Online experience sharing without explicit social interaction does not foster social bonding

Vol.19,No.1(2025)

Humans have a unique capacity to bond with others through shared experiences, even in the absence of explicit communication. Yet it is unknown whether this capacity is flexible enough to accommodate the different kinds of virtual environments on which we increasingly rely. In the current pre-registered study, we examined whether this capacity still operates effectively on shared screens during non-communicative video mediated interactions, in dyads and in groups. Participants (N = 144 US participants, 71 female, 72 male, 1 non-binary) either watched a video on a shared screen together with (pre-recorded) partners or watched individually while these partners attended to something else. Equivalence tests showed that self-reported social bonding scores were practically equivalent between conditions. Thus, in contrast to several in-person studies, there was no difference in social bonding between conditions. These results show that, in the absence of explicit communication, some of humans’ most fundamental social bonding mechanisms might not operate as effectively in video mediated social interactions. As such, without sufficient active social or emotional engagement, the social costs of increasingly relying on video mediated social interactions might be greater than previously thought.

video mediated communication; social bonding; shared experiences; social relationships; social interactions

Wouter Wolf

Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, United States; Department of Psychology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Wouter Wolf obtained his PhD in developmental psychology from Duke University and is currently an assistant professor at the department of developmental psychology at Utrecht University. His research interests include the evolution of social cognition and social bonds, and how these operate in the modern, digital world.

Kayley Dotson

Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, United States; Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States

Kayley Dotson is a graduate student at developmental psychology program of the University of Michigan. Her research interests include social cognition, cooperation, and reciprocity.

Angus, S. D., & Newton, J. (2015). Emergence of shared intentionality is coupled to the advance of cumulative culture. PLOS Computational Biology, 11(10), Article e1004587. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004587

Artinger, L., Clapham, L., Hunt, C., Meigs, M., Milord, N., Sampson, B., & Forrester, S. A. (2006). The social benefits of intramural sports. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 43(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.1572

Baldwin, D. A. (1995). Understanding the link between joint attention and language. In C. Moore, P. J. Dunham, & P. Dunham (Eds.), Joint attention: Its origins and role in development (pp. 131–158). Psychology Press.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Boothby, E. J., Clark, M. S., & Bargh, J. A. (2014). Shared experiences are amplified. Psychological Science, 25(12), 2209–2216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614551162

Carpenter, M., Nagell, K., & Tomasello, M. (1998). Social cognition, joint attention, and communicative competence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 63(4),

1–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166214

Charles, S. J., van Mulukom, V., Brown, J. E., Watts, F., Dunbar, R. I. M., & Farias, M. (2021). United on sunday: The effects of secular rituals on social bonding and affect. PLOS One, 16(1), Article e0242546. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242546

Cheong, J. H., Molani, Z., Sadhukha, S., & Chang, L. J. (2023). Synchronized affect in shared experiences strengthens social connection. Communications Biology, 6(1), Article 1099. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-023-05461-2

Choi, M., & Choung, H. (2021). Mediated communication matters during the COVID-19 pandemic: The use of interpersonal and masspersonal media and psychological well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(8), 2397–2418. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211029378

Cleveland, A., Schug, M., & Striano, T. (2007). Joint attention and object learning in 5- and 7-month-old infants. Infant and Child Development, 16(3), 295–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.508

Cui, M., Zhu, M., Lu, X., & Zhu, L. (2019). Implicit perceptions of closeness from the direct eye gaze. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 2673. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02673

Dabbish, L. A. (2008). Jumpstarting relationships with online games: Evidence from a laboratory investigation. Proceedings of the 2008 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 8, 353–356. https://doi.org/10.1145/1460563.1460620

De Felice, S., Vigliocco, G., & Hamilton, A. F. de C. (2021). Social interaction is a catalyst for adult human learning in online contexts. Current Biology, 31(21), 4853–4859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.08.045

Depping, A. E., & Mandryk, R. L. (2017). Cooperation and interdependence: How multiplayer games increase social closeness. Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, 17, 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1145/3116595.3116639

Dunbar, R. I. M. (2004). Gossip in evolutionary perspective. Review of General Psychology, 8(2), 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.100

Dunbar, R. I. M., Teasdale, B., Thompson, J., Budelmann, F., Duncan, S., van Emde Boas, E., & Maguire, L. (2016). Emotional arousal when watching drama increases pain threshold and social bonding. Royal Society Open Science, 3(9), Article 160288. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160288

Furukawa, R., & Driessnack, M. (2012). Video-mediated communication to support distant family connectedness. Clinical Nursing Research, 22(1), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773812446150

Furukawa, R., Driessnack, M., & Kobori, E. (2017). The impact of a video-mediated communication on separated perinatal couples in Japan. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 29(2), 202–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659617692394

Haj-Mohamadi, P., Fles, E. H., & Shteynberg, G. (2018). When can shared attention increase affiliation? On the bonding effects of co-experienced belief affirmation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 75, 103–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.11.007

Hirsch, J. L., & Clark, M. S. (2018). Multiple paths to belonging that we should study together. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(2), 238–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618803629

Kleinke, C. L. (1986). Gaze and eye contact: A research review. Psychological Bulletin, 100(1), 78–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.100.1.78

Liszkowski, U., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (2007). Reference and attitude in infant pointing. Journal of Child Language, 34(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000906007689

Lorenzo, G. L., Biesanz, J. C., & Human, L. J. (2010). What is beautiful is good and more accurately understood: Physical attractiveness and accuracy in first impressions of personality. Psychological Science, 21(12), 1777–1782. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610388048

Mahaphanit, W., & Chang, L. (2023). Shared experiences strengthen social connectedness through shared impression formation and communication behavior. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 45. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2bp9v575

Marsman, M., & Wagenmakers, E. J. (2016). Bayesian benefits with JASP. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14(5), 545–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1259614

Oppenheimer, D. M., Meyvis, T., & Davidenko, N. (2009). Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 867–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.009

Pearce, E., Launay, J., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2015). The ice-breaker effect: Singing mediates fast social bonding. Royal Society Open Science, 2(10), Article 150221. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150221

