Habitual checking, delayed tasks: Why parental mediation fails to moderate adolescent mobile habits and procrastination

Vol.20,No.1(2026)

Smartphones are integral to adolescents’ lives, yet excessive use raises concerns about psychological impacts like procrastination. Although frameworks such as addiction, internet use disorder, and problematic internet use offer valuable insights into mechanisms and outcomes, they are less applicable to analyzing specific digital behaviors that do not reach pathological levels but still result in negative consequences. To address this gap, this study adopts a habit-centered perspective to investigate the interplay between mobile checking habits, procrastination, and parental mediation among rural Chinese adolescents. Through a purposive survey of 810 participants, we examine how social digital pressure and deficient self-regulation contribute to the formation of mobile checking habits, and whether different parental mediation strategies moderate the link between such habits and procrastination. Results indicate that social digital pressure and deficient self-regulation are positively associated with the formation of mobile checking habits and reveal a positive correlation between frequent mobile checking and procrastination. Neither restrictive nor active mediation altered the positive association between mobile checking habits and procrastination. Moreover, restrictive mediation—implemented through strict rules—further intensified the positive link between phone checking and procrastination. These findings challenge one-size-fits-all approaches to digital parenting and highlight the unintended consequences of overly rigid controls. This study contributes to debates on technology habits by reframing the role of parental mediation and advocating for context-sensitive approaches to digital well-being.

mobile checking habit; procrastination; self-regulation; social digital pressure (SDP); parental mediation

Jinghan Ma

School of Media and Communication, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

Jinghan Ma is a M.Phil student in the School of Media and Communication at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. His research interests revolve around societal effect of emerging media, digital culture, and digital inequality.

Yungeng Li

School of Media and Communication, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

Yungeng Li is a tenured associate professor in the School of Media and Communication at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China. His research interests center around the intersection of digital culture and mental health communication.

Bayer, J. B., & Campbell, S. W. (2012). Texting while driving on automatic: Considering the frequency-independent side of habit. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(6), 2083–2090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.06.012

Bayer, J. B., Campbell, S. W., & Ling, R. (2016). Connection cues: Activating the norms and habits of social connectedness. Communication Theory, 26(2), 128–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12090

Bayer, J. B., & LaRose, R. (2018). Technology habits: Progress, problems, and prospects. In B. Verplanken (Ed.), The psychology of habit (pp. 111–130). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97529-0_7

Benrazavi, R., Teimouri, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Utility of parental mediation model on youth’s problematic online gaming. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13(6), 712–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9561-2

Bernstein, K., Zarski, A.-C., Pekarek, E., Schaub, M. P., Berking, M., Baumeister, H., & Ebert, D. D. (2023). Case report for an internet- and mobile-based intervention for internet use disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, Article 700520. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.700520

Beutel, M. E., Klein, E. M., Aufenanger, S., Brähler, E., Dreier, M., Müller, K. W., Quiring, O., Reinecke, L., Schmutzer, G., Stark, B., & Wölfling, K. (2016). Procrastination, distress and life satisfaction across the age range - A German representative community study. PLoS ONE, 11(2), Article e0148054. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148054

Billieux, J., Maurage, P., Lopez-Fernandez, O., Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Current Addiction Reports, 2(2), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y

Billieux, J., Schimmenti, A., Khazaal, Y., Maurage, P., & Heeren, A. (2015). Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 119–123. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.009

Bouna-Pyrrou, P., Aufleger, B., Braun, S., Gattnar, M., Kallmayer, S., Wagner, H., Kornhuber, J., Mühle, C., & Lenz, B. (2018). Cross-sectional and longitudinal evaluation of the social network use disorder and internet gaming disorder criteria. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, Article 692. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00692

Bourdieu, P. (2013). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

Brand, M., Antons, S., Bőthe, B., Demetrovics, Z., Fineberg, N. A., Jimenez-Murcia, S., King, D. L., Mestre-Bach, G., Moretta, T., Müller, A., Wegmann, E., & Potenza, M. N. (2024). Current advances in behavioral addictions: From fundamental research to clinical practice. American Journal of Psychiatry, 182(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.20240092

Brand, M., Müller, A., Wegmann, E., Antons, S., Brandtner, A., Müller, S. M., Stark, R., Steins-Loeber, S., & Potenza, M. N. (2025). Current interpretations of the I-PACE model of behavioral addictions. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 14(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2025.00020

Brand, M., Rumpf, H.-J., Demetrovics, Z., Müller, A., Stark, R., King, D. L., Goudriaan, A. E., Mann, K., Trotzke, P., Fineberg, N. A., Chamberlain, S. R., Kraus, S. W., Wegmann, E., Billieux, J., & Potenza, M. N. (2022). Which conditions should be considered as disorders in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) designation of “other specified disorders due to addictive behaviors”? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 11(2), 150–159. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00035

Brand, M., Wegmann, E., Stark, R., Müller, A., Wölfling, K., Robbins, T. W., & Potenza, M. N. (2019). The interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 104, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.032

Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders: An interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 252–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033

Caplan, S. E. (2002). Problematic internet use and psychosocial well-being: Development of a theory-based cognitive-behavioral measurement instrument. Computers in Human Behavior, 18(5), 553–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(02)00004-3

Caplan, S. E. (2010). Theory and measurement of generalized problematic internet use: A two-step approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1089–1097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012

Chen, G., & Lyu, C. (2024). The relationship between smartphone addiction and procrastination among students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 224, Article 112652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2024.112652

Clark, L. S. (2012). The parent app: Understanding families in the digital age. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199899616.001.0001

CNNIC. (2021). The 2020 China report on juveniles’ use of internet. https://www3.cnnic.cn/NMediaFile/2022/1201/MAIN1669871621762HOSKOXCEP1.pdf

Davis, R. A. (2001). Cognitive-behavioral model of pathological internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 17(2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00041-8

Dieris-Hirche, J., Bottel, L., Bielefeld, M., Steinbüchel, T., Kehyayan, A., Dieris, B., & te Wildt, B. (2017). Media use and internet addiction in adult depression: A case-control study. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 96–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.016

Fam, J. Y., Männikkö, N., Juhari, R., & Kääriäinen, M. (2022). Is parental mediation negatively associated with problematic media use among children and adolescents? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 55(2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000320

Fu, X., Liu, J., Liu, R.-D., Ding, Y., Hong, W., & Jiang, S. (2020). The impact of parental active mediation on adolescent mobile phone dependency: A moderated mediation model. Computers in Human Behavior, 107(19), Article 106280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106280

Gardner, B., Abraham, C., Lally, P., & de Bruijn, G.-J. (2012). Towards parsimony in habit measurement: Testing the convergent and predictive validity of an automaticity subscale of the Self-Report Habit Index. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9, Article 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-102

Gardner, B., De Bruijn, G.-J., & Lally, P. (2011). A systematic review and meta-analysis of applications of the self-report habit index to nutrition and physical activity behaviours. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 42(2), 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-011-9282-0

Gui, M., & Büchi, M. (2021). From use to overuse: Digital inequality in the age of communication abundance. Social Science Computer Review, 39(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439319851163

Hawk, S. T., Wang, Y., Wong, N., Xiao, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2023). “Youth‐focused” versus “whole‐family” screen rules: Associations with social media difficulties and moderation by impulsivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 33(4), 1254–1267. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12873

Hefner, D., Knop, K., Schmitt, S., & Vorderer, P. (2019). Rules? Role model? Relationship? The impact of parents on their children’s problematic mobile phone involvement. Media Psychology, 22(1), 82–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2018.1433544

Herrero, J., Rodríguez, F. J., & Urueña, A. (2023). Use of smartphone apps for mobile communication and social digital pressure: A longitudinal panel study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 188, Article 122292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122292

Herrero, J., Torres, A., Vivas, P., Arenas, Á. E., & Urueña, A. (2022). Examining the empirical links between digital social pressure, personality, psychological distress, social support, users’ residential living conditions, and smartphone addiction. Social Science Computer Review, 40(5), 1153–1170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439321998357

