Instagram Passive Active Use Measure (iPAUM): Development, validation and relation to self-esteem

Vol.20,No.1(2026)

This preregistered study aimed to design and validate a questionnaire which measures passive and active Instagram use (iPAUM), and to explore its connection to users’ self-esteem levels. While Instagram, as an image-based social media platform, shares common features with other social networking sites (SNS) in enabling sharing of information and social interaction, its emphasis on visual content and specific digital features, such as algorithmic exposure to strangers’ content and public and one-directional interaction, may influence user experiences differently compared to other SNSs. Individual users interact with Instagram in a variety of ways. Consequently, studies that rely on general use measures, such as the time spent on Instagram, often yield mixed results in regard to psychological outcomes, as these measures do not account for variability in use. To address these nuances, a new scale for Instagram behaviours was created in two phases. In Study 1 (N = 289, Mage = 30.4, SD = 10.21), an 18-item questionnaire was developed, reflecting four categories of Instagram use: Active reacting, Active direct social, Active creating, and Passive use. The four-factor structure was established through exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and good internal reliability and validity were demonstrated. In Study 2 (N = 297, Mage = 29.6, SD = 9.8), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed on an independent sample to validate the factor structure, confirming the reliability and discriminant validity of the measure. In the second part of Study 2, the iPAUM was employed to investigate associations between the four types of Instagram use and self-esteem, and whether following strangers on Instagram moderates this relationship. Self-esteem was not significantly associated with most types of Instagram use, except for a negative association between self-esteem and active direct social use, which was moderated by the percentage of strangers followed. The findings confirm the importance of differentiating between various types of Instagram use. The iPAUM is a validated tool which provides a more nuanced view of Instagram use for future research.

Instagram; passive social media use; social networking sites; validation; self-esteem

Katrine B. Tølbøll

Department of Political Science, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark; TrygFonden’s Centre for Child Research, Department of Economics and Business Economics, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

Katrine B. Tølbøll is a PhD candidate at Aarhus University, Department of Political Science and a PhD Fellow at TrygFonden’s Centre for Child Research, Department of Economics and Business Economics, Aarhus University. She is an interdisciplinary social scientist with research interests in how online behaviors, such as social media use, impact youth mental health and well-being.

Jennifer Stead

Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, City St George’s, University of London, London, United Kingdom

Dr. Jennifer Stead is a Research Psychologist and Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Organisational Psychology at City St George's, University of London. Her research focuses on cyberpsychology, subjective well-being, and the effects of social media on individuals and society.

Anke C. Plagnol

Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, City St George’s, University of London, London, United Kingdom

Dr. Anke C. Plagnol is a Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) in Behavioural Economics at City St George's, University of London. She is an interdisciplinary social scientist with research interests in subjective well-being, female labour force participation, and life course studies.

Allcott, H., Braghieri, L., Eichmeyer, S., & Gentzkow, M. (2020). The welfare effects of social media. American Economic Review, 110(3), 629–676. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20190658

Binns, A. (2014). Twitter city and Facebook village: Teenage girls’ personas and experiences influenced by choice architecture in social networking sites. Journal of Media Practice, 15(2), 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682753.2014.960763

Bonsaksen, T., Thygesen, H., Leung, J., Lamph, G., Kabelenga, I., & Østertun Geirdal, A. (2024). Patterns of social media use across age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study across four countries. Social Sciences, 13(4), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040194

Browne, M. W. (2001). An overview of analytic rotation in exploratory factor analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 36(1), 111–150. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327906MBR3601_05

Burrow, A. L., & Rainone, N. (2017). How many likes did I get?: Purpose moderates links between positive social media feedback and self-esteem. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 69, 232–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2016.09.005

Cheng, C., Wang, H.-y., Sigerson, L., & Chau, C.-I. (2019). Do the socially rich get richer? A nuanced perspective on social network site use and online social capital accrual. Psychological Bulletin, 145(7), 734–764. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000198

Chou, H.-T. G., & Edge, N. (2012). “They are happier and having better lives than I am”: The impact of using Facebook on perceptions of others’ lives. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 15(2), 117–121. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0324

Clark-Keane, C. (2023, May 15). Instagram vs. Facebook for marketing: Everything you need to know. WordStream. https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2023/04/10/instagram-vs-facebook

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10(1), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868

Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A. A., Zurcher, J. D., Stockdale, L., & Booth, M. (2020). Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: An eight-year longitudinal study. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, Article 106160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106160

Crawford, S. L. (2023, September 1). Instagram Vs Facebook: The social media showdown. Inkbot Design. http://web.archive.org/web/20240424223540/https://inkbotdesign.com/instagram-vs-facebook/

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D.-w., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Dumas, T. M., Maxwell-Smith, M., Davis, J. P., & Giulietti, P. A. (2017). Lying or longing for likes? Narcissism, peer belonging, loneliness and normative versus deceptive like-seeking on Instagram in emerging adulthood. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2017.01.037

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

Faelens, L., Hoorelbeke, K., Cambier, R., van Put, J., Van de Putte, E., De Raedt, R., & Koster, E. H. W. (2021). The relationship between Instagram use and indicators of mental health: A systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 4, Article 100121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100121

Faraon, M., & Kaipainen, M. (2014). Much more to it: The relation between Facebook usage and self-esteem. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 15th International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration (IEEE IRI 2014) (pp. 87–92). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/IRI.2014.7051876

Fioravanti, G., Prostamo, A., & Casale, S. (2019). Taking a short break from Instagram: The effects on subjective well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(2), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0400

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2015). Exploring the relationships between different types of Facebook use, perceived online social support, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Social Science Computer Review, 34(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314567449

Gaol, L. A. L., Mutiara, A. B., Saraswati, N. L., Rahmadini, R., & Hilmah, M. A. (2018). The relationship between social comparison and depressive symptoms among Indonesian Instagram users. In Proceedings of the Universitas Indonesia International Psychology Symposium for Undergraduate Research (UIPSUR 2017) (pp. 130–137). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/uipsur-17.2018.19

Gerson, J., Plagnol, A. C., & Corr, P. J. (2017). Passive and Active Facebook Use Measure (PAUM): Validation and relationship to the reinforcement sensitivity theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 117, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.05.034

Godard, R., & Holtzman, S. (2024). Are active and passive social media use related to mental health, wellbeing, and social support outcomes? A meta-analysis of 141 studies. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 29(1), Article zmad055. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmad055

Goldsmith, A. H., Veum, J. R., & Darity, W. Jr. (1997). Unemployment, joblessness, psychological well-being and self-esteem: Theory and evidence. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 26(2), 133–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-5357(97)90030-5

Green, S. B. (1991). How many subjects does it take to do a regression analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 26(3), 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2603_7

Hair, J. F. Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Hancock, J., Liu, S. X., Luo, M., & Mieczkowski, H. (2022). Psychological well-being and social media use: A meta-analysis of associations between social media use and depression, anxiety, loneliness, eudaimonic, hedonic and social Well-Being. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4053961

Hanley, S. M., Watt, S. E., & Coventry, W. (2019). Taking a break: The effect of taking a vacation from Facebook and Instagram on subjective well-being. PLoS ONE, 14(6), Article e0217743. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217743

Harris, E., & Bardey, A. C. (2019). Do Instagram profiles accurately portray personality? An investigation into idealized online self-presentation. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 871. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00871

Ho, S. S., Lee, E. W. J., & Liao, Y. (2016). Social network sites, friends, and celebrities: The roles of social comparison and celebrity involvement in adolescents’ body image dissatisfaction. Social Media + Society, 2(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116664216

