From restrictions to awareness: Examining the varied relationship between mediation strategies and parental awareness of adolescents online sexual experiences across age groups

Vol.18,No.5(2024)

This study examines the relationship of parental concerns and attitudes toward restriction strategies with the implementation of parental mediation strategies and parental awareness of their children’s involvement in sexting. The research involved 710 German adolescents aged between 12 and 17 years old, along with one parent from each family (569 mothers and 141 fathers). Data for this research was collected in 2019 as part of the EU Kids Online project. Multigroup structural equation modelling was used to analyse relationships between parental concerns, positive attitudes toward restrictions, mediation strategies and parental awareness across two age groups (12–14 and 15–17 years old). Results indicate that parents have equal concerns for younger and older children, but have more concerns for girls than boys. Regarding younger children, parental concerns are positively related to monitoring strategies while negatively associated with the use of restrictive strategies. Concerns about online activities have been found to predict the use of monitoring and active strategies for older children. Parental positive attitudes towards restrictions are also a predictor of the use of different strategies, with a positive relationship with restrictive, active and monitoring strategies in both age groups. Restrictive mediation is positively correlated with parental awareness about a child’s online sexual experiences in the younger group, while active mediation is positively correlated with parental awareness about a child’s online sexual experiences in the older group. In both age groups, monitoring strategies are negatively correlated with parental awareness about a child’s online sexual experiences. These findings contribute valuable insights into age-appropriate strategies when it comes to addressing sexting experiences.

sexting; parental mediation strategies; parental awareness; adolescents

Luka Stanić

Faculty of Law, The Social Work Study Centre, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia

Luka Stanić is a MSW and an assistant at the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Law, Study Centre for Social Work. In his scientific work, he focuses on the well-being of children and youth in the digital environment, as well as the issues related to the mental health of young people.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Banić, L., & Orehovački, T. (2024). A comparison of parenting strategies in a digital environment: A systematic literature review. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 8(4), Article 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti8040032

Barbovschi, M., Ní Bhroin, N., Chronaki, D., Ciboci, L., Farrugia, L., Lauri, M. A., Ševčíková, A., Staksrud, E., Tsaliki, L., & Velicu, A. (2021). Young people’s experiences with sexual messages online: Prevalence, types of sexting and emotional responses across European countries. EU Kids Online and the Department of Media and Communication, University of Oslo. http://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-91296

Baumgartner, S. E., Sumter, S. R., Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2012). Identifying teens at risk: Developmental pathways of online and offline sexual risk behavior. Pediatrics, 130(6), 1489–1496. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0842

Beckett, M. K., Elliott, M. N., Martino, S., Kanouse, D. E., Corona, R., Klein, D. J., & Schuster, M. A. (2010). Timing of parent and child communication about sexuality relative to children’s sexual behaviors. Pediatrics, 125(1), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0806

Benedetto, L., & Ingrassia, M. (2021). Digital parenting: Raising and protecting children in media world. In L. Benedetto & M. Ingrassia (Eds.), Parenting – Studies by an ecocultural and transactional perspective. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.92579

Boniel-Nissim, M., Efrati, Y., & Dolev-Cohen, M. (2020). Parental mediation regarding children’s pornography exposure: The role of parenting style, protection motivation and gender. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1590795

Boyd, D., & Hargittai, E. (2013). Connected and concerned: Variation in parents’ online safety concerns. Policy and Internet, 5(3), 245–269. https://doi.org/10.1002/1944-2866.POI332

Byrne, S., Katz, S. J., Lee, T., Linz, D., & McIlrath, M. (2014). Peers, predators, and porn: Predicting parental underestimation of children’s online risky experiences. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(2), 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12040

Caivano, O., Leduc, K., & Talwar, V. (2020). When you think you know: The effectiveness of restrictive mediation on parental awareness of cyberbullying experiences among children and adolescents. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 14(1), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2020-1-2

Cerna, A., Machackova, H., & Dedkova, L. (2015). Whom to trust: The role of mediation and perceived harm in support seeking by cyberbullying victims. Children & Society, 30(4), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12136

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Cingel, D. P., & Krcmar, M. (2013). Predicting media use in very young children: The role of demographics and parent attitudes. Communication Studies, 64(4), 374–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2013.770408

Claes, M., Perchec, C., Miranda, D., Benoit, A., Bariaud, F., Lanz, M., Marta, E., & Lacourse, E. (2011). Adolescents’ perceptions of parental practices: A cross-national comparison of Canada, France, and Italy. Journal of Adolescence, 34(2), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.009

Cooper, K., Quayle, E., Jonsson, L., & Svedin, C. G. (2016). Adolescents and self-taken sexual images: A review of the literature. Computers in Human Behavior, 55(Part B), 706–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.003

Corcoran, E., Doty, J., Wisniewski, P., & Gabrielli, J. (2022). Youth sexting and associations with parental media mediation. Computers in Human Behavior, 132, Article 107263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107263

Cuccì, G., Olivari, M. G., Colombo, C. C., & Confalonieri, E. (2023). Risk or fun? Adolescent attitude towards sexting and parental practices. Journal of Family Studies, 30(1), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2023.2189151

Davis, K. (2023). Technology’s child: Digital media’s role in the ages and stages of growing up. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/13406.001.0001

Dedkova, L., & Mylek, V. (2022). Parental mediation of online interactions and its relation to adolescents’ contacts with new people online: The role of risk perception. Information, Communication & Society, 26(16), 3179–3196. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2146985

Dedkova, L., & Smahel, D. (2020). Online parental mediation: Associations of family members’ characteristics to individual engagement in active mediation and monitoring. Journal of Family Issues, 41(8), 1112–1136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19888255

Dehue, F., Bolman, C., & Völlink, T. (2008). Cyberbullying: Youngsters’ experiences and parental perception. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 11(2), 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0008

Dietvorst, E., Hiemstra, M., Hillegers, M. H. J., & Keijsers, L. (2018). Adolescent perceptions of parental privacy invasion and adolescent secrecy: An illustration of Simpson’s paradox. Child Development, 89(6), 2081–2090. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13002

Dodig-Ćurković, K. (2017). Adolescentna kriza – kako je dijagnosticirati i liječiti? [Adolescent Crisis – how is it Diagnosed and Treated?]. Medicus, 26(2), 223–227. https://hrcak.srce.hr/189148

Dolev-Cohen, M., & Ricon, T. (2020). Demystifying sexting: Adolescent sexting and its associations with parenting styles and sense of parental social control in Israel. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 14(1), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2020-1-6

Dolev-Cohen, M., & Ricon, T. (2022). Dysfunctional parent-child communication about sexting during adolescence. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(3), 1689–1702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02286-8

Doyle, C., Douglas, E., & O’Reilly, G. (2021). The outcomes of sexting for children and adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Adolescence, 92(1), 86–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.08.009

Drouin, M., Ross, J., & Tobin, E. (2015). Sexting: A new, digital vehicle for intimate partner aggression? Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.001

Dully, J., Walsh, K., Doyle, C., & O’Reilly, G. (2023). Adolescent experiences of sexting: A systematic review of the qualitative literature, and recommendations for practice. Journal of Adolescence, 95(6), 1077–1105. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12181

Dykstra, V. W., Willoughby, T., & Evans, A. D. (2020). A longitudinal examination of the relation between lie-telling, secrecy, parent-child relationship quality, and depressive symptoms in late-childhood and adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(2), 438–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01183-z

Eelmaa, S. (2023). Exploring parental perspectives on online sexual risks and harm. Trames: A Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 27(2), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.3176/tr.2023.2.01

eSafety (2022). Parenting in digital age. eSafety Commissioner. https://www.esafety.gov.au/research/parenting-digital-age

EU Kids Online (2014). Testing the reliability of scales on parental internet mediation. EU Kids Online. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/60220

European Institute for Gender Equality (2023). Gender Equality Index. European Institute for Gender Equality. https://eige.europa.eu/