Holvoet, S., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Hudders, L., & Herrewijn, L. (2022). Predicting parental mediation of personalized advertising and online data collection practices targeting adolescents. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 66(2), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2022.2051511

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2017). Conceptualizing internet use disorders: Addiction or coping process? Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 71(7), 459–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12413

Kindt, S., Szász-Janocha, C., Rehbein, F., & Lindenberg, K. (2019). School-related risk factors of internet use disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), Article 4938. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244938

Lang, A. (2000). The limited capacity model of mediated message processing. Journal of Communication, 50(1), 46–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02833.x

LaRose, R. (2010). The problem of media habits. Communication Theory, 20(2), 194–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01360.x

LaRose, R., Lin, C. A., & Eastin, M. S. (2003). Unregulated internet usage: Addiction, habit, or deficient self-regulation? Media Psychology, 5(3), 225–253. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0503_01

Li, L., Gao, H., & Xu, Y. (2020). The mediating and buffering effect of academic self-efficacy on the relationship between smartphone addiction and academic procrastination. Computers & Education, 159, Article 104001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104001

Li, L., Shi, J., & Zhong, B. (2023). Good in arts, good at computer? Rural students’ computer skills are bolstered by arts and science literacies. Computers in Human Behavior, 140, Article 107573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107573

Li, Y., & Ranieri, M. (2013). Educational and social correlates of the digital divide for rural and urban children: A study on primary school students in a provincial city of China. Computers & Education, 60(1), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.08.001

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. J. (2008). Parental mediation of children’s internet use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52(4), 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150802437396

Lozano-Blasco, R., Robres, A. Q., & Sánchez, A. S. (2022). Internet addiction in young adults: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior, 130, Article 107201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107201

Meier, A. (2022). Studying problems, not problematic usage: Do mobile checking habit increase procrastination and decrease well-being? Mobile Media & Communication, 10(2), 272–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579211029326

Meier, A., & Reinecke, L. (2021). Computer-mediated communication, social media, and mental health: A conceptual and epirical meta-review. Communication Research, 48(8), 1182–1209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220958224

Misra, S., & Stokols, D. (2012). Psychological and health outcomes of perceived information overload. Environment and Behavior, 44(6), 737–759. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916511404408

Montag, C., Wegmann, E., Sariyska, R., Demetrovics, Z., & Brand, M. (2021). How to overcome taxonomical problems in the study of internet use disorders and what to do with “smartphone addiction”? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(4), 908–914. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.59

Morales-Álvarez, A., Valdés-Cuervo, A. A., & Parra-Pérez, L. G. (2025). Supportive parenting and adolescents digital citizenship behaviors: The mediating role of self-regulation. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 19(1), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2025-1-2

Moretta, T., & Wegmann, E. (2025). Toward the classification of social media use disorder: Clinical characterization and proposed diagnostic criteria. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 21, Article 100603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2025.100603

Oulasvirta, A., Rattenbury, T., Ma, L., & Raita, E. (2012). Habits make smartphone use more pervasive. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 16(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-011-0412-2

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Coyne, S. M., Fraser, A. M., Dyer, W. J., & Yorgason, J. B. (2012). Parents and adolescents growing up in the digital age: Latent growth curve analysis of proactive media monitoring. Journal of Adolescence, 35(5), 1153–1165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.03.005

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

Reinecke, L., Hartmann, T., & Eden, A. (2014). The guilty couch potato: The role of ego depletion in reducing recovery through media use. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 569–589. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12107

Ritchie, H. (2024, November 29). Australia approves social media ban on under-16s. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c89vjj0lxx9o

Seo, E. H., Yang, H.-J., Kim, S.-G., Park, S.-C., Lee, S.-K., & Yoon, H.-J. (2021). A literature review on the efficacy and related neural effects of pharmacological and psychosocial treatments in individuals with internet gaming disorder. Psychiatry Investigation, 18(12), 1149–1163. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2021.0207

Siebers, T., Beyens, I., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2024). The effects of fragmented and sticky smartphone use on distraction and task delay. Mobile Media & Communication, 12(1), 45–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579231193941

Soror, A. A., Hammer, B. I., Steelman, Z. R., Davis, F. D., & Limayem, M. M. (2015). Good habits gone bad: Explaining negative consequences associated with the use of mobile phones from a dual-systems perspective. Information Systems Journal, 25(4), 403–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12065

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65

Stodt, B., Brand, M., Sindermann, C., Wegmann, E., Li, M., Zhou, M., Sha, P., & Montag, C. (2018). Investigating the effect of personality, internet literacy, and use expectancies in internet-use disorder: A comparative study between China and Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(4), Article 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040579

Tokunaga, R. S. (2013). Engagement with novel virtual environments: The role of perceived novelty and flow in the development of the deficient self-regulation of internet use and media habits. Human Communication Research, 39(3), 365–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12008

Trafimow, D. (2018). The automaticity of habitual behaviours: Inconvenient questions. In B. Verplanken (Ed.), The psychology of habit (pp. 379–395). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97529-0_21

Tuckman, B. W. (1991). The development and concurrent validity of the Procrastination Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51(2), 473–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164491512022

Van Rooij, A., & Prause, N. (2014). A critical review of “internet addiction” criteria with suggestions for the future. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(4), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.3.2014.4.1

Vanden Abeele, M. M. P. (2021). Digital wellbeing as a dynamic construct. Communication Theory, 31(4), 932–955. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtaa024

Verplanken, B., & Wood, W. (2006). Interventions to break and create consumer habits. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25(1), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.25.1.90

Wartberg, L., Thomasius, R., & Paschke, K. (2021). The relevance of emotion regulation, procrastination, and perceived stress for problematic social media use in a representative sample of children and adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 121, Article 106788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106788

White, S. R., Rasmussen, E. E., & King, A. J. (2015). Restrictive mediation and unintended effects: Serial multiple mediation analysis explaining the role of reactance in US adolescents. Journal of Children and Media, 9(4), 510–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2015.1088873

Won, S., & Yu, S. L. (2018). Relations of perceived parental autonomy support and control with adolescents’ academic time management and procrastination. Learning and Individual Differences, 61, 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.12.001

Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2007). A new look at habits and the habit-goal interface. Psychological Review, 114(4), 843–863. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.843

Yang, Z., Asbury, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019). An exploration of problematic smartphone use among Chinese university students: Associations with academic anxiety, academic procrastination, self-regulation and subjective wellbeing. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(3), 596–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9961-1

Zhou, C. Y. (2024). Parenting with Chinese characteristics in the digital age: Chinese parents’ perspectives and parental mediation of children’s media use. International Journal of Communication, 18, 3292–3311. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/20882

Authors' Contribution

Jinghan Ma: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, software, visualization, writing—original draft. Yungeng Li: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, resources, validation, writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

March 12, 2025

Revisions received:

July 7, 2025

August 14, 2025

October 24, 2025

Accepted for publication:

October 29, 2025

Editor in charge:

Maèva Flayelle

Introduction

Smartphones are becoming an indispensable yet double-edged part of Chinese adolescents’ lives. A nationwide survey of 26,349 school-aged students aged 6 to 18 found that 90.7% accessed the internet via mobile phones, with 19.5% considering themselves very dependent or relatively dependent on the internet (CNNIC, 2021).