Rennung, M., & Göritz, A. S. (2015). Facing sorrow as a group unites. PLOS One, 10(9), Article e0136750. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136750

Shteynberg, G. (2015). Shared attention. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(5), 579–590. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615589104

Shteynberg, G. (2018). A collective perspective: Shared attention and the mind. Current Opinion in Psychology, 23, 93–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.12.007

Shteynberg, G., Hirsh, J. B., Apfelbaum, E. P., Larsen, J. T., Galinsky, A. D., & Roese, N. J. (2014). Feeling more together: Group attention intensifies emotion. Emotion, 14(6), 1102–1114. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037697

Shteynberg, G., Hirsh, J. B., Wolf, W., Bargh, J. A., Boothby, E. J., Colman, A. M., Echterhoff, G., & Rossignac-Milon, M. (2023). Theory of collective mind. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 27(11), 1019–1031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2023.06.009

Sijilmassi, A., Safra, L., & Baumard, N. (2024). “Our roots run deep”: Historical myths as culturally evolved technologies for coalitional recruitment. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 47, Article e171. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X24000013

Singh, P., Tewari, S., Kesberg, R., Karl, J. A., Bulbulia, K., & Fischer, R. (2020). Time investments in rituals are associated with social bonding, affect and subjective health: A longitudinal study of Diwali in two Indian communities. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 375(1805), Article 20190430. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0430

Siposova, B., & Carpenter, M. (2019). A new look at joint attention and common knowledge. Cognition, 189, 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2019.03.019

Siposova, B., Tomasello, M., & Carpenter, M. (2018). Communicative eye contact signals a commitment to cooperate for young children. Cognition, 179, 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.010

Tomasello, M. (2008). Origins of human communication. MIT press.

Tomasello, M. (2014). A natural history of human thinking. Harvard University Press.

Tomasello, M. (2016). A natural history of human morality. Harvard University Press.

Tomasello, M. (2019). Becoming human. A theory of ontogeny. Harvard University Press.

Tomasello, M., & Carpenter, M. (2006). Shared intentionality. Developmental Science, 10(1), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00573.x

Tomasello, M., & Vaish, A. (2013). Origins of human cooperation and morality. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 231–255. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143812

van Doorn, J., van den Bergh, D., Böhm, U., Dablander, F., Derks, K., Draws, T., Etz, A., Evans, N. J., Gronau, Q. F., Haaf, J. M., Hinne, M., Kucharský, S., Ly, A., Marsman, M., Almirall, D., Gupta, A. R. K., Sarafoglou, A., Stefan, A., Voelkel, J. G., & Wagenmakers, E. J. (2020). The JASP guidelines for conducting and reporting a Bayesian analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 28(3), 813–826. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-020-01798-5

Williams, K. D., Cheung, C. K. T., & Choi, W. (2000). Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 748–762. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.748

Williams, K. D., & Jarvis, B. (2006). Cyberball: A program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behavior Research Methods, 38(1), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192765

Wolf, W. (2024). The social cognitive evolution of myths: Collective narratives of shared pasts as markers for coalitions’ communicative and cooperative prowess. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 47, Article e195. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x24000761

Wolf, W., Launay, J., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2015). Joint attention, shared goals, and social bonding. British Journal of Psychology, 107(2), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12144

Wolf, W., Levordashka, A., Ruff, J. R., Kraaijeveld, S., Lueckmann, J. M., & Williams, K. D. (2014). Ostracism online: A social media ostracism paradigm. Behavior Research Methods, 47(2), 361–373. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-014-0475-x

Wolf, W., & Tomasello, M. (2019). Visually attending to a video together facilitates great ape social closeness. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 286(1907), Article 20190488. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.0488

Wolf, W., & Tomasello, M. (2020a). Human children, but not great apes, become socially closer by sharing an experience in common ground. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 199, Article 104930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2020.104930

Wolf, W., & Tomasello, M. (2020b). Watching a video together creates social closeness between children and adults. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 189, Article 104712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2019.104712

Wolf, W., & Tomasello, M. (2023). A shared intentionality account of uniquely human social bonding. Perspectives on Psychological Science. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231201795

Yarmand, M., Solyst, J., Klemmer, S., & Weibel, N. (2021). “It feels like I am talking into a void”: Understanding interaction gaps in synchronous online classrooms. Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 21, Article 351. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445240

Zheng, J., Veinott, E., Bos, N., Olson, J. S., & Olson, G. M. (2002). Trust without touch: Jumpstarting long-distance trust with initial social activities. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2, 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1145/503376.503402

Authors’ Contribution

Wouter Wolf: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, supervision and writing—original draft. Kayley Dotson: investigation, methodology, and writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

July 14, 2024

Revisions received:

October 11, 2024

January 16, 2025

Accepted for publication:

January 17, 2025

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

To satisfy their fundamental need for belonging (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), humans create social connections in unique ways: they bond by creating shared experiences with others (Hirsch & Clark, 2018; Shteynberg et al., 2023; Wolf & Tomasello, 2023), for example by engaging in shared social activities together, such as gossiping (Dunbar, 2004), making music (Pearce et al., 2015), playing team sports (Artinger et al., 2006), engaging in rituals (Charles et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2020), listening to stories and myths (Sijilmassi et al., 2024; Wolf, 2024) or watching movies (Wolf & Tomasello, 2020b). By making inferences about the mental states of others during these activities individuals create shared representations of their activities, which in turn seem to generate a sense of closeness between them (Shteynberg et al., 2023; Wolf & Tomasello, 2023). Importantly, however, the way humans engage in social interactions (and thus share experiences) has dramatically changed over the past few decades. Humans have become increasingly dependent on virtual social interactions, for example in digital classrooms and remote workplaces. Yet we know relatively little about the degree to which our capacity to bond through shared experiences is flexible enough to accommodate these novel, virtual environments.

