Caught in the daily scroll: How upward social comparison fuels daily anxiety during short video use among Chinese young adults

Vol.20,No.1(2026)

The rapid growth of short video platforms has raised concerns about their potential impact on young people’s mental health and well-being. However, the dynamic relationship between short video use and daily anxiety symptoms remains poorly understood. To address this gap, this study employed the experience sampling method (ESM) and dynamic structural equation modeling (DSEM) to examine their bidirectional relationship in a representative sample of Chinese young adults (N = 389; Mage = 20.38 years, SD = 1.44 years; 51.1% male). The results indicated that at the within-person level, there were no significant bidirectional effects between short video use (i.e., active use, passive use, or total use time) and daily anxiety symptoms. However, upward social comparison tendency moderated the within-person effect of passive short video use on subsequent anxiety symptoms. Specifically, individuals with higher levels of upward social comparison experienced greater anxiety during periods of increased passive short video use. In contrast, those with lower levels of upward social comparison experienced less anxiety under similar conditions. These findings suggest that while short video use may not directly contribute to daily anxiety, its psychological impact is contingent upon individual differences in social comparison. In particular, those prone to upward comparison may be more vulnerable to anxiety during passive consumption of short video content.

short video use; anxiety symptoms; dynamic structural equation model; experience sampling method; upward social comparison

Zhiwei Yang

Research Center of Mental Health Education, Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University, Chongqing

Zhiwei Yang is a master student in the Faculty of Psychology at Southwest University. His major research interests include social media addiction, short video use and their links to mental health problems.

Qian Nie

School of Journalism and Communication, Southwest University, Chongqing

Qian Nie is a lecturer in the School of Journalism and Communication at Southwest University. Her major research interests include children and adolescents' gaming disorder, mental health and psychological suzhi.

Xiaoqin Wang

School of Psychology, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua

Xiaoqin Wang is a lecturer at the School of Psychology, Zhejiang Normal University. Her research interests include emotion regulation neuroscience and clinical emotion disorders.

Halley M. Pontes

School of Psychological Sciences, Birkbeck, University of London, London

Halley M. Pontes is a psychologist, researcher, and Reader in Behavioural Addiction in the School of Psychological Sciences at Birkbeck, University of London. He is particularly focus on emerging disorders related to problematic use of technology such as gaming disorder, gambling disorder, social media addiction, work addiction, among others.

Zhaojun Teng

Research Center of Mental Health Education, Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University, Chongqing

Zhaojun Teng is a Professor in the Faculty of Psychology at Southwest University in China. His major research interests include video game usage and its links to aggression, bullying, addiction, and mental health problems.

Alonzo, R., Hussain, J., Stranges, S., & Anderson, K. K. (2021). Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 56, Article 101414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101414

Asparouhov, T., Hamaker, E. L., & Muthén, B. (2018). Dynamic structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 25(3), 359–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2017.1406803

Beeres, D. T., Andersson, F., Vossen, H. G. M., & Galanti, M. R. (2021). Social media and mental health among early adolescents in Sweden: A longitudinal study with 2-year follow-up (KUPOL Study). Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(5), 953–960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.042

Beyens, I., Pouwels, J. L., van Driel, I. I., Keijsers, L., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2020). The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent. Scientific Reports, 10(1), Article 10763. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67727-7

Boer, M., Stevens, G. W. J. M., Finkenauer, C., & van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M. (2022). The complex association between social media use intensity and adolescent wellbeing: A longitudinal investigation of five factors that may affect the association. Computers in Human Behavior, 128, Article 107084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107084

Boer, M., Van Den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Boniel-Nissim, M., Wong, S.-L., Inchley, J. C., Badura, P., Craig, W. M., Gobina, I., Kleszczewska, D., Klanšček, H. J., & Stevens, G. W. J. M. (2020). Adolescents’ intense and problematic social media use and their well-being in 29 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), S89–S99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.014

Buunk, A. P., & Gibbons, F. X. (2006). Social comparison orientation: A new perspective on those who do and those who don't compare with others. In S. Guimond (Ed.), Social comparison and social psychology: Understanding cognition, intergroup relations, and culture (pp. 15–32). Cambridge University Press.

Chao, M., Lei, J., He, R., Jiang, Y., & Yang, H. (2023). TikTok use and psychosocial factors among adolescents: Comparisons of non-users, moderate users, and addictive users. Psychiatry Research, 325, Article 115247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115247

Chen, W., Fan, C., Liu, Q., Zhou, Z., & Xie, X. (2016). Passive social network site use and subjective well-being: A moderated mediation model. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 507–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.038

Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A. A., Zurcher, J. D., Stockdale, L., & Booth, M. (2020). Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: An eight year longitudinal study. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, Article 106160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106160

Cramer, E. M., Song, H., & Drent, A. M. (2016). Social comparison on Facebook: Motivation, affective consequences, self-esteem, and Facebook fatigue. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 739–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.049

Derbaix, M., Masciantonio, A., Balbo, L., Lao, A., Camus, S., Tafraouti, S. I., & Bourguignon, D. (2025). Understanding social comparison dynamics on social media: A qualitative examination of individual and platform characteristics. Psychology & Marketing, 42(6), 1588–1606. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.22194

Faelens, L., Hoorelbeke, K., Fried, E., De Raedt, R., & Koster, E. H. W. (2019). Negative influences of Facebook use through the lens of network analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 96, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.02.002

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2016). Exploring the relationships between different types of Facebook use, perceived online social support, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Social Science Computer Review, 34(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314567449

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2017). Browsing, posting, and liking on Instagram: The reciprocal relationships between different types of Instagram use and adolescents’ depressed mood. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 20(10), 603–609. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0156

Gabriel, A. S., Podsakoff, N. P., Beal, D. J., Scott, B. A., Sonnentag, S., Trougakos, J. P., & Butts, M. M. (2019). Experience sampling methods: A discussion of critical trends and considerations for scholarly advancement. Organizational Research Methods, 22(4), 969–1006. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118802626

Gerson, J., Plagnol, A. C., & Corr, P. J. (2016). Subjective well-being and social media use: Do personality traits moderate the impact of social comparison on Facebook? Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 813–822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.023

Gibbons, F. X., & Buunk, B. P. (1999). Individual differences in social comparison: Development of a scale of social comparison orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(1), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.129

Gingras, M., Brendgen, M., Beauchamp, M. H., Séguin, J. R., Tremblay, R. E., Côté, S. M., & Herba, C. M. (2023). Adolescents and social media: Longitudinal links between types of use, problematic use and internalizing symptoms. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 51(11), 1641–1655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-023-01084-7

Gurtala, J. C., & Fardouly, J. (2023). Does medium matter? Investigating the impact of viewing ideal image or short-form video content on young women’s body image, mood, and self-objectification. Body Image, 46, 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.06.005

Hamaker, E. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2021). Dynamic structural equation modeling as a combination of time series modeling, multilevel modeling, and structural equation modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), The handbook of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Hamaker, E. L., Asparouhov, T., Brose, A., Schmiedek, F., & Muthén, B. (2018). At the frontiers of modeling intensive longitudinal data: Dynamic structural equation models for the affective measurements from the COGITO study. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 53(6), 820–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2018.1446819