Fenton, K. A. (2001). Measuring sexual behaviour: Methodological challenges in survey research. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 77(2), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.77.2.84

Gelles-Watnick, R. (2022). Explicit content, time-wasting are key social media worries for parents of U.S. teens. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/12/15/explicit-content-time-wasting-are-key-social-media-worries-for-parents-of-u-s-teens/

Geržičáková, M., Dedkova, L., & Mylek, V. (2023). What do parents know about children’s risky online experiences? The role of parental mediation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 141, Article 107626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107626

Ghosh, A. K., Badillo-Urquiola, K., Rosson, M. B., Xu, H., Carroll, J. M., & Wisniewski, P. J. (2018, April). A matter of control or safety? Examining parental use of technical monitoring apps on teens’ mobile devices. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–14). https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173768

Glüer, M., & Lohaus, A. (2018). Elterliche und kindliche Einschätzung von elterlichen Medienerziehungsstrategien und deren Zusammenhang mit der kindlichen Internetnutzungskompetenz [Parents‘ and Children‘s Perspectives of Parental Mediation Strategies in Association with Children’s Internet Skills]. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie, 67(2), 181–203. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173768

Haddon, L., Cino, D., Doyle, M.-A., Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., & Stoilova, M. (2020). Children’s and young people’s digital skills: A systematic evidence review. ySKILLS. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4274654

Hawk, S. T., Becht, A., & Branje, S. (2015). “Snooping” as a distinct parental monitoring strategy: Comparisons with overt solicitation and control. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(3), 443–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12204

Hawk, S. T., Keijsers, L., Frijns, T., Hale, W. W., Branje, S., & Meeus, W. (2013). “I still haven’t found what I’m looking for”: Parental privacy invasion predicts reduced parental knowledge. Developmental Psychology, 49(7), 1286–1298. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029484

Hernandez, J. M., Ben-Joseph, E. P., & Reich, S. (2024). Parental monitoring of early adolescent social technology use in the US: A mixed-method study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 33(3), 759–776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02734-6s

Hwang, Y., Choi, I., Yum, J.-Y., & Jeong, S.-H. (2017). Parental mediation regarding children’s smartphone use: Role of protection motivation and parenting style. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(6), 362–368 https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0555

Hwang, Y., & Jeong, S. H. (2015). Predictors of parental mediation regarding children’s smartphone use. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 18(12), 737–743. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0286

Internet Watch Foundation (2023). The Annual Report 2022. Internet Watch Foundation. https://www.iwf.org.uk/about-us/who-we-are/annual-report-2022/

Jeffery, C. P. (2020). “It’s really difficult. We’ve only got each other to talk to.” Monitoring, mediation, and good parenting in Australia in the digital age. Journal of Children and Media, 15(2), 202–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2020.1744458

Kalmus, V., Sukk, M., & Soo, K. (2022). Towards more active parenting: Trends in parental mediation of children’s internet use in European countries. Children & Society, 36(5), 1026–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12553

Klettke, B., Hallford, D. J., Clancy, E., Mellor, D. J., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2019). Sexting and psychological distress: The role of unwanted and coerced sexts. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 22(4), 237–242. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0291

Krcmar, M., & Cingel, D. P. (2016). Examining two theoretical models predicting American and Dutch parents’ mediation of adolescent social media use. Journal of Family Communication, 16(3), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2016.1181632

Kuhn, E. S., & Laird, R. D. (2011). Individual differences in early adolescents’ beliefs in the legitimacy of parental authority. Developmental Psychology, 47(5), 1353–1365. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024050

Kuldas, S., Sargioti, A., Staksrud, E., Heaney, D., & O’Higgins Norman, J. (2023). Are confident parents really aware of children’s online risks? A conceptual model and validation of parental self-efficacy, mediation, and awareness scales. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 6, 252–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-023-00157-x

Kyriazos, T., & Poga-Kyriazou, M. (2023). Applied psychometrics estimator considerations in commonly encountered conditions in CFA, SEM, and EFA practice. Psychology, 14(5), 799–828. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2023.145043

Lanzarote Committee (2019). Opinion on child sexually suggestive or explicit images and/or videos generated, shared and received by children. Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/opinion-of-the-lanzarote-committee-on-child-sexually-suggestive-or-exp/168094e72c

Lee, S. J. (2013). Parental restrictive mediation of children’s internet use: Effective for what and for whom? New Media & Society, 15(4), 466–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812452412

Li, C. H. (2021). Statistical estimation of structural equation models with a mixture of continuous and categorical observed variables. Behavior Research Methods, 53(5), 2191–2213. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01547-z

Liau, A. K., Khoo, A., & Ang, P. H. (2008). Parental awareness and monitoring of adolescent internet use. Current Psychology, 27(3), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-008-9038-6

Lionetti, F., Palladino, B. E., Passini, C. M., Casonato, M., Hamzallari, O., Ranta, M., Dellagiulia, A., & Keijsers, L. (2018). The development of parental monitoring during adolescence: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 16(5), 552–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2018.1476233

Lippman, J. R., & Campbell, S. W. (2014). Damned if you do, damned if you don’t…if you’re a girl: Relational and normative contexts of adolescent sexting in the United States. Journal of Children and Media, 8(4), 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2014.923009

Liu, Y.-L. (2020). Maternal mediation as an act of privacy invasion: The association with internet addiction. Computers in Human Behavior, 112, Article 106474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106474

Livingstone, S., & Görzig, A. (2014). When adolescents receive sexual messages on the internet: Explaining experiences of risk and harm. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.021

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. (2008). Parental mediation of children’s internet use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52(4), 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150802437396

Livingstone, S., Kalmus, V., & Talves, K. (2014). Girls’ and boys’ experiences of online risk and safety. In C. Carter, L. Steiner, & L. McLaughlin (Eds.), The Routledge companion to media and gender (pp. 190–200). Routledge.

Livingstone, S., Ólafsson, K., Helsper, E. J., Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F., Veltri, G. A., & Folkvord, F. (2017). Maximizing opportunities and minimizing risks for children online: The role of digital skills in emerging strategies of parental mediation. Journal of Communication, 67(1), 82–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12277

Lopez-De-Ayala, M. C., Martínez-Pastor, E., & Catalina-García, B. (2019). Nuevas estrategias de mediación parental en el uso de las redes sociales por adolescents [New strategies of parental mediation in the use of social networks by adolescents]. El Profesional de la Información, 28(5), Article e280523. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.sep.23

Marciano, A. (2022). Parental surveillance and parenting styles: Toward a model of familial surveillance climates. Mobile Media & Communication, 10(1), 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579211012436

Mavoa, J., Coghlan, S., & Nansen, B. (2023). “It’s about safety not snooping”: Parental attitudes to child tracking technologies and geolocation data. Surveillance & Society, 21(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v21i1.15719

Morelli, M., Chirumbolo, A., Bianchi, D., Baiocco, R., Cattelino, E., Laghi, F., Sorokowski, P., Misiak, M., Dziekan, M., Hudson, H., Marshall, A., Nguyen, T. T. T., Mark, L., Kopecky, K., Szotkowski, R., Demirtaş, E. T., Van Ouytsel, J., Ponnet, K., Walrave, M., . . . Drouin, M. (2020). The role of HEXACO personality traits in different kinds of sexting: A cross-cultural study in 10 countries. Computers in Human Behavior, 113, Article 106502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106502

Mori, C., Park, J., Temple, J. R., & Madigan, S. (2022). Are youth sexting rates still on the rise? A meta-analytic update. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(4), 531–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.026

Nathanson, A. I., Eveland, W. P., Jr., Park, H.-S., & Paul, B. (2002). Perceived media influence and efficacy as predictors of caregivers’ protective behaviors. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 46(3), 385–410. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4603_5

Palmer, T. (2015). Digital dangers: The impact of technology on the sexual abuse and exploitation of children and young people. Barnardo's. https://www.barnardos.org.uk/research/digital-dangers-impact-technology-sexual-abuse-and-exploitation-children-and-young-people

