The role of social norms for online prosocial & antisocial behavior among adolescents in Singapore

Vol.20,No.1(2026)

Although features of social media such as visibility and quantifiability might intensify processes of peer influence, there still is little systematic research on these mechanisms in the online context, especially when it comes to prosocial behavior. This study systematically investigated normative influences on adolescents’ antisocial and prosocial online behavior. We applied an extesnded version of the Theory of Normative Social Behavior to analyze how and under which conditions descriptive and injunctive norms influence social online behavior. We conducted an online survey among 420 Singaporean adolescents aged 14–17 years (M = 15.84, SD = 1.10) and applied structural equation modeling. For antisocial online behavior, we found that stronger perceived antisocial behavior of friends (descriptive norms) was related to more online antisocial behavior for those adolescents who also perceived a higher social approval of such behavior (injunctive norms). This relationship was further strengthened for adolescents who had more positive outcome expectations towards antisocial actions, both for descriptive and injunctive norms. For prosocial online behavior, we found that a stronger perception of friends behaving accordingly (descriptive norms) was directly related to more online prosocial behavior. Stronger positive outcome expectations towards prosocial online behavior were also directly related to more prosocial actions. The study underscores a complex interplay of norms and outcome expectations particularly for understanding antisocial online behavior, while suggesting other theoretical mechanisms might be more relevant for prosocial online behavior.

social media; descriptive norms; injunctive norms; theory of social normative behavior; peer communication; prosocial behavior; antisocial behavior; adolescents

Ruth Wendt

Department of Media and Communication, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich, Munich, Germany

Ruth Wendt is an Associate Professor for communication science at the Department of Media and Communication at Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich. She has completed her PhD in communication science at the University of Münster. Her work focuses on the use and effects of digital media among children, adolescents and families as well as research on digital literacy.

Vivian Hsueh Hua Chen

Department of Media and Communication, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Vivian Hsueh Hua Chen is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Media and Communication at the Erasmus University Rotterdam. She also is an Associate Professor at the Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. She holds a PhD in Human Communication from Arizona State University. Her research interests include how technology brings changes in communication behaviors and facilitates negative and positive outcomes.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Álvarez-Benjumea, A., & Winter, F. (2018). Normative change and culture of hate: An experiment in online environments. European Sociological Review, 34(3), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy005

Arbuckle, J. L. (1996). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In G. A. Marcoulides & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), Advanced Structural Equation Modeling (pp. 243–277). Psychology Press.

Armstrong-Carter, E., & Telzer, E. H. (2021). Advancing measurement and research on youths’ prosocial behavior in the digital age. Child Development Perspectives, 15(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12396

Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love or outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00126

Butzer. B., & Kuiper, N. A. (2006). Relationships between the frequency of social comparisons and self-concept clarity, intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety, and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(1), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.017

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Chun, J., Lee, J., Kim, J., & Lee, S. (2020). An international systematic review of cyberbullying measurements. Computers in Human Behavior, 113, Article 106485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106485

Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., pp. 151–192). McGraw-Hill.

Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A., & Reno, R. R. (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 24, 201–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60330-5

Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7.

Del Rey, R., Casas, J. A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P., Thompson, F., Barkoukis, V., Tsorbatzoudis, H., Brighi, A., Guarini, A., Pyzalski, J., & Plichta, P. (2015). Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 141–147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.065

den Hamer, A., Konjin, E. A., & Keijer, M. G. (2014). Cyberbullying behavior and adolescents’ use of media with antisocial content: A cyclic process model. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(2), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0307

East, K., McNeill, A., Thrasher, J. F., & Hitchman, S. C. (2021). Social norms as a predictor of smoking uptake among youth: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of prospective cohort studies. Addiction, 116(11), 2953–2967. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15427

Erreygers, S., Vandebosch, H., Vranjes, I., Baillien, E., & De Witte, H. (2017). Nice or naughty? The role of emotions and digital media use in explaining adolescents’ online prosocial and antisocial behavior. Media Psychology, 20(3), 374–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2016.1200990

Erreygers, S., Vandebosch, H., Vranjes, I., Baillien, E., & De Witte, H. (2018). Development of a measure of adolescents’ online prosocial behavior. Journal of Children and Media, 12(4), 448–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2018.1431558

Erreygers, S., Vandebosch, H., Vranjes, I., Baillien, L., & De Witte, H. (2019). Feel good, do good online? Spillover and crossover effects of happiness on adolescents' online prosocial behavior. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20, 1241–1258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0003-2

Ferenczi, N., Marshall, T. C., & Bejanyan, K. (2017). Are sex differences in antisocial and prosocial Facebook use explained by narcissism and relational self-construal? Computers in Human Behavior, 77, 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.033

Festl, R. (2016). Perpetrators on the internet: Analyzing individual and structural explanation factors of cyberbullying in school context. Computers in Human Behavior, 59, 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.017

Festl, R., & Quandt, T. (2016). The role of online communication in long-term cyberbullying involvement among girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(9), 1931–1945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0552-9

Fikkers, K. M., Piotrowski, J. T., Lugtig, P., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2016). The role of perceived peer norms in the relationship between media violence exposure and adolescents’ aggression. Media Psychology, 19(1), 4–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2015.1037960

Geber, S., & Hefner, D. (2019). Social norms as communicative phenomena: A communication perspective on the theory of normative social behavior. Studies in Communication and Media, 8, 6–28. https://doi.org/10.5771/2192-4007-2019-1-6

Geber, S., Baumann, E., & Klimmt, C. (2019). Where do norms come from? Peer communication as a factor in normative social influences on risk behavior. Communication Research, 46(5), 708–730. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217718656

Giletta, M., Choukas-Bradley, S., Maes, M., Linthicum, K., Card, N., & Prinstein, M. J. (2021). A meta-analysis of longitudinal peer influence effects in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 147(7), 719–747 https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000329

Hoffner, C. A., & Bond, B. J. (2022). Parasocial relationships, social media, & well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, Article 101306, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101306.

House, B. R. (2018). How do social norms influence prosocial development? Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.011

Hurrelmann, K., & Bauer, U. (2018). Socialisation during the life course. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315144801

Kiesner, J., Cadinu, M., Poulin, F., & Bucci, M. (2002). Group identification in early adolescence: Its relation with peer adjustment and its moderator effect on peer influence. Child Development, 73(1), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00400

Lysenstøen, C., Bøe, T., Hjetland, G. J., & Skogen, J. C. (2021). A review of the relationship between social media use and online prosocial behavior among adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 579347. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.579347

Meeus, A., Beyens, I., Geusens, F., Sodermans, A. K., & Beullens, K. (2018). Managing positive and negative media effects among adolescents: Parental mediation matters—but not always. Journal of Family Communication, 18(4), 270–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2018.1487443

Monahan, K. C., Steinberg, L., & Cauffman, E. (2009). Affiliation with antisocial peers, susceptibility to peer influence, and antisocial behavior during the transition to adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1520–1530. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017417

Moor, L., & Anderson, J. R. (2019). A systematic literature review of the relationship between dark personality traits and antisocial online behaviours. Personality and Individual Differences, 144, 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.027

Nesi, J., Choukas-Bradley, S., & Prinstein, M. J. (2018). Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: Part 2—application to peer group processes and future directions for research. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review, 21(3), 295–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-018-0262-9

Ouvrein, G., Pabian, S., Machimbarrena, J. M., Erreygers, S., De Backer, C. J. S., & Vandebosch, H. (2019). Setting a bad example: Peer, parental, and celebrity norms predict celebrity bashing. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(7), 937–961. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431618797010

Pabian, S., & Vandebosch, H. (2014). Using the theory of planned behaviour to understand cyberbullying: The importance of beliefs for developing interventions. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 11(4), 463–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2013.858626

Postmes, T., Spears, R., & Lea, M. (2000). The formation of group norms in computer-mediated communication. Human Communication Research, 26(3), 341–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2000.tb00761.x

Prinstein, M. J., Borelli, J. L., Cheah, C. S. L., Simon, V. A., & Aikins, J. W. (2005). Adolescent girls’ interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(4), 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.676

Real, K., & Rimal, R. N. (2007). Friends talk to friends about drinking: Exploring the role of peer communication in the theory of normative social behavior. Health Communication, 22(2), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230701454254

Rimal, R. N., & Real, K. (2003). Understanding the influence of perceived norms on behaviors. Communication Theory, 13(2), 184–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00288.x

Rimal, R. N., & Real, K. (2005). How behaviors are influenced by perceived norms: A test of the theory of normative social behavior. Communication Research, 32(3), 389–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650205275385

Rösner, L., & Krämer, N. C. (2016). Verbal venting in the social web: Effects of anonymity and group norms on aggressive language use in online comments. Social Media + Society, 2(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116664220

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Sasson, H., & Mesch, G. (2014). Parental mediation, peer norms and risky online behavior among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.025

Sasson, H., & Mesch, G. (2017). The role of parental mediation and peer norms on the likelihood of cyberbullying. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 178(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2016.1195330

Shmargard, Y., Coe, K., Kenski, K., & Rains, S. A. (2021). Social norms and the dynamics of online incivility. Social Science Computer Review, 40(3), 717–735. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439320985527

Smahel, D., Machackova, H., Mascheroni, G., Dedkova, L., Staksrud, E., Ólafsson, K., Livingstone, S., & Hasebrink, U. (2020). EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries. EU Kids Online. https://doi.org/10.21953/lse.47fdeqj01ofo

Spears, R., & Lea, M. (1994). Panacea or panopticon? The hidden power in computer-mediated communication. Communication Research, 21(4), 427–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365094021004001

Spears, R., & Postmes, T. (2015). Group identity, social influence, and collective action online. In S. S. Sundar (Ed.), The handbook of the psychology of communication technology (pp. 23–46). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118426456.ch2

Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1089/1094931041291295

Telzer, E. H., van Hoorn, J., Rogers, C. R., & Do, K. T. (2018). Social influence on positive youth development: A developmental neuroscience perspective. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 54, 215–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acdb.2017.10.003

Uhls, Y. T., Ellison, N. B., & Subrahmanyam, K. (2017). Benefits and costs of social media in adolescence. Pediatrics, 140(Supplement_2), S67–S70. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1758E

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2011). Online communication among adolescents: An integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.020

van Hoorn, J., van Dijk, E., Meuwese, R., Rieffe, C., & Crone, E. A. (2016). Peer influence on prosocial behavior in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(1), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12173

Vilanova, F., Beria, F. M., Costa, A. B., & Koller, S. H. (2017). Deindividuation: From Le Bon to the social identity model of deindividuation effects. Cogent Psychology, 4(1), Article 1308104. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2017.1308104

Vismara, M., Girone, N., Conti, D., Nicolini, G., & Dell’Osso, B. (2022). The current status of cyberbullying research: A short review of the literature. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 46, Article 101152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2022.101152.