Harriger, J. A., Thompson, J. K., & Tiggemann, M. (2023). TikTok, TikTok, the time is now: Future directions in social media and body image. Body Image, 44, 222–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.01.005

Heggestad, E. D., Kreamer, L., Hausfeld, M. M., Patel, C., & Rogelberg, S. G. (2022). Recommendations for reporting sample and measurement information in experience sampling studies. British Journal of Management, 33(2), 553–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12489

Indian, M., & Grieve, R. (2014). When Facebook is easier than face-to-face: Social support derived from Facebook in socially anxious individuals. Personality and Individual Differences, 59, 102–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.11.016

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

Kleemans, M., Daalmans, S., Carbaat, I., & Anschütz, D. (2018). Picture perfect: The direct effect of manipulated Instagram photos on body image in adolescent girls. Media Psychology, 21(1), 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2016.1257392

Kraut, R., Patterson, M., Lundmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukopadhyay, T., & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox. A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist, 53(9), 1017–1031. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.53.9.1017

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Monahan, P. O., & Löwe, B. (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(5), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004

Lee, S. Y. (2014). How do people compare themselves with others on social network sites?: The case of Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 32, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.009

Levenson, J. C., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., & Primack, B. A. (2016). The association between social media use and sleep disturbance among young adults. Preventive Medicine, 85, 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.01.001

Li, S., Zhao, T., Feng, N., Chen, R., & Cui, L. (2025). Why we cannot stop watching: Tension and subjective anxious affect as central emotional predictors of short-form video addiction. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-025-01486-2

Lian, S., Sun, X., Niu, G., & Zhou, Z. (2017). Upward social comparison on SNS and depression: A moderated mediation model and gender difference. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 49(7), 941–952. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2017.00941

Liu, M., Zhuang, A., Norvilitis, J. M., & Xiao, T. (2024). Usage patterns of short videos and social media among adolescents and psychological health: A latent profile analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 151, Article 108007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.108007

Lockwood, P., & Kunda, Z. (1997). Superstars and me: Predicting the impact of role models on the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.91

Malloch, Y. Z., Zhang, J., & Qian, S. (2023). Effects of social comparison direction, comparison distance, and message framing on health behavioral intention in online support groups. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 17(3), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2023-3-10

Marengo, D., Montag, C., Sindermann, C., Elhai, J. D., & Settanni, M. (2021). Examining the links between active Facebook use, received likes, self-esteem and happiness: A study using objective social media data. Telematics and Informatics, 58, Article 101523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101523

Masciantonio, A., Bourguignon, D., Bouchat, P., Balty, M., & Rimé, B. (2021). Don’t put all social network sites in one basket: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, and their relations with well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 16(3), Article e0248384. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248384

Masur, P. K., Reinecke, L., Ziegele, M., & Quiring, O. (2014). The interplay of intrinsic need satisfaction and Facebook specific motives in explaining addictive behavior on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 376–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.047

McNeish, D. (2019). Two-level dynamic structural equation models with small samples. Structural Equation Modeling, 26(6), 948–966. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2019.1578657

McNeish, D., & Hamaker, E. L. (2020). A primer on two-level dynamic structural equation models for intensive longitudinal data in Mplus. Psychological Methods, 25(5), 610–635. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000250

Meshi, D., & Ellithorpe, M. E. (2021). Problematic social media use and social support received in real-life versus on social media: Associations with depression, anxiety and social isolation. Addictive Behaviors, 119, Article 106949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106949

Midgley, C., Thai, S., Lockwood, P., Kovacheff, C., & Page-Gould, E. (2021). When every day is a high school reunion: Social media comparisons and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(2), 285–307. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000336

Montag, C., Müller, M., Pontes, H. M., & Elhai, J. D. (2023). On fear of missing out, social networks use disorder tendencies and meaning in life. BMC Psychology, 11(1), Article 358. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01342-9

Muthén, B. (2010). Bayesian analysis in Mplus: A brief introduction. https://www.statmodel.com/download/IntroBayesVersion%203.pdf

Pan, W., Mu, Z., Zhao, Z., & Tang, Z. (2023). Female users' TikTok use and body image: Active versus passive use and social comparison processes. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 26(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2022.0169

Pang, H. (2021). Unraveling the influence of passive and active WeChat interactions on upward social comparison and negative psychological consequences among university students. Telematics and Informatics, 57, Article 101510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101510

Pew Research Center. (2018, May 31). Teens, social media, and technology 2018. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

Pontes, H. M., Taylor, M., & Stavropoulos, V. (2018). Beyond “Facebook addiction”: The role of cognitive-related factors and psychiatric distress in social networking site addiction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 21(4), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0609

Pouwels, J. L., Valkenburg, P. M., Beyens, I., van Driel, I. I., & Keijsers, L. (2021). Some socially poor but also some socially rich adolescents feel closer to their friends after using social media. Scientific Reports, 11(1), Article 21176. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-99034-0

Pryde, S., & Prichard, I. (2022). TikTok on the clock but the #fitspo don't stop: The impact of TikTok fitspiration videos on women's body image concerns. Body Image, 43, 244–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.09.004

Qu, D., Liu, B., Jia, L., Zhang, X., Chen, D., Zhang, Q., Feng, Y., & Chen, R. (2024). The longitudinal relationships between short video addiction and depressive symptoms: A cross-lagged panel network analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 152, Article 108059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.108059

Schäfer, J. Ö., Naumann, E., Holmes, E. A., Tuschen-Caffier, B., & Samson, A. C. (2017). Emotion regulation strategies in depressive and anxiety symptoms in youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(2), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0585-0

Scherr, S., & Wang, K. (2021). Explaining the success of social media with gratification niches: Motivations behind daytime, nighttime, and active use of TikTok in China. Computers in Human Behavior, 124, Article 106893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106893

Schmuck, D., Karsay, K., Matthes, J., & Stevic, A. (2019). “Looking up and feeling down”. The influence of mobile social networking site use on upward social comparison, self-esteem, and well-being of adult smartphone users. Telematics and Informatics, 42, Article 101240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2019.101240

Scott, C. F., Bay-Cheng, L. Y., Prince, M. A., Nochajski, T. H., & Collins, R. L. (2017). Time spent online: Latent profile analyses of emerging adults' social media use. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.026

Seabrook, E. M., Kern, M. L., & Rickard, N. S. (2016). Social networking sites, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review. JMIR Mental Health, 3(4), Article e50. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5842

Shaw, A. M., Timpano, K. R., Tran, T. B., & Joormann, J. (2015). Correlates of Facebook usage patterns: The relationship between passive Facebook use, social anxiety symptoms, and brooding. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 575–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.003

Solomon, R. L. (1980). The opponent-process theory of acquired motivation: The costs of pleasure and the benefits of pain. American Psychologist, 35(8), 691–712. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.35.8.691

Spielberger, C. D. (1985). Assessment of state and trait anxiety: Conceptual and methodological issues. Southern Psychologist, 2(4), 6–16. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1991-55057-001

Steinsbekk, S., Nesi, J., & Wichstrøm, L. (2023). Social media behaviors and symptoms of anxiety and depression. A four-wave cohort study from age 10–16 years. Computers in Human Behavior, 147, Article 107859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107859

