When sadists become internet trolls: The mechanism of aggressive humor and self-concept clarity

Vol.20,No.1(2026)

Prior research has confirmed that the Dark Tetrad's sadism trait is a contributing factor to Internet trolling. However, little is yet known about how and under what circumstances sadism has an effect. From the perspective of expression styles and individual differences of trolls, the purpose of this study is to explore the potential mediating role of aggressive humor in the link between sadism and Internet trolling, as well as the moderating role of self-concept clarity. A total of 530 Chinese online users' data were collected on the Credamo platform and analyzed using PROCESS for SPSS. Sadistic traits were found to be positively correlated with Internet trolling. Moderated mediation analyses showed that aggressive humor played a mediating role between sadism and Internet trolling. Specifically, sadistic individuals were more likely to have aggressive humor, which further triggered Internet trolling. In addition, self-concept clarity moderated the direct relationship between sadism and Internet trolling. Specifically, higher self-concept clarity increased the association between sadism and Internet trolling. This study enriches our understanding of the mediating and moderating mechanisms linking sadistic traits to Internet trolling, allowing us a glimpse into the minds of Internet trolls and the sadistic motivations behind their behavior.

Internet trolling; sadism; aggressive humor; self-concept clarity

Shuqing Gao

Faculty School of Communication, Soochow University, Suzhou, China

Shuqing Gao (Ph.D. from Beijing Normal University, 2021) is currently a Lecturer at the School of Communication, Soochow University. His research interests include cyber psychology, health communication, and internet governance.

Yuqin Yang

Faculty School of Communication, Soochow University, Suzhou, China

Yuqin Yang (M.A. from Soochow University, 2023) is currently a Ph.D. candidate at the School of Communication, Soochow University. Her research focuses on science communication.

Bo Jiang

Faculty School of Communication, Soochow University, Suzhou, China

Bo Jiang (M.A. from Jiangxi Normal University, 2001) is currently a Professor and Doctoral Supervisor at the School of Communication, Soochow University. His recent research focuses on media psychology and communication, as well as critical communication in academic journals.

Guoyan Wang

Faculty School of Communication, Soochow University, Suzhou, China

Guoyan Wang (Ph.D. from University of Science and Technology of China, 2016) is currently a Distinguished Professor at the School of Communication, Soochow University. Her research focuses on intelligent communication, science communication, health communication, and data visualization.

Achuthan, K., Nair, V. K., Kowalski, R., Ramanathan, S., & Raman, R. (2023). Cyberbullying research — Alignment to sustainable development and impact of COVID-19: Bibliometrics and science mapping analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 140, Article 107566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107566

Alfasi, Y. (2022). Attachment style and social media fatigue: The role of usage-related stressors, self-esteem, and self-concept clarity. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 16(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2022-2-2

Allen, J. J., Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2017). The general aggression model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.034

Anderson, E. C., Carleton, R. N., Diefenbach, M., & Han, P. K. J. (2019). The relationship between uncertainty and affect. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 2504. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02504

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

Baumeister, R. F., Tice, D. M., & Vohs, K. D. (2018). The strength model of self-regulation: Conclusions from the second decade of willpower research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 141–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617716946

Becht, A. I., Nelemans, S. A., van Dijk, M. P. A., Branje, S. J. T., Van Lier, P. A. C., Denissen, J. J. A., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2017). Clear self, better relationships: Adolescents' self-concept clarity and relationship quality with parents and peers across 5 years. Child Development, 88(6), 1823–1833. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12921

Bishop, J. (2013). The effect of deindividuation of the internet troller on criminal procedure implementation: An interview with a hater. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 7(1), 28–48. https://www.cybercrimejournal.com/pdf/Bishop2013janijcc.pdf

Bishop, J. (2014). Representations of ‘trolls’ in mass media communication: A review of media-texts and moral panics relating to ‘internet trolling’. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 10(1), 7–24. https://jonathanbishop.com/Library/Documents/EN/docIJCCPaper_Hater.pdf

Brubaker, P. J., Montez, D., & Church, S. H. (2021). The power of schadenfreude: Predicting behaviors and perceptions of trolling among Reddit users. Social Media + Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211021382

Buckels, E. E., Trapnell, P. D., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Trolls just want to have fun. Personality and Individuals Differences, 67, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.016

Buckels, E. E., Trapnell, P. D., Andjelovic, T., & Paulhus, D. L. (2019). Internet trolling and everyday sadism: Parallel effects on pain perception and moral judgment. Journal of Personality, 87(2), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12393

Burger, C. (2022). Humor styles, bullying victimization and psychological school adjustment: Mediation, moderation and person-oriented analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), Article 11415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811415

Campbell, J. D., Assanand, S., & Di Paula, A. (2003). The structure of the self-concept and its relation to psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality, 71(1), 115–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.t01-1-00002

Campbell, J. D., Trapnell, P. D., Heine, S. J., Katz, I. M., Lavallee, L. F., & Lehman, D. R. (1996). Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(1), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.141

Center, C. I. N. I. (2024). The 53th China statistical report on Internet development. https://www.cnnic.cn/NMediaFile/2024/0325/MAIN1711355296414FIQ9XKZV63.pdf

Cheng, J., Bernstein, M., Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil, C., & Leskovec, J. (2017). Anyone can become a troll: Causes of trolling behavior in online discussions. In CSCW ’17: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (pp. 1217–1230). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2998181.2998213

Chester, D. S., DeWall, C. N., & Enjaian, B. (2018). Sadism and aggressive behavior: Inflicting pain to feel pleasure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(8), 1252–1268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218816327

Coles, B. A., & West, M. (2016). Trolling the trolls: Online forum users constructions of the nature and properties of trolling. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.070

Curșeu, P. L., Gheorghe, A., Bria, M., & Negrea, I. C. (2022). Humor in the sky: The use of affiliative and aggressive humor in cabin crews facing passenger misconduct. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 32(6), 781–796. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-03-2022-0060

DeHart, T., & Pelham, B. W. (2007). Fluctuations in state implicit self-esteem in response to daily negative events. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(1), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.01.002

Dynel, M. (2016). “Trolling is not stupid”: Internet trolling as the art of deception serving entertainment. Intercultural Pragmatics, 13(3), 353–381. https://doi.org/10.1515/ip-2016-0015

Fichman, P., & Sanfilippo, M. R. (2016). Online trolling and its perpetrators: Under the cyberbridge. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Foulkes, L. (2019). Sadism: Review of an elusive construct. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, Article 109500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.07.010

Fullwood, C., James, B. M., & Chen-Wilson, C. (2016). Self-concept clarity and online self-presentation in adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(12), 716–720. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0623

