Online dating apps and the association with emotional reactions: A survey on the motivations, compulsive use, and subjective online success of Chinese young adults in online dating

Vol.18,No.3(2024)

Dating applications, such as Momo, have become trendy among the young population in China. While there have been some studies on online dating applications, limited research has explored the association between these applications and adolescents’ mental health, and how they are related. This study investigates the motivations behind Chinese youth using online dating applications, the relationship between motivations and compulsive use, and their associations with subjective online success and mental health. Specifically, this study surveyed from February 2022 to March 2022, involving 451 young Chinese adults aged 18 to 35 (mean age = 25.17 years, SD = 4.25, and the biological sex distribution was 49.45% male and 50.55% female). The results indicate that motivations, including social approval, relationship seeking, sexual experiences, and socializing, were associated with adolescents’ compulsive use of online dating apps. The compulsive use of online dating apps was associated with higher reports of feelings such as joviality, sadness, and anxiety. Furthermore, the association between compulsive use and young adults’ mental health appeared to be mediated by subjective online success. The findings of this study provide a better understanding of the behavior and consequences of using online dating apps within the youth population.

dating applications; young adults; mental health; motivation; compulsive use; subjective online success; emotional reactions

Hao Gao

School of Journalism and Communication, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China

Hao Gao, PhD, is a professor at the School of Journalism and Communication, Nanjing Normal University. His research interests include social media and society, science communication, and health communication.

Huimin Yin

School of Journalism and Communication, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China

Huimin Yin is a graduate student at the School of Journalism and Communication, Nanjing Normal University. Her research interests include social media and health communication.

Zhen Zheng

School of Journalism and Communication, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China

Zhen Zheng is studying a graduate student at the School of Journalism and Communication, Nanjing Normal University. His research interests include sports communication, social media and society, and health communication.

Han Wang

School of Journalism and Communication, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

Han Wang is a doctoral candidate at School of Journalism and Communication, Jinan University. His research interests include health communication, social media effect, and quantitative research.

Aarseth, E., Bean, A. M., Boonen, H., Colder Carras, M., Coulson, M., Das, D., Deleuze, J., Dunkels, E., Edman, J., Ferguson, C. J., Haagsma, M. C., Helmersson Bergmark, K., Hussain, Z., Jansz, J., Kardefelt-Winther, D., Kutner, L., Markey, P., Nielsen, R. K. L., Prause, N., . . . Van Rooij, A. J. (2017). Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 gaming disorder proposal. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 267–270. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.088

Alexopoulos, C., Timmermans, E., & McNallie, J. (2020). Swiping more, committing less: Unraveling the links among dating app use, dating app success, and intention to commit infidelity. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 172–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.009

Apaolaza, V., Hartmann, P., Medina, E., Barrutia, J. M., & Echebarria, C. (2013). The relationship between socializing on the Spanish online networking site Tuenti and teenagers’ subjective well-being: The roles of self-esteem and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1282–1289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.01.002

Benson, V., Hand, C., & Hartshorne, R. (2019). How compulsive use of social media affects performance: Insights from the UK by purpose of use. Behaviour & Information Technology, 38(6), 549–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1539518

Chan, L. S. (2020). Multiple uses and anti-purposefulness on Momo, a Chinese dating/social app. Information, Communication & Society, 23(10), 1515–1530. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1586977

Chen, F. F., Jing, Y., Hayes, A., & Lee, J. M. (2013). Two concepts or two approaches? A bifactor analysis of psychological and subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(3), 1033–1068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9367-x

China Youth Daily. (2021, October 21). 八成受访者用过两个及以上交友软件 [80% of respondents have used two or more dating apps]. http://zqb.cyol.com/html/2021-10/21/nw.D110000zgqnb_20211021_4-10.htm

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1999). Temperament: A new paradigm for trait psychology. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 399–423). Guilford Press.

Coduto, K. D., Lee-Won, R. J., & Baek, Y. M. (2020). Swiping for trouble: Problematic dating application use among psychosocially distraught individuals and the paths to negative outcomes. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(1), 212–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519861153

Dhir, A., Yossatorn, Y., Kaur, P., & Chen, S. (2018). Online social media fatigue and psychological well-being—A study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. International Journal of Information Management, 40, 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.01.012

Doyle, E., & Palomares, M. (2021). Connecting on campus: Exploring the motivations and behaviors of college students on dating apps. Caravel Undergraduate Research Journal. https://www.sc.edu/about/offices_and_divisions/research/news_and_pubs/caravel/archive/2021_spring/2021_datingapps.php

Dyke, L., & Duxbury, L. (2011). The implications of subjective career success. Zeitschrift für ArbeitsmarktForschung, 43(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12651-010-0044-4

Estévez, A., Urbiola, I., Iruarrizaga, I., Onaindia, J., & Jauregui, P. (2017). Dependencia emocional y consecuencias psicológicas del abuso de internet y móvil en jóvenes [Emotional dependency in dating relationships and psychological consequences of Internet and mobile abuse]. Anales de psicología, 33(2), 260–268. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.2.255111

Gibbs, J. L., Ellison, N. B., & Heino, R. D. (2006). Self-presentation in online personals: The role of anticipated future interaction, self-disclosure, and perceived success in Internet dating. Communication Research, 33(2), 152–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650205285368

Goodfellow, C., Hardoon, D., Inchley, J., Leyland, A. H., Qualter, P., Simpson, S. A., & Long, E. (2022). Loneliness and personal well-being in young people: Moderating effects of individual, interpersonal, and community factors. Journal of Adolescence, 94(4), 554–568. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12046

Grace, J. B. (2006). Structural equation modeling and natural systems. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511617799

Hair Jr., J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Hair Jr., J. F., Sarstedt, M., Matthews, L. M., & Ringle, C. M. (2016). Identifying and treating unobserved heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: Part I–method. European Business Review, 28(1). https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-09-2015-0094

Heine, S. J., Lehman, D. R., Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1999). Is there a universal need for positive self-regard? Psychological Review, 106(4), 766–794. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.766

HELLOGROUP. (2022). 2021 annual report. https://momoinc.gcs-web.com/financial-information/annual-reports

Hendrick, S. S., & Hendrick, C. (1995). Gender differences and similarities in sex and love. Personal Relationships, 2(1), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00077.x

Her, Y.-C., & Timmermans, E. (2021). Tinder blue, mental flu? Exploring the associations between Tinder use and well-being. Information, Communication & Society, 24(9), 1303–1319. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1764606

Hetz, P. R., Dawson, C. L., & Cullen, T. A. (2015). Social media use and the fear of missing out (FoMO) while studying abroad. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 47(4), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2015.1080585

Higgins, L. T., Zheng, M., Liu, Y., & Sun, C. H. (2002). Attitudes to marriage and sexual behaviors: A survey of gender and culture differences in China and United Kingdom. Sex Roles, 46(3), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016565426011

Imhof, M., Vollmeyer, R., & Beierlein, C. (2007). Computer use and the gender gap: The issue of access, use, motivation, and performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(6), 2823–2837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2006.05.007

Jarman, H. K., Marques, M. D., McLean, S. A., Slater, A., & Paxton, S. J. (2021). Motivations for social media use: Associations with social media engagement and body satisfaction and well-being among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(12), 2279–2293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01390-z

Joshi, S. P., Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2014). A cross-cultural content-analytic comparison of the hookup culture in US and Dutch teen girl magazines. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(3), 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.740521

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). Problematizing excessive online gaming and its psychological predictors. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 118–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.017

Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and gratifications research. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4), 509–523. https://doi.org/10.1086/268109

Kern, M. L., Waters, L. E., Adler, A., & White, M. A. (2015). A multidimensional approach to measuring well-being in students: Application of the PERMA framework. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.936962

Kim, J., & Lee, J.-E. R. (2011). The Facebook paths to happiness: Effects of the number of Facebook friends and Self-presentation on subjective well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(6), 359–364. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0374

Kline, R. (2005). Methodology in the social sciences: Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of E-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), Article 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030311

LeFebvre, L. E. (2018). Swiping me off my feet: Explicating relationship initiation on Tinder. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(9), 1205–1229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517706419