Wright, M. F., & Li, Y. (2011). The associations between young adults’ face-to-face prosocial behaviors and their online prosocial behaviors. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(5), 1959–1962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.04.019

Wu, S., Lin, T.-C., & Shih, J.-F. (2017). Examining the antecedents of online disinhibition. Information Technology & People, 30(1), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-07-2015-0167

Authors’ Contribution

Ruth Wendt: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, project administration, data curation; writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. Hsueh Hua Vivian Chen: conceptualization, methodology, project administration; writing—original draft, writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

October 17, 2023

Revisions received:

November 25, 2024

June 30, 2025

November 14, 2025

Accepted for publication:

November 26, 2025

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

Adolescents increasingly look for peer status and peer approval, which can intensify their social comparison and feedback-seeking and thus make them more susceptible to peer influence (Butzer & Kuiper, 2006; Prinstein et al., 2005). Social media platforms enable constant peer interaction, and thus facilitate the exploration of various forms of self-presentations and social comparisons (Uhls et al., 2017). However, up to now, only a few studies have investigated the role of peer influence on adolescents’ online behavior. Nesi et al. (2018) highlighted that the specific features of social media might have brought changes in peer influence for adolescents. First, there are numerous possibilities for exposure to positive and negative peer behavior on social media. Second, they assume that adolescents are exposed to risky behaviors on social media more often than in offline context due to the high availability to risky content. Third, they proposed that on social media, (prosocial and antisocial) behavior can be reinforced in a measurable manner (e.g., by the number of likes & comments). They conclude that peer influence on social media might be more intensive compared to the offline settings (Nesi et al., 2018).

Most of the previous research on peer influence focused on deviant forms of adolescents’ behavior, such as substance use (Giletta et al., 2021), risky behavior (e.g., Sasson & Mesch, 2014, 2017) or antisocial behavior (e.g., Monahan et al., 2009). Antisocial online behavior covers different forms of deviant behaviors (or the intentional absence of acceptable social behaviors) that are perpetrated online and have negative consequences (online of offline) for the receivers (Moor & Anderson, 2019). One of the most studied phenomena in this context is the perpetration of cyberbullying, including different antisocial components such as insults, deception, and social exclusion (see e.g., Chun et al., 2020). Recently, Telzer et al. (2018) argued for the importance to examine peer influence on adolescents’ prosocial behavior. The performance of prosocial online behavior might be particularly desirable for users since such actions are highly visible to others and might be valued by a broad audience (Armstrong-Carter & Telzer, 2021). Erreygers et al. (2018) broadly defined online prosocial behavior as “voluntary behavior carried out in an electronic context with the intention of benefitting particular others or promoting harmonious relations with others” (p. 449). This includes a broad range of activities, ranging from liking a friends’ post, comforting, and helping another person, to sharing resources and information. Some studies revealed that adolescents behave prosocially more often than antisocially online (Erreygers et al., 2017, 2018). This indicates that adolescents are exposed to negative as well as positive social behaviors on social media.

The present study advances current research by investigating how peer influence is related to adolescents’ online antisocial and prosocial behaviors. One of the major mechanisms of peer influence is normative influence. Normative influence was found to be prominent during adolescence, since peer norms offer orientation, stabilization, and security during this volatile stage of life (Hurrelmann & Bauer, 2018). On social media, adolescents can easily observe the social behavior of their friends (descriptive norms) as well as their (dis)approval of certain behavior (injunctive norms), for example in form of likes and comments. This study applies an extended version of the Theory of Normative Social Behavior (TNSB) to examine how these social norms influence both prosocial and antisocial behaviors on social media among adolescents in Singapore.

Adolescents’ Social Norms & Online Behavior

Social norms are defined as “rules and standards that are understood by members of a group, and that guide and/or constrain social behavior without the force of laws. [They] emerge out of interactions with others; they may or may not be stated explicitly, and any sanctions for deviating from them come from social networks, not the legal system” (Cialdini & Trost, 1998, p.152). There is a long research tradition showing that social norms influence an individual’s behavior through two underlying normative processes. Descriptive norms refer to the perceived prevalence of a behavior in an important reference group, while injunctive norms refer to the perception that important referents expect oneself to comply with a certain behavior (Rimal & Real, 2003, 2005). In other words, norms are distinguished between what is typically done (descriptive norms) and what is typically approved or not approved (injunctive norms; Cialdini et al., 1991). Both concepts are measured based on individuals’ perceptions.

While social norms were found to be driving mechanisms for a range of different individual behaviors (e.g., East et al., 2021), their role in the online context still needs further investigation. Previous studies have confirmed that social identity can also develop in anonymous online groups through the numerous available options of socially interacting with each other (e.g., Postmes et al., 2000). One of the most prominent approaches in this context is the Social Identity Model of Deindividuation Effects (SIDE; Spears & Lea, 1994). This model proposes that in deindividuation situations collective aspects of a person’s personality are more salient than individual differences. This results in an increasing influence of the norms of this group in which the individual situationally is part of. SIDE effects are especially expected to be prevalent in online environments as underlying characteristics of these contexts such as anonymity and physical distance may induce deindividuation (Vilanova et al., 2017). However, even among preexisting groups (e.g., friendship groups) new ways of interacting might appear when entering an online context, affecting the existing group dynamics and the social identity of the group members (Postmes et al., 2000). Thus, there is the need to investigate social norms in the context of online behavior, especially considering the strengthening role of adolescents’ perceived social identity.

Previous studies have investigated the influence of social norms on users’ online antisocial behavior. Looking at user comments, Shmargard et al. (2021) found that repeated uncivil comments are more likely to be performed by a person when their initial uncivil comment was reinforced by descriptive norms (i.e., uncivility in surrounding comments) and injunctive norms (i.e., uncivil comments receiving upvotes). They also found that injunctive norms were reinforced by descriptive norms. In an experimental study, Rösner and Krämer (2016) confirmed that adult users are more aggressive in their replies when more aggressive wording was observed in comments of their peers. This conformity to an aggressive social norm was stronger in anonymous online environments. Álvarez-Benjumea and Winter (2018) found that participants in an online experiment were less likely to engage in hate speech when prior hate content was censored compared to when the person expressing hate speech was informally verbally sanctioned. Relying on these findings, they concluded that descriptive norms might be especially relevant in the context of hate speech. In terms of toxic online disinhibition, Wu et al. (2017) confirmed a particular important influence of perceived injunctive norms.

None of the studies described above focused on adolescents for whom normative influences might be strong. A few studies compared the role of parents and peers when analyzing the influence of social norms on adolescents’ risky and antisocial online behavior. These studies consistently revealed the heavy influence of peers, although there were also interactional links between parental and peer influence. Sasson and Mesch (2014), for example, showed that supervision led to less risky behavior, but this increased with perceptions of peer approval. Ouvrein et al. (2019) found that peer norms were most influential, as compared to parental and celebrity norms, in shaping both mild and severe forms of individual bashing behavior towards celebrities. Fikkers et al. (2016) conducted a study with young adolescents aged 10 to 14 years and found an indirect effect of media violence on their aggression via perceived approval of aggression by their friends. This indirect effect was stronger for youngsters who perceived more peer aggression, thus, they perceived stronger descriptive norms.

In general, research on adolescents’ prosocial online behavior is still less prominent than research on forms of their antisocial behavior. In a recent systematic review, Lysenstøen et al. (2021) found that only two (quantitative) studies explicitly addressed the relationship between social media use and online prosocial behavior. Both studies showed a positive relationship between the use of social media (Erreygers et al., 2017) and more generally, the use of digital media (Erreygers et al., 2019) and the performance of online prosocial behavior. Erreygers et al. (2017) showed that adolescents who experienced more (negative as well as positive) emotions performed and received more prosocial online behavior. Meeus et al. (2018) examined the role of parental mediation and confirmed that autonomy-supportive forms of mediation were positively related to offline prosocial behavior through increased prosocial media exposure. In contrast, the role of peer influence on adolescents’ online prosocial behavior is still an academic void. Findings regarding offline prosocial behavior already confirmed that peer feedback (van Hoorn et al., 2016) and social norms (House, 2018) are related to children’s and adolescents’ performance of different kinds of prosocial behavior. We expect similar mechanisms of peer influence for adolescents’ online prosocial behavior. Summarizing the findings, both parts of social norms were found to be influential in explaining adolescents’ online antisocial and offline prosocial behavior. However, only a few studies directed the focus on the complex interplay between descriptive and injunctive norms when explaining certain online activities. This issue is addressed by the present study as explained in the next chapter.

The Theory of Normative Social Behavior (TNSB)

One previously applied approach addressing the influence of social norms on aspects of online behavior is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). According to this established model from the field of social psychology, individual behavior can be predicted by a person’s perceived behavioral control and behavioral intentions, which, in turn, are influenced by a person’s attitudes, perceived behavioral control and subjective norms. These individual cognitions are again shaped by a range of behavioral beliefs (Ajzen, 1991). Previous studies, for example, confirmed that the focused injunctive norms were positively related to adolescents’ behavioral intention to perpetrate cyberbullying (Pabian & Vandebosch, 2014), but did not predicted their actual perpetration behavior (Festl, 2016). While TPB might be a valuable approach when focusing on norm-building aspects, it neglects the interplay between injunctive and descriptive norms to explain adolescents’ behavior.

