Problematic use of social media in adolescents or excessive social gratification? The mediating role of nomophobia

Vol.18,No.4(2024)

The term problematic social media use (PSMU) refers to the interference produced by social networks in everyday life, where online participation is perceived as rewarding and continues despite negative consequences. The constant gratification (peer connection, instant notifications, scrolling, and variable rewards) has negative consequences for the well-being of adolescents, from the fear of not being connected to developing negative moods. Recent studies of uses and gratifications theory suggest that user preferences, such as the search for friendships and maintaining social relations, are related to PSMU. Based on that theory, this study analyzes the mediating role of nomophobia in the link between social use (social gratification) and problematic social media use among adolescents in Madrid (Spain). The research was conducted in 2022 with adolescents aged 14–17 (N = 820), who self-reported the use of social media, nomophobia, and problematic social media use (Adolescent Risk of Addiction to Social Networks and the Internet Questionnaire; ERA-RSI). The data were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) with partial least squares (PLS). The gratification-oriented social use offered by social networks in interactions with other people and nomophobia were explanatory variables for problematic use in adolescent participants. As predicted, nomophobia mediates the link between social use and PSMU. Social use and nomophobia were positively and significantly related, with a medium effect size. The preference for online social interaction and fear of losing this connection contribute significantly to PSMU. The results revealed the need for school-based prevention and intervention programs for digital well-being.

problematic social media use; social networks; nomophobia; uses and gratification theory; adolescents

Vanesa Pérez-Torres

Faculty of Health Sciences, Rey Juan Carlos University, Madrid, Spain

Vanesa Pérez-Torres has PhD in Psychology from the Rey Juan Carlos University (2011) and is an Associate professor in the Psychology Department (Social Psychology Area) at the Rey Juan Carlos University. Her research interests include social media, prosocial behavior, identity, and problematic use of social networks in adolescence.

Allahverdi, F. Z. (2021). The relationship between the items of the social media disorder scale and perceived social media addiction. Current Psychology, 41, 7200–7207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01314-x

Arpaci, I. (2022). Gender differences in the relationship between problematic internet use and nomophobia. Current Psychology, 41, 6558–6567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01160-x

Braña-Sánchez, A., & Moral-Jiménez, M. (2022). Nomofobia y FOMO en el uso del smartphone en jóvenes: El rol de la ansiedad por estar conectado [Nomophobia and FoMO in the use of smartphones in young people: the role of anxiety to be connected]. Health and Addictions, 23(1), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.21134/haaj.v23i1.707

Brand, M., Potenza, M., & Stark, R. (2022). Theoretical models of types of problematic usage of the internet: When theorists meet therapists. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 45, Article 101119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2022.101119

Buckingham, D. (2020). Epilogue: Rethinking digital literacy: Media education in the age of digital capitalism. Digital Education Review, 37, 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1344/der.2020.37.230-239

Bucknell, C., & Kottasz, R. (2020). Uses and gratifications sought by pre-adolescent and adolescent TikTok consumers. Young Consumers, 21(4), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-07-2020-1186

Cataldo, I., Billieux, J., Esposito, G., & Corazza, O. (2022). Assessing problematic use of social media: Where do we stand and what can be improved? Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 45, Article 101145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2022.101145

Chen, H. T., & Kim, Y. (2013). Problematic use of social network sites: The interactive relationship between gratifications sought and privacy concerns. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(11), 806–812. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0608

Eyal, N., & Hoover, R. (2014). Hooked: How to build habit-forming products. Penguin.

Fidan, M., Debbağ, M., & Fidan, B. (2021). Adolescents like Instagram! From secret dangers to an educational model by its use motives and features: An analysis of their mind maps. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(4), 501–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239520985176

Galhardo, A., Loureiro, D., Raimundo, E., Massano-Cardoso, I., & Cunha, M. (2020). Assessing nomophobia: Validation study of the European Portuguese version of the nomophobia questionnaire. Community Mental Health Journal, 56, 1521–1530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00600-z

Gamboa-Melgar, G., Peña-Fuertes, Y., & Manzanares-Medina, E. (2022). Evidencias psicométricas de la escala de riesgo de adicción-adolescente en redes sociales e internet en estudiantes peruanos [Psychometric evidence of the scale of risk of addiction to social networks and internet for adolescents in peruvian]. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 9(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.21134/rpcna.2022.09.1.7

Geary, C., March, E., & Grieve, R. (2021). Insta-identity: Dark personality traits as predictors of authentic self-presentation on Instagram. Telematics and Informatics, 63, Article 101669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101669

Gezgin, D., Hamutoglu, N., Sezen-Gultekin, G., & Ayas, T. (2018). The relationship between nomophobia and loneliness among Turkish adolescents. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 4(2), 358-374. https://doi.org/10.21890/ijres.409265

González-Nuevo, C., Cuesta, M., Postigo, A., Menéndez-Aller, A., & Muñiz, J. (2021). Problematic social network use: Structure and assessment. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21, 2122–2137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00711-y