Hoffner, C. A., & Bond, B. J. (2022). Parasocial relationships, social media, & well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, Article 101306. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COPSYC.2022.101306

Howard, M. C. (2016). A review of exploratory factor analysis decisions and overview of current practices: What we are doing and how can we improve? International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 32(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2015.1087664

Hunt, M. G., Xu, E., Fogelson, A., & Rubens, J. (2023). Follow friends one hour a day: Limiting time on social media and muting strangers improves well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 42(3), 187–213. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2023.42.3.187

Johnson, B. K., & Knobloch‐Westerwick, S. (2017). When misery avoids company: Selective social comparisons to photographic online profiles. Human Communication Research, 43(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12095

Johnson, L. (2017, January 15). Filter focus: The story behind the original Instagram filters. TechRadar. https://www.techradar.com/news/filter-focus-the-story-behind-the-original-instagram-filters

Kemp, S. (2023, January 26). Digital 2023: Global overview report. DataReportal. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-global-overview-report

Kingsbury, M., Reme, B.-A., Skogen, J. C., Sivertsen, B., Øverland, S., Cantor, N., Hysing, M., Petrie, K., & Colman, I. (2021). Differential associations between types of social media use and university students’ non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 115, Article 106614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106614

Kyriazos, T. A. (2018). Applied psychometrics: Sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in General. Psychology, 9(8), 2207–2230. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2018.98126

Le Blanc-Brillon, J., Fortin, J.-S., Lafrance, L., & Hétu, S. (2025). The associations between social comparison on social media and young adults’ mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, Article 1597241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1597241

Liu, D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2016). Social networking online and personality of self-worth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 64, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.06.024

Lup, K., Trub, L., & Rosenthal, L. (2015). Instagram #Instasad?: Exploring associations among Instagram use, depressive symptoms, negative social comparison, and strangers followed. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(5), 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0560

McComb, C. A., Vanman, E. J., & Tobin, S. J. (2023). A meta-analysis of the effects of social media exposure to upward comparison targets on self-evaluations and emotions. Media Psychology, 26(5), 612–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2023.2180647

Meier, A., & Krause, H.-V. (2023). Does passive social media use harm well-being?: An adversarial review. Journal of Media Psychology, 35(3), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000358

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Orben, A., Meier, A., Dalgleish, T., & Blakemore, S.-J. (2024). Mechanisms linking social media use to adolescent mental health vulnerability. Nature Reviews Psychology, 3(6), 407–423.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-024-00307-y

Ozimek, P., & Bierhoff, H.-W. (2020). All my online-friends are better than me – three studies about ability-based comparative social media use, self-esteem, and depressive tendencies. Behaviour & Information Technology, 39(10), 1110–1123. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1642385

Phu, B., & Gow, A. J. (2019). Facebook use and its association with subjective happiness and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.020

R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Revelle, W. (2019). psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research (Version 1.9.12). Northwestern University. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

Romero Saletti, S. M., Van den Broucke, S., Billieux, J., Karila, L., Kuss, D. J., Rivera Espejo, J. M., Sheldon, P., Lang, C. P., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Zollo, P., Courboin, C., Diez, D., Madison, T. P., Ramos-Diaz, J., Eguia Elias, C. A., & Otiniano, F. (2023). Development, psychometric validation, and cross-cultural comparison of the “Instagram Motives Questionnaire” (IMQ) and the “Instagram Uses and Patterns Questionnaire” (IUPQ). Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 12(1), 105–127. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2022.00088

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pjjh

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Ryding, F. C., Harkin, L. J., & Kuss, D. J. (2024). Instagram engagement and well-being: The mediating role of appearance anxiety. Behaviour & Information Technology, 44(3), 446–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2024.2323078

Saiphoo, A. N., Halevi, L. D., & Vahedi, Z. (2020). Social networking site use and self-esteem: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Individual Differences, 153, Article 109639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109639

Salvalaggio, E. (2024, December 2). Your ultimate guide to the Instagram explore page. Later. https://later.com/blog/how-to-get-on-instagram-explore-page/

Schreurs, L., Meier, A., & Vandenbosch, L. (2023). Exposure to the positivity bias and adolescents’ differential longitudinal links with social comparison, inspiration and envy depending on social media literacy. Current Psychology, 42(32), 28221–28241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03893-3

Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2010). A beginner's guide to structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Statista. (2023, February 14). Most popular social networks worldwide as of January 2023, ranked by number of monthly active users. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

Stefanski, R. (2021, July 30). 7 Differences between Instagram and Facebook posts social media marketers need to know. Crowdfire. https://read.crowdfireapp.com/2021/07/30/7-differences-between-instagram-and-facebook-posts-social-media-marketers-need-to-know-2/

Taber, L., & Whittaker, S. (2018). Personality depends on the medium: Differences in self-perception on Snapchat, Facebook and offline. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–13). https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3174181

Tinakon, W., & Nahathai, W. (2012). A comparison of reliability and construct validity between the original and revised versions of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Psychiatry Investigation, 9(1), 54–58. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2012.9.1.54

Trifiro, B. (2018). Instagram use and its effect on well-being and self-esteem [Master’s thesis, Bryant University]. https://digitalcommons.bryant.edu/macomm/4/

Trifiro, B. M., & Prena, K. (2021). Active Instagram use and its association with self-esteem and well-being. Technology, Mind, and Behavior, 2(3), 266–270. https://doi.org/10.1037/TMB0000043

Valkenburg, P. M., Beyens, I., Meier, A., & Vanden Abeele, M. M. P. (2022). Advancing our understanding of the associations between social media use and well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, Article 101357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101357

Valkenburg, P. M., Koutamanis, M., & Vossen, H. G. M. (2017). The concurrent and longitudinal relationships between adolescents’ use of social network sites and their social self-esteem. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.008

Valkenburg, P. M., van Driel, I. I., & Beyens, I. (2022). The associations of active and passive social media use with well-being: A critical scoping review. New Media & Society, 24, 530–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211065425

Verduyn, P., Gugushvili, N., & Kross, E. (2022). Do social networking sites influence well-being? The extended active-passive model. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 31(1), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211053637

Verduyn, P., Ybarra, O., Résibois, M., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2017). Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11(1), 274–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12033

Vogels, E. A., Gelles-Watnick, R., & Massarat, N. (2022, August 10). Teens, social media and technology 2022. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/

Wang, J.-L., Wang, H.-Z., Gaskin, J., & Hawk, S. (2017). The mediating roles of upward social comparison and self-esteem and the moderating role of social comparison orientation in the association between social networking site usage and subjective well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 771. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00771

Wang, R., Yang, F., & Haigh, M. M. (2017). Let me take a selfie: Exploring the psychological effects of posting and viewing selfies and groupies on social media. Telematics and Informatics, 34(4), 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.07.004

Ward, A. (2024, March 18). Instagram news and updates. Metricool. https://metricool.com/instagram-news/

Webster, D., Dunne, L., & Hunter, R. (2021). Association between social networks and subjective well-being in adolescents: A Systematic Review. Youth & Society, 53(2), 175–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X20919589

Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(6), 913–934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164413495237

Woodward, M. J., McGettrick, C. R., Dick, O. G., Ali, M., & Teeters, J. B. (2025). Time spent on social media and associations with mental health in young adults: Examining TikTok, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, Snapchat, and Reddit. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 10(3), 661–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-024-00474-y

Zhong, C., Chan, H.-w., Karamshuk, D., Lee, D., & Sastry, N. (2017). Wearing many (social) hats: How different are your different social network personae? arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1703.04791

Zote, J. (2023, March 6). Instagram statistics you need to know for 2023. Sprout Social. https://sproutsocial.com/insights/instagram-stats/

Authors´ Contribution

Katrine B. Tølbøll: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft. Jennifer Stead: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, supervision, writing—review & editing. Anke C. Plagnol: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, supervision, funding acquisition, writing—review & editing.