Despite the benefits of mobile phones in terms of learning, socializing, and entertainment, increasing evidence suggests that excessive reliance on mobile phones can have detrimental effects on various aspects of life (Billieux, Maurage et al., 2015). Although procrastination has been identified as a significant negative consequence of excessive smartphone use across different age groups, it is particularly concerning among adolescents, as it may interfere with task completion and efficiency, potentially hindering their personal prospects (Beutel et al., 2016; Chen & Lyu, 2024; L. Li et al., 2020; Steel, 2007). This issue has garnered attention from parents, educators, and relevant authorities. Recently, the parliament in Australia has approved a strict law to restrict children’s social media use (Ritchie, 2024). The legislation prohibits children under the age of 16 from accessing social media platforms, with no exceptions granted even with parental consent. Tech companies that fail to comply may face significant fines. In China, the government has implemented regulations to strictly limit the adolescents’ time spent on online games and social media for leisure since 2021 (Hawk et al., 2023). For instance, users registered as minors are restricted to a maximum of 1.5 hours of gaming per day and are prohibited from accessing online games between 10:00 p.m. and 8:00 a.m. At the family level, 54.0% of parents require their children’s online activities to be supervised to ensure they do not access inappropriate content and to prevent personal information leakage and online fraud, while 79.7% of parents make agreements with their children to allow moderate online entertainment (CNNIC, 2021).

Adolescent digital use and its negative consequences have long been a classic research topic. Existing studies predominantly adopt frameworks of “addiction”, “internet use disorders” (IUDs), “problematic internet use” (PIU), and “overuse” to analyze patterns, predictors, and outcomes of digital use. However, each of these frameworks has specific boundaries and typical contexts, and much prior research has focused primarily on general internet use. Empirical investigations are still lacking regarding non-pathological yet still disruptive digital habits among adolescents—especially those that interfere with offline learning—and, in particular, a focus on external factors such as parental mediation and digital pressure remains rare. This study employs the approach of digital technology habits to explore the mechanism of how the mobile checking habit of middle school students correlates with offline procrastination.

Literature Review

Introduction of Digital Technology Habits and the Predictors of Mobile Checking Habit

The predictors and consequences of adolescent digital use remain a persistent topic of academic inquiry. A growing concern across these frameworks is identifying under what conditions and to what extent excessive use of digital technology results in detrimental outcomes.

Addiction has been one of the most widely used and traditional frameworks. Early discussions focused on demographical factors in the development of addictive behaviors (Dieris-Hirche et al., 2017). Some also considered the detrimental consequences of addiction on academic performance and daily functioning, particularly among adolescents (Lozano-Blasco et al., 2022). However, early conceptualizations of digital addiction faced criticism for their theoretical and definitional ambiguity (Caplan, 2002). Other scholars contended that this framework overpathologized some daily activities while neglecting specific internet use behaviors (Billieux, Schimmenti et al., 2015; Van Rooij & Prause, 2014). Nonetheless, it is undeniable that some specific types of digital overuse clearly exhibit addictive characteristics and warrant classification as behavioral disorders. Recent clinical psychology research has provided compelling evidence linking gaming addiction to neurobiological correlates, and has reviewed clinical trials involving pharmacological and psychosocial treatments (Seo et al., 2021). Brand et al. (2022) proposed meta-level criteria to define social-network-use disorder as an addictive behavior. These criteria suggest that a behavior may be classified as an addiction if (1) it is linked to functional impairment through clinical evidence, (2) it can be explained through established addiction theories, and (3) empirical studies support its psychological mechanisms (Brand et al., 2022). This direction reflects a more cautious and evidence-based approach to establishing diagnostic standards for digital addiction. As scholars have argued, labeling digital use as addiction without sufficient theoretical and clinical justification risks theoretical inconsistency, hinders the development of theory, and blurs the procedures of diagnosis (Kardefelt-Winther, 2017).

While the framework of addiction remains prevalent in international scholarship, some researchers argue that digital addiction or use disorder may not always align with the diagnostic criteria used for substance-related addictions and often displays unique clinical characteristics (Kardefelt-Winther, 2017; Moretta & Wegmann, 2025). To explore specific patterns of digital use, more recent studies have shifted to the concept of internet use disorders (IUDs; Brand et al., 2016). Some researchers have extended the scope of IUDs from content-specific disorders to device- and app-specific disorders, emphasizing the importance of usage context (Montag et al., 2021). In line with addiction research, IUD studies have identified the psychological and neurobiological mechanisms underlying disorders like gaming disorder and social media disorder, offering clear clinical features and diagnostic criteria (Brand et al., 2024; Moretta & Wegmann, 2025). Although many empirical studies have examined risk factors among student populations, findings remain relatively fragmented (Bouna-Pyrrou et al., 2018; Kindt et al., 2019; Stodt et al., 2018). To provide a systematic explanation of the psychological and neurobiological processes involved in IUDs, Brand et al. (2016, 2019) proposed the Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. This model integrates personal characteristics (e.g., psychopathology, individual personality traits, social cognitions, and motivations), situational cues, cognitive responses, and reduced executive control into a dynamic framework for understanding the formation and maintenance of IUDs. The model outlines a staged process of disorder development, distinguishing core variables and their interactions. Recent research has also extended the I-PACE model to neurocognitive studies and diverse behavioral addictions, further proposing targeted interventions (Bernstein et al., 2023; Brand et al., 2019). The increasing precision in defining diagnostic criteria and boundaries of the model represents a valuable shift. More importantly, they offer structured approaches for analyzing problematic behaviors, facilitating both theoretical refinement and clinical application.

Similarly, the concept of PIU better encompasses various maladaptive internet use patterns based on the association with specific internet content (Davis, 2001). It is characterized by negative psychological, social, and professional consequences, as well as feelings of obsession and anxiety when access to the internet is restricted or unavailable (Van Rooij & Prause, 2014). Similar to the addiction framework, PIU has been considered to be influenced by demographic factors, internet use patterns, and other problematic behaviors (Caplan, 2010). While PIU emphasizes impairments in daily functioning, it avoids the label of addiction and the necessity of meeting clinical diagnostic criteria. However, this conceptual neutrality also leads to certain limitations. Specifically, PIU lacks clear criteria and may obscure meaningful distinctions of underlying mechanisms between different types of digital behaviors (Billieux, Schimmenti et al., 2015; Vanden Abeele, 2021).

Studies employing concepts like “overuse” or “overload” might circumvent overpathologizing criticisms but risk falling into a technophobia trap, presupposing that the use of digital technology inevitably leads to negative effects (Meier, 2022). Consequently, such research often measures the frequency and duration of internet use. However, screen time alone fails to capture the psychological or functional impairments associated with excessive use. Moreover, “screen time” often lacks clear conceptual boundaries and is highly context-dependent. It does not distinguish between harmful and non-harmful contexts. For instance, prolonged internet use may be problematic during studying or driving but not necessarily during leisure or recreational activities (Misra & Stokols, 2012).

In order to investigate forms of technology use that may not reach pathological levels but still lead to negative consequences in daily life, some scholars have introduced the concept of digital technology habits. This perspective views repetitive digital use as an unconscious behavior (Bayer & Campbell, 2012), involving four psychological characteristics that do not co-occur and are independently modifiable through context, instruction, or intention: lack of intentionality, lack of controllability, lack of attention, and lack of awareness (LaRose, 2010). Habits are formed through the repetition and reinforcement of behavior in stable environments, and since strong habits are associated with simple, shallow decision rules, people with strong habits tend to perform habitually practiced actions automatically (Verplanken & Wood, 2006). Once formed, habits remain relatively stable and are closely linked to the frequency of behaviors, jointly determining media behavior along with intention (Gardner et al., 2011).

The digital technology habits approach refrains from pathologizing digital technology and instead focuses on specific behaviors. It assumes a more neutral position to investigate both positive and negative relationships with digital technologies of individuals (Vanden Abeele, 2021), especially considering that digital technology has become an inseparable part of young people’s lives. Empirical evidence also suggests that, in certain cases, young people’s digital media engagement can enhance their technical expertise, support their friendships, and contribute to identity construction (Clark, 2012). This approach has several advantages: it can be applied to a broad range of media and communication technology-related issues beyond psychological diagnoses (Meier & Reinecke, 2021). It addresses both healthy and unhealthy behaviors while considering contextual factors that influence the assessment of habits (Meier, 2022). In terms of measurement, this approach does not need to measure frequency or duration as “overuse” studies do (Bayer & Campbell, 2012). It is important to note that the habit framework is not entirely separate from the addiction framework. The transition from addiction to habit formation and consumption has been a longstanding tradition in addiction research (Brand et al., 2025). As Brand et al. (2019) suggested, in the later stages of addictive behavior development, the relationship between affective-cognitive responses and decision-making becomes increasingly automatic, potentially resulting in habitual, cue-driven behaviors. Specifically, stimulus-related inhibitory control has been identified as a critical mechanism in the habitual expression of addictive behaviors during these later stages. This perspective suggests that analytical frameworks developed for addiction may also offer valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying habit formation.

