Unraveling the positive and negative roles of positive body-focused social media interactions in adolescents’ body image

Vol.19,No.5(2025)

Despite the increasing circulation of potentially positive body-focused social media content, it remains unclear how interactions with such content relate to adolescents’ positive and negative body image. This cross-sectional study (n = 690 adolescents, Mage = 16.41, SDage = .98, 55.96% girls) examined the relations between interactions with potentially positive content (i.e., exposure and posting of Body Positive (BoPo) content, receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media), susceptibility factors (i.e., aesthetic hypersensitivity, sex), a positive body image component (i.e., body appreciation) and negative body image components (i.e., self-objectification, internalization of appearance ideals, appearance comparisons with peers). Receiving positive appearance comments was associated with higher levels of body self-love, self-objectification, internalization and appearance comparisons. Moreover, there was a positive association between BoPo posting and negative body image components (i.e., higher levels of self-objectification, internalization, appearance comparisons). Aesthetic hypersensitivity and sex appeared to moderate some of the examined relationships. These findings indicate that positive-intended content may relate to the development of a positive body image, but also to a negative body image. Implications are discussed.

body image; social media; positive social media content; adolescents; body positivity; hypersensitivity

Ilse Vranken

Media Psychology Lab, Department of Communication Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Research Foundation Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen), Brussels, Belgium; Media & Tourism Research, PXL University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Hasselt, Belgium

Ilse Vranken, PhD, is head of research of Media & Tourism Research (PXL, Belgium) and research affiliate at the Media Psychology Lab (KU Leuven, Belgium). Ilse studies (1) the role of digital media and new socialization actors (e.g., influencers) and (2) environmental and social sustainability in the field of journalism, communication and tourism. Her research is practice-oriented and offers solutions to problems experienced by workers in these three fields.

Lara Schreurs

Media Psychology Lab, Department of Communication Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Research Foundation Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen), Brussels, Belgium

Lara Schreurs, assistant professor, Media Psychology Lab, KU Leuven, studies the role of social media literacy in media effect processes. Specifically, she aims to explore the development of social media literacy through interventions as well as the effects of social media use on well-being and identity among adolescents.

Mireia Montaña Blasco

GAME (Learning, Media and Entertainment), Faculty of Information and Communication Sciences, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC), Barcelona, Spain

Mireia Montaña Blasco, PhD in Communication, Professor in Information and Communication Sciences Studies, and Academic Director of the Master's in Strategy and Creativity in Advertising at Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC) in Barcelona, Spain. Her research focuses on the impact of media on people’s well-being, particularly among vulnerable groups such as children, young people, and the elderly. Her main research interests include new media practices, media consumption, and the influence of persuasive communication on individuals. Since 2013, she has been a member of the GAME Research Group at UOC.

Laura Vandenbosch

Media Psychology Lab, Department of Communication Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Laura Vandenbosch, associate professor & director of the Media Psychology Lab, KU Leuven, studies how young users’ differential media uses are intertwined with their identity development and well-being. Currently, she and her team of PhD students and postdoctoral researchers are involved in several (international) research projects (e.g., ERC starting grant MIMIc project) aimed to study how media may affect well-being by focusing on factors that have not been understood well, such as the role of social relationships, cultural background, sexualization, media literacy and malleability beliefs. Open science, team science and academic kindness are key values in Vandenbosch's team and their work.

Ahadi, B., & Basharpoor, S. (2010). Relationship between sensory processing sensitivity, personality dimensions and mental health. Journal of Applied Sciences, 10(7), 570–574. https://doi.org/10.3923/jas.2010.570.574

Amiri, S., & Navab, A. G. (2019). Emotion regulation, brain behavioural systems, and sensory sensitivity in sociocultural attitudes towards appearance in adolescents. Neuropsychiatria i Neuropsychologia, 14(1–2), 32–38. https://doi.org/10.5114/nan.2019.87726

Avalos, L., Tylka, T. L., & Wood-Barcalow, N. (2005). The Body Appreciation Scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image, 2(3), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.06.002

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology, 3(3), 265–299. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03

Berk, L. E. (2004). Development through the lifespan. Prentice Hall.

Brady, W. J., Gantman, A. P., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2020). Attentional capture helps explain why moral and emotional content go viral. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 149(4), 746–756. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000673

Brathwaite, K. N., & DeAndrea, D. C. (2021). BoPopriation: How self-promotion and corporate commodification can undermine the body positivity (BoPo) movement on Instagram. Communication Monographs, 89(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2021.1925939

Burnell, K., George, M. J., Kurup, A. R., & Underwood, M. K. (2021). “Ur a freakin goddess!”: Examining appearance commentary on Instagram. Psychology of Popular Media, 10(4), 422–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000341

Calogero, R. M., & Thompson, J. K. (2010). Gender and body image. In J. Chrisler & D. McCreary (Eds.), Handbook of gender research in psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 153–184). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1467-5_8

Chen, J. (2024). Application of audiovisual language on the TIKTOK platform and analysis of its communication effect. Advances in Social Behavior Research, 11, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.54254/2753-7102/11/2024104

Choma, B. L., Foster, M. D., & Radford, E. (2007). Use of objectification theory to examine the effects of a media literacy intervention on women. Sex Roles, 56(9–10), 581–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9200-x

Cohen, R., Fardouly, J., Newton-John, T., & Slater, A. (2019b). #BoPo on Instagram: An experimental investigation of the effects of viewing body positive content on young women’s mood and body image. New Media & Society, 21(7), 1546–1564. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819826530

Cohen, R., Irwin, L., Newton-John, T., & Slater, A. (2019a). #bodypositivity: A content analysis of body positive accounts on Instagram. Body Image, 29, 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.02.007

Cohen, R., Newton-John, T., & Slater, A. (2020). The case for body positivity on social media: Perspectives on current advances and future directions. Journal of Health Psychology, 26(13), 2365–2373. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105320912450

de Lenne, O., Eggermont, S., Smits, T., & Vandenbosch, L. (2021, May 27–31). The role of CSR fit in campaigns featuring non-idealized models [Conference presentation]. 71st Annual Conference of the International Communication Association, Virtual.

Dhadly, P. K., Kinnear, A., & Bodell, L. P. (2023). #BoPo: Does viewing body positive TikTok content improve body satisfaction and mood? Eating Behaviors, 50, Article 101747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2023.101747

Feltman, C. E., & Szymanski, D. M. (2018). Instagram use and self-objectification: The roles of internalization, comparison, appearance commentary, and feminism. Sex Roles, 78(5), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0796-1

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women's lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Harriger, J. A., Wick, M. R., Sherline, C. M., & Kunz, A. L. (2023). The body positivity movement is not all that positive on TikTok: A content analysis of body positive TikTok videos. Body Image, 46, 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.06.003

Holbert, R. L., & Park, E. (2020). Conceptualizing, organizing, and positing moderation in communication research. Communication Theory, 30(3), 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtz006

Holland, G., & Tiggemann, M. (2016). A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image, 17, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008.

Karsay, K., Trekels, J., Eggermont, S., & Vandenbosch, L. (2021). “I (don’t) respect my body”: Investigating the role of mass media use and self-objectification on adolescents’ positive body image in a cross-national study. Mass Communication and Society, 24(1), 57–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2020.1827432

Kenny, U., O’Malley-Keighran, M.-P., Molcho, M., & Kelly, C. (2017). Peer influences on adolescent body image: Friends or foes? Journal of Adolescent Research, 32(6), 768–799. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558416665478

Kim, H. M. (2020). What do others’ reactions to body posting on Instagram tell us? The effects of social media comments on viewers’ body image perception. New Media & Society, 23(12), 3448–3465. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820956368

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Koechlin, H., Donado, C., Locher, C., Kossowsky, J., Lionetti, F., & Pluess, M. (2023). Sensory processing sensitivity in adolescents reporting chronic pain: An exploratory study. PAIN Reports, 8(1), Article e1053. https://doi.org/10.1097/PR9.0000000000001053

Kvardova, N., Machackova, H., & Gulec, H. (2023). ‘I wish my body looked like theirs!’: How positive appearance comments on social media impact adolescents' body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 47, Article 101630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.101630

Lazuka, R. F., Wick, M. R., Keel, P. K., & Harriger, J. A. (2020). Are we there yet? Progress in depicting diverse images of beauty in Instagram’s body positivity movement. Body Image, 34, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.05.001

Liss, M., Mailloux, J., & Erchull, M. J. (2008). The relationships between sensory processing sensitivity, alexithymia, autism, depression, and anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(3), 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.04.009

Maes, C., Schreurs, L., van Oosten, J. M., & Vandenbosch, L. (2019). #(Me) too much? The role of sexualizing online media in adolescents’ resistance towards the metoo-movement and acceptance of rape myths. Journal of adolescence, 77(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.10.005

Mahon, C., & Hevey, D. (2021). Processing body image on social media: Gender differences in adolescent boys’ and girls’ agency and active coping. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 626763. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.626763

McCabe, M. P., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2003). Sociocultural influences on body image and body changes among

adolescent boys and girls. The Journal of Social Psychology, 143(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540309598428

McGovern, O., Collins, R., & Dunne, S. (2022). The associations between photo-editing and body concerns among females: A systematic review. Body Image, 43, 504–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.10.013

