Profiles of bullying, cyberbullying, and disinterest in reading among primary school learners in Spain

Vol.18,No.4(2024)

The most prominent roles played by schoolchildren in bullying and cyberbullying situations are those of aggressors, victims, and bystanders. These roles are characterised by differences in the school environment and their achievements. This study aimed to analyse the differences between the roles of those directly involved in bullying and cyberbullying (aggressors, victims, and bystanders) by examining their attitudes and interest in reading. Participants were 326 primary schoolchildren in Murcia, Spain (M = 8.98, SD = 0.84), of whom 53.1% were girls. A multimodal questionnaire on school interaction was used with an instrument on attitudes and reading interests. A latent profile analysis (LPA) was conducted and showed three profiles: a) low levels of aggressiveness and victimisation, b) high indices of aggressiveness, and c) high indices of victimisation. The results revealed differences in attitudes toward and interest in reading among the various profiles. The findings of the study can help customise educational programs by providing bullying and cyberbullying intervention and prevention methods based on the roles of victims, aggressors, and bystanders and their attitudes toward and interests in reading.

bullying; cyberbullying; reading attitudes; reading interest; primary school students

Inmaculada Méndez

Department of Evolutionary and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain

Inmaculada Méndez holds a degree and a PhD in Psychology from the Universidad de Murcia. She works as Professor at this university. Her research areas include: social and health risk behaviours in childhood, adolescence and youth (drug consumption, bullying, etc.), as well as active and healthy ageing.

Irma Elizabeth Rojas Gómez

University Center, Cartagena, Murcia, Spain

Irma Elizabeth Rojas Gómez has PhD in Education from the University of Murcia. She works as a Professor at ISEN Center attached to the University of Murcia as a teacher in the area of language and literature didactics. She has investigated bullying and its relationship with language difficulties.

Cecilia Ruiz-Esteban

Department of Evolutionary and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain

Cecilia Ruiz -Esteban holds a degree in Educational Sciences from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, a Master of Science in Education from Bucknell University and a PhD in Psychology from the Universidad de Murcia. She works as a Lecturer at this university and as Lead Researcher in the EIPSED Research Group (Research Team in Educational Psychology) of the Universidad de Murcia. Her main areas of research deal with bullying and cyberbullying among peers, personal variables in the teaching-learning process and the quality of higher education.

María Dolores Delgado

University Center, Cartagena, Murcia, Spain

María Dolores Delgado has PhD in Education from the University of Murcia. She works like Professor at ISEN Center attached to the University of Murcia as a teacher in the area of language and literature didactics. She has researched reading in schoolchildren and the prevention of bullying.

José Manuel García-Fernández

Department of Developmental Psychology and Didactics, University of Alicante, Alicante, Spain

José Manuel García -Fernández is Professor at the University of Alicante. He has PhD in Psychology. He works on bullying and cyberbullying, digital skills, school anxiety, among other psychoeducational variables.

Alonso, C., & Romero, E. (2020). Estudio longitudinal de predictores y consecuencias del ciberacoso en adolescentes españoles [Longitudinal study of predictors and consequences of cyberbullying in Spanish adolescents]. Behavioral Psychology, 28(1), 73–93. https://www.behavioralpsycho.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/05.Alonso_28-1-1.pdf

ANAR Foundation, & Mutua Madrileña Foundation. (2022). La opinión de los estudiantes. III informe de prevención del acoso escolar en centros educativos en tiempos de pandemia 2020 y 2021 The opinion of the students [III report on prevention of bullying in educational centers in times of pandemic 2020 and 2021]. https://www.anar.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/INFORME_II_ESTUDIO_acoso-escolar-opinio%CC%81n-estudiantes.pdf

ANAR Foundation, & Mutua Madrileña Foundation (2023). La opinión de los/as estudiantes. V Informe de Prevención del Acoso Escolar en Centros Educativos [The opinion of the students. V Report on Prevention of Bullying in Educational Centers]. https://www.anar.org/anar-y-mutua-madrilena-presentan-el-v-informe-la-opinion-de-los-estudiantes-sobre-acoso-escolar

Artola, T., Sastre, S., & Alvarado, J. M. (2018). Evaluación de las actitudes e intereses hacia la lectura: validación de un instrumento para lectores principantes [Assessing reading attitudes and interests towards reading: Validation of an instrument for beginning readers]. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 11(2), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.30552/ejep.v11i2.227