Editorial record

First submission received:

September 17, 2024

Revision received:

February 2, 2025

July 22, 2025

November 10, 2025

Accepted for publication:

November 11, 2025

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

Social networking sites (SNSs) have increased in popularity over the last few decades. In 2023, more than 4.7 billion people across the globe were estimated to be social media users, spending an average of 2 hours and 31 minutes a day across a number of platforms (Kemp, 2023). SNSs play an integral role in modern social interactions, influencing how people connect and share experiences. Early research on SNSs has mainly focused on understanding how long and how often people engage with these platforms, relying on general use measures that capture the frequency of SNS use. However, a growing body of literature emphasises the importance of examining how and why people spend their time on SNSs, as this provides a more nuanced picture of individual use (Valkenburg, Beyens et al., 2022; Webster et al., 2021).

User engagement on SNSs is commonly categorised into two broad categories: passive and active use (Valkenburg, van Driel, et al., 2022; Verduyn et al., 2017). Verduyn et al. (2017) defined passive use as the act of observing other users’ content without engaging in direct exchanges. Examples of passive use include scrolling through newsfeeds or looking at other users’ profiles or pictures without liking them or commenting on them. Active use, on the other hand, involves activities that facilitate direct interactions with other users. This includes both direct communication (e.g., one-on-one interactions) and nontargeted interactions (e.g., broadcasting). Active SNS use often involves the creation of new content, such as writing and posting a status update or sending a direct message to another user (Verduyn et al., 2017). In a recent scoping review, Valkenburg, van Driel, et al. (2022) advocated for more nuanced assessments of social media use, contrary to general use measures such as the time spent on SNSs. In line with this suggestion, the present study aims to develop and validate a new measure of Instagram use that reflects active and passive use patterns and accounts for Instagram’s image-based design features. In addition, the study provides an example of how this newly developed scale may be associated with psychological outcomes by examining its relationship with users’ self-reported levels of self-esteem.

Previous SNS Use Scales

Early research on SNS use and its connection to psychological outcomes almost exclusively focused on Facebook, but more recent studies also consider other social media platforms. For instance, Hancock et al. (2022) found that studies on Facebook accounted for 63% of all effect sizes in their comprehensive review of 1,279 effect sizes from 226 studies. While Facebook is still the most popular SNS (Statista, 2023), more adolescents are using Instagram as one of their preferred platforms (Vogels et al., 2022), which highlights the need to expand research to other SNSs. This is especially relevant given the potential psychological consequences of SNS use (Faelens et al., 2021; Saiphoo et al., 2020). Furthermore, studying different SNSs is important as image-based content compared to text-based content shared on SNSs has shown stronger negative associations with users’ mood and subjective well-being (B. K. Johnson & Knobloch‐Westerwick, 2017). In addition, people tend to use different SNSs in distinct ways, tailoring their self-presentation based on the specific features of each platform, such as images vs text-based options. For instance, in an early study, teenage girls stated that their Facebook profiles represented the “real them” compared to X (formerly Twitter), Formspring, and Ask.fm (Binns, 2014). The latter two were early social networking sites where users could ask and respond to questions anonymously. More recent research that explored self-presentation across more contemporary platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, LinkedIn, and Facebook, has echoed these findings (e.g., Taber & Whittaker, 2018; Zhong et al., 2017). Zhong et al. (2017) showed that users adapt their profile images and descriptions depending on the platform’s social expectations, while Taber and Whittaker (2018) demonstrated that personality traits are expressed differently across platforms based on their design features.

However, the widespread use of non-validated, self-created scales across studies undermines the comparability, reliability, and replicability of the evidence on active and passive SNS use. For instance, Valkenburg, van Driel, et al. (2022) found that 90% of the studies they reviewed used their own operationalisations of passive and active SNS use. Furthermore, the dichotomy of categorising SNS activities into only active and passive use might not fully capture the nuances of SNS engagement. Valkenburg, van Driel, et al. (2022) conducted a critical review and found that a substantial number of studies do not support the hypothesised link between active and passive SNS use and well-being, suggesting that this simple active-passive dichotomy may be insufficient to capture these dynamics.

In an earlier study, Gerson et al. (2017) developed and validated the Passive Active Use Measure (PAUM) for Facebook. The authors stated that their research was motivated by the heretofore lack of Facebook use measures that addressed the variety of ways users interact with the site. In addition to active and passive Facebook behaviour, they found that active use can further be categorised into two groups: active social and active non-social usage (Gerson et al., 2017). Active social use consists of activities where the user actively engages with other users with the intent of socialising. These activities include commenting on other users’ content or sending direct messages to others. In contrast, active non-social use is defined as activities where users are creating content, but not with the intent to actively interact with other users (e.g., tagging users in pictures). Given these findings, accounting for Instagram’s unique image-based features and how users interact with them may offer a more comprehensive understanding of user behaviours and potential links to psychological outcomes. The scale developed in this paper considers various dimensions of active Instagram use in addition to passive use. The following section outlines the characteristics that distinguish Instagram from other SNSs, followed by a discussion of the literature supporting the development of this new scale.

Instagram’s Design Features

Instagram, which is owned by Meta, is currently one of the most popular image-based SNSs with 2 billion unique monthly users (Zote, 2023). Instagram differs from other SNSs by dedicating its interface solely to visual content like photos and short videos, and many young people use Instagram as their primary SNS (Zote, 2023). Unlike other SNSs, such as X or Facebook, Instagram focuses on image-centred content-sharing, and, thus, users cannot post a written text without a photo or video. Created content is published on profiles and can be shown on newsfeeds, where other users can interact and provide feedback by sharing, liking or commenting, enabling visible social validation.

Although features, such as personal curated profiles, content feeds, and options to follow other users, can be found across most SNS platforms, Instagram’s platform design amplifies specific visual features that may enhance its influence on users’ psychological outcomes. As highlighted by Orben et al. (2024), SNS design options shape how users engage with the platform by emphasising, to various extents, visibility, quantifiability, and personalisation, which can trigger processes of social evaluations. In contrast to many other SNSs, the default setting is to have public profiles on Instagram, making it possible to interact with content posted by people whom the user does not know personally. Unlike, for instance, on Facebook where becoming friends is reciprocal, following someone on Instagram is often unidirectional (Clark-Keane, 2023; Crawford, 2023). This design feature increases users’ exposure to unfamiliar audiences and makes public visibility a central component of Instagram engagement. Users may feel heightened pressure to manage and curate their online appearances, presenting an idealised online self (e.g., Harris & Bardey, 2019), driven by Instagram’s social feedback metrics, such as likes, comments, and follower count, with the latter always being publicly visible. This may lead to “like-seeking” behaviour, such as using filters to improve images (Dumas et al., 2017). This constant visibility makes evaluations of oneself both persistent and public (Orben et al., 2024). Furthermore, it is easy to engage with the content of celebrities, prominent individuals, and strangers, as discussed further below.