Griffiths, M. (2014). Adolescent trolling in online environments: A brief overview. Education and Health, 32(3), 85–87. https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/25950

Gruner, C. R. (1997). The game of humor: A comprehensive theory of why we laugh. Transaction Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315132174

Gylfason, H. F., Sveinsdottir, A. H., Vésteinsdóttir, V., & Sigurvinsdottir, R. (2021). Haters gonna hate, trolls gonna troll: The personality profile of a Facebook troll. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), Article 5722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115722

Han, Y., Donnelly, H. K., Ma, J., Song, J., & Hong, H. (2019). Neighborhood predictors of bullying perpetration and victimization trajectories among South Korean adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(7), 1714–1732. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22226

Hardaker, C. (2013). “Uh. . . . not to be nitpicky,,,,,but…the past tense of drag is dragged, not drug.”: An overview of trolling strategies. Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict, 1(1), 58–86. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlac.1.1.04har

Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

Hong, F., & Cheng, K.-T. (2018). Correlation between university students’ online trolling behavior and online trolling victimization forms, current conditions, and personality traits. Telematics and Informatics, 35(2), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.12.016

Kurtça, T. T., & Demirci, İ. (2022). Psychopathy, impulsivity, and Internet trolling: Role of aggressive humour. Behaviour & Information Technology, 42(15), 2560–2571. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929x.2022.2133635

Lee, S. Y., Yao, M. Z., & Su, L. Y. (2021). Expressing unpopular opinion or trolling: Can dark personalities differentiate them? Telematics and Informatics, 63, Article 101645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101645

Levey, E. K. V., Garandeau, C. F., Meeus, W., & Branje, S. (2019). The longitudinal role of self-concept clarity and best friend delinquency in adolescent delinquent behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(6), 1068–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-00997-1

Lian, Y., Zhou, Y., Lian, X., & Dong, X. (2022). Cyber violence caused by the disclosure of route information during the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), Article 417. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01450-8

Liu, Q., Li, Z., & Zhu, J. (2024). Online self-disclosure and self-concept clarity among Chinese middle school students: a longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 53(6), 1469–1479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-024-01964-1

Maltby, J., Day, L., Hatcher, R. M., Tazzyman, S., Flowe, H. D., Palmer, E. J., Frosch, C. A., O’Reilly, M., Jones, C., Buckley, C., Knieps, M., & Cutts, K. (2015). Implicit theories of online trolling: Evidence that attention‐seeking conceptions are associated with increased psychological resilience. British Journal of Psychology, 107(3), 448–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12154

Manuoğlu, E. (2020). Differences between trolling and cyberbullying and examination of trolling from self-determination theory perspective [Doctoral dissertation, The Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University]. https://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/12625470/index.pdf

Manuoğlu, E., & Öner-Özkan, B. (2022). Sarcastic and deviant trolling in Turkey: Associations with dark triad and aggression. Social Media + Society, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051221126053

March, E., & Marrington, J. (2019). A qualitative analysis of internet trolling. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(3), 192–197. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0210

March, E., & Steele, G. (2020). High esteem and hurting others online: Trait sadism moderates the relationship between self-esteem and internet trolling. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(7), 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0652

Martin, R. A. (2007). The psychology of humor: An integrative approach. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012372564-6/50024-1

Martin, R. A., Lastuk, J. M., Jeffery, J., Vernon, P. A., & Veselka, L. (2012). Relationships between the dark triad and humor styles: A replication and extension. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 178–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.010

Martin, R. A., Puhlik-Doris, P., Larsen, G., Gray, J., & Weir, K. (2003). Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: Development of the Humor Styles Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(1), 48–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-6566(02)00534-2

Masui, K. (2019). Loneliness moderates the relationship between dark tetrad personality traits and internet trolling. Personality and Individual Differences, 150, Article 109475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.06.018

Masui, K., Tamura, A., & March, E. (2018). Development of a Japanese version of the global assessment of Internet trolling-revised. The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 89(6), 602–610. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.89.17229

McGraw, A. P., & Warren, C. (2010). Benign violations: Making immoral behavior funny. Psychological Science, 21(8), 1141–1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610376073

Meng, X., Li, C., Liu, D., & Xu, Y. (2022). The super-short dark tetrad: Development and validation within the Chinese context. Personality and Individual Differences, 188, Article 111459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111459

Moor, L., & Anderson, J. R. (2019). A systematic literature review of the relationship between dark personality traits and antisocial online behaviours. Personality and Individual Differences, 144, 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.027

Morrissey, L. (2010). Trolling is a art: Towards a schematic classification of intention in internet trolling. Griffith Working Papers in Pragmatics and Intercultural Communications, 3(2), 75–82. https://www.scribd.com/doc/165364052/2-Morrisey-Trolling-pdf

Navarro-Carrillo, G., Torres-Marín, J., & Carretero-Dios, H. (2021). Do trolls just want to have fun? Assessing the role of humor-related traits in online trolling behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 114, Article 106551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106551

Ng, J. C. Y., Linya, Z., & Qingmei, T. (2019). “Internet troll”: A classical grounded theory research on how individuals create group culture and interaction. Journal of Jiangnan University (Humanities & Social Sciences Edition), 18(4), 38–49. https://caod.oriprobe.com/articles/57080609/_Internet_troll___A_classical_grounded_theory_rese.htm

Nitschinsk, L., Tobin, S. J., & Vanman, E. J. (2022). The disinhibiting effects of anonymity increase online trolling. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 25(6), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2022.0005

O’Meara, A., Davies, J., & Hammond, S. (2011). The psychometric properties and utility of the Short Sadistic Impulse Scale (SSIS). Psychological Assessment, 23(2), 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022400

Pabian, S., De Backer, C. J., & Vandebosch, H. (2015). Dark triad personality traits and adolescent cyber-aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 75, 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.015

Parise, M., Pagani, A. F., Donato, S., & Sedikides, C. (2019). Self‐concept clarity and relationship satisfaction at the dyadic level. Personal Relationships, 26(1), 54–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12265

Park, M. S.-A., Golden, K. J., Vizcaino-Vickers, S., Jidong, D., & Raj, S. (2021). Sociocultural values, attitudes and risk factors associated with adolescent cyberbullying in East Asia: A systematic review. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 15(1), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2021-1-5

Paulhus, D. L., Buckels, E. E., Trapnell, P. D., & Jones, D. N. (2021). Screening for dark personalities. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 37(3), 208–222. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000602

Pfattheicher, S., Keller, J., & Knezevic, G. (2018). Destroying things for pleasure: On the relation of sadism and vandalism. Personality and Individual Differences, 140, 52–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.03.049