McLaren, L., Kuh, D., Hardy, R., & Gauvin, L. (2004). Positive and negative body-related comments and their relationship with body dissatisfaction in middle-aged women. Psychology & Health, 19(2), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044031000148246

Noll, S. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). A mediational model linking self‐objectification, body shame, and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22(4), 623–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00181.x

Paddock, D. L., & Bell, B. T. (2021). “It’s better saying I look fat instead of saying you look fat”: A qualitative study of UK adolescents’ understanding of appearance-related interactions on social media. Journal of Adolescent Research, 39(2), 243–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/07435584211034875

Pluess, M. (2015). Individual differences in environmental sensitivity. Child Development Perspectives, 9(3), 138–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12120

Pluess, M., Assary, E., Lionetti, F., Lester, K. J., Krapohl, E., Aron, E. N., & Aron, A. (2018). Environmental sensitivity in children: Development of the Highly Sensitive Child Scale and identification of sensitivity groups. Developmental Psychology, 54(1), 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000406

Rodgers, R. F., Paxton, S. J., & Wertheim, E. H. (2021). #Take idealized bodies out of the picture: A scoping review of social media content aiming to protect and promote positive body image. Body Image, 38, 10–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.03.009

Rodgers, R. F., Paxton, S. J., Wertheim, E. H., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2024). Better than average Bopo: Identifying which body positive social media content is most helpful for body image among women. Body Image, 51, Article 101773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2024.101773

Rodgers, R. F., Wertheim, E. H., Paxton, S. J., Tylka, T. L., & Harriger, J. A. (2022). #Bopo: Enhancing body image through body positive social media-evidence to date and research directions. Body Image, 41, 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.03.008

Rubaltelli, E., Scrimin, S., Moscardino, U., Priolo, G., & Buodo, G. (2018). Media exposure to terrorism and people's risk perception: The role of environmental sensitivity and psychophysiological response to stress. British Journal of Psychology, 109(4), 656–673. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12292

Rudgard, W. E., Dr, Orkin, M., Shenderovich, Y., Saminathen, M. G., Zhou, S., & Cluver, L. (2021, August 5). Adolescent accelerator multi-outcome methods. https://osf.io/n6jy7.

Schettino, G., Capasso, M., & Caso, D. (2023). The dark side of #bodypositivity: The relationships between sexualized body-positive selfies on Instagram and acceptance of cosmetic surgery among women. Computers in Human Behavior, 140, Article 107586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107586

Scrimin, S., Osler, G., Pozzoli, T., & Moscardino, U. (2018). Early adversities, family support, and child well-being: The moderating role of environmental sensitivity. Child: Care, Health and Development, 44(6), 885–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12596

Slater, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2015). Media exposure, extracurricular activities, and appearance-related comments as predictors of female adolescents’ self-objectification. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39(3), 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684314554606

Smolewska, K. A., McCabe, S. B., & Woody, E. Z. (2006). A psychometric evaluation of the Highly Sensitive Person Scale: The components of sensory-processing sensitivity and their relation to the BIS/BAS and “Big Five”. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(6), 1269–1279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.09.022

Sobocko, K., & Zelenski, J. M. (2015). Trait sensory-processing sensitivity and subjective well-being: Distinctive associations for different aspects of sensitivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.045

Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

Thompson, J. K., & Stice, E. (2001). Thin-ideal internalization: Mounting evidence for a new risk factor for body-image disturbance and eating pathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(5), 181–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00144

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10312-000

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1991). The Physical Appearance Comparison Scale. The Behavior Therapist, 14, 174.

Thompson, J. K., van den Berg, P., Roehrig, M., Guarda, A. S., & Heinberg, L. J. (2004). The Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Scale‐3 (SATAQ‐3): Development and validation. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35(3), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10257

Trekels, J., & Eggermont, S. (2023). Adolescents’ multi-layered media processing: A panel study on positive and negative perceptions toward ideals and adolescents’ appearance anxiety. Communication Research, 51(6), 607–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502231151471

Trekels, J., Ward, L. M., & Eggermont, S. (2018). I “like” the way you look: How appearance-focused and overall Facebook use contribute to adolescents' self-sexualization. Computers in Human Behavior, 81, 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.12.020

Tylka, T. L., & Wood-Barcalow, N. L. (2015). What is and what is not positive body image? Conceptual foundations and construct definition. Body Image, 14, 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.04.001

Valkenburg, P. M., Peter, J., & Schouten, A. P. (2006). Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents' well-being and social self-esteem. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9(5), 584–590. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.584

Vandenbosch, L., & Eggermont, S. (2014). The three-step process of self-objectification: Potential implications for adolescents’ body consciousness during sexual activity. Body Image, 11(1), 77–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.10.005

Vandenbosch, L., Fardouly, J., & Tiggemann, M. (2022). Social media and body image: Recent trends and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, Article 101289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.12.002

Vandendriessche, K., Steenberghs, E., Matheve, A., Georges, A., & De Marez, L. (2021). Imec.digimeter 2020: Digitale trends in Vlaanderen [Imec.digimeter 2020: Digital trends in Flanders]. Imec. http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-8717212

Vangeel, L., Trekels, J., Eggermont, S., & Vandenbosch, L. (2020). Adolescents’ objectification of their same-sex friends: Indirect relationships with media use through self-objectification, rewarded appearance ideals, and online appearance conversations. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 99(2), 538–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699020959723

Vendemia, M. A., DeAndrea, D. C., & Brathwaite, K. N. (2021). Objectifying the body positive movement: The effects of sexualizing and digitally modifying body-positive images on Instagram. Body Image, 38, 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.03.017

Wang, Y., Wang, X., Liu, H., Xie, X., Wang, P., & Lei, L. (2020). Selfie posting and self-esteem among young adult women: A mediation model of positive feedback and body satisfaction. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(2), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318787624

Wood-Barcalow, N. L., Tylka, T. L., & Augustus-Horvath, C. L. (2010). “But I like my body”: Positive body image characteristics and a holistic model for young-adult women. Body Image, 7(2), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.01.001

Authors’ Contribution

Ilse Vranken: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. Lara Schreurs: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, methodology, writing—review & editing. Mireia Montaña Blasco: writing—original draft. Laura Vandenbosch: conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

October 23, 2023

Revisions received:

May 13, 2025

October 10, 2025

Accepted for publication:

October 16, 2025

Editor in charge:

Alexander P. Schouten

Introduction

Researchers are increasingly paying attention to the existence of different types of positive body-focused content on social media (Cohen, Irwin, et al., 2019) and how interactions with such content can positively affect individuals’ body image. Yet, this research primarily focused on undergraduate women (Cohen et al., 2020; Rodgers et al., 2021, 2024) and largely ignored adolescent samples.

The lack of attention to adolescents is surprising because social media play an important role in their body image development (Mahon & Hevey, 2021). During adolescence, changing levels of estrogen, testosterone, and growth hormone trigger body composition adjustments that include alterations in the quantity and distribution of body fat (Berk, 2004). These body changes, together with the socio-cultural pressures of dominant appearance ideals, make the development of a healthy body image challenging (Berk, 2004). This process is further complicated in the context of social media, where appearance norms are prominently emphasized and adherence to these norms is rewarded (Paddock & Bell, 2021). Interactions with positive body-focused social media content that criticizes appearance norms may counter these body image challenges (Cohen, Irwin, et al., 2019). Understanding how and under which circumstances interactions with positive body-focused social media content relates to adolescents’ body image development may thus be particularly interesting.

Adolescents may interact with positive body-focused social media content in multiple ways, including receiving positive appearance-related comments from peers, being exposed to body positive (BoPo) content, and posting BoPo content themselves (e.g., Kvardova et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2020). Yet, the distinct roles these forms of interaction play in adolescents’ body image development have not yet been systematically examined. Moreover, some studies have raised concerns that certain BoPo content may contain subtle body-focused cues that could undermine its intended positive effects and potentially harm body image (Brathwaite & DeAndrea, 2021; Harriger et al., 2023).

Against this backdrop, the current study investigates the associations between three forms of interactions with positive body-focused content (i.e., peer comments, exposure, and posting) and key positive (1) and negative (2-4) body image components; i.e., (1) body appreciation, (2) self-objectification, (3) internalization of appearance ideals and (4) appearance comparisons with peers. These associations are examined through the lens of the Tripartite Model (Thompson et al., 1999) and social cognitive theory of mass communication (Bandura, 2001). Going beyond a homogeneous media effects perspective, this study also considers how individual susceptibility factors, specifically sex (Trekels et al., 2018) and aesthetic hypersensitivity (Amiri & Navab, 2019), may shape adolescents’ responses to positive body-focused content.

Adolescents and Various Types of Interactions With “Positive” Body-Focused Content on Social Media

Ninety percent of adolescents use social media daily (Vandendriessche et al., 2021). Social media allows for a wide range of activities to engage with content and peers. This study focuses on three interactions through which adolescents may engage with positive content on social media. First, social media is characterized by peer networks in which adolescents interact with each other (Trekels & Eggermont, 2023). One way of interacting is to comment on each other’s posts. Adolescents may receive positive appearance comments from peers on their posts (Feltman & Szymanski, 2018; Paddock & Bell, 2021). During adolescence, such comments are likely because the peer environment is characterized by appearance conversations and appearance feedback (Kenny et al., 2017). Such appearance feedback may manifest itself even more strongly online because this context (e.g., the option to like and easily post a comment) facilitates such dynamics).