Su, C., Zhou, H., Gong, L., Teng, B., Geng, F., & Hu, Y. (2021). Viewing personalized video clips recommended by TikTok activates default mode network and ventral tegmental area. NeuroImage, 237, Article 118136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118136

Sun, R., Zhang, M. X., Yeh, C., Ung, C. O. L., & Wu, A. M. S. (2024). The metacognitive-motivational links between stress and short-form video addiction. Technology in Society, 77, Article 102548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102548

Sun, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2021). A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addictive Behaviors, 114, Article 106699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106699

Thorisdottir, I. E., Sigurvinsdottir, R., Asgeirsdottir, B. B., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2019). Active and passive social media use and symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood among Icelandic adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 22(8), 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0079

Tian, X., Bi, X., & Chen, H. (2023). How short-form video features influence addiction behavior? Empirical research from the opponent process theory perspective. Information Technology & People, 36(1), 387–408. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-04-2020-0186

Tibbs, M., Deschênes, S., van der Velden, P., & Fitzgerald, A. (2025). An investigation of the longitudinal bidirectional associations between interactive versus passive social media behaviors and youth internalizing difficulties. A within-person approach. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 54(4), 849–862. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-024-02093-5

Trapletti, A., & Hornik, K. (2024). tseries: Time series analysis and computational finance (R package version 0.10-57).

Vagg, P. R., Spielberger, C. D., & O’Hearn, T. P. (1980). Is the state–trait anxiety inventory multidimensional? Personality and Individual Differences, 1(3), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(80)90052-5

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2013). The differential susceptibility to media effects model: Differential susceptibility to media effects model. Journal of Communication, 63(2), 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12024

Vannucci, A., Flannery, K. M., & Ohannessian, C. M. (2017). Social media use and anxiety in emerging adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 207, 163–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.040

Verduyn, P., Gugushvili, N., Massar, K., Täht, K., & Kross, E. (2020). Social comparison on social networking sites. Current Opinion in Psychology, 36, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.04.002

Verduyn, P., Lee, D. S., Park, J., Shablack, H., Orvell, A., Bayer, J., Ybarra, O., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2015). Passive Facebook usage undermines affective well-being: Experimental and longitudinal evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(2), 480–488. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000057

Verduyn, P., Schulte-Strathaus, J. C. C., Kross, E., & Hülsheger, U. R. (2021). When do smartphones displace face-to-face interactions and what to do about it? Computers in Human Behavior, 114, Article 106550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106550

Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Okdie, B. M., Eckles, K., & Franz, B. (2015). Who compares and despairs? The effect of social comparison orientation on social media use and its outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.026

Wang, Z., Yang, H., & Elhai, J. D. (2022). Are there gender differences in comorbidity symptoms networks of problematic social media use, anxiety and depression symptoms? Evidence from network analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 195, Article 111705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111705

Wirtz, D., Tucker, A., Briggs, C., & Schoemann, A. M. (2021). How and why social media affect subjective well-being: Multi-site use and social comparison as predictors of change across time. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(4), 1673–1691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00291-z

Wu, Y., Wang, X., Hong, S., Hong, M., Pei, M., & Su, Y. (2021). The relationship between social short-form videos and youth’s well-being: It depends on usage types and content categories. Psychology of Popular Media, 10(4), 467–477. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000292

Xia, L., Li, J., Duan, F., Zhang, J., Mu, L., Wang, L., Jiao, C., Song, X., Wang, Z., Chen, J., Wang, J., Wang, Y., Zhang, X., & Jiao, D. (2023). Effects of online game and short video behavior on academic delay of gratification - mediating effects of anxiety, depression and retrospective memory. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 4353–4365. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s432196

Xiang, K., & Kong, F. (2024). Passive social networking sites use and disordered eating behaviors in adolescents: The roles of upward social comparison and body dissatisfaction and its sex differences. Appetite, 198, Article 107360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2024.107360

Zhang, W., Zhang, J., He, T., Hu, H., Hinshaw, S., & Lin, X. (2024). Dynamic patterns of COVID stress syndrome among university students during an outbreak: A time-series network analysis. Psychology & Health, 39(13), 2039–2057. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2024.2395854

Zhu, C., Jiang, Y., Lei, H., Wang, H., & Zhang, C. (2024). The relationship between short-form video use and depression among Chinese adolescents: Examining the mediating roles of need gratification and short-form video addiction. Heliyon, 10(9), Article e30346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30346

Zhu, W., Mou, J., Benyoucef, M., Kim, J., Hong, T., & Chen, S. (2023). Understanding the relationship between social media use and depression: A review of the literature. Online Information Review, 47(6), 1009–1035. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-04-2021-0211

Authors' Contribution

Zhiwei Yang: data curation, formal analysis, software, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. Qian Nie: conceptualization, writing—review & editing. Xiaoqin Wang: software, writing—review & editing. Halley M. Pontes: writing—review & editing. Zhaojun Teng: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, software, supervision, writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

February 5, 2025

Revisions received:

July 22, 2025

November 16, 2025

Accepted for publication:

December 19, 2025

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

Anxiety symptoms are among the most common emotional problems in daily life and if left unaddressed can escalate into severe anxiety disorders, significantly impacting individual well-being and mental health (Schäfer et al., 2017). In the digital age, as daily life becomes increasingly intertwined with online interactions, there is growing concern that social media use, particularly usage related to short video consumption, may negatively affect mental health (Qu et al., 2024; C. Zhu et al., 2024). Recent studies have suggested that excessive use of short video platforms is associated with increased anxiety symptoms (e.g., Chao et al., 2023; Xia et al., 2023). However, much of the existing research relies on cross-sectional designs and focuses primarily on the association between problematic social media use and anxiety symptoms (e.g., Pontes et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2022). Although, some studies have examined different patterns of social media use (e.g., active versus passive use) and their specific relationships with anxiety symptoms (e.g., Seabrook et al., 2016; Shaw et al., 2015; Thorisdottir et al., 2019), the dynamic relationship between daily short video use and anxiety symptoms remains unclear. Specifically, it is not well understood how active short video use (e.g., direct communication and posting) and passive short video use (e.g., scrolling and avoiding comments) interact with anxiety symptoms over time.

Importantly, according to the differential susceptibility to media effects model (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013), media effects may depend on individual differences, such as upward social comparisons (Kleemans et al., 2018; Vogel et al., 2015). Yet, the role of upward social comparison in the dynamic relationship between short video use and anxiety symptoms has also not been thoroughly investigated. To address these gaps, the current study employed an Experience Sampling Method (ESM) and Dynamic Structural Equation Modeling (DSEM) to examine the dynamic relationships between active and passive short video use and anxiety symptoms and to evaluate the moderating effect of upward social comparisons, thereby offering insights into individual differences in short video use effects.