From the perspective of habits, some scholars have focused on the specific form of digital technology habit related to smartphone use, known as mobile checking habit. This refers to automated behaviors where the device is quickly opened to check the standby screen or information content in a specific application (Oulasvirta et al., 2012). This is a typical concept because it can be beneficial in certain situations (e.g., chatting with friends when feeling lonely) but harmful in others, such as unconsciously checking the phone while driving (Meier, 2022).

In the influential I-PACE model, beyond dispositional vulnerability factors, emotional and cognitive responses to internal and external stimuli are identified as key predictors of internet use disorders and addictive behaviors (Brand et al., 2016, 2019, 2025). Similarly, according to the theory of habits as automatized behaviors, habits are triggered by features of the context, including performance location, preceding actions in a sequence, and particular people (Wood & Neal, 2007). Technology habits, especially mobile checking, are triggered by various cues involving timing, spatial, technical, and mental cues (Bayer et al., 2016; Oulasvirta et al., 2012). As portable technologies, smartphones increase the opportunities for repeat behavior and allow for a greater variety of cues associated with a habit (Bayer & LaRose, 2018). As an important situational cue of the mobile checking habit, social digital pressure (SDP) is also based on the perceived social norm of constant availability, which has been growing with the ubiquity of mobile connectivity and accessibility of apps and may also affect users’ digital well-being (Herrero et al., 2023). Brand et al.’ (2016) review also highlighted that perceived stress may influence cognitive processing and reactions, potentially prompting individuals to engage in internet use as a coping strategy. Specific goals related to avoidance or reduction of negative affect are activated more automatically in response to external stimuli or internal triggers, such as stress or negative emotions (Brand et al., 2025). The concept of SDP posits that social environments exert influence on individuals’ online behaviors and shape their digital engagement (Gui & Büchi, 2021). According to Brand et al. (2025), habit formation is a general process reinforced by rewarding behaviors, whereby stimulus–response associations are gradually strengthened over time. On the one hand, users can check out the latest updates and immediately respond and engage with the content, thereby gaining interactional reward values (Oulasvirta et al., 2012). On the other hand, there is an implicit expectation for us to maintain constant accessibility and digital connectivity with others, which is deeply rooted in the nature of the digital social environment (Bayer et al., 2016; Herrero et al., 2022). Herrero et al. (2022) examined a positive statistical relationship between SDP and smartphone addiction. Przybylski et al. (2013) also found that people with high fear of missing out (FoMO) tended to check their smartphones more frequently (Przybylski et al., 2013). It is precisely through this combination of positive (i.e., the desire to stay connected) and negative (i.e., the fear of being excluded) reinforcement that the likelihood of performing certain behaviors in specific contexts increases.

In addition, as Wood and Neal (2007) suggested, although habits often served and influenced goals, they could also conflict with goals. Habits did not merge readily with conflicting goals. However, people could effectively overcome habit disposition and prevent it from manifesting in behavior by controlling habit cues. In other words, individuals’ self-regulation plays a crucial role in the interaction of habits and goals (Wood & Neal, 2007). Self-regulation is crucial for individuals to monitor their behavior, evaluate the potential harm, and adjust their emotional, cognitive, and behavioral response (Soror et al., 2015). LaRose (2010) contended that the persistence of deficient self-regulation over time contributes to the formation of media habits. This was also confirmed by Tokunaga (2013), who found that when individuals experience deficient self-regulation, internet use becomes an end and not a means to an end, and the conditioned responses associated with such use lead to automaticity in usage behavior. Under the approach of addiction and PIU, many studies have confirmed a negative relationship between self-regulation and problematic digital use. For instance, Billieux, Maurage et al. (2015) found that uncontrolled urges and deregulated use significantly predicted problematic mobile phone use. In the Chinese context, research has shown that problematic smartphone use was negatively predicted by self-regulation (Yang et al., 2019). According to Brand et al.’ (2025) argumentation, habitual and compulsive behaviors reflect a transition from controlled to automatic processes, highlighting diminished self-regulation as a key mechanism in their persistence.

Based on this, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1: SDP (a) positively predicts mobile checking habit, and deficient self-regulation (b) positively predicts mobile checking habit.

How Does Mobile Checking Habit Influence Offline Study Habit? The Reproduction of Procrastination

People sometimes find repetitive habitual use annoying, but at other times, they do not consider habitual use negatively, even if it is very frequent (Oulasvirta et al., 2012). In an academic performance context, a recent meta-analysis has already confirmed the positive relationship between smartphone addiction and procrastination, especially among students (Chen & Lyu, 2024). Procrastination is defined as the voluntary delay of an intended course of action despite expecting to be worse off for the delay (Steel, 2007). Procrastination is particularly common among young people and often leads to lower academic performance (Beutel et al., 2016; Steel, 2007).

Empirical studies have shown that mobile phone interference in life, especially overindulgence in social interactions, can have dire consequences on task performance and psychological well-being (Yang et al., 2019). L. Li et al. (2020) demonstrated that individuals tended to delay facing difficult tasks while indulging in entertaining experiences provided by their smartphones. For students and adolescents, as suggested by Wartberg et al. (2021), problematic smartphone use was associated with increased procrastination, which occurred not only in educational and school settings but also in various other daily situations. In the context of digital technology habits, research has found that the mobile checking habit significantly predicts procrastination (Meier, 2022).

Theoretically, the limited capacity theory suggests that individuals possess finite cognitive resources and task performance deteriorates as these resources are increasingly demanded. Engaging in online entertainment activities may consequently impede academic pursuits (Lang, 2000). Davis (2001) argued that since learning or working was cognitively stressful, people were more likely to engage in relaxing activities to avoid these pressures, such as using the internet. Specifically, for fragmented and sticky smartphone use, which can be triggered internally via checking habit, the selective and immersive attention to the smartphone may cause distraction, thereby suppressing attention towards other tasks and leading to endless dwelling on the smartphone (Siebers et al., 2024).

In summary, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2: Mobile checking habit positively predicts academic procrastination.

The Moderation Role of Parental Intervention

Bourdieu (2013) has pointed out the relationship between the reproduction of individual practices and objective structures such as the family. The widespread use of digital devices among adolescents has raised concerns among parents, who often make considerable efforts to manage their adolescents’ screen habits (Hawk et al., 2023). Due to parents’ desire to mitigate the adverse consequences associated with unregulated digital usage, they frequently employ strategies such as implementing rules that promote responsible utilization of digital technology (Livingstone & Helsper, 2008). As discussed earlier, screen time is an inadequate measure of problematic use; thus, the effectiveness of parental mediation depends not merely on the rigidity of time restrictions, but on how and in what context these limits are implemented. Three forms of parental mediation have usually been discussed: active mediation, restrictive mediation, and co-viewing to influence their child’s media use behaviors (Padilla-Walker et al., 2012).

In the context of China, a large-scale survey shows that Chinese parents often regulate their children’s smartphone use through restrictive practices (CNNIC, 2021). Restrictive mediation involves establishing a range of regulations to limit adolescents’ access, opportunities, content, and time spent with their digital devices (Holvoet et al., 2022). In contrast to restrictive mediation, active mediation refers to parental discussion regarding the media, both in terms of time and content. This method encourages adolescents to become critical thinkers (Padilla-Walker et al., 2012).

