Reducing transphobia with the narratives of transgender YouTubers

Vol.18,No.5(2024)

YouTube has emerged as a valuable resource for trans people to get themselves heard. It also has the potential to help mainstream audiences to understand more about transgender’s lives. Following Contact, Narrative Persuasion, and Queer Intercultural Theories, two experiments were conducted among cisgender people to investigate which types of narratives (positive, neutral, or negative) shared by trans YouTubers are more effective for reducing prejudice towards trans people, and whether this effect depends on the YouTuber’s gender (Study 1) and/or their ethnic background (Study 2). Results from Study 1 (N = 254) show that negative narratives mediate the reduction of prejudice through narrative transportation, empathy, and intergroup anxiety. Trans women’s narratives are more effective for prejudice reduction. Study 2 (N = 161) replicates these findings and shows that xenophobia moderates the aforesaid effect if trans YouTubers are from different nationalities. Consequently, different prejudices might interact in the reception of LGBTQ+ narratives.

YouTubers; narrative persuasion; intergroup contact; intersectionality; transgender; transphobia; xenophobia

Isabel Rodríguez-de-Dios

Department of Sociology and Communication, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain

Isabel Rodríguez-de-Dios is a Ramón y Cajal Research Fellow at the Department of Sociology and Communication at the University of Salamanca. Her research focuses on youth and media, media psychology and narrative persuasion.

María T. Soto-Sanfiel

Department of Communications and New Media and Centre for Trusted Internet and Community, National University of Singapore, Singapore

María T. Soto-Sanfiel is a PhD in Audiovisual Communication and Associate Professor at the Department of Communications and New Media in the National University of Singapore (NUS), where she is also a Principal Researcher of the Centre for Trusted Internet and Community.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

Altavilla, D., Adornetti, I., Chiera, A., Deriu, V., Acciai, A., & Ferretti, F. (2022). Introspective self-narrative modulates the neuronal response during the emphatic process: An event-related potentials (ERPs) study. Experimental Brain Research, 240(10), 2725–2738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-022-06441-4

Amichai-Hamburger, Y., & McKenna, K. Y. A. (2006). The contact hypothesis reconsidered: Interacting via the internet. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(3), 825–843. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00037.x

Anderson, V. N. (2023). What does transgender mean to you? Transgender definitions and attitudes toward trans people. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 10(4), 600–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000566

Appel, M., & Richter, T. (2010). Transportation and need for affect in narrative persuasion: A mediated moderation model. Media Psychology, 13(2), 101–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213261003799847

Baker, J. O., Cañarte, D., & Day, L. E. (2018). Race, xenophobia, and punitiveness among the American public. The Sociological Quarterly, 59(3), 363–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380253.2018.1479202

Banas, J. A., Bessarabova, E., & Massey, Z. B. (2020). Meta-analysis on mediated contact and prejudice. Human Communication Research, 46(2–3), 120–160. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqaa004

Bandini, E., & Maggi, M. (2014). Transphobia. In G. Corona, E. Jannini, & M. Maggi (Eds.), Emotional, physical and sexual abuse (pp. 49–59). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06787-2_4

Bettinsoli, M. L., Suppes, A., & Napier, J. L. (2020). Predictors of attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women in 23 countries. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(5), 697–708. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619887785

Billard, T. J. (2019). Experimental evidence for differences in the prosocial effects of binge-watched versus appointment-viewed television programs. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 96(4), 1025–1051. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699019843856

Braddock, B., & Dillard, J. P. (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Communication Monographs, 83(4), 446–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2015.1128555

Bresnahan, M., Yan, X., Zhu, X., & Hussain, S. A. (2019). The impact of narratives on attitudes toward Muslim immigrants in the U.S. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 48(4), 400–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2019.1649294

Britt, T. W., Bonieci, K. A., Vescio, T. K., Biernat, M., & Brown, L. M. (1996). Intergroup anxiety: A person× situation approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(11), 1177–1188. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672962211008

Bustos Martínez, L., Santiago Ortega, P. P., Martínez Miró, M. A., & Rengifo Hidalgo, M. S. (2019). Discursos de odio: una epidemia que se propaga en la red. Estado de la cuestión sobre el racismo y la xenofobia en las redes sociales [Hate speech: an epidemic spreading online. State of the art on racism and xenophobia on social media]. Mediaciones Sociales, 18, 25–42. https://doi.org/10.5209/meso.64527

Cannon, Y., Speedlin, S., Avera, J., Robertson, D., Ingram, M., & Prado, A. (2017). Transition, connection, disconnection, and social media: Examining the digital lived experiences of transgender individuals. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 11(2), 68–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2017.1310006

Cao, C., & Meng, Q. (2020). Chinese university students’ mediated contact and global competence: Moderation of direct contact and mediation of intergroup anxiety. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 77, 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.03.002

Capuzza, J. C., & Spencer, L. G. (2016). Regressing, progressing, or transgressing on the small screen? Transgender characters on US scripted television series. Communication Quarterly, 65(2), 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2016.1221438

Cervantes, L., Navas, M., & Cuadrado, I. (2019). Contacto intergrupal y actitudes en bibliotecas públicas: un estudio con usuarios marroquíes y españoles en Barcelona y Almería [Intergroup contact and attitudes in public libraries: a study with Moroccan and Spanish users in Barcelona and Almería]. Revista Española de Documentación Científica, 42(1), Article e227. https://doi.org/10.3989/redc.2019.1.1581

Chávez, K. R. (2013). Pushing boundaries: Queer Intercultural Communication. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 6(2), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2013.777506

Collins, P. H. (2015). Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142

Craig, S. L., & McInroy, L. (2014). You can form a part of yourself online: The influence of new media on identity development and coming out for LGBTQ youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 18(1), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2013.777007

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Chung, A. H., & Slater, M. D. (2013). Reducing stigma and out-group distinctions through perspective-taking in narratives. Journal of Communication, 63(5), 894–911. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12050

Crush, J., & Ramachandran, S. (2010). Xenophobia, international migration and development. Journal of Human Development & Capabilities, 11(2), 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452821003677327

Davis, M. H., Luce, C., & Kraus, S. J. (1994). The heritability of characteristics associated with dispositional empathy. Journal of Personality, 62(3), 369–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00302.x

De Graaf, A., Sanders, J., & Hoeken, H. (2016). Characteristics of narrative interventions and health effects: A review of the content, form, and context of narratives in health-related narrative persuasion research. Review of Communication Research, 4, 88–131. https://rcommunicationr.org/index.php/rcr/article/view/43/43

Detenber, B. H., Ho, S. S., Neo, R. L., Malik, S., & Cenite, M. (2013). Influence of value predispositions, interpersonal contact, and mediated exposure on public attitudes toward homosexuals in Singapore. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 16(3), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12006

Eguchi, S. (2021). On the horizon: Desiring global queer and trans* studies in international and intercultural communication. Journal of International & Intercultural Communication, 14(4), 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2021.1967684

Eguchi, S., & Calafell, B. M. (2023). Queer relationalities, impossible: The politics of homonationalism and failure in LOGO’s Fire Island. Journal of Homosexuality, 70(1), 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2022.2103873

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146

Flores, A. R., Haider-Market, D. P. Lewis, D. C. Miller, P. R., Tadlock, B. L., & Taylor, J. K. (2017). Challenged expectations: Mere exposure effects on attitudes about transgender people and rights. Political Psychology, 39(1), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12402

Garcia, J. L. A. (2020). Racism and the discourse of phobias: Negrophobia, xenophobia and more. Dialogue with Kim and Sundstrom. Philosophical Exchanges. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12648/7164

Gazzola, S. B., & Morrison, M. A. (2014). Cultural and personally endorsed stereotypes of transgender men and transgender women: Notable correspondence or disjunction? International Journal of Transgenderism, 15(2), 76–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2014.937041

Graci, M. E., Watts, A. L., & Fivush, R. (2018). Examining the factor structure of narrative meaning-making for stressful events and relations with psychological distress. Memory, 26(9), 1220–1232. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2018.1441422

Green, M., Bobrowicz, A., & Ang, C. S. (2015). The lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community online: Discussions of bullying and self-disclosure in YouTube videos. Behaviour & Information Technology, 34(7), 704–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2015.1012649

Green, M., & Brock, T. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Guerrero-Martín, I., & Igartua, J. J. (2021). Reduction of prejudice toward unaccompanied foreign minors through audiovisual narratives. Effects of the similarity and of the narrative voice. Profesional de la Información, 30(2), Article e300203. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2021.mar.03

Hartmann, T., & Goldhoorn, C. (2011). Horton and Wohl revisited: Exploring viewers’ experience of parasocial interaction. Journal of Communication, 61(6), 1104–1121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01595.x

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd. ed.). The Guilford Press.

