in the group. |

.858 |

|

|

|

Friendliness |

|

|

|

|

I have good interpersonal skills. |

.855 |

.845 |

.892 |

|

I have a lot of friends. |

.866 |

|

|

|

I consider myself a sociable person. |

.808 |

|

|

|

I get along well with other people easily. |

.861 |

|

|

|

It is easy for me to make friends with people with whom I am not familiar. |

.526 |

|

|

Statistical analysis

Partial least squares (PLS) regression was used as a statistical technique to test the hypotheses. The technique allows the simultaneous assessment of multiple hypotheses. It allows the measurement of constructs as reflective latent variables and offers more advantages than covariance-based structural equation modeling since it does not require data to be normally distributed. In particular, PLS was suitable for this study because the results from the Jarque-Bera test of normality indicated that many variables, including selfie-liking, loneliness, attention-seeking behavior, peer pressure, friendliness, age, gender, education, and the intensity of SNS use were not normally distributed. PLS estimation was performed using WarpPLS version 5.0.

Table 3. Correlations among variables, internal consistency, and convergent validity.

|

Mean |

S.D. |

SF |

NASS |

ASB |

SCB |

LONE |

AGE |

MALE |

SMUI |

FRD |

PP |

|

|

SF |

2.281 |

1.176 |

(.845) |

.366** |

.413** |

.352** |

.237** |

-.11 |

-.18** |

.317** |

.137* |

.253** |

|

NASS |

2.799 |

1.005 |

(.726) |

.6** |

.351** |

.114* |

.049 |

.071 |

.169** |

.235** |

.267** |

|

|

ASB |

2.643 |

1.044 |

(.845) |

.51** |

.206** |

-.077 |

.15** |

.063 |

.247** |

.328** |

||

|

SCB |

2.263 |

1.031 |

(.728) |

.426** |

.088 |

.164** |

.064 |

-.04 |

.405** |

|||

|

LONE |

2.101 |

1.138 |

(.791) |

.118* |

.03 |

.068 |

-.128* |

.316** |

||||

|

AGE |

1.997 |

.967 |

(1) |

.021 |

-.043 |

.003 |

.074 |

|||||

|

MALE |

.397 |

.49 |

(1) |

-.105 |

.039 |

.075 |

||||||

|

SMUI |

4.213 |

1.526 |

(1) |

-.011 |

.167** |

|||||||

|

FRD |

3.508 |

1.445 |

(.85) |

.098 |

||||||||

|

PP |

2.274 |

1.047 |

(.876) |

|||||||||

|

Notes: *p ≤ .05; **p ≤ .01; Average variance extracted from latent variables shown in the parentheses; SF=selfie intensity, NASS=narcissism, ASB=attention-seeking behavior, SCB=self-centered behavior, LONE=loneliness, AGE=age, MALE=male dummy variable, SMUI=social media use intensity, FRD=friendliness, PP=peer pressure. |