Many studies have attempted to analyze the impact of different forms of parental mediation on children’s behavior. Empirical research in educational psychology has shown that perceived parental autonomy support, compared to perceived control, helps students develop better time management plans and reduces procrastination (Won & Yu, 2018). Empirical evidence also suggests that adolescents are more likely to exhibit prosocial behaviors when parents provide multiple options and consider their feelings (Morales-Álvarez et al., 2025). In the context of problematic digital technology use, a meta-analysis indicated that, compared to active mediation and co-using mediation, restrictive mediation is effective in reducing problematic media use in certain subgroups, although this effect diminishes with age (Fam et al., 2022).

Research suggests that while restrictive mediation can mitigate the risk of PIU to some extent, it might also provoke resistance from adolescents, potentially counteracting the effects of parental intervention (White et al., 2015). However, some studies have produced inconsistent findings. Hawk et al. (2023) found that attempts to limit adolescents’ screen use do not always predict less problematic online behavior and might even lead to family conflicts. Some scholars agree that merely imposing restrictions on children’s mobile phone use does not effectively prevent overinvolvement with the phone (Hefner et al., 2019). Meanwhile, other studies have highlighted the benefits of active mediation. Research has shown a negative association between active mediation and problematic mobile phone involvement, emphasizing the importance of talking with children about their behaviors, questions, emotions, and needs, as well as showing a sense of care (Hefner et al., 2019). A study on Chinese adolescents indicated that parental active mediation might reduce children’s phone dependency by changing their self-regulatory attitudes toward phone use through the communication process between parents and children (Fu et al., 2020).

Despite numerous studies have described the effects of different forms of parental mediation on children’s smartphone addiction or problematic use, there has been limited focus on how these mediations influence the impact of digital technology habits on offline learning performance. As a result, this study considers parental intervention as a moderation variable, exploring the moderation effects of both intervention approaches on the path from mobile checking habit to procrastination. The following hypotheses are proposed:

H3a: Active parental mediation moderates the relationship between mobile checking habit and academic procrastination, such that the positive effect is weaker when active parental mediation is higher.

H3b: Restrictive parental mediation moderates the relationship between mobile checking habit and academic procrastination, such that the positive effect is weaker when restrictive parental mediation is higher.

H4: The moderating effect of active parental mediation is stronger than that of restrictive parental mediation in attenuating the positive relationship between mobile checking habit and academic procrastination.

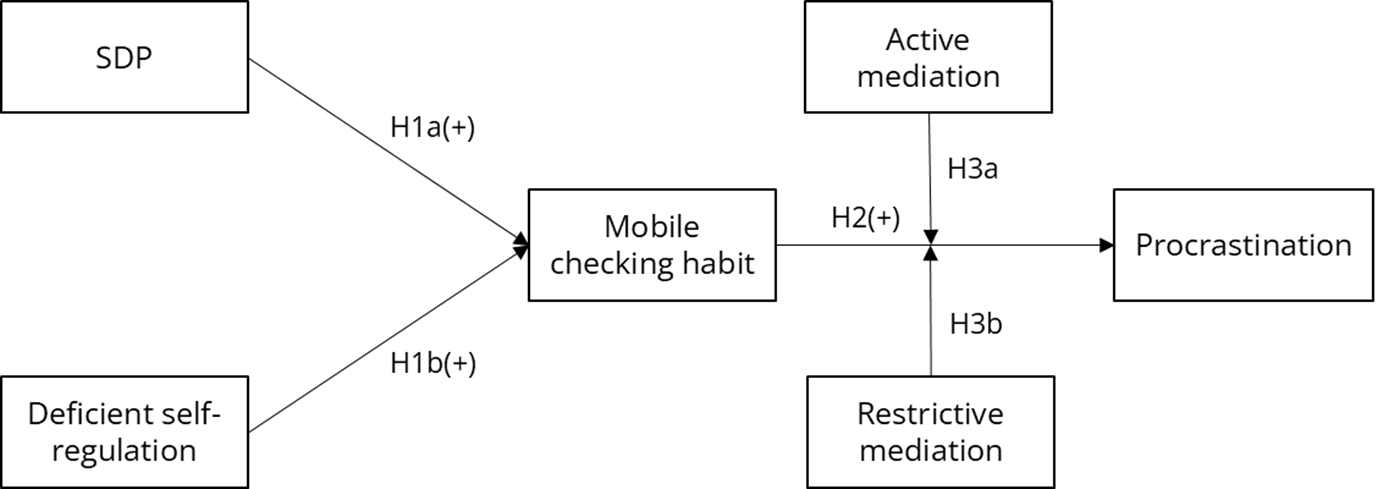

Based on the above hypotheses, this study establishes the following model:

Figure 1. Hypothesis Model of the Study.

Methods

Data Collection

We surveyed from February 1st to 8th, 2023, targeting middle school students. We utilized a purposive sampling strategy to distribute our questionnaire in six middle schools in Liangshan in Southwest China. Using an online sample size calculator (www.calculator.io), we conducted an a priori power analysis with a 99% confidence level, a 5% margin of error, and an assumed population proportion of 50%, resulting in a minimum required sample size of 666. A total of 831 questionnaires were collected. After manually filtering out non-valid responses and respondents over 20 years old. The final sample size included in the analysis was 810 (n = 810). This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee for Human-Related Scientific Research at our university (Number: H20230332I), and written informed consent was obtained from each participant after the procedure had been fully explained.

In this survey, respondents’ ages ranged from 10 to 20 years (M = 14.69, SD = 2.08), with 40.86% male (n = 331) and 59.14% female (n = 479). Given that some of the surveyed schools are located in impoverished mountainous regions, students often begin their education at a later age. As a result, it is not uncommon to find 20-year-old students still attending middle school. Most respondents’ monthly household incomes fall within 2001 to 5000 CNY (54.32%, n = 440). Additionally, most reported daily smartphone screen time (in the past month) was 0.5–2 hours (31.11%, n = 252).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics.

|

Variable |

Proportion |

SD |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|

Gender |

||||

|

1 = Male |

40.86% |

|||

|

0 = Female |

59.14% |

|||

|

Age |

14.69a |

2.081 |

10 |

20 |

|

Average daily smartphone use in the past month |

||||

|

1 = Less than 0.5 hour |

12.84% |

|||

|

2 = 0.5–2 hours |

31.11% |

|||

|

3 = 2–4 hours |

25.68% |

|||

|

4 = 4–6 hours |

15.93% |

|||

|

5 = 6–8 hours |

7.16% |

|||

|

6 = More than 8 hours |

7.28% |

|||

|

Monthly household income |

||||

|

1 = 2000 CNY or less |

21.60% |

|||

|

2 = 2001–5000CNY |

54.32% |

|||

|

3 = 5001–10000CNY |

19.01% |

|||

|

4 = More than 10001 CNY |

5.06% |

|||

|

Note. a denotes the mean value for continuous variables. |

||||

Measures

Mobile Checking Habit

This study adopted the Self-Report Behavioural Automaticity Index (SRBAI) developed by Gardner et al. (2011, 2012) to measure habit and translated it into Chinese, using a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) to assess respondents’ mobile checking habit. The scale included 4 items: I play with my smartphone automatically; I play with my smartphone without having to consciously remember; I play with my smartphone without thinking; I start playing with my smartphone before I realize I’m doing it

(M = 2.661, SD = 0.877, Cronbach’s α = .724).

Deficient Self-Regulation

Deficient self-regulation was measured in accordance with LaRose et al. (2003) and was adapted for the context of smartphones. This construct was intended to capture individuals’ difficulties in regulating their smartphone use, particularly with respect to cognitive preoccupation and compulsive use. Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). After removing two items with low standardized factor loadings, the final measurement included the following six items: My use of smartphone interferes with other activities; I get strong urges to play with my smartphone; I have to keep using the smartphone more and more to get my thrill; I feel my smartphone use is out of control; I would miss my smartphone if I could no longer use it; I often spend longer on the smartphone than I intend to when I start (M = 2.72, SD = 0.912, Cronbach’s α = .921).