Hill, D. B., & Willoughby, B. L. B. (2005). The development and validation of the genderism and transphobia scale. Sex Roles, 53(7–8), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-7140-x

Igartua, J. J., & Cachón-Ramón, D. (2023). Personal narratives to improve attitudes towards stigmatized immigrants: A parallel-serial mediation model. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 26(1), 96–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211052511

Igartua, J. J., Guerrero-Martín, I., Cachón-Ramón, D., & Rodríguez-De-Dios, I. (2018). Efecto de la similitud con el protagonista de narraciones contra el racismo en las actitudes hacia la inmigración: el rol mediador de la identificación con el protagonista [Effect of similarity with the protagonist in anti-racism narratives on attitudes toward immigration: the mediating role of identification with the protagonist]. Disertaciones. Anuario Electrónico de Estudios de Comunicación Social, 11, 56–75. https://doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/disertaciones/a.5272

Jenzen, O. (2022). LGBTQ youth cultures and social media. In S. Munt (Ed.), The Oxford encyclopedia of queer studies. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.1363

Johnson, A. H. (2016). Transnormativity: A new concept and its validation through documentary film about transgender men. Sociological Inquiry, 86(4), 465–491. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1111/soin.12127

Johnson, D. R. (2012). Transportation into a story increases empathy, prosocial behaviour, and perceptual bias toward fearful expressions. Personality & Individual Differences, 52(2), 150–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.005

Johnson, D. R. (2013). Transportation into literary fiction reduces prejudice against and increases empathy for Arab-Muslims. Scientific Study of Literature, 3(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1075/ssol.3.1.08joh

Ju, H., Park, S. Y., Shim, J. C., & Ku, Y. (2016). Mediated contact, intergroup attitudes, and ingroup members’ basic values: South Koreans and migrant workers. International Journal of Communication, 10, 1640–1659. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/3883

Kim, N., & Lim, C. (2022). Meeting of minds: Narratives as a tool to reduce prejudice toward stigmatized group members. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(6), 1478–1495. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211012783

Li, M. (2019). Mediated vicarious contact with transgender people: How narrative perspective and interaction depiction influence intergroup attitudes, transportation, and elevation. Journal of Public Interest Communications, 3(1), 141–166. https://doi.org/10.32473/jpic.v3.i1.p141

Lucero, L. (2017). Safe spaces in online places: Social media and LGBTQ youth. Multicultural Education Review, 9(2), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2017.1313482

Madžarević, G., & Soto-Sanfiel, M. T. (2018). Positive representation of gay people for reducing homophobia. Sexuality & Culture, 22(3), 909–930. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-018-9502-x

Madžarević, G., & Soto-Sanfiel, M. T. (2019). Reducing homophobia in college students through film appreciation. Journal of LGBT Youth, 16(1), 18–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2018.1524321

Massey, Z. B., Wong, N. C. H., & Barbati, J. L. (2021). Meeting the (trans)parent: Test of parasocial contact with transgender characters on reducing stigma toward transgender people. Communication Studies, 72(2), 232–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2021.1876125

Mastro, D., & Tukachinsky, R. (2011). The influence of exemplar versus prototype-based media primes on racial/ethnic evaluations. Journal of Communication, 61(5), 916–937. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01587.x

McDermott, D. T., Brooks, A. S., Rohleder, P., Blair, K., Hoskin, R. A., & McDonagh, L. K. (2018). Ameliorating transnegativity: Assessing the immediate and extended efficacy of a pedagogic prejudice reduction intervention. Psychology & Sexuality, 9(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2018.1429487

McMickens, T., Olzman, M. D., & Calafell, B. M. (2021). Queer intercultural communication: Sexuality and intercultural communication. In Oxford research encyclopedia of communication. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.1177

Miller, B. (2017). YouTube as educator: A content analysis of issues, themes, and the educational value of transgender-created online videos. Social Media + Society, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117716271

Monteiro, D., & Poulakis, M. (2019). Effects of cisnormative beauty standards on transgender women’s perceptions and expressions of beauty. Midwest Social Sciences Journal, 22(1), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.22543/2766-0796.1009

Mulak, A., & Winiewski, M. H. (2021). Virtual contact hypothesis: Preliminary evidence for intergroup contact hypothesis in interactions with characters in video games. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 15(4), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2021-4-6

Murphy, S. T., Frank, L. B., Chatterjee, J. S., & Baezconde-Garbanati, L. (2013). Narrative versus nonnarrative: The role of identification, transportation, and emotion in reducing health disparities, Journal of Communication, 63(1), 116–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12007

National Center for Transgender Equality (2016). Understanding Transgender People. The basics. https://transequality.org/issues/resources/understanding-transgender-people-the-basics.

Olonisakin, T. T., & Adebayo, S. O. (2021). Xenophobia: Scale development and validation. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 39(3), 484–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2020.1853686

Orellana, L., Totterdell, P., & Iyer, A. (2020). The association between transgender-related fiction and transnegativity: Transportation and intergroup anxiety as mediators. Psychology & Sexuality, 13(2), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2020.1759677

Ortiz, M., & Harwood, J. (2007). A social cognitive theory approach to the effects of mediated intergroup contact on intergroup attitudes. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 51(4), 615–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150701626487

Páez, J., Hevia, G., Pesci, F., & Rabbia, H. H. (2015). Construction and validation of a negative attitudes toward trans people scale. Revista de Psicología, 33(1), 153–190. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.201501.006

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 751–783. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta‐analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(6), 922–934. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.504

Pettigrew, T. F., Tropp, L. R., Wagner, U., & Christ, O. (2011). Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(3), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. Springer-Verlag.

Pew Research Centre (2020, June 25). The Global Divide on Homosexuality Persists. Pew Research Centre. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/06/25/global-divide-on-homosexuality-persists/

Restrepo Pineda, J. R. (2020). Vulnerability to HIV/AIDS in gay and bisexual individuals during migration: The case of Colombian immigrants residing in Spain. Saúde e Sociedade, 29(3), Article e190298. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-12902020190298

Ronda-Pérez, E., Martínez, J. M., Reid, A., & Agudelo-Suárez, A. A. (2019). Longer residence of Ecuadorian and Colombian migrant workers in Spain associated with new episodes of common mental disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(11), Article 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16112027

Roussos, G., & Dovidio, J. F. (2016). Playing below the poverty line: Investigating an online game as a way to reduce prejudice toward the poor. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 10(2), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2016-2-3

Schiappa, E., Gregg, P. B., & Hewes, D. E. (2005). The parasocial contact hypothesis. Communication Monographs, 72(1), 92–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/0363775052000342544

Schiappa, E., Gregg, P. B., & Hewes, D. E. (2006). Can one TV show make a difference? A Will & Grace and the parasocial contact hypothesis. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(4), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v51n04_02

Shen, L. (2010). On a scale of state empathy during message processing. Western Journal of Communication, 74(5), 504–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2010.512278

Silván-Ferrero, M. P. (2006). Actitudes hacia la discapacidad: ambivalencia afectiva, ansiedad e interferencia en la comunicación [Attitudes toward disability: affective ambivalence, anxiety, and communication interference]. [Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia].

Singh, A. A. (2013). Transgender youth of color and resilience: Negotiating oppression and finding support. Sex Roles, 68(11), 690–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0149-z

Skidmore, E. (2011). Constructing the ”good transsexual”: Christine Jorgensen, whiteness, and heteronormativity in the mid-twentieth-century press. Feminist Studies, 37(2), 270–300. https://doi.org/10.1353/fem.2011.0043

Slater, M. D., & Rouner, D. (2002). Entertainment-education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Communication Theory, 12(2), 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00265.x

Solomon, H. E., & Kurtz-Costes, B. (2018). Media’s influence on perceptions of trans women. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15(1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0280-2

Stephan, W. G. (2014). Intergroup anxiety: Theory, research, and practice. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(3), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314530518

Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (1985). Intergroup anxiety. Journal of Social Issues, 41(3), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb01134.x

Stryker, S. (2017) Transgender history: The roots of today’s revolution. Seal Press.

Sundstrom, R. R., & Kim, D. H. (2014). Xenophobia and racism. Critical Philosophy of Race, 2(1), 20–45. https://doi.org/10.5325/critphilrace.2.1.0020

Tafira, K. (2011). Is xenophobia racism? Anthropology Southern Africa, 34(3–4), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/23323256.2011.11500015

Terriquez, V. (2015). Intersectional mobilization, social movement spillover, and queer youth leadership in the immigrant rights movement. Social Problems, 62(3), 343–362. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spv010

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2017). Learning to live together. https://wayback.archive-it.org/10611/20171126022534/http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/international-migration/glossary/xenophobia/

van Laer, T., de Ruyter, L., Visconti, L. M., & Wetzels, M. (2014). The extended transportation-imagery model: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of consumers’ narrative transportation. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(5), 797–817. https://doi.org/10.1086/673383

Vescio, T. K., Sechrist, G. B., & Paolucci, M. P. (2003). Perspective taking and prejudice reduction: the mediational role of empathy arousal and situational attributions. European Journal of Social Pyschology, 33(4), 455–472. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.163

Vezzali, L., Hewstone, M., Capozza, D., Giovannini, D., & Wölfer, R. (2014). Improving intergroup relations with extended and vicarious forms of indirect contact. European Review of Social Psychology, 25(1), 314–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2014.982948

Villegas-Simón, I., Sánchez Soriano, J. J., & Ventura, R. (2024). ‘If you don’t “pass” as cis, you don’t exist’. The trans audience’s reproofs of ’cis gaze’ and transnormativity in TV series. European Journal of Communication, 39(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231231163704

Visintin, E. P., Voci, A., Pagotto, L., & Hewstone, M. (2017). Direct, extended, and mass‐mediated contact with immigrants in Italy: Their associations with emotions, prejudice, and humanity perceptions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 47(4), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12423