Lexi, S. (2019). A look at the performance of the world’s leading dating apps on Valentine’s Day. data.ai. https://www.data.ai/cn/insights/market-data/dating-apps-share-of-wallet-valentines-day/

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford press.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

Liu, J., Cheng, M., Wei, X., & Yu, N. N. (2020). The Internet-driven sexual revolution in China. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 153, Article 119911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119911

Marengo, D., Poletti, I., & Settanni, M. (2020). The interplay between neuroticism, extraversion, and social media addiction in young adult Facebook users: Testing the mediating role of online activity using objective data. Addictive Behaviors, 102, Article 106150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106150

McDowell, I. (2010). Measures of self-perceived well-being. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.07.002

Ng, M. L., & Lau, M. (1990). Sexual attitudes in the Chinese. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 19(4), 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541932

Odacı, H., & Kalkan, M. (2010). Problematic Internet use, loneliness and dating anxiety among young adult university students. Computers & Education, 55(3), 1091–1097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.05.006

Orosz, G., Benyó, M., Berkes, B., Nikoletti, E., Gál, É., Tóth-Király, I., & Bőthe, B. (2018). The personality, motivational, and need-based background of problematic Tinder use. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.21

Ozimek, P., Bierhoff, H., & Hanke, S. (2018). Do vulnerable narcissists profit more from Facebook use than grandiose narcissists? An examination of narcissistic Facebook use in the light of self-regulation and social comparison theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 124, 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.12.016

Patel, V., Flisher, A. J., Hetrick, S., & McGorry, P. (2007). Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. The Lancet, 369(9569), 1302–1313. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7

Pernokis, D. (2018). Dating life experiences: An exploratory study of the interrelationships between personality, online dating and subjective well-being [Undergraduate honours thesis, The University of Western Ontario]. Undergraduate Honors Theses. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1076&context=psychK_uht

Ramayah, T., Cheah, J., Chuah, F., Ting, H., & Memon, M. A. (2018). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3.0: An updated guide and practical guide to statistical analysis (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Ranzini, G., & Lutz, C. (2017). Love at first swipe? Explaining Tinder self-presentation and motives. Mobile Media & Communication, 5(1), 80–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157916664559

Ren, F., & Wang, K. (2022). Modeling of the Chinese dating app use motivation scale according to item response theory and classical test theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), Article 13838. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113838

Rochat, L., Bianchi-Demicheli, F., Aboujaoude, E., & Khazaal, Y. (2019). The psychology of “swiping”: A cluster analysis of the mobile dating app Tinder. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(4), 804–813. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.58

Sanhaji, M. (2020). Online dating: A threat to our mental well-being or the self-validation we need? [Bachelor’s thesis, University of Twente]. University Of Twente Student Theses. https://purl.utwente.nl/essays/82051

Schivinski, B., Brzozowska-Woś, M., Stansbury, E., Satel, J., Montag, C., & Pontes, H. M. (2020). Exploring the role of social media use motives, psychological well-being, self-esteem, and affect in problematic social media use. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 617140. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.617140

Shi, W., Lin, Y., Zhang, Z., & Su, J. (2022). Gender differences in sex education in China: A structural topic modeling analysis based on online knowledge community Zhihu. Children, 9(5), Article 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9050615

Stephanie, C. (2022, February). Usage of top dating apps grew nearly 20% year-over-year in January. Sensor Tower. https://sensortower.com/blog/dating-apps-2022/

Stoicescu, M. (2020). Social impact of online dating platforms. A case study on Tinder. In 2020 19th RoEduNet Conference: Networking in Education and Research (pp. 1–6). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/RoEduNet51892.2020.9324854

Strubel, J., & Petrie, T. A. (2017). Love me Tinder: Body image and psychosocial functioning among men and women. Body Image, 21, 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.02.006

Sumter, S. R., Vandenbosch, L., & Ligtenberg, L. (2017). Love me Tinder: Untangling emerging adults’ motivations for using the dating application Tinder. Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.04.009

Timmermans, E., & De Caluwé, E. (2017). Development and validation of the Tinder Motives Scale (TMS). Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.028

Timmermans, E., De Caluwé, E., & Alexopoulos, C. (2018). Why are you cheating on Tinder? Exploring users’ motives and (dark) personality traits. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.07.040

Timmermans, E., Hermans, A., & Opree, S. J. (2021). Gone with the wind: Exploring mobile daters’ ghosting experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(2), 783–801. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520970287

Toma, C. L. (2022). Online dating and psychological well-being: A social compensation perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 46, Article 101331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101331

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2011). Online communication among adolescents: An integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.020

Valkenburg, P. M., Peter, J., & Schouten, A. P. (2006). Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 9(5), 584–590. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.584

Van Deursen, A. J., & Van Dijk, J. A. (2019). The first-level digital divide shifts from inequalities in physical access to inequalities in material access. New Media & Society, 21(2), 354–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818797082

Van Rooij, A. J., Ferguson, C. J., Colder Carras, M., Kardefelt-Winther, D., Shi, J., & Przybylski, A. K. (2018). A weak scientific basis for gaming disorder: Let us err on the side of caution. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(9), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.19

Wang, C., & Lee, M. K. (2020). Why we cannot resist our smartphones: investigating compulsive use of mobile SNS from a stimulus-response-reinforcement perspective. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 21(1), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00596

Wang, J., Gaskin, J., Wang, H., & Liu, D. (2016). Life satisfaction moderates the associations between motives and excessive social networking site usage. Addiction Research & Theory, 24(6), 450–457. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2016.1160283

Wang, J., Wang, H., Gaskin, J., & Wang, L. (2015). The role of stress and motivation in problematic smartphone use among college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 53, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.005

Weidman, A. C., Fernandez, K. C., Levinson, C. A., Augustine, A. A., Larsen, R. J., & Rodebaugh, T. L. (2012). Compensatory Internet use among individuals higher in social anxiety and its implications for well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(3), 191–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.03.003

Weinstein, A., Feder, L. C., Rosenberg, K. P., & Dannon, P. (2014). Internet addiction disorder: Overview and controversies. Behavioral Addictions, 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407724-9.00005-7

Wu, M. (2009). Structure equation model-AMOS operation and application. Chongqing University Press.

Xu, D., & Wu, F. (2019). Exploring the cosmopolitanism in China: Examining mosheng ren (“the stranger”) communication through Momo. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 36(2), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2019.1566629

Yang, C. (2018). Individualised values of happiness: exploring changing ethics in young people’s dating and relationships in post-reform China. Families, Relationships and Societies, 7(2), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674316X14676465265834

Zhang, K., Chen, C., Zhao, S., & Lee, M. (2014). Compulsive smartphone use: The roles of flow, reinforcement motives, and convenience. ICIS 2014 Proceedings, Article 64. https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2014/proceedings/HumanBehavior/64/

Authors’ Contribution

Hao Gao: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review & editing, project administration, supervision. Huimin Yin: writing—original draft. Zhen Zheng: writing—original draft. Han Wang: methodology, software, writing—original draft.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

June 28, 2023

Revisions received:

March 14, 2024

April 8, 2024

Accepted for publication:

April 15, 2024

Editor in charge:

Alexander P. Schouten

Introduction

While Tinder, the dating app that took the world by storm, was launched almost a decade ago, the popularity and usage frequency of dating apps has not diminished. According to the latest data from Sensor Tower, as of January 2022, popular dating apps like Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge have witnessed a 17% increase in usage compared to the pre-COVID-19 era (Stephanie, 2022). Although some of the world’s most popular dating apps are restricted in China, local dating apps continue to enjoy popularity. From 2017 to 2019, the number of downloads for dating apps in China’s iOS market exhibited an annual growth rate of nearly 40% (Lexi, 2019). Among them, the Chinese local dating app MOMO reached 114.1 million monthly active users in December 2021 (HELLOGROUP, 2022).

Among various age groups, it is evident that young adults, especially in China, exhibit a stronger inclination toward using dating apps. A significant proportion of dating app users in China are observed to belong to the post-90s generation (China Youth Daily, 2021). From an age perspective, dating apps offer a convenient means for young individuals growing up in the new media era to pursue their emotional aspirations by establishing romantic relationships (Patel et al., 2007). Regarding the social context, contemporary young adults’ use of dating apps reflects Chinese society’s evolving attitudes and behaviors towards relationships and dating. Compared to the pre-reform and opening-up period, Chinese young people now exhibit more liberal and open attitudes towards dating, with a growing desire for personal happiness by pursuing a liberated private life (Yang, 2018). Therefore, studying the usage of dating apps among Chinese young adults enables exploration of the interplay between their mobile media usage and emotional satisfaction and reflects the social interaction patterns of contemporary youth in the context of dating and relationships.

