Longitudinal bidirectional relations between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction: The roles of problematic social network use and personality

Vol.19,No.3(2025)

Parental phubbing, as a new negative factor for adolescents’ healthy and positive development, has been noticed by scholars. The current study explored the longitudinal association between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction across three years, taking into account adolescents’ problematic social network use as a potential mediator and Big Five personality traits as moderators of the associations. This study involved 2,407 Chinese adolescents (Mage = 12.75, SD = 0.58 at baseline, range = 11–16) by questionnaire. The involved students were recruited from 48 classrooms across 7 different schools. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to fit our cross‐lagged panel model across three waves of data. The results showed that the relation between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction is negative and bidirectional. Problematic social network use mediated the relation between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Agreeableness moderated the relations among parental phubbing, problematic social network use, and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Specifically, the negative bidirectional relations between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction were more robust for adolescents with low agreeableness than those with high agreeableness. Compared to adolescents with low agreeableness, adolescents who with high agreeableness experienced high parental phubbing at previous time points were more likely to have problematic social network use at subsequent time points. The present study indicates that perceived high parental phubbing can be both a precursor to and an outcome of adolescents’ low life satisfaction, serving to maintain a vicious cycle that compounds negative effects on student mental health. Further, results demonstrate how problematic social network use and personality can affect this cycle.

parental phubbing; life satisfaction; problematic social network use; Big Five personality; adolescents

Xiaoyan Zhou

Department of General Education and Research, Zhengzhou Police University, Zhengzhou, China

Xiaoyan Zhou is a lecturer in the Department of General Education and Research, Zhengzhou Police University, China. Her research interests are linguistic psychology, students’ mental health, and English language teaching.

Fangfang Tian

School of Educational Science, Shanxi University, Taiyuan, China

Fangfang Tian is a postgraduate student in the School of Educational Science, Shanxi University, China. Her research interests are in adolescents’ bullying, moral disengagement, and parental phubbing.

Xingchao Wang

School of Educational Science, Shanxi University, Taiyuan, China

Xingchao Wang is a professor in the School of Educational Science, Shanxi University, China. His research interests are in adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration, aggression, bullying, moral disengagement, parental phubbing, and partner phubbing.

Xinyi Chen

School of Economics and Management, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

Xinyi Chen is an undergraduate student in the School of Economics and Management, Tongji University, China. Her research interests are in adolescents’ life satisfaction, neural mechanisms, and treatment of anxiety/autism.

Jiping Yang

School of Educational Science, Shanxi University, China

Jiping Yang is a professor in the School of Educational Science, Shanxi University, China. He is a member of the Chinese Psychological Association and the president of the Shanxi Psychological Association. His research interests are in educational psychology, human resource management, adolescents’ aggression, cyberbullying perpetration, bullying, and moral disengagement.

Xueqi Zeng

School of Psychology and Cognitive Science, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China

Xueqi Zeng is a doctoral student in the School of Psychology and Cognitive Science, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China. Her research focuses on parental phubbing, aggression, and defending among Chinese adolescents. She wants to promote happiness among adolescents for family reasons.

Albuquerque, I., de Lima, M. P., Matos, M., & Figueiredo, C. (2013). The interplay among levels of personality: The mediator effect of personal projects between the Big Five and subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(1), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9326-6

Berg, A. I., Hassing, L. B., Thorvaldsson, V., & Johansson, B. (2011). Personality and personal control make a difference for life satisfaction in the oldest-old: Findings in a longitudinal population-based study of individuals 80 and older. European Journal of Ageing, 8(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-011-0181-9

Bi, X., & Wang, S. (2021). Parent-adolescent communication quality and life satisfaction: The mediating roles of autonomy and future orientation. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.S317389

Blau, I., Goldberg, S., & Benolol, N. (2019). Purpose and life satisfaction during adolescence: The role of meaning in life, social support, and problematic digital use. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(7), 907–925. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2018.1551614

Boer, M., Van Den Eijnden, R. J., Boniel-Nissim, M., Wong, S. L., Inchley, J. C., Badura, P., Craig, W. M., Gobina, I., Kleszczewska, D., Klanšček, H. J., & Stevens, G. W. (2020). Adolescents’ intense and problematic social media use and their well-being in 29 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), S89–S99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.014

Carson, V., & Kuzik, N. (2021). The association between parent-child technology interference and cognitive and social-emotional development in preschool‐aged children. Child: Care, Health and Development, 47(4), 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12859

Carver, C. S., & Connor-Smith, J. (2010). Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(1), 679–704. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352

Cha, H. S., & Yang, S. J. (2020). The longitudinal mediating effects of perceived parental neglect on changes in Korean adolescents’ life satisfaction by gender. Asian Nursing Research, 14(5), 286–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2020.08.006

Chang, E. C., Yang, H., & Yu, T. (2017). Perceived interpersonal sources of life satisfaction in Chinese and American students: Cultural or gender differences? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(4), 414–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1198925

Chen, A. (2019). From attachment to addiction: The mediating role of need satisfaction on social networking sites. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.034

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

China Internet Network Information Center. (2023). The 51st statistic report of China internet network development. https://www.cnnic.com.cn/IDR/ReportDownloads/202307/P020230707514088128694.pdf

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 193–196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01259

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., Dvorak, R. D., & Hall, B. J. (2016). Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.079

Elphinston, R. A., & Noller, P. (2011). Time to face it! Facebook intrusion and the implications for romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(11), 631–635. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0318

Fayers, P. M., & King, M. T. (2009). How to guarantee finding a statistically significant difference: The use and abuse of subgroup analyses. Quality of Life Research, 18(5), 527–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9473-3

Feldman, R. S. (2008). Discovering the lifespan. Prentice Hall.

Frackowiak, M., Hilpert, P., & Russell, P. S. (2024). Impact of partner phubbing on negative emotions: A daily diary study of mitigating factors. Current Psychology, 43(2), 1835–1854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04401-x

Gilman, R., & Huebner, S. (2003). A review of life satisfaction research with children and adolescents. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(2), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.18.2.192.21858

Goldbeck, L., Schmitz, T. G., Besier, T., Herschbach, P., & Henrich, G. (2007). Life satisfaction decreases during adolescence. Quality of Life Research, 16(6), 969–979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9205-5

Gross, E. F., Juvonen, J., & Gable, S. L. (2002). Internet use and well-being in adolescence. Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00249

Hancock, G. R., & Mueller, R. O. (2010). The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences. Routledge.

Heidemeier, H., & Göritz, A. S. (2016). The instrumental role of personality traits: Using mixture structural equation modeling to investigate individual differences in the relationships between the Big Five traits and life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(6), 2595–2612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9708-7

Holland, A. S., & Roisman, G. I. (2008). Big Five personality traits and relationship quality: Self-reported, observational, and physiological evidence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(5), 811–829. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407508096697

Huebner, E. S. (2004). Research on assessment of life satisfaction of children and adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 66(1), 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SOCI.0000007497.57754.e3

Irfan, M., & Ahmad, M. (2022). Modeling consumers’ information acquisition and 5G technology utilization: Is personality relevant? Personality and Individual Differences, 188, Article 111450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111450

Jovanović, V. (2019). Adolescent life satisfaction: The role of negative life events and the Big Five personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, Article 109548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109548

Kai, D., Yanyu, L., Linxin, W., & Yangang, N. (2023). Fear of missing out or social avoidance? The relationship between peer exclusion and problematic social media use among adolescents. Journal of Psychological Science, 46(5), 1081–1089. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20230507

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications.