Besides positive appearance feedback from peers, users may also be exposed to or post BoPo content (Trekels & Eggermont, 2023). BoPo content can come from BoPo accounts hosted by influencers, or from the user’s peers (Cohen, Irwin, et al., 2019; Lazuka et al., 2020). Adolescents may also post BoPo content themselves. Although research on young adults shows that they embrace the body positivity movement (de Lenne et al., 2021), the extent to which adolescents post BoPo content is unclear.

Positive and Negative Content in Positive Body-Focused Content on Social Media

What positive appearance comments from peers and exposure to/posting BoPo content have in common is the inclusion of positive body-focused content or messages that empower users’ body image (Cohen, Fardouly, et al., 2019; Harriger et al., 2023).

Positive appearance comments from peers on social media aim to make individuals feel good about their bodies (Paddock & Bell, 2021). Similarly, a content analysis on BoPo posts on Instagram revealed that BoPo posts almost always (80.15%) contain themes about loving and appreciating one’s own body (Cohen, Irwin, et al., 2019). The three most frequently occurring themes are (1) accepting and loving one’s body, (2) perceiving a wide range of bodies and appearances as attractive and beautiful, and (3) having positive feelings and characteristics such as body confidence (Cohen, Irwin, et al., 2019; Lazuka et al., 2020). Also, on TikTok BoPo is present. A content analysis of 342 BoPo TikTok videos indicated that 32.2% contained positive themes with the most popular theme being accepting and loving one’s body (Harriger et al., 2023). These themes can be present in visual aspects (e.g., portrayals of BoPo text via an image, portrayals of people and bodies via images) as well as in textual aspects (e.g., portrayals of BoPo messages through captions and hashtags; Harriger et al., 2023; Rodgers et al., 2024).

Yet, positive appearance comments and BoPo content have also been criticized for sometimes containing elements that may undermine its positivity including sexual objectification practices and highlighting appearance ideals (Brathwaite & DeAndrea, 2021; Harriger et al., 2023; Vendemia et al., 2021). Concerning positive appearance comments, adolescents tend to provide positive comments to individuals who meet appearance ideals (Paddock & Bell, 2021). These comments typically contain compliments about body parts, which can provoke sexualization (Paddock & Bell, 2021). Even if the underlying intention of positive appearance comments is positive (e.g., loving yourself, allowing more people to be considered sexy), these comments still center the importance of physical appearance.

Similar practices are present in BoPo content. BoPo content has been shown to sometimes promote narrow appearance ideals and sexual objectification (Cohen, Irwin, et al., 2019; Harriger et al., 2023; Lazuka et al., 2020). To illustrate, some content depicts weight loss practices that make one “fit,” but also thin and muscular (Cohen, Irwin, et al., 2019; Lazuka et al., 2020). Some content praises the thin ideal in their captions (Lazuka et al., 2020) or highlight the thin ideal on a visual level (Harriger et al., 2023). One-third of BoPo pictures even contained sexual objectification by, for instance, showing people in sexually suggestive poses (Cohen, Irwin, et al., 2019).

Together, this co-occurrence of positive and negative messages in positive body-focused content suggests that interactions with such content may contribute to components of both a positive and negative body image (Brathwaite & DeAndrea, 2021; Cohen, Fardouly, et al., 2019; Kvardova et al., 2023). This reasoning aligns with research revealing that positive and negative outcomes can occur simultaneously as a response to media consumption (Trekels & Eggermont, 2023).

Social Media Interactions and Users’ Positive and Negative Body Images

Regarding a positive body image, the most studied indicator is body appreciation (Rodgers et al., 2022). Body appreciation is a component of individuals’ positive body image and includes the acceptance of one’s body despite its weight, shape, and imperfections, respecting one’s body, protecting one’s body by rejecting unrealistic beauty ideals, and holding favorable opinions towards one body (Avalos et al., 2005). As a positive body image may co-occur with a negative body image (Wood-Barcalow et al., 2010), this study also focuses on adolescents’ negative body image components. While research on negative body image is extensive, this study focuses on the three key negative body image components (Vandenbosch et al., 2022). That is self-objectification (i.e., valuing appearance-based attitudes over competence-based attitudes; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), internalization of appearance ideals (i.e., “cognitively buying into socially defined ideals of attractiveness”, Thompson & Stice, 2001; p. 181), and appearance comparisons with peers (i.e., comparing one’s appearance to the appearance of peers Thompson et al., 1991).

While empirical evidence revealed that links exist between interactions with positive body-focused content and users’ positive (e.g., Wang et al., 2020) and negative body image (e.g., Vendemia et al., 2021), research on how these different types of interactions may simultaneously correlate with both positive and negative body image components remain largely lacking.

The Tripartite Model (Thompson et al., 1999) combined with Social cognitive theory of mass communication (Bandura, 2001) may explain how different types of interactions with positive body-focused content may be associated with both positive and negative body image components. As for the negative body image components, the Tripartite Model highlights that appearance-related pressures may come from media role models and from peers. If messages from role models and peers focus on sexualization and adherence to narrow appearance ideals, it evokes pressures as users typically internalize these messages. Although the Tripartite model did not include social media, it can be assumed that appearance-related messages from media role models and peers encountered in social media have similar workings. Such appearance pressures may shape adolescents’ development of negative body image components, such as internalization of appearance ideals and social comparison with peers (Thompson et al., 1999).

In a similar vein, social cognitive theory of mass communication suggests that media users may endorse cognitions and behaviors that adolescents observe from (mediated) role models (Bandura, 2001). Given that some positive body-focused social media interactions, still focus on appearance and sometimes even contain a “hidden focus on appearance ideals or includes sexual objectification (Cohen, Irwin, et al., 2019), social cognitive theory of mass communication (Bandura, 2001) would expect that users may also endorse the negative body image components (e.g., internalization of appearance ideals, appearance comparisons with peers, self-objectification) and behaviors that are modeled by role models. At the same time, positive body-focused social media interactions also contain messages that direct its users into developing positive body image components (Cohen, Irwin, et al., 2019). Following, social cognitive theory of mass communication, a user may endorse thus simultaneously also messages in line with a positive body image. Moreover, Bandura (2001) informs such dual relationships are not limited to observing role models. Social cognitive theory of mass communication highlights the dynamic interactions between one’s own behavior and identity suggesting that the types of behavior one shows will affect a users’ identity (Bandura, 2001). For self-posting of body positive content, this may entail that the hidden focus in one’s posts on appearance ideals may further strengthen one’s negative body, while the simultaneously embedded positive messages may evoke body appreciation.

Theory thus hints at the possibility that the same appearance-focused social media interaction may be related to components of a positive and a negative body image. Applied to the current study and with regards to receiving positive appearance feedback from peers online, research on offline peer interactions has indeed indicated positive relationships between receiving appearance compliments from peers and higher body esteem (McLaren et al., 2004), and body satisfaction (Wang et al., 2020) among adults. In addition, research also illustrated that receiving positive appearance comments relates to negative body image components such as self-objectification, appearance-related consciousness, body dissatisfaction, and ideal-body perceptions (Burnell et al., 2021; Kim, 2020; Kvardova et al., 2023; Slater & Tiggemann, 2015). Whether such relationships with both positive and negative body image components also occur in a social media context and with adolescents is still unclear.

As for, exposure to BoPo content studies showed exposure to BoPo content improved women’s body satisfaction (Cohen, Fardouly, et al., 2019; Dhadly et al., 2023) and decrease their negative affect (Dhadly et al., 2023). Other experimental studies among adult women indicated that exposure to BoPo content which also included sexual objectification practices caused greater appearance ideal endorsement and self-objectification (Cohen, Fardouly, et al., 2019; Vendemia et al., 2021). Moreover, exposure to BoPo content has been linked to self-objectification even when sexual objectification was not present (Cohen, Fardouly, et al., 2019). Similarly, BoPo content that focuses too much on individuals’ bodies caused a decrease in body satisfaction and positive affect and an increase in negative affect among adult women (Dhadly et al., 2023). Research also revealed positive associations between sexualized body-positive selfies and body surveillance and reduced body satisfaction (Schettino et al., 2023). Research thus suggests that BoPo content may affect negative and positive body image components (e.g., Dhadly et al., 2023; Schettino et al., 2023). However, if similar associations exist among adolescents remains largely lacking (according to our knowledge).

As for posting BoPo content, research is largely lacking. Some preliminary evidence hints that dual relationships exist when users in the offline world direct their behavior toward being body positive. An intervention instructing individuals to engage critically with appearance ideals and to adopt a positive body image (just like users do when posting BoPo content) indeed showed an increase in self-objectification (Choma et al., 2007).