Hair, J, Risher, J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Heng S., Gao Q., & Wang M. (2023) The effect of loneliness on nomophobia: A moderated mediation model. Behavioral Sciences, 13(7), Article 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070595

Henseler, J., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 405–431. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-09-2014-0304

Hussain, Z., Kircaburun, K., Savcý, M., & Griffiths, M. (2023). The role of aggression in the association of cyberbullying victimization with cyberbullying perpetration and problematic social media use among adolescents. Journal of Concurrent Disorders. https://doi.org/10.54127/AOJW5819

Kamolthip, R., Chirawat, P., Ghavifekr, S., Gan, W., Tung, S., Nurmala, I., Nadhiroh, S. R., Pramukti, I., & Lin, C. (2022). Problematic internet use (PIU) in youth: A brief literature review of selected topics. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 46(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2022.101150

Kara, M., Baytemir, K., & Inceman-Kara, F. (2021). Duration of daily smartphone usage as an antecedent of nomophobia: Exploring multiple mediation of loneliness and anxiety. Behaviour & Information Technology, 40(1), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1673485

Katz, E., Blumler, J., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). Utilization of mass communication by the individual. In J. G. Blumler & E. Katz (Eds.), The uses of mass communications: Current perspectives on gratifications research (pp. 19–32). Sage Publications.

Kaviani, F., Robards, B., Young, K., & Koppel, S. (2020). Nomophobia: Is the fear of being without a smartphone associated with problematic use? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, Article 6024. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176024

Kilford, E., Garrett, E., & Blakemore, S. (2016). The development of social cognition in adolescence: An integrated perspective. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 106–120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.016

King, A., Valença, A., Silva, A., Carvalho, M., & Nardi, A. (2013). Nomophobia: Dependency on virtual environments or social phobia? Computer in Human Behavior, 29(1), 140–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.025

Kircaburun, K., Alhabash, S., Tosuntaş, Ş., & Griffiths, M. (2020). Uses and gratifications of problematic social media use among university students: A simultaneous examination of the big five of personality traits, social media platforms and social media use motives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18, 525–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9940-6.

León-Mejía, A., Calvete, E., Patino-Alonso, C., Machimbarrena, J. M., & González-Cabrera, J. (2021). Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q): Factorial structure and cut-off points for the Spanish version. Adicciones, 33(2). https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.1316

Lin, Y., Fu, S., & Zhou, X. (2023). Unmasking the bright–dark duality of social media use on psychological well-being: A large-scale longitudinal study. Internet Research, 33(6), 2308–2355. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-05-2022-0320

Maftei, A., & Pătrăușanu, A. (2023). Digital reflections: Narcissism, stress, social media addiction, and nomophobia. The Journal of Psychology, 158(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2023.2256453

Marciano, L., Camerini, A. L., & Morese, R. (2021). The developing brain in the digital era: A scoping review of structural and functional correlates of screen time in adolescence. Frontier in Psychology, 12, Article 671817. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.671817

Martínez, M., & Fierro, E. (2018). Aplicación de la técnica PLS-SEM en la gestión del conocimiento: un enfoque técnico práctico [Application of PLS-SEM in knowledge management: a practical technical approach]. Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo, 8(16), 1–35. https://doi.org/0.23913/ride.v8i16.336

Memon, M., Cheah, J., Ting, R., & Chuah, F. (2018). Mediation analysis issues and recommendations. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 2(1),1–9. https://doi.org/10.47263/JASEM.2(1)01

Mittmann, G., Woodcock, K., Dörfler, S., Krammer, I., Pollak, I., & Schrank, B. (2021). “TikTok is my life and Snapchat is my ventricle”: A mixed-methods study on the role of online communication tools for friendships in early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 42(2), 172–203. https://doi:10.1177/02724316211020368

Moretta, T., Buodo, G., Demetrovics, Z., & Potenza, M. (2022). Tracing 20 years of research on problematic use of the internet and social media: Theoretical models, assessment tools, and an agenda for future work. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 112, Article 152286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152286

Phua, J., Jin, S., & Kim, J. (2017) Uses and gratifications of social networking sites for bridging and bonding social capital: A comparison of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.041.

Peris, M., Maganto, C., & Garaigordobil, M. (2018). Escala de riesgo de adicción-adolescente a las redes sociales e internet: fiabilidad y validez (ERA-RSI) [Scale of risk of addiction to social networks and Internet for adolescents: reliability and validity (ERA-RSI]. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 5(2), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.21134/rpcna.2018.05.2.4

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J. M. (2022). SmartPLS 4. Oststeinbek: SmartPLS GmbH. http://www.smartpls.com.