Short Video Use and Anxiety Symptoms

Numerous studies have shown that frequent social media use is associated with increased anxiety symptoms (e.g., Faelens et al., 2019; Vannucci et al., 2017) and anxiety-related experiences such as fear of missing out (e.g., Montag et al., 2023). Similar to general social media use (Boer et al., 2022), short video usage including the frequency and duration of posting or watching short videos on platforms such as TikTok, Facebook, and Twitter, has become increasingly prevalent. These videos offer highly engaging and personalized content that can be consumed in rapid succession, potentially leading to excessive use (R. Sun et al., 2024) and mental health concerns (Qu et al., 2024). For instance, a cross-sectional study found a significant positive association between short video use and anxiety symptoms (Xia et al., 2023). However, the longitudinal relationship between short video use and anxiety symptoms, particularly in daily contexts, remains underexplored.

Both empirical findings and theoretical frameworks suggest a possible bidirectional relationship between daily short video use and anxiety symptoms. On the one hand, short video use may exacerbate anxiety symptoms. According to the social displacement hypothesis (Kraut et al., 1998), social media consumption reduces the time individuals may spend on other beneficial activities (Verduyn et al., 2021). Excessive use can undermine face-to-face interactions (Verduyn et al., 2021) and disrupt sleep patterns (Levenson et al., 2016), potentially leading to emotional problems including anxiety symptoms (Alonzo et al., 2021; Meshi & Ellithorpe, 2021). Due to their rich visual and auditory appeal, short videos are particularly engaging and may increase the risk of problematic use and addiction (Su et al., 2021), further displacing activities that can promote psychological well-being (Qu et al., 2024).

On the other hand, individuals experiencing heightened anxiety symptoms may elevate their short video use as a coping strategy. According to the compensatory internet use theory (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014), social media can function as a means for escaping stress and regulating negative emotions (Masur et al., 2014; Y. Sun & Y. Zhang, 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Previous research has identified escapism as a primary motivation for short video consumption, particularly as a response to real-life stressors (Scherr & Wang, 2021), suggesting that individuals may consume short videos in order to alleviate anxiety symptoms (Li et al., 2025).

However, several longitudinal studies have questioned the assumption of a significant bidirectional relationship between social media use and anxiety symptoms (e.g., Beeres et al., 2021; Coyne et al., 2020). Some scholars have emphasized the importance of distinguishing between active and passive social media use as these patterns may have different implications for mental health (e.g., Masciantonio et al., 2021; Thorisdottir et al., 2019; Verduyn et al., 2015). For example, Thorisdottir et al. (2019), in a large-scale study of 10,563 adolescents, found that passive social media use was associated with increased anxiety symptoms, while active use was linked to reduced anxiety symptoms.

Active users who engage in behaviors such as posting and commenting, may benefit from greater social support and positive feedback, which can help reduce anxiety symptoms (Frison & Eggermont, 2016; Marengo et al., 2021). The diverse content of short videos may fulfill social needs (C. Zhu et al., 2024) while offering a new emotion regulation strategy (Qu et al., 2024), potentially enhancing well-being (Indian & Grieve, 2014; Seabrook et al., 2016). In contrast, passive users who consume content without actively engaging, may experience heightened anxiety symptoms (Wu et al., 2021). Short video platforms are particularly saturated with idealized and heavily curated content (Faelens et al., 2019; Gerson et al., 2016; Scherr & Wang, 2021) and regular exposure to such content may fuel upward social comparisons (Pang, 2021; Schmuck et al., 2019), leading to lower self-esteem and poorer mental health outcomes (Chen et al., 2016; Frison & Eggermont, 2017; Wirtz et al., 2021), including the experience of increased anxiety symptoms (Faelens et al., 2019).

Nevertheless, other longitudinal studies have found no significant relationship between short video use and anxiety symptoms (e.g., Boer et al., 2022; Gingras et al., 2023; Steinsbekk et al., 2023; Tibbs et al., 2025). For example, Gingras et al. (2023), using a cross-lagged panel model with 257 adolescents, found no bidirectional relationship between passive social media use and anxiety symptoms. Therefore, these mixed findings within the existing literature reinforce the need to further investigate the dynamic relationship between short video use patterns and anxiety symptoms.

Moderating Effect of Upward Social Comparisons

Although short video use may be a significant risk factor for mental health problems, not all individuals experience more negative emotions (Chao et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2024). According to the differential susceptibility to media effects model (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013), the bidirectional effect between social media use and mental health may depend on individual differences, such as upward social comparison (Kleemans et al., 2018; Vogel et al., 2015). Upward social comparison in social media refers to individuals browsing others’ positive social media content and comparing themselves to those perceived as superior (Lian et al., 2017; Xiang & Kong, 2024). This may lead to two outcomes, namely benign envy or malicious envy (Derbaix et al., 2025; Malloch et al., 2023). Benign envy may be beneficial to self-improvement and enhancement of individual mental health (Derbaix et al., 2025; Malloch et al., 2023). In contrast, malicious envy which is characterized by resentment and frustration, can undermine self-esteem and negatively affect mental health (Wirtz et al., 2021). This effect may be particularly pronounced in the context of short video use, which often features idealized portrayals of others’ lives (Gurtala & Fardouly, 2023; Harriger et al., 2023; Pryde & Prichard, 2022).

A previous study reported that individuals with high upward social comparisons experienced a greater decline in self-esteem and more severe psychological consequences when using social media compared to those with low upward social comparisons (Verduyn et al., 2020). Moreover, upward social comparison often occurs during passive social media use rather than active social media use (Faelens et al., 2019; Pang, 2021; Verduyn et al., 2020). For example, Pang (2021) found that upward social comparisons significantly moderated the relationship between passive social media use and negative emotions, whereas no such effect was observed for active use in a sample of 318 college students. Individuals with a strong tendency toward upward social comparison may exacerbate the negative effects of short video use time on anxiety symptoms. In contrast, those with low levels of upward social comparison who are less likely to engage in such comparisons, may be less vulnerable to negative emotional outcomes, such as reduced self-esteem (Vogel et al., 2015). It still remains unclear whether upward social comparison moderates the relationship between different patterns of short video use and anxiety symptoms, an issue the current study aims to address.

The Current Study

Previous studies have often relied on cross-sectional designs and traditional analytical methods that conflate within-person and between-person effects, obscuring the true nature of the relationships between variables. To address these limitations, the present study employs an ESM and DSEM approach to examine the dynamic relationship between short video use and anxiety symptoms.

As such, this study proposed the following set of hypotheses. At the within-person (state) level, a bidirectional predictive association between short video use and daily anxiety symptoms is expected (H1). Specifically, short video use is expected to predict subsequent anxiety symptoms (H1a) and daily anxiety symptoms expected to predict subsequent short video use (H1b). We did not specify the directionality of these within-person effects as previous research has yielded inconsistent conclusions regarding the media effects of short video use and because the current evidence within the literature is not causal. At the between-person (trait) level, it is proposed that upward social comparison will moderate the bidirectional association between short video use time and daily anxiety symptoms (H2). Specifically, individuals with a higher tendency toward upward social comparison are expected to experience greater anxiety with increased short video use time (H2a), whereas individuals with lower upward social comparison are expected to experience reduced anxiety with increased short video use time (H2b). Given the lack of strong theoretical evidence, we did not advance specific hypotheses regarding the moderating role of upward social comparison in the association between types of short video use (active vs. passive) and anxiety symptoms, however, exploratory analyses were conducted.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Southwest University (IRB: H24024) and all the participants provided informed consent and agreed to participate in the survey. Data were collected via an online platform (https://www.wjx.cn). A priori power analysis based on Monte Carlo simulation recommended that a sample size of 300 participants with 42 assessments would be sufficient to reliably detect small within-person effect sizes in multi-level analyses (Pouwels et al., 2021). Taking potential attrition and compliance into account, we aimed for a sample size of 450 participants. By using a snowball sampling method, we encouraged participants to send recruitment information to their college classmates. In total, 455 Chinese university students participated in experience sampling, and an intensive 1-month follow-up was conducted from November to December 2023, with a post-investigation carried out at the end of the experience sampling. The experience-sampling phase required participants to report their short video use and anxiety symptoms twice a day, from 12:00 to 16:40 and 21:30 to 24:00, for 30 days. To minimize missing values, participants who did not complete the task within 2 hours received a separate reminder.