Larson, R. W., & Almeida, D. M. (1999). Emotional transmission in the daily lives of families: A new paradigm for studying family process. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/353879

Lay, C., Fairlie, P., Jackson, S., Ricci, T., Eisenberg, J., Sato, T., Teeaar, A., & Melamud, A. (1998). Domain-specific allocentrism-idiocentrism: A measure of family connectedness. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29(3), 434–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022198293004

Lerner, R. M., Johnson, S. K., & Buckingham, M. H. (2015). Relational developmental systems‐based theories and the study of children and families: Lerner and Spanier (1978) revisited. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 7(2), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12067

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

Liu, K., Chen, W., Wang, H., Geng, J., & Lei, L. (2021). Parental phubbing linking to adolescent life satisfaction: The mediating role of relationship satisfaction and the moderating role of attachment styles. Child: Care, Health and Development, 47(2), 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12839

Longstreet, P., & Brooks, S. (2017). Life satisfaction: A key to managing internet & social media addiction. Technology in Society, 50, 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2017.05.003

Millikan, E., Wamboldt, M. Z., & Bihun, J. T. (2002). Perceptions of the family, personality characteristics, and adolescent internalizing symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(12), 1486–1494. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200212000-00021

Moreno-Maldonado, C., Jimenez-Iglesias, A., Camacho, I., Rivera, F., Moreno, C., & Matos, M. G. (2020). Factors associated with life satisfaction of adolescents living with employed and unemployed parents in Spain and Portugal: A person focused approach. Children and Youth Services Review, 110, Article 104740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104740

Müller, K. W., Dreier, M., Beutel, M. E., Duven, E., Giralt, S., & Wölfling, K. (2016). A hidden type of internet addiction? Intense and addictive use of social networking sites in adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 172–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.007

Naidu, S., Chand, A., Pandaram, A., & Patel, A. (2023). Problematic internet and social network site use in young adults: The role of emotional intelligence and fear of negative evaluation. Personality and Individual Differences, 200, Article 111915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111915

Noller, P., & Callan, V. (2015). The adolescent in the family. Routledge.

Noom, M. J., Deković, M., & Meeus, W. (2001). Conceptual analysis and measurement of adolescent autonomy. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30(5), 577–595. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010400721676

Oberst, U., Wegmann, E., Stodt, B., Brand, M., & Chamarro, A. (2017). Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: The mediating role of fear of missing out. Journal of Adolescence, 55(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.008

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 3–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701756946

Peter, J., Valkenburg, P. M., & Schouten, A. P. (2005). Developing a model of adolescent friendship formation on the internet. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 8(5), 423–430. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2005.8.423

Piko, B. F., & Hamvai, C. (2010). Parent, school and peer-related correlates of adolescents’ life satisfaction. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(10), 1479–1482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.07.007

Proctor, C. L., Linley, P. A., & Maltby, J. (2009). Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(5), 583–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9110-9

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

Shin, D. C., & Johnson, D. M. (1978). Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 5(1–4), 475–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00352944

Stockdale, L. A., Coyne, S. M., & Padilla-Walker, L. M. (2018). Parent and child technoference and socioemotional behavioral outcomes: A nationally representative study of 10-to 20-year-old adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 88, 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.06.034

Suldo, S. M., & Huebner, E. S. (2006). Is extremely high life satisfaction during adolescence advantageous? Social Indicators Research, 78(2), 179–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-8208-2

Suldo, S. M., R Minch, D., & Hearon, B. V. (2015). Adolescent life satisfaction and personality characteristics: Investigating relationships using a five factor model. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(4), 965–983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9544-1

Sun, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2021). A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addictive Behaviors, 114, Article 106699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106699

Tanksale, D. (2015). Big Five personality traits: Are they really important for the subjective well‐being of Indians? International Journal of Psychology, 50(1), 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12060

Tarafdar, M., Maier, C., Laumer, S., & Weitzel, T. (2020). Explaining the link between technostress and technology addiction for social networking sites: A study of distraction as a coping behavior. Information Systems Journal, 30(1), 96–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12253

Tomczyk, Ł., & Lizde, E. S. (2022). Nomophobia and phubbing: Wellbeing and new media education in the family among adolescents in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Children and Youth Services Review, 137, Article 106489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106489

Turel, O., Serenko, A., & Giles, P. (2011). Integrating technology addiction and use: An empirical investigation of online auction users. MIS Quarterly, 35(4), 1043–1061. https://doi.org/10.2307/41409972

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2007). Preadolescents’ and adolescents’ online communication and their closeness to friends. Developmental Psychology, 43(2), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.267

Wang, C., Lee, M. K. O., & Hua, Z. (2015). A theory of social media dependence: Evidence from microblog users. Decision Support Systems, 69, 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2014.11.002

Wang, H., & Lei, L. (2022). The relationship between parental phubbing and short‐form videos addiction among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 32(4), 1580–1591. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12744

Wang, J. M., Hartl, A. C., Laursen, B., & Rubin, K. H. (2017). The high costs of low agreeableness: Low agreeableness exacerbates interpersonal consequences of rejection sensitivity in U.S. and Chinese adolescents. Journal of Research in Personality, 67, 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.02.005

Wang, P., Mao, N., Liu, C., Geng, J., Wei, X., Wang, W., Zeng, P., & Li, B. (2022). Gender differences in the relationships between parental phubbing and adolescents’ depressive symptoms: The mediating role of parent-adolescent communication. Journal of Affective Disorders, 302, 194–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.073

Wang, P., Wang, X., Wu, Y., Xie, X., Wang, X., Zhao, F., Ouyang, M., & Lei, L. (2018). Social networking sites addiction and adolescent depression: A moderated mediation model of rumination and self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 127, 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.02.008

Wang, X., & Qiao, Y. (2022). Parental phubbing, self-esteem, and suicidal ideation among Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal mediational analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(11), 2248–2260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01655-9

Wang, X., Gao, L., Yang, J., Zhao, F., & Wang, P. (2020). Parental phubbing and adolescents’ depressive symptoms: Self-esteem and perceived social support as moderators. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(2), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01185-x

Weber, M., & Huebner, E. S. (2015). Early adolescents’ personality and life satisfaction: A closer look at global VS. domain-specific satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.042

Wegmann, E., & Brand, M. (2019). A narrative overview about psychosocial characteristics as risk factors of a problematic social networks use. Current Addiction Reports, 6(4), 402–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00286-8

Wurst, C., Smarkola, C., & Gaffney, M. A. (2008). Ubiquitous laptop usage in higher education: Effects on student achievement, student satisfaction, and constructivist measures in honors and traditional classrooms. Computers & Education, 51(4), 1766–1783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.05.006

Xie, X., Chen, W., Zhu, X., & He, D. (2019). Parents’ phubbing increases adolescents’ mobile phone addiction: Roles of parent-child attachment, deviant peers, and gender. Children and Youth Services Review, 105, Article 104426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104426

Yap, S. C., Anusic, I., & Lucas, R. E. (2012). Does personality moderate reaction and adaptation to major life events? Evidence from the British household panel survey. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(5), 477–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.05.005

Yerby, J. (1995). Family systems theory reconsidered: Integrating social construction theory and dialectical process. Communication Theory, 5(4), 339–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.1995.tb00114.x

Yu, L., & Shek, D. T. L. (2018). Testing longitudinal relationships between internet addiction and well-being in Hong Kong adolescents: Cross-lagged analyses based on three waves of data. Child Indicators Research, 11(5), 1545–1562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-017-9494-3

Zhou, H., Niu, L., & Zou, H. (2000). A development study on five-factor personality questionnaire for middle school students. Psychological Development and Education, 16(1), 48–54. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2000.01.009

Zhou, Y., Li, D., Jia, J., Li, X., Zhao, L., Sun, W., & Wang, Y. (2017a). Interparental conflict and adolescent internet addiction: The mediating role of emotional insecurity and the moderating role of Big Five personality traits. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 470–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.012

Zhou, Y., Li, D., Li, X., Wang, Y., & Zhao, L. (2017b). Big Five personality and adolescent internet addiction: The mediating role of coping style. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.009

Zhu, X., & Shek, D. T. L. (2020). The influence of adolescent problem behaviors on life satisfaction: Parent-child subsystem qualities as mediators. Child Indicators Research, 13(5), 1767–1789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09719-7