Ruch, W., & Proyer, R. T. (2009). Extending the study of gelotophobia: On gelotophiles and katagelasticists. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 22(1–2), 183–212. https://doi.org/10.1515/HUMR.2009.009

Sanfilippo, M. R., Fichman, P., & Yang, S. (2018). Multidimensionality of online trolling behaviors. The Information Society, 34(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2017.1391911

Sanfilippo, M., Yang, S., & Fichman, P. (2017). Trolling here, there, and everywhere: Perceptions of trolling behaviors in context. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 68(10), 2313–2327. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23902

Scheel, T., Gerdenitsch, C., & Korunka, C. (2016). Humor at work: validation of the short work-related Humor Styles Questionnaire (swHSQ). Humor - International Journal of Humor Research, 29(3). https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2015-0118

Sest, N., & March, E. (2017). Constructing the cyber-troll: Psychopathy, sadism, and empathy. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 69–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.038

Strimbu, N., & O’Connell, M. (2019). The relationship between self-concept and online self-presentation in adults. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(12), 804–807. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0328

Torres-Marín, J., Navarro-Carrillo, G., & Carretero-Dios, H. (2018). Is the use of humor associated with anger management? The assessment of individual differences in humor styles in Spain. Personality and Individual Differences, 120, 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.040

Tsukawaki, R., & Imura, T. (2021). The relationship between self-isolation during lockdown and individuals’ depressive symptoms: Humor as a moderator. Social Behavior and Personality an International Journal, 49(7), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.10248

Van Dijk, M. P. A., Branje, S., Keijsers, L., Hawk, S. T., Hale, W. W., & Meeus, W. (2014). Self-concept clarity across adolescence: Longitudinal associations with open communication with parents and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(11), 1861–1876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0055-x

Veselka, L., Schermer, J. A., Martin, R. A., & Vernon, P. A. (2010). Relations between humor styles and the dark triad traits of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(6), 772–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.01.017

Wang, X., Yang, J., Wang, P., & Lei, L. (2019). Childhood maltreatment, moral disengagement, and adolescents' cyberbullying perpetration: Fathers' and mothers' moral disengagement as moderators. Computers in Human Behavior, 95, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.031

Wilson, N. C., & Seigfried-Spellar, K. C. (2022). Cybervictimization, social, and financial strains influence Internet trolling behaviors: A general strain theory perspective. Social Science Computer Review, 41(3), 967–982. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393211065868

Wu, B., Li, F., Zhou, L., Liu, M., & Geng, F. (2022). Are mindful people less involved in online trolling? A moderated mediation model of perceived social media fatigue and moral disengagement. Aggressive Behavior, 48(3), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.22013

Wu, B., Zhou, L., Deng, Y., Zhao, J., & Liu, M. (2022). Online disinhibition and online trolling among Chinese college students: The mediation of the dark triad and the moderation of gender. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 25(11), 744–751. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2022.0046

Wu, J., Watkins, D., & Hattie, J. (2010). Self-concept clarity: A longitudinal study of Hong Kong adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(3), 277–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.10.011

Yang, J., Li, W., Wang, W., Gao, L., & Wang, X. (2021). Anger rumination and adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration: Moral disengagement and callous-unemotional traits as moderators. Journal of Affective Disorders, 278, 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.090

Zhou, J., Zou, F., Pan, C., & Gong, X. (2025). Longitudinal relations between internalizing problem and peer aggression among Chinese early adolescents: Highlighting the role of self-concept clarity. European Journal of Personality. https://doi.org/10.1177/08902070251348692

Authors’ Contribution

Shuqing Gao: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, writing—review & editing. Yuqin Yang: writing—original draft, conceptualization, investigation. Bo Jiang: supervision, methodology. Guoyan Wang: supervision, review, project administration, funding acquisition.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

June 25, 2023

Revisions received:

May 24, 2024

April 9, 2025

September 8, 2025

Accepted for publication:

November 13, 2025

Editor in charge:

Michel Walrave

Introduction

The Internet has increasingly become a major platform for people to communicate and exchange ideas. As of December 2023, more than 1.092 billion people in China have access to the Internet, and the number of Internet users continues to rise (Center, 2024). The continuous development of information and communication technologies has enabled a number of irrational behaviors in cyberspace, such as cyberbullying (Achuthan et al., 2023), cyber violence (Lian et al., 2022), and Internet trolling (B. Wu, Li et al., 2022).

Currently, the prevalence of Internet trolling is considerably significant. A 2018 study found that 74% of a sample of university students in China had been victims of Internet trolling at least once in the previous week (Hong & Cheng, 2018). A 2019 study showed that 25% of participants in Australia exhibited trolling behavior (March & Marrington, 2019), while a similar 2022 study in the United States found that 55% of subjects confessed to engaging in Internet trolling (Wilson & Seigfried-Spellar, 2022). Given that such aggressive online behavior has been shown to cause non-negligible negative effects on its victims, such as psychological distress (March & Marrington, 2019), depression (Hong & Cheng, 2018), and even self-harm behaviors and suicidal thoughts (Coles & West, 2016), exploring the influencing factors of Internet trolling has become a concern for many scholars. To date, most research on Internet trolling has been conducted in North America and Europe. The strong collectivist overtones of Asian cultures may have a dampening effect on individuals' offline expressions of authentic emotions and behaviors (Park et al., 2021), and it has been suggested that this could lead to individuals being more likely to exhibit online deviant behaviors in anonymous online spaces (Han et al., 2019).

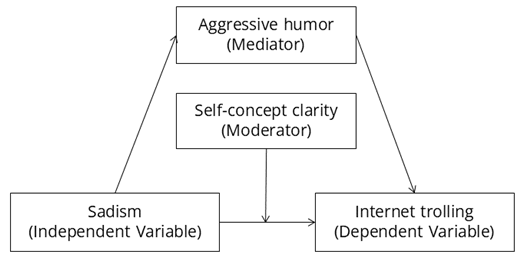

This study examines the effects of sadism, aggressive humor, and self-concept clarity on Internet trolling in a Chinese context. In particular, a moderated mediation model (see Figure 1) is constructed, which may help to explain the complexity of Internet trolling.

Literature Review

Internet Trolling

Internet trolling is a relatively new phenomenon that has become more widespread over the past decade (Maltby et al., 2015). The term “trolling” is derived from the concept of a troll, a legendary beast that lurks beneath bridges seeking to ensnare unsuspecting pedestrians (Fichman & Sanfilippo, 2016). Internet trolling is a specific type of antisocial behavior in cyberspace (Cheng et al., 2017), defined as “a repetitive, disruptive online deviant behavior by an individual toward other individuals or groups” (Fichman & Sanfilippo, 2016). It consists primarily of deliberately inflammatory, disruptive, or even offensive posts or comments made under anonymous conditions (Buckels et al., 2014) to evoke unpleasant emotions (e.g., frustration or anger) in other discussion participants (Masui, 2019). Internet trolls create conflictual behavior for the purpose of provoking others (Bishop, 2014; Dynel, 2016; Sanfilippo et al., 2018) and for enjoyment and fun (March & Marrington, 2019).