Social Digital Pressure (SDP)

SDP was measured with three items from Gui and Büchi (2021) and was modified based on the Chinese context. To facilitate better comprehension and contextual relevance among adolescents in low-resource rural areas, we specified popular platforms in the items measuring SDP. The scale included three items: In my everyday life, my classmates and friends expect that I reply quickly to messages on WeChat or QQ; In my everyday life, my classmates and friends expect that I am capable of using various smartphone applications; and In my everyday life, my classmates and friends expect me to be active on WeChat or QQ, which were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree; M = 2.728, SD = 0.854, Cronbach’s α = .818).

Academic Procrastination

Consistent with the methods of Reinecke et al. (2014) and Meier (2022), academic procrastination was measured using Tuckman’s (1991) 5-point procrastination scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), by asking: I put off homework that I intended to do; I had important schoolwork to get done, but instead did things that were more fun; I delayed starting to study or finishing my homework; I play with my smartphone after school to find an excuse for not doing something else (M = 2.687, SD = 0.896, Cronbach’s α = .829).

Parental Mediation

Parental mediation was measured from Benrazavi’s (2015) research, and we adapted the narrative to the Chinese context. Both active and restrictive mediation were measured using 5-point scales (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Active mediation was measured by asking: My parents encourage me to use my smartphone to independently explore and learn new things; My parents explain to me when I can use my smartphone and when I should not; My parents explain to me about proper smartphone using habits (M = 3.474, SD = 0.878, Cronbach’s α = .737). Restrictive intervention was measured by asking: I have to hand over my smartphone to my parents at a fixed time; My parents impose specific times for me to use my smartphone; My parents impose rules on what I can and cannot do with my smartphone; My parents impose rules on what content I can and cannot view on my smartphone (M = 3.375, SD = 0.993, Cronbach’s α = .893).

Analysis

This study used Stata 14.0 to test the structural equation model, using the maximum likelihood estimation. Gender, age, monthly household income, and average daily smartphone use in the past month were included as control variables in the structural equation model tests. Additionally, this study conducted hierarchical regression analysis to examine the moderation effects of active parental mediation and restrictive parental mediation on the relationship between mobile checking habit and procrastination, while controlling for control variables. Variables were mean-centered prior to the moderation analysis to reduce multicollinearity and facilitate the interpretation of interaction effects.

Results

Structural Equation Modelling

In order to further examine the reliability and validity of our measurements, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on all composite scales in the study (see Table 2). The results show that the reliability and validity of all measurements are above acceptable standards. Meanwhile, to assess multicollinearity among predictor variables in the structural model, variance inflation factor (VIF) values were examined. All VIF values were below the commonly accepted threshold of 5.0, indicating no multicollinearity issue in the model. We also examined the fit indices of the structural equation model, and the results indicated an acceptable overall fit: χ²/df = 3.792, RMSEA = .059, CFI = .958,

TLI = .933.

Table 2. Constructs Reliability and Validity.

|

Constructs |

CR |

AVE |

MSVs |

ASVs |

|

Mobile checking habit |

0.725 |

0.468 |

0.291 |

0.212 |

|

Self-regulation |

0.922 |

0.664 |

0.473 |

0.321 |

|

Social digital pressure |

0.820 |

0.605 |

0.199 |

0.138 |

|

Academic procrastination |

0.827 |

0.548 |

0.473 |

0.294 |

|

Note. CR: composite reliability; AVE: average variance extracted; MSV: maximum shared variance; ASV: average shared variance. Acceptable convergent validities indicate that the following criteria were met: for each construct (a) the composite reliability was greater than .50; (b) the square root of average variance extracted (AVE) was larger than .50; (c) the composite reliability was larger than AVE; an acceptable discriminant validity for each construct means that the AVE was greater than the maximum shared variances (MSVs) and the average shared variances (ASVs). |

||||

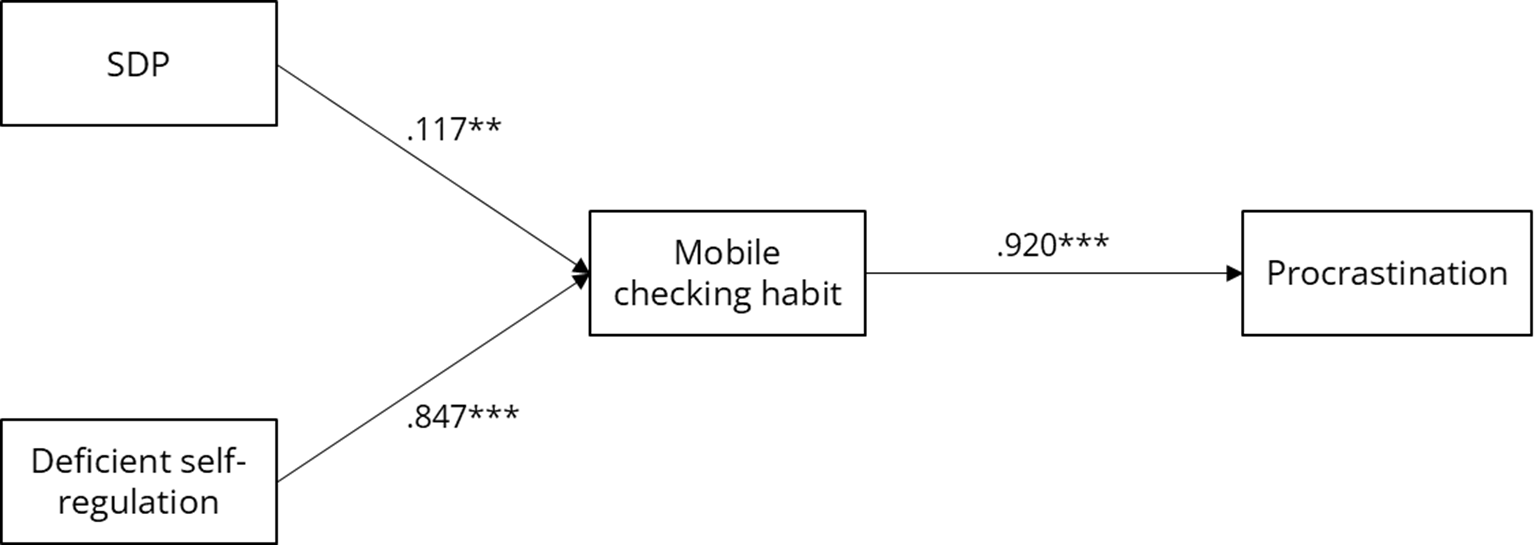

As shown in Table 2, SDP positively predicted the strength of mobile checking habit (β = .117, p < .01). Additionally, deficient self-regulation of adolescents was positively related to the strength of mobile checking habit (β = .847, p < .001). Therefore, both H1a and H1b were supported. Meanwhile, a positive relationship was found between the strength of mobile checking habit and procrastination among adolescents (β = .920, p < .001), confirming H2 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Structural Equation Model With Standardized Path Estimate.

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Analysis of Moderation Effects

