What’s the optimal usage pattern? Latent profile analysis of Chinese young adults’ social networking site use and its association with subjective well-being

Vol.20,No.1(2026)

Contributing to the active debate about how the use of social networking site (SNS) affects mental health, this study uses a person-centered approach to examine the relationship between SNS use and components of subjective well-being. Unlike previous research that primarily employed variable-centered approaches and focused on the active-passive use dichotomy, this study considered a range of SNS activities across different communication contexts (private vs. public) and audiences (e.g., friends vs. strangers) to identify distinct user profiles. A latent profile analysis among Chinese young adults (N = 1,075, Mage = 20.43) revealed five latent profiles: Minimal users (9.1%), Moderate users (22.2%), High explorers (19%), Private communicators (36.5%), and Advanced engagers (13.2%). These profiles were significantly associated with well-being. Advanced engagers reported the highest life satisfaction and positive affect, along with low negative affect. In contrast, Private communicators showed lowest life satisfaction and relatively low positive affect, though they also experienced less negative affect. Moderate users and High explorers experienced more negative affect, whereas Minimal users reported the lowest positive affect. These findings reveal heterogeneous user styles among Chinese SNS users and further suggest that active use may contribute to well-being, but only when it combines both public and private communication within existing social networks.

SNS use, subjective well-being, heterogeneity, person-centered, latent profile analysis

Xue-Qin Yin

School of Literature and Journalism, Chongqing Technology and Business University, Chongqing, China

Xue-Qin Yin is a lecture in the School of Literature and Journalism, Chongqing Technology and Business University, China. Her research interests include social media use, AI use, and their impacts on users' social and psychological well-being.

Jin-Liang Wang

Center for Mental Health Education, Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

Jin-Liang Wang is a professor in the Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University, China. His research investigates the antecedents of online communication and its influence on users’ social and psychological development.

Xiang Niu

Center for Mental Health Education, Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

Xiang Niu is a doctoral student in the Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University, China. Her research interests include social media use effects, well-being and individual’s mental health.

Sebastian Scherr

Center for Interdisciplinary Health Research, Department of Media, Knowledge, and Communication, University of Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany

Sebastian Scherr is a professor at the Center for Interdisciplinary Health Research and the Department of Media, Knowledge, and Communication at the University of Augsburg, Germany. His research interests focus on health communication, political communication, and suicide prevention.

James Gaskin

Department of Information System, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA

James Gaskin is an Associate Professor in the Department of Information System, Brigham Young University, Utah, USA. His research interests include human computer interaction, (particularly augmented reality and wearables), and human robot interaction.

Dean McDonnell

Department of Humanities, South East Technological University, Carlow, Ireland

Dean McDonnell is a lecturer at South East Technological University in Carlow, Ireland. His research interests include pedagogy, teaching and learning, as well as online psychology and behavior.

Ahn, D., & Shin, D.-H. (2013). Is the social use of media for seeking connectedness or for avoiding social isolation? Mechanisms underlying media use and subjective well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 2453–2462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.022

Akaike, H. (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52(3), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294359

Akbari, M., Bahadori, M. H., Khanbabaei, S., Milan, B. B., Jamshidi, S., & Potenza, M. N. (2023). Potential risk and protective factors related to problematic social media use among adolescents in Iran: A latent profile analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 146, Article 107802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107802

Allcott, H., Braghieri, L., Eichmeyer, S., & Gentzkow, M. (2020). The welfare effects of social media. American Economic Review, 110(3), 629–676. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20190658

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2021). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary second model. Mplus Web Notes, 21, 1–80. https://www.statmodel.com/examples/webnotes/webnote21.pdf

Berlin, K. S., Williams, N. A., & Parra, G. R. (2014). An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39(2), 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jst084

Beyens, I., Pouwels, J. L., van Driel, I. I., Keijsers, L., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2021). Social media use and adolescents’ well-being: Developing a typology of person-specific effect patterns. Communication Research, 51(6), 691–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502211038196

Boer, M., Stevens, G. W. J. M., Finkenauer, C., & van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M. (2022). The course of problematic social media use in young adolescents: A latent class growth analysis. Child Development, 93(2), e168–e187. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13712

Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

Brailovskaia, J., Delveaux, J., John, J., Wicker, V., Noveski, A., Kim, S., Schillack, H., & Margraf, J. (2023). Finding the “sweet spot” of smartphone use: Reduction or abstinence to increase well-being and healthy lifestyle?! An experimental intervention study. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 29(1), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000430

Brandtzæg, P. B. (2012). Social networking sites: Their users and social implications - a longitudinal study. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17(4), 467–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01580.x

Burke, M., & Kraut, R. E. (2016). The relationship between Facebook use and well-being depends on communication type and tie strength. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 21(4), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12162

Burke, M., Marlow, C., & Lento, T. (2010). Social network activity and social well-being. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’10) (pp. 1909–1912). Association for Computer Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753613

Burnell, K., George, M. J., Vollet, J. W., Ehrenreich, S. E., & Underwood, M. K. (2019). Passive social networking site use and well-being: The mediating roles of social comparison and the fear of missing out. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 13(3), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.5817/cp2019-3-5

Cerniglia, L., Griffiths, M. D., Cimino, S., De Palo, V., Monacis, L., Sinatra, M., & Tambelli, R. (2019). A latent profile approach for the study of internet gaming disorder, social media addiction, and psychopathology in a normative sample of adolescents. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 12, 651–659. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S211873

Chen, H.-T., & Li, X. (2017). The contribution of mobile social media to social capital and psychological well-being: Examining the role of communicative use, friending and self-disclosure. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 958–965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.011

Chen, W., & Lee, K.-H. (2013). Sharing, liking, commenting, and distressed? The pathway between Facebook interaction and psychological distress. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(10), 728–734. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0272

Chen, W., Fan, C.-Y., Liu, Q.-X., Zhou, Z.-K., & Xie, X.-C. (2016). Passive social network site use and subjective well-being: A moderated mediation model. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 507–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.038

Chen, Y. A., Fan, T., Toma, C. L., & Scherr, S. (2022). International students’ psychosocial well-being and social media use at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent profile analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 137, Article 107409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107409

Cho, H., Cannon, J., Lopez, R., & Li, W. (2024). Social media literacy: A conceptual framework. New Media & Society, 26(2), 941–960. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211068530

Chou, H.-T. G., & Edge, N. (2012). “They are happier and having better lives than I am”: The impact of using Facebook on perceptions of others’ lives. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(2), 117–121. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0324

Clark, J. L., Algoe, S. B., & Green, M. C. (2018). Social network sites and well-being: The role of social connection. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(1), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417730833

Clark, S. L. (2010). Mixture modeling with behavioral data. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 71(4-A), 1183. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2010-99190-216

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Dienlin, T., Masur, P. K., & Trepte, S. (2017). Reinforcement or displacement? The reciprocity of FtF, IM, and SNS communication and their effects on loneliness and life satisfaction. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 22(2), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12183

Dixon, S. (2022a). Daily time spent on social networking by internet users worldwide from 2012 to 2022. Statista. https://web.archive.org/web/20230204103800/https://www.statista.com/statistics/433871/daily-social-media-usage-worldwide/

Dixon, S. (2022b). Most popular social networks worldwide as of January 2022, ranked by number of monthly active users. https://web.archive.org/web/20230105070824/https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

Domahidi, E. (2018). The associations between online media use and users’ perceived social resources: A meta-analysis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(4), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy007

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

Fioravanti, G., Prostamo, A., & Casale, S. (2020). Taking a short break from Instagram: The effects on subjective well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(2), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0400

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2016). “Harder, better, faster, stronger”: Negative comparison on Facebook and adolescents’ life satisfaction are reciprocally related. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(3), 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0296

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2020). Toward an integrated and differential approach to the relationships between loneliness, different types of Facebook use and adolescents’ depressed mood. Communication Research, 47(5), 701–728. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215617506

Hao, Z., & Long, L. (2004). Statistical remedies for common method biases. Advances in Psychological Science, 12(6), 942–950. https://journal.psych.ac.cn/adps/EN/Y2004/V12/I06/942

Howard, M., & Hoffman, M. E. (2018). Variable-centered, person-centered, and person-specific approaches: Where theory meets the method. Organizational Research Methods, 21(4), 846–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117744021