As evidenced by the global popularity of dating apps, they have gained widespread recognition for meeting user needs worldwide. Regarding motivation, dating apps should not solely be perceived as entertainment platforms for young individuals but as multifunctional tools catering to their diverse needs (Timmermans et al., 2018). Additionally, while online dating apps enjoy global popularity, cultural backgrounds contribute to different motivations (Joshi et al., 2014). In terms of usage patterns, prolonged use of dating apps, akin to other mobile applications, may lead to compulsive use and addictive behaviors, particularly among young adults (Estévez et al., 2017). On one hand, this compulsive use can enhance subjective online success, characterized by positive motivations, chat invitations, and matches. On the other hand, it may also lead to real-world issues, undermining users’ perceptions of online success. Therefore, viewing compulsive use as either a problem or a coping mechanism for underlying issues highlights a crucial yet under-explored area in current research. Furthermore, studies have indicated that dating apps can result in negative psychological states such as anxiety, depression, and loneliness (Coduto et al., 2020; Dhir et al., 2018). These potential risks necessitate further exploration of the psychological impact of dating app usage. Therefore, it is essential to conduct comprehensive research into how the compulsive use of dating apps relates to young adults’ initial motivations and subsequent emotional states. Understanding these dynamics would provide valuable insights into the social and psychological implications of dating app usage among young adults.

Overall, although research has explored the motivations, usage patterns, and psychological impacts of online dating app usage, the potential associations and underlying mechanisms with the mental health of young individuals remain unclear in existing studies. Thus, this study aims to investigate the usage of online dating apps among Chinese young adults, specifically focusing on motivations, compulsive use, and the association with mental health. By doing so, it aims to provide further clarification on the social psychology of young Chinese people regarding dating and relationships within the context of the new media environment.

Literature Review

Motivation and Compulsive Use of Dating Apps

Understanding the motivations behind using dating apps is crucial for studying their impact (Timmermans & De Caluwé, 2017). The Use and Gratification theory (U&G), a classical theory of media use motivation, emphasizes that individuals use media to fulfill specific needs and desires, which can also explain the popularity of dating app usage among young people (Katz et al., 1973). Previous studies have indicated that individuals use dating apps for various motivations, including leisure, entertainment, social interaction, and the pursuit of sexual and romantic relationships (LeFebvre, 2018; Ranzini & Lutz, 2017; Sumter et al., 2017; Timmermans & De Caluwé, 2017). Each of these motivations is associated with the general use of dating apps rather than explicitly addressing compulsive use. Social approval refers to users seeking validation and approval from others. Through interactions and feedback received on the app, such as likes, matches, and messages, users can experience a sense of acceptance and boost their self-esteem (Jarman et al., 2021). Relationship-seeking pertains to individuals who use the app with the explicit intention of finding potential romantic partners, as this is a primary reason why many people turn to dating apps (Doyle & Palomares, 2021). The motivation for seeking sexual experiences involves users who utilize the app to find sexual encounters or experiences, with dating apps providing a readily accessible platform for discovering and communicating with potential sexual partners. The motivation for passing the time or seeking entertainment refers to users who engage with the app for enjoyment or to fill leisure time. These users may not have a specific goal while using the app but enjoy swiping and chatting. Lastly, socializing refers to the motivation behind using the app to meet new people and expand one’s social circle. Users motivated by socializing may not solely focus on finding romantic or sexual partners but are interested in establishing new connections and friendships.

Since dating apps are widely used across the globe, it is essential to explore the motivations for their use from different cultural backgrounds (Sumter et al., 2017). In China, intimate relationships have traditionally exhibited conservative characteristics due to cultural norms and beliefs. Love and sex were once considered social taboos under Confucian philosophy (Higgins et al., 2002). However, as the economy has grown and evolved, it has brought about shifts in societal values and lifestyles, leading to changes in people’s perceptions of intimate relationships, and contemporary Chinese intimate relationships have been influenced by neoliberal values that emphasize choice, conditions, and transience (Yang, 2018). Emerging dating apps in China are primarily characterized by focusing on material considerations and accessing a larger pool of potential partners, which differs from the traditional Chinese dating model (Chan, 2020). Existing research indicates that cultural backgrounds do indeed influence differences in usage motivations. For example, a study on the motivations for using dating apps in China found that motivations such as seeking relationships, self-worth validation, and the excitement of the experience aligned with the original Western scale. However, casual encounters were not identified as a primary motivation among young Chinese individuals (Ren & Wang, 2022). Another study suggested that the motivation for self-worth validation among dating app users in North America may be more prominent than among Chinese users, as scholars believe the demand for high self-esteem is more significant in Western countries than Eastern ones (Heine et al., 1999). Overall, there is a significant research gap regarding the motivations for using dating and friendship apps within the Chinese context.

In addition, studies have confirmed the existence of compulsive use behavior when using dating apps, manifested by an increasing impulse to use these apps, and have emphasized that such behavior may negatively impact users’ emotional reactions (Her & Timmermans, 2021). Compulsive use behavior refers to the inability of individuals to reasonably control their daily behavior, resulting in abnormal consumption patterns (Hetz et al., 2015). Previous research suggests that understanding the factors contributing to compulsive use is crucial for advancing research on social media behavior, with motivation for social media use considered a critical factor in driving compulsive use (J. Wang et al., 2016). Recent studies have validated this perspective by investigating how motivations for using social media, video games, smartphones, and other media predict compulsive use behaviors (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014; Schivinski et al., 2020; J. Wang et al., 2015). However, the complex mechanisms underlying compulsive use remain unclear and require further exploration. To date, fewer studies have explicitly focused on the causes of compulsive use of dating apps (Coduto et al., 2020). Additionally, studies have shown that the motivations for using dating apps significantly differ from those for using social media, video games, smartphones, and other forms of media (Timmermans & De Caluwé, 2017). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the association between motivations for using dating apps and compulsive use. Thus, based on this, the study proposes the following research question and hypothesis:

RQ1: Among predefined motivations such as leisure, social interaction, or seeking sexual and romantic relationships, what is the primary motivation for young Chinese individuals to use dating apps?

H1: The various motivations (seeking social approval, relationships, sexual experience, and socializing) for dating apps predict compulsive use among young Chinese individuals.

Dating Apps’ Compulsive Use and Subjective Online Success

Subjective success represents a kind of self-evaluation (Dyke & Duxbury, 2011), and people who achieve subjective success often believe that they have better self-performance (Gibbs et al., 2006), perceive themselves as more attractive than others (Alexopoulos et al., 2020) and more substantial social recognition (Her & Timmermans, 2021). Specific to dating apps, subjective online success mainly manifests in users getting more positive incentives, chat invitations, and matches by using apps and perceiving higher success (Her & Timmermans, 2021). As for the association between dating app use and subjective online success, it has been argued that the logic of dating app operation materializes the process of scrutiny and evaluation (Strubel & Petrie, 2017). Additionally, the availability of information on dating app profiles can intensify users’ tendency to compare themselves with others. Users will likely experience feelings of inferiority and destructive emotions when they engage in upward social comparison or compare themselves to their idealized selves (Ozimek et al., 2018). This tendency is not conducive to promoting subjective online success. Additionally, the issue of ghosting on dating apps, which involves ending an interaction without any explanation (Stoicescu, 2020), can make users feel rejected and lead to a decrease in self-esteem levels (Timmermans et al., 2021), which is detrimental to the perception of success. On the other hand, studies have indicated a positive correlation between online dating and users’ subjective success. First, the anonymity, asynchrony, and accessibility of online communication improve the controllability of users’ self-presentation and self-disclosure (Valkenburg & Peter, 2011), which helps alleviate social anxiety and evaluation fear (Weidman et al., 2012). Carefully editing and polishing one’s self-resume allows users to present a more positive self-image (Toma, 2022), which benefits their perceived self-success (Gibbs et al., 2006). Second, a successful match on a dating app serves as an instant reward for users, representing a form of social recognition (Timmermans et al., 2018). Additionally, online communication with matched individuals can alleviate loneliness and exclusion (Sumter et al., 2017), contributing to an enhanced sense of self-worth. Furthermore, online friends can provide social support (Kim & Lee, 2011), and positive feedback from other users, such as likes and conversations, can boost the users’ self-perception and increase their feelings of attractiveness and success (Alexopoulos et al., 2020).