Rodríguez-García, A. M., Moreno-Guerrero, A. J., & López, J. (2020). Nomophobia: An individual’s growing fear of being without a smartphone—a systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, Article 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020580

Sharma, M., Mathur, D. M., & Jeenger, J. (2019). Nomophobia and its relationship with depression, anxiety, and quality of life in adolescents. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 28(2), 231–236. https://doi.org/10.4103/ipj.ipj_60_18

Soper, D. S. (2022). A-priori sample size calculator for multiple regression. https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc

Stavropoulos, V., Motti-Stefanidi, F., & Griffiths, M. D. (2021). Risks and opportunities for youth in the digital era. European Psychologist, 27(2). https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000451

Tanta, I., Mihovilović, M., & Sablić, Z. (2014). Uses and gratification theory: Why adolescents use Facebook? Izvorni Znanstveni Rad, 20(2), 85–110. https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/197512

Throuvala, M., Griffiths, M., Rennoldson, M. & Kuss, D. (2019). Motivational processes and dysfunctional mechanisms of social media use among adolescents: A qualitative focus group study. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.012

Tomczyk, L., & Selmanagic, E. (2022). Nomophobia and phubbing: Wellbeing and new media education in the family among adolescents in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Children and Youth Services Review, 137, Article 106489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106489

Uhls, Y., Ellison, N., & Subrahmanyam, K. (2017). Benefits and costs of social media in adolescence. Pediatrics, 140 (Supplement 2), S67–S70. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1758E

Varona, M. N., Muela, A., & Machimbarrena, J. M. (2022). Problematic use or addiction? A scoping review on conceptual and operational definitions of negative social networking sites use in adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 134, Article 107400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107400

Wegmann, E., & Brand, M. (2019). A narrative overview about psychosocial characteristics as risk factors of a problematic social networks use. Current Addiction Report, 6, 402–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00286-8

Yildirim, C., & Correia, A. (2015). Exploring the dimensions of nomophobia: Development and validation of a self-reported questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.059

Authors’ Contribution

Vanesa Pérez-Torres: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

July 12, 2023

Revisions received:

January 10, 2024

March 16, 2024

May 31, 2024

Accepted for publication:

June 12, 2024

Editor in charge:

Maèva Flayelle

Introduction

Online communication tools, including instant messaging social media and social networks, have taken root in most adolescent activities in the Western world (Wegmann & Brand, 2019). The emergence of new platforms and the implementation of advanced features have led to an increase in research into the impact of social media platforms on the adolescent population (Cataldo et al., 2022). These tools offer adolescents the opportunity to meet social interaction needs by communicating, expressing, and identifying with their peer groups (Tanta et al., 2014; Wegmann & Brand, 2019), although they can also expose them to risks, including nomophobia (the fear of being away or disconnected from one’s smartphone or technological device) or other problematic use that has negative consequences on their well-being (Brand et al., 2022; Uhls et al., 2017). Moreover, adolescence is also characterized by a high risk of exposure to cyber threats, which can lead to problematic situations related to digital devices (Brand et al., 2022; Wegmann & Brand, 2019).

The social and psychological motivations that cause adolescents to use social networks are usually explained by the classic uses and gratifications theory (Katz et al., 1974), which assumes that people choose a means of communication, an application, or social media because it allows them to satisfy certain needs (entertainment, fun, affective needs, social interaction). This theory offers a framework for social media analysis in which the audience plays an active role and users themselves are the creators of content (Bucknell & Kottasz, 2020). It is currently being applied to explain why users actively consume and create content on social networks to meet their individual needs (Geary et al., 2021).

The uses and gratifications theory (Katz et al., 1974) argues that the benefits derived from social networks vary significantly. The most studied motivations related to the use of social networks are social connection, self-expression, social recognition, searching for information, and entertainment (Bucknell & Kottasz, 2020; Mittman et al., 2021; Throuvala et al., 2019). According to a study by Mittman et al. (2021) using a mixed methodology (qualitative and quantitative), participating adolescents did not differentiate between the communication they established online and offline, except in cases of information related to their privacy. Interactions on social networks, such as TikTok, offer young people a space to build and maintain friendships, while others, like YouTube, provide entertainment. Thus, the primary reason given for using online social networks and instant messaging like WhatsApp in the study was to connect with peers, and in some cases, not having a phone could generate social exclusion problems (Mittman et al., 2021). Regarding the social network Instagram, Fidan et al. (2021) asserted that this platform was primarily used for communication with peers and entertainment. In addition, participants did consider possible negative consequences for their well-being, such as changes in mood or a risk of addiction to social media (Fidan et al., 2021).

Some studies that have employed the uses and gratifications theory explanatory framework have found that the reasons for engaging with social networks, such as searching for friends, entertainment, and maintaining social relationships, are related to their problematic use (Chen & Kim 2013; Kircaburun et al., 2020). This has been addressed in recent decades from different paradigms and applying a variety of definitions, including pathological, compulsive, and negative use, among others (for a review, see Varona et al., 2022). Currently, the phenomenon is studied via two main approaches: 1) identifying it as a risk for addiction, focusing on behavioral symptoms that may affect vulnerable users (Allahverdi, 2021; Brand et al., 2022); and 2) considering it problematic and highlighting the interference produced by the use of social networks in everyday life (González-Nuevo et al., 2021; Varona et al., 2022), where online participation is perceived as rewarding and continues despite negative consequences (Moretta et al., 2022). This study focuses on problematic social media use (PSMU). As—in line with scientific research on the subject—it is based on the argument that these behaviors should not be pathologized, the term “problematic use” is maintained to distinguish it from a clinical condition (the risk of addiction to social networks has not yet been recognized as a disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (González-Nuevo et al., 2021; Hussain et al., 2023; Varona et al., 2022).