Hunt, M., All, K., Burns, B., & Li, K. (2021). Too much of a good thing: Who we follow, what we do, and how much time we spend on social media affects well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 40(1), 46–68. https://doi.org/10.1521/JSCP.2021.40.1.46

Keum, B. T. H., Wang, Y.-W., Callaway, J., Abebe, I., Cruz, T., & O’Connor, S. (2023). Benefits and harms of social media use: A latent profile analysis of emerging adults. Current Psychology, 42(27), 23506–23518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03473-5

Kim, Y., Sohn, D., & Choi, S. M. (2011). Cultural difference in motivations for using social network sites: A comparative study of American and Korean college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(1), 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.08.015

Kraut, R., Patterson, M., Lundmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukophadhyay, T., & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist, 53(9), 1017–1031. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.53.9.1017

Kross, E., Verduyn, P., Sheppes, G., Costello, C. K., Jonides, J., & Ybarra, O. (2021). Social media and well-being: Pitfalls, progress, and next steps. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.10.005

Lambert, J., Barnstable, G., Minter, E., Cooper, J., & McEwan, D. (2022). Taking a one-week break from social media improves well-being, depression, and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 25(5), 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2021.0324

LaRose, R., Connolly, R., Lee, H., Li, K., & Hales, K. D. (2014). Connection overload? A cross cultural study of the consequences of social media connection. Information Systems Management, 31(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2014.854097

Lin, J.-H. T. (2019). Strategic social grooming: Emergent social grooming styles on Facebook, social capital and well-being. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 24(3), 90–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmz002

Lin, J.-H. T., & Hsieh, Y.-S. (2021). Longitudinal social grooming transition patterns on Facebook, social capital, and well-being. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 26(6), 320–342. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmab011

Lo, Y., Mendell, N. R., & Rubin, D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/88.3.767

Lup, K., Trub, L., & Rosenthal, L. (2015). Instagram #Instasad?: Exploring associations among Instagram use, depressive symptoms, negative social comparison, and strangers followed. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(5), 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0560

Ma, C. M. S. (2018). A latent profile analysis of Internet use and its association with psychological well-being outcomes among Hong Kong Chinese early adolescents. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 13(3), 727–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9555-2

Marino, C., Gini, G., Vieno, A., & Spada, M. M. (2018). A comprehensive meta-analysis on problematic Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior, 83, 262–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.009

Matthes, J., Karsay, K., Hirsch, M., Stevic, A., & Schmuck, D. (2022). Reflective smartphone disengagement: Conceptualization, measurement, and validation. Computers in Human Behavior, 128, Article 107078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107078

Meier, A., & Krause, H.-V. (2023). Does passive social media use harm well-being? An adversarial review. Journal of Media Psychology Theories Methods and Applications, 35(3), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000358

Mertler, C. A., & Vannatta, R. A. (2016). Advanced and multivariate statistical methods: Practical application and interpretation (6th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315266978

Metzger, M. J., Wilson, C., & Zhao, B. Y. (2018). Benefits of browsing? The prevalence, nature, and effects of profile consumption behavior in social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(2), 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmx004

Montag, C., Demetrovics, Z., Elhai, J. D., Grant, D., Koning, I., Rumpf, H.-J., Spada, M. M., Throuvala, M., & van den Eijnden, R. (2024). Problematic social media use in childhood and adolescence. Addictive Behaviors, 153, Article 107980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2024.107980

Moreau, A., Laconi, S., Delfour, M., & Chabrol, H. (2015). Psychopathological profiles of adolescent and young adult problematic Facebook users. Computers in Human Behavior, 44, 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.045

Muthen, B., & Kaplan, D. (1985). A comparison of some methodologies for the factor analysis of non-normal Likert variables. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 38(2), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1985.tb00832.x

Nguyen, M. H., Büchi, M., & Geber, S. (2024). Everyday disconnection experiences: Exploring people’s understanding of digital well-being and management of digital media use. New Media & Society, 26(6), 3657–3678. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221105428

Niu, X., Verduyn, P., Gaskin, J., Scherr, S., McDonnell, D., & Wang, J.-L. (2025). The development and validation of the extended active-passive social media use scale. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 19(3), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2025-3-1

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

Orben, A., & Blakemore, S.-J. (2023). How social media affects teen mental health: A missing link. Nature, 614(7948), 410–412. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00402-9

Pang, H. (2021). Unraveling the influence of passive and active WeChat interactions on upward social comparison and negative psychological consequences among university students. Telematics and Informatics, 57, Article 101510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101510

Parry, D. A., Fisher, J. T., Mieczkowski, H., Sewall, C. J. R., & Davidson, B. I. (2022). Social media and well-being: A methodological perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, Article 101285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.11.005

Przybylski, A. K., & Weinstein, N. (2017). A large-scale test of the goldilocks hypothesis: Quantifying the relations between digital-screen use and the mental well-being of adolescents. Psychological Science, 28(2), 204–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616678438

Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136

Sclove, S. L. (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52(3), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294360

Scott, C. F., Bay-Cheng, L. Y., Prince, M. A., Nochajski, T. H., & Collins, R. L. (2017). Time spent online: Latent profile analyses of emerging adults’ social media use. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.026

Scherr, S. (2018). Traditional media use and depression in the general population: evidence for a non-linear relationship. Current Psychology, 40(2), 1046–1310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0020-7

Shaw, A. M., Timpano, K. R., Tran, T. B., & Joormann, J. (2015). Correlates of Facebook usage patterns: The relationship between passive Facebook use, social anxiety symptoms, and brooding. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 575–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.003

Thorisdottir, I. E., Sigurvinsdottir, R., Asgeirsdottir, B. B., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2019). Active and passive social media use and symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood among Icelandic adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(8), 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0079

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2007). Online communication and adolescent well-being: Testing the stimulation versus the displacement hypothesis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1169–1182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00368.x

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2013). The differential susceptibility to media effects model. Journal of Communication, 63(2), 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12024

Valkenburg, P. M., Beyens, I., Pouwels, J. L., van Driel, I. I., & Keijsers, L. (2022). Social media browsing and adolescent well-being: Challenging the “passive social media use hypothesis.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 27(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmab015

Valkenburg, P. M., van Driel, I. I., & Beyens, I. (2022). The associations of active and passive social media use with well-being: A critical scoping review. New Media & Society, 24(2), 530–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211065425

Verduyn, P., Gugushvili, N., & Kross, E. (2022). Do social networking sites influence well-being? The extended active-passive model. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 31(1), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211053637

Verduyn, P., Lee, D. S., Park, J., Shablack, H., Orvell, A., Bayer, J., Ybarra, O., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2015). Passive Facebook usage undermines affective well-being: Experimental and longitudinal evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(2), 480–488. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000057

Wang, J.-L., Gaskin, J., Rost, D. H., & Gentile, D. A. (2018). The reciprocal relationship between passive social networking site (SNS) usage and users’ subjective well-being. Social Science Computer Review, 36(5), 511–522. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317721981

Wang, J.-L., Jackson, L. A., Gaskin, J., & Wang, H.-Z. (2014). The effects of social networking site (SNS) use on college students’ friendship and well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 37, 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.051

Wang, J.-L., Jackson, L. A., Wang, H.-Z., & Gaskin, J. (2015). Predicting social networking site (SNS) use: Personality, attitudes, motivation and internet self-efficacy. Personality and Individual Differences, 80, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.016

Warren, C. M., Kechter, A., Christodoulou, G., Cappelli, C., & Pentz, M. A. (2020). Psychosocial factors and multiple health risk behaviors among early adolescents: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 43(6), 1002–1013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-020-00154-1

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Wenninger, H., Krasnova, H., & Buxmann, P. (2019). Understanding the role of social networking sites in the subjective well-being of users: A diary study. European Journal of Information Systems, 28(2), 126–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2018.1496883

Yang, C.-C. (2016). Instagram use, loneliness, and social comparison orientation: Interact and browse on social media, but don’t compare. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(12), 703–708. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0201

Yin, X.-Q., Zhang, X.-X., Scherr, S., & Wang, J.-L. (2022). Browsing makes you feel less bad: An ecological momentary assessment of passive Qzone use and young women’s negative emotions. Psychiatry Research, 309, Article 114373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114373