Paus-Hasebrink, I., Bauwens, J., Dürager, A. E., & Ponte, C. (2012). Exploring types of parent–child relationship and internet use across Europe. Journal of Children and Media, 7(1), 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2012.739807

Poulain, T., Meigen, C., Kiess, W., & Vogel, M. (2023). Media regulation strategies in parents of 4- to 16-year-old children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 23, Article 371. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15221-w

Quayle, E. (2022). Self-produced images, sexting, coercion and children’s rights. ERA Forum, 23(2), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12027-022-00714-9

Rodríguez-de-Dios, I., van Oosten, J. M. F., & Igartua, J.-J. (2018). A study of the relationship between parental mediation and adolescents’ digital skills, online risks and online opportunities. Computers in Human Behavior, 82, 186–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.012

Rogers, R. W. (1975). A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1. The Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 93–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803

Rote, W. M., & Smetana, J. G. (2016). Beliefs about parents’ right to know: Domain differences and associations with change in concealment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(2), 334–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12194

Salter, M., Crofts, T., & Lee, M. (2013). Beyond criminalisation and responsibilisation: Sexting, gender and young people. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 24(3), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2013.12035963

Santa Maria, D., Markham, C., Swank, P., Baumler, E., McCurdy, S., & Tortolero, S. (2014). Does parental monitoring moderate the relation between parent–child communication and pre-coital sexual behaviours among urban, minority early adolescents? Sex Education, 14(3), 286–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2014.886034

Shin, W., & Kim, H. K. (2019). What motivates parents to mediate children’s use of smartphones? An application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 63(1), 144–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2019.1576263

Smahel, D., Machackova, H., Mascheroni, G., Dedkova, L., Staksrud, E., Ólafsson, K., Livingstone, S., & Hasebrink, U. (2020). EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries. EU Kids Online. https://doi.org/10.21953/lse.47fdeqj01ofo

Smetana, J. G., Villalobos, M., Tasopoulos-Chan, M., Gettman, D. C., & Campione-Barr, N. (2008). Early and middle adolescents’ disclosure to parents about activities in different domains. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 693–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.010

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Luyckx, K., & Goossens, L. (2006). Parenting and adolescent problem behavior: An integrated model with adolescent self-disclosure and perceived parental knowledge as intervening variables. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.305

Sonck, N., Nikken, P., & de Haan, J. (2012). Determinants of internet mediation. Journal of Children and Media, 7(1), 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2012.739806

Sorbring, E. (2014). Parents’ concerns about their teenage children’s internet use. Journal of Family Issues, 35(1), 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X12467754

Sorbring, E., Hallberg, J., Bohlin, M., & Skoog, T. (2014). Parental attitudes and young people’s online sexual activities. Sex Education, 15(2), 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2014.981332

Ståhl, S., & Dennhag, I. (2020). Online and offline sexual harassment associations of anxiety and depression in an adolescent sample. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 75(5), 330–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2020.1856924

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71(4), 1072–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00210

Symons, K., Ponnet, K., Emmery, K., Walrave, M., & Heirman, W. (2017). Parental knowledge of adolescents’ online content and contact risks. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(2), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0599-7

Symons, K., Ponnet, K., Walrave, M., & Heirman, W. (2018). Sexting scripts in adolescent relationships: Is sexting becoming the norm? New Media & Society, 20(10), 3836–3857. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818761869

Talves, K., & Kalmus, V. (2015). Gendered mediation of children’s internet use: A keyhole for looking into changing socialization practices. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 9(1), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2015-1-4

Tomić, I., Burić, J., & Štulhofer, A. (2018). Associations between croatian adolescents’ use of sexually explicit material and sexual behavior: Does parental monitoring play a role? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(6), 1881–1893. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-1097-z

Van Ouytsel, J., Van Gool, E., Walrave, M., Ponnet, K., & Peeters, E. (2016). Sexting: Adolescents’ perceptions of the applications used for, motives for, and consequences of sexting. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(4), 446–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1241865

Widman, L., Javidi, H., Maheux, A. J., Evans, R., Nesi, J., & Choukas-Bradley, S. (2021). Sexual communication in the digital age: Adolescent sexual communication with parents and friends about sexting, pornography, and starting relationships online. Sexuality & Culture, 25(6), 2092–2109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09866-1

Widmer, S., & Albrechtslund, A. (2021). The ambiguities of surveillance as care and control: Struggles in the domestication of location-tracking applications by Danish parents. Nordicom Review, 42(S4), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.2478/nor-2021-0042

York, L., MacKenzie, A., & Purdy, N. (2021). Attitudes to sexting amongst post-primary pupils in Northern Ireland: A liberal feminist approach. Gender and Education, 33(8), 999–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2021.1884196

Young, R., & Tully, M. (2022). Autonomy vs. control: Associations among parental mediation, perceived parenting styles, and U.S. adolescents’ risky online experiences. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 16(2), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2022-2-5

Young, R., Tully, M., Parris, L., Ramirez, M., Bolenbaugh, M., & Hernandez, A. (2024). Barriers to mediation among U.S. parents of adolescents: A mixed-methods study of why parents do not monitor or restrict digital media use. Computers in Human Behavior, 153, Article 108093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.108093

Zlamal, R., Machackova, H., Smahel, D., Abramczuk, K., Ólafsson, K., & Staksrud, E. (2020). EU Kids Online 2020: Technical report. EU Kids Online. https://doi.org/10.21953/lse.04dr94matpy7

Authors’ Contribution

This study was devised and conducted by Luka Stanić.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

October 9, 2023

Revisions received:

February 27, 2024

July 18, 2024

September 20, 2024

Accepted for publication:

September 23, 2024

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

Parental awareness of children’s online experiences can be important for adapting parenting practices (Kuldas et al., 2023). Without this awareness, parents cannot effectively discuss and help children cope with negative experiences (Caivano et al., 2020). Studies show that parents are aware of children’s less risky experiences, but they are less informed about potentially harmful experiences like cyber victimisation and sexting (Geržičáková et al., 2023; Livingstone & Görzig, 2014). For instance, only 21% of parents know about their child’s exposure to sexting (Livingstone & Görzig, 2014). This is concerning as parents’ primary worries often involve child exposure to online sexual content and messages (eSafety, 2022; Gelles-Watnick, 2022).

Previous studies showed that parental awareness of child online experiences could be enhanced by applying mediation strategies (Byrne et al., 2014; Cerna et al., 2015; Cuccì et al., 2023; Kuldas et al., 2023; Santa Maria et al., 2014). Results vary from restrictive mediation increasing parental awareness by reducing the possibility of exposure to online risks (Caivano et al., 2020; Kuldas et al., 2023), to active mediation through which parents encourage conversations with their children, and children share their experiences with their parents (Byrne et al., 2014; Cerna et al., 2015; Geržičáková et al., 2023; Symons et al., 2017). However, when it comes to sexual matters children are reluctant to talk about sexual experiences to parents (Rote & Smetana, 2016). In the study by Widman et al. (2021), only 9% of adolescents talked to their parents about online sexual behaviours. In the research by Dolev-Cohen and Ricon (2020), more than half of the study participants told no one about being asked to send sexual messages or images, and only a few chose to tell an adult.

Previous studies showed that parental concerns about child’s online experiences are related to the use of mediation strategies (Hwang & Jeong, 2015; Hwang et al., 2017). However, previous studies did not specifically examine the relationship between parental concerns about children’s online sexual experiences and the use of mediation strategies. Nor have they examined the relationship between mediation strategies and parental awareness of the child’s receipt of sexual messages. This is important as parents express concerns about online sexual experiences, and children are reluctant to share their sexual experiences with their parents, which sometimes could be risky (Rote & Smetana, 2016).