Another feature that is not common across SNS platforms is the explore page (Salvalaggio, 2024; Stefanski, 2021), which is similar to the regular news feed, where the user can see content posted by the users they follow (as, e.g., seen on Facebook and X). However, the explore page is powered by algorithm-based content recommendations that show users content from accounts they are not currently following. In other words, Instagram users are not solely exposed to content from people the user knows or follows. This algorithmic personalisation can create curated realities that reinforce upward social comparisons and perceived inadequacy, especially when curated online personas are interpreted as authentic representations of others’ lives (Schreurs et al., 2023). The editability of Instagram content further intensifies this process by allowing users to construct idealised online personas. This specific feature is particularly salient on Instagram as it originally offered users the option to beautify their images and videos by using various filters provided by Instagram (L. Johnson, 2017).

Given Instagram’s distinct design features that amplify social comparisons, feedback sensitivity, and self-presentation pressures, understanding its effects on users’ psychological outcomes requires platform-specific measures. As highlighted by Orben et al. (2024), social media’s psychological effects emerge not from platform design alone but from the interaction between platform features and user behaviour. However, research on Instagram use and its psychological effects has been marked by measurement inconsistencies, with many studies relying on unvalidated, single-item self-report measures, limiting the reliability of findings (Faelens et al., 2021). Additionally, studies often reduce Instagram use—or social media use in general—to general engagement measured as the time spent on the platform (e.g., Coyne et al., 2020; Woodward et al., 2025), overlooking the complexity of user behaviour.

These limitations have made it challenging to draw consistent conclusions about the platform’s psychological effects. Acknowledging these challenges, Faelens et al. (2021) suggested in their comprehensive review that future research would benefit from a well-validated and reliable measure of Instagram use that could be applied consistently across studies. In this context, the development of the iPAUM aims to fill this gap by offering a platform-specific measure designed to capture distinct types of Instagram behaviours.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity for the new iPAUM scale is established by demonstrating meaningful correlations with variables that are theoretically and empirically linked to Instagram engagement patterns. Subjective well-being and Instagram intensity are the focus for this purpose, as both concepts have been linked to previous measures of SNS use in the literature (e.g., Gerson et al., 2017).

Early research linked passive SNS use to lower levels of well-being while active use of SNSs has been positively associated with well-being (Verduyn et al., 2017). A recent meta-analysis of 141 studies found a positive association between active SNS use and well-being (r = .15) and positive affect (r = .11; Godard & Holtzman, 2024). J.-L. Wang et al. (2017) investigated passive SNS use and its associations with subjective well-being, focusing on the mediating roles of making comparisons to other users and self-esteem. Using Qzone and WeChat (popular SNSs in China), they found that passive SNS use was positively related to feeling worse when comparing oneself to others, which was related to users’ lower self-esteem and consequently their subjective well-being.

In contrast, other studies have indicated that active use can result in negative outcomes under certain conditions, such as cyberbullying or a lack of reciprocity in interactions (Verduyn et al., 2022), while passive use can foster positive experiences like inspiration (Meier & Krause, 2023). However, studies often suggest positive associations between active use and a number of positive psychological outcomes. For instance, Trifiro and Prena (2021) found that active Instagram users reported higher levels of well-being and self-esteem. This relationship was mediated by the intensity of Instagram use. Instagram intensity reflects the overall level of engagement with the platform and the user’s motivation for using it. It is thus expected that levels of Instagram intensity are positively associated with active engagement styles, reflecting a more participatory and emotional connection with the platform. This relationship has already been confirmed for Facebook (Gerson et al., 2017). Including Instagram intensity as a criterion variable allows validation of the iPAUM scale against a behavioural and emotional measure of Instagram use. After establishing the criterion validity of the iPAUM, the subsequent analyses demonstrate how the sub-scales may relate differently to a psychological outcome measure that is frequently examined in the context of SNS use, namely self-esteem.

SNS Use and Self-Esteem

As people are spending more time on SNSs, it is important to look at how SNS use might be related to psychological factors. Previous studies have shown that SNS use is associated with users’ level of self-esteem (Saiphoo et al., 2020); however, this relationship can be conceptualised in different ways. Research suggests that self-esteem can either be boosted or reduced when using SNSs. Comparing oneself to other users via posted content on SNSs can reduce self-esteem (Le Blanc-Brillon et al., 2025; McComb et al., 2023), while receiving feedback on posted content can enhance self-esteem (Burrow & Rainone, 2017). Self-esteem can also be the motive to use SNSs. The social comparison hypothesis suggests that people who express lower levels of self-esteem feel more comfortable using SNSs compared to real-life interactions (Liu & Baumeister, 2016). Furthermore, the rich-get-richer hypothesis suggests that people who report higher levels of self-esteem use SNSs to socialise in the same way they otherwise would in real-life settings to further boost their self-esteem (Cheng et al., 2019; Faraon & Kaipainen, 2014). R. Wang et al. (2017) differentiated between viewing selfies and posting selfies on Instagram and Facebook, which fits the definition of passive and active use respectively, and they found that looking at selfies was associated with lower levels of self-esteem. In contrast, posting selfies was not significantly associated with levels of self-esteem. Trifiro (2018) found a significant relationship between active Instagram use and subjective well-being and self-esteem. However, it was argued that Instagram intensity, rather than the type of Instagram use, shaped the relationship between Instagram use and self-esteem, as the associations between active Instagram use and subjective well-being and self-esteem were not significant when controlling for Instagram intensity. It is important to note that Trifiro (2018) employed the PAUM (Gerson et al., 2017), which was specifically developed for Facebook. As Instagram and Facebook differ in their key digital features, it is important to use a measure that has been specifically developed for Instagram, as otherwise important aspects might be lost in the adaptation of a measure from one SNS to another.

Overall, findings from studies that have explored associations between overall SNS use and self-esteem are mixed. Some studies found a negative association between frequent SNS use and levels of self-esteem, while other studies found that more frequent SNS use is associated with higher levels of self-esteem (Valkenburg et al., 2017). A recent meta-analysis found an overall small, negative, and significant association between SNS use and self-esteem (Saiphoo et al., 2020). Saiphoo et al. (2020) suggested that the small effect size stems from the mixed results found in the literature. They argued that future research should focus on investigating different types of SNS use, e.g., splitting SNS use into passive and active categories. As people use SNSs with different motives and therefore possibly receive different outcomes, it is plausible that the direction of the association between self-esteem and SNS use might be related to whether users engage on these platforms mostly actively or passively.

Self-esteem is thus a good psychological measure to demonstrate whether a more nuanced measure of Instagram, with several sub-scales of active and passive use, provides additional insights into the relationship between reported self-esteem and Instagram engagement compared to a general use measure.

Following Strangers on Instagram

Previous studies highlighted that following strangers, i.e., people whom the user does not know personally, may amplify negative social comparisons due to the curated nature of their content (Hunt et al., 2023; Lup et al., 2015). Research has further shown that users who follow a higher proportion of strangers are more likely to perceive others as leading better lives (Chou & Edge, 2012) and experience increased feelings of inadequacy (Gaol et al., 2018). Some users even develop parasocial relationships with celebrities and influencers on SNSs in which they form a one-way socio-emotional connection with the social media personality with varying consequences for their well-being, including positive outcomes such as feelings of connection but also potential negative outcomes through social comparison (Hoffner & Bond, 2022). These dynamics suggest that the percentage of strangers followed could play a significant role in users’ patterns of engagement on Instagram.