In the present study, 41 participants were excluded either because their reaction times in the pre-test stage were short or because they had failed to pass an attention-detection question (i.e., answering very untruthfully or untruthfully to the following question: In this survey, I truthfully answered all the questions). During the experience-sampling period, 25 participants withdrew from the study. Therefore, a total of 389 participants were asked to complete 60 rounds of questionnaires, with each participant completing an average of 58.52 rounds. Finally, 389 participants completed a dataset containing 22,764 pieces of data, with a total missing ratio of 2.47%. Simulation studies have shown that DSEM is still robust even at 80% missing values (Asparouhov et al., 2018). All 389 participants were included in the final analyses and detailed participant information can be seen in Tables S1 and S2. Participants were aged 17 to 25 years (Mage = 20.38, SD = 1.44). The sample comprised 199 males (51.1%) and 190 females (48.8%), including 81 freshmen (20.8%), 128 sophomores (32.9%), 122 juniors (31.3%), and 58 seniors (14.9%).

Measures

Anxiety Symptoms

Anxiety symptoms in the ESM were measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Questionnaire developed by Spielberger (1985). Three items were used to measure state anxiety symptoms (i.e., How relaxed do I feel?, How upset do I feel?, and How anxious do I feel?) as they represent the core symptoms of anxiety (Kroenke et al., 2007; Spielberger, 1985). The responses ranged from 1 (very little) to 7 (very much). Because How relaxed do I feel? loads negatively on the state anxiety construct (Vagg et al., 1980), this item was reverse-scored to minimize response bias. Higher average scores across the three items indicate greater anxiety symptoms. Within the present study, the internal consistency of this measure was adequate, with Omega coefficients of .792 and .938 at the within-person and between-person levels, respectively.

Short Video Use

The short video use scale used in the ESM included three questions designed for this study according to the research purpose. Active and passive short video use were measured by Since the last measurement, how frequently did I post/browse short videos on platforms such as WeChat Friend's Circle, QQ, Xiaohongshu, or TikTok?. The frequency of users' active and passive short video use was recorded using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = none, 2 = 1–2 times, 3 = 3–4 times, 4 = 5–6 times, 5 = 7 times or more). The duration of short video usage was measured by the following question: Since the last measurement, how much time have I spent browsing short videos on platforms such as WeChat Friend's Circle, QQ, Xiaohongshu, or TikTok?. Participants' short video use time was also recorded using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = 0–5 minutes, 2 = 5–15 minutes, 3 = 16–30 minutes, 4 = 31 minutes–2 hours, 5 = more than 2 hours). Higher scores indicate greater levels of short video use. Given the nested structure of the ESM data, reliability must be evaluated at multiple levels (Gabriel et al., 2019; Heggestad et al., 2022). Following previous research (W. Zhang et al., 2024), Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) were calculated to estimate the reliability of single measurement items (see Table 1).

Upward Social Comparisons

To assess the participants’ upward social comparison tendencies, the Iowa-Netherlands Comparison Orientation Measure Scale (Gibbons & Buunk, 1999) as revised by Lian et al. (2017) was used in this study’s pre-test phase. The original questionnaire’s scope of comparison was adjusted to focus on “short video usage” to ensure relevance. Specifically, the phrase On social networking sites was changed to In short video apps, I often like to compare myself to those who are better than me. This scale consists of 6 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 (very inconsistent) to 5 (very consistent). This measure has been demonstrated to be suitable and reliable for use with Chinese samples (Lian et al., 2017). In this study, the Omega coefficient for upward social comparison tendency was .927, indicating adequate internal consistency.

Data Analysis

Although participants were required to submit complete responses, intensive tracking demands responses at specific times, making some missing data typically unavoidable. DSEM is based on the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm, which samples missing data from the conditional posterior to ensure consistent estimates (Hamaker et al., 2018). Missing data were handled using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation in Mplus 8.3. The smoothness of the time series is key to conducting DSEM analyses (McNeish & Hamaker, 2020). Using the tseries package (Trapletti & Hornik, 2024) in R 4.4.1, we conducted the Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin (KPSS) tests with Bonferroni corrections on the primary variables of interest for each participant to assess stationarity. Moreover, due to the sample size and the long time series, the assumption of a normal distribution may not pose an issue for the current study (Hamaker et al., 2021), as large samples and extensive data help mitigate concerns regarding deviations from normality.

Furthermore, DSEM integrates time-series analysis (Hamaker et al., 2018), time-varying effects, and multilevel modeling techniques (McNeish, 2019), enabling the decomposition of within-person and between-person effects (McNeish & Hamaker, 2020). Within the context of the present research, within-person effect reflects how fluctuations in an individual’s short video use at a given time predict changes in their anxiety symptoms at the next time point. In contrast, the between-person effect captures how individuals who generally use short videos more or less frequently differ from others in their average levels of anxiety symptoms. It is important to distinguish within- and between-person effects as these can diverge or even operate in opposite directions (Beyens et al., 2020; Boer et al., 2022).