Further, as growing older, children seek more privacy and autonomy, thus perceiving that parents have less legitimacy to impose restrictions than younger children (Kuhn & Laird, 2011). In addition, parents may hold negative attitudes towards restrictions and monitoring as it could interfere with child’s privacy at a certain age, therefore not using restrictive and monitoring strategies, even if they are concerned (Hernandez et al., 2024). The aforementioned attitudes may be linked to the use of active mediation, as parents might perceive it as more appropriate when taking the child’s privacy into account (Lopez-De-Ayala et al., 2019). However, previous research did not examine how the relationship between parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences, the use of mediation strategies and parental awareness of the child’s receipt of sexual messages may differ due to the child’s age. In addition, studies that examined parental perceptions of mediation strategies and their use were mostly qualitative (e.g., Jeffery, 2020; Lopez-De-Ayala et al., 2019).

Furthermore, there are some methodological limitations of previous studies that examined parental awareness of child online experiences. Prior studies have used composite variables of parental and child reports on the frequency of events as a measure of parental awareness. It has been found that such measures are not the best indicators because both parents and children can overestimate or underestimate the frequency of risky behaviours (Byrne et al., 2014; Caivano et al., 2020; Dehue et al., 2008; Symons et al., 2017). On the other hand, Kuldas et al. (2023) solely relied on parental reports of the children’s risky behaviours. Geržičáková et al. (2023) report that these measures are not reliable, as they measure only perceived parental awareness. Thus, they found a low correlation between perceived parental awareness and objective awareness which combines child and parent reports.

This paper aims to address the mentioned literature gaps and examine how the relationship between parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experience, mediation strategies and parental awareness of a child’s online sexual experience differ due to the child’s age.

Sexting

The phenomenon of sending or receiving sexually explicit messages and images is called sexting (Cooper et al., 2016; Klettke et al., 2019). The results of a recent meta-analysis indicate that 19.3% of adolescents send sexual messages, while 34.8% receive them (Mori et al., 2022). The same study established that sexting increases with the age of adolescents and that girls are more likely than boys to receive sexual messages. However, gender differences in sexting differ from country to country. For instance, studies report that in more traditional countries, more boys than girls engage in sexting, while in more sexually permissive countries there are no significant gender differences (Barbovschi et al., 2021; Baumgartner et al., 2012; Morelli et al., 2020). In countries where gender differences are observable, Barbovschi et al. (2021) report that boys tend to send and request sexual messages more often than girls. Further, girls tend to receive more requests to send sexual messages than boys and girls more often than boys receive unwanted requests (Barbovschi et al., 2021). The same authors report that girls and younger children are more often upset by sending or receiving sexual messages than older children and boys.

Consensual sexting may support youth in sexual agency, exploration and expression of their sexuality when they start experimenting with sexual behaviour and form romantical relationships (Symons et al., 2018). However, there is always a risk of unintended leaks of these messages, blackmail, bullying or sexual exploitation (Van Ouytsel et al., 2016). Furthermore, if received sexual messages are unwanted, they can be considered harassment or grooming (Palmer, 2015; Salter et al., 2013). In addition, there are ongoing discussions regarding whether self-generated images should be classified as child pornography (Quayle, 2022). However, the Lanzarote Committee (2019) states that self-generated images or possession of sexual images or videos should not be classified as child pornography if the child has reached the legal age for sexual activities and if such material is produced and possessed with their consent solely for their private use. On the other hand, if younger children create such content, it should be regarded as a result of abusive or exploitative conduct. In addition, if the child of legal age was, for instance, pressured or threatened to send sexual messages, it should also be considered child pornography (Quayle, 2022). Given that sexting is a risky online behaviour and may be associated with mental health problems, reduced positive emotions, feelings of fear and embarrassment, as well as reputational consequences, it is important to examine whether parental mediation strategies can predict parental awareness of their children’s sexting experiences (Doyle et al., 2021).

Meditation Strategies

According to Sonck et al. (2013), there are several different mediation strategies. Restrictive content mediation refers to restrictions parents may impose on social network use, watching video clips online, using instant messaging, or downloading content. Monitoring strategies refer to parents checking children’s social network profiles to see which people the child added to a social network, their messages, or websites the child visited. Active mediation strategies refer to suggesting ways of using the internet safely and of behaving towards other people online, talking about coping strategies in the event of harm from internet use, and explaining the reliability of websites (Sonck et al., 2013). However, there is limited data on the relationship between these strategies and parental awareness of their children’s online sexual experiences. Dolev-Cohen and Ricon (2022) state that authoritative parenting, linked in other research with active mediation, can enable awareness of child behaviour through listening and discussions. On the other hand, the authoritarian style, which is linked with the use of restrictive strategies, leads to dysfunctional parent-child communication about sexting (Dolev-Cohen & Ricon, 2022).

Protection Motivation Theory

The antecedents of parental mediation strategies will be examined through the Protection Motivation Theory (Rogers, 1975) and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). According to the Protection Motivation Theory, a person’s behaviour is conditioned by their perception of the danger and risk associated with that behaviour. Whilst Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) is primarily concerned with individual risk perception and the behaviours one may adopt to mitigate these risks for oneself, several studies have extended PMT to encompass parental behaviours aimed at safeguarding children (Lee, 2013; Livingstone & Helsper, 2008). The rationale for this expansion of PMT lies in the fact that parents are the primary agents of a child’s socialisation, capable of shaping the child’s attitudes and behaviours, thus bearing the responsibility to protect them from potential risks (Benedetto & Ingrassia, 2021). For example, if parents are concerned about the risky online behaviours of their children, they are more likely to implement mediation strategies to mitigate the risks (Hwang et al., 2017). Several studies have shown that parents who are more concerned implement more restrictive, active and monitoring mediation strategies related to a child’s digital usage (Hernandez et al., 2024; Hwang & Jeong, 2015; Hwang et al., 2017; Krcmar & Cingel, 2016; Livingstone et al., 2017; Nathanson et al., 2002).

Existing research suggests that parental concerns differ concerning the child’s gender and age. The study by Sorbring et al. (2014) showed that parents express more concerns about sexting towards girls than boys. Parents are potentially aware of societal pressure on girls to sext and label whether they agree to sext or not (Lippman & Campbell, 2014). For instance, if girls refuse to sext they are labelled as prude, and if they agree, they risk being labelled as promiscuous (Lippman & Campbell, 2014). Thus:

H1a: Parents will express more concerns about online sexual experiences for girls than boys.

Due to higher concerns, parents are more likely to implement more mediation strategies towards girls than boys (Dedkova & Mylek, 2022; Symons et al., 2017). However, there are mixed findings regarding gender differences (Boniel-Nissim et al., 2020; Livingstone et al., 2014). These differences may be due to cultural differences and the level of gender equality. For instance, Talves and Kalmus (2015) found that gender differences are higher in countries with higher levels of gender equality. According to the authors, parents may reflect more on their practices in those countries. Thus, employing more gender-sensitive practices. According to the Gender Equality Index (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2023), Germany ranks 11th among European Union countries in terms of gender equality, positioning slightly above the EU average. Therefore:

H1b: Parents will apply more mediation strategies towards girls than boys.

Regarding age differences, existing studies suggest that parents of younger children often exhibit more pronounced concerns regarding potential internet dangers, such as the fear of their children encountering strangers online or being exposed to sexual content (Boyd & Hargittai, 2013; eSafety, 2022). As the authors stated, younger children are often perceived by parents as more vulnerable, possessing limited skills in identifying potential threats, and less capable of managing inappropriate content compared to their older counterparts. Therefore:

H2a: Parents will express more concerns about online sexual experiences for younger children (12–14) than for older children (15–17).

The perception that younger children are more vulnerable likely leads to parents imposing more stringent restrictions on younger children while allowing older children more freedom (Boyd & Hargittai, 2013). In addition, parents might try to respect their child’s growing needs for autonomy and privacy and take into account the child’s increasing digital skills, hence using less mediation strategies (Symons et al., 2017; Young & Tully, 2022). Research by Dedkova and Mylek (2022) confirmed the assumption that parents less mediate their child’s internet use as the child grows older. Accordingly:

H2b: Parents will use more mediation strategies toward younger children (12–14) than older children (15–17).