Ballesteros, B., de Viñaspre, S. P., Díaz, D., & Toledano, E. (2018). III estudio sobre acoso escolar y ciberbullying según los afectados [III study on school bullying and cyberbullying according to those affected by it]. Mutua Madrileña Foundation, & ANAR Foundation. https://www.observatoriodelainfancia.es/oia/esp/descargar.aspx?id=5621&tipo=documento

Bartau-Rojas, I., Aierbe-Barandiaran, A., & Oregui-González, E. (2018). Parental mediation of the internet use of primary students: Beliefs, strategies and difficulties. Comunicar, 54, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.3916/C54-2018-07

Blewitt, C., O’Connor, A., Morris, H., Nolan, A., Mousa, A., Green, R., Ifanti, A., Jackson, K., & Skouteris, H. (2021). It’s embedded in what we do for every child: A qualitative exploration of early childhood educators’ perspectives on supporting children’s social and emotional learning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), Article 1530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041530

Botello, H. A. (2016). Efecto del acoso escolar en el desempeño lector en Colombia [Effect of bullying on the reading performance in Colombia]. Zona Próxima, 24, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.14482/zp.24.8728

Caballo, V. E., Calderero, M., Arias, B., Salazar, I. C., & Irurtia, M. J. (2012). Desarrollo validación de una nueva medida de autoinforme para evaluar el acoso escolar [Development and validation of a new self-report measure to assess bullying]. Behavioral Psychology, 20(3), 625–647. https://www.behavioralpsycho.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/08.Caballo_20-3oa.pdf

Caputo, A. (2014). Psychological correlates of school bullying victimization: Academic self-concept, learning motivation and test anxiety. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 3(1), 69–99. https://doi.org/10.4471/ijep.2014.04

Cañas, E., Estevez, E., & Estevez, J. F. (2022). Sociometric status in bullying perpetrators: A systematic review. Frontiers in Communication, 7, Article 841424. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.841424

Cañas, E., Estévez, E., Marzo, J. C., & Piqueras, J. A. (2019). Ajuste psicológico en cibervíctimas y ciberagresores en educación secundaria [Psychological adjustment in cybervictims and cyberbullies in secondary education]. Anales de Psicología, 35(3), 434–443. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.35.3.323151

Casas, J. A., Del Rey, R., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2013). Bullying and cyberbullying: Convergent and divergent predictor variables. Computer in Human Behavior, 29(3), 580–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.015

Cerezo, F., & Méndez, I. (2012). Conductas de riesgo social y de salud en adolescentes. Propuesta de intervención contextualizada para un caso de bullying [Social and health risk behaviours in adolescents. Context intervention proposal for a bullying case]. Anales de Psicología, 28(3), 705–719. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.28.3.156001

Clark, K. N., Eldridge, M. A., Dorio, N. B., Demaray, M. K., & Smith, T. J. (2022). Bullying, victimization, and bystander behavior: Risk factors across elementary–middle school transition. School Psychology, 37(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000477

Cocco, V. M., Bisagno, E., Visintin, E. P., Cadamuro, A., Di Bernardo, G. A., Shamloo, S. E., Trifiletti, E., Molinari, L., & Vezzali, L. (2023). Once upon a time...: Using fairy tales as a form of vicarious contact to prevent stigma-based bullying among schoolchildren. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 33(2), 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2597

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Correa, M. (2009). El cuento, la lectura y la convivencia como valor fundamental en la educación inicial [The story, reading and coexistence as a fundamental value in early education]. Educere, 13(44), 89–98. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/356/35614571011.pdf

Cuperman, R. (2010). Las repuestas lectoras en niños preadolescentes: espejo de la agresión [Reading responses in preadolescent children: Mirror of aggression]. Bellaterra Journal of Teaching & Learning Language & Literature, 2(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/jtl3.124

De Vicente-Yagüe, M. I., & González Romero, M. (2019). Análisis del panorama metodológico interdisciplinar en educación infantil para el fomento de la lectura [Analysis of the interdisciplinary methodological panorama in early childhood education for the promotion of reading]. Revista Complutense de Educación, 30(2), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.5209/RCED.57738

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1992). The initiation and regulation of intrinsically motivated learning and achievement. In A. K. Boggiano & T. S. Pittman (Eds.), Achievement and motivation: A social-developmental perspective (pp. 9–36). Cambridge University Press.