Recent theory and empirical work on social bonding through shared experiences has suggested that the inferential psychology underlying bonding through shared experiences has a layered structure. On a basic level, inferring that another individual is going through a similar experience has been shown to facilitate social bonding in both humans and great apes. That is, several studies have shown that participants behave more socially after going through the same experience, even when experimenters are instructed to not communicate with or look at the participant, and/or are placed in front of the participant to make them unavailable for explicit social interaction (Wolf & Tomasello, 2019, 2020b; Wolf et al., 2015). At this level, individuals seem to predominantly rely on implicit social cues about what others are experiencing, such as the direction and movement of their gaze, to infer that their experience is to some degree shared with this other individual.

In addition, humans seem to have an additional, perhaps unique capacity to infer mutual awareness (i.e., both individuals know that both individuals know) about their experience being shared (Carpenter et al., 1998; Shteynberg et al., 2023; Siposova & Carpenter, 2019; Wolf & Tomasello, 2023) which seems to make social bonding through shared experiences even more effective (Wolf & Tomasello, 2020a). To make these inferences, humans seem to predominantly rely on linguistic communication (Shteynberg et al., 2023; Tomasello, 2008; Wolf & Tomasello, 2023), but also use more subtle, implicit cues to infer that their experiences are shared, such as eye contact (Siposova et al., 2018). For example, in a comparative experiment children (but not great apes) were more willing to interact with an experimenter when this experimenter attempted to create mutual awareness about a video watching experience being shared through communicative eye contact than when the experimenter merely sat in front of the subject watching the same video and only made eye contact later in the procedure, unrelated to the shared experience (Wolf & Tomasello, 2020a). The capacity to create mutual awareness about shared experiences is thus not only a key component of humans’ unique forms of communication, cooperation and social learning (Angus & Newton, 2015; Baldwin, 1995; Cleveland et al., 2007; Shteynberg, 2015, 2018; Tomasello, 2008, 2014, 2016, 2019; Tomasello & Carpenter, 2006; Tomasello & Vaish, 2013), but also plays an instrumental role in humans’ unique forms of social bonding (Dunbar et al., 2016; Haj-Mohamadi et al., 2018; Rennung & Göritz, 2015; Shteynberg et al., 2023; Wolf et al., 2015; Wolf & Tomasello, 2020a, 2020b, 2023).

Yet the question remains to what extent novel, digital forms of social interaction still allow people to make the inferences necessary for them to bond through shared experiences. In general, social bonding (as well as social exclusion) has been shown to occur in a variety of virtual environments, such as social media, online gaming, or small scale video mediated conversations (Dabbish, 2008; Depping & Mandryk, 2017; Williams & Jarvis, 2006; Williams et al., 2000; Wolf et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2002). Specifically, online video mediated conversations seem to be an effective tool to maintain social relationships (Choi & Choung, 2021), for example with geographically distant family members (Furukawa & Driessnack, 2012) or within long-distance romantic relationships (Furukawa et al., 2017). In fact, a recent online experiment with a procedure very similar to that of many of the in-person studies on the social bonding effect of shared experiences (Mahaphanit & Chang, 2023) showed that when online participants watched a reality show on a shared screen, but were unaware that, for part of their group, the video was different. Participants felt closer towards individuals who, in reality watched the same video compared to those who did not and, importantly, felt more connected to partners who responded to their message more quickly during the group chat. These results highlight the importance of shared (interpretations of) experiences through explicit communication for social bonding during online video mediated shared experiences. These findings suggest that sharing experiences through video mediated social interactions facilitates social bonding, at least when there are sufficient opportunities for explicit communicative engagement.

However, research has also shown that video mediated social interactions on a larger scale (e.g., online lectures) suffer from reduced explicit communicative engagement among its participants relative to in-person settings (Yarmand et al., 2021). This means that, to effectively bond through shared experiences in those settings, people will have to rely more on implicit social cues like gaze movements and eye contact. Yet these social cues might be particularly difficult to pick up in video mediated social interactions.

For example, in video mediated interactions individuals cannot see their partners’ screens, making it more difficult to infer whether a partner is attentive or distracted based on gaze direction alone. Furthermore, in these types of interactions (communicative) eye contact is not possible, removing a commonly used signal for establishing mutual awareness of a shared experience from people’s inferential repertoires (Siposova et al., 2018; Wolf & Tomasello, 2020a).

Because access to these types of social information is more limited in video mediated interactions than in in-person social interactions, it might be more difficult to infer that an experience is shared, potentially limiting the degree to which people can bond through shared experience during video mediated interactions in the absence of more explicit (e.g., linguistic) social engagement. This might have far-reaching implications for the wellbeing of participants of (especially large scale) video mediated interactions with limited opportunities for explicit communication (such as virtual classrooms), as well as the social cohesion within their communities.

To find out whether non-communicative shared experience in video mediated interactions facilitate social bonding, we conducted an experiment similar to previous in-person studies on the effect of joint attention on social bonding: Participants engaged in an online video-mediated social interaction (which, unbeknownst to the participant, were pre-recorded videos of confederates). They did so in either a dyad or in a group of four, as previous research has shown that social bonding through jointly attended stimuli can occur both in dyads (Dunbar et al., 2016; Haj-Mohamadi et al., 2018; Wolf & Tomasello, 2019, 2020b, 2020a; Wolf et al., 2015) as well as in larger groups (Rennung & Göritz, 2015).

Similar to previous in-person studies on the effects of joint attention on social bonding (Wolf & Tomasello, 2019, 2020b; Wolf et al., 2015), participants were instructed not to communicate with others in both conditions. Crucially, however, in the joint attention condition, participants were told that they were watching a video on a shared screen together with the other “participants”. In the disjoint attention condition, on the other hand, participants were told that everyone would watch the video sequentially, meaning that the participant watched the video individually while the other “participants” were instructed to do what they wanted as long as they remained within the visual field of the camera (in practice, they always attended to their phone). We then measured participants’ self-reported social bonding to the other participants. In addition, we also asked participants about how they experienced watching the video to see if other, previously found social consequences of sharing experiences online through instruction (i.e., emotion amplification, see: Shteynberg et al., 2014) would also manifest in the current social interaction based procedure.