Often, research does not consider that the same interactions with content on social media may relate simultaneously to users’ positive and negative body image. Additionally, research often focuses on only one negative body image component even though self-objectification, internalization of appearance ideals, and appearance comparisons are all likely to be associated when interacting with body-focused social media content (Vandenbosch et al., 2022). This study aims to uniquely integrate three different types of interactions with positive body-focused content, acknowledging that adolescents do not engage with such content in isolation. Social media is a dynamic space in which exposure, interaction and feedback from peers co-occur and consequently shape body image in complex ways. Therefore, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1–H2: Receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media (Ha), exposure to BoPo social media content (Hb), and BoPo social media content posting behaviors (Hc) are positively related to adolescents’ body appreciation (H1a–c), self-objectification (H2a1, H2b1, H2c1), internalization of appearance ideals (H2a2, H2b2, H2c2), and appearance comparison with peers (H2a3, H2b3, H2c3).

Differential Susceptibility: Aesthetic Hypersensitivity

Theories, such as the Tripartite Model (Thompson et al., 1999) combined with Social cognitive theory of mass communication (Bandura, 2001) reveal that differential susceptibility characteristics play a role in the relationships between media usage and the related outcomes. Depending on such factors, adolescents may respond differently to media. In this context, studies have called for more insights into exploring a wider diversity of susceptibility factors in the field of social media and body image (Vandenbosch et al., 2022). One factor that may be important is environmental sensitivity.

Environmental sensitivity refers to a personality trait in which people differ in the extent to which they process positive and negative stimuli in their environment (Pluess, 2015). Environmental sensitivity is typically assessed using three different subcomponents, namely ease of excitation, low sensory thresholds and aesthetic hypersensitivity (AES; Pluess et al., 2018). The latter mentioned subcomponent of environmental sensitivity, that is AES, may be particularly interesting to examine in this study. The concept of AES can be defined as a personality trait in which individuals respond more emotionally and intensively to aesthetic stimuli in one’s environment, such as feeling happy when listening to music, loving nice tastes and smells, and noticing small changes in one’s environment (Pluess et al., 2018). Individuals with high AES pay thus more attention to aesthetic details in their environment (Ahadi & Basharpoor, 2010; Liss et al., 2008). This heightened attention to aesthetic stimuli can uplift adolescents and thus relate to positive psychological outcomes (e.g., positive affect; Sobocko & Zelenski, 2015). Simultaneously, research has indicated that people with high AES may also experience negative psychological outcomes due to this heightened sensitivity to aesthetic components (e.g., internalization of appearance ideals, anxiety; Amiri & Navab, 2019; Liss et al., 2008).

Although AES does not directly assess the social media context, AES reflects a broader orientation on how people react to a variety of environments rich in symbolic, visual, and auditory cues. Such cues can also be found on platforms like Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok, which heavily rely on aesthetic and emotionally evocative content, particularly body-focused posts (Brady et al., 2020; Chen, 2024). This makes AES a particularly relevant construct in order to understand individual differences in adolescents’ responses to this type of content.

Incorporating such general person-level traits like AES into media research can offer pivotal insights into how individuals internally process and respond to stimuli that are also present in social media environments. To illustrate, individuals high in AES tend to have stronger emotional reactions to positive aesthetic stimuli in their environment and experience heightened positive effect in response to such rewarding input (Smolewska et al., 2006). This suggests that they may also be more responsive to the positive elements encountered on social media compared to individuals with lower AES. At the same time, individuals high in AES are also more emotionally reactive to negative aesthetic cues. This heightened sensitivity may make them more attuned to potentially harmful or appearance-driven aspects embedded within positive content. In line with existing critiques of certain body-positive content (Lazuka et al., 2020), adolescents with high AES may be particularly receptive to subtle appearance-related messages in this content, which could lead to increased self-objectification, internalization of appearance ideals, and appearance-based comparisons.

Although research supporting links between positive body-focused content on social media and adolescents’ positive and negative body images is non-existent, research found proof for the moderating role of environmental sensitivity dimensions in media effects research in other domains. Specifically, one experimental study revealed that people who scored high on environmental hypersensitivity indeed experienced greater effects of mediated pictures because they processed the depicted information to a greater extent (Rubaltelli et al., 2018). As AES has not yet been considered in media research regarding body-focused social media content, we propose a positive contributory moderation (Holbert & Park, 2020) in which the strength of our examined relations depends on AES.

H3: The positive relations between receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media (H3a), exposure to BoPo social media content (H3b), BoPo social media content posting behaviors (H3c) and adolescents’ body appreciation will be stronger for adolescents with higher levels of AES.

H4: The positive relations between receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media (H4a), exposure to BoPo social media content (H4b), BoPo social media content posting behaviors (H4c), on the one hand, and self-objectification (H4a1, H4b1, H4c1), internalization of appearance ideals (H4a2, H4b2, H4c2), and appearance comparisons with peers (H4a3, H4b3, H4c3) on the other hand will be stronger for adolescents with higher levels of AES.

Aesthetic Hypersensitivity and Sex

Theories justify other factors as possibly further intensifying the moderating influence of a susceptibility factor such as AES (Bandura, 2001), and sex may be such a factor (Trekels et al., 2018). That is because sex differences may exist in (1) individuals’ hypersensitivity levels, (2) social media interactions with positive body-focused content, and (3) positive versus negative body image components (Burnell et al., 2021; Scrimin et al., 2018). Scrimin et al. (2018) reported positive correlations between hypersensitivity and sex, suggesting that girls are more sensitive toward positive cues in their environment. As for social media use, young women and girls are more frequently involved in interactions with positive body-focused content than young men and boys as they more frequently receive appearance comments and are more frequently engaged in appearance-focused social media use (Burnell et al., 2021; Trekels et al., 2013).

Furthermore, sex differences occur regarding body image. Whereas negative body image components, such as internalization of appearance ideals, self-objectification, and appearance comparisons with peers, are more common among girls, body appreciation is more common among boys (Karsay et al., 2021; Trekels et al., 2018; Tylka & Woord-Barcalow, 2015). Consequently, boys versus girls with higher versus lower levels of AES may process positive body-focused content differently. Following prior research (Karsay et al., 2021), boys with high AES may extract more positive elements from positive body-focused social media interactions, whereas girls with high AES may extract more negative elements in such social media interactions compared to individuals with lower AES. Accordingly, the relations between interactions with positive body-focused content and positive body image component (i.e., body appreciation) may be stronger among boys with high AES. The relations between such social media interactions and negative outcomes may be stronger among girls with high AES. We posed the following research questions (Rqs):

RQ1: Do the relations between receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media (RQ1a), exposure to BoPo social media content (RQ1b), BoPo social media content posting behavior (RQ1c), on the one hand, and adolescents’ body appreciation (RQ1a1, RQ1b1, RQ1c1), self- objectification (RQ1a2, RQ1b2, RQ1c2), internalization of appearance ideals (RQ1a3, RQ1b3, RQ1c3), and appearance comparisons with peers (RQ1a4, RQ1b4, RQ1c4) on the other hand, differ according to adolescents’ sex and AES levels?

We controlled for body mass index (BMI) and age because these factors can impact the relations between social media use and body image (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2003). To distinguish content-specific relations from relations due to adolescents’ overall levels of social media use, we controlled for general social media use.

Methods

Procedure and Participants

This study was ethically approved by the Institutional Review Board. In March 2018, adolescents were recruited through schools across Belgium. Principals of 81 high schools were invited to participate; 10 schools agreed to participate. Participants and their parents provided active consent. Participating adolescents completed a survey during school hours in the presence of a researcher.

Of the 1,844 targeted adolescents, 710 participated (adolescents who did not receive active parental consent, who did not provide active consent, or who were not present in class during data collection not participating), and 690 were included in the analytical sample (older than 18 years were removed). Participants were between 14 and 18 years old (M = 16.41, SD = 0.98); 55.96% were girls.

Measures

New measures were developed to assess exposure and posting behaviors related to BoPo social media content. Two researchers reviewed these scales and cognitive interviews were conducted with nine adolescents who reviewed the survey and confirmed that the items were interpreted as intended. These adolescents also reviewed the other scales. An appendix with the scales and all the items can be found on https://osf.io/xe4bt.

Receiving Positive Appearance Comments From Peers on Social Media

The positive appearance-related commentary subscale was used (Feltman & Szymanski, 2018). Respondents responded to five items such as I receive positive comments about my body on social media, using a five-point Likert scale (1 = almost never, 5 = almost always). Principal component analyses (PCAs) revealed one reliable factor; explained variance (EV) = 70.16%, eigenvalue = 3.51, α = .89. An average higher score indicated more frequent reception of positive appearance comments from peers.

Exposure to Body Positive Social Media Content

Participants indicated how frequently they were exposed to the following content on different social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram): (1) pictures with captions such as “love your own body” and (2) textual posts with hashtags such as “#nofilter”. Answer options on these two items ranged from: 1 = (almost) never to 7 = multiple times in a day. A new variable was created by averaging the two item scores (r = .70, p < .001). Higher scores indicated more frequent exposure to BoPo content on social media.

Body Positive Social Media Content Posting Behaviors

Participants indicated how frequently they posted the following on different social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram): (1) pictures with captions such as “love your own body” and (2) textual posts with hashtags such as “#nofilter.” Answer options ranged from: 1 = (almost) never to 7 = multiple times in a day. A new variable was created by averaging the two item scores (r = .71, p < .001). Higher scores indicated more frequent BoPo social media content posting.