Voci, A., & Hewstone, M. (2003). Intergroup contact and prejudice toward immigrants in Italy: The mediational role of anxiety and the moderational role of group salience. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 6(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430203006001011

Walkington, Z., Wigman, S. A., & Bowles, D. (2020). The impact of narratives and transportation on empathic responding. Poetics, 80, Article 101425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2019.101425

Walter, N., Murphy, S. T., Frank, L. B., & Baezconde-Garbanati, L. (2017). Each medium tells a different story: The effect of message channel on narrative persuasion. Communication Research Reports, 34(2), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2017.1286471

Wimmer, A. (1997). Explaining xenophobia and racism: A critical review of current research approaches. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 20(1), 17–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1997.9993946

Wong, N. C. H., Massey, Z. B., Barbati, J. L., Bessarabova, E., & Banas, J. A. (2022). Theorizing prejudice reduction via mediated intergroup contact: Extending the intergroup contact theory to media contexts. Journal of Media Psychology, 34(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000338

Worthen, M. G. (2013). An argument for separate analyses of attitudes toward lesbian, gay, bisexual men, bisexual women, MtF and FtM transgender individuals. Sex Roles, 68(11–12), 703–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0155-1

Zhang, E. (2022). “She is as feminine as my mother, as my sister, as my biologically female friends”: On the promise and limits of transgender visibility in fashion media. Communication, Culture & Critique, 16(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcac043

Zhao, L. (2016). Parasocial relationships with transgender characters and attitudes toward transgender individuals [Master’s thesis, Syracuse University]. SURFACE. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/553

Zhuang, J., & Guidry, A. (2022). Does storytelling reduce stigma? A meta-analytic view of narrative persuasion on stigma reduction. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 44(1), 23–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2022.2039657

Authors’ Contribution

Isabel Rodríguez-de-Dios: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. María T. Soto-Sanfiel: funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

September 14, 2023

Revision received:

July 4, 2024

Accepted for publication:

October 3, 2024

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

Transphobia has been described as aversion manifested in the form of prejudice, harassment, discrimination, victimization or violence toward trans1 individuals who do not conform to society’s normative gender expectations and openly manifest their gender identity (Bandini & Maggi, 2014). Following Villegas-Simón et al. (2024), irrespective of their gender expression or sexual orientation, transgender is an “umbrella term” (Stryker, 2017) encompassing all individuals whose gender identity differs from the one assigned to them at birth (National Center for Transgender Equality, 2016).

As a result of transphobia, many trans individuals view social media (e.g., YouTube) as a safe platform for interaction, learning and resource-sharing, particularly in their path to self-discovery (Cannon et al., 2017). They use social media for support, guidance and mutual learning with regard to their everyday circumstances and their transition experiences (Cannon et al., 2017). However, it is important to acknowledge the paradoxical nature of such digital and cultural practices of LGBTQ+ people on social networks: these spaces exist alongside hate speech and their access is influenced by economic factors, algorithmic exclusions on platforms, and neoliberal paradigms of gender and sexuality which prioritize individual choices and market-based preferences while overlook systemic inequalities and structural barriers (Jenzen, 2022).

YouTube as a Tool for Trans People’s Personal Narratives

Of the different social media platforms, YouTube has become a favourite for LGBTQ+ expression and visibility (Craig & McInroy, 2014; Lucero, 2017). Trans YouTubers openly disclose personal information and autobiographical experiences to connect not only with trans viewers but also with an unknown audience, suggesting a desire to seek friendship, support and empathy (Green et al., 2015). Indeed, trans vloggers mostly use this platform to deliver first-person narratives of their experiences of a wide variety of topics, such as gender identity, transitioning, and stigma from an autobiographical standpoint (Miller, 2017).

Trans YouTubers’ portrayals have also been noted for their educational value, aiding in the comprehension of trans individuals’ lives, issues, and challenges, particularly among transphobic mainstream audiences, who have limited exposure to trans perspectives elsewhere (Miller, 2017). These videos cover a range of topics, including how to interact with trans individuals, experiences in dating them, and strategies for being an ally. They humanize trans lives by sharing personal stories of transitioning and providing information on medical, psychological, or surgical treatments. Additionally, these videos address the prejudice faced by trans individuals and highlight the privileges enjoyed by cisgender individuals. Consequently, they could serve as a means to combat misconceptions and negative attitudes towards the trans community (Miller, 2017). However, to our knowledge, no research has empirically assessed the efficacy of the different trans YouTubers’ narratives for achieving these goals, although research has shown that trans portrayals do play a role in shaping attitudes towards the trans community. For instance, in a study by Flores et al. (2017), participants were presented with vignettes depicting trans individuals with varying facial images, each portraying different physical features associated with gender. The findings revealed that all participants exhibited decreased levels of discomfort and transphobia, which suggests that people generally lack familiarity with trans individuals, and exposure to their portrayals can effectively reduce prejudice. Moreover, Zhao (2016) conducted a survey that observed a positive correlation between developing a parasocial relationship with fictional trans characters and fostering more positive attitudes towards trans individuals. However, to fill such gap, this study aims to investigate whether narratives of transgender people who share their autobiographical experiences on YouTube have any effect on mainstream audiences’ level of prejudice towards trans people.

Narratives, a Powerful Tool for Reducing Prejudice

Evidence suggests that narratives are a powerful persuasion device for affecting attitudes and behavior (Braddock & Dillard, 2016) and reducing prejudice towards stigmatized people (e.g., Zhuang & Guidry, 2022) such as the LGBTQ+ community (Madžarević & Soto-Sanfiel, 2018, 2019; Schiappa et al., 2006). Research on narrative persuasion has observed the impact of stories on prejudice reduction from different angles, such as the narrative’s point of view, protagonist (de Graaf et al., 2016; Zhuang & Guidry, 2022) and content. Regarding point of view, studies demonstrate that first-person narratives (in which the narrator directly describes their personal experiences, as trans Youtubers do) are most effective at reducing prejudice (Kim & Lim, 2022; Zhuang & Guidry, 2022). In terms of the protagonist, there is some evidence that gay and lesbian individuals who are portrayed as kind, light-hearted or moralistic elicit positive responses and help to prejudice reduction (Madžarević & Soto-Sanfiel, 2018, 2019). Finally, regarding content, some studies have noted the impact of positive messages over negative ones on the reduction of bias (e.g., Bresnahan et al., 2019), although others also observe a positive impact of narratives describing negative experiences (e.g., Graci et al., 2018). Hence the need to continue studying the effect of the characteristics of the narrative on prejudice reduction (Bresnahan et al., 2019). This research responds to that need and aims to study which type of narrative (i.e., positive, neutral, or negative) results in a lower level of prejudice.

Theoretical Bases

The impact of narratives on prejudice has been observed from two theoretical approaches: the elaboration likelihood model (ELM; Petty & Cacioppo, 1986) and the contact theory (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006; Pettigrew et al., 2011). The ELM claims that narratives persuade individuals via two mechanisms that reduce the tendency to question, criticize or counterargue the message and consequently produce attitude change: transportation within the story and identification with the character’s emotions and thoughts (Green & Brock, 2000; Slater & Rouner, 2002). The ELM has recently been proposed as a model explaining the reduction of prejudice towards trans people through TV series (Billard, 2019). In turn, contact theory proposes that intergroup contact (the interaction between members of different social groups), soften inflexible attitudes towards outgroups (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew et al., 2011). Most intergroup contact research has studied face-to-face interactions but mediated intergroup contact (Vezzali et al., 2014) and internet or virtual contact (Amichai-Hamburger & McKenna, 2006; Mulak & Winiewski, 2021) have been gradually gaining academic attention as well. Hence, the parasocial contact hypothesis (Schiappa et al., 2005) posits that media can also elicit intergroup contact (i.e., mediated contact) and contribute to prejudice reduction (see Banas et al., 2020). Early work with this theory observed the impact of LGBTQ+ media fictional representations (Ortiz & Harwood, 2007; Schiappa et al., 2006, 2007), as also supported by recent studies (Li, 2019; Madžarević & Soto-Sanfiel, 2019; Massey et al., 2021).

The theories discussed offer insightful frameworks for understanding how narratives and mediated contact can be effectively used to reduce prejudice. First, the ELM demonstrates that narratives can decrease prejudice towards marginalized groups by transporting individuals in the story and fostering identification and empathy towards the character(s). Second, the contact theory highlights that contact between members of different social groups can diminish prejudice. The parasocial contact hypothesis extends this idea by suggesting that media representations can serve as a form of intergroup contact, thereby contributing to prejudice reduction.

(Mediated) Contact Theory: Intergroup Anxiety as a Mediator

Meta-analysis confirms that the most studied mediators of the relationship between contact and prejudice reduction are intergroup anxiety and empathy (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008). Intergroup anxiety is a negative affective process elicited by the thought of potential contact with a member of the outgroup or when there is direct contact with them (Stephan & Stephan, 1985). There is evidence that direct intergroup contact experiences alleviate intergroup anxiety, particularly when the contact is positive and meaningful (Cao & Meng, 2020). On the other hand, empathy fosters positive attitudes towards the outgroup (e.g., Vescio et al., 2003). The idea is that intergroup contact enhances knowledge about the outgroup, thus reducing anxiety and increasing empathy (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006).