Methods

Pre-Registration and Data Availability Statement

The current study (Hypotheses, data collection procedure, analyses) was pre-registered here and anonymized data can be accessed at OSF here.

Participants and Design

The Participants from the US between 18 and 30 years old were recruited online through a variety of databases that included students and alumni of the local university, as well as members of the local community (i.e., convenience sample). Previous studies on similar questions in face-to-face interactions used 32 participants per between subjects cell (e.g., Wolf & Tomasello, 2020a). Our aim was for our sample to be similar. However, in order to counterbalance the use of 3 separate stooge videos in the dyad condition, we aimed for 36 included participants per cell in our 2 (Attention: Joint vs Disjoint) by 2 (Group size: Dyad vs Group) design, totaling 144 included participants. We collected data from 225 participants, 81 of which were excluded for a variety of reasons, such as inattentiveness (i.e., failing the comprehension questions or instructional manipulation check, not being aware whether the other participants were watching with them or doing something else, or indicating to be inattentive during the manipulation; n = 61), indicating that they were suspicious that the other participants were confederates (n = 8), not following instructions (n = 8), experimenter error (n = 2), and technical difficulties (n = 2). As such, our final sample, as planned, included 144 participants (Mage = 20.17, SDage = 2.19), 71 of which identified as female, 72 as male and 1 as non-binary. Furthermore, participants’ ethnic backgrounds included Asian (n = 69), White/Caucasian (n = 43), Mixed (n = 12), African American (n = 10), and Hispanic (n = 8), while 1 participant indicated not wanting to answer this question and 1 other participant left this question blank. Participants were compensated with a $10 gift card or course credits. The research was approved by ethics committee of Duke University, NC (USA).

Procedure

After registering for the study, participants received an email in which they were told that they would be taking part in an online video call (i.e., through Zoom) with other participants. They were asked to use a laptop or desktop to join the call. In this email they also received a link to a survey that contained an informed consent form and questions about their demographics (i.e., age, gender, race, and student ID, if they had one). The informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Furthermore, participants were told that all of the participants in the study would first meet with the experimenter separately to go over some instructions and to make sure everyone’s set up worked properly. Participants saw a list of names including their own, with a specific time indicated to join the meeting for each name. In reality, participants always received an email with their name at the bottom of the list, so that the experiment always started immediately after the experimenter had gone over the instructions with them.

Once participants joined the meeting, they were welcomed by the experimenter who went through the instructions with them. To standardize the experience as much as possible for participants, they were asked to (1) have their video enabled and (2) their microphones muted once the study started, (3) only have one monitor active during the study, (4) make sure that their names were displayed in the bottom corner in Zoom, and (5) make sure that they could see all the participants in the call who were not in break out rooms displayed on top of the screen the experimenter was sharing. Furthermore, the experimenter also checked whether participants knew (1) how to use the chat feature in Zoom, (2) how to open a link from the chat feature of Zoom to display in a browser on their computer, and (3) how to take a screenshot of the Zoom call and save this screenshot for later use.

During this initial stage, participants were also informed about what was going to happen during the study procedure. They were told that after the instruction was over the experimenter would have all participants join the meeting, after which the experimenter would share a video about animals from the National Park Service through a shared screen. The experimenter also indicated that they would disable their own camera and microphone right before the video would start, to ensure that they would not disturb the experiment. In addition, the experimenter told the participants that if they wanted to contact them, they could send them a private message over Zoom chat.

Crucially, in the joint attention condition participants were told that all the participants in the Zoom call would be watching a video on a shared screen, whereas in the disjoint attention condition they were told that one person at a time would watch the video, sequentially, while the other participants could do something else while they waited, as long as they remained visible on their camera. In reality, the participant always went first (i.e., in both conditions the participant always watched the video at the start of the experiment). While giving these instructions to participants in the disjoint attention condition, the experimenter suddenly “realized” that the participant would be watching the video first, and that some of these instructions were therefore not particularly relevant to them. In reality, this instruction was meant to make clear to the participant that the other participants might be doing something else while the participant was watching the video.

Once the experimenter had finished the instructions and asked the participants if they had any more questions, the experimenter let the “other participant(s)” out of the breakout room. These other participants were pre-recorded videos of student aged individuals who were not part of the local student community (to decrease the risk of pre-existing social relationships between the participant and the confederates). Sufficient male and female confederate videos were created so that the gender of the confederates could be matched to the participant (similar to in previous in-person research, see: Wolf et al., 2015). That is, for each confederate we made a joint attention and disjoint attention video, resulting in a total of three male joint attention videos, three male disjoint attention videos, three female joint attention videos, and three female disjoint attention videos. Crucially, in the dyads only one additional participant entered the call, whereas in the larger group, three additional participants entered the call. To create this group, the experimenter controlled either two (small group) or four (large group) computers, where all but one computer (i.e., the one the experimenter was using to interact with the participant) had an opaque piece of paper taped over the camera. This then allowed the experimenter to play the videos of the confederates as background videos in Zoom in a way that made the confederates appear to be real life participants. In the dyad condition, we counterbalanced which of the three confederates’ videos that were congruent to the participants’ condition and gender was used.

Once the other participants had joined, the experimenter briefly welcomed the participants and asked everyone if they could still hear them. To make the confederate videos more credible as real participants, two sentences were timed so that the videos of the confederates gave a thumbs up and/or a nod immediately after a question, making it seem like they responded to the experimenter’s question. Next, the experimenter started the video, which (similar to previous in-person studies: Wolf & Tomasello, 2020a, 2020b) was a short sequence of documentary style scenes on animal behavior, without sound. In the joint attention condition, the confederates in the videos kept paying attention to their screen(s) throughout the manipulation, whereas in the disjoint attention condition, the confederates disengaged from their screen(s) and looked at their phone for the remainder of the procedure (see Figure 1 for an overview of the conditions). In both conditions, the confederates were asked to remain neutral in their affect. Moreover, confederates were instructed to, from the moment the video started, either continuously attend to their screen (joint attention condition) or their phone (disjoint attention condition) without doing anything else.