Control Variables

Gender and age have routinely been shown to be important variables to consider when investigating self-esteem levels and SNS behaviour, as different age groups and genders interact with SNSs differently (Fioravanti et al., 2019; Frison & Eggermont, 2015; J.-L. Wang et al., 2017). Income and employment status are often considered in relation to self-esteem; especially unemployment has been found to be associated with lower self-esteem (Goldsmith et al., 1997). Further, employment status could be associated with the time available to spend on SNSs; e.g., an unemployed individual might have more time available to spend on SNSs compared to someone who is employed full-time. Lastly, research on SNSs has shown how people of various educational backgrounds use SNSs differently; thus, education level might be associated with different SNS usage (Bonsaksen et al., 2024).

Study Aims

This paper aims to develop and validate a new psychometric scale to assess passive and active Instagram use (iPAUM), similar to the Passive Active Use Measure (PAUM) for Facebook (Gerson et al., 2017), which is widely used in the literature on SNS use (e.g., Allcott et al., 2020; Kingsbury et al., 2021). To demonstrate how the iPAUM may be applied to relate psychological outcomes to SNS engagement, associations between passive and active Instagram use and levels of self-esteem are examined. The paper includes two studies. In Study 1, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) is employed to develop the iPAUM. The second study focuses on validating the measure using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). In the second part of Study 2, the same data are used to explore associations between the factors of the newly developed iPAUM and levels of self-esteem.

Based on the findings from the literature discussed above, the following hypotheses are formulated and tested in the second part of Study 2 (these correspond to the first parts of H1 and H2 in the preregistration):

H1: Passive Instagram use is associated with lower levels of self-esteem. This association is moderated by the percentage of strangers followed.

H2: Active Instagram use is associated with higher levels of self-esteem. This association is moderated by the percentage of strangers followed.

In particular, it is hypothesised that the percentage of strangers followed weakens the association between active Instagram use and self-esteem, while, in contrast, the percentage of strangers followed strengthens the association between passive Instagram use and self-esteem.

Study 1

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

The aim of Study 1 was to adapt the PAUM for Facebook (Gerson et al., 2017) to create a new multi-item scale that measures active and passive Instagram use, the iPAUM. The results of the EFA were then subjected to replication with a new sample in Study 2.

Methods

Data

In July 2020, 289 respondents (80 males, 207 females, 1 did not specify their gender, Mage = 30.4, SD = 10.21) who used Instagram were recruited online through Prolific Academic over a 7-day period. Ethics approval for this study and Study 2 was obtained from the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at City St George's, University of London. Respondents were only included in the sample if they were older than 18 and used Instagram. Respondents accessed the study through the survey site Qualtrics, where they gave informed consent before completing the questionnaire. The survey contained measures for several studies including questions assessing Facebook behaviour and SNS use during the Covid-19 pandemic. Respondents were paid a compensation of £1.50 for their time (median time = 15 minutes). The respondents were aged between 18 and 64, with most reporting full-time employment (55% employed, 13% unemployed, 8% on furlough, 18% students, 1% retired, 2% long-term sick or disabled, and 3.5% other). Most respondents had obtained a university degree (69% had a bachelor’s degree, 29% had a master’s degree, and 2% had a doctoral degree).

To ensure the quality of the data, attention checks were used in the survey. The questionnaire included two attention checks, asking the respondents to Please select ‘Rarely (25%)’ for this question and Please select ‘Somewhat disagree’ for this question. The attention checks were part of two matrix-style questions to ensure that respondents were reading the questions. Those who failed both attention checks were disqualified and were not able to finish the questionnaire. One respondent failed both attention checks and was excluded from the dataset, thus resulting in the aforementioned sample of 289 respondents. The final sample size of 289 participants met the recommended guidelines for exploratory factor analysis, which suggest a minimum of 5–10 participants per item and/or a total sample size of at least 200 (Costello & Osborne, 2005). The study was preregistered on As Predicted (https://aspredicted.org/rh2z-mf39.pdf). The preregistration included details on the key dependent variables, hypotheses, and the statistical analysis. Deviations from the preregistration are discussed in the general discussion below.

Measures

The iPAUM. The new measure of passive and active Instagram use, the iPAUM, was created by adapting the PAUM for Facebook developed by Gerson et al. (2017). The PAUM for Facebook consists of 13 questions which categorise various Facebook activities into three categories: Active-social, Active-nonsocial, and passive use. Respondents report how frequently they perform each activity on a scale ranging from (1) Never (0% of the time) to (5) Very frequently (Close to 100% of the time). The PAUM for Facebook was used as the basis for creating the iPAUM, adding new items specific to Instagram, and removing items which were not relevant for Instagram use. The iPAUM shares the same format as the PAUM for Facebook by asking respondents: How frequently do you perform the following activities when you are on Instagram. Answer categories are presented on the same 5-point scale, ranging from (1) Never (0% of the time) to (5) Very frequently (Close to 100% of the time). However, as Facebook and Instagram facilitate different platform-specific activities, 5 items (Posting status updates, Chatting on FB chat, Creating or RSVPing to events, Tagging photos, Tagging videos), were dropped from the PAUM for Facebook as these features are not available on Instagram. To capture the major features of Instagram, 16 new items were added to the iPAUM. The inclusion of the new items was guided by Instagram’s documented features at the time of data collection (Ward, 2024).

The PAUM for Facebook contains items for passive and active use of the Facebook newsfeed. Instagram has both a newsfeed and an explore page, thus, for the iPAUM, two new items were added to investigate how users actively or passively engage with the explore page. Eight new items were added to the iPAUM to explore how people engage with stories and live streams. On Instagram content can be forwarded to other users’ direct message inboxes. Two new items, for picture and video sharing, were added to reflect these Instagram features in addition to sending direct messages to other users. Lastly, four items were added to reflect the Instagram activity of liking content. In contrast to commenting on content, liking is less of a social activity in nature. Thus, by separating commenting and liking, it is possible to explore if these items load onto different factors. In conclusion, the iPAUM consists of 26 items, describing all major features of Instagram and how people can engage with them (see Table 2 for the full list of 26 items).

Subjective Well-Being. To validate the iPAUM, two measures of subjective well-being, namely hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, were included. Hedonic well-being emphasises pleasure and the avoidance of pain, while eudaimonic well-being focuses on meaning, self-realisation, and full functioning (Ryan & Deci, 2001). These two concepts of subjective well-being were measured with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985) and the Flourishing Scale (Diener et al., 2010). The SWLS assesses hedonic well-being by asking respondents to rate their agreement with 5 statements reflecting various aspects of life satisfaction; for instance: In most ways my life is close to my ideal. Responses were given on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. The Flourishing Scale includes 8 statements that are assessed on a 7-point Likert scale with responses ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. This scale captures the respondent’s eudaimonic well-being through statements such as I lead a purposeful and meaningful life and My social relationships are supportive and rewarding.

Instagram Intensity. Instagram intensity, which was also included to validate the iPAUM, was measured using the adapted version of the multi-dimensional Facebook intensity scale (adapted by Trifiro, 2018, for Instagram from Ellison et al., 2007, for Facebook use). Instagram intensity captures a user’s engagement with Instagram in everyday life and their motivation for using Instagram. Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. See Table 1 for the internal reliability and descriptive statistics for the measures used for validation.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Reliability for Study 1 Measures Used for Validation.