Stavropoulos et al. (2021) proposed a theoretical framework to explain the problematic use of online social networks based on the type of interaction that the individual has with these media: a) a high level of virtual presence, that is, experiencing digital environments as if it were the real world; b) high consumption of attention and perception that involves the use of these media, especially the feeling of “flow” (immersive pleasure); and c) the way in which people present themselves on social networks (self-presentation), which in some cases differs from their true selves. As these interactions become more salient, the risk of problematic use increases (Stavropoulos et al., 2021). Another explanation for problematic usage is related to the features of social network platforms. The Hook Model proposed by Eyal and Hoover (2014), for instance, provides a tool to understand a user’s hyperconnectivity and the consequent risk of problematic use with these media. The model’s name is based on the ability to “hook” people into using a product (e.g., smartphone or digital device), with this use eventually becoming a habit. This is done in a four-step looped process: 1) the user needs to be triggered to perform an action, usually through an external cue (e.g., a sound or message to complete their profile); 2) to receive a reward, the user must perform a small amount of work (e.g., publish a profile photo to receive a “like”); 3) rewards, which can be immediate or random, increase satisfaction with product usage; and 4) the user is provided with some form of investment in the system that increases the likelihood that they will return (e.g., data, money, time). In the end, the user will want to return if they invest time or effort in the system and establish a connection.

Figure 1. Hook Model Cycle (Adapted From Eyal & Hoover, 2014).

Applied to social networks, this model consists of four phases: 1) automatic notifications appear; 2) the platform or application proposes that the user performs some action (for example, complete a profile); 3) in the variable reward phase, users are rewarded with new content to comment, share, “like”, etc.; 4) these actions are considered an investment in the platform to which the user feels committed, making it more difficult to leave (for example, “I have invested a lot of time in having a network of friends or followers”). In addition, these actions feed the content of other users and are used, in turn, to offer more news or seemingly endless posts. Therefore, the characteristics of social media—the predomination of interactivity, the possibility of being on different networks at once, instant notification, displacement by constant or almost endless content (scrolling), and variable rewards—provide constant gratification to users, especially in the adolescent population (Moretta et al., 2020; Phua et al., 2017; Rodríguez-García et al., 2020), increasing the risk of problematic use.

Problematic social media use can result in behaviors like mood modification, intra- and interpersonal conflicts, withdrawal from offline life, considering online social media a central activity in a person’s life (prominence), extreme concern about not having access to these media, and/or excessive and uncontrolled social use (Moretta et al., 2022). Additionally, for people suffering from problematic use, a lack of access to social media can produce nomophobia. Nomophobia is the discomfort or fear caused by the non-availability of a mobile phone and not having access to the services offered by this technology, such as not being able to communicate, losing connection, or an inability to access information (King et al., 2013; Yildirim & Correia, 2015). Nomophobia manifests itself in constantly thinking about using a phone to browse online resources, checking the device impulsively, being distracted by the phone while engaging in offline activities, and holding the device in one’s hands in inappropriate situations, like during class (Tomczyk & Selmanagic, 2022). There is a disparity in the prevalence of nomophobia, with percentages ranging from between 6 and 73%, with the highest percentage among young people (León-Mejía et al., 2021).

Nomophobia has been associated with negative consequences for adolescents and young people, especially in well-being (anxiety, loneliness, stress). For example, Gezgin et al. (2018) found a positive relationship between nomophobia and loneliness. According to that study, young people who lost access to their smartphones felt lonely because they were afraid of not being able to socialize and communicate with others (Gezgin et al., 2018), and their attempts to escape loneliness using their smartphones led to the development of nomophobia in some cases. Recently, Heng et al. (2023) analyzed the relationship between mobile phone use and nomophobia, highlighting the negative consequences like anxiety and solitude that the inappropriate use of these devices was found to have on the well-being of adolescents. In particular, their results showed that young people who report feeling more alone and use mobile phones as an object that offers security in communication tend to have a higher level of nomophobia (Heng et al., 2023). Anxiety is also a significant variable in explaining nomophobia. Young people who have a higher level of anxiety and also have a more frequent or problematic use of smartphones usually also have higher levels of nomophobia (Braña-Sánchez & Moral-Jiménez, 2022). In this context, adolescents may experience irrational fear associated with leaving home without their mobile device, the risk of losing it, battery exhaustion, or a loss of internet connectivity, producing high levels of anxiety. The fear of not being able to have access to a smartphone can generate anxiety or even depression (Sharma et al., 2019). Moreover, in situations with a problematic use of mobile phones, nomophobia can increase the individual’s stress level. Thus, nomophobia plays a mediating role between personality variables (e.g., neuroticism) and perceived stress (Maftei & Pătrăușanu, 2023).