Previous studies indicate that parental concerns are associated with the use of mediation strategies. Nevertheless, prior research has not specifically examined parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences and their relationship with mediation strategies. Additionally, studies have not examined differences in this association concerning the child’s age during adolescence. Although parents tend to less mediate toward older children, they still apply some mediation strategies. If parents recognise child autonomy and privacy, they may use different mediation strategies when concerned about the child’s online experiences (Davis, 2023; Hernandez et al., 2024). Studies have shown that parents perceive restrictions and monitoring as acceptable for younger children, but acceptability decreases with the child’s age (eSafety, 2022; Hernandez et al., 2024). Simultaneously, parents consider active mediation acceptable for both younger and older children (eSafety, 2022). Therefore, the hypotheses are:

H3a: Parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences will be positively related to applying active, restrictive and monitoring strategies toward younger children (12–14).

H3b: Parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences will be more strongly positively related to applying active strategies than restrictive and monitoring strategies toward older children (15–17).

Theory of Planned Behaviour

The Theory of Planned Behaviour posits that an individual’s behaviour is influenced by three factors: attitudes towards a specific behaviour, perceived self-efficacy in implementing that behaviour, and environmental pressure for that behaviour. Previous research has shown that the selection of mediation strategies is influenced by parents’ perceived self-efficacy (Kuldas et al., 2023; Shin & Kim, 2019), perceived environmental pressure, and parents’ attitudes regarding the need to control their child’s internet use (Cingel & Krcmar, 2013; Krcmar & Cingel, 2016). Several studies showed that parents may perceive restrictions and monitoring as privacy invasions (Hawk et al., 2013; Liu, 2020). Further, parents who believe that it would violate their children’s privacy and autonomy are less likely to use such methods (Ghosh et al., 2018; Marciano, 2022; Mavoa et al., 2023; Young et al., 2024). Additionally, parents who oppose restrictions and monitoring due to privacy and autonomy concerns perceive discussions about risks as an acceptable way of supervising children’s behaviour (Jeffery, 2020; Widmer & Albrechtslund, 2021). Similar was found in research by Hernandez et al. (2024) where parents choose active strategies when they are concerned that restrictions would not be appropriate and that children would become more secretive as a result of these restrictions. Although the use of different mediation strategies is found to be intercorrelated (Rodríguez-de-Dios et al., 2018), there is a noticeable shift from using restrictive strategies toward more active strategies (Kalmus et al., 2022). This may reflect changes in parental attitudes about appropriate strategies. Although it is mentioned that parental perceptions of both restrictive and monitoring strategies may be related to the use of mediation strategies, the dataset utilised in this study includes only positive attitudes towards restrictive strategies. Nevertheless, previous studies have identified similar concerns regarding both monitoring and restrictive strategies, which may suggest that there is an overlap in attitudes towards these two approaches (Lopez-De-Ayala et al., 2019). Therefore:

H4a: Parents with more positive attitudes towards restrictive strategies will employ more restrictive and monitoring strategies.

H4b: Subsequently, parents with less positive attitudes towards restrictive strategies will employ more active strategies.

Given that there is no clear basis on how to predict age differences in these relationships, following research question is posited:

RQ1: Are there differences in the relationship between positive attitudes towards restrictive strategies and the use of mediation strategies with regard to the child’s age?

Mediation Strategies and Parental Awareness

Previous studies vary in their findings regarding which mediation strategies are related to parental awareness of children’s online experiences. For instance, in the studies with children aged 9 to 16 active mediation was found to be positively related to parental awareness about experiences with cyberbullying and stranger approaches online (Byrne et al., 2014; Cerna et al., 2015). Active mediation involves open discussions with children about potential risks, encouraging them to self-disclose and thereby enhancing parental awareness (Soenens et al., 2006). To highlight the importance of communication with children, Stattin and Kerr (2000) found that parental awareness of a child’s behaviour and experiences is primarily derived from the child’s willingness to share.

Studies regarding restrictive strategies are inconclusive. On the one hand, Kuldas et al. (2023) found that restrictive strategies are associated with increased parental awareness of a child’s online experiences. The authors explain that restrictive strategies may reduce the initial likelihood of encountering online risks, thereby leading parents to more accurately report their children’s experiences of such risks. However, the authors only examined perceived parental awareness of the child’s online experiences, which lacks reliability as parents mostly misjudge the occurrence of risky experiences (Caivano et al., 2020; Geržičáková et al., 2023; Kuldas et al., 2023). Further, studies with children aged 8 to 14 years and 11 to 17 years showed that children may view their parents less favourably under restrictive strategies, leading to a reluctance to share experiences (Nathanson et al., 2002; Young & Tully, 2022). Therefore, several studies which measured reports of child’s online experiences from both parents and child have found that restrictive mediation does not increase parental awareness about child’s online experiences (Byrne et al., 2014; Caivano, et al., 2020; Cerna et al., 2015; Geržičáková et al., 2023). However, these studies also have limitations regarding measuring parental awareness of children’s online experiences. For instance, studies have shown that composite variables of parental and child reports on the frequency of a child’s risky experiences are unreliable indicators of parental awareness about those experiences due to potential overestimation or underestimation of occurrence by both parties (Byrne et al., 2014; Caivano et al., 2020; Dehue et al., 2008; Symons et al., 2017).

Moreover, the mentioned studies have not specifically examined parental awareness of children’s online sexual experiences. This is particularly important for romantic and sexual experiences that may be risky, but children perceive them as private and are reluctant to share them with their parents (Rote & Smetana, 2016). Additionally, the previous studies did not explore potential age differences in the relationship between mediation strategies and parental awareness of children’s online experiences.

As children grow through adolescence, they tend to seek increased autonomy and privacy, moving away from parental supervision and striving to make responsible choices independently (Dodig-Ćurković, 2017). During this developmental stage, finding a balance between fostering adolescents’ autonomy in decision-making and ensuring adequate parental monitoring and guidance is essential (Liau et al., 2008). In the realm of online activities, this balance involves negotiating between restrictions and active engagement strategies.

How children will react to restrictions may be related to their age. Several studies found that younger children perceive more than older ones, that parents have legitimate rights to impose restrictions and more rights to know about their experiences (Claes et al., 2011; Kuhn & Laird, 2011; Rote & Smetana, 2016). Therefore, younger children are more likely than older ones to follow these rules, mitigating potential risks (Dykstra et al., 2020). In that sense, Corcoran et al. (2022) in a study with children aged 10–14 found that restrictive mediation decreases a child’s receipt of sexual messages. Consequently, parents could accurately report that the risk did not occur. Additionally, higher parent-child relationship quality, which could be enhanced by active mediation, also predicts more child disclosure about their experiences, thus enhancing parental awareness about a child’s online experiences (Smetana et al., 2008). Building on this:

H5a: Parental use of active strategies will be positively related to parental awareness of a child’s sexual message receipt in children aged 12–14.

H5b: Parental use of restrictive strategies will be positively related to parental awareness of a child’s sexual message receipt in children aged 12–14.

The need for privacy and digital skills evolves with age (Smahel et al., 2020), therefore, older children might use the internet in ways unknown to their parents, eluding parental supervision and restrictions on their online activities (Liau et al., 2008). In that situation, the parent’s main source of information could be the child’s self-disclosure, which may be enhanced by active mediation (Dykstra et al., 2020). Accordingly:

H5c: Parental use of active strategies will be more strongly related to parental awareness of a child’s sexual message receipt than restrictive strategies in children aged 15–17.