Sadism and Internet Trolling

Internet trolling has causes rooted deep in the personality. Related studies have found many similarities between the traits displayed by Internet trolls and antisocial personality traits, such as a penchant for joking with others, deception, manipulation, and ruthlessness (Bishop, 2013). On this basis, scholars have focused their attention on personality traits and found that the Dark Tetrad personality is particularly prominent in Internet trolls (Gylfason et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2021; Manuoğlu & Öner-Özkan, 2022). The first of the four dark personality traits is Machiavellianism, which is mainly characterized by the manipulation and deception of others; the second is narcissism, which consists of a “distorted sense of self-importance and pomposity” and is mainly self-centered; the third is psychopathy, which is often associated with antisocial tendencies and a lack of empathy; and the fourth is sadism, the tendency to experience pleasure from the physical or psychological suffering of others (O'Meara et al., 2011; Pfattheicher et al., 2018).

Although all the above four dark personality traits have been positively associated with trolling, only sadism and psychopathy have been found to reliably predict trolling behavior (Buckels et al., 2014). It has been established that sadism is a strong predictor of Internet trolling (Buckels et al., 2019; Pabian et al., 2015). In two online studies, Buckels et al. (Buckels et al., 2014) found that Internet trolling was positively correlated with sadism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism in the Dark Tetrad of personality, with trolling being most closely associated with sadism. This was the first study to show a reliable link between Internet trolling tendencies and sadism. Meanwhile, given that sadists enjoy making others uncomfortable in online chats and arguments, Buckels concluded that trolls appear to be an online manifestation of everyday sadism. Individuals with highly sadistic traits are believed to be more likely to exhibit antisocial behaviors (Foulkes, 2019), deriving pleasure from their cruelty to others both online and offline (Sest & March, 2017). Even after controlling for individual psychopathy, Machiavellianism, narcissism, and other aggressive traits, sadistic traits still show a significant association with Internet trolls (Buckels et al., 2019). Research on the differences between Internet trolls and outspoken minorities has shown that Internet trolls have significantly higher psychopathic and sadistic traits than others, and that only sadistic traits are a unique marker for distinguishing the two groups (Lee et al., 2021). An empirical study of trolling on Facebook has also shown that sadism is a strong predictor of Internet trolling (Gylfason et al., 2021). However, the cross-cultural applicability of these findings in the Asian context still needs to be further tested. This paper focuses on the applicability of sadism and Internet trolling findings to China, Asia's largest developing country. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H1: Sadism has a positive predictive impact on Internet trolling.

Aggressive Humor as a Mediator

While sadism may be a direct predictor of Internet trolling, more research on internal mechanisms, such as mediation mechanisms, is necessary to improve our understanding of Internet trolling and conceptualize effective interventions accordingly.

Humor style is defined as the tendency to use behaviors associated with humor in everyday life (Torres-Marín et al., 2018), and is broadly classified into four types: (i) affiliative humor, the use of harmless jokes to strengthen interpersonal and social connections; (ii) self-defeating humor, the use of self-mockery or self-deprecation to gain social acceptance from others; (iii) self-enhancing humor, the maintenance of a humorous outlook on life as a way of building self-resilience; and (iv) aggressive humor, the use of hostile jokes and pranks to ridicule others and entertain oneself (Martin et al., 2003). Among them, affiliative humor and self-enhancing humor are positive and adaptive, while aggressive humor and self-defeating humor are negative and destructive (Martin, 2007). Humor style has been shown to be a mediating factor in a number of studies on a range of topics. For example, in the link between the bullying of students and their school adjustment, the usage of humor can reduce or motivate students' victimization behavior according to the context, which in turn affects their school adjustment (Burger, 2022). Humor style can also have a buffering effect between transgressive passenger behavior and the stress experienced by flight attendants (Curșeu et al., 2022). In addition, aggressive humor has been shown to negatively affect people's mental health during an epidemic lockdown, acting as a mediator that enhances the relationship between self-isolation and depression, thereby making people more likely to suffer depression during the lockdown (Tsukawaki & Imura, 2021). Based on this, the potential mediating role of aggressive humor in the link between sadism and Internet trolling deserves further exploration and verification.

There are three reasons why we think aggressive humor can play a mediating role between sadism and Internet trolling. First, sadism is potentially related to aggressive humor. The “dark” tendencies associated with humor have been shown to be strongly associated with dark personality traits (Navarro-Carrillo et al., 2021). For example, Veselka et al. (2010) investigated the correlation between dark personality and humor style, and found that aggressive humor is positively correlated with psychotic tendencies and Machiavellianism (Veselka et al., 2010). Positive correlations have also been found between aggressive humor and personality traits such as apathy, interpersonal manipulation, arrogance, and disregard for traditional morality (Martin et al., 2012). According to the general aggression model, personal factors (e.g., personality traits) and situational factors (e.g., aggressive cues) influence an individual's current internal state, which in turn influences his or her assessment and decision-making processes, influencing the decision of whether or not to act impulsively (Allen et al., 2017). According to this reasoning, it is possible that sadism (a personality factor) activates an aggressive humor style, which in turn influences an individual's tendency to engage in trolling behavior.

Second, people with higher levels of aggressive humor are more likely to engage in Internet trolling. Dynel (2016) viewed humor as an internal experience or behavior, suggesting that online trolls seek to entertain themselves and others at the expense of particular individuals. Navarro-Carrillo et al. (2021) clarified the “dark” humorous nature of Internet trolls: trolls are more likely to experience joy in laughing at others and to use aggressive humor in their daily lives. Ruch and Proyer (2009) described three interrelated but distinct dispositions towards ridicule and being ridiculed: joy at being ridiculed (gelotophilia), fear of being ridiculed (gelotophobia), and joy at ridiculing others (katagelasticism). The latter two dispositions show a certain “dark” tendency. By combining college students' perceptions of Internet trolls’ behavior with concepts relating to the media and academia, Sanfilippo et al. (Sanfilippo et al., 2018) suggested that there exists a humorous type of Internet troll that tends to be sarcastic about the vulnerability of others. This is actually the classic embodiment of aggressive humor: mocking others with hostile jokes and pranks for self-amusement (Martin et al., 2003). Of the four types of humor styles, aggressive humor has been shown to be most closely associated with Internet trolling. Empirical research from Spain has also shown that people who score higher on aggressive humor tests are more likely to express anger at others (Torres-Marín et al., 2018).