Body Appreciation

The body appreciation scale (Avalos et al., 2005) was used whereby participants rated the extent to which they agreed with 11 items such as “I respect my body”. Answer options ranged from: 1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree. The PCA revealed one factor, EV = 58.75%, eigenvalue = 6.46, α = .92. Average higher scores indicated higher levels of body appreciation.

Self-Objectification

An adapted version of the self-objectification scale (Noll & Frederickson, 1998) was employed (Vandenbosch & Eggermont, 2014). Participants indicated how important they found 12 appearance- and competence-related attributes in their bodies from: 1 = least important to 10 = most important. Following prior procedures (Maes et al., 2019; Vandenbosch & Eggermont, 2014), a PCA was conducted separately for boys and girls. This procedure was chosen because body ideals tend to differ across sex (Calogero et al., 2010). For boys, the PCA revealed an appearance (EV = 40.54%, eigenvalue = 4.86) and competence-based (EV = 13.39%, eigenvalue = 1.61) factor. The item health was deleted due to a low factor loading (= .38). The PCA was redone, and results indicated an appearance- (seven items, EV = 43.63%, eigenvalue = 4.80, α = .85) and competence-based (four items, EV = 14.37%, eigenvalue = 1.58, α = .78) factor.

For girls, the first PCA revealed an appearance- (EV = 11.81%, eigenvalue = 1.42) and competence-based (EV = 37.88%, eigenvalue = 4.55) factor. The items skin tone and health were deleted due to low factor loadings. The PCA was redone, and the results revealed an appearance- (three items, EV = 14.07%, eigenvalue = 1.41, α = .70) and competence-based (seven items, EV = 43.63%, eigenvalue = 4.36, α = .79) factor. Self-objectification was computed as the difference between the mean scores of appearance- and competence-based attributes (range from −9 to 9). Positive scores indicated valuing appearance over competence.

Internalization of Appearance Ideals

The internalization subscale of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire 3 (SATAQ-3) was used (Thompson et al., 2004), which consisted of six items such as I compare my body with the bodies of models, influencers, and celebrities on social media. Answer options ranged from: 1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree. The PCA revealed one factor, EV = 82.49%, eigenvalue = 4.95, α = .96. An average higher score indicated a higher degree of the internalization of appearance ideals.

Appearance Comparison With Peers

The body comparison orientation subscale was used (Thompson et al., 1991) in which participants indicated the extent to which they agreed with five items, such as I compare my body shape to that of my peers on a scale from: 1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree. The PCA revealed one factor, EV = 71.81%, eigenvalue = 3.59, α = .90. An average higher score indicated higher levels of appearance comparisons with peers.

Socio-Demographics

Participants indicated their age, sex assigned at birth (0 = boy, 1 = girl), height and weight, which were used to calculate their BMIs (kg/m2).

General Social Media Use

Participants indicated from 1 = 0 hours to 10 = the whole day how much time they typically spend on Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, WhatsApp, and websites like YouTube on regular weekdays and weekend days. The PCA revealed one factor, EV = 43.94%, eigenvalue = 4.39, α = .85. A composite score for general social media use was calculated in line with previous research (Vangeel et al., 2020).

Aesthetic Hypersensitivity (AES)

The AES scale was used (Pluess et al., 2018). Participants responded using a scale ranging from: 1 = I totally disagree to 7 = I totally agree, to evaluate the following four items: I notice it when small things have changed in my environment; I like nice smells; Some music can make me really happy and I like nice tastes. The PCA revealed one factor, EV = 44.64%, eigenvalue = 1.79, α = .56. An examination of an improvement in the reliability suggested an increase when deleting the item I notice it when small things have changed in my environment. The new factor included the three remaining items, EV = 56.04%, eigenvalue = 1.68, α = .60. This alpha is acceptable given the low number of items in the scale (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). Average higher scores indicated higher levels of AES.

Analytical Strategy

Data were analyzed using SPSS because the available regression techniques allow for the modeling of three-way interactions in one analysis. Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations were calculated. No multicollinearity problems occurred according to the variance inflation factor and tolerance (Field, 2013). BoPo social media content posting behaviors exceeded the acceptable range of skewness and kurtosis (Kline, 2011). Bootstrapping with 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs; n = 1,000) was applied to handle non-normal data. Bootstrapped B-values, SE, p-values, and CIs are reported in the results. Different models were tested for the main relationships (H1–H2) and the two- and three-way interactions because main effects are not allowed to be interpreted in a regression analysis that also includes interaction effects (Field, 2013).

To test the associations between the different interactions with positive body-focused content and body appreciation (H1a–H1c), a stepwise regression was conducted with body appreciation as the dependent variable. Control variables (i.e., sex, age, BMI, general social media use) were included in block 1. Receiving positive appearance comments from peers, exposure to BoPo content and BoPo posting behaviors were entered in block 2. The same procedure was used with self-objectification, internalization of appearance ideals, as well as appearance comparisons with peers as the dependent variable in separate analyses (H2). By running separate analyses per dependent variable, type I errors may occur. To control for multiple comparisons with different outcome variables, the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) correction for false discovery rate (FDR) was used, following the procedure outlined by Rudgard et al. (2021). This correction is statistically more powerful than familywise error control procedures (e.g., Bonferroni correction). An FDR of 5% was applied.

To test the two-way interactions, new regression models were run (with centered variables) as main effects cannot be interpreted in a regression analysis that also include interaction terms (Field, 2013). For H3, body appreciation was entered as a dependent variable. Control variables were entered in block 1 and receiving positive appearance comments from peers, exposure to BoPo social media content and BoPo social media content posting behaviors were entered in block 2. The two-way interaction terms with the three body-focused social media variables and AES were entered in block 3. Centering procedures were applied as it reduces potential multicollinearity problems. A similar procedure was used for H4 with self-objectification, the internalization of appearance ideals, and appearance comparisons with peers as dependent variables. BH correction was applied.

With respect to the three-way interactions with body appreciation (RQ1a1–RQ1c1), all possible two-way interactions were entered in block 3, and all three-way interactions with the social media variables × AES × sex were entered in block 4. The same procedure was followed with self-objectification (RQ1a2–RQ1c2), internalization of appearance ideals (RQ1a3–RQ1c3), and appearance comparisons with peers (RQ1a4–RQ1c4) each as the dependent variable. BH correction was applied to control for multiple testing of the four dependent variables. If three-way interactions were significant, slope difference tests were performed. All continuous variables part of the interaction were centered in all moderation analyses.

All data, syntaxes, and tables with all results (see supplementary tables S1–S2) can be found on OSF at https://osf.io/b8efc.

Results

Table 1 shows zero-order correlations and descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Zero-Order Correlations and Descriptive Statistics.

|

|

1. |

2. |

3. |

4. |

5. |

6. |

7. |

8. |

9. |

10. |

11. |

12. |

M (SD) |

|

Age |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16.41 (0.98) |

|

Sex |

−.07 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BMI |

.13** |

−.01 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20.74 (3.03) |

|

General social media use |

−.12** |

.15*** |

.11* |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.74 (1.60) |

|

Receiving positive appearance comments from peers |

−.04 |

.32*** |

−.03 |

.27*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.80 (0.99) |

|

Exposure to BoPo social media content |

.04 |

.25*** |

.06 |

.16*** |

.23*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.15 (1.73) |

|

BoPo social media content posting behaviors |

−.11** |

.09* |

.12** |

.17*** |

.14** |

.20*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

1.27 (0.76) |

|

Body appreciation |

.05 |

−.31*** |

−.17*** |

−.20*** |

−.05 |

−.17*** |

−.12** |

— |

|

|

|

|

4.68 (1.02) |

|

Internalization of appearance ideals |

.07 |

.33*** |

.05 |

.09* |

.25*** |

.25*** |

.04 |

−.35*** |

— |

|

|

|

3.11 (1.47) |

|

Appearance comparisons with peers |

−.02 |

.24*** |

.04 |

.03 |

.18*** |

.23*** |

.02 |

−.46*** |

.59*** |

— |

|

|

3.63 (1.37) |

|

Self-objectification |

.06 |

.55*** |

.04 |

.12** |

.29*** |

.23*** |

−.03 |

−.31*** |

.44*** |

.37*** |

— |

|

0.19 (1.84) |

|

AES |

.07 |

.18*** |

−.05 |

−.07 |

.13** |

.16*** |

−.08 |

.08 |

.16*** |

.16*** |

.20*** |

— |

5.87 (0.82) |

|

Note. *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05. |

|||||||||||||

Main Associations Between Positive Body-Focused Social Media Content and Body Image (H1–H2)

Adolescents’ Positive Body Images (H1)