The present paper thus applied TNSB that was first developed in the field of health communication to explain a person’s risky behavior (Rimal & Real, 2003, 2005) and has been widely used to investigate the influence of both parts of social norms on individual behavior. TNSB states that descriptive norms directly influence a person’s behavior, while injunctive norms strengthen the relationship between descriptive norms and risk behavior. In addition, two other concepts are considered to influence the behavioral influence of descriptive norms: (1) individual’s outcome expectations, which – in brief – can be described as a person “believe that the behavior will produce positive outcomes” (Rimal & Real, 2005, p. 395) as well as (2) the perceived group identity, which can be defined as “individuals’ aspirations to emulate referent others and the extent to which they perceive similarity between themselves and those referents” (Rimal & Real, 2005, p. 395).

TNSB contends that perceived descriptive norms directly influence individuals’ risky behaviors, while perceived injunctive norms primarily strengthen (perceived social approval) or weaken (perceived social disapproval) this relationship (Rimal & Real, 2005). In line with Geber and Hefner (2019), we expected descriptive and injunctive norms to be directly related to adolescents’ social online behavior, since perceived social approval might shape online behavior, even if not many social referents dare to show that kind of behavior. Therefore, the following hypotheses are posed:

H1a: Stronger perceived (H1a1) descriptive & (H1a2) injunctive online prosocial norms are positively related to adolescents’ prosocial online behavior.

H1b: Stronger perceived (H1b1) descriptive & (H1b2) injunctive online antisocial norms are positively related to adolescents’ antisocial online behavior.

In line with TNSB, we assumed injunctive norms to be a relevant moderator of the behavioral influence of descriptive norms. In their extended model, Geber and Hefner (2019) also assumed a moderation effect of descriptive norms strengthening the behavioral influence of injunctive norms. Since we would use the same statistical interaction to test this prediction, we didn’t include it as a separate hypothesis.

H2a: The positive relationship between perceived descriptive online prosocial norms & adolescents’ prosocial online behavior is stronger for adolescents with more pronounced injunctive online prosocial norms.

H2b: The positive relationship between perceived descriptive online antisocial norms & adolescents’ antisocial online behavior is stronger for adolescents with more pronounced injunctive online antisocial norms.

As an additional moderating factor, we analyzed adolescents’ outcome expectations. Thereby, we focused on the social character of outcome expectations, since we looked at the expected enhancement of a person’s popularity and likeability through enacting prosocial or antisocial online behavior. In their extended model, Gerber and Hefner (2019) proposed that social outcome expectations not only strengthen the behavioral influence of descriptive norms, but also of injunctive norms. Therefore, we proposed:

H3a: The positive relationship between perceived (H3a1) descriptive/(H3a2) injunctive online prosocial norms & adolescents’ prosocial online behavior is stronger for adolescents with more positive outcome expectations towards prosocial behavior.

H3b: The positive relationship between perceived (H3b1) descriptive/(H3b2) injunctive online antisocial norms & adolescents’ antisocial online behavior is stronger for adolescents with more positive outcome expectations towards antisocial behavior.

Next, the original and extended model of TNSB by Geber and Hefner (2019) both proposed that a person’s perceived group identity is a norm-moderating factor strengthening the behavioral influence of descriptive (TNSB) and injunctive norms (extended TNSB). This is because social norms are usually tied with a certain social group that is important to the acting person or the specific behavior. We thus predict that:

H4a: The positive relationship between perceived (H4a1) descriptive/(H4a2) injunctive online prosocial norms & adolescents’ prosocial online behavior is stronger for adolescents with a stronger perceived group identity with their friends.

H4b: The positive relationship between perceived (H4b1) descriptive/(H4b2) injunctive online antisocial norms & adolescents’ antisocial online behavior is stronger for adolescents with a stronger perceived group identity with their friends.

Real and Rimal (2007) expanded the original model of the TNSB by incorporating the role of communication that might propagate certain norms, especially about behaviors that primarily occur in a social setting. They found that peer communication can explain additional variance in students’ intention to drink alcohol since this factor moderated the behavioral influence of descriptive norms. Geber and Hefner (2019) refined this communication-based perspective on social norms and proposed an extended model of the TNSB. They argued that “[n]ormative perceptions about referent others’ behaviors and their social approval are probably influenced by observations and communication on social media platforms” (Geber & Hefner, 2019, p. 9). Thus, communication becomes important on social media as users are constantly being evaluated and showing approval or disapproval of each other’s online behaviors. In their extended model, they differentiated between interpersonal communication, described as social interaction between persons occurring online and offline, and media exposure, defined as the extent of person’s encounter with media messages and content (Geber & Hefner, 2019, p. 12). Following the original addition of Real and Rimal (2007), we focused on the role of interpersonal communication that can serve as norm-building or norm-moderating factor, based on Geber and Hefner (2019). As we rely on cross-sectional data, the present study exclusively focused on the norm-moderating role of interpersonal communication defined as the extent to which adolescents talk with peers about their (observed and experienced) social interactions with others on social media. In particular, we examined:

H5a: The positive relationship between perceived (H5a1) descriptive/(H5a2) injunctive online prosocial norms & adolescents’ prosocial online behavior is stronger for adolescents who talk more with their friends about social online behavior.

H5b: The positive relationship between perceived (H5b1) descriptive/(H5b2) injunctive online antisocial norms & adolescents’ antisocial online behavior is stronger for adolescents who talk more with their friends about social online behavior.

Exploratory Analyses & Control Variables

Since previous research already confirmed that prosocial and antisocial online behavior of adolescents co-occurs (Erreygers et al., 2017), we additionally explored whether prosocial norms are related to antisocial online behavior and whether antisocial norms are linked to prosocial behavior. Furthermore, we also exploratory checked if there are mitigating effects of injunctive prosocial norms on the relationship between descriptive antisocial norms and antisocial behavior as well as injunctive antisocial norms on the relationship between descriptive prosocial norms and prosocial online behavior. Finally, we explored if there are mitigating effects of prosocial outcome expectations on the relationship between antisocial norms and antisocial online behavior as well as antisocial outcome expectations on the relationship between prosocial norms and prosocial behavior on social media.

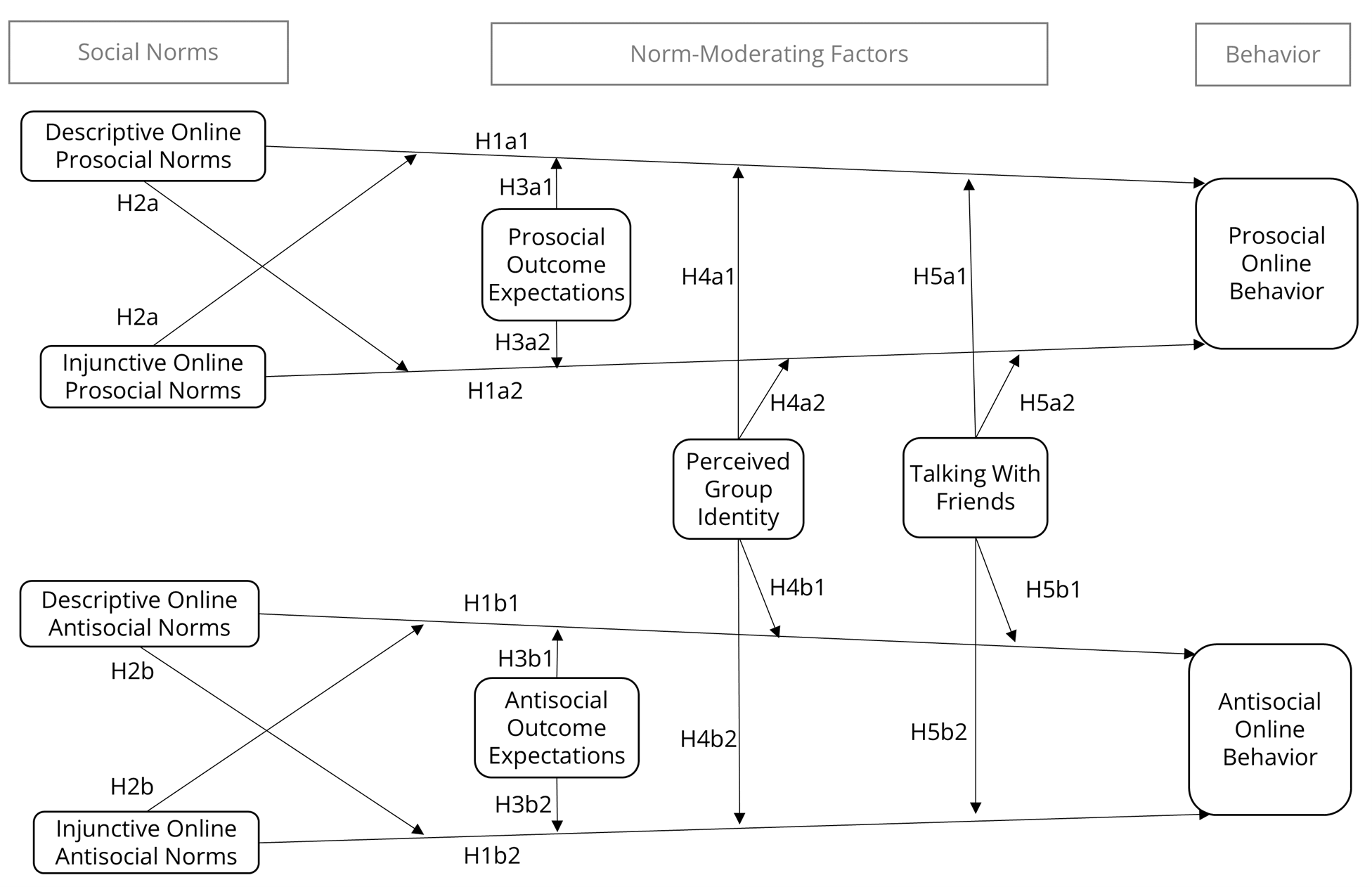

In addition, age, gender, and social media usage were considered in the study as relevant control variables. Previous studies confirmed more involvement in social media use (e.g., Smahel et al., 2020) and antisocial online activities (Vismara et al., 2022) of older compared to younger adolescents. Past studies also showed that female adolescents behave prosocially online more often, while antisocial activities were more pronounced among male adolescents (e.g., Ferenczi et al., 2017; Festl & Quandt, 2016). Finally, usage frequency was positively related to more prosocial (e.g., Wright & Li, 2011) and antisocial (e.g., Festl & Quandt, 2016) online behavior. Additionally, we also controlled for the type of content that adolescents consume while using social media, differentiating between prosocial and antisocial online content (den Hamer et al., 2014). Our overall research model is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Research Model (Adjusted From Geber & Hefner, 2019, p. 19).