Del Moral, C., & Sanjuán, C. C. (2019). Violencia viral. Análisis de la violencia contra la infancia y la adolescencia en el entorno digital Viral violence [Analysis of violence against children and adolescents in the digital environment]. Save the Children. https://www.savethechildren.es/sites/default/files/imce/docs/informe_violencia_viral_1.pdf

Dezcallar Sáez, T., Clariana, M., Cladellas, R., Badia, M., & Gotzens, C. (2014). La lectura por placer: Su incidencia en el rendimiento académico, las horas de televisión y las horas de videojuegos [Reading for pleasure: Its impact on academic performance, hours of television and hours of video games]. Ocnos, 12, 107–116. https://doi.org/10.18239/ocnos_2014.12.05

Díaz-Aguado, M. J., Martínez, R., & Martín, J. (2013). El acoso entre adolescentes en España. Prevalencia, papeles adoptados por todo el grupo y características a las que atribuyen la victimización [Bullying among adolescents in Spain. Prevalence, participants’ roles and characteristics attributable to victimization by victims and aggressors]. Revista de Educación, 362, 348–379. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2011-362-164

Estévez, E., Estévez, J. F., Segura, L., & Suárez, C. (2019). The influence of bullying and cyberbullying in the psychological adjustment of victims and aggressors in adolescence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(12), Article 2080. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122080

Fisher, B. W., Mowen, T. J., & Boman, J. H. (2018). School security measures and longitudinal trends in adolescents’ experiences of victimization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(6), 1221–1237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0818-5

Gaffney, H., Farrington, D. P., Espelage, D. L., & Ttofi, M. M. (2019). Are cyberbullying intervention and prevention programs effective? A systematic and meta-analytical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 134–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.002

Gaffney, H., Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of school-bullying prevention programs: An updated meta-analytical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.001

Gallagher, K. (2009). Readicide: How schools are killing reading and what you can do about it. Stenhouse.

Garaigordobil, M., & Machimbarrena, J. M. (2019). Victimization and perpetration of bullying/cyberbullying: Connections with emotional and behavioral problems and childhood stress. Psychosocial Intervention, 28(2), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a3

Garaigordobil, M., & Martínez-Valderrey, V. (2018). Technological resources to prevent cyberbullying during adolescence: The Cyberprogram 2.0 Program and the Co-operative Cybereduca 2.0 videogame. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 745. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00745

García-Fernández, C. M., Romera-Félix, E. M., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2015). Explicative factors of face-to-face harassment and cyberbullying in a sample of primary students. Psicothema, 27(4), 347–353. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2015.35

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Hymel, S. (2014). Moral disengagement among children and youth: A meta-analytic review of links to aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 40(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21502

Gutiérrez Ángel, N. (2018). Análisis bibliográfico de las características y consecuencias de los roles desempeñados en la violencia escolar: Agresores, víctimas y observadores [Bibliographic analysis of the characteristics and consequences of the roles played in school violence: Aggressors, victims and observers]. Apuntes de Psicología, 36(3), 181–189. https://www.apuntesdepsicologia.es/index.php/revista/article/view/749

Guy, A., Lee, K., & Wolke, D. (2019). Comparisons between adolescent bullies, victims, and bully-victims on perceived popularity, social impact, and social preference. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, Article 868. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00868

Hoster, B. (2007). Selección temática de álbumes ilustrados para una educación en la no violencia [Thematic selection of picture books for non-violence education]. Escuela Abierta, 10, 101–127. https://ea.ceuandalucia.es/index.php/EA/article/view/100

Huang, L. (2022). Exploring the relationship between school bullying and academic performance: The mediating role of students’ sense of belonging at school. Educational Studies, 48(2), 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2020.1749032

Instituto Nacional de Evaluación Educativa (INEE). (2020). Programa para la evaluación internacional de los estudiantes. Resultados de lectura en España [PISA 2018. Program for International Student Assessment. Reading scores in Spain]. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/inee/portada.html

Instituto Nacional de Evaluación Educativa (INEE). (2023). Programa para la evaluación internacional de los estudiantes. Informe español PISA 2022. [Program for International Student Assessment. Spanish report PISA 2022]. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/inee/portada.html

Íñiguez-Berrozpe, T., Cano-Escoriaza, J., Elboj-Saso, C., & Cortés-Pascual, A. (2020). Modelo estructural de concurrencia entre bullying y cyberbullying: Víctimas, agresores y espectadores [Structural model of concurrence among relational bullying and cyberbullying: Victims, aggressors and bystanders]. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 171, 63–84. http://dx.doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.171.63

Jiménez, R. (2019). Multiple victimization (traditional bullying and cyberbullying) in primary education in Spain and associated school variables from a gender perspective. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 9(2), 169–192. https://doi.org/10.17583/remie.2019.4272

John, A., Glendenning, A. C., Marchant, A., Montgomery, P., Stewart, A., Wood, S., Lloyd, K., & Hawton, K. (2018). Self-harm, suicidal behaviours, and cyberbullying in children and young people: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(4), Article e129. https://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9044