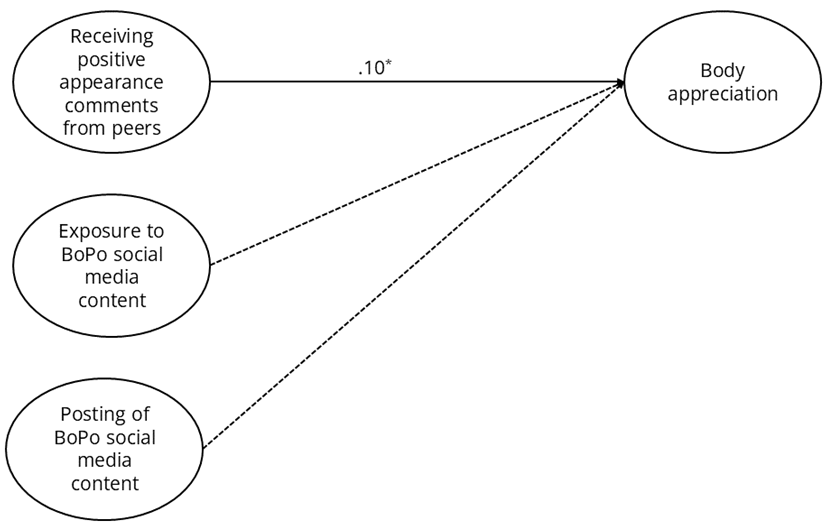

With respect to H1 (Table 2), the model with body appreciation as dependent variable was significant, F(7,583) = 15.12, p < .001.Receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media positively related to body appreciation, β = .10, t = 2.35, B = 0.10, p = .032, 95% CI [0.007, 0.191]; (after BH correction), supporting H1a. H1b and H1c could not be supported because exposure to BoPo social media content, β = −.07, t = −1.67, B = −0.04, p = .137, 95% CI [−0.094, 0.012], and BoPo social media content posting behaviors, β = −.05, t = −1.16, B = −0.07, p = .336, 95% CI [−0.224, 0.067], were not related to body appreciation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Results of the Main Associations Between Interactions With Social Media Content

and Adolescents’ Positive Body Images.

Note. The first value reflects the standardized coefficient (beta). *p <.05. Dashed lines are non-significant paths.

Adolescents’ Negative Body Images (H2)

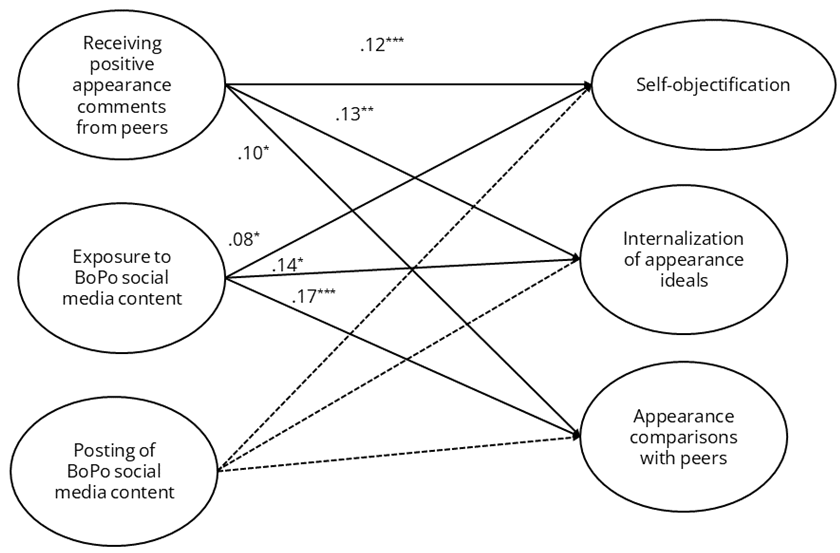

Fig. 2 shows the results summary. Pertaining to H2 (Table 2), the model with self-objectification as dependent variable was significant, F(7,581) = 43.66, p < .001. In line with H2a1–H2b1, receiving positive appearance comments from peers, β = .12, t = 3.25, B = 0.23, p < .001, 95% CI [0.095, 0.352], and exposure to BoPo social media content, β = .08, t = 2.21, B = 0.09, p = .036, 95% CI [0.008, 0.167], positively related to self-objectification (after BH correction), whereas BoPo social media content posting behavior was a significant predictor but became insignificant after BH correction, β = −.10, t = −2.90, B = −0.29, p = .020, 95% CI [−0.534, −0.033]; (contradicting H2c1).

Figure 2. Results of the Main Associations Between Interactions With Social Media Content

and Adolescents’ Negative Body Images.

Note. The first value reflects the standardized coefficient (beta). *p <.05, **p <.01, ***p < .001. Dashed lines are non-significant paths.

Table 2. Results of the Stepwise Regression Analysis for Body Appreciation, Internalization of Appearance Ideals,

Appearance Comparisons of Peers and Self-Objectification.

|

|

Body Appreciation |

Internalization of Appearance Ideals |

Appearance Comparisons With Peers |

Self-Objectification |

||||||||

|

Predictor |

β |

Boot B (SE) |

|

β |

Boot B (SE) |

|

β |

Boot B (SE) |

|

β |

Boot B (SE) |

|

|

Step 1: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age |

.03 |

0.03 (.04) |

|

.09* |

0.13 (.06)* |

|

−.01 |

−0.01 (.06) |

|

.10** |

0.18 (.07)** |

|

|

Sex |

−.28*** |

−0.58 (.08)*** |

|

.32*** |

.94 (.11)*** |

|

.23*** |

0.63 (.11)*** |

|

.56*** |

2.07 (.12)*** |

|

|

BMI |

−.16*** |

−0.05 (.02)** |

|

.04 |

0.02 (.02) |

|

.05 |

0.02 (.02) |

|

.03 |

0.02 (.02) |

|

|

SMU |

−.14*** |

−0.09 (.03)** |

|

.04 |

0.04 (.04) |

|

−.02 |

−0.02 (.04) |

|

.05 |

0.06 (.05) |

|

|

R2 |

|

|

.14 |

|

|

.11 |

|

|

.05 |

|

|

.32 |

|

F |

|

|

23.96*** |

|

|

18.95*** |

|

|

8.60*** |

|

|

68.41*** |

|

Step 2: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive AC |

.10* |

0.10 (.05)* |

|

.13** |

0.20 (.07)** |

|

.10* |

0.14 (.06)* |

|

.12** |

0.23 (.07)*** |

|

|

BoPo SME |

−.07 |

−0.04 (.03) |

|

.14*** |

0.20 (.04)** |

|

.17*** |

0.14 (.04)*** |

|

.08* |

0.09 (.04)* |

|

|

BoPo SMP |

−.05 |

−0.07 (.08) |

|

−.03 |

−0.07 (.10) |

|

−.04 |

−0.09 (.10) |

|

−.10** |

−0.29 (.13)* |

|

|

R2 |

|

|

.15 |

|

|

.14 |

|

|

.08 |

|

|

.34 |

|

ΔR2 |

|

|

.01 |

|

|

.04 |

|

|

.04 |

|

|

.03 |

|

F |

|

|

15.12*** |

|

|

14.78*** |

|

|

8.66*** |

|

|

43.66*** |

|

ΔF |

|

|

2.99* |

|

|

8.28*** |

|

|

8.32*** |

|

|

7.55*** |

|

Note. SMU = social media use, Positive AC = receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media, BoPo SME = social media exposure to BoPo content, BoPo SMP = BoPo social media content posting behavior. Significance levels ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05. Coefficients in bold remain significant with Benjamini-Hochberg correction. |

||||||||||||

The results further revealed that the model with internalization of appearance ideals as dependent variable was significant, F(7,590) = 14.78, p < .001. In line with H2a2 and H2b2, receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media, β = .13, t = 3.13, B = 0.20, p = .003, 95% CI [0.061, 0.329], and exposure to BoPo social media content, β = .14, t = 3.45, B = 0.12, p = .003, 95% CI [0.045, 0.196], positively related to internalization of appearance ideals (after BH correction), whereas BoPo social media content posting behavior did not, β = −.03, t = −0.75, B = −0.06, p = .498, 95% CI [−0.259, 0.120]; (contradicting H2c2; Table 2, Fig. 2).

The model with appearance comparisons with peers as the outcome variable was significant, F(7,590) = 8.66, p < .001. In line with H2a3–H2b3, receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media, β = .10, t = 2.26, B = 0.14, p = .037, 95% CI [0.010, 0.263], and exposure to BoPo social media content, β = .17, t = 4.14, B = 0.14, p < .001, 95% CI [0.067, 0.204], positively related to appearance comparisons (after BH correction), whereas BoPo social media content posting behavior did not, β = −.04,

t = −1.01, B = −0.09, p = .383, 95% CI [−0.279, 0.143]; (contradicting H2c3; Table 2, Fig. 2).

The Moderating Role of AES (H3–H4)

Adolescents’ Positive Body Image (H3)

Regarding the model with body appreciation as dependent variable, no support emerged for H3a–H3c, as AES did not moderate the relations between the independent variables and adolescents’ body appreciation1 (Supplementary Materials at https://osf.io/xe4bt).