Further, Geržičáková et al. (2023) found that monitoring strategies decrease parental awareness of a child’s online experiences. Prior studies have shown that offline monitoring can disrupt child-parent communication, as children perceive it as intrusive, leading them to become more secretive (Hawk et al., 2015; Rote & Smetana, 2016). However, similar to restriction, monitoring may enhance parental awareness of younger children’s online experiences as they may perceive monitoring as a legitimate parenting practice and less opposed to it (Kuhn & Laird, 2011). On the other hand, children may perceive monitoring as intrusive more as they age (Banić & Orehovački, 2024; Lionetti et al., 2018). Hence:

H5d: Parental use of monitoring strategies will be positively associated with parental awareness of a child’s sexual message receipt in children aged 12–14.

H5e: Parental use of monitoring strategies will be negatively associated with parental awareness of a child’s sexual message receipt in children aged 15–17.

Methods

Sample

This study involved 710 children from Germany (360 boys and 350 girls) aged 12 to 17 years (M = 14.58, SD = 1.709), along with one parent from each family (569 mothers and 141 fathers, Mage = 43.65, SD = 5.938). Data was collected as part of the EU Kids Online IV project from June 22nd to July 1st 2019. Computer Assisted Self-Interviews at home (CASI) were conducted by Ipsos Germany. A quota sample based on ADM with random walk was used, ensuring representative quotas for region, age and gender of the child, education of the parent, and household income, along with weights for achieved quotas.

Instruments

All questionnaires utilised were developed for the implementation of the EU Kids Online II project and have been adapted for EU Kids Online IV (Zlamal et al., 2020). The reliability of the items on parental mediation strategies was tested across all countries, including Germany, and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) demonstrated a good fit of the model (EU Kids Online, 2014). In this study, CFA was conducted for all the used variables. Given that parental concerns, restrictive strategies, and parental awareness are categorical variables, the robust Maximum Likelihood estimator (MLR) was used to perform the CFA. Although it is recommended to use WLSMV (Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance adjusted) as an estimator in CFA for categorical variables (Li, 2021), MLR was chosen to treat all variables consistently across different tests within the study (Kyriazos & Poga-Kyriazou, 2023).

Measurement invariance was tested for all variables between fathers and mothers, except for parental awareness, as it was measured with only two variables. To determine invariance, the Cheung and Rensvold (2002) criteria were used, which state that the change in CFI between levels of invariance should not be greater than .01. According to this criterion, invariance was established for variables: parental attitudes (ΔCFI = .001), restrictive strategies (ΔCFI = .001), and monitoring strategies (ΔCFI = .002). For active mediation strategies, partial strong invariance was found. Since the parental concerns model is just identified with 0 degrees of freedom, the significance criterion χ2 was used to assess invariance, and it was determined that invariance exists because χ2 was statistically insignificant at all levels.

Parental Concerns

This questionnaire consists of 3 items, through which parents indicate whether they are concerned about their child’s online sexual experiences. Possible responses are 0 (not concerned) and 1 (concerned). The questions are: Are you concerned that the child will be exposed to pornography?; Are you concerned that the child will contact a stranger with sexual intentions?; Are you concerned that the child might be asked for sexual images of themselves or someone else?. The final score is formed by computing the sum of all items. The higher score indicates more parental concerns. The internal consistency of the scale is α = .812, standardised factor loadings are: .β = .907, .951, .957.

Parental Attitudes

This questionnaire includes 5 items, through which parents indicate their attitudes toward restrictive mediation strategies. Answers are on a scale from 1 (I completely agree) to 5 (I completely disagree). Higher responses indicate a more positive attitude toward restrictions. An example of an item is: It would take away my child’s autonomy to decide for themselves. The final result is formed by computing the mean of all items. The higher score indicates more positive attitudes towards restrictive strategies. CFA results show a good fit of the model, χ2 = 16.40, df = 5, p = .014 CFI = .991, TLI = .981, RMSEA = .057, 90% CIRMSEA [.02, .09], SRMR = .017, β = .569, .686, .707, .747, .824. The internal consistency of the scale is α = .834.

Parental Restrictive Strategies

This questionnaire comprises four items concerning the restrictions parents place on their children’s online activities. The response options are as follows: 1 (My child is always allowed); 2 (My child is allowed only when they ask or in my presence); 3 (My child is never allowed). Response My child is always allowed (1) was recoded in 0 (no mediation) and responses 2 and 3 were recoded to 1 (mediation applies; EU Kids Online, 2014). An example of an item is: Is your child allowed to use a social network (e.g., Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, Twitter)? The final score is formed by computing the sum of all items. The higher score indicates more restrictions imposed by parents. CFA results show a good fit of the model, χ2 = 0.427, df = 1, p = .513, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, 90% CIRMSEA [.00, .13], SRMR = .003, β = .770, .770, .777, .813. The internal consistency of the scale is α = .871.

Parental Active Strategies

This questionnaire includes 7 items regarding active mediation strategies parents employ. Answers are on a scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very often). Example of an item: How often do you suggest ways to use the internet safely?. The final score is formed by computing the mean of all items. The higher score indicates more frequent use of active strategies. CFA results show a good fit of the model, χ2 = 40.01, df = 10, p < .001 CFI = .982, TLI = .963, RMSEA = .064, 90% CIRMSEA [.04, .09], SRMR = .027, β = .501, .508, .558, .706, .708, .712, .762. The internal consistency of the scale is α = .834.

Parental Monitoring Strategies

This questionnaire includes 5 items regarding monitoring mediation strategies parents employ. Answers are on a scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very often). Example of an item: How often do you check the messages in his/her email or another communication app? The final score is formed by computing the mean of all items. The higher score indicates more frequent use of monitoring strategies. CFA results show a good fit of the model, χ2 = 11.499, df = 4, p = .037, CFI = .993, TLI = .982, RMSEA = .062, 90% CIRMSEA [.00, .08], SRMR = .019, β = .593, .714, .754, .783, .825. The internal consistency of the scale is α = .858.

Parental Awareness

Parental awareness is a composite variable that combines parental and child statements regarding the occurrence of child receipt of sexual messages and being asked about sexual matters in the past year.

For investigating the reception of sexual messages children responded to the questions: On the internet, have you received sexual messages in the last year? with responses coded as 0 (No) or 1 (Yes), and On the internet, how often have you been asked about sexual things in the last year? with responses ranged from 1 (Never) to 5 (Every day or almost every day). The responses to this second question were dichotomised, with response 1 (Never) recoded as 0 (No) and responses 2–5 recoded as 1 (Yes), indicating whether they were asked about sexual things in the last year.

To examine parental reports of their children receiving sexual messages, the following questions were posed: In the last year, has the child experienced on the internet: received a sexual message in the last year? and asked for sexual information about themselves in the last year? The responses were dichotomous, coded as 0 (No) and 1 (Yes).

The initial composite variable had three possible outcomes: 0 (both the child and parent reported that it did not happen); 1 (there is a discrepancy between the parent and child’s responses); 2 (both the parent and child reported that it happened). These responses were then recoded as follows: 0 (discrepancy in responses exists); 1 (no discrepancy in responses). The final score is formed by computing the mean of two items. A higher score indicates higher parental awareness. Recalling the frequency of events over a year can be challenging and prone to recall bias (Fenton, 2001). Therefore, it is decided to measure parental awareness of occurrence to limit recall bias associated with examining the frequency of experience. The internal consistency of the scale is α = .662, standardised factor loadings are: β = .688 and .747

Data Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS 25 and R, statistical package Lavaan. Descriptive statistics were used to measure participants’ sexting behaviours, parental concerns and positive attitudes toward restrictions, parental mediation strategies and parental awareness of a child’s receipt of sexual messages. The two-way ANOVA was used to examine differences between boys and girls and age groups of children. For testing the relationship between studied variables Multigroup structural equation modelling was employed.