The risk-enhancing effect suggests that one risk factor can enhance the impact of another (Wang et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2021). Thus, when people with more pronounced dark personality traits concurrently have a higher degree of negative humor, they are more likely to engage in Internet trolling. In addition, existing empirical studies (Kurtça & Demirci, 2022) have found that aggressive humor mediates the relationship between impulsiveness and Internet trolling. Individuals with higher sadistic traits tend to enjoy more aggression, and the degree of this enjoyment predicts the extent of the aggression (Chester et al., 2018). Given these experimental findings, the relationship between sadistic traits and aggressive humor deserves further exploration. In this regard, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Aggressive humor mediates the relationship between sadism and Internet trolling.

Self-Concept Clarity as a Moderator

While sadism may significantly influence an individual's Internet trolling behavior, not all individuals with significant sadistic traits actually develop Internet trolling behavior. Internet trolls often try to cause online conflict to satisfy their own psyche, and thus the question arises of whether their inner self-conflict also plays an important role. Are internally conflicted sadists more likely to become internet trolls?

Self-concept clarity is the degree to which individuals are certain about the content of their self-concept, and this degree of certainty is internally consistent and stable over time (Campbell et al., 1996). It is considered to be an individual qualitative factor. As high self-concept clarity provides a clear understanding and coherent sense of self, it is generally associated with positive behavioral states. Research has shown that, in general, people holding a stable and consistent view of themselves report higher levels of adjustment and well-being (Campbell et al., 2003; Parise et al., 2019). Research on adolescence, in particular, has documented that higher self-concept clarity is related to different positive outcomes, such as lower levels of anxiety and depression (Van Dijk et al., 2014), higher self-esteem (J. Wu et al., 2010), and higher quality relationships with peers and parents (Becht et al., 2017). Uncertainty theory states that uncertainty about the self is experienced as being disgusting and uncomfortable, and that such uncertainty can therefore cause negative emotional and cognitive responses (Anderson et al., 2019). At the same time, individuals tend to act impulsively when they don't have the resources (such as self-concept clarity) to make a thoughtful assessment of their current situation (B. Wu, Zhou et al., 2022). Individuals with lower self-concept clarity are more likely to exhibit inconsistencies between their offline and online selves and are more likely to engage in frequent online self-representation (Strimbu & O'Connell, 2019), which may lead to an online disinhibition effect, weakening individual behavioral constraints, and in turn leading to cyberbullying and related phenomena (Liu et al., 2024). According to this logic, high self-concept clarity (a clear, internal, cognitive process) may inhibit sadism (a negative personality factor) and thus affect individuals' propensity to engage in Internet trolling. In other words, individuals with low self-concept clarity are more susceptible to low aggressive humor and sadism, which can lead to Internet trolling. A prior study on self-concept clarity and bullying has found that children who engage in cyberbullying have lower levels of self-concept clarity than average children (Baumeister et al., 2018). Conversely, high self-concept clarity would be expected to be a potentially important factor in inhibiting cyberbullying. Given that trolls exhibit one of the manifestations of cyberbullying (Griffiths, 2014; Morrissey, 2010) and that trolling is similar to cyberbullying (Brubaker et al., 2021).

Self-concept clarity usually plays a moderating role between personality traits and the corresponding behaviors, and this role has been demonstrated in studies on many topics. For example, studies on the relationship between individual differences in attachment style and the experience of fatigue resulting from extensive social media users have found that the mediating role of Facebook anxiety in the association between attachment anxiety and social media fatigue is moderated by self-concept clarity. Specifically, in individuals with less coherent and integrated self-concept, high attachment anxiety led to higher levels of Facebook anxiety, which in turn led to social media use fatigue (Alfasi, 2022). Self-concept clarity was also found to moderate the relationship between adolescents and their best friend's level of delinquency, with adolescents with lower self-concept clarity being more likely to be influenced by their friends' delinquency and then commit a crime (Levey et al., 2019). Previous research (Fullwood et al., 2016) has also shown that adolescents with lower self-concept clarity tend to exhibit an online self that is more inconsistent with their offline self. Moreover, the lower an individual’s self-concept clarity, the greater the deviance of his or her online behavior (Strimbu & O'Connell, 2019). Given the potential inhibitory effects that high self-concept clarity may have on Internet trolling, this paper argues that high self-concept clarity is a positive factor influencing the behavior of Internet trolls. It can largely overcome the negative effects of sadism and aggressive humor. People with high self-concept clarity are less likely to develop negative cognitions when exposed to negative stimuli in their daily activities (Campbell et al., 1996) reducing the likelihood of triggering abusive tendencies. Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: The direct association between sadism and Internet trolling is stronger in individuals with low self-concept clarity and weaker in individuals with high self-concept clarity.

In summary, Figure 1 presents the model of our hypothesized relationships.

Figure 1. The Hypothesized Model.

Methods

Participants

In this study, 559 Chinese online users were surveyed using a random sampling method through the Credamo platform. The survey was conducted anonymously. Credamo is the top online survey and data collection platform in China with more than 3 million national samples. To increase the randomness of the survey samples and make the research conclusions more objective and accurate, this paper did not set any limits in terms of age, education, speciality, or geographical selection. After the questionnaires were formally collected, 29 non-compliant questionnaires (i.e. cases in which Internet trolling scored 0 and polygraph questions were failed) were rejected to ensure the validity of the collection.

After completing the questionnaire, each respondent received a reward of CNY 5. The valid sample used in the analysis consisted of 530 valid responses (94.8% response rate; Mage = 30.92 years, SD = 7.35 years), of whom 349 (65.7%) were women.

Procedure

Data for this study were collected in November 2022. Prior to the formal test, data collectors informed participants that participation was voluntary and that they could refuse to answer questions and withdraw at any time if they felt uncomfortable. Participants were assured that their responses would be kept confidential and would only be used for academic research.

Mediation and moderation effects were tested with PROCESS version 4 (Hayes, 2012). A bootstrap analysis with 5,000 replicates was used to verify the significance of the paths. The path coefficient was considered to be significant if the confidence interval did not include 0.