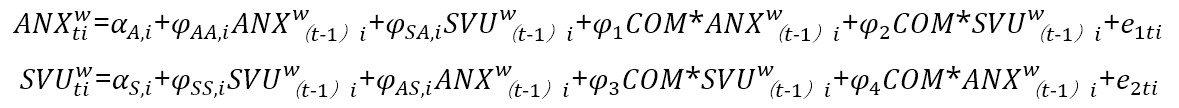

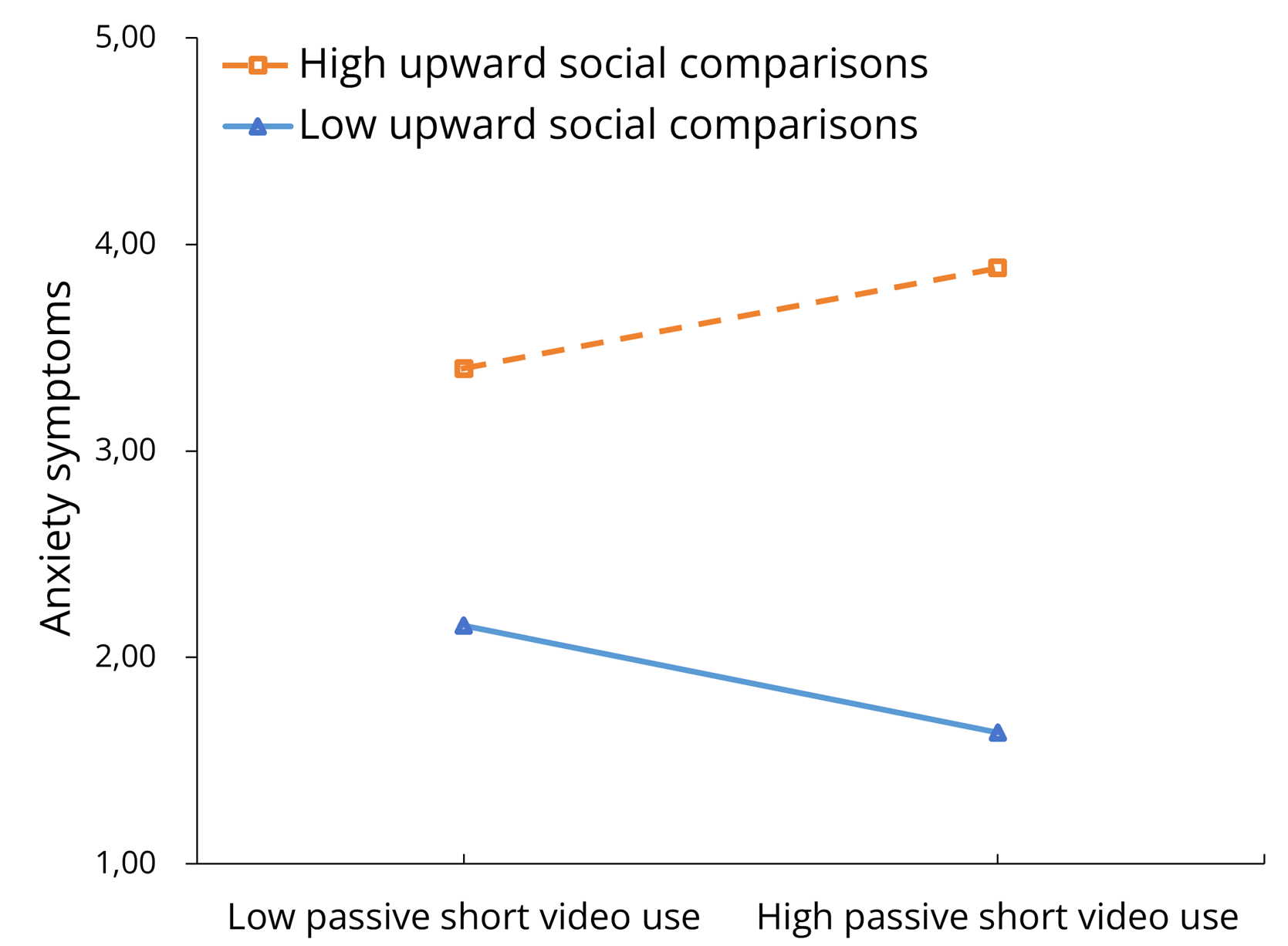

A null model was first estimated to obtain the means, correlations, and ICCs of the main variables. At the within-person level, autoregressive (i.e., ANX t → ANX t+1; SVU t → SVU t+1) and cross-lagged paths (i.e., ANX t → SVU t+1; SVU t → ANX t+1) were specified to assess the stability of the repeated measures, their dynamic predictive relationships, and the residual variance in short video use and anxiety symptoms. At the between-person level, upward social comparison was modeled as a moderator of the random autoregressive and cross-lagged effects to account for individual differences. The equations and specific model are presented below and in Figure 1. To present the model hypothesis more clearly, the time and demographic covariates are not shown, as presented in the Supplementary material S2.

DSEM uses Bayesian estimation with the default MCMC algorithm (Asparouhov et al., 2018; Hamaker et al., 2018). All models used 2 MCMC chains with an iteration = 5000 and thin = 10 designated as non-informative priors to improve estimation accuracy and efficiency. Three criteria were used to evaluate model convergence: (1) potential scale reduction (PSR) value; (2) autocorrelation; and (3) posterior trace plots (Hamaker et al., 2018). The significance level was set to .05 and a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) was applied. Regression coefficients were deemed statistically significant if the 95% CI did not include zero.

Figure 1. DSEM of Short Video Use and Anxiety Symptoms.

Note. ANX = anxiety symptoms; SVU = short video use; COM = upward social comparison. φAA,i and φSS,i refer to the autoregressive effects of anxiety symptoms and short video use, respectively. φSA,i and φAS,i represent the influence of anxiety symptoms in the previous time on the current short video use, and the influence of short video use in the previous time point on the current anxiety symptoms, respectively. e1ti and e2ti represent residuals for anxiety symptoms and short video use, respectively. logAA,i and logSS,I represent the within-level residual variance of anxiety symptoms and short video use, respectively. w represents the intra individual estimate, μ represents the mean, and the bold black dots represent random parameters.

In addition, the study introduced a dummy coded variable distinguishing between midday (coded as 0) and evening (coded as 1) to control for potential confounding effects due to time variations. It was introduced independently of the formal assumptions and only to adjust for the inherent differences between the time periods.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Table 1 presents the means, variances, ICCs, and within- and between-person correlations between anxiety symptoms, frequency of active and passive short video use, and duration of short video use. The ICCs indicated that approximately half of the variance in each variable was attributable to within-person fluctuations, with the remaining half reflecting between-person differences. At the within-person level, weak correlations were observed between anxiety symptoms and the three indicators of short video use (i.e., active short video use, passive short video use, and usage time). In contrast, at the between-person level, negative correlations emerged between anxiety symptoms and short video use, except for passive short video use which showed no significant association.

Model Fit Indices

First, the potential scale reduction results of the 3 models were all less than 1.05, indicating that the model converged well. Second, the autocorrelation graph showed that most parameters did not have a high autocorrelation. For parameters with a high autocorrelation, the application of thin = 10 can improve the accuracy of prediction (Muthén, 2010). Third, the two chains overlapped well and all parameters showed similar autocorrelation and post-trace graphs. Therefore, only a graph with a few parameters is shown in Supplementary material S3 as an example.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistical Results and Intra-Group Correlation Coefficients (ICC).

|

Variable |

Mean |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

Variance |

ICC |

ANX |

ASVU |

PSVU |

SVUT |

|

|

Within |

Between |

|||||||||

|

ANX |

3.069 |

0.532 |

−0.52 |

0.902 |

1.141 |

0.558 |

— |

−0.101* |

−0.062 |

−0.183*** |

|

ASVU |

1.396 |

2.384 |

5.912 |

0.266 |

0.352 |

0.570 |

−0.019*** |

— |

0.223*** |

0.118*** |

|

PSVU |

2.863 |

0.421 |

−0.749 |

0.578 |

0.827 |

0.589 |

−0.043*** |

0.115*** |

— |

0.775*** |

|

SVUT |

3.334 |

−0.463 |

−0.613 |

0.678 |

0.734 |

0.528 |

−0.049*** |

0.092*** |

0.594*** |

— |

|

Note. ANX = anxiety symptoms; ASVU = active short video use; PSVU = passive short video use; SVUT = short video usage time. The lower-left and upper-right corners present the within-person- and between-person-level standardized correlation coefficients. *p < .05, ***p < .001. |

||||||||||

DSEM of Short Video Use and Anxiety Symptoms

As shown in Table 2, Model 1, 2, and 3 present the DSEM results of active short video use (ASVU) and anxiety symptoms, passive short video use (PSVU) and anxiety symptoms, short video use time (SVUT) and anxiety symptoms, respectively. The results revealed significant autoregressive effects for active short video use; ASVU t → ASVU t+1 = .193, 95%CI = [.177, .209], passive short video use; PSVU t → PSVU t+1 = .242, 95%CI = [.228, .255], usage time; SVUT t → SVUT t+1= .212, 95%CI = [.199, .226], and anxiety symptoms (ANX t→ANX t+1 in Model 1, Model 2, Model 3 were 0.176, 0.173, 0.173, respectively; all 95% CIs did not include zero).