Zou, S., & Wu, X. (2020). Coparenting conflict behavior, parent–adolescent attachment, and social competence with peers: An investigation of developmental differences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(1), 267–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01131-x

Authors’ Contribution

Xiaoyan Zhou: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—original draft. Fangfang Tian: formal analysis, writing—review & editing, visualization. Xingchao Wang: funding acquisition, writing—review & editing. Xinyi Chen: data collection, data curation. Jiping Yang: data collection, data curation. Xueqi Zeng: conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

June 7, 2024

Revision received:

April 11, 2025

Accepted for publication:

June 3, 2025

Editor in charge:

Maèva Flayelle

Introduction

Smartphones have become integrated into people’s daily lives, allowing the internet to interfere with real-world interactions. The number of people in China who use the internet through smartphones has reached 1.065 billion, accounting for 99.8% of the total Chinese internet users, and the average person spends 26.7 hours online per week in China (CNNIC, 2023). Smartphones bring convenience to modern life but also cause many problems. For example, in the interference of electronic devices in the process of parent-child interaction, smartphones cause approximately 60% (Carson & Kuzik, 2021). Smartphones, inevitably, have also been embedded in adolescents’ growing environment (Tomczyk & Lizde, 2022). Therefore, it is worth paying attention to the influence of parental phubbing on adolescents. Parental phubbing is defined as the extent to which parents use or are distracted by their smartphones when they interact with their children (X. Wang et al., 2020). It has many negative effects on adolescents, such as the increased risk of anxiety, depression, and suicide ideation (Stockdale et al., 2018; X. Wang & Qiao, 2022; P. Wang et al., 2022;). Therefore, parental phubbing as a risk factor for the healthy growth of adolescents is worthy of in-depth study.

Life satisfaction is considered a hallmark of mental and physical health and resilience in adolescence (Gilman & Huebner, 2003). It is also an important factor affecting the quality of life and healthy development of adolescents. However, adolescents’ life satisfaction itself shows a downward trend (Goldbeck et al., 2007). Given the important function of life satisfaction, it is crucial to figure out what further contributes to the decline in adolescents’ life satisfaction. Adolescents’ life satisfaction is influenced by family factors (Blau et al., 2019). As a new family factor, parental phubbing’s relation with adolescents’ life satisfaction has not been studied in a longitudinal study. Therefore, the first purpose of this study was to explore whether there were reciprocal relations between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction.

Smartphones make it easier for adolescents to access social networking sites. This convenience also makes the problems of problematic social network use emerge among adolescents (Müller et al., 2016). Researchers have noticed that parental phubbing leads to adolescents’ mobile phone addiction and short-form videos addiction (H. Wang & Lei, 2022; Xie et al., 2019). However, it’s unclear whether parental phubbing would lead to adolescents’ problematic social network use. Thus, the current study used a cross-lagged design to examine whether parental phubbing would be a risk factor for adolescents’ problematic social network use and life satisfaction, and sought to explore whether the Big Five personality would be play a moderating role in these relations.

Parental Phubbing and Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction refers to “a distinct construct representing a cognitive and global evaluation of the quality of one’s life as a whole” (Pavot & Diener, 2008). According to family systems theory, individuals can not be understood in isolation from one another but rather as a part of their family, as the family is an emotional unit (Cox & Paley, 2003; Yerby, 1995). Family members influence each other and family is central to adolescents’ health and well-being (Larson & Almeida, 1999; Noller & Callan, 2015). From this, parents are important factors influencing adolescents’ life satisfaction (Piko & Hamvai, 2010). Adolescents with high parental phubbing are more likely to feel neglected or even rejected by their parents (X. Wang et al., 2020). Thus, parental phubbing may be related to adolescents’ life satisfaction. Studies showed that individuals who perceived phubbing are more likely to have a highly negative emotional state (Frackowiak et al., 2024). Perceived parental neglect influenced children’s life satisfaction (Cha & Yang, 2020). The negative effect of parental phubbing on adolescents’ life satisfaction has been examined in one study (Liu et al., 2021). However, Liu et al.’s (2021) study has two flaws. First, the relatively small sample size (n = 303) would lead to results with limited statistical power to detect the possible mediating and moderating effects (Fayers & King, 2009). Second, the cross-sectional design raised the concern of shared method variance. Thus, it is necessary to explore the relation between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction through a longitudinal study with a large sample.

Adolescents have characteristics that they are trying to shift the focus of their lives and emotional dependence outside of the family (Noller & Callan, 2015). During adolescence, adolescents’ bonds with their parents become vulnerable (Zou & Wu, 2020). Even so, adolescents’ life satisfaction is still undoubtedly impacted by parents (Moreno-Maldonado et al., 2020). Negative interactions with parents decrease adolescents’ assessments of their own quality of life (Bi & Wang, 2021; Zhu & Shek, 2020). Furthermore, for Chinese adolescents, who grew up in collectivism, family is an essential core (Lay et al., 1998; Oyserman et al., 2002). Compared with adolescents with individualism, adolescents with collectivism get less push to form autonomy and have a stronger connection with their parents (Feldman, 2008). Chinese adolescents attach more importance to their parents’ attitudes towards them and their relationships with their parents. Thus, for Chinese adolescents, the negative impact of parental phubbing on life satisfaction may be more pronounced. Based on these characteristics, it is necessary to study the influence of parental phubbing on life satisfaction among Chinese adolescents.

The cognitions and evaluations of parental phubbing generally adopt a bottom-up approach. According to bottom-up models, people evaluate what they think is important based on their chosen criteria, which affect their life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1985; Shin & Johnson, 1978). For adolescents, factors related to parents are included as important criteria for assessing life satisfaction (Noller & Callan, 2015; Proctor et al., 2009). Therefore, based on this cognitive approach, the current study hypothesized that parental phubbing would affect adolescents’ life satisfaction. In addition, this study was curious whether another type of processing, top-down cognitive processing, would affect this relation. In other words, do adolescents’ different levels of life satisfaction affect their perception of parental phubbing? Family is central to the health and well-being of adolescents. Adolescents tend to maintain, as far as possible, close positive relationships with their parents and get their support and help (Noller & Callan, 2015). As a result, in accordance with the strong influence of parents on adolescents’ life satisfaction, adolescents may consciously or unconsciously attribute their life satisfaction to parents’ behavior, such as parental phubbing. Thus, adolescents with low life satisfaction are more likely to perceive high parental phubbing. Unfortunately, to our knowledge, there is no research that has explored how life satisfaction affects adolescents’ perceptions of parental phubbing. In summary, this study preliminarily explored the reciprocal relations between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction using a longitudinal study with a large sample.

Adolescents’ Problematic Social Network Use and Life Satisfaction

Social networking sites, being feature-rich information technology, can provide a high level of perceived usefulness and ease-of-use, afford users with various needs, and be framed differently in different use of contexts (A. Chen, 2019; Tarafdar et al., 2020). With the smartphone functionality continues to improve, the overuse of social networking sites by adolescents has exploded (Naidu et al., 2023). Meanwhile, the development of social networking sites also tends to induce fear of missing out among adolescents, which leads to problematic social network use (Elhai et al., 2016; Oberst et al., 2017). Specifically, adolescents may experience a form of diffuse anxiety that arises from the fear of missing out on novel experiences or exciting events for others (Przybylski et al., 2013). Compared with the time and distance constraints of offline face-to-face socializing, the convenience and immediacy of social media can better satisfy the psychological needs of adolescents with the fear of missing out, who are eager to continuously grasp other people's information. Therefore, adolescents are more likely to engage in frequent use of social networking sites, which raises the risk of problematic social network use (Kai et al., 2023). Problematic social network use serves as a maladaptive state of psychological dependence that seriously affects adolescents' psychological development (Turel et al., 2011; Wurst et al., 2008). However, it is unclear whether and to what extent problematic social network use affects adolescents’ life satisfaction. Studies have shown that internet addiction (as a superior concept of problematic social network use) and problematic social media use can both lead to low adolescents’ life satisfaction (Boer et al., 2020; Yu & Shek, 2018). Therefore, it is reasonable to think that problematic social network use may negatively affect adolescents’ life satisfaction.