In turn, the parasocial contact hypothesis (Schiappa et al., 2005) claims that mediated contact is processed in a similar manner to intergroup contact: the spectator belongs to an ingroup and the protagonist of a narrative is part of an outgroup. Media elicits direct contact between viewers and outgroup characters to the extent that the former might feel that the latter are talking to or addressing them directly (Hartmann & Goldhoorn, 2011). Research suggests that mediated contact fosters prejudice reduction, which is very useful when there is no possibility of direct intergroup contact (Guerrero-Martín & Igartua, 2021) or when such contact might produce uneasiness (Chung & Slater, 2013).

There is evidence that mediated contact with members of the outgroup produces prejudice reduction toward stigmatized populations, such as immigrants (Ju et al., 2016) and AIDS patients (Kim & Lim, 2022; see Wong et al., 2022 for a review). There is also evidence supporting prejudice reduction and attitude change as a result of mediated contact with LGBTQ+ people under certain conditions (Ortiz & Harwood, 2007; Schiappa et al., 2005, 2006) and more recently with transgender people (Li, 2019; Massey et al., 2021).

Narrative Transportation as a Mediator

Research on entertainment theory has consistently found that audio-visual narratives have a persuasive effect on attitude and behavioral change (Braddock & Dillard, 2016; Murphy et al., 2013) because they benefit immersion in the story (Walter et al., 2017) in accordance to the extended ELM (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986; Slater & Rouner, 2002). Furthermore, it has repeatedly been observed that narrative transportation produces attitude change and enduring persuasive effects (van Laer et al., 2014).

Narrative transportation has been described as the receivers’ mental state when completely absorbed or lost in a story (Green & Brock, 2000). According to previous research, narrative transportation is a mediator between empathy and the narrative (Appel & Richter, 2010; D. R. Johnson, 2012; van Laer et al., 2014) and between mediated contact and prejudice reduction (D. R. Johnson, 2013; Orellana et al., 2020). For instance, D. R. Johnson (2012, 2013) found that mediated contact with Muslims encouraged empathy and reduced prejudice through narrative transportation. Coherently, Igartua and Cachón-Ramón (2023) reported that greater narrative transportation towards immigrants’ personal stories reduced counterargument, which elicits more positive attitudes towards them.

On the other hand, recent research indicates that the type of narrative is meaningful for narrative transportation and, consequently, mediate the impact of portrayals of transgender people. Li (2019) observed that a narrative’s perspective of transgender people (cisgender-ingroups or transgender-outgroups) and its content (positive interaction vs negative interaction) affected narrative transportation and attitudes. The author found that the portrayal of a rewarding or positive experience related to a transgender person produces more cognitive involvement, emotional investment and empathy with that character, and also that transgender narratives are more effective for transporting individuals and producing attitude change. Li’s (2019) results were consistent with previous research regarding the impact of positive depictions on attitude change (i.e., Mastro & Tukachinsky, 2011). However, since the stimuli of the research consisted of transgender-cisgender interaction storylines narrated from transgender or cisgender perspectives, Li (2019) warned that these results did not mean that the portrayal of a negative interaction from a specific perspective would not produce positive attitudes as well. Thus, the author invited further observation of the impact of narrative content on the generation of positive attitudes to transgender people. This research answers that call.

Empathy as a Mediator

It is generally accepted that empathy involves interrelated affective and cognitive processes (Davis et al., 1994). Affective empathy implies the vicarious experience of another person’s emotional experiences whereas cognitive empathy refers to an understanding of someone else’s emotions and intellectual perspectives (Altavilla et al., 2022).

As introduced earlier, research on narrative persuasion has consistently shown that empathy is related to prejudice reduction because narrative transportation mediates/facilitates empathetic responses to stigmatized outgroups (Walkington et al., 2020). Receivers who are more transported into the fictional story present higher empathy with a character representing the outgroup. This, in turn, reduces stereotypical conceptions about the outgroup, thus producing fewer negative attitudes towards its members (D. R. Johnson, 2012; Roussos & Dovidio, 2016).

Empathy is also related to lower intergroup anxiety levels (Banas et al., 2020; Massey et al., 2021; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008; Stephan, 2014). Although both factors have been consistently considered mediators of prejudice reduction through intergroup contact and mediated contact (Banas et al., 2020; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008), other research specifies that empathy specifically mediates intergroup anxiety: higher empathy elicits lower levels of intergroup anxiety (Stephan, 2014). Consequently, although it is incontestable that empathy and intergroup anxiety are mediators of prejudice reduction, the exact nature of their relationship in mediated contact requires further investigation (Banas et al., 2020). This study intends to contribute to that.

A Model for Understanding the Impact of Transgender YouTubers

Based on the preliminary evidence, this research considers mediated contact (e.g., viewer’s contact with the member of the outgroup, the trans YouTuber, through media), narrative transportation (e.g., viewer’s immersion in the YouTuber’s narrative), empathy (e.g., viewer’s response to the YouTuber’s narrative) and intergroup anxiety (e.g., viewer’s anxiety towards the potential contact with a trans person) as relevant variables of transphobia reduction. Moreover, following Detenber et al. (2013), it also assumes that the impact of mediated contact with trans people on the reduction of intergroup anxiety and prejudice is higher in individuals who have had no previous contact with transgender people.

On the other hand, it is worth considering that preliminary empirical studies have examined responses to audiovisual depictions of specific transgender genders (Massey et al., 2021), focusing more on trans women (e.g., Li, 2019; Orellana et al., 2020). Mostly because trans men are underrepresented (Villegas-Simon et al., 2024). However, traditionally attitudes toward trans men and trans women are viewed as different (Worthen, 2013), with each experiencing prejudice differently across various contexts (Bettinsoli et al., 2020). This view is supported by recent research from Anderson (2023), despite some contradictory findings (Gazzola & Morrison, 2014). Hence, further exploration of attitudes toward both gender identities is necessary. Consequently, this research will consider the gender of the trans person as a variable.

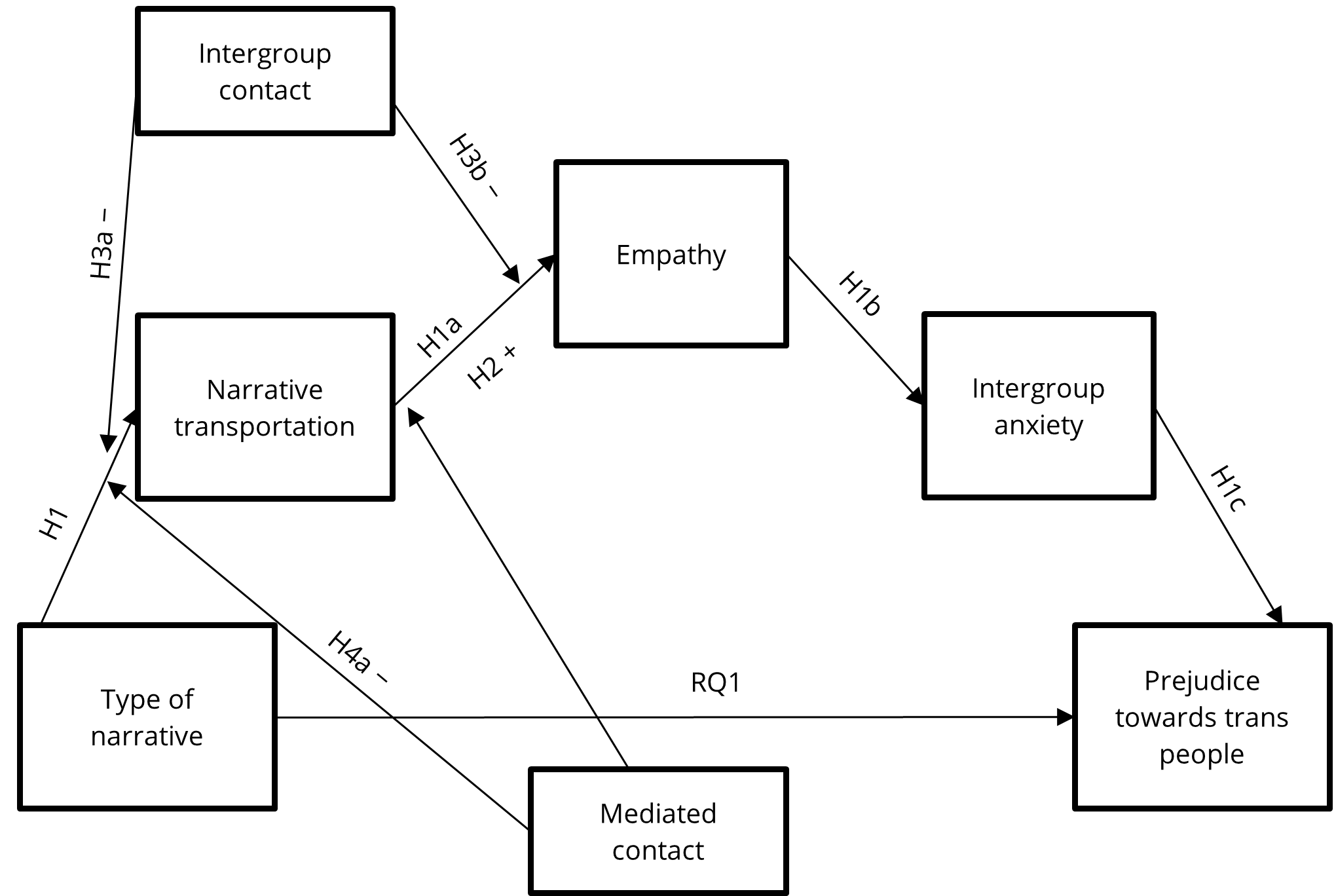

Thus, we propose the following hypotheses and research question, which are represented in the model shown in Figure 1, for transgender narratives on YouTube.