However, no significant cross-lagged effects were found between short video use (i.e., ASVU, PSVU, and SVUT) and anxiety symptoms. Specifically, short video use at time t did not significantly predict anxiety symptoms at time t+1; ASVU t→ANX t+1 = −.007, 95%CI = [−.019, .006]; PSVU t→ANX t+1 = −.006, 95%CI = [−.019, .007]; SVUT t→ANX t+1 = .003, 95%CI = [−.010, .017]. Anxiety symptoms at time t also did not significantly predict short video use at time t+1; ANX t → ASVU t+1 = −.009, 95%CI = [−.021, .003]; ANX t → PSVU t+1 = −.007, 95%CI = [−.020, .006]; ANX t → SVUT t+1 = −.007, 95%CI = [−.020, .006].

Table 2. DSEM Standardized Estimates.

|

|

Model 1 DSEM of ASVU |

Model 2 DSEM of PSVU |

Model 3 DSEM of SVUT |

||||||

|

|

Estimate |

SE |

95% CI[lower, upper] |

Estimate |

SE |

95% CI[lower, upper] |

Estimate |

SE |

95% CI[lower, upper] |

|

Within-person level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ANX→ANX |

0.176 |

0.007 |

[0.163, 0.190] |

0.173 |

0.007 |

[0.159, 0.186] |

0.173 |

0.007 |

[0.159, 0.186] |

|

SVU→SVU |

0.193 |

0.008 |

[0.177, 0.209] |

0.242 |

0.007 |

[0.228, 0.255] |

0.212 |

0.007 |

[0.199, 0.226] |

|

SVU→ANX |

−0.007 |

0.006 |

[−0.019, 0.006] |

−0.006 |

0.007 |

[−0.019, 0.007] |

0.003 |

0.007 |

[−0.010, 0.017] |

|

ANX→SVU |

−0.009 |

0.006 |

[−0.021, 0.003] |

−0.007 |

0.007 |

[−0.020, 0.006] |

−0.007 |

0.007 |

[−0.020, 0.006] |

|

LogANX |

0.893 |

0.004 |

[0.884, 0.901] |

0.891 |

0.004 |

[0.882, 0.900] |

0.890 |

0.004 |

[0.881, 0.899] |

|

LogSVU |

0.893 |

0.004 |

[0.885, 0.900] |

0.858 |

0.005 |

[0.848, 0.867] |

0.868 |

0.005 |

[0.859, 0.877] |

|

Between-person level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Effect of COM on |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ANX→ANX |

−0.094 |

0.045 |

[−0.183, −0.005] |

−0.105 |

0.045 |

[−0.192, −0.015] |

−0.122 |

0.044 |

[−0.210, −0.035] |

|

SVU→SVU |

0.027 |

0.042 |

[−0.053, 0.108] |

−0.063 |

0.043 |

[−0.143, 0.021] |

−0.093 |

0.043 |

[−0.176, −0.009] |

|

SVU→ANX |

−0.174 |

0.113 |

[−0.394, 0.049] |

−0.162 |

0.077 |

[−0.310, −0.013] |

−0.069 |

0.072 |

[−0.210, 0.066] |

|

ANX→SVU |

0.031 |

0.065 |

[−0.090, 0.160] |

−0.134 |

0.084 |

[−0.295, 0.034] |

−0.050 |

0.075 |

[−0.196, 0.095] |

|

Note. Bold values indicate significance based on 95%CIs that do not include zero. SVU = short video use (active short video use in Model 1, passive short video use in Model 2, and usage time in Model 3); ANX = anxiety symptoms; COM = upward social comparison. logAA,i and logSS,I represent the within-level residual variance of anxiety symptoms and short video use, respectively. For a clearer representation of the variables studied, the results of between-person level correlations are presented in Supplementary material S4. Supplementary material S5 reports the DSEM results including covariates. In addition, FDR correction was performed to control false positive results that may result from separate modeling (see Supplementary material S6). |

|||||||||

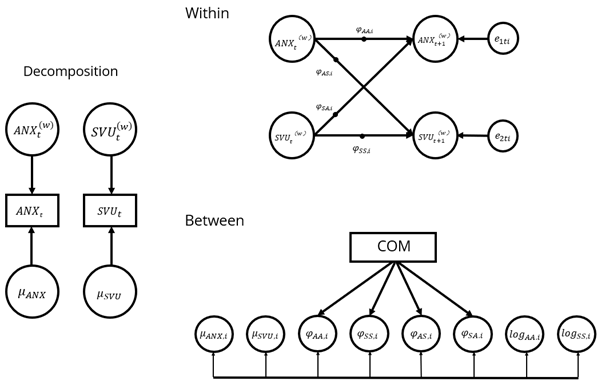

Figure 2. Moderating Effect of Upward Social Comparisons on the

Relationship Between Passive Short Video Use and Anxiety Symptoms.

Moderating Role of Upward Social Comparison

As shown in Table 2, upward social comparison significantly moderated the within-person effect of passive short video use on anxiety symptoms (β = −.162, 95% CI [−.310, −.013]). A simple slopes analysis (see Figure 2) revealed that individuals with higher levels of upward social comparison experienced increased anxiety symptoms during periods of elevated passive short video use, whereas those with lower levels of upward social comparison experienced decreased anxiety symptoms under similar conditions. This moderation effect was not observed in active short video use (β = −.174, 95% CI [−.394, .049]) nor total usage time (β = −.069, 95% CI [−.210, .066]).

Moreover, upward social comparison did not significantly moderate the within-person effects of anxiety symptoms on subsequent short video use. Specifically, no significant moderation effects were found for anxiety symptoms predicting active short video use (β = .031, 95% CI [−.090, .160]), passive short video use (β = −.134, 95% CI [−.295, .034]), or short video usage time (β = −.050, 95% CI [−.196, .095]).

Discussion

Previous studies have predominantly utilized cross-sectional data to evaluate the relationship between short video use and anxiety symptoms. However, the bidirectional longitudinal association between short video use and anxiety symptoms, and the moderating role of upward social comparison tendencies, remains unexamined. To address this gap, the present study employed the ESM and constructed a DSEM to separate within- and between-person effects to determine whether upward social comparison moderates these relationships. The findings suggested that at the within-person level, no significant bidirectional effects between short video use (i.e., active short video use, passive short video use, and total usage time) and anxiety symptoms were observed. However, upward social comparison significantly moderated the within-person effect of passive short video use on anxiety symptoms. Specifically, individuals with higher levels of upward social comparison experienced increased anxiety symptoms during periods of passive short video use. Conversely, those with lower levels of upward social comparison experienced fewer anxiety symptoms. No other significant moderating effects of upward social comparison were found in the cross-lagged relationships between short video use and anxiety symptoms.