Measures

Sadism

Sadism is part of the dark tetrad, alongside Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy. Some studies have shown that other dark personalities such as subclinical psychopathy play a role in this antisocial behavior. Given the overlap between sadism and the remaining Dark Tetrad traits, many relevant authors (Moor & Anderson, 2019; Paulhus et al., 2021) have recommended measuring these constructs jointly, rather than simply assessing sadism alone. In this sense, sadism was tested by using the super-short Dark Tetrad scale, which is a short version of the Dark Tetrad scale modified and developed by Meng et al. for use in the Chinese context. It has been demonstrated that this scale has good reliability estimation and item attributes with Chinese samples (Meng et al., 2022). The scale is divided into the four dimensions of Machiavellianism, narcissism, psychopathy, and sadism, and includes a total of 16 items. Four of these items measure sadism; sample items are, Watching a fist-fight excites me and I enjoy watching violent sports. A 7-point Likert scale was adopted, from 1 = very much agree to 7 = very much disagree. All the scales for measurements shared similar labels. It is worth noting that at the time of writing, we only calculated scores on the sadism subscale in an attempt to draw more accurate conclusions. The final scores are mean scores of the sadistic traits items, with a higher score indicating a higher level of sadistic traits. In this study, the scale had a good reliability (α = .71).

Aggressive Humor

Aggressive humor was measured using the shortened version of the Humor Styles Questionnaire (Scheel et al., 2016). The authors have demonstrated the validity and reliability of the scale in both its German and English versions. The scale consists of the four dimensions of affiliate humor, self-enhancing humor, aggressive humor, and self-defeating humor, with a total of 12 questions. Three of these items measure aggressive humor; sample items are, if someone makes a mistake, I will often tease them about it and if I don't like someone, I often use humor or teasing to put them down. All items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale. It is worth noting that at the time of writing, we only calculated scores on aggressive humor. The final scores are mean scores of the aggressive humor items, with a higher score indicating a higher level of aggressive humor. The scale had a good reliability in this study (α = .80).

Self-Concept Clarity

The measure of self-concept clarity was chosen from the scale developed by Campbell et al. (1996). The Chinese version of this scale has been widely used to measure the clarity and uniformity of people's self-concept. This paper uses all 12 items of the questionnaire, such as my beliefs about myself often conflict with one another and on one day I might have one opinion of myself and on another day I might have a different opinion. Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale. The final score is the mean of all items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-concept clarity. The measure had excellent reliability in this study (α = .94).

Internet Trolling

Internet trolling was measured using the Global Assessment of Internet Trolling-revised (GAIT; Sest & March, 2017). The GAIT consists of items that measure feelings and attitudes related to Internet trolling, such as the degree to which one enjoys Internet trolling and the sense of unity with Internet trolls, in addition to items that ask about experiences of Internet trolling. This version of the scale has been translated into Japanese and applied by Japanese scholars and has been shown to have good retest reliability and standard correlation validity (Masui et al., 2018). Given the similarity of the Japanese and Chinese cultural backgrounds, we chose the Japanese version of this scale to translate into Chinese.

The scale comprises a total of eight items, such as I have disturbed people on the Internet (social media and news websites, etc.) in comment sections and news feeds (new information and updates displayed on timelines such as SNS) and I have shared or sent controversial segments on the Internet because they were funny. All items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = not at all true of me to 7 = extremely true of me. The final score is the mean of all items, with a higher score indicating a higher level of Internet trolling. In our present research sample, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient was .94.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

We conducted Pearson's correlation analysis on the overall mean scores of sadism, aggressive humor, self-concept clarity, and Internet trolling. Means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations (r) were calculated for all study variables and are given in Table 1.

The means and standard deviations of the four main variables were as follows: sadism (M = 2.38, SD = 0.95), Internet trolling (M = 2.67, SD = 0.66), aggressive humor (M = 2.36, SD = 0.97), and self-concept clarity (M = 4.71, SD = 0.93). The results show that Internet trolling was positively and significantly associated with sadism (r = .53, p < .001) and negatively correlated with self-concept clarity (r = −.32, p < .001). Aggressive humor was positively and significantly correlated with sadism (r = .33, p < .001) and Internet trolling (r = .47, p < .001). Self-concept clarity was negatively and significantly correlated with sadism (r = −.42, p < .001) and Internet trolling (r = −.32, p < .001). These findings suggest that sadism and aggressive humor are predictors of Internet trolling, while high self-concept clarity is a protective factor.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for All Variables.

|

Variables |

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1. Gender |

0.658 |

0.475 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Age |

30.922 |

7.353 |

−.146*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

3. Education |

4.124 |

0.430 |

.107* |

.011 |

— |

|

|

|

|

4. Internet trolling |

2.670 |

0.665 |

−.158*** |

.013 |

−.092* |

— |

|

|

|

5. Sadism |

2.375 |

0.954 |

−.131** |

−.096* |

.006 |

.534*** |

— |

|

|

6. Aggressive humor |

2.357 |

0.972 |

−.123** |

.0374 |

−.076 |

.469*** |

.333*** |

— |

|

7. Self-concept clarity |

4.707 |

0.932 |

−.043 |

.250*** |

.143** |

−.323*** |

−.415*** |

−.277*** |

|

Note. Gender was dummy coded: 1 = man, 0 = woman. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. |

||||||||

The Relationship Between Sadism and Internet Trolling: Testing the Moderated Mediation Model

Model_5 in PROCESS for SPSS (Hayes, 2012) was used to test the mediating effect of aggressive humor and the moderating effect of self-concept clarity in the relationship linking sadism to Internet trolling, controlling for gender, age, and education. The results (see Table 2) indicate that sadism was a significant predictor of aggressive humor (β = 0.33, p < .001), and aggressive humor, in turn, was a significant predictor of Internet trolling (β = 0.30, p < .001). Sadism was a significant predictor of Internet trolling (β = 0.53, p < .001), and the direct predictive effect of sadism on Internet trolling was still significant after adding the mediating variables (β = 0.43, p < .001). In addition, the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval for the indirect effect of aggressive humor excluded zero; CI = [0.04, 0.11].

Table 2. Mediation and Moderation Model Tests.