Since compulsive use is a problematic form of Internet use, characterized by users losing control over their Internet usage (Zhang et al., 2014), the association between compulsive use of dating apps and subjective online success is worth exploring. On the one hand, online communication can compensate for social deficits experienced by certain groups, such as individuals with social anxiety or introverts (Pernokis, 2018; Toma, 2022), and repeated use of dating apps can enhance comfort and confidence in communication (Coduto et al., 2020). Moreover, studies have shown that the more frequently users engage with social networking sites, the higher the frequency of receiving web replies, and the tone of responses tends to become more positive as the number of replies increases (Valkenburg et al., 2006). Although there are distinct differences between dating apps and social networking sites in terms of their primary purposes—dating versus socializing—the feedback mechanisms, such as receiving likes, comments, and messages, operate on a similar premise of encouraging user interaction and engagement. Therefore, theoretically, it can be assumed that users’ positive incentives from dating apps will increase with the frequency of use. The user’s compulsive use of dating apps may lead to subjective online success due to positive feedback and incentives. However, on the other hand, compulsive use is often perceived as a failed self-regulation performance that tends to result in negative behavioral outcomes. These outcomes may include feeling worthless offline, neglecting real-life social and work responsibilities (Coduto et al., 2020), increased stress and depression (Pernokis, 2018), and the emergence of withdrawal syndrome (Benson et al., 2019). All of these effects may weaken subjective online success levels.

In conclusion, there is a potential contradiction between the compulsive use of dating apps and the subjective online success of users. Frequent dating apps may increase the positive incentives for subjective online success. However, the positive effects of these incentives may be weakened by the real problems caused by compulsive use. How these two aspects are associated with an individual’s subjective online success remains underexplored. Few studies have conducted in-depth discussions on this topic, despite dating apps being equipped with features like mobility, immediacy, and others that often encourage compulsive use (Coduto et al., 2020). Therefore, it is necessary to examine the association mechanisms between compulsive use of dating apps and individual subjective online success. As a result, this study raises the following question:

RQ2: Does young adults’ compulsive use of dating apps have a positive or negative association with their subjective online success?

Dating Apps’ Compulsive Use, Subjective Online Success, and Emotional Reactions

In digital social interactions, mainly through dating apps, emotional reactions are critical in shaping users’ psychological state. These reactions, encompassing positive and negative emotions, directly influence individuals’ subjective assessment of their life satisfaction and ulfilent across various domains. In this context, subjective well-being, a broader construct, becomes relevant. Recognizing that well-being is fundamentally a subjective state characterized by a predominance of positive emotions (McDowell, 2010), it becomes evident why it is challenging to measure directly. Consequently, much scholarly effort, as highlighted by Kern et al. (2015), has been devoted to measuring the constituent dimensions of well-being, with a significant focus on emotional experiences. Bradburn et al. proposed that subjective well-being can be understood as a balance between positive and negative emotions (McDowell, 2010), a view supported by Diener, who argued that subjective well-being includes the combined experience of positive emotions, negative emotions, and life satisfaction (Chen et al., 2013). Therefore, this study aims to understand how the use of dating apps is associated with the emotional dimensions of subjective well-being, by examining the positive and negative emotions elicited through these digital social interactions.

Subjective online success is positively associated with users’ subjective well-being. Those who perceive success through online dating tools tend to experience more positive emotions than those who do not (Pernokis, 2018). Positive feedback from online interactions can enhance social self-esteem and further contribute to individual happiness (Apaolaza et al., 2013). Conversely, negative emotions such as sadness, anxiety, and anger may arise when users face rejection from others (Her & Timmermans, 2021). Individuals often use social comparisons when using dating apps to ulfil their self-evaluation needs (Her & Timmermans, 2021). Anxiety and sadness can emerge when they perceive themselves as unsuccessful (Toma, 2022), decreasing subjective well-being levels. The study mentioned above emphasizes the significance of perceived success with subjective well-being. Based on this study, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: In young dating app users, subjective online success is associated with increased positive emotions (joviality) and negative emotions (sadness and anxiety).

Given the association between compulsive use of dating apps and subjective online success, it is necessary to explore the relationship between compulsive use and subjective emotional reactions. The consensus is that compulsive use is associated with a decline in self-regulation, increased anxiety, feelings of loneliness, depression (Benson et al., 2019; Pernokis, 2018), and other negative emotions, ultimately reducing individuals’ self-esteem and well-being (Pernokis, 2018). However, some studies have found that, following compulsive use of dating apps, users also experience positive emotions (joviality) alongside negative emotions (sadness, anxiety), although the latter is more strongly associated with compulsive use (Her & Timmermans, 2021). While researchers have no consensus regarding the emotional outcomes of compulsive use, they all acknowledge its association with subjective well-being. Therefore, further investigation is required to understand the specific association mechanisms. In light of this, this study introduces the variable of subjective online success to explore how the compulsive use of dating apps is associated with users’ emotional reactions. The following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Subjective online success mediates the relationship between compulsive use of dating apps and emotional reactions, encompassing both positive and negative emotional outcomes.

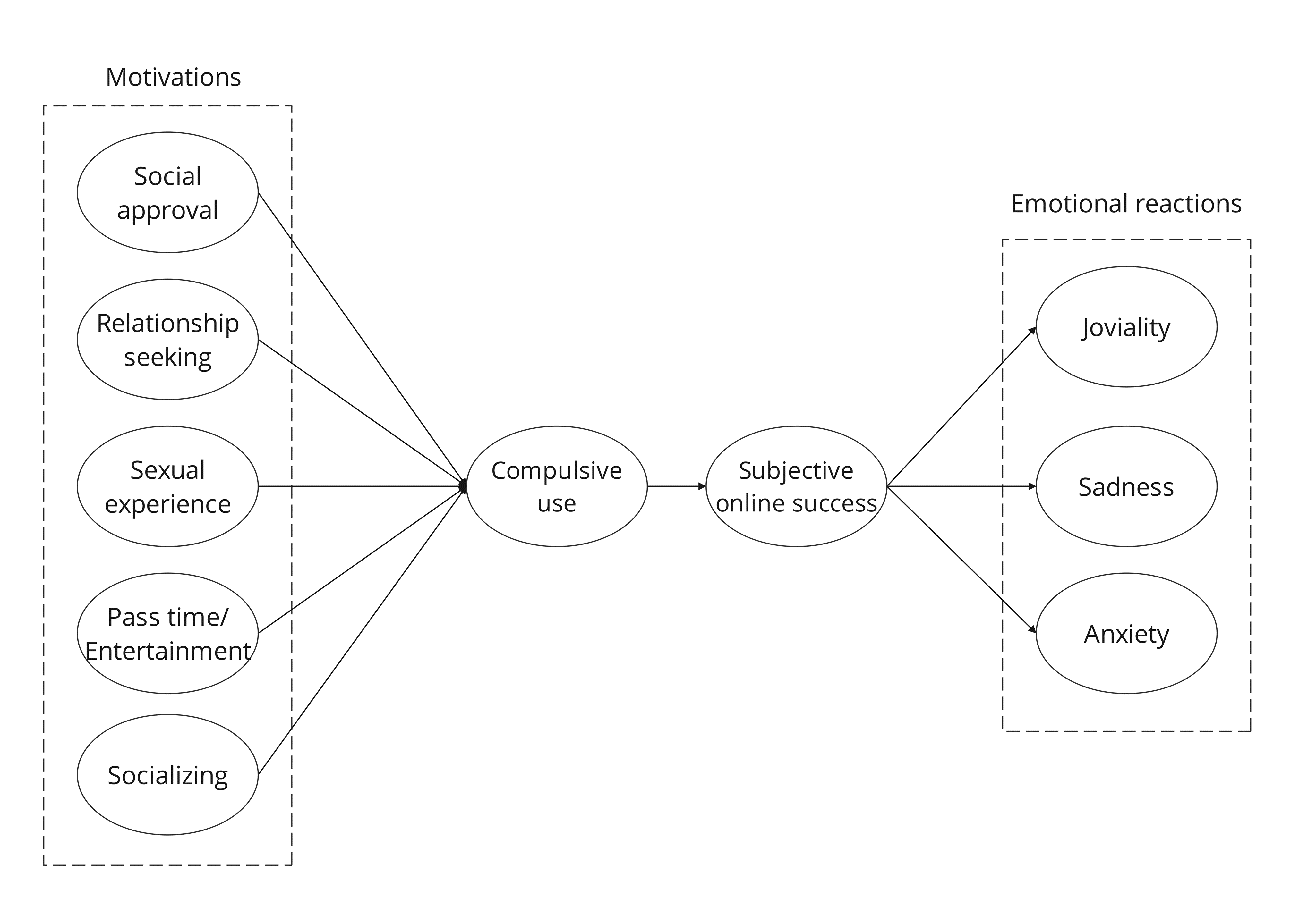

Figure 1 shows our hypothetical model.