Short Video Use and Daily Anxiety Symptoms

Contrary to Hypothesis 1, at the within-person level there were no significant bidirectional effects between short video use and anxiety symptoms. These findings are consistent with previous studies (e.g., Beeres et al., 2021; Coyne et al., 2020) and extend their implications to daily short video use and different usage patterns. Specifically, neither active nor passive short video use, nor overall usage time, predicted subsequent changes in anxiety symptoms. It is likely that the cross-lagged effects between daily short video use and anxiety symptoms may be confounded by other factors, such as problematic short video use (Qu et al., 2024; C. Zhu et al., 2024). According to the opponent-process theory (Solomon, 1980), positive and negative reinforcement are temporally linked. Individuals may engage in short video use to alleviate anxiety and experience short-term pleasure (Li et al., 2025). In this context, both active and passive short video use, as well as overall usage time, may act as positive reinforcement, temporarily reducing anxiety symptoms.

However, this short-term relief may be followed by negative emotional states such as withdrawal (Tian et al., 2023), which can increase the risk of developing addictive behaviors (Qu et al., 2024). Such addictive tendencies may offset the potential benefits of social media use (Boer et al., 2022) and contribute to adverse mental health outcomes (Chao et al., 2023; Qu et al., 2024). For example, prior research has found that the negative association between instant messaging behavior and life satisfaction disappeared after controlling for problematic social media use (Boer et al., 2022). These mechanisms may help explain why no significant effects were observed between short video use and anxiety symptoms.

Moreover, changes in anxiety symptoms did not predict subsequent short video use. A possible explanation may be that in the digital age, emerging adults increasingly use social media as a means of maintaining and enhancing peer relationships (Scott et al., 2017). Short video and social media use have become normalized behaviors (Boer et al., 2020; Pew Research Center, 2018), suggesting that daily fluctuations in short video use may reflect habitual use rather than a coping response to anxiety symptoms.

Moderation of Upward Social Comparison

The results revealed that upward social comparison significantly moderated the within-person effect of passive short video use on anxiety symptoms, providing partial support for Hypothesis 2. Specifically, individuals with high levels of upward social comparison experienced increased anxiety symptoms following passive short video use, whereas those with low levels showed reduced anxiety symptoms. According to the differential susceptibility to media effects model (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013), media effects are shaped by individual differences. Individuals high in upward social comparison are typically more sensitive to others and more uncertain about their self-concept (Buunk & Gibbons, 2006). They may seek to clarify their self-concept by comparing themselves with others (Lee, 2014). However, viewing idealized content during passive short video use may precipitate feelings of malicious envy and inferiority (Pan et al., 2023). Even in the case of benign envy which can motivate self-improvement (Cramer et al., 2016), such comparisons may still induce stress (Lockwood & Kunda, 1997) and anxiety as individuals strive to close the perceived gap between themselves and others. Moreover, because passive use lacks interaction, individuals high in upward social comparison may form inaccurate perceptions of others, which can further intensify existing anxiety symptoms.

In contrast, individuals with lower levels of upward social comparison may be less prone to such distorted perceptions and thus more likely to benefit from short video use. Specifically, they may use short videos as a means of escapism to relieve real-life stress and reduce anxiety (Scherr & Wang, 2021). Furthermore, in the present study, upward social comparison did not significantly moderate the relationship between active short video use and anxiety symptoms. One possible explanation for this finding is that the positive feedback gained through interactive engagement during active use (Marengo et al., 2021) may buffer against anxiety symptoms, even for individuals with high upward social comparison tendencies.

The results showed that upward social comparison did not significantly moderate the effect of anxiety symptoms on subsequent short video use. It is likely that individuals high in upward social comparison may already use social media more frequently than those low in comparison orientation (Vogel et al., 2015), making their usage patterns relatively stable regardless of their anxiety levels. Conversely, for individuals low in upward social comparison, the relatively reduced baseline usage may limit the observable effects of anxiety on short video use. Given the absence of significant moderating effects in this direction, future research is needed to explore this association more thoroughly and validate these interpretations.

Limitations and Future Studies

Several potential limitations within the present study should be noted. First, the study focused on anxiety symptoms, although previous research has indicated that depressive symptoms may also be negatively impacted by short video use (Thorisdottir et al., 2019; W. Zhu et al., 2023). Future research should consider investigating both anxiety and depression to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the psychological consequences associated with short video usage. Second, while this study assessed the time and frequency of short video use, it did not account for the specific content of the videos. Prior studies have demonstrated that different types of short video content can exert distinct influences on mental health (Wu et al., 2021). Future research could classify short video content (e.g., entertainment, educational, news, or motivational) to investigate whether different content types have differential effects on anxiety symptoms. Finally, this study assessed upward social comparison only at the trait level. However, upward social comparison is a context-sensitive psychological process that may vary across situations, particularly in social media and short video environments. For instance, Midgley et al. (2021) found that frequency of upward social comparisons increases with greater time spent on social media, contributing to poorer mental health outcomes. Employing dynamic or state-level assessments in future studies may also better capture situational fluctuations in upward social comparison and provide a more fine-grained understanding of its moderating role in the relationship between short video use and anxiety.

Conclusion

The findings obtained revealed no significant bidirectional relationship between short video use and anxiety symptoms at the within-person level, potentially challenging prevailing concerns about the psychological harm of short video consumption. Notably, upward social comparisons moderated the within-person effects of passive short video use on anxiety symptoms. Individuals with a high tendency for upward social comparisons tended to experience increased anxiety symptoms when engaging in passive short video use, however, those with lower levels of upward social comparison reported fewer anxiety symptoms. This may provide an explanation as to why previous studies failed to detect a within-person effect between short video use and anxiety symptoms. Moreover, the results highlighted the moderating role of upward social comparisons in social media use and provided practical implications for preventing anxiety symptoms associated with short video consumption, particularly by targeting the reduction of upward social comparison tendencies. Overall, the findings suggest that although short video use may not directly increase daily anxiety, its psychological impact depends on individual differences in social comparison. Specifically, individuals prone to upward comparison appear more vulnerable to anxiety during passive consumption of short video content in the digital age.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Use of AI Services

The authors declare they have used AI services for grammar correction and minor style refinements. They carefully reviewed all suggestions from these services to ensure the original meaning and factual accuracy were preserved.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Mengmeng Zhang, Yifan Wang, and Wenting Ye for their critical comments on this work. We also thank the students in our lab for their assistance in recruiting participants.

Ethical Considerations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Research Project Ethical Review Application Form, Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University (IRB protocol number: H24024).

Consent to Participate

All the participants provided informed consent and agreed to participate in this study.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32300887, PI: Zhaojun Teng) and the Chongqing Social Science Foundation (No. 2022YC075, PI: Zhaojun Teng).

Data Availability

The data supporting the current study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2026 Zhiwei Yang, Qian Nie, Xiaoqin Wang, Halley M. Pontes, Zhaojun Teng