Adolescents with low life satisfaction are more likely to have problematic social network use. According to social compensation theory, when the lack of life satisfaction is difficult to be supplemented in real life, adolescents are more likely to use social networking sites to improve their life satisfaction (Sun & Zhang, 2021). Adolescents can easily meet their needs through the ease-of-use of the internet, which leads them to choose social networking sites to make up for the lack of life satisfaction (C. Wang et al., 2015). Furthermore, when adolescents return to real life and once again experience a lack of life satisfaction, this negative reinforcement further increases the dependence on social networking sites, which increases the risk of problematic social network use (Wegmann & Brand, 2019). The relation between life satisfaction and problematic social network use has been explored in one study (Longstreet & Brooks, 2017). However, Longstreet and Brooks’ (2017) study did not focus on adolescents, and the cross-sectional study with a small sample size (n = 251) led to the poor stability, reliability, and validity of the results. Thus, the second purpose of this study examined the bidirectional relations between adolescents’ problematic social network use and life satisfaction using a cross-lagged model with a large sample.

The Mediating Role of Adolescents’ Problematic Social Network Use

Problematic social network use may underline the relation between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Parental phubbing makes adolescents feel their parents think that smartphones are more important than themselves. Persistent exposure to parental phubbing, adolescents are more likely to have a strong feeling of being ignored or even rejected (X. Wang et al., 2020). The social compensation theory states that unsatisfied needs would result in an overuse of social networking sites (Gross et al., 2002; Peter et al., 2005; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). In other words, adolescents with high parental phubbing are more likely to use social networking sites to build connections with others to compensate for their unsatisfied needs. As a coping strategy to compensate for the absence of need, compensatory internet use can lead to overuse of the internet (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). In this way, the risk of adolescents’ problematic social network use increases because of high parental phubbing. Thus, based on the above theoretical and empirical grounds, we believed that adolescents who perceive high parental phubbing are more likely to have problematic social network use. Combined with the previous view that problematic social network use leads adolescents to have low life satisfaction, the current study hypothesizes that problematic social network use may as a mediator role in the relation between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction. This is also one of the focuses of this study, as previous research has mostly focused on the negative impact of adolescents’ problematic mobile phone use on their own life satisfaction, such as internet addiction (Boer et al., 2020; Yu & Shek, 2018). This study emphasizes that the reason for adolescents’ low life satisfaction may be indirectly caused by parents’ inappropriate use of smartphones in the process of interacting with adolescents, such as parental phubbing.

Big Five Personality Traits as Moderators

In personality research, Big Five personality traits are an important approach widely agreed upon in explaining personality (Albuquerque et al., 2013). It includes five dimensions of personality: Extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, and neuroticism (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010). Personality explains 47% of the variance in adolescents’ life satisfaction (Suldo et al., 2015). Different personality traits affect an individual’s coping style and the way they deal with stressors (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010). Therefore, personality traits may moderate the influence of parental phubbing on problematic social network use, thereby indirectly influencing adolescents’ life satisfaction. Furthermore, all of the Big Five personality traits have been found to predict adolescents’ life satisfaction to varying degrees, but the effect has been inconsistent across studies (Heidemeier & Göritz, 2016; Proctor et al., 2009; Weber & Huebner, 2015). For example, some researchers find the strongest predictor of low life satisfaction is high neuroticism, but other researchers find the strongest predictor is conscientiousness (Suldo et al., 2015; Tanksale, 2015).

Individual-context relation theory describes that individual differences moderate the relationship between the individual and the context and form a whole that acts together on the entire development system (Lerner et al., 2015). Different Big Five personality affects individuals’ different perceptions of relationship quality (Holland & Roisman, 2008). For example, personalities affect adolescents’ perception of the family context, such as neuroticism adolescents are more likely to feel negative family context (Millikan et al., 2002). In addition, personalities moderate the relation between perception and behavior (Irfan & Ahmad, 2022). Specifically, neuroticism moderates the relation between older health conditions and life satisfaction (Berg et al., 2011). High neuroticism or high extraversion strengthens the influence of interparental conflict on adolescents’ internet addiction (Y. Zhou et al., 2017a). However, some studies did not support individual-context relation theory. Such as, the Big Five personality traits of Serbian adolescents did not show differences in the relation between negative events and life satisfaction (Jovanović, 2019). A British study that followed more than 30,000 people also did not show the moderating effects of Big Five personality traits on the relation between negative events and life satisfaction (Yap et al., 2012). Although these two studies have differences in sample groups and research methods, they both suggested that culture-specific may lead to the results that Big Five personality traits did not show moderating effects. Therefore, examining the effects of different Big Five personality traits is crucial in different cultural backgrounds such as China. To our knowledge, no study has examined whether Big Five personality traits would moderate the direct and indirect effects of parental phubbing on life satisfaction through problematic social network use among Chinese adolescents.

The Current Study

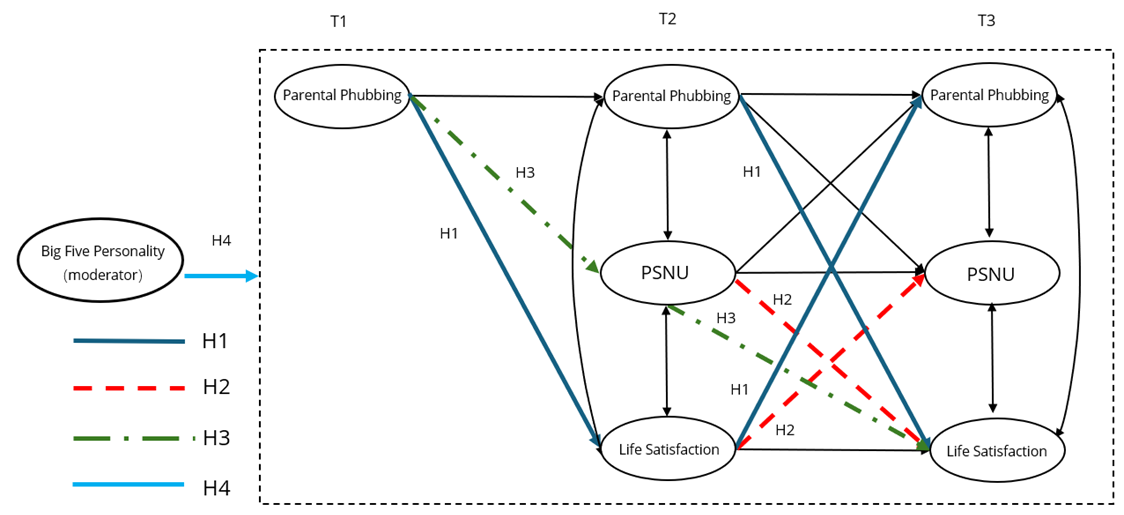

The current study examined the long-term reciprocal links between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Precisely, this research would determine four research questions. First, we tested the bidirectional relations between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Second, we tested the bidirectional relations between adolescents’ problematic social network use and life satisfaction. Third, we tested the mediating role of adolescents’ problematic social network use from parental phubbing to life satisfaction. Finally, we tested the moderating role of Big Five personality traits among the above relations. As discussed, we predicted that parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction were bidirectional relations over time (H1), problematic social network use and adolescents’ life satisfaction were bidirectional relations over time (H2), the mediating role of problematic social network use would exist (H3), and Big Five personality traits would moderate the relations among parental phubbing, problematic social network use, and adolescents’ life satisfaction (H4; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Proposed Conceptual Model.

Note. PSNU = Problematic Social Network Use.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Data for the study came from a project on adolescents’ mental health (X. Wang et al., 2020). The project was an annual longitudinal study that began in 2018 and involved students from seven middle schools in Taiyuan and Changzhi, China. Participants were from 48 classes with approximately 50–60 students in each class. Of these invitees, 2,821 adolescents took part in the project. Finally, after eliminating invalid questionnaires, data from 2,407 participants were used for analysis (Mage = 12.75 years, SD = 0.58; 1,191 boys, 1,202 girls, and 14 no reported gender).