Results

In Table 1, the results of the Pearson correlation test are displayed. Weak correlations were found between parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences and parental active and monitoring mediation strategies. Weak correlations were found between parental positive attitudes towards the use of restrictive strategies and the use of active and monitoring strategies. Medium correlations were found between parental attitudes towards the use of restrictive strategies and the use of restrictive strategies. Additionally, weak correlations were found between active strategies and parental awareness of a child’s receipt of sexual messages, as well as between restrictive strategies and parental awareness of a child’s receipt of sexual messages.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study Variables.

|

|

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1. Concerns |

0.98 |

1.246 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

2. Attitudes |

2.73 |

0.971 |

.022 |

— |

|

|

|

|

3. Active strategies |

2.67 |

0.744 |

.119** |

.283** |

— |

|

|

|

4. Restrictive strategies |

1.70 |

1.986 |

−.048 |

.347** |

.422** |

— |

|

|

5. Monitoring strategies |

1.95 |

0.837 |

.170** |

.281** |

.344** |

.346** |

— |

|

6. Parental awareness |

0.76 |

0.380 |

−.096* |

.157** |

.241** |

.277** |

.006 |

|

Note. *p < .05; **p < .01; M = Mean; SD = Standard deviation; n = Sample size. |

|||||||

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of the Variables Studied Divided by Gender and Age Group.

|

Variable |

Age group (12–14) |

Age group (15–17) |

||||||

|

Boys (n = 168) |

Girls (n = 168) |

Boys (n = 192) |

Girls (n = 182) |

|||||

|

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

|

Concerns |

0.88 |

1.22 |

1.21 |

1.30 |

0.51 |

0.94 |

1.36 |

1.33 |

|

Active strategies |

2.87 |

0.63 |

2.99 |

0.68 |

2.36 |

0.78 |

2.50 |

0.69 |

|

Restrictive strategies |

2.67 |

1.98 |

2.87 |

2.04 |

0.81 |

1.471 |

0.74 |

1.38 |

|

Monitoring strategies |

2.22 |

0.88 |

2.20 |

0.81 |

1.68 |

0.76 |

1.74 |

0.75 |

|

Sexting (child statements) |

0.26 |

0.57 |

0.27 |

0.55 |

0.70 |

0.82 |

0.70 |

0.75 |

|

Sexting (parent statements) |

0.05 |

0.27 |

0.171 |

0.50 |

0.19 |

0.48 |

0.37 |

0.72 |

|

Parental awareness |

0.84 |

0.33 |

0.84 |

0.31 |

0.68 |

0.41 |

0.68 |

0.43 |

|

Note. M = Mean; SD = Standard deviation; n = Sample size. |

||||||||

To test the age and gender differences, a two-way ANOVA was conducted, and the results are presented in Table 3. Additionally, a Bonferroni correction was applied to ensure that the cumulative Type I error remained below .05 (α divided by the number of comparisons: .05/28 = .0018). According to the data, parents express more concerns about online sexual experiences for girls than boys, F(1, 647) = 39.26, p < .001, which is predicted (H1a). No differences were found concerning the child‘s age, F(1, 647) = 1.41, p = .236, therefore, hypothesis (H2a) is not confirmed. A statistically significant interaction effect of the child‘s age and gender was identified, F(1, 647) = 7.89, p = .005, suggesting that parents are more concerned for older girls. However, after applying the Bonferroni correction, this effect was deemed insignificant (.005 > .0018).

Regarding mediation strategies, the only significant difference was in the use of active strategies more toward girls than boys, F(1, 709) = 6.57, p = .011. However, after Bonferroni correction, this difference is insignificant (.011 > .0018). Thus, hypothesis (H1b) is not confirmed, but cannot be completely disregarded in the part of applying more active strategies toward girls than boys. Furthermore, parents use active strategies, F(1, 709) = 90.37, p < .001, restrictive strategies, F(1, 670) = 223.49, p < .001, and monitoring strategies, F(1, 709) = 69.76, p < .001, more toward children aged 12 to 14 years than toward children aged 15 to 17 years. Thus, hypothesis (H2b) is confirmed.

Regarding sexting, older children receive more sexual messages than younger children, F(1, 681) = 69.49, p < .001, but no significant differences were found between girls and boys, F(1, 681) = 0.01, p = .928. Additionally, parents report that older children receive more sexual messages compared to younger ones, F(1, 609) = 15.26, p < .001, and believe that girls receive such messages more often than boys, F(1, 609) = 12.92, p < .001. There is no significant interaction effect of age and gender in terms of receiving sexual messages, F(1, 681) = 0.01, p = .937. Lastly, parents are more aware if younger children received sexual messages or not than older children, F(1, 609) = 27.80, p < .001.

Table 3. Gender and Sex Differences in the Studied Variables.

|

Variable |

|

Age group |

|

Gender |

|

Interaction (Age group*Gender) |

|||||||

|

|

F |

p |

df |

η² |

F |

p |

df |

η² |

F |

p |

df |

η² |

|

|

Concerns |

1.41 |

.263 |

1, 647 |

.002 |

39.26* |

<.001 |

1, 647 |

.058 |

7.89 |

.005 |

1, 647 |

.012 |

|

|

Active strategies |

90.37* |

<.001 |

1, 709 |

.114 |

6.57 |

.011 |

1, 709 |

.009 |

0.03 |

.862 |

1, 709 |

.000 |

|

|

Restrictive strategies |

223.49* |

<.001 |

1, 670 |

.251 |

0.60 |

.438 |

1, 670 |

.000 |

0.86 |

.353 |

1, 670 |

.002 |

|

|

Monitoring strategies |

69.76* |

<.001 |

1, 709 |

.090 |

0.09 |

.770 |

1, 709 |

.000 |

0.43 |

.513 |

1, 709 |

.001 |

|

|

Sexting (child statements) |

69.49* |

<.001 |

1, 681 |

.093 |

0.01 |

.928 |

1, 681 |

.000 |

0.01 |

.937 |

1, 681 |

.000 |

|

|

Sexting (parent statements) |

15.26* |

<.001 |

1, 609 |

.027 |

12.92* |

<.001 |

1, 609 |

.023 |

0.59 |

.444 |

1, 609 |

.001 |

|

|

Parental awareness |

27.80* |

<.001 |

1, 609 |

.044 |

0.03 |

.855 |

1, 609 |

.000 |

0.02 |

.884 |

1, 609 |

.000 |

|

|

Note. *Statistically significant difference after Bonferroni correction. |

|||||||||||||

Structural equation modelling was employed to analyse the relationship between parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences, parental positive attitudes about restrictive strategies, mediation strategies and parental awareness of a child’s receipt of sexual messages. Robust Maximum Likelihood served as the estimator for models encompassing various variables (Li, 2021). The findings indicate a favourable model fit (CFI = .965, TLI = .959, RMSEA = .035, SRMR = .045). Nevertheless, multigroup analysis between groups of 12–14 and 15–17 years old showed significant change in the Chi-square (Δχ² = 348.35, p < .001) when regression paths varied versus, they were constrained to be equal across groups. This implies significant moderation of age. Consequently, the results of multigroup SEM are shown. The tested model demonstrates a strong fit across age groups (CFI = .954, TLI = .946, RMSEA = .038, SRMR = .053).

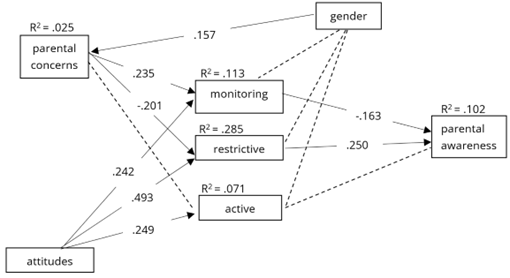

In Figure 1, a model with significant regression paths for younger children is presented. Dotted lines represent paths that lack a significant effect, and covariances among parental strategies are omitted for improved model clarity. Regarding the model for younger children (12–14 years old), gender is in a positive relationship with parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences (β = .157, p < .001), indicating that parents express more concerns for girls than boys. Further, parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences have in negative relationship with the use of restrictive strategies (β = −.201, p < .001), a positive relationship with the use of monitoring strategies (β = .235, p < .001), and no significant relationship with active mediation strategies. Therefore, hypothesis H3a is confirmed only in part that parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences would be correlated with applying monitoring strategies. The negative correlation between parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences and the use of restrictive strategies is contrary to predicted (H3a).