Yue, Z., Zhang, R., & Xiao, J. (2022). Passive social media use and psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of social comparison and emotion regulation. Computers in Human Behavior, 127, Article 107050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107050

Zheng, D., Ni, X.-L., & Luo, Y.-J. (2019). Selfie posting on social networking sites and female adolescents’ self-objectification: The moderating role of imaginary audience ideation. Sex Roles, 80(5–6), 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0937-1

Zywica, J., & Danowski, J. (2008). The faces of Facebookers: Investigating social enhancement and social compensation hypotheses; predicting Facebook and offline popularity from sociability and self-esteem, and mapping the meanings of popularity with semantic networks. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.01429.x

Authors’ Contribution

Xue-Qin Yin: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. Jin-Liang Wang: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. Xiang Niu: investigation, writing—review & editing. Sebastian Scherr: writing—review & editing. James Gaskin: writing—review & editing. Dean P McDonnell: writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

August 24, 2024

Revision received:

July 27, 2025

Accepted for publication:

November 1, 2025

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

The potential impact of social networking site (SNS) on users’ subjective well-being has been, and continues to be, an actively debated topic for over a decade (Orben & Blakemore, 2023), as userbase continues to grow. According to a recent survey, there are over 5 billion social media users worldwide in 2024 (Dixon, 2022b), who spend an average of 147 minutes each day on SNS to share and consume information (Dixon, 2022a). Recently, a significant research advancement on this topic has been the conceptualization and related hypotheses of SNS use (Kross et al., 2021). Specifically, studies have distinguished SNS use into active and passive categories (Burke et al., 2010), and further concluded that passive SNS use (i.e., browsing and consuming information without direct communication) is detrimental to well-being while active SNS use (i.e., using SNS to facilitate direct communication with others) is beneficial for well-being (see review of Valkenburg, van Driel, et al., 2022). To date, numerous studies have given supports to these active and passive use hypotheses (Verduyn et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018). For instance, by using both longitudinal and experimental designs, Verduyn et al. (2015) have demonstrated that passive Facebook use would undermine users’ affective well-being.

Despite much progress made by prior research, the relationship between SNSs use and subjective well-being—including cognitive (i.e., life satisfaction) and affective well-being (i.e., positive and negative affect)—is still ambiguous. An increasing number of studies do not support the active and passive hypotheses (Valkenburg, van Driel, et al., 2022; Yin et al., 2022), and some researchers have suggested that these hypotheses were only confirmed in a small subset of the population (Beyens et al., 2021). For instance, Valkenburg, Beyens, et al. (2022) revealed that only 20% adolescent users felt worse after passive SNSs use, whereas 17% felt better.

A possible reason for the mixed findings is the failure to account for individual heterogeneity both theoretically and methodologically. Theoretically, previous studies have often assumed that a set of specific behaviors are largely shared or universal and then aggregated their scores to create a high-level construct (i.e., active or passive use; Burke et al., 2010). However, this approach may overlook nuanced differences between specific SNS behaviors (Meier & Krause, 2023), thereby leading to confounding outcomes. For example, although both private messaging and status updating are categorized as active use, they actually represent different communication contexts (i.e., private vs. public communication; Valkenburg, van Driel, et al., 2022). Specifically, private messaging typically entails a one-to-one means of communication through which users can synchronously interact with their friends with personalized messages. In contrast, status updating serves as a one-to-many communication through which messages are asynchronously broadcast to a large group of audience. Empirical evidence suggests that private messaging is associated with improvements in well-being while broadcasting is not (Burke & Kraut, 2016). In this case, it is crucial to extend the active-passive dichotomy to examine specific SNS activities and their relationships to well-being (J. L. Clark et al., 2018).

Methodologically, previous studies have primarily employed a variable-centered approach to examine the frequency of active and passive use and its relationship with well-being (Burke & Kraut, 2016; Verduyn et al., 2015). However, this approach often treats SNS users as a homogeneous sample, assuming consistent behaviors among individuals, which hinders the identification of the heterogeneity in SNS use. In reality, users’ behaviors on SNS are likely to manifest as complex combinations of various activities, such as status updates, comments, private messages, and news feed browsing. These combinations may, in turn, lead to a unique user experience and distinct impacts on well-being. Latent profile analysis (LPA), as a typical person-centered statistical approach, can help identify whether different combinations of SNS behaviors exist and how these latent profiles of SNS behaviors may be differentially related to well-being. Recently, an increasing number of studies have applied LPA techniques to identify heterogeneous subgroups of SNS users (e.g., Keum et al., 2023; Lin, 2019). For example, Scott et al. (2017) identified three subgroups (high, medium, and low) among American emerging adults based on SNS use frequency and engagement levels. However, to our knowledge, these studies aiming to capture the heterogeneity of SNS use are predominantly based on measures of general use (e.g., usage frequency; Scott et al., 2017; problematic use; Akbari et al., 2023; Boer et al., 2022; Cerniglia et al., 2019) , or the purpose of use (Keum et al., 2023), rather than through the lens of the specific SNS activities to identify subgroups. As a result, it remains unclear whether and to what extent the SNS users are heterogeneous in terms of their various specific active and passive usage behaviors, let alone how these different subgroups are related to well-being.

Overall, the objective of this study is to utilize the LPA method to investigate the potential subgroups of SNS users from the lens of specific SNS activities. Given that certain behaviors (e.g., chatting) occur more frequently than others (e.g., status updating; Frison & Eggermont, 2020), we hypothesize the existence of distinct subgroups characterized by varying levels of usage and specific behavior combinations. Subsequently, we aim to examine how these identified subgroups of SNS users would be associated with subjective well-being, which is defined as high levels of positive affect, low levels of negative affect, and a sense of life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1985). By doing so, our study not only offers valuable insights into the conflicting findings resulting from the active-passive dichotomy, but also contributes to a better understanding of what constitutes healthy usage of social networking site and how to educate individuals on their proper use. This study uses a sample of Chinese young adults to enrich the studied populations, as previous LPA studies related to SNS use are primarily conducted in Western countries. To our knowledge, this study also represents one of the first attempts at applying a person-centered approach to understand the relationship between SNS use and subjective well-being in Chinese context.

Literature Review

The Problematic Measurement of Users’ Behaviors on SNS

Social networking sites are web-based services that enable users to generate and maintain social networks through various online activities, such as chatting, posting status updates, and browsing others’ information (Boyd & Ellison, 2007). SNS use was originally operationalized and measured as the overall time spent on a certain SNS for a week or each day, or the intensity of that use (e.g., Ellison et al., 2007). Later, this aggregate use approach was refined to distinguish between passive and active behaviors, reflecting how, rather than how much, SNS are used (Burke et al., 2010). Specifically, active use refers to activities that promote interaction with others, including sending direct messages, commenting, sharing links, and posting status; whereas passive use refers to browsing or consuming content on SNS without interacting with other users, such as browsing others’ profiles, posts, news, or comments (Verduyn et al., 2015). As a common approach to conceptualizing and measuring SNS use, the active-passive use dichotomy has been a big step toward a better understanding of usage behaviors on SNS.

However, recent studies have suggested that this dichotomy oversimplifies a variety of SNS activities into a high-level aggregated construct, thereby limiting our understanding of how people use SNS or whether SNS use is associated with well-being (Parry et al., 2022). Supporting this concern, a recent scoping review revealed considerable heterogeneity in the relationship between active/passive use and well-being across 40 survey-based studies (Valkenburg , van Driel, et al., 2022). This evidence suggests that the active versus passive use dichotomy may still be too coarse to uncover meaningful associations with well-being (Valkenburg, van Driel, et al., 2022).

More specifically, SNS platforms afford a variety of activities including, but not limited to chatting, broadcasting, commenting, and browsing (Kross et al., 2021). These activities differ not only in their communication features but also in their intended audience (Verduyn et al., 2022). For example, active use may occur in either public contexts (e.g., broadcasting via status updating) or private settings (e.g., private messaging), and can be directed toward a specific person or a broader audience (Verduyn et al., 2022). According to the norm of reciprocity, private active use, such as private messaging, typically entails intimate one-to-one interactions that may elicit a strong social obligation to respond. In contrast, public broadcasting (e.g., status updating) involves one-to-many communication, where responses are less expected and often more superficial (Wenninger et al., 2019). Accordingly, empirical studies have found that targeted active use is associated with greater well-being than non-targeted use (Burke & Kraut, 2016).