Nomophobia is also related to a preference for constant online social interaction (use oriented toward social gratification) and is usually associated with the problematic use of social networks (Arpaci, 2022; Galhardo et al., 2020; Rodríguez-García et al., 2020). The social use of smartphones offers users a significant number of gratifications, such as sensory incentives (notifications, images, videos) and unlimited content, all of which can make disconnection difficult (Stavropoulos et al., 2021). In addition, people who are highly engaged in social media—spending more time on social media, excessively checking their mobile phones—may be more concerned about missing out on something (FOMO) and be more susceptible to having PSMU (Arpaci, 2022; Galhardo et al., 2020; Rodríguez-García et al., 2020). Therefore, nomophobia is now considered an antecedent variable or predictor of problematic social media use, in which fear (not being able to communicate or access these media) increases negative consequences for users (Kaviani et al., 2020). Nevertheless, other researchers have argued that the relationship between the use of social media and nomophobia is bidirectional. In a recent study, for example, Lin et al. (2023) analyzed the bidirectional effect between social media use and nomophobia in a group of adolescents and young people. The results found that “social media use contributes to cultivating addictive symptoms, thereby accumulating loneliness, depression, and perceived stress. In turn, nomophobia accumulates over time and triggers users to spend more time on social media” (Lin et al., 2023, p. 2334). Moreover, nomophobia had a mediating role between the use of social media and well-being variables such as depression, perceived stress, and loneliness (Lin et al., 2023).

PSMU and nomophobia both interfere with the lives of social media users, who continue to engage in their media habits despite the negative repercussions (Moretta et al., 2022). The consequences of nomophobia are similar to those produced by problematic social media use, including excessive use and negative effects on the user’s mood like feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and unhappiness, especially among young people (Galhardo et al., 2020). Therefore, nomophobia may be a mediating variable between uses oriented toward social gratification and their negative consequences.

The Present Study

Most scientific literature on the problematic use of online social media focuses on the negative consequences that this behavior can generate (Arpaci, 2022; Galhardo et al., 2020; Hussain et al., 2023). However, it is still necessary to further explore the particular factors that promote the emergence and maintenance of problematic use (Hussain et al., 2023). An approach to understanding this phenomenon based on the uses and gratifications theory that considers social use among adolescents and the characteristics of social networks can help explain the problematic use of social media (Moretta et al., 2020). Moreover, considering the mediating variables can better explain the effects of social media use (Lin et al., 2023). To that end, this study explores the relationship between social use (social gratification) and problematic social media use (PSMU) in a group of adolescents, mediated by nomophobia, using the uses and gratifications theory (Figure 1).

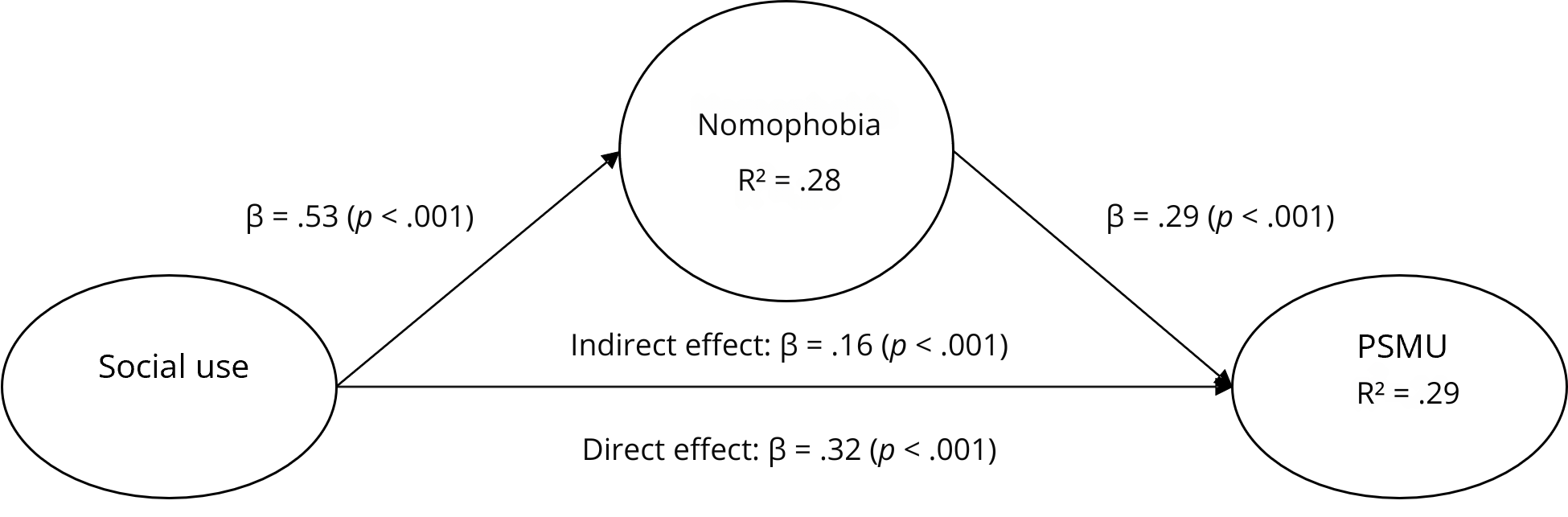

Figure 2. Conceptual Model.