||||||||||||

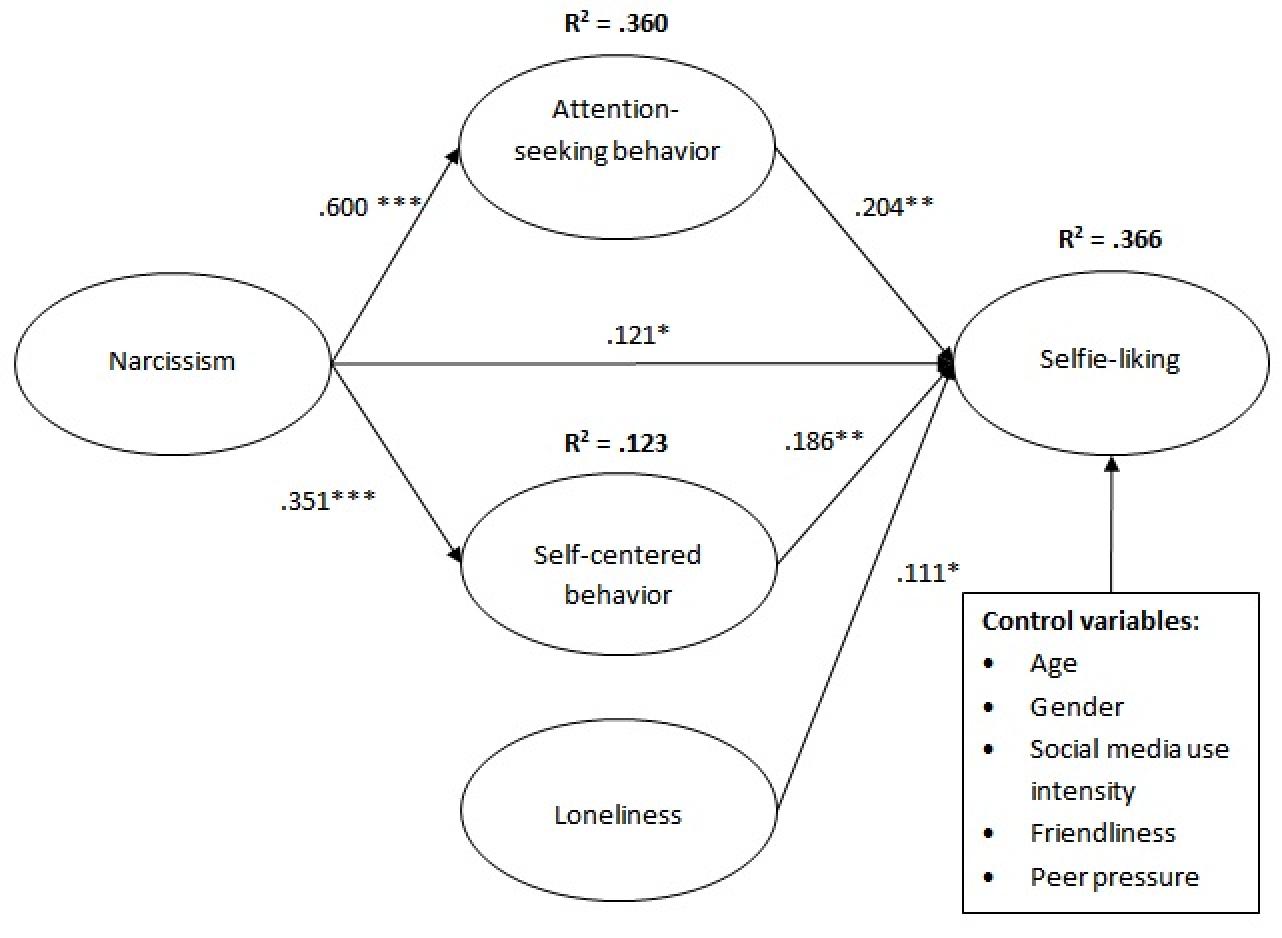

Figure 1. PLS results.

Notes: * p ≤.05, ** p ≤ .01, *** p ≤ .001, Standardized coefficients are reported.

Results

The results from PLS analysis are presented in Figure 1. The standardized coefficients and t-values were calculated using a Jackknifing resampling procedure. Next, multicollinearity was assessed using the full variance inflation factor (VIF). The highest value of the full VIF indicator was 2.117, which was lower than 3.3. This indicated that multicollinearity was not a serious issue in the analysis. Finally, the possible issue of common method bias (CMB) in the data was assessed based on two analyses. First, Kock and Lynn (2012) argued that the full VIF statistics could serve as a technique that captured the possibility of CMB in the PLS model analysis. They proposed that a full collinearity VIF lower than the critical value of 3.3 could provide some evidence that CMB might not be a major threat. Second, Harman’s one-factor test, which Podsakoff et al (2003) recommended, was performed separately in SPSS Amos 20.0. The results did not indicate that the one-factor confirmatory factor analysis model fit the data well (χ2=1626.5; d.f.=645; p<.001). Overall, these findings alleviated a concern about CMB in the analysis.