Similarly, passive use can be further differentiated by the source of content consumed, that is, browsing content from friends or strangers. According to social comparison theory, browsing content from unfamiliar others may increase the likelihood of social comparison, which would in turn trigger feelings of inferiority and negative impacts on well-being (Frison & Eggermont, 2020; Verduyn et al., 2015). In contrast, users tend to interpret friends' content more accurately, which may reduce the likelihood of social comparison (Chou & Edge, 2012). Empirical evidence has shown that following more friends is associated with fewer negative emotions, whereas following more strangers is linked to higher levels of depression (Hunt et al., 2021).

Given these complexities, researchers have called for more nuanced frameworks to refine the active-passive use dichotomy. For instance, Verduyn et al. (2022) proposed an extended active-passive model, in which active use is further decomposed along the dimensions of warm/cold behavior and targeted/non-targeted use, and passive use is decomposed along the dimensions of success/failure stories and low/high self-relevance. Building on this extended framework, the present study adopted a refined framework that distinguishes SNS activities based on communication context (private vs. public) and audience type (friends vs. strangers). By investigating specific SNS activities such as chatting, commenting, broadcasting, and browsing, this study aims to clarify how users interact socially on SNS and how their usage patterns relate to users' subjective well-being.

Approaches to Identify Heterogeneity of SNS Use

Another issue that may be related to conflicting findings in the literature is that different people engage in distinct specific usage behaviors, and these diverse patterns of SNS use may have varying impacts on subjective well-being (Verduyn et al., 2022). According to media use theories, such as the differential susceptibility to media effect model, SNS use is not uniform across individuals, but is influenced by personal preferences, motivations and susceptibilities (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013). And hence, users’ behaviors on SNS may vary across the population. However, previous empirical studies have primarily adopted a variable-centered approach to investigate the average effect of SNS use across an entire sample. This approach implicitly treats all SNS users as a homogeneous group, without considering the possibility that users may cluster into different subgroups characterized by unique usage styles (Howard & Hoffman, 2018; Parry et al., 2022).

Recently, several studies have shifted toward a person-centered approach, which aims to identify user subgroups with similar behavioral patterns (e.g., Ma, 2018; Moreau et al., 2015; Scott et al., 2017). For instance, studies have identified three subgroups of based on SNS use frequency and engagement (e.g., high, medium, and low use; Scott et al., 2017). Other studies have gone further by focusing on more specific behavioral dimensions (e.g., Lin, 2019; Ma, 2018). For example, Brandtzæg (2012) categorized Norwegian SNS users into five subgroups: sporadics, lurkers, socializers, debaters, and advanced users, based on their participation in social and non-social activities. Similarly, Lin (2019) identified five distinct subgroups (i.e., social butterflies, image managers, trend followers, relationship maintainers and lurkers) based on users' social grooming behaviors on Facebook (i.e., the way users choose to discuss and interact with others). Extending this work, Lin and Hsieh (2021) used a three-year panel study and latent transition analysis to examine the stability of these user styles. They found that most individuals maintained a stable user style over time; active users tended to remain active, while inactive users largely stayed inactive (Lin & Hsieh, 2021). Although these findings have advanced our understandings of user heterogeneity, most of them either focused on general SNS use or classified users based on a single behavioral dimension, without considering the implicit differences amongst various behaviors or the co-occurrence of different types of behaviors, such as private versus public communication.

Building on this literature, this study aims to identify distinct user profiles based on specific SNS activities, including both private and public communication, as well as content consumptions from both friends and strangers. We propose that SNS users may engage in diverse combinations of these activities with different intensity. For instance, some users may frequently post updates and send messages to others while simultaneously passively browsing other’ content (i.e., high private and public communication combined with high content consumption). Conversely, others may primarily prefer private messages with minimal public activities or content consumptions (i.e., high private communication only). Still others may prefer to browse content exclusively from friends rather than strangers or distant contacts. Given the absence of empirical evidence for latent user subgroups based on these active and passive use activities, we propose the following research question:

RQ1: What SNS use profiles can be identified based on specific SNS activities and their use intensity?

Theoretical Models on SNS Use and Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being refers to individuals' affective reactions and cognitive evaluations of their lives (Diener et al., 1985), including positive aspects such as positive affect and life satisfaction, as well as negative aspects such as anxiety, loneliness and stress. This study focuses on how SNS use affect one's affect and life satisfaction, and we thus employed a composite measure of various indicators including satisfaction with one's life, positive affect, and negative affect. Life satisfaction reflects an individual’s overall evaluation of their quality of life and contentment with their existence (Diener et al., 1985), which is a stable, long-term cognitive indicator of well-being Positive and negative affect reflect the situational states of enthusiastic or unpleasant (Watson et al., 1988). These three indicators have been widely used in prior studies examining the relationship between SNS use and well-being (Dienlin et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). Though our goal is not to directly compare these components of well-being, using multiple indicators allows us to explore how SNS use subgroups differ in a broad aspect of well-being. In the following, we compare models in explaining the association between SNS use and well-being, and then put forward our research question.

The Displacement Versus Augmentation Hypotheses. The displacement hypothesis is among the first models elucidating the impacts of Internet use on well-being. It suggests that Internet use, including SNS use, can reduce the quality of existing real-world relationships, particularly friendships, and thereby reduce the user’s well-being (Kraut et al., 1998). Contrary to the displacement hypothesis, the augmentation hypothesis suggests that using media that promotes online friendships can also facilitate real-world friendship quality and consequently increase the users’ well-being (Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). Both hypotheses have been empirically supported to some extent. For example, regarding the displacement hypothesis, there are some recent studies among young adults suggesting that digital media use may be at the expense of face-to-face contact with close friends (e.g., Facebook use, Allcott et al., 2020). However, there are also findings in line with the augmentation hypothesis (Dienlin et al., 2017; Domahidi, 2018). For instance, using two-wave longitudinal data, Dienlin et al. (2017) found that SNS communication increased users’ life satisfaction over time.

The seeming conflicts between the displacement and augmentation hypotheses vanish when subtypes for using SNS are considered. For example, Ahn and Shin (2013) suggested that when SNS is used for seeking connectedness, media can strengthen face-to-face communication. However, when it is used for avoiding social isolation, media may displace face-to-face communication. In the same vein, another study provided more direct evidence by showing that “social” type SNS use was positively related to users’ well-being, whereas “entertainment” type SNS use was not (Wang et al., 2014).

Active Versus Passive Usage Hypotheses. With the aim of more clearly defining SNS use, the active and passive SNS use hypotheses have been proposed, which suggest that active use leads to positive effects on well-being as it elicits social support and positive feedback, while passive SNS use leads to declined well-being as it induces upward social comparison and envy (W. Chen et al., 2016; Frison & Eggermont, 2020; Wang et al., 2018). For example, numerous studies demonstrated that when users spend more time on passively consumption of others' content, they tend to report more negative emotions (Burke et al., 2010; Lup et al., 2015) and lower life satisfaction (Frison & Eggermont, 2016), in line with the displacement hypothesis. In contrast, when individuals use SNS for the sake of building social connections actively, they reported high levels of social capital (Burke et al., 2010), and high well-being (H. T. Chen & Li, 2017), which is consistent with the augmentation hypothesis.

However, the active vs. passive SNS use model remains unsatisfactory as recent emerging evidence suggests that aggregating across specific SNS use behaviors, and classifying them as active or passive, may therefore yield ambiguous results. For instance, while several studies have revealed negative effects of passive SNS use on well-being (Burnell et al., 2019; Thorisdottir et al., 2019; Yue et al., 2022), a number of studies have found nonsignificant (e.g., Wenninger et al., 2019) or even positive (e.g., Yang, 2016) effects. The same holds for active use, as multiple studies have found nonsignificant (e.g., Pang, 2021) or even negative (e.g., Zheng et al., 2019) effects. It is thus necessary to extend active and passive use model to better understand the relationship between SNS use and well-being.