Methods

An exploratory and cross-sectional study was conducted.

Procedure and Sampling

The schools were contacted through their educational guidance services. Each school administration authorized the study, and the information was communicated to the parents or guardians of the students. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Scientific Research from Rey Juan Carlos University (reference number: 3007201911619). The participating students read and approved the corresponding informed consents. No personal data were collected from the students, and all the questionnaires were anonymous. Data were collected between January and July 2022.

To determine the minimum sample size needed to perform a multivariant analysis (structural equation modeling, or SEM) the SEM calculator designed by Soper (2022) was used, assuming a moderate effect size, a statistical power of 95% and a statistical significance level of 5%. The minimum sample size was 589. Data was collected from eight schools from the third and fourth years of middle school, the first and second years of high school and the equivalent vocational training classes. The participant sample was composed of 820 adolescents in Madrid, Spain. The participants’ average age was 14.8 years old (SD = 1.40, range = 14–17), with 48.3% boys, 50% girls, and 1.7% non-binary.

Measures

A questionnaire was administered in different schools with the following measures.

Social Use

To assess the social use of social media, a subscale (8 items) of the Adolescent Risk of Addiction to Social Networks and the Internet Questionnaire (ERA-RSI; Peris et al., 2018) was used. The subscale has 8 items with a 1–4 response scale (1, never or almost never to 4, often or always). The questions are related to the social gratification use and motivation category (social interaction, need for communication, maintaining social bonds with friends) proposed by Bucknell and Kottasz (2020). The internal consistency of the scale was .90 Cronbach’s alpha (Peris et al., 2018). The psychometric (internal consistency) evidence of this scale used in other studies is adequate: ω = .74 to .83 (Gamboa-Melgar et al., 2022). Sample items: I consult the profiles of my friends and We comment on the pictures between friends.

Nomophobia

A Nomophobia subscale (6 items) of the Adolescent Risk of Addiction to Social Networks and the Internet Questionnaire (ERA-RSI; Peris et al., 2018) was used. This subscale measures aspects related to anxiety and control while using electronic devices. Sample items: If they do not immediately respond to my messages, I feel anxious and I would be furious if they took my smartphone.

Problematic Use

Problematic use was measured through a Symptom-addiction subscale (9 items) of the Adolescent Risk of Addiction to Social Networks and the Internet Questionnaire (ERA-RSI; Peris et al., 2018). These items evaluate the main aspects included in most problematic use scales, such as mood modification, excessive or compulsive use, interference in daily life activities, negative consequences on well-being, among others (for a review of the measures, see Cataldo et al., 2022). Sample items: Right now I would feel angry if I had to do without social networks and I have lost hours of sleep from connecting to social networks.

Data Analysis

To evaluate the relationships between the variables, the data were analyzed using structural equation modeling, or SEM) with partial least squares (PLS) using the Smart PLS4 software (Ringle et al., 2022). This method was selected considering that the purpose of this study is to analyze relationships between predictor (social use) and outcome (PSMU) variables, as well as to calculate the mediation effect of nomophobia. These types of PLS models (PLS-SEM), based on the analysis of variance (which maximizes the explained variance of model-dependent variables and estimates their parameters), are used in exploratory studies in which the sample does not follow a normal distribution (Martínez & Fierro, 2018). The procedure requires analyzing the measurement model, based on the reliability and validity of the measurements, and contrasting the relationships between the variables from the structural model. This analysis also makes it possible to evaluate the fit of the model through fit indices such as the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The mediation analysis followed a segmentation approach with the relationships between predictor and outcome variables, in addition to the calculation of the mediation effect (Memon et al., 2018). PLS-SEM was specified including endogenous constructs and the structural relationship to reflect the research hypotheses.

Results

Measurement Model

The hypothetical model had three latent variables with a reflective measurement model. Before testing the proposed hypotheses with the PLS-SEM model, it was necessary to confirm that it was reliable, valid, and had predictive power. Therefore, the measurement model was first evaluated by looking at the outer loadings of the indicators, the internal reliability, and the convergent validity, and the discriminant validity of the reflective constructs (Hair et al., 2019). The indicators were maintained with loads superior to 0.7, which explains at least 50% of the construct (Hair et al., 2019).