In November 2019 (T1), 2407 adolescents completed the Parental Phubbing Scale, Five-factor Personality Inventory. A year later (T2), In late November 2019, 2,046 completed Parental Phubbing Scale, 1,953 completed the Social Networking Sites Intrusion Questionnaire, and 1,956 completed Satisfaction with Life Scale. In late November 2020 (T3), 1,862 completed Parental Phubbing Scale, 1,798 completed the Social Networking Sites Intrusion Questionnaire, and 1,802 completed Satisfaction with Life Scale. Reasons for attrition in the subsequent waves were illness or transferring to other schools and other personal reasons. We examined the differences between adolescents who joined the survey in at least two waves (n = 2,246) and those who dropped out at T2 and T3 (n = 161). There were no significant differences for T1 parental phubbing; Mdropout = 2.77, SDdropout = 0.90, Mstay = 2.71, SDstay = 0.83, t(2405) = 0.79, p = .433.

The University Ethics Committee approved this research of the first author’s institution. Before collecting data, adolescents received an explanation and introduction of the survey. Participants were informed that their participation in the survey was voluntary and their personal information would be kept private. At the same time, they were told that they could withdraw their participation at any time. After informed consent was obtained from participants, they filled out paper-pencil questionnaires in their classrooms.

Measures

Parental Phubbing

The 9-item Parental Phubbing Scale developed by X. Wang et al. (2020) was used to measure parental phubbing. Sample items include: My parents check their phone when they talk to me. Responses were rated on a five-point scale (1 = never to 5 = all the time). Higher scores indicated feeling more parental phubbing. This scale has been used in Chinese adolescents with good reliability and validity (X. Wang et al., 2020). Its Cronbach’s αs were .82, .84, and .87 at T1–T3, respectively. McDonald’s ωs were .82, .87, and .96 at T1–T3, respectively. The fit index values resulting from the confirmatory factor analysis of the scale revealed a good fit: T1: χ2(19) = 161.35, RMSEA = .056, 90% CI [.048, .064], CFI = .979, TLI = .959, SRMR = .024; T2: χ2(19) = 198.43, RMSEA = .068, 90% CI [.060, .077], CFI = .978, TLI = .958, SRMR = .027; T3: χ2(19) = 104.19, RMSEA = .049, 90% CI [.040, .058], CFI = .989, TLI = .978, SRMR = .021.

Life Satisfaction

The 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale developed by Diener et al. (1985) was used to measured adolescents’ global judgment of life satisfaction on the basis of their own criteria. Sample items include: My life is close to my idea in most respects. Responses were rated on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicated more satisfaction with life. It has been used in Chinese samples with good reliability and validity (Chang et al., 2017). The Cronbach’s αs (T2 = .80; T3 = .82) and the McDonald’s ωs (T2 = .80, T3 = .82) both had sufficient power to prove the internal consistency coefficients. The fit index values resulting from the confirmatory factor analysis of the scale revealed a good fit: T2: χ2(16) = 109.88, RMSEA =.058, 90% CI [.048, .069], CFI = .985, TLI = .974, SRMR = .025; T3: χ2(16) = 140.27, RMSEA = .067, 90% CI [.057, .078], CFI = .981, TLI = .967, SRMR = .026.

Problematic Social Network Use

Problematic social network use was measured by Social Networking Sites Intrusion Questionnaire. This Questionnaire was developed by P. Wang et al. (2018), based on the Facebook Intrusion Questionnaire (Elphinston & Noller, 2011). It included eight-item and was rated on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Sample items include: I often use social networking sites for no reason at all. Higher scores indicated a higher risk of problematic social network use. The Chinese version of the scale has been demonstrated to be a reliable and valid measurement (P. Wang et al., 2018). The Cronbach’s αs (T2 = .87; T3 = .89) and the McDonald’s ωs (T2 = .87, T3 = .88) both had sufficient power to prove the internal consistency coefficients. The fit index values resulting from the confirmatory factor analysis of the scale revealed a good fit: T2: χ2(3) = 18.68, RMSEA = .055, 90% CI [.033, .080], CFI = .995, TLI = .982, SRMR = .012; T3: χ2(3) = 15.63, RMSEA = .049, 90% CI [.027, .075], CFI = .996, TLI = .987, SRMR = .012.

Big Five Personality Traits

Adolescent personality was measured by the Chinese Big Five Personality Inventory (H. Zhou et al., 2000). The Questionnaire included 50 items assessing five personality dimensions and was rated on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Every dimension’s average score was calculated. Higher average scores indicated higher levels of personality dimension. The scale has been used in Chinese adolescents with good reliability and validity (Y. Zhou et al., 2017b). The Cronbach’s αs were .86 (neuroticism), .88 (agreeableness), .85 (conscientiousness), .80 (openness), .89 (extraversion), and the McDonald’s ωs were .86 (neuroticism), .88 (agreeableness), .85 (conscientiousness), .79 (openness), .89 (extraversion), respectively. The fit index values resulting from the confirmatory factor analysis of the scale revealed a good fit: Extraversion: χ2(43) = 397.54, RMSEA = .062, 90% CI [.057, .068], CFI = .962, TLI = .951, SRMR = .031. Conscientiousness: χ2(35) = 331.51, RMSEA = .063, 90% CI [.057, .069], CFI = .968, TLI = .958, SRMR = .026. Agreeableness: χ2(43) = 381.85, RMSEA = .061, 90% CI [.055, .066], CFI = .943, TLI = .928, SRMR = .037. Openness: χ2(27) = 224.63, RMSEA = .059, 90% CI [.052, .066], CFI = .976, TLI = .967, SRMR = .025. Neuroticism: χ2(27) = 248.71, RMSEA = .062, 90% CI [.055, .069], CFI = .968, TLI = .957, SRMR = .030.

Analytic Strategy

The current study used SPSS 28.0 and Mplus 8.3 software to analyze the data. The expectation-maximization (EM) estimation method was used for handling the missing data. Item-to-construct balance parceling method was used to improve the parsimony of the measurement and structural models (Little et al., 2002). Specifically, pairs of the highest and lowest items were assigned to different parcels in order to create relatively equivalent indicators. Means for parental phubbing, problematic social network use, life satisfaction, and Big Five personality represented mean-scaled scores, and these variables were estimated in the current study as latent variables.

Firstly, the current study used SPSS 28.0 for descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations analysis. Secondly, all other analyses were estimated using Mplus 8.3. This study examined the configural, metric, and scalar invariance of measurement invariance using equality constraints to ensure that the latent constructs had a comparable measurement structure across time. Since the χ2 is known to be sensitive to sample size and frequently yields statistically significant values (Kline, 2015), the current study not only adopted χ2/df to evaluate goodness-of-fit but also included the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker and Lewis Index (TLI), the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). In order to indicate that the fit between the models was equivalent, the changes of CFI and RMSEA in each constrained model were less than .010 and .015. Third, the measurement model and the cross-lagged model were evaluated. Fourth, the 95% bootstrap confidence interval of indirect effect was estimated by 1,000 bootstrap samples. In the final step, the multiple-group analysis allowed different parameters to estimate neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, and extraversion. The Wald test of parameter constraints was used to test for moderator variables. Additionally, in explaining the results of multiple-group analysis, scores above the mean were referred to high groups, and scores below the mean were referred to low groups.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Variables.

|

|

Range |

M |

SD |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

1. T1 Parental phubbing |

1–5 |

2.72 |

0.83 |

.43 |

−.19 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. T2 Parental phubbing |

1–5 |

2.82 |

0.97 |

.33 |

−.40 |

.48*** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. T2 PSNU |

1–7 |

2.94 |

1.28 |

.43 |

−.05 |

.15*** |

.25*** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. T2 Life satisfaction |