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

α |

|

Satisfaction with Life Scale |

22.0 |

6.4 |

5 |

34 |

.88 |

|

Flourishing Scale |

43.3 |

7.1 |

16 |

56 |

.90 |

|

Instagram Intensity |

2.9 |

0.9 |

0 |

4.5 |

.86 |

|

Note. N = 289, α = Chronbach’s alpha from Study 1 sample. |

|||||

Analytical Strategy

To perform the following analysis, R statistical software (R Core Team, 2018) was used, utilising the psych and lavaan packages (Revelle, 2019; Rosseel, 2012). To assess normality, each item of the iPAUM was tested using skewness and kurtosis thresholds, with values between −2 and +2 considered acceptable (Hair et al., 2021). All items, except for three, were normally distributed. Three items related to Instagram’s “live” function (Watching live stories, Broadcasting live stories, and Interacting with live stories) showed significant deviations from normality. Following this, all four items related to Instagram’s “live” function were removed, as maximum likelihood estimation assumes normally distributed variables. To investigate the latent factors of Instagram behaviour, maximum likelihood EFAs with two, three, four, and five-factor solutions using the oblique method were performed. To assess the factor structure of the iPAUM, items were considered to load strongly on a factor if their loadings were above .40, while cross-loadings were considered problematic if they exceeded .30, following guidelines by Howard (2016). First, the models were tested with an oblimin rotation, however, several items cross-loaded on multiple factors. A geomin rotation was applied instead, as also seen in Gerson et al. (2017). Geomin rotation is recommended when factor indications have strong loadings on several factors (Browne, 2001). Pearson’s correlations between the iPAUM factors, the two subjective well-being measures, and Instagram intensity were computed to establish discriminant and convergent validity. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, with α > .70 indicating acceptable reliability (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

Correlations were interpreted based on Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, where values above .50 were considered strong, between .30 and .50 moderate, and below .30 weak. In line with established models of multidimensional behaviour on social media (e.g., Meier & Krause, 2023; Verduyn et al., 2022), two- to five-factor solutions to empirically assess the latent structure of Instagram behaviours. This approach was grounded in the assumption that social media use consists of multiple interacting dimensions. The final factor solution was selected based on a combination of statistical fit indices and theoretical interpretability, ensuring that the retained factors captured distinct yet conceptually meaningful types of Instagram engagement.

Results

The results of the EFA indicated an inadequate model fit for the two-factor solution: χ2 = 664.28, df(151), p < .001, RMSR = .06, based on the conservative fit thresholds, where an RMSR value of < .05 suggests a good fit (Schumacker & Lomax, 2010, p. 76). The three-factor solution indicated a better fit: χ2 = 379.55, df(133), p < .001, RMSR = .05. The four-factor solution demonstrated an improvement: χ2 = 344.08, df(149), p < .001, RMSR = .04. The five-factor solution indicated a better fit: χ2 = 229.18, df(131), p < .001, RMSR = .03. However, none of the items loaded strongly onto the fifth factor. Therefore, it was decided that the four-factor solution was the most appropriate structure for the iPAUM.

The factor loading for item 10 cross-loaded between factor 1 and factor 4. Item 9 cross-loaded between factor 1 and factor 3. Item 14 and item 25 did not load onto any of the factors (cut-off ≤ .3). Items 9 and 10 exceeded the cut-off for cross-loadings (≤ .3) and were therefore excluded from the scale and further analysis. After items 9, 10, 14, and 25 were removed, the model fit for the four-factor solution improved: χ2 = 182.68, df(87), p < .001, RMSR = .04. See Table 2 for factor loadings, eigenvalues, and variances.

In conclusion, the iPAUM consists of four distinct factors. The first factor contains items which reflect active use, including active social use in a reactive manner. The factor includes items such as Commenting on other users’ stories, and Browsing the newsfeed actively (liking and commenting on other users’ posts). Following this, the factor was labelled “Active reacting”. The second factor consists of items related to passive Instagram use, such as Viewing photos (without liking or commenting), Browsing the explore page passively (without liking or commenting on posts), and Looking through a celebrity/influencer’s posts. The second factor was therefore labelled “Passive”. The third factor contains items for active Instagram use, which involve direct social engagement, such as Sending direct messages to other users and Forwarding photos to other users (or tagging other users in photos). The third factor was labelled “Active direct social”. The fourth factor includes items for active Instagram use where the user creates content such as Posting photos to your profile and Posting stories to your profile. The fourth factor was therefore labelled “Active creating”.

Table 2. Factor Loadings for the iPAUM.

|

iPAUM item |

Factor loading |

|||

|

Active reacting |

Passive |

Active direct social |

Active creating |

|

|

1. Posting photos to your profile |

|

|

|

.87 |

|

2. Posting videos to your profile |

|

|

|

.45 |

|

3. Posting stories to your profile |

|

|

|

.54 |

|

5. Commenting on other users’ photos |

.64 |

|

|

|

|

6. Commenting on other users’ videos |

.73 |

|

|

|

|

7. Commenting on other users’ stories |

.87 |

|

|

|

|

11. Liking other users’ stories |

.78 |

|

|

|

|

13. Sending direct messages to other users |

|

|

.54 |

|

|

14. Searching for other user’s accounts to see what they are up to |

|

|

|

|

|

15. Viewing photos (without commenting or liking) |

|

.81 |

|

|

|

16. Viewing videos (without commenting or liking) |

|

.64 |

|

|

|

17. Viewing stories (without commenting or liking) |

|

.56 |

|

|

|

19. Forwarding photos to other users (or tagging other users in photos) |

|

|

.86 |

|

|

20. Forwarding videos to other users (or tagging other users in videos) |

|

|

.89 |

|

|

21. Browsing the newsfeed passively (without liking or commenting on posts) |

|

.85 |

|

|

|

22. Browsing the newsfeed actively (liking or commenting on other users’ posts) |

.40 |

|

|

|

|

23. Browsing the explore page passively (without liking or commenting on posts) |

|

.54 |

|

|

|

24. Browsing the explore page actively (liking or commenting on other users’ posts) |

.41 |

|

|

|

|

25. Looking through friends’ posts |

|

|

|

|

|

26. Looking through a celebrity/influencer’s posts |

|

.41 |

|

|

|

Eigenvalue |

2.9 |

2.7 |

2.0 |

1.3 |

|

Variance |

16% |

15% |

11% |

7% |

|

Note. Factor loadings are only displayed if they are above 0.30. Eigenvalues and variances do not include removed items. |

||||

Internal Reliability and Correlation

The four factors demonstrated good internal reliability (Active reacting α = .85; Passive α = .81; Active direct social α = .87; Active creating α = .79). While the factors of the iPAUM were correlated, they remained conceptually distinct. Active reacting was strongly correlated with Active direct social (r = .60, p < .001) and Active creating (r = .66,

p < .001). Active direct social and Active creating were strongly correlated (r = .51, p < .001). This intercorrelation is consistent with theoretical expectations, as all three factors represent different types of active engagement but capture distinct interaction types: Active reacting involves minimal engagement, such as liking and reacting to posts, while Active direct social includes direct interpersonal communication through messages or tagging. Active creating, in contrast, involves content production such as posting images or videos. Passive use was moderately correlated with Active reacting (r = .43, p < .001), Active direct social (r = .38, p < .001), and Active creating (r = .27, p < .001). These moderate correlations suggest that while passive use may co-occur with active behaviours (e.g., liking), it remains functionally distinct from activities requiring explicit interaction or content creation.

Discriminant and Convergent Validity

Two subjective well-being measures were employed to establish discriminant validity. These correlations were used to demonstrate that the different scales do not measure the same concept. Even though there were some significant correlations, the iPAUM shows evidence of measuring distinct constructs from the other scales (see Table 3). A measure of Instagram intensity was employed to test convergent validity. The iPAUM showed good convergent validity as Instagram intensity and the iPAUM theoretically should be correlated.