Note. Direct effects of outcome expectations, perceived group identity and talking with friends on prosocial and antisocial online behavior as well as covariances between the constructs were modelled but not illustrated for better clarity; effects of antisocial norms on prosocial behavior as well as prosocial norms on antisocial behavior were also exploratory tested, but not illustrated for better clarity.

Methods

Participants & Procedure

An online survey with adolescents in Singapore was conducted in English. The design and instruments of the study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nanyang Technological University. Both parental and participants’ consent were obtained prior to the data collection. The online survey was conducted by the market research institute Qualtrics that collected the data via their online panel in January 2020. Participants recruitment criteria included: age between 14 and 17 years, ability to read English, and use social media currently.

In total, 428 adolescents participated in the study. All respondents successfully passed the two integrated attention checks in the questionnaire. However, we removed eight participants who had a very long response time (more than M + 1*SD). The remaining sample, on average, answered the questionnaire in 10.2 minutes (SD = 8.65). The final sample consisted of 420 adolescents between 14 and 17 years (M = 15.8, SD = 1.1), of which slightly more were female (52%). The majority were of Chinese descent (75.2%), which is representative of the population composition of Singapore. The sample showed a relatively high socioeconomic status based on their housing situation (M = 5.0, SD = 1.6; 1 = HDB 1-room to 8 = Bungalow/Semi-detached/Terrace). The average education level is at ITE-level (M = 4.7, SD = 1.9; 1 = No formal education to 10 = Bachelor’s Degree).

Measures

All items and statistical indices can be found in the Supplement Material (Table A1–A12).

Online Social Norms

All items were adapted from previous studies on social norms (e.g., Geber et al., 2019) and tailored to the context of adolescents’ online social behavior. Participants were asked to indicate their perceived descriptive and injunctive norms regarding prosocial and antisocial behavior on social media, with reference to their group of close friends. All items were answered on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (none of my friends) to 5 (all of my friends). Regarding descriptive norms, the participants answered four items on prosocial behavior (e.g., How many of your friends support other people on social media?), and four items on antisocial behavior (e.g., How many of your friends are nasty to other people on social media?). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)1 showed very acceptable model fits for the descriptive norm constructs; χ2(df) = 34.97 (19), p = .014, CFI = .988, RMSEA = .045, 90% CI [.020, .068]; prosocial: α = .84, M = 3.2, SD = 0.8; antisocial: α = .82; M = 1.8, SD = 0.7).

Regarding injunctive norms, the participants responded to four items on prosocial behavior (e.g., How many of your friends think it is good to help other people on social media?) and four items on antisocial behavior (e.g., How many of your friends think it is okay to deceive other people on social media?). After removing one of the original four items for the prosocial (How many of your friends think it is good to be friendly to other people on social media) and the antisocial (How many of your friends think it is okay to be nasty to other people on social media) subdimension, the CFA2 showed good fit values: χ2(df) = 12.30(8), p = .138, CFI = .996, RMSEA = .036, 90% CI [.000, .073], with satisfying internal reliability for prosocial (α = .86; M = 3.5, SD = 0.8) and antisocial (α = .83; M = 1.7, SD = 0.8) injunctive norms.

Prosocial Online Behavior

Prosocial online behavior was measured with a slightly modified version of the scale developed by Erreygers et al. (2018). Participants were asked to indicate how often they have done 10 actions on social media in the past month, e.g., I helped someone or offered to help, I let someone know that I like something s/he posted (e.g., like something, send a smiley), I comforted/consoled someone. They answered the items on a 5-point frequency scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The CFA confirmed a one-factor solution for prosocial online behavior; χ2(df) = 138.12(35), p < .001, CFI = .954, RMSEA = .084, 90% CI [.069, .099]; α = .90; M = 2.1, SD = 0.7.

Antisocial Online Behavior

Antisocial online behavior measure was adapted from the European Cyberbullying Questionnaire (Del Rey et al., 2015). Participants indicated how often they have done 10 actions3 (e.g., I said nasty things to someone or called them names) on social media in the past month on a 5-point frequency scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The CFA confirmed a one-factor solution, but the fit values could be significantly improved after one item (I spread rumors about someone else) was deleted; χ2(df) = 49.47(27), p = .005, CFI = .955, RMSEA = .063, 90% CI [.034, .090]. The final measure showed an acceptable reliability (α = .81; M = 0.3, SD = 0.4).

Social Outcome Expectations

Positive outcome expectations towards prosocial and antisocial online behavior were measured by a scale from Rimal and Real (2005). The participants responded to four items pertaining to prosocial (e.g., Being nice and helpful on social media makes me likeable) and four items pertaining to antisocial outcome expectations (e.g., Being nasty and mean on social media makes me popular), on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). After deleting one of the four items for prosocial (Being nasty and mean on social media does not make any difference in my life) and antisocial (Being nice and helpful on social media does not make any difference in my life) behavior, the CFA confirmed good fit values; χ2(df) = 6.16(8), p = .629, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .000, 90% CI [.000, .048] with a satisfying internal reliability for prosocial (α = .83; M = 3.7, SD = 0.8) and antisocial (α = .82; M = 1.4, SD = 0.7) outcome expectations.

Perceived Group Identity

Perceived group identity with close friends was measured using a scale by Kiesner et al. (2002). Participants were asked to rate their agreement with eight statements on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A CFA was calculated to check for the original one-factor solution of the construct. The results of the CFA, however, confirmed that two items needed to be deleted (I’m proud to be a part of this group of friends, I’m happy to be described as a member of this group of friends). The CFA further indicated a two-factor solution, one factor describing adolescents’ affective identification with their friends (3 items, e.g., It is important for me to be a part of this group of friends, α = .74; M = 4.2, SD = 0.6), one factor describing negative emotions if they would not be a part of this group (3 items, e.g., If I would not be a part of this group of friends, I would be unhappy, α = .83; M = 3.6, SD = 0.9) to receive acceptable fit values: χ2(df) = 25.84(8), p = .001, CFI = .981, RMSEA = .073, 90% CI [.043, .105]. Although both subdimensions (affective identification, need for identification) were highly correlated (r = .75, p < .001), we decided to use them as two different subscales for the further analyses to consider the found statistical variances.

Talking With Friends About Social Online Behavior

The measure on interpersonal communication should address the extent to which a certain topic – in this specific case socially interacting with others on social media – is discussed among a group of friends. Participants thus were asked to indicate how often they talk with friends about social online behavior answering four statements (e.g., I often talk with my friends about what I do with other people on social media) on a 5-point Likert-scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items were inspired by a measure of Geber et al. (2019) who, among other aspects, investigated the frequency of peer communication (in their original study however addressing driving behavior). The CFA showed that one item (My friends and I talk about how we treat other people on social media) needed to be removed. We found an acceptable value of internal consistency for the final scale (α = .77; M = 3.8, SD = 0.8), with satisfying factor loadings (λ = .66, .77 and .78) for the remaining three items.

Control Variables

Participants’ age, gender, and frequency of social media use were measured. Participants were asked to indicate how often they use social media (including Facebook, Instagram, Social Messengers, & Social Video Platforms) on a 5-point frequency scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (several times a day, M = 4.8, SD = 0.6). To measure respondents’ online content exposure, they indicated how often they watch certain online social contents with friends. They answered five questions related to prosocial content exposure on social media (e.g., When you are together with your friends, how often do you see content on social media (e.g., text, videos, or pictures) showing people helping another person?) and five items related to antisocial content exposure on social media (e.g., When you are together with your friends, how often do you see content on social media (e.g., text, videos, or pictures) showing people destroying someone else's belongings?). The items were adapted from den Hamer et al. (2014) and were all answered on a 5-point frequency scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). The CFA showed acceptable fit values; χ2(df) = 64.64(26), p < .001, CFI = .961, TLI = .946, RMSEA = .064, 90% CI [.044, .085], after one item of the “watching antisocial online contents”-scale (…people who drink (too much) alcohol) was removed. We found acceptable values of internal consistency for the final scales (watching prosocial contents: α = .77; M = 2.1, SD = 0.6; watching antisocial contents: α = .78; M = 1.2, SD = 0.8)

Data Analysis

First, a structural equation modeling was performed for adolescents’ prosocial and antisocial online behavior using latent indicators for the variables. All metric variables were mean centered beforehand. In a second step, we conducted path analyses to test for our proposed moderation effects. Manifest indicators for all variables including the previously formed manifest interaction terms were used. The interaction terms were included one by one in a series of regression models: Model 1: descriptive*injunctive norms, H2a, H2b; Model 2a: descriptive norms*outcome expectations, H3a1 & H3b1; Model 2b: injunctive norms*outcome expectations, H3a2 & H3b2; Model 3a/4a: descriptive norms*affective identification/need for identification, H4a1 & H4b1; Model 3b/4b: injunctive norms*affective identification/need for identification, H4a2 & H4b2; Model 5a: descriptive norms*interpersonal communication, H5a1 & H5b1; Model 5b: injunctive norms*interpersonal communication, H5a2 & H5b2. Additionally, we explored three models, investigating if there might be mitigating effects as well: MEXP1: descriptive*injunctive norms; MEXP2a: descriptive norms*outcome expectations; MEXP2b: injunctive norms*outcome expectations. Interaction effects were illustrated based on a template provided by Dawson (2014). For all models, the proposed control variables (age, gender, social media frequency & online context exposure) were entered as predictors of adolescents’ prosocial and antisocial online behavior.