Figure 1. Participant View for Each of the Conditions.

After the video had finished, the experimenter sent a private message to the participant containing the link to the survey and their participant number, which participants filled in on the first page of the survey. Next, participants were asked to take a screenshot of the Zoom call and save it so they could upload it later in the survey. They were then instructed to leave the Zoom meeting and completed the rest of the survey, which contained comprehension questions (i.e., attention manipulation checks), questions about the experience of watching the video, social bonding questions about the other participants, and several additional questions and manipulation checks. Finally, participants read the debriefing and exited the survey, after which they were compensated within 24 hours of their participation.

Measures

All self-reported questions were answered on 100-point slider scales in Qualtrics. For all scales, the starting value was 50, similar to previous research using social bonding scales (Wolf et al., 2015). For all questions a response was requested. In total, in all the dependent measures 14 questions were left empty by participants. As it is impossible to know whether participants meant to answer 50 to these questions (and therefore did not move the slider), or whether they could not or did not want to answer these questions, these answers were coded as missing.

Attentiveness Manipulation Check

To catch inattentive participants, we asked them three questions about the content of the video, namely what the main subject of the video was (i.e., mountains, animals, airplanes or beaches, the correct answer being animals), whether or not there was a monkey in the video (true), and whether or not there was a koala bear in the video (false). Furthermore, we also asked participants how many participants (including themselves and the host) were in the Zoom call during the experiment (i.e., three, four, or five, with the correct answer being three for the dyads and five for the larger groups). Participants that answered these questions wrong were excluded from data analysis.

Instructional Manipulation Check

In the midst of the questions on watching experience, we included an instructional manipulation check (Oppenheimer et al., 2009). Participants were presented with an item that said: Please place the slider on exactly 37. This is used to spot inattentive participants. Participants that did not follow these instructions were excluded from data analysis.

Social Bonding

For each set of questions (i.e., once for participants in the dyad condition, three times for participants in the group condition) participants were first asked to enter the name of (one of) the participant(s). If they had forgotten the name, they were encouraged to look at the screenshot they took earlier. Participants who put down the name of the experimenter were excluded from the sample. Next, to measure social bonding, we asked participants to answer eight questions on how they felt about this other participant (i.e., separate for each participant in the large group condition) on a 100-point slider scale. Specifically, we asked participants how much they liked the other participant and to what extent they thought the participant was liked by others on scale 0 (not at all) to 100 (a lot), how positively they felt towards that participant on scale 0 (very negatively) to 100 (very positively), how much they trust this participant and how much they connected with them on scale 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much), how cooperative they felt towards that participant on scale 0 (not at all) to 100 (very cooperative), to what extent they felt close with that participant on scale 0 (not at all close) to 100 (extremely close), and, if they had to do a similar task again, how they would feel about doing that task again with this participant on scale 0 (I would prefer to do it with someone else) to 100 (I would prefer doing it with the same person).

These questions were then collapsed into a single social bonding score, and for the larger group cells, averaged across the three confederates. These questions were almost identical to the questions of the social bonding scale of previous research (Wolf et al., 2015), aside from replacing the Inclusion of Other in Self scale with a more generic question about perceived social closeness. This new question seemed more intuitive in a setting in which participants were not in close physical proximity and was also more consistent with the rest of the scale in terms of response format. Analyses also showed similar reliability for this scale, Posterior mean of Bayesian Cronbach’s α = .78, 95% HDI = [.74, .82], as in previous research (e.g., Wolf et al., 2014).

Watching Experience

As previous research has shown that shared experiences also intensify experiences (Boothby et al., 2014), we did an exploratory analysis in which we asked participants to indicate on a 100-point slider scale how much they liked watching the video, how much they enjoyed watching the video, and how much they liked the video on scale 0 (not at all) to 100 (a lot). Furthermore, we also asked them how often they were distracted during the video on scale 0 (never) to 100 (all the time). Finally, we asked participants whether they would like to watch the video again by themselves and how attentive they were during the video on scale 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much).

Additional Questions and Manipulation Checks

At the end of the survey, we asked participants how attractive they found the other participant(s) on scale 0 (not at all) to 100 (very attractive), to be able to control for this potential social bonding confound (Lorenzo et al., 2010). In addition, to make sure that participants did not feel like participants in the disjointed condition violated a social norm by looking at their phone during the video, we also asked participants how impolite they found the other participant(s) on scale 0 (not at all) to 100 (very impolite). These items were not part of the pre-registration but added after registering (but before the start of data collection) based on external feedback.

As an extra attentional manipulation check, we asked participants how aware they were of the other participants during the video on scale 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much). Finally, at the very end of the survey, we asked participants two open ended questions, namely: (1) What were the other participants instructed to do during the video, and did they follow these instructions? and (2) Sometimes people develop ideas about what studies are about and what researchers are trying to find. If you have any thoughts about what we are studying, please describe them below. These questions were meant to see if participants were suspicious about the confederates in the experiment and/or were aware of what the manipulation was trying to achieve. Suspicious participants were excluded from data analysis.

Results

Social Bonding

The standardized residuals of the social bonding scores (skewness = 0.28, kurtosis = 0.12) indicated that the data were appropriate for using standardized Bayesian models with default uninformed priors and normal likelihoods in JASP 0.16.2 (Marsman & Wagenmakers, 2016), using 100,000 posterior samples for estimation. To estimate the effect of the attention manipulation and group size on social bonding scores, we conducted a 2 x 2 between subjects Bayesian GLM with condition and group size as independent variables and the social bonding scores as dependent variables.

The Bayes Factors (i.e., BFM and BF10) in Table 1 show that of all the possible models, the Null model (i.e., without any predictor variables) was by far the most likely one, showing no main effect of the attention manipulation or group size, nor an interaction effect on social bonding scores.