Figure 1. The Hypothesized Model.

Methods

Study Sample

This study employed a quantitative survey design. A cross-sectional online questionnaire was distributed between February 2022 and March 2022 using Wen Juan Xin (https://www.wjx.cn/), a well-known online data collection service in China. Convenience sampling was utilized, and participants voluntarily agreed to participate by clicking the “Continue“ button and completing the questionnaire. Data completeness was ensured by requiring participants to answer all questions before submitting their responses. However, the sampling method was not randomized; the online nature of the survey aimed to achieve a diverse range of participants and broaden the potential reach of the study.

The definition and age range of “youth” can vary across disciplines and institutions. However, this study defined the youth demographic as 18–35. This age range is commonly treated as a distinct category in many existing studies, allowing for comparative analyses with users from other age groups. This approach acknowledges the internal homogeneity of the youth group aged 18–35 regarding their social media usage and their significant differences from other age groups (e.g., Marengo et al., 2020; Van Deursen et al., 2019). Therefore, the study focused on analyzing the youth demographic aged 18–35 as the main subject of analysis. A total of 451 valid responses were received, with participants averaging 25.2 years of age (SD = 4.2). The biological sex distribution was approximately 49.45% male and 50.55% female. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Social Sciences and Humanities of Jinan University (IRB No. A2207001-029).

Measures

The measures utilized in this study were developed based on relevant literature and aimed to assess various constructs, including the use of dating apps, motivation, compulsive use of dating apps, subjective online success, and emotional reactions (Table 1). Participants completed each of the measures. As the original scales were primarily tested and validated with Western samples, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed for our study. The CFA results indicated a good fit for the model, suggesting that the instruments maintained their factor structure and provided valid measurements within our research context. All subsequent data analyses were conducted using Amos 24.0 and SPSS 26.0.

Motive Scale

The motive scale assesses the motivation of young adults to use dating apps. It consists of five subscales with 24 questions in total, measuring the motivations for social approval, relationship seeking, sexual experience, entertainment/passing the time, and socializing. For instance, social approval is gauged by items such as I use dating apps for self-improvement, referencing Elisabeth Timmermans and Elien De Caluwé’s work (2017). Respondents rated these items using a seven-point Likert Scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). This study translated the scale into Chinese and performed a reliability test. The Cronbach’s alpha of the total table, social approval subscale, relationship-seeking, sexual experience, entertainment/pass time, and socializing was .917, .909, .863, .955, .922, and .912. Comparatively, the original scale reported Cronbach’s alpha values were: total scale at .92, social approval at .91, relationship seeking at .93, sexual experience at .91, entertainment/pass time at .90, and socializing at .85. These findings suggest that the translated version of the scale maintains high reliability across all subscales, closely mirroring the original scale’s performance.

Compulsive Use

The Compulsive Use Scale evaluates the addictive behaviors of young individuals on dating apps. This scale includes items such as I spend a lot of time thinking about dating apps or planning to use them and comprises three total items. It has been documented by Dhir et al. (2018), among others. Respondents rated their agreement using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The scale was translated into Chinese for this study, and reliability testing yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .785. It is slightly lower than the original scale’s alpha of .84, indicating a modest decrease in reliability. However, the scale still maintains acceptable reliability in a new cultural context.

Subjective Online Success (SOS)

The Subjective Online Success Scale, as referenced by Yu-Chin Her & Elisabeth Timmermans (2021), is designed to measure the perceived success of young adults on dating apps. It includes statements such as I consider myself successful on dating apps. The scale consists of three items, and respondents expressed their agreement using a seven-point Likert scale, where 1 signifies strongly disagree and 7 strongly agree. The scale’s reliability in this study was affirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of .849, closely aligning with the original scale’s alpha of .84. This consistency in reliability scores across different studies underscores the scale’s robustness in assessing perceived online dating success among young adults.

Emotional Reactions

The Emotional Reactions Scale assessed young individuals’ emotional reactions after using dating apps, with respondents reporting their feelings based on their experiences with dating apps over the past week. This scale includes three subscales measuring joviality, sadness, and anxiety, comprising 15 items. Respondents used a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) to indicate their responses. The Emotional Reactions Scale, incorporating subscales for joviality and sadness, references Clark & Watson (1999), while the anxiety subscale is based on Dhir et al. (2018), ensuring precise measurement of these specific emotional reactions. It includes statements such as Using dating apps makes me feel happy, Using dating apps makes me feel sad and downhearted, and Using dating apps makes me feel lonely and isolated. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the overall scale, joviality, sadness, and anxiety, were found to be .922, .911, .933, and .939, respectively. Comparatively, the original scale reported Cronbach’s alpha values were: total scale at .92, joviality at .94, sadness at .90, and anxiety at .92. These findings suggest that the translated version of the scale maintains high reliability across all subscales, closely mirroring the original scale’s performance.

Control Variables

Based on relevant literature (Her & Timmermans, 2021), several control variables were included in this study. These control variables were added to the first path (motivation-compulsive use) and the second path (compulsive use-subjective online success), as well as the third path (subjective online success-emotional reactions). The control variables included participants’ biological sex, domicile, affective state, perceived physical attractiveness, and current emotion. Regarding operationalization, biological sex was coded as 1 for males and 0 for females. Domicile was coded as 1 for rural areas and 0 for urban areas. The affective state was treated as a categorical variable, with married as the reference category and unmarried without a romantic partner, unmarried with a romantic partner, and divorced and not yet remarried being re-encoded as dummy variables. Perceived physical attractiveness was assessed by asking participants to rate their satisfaction with their physical attractiveness on a scale from 1 (strongly dissatisfied) to 7 (strongly satisfied). The current mood was assessed by asking participants to rate it on a scale from 1 (strongly unhappy) to 7 (strongly happy).

Data Analysis

The Structural Equation Model (SEM) is a multivariate statistical method that identifies, estimates, and validates various causal models (Grace, 2006).

In constructing a structural equation model, it is generally recommended to have a sample size that is at least ten times larger than the number of observed variables (Kline, 2005). Additionally, the data distribution of the explanatory variables should approximate a multivariate normal distribution to ensure the validity and reliability of the model estimation (Wu, 2009). In this study, the dataset consisted of more than ten times the number of observed variables (N = 451), and the explained variable met the assumption of multivariate normal distribution. Therefore, the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method in Amos 24.0 was used to fit this research’s structural equation model.

Before proceeding with the main study, a correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships between the identified variables (see Table 1). The correlation coefficients among all the variables were below .7, indicating a low presence of multicollinearity among the variables (Little et al., 2002). Harman’s one-factor test was performed to assess common method bias. The results revealed nine factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0, and the first factor explained 31.886% of the variance, which was below the critical threshold of 50% (Kock, 2015). Therefore, this study did not exhibit a common method bias based on Harman’s one-factor test.