Juvonen, J., Wang, Y., & Espinoza, G. (2010). Bullying experiences and compromised academic performance across middle school grades. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 31(1), 152–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431610379415

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., & Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073–1137. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035618

Laninga-Wijnen, L., van den Berg, Y. H., Mainhard, T., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2021). The role of defending norms in victims’ classroom climate perceptions and psychosocial maladjustment in secondary school. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49(2), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00738-0

Larrañaga, E., Acosta, M., & Yubero, S. (2015). Leer para convivir. Lecturas para la prevención del acoso [Reading to live together. Readings for bullying prevention]. Educació Social, 59, 71–85. https://raco.cat/index.php/EducacioSocial/article/view/290999/379335

Malecki, C. K., Demaray, M. K., Smith, T. J., & Emmons, J. (2020). Disability, poverty, and other risk factors associated with involvement in bullying behaviors. Journal of School Psychology, 78, 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.01.002.

Marín-Cortés, A., Franco-Bustamante, S., Betancur-Hoyos, E., & Vélez-Zapata, V. (2020). Miedo y tristeza en adolescentes espectadores de cyberbullying. Vulneración de la salud mental en la era digital [Fear and sadness in bystander adolescents of cyberbullying. Mental health violation in the digital age]. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica Del Norte, 61, 66–82. https://doi.org/10.35575/rvucn.n61a5

Martínez-Ferrer, B., Moreno, D., & Musitu, G. (2018). Are adolescents engaged in the problematic use of social networking sites more involved in peer aggression and victimization? Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 801. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00801

Megías, A., Gómez-Leal, R., Gutiérrez-Coboa, M. J., Cabello, R., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2018). The relationship between aggression and ability emotional intelligence: The role of negative affect. Psychiatry Research, 270, 1074–1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.027

Menéndez Santurio, J. I., Fernández-Río, J., Cecchini Estrada, J. A., & González-Víllora, S. (2021). Acoso escolar, necesidades psicológicas básicas, responsabilidad y satisfacción con la vida: Relaciones y perfiles en adolescentes [Bullying, basic psychological needs, responsibility and life satisfaction: Connections and profiles in adolescent]. Anales de Psicología, 37(1), 133–141. https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.37.1.414191

Merisuo-Storm, T., & Soininen, M. (2012). Constructing a research-based program to improve primary school students’ reading comprehension skills. International Journal for Cross-Disciplinary Subjects in Education (IJCDSE), 3(3), 755–762. https://doi.org/10.20533/ijcdse.2042.6364.2012.0108

Méndez, I., & Cerezo, F. (2018). La repetición escolar en educación secundaria y factores de riesgo asociados [Grade repetition in secondary education and associated risk factor]. Educación XX1, 21, 41–62. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/706/70653466003.pdf

Méndez, I., Jorquera Hernández, A. B., Ruiz-Esteban, C., Martínez, J. P., & Fernández-Sogorb, A. (2019). Emotional intelligence, bullying, and cyberbullying in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, Article 4837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234837

Méndez, I., Liccardi, G., & Ruiz-Esteban (2020). Mechanisms of moral disengagement used to justify school violence in sicilian primary school. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10, 682–691. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10030050

Merisuo-Storm, T., & Soininen, M. (2014). The interdependence between young students reading attitudes, reading skills, and self-esteem. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 4(2), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.5901/jesr.2014.v4n2p122

Molero, M. M., Martos, A., Barragán, A. B., Pérez-Fuentes, M. C., & Gázquez., J. J. (2022). Anxiety and depression from cybervictimization in adolescents: A metaanalysis and meta-regression study. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 14(1), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2022a5

Morgan, P. L., & Fuchs, D. (2007). Is there a bidirectional relationship between children’s reading skills and reading motivation? Exceptional Children, 73(2), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290707300203

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables. User’s guide (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

Nakamoto, J., & Schwartz, D. (2010). Is peer victimization associated with academic achievement? A meta-analytic review. Social Development, 19(2), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00539.x

Nunamaker, R. G. C., & Mosier, W. A. (2023). The relationship of classroom behavior and income inequality to literacy in early childhood. In Information Resources Management Association (Ed.), Research anthology on early childhood development and school transition in the digital era (pp. 698–726). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-7468-6.ch034

Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: Development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 751–780. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516

Olweus, D., & Limber, S. P. (2018). Some problems with cyberbullying research. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.012

Polanco-Levicán, K., & Salvo-Garrido, S. (2021). Bystander roles in cyberbullying: A mini-review of who, how many, and why. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 676787. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.676787