Table 3. Correlations of the iPAUM Sub-Scales With Other Scales – Study 1.

|

|

Active reacting |

Active direct social |

Passive |

Active creating |

|

Satisfaction with Life Scale |

.08 |

.07 |

−.09 |

.13* |

|

Flourishing Scale |

.09 |

.13* |

−.03 |

.11 |

|

Instagram Intensity |

.55*** |

.55*** |

.41*** |

.54*** |

|

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. |

||||

Discussion

The aim of Study 1 was to create and validate a new multi-item measure which describes active and passive Instagram use. To do so, the PAUM for Facebook (Gerson et al., 2017) was adapted to reflect Instagram engagement. An EFA was conducted to investigate the latent factors of the new measure. This resulted in a new measure, the iPAUM, which consists of 18 items which load onto four factors: Active reacting, Active direct social, Active creating, and Passive (see Appendix A for a full list of items). The four factors showed good internal reliability, discriminant validity, and convergent validity.

Similar to the PAUM for Facebook, passive Instagram use reflects a type of engagement where Instagram users are both non-social and passive, i.e., not creating any content. Active reacting Instagram use reflects Instagram behaviour which is active in a reactive manner. In contrast, active direct social reflects direct communication with other Instagram users. Lastly, Active creating reflects Instagram use where a user is creating content for Instagram.

Study 2

Aim 1: Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

The first aim of Study 2 was to replicate the factor structure of the iPAUM found in Study 1. Data was collected using Prolific Academic to run a confirmatory factor analysis for this purpose.

Methods

Data

Respondents for the CFA were recruited through Prolific Academic over 12 days in August 2020. Respondents were only included in the sample if they were 18 or older and used Instagram. As in Study 1, two attention checks were included, and participants who failed both attention checks were excluded from the dataset. Furthermore, respondents were removed from the sample if they completed the questionnaire faster than half of the estimated time. The estimated completion time was based on the median time from Study 1. Thus, respondents in Study 2 who completed the questionnaire in less than 7 minutes were excluded, which resulted in the removal of 20 respondents. None of the respondents failed both attention checks. After the exclusion, the sample consisted of 297 respondents (131 males, 166 females, Mage = 29.6, SD = 9.8). Respondents accessed the study through the survey site Qualtrics, where they gave informed consent and completed the questionnaire. The questionnaire contained measures for several studies, including questions assessing Facebook behaviour and SNS use during the Covid-19 pandemic. Participants were paid £1.50 as compensation for their time (Median time = 14 minutes). The respondents were aged between 18 and 63, with most respondents reporting full-time employment (61% employed, 12% unemployed, 4% on furlough, 18% students, 1% retired, 2% long-term sick or disabled, and 2% other). Most respondents (58%) had obtained a university degree (69% had a bachelor’s degree, 27% had a master’s degree, and 3% had a doctoral degree). The sample size of 297 participants aligns with recommendations for confirmatory factor analysis, which suggest a minimum of

200–300 participants for models with 15–20 observed variables and multiple latent constructs (Kyriazos, 2018; Wolf et al., 2013).

Measures

Respondents from Study 2 completed the finalised 4-subscale version of the iPAUM, including the same two subjective well-being measures and the Instagram intensity measure. See Table 4 for descriptive statistics and internal reliability for all measures included in Study 2, Aim 1.

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics and Internal Reliability for Study 2, Aim 1 Measures.

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

α |

|

iPAUM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Active creating |

6.9 |

2.4 |

3.0 |

15.0 |

.74 |

|

Active reacting |

15 |

4.5 |

6.0 |

29.0 |

.83 |

|

Passive |

20.5 |

4.7 |

6.0 |

30.0 |

.79 |

|

Active direct social |

7.4 |

3.2 |

3.0 |

15.0 |

.88 |

|

Satisfaction with Life Scale |

21.7 |

6.7 |

5 |

35 |

.90 |

|

Flourishing Scale |

42.9 |

7.1 |

12 |

56 |

.89 |

|

Instagram Intensity |

2.9 |

0.8 |

0.0 |

4.6 |

.82 |

|

Note. N = 297, α = Cronbach’s alpha. |

|||||

Analytical Strategy

The data from Study 2 were analysed with maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using R statistical software (R Core Team, 2018) and the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012). The four factors of the iPAUM investigated in Study 1 were tested for normality. Active reacting and Passive were normally distributed, while Active direct social (Skewness = 5.0, Kurtosis = −5.9) and Active creating (Skewness = 5.2, Kurtosis = 4.4) were not. Due to the non-normality, Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square was applied to approximate chi-square for the CFA.

Results

The CFA was conducted using robust maximum likelihood estimation and the Satorra-Bentler correction. The model showed borderline acceptable fit: scaled χ²(129) = 311.96,

p < .001, robust RMSEA = .074, 90% CI [.064, .084], robust CFI = .909, and SRMR = .089. While the fit is borderline, the fit statistics show a very similar fit to the Facebook version of the PAUM scale (Gerson et al., 2017), which is widely used in Facebook research to measure engagement, and on which this scale was based. It is also worth noting that CFA typically works well for reflective factors, i.e., there is a latent trait that causes the behaviours that are captured by the items of the factor. Perhaps scales that measure social media use should rather be interpreted as formative factors, which could explain the borderline acceptable fit.

All items loaded significantly on their respective latent factors (p < .001), with standardised factor loadings ranging from .47 to .96. Although the SRMR slightly exceeded the conventional cut-off of .08, the overall pattern of fit indices, particularly the RMSEA and CFI, indicates that the model provides an adequate representation of the hypothesised four-factor structure. No extreme residual covariances were detected, although several pairs (e.g., item 16 and item 17 = .35; item 15 and item 18 = .30) showed localised dependence.

Internal Reliability and Correlations

Cronbach’s alphas showed good internal reliability for Study 2 measures (Table 4). The correlations for the factors of the iPAUM in Study 2 were similar to those found in Study 1. Active reacting was strongly correlated with Active direct social (r = .52, p < .001) and Active creating (r = .54, p < .001). Active direct social was strongly correlated with Active creating (r = .43, p < .001). Passive use was moderately correlated with Active reacting (r = .20, p < .001), and Active direct social (r = .29, p < .001). Passive use was not correlated with Active creating (r = .03, p > .05).

Discriminant and Convergent Validity

To test for discriminant validity, Pearson’s correlations with two subjective well-being measures were computed to verify that the sub-scales for passive and active Instagram use measured unique concepts (Table 5). The iPAUM showed good evidence of measuring distinct constructs. Furthermore, Instagram intensity was used to test convergent validity (Table 5). As also seen in Study 1, the iPAUM showed good convergent validity.

Table 5. Correlations of the iPAUM Sub-Scales With Other Scales – Study 2, Aim 1.

|

|

Active reacting |

Active direct social |

Active creating |

Passive |

|

Satisfaction with Life Scale |

.16* |

.00 |

.18** |

−.01 |

|

Flourishing Scale |

.18* |

−.04 |

.14* |

.02 |

|

Instagram Intensity |

.53*** |

.47*** |

.53*** |

.25*** |

|

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. |

||||

Discussion

The first aim of Study 2 was to conduct a CFA to confirm the structure of the factors of the iPAUM. The results of the CFA supported the structure of the factors found in Study 1, thus confirming the results. Again, the iPAUM factors showed good internal reliability and good discriminant validity against the two subjective well-being measures. Furthermore, the iPAUM showed good convergent validity against the Instagram intensity scale (see Appendix A for the final version of the iPAUM).