Problematic SNS Use Models. Problematic SNS use is characterized by addiction-like behaviors and/or deficits in self-regulation, such as loss of control over SNS use, and continued usage despite negative consequences in daily life. Meta-analytic evidence has found that Facebook users with such symptoms tend to report lower levels of well-being (Marino et al., 2018). Consistent with these findings, a recent longitudinal study indicated that adolescents with high levels of problematic use experienced lower life satisfaction compared to those with low levels of problematic use (Boer et al., 2022). Although problematic use is conceptually distinct from high frequency of SNS use or specific SNS usage patterns, prior research suggested that the more passive forms of SNS use may be more strongly associated with the risk of problematic use (Montag et al., 2024). Therefore, integrating both usage frequency and specific SNS activities into latent profiles may help differentiate the normative and problematic use of SNS.

The Digital Goldilocks Hypothesis. The digital Goldilocks hypothesis (Przybylski & Weinstein, 2017) suggests that digital use, including SNSs use, at moderate levels is not harmful and maybe advantageous in a connected world. Conversely, excessive usage may displace alternate activities while insufficient usage may deprive young people of crucial social information and peer interaction. Hence, a significant finding that has emerged from recent studies (e.g., Brailovskaia et al., 2023) and has been observed previously with traditional media (Scherr, 2018), stems from the non-linear relationship between SNS use and well-being. For example, Brailovskaia et al. (2023) reported that limited use of smartphones, rather than abstaining and non-limited use, were more beneficial to mental health. Though no direct evidence has been reported in terms of SNS use (Fioravanti et al., 2020; Lambert et al., 2022), it is rational to argue that SNS use intensity, as well as its potential nonlinear association with well-being, should be taken into consideration when conceptualizing SNS use profiles. In other words, it would be reasonable that a limited amount of time spent using certain SNS may have benefits for individuals’ well-being, but might lead to detrimental effects if used too much. A person-centered approach, to a large extent, can resolve this issue by putting usage intensity in the spotlight when exploring possible profiles.

Taken together, both theoretical models and empirical studies have demonstrated that the relationship between SNS use and well-being may vary depending on the type and extent of SNS use. Therefore, we propose that different combinations of specific active and passive behaviors may play distinct roles in promoting well-being. Hence, we put forward our second research question:

RQ2: How are SNS use profiles associated with users’ subjective well-being?

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The study was conducted in the spring semester, 2022 via Wenjuanxing website (https://www.wjx.cn), a Chinese survey software comparable to Qualtrics. Using a convenience sampling method, a total of 1,096 undergraduate students from two public universities in southwest China were recruited to participate in this study without any monetary payment. Participant recruitment was distributed via psychology teachers to their students, and we also advertised the survey in online groups at both universities to recruit as many participants as possible. Twenty-one participants were excluded as they did not correctly answer the earnestness-detector item presented in the middle section of the survey. This check item required participants to select a specific answer according to the instruction in the question (i.e., Please select the second option for this question to ensure that your answers to the questionnaire are serious). Finally, a total of 1,075 participants remained in the final sample. The age of participants ranged from 18 to 28 (Mage = 20.43, SD = 1.81), with 366 males (34.05%) and 709 females (65.95%). Approximately 80.84% of the sample were active WeChat users, 74.51% were active Qzone users, and 41.11% were active Sina Weibo users.

Measures

SNS Usage Behaviors

A twelve-item general SNS usage measure adapted from Shaw et al. (2015) was employed to assess the frequency of specific SNS activities. The original scale includes three subscales: two items for passive use (viewing other’s profiles, checking other’s statuses), three items for content production (updating profile, uploading pictures, or updating status) and three items for interactive communication (e.g., chatting with friends, commenting, writing on other’s walls). To measure different types of passive use behaviors, we adapted passive use by adding four items to assess how often people browse content from other unfamiliar people (i.e., out-of-touch contacts and strangers), resulting in six items for passive use. Considering the original scale developed for Facebook, some items were thus modified for Chinese SNSs. For instance, “writing on other’s walls” for Facebook was changed to “writing on other’s message boards” for Chinese SNSs like Qzone. The questionaries asked the participants to indicate how frequently they engaged in each specific activity when they were on SNS on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = never to 5 = very frequently. In the present study, the internal consistency for the SNS use scale was .80. The content production subscale demonstrated adequate internal consistency, with α = .75, whereas the passive use, and interactive communication demonstrated relatively low internal consistency (α = .65 and .63, respectively).

Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction reflects the cognitive component of subjective well-being, which was assessed by the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985). It consists of 5 statements (e.g., In most ways, my life is close to my ideal), and respondents were required to indicate their agreement with each statement on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). Higher scores are indicative of a greater level of life satisfaction. In this study, the life satisfaction scale showed good internal reliability (α = .88).

Positive and Negative Affect

Positive and negative affect reflects the affective component of subjective well-being, which was measured by the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988). The PANAS scale in this study consists of 19 affect adjectives: 9 adjectives for positive affect, and 10 adjectives for negative affect. One positive adjective (“Alert”) was excluded due to its low standardized factor loading (below .30). Participants evaluated their degree of emotions for each affect adjectives in the past few days on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all; 5 = extremely), with higher scores on negative and positive subscales representing higher levels of corresponding affect. In this sample, the Cronbach’s coefficients for positive and negative affect subscales were .93 and .91 respectively.

Covariates

Given that demographic variables such as age and gender have been shown to influence SNS use patterns (Scott et al., 2017), we included them as covariates in our analysis. To assess daily SNS usage time, participants indicated their primary SNS platform (e.g., WeChat, Qzone, Weibo, or others), and estimated the amount of time they spend on this platform each day. Responses were recorded on a 6-point scale, with 1 = less than 10 minutes, 2 = 10 to 30 minutes, 3 = 31 to 60 minutes, 4 = 1 to 2 hours, 5 = 2 to 3 hours, 6 = more than 3 hours.

Data Analyses

Before formal analysis, variables were checked for normality and multicollinearity problems. The skewness and kurtosis test for normality revealed that, for all items, the skewness values ranged from −0.44 to 0.44, and kurtosis values ranged from −1.02 to 1.01, which were well within acceptable ranges (Muthen & Kaplan, 1985). In terms of multicollinearity problems, examination of tolerance values and variance inflation factor (VIF) suggested that potential multilinearity was not a problem in this study, as all tolerance values were larger than .10 and VIF were smaller than 2 (Mertler & Vannatta , 2016). Additionally, we conducted a Harman’s single-factor test for common method bias via factor analysis. The Harman's factor analysis test suggests that if the unrotated solution (with all primary study variables included) produces one factor accounting for more than 40% of the variance, common method bias is present (Hao & Long, 2004).

The main data analysis was conducted in three steps. First, we performed a latent profile analysis (LPA) using Mplus version 8.3 to identify the number of latent profiles. LPA is a person-centered statistical technique used to classify individuals from a heterogeneous population into more homogeneous subgroups based on individuals’ values on continuous indicators (Berlin et al., 2014). We chose LPA over latent class analysis (LCA) because SNS use in the present study was measured as continuous variables, whereas LCA is typically used for categorical indicators. Maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) was used, which is widely used in LPA. One- to six-profile solutions of LPA models were evaluated and compared using a combination of fit indices, parsimony and interpretability. The indices include Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1987), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978), sample-size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (aBIC; Sclove, 1987), entropy, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin test (LMR), and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT; Nylund et al., 2007). Lower values of AIC, BIC and aBIC indicate better model fit to the data (Nylund et al., 2007). Significant p-values (p < .05) of the LMRT suggest that the model with k profiles fits the data better than the model with k-1 profiles (Lo et al., 2001). A higher value of the entropy reflects greater classification precision, with values greater than .80 demonstrating an acceptable classification quality (S. L. Clark, 2010). Additionally, the final model solution was also considered the theoretically meaningful and interpretability of the profiles.

After determining the optimal number of classes, we included covariates in the model to estimate the posterior probability based on the values of covariates. Specifically, age, gender and time spent on SNS were included as covariates, as these variables may influence users’ behavioral patterns on SNS. Finally, we estimated and compared the mean levels of auxiliary variables (i.e., life satisfaction and positive/negative affect) across the latent profiles using the Block-Croon-Hagenaars (BCH) method in Mplus. The BCH procedure is considered one of the most reliable approaches for estimating continuous or binary outcomes variables within a mixture modeling framework (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2021), which has been widely used in LPA to conduct Wald tests to examine differences in distal outcomes across groups (Y. A. Chen et al., 2022; Warren et al., 2020).