Positive attitudes towards restrictions are in a positive relationship with the use of restrictive mediation strategies (β = .493, p < .001) and monitoring strategies (β = .242, p < .001). Hypothesis (H4a) is confirmed in this age group. Positive attitudes towards restrictions are in a positive relationship with active strategies (β = .249, p < .001). Therefore, the hypothesis (H4b) is not confirmed.

The use of restrictive strategies has a positive relationship with parental awareness of child sexual message receipt (β = .278, p < 0.001). Thus, hypothesis H5a is confirmed. There is no significant relationship between active mediation and parental awareness of child sexual message receipt, meaning that hypothesis (H5b) is not confirmed. The use of monitoring strategies has a negative relationship with parental awareness (β = −.166, p = .050) which is contrary to predicted (H5d). Gender explains a 2.5% variance of parental concerns. Parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences and positive attitudes toward restrictions explain 28.5% variance of the use of restrictive strategies, 11% of monitoring strategies and 7% of active strategies. This set of predictors explains 10% of the variance of parental awareness of a child’s sexual message receipt in the younger group.

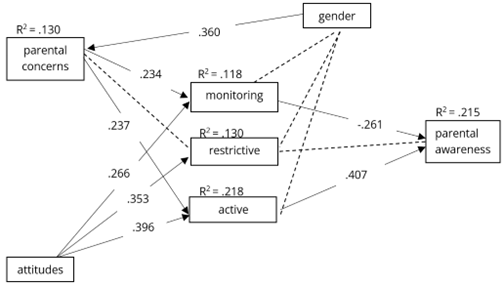

The model for older children is represented in Figure 2. In the model for older children (15–17 years old), gender has a positive relationship with parental concerns (β = .360, p < .001), indicating that parents harbour more concerns for girls than boys. Parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences are in a positive relationship with the use of active mediation strategies (β = .237, p < .001). Hypothesis (H3b) is confirmed. Additionally, parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences are positively related to monitoring strategies (β = .234, p < .001).

Positive attitudes towards restrictions are in a positive relationship with the use of restrictive mediation strategies (β = .353, p < .001) and monitoring strategies (β = .266, p < .001) which is predicted (H4a). Positive attitudes towards restrictions are in a positive relationship with the use of active strategies (β = .396, p < .001), which is contrary to predicted (H4b). In relation to RQ1, no age differences were found in the examined models.

Active strategies have a positive relationship with parental awareness of child sexual message receipt (β = 0.407, p < .001) while there is no significant relationship between restrictive strategies and parental awareness of child’s sexual message receipt which is in accordance with predicted (H5c). Monitoring strategies have a negative relationship with parental awareness of child sexual message receipt (β = −0.261, p = .050). Therefore, hypothesis (H5e) is confirmed.

Gender explains a 13% variance of parental concerns. Parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences and positive attitudes toward restrictions explain 13% variance of the use of restrictive strategies, 12% of monitoring strategies and 22% of active strategies. This set of predictors explains 21.5% of the variance of parental awareness about a child’s sexual message receipt in the older group.

Figure 1. Children 12–14 Years Old.

Figure 2. Children 15–17 Years Old.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between parental concerns about children’s receipt of sexual messages and their positive attitudes towards restrictions with specific mediation strategies. Furthermore, it explored how these mediation strategies are related to the parental awareness of their children receiving sexually explicit messages.

The findings suggest that parents have equal concerns about their child’s online sexual experiences, irrespective of child’s age which is contrary to findings from other studies (Boyd & Hargittai, 2013). A possible explanation is that factors such as parental perceptions of parenting, children as sensation seekers, and the perception of severity of online sexual risks are better predictors of parental concerns than child age (Byrne et al., 2014; Eelmaa, 2023). However, these assumptions need more research. Further, there is a higher parental worry towards girls than boys and parents of girls report that they have received messages of a sexual nature to a greater extent than parents of boys. These findings align with results reported by Sorbring (2014), who found that parents harbour more concerns about inappropriate exposure among girls than boys. In addition, Sorbring et al. (2014) point out that parents demonstrate a higher level of acceptance towards online sexual behaviours exhibited by boys as compared to girls. These results suggest the existence of double standards when it comes to evaluating girls’ sexual behaviour. To exemplify this point, Lippman and Campbell (2014) observe that societal expectations place significant pressure on girls to engage in sexting. Refusal to participate may result in being branded as “prudes”, whereas participation exposes them to potential moral condemnation. In addition, the media discourse on online sexual risks is gendered and promotes the perception of vulnerability of girls (Dedkova & Mylek, 2022). It is possible that parents are aware of this and therefore express more concerns about children’s online sexual experiences for girls than for boys.

Although parents express more concerns for girls than boys, parents equally employ mediation strategies towards boys and girls, except active mediation which was marginally significantly higher toward girls. This finding is in contrast with findings from other studies (Dedkova & Mylek, 2022; Dedkova & Smahel, 2020; Symons et al., 2017; Talves & Kalmus, 2015). A possible explanation for the finding in this study is a noticeable shift from restrictive strategies to active strategies (Kalmus et al., 2022). This is important to mention as employing restrictive strategies was found to be more focused on girls than boys (Paus-Hasebrink et al., 2012). Thus, reducing restrictions might be in favour of a more egalitarian approach to parenting where parents more equally employ mediation strategies toward girls and boys, but this should be addressed in future works (Kalmus et al., 2022). Further, it was found that parents apply more strategies towards younger than older children. This is in alignment with previous works (Dedkova & Smahel, 2020; Symons et al., 2017). As mentioned earlier, parents might perceive older children as more autonomous and skilled, thus giving them more freedom and using less mediation strategies (Symons et al., 2017).

This research shows that parents with more concerns about their child’s online sexual experiences employ more mediation strategies, as well as parents with more positive attitudes toward restrictions. These findings are in line with previous research that also examined the relationship between attitudes, parental concerns and mediation strategies, thus providing support for both the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Protection Motivation Theory (Boniel-Nissim, et al., 2020; Cingel & Krcmar, 2013; Krcmar & Cingel, 2016). An interesting finding is that positive attitudes towards restrictions are positively associated with active strategies as well. A possible explanation lies in the intercorrelation of active and restrictive strategies. German parents are high in implementing both active and restrictive strategies (Glüer & Lohaus, 2018), although there is an increase in the use of active and a decrease in restrictive strategies (Kalmus et al., 2022). It should be noted that no differences in the relationship between attitudes and mediation strategies were found. It may be that child’s age is predictor, rather than moderator of these relationships, but further studies are needed.

However, relationships differ regarding child age. Parental concerns about a child’s online sexual experiences are associated with fewer restrictions and more monitoring in the younger group, and more monitoring and active mediation in the older group. These findings may indicate parental ambivalence in employing mediation strategies. Parents may recognise child autonomy needs, thus not implementing restrictions (Young et al., 2024). At the same time, parents want to be knowledgeable about potential risks, thereby checking children’s messages or social media. As Hawk et al. (2015) state, monitoring may be more employed when is not likely that the child will self-disclose information. Earlier was mentioned that only 9% of youth engaged in conversation about online sexual behaviour with parents (Widman et al., 2021). Therefore, it is questionable which strategies should parents employ to gain knowledge about children’s sexual behaviour.

Results show that restrictive mediation is positively associated with parental awareness about child sexual messages receipt in younger group. The finding is similar to previous work by Kuldas et al. (2023) but in contrast with the finding of Geržičáková et al. (2023). It should be noted that previous work did not examine children’s sexual messages receipt which becomes more prevalent as children age. Younger children in this sample express less occurrence of receiving sexual messages than older ones, which may be due to more restrictions that parents employ towards them (Corcoran et al., 2022). Hence, parents accurately report that children did not receive sexual messages (Kuldas et al., 2023).