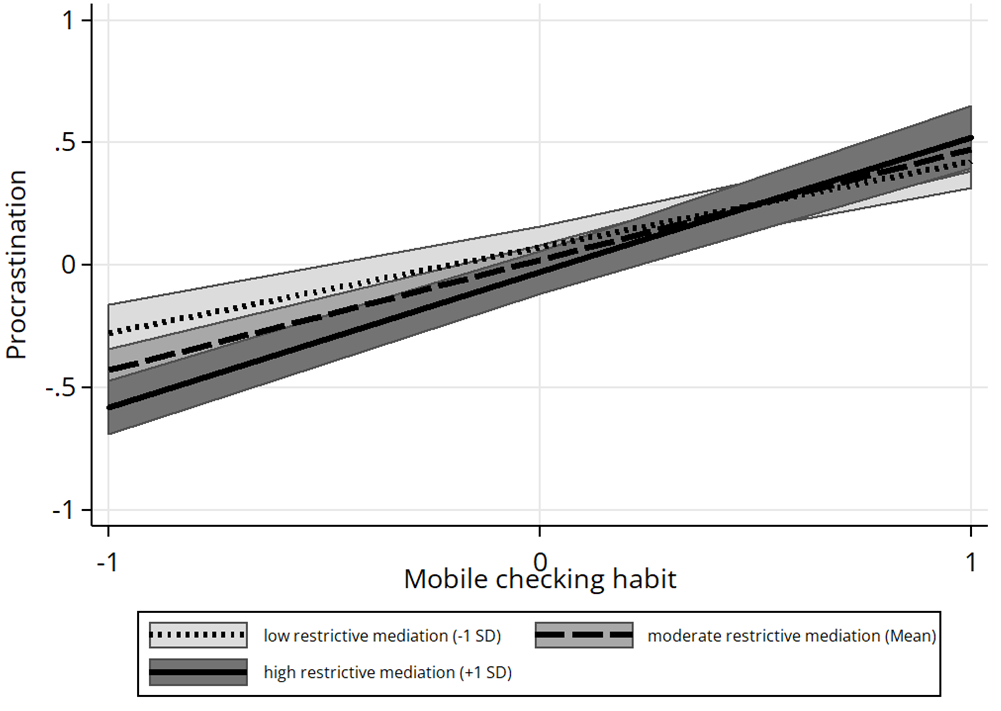

The normality of residuals was further assessed using Q-Q plots for each step of the hierarchical regression. In all models, the residuals were approximately aligned along the diagonal line, indicating no substantial deviation from normality. The final results of hierarchical regression analysis were shown in Table 3 and 4. Model 1 included control variables and main predictors (mobile checking habit). Model 2 added the moderator (parental mediation). Model 3 further introduced the interaction terms. The results indicated that for active parental mediation, the interaction term was not significant after adding the moderation variable, suggesting that active parental mediation did not have a significant moderation effect on the relationship between mobile checking habit and procrastination. However, for restrictive parental mediation, the interaction term was significant after adding the moderation variable, indicating that restrictive parental mediation significantly moderated the path between mobile checking habit and procrastination (β = .101, p < .001). The R² increased from .299 to .315, resulting in an f² of .023, which indicates a small but meaningful moderation effect.

We then plotted the simple slopes for mobile checking habit predicting procrastination at three levels of restrictive parental mediation (as shown in Figure 3). The positive effect of the mobile checking habit on procrastination became stronger with higher levels of restrictive parental mediation. Specifically, when restrictive parental mediation reached a high level (+1SD), the influence of mobile checking habit on procrastination became more pronounced; conversely, when restrictive parental mediation was at a low level (−1SD), the effect of mobile checking habit on procrastination was weaker.

Table 3. Moderation Effect of Active Parental Mediation on the Relationship Between Mobile Checking Habit and Procrastination.

|

Predictors |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||

|

Standardized β |

SE |

Standardized β |

SE |

Standardized β |

SE |

|

|

Gender |

.060 |

0.061 |

.042 |

0.060 |

.041 |

0.060 |

|

Age |

.020 |

0.016 |

.022 |

0.015 |

.021 |

0.015 |

|

Monthly household income |

−.062 |

0.039 |

−.049 |

0.038 |

-.051 |

0.038 |

|

Average daily smartphone use |

.112*** |

0.025 |

.110*** |

0.025 |

.112*** |

0.025 |

|

Mobile checking habit |

.445*** |

0.033 |

.438*** |

0.033 |

.442*** |

0.033 |

|

Active parental mediation |

— |

— |

−.133*** |

0.029 |

−.129*** |

0.030 |

|

Interaction |

— |

— |

— |

— |

.030 |

0.023 |

|

R² |

.296 |

.313 |

.314 |

|||

|

Adjusted R² |

.291 |

.308 |

.308 |

|||

|

F |

F (5,804) = 67.44, p < .001 |

F (6,803) = 60.96, p < .001 |

F (7,802) = 52.54, p < .001 |

|||

|

Note. ***p < .001. |

||||||

Table 4. Moderation Effect of Restrictive Parental Mediation on the Relationship Between Mobile Checking Habit and Procrastination.

|

Predictors |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||

|

Standardized β |

SE |

Standardized β |

SE |

Standardized β |

SE |

|

|

Gender |

.060 |

0.061 |

.061 |

0.060 |

.047 |

0.060 |

|

Age |

.020 |

0.016 |

.015 |

0.016 |

.015 |

0.016 |

|

Monthly household income |

−.062 |

0.039 |

−.060 |

0.039 |

−.057 |

0.038 |

|

Average daily smartphone use |

.112*** |

0.025 |

.102*** |

0.026 |

.105*** |

0.025 |

|

Mobile checking habit |

.445*** |

0.033 |

.441*** |

0.033 |

.452*** |

0.033 |

|

Restrictive parental mediation |

— |

— |

−.063 |

0.032 |

−.051 |

0.032 |

|

Interaction |

— |

— |

— |

— |

.101*** |

0.023 |

|

R² |

.296 |

.299 |

.315 |

|||

|

Adjusted R² |

.291 |

.294 |

.309 |

|||

|

F |

F (5,804) = 67.44, p < .001 |

F (6,803) = 57.03, p < .001 |

F (7,802) = 52.64, p < .001 |

|||

|

Note. ***p < .001. |

||||||

Figure 3. Moderation Effect of Restrictive Parental Mediation.

Discussion

This study examined the factors associated with the formation of mobile checking habit among Chinese adolescents and their relationship with procrastination, focusing on the moderating effects of two forms of parental mediation in this relationship. Our results suggested that both deficient self-regulation and SDP were positively associated with the development of mobile checking habit among Chinese adolescents. Additionally, active parental mediation did not moderate the association between mobile checking habit and procrastination. On the contrary, restrictive parental mediation appeared to be linked with a stronger association between mobile checking habit and negative outcomes.

Firstly, this study focuses on how a specific form of smartphone use habit influences offline behavior under conditions of ubiquitous connectivity. Our results indicated a strong association between mobile checking habit and procrastination among Chinese adolescents, and it was consistent with findings from previous studies conducted among adults and young people or in other regions (Meier, 2022; Yang et al., 2019). As Oulasvirta et al. (2012) suggested, compared to other devices, smartphones were significantly more pervasive in everyday life due to being carried around, and as a result, checking habit may represent a key component of behavior driving smartphone use. As smartphones increasingly integrate into the daily lives of Chinese adolescents, using them to watch short videos, play games, and chat provides a rich online experience but also poses potential obstacles to offline learning. Spending time on school tasks is less attractive than engaging in online activities, and their deficient control or impulse control difficulties were associated with greater procrastination tendencies in school tasks (Wartberg et al., 2021). Considering digital technology has undeniably become a crucial means for adolescents to express themselves and engage in diverse social interactions. The challenges they face are not just a matter of whether to use smartphones, but a matter of when, where, and whether they can disconnect—a balance between autonomy and control (Vanden Abeele, 2021). As Kardefelt-Winther (2017) suggested, in some cases it may be more meaningful for research purposes to examine how problematic technology use relates to individuals’ everyday lives rather than focusing narrowly on diagnostic symptoms.

Secondly, this study is guided by the theory of habits as automatized behaviors and draws upon insights from addiction and internet use disorder research to examine how internal and external stimuli shape the formation of mobile checking habit. We found that SDP, which represented an implicit expectation to maintain constant accessibility and digital connectivity with others, was found to be associated with adolescents’ mobile checking habit as a situational cue (Bayer et al., 2016). On the one hand, adolescents’ mobile checking may be initially guided by imitation purposes or triggered by social media messages from peers, and mobile checking habit can be developed as the mobile checking repeating and becomes integrated with daily context cues (Wood & Neal, 2007). On the other hand, considering the diversity of smartphone use, adolescents who cannot participate in sharing digital activities or respond to social media messages in time may face peer exclusion. As Wood and Neal (2007) suggested, habit responding was activated by the diffuse motivation that was tagged onto performance context when people repeatedly experience rewards. In such circumstances, adolescents feel pressure to meet the digital connectivity expectations of their peers to become more popular within the group and gain interactional value (Oulasvirta et al., 2012). This further supports the goal-directed nature underlying seemingly automatic habits. In the context of this study, the formation of adolescents’ mobile checking habit is shaped by cue-response associations and reward contingencies within their environment. Anticipated positive and negative outcomes repeatedly reinforce specific behavioral responses in particular contexts (Brand et al., 2025).