Results

Common Method Bias

Common method bias was tested with the three questionnaires (i.e., SNS use, life satisfaction, and positive and negative affect) during factor analysis. Results showed that a total of 6 factors’ eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted. The first factor accounting for 22.65% variance, which was less than the 40% required by the critical standard. This result indicates that common method bias is not a strong influence in the present study.

RQ1: Detecting and Descripting Latent Profiles

Table 1. Model Fit Indices for One- to Six-Profile Patterns of SNS Use (n = 1,075).

|

Model |

m |

AIC |

BIC |

aBIC |

Entropy |

LMR |

BLRT |

Probability |

|

1 |

24 |

35824.28 |

35943.80 |

35867.57 |

1 |

— |

— |

— |

|

2 |

37 |

34190.60 |

34374.87 |

34257.35 |

.75 |

.032 |

< .0001 |

.4348/.5652 |

|

3 |

50 |

33464.45 |

33713.5 |

33554.64 |

.83 |

< .0001 |

< .0001 |

.1296/.5976/.2727 |

|

4 |

63 |

33147.98 |

33461.73 |

33261.62 |

.82 |

.0001 |

< .0001 |

.0955/.4176/.2350/.2520 |

|

5 |

76 |

32935.11 |

33313.59 |

33072.20 |

.81 |

.020 |

< .0001 |

.0911/.2219/.1896/.3652/.1322 |

|

6 |

89 |

32830.18 |

33273.41 |

32990.72 |

.78 |

.775 |

< .0001 |

.0838/.2000/.1735/.1411/.3189/.0827 |

RQ1 asked what SNS use profiles can be obtained based on SNS specific behaviors and their corresponding intensity. To address this question, latent profiles were evaluated based on the responses on 12 items of SNS use. As shown in Table 1, the five-profile solution provided the best overall model fit to the data. The values of AIC, BIC, and aBIC decreased as the number of latent profiles increased, and the smallest values were found in the six-profile solution. However, the LMR tests indicated that the six-profile solution was not an improvement over the five-profile solution (p = .375), suggesting that no more than five profiles were needed. The entropy value also indicated a good fit for the five-profile model. Therefore, the five-profile model was selected as the optimal solution in the present study.

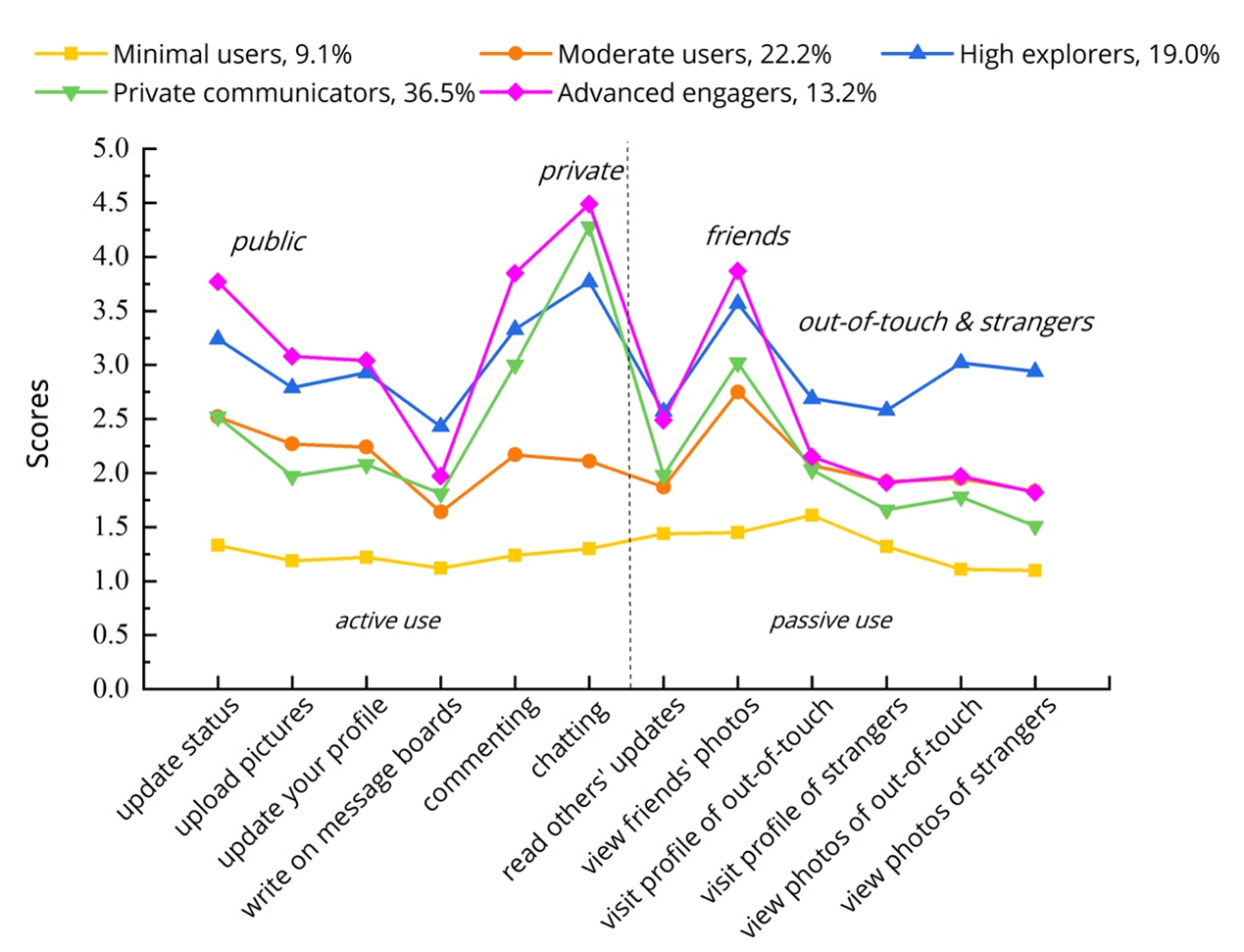

After including gender and time spent on SNS as covariates, the five profiles were identified. Each profile was labeled based on the pattern of mean values across the 12 items of SNS activities. Table 2 presents the means and standard errors of the variables used to define these profiles. A graphical illustration of the five usage profiles is displayed in Figure 1.

Table 2. Descriptive Information for the Five-Profile Model of SNS Use.

|

M (SE)/n (%) |

Minimal users (n = 98; 9.1%) |

Moderate users (n = 238; 22.2%) |

High explorers |

Private communicators |

Advanced engagers (n = 142; 13.2%) |

χ2 |

|

Variables defining profiles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Status updating |

1.33 (.10) |

2.52 (.08) |

3.24 (.12) |

2.52 (.06) |

3.77 (.17) |

|

|

Uploading pictures |

1.19 (.07) |

2.27 (.08) |

2.79 (.09) |

1.97 (.06) |

3.08 (.17) |

|

|

Updating profile |

1.22 (.07) |

2.24 (.06) |

2.93 (.08) |

2.08 (.04) |

3.04 (.14) |

|

|

Writing on others’ message boards |

1.12 (.04) |

1.64 (.06) |

2.43 (.09) |

1.81 (.05) |

1.97 (.14) |

|

|

Commenting |

1.24 (.07) |

2.17 (.08) |

3.33 (.11) |

3.00 (.07) |

3.85 (.12) |

|

|

Chatting |

1.30 (.09) |

2.11 (.07) |

3.77 (.13) |

4.28 (.05) |

4.49 (.09) |

|

|

Reading friends' updates |

1.44 (.12) |

1.87 (.08) |

2.57 (.11) |

1.98 (.07) |

2.49 (.17) |

|

|

Viewing friends' photos |

1.45 (.14) |

2.75 (.08) |

3.57 (.10) |

3.02 (.08) |

3.87 (.10) |

|

|

Visiting out-of-contact persons' profiles |

1.61 (.11) |

2.07 (.07) |

2.69 (.09) |

2.03 (.04) |

2.15 (.16) |

|

|

Viewing out-of-contact persons' photos |

1.11 (.04) |

1.95 (.08) |

3.02 (.08) |

1.78 (.05) |

1.97 (.18) |

|

|

Visiting strangers' profile |

1.32 (.08) |

1.92 (.07) |

2.58 (.08) |

1.66 (.05) |

1.91 (.14) |

|

|

Viewing strangers' photos |

1.10 (.04) |

1.83 (.07) |

2.94 (.13) |

1.51 (.05) |

1.82 (.12) |

|

|

Auxiliary variables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age (range: 18−28) |