Table 1. Zero-Order Pearson Correlation Among Variables (N = 451).

|

Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

1. Social approval |

1 |

||||||||

|

2. Relationship-seeking |

.43** |

1 |

|||||||

|

3. Sexual experience |

.31** |

.34** |

1 |

||||||

|

4. Pass time/Entertainment |

.40** |

.24** |

.19** |

1 |

|||||

|

5. Socializing |

.34** |

.49** |

.09* |

.51** |

1 |

||||

|

6. Compulsive use |

.51** |

.44** |

.36** |

.23** |

.30** |

1 |

|||

|

7. Subjective online success |

.54** |

.43** |

.34** |

.46** |

.43** |

.44** |

1 |

||

|

8. Sadness |

.18** |

.20** |

.43** |

.13** |

.09 |

.25** |

.20** |

1 |

|

|

9. Anxiety |

.39** |

.29** |

.42** |

.28** |

.16** |

.24** |

.32** |

.51** |

1 |

|

10. Joviality |

.53** |

.41** |

.34** |

.45** |

.45** |

.56** |

.67** |

.21** |

.30** |

|

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01. |

|||||||||

Results

Descriptive Analysis

Table 2 presents the sociodemographic information of the participants, as well as the mean and standard deviation values for the variables. The scores for socializing, entertainment/passing the time, relationship seeking, and social approval were relatively high (M > 4), indicating that these motivations were prominent among young people using dating apps. On the other hand, the scores for sexual experiences were relatively low (M = 2.650, SD = 1.616). Socializing was identified as the primary motivation for young individuals to use dating apps, with a mean score of 5.019 (SD = 1.230). Joviality was the most commonly reported emotion among young adults after using dating apps, with a mean score of 4.248 (SD = 1.253).

Table 2. Sociodemographic Information of the Participants

and Variables Information (N = 451).

|

Variable |

N (%) or Mean ± SD |

|

Year |

25.17±4.25 |

|

Biological sex |

|

|

Male |

223 (49.45) |

|

Female |

228 (50.55) |

|

Household register |

|

|

Agriculture account |

109 (24.17) |

|

Non-agricultural account |

342 (75.83) |

|

Motivations |

|

|

Social approval |

4.06±1.35 |

|

Relationship seeking |

4.32±1.36 |

|

Sexual experience |

2.65±1.62 |

|

Pass the time/Entertainment |

4.62±1.23 |

|

Socializing |

5.02±1.23 |

|

Compulsive use |

3.58±1.32 |

|

Subjective online success |

4.16±1.38 |

|

Emotional reactions |

|

|

Joviality |

4.25±1.25 |

|

Sadness |

3.26±1.34 |

|

Anxiety |

3.63±1.49 |

Measurement Model Assessment

The proposed structural equation model was developed in two steps. The first step involved building a measurement model through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to ensure an acceptable fit. The measurement model in this study successfully passed tests for convergent validity and reliability (Table 3). The hypothesis model consisted of ten latent variables and 45 observable variables. The CFA results revealed that the absolute values of the factor loadings for each observable variable exceeded .6, indicating a good representation of the motivation, impulsive use, subjective online success, and emotional reactions constructs. Additionally, all average variance extracted (AVE) values for the latent variables were more significant than .5, and all composite reliability (CR) values were above .7, indicating good reliability and convergent validity of the analysis data.

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations (HTMT) method, considered the most accurate test for determining distinctiveness between constructs (Hair Jr. et al., 2016). The results of the HTMT ratio in Table 4 demonstrated that all values were below the strict threshold of .80, indicating satisfactory discriminant effectiveness. Therefore, all variables exhibited satisfactory discriminant validity (Hair Jr. et al., 2010; Ramayah et al., 2018).

Furthermore, the CFA results indicated that the data fit the model well, as evidenced by the following fit indices: χ²/df = 2.454, p < .001, CFI = .921, TLI = .913, and RMSEA = .057. In the second step, this study assessed the measurement model for fit.

Table 3. Convergent Validity and Reliability.

|

Constructs |

Items |

Factor loadings |

CR |

AVE |

|

Social approval |

SA1 |

.829 |

.909 |

.667 |

|

SA2 |

.849 |

|||

|

SA3 |

.78 |

|||

|

SA4 |

.816 |

|||

|

SA5 |

.808 |

|||

|

Relationship seeking |

RS1 |

.714 |

.865 |

.616 |

|

RS2 |

.765 |

|||

|

RS3 |

.83 |

|||

|

RS4 |

.824 |

|||

|

Sexual experience |

SE1 |

.89 |

.956 |

.782 |

|

SE2 |

.886 |

|||

|

SE3 |

.895 |

|||

|

SE4 |

.921 |

|||

|

SE5 |

.88 |

|||

|

SE6 |

.832 |

|||

|

Pass the time/Entertainment |

PE1 |

.731 |

.904 |

.613 |

|

PE2 |

.777 |

|||

|

PE3 |

.889 |

|||

|

PE4 |

.834 |

|||

|

PE5 |

.76 |

|||

|

PE6 |

.689 |

|||

|

Socializing |

SO1 |

.897 |

.913 |

.779 |

|

SO2 |

.924 |

|||

|

SO3 |

.824 |

|||

|

Compulsive use |

CU1 |

.795 |

.798 |

.571 |

|

CU2 |

.81 |

|||

|

CU3 |

.652 |

|||

|

Subjective online success |

SOS1 |

.761 |

.852 |

.658 |

|

SOS2 |

.859 |

|||

|

SOS3 |

.811 |

|||

|

Joviality |

J1 |

.773 |

.919 |

.694 |

|

J2 |

.812 |

|||

|

J3 |

.836 |

|||

|

J4 |

.87 |

|||

|

J5 |

.87 |

|||

|

Sadness |

S1 |

.859 |

.933 |

.737 |

|

S2 |

.887 |

|||

|

S3 |

.894 |

|||

|

S4 |

.811 |

|||

|

S5 |

.838 |

|||

|

Anxiety |

A1 |

.791 |

.94 |

.757 |

|

A2 |

.898 |

|||

|

A3 |

.927 |

|||

|

A4 |

.868 |

|||

|

|

A5 |

.862 |

|

|

Table 4. Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations Result.

|

Constructs |

SA |

RS |

SE |

PE |

SO |

CU |

SOS |

J |

S |

A |

|

SA |

— |

|||||||||

|

RS |

.49 |

— |

||||||||

|

SE |

.33 |

.37 |

— |

|||||||

|

PE |

.45 |

.27 |

.21 |

— |

||||||

|

SO |

.38 |

.56 |

.10 |

.57 |

— |

|||||

|

CU |

.60 |

.53 |

.41 |

.27 |

.35 |

— |

||||

|

SOS |

.62 |

.51 |

.38 |

.52 |

.48 |

.56 |

— |

|||

|

J |

.58 |

.46 |

.37 |

.49 |

.47 |

.66 |

.77 |

— |

||

|

S |

.19 |

.22 |

.45 |

.14 |

.09 |

.29 |

.22 |

.24 |

— |

|

|

A |

.42 |

.32 |

.44 |

.30 |

.17 |

.28 |

.36 |

.33 |

.54 |

— |

|

Note. SA = Social approval, RS = Relationship seeking, SE = Sexual experience, PE = Pass the time/Entertainment, SO = Socializing, CU = Compulsive use, SOS = Subjective online success, J = Joviality, S = Sadness, A = Anxiety. |