Table 1. Model Comparison Parameters for Social Bonding Models.

|

Models |

P(M) |

P(M|data) |

BF10 |

|

Null model |

.20 |

.62 |

1.00 |

|

Group size |

.20 |

.21 |

0.34 |

|

Attention |

.20 |

.12 |

0.19 |

|

Attention + Group size |

.20 |

.04 |

0.07 |

|

Attention + Group size + Attention * Group size |

.20 |

.01 |

0.02 |

|

Note. The P(M) is the probability of the model before the data; The P(M|data) is the probability of the model after accounting for the data; The BF10 is the Bayes Factor of that model relative to the most likely model. |

|||

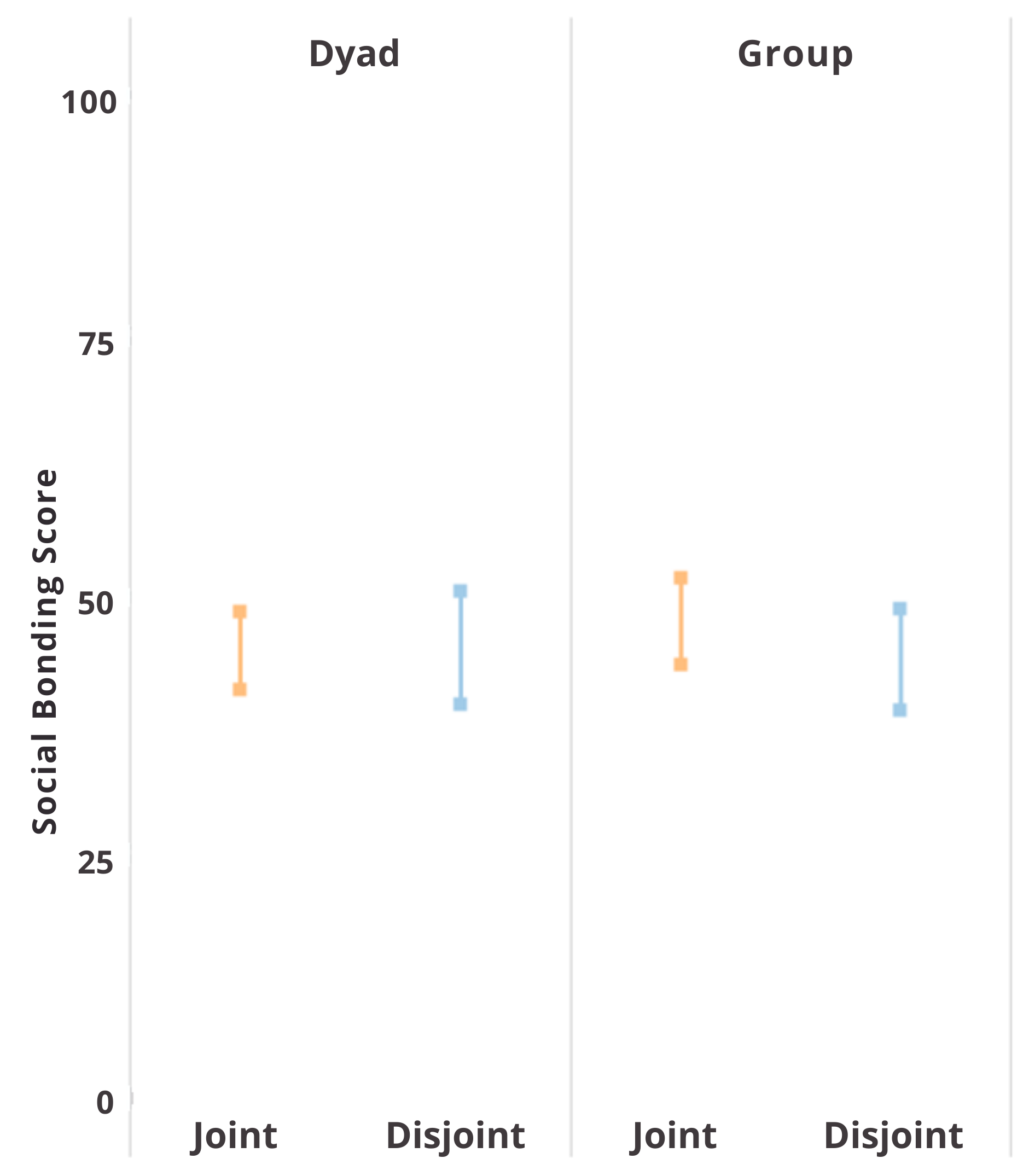

We then also looked if our parameter estimates yielded a similar pattern, by looking at the 95% Bayesian High Density Intervals showing, in this case, the 95% most likely values of the mean social bonding score for each cell in the 2 by 2. We found highly overlapping 95% HDI’s for the participants who engaged in a dyadic interaction in the joint attention condition, estimated M = 45.91, 95% HPI = [42.62, 49.20], and in the disjoint attention condition, estimated M = 46.58, 95% HPI = [42.29, 50.86], as well as for participants who engaged in a group interaction in the joint attention condition, estimated M = 44.89, 95% HPI = [41.70, 48.09], and in the disjoint attention condition, estimated M = 43.04, 95% HPI = [38.42, 47.66]. See Figure 2 for a graphical representation of the 95% HDI’s per cell.

Figure 2. Bayesian High Density Intervals Containing the 95% Most Likely Social Bonding Scores

for the Joint Attention and Disjoint Attention Groups per Group Size.

To further corroborate the absence of the effect of the attention manipulation, we conducted Bayesian independent samples t-tests of equivalence. In equivalence tests, like in regular Bayesian t-tests, the posterior distribution of the difference score between two groups is estimated. However, instead of looking at the 5% most extreme values of the difference score at the tails of the distribution to infer non-equivalence, equivalence tests look at the 5% most extreme values centered around zero, creating a region of practical equivalence. This helps to distinguish null-effects caused by high uncertainty in parameter estimation (e.g., due to low power) from null-effects that actually reflect practical equivalence between two groups. This equivalence model (i.e., the mean difference falls within the region of practical equivalence) is then compared to a non-equivalence model (i.e., the mean difference falls outside of the region of practical equivalence) in terms of their relative likelihood, using a Bayes Factor, which indicates the odds ratio in favor of the equivalence model or the non-equivalence model.