Our results also indicated that deficient self-regulation was positively associated with adolescents’ mobile checking habit. This finding is well-grounded and aligns with a large body of empirical evidence (e.g., LaRose, 2010; Tokunaga, 2013). Notably, the joint effects of deficient self-regulation and SDP observed in this study also corroborate Brand et al.’ (2025) assertion that the combination of positive and negative reinforcement, along with reduced self-control, may contribute to the development of habitual behaviors. Our findings also highlighted the importance of making adolescents aware of the conflict between their goals and habits, encouraging them to actively adjust their behavior and control negative outcomes (Wood & Neal, 2007). Of course, this is challenging. As shown in the study by Chen and Lyu (2024), students of different age groups exhibited varying levels of self-control ability: even adults may face difficulties in controlling the negative consequences of problematic smartphone use.

Thirdly, neither form of parental mediation showed evidence of buffering the observed relationship between mobile checking habit and procrastination in our model. We confirmed that restrictive, youth-centered digital regulation did not seem to be very effective in reducing procrastination (Hawk et al., 2023). On the contrary, a stronger level of restrictive parental mediation was associated with a more pronounced positive relationship between mobile checking habit and procrastination. There are probably two reasons for this phenomenon: First, in the context of hierarchical parent-child relationships in Chinese culture, and amid educational inequalities and intense academic competition, parents often attribute problematic media use to internet addiction. Consequently, they tend to adhere to traditional punitive and control-based education models (Zhou, 2024). Restrictive mediation, such as cutting off digital connections or confiscating phones, is still common in many regions. Some parents may even physically punish children for not following rules. It is worth noting that, due to the cross-sectional nature of our data, we cannot determine whether adolescents’ mobile checking habit had already escalated procrastination to a degree that prompted parental intervention through restrictive mediation. As Zhou (2024) pointed out, in certain situations, restrictive mediation may be both inevitable and necessary in the Chinese context—to safeguard children’s developmental potential by maximizing the benefits and minimizing the risks associated with digital media use. For adolescents, stricter discipline might provoke stronger rebellion. Second, the digital literacy of Chinese parents in low-resource rural areas remains low, preventing them from fully understanding the potential of digital technology and positively guiding their children in using smartphones for self-development (L. Li et al., 2023;

Y. Li & Ranieri, 2013). This explains the insignificant moderation effect of active parental mediation.

From the perspective of digital habit, there are steps previous studies have mentioned to control the negative consequences of mobile checking habit. Wood and Neal (2007) emphasized the importance of controlling habitual cues for behavioral change. They argued that combining effortful inhibition with the learning and execution of new, desired responses is most effective for promoting long-term behavior change. In addition to avoiding habitual cues (e.g., turning off notifications while studying), parents and youths should collaboratively foster alternative, healthy digital habits by reaching a consensus on when to disconnect (Soror et al., 2015). Moreover, to better cultivate self-regulation abilities in digital use, some studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of life skills training, addressing deficits in emotion regulation, stress, and procrastination, as well as training in time-management skills or personal effectiveness, particularly for procrastination associated with smartphone use (Wartberg et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2019). However, this likely requires the joint efforts of society, schools, and families. More importantly, future research should examine how interventions grounded in the habit formation process may help reduce the negative outcomes associated with adolescents’ mobile checking behavior.

This study has several limitations: First, relying entirely on self-reports, we only measured the intensity of adolescents’ mobile checking habit without assessing the frequency of the habit or the specific online content they accessed. Thus, we were unable to determine the association between habits and specific situational cues (Oulasvirta et al., 2012). Otherwise, since the questionnaire for this study was distributed in six schools within a city in a southwestern city of China, the sample lacks national representativeness, which could lead to sampling bias. Furthermore, while efforts were made to translate existing validated scales into Chinese with cultural appropriateness, the translated versions were not formally validated, which may affect the reliability and validity of the measurements. It is especially worth noting that several latent paths in the structural model were relatively large. This may suggest that, although the discriminant validity tests based on observed composite scores met conventional criteria, there remained limited discriminant validity at the measurement level. Future studies should complement Fornell–Larcker tests with more sensitive indices such as the HTMT ratio. The inflated path coefficients may also reflect the simplified model specification and the conceptual overlap among deficient self-regulation, mobile checking habits, and procrastination, which likely stem from shared underlying psychological mechanisms. Future research should continue to strengthen methodological rigor and robustness. Meanwhile, our study only employed cross-sectional data for analysis, which does not allow us to establish a causal relationship between mobile checking habit and procrastination, and it merely demonstrates a correlation between the two. It is also important to acknowledge the conceptual limitations of the habit framework, as recognized by scholars such as Trafimow (2018), who critiqued the definitional ambiguities of habit, particularly the difficulty of distinguishing between automatic and controlled behaviors, the mismatch between measuring behavioral intentions and contextualized actions, and the challenges of using mediation analysis to infer causality. Finally, this study did not take into account the role of specific technological cues, such as notifications, buzzes, and sounds, which have been shown to trigger repeat behavior as technology cues (Bayer et al., 2016; Bayer & LaRose, 2018; Herrero et al., 2022). Future research could further explore the role of these design elements in shaping mobile use habits.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Use of AI Services

The authors declare they have used AI services only for grammar correction and proofreading. They carefully reviewed all suggestions from these services to ensure the original meaning and factual accuracy were preserved.

Appendix

Table A1. Measurement Items of Key Constructs.

|

Constructs |

Code |

Items |

Reference |

|

Mobile checking habit |

MC1 |

I play with my smartphone automatically |

SRBAI by Gardner et al. (2011, 2012) |

|

MC2 |

I play with my smartphone without having to consciously remember |

||

|

MC3 |

I play with my smartphone without thinking |

||

|

MC4 |

I start playing with my smartphone before I realize I’m doing it |

||

|

Deficient self-regulation |

DS1 |

My use of smartphone interferes with other activities |

LaRose et al. (2003) |

|

DS2 |

I get strong urges to play with my smartphone |

||

|

DS3 |

I have to keep using the smartphone more and more to get my thrill |

||

|

DS4 |

I feel my smartphone use is out of control |

||

|

DS5 |

I would miss my smartphone if I could no longer use it |

||

|

DS6 |

I often spend longer on the smartphone than I intend to when I start |

||

|

Social digital pressure |

SD1 |

In my everyday life, my classmates and friends expect that I reply quickly to messages on WeChat or QQ |

Gui & Büchi (2021) |

|

SD2 |

In my everyday life, my classmates and friends expect that I am capable of using various smartphone applications |

||

|

SD3 |

In my everyday life, my classmates and friends expect me to be active on WeChat or QQ |

||

|

Academic procrastination |

AP1 |

I put off homework that I intended to do |

Tuckman (1991); Reinecke et al. (2014); Meier (2022) |

|

AP2 |

I had important schoolwork to get done, but instead did things that were more fun |

||

|

AP3 |

I delayed starting to study or finishing my homework |

||

|

AP4 |

I play with my smartphone after school to find an excuse for not doing something else |

||

|

Parental mediation |

APM1 |

My parents encourage me to use my smartphone to independently explore and learn new things |

Benrazavi (2015) |

|

APM2 |

My parents explain to me when I can use my smartphone and when I should not |

||

|

APM3 |

My parents explain to me about proper smartphone using habits |

||

|

RPM1 |

I have to hand over my smartphone to my parents at a fixed time |

||

|

RMP2 |

My parents impose specific times for me to use my smartphone |

||

|

RPM3 |

My parents impose rules on what I can and cannot do with my smartphone |

||

|

RPM4 |

My parents impose rules on what content I can and cannot view on my smartphone |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2026 Jinghan Ma, Yungeng Li