Aim 2: Testing Hypothesised Relationships for Self-Esteem

The second aim of Study 2 was to further investigate associations between the factors of the iPAUM and self-esteem to assess whether reported levels of self-esteem vary depending on the extent to which respondents engage with different Instagram features. Here, it was hypothesised that active Instagram use is associated with higher self-esteem, and passive Instagram use with lower self-esteem. The percentage of strangers followed on Instagram was also investigated to explore potential moderation effects in relation to these associations. Here, it was hypothesised that the percentage of strangers followed weakens the association between active Instagram use and self-esteem, while, in contrast, the percentage of strangers followed strengthens the association between passive Instagram use and self-esteem.

Methods

Data, Measures and Analytical Strategy

The analysis employed the same data described in Study 2, Aim 1. A multiple regression was run using the factors of the iPAUM as independent variables to explore whether levels of self-esteem were linked to different types of Instagram behaviour. As these Instagram behaviours are not mutually exclusive, users can have different variations of high and low scores for active and passive Instagram use. Self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1965). The Rosenberg self-esteem scale is one of the most widely used measures of self-esteem and routinely shows good internal reliability (Saiphoo et al., 2020; Tinakon & Nahathai, 2012). The scale consists of 10 items, assessing respondents’ general feelings about themselves. Respondents were asked how strongly they agreed or disagreed with ten statements, on a scale from (1) Strongly agree to (4) Strongly disagree. Further, the percentage of strangers followed was measured by asking participants to estimate the proportion of their followed accounts that were not personal acquaintances, including influencers and celebrities. This self-reported measure has been used in prior research to capture exposure to strangers’ content (Lup et al., 2015). The inclusion of this variable allows an exploration of its potential moderating effects on the relationship between Instagram use behaviours and self-esteem. A total of 297 participants were included in the regression models, which incorporated four iPAUM factors, interaction terms, and control variables. Although no a priori power analysis was conducted, the sample size meets the widely accepted heuristic of 10–20 cases per predictor (Green, 1991).

The multiple regression model further included socio-demographic control variables which previously had been investigated in relation to SNS use and self-esteem levels, including gender, age, income level, whether the respondents had obtained a university degree, employment status, and relationship status. The squared term of age was also included to check if the relationship between age and self-esteem might be curvilinear. Income status was assessed by asking respondents to report how comfortably they were living on their present income with four options ranging from Living comfortably on present income to Very difficult on present income. Descriptive statistics for the variables that were included in Study 2 (Aim 2), in addition to those already described in Table 4, are reported in Table 6.

Table 6. Descriptive Statistics and Internal Reliability for Study 2, Aim 2, Additional Measures.

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

α |

|

Self-esteem |

22.4 |

5.6 |

10 |

40 |

.90 |

|

Percentage of strangers followed |

48.0 |

29.5 |

0.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Socio-demographics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age |

29.6 |

9.8 |

18.0 |

63.0 |

|

|

Age2 |

974.0 |

711.9 |

324.0 |

3,969.0 |

|

|

Income status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Living comfortably on present income |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Coping on present income |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Difficult on present income |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Very difficult on present income |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

University degree |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Has university degree |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Relationship status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

In relationship/married |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Single |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Other |

0.02 |

0.1 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Employment status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Full-time employed |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Self-employed |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Part-time employed |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Unemployed |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Full-time student |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Long term sick or disabled |

0.02 |

0.1 |

0 |

1.0 |

|

|

On furlough |

0.04 |

0.2 |

0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Retired |

0.01 |

0.1 |

0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Other |

0.02 |

0.1 |

0 |

1.0 |

|

|

Note. α = Cronbach’s alpha. University degree was binary coded with 0 denoting that the respondent does not hold a university degree or higher. Descriptive statistics for the iPAUM scales can be found in Table 4. N = 297. |

|||||

Results

The results (Table 7) showed a significant association between active direct social use and self-esteem in two of the three model specifications; a positive association in Model 1, which did not include additional predictors (Model 1: b = 0.26, p < .05) and a negative association in Model 3, which included control variables (Model 3: b = −0.61, p < .05). The percentage of strangers followed significantly moderated this association (Models 2 and 3); the coefficient of the interaction between the percentage of strangers followed and active direct social use was positive (Models 2 and 3; b = 0.01, p < .01).

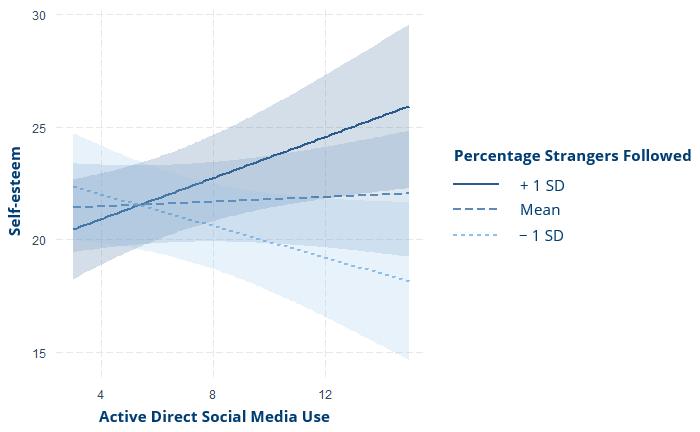

Using simple slopes analysis and Johnson-Neyman intervals (Figure 1), the moderation was tested at three levels of percentage of strangers followed: one standard deviation below the mean, the mean, and one standard deviation above the mean. The negative association between active direct social and self-esteem is significant when the percentage of strangers is below 15%. When more than 67% of the accounts that users follow belong to strangers, the association between active direct social and self-esteem is positive. This means that when users mostly follow accounts of strangers, active direct social use is significantly related to higher levels of self-esteem.

Figure 1. Simple Slopes Analysis and Johnson-Neyman Intervals.

Note. Interaction effect of active direct social media use and percentage of strangers followed on self-esteem. The solid line represents self-esteem at one standard deviation above the mean of percentage of strangers followed (+1 SD), the dashed line represents self-esteem at the mean, and the dotted line represents self-esteem at one standard deviation below the mean (−1 SD). Shaded regions indicate 95% confidence intervals for each level of the moderator. Self-esteem is plotted as a function of active direct social media use. For interpretation, the line intersections mark thresholds: below approximately 15% strangers followed (−1 SD) the slope is negative, above approximately 67%

(+1 SD) it is positive, and between these values it is close to zero.

The results showed no significant associations across all models between active creating use and self-esteem levels (Model 3: b = −0.01, p > .05), active reacting use and levels of self-esteem (Model 3: b = 0.05, p > .05), and passive use and self-esteem levels (Model 3: b = 0.09, p > .05). The percentage of strangers that a user follows only moderated the relationship between active direct social use and self-esteem levels. For a full overview of all models, see Table 7.

Table 7. Multiple Ordinary Least Squares Regression for Self-Esteem and the iPAUM Factors.

|

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||||||||||||||

|

Predictors |

b |

SE |

β |

Std. SE |

CI |

p |

b |

SE |

β |

Std. SE |

CI |

p |

b |

SE |

β |

Std. SE |

CI |

p |

|

Intercept |

22.55 |

1.76 |

−.00 |

0.06 |

[19.09, 26.00] |

<.001 |

20.42 |

3.08 |

.03 |

0.06 |

[14.36, 26.49] |

<.001 |

27.98 |

5.40 |

−.19 |

0.16 |

[17.36, |