A Bayesian equivalence test comparing the difference between the joint attention and disjoint attention condition in the full sample showed moderate evidence (van Doorn et al., 2020) for the two conditions being practically equivalent (BF = 5.28). We also conducted separate equivalence tests for the participants who interacted in a dyad and participants who interacted in a group. The equivalence test for the participants who engaged in a dyadic interaction showed moderate support for the social bonding scores in the joint attention and disjoint attention condition being practically equivalent (BF = 3.98). In addition, the equivalence test for the participants who engaged in a group interaction showed moderate support for the two groups being practically equivalent

(BF = 3.38). Overall, these findings suggest that the current attention manipulation had no effect on the participants’ social bonding scores.

Politeness and Attractiveness

Two 2 x 2 between subjects Bayesian GLM’s with condition and group size as independent variables and the politeness as dependent variable showed no main effects or interactions (i.e., the Null model was the most likely model) of the joint versus disjoint attention condition or the dyad versus group setting in the degree to which participants felt the confederates were behaving in an impolite manner or the degree to which the participants felt the confederates were attractive (see supplementary materials, Table A1 and A2 for model summaries). In addition, practical equivalence tests showed moderate support for participants in the two conditions reporting practically equivalent levels of politeness (BF = 4.08) and attractiveness (BF = 5.09) As the perceived impoliteness and attractiveness of the confederates was similar between conditions, it is unlikely that these factors meaningfully influenced the current results.

Watching Experience

As the questions on how much participants liked watching the video and how much they enjoyed watching the video were conceptually very similar and highly correlated, Bayesian estimation of correlation coefficient r = .93, 95% HDI = [.90, .95], we collapsed them into a single viewing enjoyment measure (skewness = −0.75, kurtosis = 0.43). Although a 2 x 2 between subjects Bayesian GLM with condition and group size as independent variables and viewing enjoyment as dependent variable did show that a model with the joint attention condition as a predictor was the most likely model and more likely than a null model without predictors (BF = 1.42), this evidence is considered anecdotal and no strong conclusions can be drawn from these results (See supplementary Table A3 for model summaries).

Furthermore, we found no difference between conditions in the extent to which participants liked the video (skewness = −0.87, kurtosis = −0.88; see supplementary Table A4 for model summaries), although in this case the practical equivalence test provided only marginal evidence for participants in the two conditions liking the conditions equally (BF = 1.59). The extent to which participants were willing to watch a similar video by themselves again (skewness = 0.19, kurtosis = −1.15; see supplementary Table A5 for model summaries) provided a clearer picture, with equivalence tests providing moderate support for this willingness to be practically equivalent across the 2 conditions (BF = 4.03).

Discussion

The current results show no social bonding effect of sharing attention through online video-mediated social interactions. Crucially, Bayesian equivalence tests provided evidence for the social bonding scores to be practically equivalent between the joint attention and disjoint condition within and across group sizes. Thus, our results are in stark contrast with (1) research showing social bonding through shared experiences in online video mediated interactions during which participants explicitly communicate (Dabbish, 2008; Depping & Mandryk, 2017; Furukawa et al., 2017; Furukawa & Driessnack, 2012; Mahaphanit & Chang, 2023; Zheng et al., 2002), and (2) research showing social bonding through shared experiences in studies using real life social interactions during which participants are not allowed to communicate (Haj-Mohamadi et al., 2018; Rennung & Göritz, 2015; Wolf & Tomasello, 2019, 2020b, 2020a; Wolf et al., 2015).

Importantly, the study design, instructions, stimulus materials, and dependent measures were very similar/identical to several of these in-person studies (Rennung & Göritz, 2015; Wolf & Tomasello, 2020b, 2020a) and the current sample only included participants who had correctly reported what their partners’ instructions were and if their partners followed these instructions, suggesting participants in the joint attention condition were aware that (1) their partners had been instructed to attend to the video and (2) their partners looked at the screen during the procedure. Moreover, the social interaction in the current procedure was highly similar to those in virtual classrooms or workplaces in which participants jointly attend to a video or lecture, while the study sample should, based on their demographics, be highly familiar with these kinds of virtual environments. Thus, it seems unlikely that the current results are due to issues with the methodology or ecological validity. Instead, the data suggest that although in-person interactions might provide sufficient implicit social information to bond through shared experiences without the need for explicit communication, this might not be the case in video-mediated social interactions.

For example, the fact that participants were not able to see their partners’ screens in the current study (compared to previous in-person studies) might have made it more difficult for participants to infer whether their partners were actually looking at the same stimulus (i.e., perhaps they are multitasking and have other windows open on their screen). Although explicit communication about the stimulus might have solved this problem (as successfully communicating about a stimulus is only possible if one is attending to it), in the absence of explicit communication, this uncertainty might have eroded the social bonding properties in this online video mediated setting.

In addition, the video stream of participants in a shared screen interface on Zoom (or many other video communication platforms) is likely too small to accurately assess the gaze direction of participants, making it difficult for participants to judge whether their partners were looking at them or at the video, something that is much easier to infer during triadic engagements in in-person settings. A related, albeit slightly different issue is that, in contrast to participants in previous in-person studies, it was impossible for participants in the current study to make direct eye contact with their partners simply because their camera and the location at which their partners’ eyes were being displayed were in different places. Although eye contact is not a prerequisite for creating social closeness in triadic interactions per se (Wolf & Tomasello, 2019, 2020b; Wolf et al., 2015), it does play an important role in inferring the degree of cooperativeness between individuals (Cui et al., 2019; Kleinke, 1986; Siposova et al., 2018) and also contributes to the social closeness created specifically in joint attention interactions, at least in humans (Wolf & Tomasello, 2020a). Both of these issues cause more uncertainty for participants of online video mediated interactions about whether an experience is actually shared. It is therefore plausible that these added sources of uncertainty help explain why social bonding through video mediated communication without explicit communication is more difficult than during in-person interactions.