Since analyses showed skewed data for the dependent variable on online antisocial behavior (skew = 2.64, kurtosis = 8.58), we used the maximum likelihood estimation with robust (Huber-White) standard errors and a scaled test statistic for the main model (MLR; see Rosseel, 2012). The full information maximum likelihood adjustment method (see Arbuckle, 1996) was applied to account for the missing data. We applied established criteria to evaluate the fit of the models: A Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and a Tucker-Lewis-Index (TLI) with values greater than .90 and a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) with values between .05 and .08, indicating an acceptable model (Byrne, 2010). For all analyses, we used R and the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012).

Preregistration

The conducted study was preregistered under the following link: https://aspredicted.org/JFA_MWS. In this preregistration, we specified aspects of our data collection procedure, the hypotheses, our used measures as well as our tested models. During the revision process, the focus of the manuscript changed, now exclusively looking at the influence of online social norms on online social behavior. Due to this focusing, the labeling of the hypotheses changed compared to the preregistration of the study: original H2a & H2b changed to H1a & H1b; original H2c & H2d changed to H2a and H2b; original H2e & H2f changed to H4a & H4b; original H2g & H2h changed to H3a & H3b. When testing the moderation of group identity (now H4a & H4b) and outcome expectations (now H3a & H3b), we added additional hypotheses (H3a2, H3b2, H4a2, H4b2) on the relationship between injunctive norms and respective (prosocial and antisocial) online behavior that were not preregistered. Furthermore, we added four non-preregistered hypotheses (H5a1, H5a2, H5b1, H5b2) that investigated the moderating role of interpersonal communication for the relationship between descriptive and injunctive norms and online behavior. Finally, the preregistered hypotheses H1a-d and H3a-b were not part of the present paper anymore, since we exclusively focused on norm-moderating (not norm-building) factors.

Results

Descriptive Findings on Online Social Behavior

Adolescents showed higher levels of prosocial (M = 2.1, SD = 0.7) than antisocial online behavior; M = 0.3, SD = 0.4; t(df) = 47.22(419), p < .001, d = .77. There were no significant correlations between age and adolescents’ prosocial (r = .07, p = .174) or antisocial online behavior (r = −.07, p = .142). Female adolescents reported less antisocial online behavior (M = 0.3) as compared to male adolescents; M = 0.4; t(df) = 2.72(383), p = .007, d = .44. In contrast, no gender differences were found for prosocial online behavior; t(df) = −.16(417), p = .874. More frequent social media use was positively related to more prosocial (r = .11, p = .002), but not antisocial online behavior (r = .07, p = .127). Finally, prosocial and antisocial online behavior were positively correlated (r = .19, p < .001), which may be indicative of overall greater engagement in social media among some adolescents in the sample. A correlation matrix with all variables can be found in the Supplement Material (Table A13).

The Influence of Social Norms on Online Social Behavior

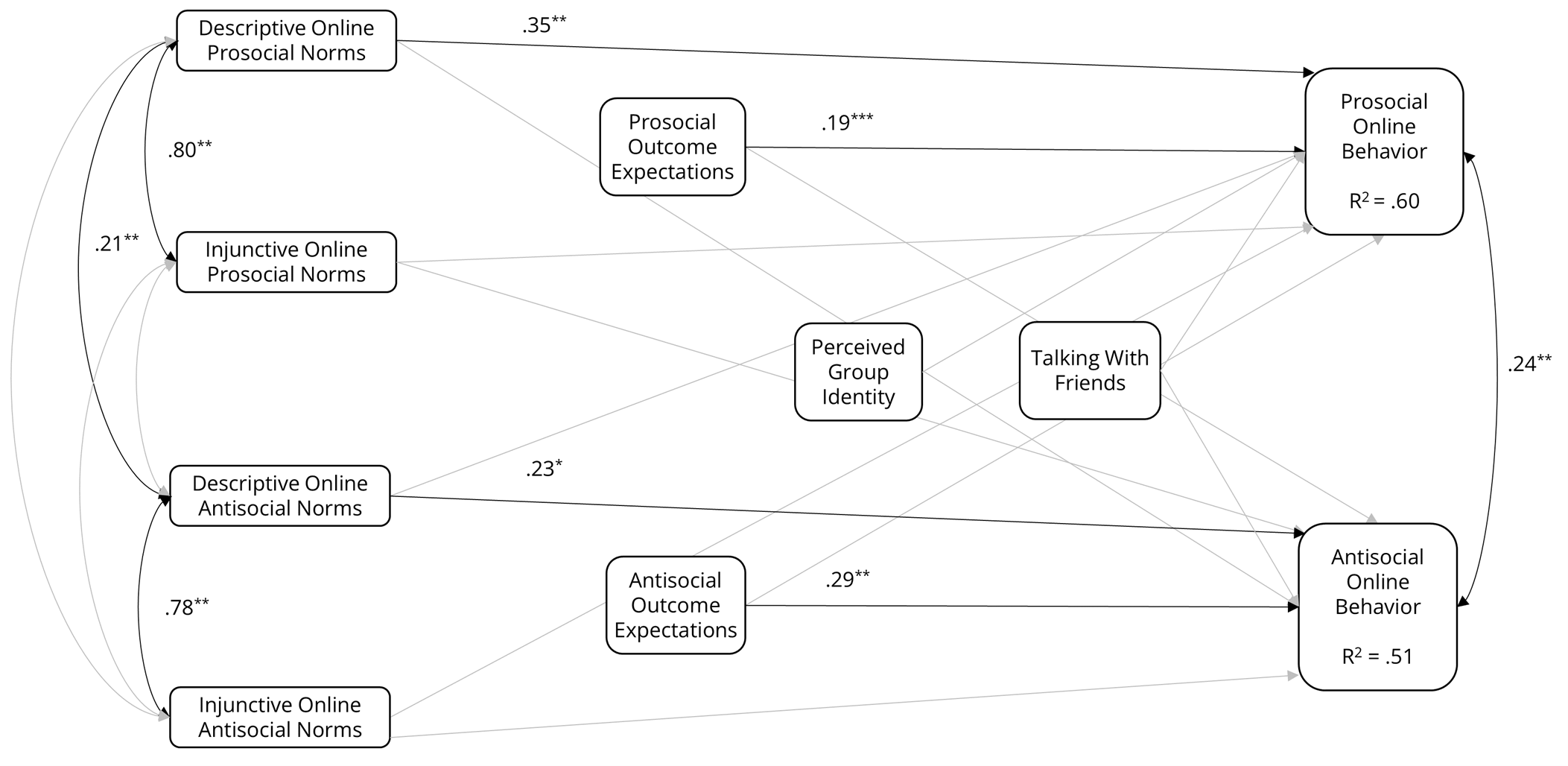

The SEM showed acceptable fit values: χ2(df) = 2494.03(1,593), p < .001, CFI = .919, TLI = .910, RMSEA = .037; SRMR = .053 (see Figure 2). Looking at the control variables, the results showed no effects regarding antisocial online behavior (for details, see Table A16 in the Supplemental Materials). However, we found that adolescents who watched more prosocial online content together with their friends also behaved more prosocially online (β = .21, p = .044).

Figure 2. The Influence of Communication & Social Norms on Online Prosocial & Antisocial Behavior.

Note. A structural equation model was calculated, but the latent structure was omitted for better clarity; significant standardized coefficients of the SEM are indicated; ** = p < .01, * = p < .05; non-significant paths were greyed out; age, gender, frequency of social media use and exposure to prosocial and antisocial online content were controlled in the model as additional predictors of prosocial and antisocial online behavior; covariances between all predictors of social online behavior were calculated but omitted for most of the variables for better clarity (all results can be found in the Supplement Materials); moderation analyses were not included yet, but added at a later step of the analyses (see Table 1).

Looking at the normative influence on behavior, the results showed that stronger perceived descriptive (β = .32, p = .012; H1a1 confirmed) but not injunctive (β = .19, p = .076; H1a2 rejected) prosocial norms were related to more online prosocial behavior. Further, the data confirmed that stronger positive outcome expectations towards prosocial online behavior were directly related to more prosocial online behavior (β = .19, p = .001), while perceived group identity (affective identity: β = −.01, p = .996; need for identification: β = −.01, p = .932) and the frequency of talking with friends about social online behavior (β = .13, p = .132) did not play a significant role.

Further, there was no direct positive influence of antisocial descriptive norms (β = .23, p = .075; H1b1 rejected) and injunctive norms (β = .16, p = .129; H1b2 rejected) on users’ online antisocial behavior. The results, however, confirmed that more positive outcome expectations towards antisocial behavior were directly related to more antisocial behavior on social media (β = .29, p = .001), while – again – group identity (affective identity: β = −.30, p = .082; need for identification: β = .20, p = .152) and talking with friends (β = .07, p = .274) did not play a significant role (see Figure 2).

We also exploratory checked (1) if adolescents’ prosocial social norms and outcome expectations were also related to their antisocial online behavior and (2) if their antisocial social norms and outcome expectations were related to their prosocial behavior on social media. However, neither of these relationships showed a significant result (for details, see Table A16 in the Supplemental Material).

Factors Moderating the Relationship of Social Norms & Online Social Behavior

In a next step, we looked at effects moderating the relationship between online social norms and social behavior. Starting from the basic SEM model described above (this time with manifest indicators4), we calculated 12 models, each focusing on one of the proposed interaction terms (see Table 1). All these models showed acceptable fit values (see Table A17, Supplemental Material).