Adolescents’ Negative Body Images (H4)

Pertaining to the model with self-objectification as dependent variable, no support emerged for H4a1, H4b1, or H4c1, as AES did not moderate the relations between the independent variables and self-objectification (Supplementary Materials at https://osf.io/xe4bt).2

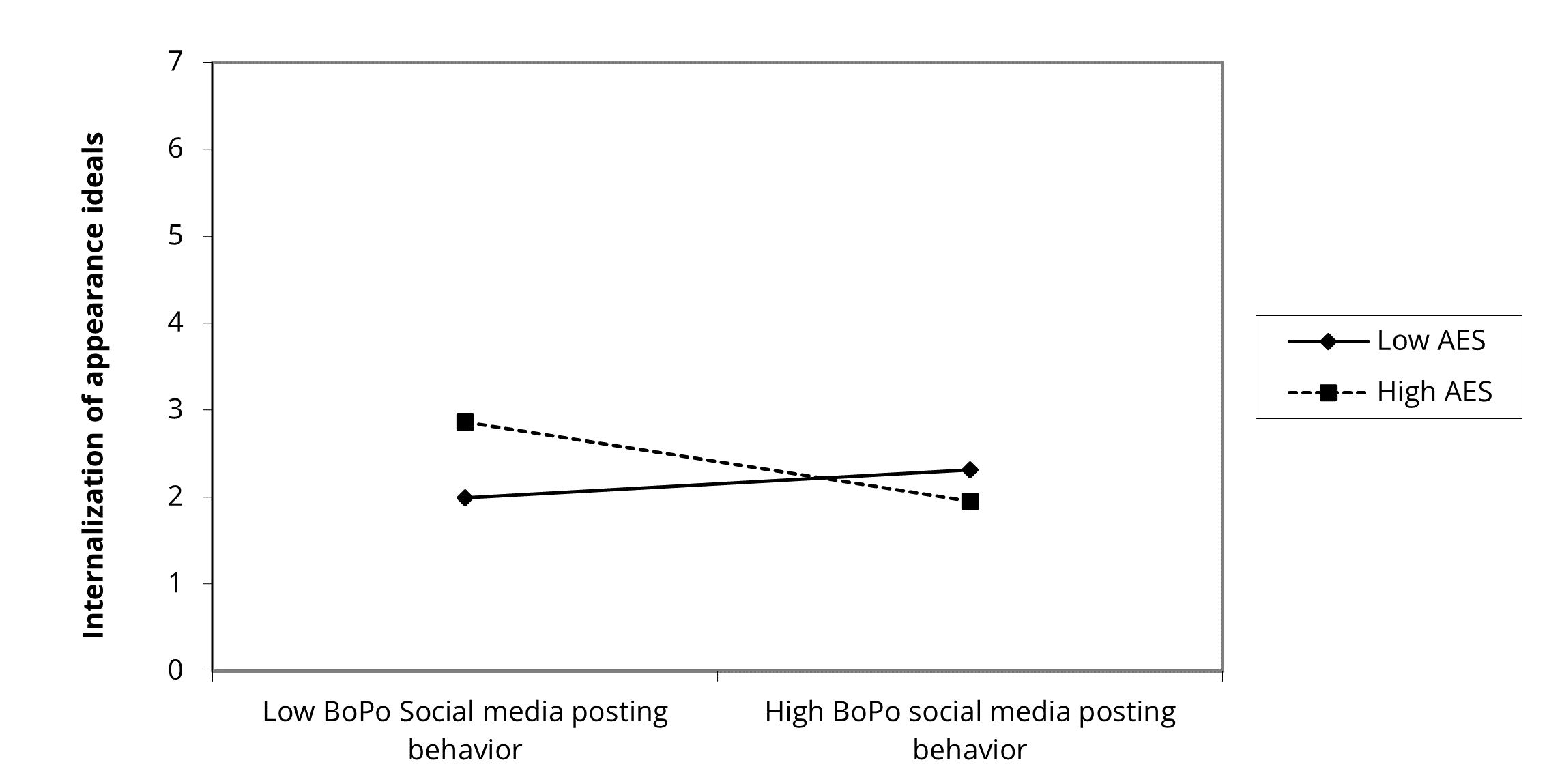

The results indicated that the model with the interaction terms and internalization of appearance ideals as dependent variable was significant, F(11,586) = 10.40, p < .001 (Supplementary Materials at https://osf.io/xe4bt).3 No support was found for H4a2 and H4b2, as AES did not moderate the relations between receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media or exposure to BoPo social media content and internalization of appearance ideals. On the other hand, relative to H4c2, AES moderated the relations between BoPo social media content posting behaviors and internalization of appearance ideals, β = −.12, t = −2.68, B = −0.31, p = .006, 95% CI [−0.544, −0.059]; (after BH correction; Table 3). A simple slopes test was performed (Fig. 3). Contradicting our hypothesis about the direction of the moderator (H4c2), a negative association between BoPo social media content posting behavior and internalization of appearance ideals was found for adolescents with high AES, B = −0.45, t = −2.50, p = .013, but no significant association was observed for adolescents with low AES, B = 0.16, t = 1.42, p = .156.

Figure 3. Results of the Moderating Role of Aesthetic Hypersensitivity

and Adolescents’ Internalization of Appearance Ideals.

Note. AES = aesthetic hypersensitivity.

Table 3. Results of the Moderating Role of Aesthetic Hypersensitivity

in Adolescents’ Internalization of Appearance Ideals.

|

Predictor |

β |

Boot B (SE) |

|

|

Step 1: |

|

|

|

|

Age |

.08* |

0.12 (.06)* |

|

|

Sex |

.32*** |

0.94 (.11)*** |

|

|

BMI |

.04 |

0.02 (.02) |

|

|

SMU |

.04 |

0.04 (.04) |

|

|

R2 |

|

|

.11 |

|

F |

|

|

18.67*** |

|

Step 2: |

|

|

|

|

Positive AC |

.13** |

0.19 (.07)** |

|

|

BoPo SME |

.13** |

0.11 (.04)** |

|

|

BoPo SMP |

−.02 |

−0.04 (.10) |

|

|

AES |

.07 |

0.13 (.07) |

|

|

R2 |

|

|

.14 |

|

ΔR2 |

|

|

.04 |

|

F |

|

|

13.29*** |

|

ΔF |

|

|

7.12*** |

|

Step 3: |

|

|

|

|

Positive AC XAES |

.02 |

0.04 (.08) |

|

|

BoPo SME XAES |

.03 |

0.03 (.05) |

|

|

BoPo SMP XAES |

−.12** |

−0.31 (.12)** |

|

|

R2 |

|

|

.15 |

|

ΔR2 |

|

|

.01 |

|

F |

|

|

10.40*** |

|

ΔF |

|

|

2.43 |

|

Note. SMU = general social media use, Positive AC = receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media, BoPo SME = social media exposure to BoPo content, BoPo |

|||

Relative to the model with appearance comparisons with peers as dependent variable, no support was demonstrated for H4a3, H4b3, or H4c3, as AES did not moderate the relations between the independent variables and appearance comparisons (Supplementary Materials at https://osf.io/xe4bt).4

Combined Moderating Roles of Aesthetic Hypersensitivity and Sex (RQ1)

Adolescents’ Positive Body Images

Regarding RQ1a1, RQ1b1, and RQ1c1, no significant three-way interactions occurred between sex × AES × the three types of positive social media interactions and adolescents’ body appreciation (Supplementary Materials at https://osf.io/xe4bt).