19.94 (.30) a |

19.96 (.13) a |

20.41 (.14) b |

20.77 (.12) b,c |

20.64 (.22) b |

32.58*** |

|

Gender |

0.42 (.05) a |

0.61 (.04) b |

0.57 (.04) b |

0.74 (.03) c |

0.85 (.04) d |

58.20*** |

|

Time spent on SNS (range: 1−6) |

3.17 (.20) a |

4.29 (.11) b |

4.57 (.11) c |

4.57 (.08) c |

5.09 (.12) d |

77.09*** |

|

Subjective well-being indicators |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Life satisfaction (range: 1−7) |

3.97 (.22) a,b |

4.08 (.09) b |

4.09 (.10) b |

3.79 (.07) a |

4.27 (.13) b |

13.57** |

|

Positive affect (range:1−5) |

2.54 (.12) a |

2.96 (.05) b |

3.08 (.06) b |

2.94 (.05) b |

3.31 (.09) c |

34.81*** |

|

Negative affect (range: 1−5) |

2.22 (.11) a,b |

2.40 (.06) b |

2.36 (.07) b |

2.03 (.05) a |

2.13 (.08) a |

27.70*** |

|

Note. Gender was coded: 0 = males; 1= females. Time spent on SNS ranged from 1 to 6. Within each row, means with different superscripts are significantly different from each other. **p < .01, ***p < .001. |

||||||

Figure 1. Mean Scores for Each of the Five Identified SNS Use Profiles

Profile 1, labeled Minimal users (9.1%), is characterized by the lowest frequency (close to never) on all SNS activities, which is the least common profile. When comparing the frequency of various activities, users in this profile tended to passively consume content from existing friends and distant contacts, though their overall SNS usage remains minimal.

Profile 2, labeled Moderate users (22.2% of the sample), is characterized by a frequency of usage closest to the average across all SNS activities. These users revealed a middle frequency of broadcasting, a middle frequency of browsing friends' photos, and relatively lower scores on interactive communication activities, including writing on message boards, commenting, and chatting.

Profile 3, labeled High explorers (19.0%), is characterized by high mean values on all SNS activities, indicating both frequent usage and a diverse range of SNS activities, including broadcasting, commenting, chatting, and browsing. Notably, these users have the highest frequency in browsing content from weak ties such as strangers and out-of-contacts, suggesting the strongest preference for seeking information beyond their existing social networks. As a result, this profile was termed "High explorers".

Profile 4, labeled Private communicators (36.5%), is the most prevalent subgroup. This profile is characterized by a high frequency of chatting and moderate frequencies in commenting and browsing friends’ photos. Across all activities, these users prioritize private messaging (i.e., chatting) over broadcasting as a way to maintain social relationships, with chatting ranking second highest among all profiles. This profile was thus termed "Private communicators".

Profile 5, labeled Advanced engagers (13.2%), is characterized by the highest levels of both content contribution (e.g., status updating, uploading pictures) and interactive communication (e.g., commenting, chatting). In addition, these users primarily browse content from their friends rather than that from non-friends. Compared to Profiles 3, Profile 5 reported slightly higher mean scores on indicators of active use and lower scores on browsing content outside their networks. These users were therefore named "Advanced engagers".

Taken together, it appears that college students in this sample tend to use SNS in different behavioral patterns. Minimal and Moderate users showed low to average engagement on SNS, whereas High explorers, Private communicators, and Advanced engagers showed higher engagement and differed in their typical activities. High explorers browsed a broad range of content from both friends and non-friends. Private communicators primarily focus on private messaging, accompanied by moderate levels of commenting, while Advanced engagers frequently participated in broadcasting, social interaction and browsing content from friends.

Demographic Characteristics of the Identified Profiles

Table 2 also shows the descriptions of the five profiles on the covariates. These profiles significantly differed in age, gender and time spent on SNS. Minimal users included a higher proportion of male and younger participants than other profiles. In contrast, Private communicators and Advanced engagers consisted predominantly of females and older participants, especially when compared with Minimal users and Moderate users. In terms of SNS usage time, Advanced engagers reported the highest amount of time on SNS, followed by High explorers and Private communicators, while Minimal users reported the least time spent on SNS.

RQ2: SNS Use Profiles and Subjective Well-Being

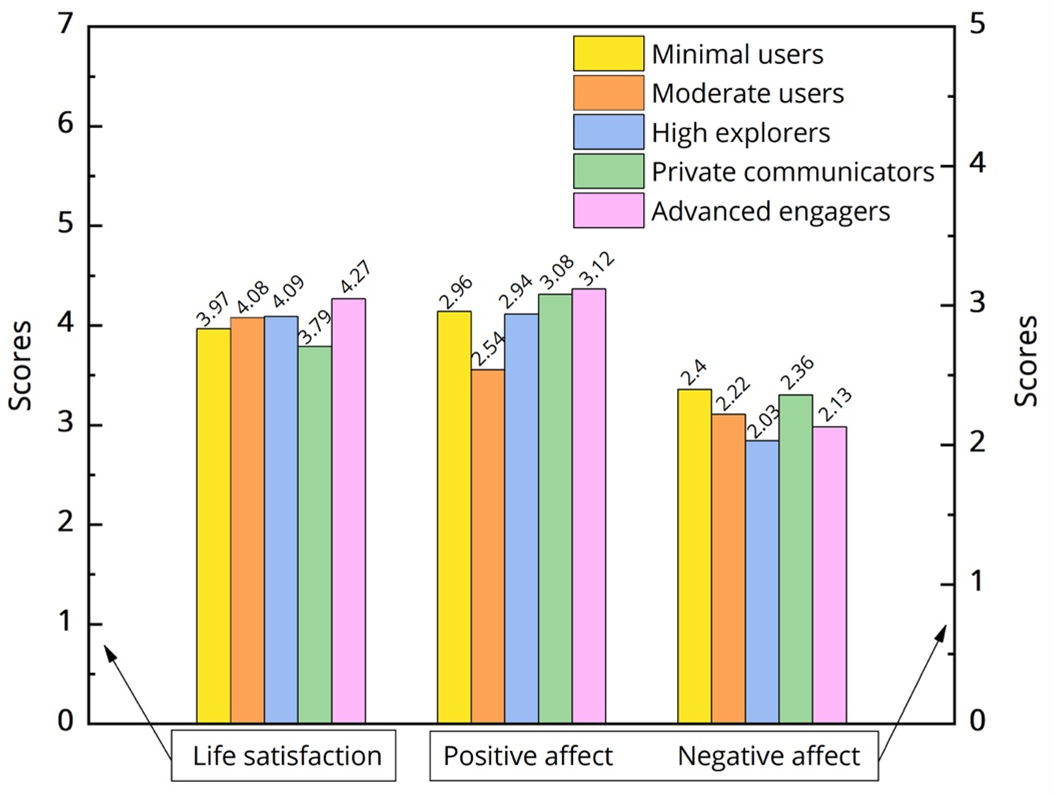

After identifying five latent profiles of SNS use, RQ2 referred to whether there were differences in terms of subjective well-being indicators across these five profiles. Using the BCH approach, we included life satisfaction and positive/negative affect as distal variables to estimate their means for each SNS use profile. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, significant differences were found in life satisfaction (χ2 = 13.57, p = .009), positive affect (χ2 = 34.81, p < .001), and negative affect (χ2 = 27.70, p = < .001) across the five profiles. First, with regard to life satisfaction, the Private communicators reported a significantly lower satisfaction with their lives than the Moderate users (χ2 = 6.15, p = .013), High explorers (χ2 = 5.76, p = .016) and Advanced engagers (χ2 = 9.19, p = .002). No other significant differences were found across other profiles. These results indicated that all SNS users in this study tended to experience similar levels of life satisfaction regardless of their usage patterns, except for those Private communicators, whose life satisfaction was lower than other profiles.