Figure 1. Hypothesized Model.

RQ1: What type of trans narrative on YouTube (positive, neutral, or negative) results in a lower level of prejudice towards transgender people?

H1: The effect of the narrative on prejudice towards trans people will be mediated by narrative transportation (H1a), empathy (H1b) and intergroup anxiety (H1c).

H2: The higher the level of narrative transportation experienced, the higher the level of empathy towards the trans youtuber.

H3: The effect of the type of narrative on narrative transportation (H3a) and empathy (H3b) will be stronger among those with less intergroup contact.

H4: The effect of the type of narrative on narrative transportation (H4a) and empathy (H4b) will be stronger among those with less mediated contact.

We also add an exploratory research question:

RQ2: Do audience members show similar responses to trans people of different gender?

From all the above, it can be seen that the main objective of this research is to propose and validate a model that explains the reduction of prejudice of cisgender individuals towards trans men and women who produce first-person narratives on YouTube. Additionally, the research aims to understand the impact of these narratives on prejudice reduction, depending on whether they tell positive (acceptance and inclusion), neutral (explaining everyday matters), or negative (rejection and discrimination) stories. All of this is addressed in the first study. To facilitate understanding, we will advance that this research includes a second study built upon the results of the first. The main objective of the second study is to replicate the model and to validate if it can be applied to explain the reduction of prejudice towards all trans people, regardless of other identity factors besides gender. Specifically, Study 2 examines the differing responses of cisgender individuals towards trans people of different nationalities, also taking into account their level of xenophobia.

Study 1

Methods

Participants

A sample of 254 cisgender people (67.7% cis men) aged 18 to 62 (M = 34.1 years, SD = 8.9) living in Spain participated in the online experiment. To establish the required sample size, a power analysis was conducted with G*Power (Faul et al., 2007). Based on previous meta-analyses that found effect sizes of r = .26 (mediated contact, Banas et al., 2020) and r = .19 (narrative persuasion; Braddock & James, 2016), we calculated the sample size for a medium effect size. Results indicated that a minimum sample size of 158 participants was required to have 80% power (α = .05) in a study with six groups (df = 2). Participants were recruited using MTurk (March–May 2022) and were paid 2.09 USD. Ethical approval was obtained from the National University of Singapore.

Materials and Procedure

A 3 (type of narrative) x 2 (gender of the YouTuber) between-subjects online experiment was conducted. Hence, six types of video were used as stimuli: three narratives (positive vs. neutral vs. negative) sharing the personal experiences of four trans YouTubers (2 male vs 2 female), which were similar in length (about 2 minutes) and visual composition (indoor location, framing and medium shot). The four YouTubers selected (two trans women and two trans men) self-identified as trans people in their content (i.e., title of the channel, title of the video or they verbally express it in the video). As for the type of narratives, positive narratives presented trans-inclusive experiences, neutral narratives included ordinary non-meaningful experiences not related with the trans experience, and negative ones portrayed transphobic experiences. A pilot study conducted with 100 adults aged 18 to 74 (M = 42.6; SD = 14.3) from a convenience sample validated the adequateness of the videos and unfamiliarity with the YouTuber (see Appendix A for more information about the stimulus material and the pilot study).

As for the main experiment, participants first completed a questionnaire, which assessed their socio-demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender identity, sexual orientation, and education) and the moderator variables (i.e., intergroup contact and mediated contact with trans people). They were then randomly assigned to one of the experimental conditions. After watching the entire video, participants were asked to answer a set of questions measuring empathy towards the protagonist, narrative transportation, intergroup anxiety, and prejudice towards trans people. Finally, participants were debriefed.

Measures

To measure intergroup contact with trans people (quantity and quality of contact) we used four items (e.g., How frequent is your contact with trans people?) on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = none to 5 = much, inspired by previous studies (Cervantes et al., 2019; Voci & Hewstone, 2003). These were averaged to create a scale (M = 2.58, SD = 0.95, α = .88). Likewise, to measure mediated contact with trans people (frequency and liking), we used three items (e.g., How often do you consume media content featuring trans people?) on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = none to 5 = much and taken from Cao and Meng (2020; M = 3.02, SD = 0.93, α = .81).

To assess empathy, we used eight items corresponding to two factors (cognitive and emotional) from the State Empathy Scale (Shen, 2010). Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they had experienced different aspects of empathy while watching the video (e.g., I could feel the protagonist’s emotions; M = 3.66, SD = 0.75, α = .88). To measure narrative transportation, nine items of Green and Brock’s (2000) scale were used (e.g., I was mentally implicated with the narrative told by the protagonist of the video; M = 3.26, SD = 0.61, α = .73). Likewise, to assess intergroup anxiety, 11 items from Britt et al.’s (1996) scale translated to Spanish by Silván-Ferrero (2006) were adapted (e.g., I don’t know what to expect from a trans person; M = 2.34, SD = 0.73, α = .93). Finally, to assess the level of prejudice towards trans people, nine items from the Scale of Negative Attitudes towards Trans People (EANT) translated into Spanish by Páez et al. (2015) were used (e.g., Sex with a trans person is not natural; M = .1.96, SD = 0.90, α = .93).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Random assignment to the six experimental conditions was successful. There were no statistically significant differences between the experimental groups in terms of gender, χ² (10, N = 254) = 14.253, p = .162, age, F(5, 248) = 0.612, p = .691, sexual orientation, χ² (15, N = 254) = 7.180, p = .952, or educational level,

χ² (25, N = 254) = 15.011, p = .941. Similarly, the experimental manipulation of gender was effective. Majority (90.2%) of participants responded correctly by appropriately identifying the YouTuber’s gender,

χ² (1, N = 254) = 164.371, p < 0.001.

Finally, the correlations between the mediating and dependent variables justify the mediation model formulated (see Table 1).

Table 1. Correlations Between the Mediating and the Dependent Variables (Study 1).

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

1 Empathy |

— |

|

|

|

|

2 Narrative transportation |

.728*** |

— |

|

|

|

3 Intergroup anxiety |

−.406*** |

−.360*** |

— |

|

|

4 Prejudice towards trans people |

−.461*** |

−.381*** |

.708*** |

— |

|

Note. ***p < .001. |

||||

Effects of the Narrative and the YouTuber’s Gender on the Level of Prejudice

To answer RQ1 and RQ2 a two-way ANOVA was conducted. Results show that there are not main effects for the type of narrative, F(2, 242) = 0.411, p = .663, η2 = .003, or the YouTuber’s gender, F(1, 242) = 0.026, p = .871, η2 = .000 on the level of prejudice. Moreover, the interaction effect between the type of narrative and the Youtuber’s gender was not statistically significant, F(2, 242) = 1.064, p = .347, η2 = .009.

To test the hypothesized moderated mediation model, we created a custom model in PROCESS v4.2 (Hayes, 2022) using the syntax function in SPSS. We employed 5,000 bootstrap samples with a 95% confidence interval. In this model, the type of narrative is the independent multicategorical variable (x); the mediators (m) are narrative transportation, empathy, and intergroup anxiety the mediators; the moderators are intergroup contact (w) and mediated contact (z); and the level of prejudice is the dependent variable (y).