1–7 |

4.37 |

1.34 |

−.02 |

−.28 |

−.17*** |

−.18*** |

−.20*** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

5. T3 Parental phubbing |

1–5 |

2.82 |

0.84 |

.33 |

−.22 |

.39*** |

.48*** |

.18*** |

−.17*** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

6. T3 PSNU |

1–7 |

2.99 |

1.28 |

.35 |

−.12 |

.14*** |

.18*** |

.37*** |

−.11*** |

.30*** |

1 |

|

|

|

7. T3 Life satisfaction |

1–7 |

4.33 |

1.30 |

.05 |

−.17 |

−.13*** |

−.16*** |

−.18*** |

.45*** |

−.27*** |

−.15*** |

1 |

|

|

8. Extraversion |

1–5 |

3.73 |

0.81 |

−.34 |

−.13 |

−.12*** |

−.03 |

−.10*** |

.21*** |

−.04 |

−.09*** |

.13*** |

|

|

9. Agreeableness |

1–5 |

3.74 |

0.80 |

−.41 |

−.02 |

−.09*** |

−.01 |

−.07** |

.18*** |

−.02 |

−.08** |

.13*** |

|

|

10. Neuroticism |

1–5 |

3.71 |

.81 |

−.41 |

−.10 |

−.09*** |

−.001 |

−.07** |

.19*** |

−.03 |

−.08*** |

.14*** |

|

|

11. Conscientiousness |

1–5 |

3.70 |

.74 |

−.41 |

.42 |

−.06** |

.04 |

−.03 |

.14*** |

.01 |

−.05 |

.07** |

|

|

12. Openness |

1–5 |

3.36 |

.78 |

.08 |

−.10 |

.04 |

.11*** |

.11*** |

−.03 |

.08*** |

.07** |

−.08*** |

|

|

Note. PSNU = Problematic Social Network Use. **p < .01, ***p < .001. |

|

||||||||||||

Results

Descriptive Statistic

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics results and bivariate correlations about parental phubbing, problematic social network use, adolescents’ life satisfaction, and Big Five personality traits. All correlations were in the expected directions. The skewness and kurtosis of all variables were fell within the acceptable range (i.e., skewness < |2.0| and kurtosis < |7.0|; Hancock & Mueller, 2010).

The Latent Structural Model

As shown in Table 2, the values of ΔCFI and ΔTLI were less than .01, and the value of ΔRMSEA was less than .015 (F. F. Chen, 2007). The configure, metric, and scalar invariance of latent constructs were all established. Specifically, all variables’ configuration, factor loadings, and intercepts were kept equivalent over time. Therefore, the constraints for scalar invariance were retained for the subsequent analyses.

Table 2. The Measurement Invariance of The Scale Over Time.

|

Model |

χ2 |

df |

CFI |

TLI |

RMSEA [90% CI] |

SRMR |

ΔCFI |

ΔTLI |

ΔRMSEA |

|

Configural invariance |

941.55 |

153 |

.973 |

.963 |

.046 [0.043, 0.049] |

.033 |

|

|

|

|

Metric invariance |

1037.78 |

161 |

.970 |

.960 |

.048 [0.045, 0.050] |

.042 |

.003 |

.003 |

.002 |

|

Scalar invariance |

1127.16 |

169 |

.967 |

.959 |

.049 [0.046, 0.051] |

.044 |

.003 |

.001 |

.001 |

|

Note. χ2 = Chi-square, df = Degrees of freedom, CFI = Comparative fit index, TLI = Tucker and Lewis Index, RMSEA = Root mean square error of approximation, SRMR = Standardized root mean residual. |

|||||||||

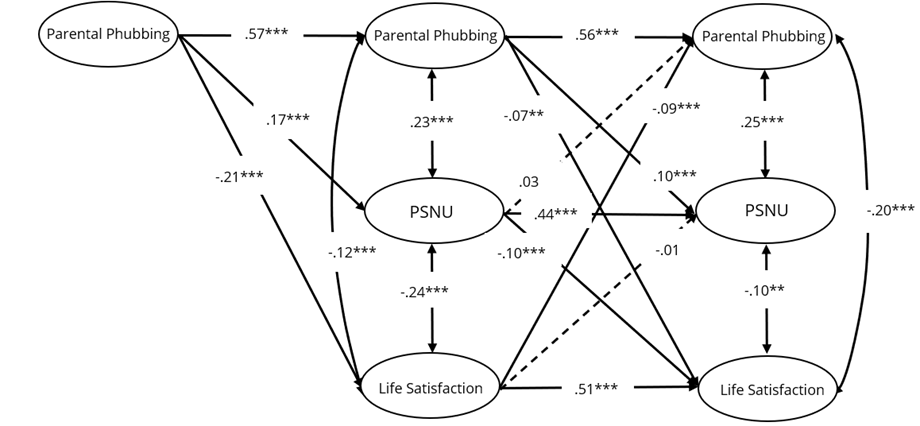

The cross-lagged model’s fit indices indicated that the model fitted the data well: CFI = .964, TLI = .956, RMSEA = .050, 90% CI [.047, .053], SRMR = .049. As shown in Figure 2, parental phubbing was highly stable over time. There were three significant concurrent correlations. Parental phubbing was positively associated with problematic social network use. Parental phubbing was negatively associated with adolescents’ life satisfaction. Problematic social network use was negatively associated with adolescents’ life satisfaction. In terms of cross-lagged effects, parental phubbing at T1 and T2 significantly and positively predicted subsequent problematic social network use at the next time point, respectively. Parental phubbing at T1 and T2 significantly and negatively predicted subsequent life satisfaction at the next time point, respectively. The cross-lagged effects of T2 problematic social network use on T3 adolescents’ life satisfaction and T2 adolescents’ life satisfaction on T3 parental phubbing were significance. Inversely, neither cross-lagged paths from T2 problematic social network use to T3 parental phubbing nor from T2 adolescents’ life satisfaction to T3 problematic social network use reached significance.

Figure 2. Cross-lagged Model with Longitudinal Relations among Parental Phubbing,

Problematic Social Network Use, and Life Satisfaction.

Note. All the reported parameters are standardized. PSNU = Problematic Social Network Use. **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Testing for the Mediating Role of Problematic Social Network Use

Results showed that the indirect effect of parental phubbing at Time 1 on life satisfaction at Time 3 via problematic social network use at Time 2, ab = −.016, 95% CI [−.027, −.008]. The confidence interval did not include zero, indicating that problematic social network use mediated the association between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction.