Hypothesis 1 predicted a positive relationship between selfie-liking and narcissism. The results indicated that they were positively related and the relationship was statistically significant (β=.121; p=.04). Thus, hypothesis 1 was supported. Hypothesis 2 predicted a positive relationship between narcissism and attention-seeking behavior. The results significantly supported this hypothesis (β=.6; p<.001). Hypothesis 3 predicted a positive relationship between selfie-liking and attention-seeking behavior. The results significantly supported this hypothesis (β=.204; p=.002). Hypothesis 4 predicted a positive relationship between narcissism and self-centered behavior. The results also significantly supported this hypothesis (β=.351; p<.001). Hypothesis 5 predicted a positive association between selfie-liking and self-centered behavior. The results also significantly supported this hypothesis (β=.186; p=.002). Hypothesis 6 predicted a positive relationship between selfie-liking and loneliness. The results significantly supported this hypothesis as well (β=.111; p=.031).

Concerning the relationship between selfie-liking and the control variables, the analysis showed that selfie-liking was positively associated with the intensity of social media use (β=.232; p<.001), with friendliness (β=.089; p=.046), and with peer pressure (β=.022; p=.339); but it was negatively associated with age (β=-.117; p=.004), and the male dummy variable (β=-.231; p<.001). Only the relationships with social media use intensity, friendliness, age, and the male dummy variable were statistically significant.

Lastly, considering prior studies’ findings that the personality characteristics associated with selfie behavior tended to be stronger for males than for females (Fox & Rooney, 2015; Sorokowski et al, 2015), the additional analysis was performed to explore whether the linkage between selfie-liking and the personality characteristics that this research considered tended to differ between males and females. The moderating effect analysis was performed using a male dummy variable as a moderator. However, the results did not indicate any significant difference between males and females regarding the association between selfie-liking and the personality characteristics linked to it.

Discussion

The objective of this research was to investigate the relationship between selfie-liking and personal characteristics using a student sample from Thailand. Overall, the empirical evidence obtained from PLS analysis was in line with the hypotheses. First, the results revealed that selfie-liking appeared to relate significantly to narcissism and to two behaviors, attention-seeking behavior and self-centered behavior, that were strongly linked to it. These findings suggested that individuals who reported higher degree of selfies liking tended to exhibit these characteristics to a greater extent than those who reported lower degree of selfies liking. More specifically, these results were consistent with previous research, which found that narcissistic individuals who liked to create self-impressions tended to be more prone to engaging in unhealthy behaviors that allowed them to fulfill this desire (Bleske-Rechek et al, 2008; Nathan DeWall et al, 2011). Indeed, the findings were also consistent with extant studies, which proposed that computer-mediated communication, especially social media, could serve as a means for individuals to enhance self-presentational behaviors (Ellison et al, 2006; Mehdizadeh, 2010). Because taking selfies allows individuals to gain full control of what other people see in the photos, it is not surprising that those who exhibit these characteristics tend to like selfie because it helps them achieve this personal goal (Weiser, 2015). Second, the results revealed the positive linkage between selfie-liking and loneliness, suggesting that individuals who felt lonely were the group that like to selfie more than those who did not. More specifically, this finding was consistent with previous research that found that loneliness was among the major factors that motivated individuals to engage more in computer-mediated communication activities to alleviate them (Lou et al, 2012; Skues et al, 2012). In the present study, the author provided additional evidence that taking selfies might also serve this role. To be more specific, taking a selfie and sharing it with the public to get favorable feedback from others might allow individuals to feel socially connected to other people, thereby lessening their sense of solitude. This can be among the reasons why individuals with higher degree of loneliness tended to report selfie-liking to a greater extent than those with lower degree of loneliness