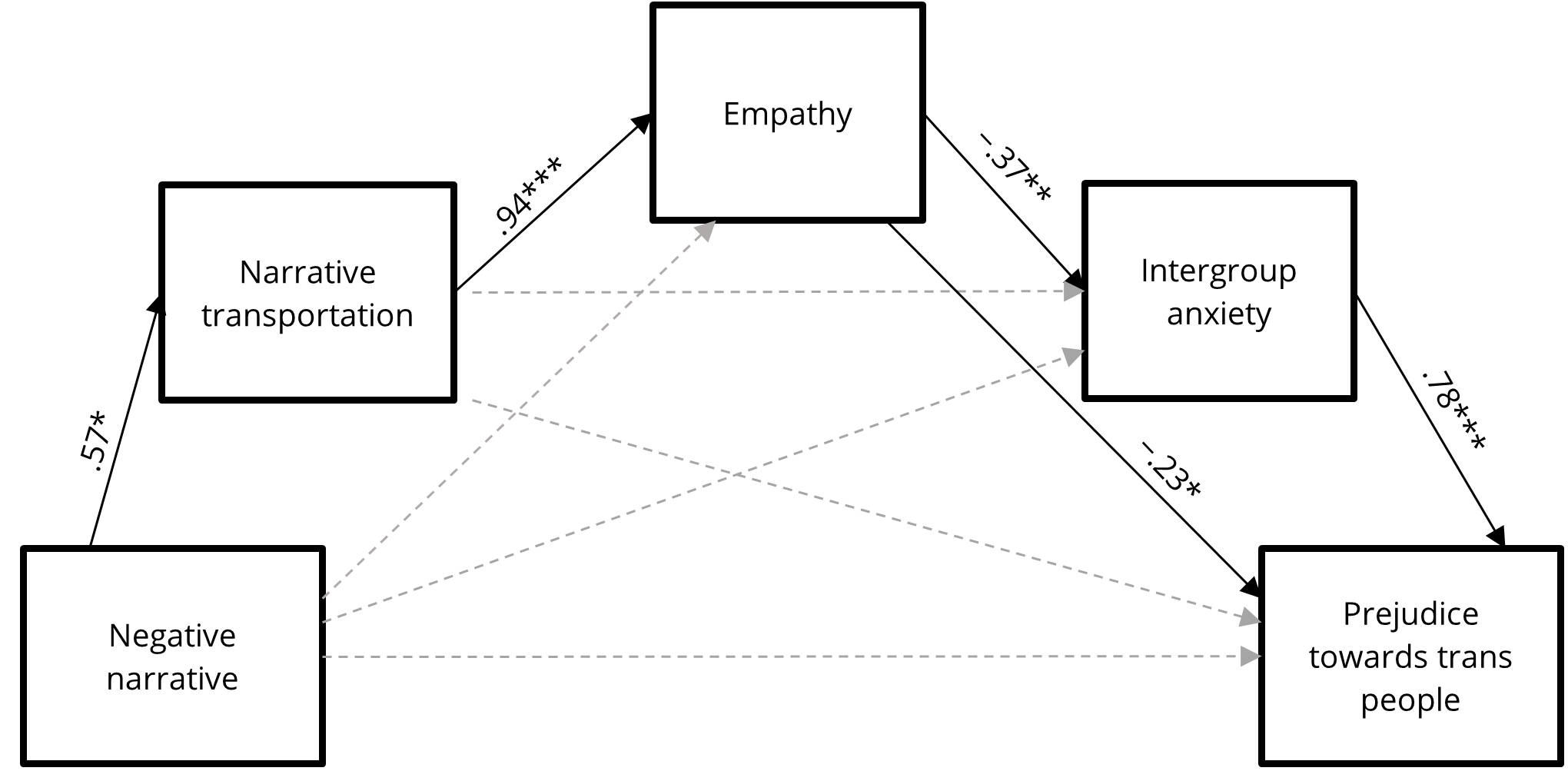

Indirect Effect of the Narrative With Mediators

The results show that there is an indirect effect on the level of prejudice through narrative transportation (H1a), empathy (H1b), and intergroup anxiety (H1c), but no direct effect (see Figure 2). Thus, H1 is confirmed. The negative narrative increases the level of narrative transportation, B = .57, p = .034, and narrative transportation increases the level of empathy towards the YouTuber, B = .94, p < .001. Similarly, empathy reduces intergroup anxiety,

B = −.37, p < .001, which is related to prejudice towards trans people, B = .78, p < .001.

Intergroup Contact and Mediated Contact as Moderators

The results show that the intergroup contact level does not moderate the effect of the type of narrative on the level of narrative transportation (H3a) or empathy (H3b). Consequently, H3 is rejected. However, intergroup contact has a direct effect on the level of narrative transportation, B = .09, p = .005, and empathy, B = .32, p < .001.

Figure 2. Model of the Indirect Effect of the Narrative With Serial Mediators (Study 1).

Note. Indirect effect through narrative transportation, empathy, and intergroup anxiety in serial,

B = .04, SE = .01, 95% CI [.01, .07].

Hence, respondents who had more frequent contact with trans people also experienced a higher level of narrative transportation and empathy when watching any type of narrative.

Similarly, mediated contact level does not moderate the effect of the type of narrative on the level of narrative transportation (H4a), B = −.01, p = .925, or empathy (H4b). Consequently, H4 is rejected. Previous mediated contact has a direct effect on the level of narrative transportation, B = .15, p = .009. Participants who more frequently watch media content with trans characters also reported a higher level of narrative transportation, regardless of the type of narrative.

Indirect Effect of the YouTuber’s Gender With Mediators

Model 6 of PROCESS was used to answer RQ2. There is an indirect effect on the level of prejudice through narrative transportation, empathy, and intergroup anxiety, but no direct effect. Trans women generate a higher level of narrative transportation, B = .18, p = .021, which in turn increases the level of empathy, B = .90, p < .001. Similarly, empathy reduces intergroup anxiety, B = −.27, p < .001, which is related to prejudice towards trans people, B = .78, p < .001.

Discussion

The results of Study 1 further our understanding of the most effective types of narratives for reducing transphobia through media, which is useful when there is no easy access to the ingroup (transgender individuals) or when this contact might produce uneasiness (Chung & Slater, 2013; Guerrero-Martín & Igartua, 2021). They also inform about the convenience of using the messages of transgender vloggers to reduce prejudice towards sexual and gender identities in mainstream audiences.

The results of this study are aligned with Bresnahan et al. (2019) and Li’s (2019) observation that the type of narrative might impact the level of prejudice. However, contrarily to both studies, this research finds that negative narratives are more effective for reducing transphobia, which is consistent with preliminary evidence suggesting the efficacy of narratives about negative experiences (Graci et al., 2018). In this study, when trans YouTubers of either gender tell a sad story about being victims of rejection or negative attitudes, transphobia is more greatly reduced.

Moreover, the results of this study confirm that the impact of the video on prejudice is not direct but mediated: a negative story told by a trans YouTuber elicits greater narrative transportation, which in turn produces greater empathy. Negative or sad personal experiences of transgender vloggers promote greater absorption/involvement with the narrative, which in turns increases empathy. Likewise, as stated by the model, greater empathy towards these YouTubers decreases intergroup anxiety, and consequently reduces prejudice (transphobia). Also, neither the degree of intergroup contact nor mediated contact with trans people moderate the effect of the type of narrative. Again, all of this is consistent with narrative persuasion theory (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006; van Laer et al., 2014) and helps to clarify the interaction between intergroup anxiety and empathy in mediated contexts (Banas et al., 2020). Consequently, using first-person narratives by YouTube trans vloggers to reduce transphobia should take into account that sad stories, containing negative experiences due to prejudice, prompt general audiences to alleviate anxiety related to interacting with trans individuals and foster empathy towards them. This, in turn, contributes to the reduction of transphobia: audiences empathize with the trans person, and from that place of understanding, they diminish their transphobic attitudes.

This study also finds that negative stories told by trans female YouTubers generate greater narrative transportation and less prejudice than those told by trans males, which contradicts research claiming that transphobia towards trans women is more predominant (Miller, 2017). A potential explanation for this might be the characteristics of the female transgender stimuli used in this research, which corresponded to young, middle class, educated transwomen, who follow traditionally western feminine cisgender heteronormative beauty cannons (Monteiro & Poulakis, 2019) and present cispassing, i.e., when a transgender person’s outward appearance or behavior leads others to assume they are cisgender, aligning with the gender they were assigned at birth. Cispassing is a manifestation of the logic of gender binarism, which characterizes cisheteronormative systems, as A. H. Johnson (2016) states. Previous studies have described how trans women in the public eye are expected to conform to models of acceptable femininity, often resembling the women surrounding the audiences, as those who align with normative female ideals, including being white, have their identities regard as legitimate (Skidmore, 2011; Zhang, 2022). Another plausible explanation could be that audiences are more accustomed to media representations of transgender women than transgender men, as the former have been observed to be more prevalent (Capuzza & Spencer, 2016). In any case, future research should explore the physical aspects of trans vloggers, their cispassing and transnormativity as mediators of the impact of narratives and prejudice reduction.

Finally, the results show that narrative transportation and empathy are greater when the participants have greater intergroup contact with transgender people in real life or watch more audio-visual content portraying transgender people. This occurs regardless of the type of narrative told by the trans vlogger.

Study 2

This study aims to replicate and build on the results of Study 1. However, in doing so, it also answers the call by scholars associated to the theories of intersectionality and queer intercultural communication and introduces a new variable to the model: xenophobia. Specifically, Study 2 explores whether the model used in Study 1 is useful for explaining prejudice reduction for all transgender individuals regardless of their nationality, which it does by trying to answer the following RQs:

RQ3: Do audience members show similar levels of narrative transportation, empathy, intergroup anxiety, and prejudice towards trans people when watching trans people’s narratives of different origin (nationality)?

RQ4: Is the indirect effect of trans people’s narratives on prejudice towards trans people moderated by the level of xenophobia?

Considering the results from Study 1, we introduce the following hypothesis:

H5: The effect of the narrative on prejudice towards trans people (H5a), narrative transportation (H5b), empathy (H5c) and intergroup anxiety (H5d) will be stronger when being shared by trans women.

Queer Intercultural Communication (QIC)

QIC is a critical, interdisciplinary field that observes identity (i.e., sexuality, gender, or nationality) in relation to social spheres (McMickens et al., 2021). It claims that sexual identities cannot be isolated from other dimensions of identity and power, such as race, class, coloniality or nation (Chávez, 2013). QIC is related to the theory of intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991), which proposes the coexistence of contradictory social experiences that are simultaneously produced and constituted by differences in race, gender sexuality, nationality, or citizen/migrant status. Building on Collins (2015), intersectionality recognizes the interconnectedness of social identities like race, class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nation, ability, and age. It posits that these identities are not fixed but shaped by intersecting power dynamics, leading to complex social inequalities marked by uneven material conditions and diverse experiences. Moreover, that these inequalities vary across historical and cultural contexts, while individuals and groups within these power structures offer unique perspectives on social disparities, influencing their academic and political pursuits. Intersectional analyses reveal inherent injustices in these power dynamics, driving efforts to challenge and transform societal norms. Specifically, Collins (2015) argues that the power dynamics of racism and sexism are intertwined. Consistently, Terriquez’s (2015) research sheds light on the intersectionality of LGBTQ+ identity and immigration, particularly examining the activism of LGBTQ+ youth from immigrant backgrounds in the United States. It underscores the profound personal hurdles faced by individuals who occupy marginalized identities within minority groups. These individuals experience compounded challenges as minorities within minorities, navigating both LGBTQ+ and immigrant communities. The study highlights how these intersecting identities can inspire heightened levels of commitment to social activism, driven by the unique experiences and needs of those who endure multiple layers of identity-based hardships. Accordingly, Eguchi (2021) indicates that relationships with transgender people are contextual, culturally specific and depend on notions of culture and power. Moreover, respect for trans individuals might be conditioned by reluctance to recognize the right of transgression for people from different backgrounds or origins (Eguchi & Calafell, 2023), which connects to the concept of xenophobia.