Testing for the Moderating Roles of Big Five Personality

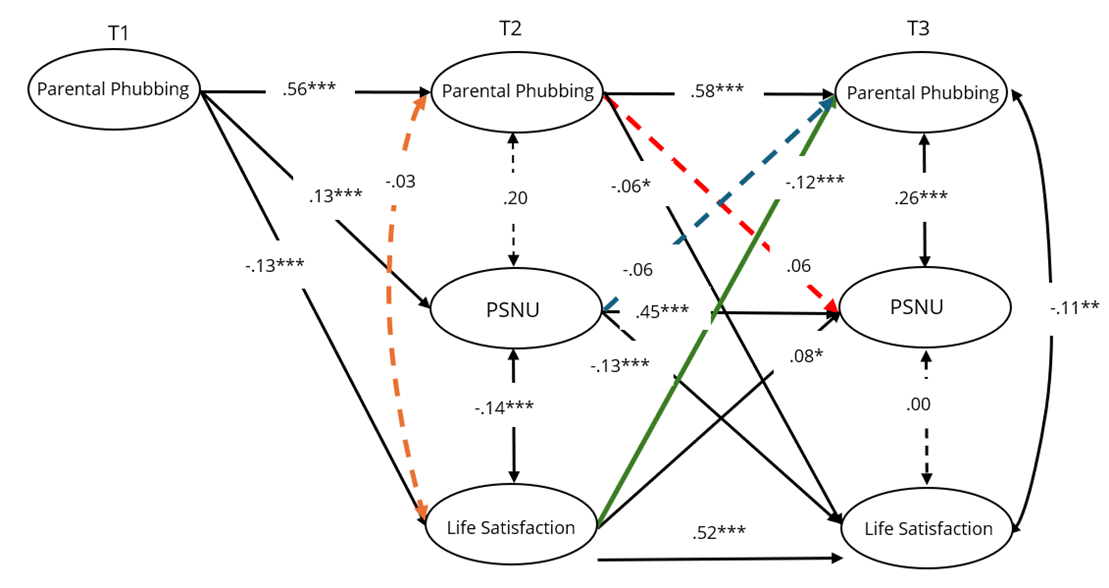

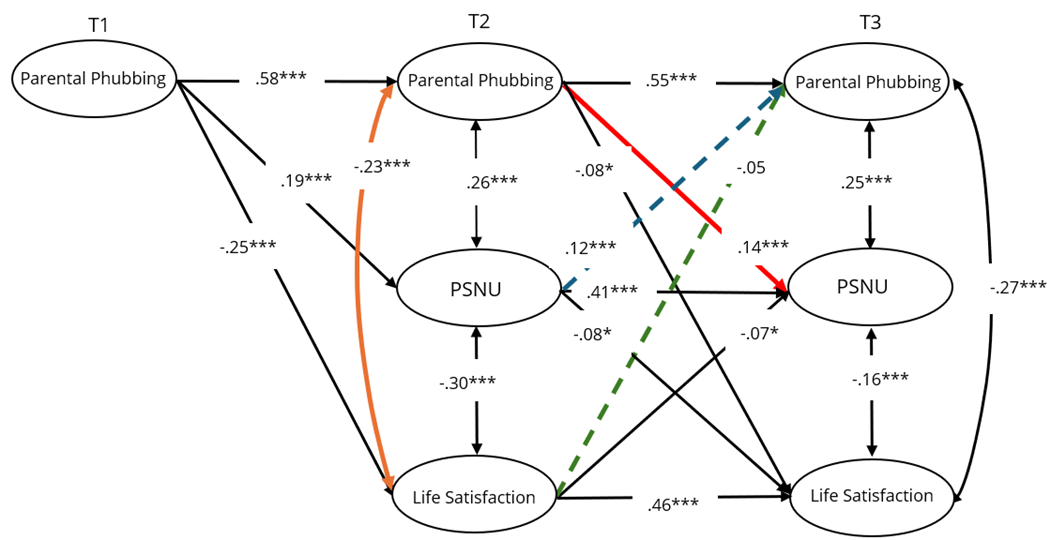

Multiple-group analyses were conducted to examine the moderating roles of neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, and extraversion. A fully constrained model was compared to a freely estimated model. When the path coefficients across agreeableness were restricted to equal, the comparison showed a significant difference between the unconstrained and fully constrained models, Δχ2(8) = 24.068, p = .002. However, there were no significant differences between the unconstrained and fully constrained models for the other personality traits. Those results indicated that agreeableness was a moderator in the cross-lagged model, while neuroticism, conscientiousness, openness, and extraversion were not. Then the current study tested potential low and high agreeableness differences for each longitudinal association separately (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. The multiple group analysis model of low levels of agreeableness in the longitudinal relations

among parental phubbing, PSNU, and life satisfaction.

Note. All the reported parameters are standardized. PSNU = Problematic Social Network Use. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Figure 4. The multiple group analysis model of high levels of agreeableness in the longitudinal relations

among parental phubbing, PSNU, and life satisfaction.

Note. All the reported parameters are standardized. PSNU = Problematic Social Network Use. * p < .05, *** p < .001.

Specifically, significant differences were obtained for three paths: (a) the path from T2 parental phubbing to T3 problematic social network use, Wald χ2(1) = 3.02, p = .032, βlow =.06, plow = .053 versus βhigh = .14, phigh < .001, (b) the path from T2 problematic social network use to T3 parental phubbing, Wald χ2(1) = 16.735, p = .001, βlow = −.06 plow = .059 versus βhigh = .12, phigh < .001, (c) the path from T2 adolescents’ life satisfaction to T3 parental phubbing, Wald χ2(1) = 6.68, p = .010, βlow = −.12, plow < .001 versus βhigh = −.05, phigh = .073.

Discussion

The current study explored the longitudinal association between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction across three years and investigated the underlying mediating and moderating mechanisms. First, there were reciprocal relations between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Second, problematic social network use showed a predictive effect on adolescents’ life satisfaction, but adolescents’ life satisfaction did not show a predictive effect on problematic social network use. Third, parental phubbing stably predicted problematic social network use over time, and parental phubbing predicted adolescents’ life satisfaction through problematic social network use. Finally, the differences in agreeableness were observed in the cross-lagged model.

The Relation between Parental Phubbing and Adolescents’ Life Satisfaction

As expected, parental phubbing at T1 and T2 significantly and negatively predicted subsequent life satisfaction at the next time point, respectively. Unlikely Liu et al.’s (2021) study, the current study used a cross-lagged design, providing strong evidence that parental phubbing significantly predicted adolescents’ life satisfaction. These results also provide new insight into adolescents’ life satisfaction. For adolescents’ life satisfaction, the bottom-up cognitive approach depends on the evaluation criteria chosen by adolescents themselves. Although adolescents become autonomy and less dependent on parents, parents’ attention to them is still valued (Noom et al., 2001). Adolescents in collectivism value connections with their families (Feldman, 2008). Parents’ neglect and negative interaction behavior bring negative feelings to adolescents, and this decreases adolescents’ life satisfaction. The importance and irreplaceability of parents are shown by the significant negative influence on adolescents’ life satisfaction. Therefore, parental phubbing is an important factor for adolescents’ life satisfaction.

T2 adolescents’ life satisfaction significantly predicted T3 parental phubbing. When adolescents have low life satisfaction, they are more likely to perceive high parental phubbing, although this perception may deviate from reality. There are two possible explanations for this phenomenon. Firstly, although adolescents have begun to shift their focus on lives and emotional dependence away from the family, parents remain the core source of happiness in their hearts (Moreno-Maldonado et al., 2020). Adolescents still want to maintain a close and positive relationship with their parents and want their parents’ support (Noller & Callan, 2015). Adolescents with low life satisfaction are often in a state of negative emotional and have a stronger desire for more attention and emotional support (Proctor et al., 2009; Suldo & Huebner, 2006). In this state, they are particularly sensitive to their parents' phubbing and are likely to perceive it as another example of a lack of emotional support, thus reinforcing these negative feelings. Secondly, adolescents begin to see themselves more from parents’ perspective as a result of their increased autonomy (Feldman, 2008). That means when adolescents perceive high parental phubbing, they are more likely to interpret parental phubbing as dislike and rejection from parents’ perspective, then further project the dissatisfaction with the overall state and quality of life onto their evaluation of their parents (Diener et al., 1985; Shin & Johnson, 1978). Furthermore, our sample is Chinese adolescents who are influenced by collectivism, which means the quality of the connection with their family is important (Feldman, 2008). Chinese adolescents are more likely to attribute their low life satisfaction to high parental phubbing. Thus, adolescents with low life satisfaction perceived high parental phubbing.

The more interesting to note is that there is a vicious cycle between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Specifically, parental phubbing leads to subsequent adolescents’ low life satisfaction and adolescents’ low life satisfaction further leads to perceived high parental phubbing. From the perspective of the dynamic systems model, parental phubbing is both an effect and a cause of adolescents’ life satisfaction. This suggests that there are two cognitive styles in the relation between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction: (a) bottom-up cognitive processing leads adolescents who perceived high parental phubbing to have low life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1985; Shin & Johnson, 1978); (b) top-down cognitive processing leads adolescents who have low life satisfaction to feel high parental phubbing. Parental phubbing decreases adolescents’ life satisfaction and adolescents with low life satisfaction are easier to perceive high parental phubbing. That is, when these adolescents have low life satisfaction, they are more likely to pay more attention to their parent’s behavior, which leads to perceived high parental phubbing.