There was no significant influence of the interaction between prosocial descriptive and injunctive norms on associated prosocial online behavior (Model 1), rejecting H2a (β = −.02, p = .659). In Model 2a and 2b, we investigated whether the interaction of descriptive norms and social outcome expectations (β = −.01, p = .800) as well as the interaction of injunctive norms and outcome expectations (β = −.06, p = .079) positively influenced adolescents’ online prosocial behavior. However, the results did not reveal any significant findings, rejecting hypotheses H3a1 and H3a2. Similarly, the moderating effects of adolescents’ perceived group identity regarding the relationship of descriptive norms and prosocial behavior (Model 3a: affective group identification, β = .01, p = .772; Model 4a: need for identification, β = −.06, p = .149), as well as injunctive norms and prosocial behavior (Model 3b: affective group identification, β = .02, p = .606; Model 4b: need for identification, β = −.00, p = .943) were tested. There were no significant results, rejecting H4a1 and H4a2. Finally, we also found no moderating effects of adolescents’ perceived descriptive (β = −.03, p = .497) and injunctive social norms (β = .02, p = .597) and their frequency of talking with friends on their performance of prosocial online behavior (Model 5a&b), rejecting H5a1 and H5a2 (see Table 1).

Table 1. The Role of Interaction Effects in Explaining Adolescents’ Online Prosocial & Antisocial Behavior.

|

|

Online Prosocial Behavior |

Online Antisocial Behavior |

||||

|

|

B(SE) |

p |

β |

B(SE) |

p |

β |

|

Model 0 (without interactions) |

||||||

|

Female |

−.02(.05) |

.758 |

−.01 |

−.07(.03) |

.036 |

−.08 |

|

Age |

−.02(.02) |

.529 |

−.02 |

−.01(.02) |

.405 |

−.03 |

|

Social Media Use |

.03(.03) |

.290 |

.04 |

.03(.02) |

.037 |

.08 |

|

Exposure to Prosocial Contents |

.17(.05) |

.001 |

.18 |

.04(.03) |

.156 |

.07 |

|

Exposure to Antisocial Contents |

−.04(.04) |

.243 |

−.05 |

.07(.03) |

.020 |

.12 |

|

Prosocial Outcome Expectations (POE) |

.17(.04) |

.000 |

.20 |

.01(.02) |

.970 |

.00 |

|

Antisocial Outcome Expectations (AOE) |

−.05(.04) |

.223 |

−.06 |

.12(.03) |

.001 |

.22 |

|

Affective Identification (AI) |

.02(.05) |

.639 |

.02 |

−.07(.03) |

.019 |

−.13 |

|

Need for Identification (NI) |

−.02(.04) |

.632 |

−.02 |

.04(.03) |

.122 |

.08 |

|

Talking with Friends |

.08(.04) |

.084 |

.09 |

.03(.02) |

.160 |

.06 |

|

DPN |

.26(.06) |

.000 |

.29 |

.01(.03) |

.769 |

.02 |

|

DAN |

.09(.05) |

.087 |

.10 |

.12(.04) |

.001 |

.22 |

|

IPN |

.16(.05) |

.001 |

.20 |

.01(.02) |

.766 |

.01 |

|

IAN |

−.01(.06) |

.823 |

−.02 |

.11(.03) |

.001 |

.21 |

|

Model 1: DPN*IPN & DAN*IAN |

−.01(.03) |

.659 |

−.02 |

.07(.03) |

.018 |

.14 |

|

Model EXP1: DPN*IAN & DAN*IPN |

−.09(.05) |

.078 |

−.09 |

.02(.03) |

.604 |

.03 |

|

Model 2a: DPN*POE & DAN*AOE |

−.01(.03) |

.800 |

−.01 |

.12(.04) |

.005 |

.22 |

|

Model EXP2a: DPN*AOE & DAN*POE |

−.08(.05) |

.154 |

−.07 |

−.03(.03) |

.308 |

−.06 |

|

Model 2b: IPN * POE & IAN*AOE |

−.05(.03) |

.079 |

−.06 |

.13(.03) |

.000 |

.27 |

|

Model EXP2b: IPN*AOE & IAN*POE |

−.04(.04) |

.353 |

−.04 |

−.02(.03) |

.631 |

−.03 |

|

Model 3a: DPN*AGI & DAN*AGI |

.01(.04) |

.772 |

.01 |

−.05(.03) |

.137 |

−.08 |

|

Model 3b: IPN*AGI & IAN*AGI |

.02(.04) |

.606 |

.02 |

−.02(.03) |

.503 |

−.04 |

|

Model 4a: DPN*NFI & DAN*NFI |

−.06(.04) |

.149 |

−.06 |

−.01(.03) |

.614 |

−.02 |

|

Model 4b: IPN*NFI & IAN*NFI |

−.00(.04) |

.943 |

−.00 |

−.00(.03) |

.888 |

−.01 |

|

Model 5a: DPN*TAL & DAN*TAL |

−.03(.04) |

.497 |

−.03 |

.05(.03) |

.096 |

.08 |

|

Model 5b: IPN*TAL & IAN*TAL |

.02(.04) |

.597 |

.02 |

.04(.02) |

.059 |

.08 |

|

Note. We calculated one basic and seven interaction models; the coefficients of the independent and control variables in the various models differed very slightly from the basic model illustrated here; DAN = descriptive antisocial norms; IPN = injunctive prosocial norms; IAN = injunctive antisocial norms; POE = prosocial outcome expectations; AOE = antisocial outcome expectations; AGI = affective group identification; NFI = need for identification; TAL = talking with friends about social online behavior; unstandardized coefficients (B), standard errors (SE), and standardized coefficients (β) are indicated; significant effects are marked bold. |