Xenophobia is defined as hostility towards non-natives of a given population (UNESCO, 2017). It is a rejection of what is considered foreign (Crush & Ramachandran, 2010), manifested as dislike, hate, fear or revulsion (Tafira, 2011). Xenophobia is an increasing phenomenon nowadays due to the internationalisation of the labour market, causing newcomers to be perceived as competitors for jobs, public services, social welfare, education, or healthcare (UNESCO, 2017). It is strongly related to the enunciation of cultural differences such as nationality, ethnicity, language, social territorial origins, speech patterns or accents among others (Tafira, 2011). Xenophobia leads to social ostracism of foreigners and produces exclusion, marginalization and hierarchies (Sundstrom & Kim, 2014).

On the other hand, xenophobia is related to racism, although the concepts differ in some aspects. Racism reflects nationalized narratives and focuses on the consideration of certain physical human characteristics as inferior (Wimmer, 1997) while xenophobia concerns the fear of the unknown and can be directed at objects or expressions (Garcia, 2020). The broader concept of xenophobia offers a better way to observe perceptions of a minority because it enables measurement of the outgroup animus without obliging individuals to identify themselves as openly racist toward specific people, which is impacted by social desirability bias (Baker et al., 2018).

Even though research on narrative persuasion has been interested in understanding prejudice reduction towards immigrants (e.g., Igartua et al., 2018), no study has observed xenophobia as a response related to the impact of the first-person narratives of LGBTQ+ people, let alone that of transgender YouTubers. Moreover, no research associated to narrative persuasion has considered the assumption of QIC that social experiences with LGBTQ+ people entail concurrent tensions between gender, sexuality, nationality, class and migration/status, and even prejudice that can impact attitudes.

Methods

Participants

A sample of 161 cisgender people (54% cis men) aged 18 to 58 (M = 31.73 years, SD = 10.16) living and born in Spain, and whose parents were also Spanish, participated in the online experiment. To establish the required sample size, a power analysis was conducted with G*Power (Faul et al., 2007) based on the same requirements of Study 1. Results indicated that a minimum sample size of 128 participants was required to have 80% power (α = .05) in a study with four groups. Participants were recruited via Prolific (December 2022) and were paid 3 Euros.

Materials and Procedure

A 2 (gender of the YouTuber) x 2 (nationality of the YouTuber) between-subjects online experiment was conducted. Hence, four types of video were used as stimuli: narratives sharing the negative personal experiences of eight trans YouTubers (4 male vs 4 female, and 4 Spanish vs 4 Colombian). As in the first study, these videos were similar in length (about 2 minutes), visual composition (indoor location, framing and medium shot) and protagonists (young trans, of an apparently similar age, around twenty years old, based on their appearance and the content of their speeches). A pilot study conducted with 95 adults aged 22 to 66 (M = 48.94; SD = 11.39) from a convenience sample validated the adequateness of the videos (see Appendix B).

Following QIC, which suggests that the context impacts acceptance of LGBTQ+ people, we decided to collect data in Spain to replicate Study 1 and include videos of Colombian and Spanish trans YouTubers for a variety of reasons: 1) Spain is facing the rise of populist far-right discourse against immigration, as in other European countries (Bustos Martínez et al., 2019); 2) This country has become a prime destination for migrants from lower-income countries in Europe because of its expanding economy (Ronda-Pérez et al., 2019); 3) Colombians are the third most numerous migrant group to Spain, after Romanians and Moroccans, and the first from Iberoamerican countries; 4) Queer Colombian immigrants in Spain also face the prejudices and imaginaries related to the dominant male chauvinism in their native country, together with cultural and socialization difficulties in their destination (Restrepo Pineda, 2020), and 5) a wide range of Colombian YouTubers are producing different narratives, which made it easier to select suitable stimuli for the study.

As in the main experiment, participants first completed a questionnaire, which assessed sociodemographic characteristics and the moderator variables (i.e., intergroup contact and mediated contact with trans people, and level of xenophobia). Then, they were randomly assigned to one of the experimental conditions. After watching the entire video, participants were asked to answer a set of questions measuring empathy towards the protagonist, narrative transportation, intergroup anxiety, and prejudice towards trans people. Finally, participants were debriefed.

Measures

Items for mediated contact (M = 2.86, SD = 0.83, α = .67), empathy (M = 3.76, SD = 0.85, α = .91), narrative transportation (M = 3.50, SD = 0.64, α = .77), intergroup anxiety (M = 2.00, SD = 0.65, α = .81), and transphobia (M = 1.60, SD = 0.86, α = .94) were identical to those in Study 1. Furthermore, and to assess the level of xenophobia, 16 items from the scale developed by Olonisakin and Adebayo (2021) were adapted to the purpose of the study (e.g., M = 1.78, SD = 0.60, α = .86).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Random assignment of participants to the four experimental conditions was successful. There were no statistically significant differences between the experimental groups in terms of gender, χ² (6, N = 160) = 1.935, p = .926, age, F(3, 156) = 0.646, p = .586, sexual orientation, χ² (15, N = 160) = 14.300, p = .503, or level of education,

χ² (12, N = 160) = 5.139, p = .953. Similarly, the experimental manipulation of gender and nationality was effective: 93% of participants appropriately identified the YouTuber’s gender, χ² (1, N = 160) = 118.793, p < 001 and 99.3% of participants appropriately identified the YouTuber’s nationality, χ² (1, N = 160) = 156.046, p < .001.

Finally, the correlations between the mediating variables (empathy, narrative transportation) and the dependent variables (intergroup anxiety and transphobia) were analyzed. The results justify the formulated mediation model (see Table 2).

Table 2. Correlations Between the Mediating and the Dependent Variables (Study 2).

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

1 Empathy |

— |

|

|

|

|

2 Narrative transportation |

.815*** |

— |

|

|

|

3 Intergroup anxiety |

−.574*** |

−.484*** |

— |

|

|

4 Prejudice towards trans people |

−.637*** |

−.562*** |

.664*** |

— |

|

Note. ***p < .001 |

||||

Effect of YouTuber’s Gender and Nationality on Intergroup Anxiety and Prejudice Towards Trans People

To answer RQ4 and test H5, a two-way ANOVA was conducted. The YouTuber’s gender influences the level of intergroup anxiety, F(1, 156) = 9.650, p = .002, η2 = .058, but not the level of prejudice, F(1, 156) = 2.488, p = .117, η2 = .016. Trans women (M = 1.83, SD = 0.52) are more effective than trans men (M = 2.15, SD = 0.72) at reducing intergroup anxiety. In contrast, the YouTuber’s nationality has no effect on the level of intergroup anxiety, F(1, 156) = 0.072, p = .789, η2 = .000, or the level of prejudice towards trans people, F(1, 156) = 1.714, p = .192, η2 = .011. Moreover, there is no interaction effect between the YouTuber’s gender or nationality on the level of intergroup anxiety, F(1, 156) = 3.55, p = .061, η2 = .022, or of prejudice, F(1, 156) = 0.605, p = .438, η2 = .004. Therefore, H5a is rejected, since the Youtuber’s gender does not determine the level of prejudice towards trans people. On the contrary, H5d is confirmed since trans women generate a lower level of intergroup anxiety.

To test the hypothesized model, model 83 of the PROCESS macro for SPSS was used with 10,000 bootstrapped samples.