Problematic Social Network Use and Adolescents’ Life Satisfaction

T2 problematic social network use significantly predicted T3 adolescents’ life satisfaction, while T2 adolescents’ life satisfaction did not predict T3 problematic social network use. Inconsistent with the previous study (Longstreet & Brooks, 2017), our results do not support that adolescents with low life satisfaction are more likely to develop problematic social network use. As far as we know, the predictive effect of life satisfaction on problematic social network use was only found in that one study, and the cross-sectional study with small samples (n = 251) led to poor stability, reliability, and validity of the results (Longstreet & Brooks, 2017). Therefore, in comparison, the results from the current cross-lagged study with large samples (n = 2407) are more reliable. Adolescents with problematic social network use are more likely to have low life satisfaction. However, low life satisfaction does not lead to adolescents’ problematic social network use. Problematic social network use negatively affects adolescents’ mental and physical abilities and further interferes with activities of daily living (Turel et al., 2011; Wurst et al., 2008). Thus, problematic social network use predicts adolescents’ low life satisfaction. This result suggests that the use of social networking sites should be controlled in a reasonable range to prevent problematic social network use leading to low life satisfaction.

The Mediating Role of Adolescents’ Problematic Social Network Use

As expected, parental phubbing predicted adolescents’ life satisfaction through problematic social network use. Parental phubbing leads to increased levels of problematic social network use among adolescents, which further decreases subsequent adolescents’ life satisfaction. Our finding contributes to the mediating role of problematic social network use between family factors and adolescents’ life satisfaction. First, parental phubbing leads to problematic social network use, which is consistent with the explanation of social compensation theory (Gross et al., 2002; Peter et al., 2005; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). Specifically, problematic social network use continue to play their compensatory role as a form of compensatory internet use during adolescence (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). Adolescents are more likely to use social networking sites to make up for unmet needs in their interactions with parents (Gross et al., 2002; Peter et al., 2005, Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). Thus, when adolescents perceive high parental phubbing would increase the risk of problematic social network use. More unfortunately, problematic social network use would bring another problem: low life satisfaction (Boer et al., 2020; Yu & Shek, 2018). This suggests that although adolescents use social networking sites to compensate for the negative impact of parental phubbing, the consequent problematic social network use leads to low life satisfaction. This is a hidden danger to the healthy development of adolescents.

The Moderation of Big Five Personality Traits

This study also explored the moderating effects of Big Five personality traits on the model. We found that agreeableness differences emerge in the cross-lagged pathways, but neuroticism, openness, conscientiousness, and extraversion did not show differences. Specifically, the differences of agreeableness in the cross-lagged pathways are mainly reflected in two aspects. First, for adolescents with high agreeableness, the relation between parental phubbing and problematic social network use is stable. Nevertheless, the relation became not stable for adolescents with low agreeableness. Agreeableness strengthened the predictive effect of parental phubbing on problematic social network use. According to the characteristics of agreeableness, a possible reason is that adolescents with high agreeableness are good at establishing relationships with people and also feel more sensitive to their relationships with the people around them (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010). Compared with low agreeableness, when adolescents with high agreeableness perceive high parental phubbing are more likely to have problematic social network use. Second, the bidirectional relations between parental phubbing and life satisfaction exists in low-agreeableness adolescents, not in high-agreeableness adolescents. Specifically, T2 life satisfaction significantly negatively predicted T3 parental phubbing for adolescents with low agreeableness. Nevertheless, the relation became not exist for adolescents with high agreeableness. One possible reason is that adolescents with low agreeableness lack the ability to establish relationships with people outside (J. M. Wang et al., 2017). Therefore, low-agreeableness adolescents rely more on parents, and communication with parents is more important. Compared with high-agreeableness adolescents, low-agreeableness adolescents are more likely to attribute the reason for low life satisfaction to parental phubbing. Ultimately, high agreeableness strengthens the predictive effect of parental phubbing on problematic social network use. Low agreeableness increases the possibility of a vicious circle between parental phubbing and adolescents’ low life satisfaction.

Limitations, Contributions, and Further Directions

Several limitations are worth noting. First, we did not have data on T1 problematic social network use and T1 adolescents’ life satisfaction. Thus, our findings should be replicated in longitudinal research designs. Second, the current study did not distinguish the differences in the effects of father’s phubbing and mother’s phubbing on adolescents’ life satisfaction. Based on the different roles of fathers and mothers in the parenting process, subsequent studies should distinguish between them. Third, the current study did not distinguish whether problematic social network use on different devices has different effects on adolescents’ life satisfaction. Given advances in technology, social networking sites can be accessed from many kinds of devices, including computers, pads, smartphones, and even smartwatches. Future studies may be able to explore whether problematic social network use is different by combining the characteristics of different devices. Fourth, this study sample may not be internationally representative. Cultural differences are considered to be an important factor affecting adolescents’ life satisfaction (Huebner, 2004). But our sample only included Chinese adolescents. Socio-cultural differences in human development during adolescence should be investigated in more cross-cultural studies. Finally, the measures in this study were self-reported only and could not avoid possible common method bias. Furthermore, there is a certain deviation between perception and objective fact. For example, it is difficult to distinguish and judge the gap between perceived and objective parental phubbing. Improving this point can further facilitate the targeting of interventions.

Despite the limitations, the current study displayed several contributions. From the perspective of theoretical value, the cross-lagged design elucidates the complex and dynamic processes among parental phubbing, problematic social network use, and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Specifically, the current study has deepened the understanding of the danger of parental phubbing, revealing that parental phubbing not only increases the possibility of subsequent problematic social network use in adolescents, but also reduces their future life satisfaction. Secondly, the large sample data of Chinese adolescents not only enhances the reliability of the results and increases the power to detect potentially subtle interactions involving Big Five personality traits, but also enriches the cross-cultural understanding of adolescents’ life satisfaction. This provides guiding information for the intervention work to set up different intervention programs for adolescents with different Big Five personality traits.

This research also has certain practical value. First, this study found a vicious cycle between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction. The findings suggest that parents should be encouraged to use mobile phones properly in the presence of adolescents, which can improve their life satisfaction. In addition, it also provides a new idea for intervention work. When parental phubbing levels are in the acceptable range, we can focus interventions on improving adolescents’ life satisfaction. When adolescents’ life satisfaction improves, they may not perceive as much parental phubbing. For example, interventionists can help adolescents effectively alleviate negative emotions and reduce their excessive reactions to negative stimuli through emotional regulation training. Interventionists can also guide adolescents in cognitive restructuring. For instance, replacing the negative thought “they don't love me” with a more objective interpretation, such as “parents might be dealing with work”. Furthermore, parents should actively create high-quality companionship scenarios, such as organizing outdoor activities, to compensate for the emotional needs gap caused by phubbing. Second, we confirmed the predictive effect of parental phubbing on adolescents’ life satisfaction via the mediation role of problematic social network use. The results indicate that problematic social network use is easily influenced by parental phubbing and leads to lower life satisfaction among adolescents. Therefore, we should recognize the negative effects of problematic social network use and realize that it is an important fulcrum to intervene the adolescents’ low life satisfaction.

Conclusion

Life satisfaction has significant influences on the physiological and psychological development of adolescents, and it attracts numerous attentions of scholars. The current study makes up for the shortcomings of previous studies by confirming that parental phubbing predicts adolescents’ life satisfaction and the longitudinal mediating effect of problematic social network use between parental phubbing and adolescents’ life satisfaction in a cross-lagged panel model with a large sample. This study fills the gap by finding the longitudinal predictive effect of problematic social network use on adolescents’ low life satisfaction. Furthermore, the current study explored the influence of different Big Five personality traits and found differences in the model caused by different levels of agreeableness.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Use of AI Services

The authors declare they have not used any AI services to generate or edit any part of the manuscript or data.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2025 Xiaoyan Zhou, Fangfang Tian, Xingchao Wang, Xinyi Chen, Jiping Yang, Xueqi Zeng