One set of social signals we so far have not considered but might play a role in online social bonding is the emotional expressions people display in reaction to the stimuli. In the current confederate videos the actors were asked to remain emotionally neutral. However, in real world video mediated interactions partners’ emotional expressions that are temporally aligned with one’s own experience (e.g., they laugh when you see something funny happen on the screen) might also function as a social cue that indicates that this interaction partner is going through a similar experience (Cheong et al., 2023; Liszkowski et al., 2007). This might at least mitigate some of the uncertainty inherent to non-communicative online interactions and thus also make it more likely for some social bonding to occur. However, emotional expressions do not provide information about whether individuals are mutually aware that their experience is shared, still leaving participants of online non-communicative exchanges with uncertainty in this (arguably crucial) dimension of bonding through shared experiences.

These results thus raise important considerations when deciding to exchange in-person gatherings such as school classes, lectures and work meetings for more convenient virtual alternatives. Unless communicative or proactive social engagement is facilitated and encouraged, increased convenience perhaps comes at a social cost people might not always be aware of: Students or colleagues might lose their sense of connection with their peers and with the community as a whole, potentially increasing loneliness and reducing wellbeing.

From a developmental perspective, these social costs might be particularly impactful for younger children for whom in-person classrooms are replaced by virtual ones. Early childhood marks the time during which children start to regularly interact with novel peers in school or kindergarten, allowing them to learn how to effectively develop social relationships. If their in-person educational experience is replaced by online video-mediated interactions without sufficient active social engagement, they might not only struggle creating social connections with others in that moment, but also be deprived of opportunities to learn how to connect with their peers through shared experiences, potentially interfering with their long-term social development.

One thing to note here is that the current results were found in participants who (1) indicated that they were paying attention to the manipulation, (2) passed the instructional manipulation check, and (3) correctly answered the comprehension questions. Yet there were another 61 participants who were excluded because they did not meet these criteria. This is not surprising, given that these types of virtual interactions have been shown to reduce information processing and recall in online settings relative to in-person settings (De Felice et al., 2021). However, this does mean that a substantial number of participants did not seem to process the social information presented in the procedure at all (or at least not enough to pass the manipulation checks), meaning that the social costs of moving interactions into digital environments without making them more socially engaging might be even higher than the data based on the current included sample suggests.

Importantly, the results of the current study do not imply that social bonding by sharing experiences virtually in general, or through video mediated interactions specifically, is impossible, nor that we should stay away from doing so. However, the current results imply that if one attempts to substitute in-person shared experiences with online video mediated shared experiences, one should be aware that in video mediated shared experiences a lack of active social engagement (e.g., through a chat function or by creating Virtual Reality avatars) might render the experience less (or perhaps not at all) effective for social bonding purposes, whereas this is less problematic for in-person shared experiences.

As such, on a fundamental level, the contrast between the data of our current online study and previous research on social bonding during in-person non-communicative shared experiences suggests that the contextual flexibility of one of our most basic social bonding capacities, the capacity to create social closeness by sharing experiences through shared representations, is, in fact, more limited than previously thought. Importantly, these limitations, specifically in the context of modern day virtual social environments, might have serious implications for the social relationships and social networks of individuals using this medium as a social interaction, as well as for the overall social cohesiveness in communities and societies where these types of technologies are currently used on a regular basis.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Use of AI Services

The authors declare they have not used generative AI to generate any part of the manuscript.

Appendix

Table A1. Model Comparison Parameters for Politeness Models.

|

Models |

P(M) |

P(M|data) |

BF10 |

|

Null model |

.20 |

.68 |

1.00 |

|

Attention |

.20 |

.17 |

0.24 |

|

Group size |

.20 |

.12 |

0.18 |

|

Attention + Group size |

.20 |

.03 |

0.04 |

|

Attention + Group size + Attention * Group size |

.20 |

.01 |

0.01 |

|

Note. In column BF10 each model is compared to the best model. |

|||

Table A2. Model Comparison Parameters for Attractiveness Models.

|

Models |

P(M) |

P(M|data) |

BF10 |

|

Null model |

.20 |

.66 |

1.00 |

|

Attention |

.20 |

.17 |

0.26 |

|

Group size |

.20 |

.13 |

0.19 |

|

Attention + Group size |

.20 |

.03 |

0.05 |

|

Attention + Group size + Attention * Group size |

.20 |

.01 |

0.01 |

|

Note. In column BF10 each model is compared to the best model. |

|||

Table A3. Model Comparison Parameters for Viewing Enjoyment Models.

|

Models |

P(M) |

P(M|data) |

BF10 |

|

Null model |

.20 |

.43 |

1.00 |

|

Attention |

.20 |

.30 |

0.70 |

|

Group size |

.20 |

.14 |

0.33 |

|

Attention + Group size |

.20 |

.10 |

0.23 |

|

Attention + Group size + Attention * Group size |

.20 |

.03 |

0.08 |

|

Note. In column BF10 each model is compared to the best model. |

|||

Table A4. Model Comparison Parameters for Video Liking Models.

|

Models |

P(M) |

P(M|data) |

BF10 |

|

Null model |

.20 |

.43 |

1.00 |

|

Attention |

.20 |

.30 |

0.65 |

|

Group size |

.20 |

.14 |

0.22 |

|

Attention + Group size |

.20 |

.10 |

0.13 |

|

Attention + Group size + Attention * Group size |

.20 |

.03 |

0.03 |

|

Note. In column BF10 each model is compared to the best model. |

|||

Table A5. Model Comparison Parameters for Watching Video Again Models.

|

Models |

P(M) |

P(M|data) |

BF10 |

|

Null model |

.20 |

.49 |

1.00 |

|

Attention |

.20 |

.32 |

0.65 |

|

Group size |

.20 |

.11 |

0.22 |

|

Attention + Group size |

.20 |

.07 |

0.14 |

|

Attention + Group size + Attention * Group size |

.20 |

.02 |

0.03 |

|

Note. In column BF10 each model is compared to the best model. |

|||

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2025 Wouter Wolf, Kayley Dotson