|

Variables |

Model 1 Internet trolling (result variable) |

Model 2 Aggressive humor (result variable) |

Model 3 Internet trolling (result variable) |

|||

|

β |

t |

β |

t |

β |

t |

|

|

Gender |

−0.071 |

−1.898 |

−0.064 |

−1.520 |

−0.051 |

−1.443 |

|

Age |

0.054 |

1.453 |

0.060 |

1.440 |

0.058 |

1.624 |

|

Education |

−0.088 |

−2.411* |

−0.072 |

−1.753 |

−0.048 |

−1.395 |

|

Sadism |

0.529 |

14.293*** |

0.330 |

7.944*** |

0.434 |

10.32*** |

|

Aggressive humor |

|

|

|

|

0.303 |

8.213*** |

|

Self-concept clarity |

|

|

|

|

−0.092 |

−2.310*** |

|

Sadism×Self-concept clarity |

|

|

|

|

0.091 |

2.382* |

|

R2 |

0.302 |

0.125 |

0.401 |

|||

|

F |

56.858*** |

18.732*** |

49.844*** |

|||

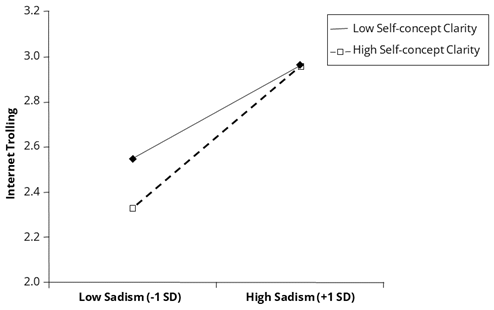

At the same time, the product term of self-concept clarity and sadism was a significant predictor of Internet trolling (β =0.09, p = .018). In other words, the effect of sadism on Internet trolling was significantly moderated by self-concept clarity. As shown in Figure 2, further simple slope analysis showed that when self-concept clarity was low (M − 1 SD), sadism had a significant positive predictive effect on Internet trolling (simple slope = 0.22, p = .015). When self-concept clarity was high (M + 1 SD), the positive predictive effect of sadism was still present, but stronger (simple slope = 0.56, p < .001). This suggests that, as the self-concept clarity of an individual increases, the predictive effect of sadism on Internet trolling increases.

Figure 2. The Moderating Role of Self-Concept Clarity in the Relationship Between Sadism and Internet Trolling.

Discussion

Overall, our hypotheses were partially supported: sadism positively predicted Internet trolling (H1 was supported), and aggressive humor mediating that impact (H2 supported). We also found that self-concept clarity moderated the direct relationship between sadism and Internet trolling, but this finding was opposite our H3: the positive association was stronger at high than at low levels of self-concept clarity.

The Relationship Between Sadism and Internet Trolling

Our results support existing conclusions about the positive correlation between sadism and Internet trolling (Gylfason et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2021; Navarro-Carrillo et al., 2021; Nitschinsk et al., 2022), validating the negative impact of sadistic traits as a negative factor on individuals. Thus, to some extent, Internet trolling can be seen as a form of online sadism (Buckels et al., 2019). Studies from China have shown that online platforms have become a tool for people to vent their emotions when they are stressed (Ng et al., 2019). In our study, people who scored higher on the sadism subscale also scored higher on questions such as The purer and more beautiful a thing is, the more satisfaction I get from destroying it and I find it funny when I see someone fall on their face when filling out the Global Assessment of Internet Trolling scale. Our results suggest that highly sadistic individuals tend to deliberately inflict pain in order to demonstrate their power and dominance over others, or to derive pleasure from others' pain (O'Meara et al., 2011). People with higher levels of sadism enjoy the process of hurting others (Sanfilippo et al., 2017) and use the Internet to perpetuate their suffering (Buckels et al., 2014). From this perspective, Internet trolling can be seen as a mechanism for individuals to vent their sadistic tendencies, gaining pleasure and enjoyment by verbally attacking others in cyberspace. In conclusion, sadism is a significant predictor of Internet trolling.

The Mediating Role of Aggressive Humor

This study found that aggressive humor plays a mediating role in the relationship between sadism and Internet trolling.

The results of this paper are consistent with the findings of prior research, which have shown that negative humor styles are strongly associated with dark personality traits and disruptive behaviors. People with aggressive humor lack empathy and may not consider the negative impact of such humor on others, as it may be sexist or racist and therefore hurtful. Humorous trolling is identified as one of the dimensions of Internet Trolling (Sanfilippo et al., 2018; Kurtça & Demirci, 2022). One of the motivations of trolls is humor (Navarro-Carrillo et al., 2021), with humor and mocking comments serving as triggers for trolling (Manuoğlu, 2020). Hence, it is thought that people might exhibit trolling behavior just to have fun. However, Internet trolls may also exhibit behaviors like joking about a sensitive issue. For amusement, they may impart advice potentially jeopardizing the safety of others (Coles & West, 2016; Hardaker, 2013). Aggressive humor, as a motive, involves laughing at the pain of other Internet users as a way of having fun (Buckels et al., 2019). This motivation may lead individuals to harm others in order to obtain their own humorous experiences of entertainment (Dynel, 2016). Those who score higher on aggressive humor tend to express anger at others (Torres-Marín et al., 2018), and attacking others' vulnerability is a typical trolling behavior (Sanfilippo et al., 2018).

Aggressive humor is highly consistent with the core trait of sadism. This seems be in accordance with certain aspects of Superiority Theory (Gruner, 1997), in that it suggests that humor arises from an attempt to enhance self-superiority by belittling and ridiculing others. Sadists may particularly enjoy this sense of superiority and power manifested through humor. Furthermore, in light of the Benign Violation Theory (McGraw & Warren, 2010), the anonymity and virtuality of the online environment may reduce the “benign” component of aggressive humor, making it more likely to be interpreted purely as a “violation” behavior, thus amplifying its aggressiveness and harmfulness. In the online environment, aggressive humor can become a convenient way for sadists to engage in aggressive behavior, satisfying their sadistic desires while masking their true intentions under the guise of jokes or banter and thereby evading moral condemnation and social pressure. Thus, aggressive humor is not only a humor style but also an aggressive form of expression and a behavioral strategy that serves sadistic personality traits. Other factors may also play mediating roles. For example, dehumanization could be an important potential mechanism (Haslam, 2006). Sadists may tend to view others online as mere objects lacking emotions and humanity. This could reduce their empathy and sense of moral constraints, making it easier for them to engage in cyber violence and aggressive behavior. Moral disengagement may also play a role (Bandura, 1999). Sadists may be more likely to use various cognitive strategies to justify their Internet trolling behavior, believing, for example, that “it’s just online joking, no need to be serious,” “the victim is also problematic,” etc., thus reducing their feelings of guilt and responsibility.

In addition, the impact of humor style as a negative factor affecting the individual's psychological state cannot be ignored. Victims of cyberbullying who bully others use aggressive humor more frequently than other humor styles (Burger, 2022). In some special situations (e.g., during epidemic prevention and control), the adverse effects of aggressive humor on an individual's mental health greatly increase the likelihood that he or she will develop depression (Tsukawaki & Imura, 2021). Together, these results shed light on the dark humorous nature of this pervasive antisocial Internet behavior (Navarro-Carrillo et al., 2021).

The Moderating Effect of Self-Concept Clarity

This study found that self-concept clarity plays a moderating role in the direct effects of sadism on Internet trolling. Specifically, the direct effect of sadism on Internet trolling was stronger in individuals with high self-concept clarity.