||||||||||

Structural Model

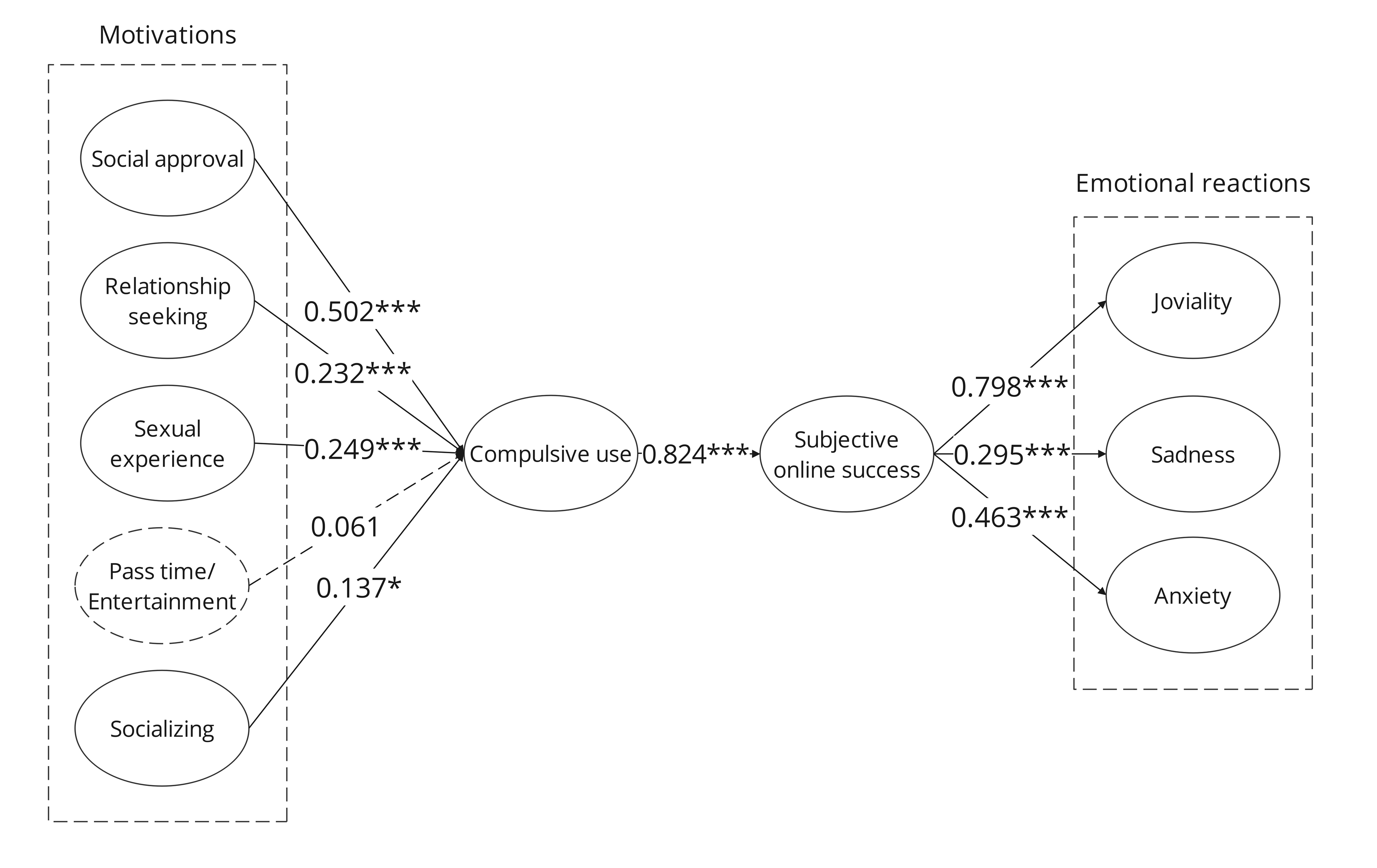

The latent structural model, as depicted in Figure 2, is presented in this section. Little (2013) argued that to achieve adequate model fit, the model must meet the following criteria: comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) > .90, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < .08 (Little, 2013). The final model in this study achieved an excellent fit: χ²/df = 2.005, CFI = .942, TLI = .932, IFI = .942, NFI = .901, and RMSEA = .047. The R2 values for the dependent variables, namely joviality, sadness, and anxiety, were .691, .157, and .229, respectively. These values indicate that the model can explain 69.1% of the variance in joviality, 15.7% in sadness, and 22.9% in anxiety among the study sample.

Figure 2. Latent Model.

The path coefficient results are presented in Table 5. The findings indicate that social approval (β = .502, p < .001), relationship seeking (β = .232, p < .001), sexual experience (β = .249, p < .001), and socializing (β = .137, p < .05) had a significant positive correlation with compulsive use. However, Pass time/Entertainment was not significantly related to compulsive use (β = .061, p = .271). Additionally, compulsive use (β = .824, p < .001) was significantly positively correlated with subjective online success. Furthermore, subjective online success exhibited a strong positive correlation with joviality (β = .798, p < .001), sadness (β = .295, p < .001), and anxiety (β = .463, p < .001). These results provide support for research hypotheses 1 and 2.

Table 5. Standardized Regression Weights According to the Latent Model.

|

Path |

B |

β |

SE |

CR |

p |

|

Path A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

SA→CU |

.422 |

.502 |

.051 |

8.286 |

<.001 |

|

RS→CU |

.212 |

.232 |

.062 |

3.399 |

<.001 |

|

SE→CU |

.174 |

.249 |

.035 |

4.995 |

<.001 |

|

PE→CU |

.058 |

.061 |

.053 |

1.100 |

.271 |

|

SO→CU |

.135 |

.137 |

.054 |

2.515 |

.012 |

|

Path B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

CU→SOS |

.977 |

.824 |

.088 |

11.111 |

<.001 |

|

Path C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

SOS→J |

.707 |

.798 |

.049 |

14.327 |

<.001 |

|

SOS→S |

.295 |

.295 |

.056 |

5.252 |

<.001 |

|

SOS→A |

.476 |

.463 |

.058 |

8.263 |

<.001 |

Post-Hoc Analysis

Given the ongoing interest in whether media usage behavior exhibits biological sex-related differences, we additionally analyzed variance (Imhof et al., 2007). The analysis of variance presented in Table 6 was used to examine whether there were significant differences in the core variables between men and women in this study. The findings indicated significant differences between men and women in terms of using dating apps for relationship-seeking and sexual experiences. Males reported higher motivation for relationship-seeking and sexual experiences compared to females. Additionally, males scored higher on compulsive use of dating apps compared to females. Furthermore, men were more likely to experience sadness and anxiety after using dating apps than women.

Table 6. Results of Variance Analysis (N = 451).

|

|

Biological sex (Mean ± SD) |

F |

p |

|

|

|

Female (n = 228) |

Male (n = 223) |

||

|

Social approval |

4.01 ± 1.43 |

4.11 ± 1.27 |

0.539 |

.463 |

|

Relationship seeking |

4.09 ± 1.42 |

4.55 ± 1.26 |

13.717 |

< .001** |

|

Sexual experience |

2.08 ± 1.39 |

3.23 ± 1.63 |

64.629 |

< .001** |

|

Pass the time/Entertainment |

4.67 ± 1.29 |

4.58 ± 1.16 |

0.572 |

.450 |

|

Socializing |

5.05 ± 1.25 |

4.99 ± 1.21 |

0.27 |

.604 |

|

Compulsive use |

3.40 ± 1.33 |

3.76 ± 1.30 |

8.547 |

.004** |

|

Subjective online success |

4.06 ± 1.42 |

4.26 ± 1.33 |

2.328 |

.128 |

|

Joviality |

4.14 ± 1.26 |

4.35 ± 1.24 |

3.195 |

.075 |

|

Sadness |

2.99 ± 1.27 |

3.55 ± 1.36 |

20.285 |

< .001** |

|

Anxiety |

3.42 ± 1.43 |

3.85 ± 1.53 |

9.321 |

.002** |

|

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01. |

||||

Discussion

This study examined the use of dating apps among young people in China and its association with their mental health. The findings suggest that the primary motivations for young Chinese people to use dating apps are socializing (M = 5.019, SD = 1.230) and passing time/entertainment (M = 4.622, SD = 1.228). It is followed by relationship seeking (M = 4.318, SD = 1.358) and social approval (M = 4.061, SD = 1.353), indicating the versatility of dating apps and the diverse motivations of users. The reasons why young people tend to use dating apps for social interaction can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, during their youth, individuals are in a critical period of social and emotional development (Odacı & Kalkan, 2010) and may experience feelings of loneliness (Goodfellow et al., 2022). Dating apps provide them a platform to connect with others and ulfil their social needs. Secondly, online dating apps facilitate the creation of profiles and encourage users to interact and communicate with individuals who share common interests (Kuss & Griffiths, 2017). It enables young people to expand their social networks more efficiently and effectively (Orosz et al., 2018). Users can form new relationships and engage in meaningful social interactions by connecting with like-minded individuals. Furthermore, dating apps act as a bridge between users and strangers. Location-based mobile dating apps offer the convenience of offline communication for users in the same geographical region. This feature allows people to find like-minded friends and engage in various activities, such as sports or parties (Xu & Wu, 2019). Overall, using dating apps among young people for social interaction addresses their social and emotional needs, expands their social networks, and establishes connections with like-minded individuals. These platforms provide opportunities for socializing, creating new relationships, and combating feelings of loneliness.