The reliability of the construct was evaluated through Cronbach’s alpha, Dijkstra-Henseler’s rho (ρa), and composite reliability (ρc). Additionally, the average variance extracted (AVE) was used to assess the convergent validity (see Table 1). All scales have adequate reliability indices and the average variance extracted exceeds the minimum required in the literature (Hair et al., 2019).

Table 1. Measure Reliability.

|

Cronbach’s alpha |

ρa |

ρc |

AVE |

|

|

Social use |

.70 |

.70 |

.80 |

.536 |

|

Nomophobia |

.73 |

.74 |

.79 |

.547 |

|

PSMU |

.70 |

.71 |

.76 |

.545 |

|

Note. PSMU = problematic social media use; AVE = average variance extracted. |

||||

Discriminant validity was evaluated based on the Fornell-Larcker criterion, cross-loadings between indicators and latent variables, as well as the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT; Hair et al., 2019). In the case of the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square roots of the averance variance extracted are higher than the correlation between the constructs, which indicates that the measurement model is adequate (Table 2). The HTMT values obtained among the latent variables with the reflective measurement model were lower than .85, which represented discriminant validity (PSMU ↔ nomophobia = .732; social use ↔ nomophobia = .732; social use ↔ PSMU = .715).

Table 2. Discriminant Validity (Fornell-Larcker Criterion).

|

Social use |

Nomophobia |

PSMU |

|

|

Social use |

.674 |

||

|

Nomophobia |

.530 |

.660 |

|

|

PSMU |

.475 |

.463 |

.668 |

Structural Model

To evaluate the structural model (the relationships between the proposed variables), the collinearity, the path or standardized coefficients, the determination coefficients (R2), effect size (f 2) and the general model were evaluated from the SRMR residual mean square root (Henseler et al., 2016). The significance of the path coefficients was calculated through bootstrapping analyses based on 5,000 subsamples and two-tailed tests (Hair et al., 2019). The data are shown in Table 3.

All values of the variance inflation factor (VIF) are below 3, which indicates the absence of multicollinearity: nomophobia → PSMU = 1.29; PSMU → nomophobia = 1.00; social use → PSMU = 1.39.

Table 3. Direct Effect of the Mediation Analysis.

|

Path |

β |

t |

p |

LLCI |

ULCI |

f 2 |

|

Social use → nomophobia |

.530 |

16.64 |

< .001 |

.45 |

.58 |

.39 |

|

Nomophobia → PSMU |

.293 |

6.85 |

< .001 |

.20 |

.37 |

.09 |

|

Social use → PSMU |

.320 |

15.38 |

< .001 |

.24 |

.39 |

.10 |

|

Note. Bootstrap samples = 5,000. LL = low limit; UL = upper limit; CI = 95% confidence interval; PSMU = problematic social media use. |

||||||

The effect size of social use on nomophobia was medium, greater than .30; the effect size of nomophobia on PSMU and social use on PSMU were small, greater than .02. The relationship between social use and nomophobia is positive and significant (β = .530, p < .001), as is the relationship between social use and problematic use (β = .320, p < .001). Nomophobia is also related to problematic use (β = .293, < .001), as stipulated in the theoretical model. The mediating effect of nomophobia on PSMU was analyzed by testing direct and indirect effects, and both effects were significant. The indirect (mediating) effect of nomophobia between the relation of the variables social use and PSMU is .16 (β = .155, p < .001), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Indirect Effect of the Mediation Analysis.

|

Path |

β |

t |

p |

LLCI |

ULCI |

|

Social use → nomophobia → PSMU |

.155 |

6.37 |

< .001 |

.11 |

.20 |

|

Note. PSMU = problematic social media use; LL = low limit; UL = upper limit. |

|||||

The value of R2 between nomophobia and PSMU indicates that the variance of problematic social media use is explained 28% by nomophobia. The value of R2 between social use and PSMU indicates that the variance of problematic social media use is explained 29% by social use. The overall fit of the model was determined by the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), which in this model is .07 (SRMR = .07). The model adjustment is considered appropriate when the values are less than .08 (Hair et al., 2019).

Figure 3. Structural Model Results.

Discussion

The uses and gratifications theory (Katz et al., 1974) explains the social and psychological motivations that lead adolescents to use online social media. Users of these media play an active role in the creation of content (Bucknell & Kottasz, 2020), and younger people focus their use mainly on entertainment and social connections like communicating with peers, searching for friendships, and maintaining social relations (Fidan et al., 2021; Geary et al., 2021). Some studies have linked the social gratification produced by social networks to problematic use (Chen & Kim, 2013; Kircaburun et al., 2020).

In this study, the problematic use of social networks was analyzed as a behavior that has negative consequences on the well-being of users (e.g., mood modification), in which participation in social media is perceived as rewarding and continues despite negative effects (González-Nuevo et al., 2021; Moretta et al., 2022; Varona et al., 2022). User interactions with social networks (virtual presence, high consumption of attention and perception, sensation of flow) and the characteristics of these media (the ability to be on different networks simultaneously, instant notifications, endless content scrolling, variable reward) are related to problematic use (Eyal & Hoover, 2014; Moretta et al., 2020; Phua et al., 2017; Rodríguez-García et al., 2020; Stavropoulos et al., 2021).