||||||

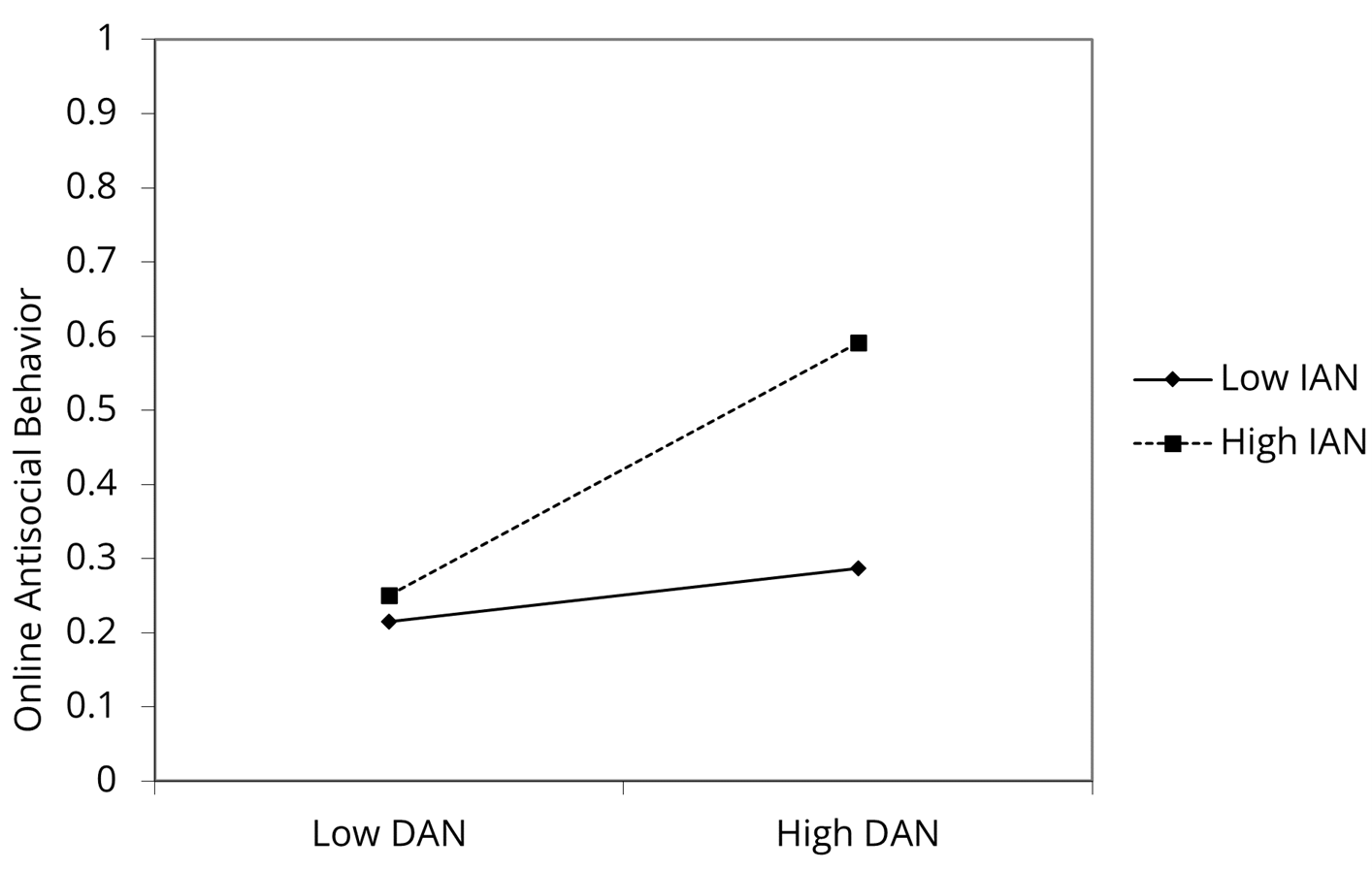

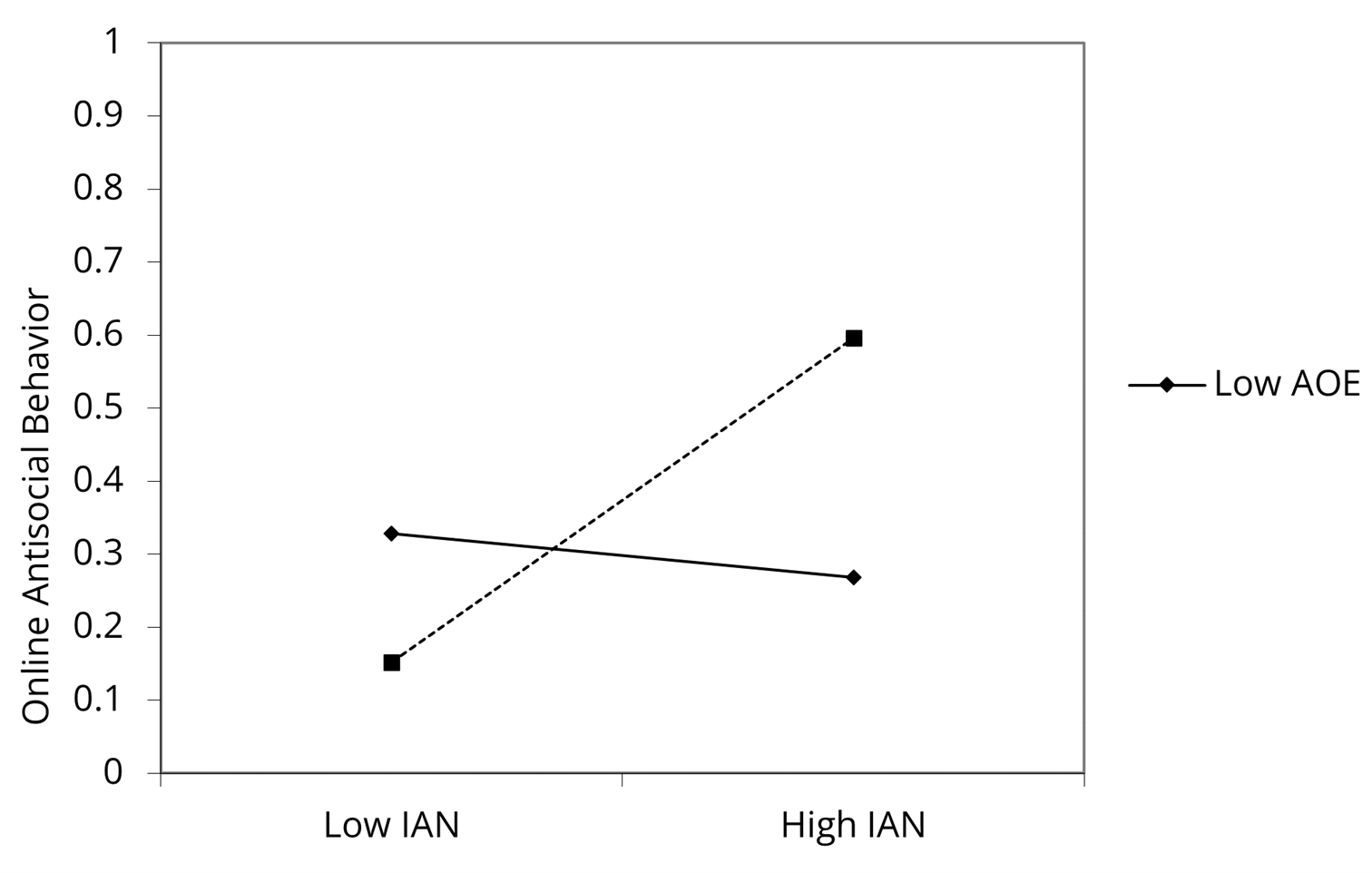

However, the findings revealed a significant influence of the interaction between antisocial descriptive and injunctive norms on antisocial behavior (Model 1: β = .14, p = .018). Thus, the perceived antisocial online behavior of friends was related to more own antisocial behavior for those adolescents who also perceived more social approval of the behavior (supporting H2b, see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Illustration of the Interaction Effect of Descriptive Antisocial Norms & Injunctive Antisocial Norms on Online Antisocial Behavior

Note. DAN = Descriptive Antisocial Norms, IAN = Injunctive Antisocial Norms; for a better illustration, the scale for online antisocial behavior was adjusted to cover its actual values (ranging between 0 and 1).

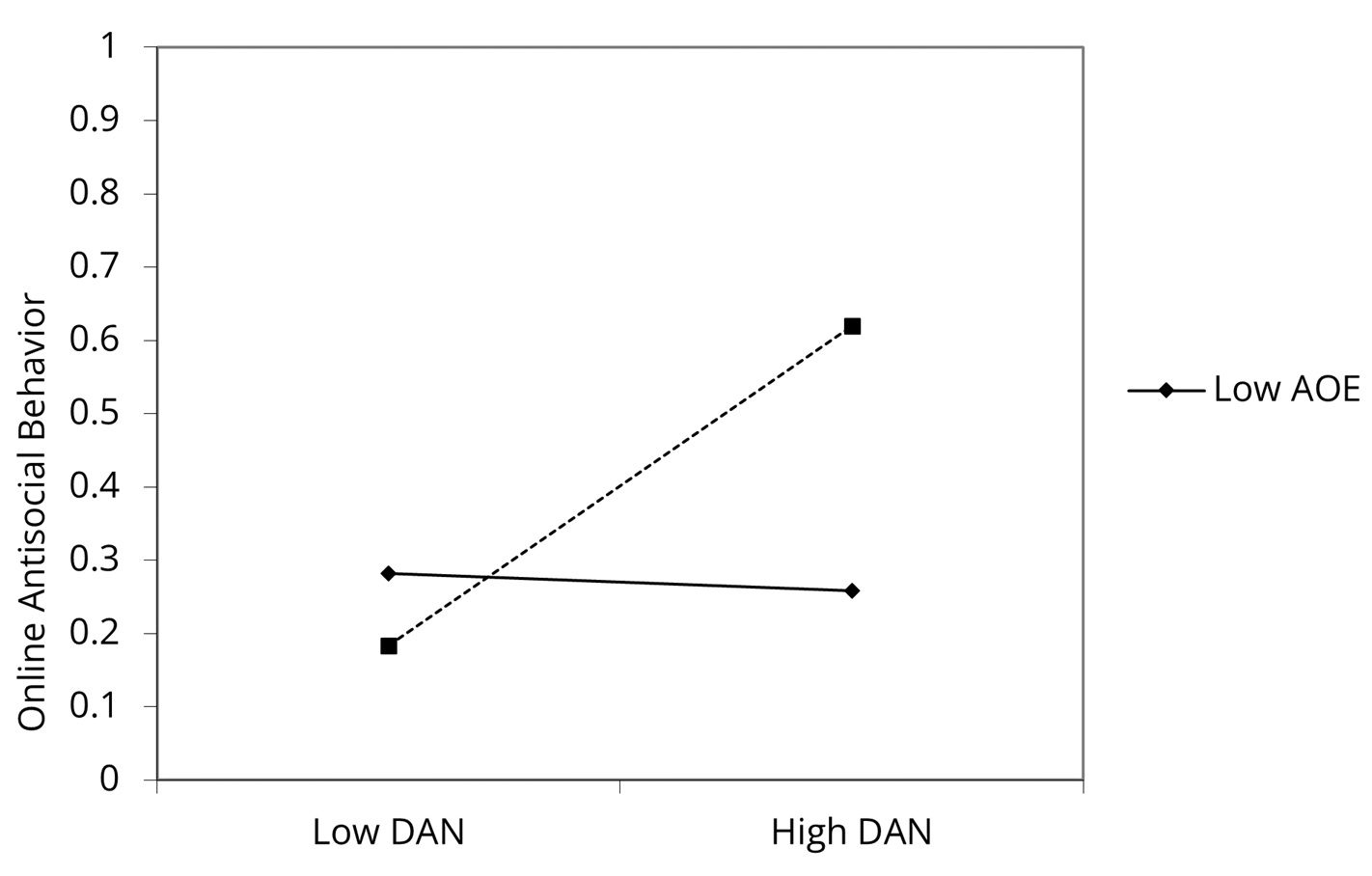

The results further showed a significant influence of the interaction between antisocial outcome expectations and both types of social norms, descriptive (Model 2a: β = .22, p = .005; supporting H3b1) and injunctive (Model 2b: β = .27, p < .001; supporting H3b2) norms. This indicates that the perceived antisocial online behavior of friends was associated with more individual antisocial activities for those adolescents who also had more positive outcome expectations towards the behavior (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Illustration of the Interaction Effect of Descriptive Antisocial Norms & Antisocial Outcome Expectations on Online Antisocial Behavior

Note. DAN = Descriptive Antisocial Norms, AOE = Antisocial Outcome Expectations; for a better illustration, the scale for online antisocial behavior was adjusted to cover its actual values (ranging between 0 and 1).

Accordingly, perceived social approval of antisocial behavior by friends was related to more antisocial activities on social media for those adolescents who also expected more positive consequences of this kind of behavior (see Figure 5). There was no significant influence of the interaction between antisocial norms and perceived group identity on antisocial behavior, neither for affective group identification (Model 3a on descriptive norms: β = −.08, p = .137 & 3b on injunctive norms: β = −.04, p = .503), nor regarding adolescents’ need for identification (Model 4a on descriptive norms: β = −.02, p = .614 & 4b on injunctive norms: β = −.01, p = .888), rejecting H4b1 and H4b2. Finally, we also found no moderating effect regarding perceived descriptive (β = .08, p = .096) and injunctive social norms (β = .08, p = .059) and adolescents’ frequency of talking with friends about social online behavior (Model 5a&b), rejecting H5b1 and H5b2.

Figure 5. Illustration of the Interaction Effect of Injunctive Antisocial Norms & Antisocial Outcome Expectations on Online Antisocial Behavior. Note. IAN = Injunctive Antisocial Norms, AOE = Antisocial Outcome Expectations; for a better illustration, the scale for online antisocial behavior was adjusted to cover its actual values (ranging between 0 and 1).

Note. IAN = Injunctive Antisocial Norms, AOE = Antisocial Outcome Expectations; for a better illustration, the scale for online antisocial behavior was adjusted to cover its actual values (ranging between 0 and 1).

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated mechanisms of peer influence on young users’ antisocial and prosocial online behavior among a sample of Singaporean adolescents aged 14 to 17 years. We tested an extended version of the TNSB to better understand how descriptive and injunctive social norms shape online social behavior in the specific context of social media. We thus enhanced the range of this established theory by applying it to a previously understudied context (norms & social online behavior) and an understudied sample (adolescents). We looked at the different paths of peer influence on adolescents’ online social behavior, focusing on the underlying conditionalities (i.e., effects moderating the relationship between social norms and online behavior). In addition to the established moderators of social norms, behavioral outcome expectations and perceived group identity, we tested interpersonal communication as an additional conditional factor that was claimed (see Geber & Hefner, 2019) and confirmed (see Real & Rimal, 2007) to be relevant in previous research.