A potential explanation for this unexpected moderation effect is that self-concept clarity, while usually related to psychological adjustment and stability (Becht et al., 2017; Campbell et al., 2003), may not consistently serve as a protective factor. Individuals with high self-concept clarity typically exhibit a clearly defined and stable self-perception, potentially enhancing the congruence between their internal characteristics and external actions. Consequently, for individuals with elevated levels of sadism, a coherent and stable self-concept may bolster the manifestation of their sadistic inclinations in digital environments, such as trolling. Conversely, individuals with lower self-concept clarity may encounter heightened self-doubt and internal discord (J. Wu et al., 2010), potentially undermining the direct manifestation of sadistic traits into explicit trolling behaviors. This interpretation aligns with recent research indicating that self-concept clarity serves as a “double-edged sword”: it promotes adaptive functioning for prosocial traits but may intensify maladaptive outcomes when associated with dark personality traits (Levey et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2025).

This rationale is additionally corroborated by pertinent findings regarding self-esteem. March and Steele (2020) established that explicit self-esteem positively correlated with Internet trolling exclusively in individuals exhibiting high levels of trait sadism, suggesting that self-esteem amplified rather than alleviated the relationship between sadism and trolling. Considering that self-concept clarity is a substantial predictor of self-esteem (DeHart & Pelham, 2007), our results correspond with this trend: individuals exhibiting high levels of sadism and possessing a clear, stable self-concept are particularly prone to manifest their sadistic inclinations through trolling. Collectively, these findings indicate that self-related factors, including self-esteem and self-concept clarity, do not consistently function as protective buffers against antisocial online behaviors; instead, within the framework of dark personality traits, they may serve as catalysts that promote the expression of those traits.

The current findings possess significant theoretical implications. The moderating impact of self-concept clarity contests the dominant belief that self-related constructs, including self-esteem and self-concept clarity, are consistently beneficial. Our findings indicate a more intricate viewpoint: self-concept clarity may serve as a “double-edged sword,” mitigating maladaptive outcomes when associated with prosocial characteristics, yet intensifying antisocial behaviors when coupled with dark personality traits. This insight enhances self-concept theory by underscoring its conditional effects and the significance of examining trait–self interactions in online aggression models.

While the data analysis in this paper focused on the role of self-concept clarity as a moderator in the relationship between sadism and Internet trolling, it is also important to acknowledge that, from a statistical perspective, self-concept clarity could also be construed as a mediating variable. However, based on theoretical considerations, we believe that framing self-concept clarity as a moderator is more consistent with our study’s theoretical framework and research objectives. It is more likely that self-concept clarity influences the expression and intensity of sadistic personality traits, rather than acting as the core mechanism driving Internet trolling behavior. Viewing self-concept clarity as a moderator better captures how it shapes the situational conditions under which sadistic tendencies translate into actual Internet trolling behavior. Future research could further explore the possible role of self-concept clarity as a mediating variable, but the focus of our current study is to examine its crucial role as a contextual moderator.

Limitations and Implications

Although this research confirms that sadism can directly predict Internet trolling, it has some limitations.

First, Internet trolling is an undesirable antisocial behavior, and as a result, participants may have intentionally underreported their trolling behavior when answering the questionnaire. Future research through field experiments or big data studies is a possible way to reduce the limitations caused by subjectivity.

Second, the gender ratio in the research sample was somewhat uneven, with a higher percentage of women (65.7%) than men. There is also some room for balance in the sample's age and education ratios, which may limit the generalizability of these findings. Future studies could therefore collect data from groups of different genders, ages, and educational attainment in a more balanced manner to extend generalizability.

Third, because cross-sectional data were used in this study, it is still necessary to conduct experimental and longitudinal studies to pinpoint causal relationships. Also, most of the scales we chose were originally developed in English (with the exception of the Japanese GAIT-R Scale), and we asked master's degree students majoring in foreign languages to translate them individually and independently, and the authors of this article then integrated them in a unified manner. However, the validity of these scales has not been previously studied in a Chinese setting, which may affect the validity of the results. In addition, the use of a more comprehensive and reliable measurement tool could have reduced the limitations imposed by the measurement tools.

Notably, we found that even when controlling for other Dark Tetrad traits (i.e., Machiavellianism and narcissism) in the model, psychopathy still showed a significant indirect effect on Internet trolling through aggressive humor. This suggests that, in addition to sadism, psychopathy may also contribute to Internet trolling behavior through the mediating effect of aggressive humor. Psychopathy, characterized by impulsivity, a lack of empathy, and antisocial tendencies, may drive individuals to use aggressive humor as a tool for manipulation and dominance in online interactions. Unlike sadism, which centers on deriving pleasure from others’ suffering, psychopathy’s indirect contribution through aggressive humor might stem from a broader desire for power and control, and a disregard for the social norms that discourage the use of humor to do harm. However, due to the limitations of our current model, we have not developed this in detail in this study.

To some extent, this study supplements and expands our understanding of the topic of Internet trolling, specifically the causes of Internet trolling. We emphasize the personality (sadism) and aggressive humor styles that underly Internet trolling, taking into account a cognitive factor (self-concept clarity), thus enriching the ecological model of this highly concerning online phenomenon. Future research could further explore how emotional mechanisms and potential cultural differences affect individual Internet trolls. In addition, the results of this study can help guide targeted interventions for online trolling behavior. For example, the government and social organizations should strive to create a harmonious social environment to help reduce the accumulation of individual psychological problems. Similarly, schools should strive to create an environment conducive to learning by incorporating curriculum content to help students actively understand, position, and accept themselves. Keeping students confident and sane can help reduce blind exclusion behaviors and thus reduce the likelihood of competition with others online and offline. Finally, effective social support, strict cyberspace norms, and timely psychological guidance can also help individuals develop more rational online communication behaviors.

Conclusions

In summary, this study found that: (1) sadism has a positive predictive effect on Internet trolling; (2) aggressive humor plays a mediating role in the relationship between sadism and Internet trolling; (3) the direct effect of sadism on Internet trolling is moderated by self-concept clarity. Sadistic traits had a greater predictive effect on Internet trolling in individuals with low self-concept clarity. In conclusion, Internet trolls exhibit a desire for cruelty and a tendency to underestimate the suffering of others. These findings provide a glimpse into the minds of Internet trolls and further confirm the sadistic motivations behind their behavior.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Use of AI Services

The authors declare they have not used any AI services to generate or edit any part of the manuscript or data.

Acknowledgement

The study was not with an analysis plan in an independent, institutional registry. Data will be shared in public repository before publication.

This study was funded by the key project of the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant. 24&ZD184), the Humanities and Social Sciences Fund of the Ministry of Education (Grant. 23YJCZH052), Jiangsu Social Science Fund (23XWC002), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant. 82273744).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2026 Shuqing Gao, Yuqin Yang, Bo Jiang, Guoyan Wang