In the results of this study, the gratification-oriented social use offered by social media in interactions with other people (β = .320, p < .001) and nomophobia (β = .293, p < .001) are explanatory variables of problematic use in adolescent participants. Thus, the preference for online social interaction and the fear of losing this connection contribute significantly to problematic social media use (Arpaci, 2022; Galhardo et al., 2020; Rodríguez-García et al., 2020). These findings are consistent with previous studies that assert that social use (e.g., socializing by using social media, meeting people) and nomophobia significantly positively influence PSMU (Arpaci, 2022; Kircaburun et al., 2020). Nevertheless, in future studies, other variables such as personality (e.g., extraversion, emotional stability, regulation), participation in online activities (e.g., online gambling), and social anxiety could be added to the model to provide a more complete explanation of PSMU and nomophobia (Kara et al., 2021; Maftei & Pătrăușanu, 2023; Rodríguez-García et al., 2020). According to the mediation model, there was a significant relationship between the social use of social networks and problematic use through nomophobia (β = .16, p < .001). This indirect effect was analyzed using bootstrapping procedures, which are considered a robust method to detect mediation relationships between variables (Memon et al., 2018), although the result of the effect size in this study was low. One of the main reasons for adolescents’ use of social media is social use, which offers nearly constant gratification of social interactions and maintains social bonds. This social use, together with the gratification of social network design (e.g., interactivity), contributes to excessive usage that can foster the development of nomophobia and have negative effects on the well-being of adolescents. Significantly, the fear of not being connected to social networks can increase the negative consequences of excessive or inappropriate social media use among adolescents (Galhardo et al., 2020; Kaviani et al., 2020).

The positive and significant relationship between social use and nomophobia (β = .53, p < .001) indicates that the constant gratification obtained using social networks produces negative consequences on the well-being of adolescents, such as the fear of not being connected or a negative mood (Galhardo et al., 2020; Kaviani et al., 2020). Therefore, social motivations aimed at maintaining interpersonal relationships, friendships, or links with peers in social networks (perceived as rewarding) play an important role in continuing unhealthy or problematic behaviors in the use of these media (González-Nuevo et al., 2021; Moretta et al., 2022; Varona et al., 2022). Research related to nomophobia shows that other factors, such as the lack of alternatives to smartphone use—for example offline leisure activities like hobbies—can increase the intensity of the negative consequences of nomophobia (Kara et al., 2021). Therefore, offline activities that offer social interaction can be a protective factor against PSMU. Future studies should explore how mobile phones can be used adaptively and functionally (Kamolthip et al., 2022), as this study has only focused on problematic use. This approach would provide a more complete understanding of the effects of nomophobia in younger users.

Adolescents have been found to need social connections for their psychological well-being, and social media provide an environment for expanding and satisfying such social needs (Tanta et al., 2014), although the teenagers do not perceive (or have difficulty perceiving) the negative effects of these media. One explanation for the difficulty in perceiving the negative effects of social media is related to the cognitive development of adolescents, especially their executive functions. Executive functions (cognitive processes that enable the control and coordination of thoughts and behavior) continue to develop during adolescence. Since cognitive control (the ability to actively guide behavior) and heightened reward sensitivity in adolescence can influence the regulation of negative or risky behaviors (Kilford et al., 2016), this may explain the permanence of problematic use. Future studies should explore the relationship between cognitive control, reward sensitivity, and problematic social media use in the adolescent population (Marciano et al., 2021).

This study contributes to the current state of the art by expanding upon uses and gratifications literature to explain social media use, especially social use, in adolescents. Moreover, it examines the relationship between social use, nomophobia, and problematic social media use. Adolescents use social media to gratify their social needs, and the rewards of this use (connecting with social groups) sustain this behavior, despite the negative consequences it may produce. However, as this study used non-probabilistic sampling methods and was cross-sectional, including adolescents in one country, the cause-effect relationships between the variables could not be assumed and the results cannot be generalized. Future studies could use stratified sampling to ensure a more representative demographic and avoid potential sampling biases. Moreover, adolescent participants may be susceptible to a social-desirability bias regarding a subject that is represented negatively on social media. In future research, mixed methods and longitudinal designs would provide further insight into the relationships between the variables.

The results of the present study reveal the need for school-based prevention and intervention programs on digital well-being, such as content-control apps for social network use, counseling, peer mentoring, and so forth. The school context plays an important role in media education regarding the safe and responsible use of social networks (see Buckingham, 2020 for a review), and offers an important socialization environment that can contribute to the psychosocial well-being of adolescents.

Conflict of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgment

This study was carried out with funding received from the call for Research Group Grants issued by the Spanish Research Agency (PID2020-113918GB-I00/ AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2024 Vanesa Pérez-Torres