In line with basic assumptions of TNSB, stronger perceived descriptive norms were related to more online behavior in the context of prosocial behavior. Contradicting some of the previous literature (see Álvarez-Benjumea & Winter, 2018; Rösner & Krämer, 2016), there were no such direct effects for adolescents’ antisocial online behavior. We also found no direct effects of perceived injunctive norms on prosocial and antisocial online behavior, supporting the original assumption of TNSB. Adolescents thus perform prosocial behaviors online if they perceived that their friends do the same (descriptive norm), while their approval of such behavior (injunctive norm) might not be that decisive. Prosocial online behavior thus can be primarily strengthened by observing such behavior. Similarly, friends’ approval of antisocial behavior was not directly related to the perpetration of such behavior. However, it strengthened the normative influence of descriptive norms. Accordingly, stronger perceived antisocial behavior of friends was related to more online antisocial behavior, if adolescents also perceived a higher social approval of such actions among their friends. Thus, if both types of perceived norms are congruent, it particularly creates a fruitful environment for antisocial actions.

The results further confirmed a central role of adolescents’ outcome expectations. A more positive evaluation of behavioral outcomes directly enhanced the likelihood of enacting prosocial and antisocial behavior. For antisocial online behavior, positive outcome expectations were identified as a relevant conditional factor as well. The perceived antisocial online behavior of friends and their social approval of such a behavior were positively related to more online antisocial behavior if adolescents expected more positive outcomes when behaving antisocially. These results underline the complex interdependencies of perceived norms, outcome expectations and behavior in the online context, where reactions can be observed publicly and in a quantifiable manner (Nesi et al., 2018). However, results showed significant interaction effects regarding antisocial, but not prosocial behavior. Performing antisocial online behavior seems to depend on a complex interplay of personal and social conditions that can reinforce each other.

In contrast, adolescents’ perceived group identity did not play a significant role. It might be due to the measures used in this study. The affective identification and need for identification measures are slightly different to similarity and aspiration as proposed in TNSB (Rimal & Real, 2005). There might be theoretical reasons for the non-significant results as well. The influence of perceived group identity on online behavior has been found to be more pronounced under conditions of anonymity compared to identifiability (e.g., Rösner & Krämer, 2016; Spears & Postmes, 2015). Some social media platforms (e.g., Facebook) make users more identifiable than others (e.g., Twitter, Reddit), so that the influence of perceived group identity may vary depending on the platforms. Brewer (1999) argued that ingroup identification is independent of outgroup hate and that intergroup distinction is primarily motivated by preferring the ingroup and not hating the outgroup members. Thus, the performance of antisocial online behavior (which might be more frequently directed towards outgroup members) does not necessarily depend on adolescents’ perceived group identity. It is thus important to differentiate the targeted social groups under investigation. Yet, the results confirmed a positive relationship between prosocial and antisocial online behavior, indicating that adolescents who show a high level of prosocial online behavior towards their in-group also show more excluding and antisocial behavior towards their out-group (see e.g., Brewer, 1999).

In contrast to the results of Real and Rimal (2007), we did not find that interpersonal communication about online social behavior strengthened the normative influence on prosocial or antisocial behavior on social media. This might be partly due to the used measure of interpersonal communication. Questions were about how often adolescents generally talk with their friends about what happens online with other people, instead of explicitly describing the valence of the online behaviors. Especially for socially undesirable behaviors, more explicit signals in communication (e.g., aggressive, or antisocial wording) might be necessary to know others’ evaluation of the behavior (see Geber et al., 2019). However, this lacking influence of interpersonal communication on online prosocial and antisocial behavior might also be explained by the specific setting of social media. On these platforms, others’ behavior and reactions to certain behavior are usually observed and relate to a very specific context. Generally talking about such behavior (especially without a clear valence) thus might be less relevant in strengthening or weaken such normative influences. Interpersonal communication regarding social online experiences thus might rather be important as norm-building factor informing adolescents to better understand others’ actual behavior and attitudes, thus decreasing the mismatch between and actual and perceived norms (see Geber & Hefner, 2019).

In contrast, we observed the relevance of media exposure: thus, adolescents’ exposure to prosocial and antisocial online contents were positively related to their prosocial, respectively antisocial online behavior. To explain how media exposure might be related to social norms, Geber and Hefner (2019) referred to the Influence of Presumed Influence Model. It argues that people who have high exposure to certain content assume that their important referents also have high exposure to the same messages. They are thus influenced by these contents and messages regarding their expectations and their behavior. This explanation seems to be applicable to the context of social media, as adolescents are expected to know whom their friends follow and what their friends watch. Additionally, participants were asked about their exposure to online content in a social setting, when being together with their friends.

Finally, our findings underlined that online prosocial behavior is an important topic exceeding the extent of adolescents’ online antisocial actions – a result that was also confirmed in previous research (Erreygers et al., 2017, 2018). In contrast to previous research on online prosocial behavior, we found no link between social media use frequency and prosocial actions (see Lysenstøen et al., 2021). This might be explained by the extremely high overall level of social media use among the surveyed adolescents. However, the findings also confirmed that it is not the mere use time on social media but the observed behavior of relevant others being decisive in shaping one’s own engagement in prosocial behavior.

This study is not without limitation. First, data did not include information on the different online social groups adolescents addressed with their behavior. It is unclear if prosocial online behavior primarily was directed towards other close circles, known persons or unknown strangers. Likewise, it is not clear if antisocial behavior was always conducted towards peers of the outgroup. For future studies, it would also be interesting to consider temporary group contacts since characteristics of online communities such as fast-moving group formations with a time-limited common goal might foster the valence of other more distal social contacts. Second, the cross-sectional data is not able to disentangle the causal relationships between communication, online social norms, outcome expectations and behavior. Peer norms, for example, might regulate what adolescents talk about with their friends and which contents they use together. Thus, they might not only influence adolescents’ expectations about communication as proposed by Geber and Hefner (2019) but also their actual communication with peers. To analyze the dynamics between these constructs, longitudinal data or experimental manipulations are required. Third, the content of adolescents’ communication with their friends not addressed in the present study could have been a potential norm-moderating factor (see Geber et al., 2019). Fourth, although our measures showed satisfactory psychometric qualities, they also need to be critically discussed. To measure antisocial online behavior, we used a broadly established measure on adolescents’ perpetration of cyberbullying (Erreygers et al., 2018). Cyberbullying can be considered a specific form of antisocial behavior that is performed repeatedly against a victim that might have less power. We did not give an introductory definition of cyberbullying but just asked about different antisocial actions. Likewise, the measures on online social norms did not cover all forms of queried antisocial and prosocial online behavior but were constructed as condensed versions to minimize measurement effects regarding their behavioral influence. Finally, data was collected among adolescents in Singapore – a country that is characterized by collectivism. Social norms may have different degrees of influence due to cultural orientation. Future studies should examine these cultural influences.

Conclusion

We conclude that the TNSB and its original assumptions can be considered a fruitful approach to explain adolescents’ online antisocial behavior. For online antisocial behavior, we identified an important role of descriptive norms and its combined explanatory prediction with corresponding injunctive norms and behavioral outcome expectations. We thus enhanced the range of this theory to the important setting of young users’ online interactions, having the potential to be applied in and extended to research on cyberbullying, sexual harassment and online hate. In previous research, it was often assumed that antisocial online behavior is particularly applied due to the high levels of anonymity found in the online environments (e.g., Suler, 2004; Valkenburg & Peter, 2011). The present data, however, confirmed that traditional social influence processes are important as well, especially on social media, where social interactions with known and unknown people are fundamental. This finding is in line with the SIDE approach, assuming that group norms are indeed influential in (deindividuated) online environments, also among preexisting groups of friends (see Postmes et al., 2000). Following SIDE, such group norms might be more fluent depending on situative characteristics. These volatile aspects of social influences in the online context need to be more intensively addressed in future research. Additionally, other theoretical approaches have shown that additional components such as adolescents’ attitudes or perceived behavioral control might be important as well and should be complemented in future studies (Festl, 2016; Pabian & Vandebosch, 2014). The results also have implications for the prevention of antisocial online behavior: in addition to enhancing settings of transparency, focusing on individual strategies can be considered another fruitful approach. Here, it seems promising to not only prevent actual antisocial behavior of users, but to also break the understanding that respective behavior might be socially accepted by others (especially in more volatile online group settings).

When it comes to forms of online prosocial behavior, the value of the TNSB was rather limited. In contrast to a complex interplay of social norms and personal perceptions, prosocial behavior on social media might be rather influenced by positive examples of relevant others such as close friends or influencers. In this context, other theoretical mechanisms such as parasocial relationships (e.g., Hoffner & Bond, 2022) might be more important and should be discussed in future research.

Footnotes

1 The confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) for the constructs were calculated based on maximum likelihood estimations (ML). Since the data showed skew values for online antisocial behavior and watching online social content with friends, we used maximum likelihood estimations with robust (Huber-White) standard errors and a scaled test statistic for these indicators (MLR; see Rosseel, 2012)

2 We calculated a joint CFA for prosocial and antisocial injunctive norms in order for the model to be identified.

3 We combined the original two items (I posted embarrassing videos or pictures of someone online and I altered pictures or videos of another person that had been posted online) to I altered and shared pictures or videos of another person to keep a balanced number of items for prosocial and antisocial behavior.

4 Using manifest indicators resulted in some slight changes regarding the central findings of the model. Most notably, we found direct positive effects of injunctive norms on prosocial and descriptive and injunctive norms on antisocial online behavior that were not confirmed in the more robust SEM model with latent indicators.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Use of AI Services

The authors declare they have not used any AI services to generate any part of the manuscript or data.

Acknowledgement

Open Science Statement

The study was preregistered (https://aspredicted.org/vb24h.pdf).

Ethics Statement

The design and instruments of the study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board. Both parental and participants’ consent were obtained.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to specifications in the IRB approval. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2026 Ruth Wendt, Vivian Hsueh Hua Chen