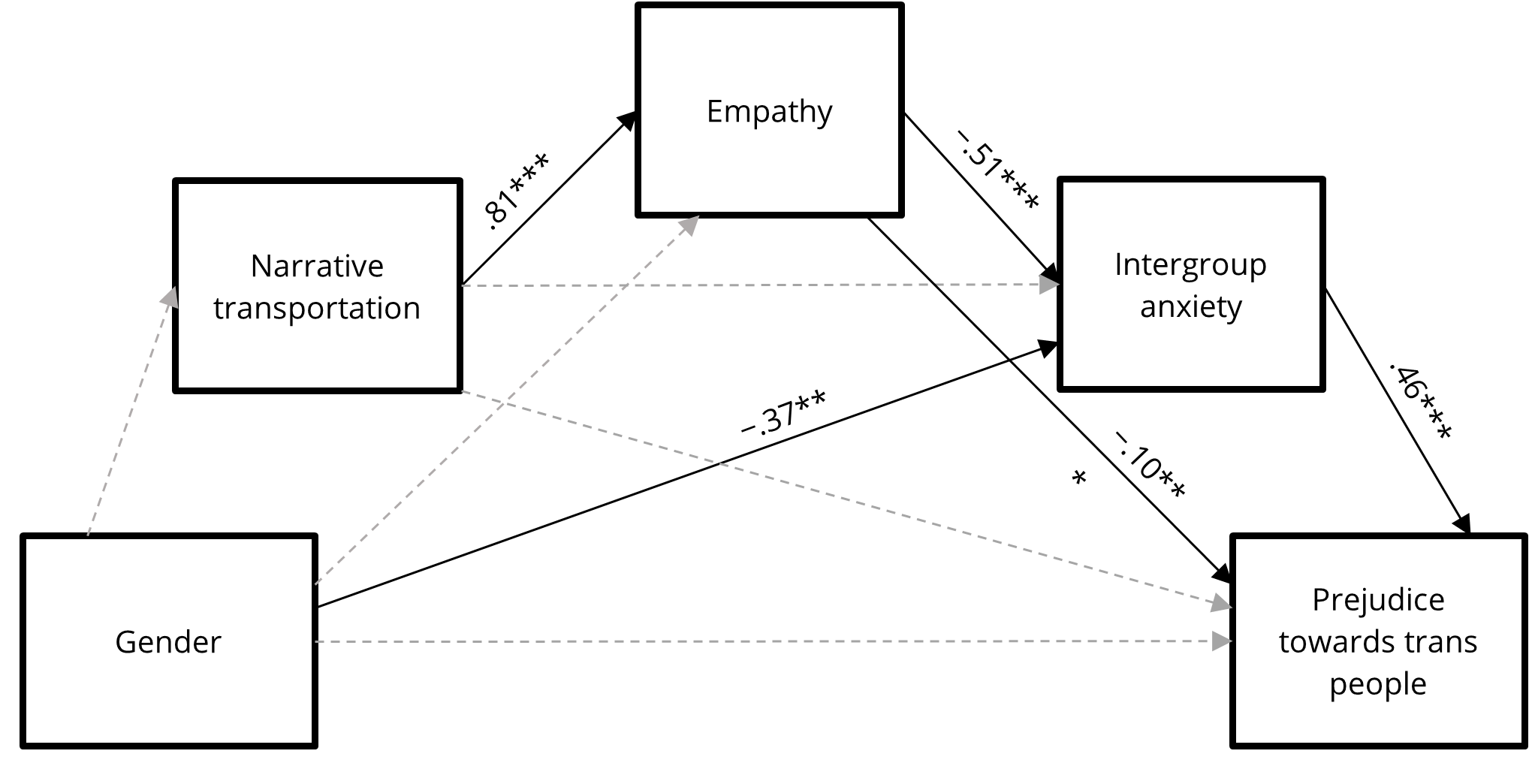

Indirect Effect of YouTuber’s Gender With Mediators

Results show that there is an indirect effect on the level of prejudice through intergroup anxiety, but no direct effect (see Figure 3). Trans women reduce the level of intergroup anxiety, B = .18, p = .021, which is related to prejudice towards trans people, B = .78, p < .001. Therefore, H5b and H5c are rejected.

Figure 3. Model of the Indirect Effect of the Youtuber’s Gender With Mediators (Study 2).

Note. Indirect effect through narrative transportation, empathy, and intergroup anxiety in serial,

B = −.17, SE = .13, 95% CI [−.44, .09].

Intergroup Contact and Mediated Contact as Moderators

Results show that the level of intergroup contact moderates the effect of the YouTubers’ gender on the level of intergroup anxiety, B = .19, p = .046. Trans women are more effective at reducing intergroup anxiety among participants with less intergroup contact in real life. Therefore, the index of moderated mediation is significant, .17, SE = .07, 95% CI [.04, .32]. Moreover, intergroup contact has a direct effect on the level of intergroup anxiety, B = −.49, p = .001. Hence, participants who had more frequent contact with trans people also presented less intergroup anxiety when watching any of the narratives.

In contrast, the level of mediated contact does not moderate the effect of the YouTubers’ gender on the level of intergroup anxiety, B = .16, p = .161. However, mediated contact has a direct effect on the level of intergroup anxiety, B = −.50, p = .006. Hence, participants who most frequently watch films and series with trans characters also presented a lower level of intergroup anxiety when watching any of the narratives.

Indirect Effect of YouTuber’s Nationality With Mediators

Results show that there is only a direct effect on the level of prejudice, but not an indirect effect, B = .14, SE = .14, 95% CI [−.13, .40]. After watching the Colombian trans youtubers, participants show a higher level of prejudice towards trans people, B = .21, p < .002.

Xenophobia as a Moderator

Results show that the level of xenophobia moderates the effect of YouTuber nationality on the level of intergroup anxiety, B = −.50, p = .001. After watching the Colombian trans YouTubers, intergroup anxiety is only higher among participants with higher levels of xenophobia. Therefore, the index of moderated mediation is significant, −.44, SE = .16, 95% CI [−.76, −.12]. Moreover, xenophobia has a direct effect on the level of intergroup anxiety, B = .25, p < .001. Hence, participants who report higher levels of xenophobia also showed higher levels of intergroup anxiety when watching any of the narratives.

Discussion

The results of Study 2 further our understanding of the mechanisms whereby transgender YouTuber’s personal stories help to reduce transphobia. They confirm Study 1 in that the gender of the trans vlogger influences the level of the receivers’ intergroup anxiety which in turn indirectly affects the level of prejudice towards trans people: Trans women are more effective at reducing intergroup anxiety and consequently transphobia than trans men.

Moreover, consistent with Study 1 and related theory, Study 2 finds that participants who have frequent contact with trans people in real life and watch more films portraying trans people present lower intergroup anxiety when watching the narratives. Again, trans women are more effective for reducing intergroup anxiety among people with less contact with trans people in real life when viewing sad narratives about transphobic episodes.

Results also show that xenophobia impacts the model of transphobia reduction as proposed and confirmed by Study 1. Specifically, xenophobia acts as a moderator of the effect of the YouTubers’ nationality on intergroup anxiety and prejudice reduction. After watching the narratives of a transgender foreigner, intergroup anxiety increases among individuals with high levels of xenophobia. This means that sad experiences narrated by trans YouTubers have the greatest impact on more xenophobic people, whose intergroup anxiety increases when watching them. Thus, xenophobia raises their level of prejudice toward trans YouTubers.

Consequently, Study 2 assesses the generalization of the model proposed in Study 1. It confirms and builds on the former’s results, particularly by characterizing the impact of narrative transportation and mediated contact on prejudice reduction and shedding further light on the relationship between empathy and intergroup anxiety. Moreover, by being stimulated by knowledge provided by QIC (Chávez, 2013; McMickens et al., 2021) and intersectionality theory (Crenshaw, 1991), Study 2 contributes to narrative persuasion theories on the understanding of the interrelated impact on attitude change of different prejudices acting simultaneously. Indeed, it confirms Eguchi (2021) and Eguchi and Calafell’s (2023) finding that relationships with transgender people are contextual, culturally specific, and dependent on notions of power and reluctance to recognize the right of transgression for people of different origins (Eguchi & Calafell, 2023). Thus, according to its results, any model explaining responses to mediated trans people should account for the weight of power, culture, race, gender, nationality and citizen status (Eguchi, 2021) in the relationship between the receivers and the mediated narrative/character, which is important in a globalized media world.

General Discussion

By applying mediated contact and narrative persuasion theories, this research proposes and confirms a model of psychological processes related to transphobia reduction by trans YouTubers’ narratives. Specifically, it claims that negative/sad experiences related to transphobic episodes promote greater narrative transportation, which fosters empathy. In turn, this empathy reduces intergroup anxiety and, consequently, transphobia. The results also show that the trans vlogger’s gender impacts the efficacy of the model: female trans YouTubers reduce transphobia to a greater extent than male ones.

By integrating QIC (Queer Intersectional Consciousness) and intersectionality into our model, we acknowledge the intricate relationships among individuals’ diverse identities, particularly emphasizing LGBTQ+ identity and nationality within power structures. Precisely, we examine how the proposed model of prejudice reduction for transgender YouTube individuals is influenced by their nationality and transphobia. We experimentally observe the extent to which being a Spanish or Colombian trans vlogger (who, in the Spanish context, is a minority and typically a product of migration) impacts prejudice reduction through their narratives on YouTube. Our research findings affirm that the nationality and transphobia of transgender vloggers interact within our psychological model, particularly affecting highly xenophobic individuals. This empirical confirmation underscores the interaction of these minority identities within the Spanish context and supports intersectionality assumptions. Specifically, high levels of xenophobia produce higher levels of intergroup anxiety which, in turn, increases transphobia. Consequently, sad first-person accounts of real transphobic episodes as told by trans vloggers of any nationality appear to be generally effective for reducing transphobia except among highly xenophobic individuals, for whom they produce the opposite effect. All of this confirms the interrelated influence of different prejudices/factors in narrative perception and the reduction of stigmatization of marginalized populations, such as transgender people and migrants.

The findings of this research can be applied to design both formal and informal initiatives for LGBTQ+ and, specifically, trans diversity literacy and awareness. Mainstream audiences are unlikely to actively seek out and spontaneously consume these narratives, given the abundance of content available on online platforms. Nevertheless, they can be undoubtedly serve as effective audiovisual learning tools freely accessible on YouTube for all users with access to this platform.

Limitations