Figure 2. Bar Charts for the Mean Differences in Subjective Well-Being Across SNS Use Profiles Note. Life satisfaction used 7-point scale, and positive and negative affect were 5-point scale.

Note. Life satisfaction used 7-point scale, and positive and negative affect were 5-point scale.

As for positive affect, participants who were Advanced engagers reported the highest level of positive affect among the five profiles, while the Minimal users reported the lowest positive affect. No significant differences were found across profiles of the Moderate users, Private communicators, and Advanced engagers (ps > .05). In terms of negative affect, Private communicators and Advanced engagers reported a similar level of negative affect (χ2 = .89, p = .345), both of which were significantly lower than those who were Moderate users (Private communicators: χ2 = 19.67, p < .001; Advanced engagers: χ2 = 7.01, p = .008) and High explorers (Private communicators: χ2 = 15.45, p < .001; Advanced engagers: χ2 = 4.35, p = .037). Neither the difference between the Moderate users and High explorers, nor the differences between the Minimal users and users in other four profiles were significant in terms of negative affect.

Taken together, these results indicated that SNS users’ subjective well-being differed according to their SNS use patterns. Advanced engagers who use SNS in a highly public and private way with friends (i.e., frequently engaged in broadcasting, interacting and browsing friends’ information) reported a higher level of subjective well-being than other four types of SNS users. Specifically, these users were most likely to experience positive affect, more satisfied with their own lives than Private communicators, and less likely to encounter negative mood than those who were Moderate users or High explorers. In contrast, Moderate users and High explorers tended to experience comparable level of well-being, while the Minimal users reported significantly lower positive affect than other profiles. Another remarkable finding was the subjective well-being of Private communicators, who were the least satisfied with their lives but less likely to encounter negative affect than Moderate users and High explorers.

Discussion

Considering the heterogeneity of SNS activities, this study employed a person-centered approach to identify different combinations of SNS activities and examined their relations to well-being. Rather than classifying SNS use as merely active or passive, this study examined a variety of SNS activities across different communication context (private vs. public) and audience (e.g., friends vs. strangers). Latent profile analysis identified five user profiles: Minimal users, Moderate users, High explorers, Private communicators and Advanced engagers. Among them, Advanced engagers reported the highest level of subjective well-being, followed by Moderate users and High explorers. In contrast, Minimal Users experienced the least positive affect, while Private communicators showed the lowest life satisfaction and relatively low positive affect. These findings emphasize that how and with whom users interact on SNS is crucial to their well-being. By taking a person-centered approach, this study provided more nuanced insights into the relationship between SNS use and well-being among Chinese young adults.

Latent SNS Use Profiles

From the Chinese SNS users' data, we identified five distinct profiles of SNS use: Minimal users, Moderate users and three high-engagement profiles (i.e., High explorers, Private communicators, and Advanced engagers). The findings for these five SNS use profiles suggested that participants in the present study tended to use SNS in five different combinations of usage behaviors, and their usage frequencies and typical activities varied among the different profiles. In the following section, we discussed these five profiles.

We found that more than one-third of the sample were classified as Minimal or Moderate users, indicating that a substantial portion of Chinese college students use SNS in a restrained or balanced way. Specifically, Minimal users (9.1%) showed the lowest frequency on all SNS activities, neither contributing content nor browsing information from others. This profile aligns with the Sporadics (23%) found in Brandtzæg (2012) and the low-frequency users (10%) reported in Scott et al. (2017). Given the digital literacy of our participants, this minimal use may reflect a deliberate disconnection from digital media rather than a lack of digital skills. Recent studies have shown that some individuals perceive their SNS use as "non-meaningful and dissatisfactory" (Nguyen et al., 2024), which may motivate them to reduce their engagement on SNS in order to pursue a healthier balance between online and offline life (Matthes et al., 2022). In contrast, Moderate users (22.2%) showed average levels on all SNS activities, and they engaged moderately in broadcasting and browsing, but relatively less in interactive behaviors (second only to Minimal users). Neither of these two profiles showed a strong preference for specific SNS activities, suggesting a restrained yet balanced usage style. Future research could further investigate whether such low to moderate usage patterns reflects intentional digital disconnection rather than deficits in digital competence.

Beyond these users, we identified three distinct high-engagement profiles that reflected the diverse ways in which Chinese college students interact with other and consume content on SNS. High explorers (19% of the sample) exhibited the broadest range of SNS activities. These users not only actively contributed, interacted with others, but also widely browsed content from both friends and distant or unfamiliar others. This was the only profile characterized by high exposure to content from non-friends, suggesting a strong orientation toward social expansion and information seeking beyond existing networks. In contrast, Private communicators (36.5%) showed a clear preference for private, dyadic communication. Their SNS use primarily involved private messaging alongside other forms of targeted interaction (e.g., commenting), which reflected a communication style aimed to maintain the existing social relationships. Finaly, Advanced engagers (13.2%) demonstrated a socially active and diverse pattern of SNS use, manifested as frequent engagement in both private interactions (e.g., chatting and commenting) and public contributions (e.g., broadcasting). Unlike High explorers, who heavily consume content from distant or unfamiliar others, Advanced engagers primarily consumed content from strong-tie networks (i.e., friends). Their friend-oriented engagement style integrates social interaction and self-expression within familiar social networks. Taken together, these three high-engagement profiles revealed the nuanced ways in which Chinese students use SNS moving beyond the simplistic categories of "active use" or "passive use". Future research should further explore the underlying psychological motivations, such as self-presentation, social connection, and information-seeking (Kim et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015), to better understand the antecedents of these distinct communication styles.

It is worth noting that while all users except Minimal users showed moderate to high frequencies in browsing friends' photos, we did not identify any subgroup characterized as predominantly passive use combined with minimal active engagement (e.g., high passive-low active use). Instead, profiles identified in this study reflected either balanced engagement on SNS activities or frequent, interactive use. This indicated that visual content consumption plays a central role in daily SNS use among Chinese college students, while it typically co-occurs with content production and/or interactive behaviors, rather than functioning as an isolated usage style. This finding is inconsistent with previous research that identified a subgroup of passive users, often labeled as "lurkers", who primarily engage in browsing behaviors without contributing content (Brandtzæg, 2012; Lin, 2019). Three potential explanations may apply to the absence of such passive users. First, this study was conducted in a typical collectivist society (i.e., China) where users might be more likely to use SNS for seeking social support (Kim et al., 2011). In this case, users may be more inclined to an active or a balanced way to engage with SNS to satisfy these social motivations. Second, increasing social media literacy among young adults may also help explain the absence of a passive user profile. Recent studies suggested that concerns about the harmful effects of passive use may prompt users to use SNS in a more intentional and active manner (Cho et al., 2024). Although this study cannot examine this possibility, future research could consider the influence of social media literacy on users profiles. Finally, the lack of a passive subgroup may reflect a sampling limitation. That is, users with predominantly passive behaviors may be less likely to respond to our online advertisement, and thus were underrepresented in the sample. Further research would benefit from improving the recruitment procedure to include more heterogenous populations to detect a broader range of SNS use styles.

SNS Use Profiles and Subjective Well-Being

We found that the relationship between SNS use and well-being depended on users' specific communication styles. Consistent with augmentation hypothesis (Valkenburg & Peter, 2007) and social enhancement hypothesis (Zywica & Danowski, 2008), Advanced engagers reported the highest levels of well-being. Specifically, they had the highest life satisfaction, most positive affect and less negative affect than users in other profiles. The underlying mechanism might be that these users engaged in a balanced combination of targeted (e.g., private messaging) and nontargeted (e.g., broadcasting) communication, which may facilitate both social relationship maintenances and effective impression management. For instance, by actively sharing content and interacting with others, they may increase the opportunities to receive social support and also manage their public image on SNS (Burke & Kraut, 2016). In addition, frequently browsing friends’ content allows them to keep up with their existing friends and provide timely responses (e.g., commenting), thereby reinforcing social bonds (Metzger et al., 2018). In these ways, such diverse and active engagement may help Advanced engagers cultivate a reciprocal and supportive online network, which ultimately enhances their subjective well-being.