Adolescents’ Negative Body Images

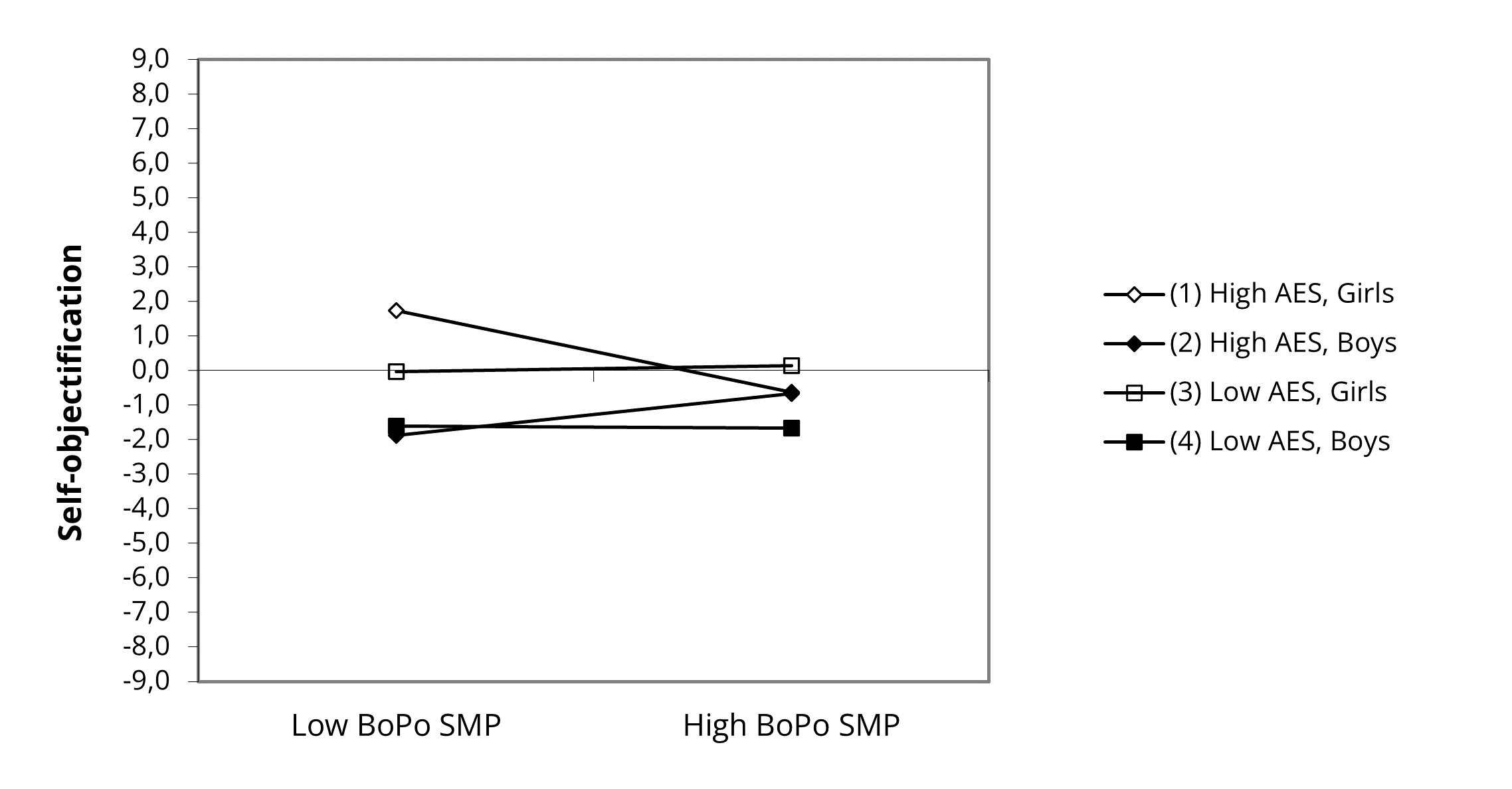

Concerning the three-way interactions with self-objectification as dependent variable and relevant to RQ1a2 and RQ1b2, sex × AES did not moderate the relations between (1) receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media and self-objectification or (2) exposure to BoPo social media content and self-objectification (Supplementary Materials at https://osf.io/xe4bt). Regarding RQ1c2 (Table 4), support was found for the moderating roles of sex × AES in the associations between BoPo social media content posting behaviors and self-objectification, β = −.18, t = −3.31, B = −0.95, p = .002, 95% CI [−1.604, −0.271]; (after BH correction). Slope differences tests were performed (Fig. 4). The conditional relations revealed that the negative association between BoPo social media content posting behavior and self-objectification was only significant among girls with high AES, B = −1.19, t = −5.05, p < .001, but not among (1) girls with low AES, B = 0.08, t = 0.36, p = .720, (2) boys with low AES, B = −0.03, t = −0.15, p = .879, or (3) boys with high AES, B = 0.60, t = 1.51, p = .131.

Figure 4. Results of the Three-Way Interaction of Aesthetic Hypersensitivity With Sex in the Relations

Between BoPo Posting Behavior and Self-Objectification.

Note. AES = aesthetic hypersensitivity, BoPo SMP = Body positive social media content posting behavior.

Table 4. Results of the Moderating Role of Aesthetic Hypersensitivity

and Gender in Adolescents’ Self-Objectification.

|

Self-objectification |

|||

|

Predictor |

β |

Boot B (SE) |

|

|

Step 1: |

|

|

|

|

Age |

.10** |

0.19(.07)** |

|

|

Sex |

.55*** |

2.06(.12)** |

|

|

BMI |

.03 |

0.02(.03) |

|

|

SMU |

.05 |

0.06(.05) |

|

|

R2 |

|

|

.32 |

|

F |

|

|

67.27*** |

|

Step 2: |

|

|

|

|

Positive AC |

.11** |

0.21(.07)** |

|

|

BoPo SME |

.07* |

0.08(.04) |

|

|

BoPo SMP |

−.10** |

−0.27(.14)* |

|

|

AES |

.08* |

0.18(.09)* |

|

|

R2 |

|

|

.34 |

|

ΔR2 |

|

|

.03 |

|

F |

|

|

38.38*** |

|

ΔF |

|

|

6.78*** |

|

Step 3: |

|

|

|

|

Positive AC XAES |

.02 |

0.05(.09) |

|

|

BoPo SME XAES |

.00 |

0.01(.05) |

|

|

BoPo SMP XAES |

−.07 |

−0.23(.23) |

|

|

Positive AC X sex |

.09 |

0.25(.14) |

|

|

BoPo SME X sex |

.05 |

0.07(.08) |

|

|

BoPo SMP X sex |

−.11 |

−0.42(.27) |

|

|

AES X sex |

.04 |

0.15(.19) |

|

|

R2 |

|

|

.35 |

|

ΔR2 |

|

|

.02 |

|

F |

|

|

21.94*** |

|

ΔF |

|

|

2.40* |

|

Step 4: |

|

|

|

|

Positive AC X AESX sex |

.01 |

0.02(.18) |

|

|

BoPo SME X AESX sex |

.02 |

0.03(.11) |

|

|

BoPo SMP X AESX sex |

−.18*** |

−0.95(.34)** |

|

|

R2 |

|

|

.36 |

|

ΔR2 |

|

|

.01 |

|

F |

|

|

19.18*** |

|

ΔF |

|

|

3.75* |

|

Note. SMU = general social media use, Positive AC = social media exposure to positive appearance comments from peers, BoPo SME = social media exposure to BoPo content, BoPo SMP = BoPo social media content posting behavior, AES = aesthetic hypersensitivity. Significance levels ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05. Coefficients in bold remain significant with Benjamini-Hochberg correction. |

|||

For RQ1a3, RQ1b3, and RQ1c3, no significant three-way interactions took place between sex × AES × the three types of social media interactions and adolescents’ internalization of appearance ideals (Supplementary Materials at https://osf.io/xe4bt).

For RQ1a4, RQ1b4, and RQ1c4, no significant three-way interactions occurred between sex × AES × the three types of social media interactions and adolescents’ appearance comparisons with peers (Supplementary Materials at https://osf.io/xe4bt).

Discussion

This study provides insights into the relations between three types of interactions with positive body-focused content on social media (i.e., receiving positive appearance comments from peers, exposure to BoPo content, and BoPo content posting behavior) and adolescents’ positive and negative body images (i.e., body appreciation, self-objectification, internalization of appearance ideals, and appearance comparisons with peers).

First, the findings confirm that some “positive” body-focused content may have a dual role in relation to adolescents’ body image. Specifically, receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media, positively related to a positive body image component (body appreciation) as well as negative body image components (self-objectification, internalization of appearance ideals, and appearance comparisons with peers).

Although this is one of the first studies that found associations between positive and negative body images and receiving positive appearance comments from peers on social media in the same research, the findings align with those of studies that reported correlations between receiving such comments and negative (Kim, 2020) as well as positive body image components (Wang et al., 2020). As prior studies drew on female adult samples, our study extends their insights by including adolescents and boys in the sample.

Second, exposure to BoPo social media content positively related to all negative body image components, i.e., self-objectification, internalization of appearance ideals, and appearance comparisons with peers. These findings align with insights derived from the Tripartite Model (Thompson et al., 1999) and social cognitive theory of mass communication (Bandura, 2001) as body image messages from role models may shape adolescents’ body image components in line with the messages they have viewed.

Our findings also align with studies that also found positive relations between exposure to BoPo social media content and negative body image components among adult women (Cohen, Fardouly, et al., 2019; Vendemia et al., 2021). Together, this research and the prior findings suggest that, although positive body-focused content aims to evoke a positive body image, its relations are more complex in practice. Cues that may undermine the content’s positivity have been identified in experimental research as factors responsible for the negative effects, such as the presence of sexualization or self-promotion practices (Brathwaite & DeAndrea, 2021; Vendemia et al., 2021). Practitioners who are helping adolescents who struggle with a negative body image may thus not only discuss and contextualize appearance ideal content but also BoPo content on social media. They should thus be aware that BoPo posts on social media also contain potentially harmful elements and therefore be cautious when they, for instance, recommend what type of content adolescents should engage with on social media as even positive intended content may be harmful.

Furthermore, no significant associations between exposure to BoPo social media content and body appreciation were indicated, but such associations were found for receiving appearance comments from peers. Research may consider that exposure to BoPo social media content is less powerfully related to body appreciation than receiving comments on one’s appearance from peers. This may be related to the intended audience for the content. Whereas receiving appearance comments is targeted toward the adolescent and his/her own body, BoPo social media content involves other individuals’ bodies and promotes love toward “everyone’s” bodies. Potentially, the unique focus on one’s own body is necessary so that relations occur with a positive body image in users.

Third, no significant links to posting BoPo content on social media were observed when considering the overall sample. Three explanations may exist for these null findings. More precisely, adolescents who post BoPo content may receive positive appearance feedback from their peers on social media if they post specific messages (e.g., focus on natural appearance without make-up). Zero-order correlations indeed reveal a positive association between posting BoPo content and receiving positive appearance comments from peers. Such feedback may play a more pivotal role in shaping adolescents’ positive and negative body image components as compared to merely posting BoPo content. This reasoning aligns with prior research who also indicated that positive feedback from peers on social media can affect well-being outcomes (Valkenburg et al., 2006). This study can also partially confirm this reasoning; while positive appearance feedback from peers correlated with adolescents’ positive and body image outcomes, posting BoPo content did not. In addition, BoPo posting behaviors occurred relatively rarely; adolescents, on average, indicated to almost never post BoPo content. Potentially, these behaviors occurred not sufficiently enough to evoke meaningful relations in one’s body image development.