In our research, it is noteworthy that the motivation for sexual experience was found to be the least important among the usage motivations for dating apps, consistent with previous findings. Prior studies have suggested that pursuing sexual experiences is not the primary motivation for using dating apps in China (Ren & Wang, 2022). These studies have attributed this East-West difference to cultural discrepancies between samples, which give rise to different incidental factors. The conservative sexual culture background and immature sex education system in traditional Chinese concepts may contribute to this difference (Shi et al., 2022). Confucianism, which emphasizes etiquette, has traditionally imposed moral and social norms restricting individuals, including inhibiting sexual needs and expressions (Ng & Lau, 1990). Even today, sexual conservatism continues to influence Chinese society, where sexual permissiveness is often equated with sexual indulgence (Liu et al., 2020). In addition to our planned analyses, we conducted a post-hoc analysis to explore potential differences in the motivations for dating apps and the emotional experiences associated with their use based on biological sex. Our study found differences in the motivations for dating apps and emotional experiences between individuals of different biological sexes. Consistent with existing research, males were found to be more motivated by sexual experiences than females. It could be attributed to men generally having a more laissez-faire attitude towards casual sex, being more inclined towards game-like love, and using the Internet more frequently to seek sexual partners (Hendrick & Hendrick, 1995; Sumter et al., 2017). Our study revealed that males were more likely to experience sadness and anxiety after using dating apps. It could be because female users are generally more likely to receive online matches and engage in conversations than male users, thus feeling more recognized and validated (Alexopoulos et al., 2020). On the other hand, male users may face higher chances of rejection, frustration due to no responses, or feelings of unattractiveness, which can contribute to their higher levels of sadness and anxiety in online dating (Sanhaji, 2020).

Furthermore, the study found that motivations such as social approval, relationship seeking, socializing, and sexual experiences were associated with impulsive use of dating apps. This finding aligns with the use and gratification theory, which suggests that individuals use specific media to ulfil specific needs and desires (Katz et al., 1973). In the context of dating apps, users seek to satisfy physical needs (e.g., sexual pleasure), social needs (e.g., finding a partner or friends), psychosocial needs (e.g., validating attractiveness), and other dimensions of needs (Rochat et al., 2019). However, as users’ initial motivations are fulfilled, new needs emerge, and individuals tend to rely on familiar tools, such as dating apps, to satisfy these new needs (Timmermans & De Caluwé, 2017). This cycle of instant gratification can lead to repetitive, compulsive behaviors and overuse of dating apps (C. Wang & Lee, 2020; Zhang et al., 2014). Additionally, the immediate rewards, such as companionship, communication, and connection, that users experience during their use of dating apps, coupled with the fear of missing out on information, can reinforce the impulse to constantly and compulsively use dating apps to maintain positive feelings (C. Wang & Lee, 2020). It is worth noting that although entertainment is one of the primary motivations for using dating apps, it is a standard function shared by various mobile applications and not a unique characteristic of dating apps. Therefore, the satisfaction of the entertainment motivation alone is not necessarily associated with compulsive use of dating apps.

Additionally, our research demonstrated the association between compulsive use and subjective online success. The anonymity, asynchrony, and accessibility of dating apps enhance users’ sense of control, recognition, and self-esteem (Valkenburg & Peter, 2011). According to the social compensation hypothesis, online dating platforms serve as a means of compensating for social deficits experienced by specific individuals, such as neurotic or introverted, by enabling them to autonomously create and develop social relationships (Pernokis, 2018). This online environment can make them feel safer, more effective, more confident, and more comfortable using dating apps (Coduto et al., 2020). Individuals with social deficits are more likely to develop compulsive use behaviors because online communication allows for greater comfort and self-disclosure (Weinstein et al., 2014). As the frequency of app usage increases, users receive more positive incentives and instant rewards, such as matches, compliments, and conversations. These experiences contribute to the enhancement of their self-worth and subjective online success. While compulsive use may bring difficulties to users’ offline lives and undermine their sense of success in the real world (Benson et al., 2019), within the context of online dating apps, it can act as a positive incentive, improving users’ subjective sense of success in utilizing these applications. It is essential to acknowledge the perspective that, when reflecting on the broader implications of compulsive use, such behavior may not solely signify problematic media use but can also represent a coping mechanism for other underlying personal problems. As scholars like Christopher Ferguson, Andrew Przybylski, Amy Orben, Espen Aarseth, and Antonius J. van Rooij, among others, have argued against attributing game disorder to a disease (Aarseth et al., 2017; Van Rooij et al., 2018). Our research conclusions have recognized the dual nature of compulsive use; only by realizing compulsive applications as a multifaceted phenomenon can we better appreciate its potential as both a source of challenge and a form of emotional sustenance for individuals facing social and personal difficulties.

In addition to being associated with subjective online success, compulsive use also relates to emotional reactions through the mediating variable of subjective online success. Research has indicated an association between subjective online success and emotional reactions (Her & Timmermans, 2021). Although the findings of this study suggest a relationship between subjective online success and both positive and negative emotions, overall, users report experiencing joviality more than sadness and anxiety. That is, subjective online success predicts emotional reactions positively. In other words, joviality is more vital for those who perceive success in dating apps than others. While subjective online success is positively associated with emotional reactions, compulsive use indirectly related to emotional reactions through subjective online success, which means that users perceive anxiety and sadness while feeling happy. This point suggests that compulsive use is related to variations in the user’s emotional reactions. While positive incentives from dating apps increase with the frequency of use (Zhang et al., 2014), compulsive use negatively affects users’ real lives, such as weakening the perceived value of offline (Her & Timmermans, 2021) and negatively impacting mental health. Therefore, while dating apps bridge social barriers and provide positive incentives, we also need to focus on the real-life and psychological distress caused by impulsive use, promote healthy interpersonal communication through regular, limited use of dating apps, and avoid negative emotions followed by impulsive use.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study employs structural equation modeling (SEM) and path analysis to investigate the association between online dating apps and emotional reactions among young Chinese adults. While these methods offer robust analytical frameworks, they present inherent challenges in establishing causal relationships. Additionally, the study faces limitations in accurately distinguishing between compulsive and enthusiastic media use with the current scale, suggesting that the complexity of compulsive behaviors and the nuanced differences between enjoyment and compulsion are not fully captured. Another significant limitation is our study’s lack of measurement regarding participants’ sexual orientation, which results in a homogenized view of user experiences with the dating app Momo. This approach fails to consider how motivations and emotional experiences might vary across different sexual orientations. It neglects the exploration of gender diversity by primarily assuming participants are heterosexual, cisgender individuals. Such omissions limit our understanding of the dynamics of dating app use in the context of gender diversity. This aspect is crucial for comprehensively understanding these platforms’ impact on well-being.

Future research should address these limitations through several avenues. Firstly, employing experimental designs and integrating multiple methodologies could strengthen causal inferences and provide a more dynamic understanding of the effects of online dating app usage over time. Secondly, refining the measurement of compulsive media use is imperative. It involves improving scale items related to critical constructs like “relapse” and “conflict” to differentiate compulsive use from enthusiastic engagement effectively. Lastly, incorporating a detailed examination of sexual orientation and gender identity among dating app users is essential. By doing so, future studies can offer a more inclusive and nuanced understanding of dating app usage and its effects, potentially leading to more accurate assessments and interventions that cater to the diverse experiences of users.

Conclusion

This study investigated the motivations, behaviors, and consequences of using dating apps among young people in China to assess the relationships between media use motivation, compulsive use, subjective online success, and emotional reactions. The results indicate that the motivations of social approval, relationship-seeking, sexual experience, and socializing are related to the compulsive use of online dating apps among young adult groups. Compulsive use of online dating apps was associated with an increase in users’ subjective online success, which was related to higher levels of joviality, sadness, and anxiety. In conclusion, this study provides insights into dating apps from the Chinese cultural context and enriches the study of intimate relationships in the digital age.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgement

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2024 Hao Gao, Huimin Yin, Zhen Zheng, Han Wang