Given the overall findings obtained using the student sample from Thailand, the evidence from the research was consistent with the results from the prior works on taking selfies that used samples from the Western context (Fox & Rooney, 2015; Sorokowski et al, 2015; Weiser, 2015). More specifically, the present research provided additional support for the association of the dark triad of personalities with the taking of selfies, showing that it was also valid for the Eastern context. In addition, the present study extended prior research by showing the connection between the degree to selfie-liking and loneliness. This was a personal characteristic associated with selfies that had not previously been explored. Regarding the role of gender, the results from correlation analysis indicated that the degree of the self-centered behavior and attention-seeking behavior of the Thai sample were significantly higher for males than for females. However, it showed that males appeared to rate higher than females in the degree of selfie-liking. Nonetheless, unlike prior research that found support for the difference between males and females regarding the personality traits associated with selfies (Fox & Rooney, 2015; Sorokowski et al, 2015), the present research did not show any significant difference between males and females when gender was considered as a moderator.

Despite the interesting findings, some research limitations need to be mentioned. First, the analysis is based on associations between variables. Because cross-sectional data were used in the analysis, as mentioned earlier, causal relationships cannot be inferred. Thus, a study that employs longitudinal data collection will be required to address this issue. Second, data were only collected from a student sample from a single university. This can limit the generalizability of the findings to a larger population. Third, using self-reported measures can present some bias in measurement. In particular, selfie-liking was measured in terms of one’s emotional attachment to selfies. This variable did not take into consideration how many pictures in general the participants took and posted on SNSs. Although the author assumed that individuals who liked selfies tended to take them more extensively than those who did not like them, this variable may not have actually reflected the number of selfies that the individuals took and the degree to which they posted selfie photos on SNSs. Still, a positive and significant association between selfie-liking and SNS use intensity may alleviate this concern as it would imply that people who liked selfies tended to spend more time on SNSs as well. Thus, the author suggests that future research will need to incorporate selfie posting as an additional measurement. Last, the study used scales that had not been validated to measure selfie-liking and some other personality characteristics. This could raise concerns about the validity of the measures. Therefore, there is a need for future studies to validate these scales with a different sample group. Also, because a parsimonious questionnaire was required for data collection, not all of the questions in the official scale measured narcissism and loneliness. This practice can render the completeness of the scale items questionable. Thus, future research will need to incorporate all the scale items in order to ensure the completeness of the measurements.

Regarding the study's implications, the overall findings provide additional insight into the personal characteristics that explain why some individuals feel emotional attached to selfie more than others. In particular, the results that revealed the correlation between selfie-liking and attention-seeking behavior and self-centered behavior implied that selfie taking could be linked to unhealthy behaviors. This provides evidence in support of society’s concern about the selfish acts associated with selfies. Moreover, the positive correlation between selfie-liking and loneliness implies that individuals who feel lonely tend to enjoy selfies more than those who do not experience this feeling. Ultimately, the study suggests that taking selfies can have benefits, as it allows individuals to enhance their self-exposure as suggested in prior research (Qiu et al, 2015). However, it is important to realize that taking selfies may also be associated with some unhealthy behaviors (Fox & Rooney, 2015). Not only do individuals who become obsessed with taking selfies tend to feel that their personal lives and psychological well-being are deteriorated, but they may feel that relationship qualities with others are also impaired. Some experts have argued that selfie-taking behavior can be linked to mental illness; however, psychologists suggest that it is not an addiction but a symptom of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), which occurs when an individual constantly checks his or her appearance and tries to take perfect photos to impress others (Fox & Rooney, 2015; Sorokowski et al, 2015; Weiser, 2015). This could be the reason why individuals who like to take selfies tend to focus too much on themselves and express less concern about others. In conclusion, while many people consider taking selfies to be an enjoyable activity, those who take selfies need to concern themselves with the unhealthy behaviors that might be associated with this activity as well.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2016 Peerayuth Charoensukmongkol