Pytash, K. E., Morgan, D. N., & Batchelor, K. E. (2013). Recognize the signs: Reading young adult literature to address bullying. Voices From the Middle, 20(3), 15–20. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/293482784_Recognizing_the_signs_Reading_young_adult_literature_to_address_bullying

Rezapour, M., Khanjani, N., & Mirzai, M. (2019). Exploring associations between school environment and bullying in Iran: Multilevel contextual effects modeling. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.01.036

Rodríguez-Álvarez, J. M., Navarro, R., & Yubero, S. (2022). Bullying/cyberbullying en quinto y sexto curso de educación primaria: Diferencias entre contextos rurales y urbanos [Bullying/cyberbullying in 5th and 6th year of primary education: Differences between rural and urban areas]. Psicología Educativa, 28(2), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2021a18

Rojas, I., Méndez, I., & Ruiz–Esteban, C. (2021). Dificultades lectoras y problemas de convivencia en el alumnado de educación primaria [Reading difficulties and coexistence problems in primary education students]. Psicologia.com, 25, 1–16. https://psiquiatria.com/bibliopsiquis/dificultades-lectoras-y-problemas-de-convivencia-en-el-alumnado-de-educacion-primaria

Saint-Georges, Z., & Vaillancourt, T. (2020). The temporal sequence of depressive symptoms, peer victimization, and self-esteem across adolescence: Evidence for an integrated self-perception driven model. Development and Psychopathology, 32(3), 975–984. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419000865

Saiz, M. J. S., Chacón, R. M. F., Garrido-Abejar, M., Parra, M. D. S., Laraña, E., & Yubero, S. (2019). Personal and social factors which protect against bullying victimization. Enfermería Global, 18(2), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.18.2.345931

Salvo-Garrido, S., Zayas-Castro, J., Polanco-Levicán, K., & Gálvez-Nieto, J. L. (2023). Latent regression analysis considering student, teacher, and parent variables and their relationship with academic performance in primary school students in Chile. Behavioral Sciences, 13(6), Article 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060516

Samara, M., Da Silva Nascimento, B., El-Asam, A., Hammuda, S., & Khattab, N. (2021). How can bullying victimisation lead to lower academic achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the mediating role of cognitive-motivational factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), Article 2209. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052209

Sastre, A., Calmaestra, J., Escorial, A., & García, P. (2016). Yo a eso no juego. Bullying y ciberbullying en la infancia [I don’t play that game. Bullying and cyberbullying in childhood]. Save the Children España. https://www.savethechildren.es/sites/default/files/imce/docs/yo_a_eso_no_juego.pdf

Turunen, T., Kiuru, N., Poskiparta, E., Niemi, P., & Nurmi, J.-E. (2019). Word reading skills and externalizing and internalizing problems from grade 1 to grade 2—Developmental trajectories and bullying involvement in grade 3. Scientific Studies of Reading, 23(2),161–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2018.1497036

Turunen, T., Poskiparta, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2017). Are reading difficulties associated with bullying involvement? Learning and Instruction, 52, 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.05.007

Turunen, T., Poskiparta, E., Salmivalli, C., Niemi, P., & Lerkkanen, M.-K. (2021). Longitudinal associations between poor reading skills, bullying and victimization across the transition from elementary to middle school. PLoS One, 16(3), Article e0249112. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249112

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2019). Behind the numbers: Ending school violence and bullying. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366483

Valderrama, M. A., & Rubio, F. J. (2018). Prevención del bullying a través del aprendizaje de la lectoescritura en Educación Primaria [Prevention of bullying through literacy learning in primary education]. IKASTORRATZA. e-Revista de Didáctica, 21, 22–58. http://www.ehu.es/ikastorratza/21_alea/2.pdf

Valle, A., González-Cabanach, R., & Rodríguez-Martínez, S. (2006). Reflexiones sobre la motivación y el aprendizaje a partir de la Ley Orgánica de Educación (LOE): “Del dicho al hecho…”.[Reflecting on motivation and learning in the new Spanish Education Act (LOE): Talking vs. doing]. Papeles del Psicólogo, 27(3), 135–138. https://www.papelesdelpsicologo.es/pdf/1370.pdf

Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09818-1

Walrave, M., & Heirman, W. (2011). Cyberbullying: Predicting victimisation and perpetration. Children & Society, 25(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2009.00260.x

Wee, S.-J., Kim, S. J., Chung, K., & Kim, M. (2022). Development of children’s perspective-taking and empathy through bullying-themed books and role-playing. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 36(1), 96–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2020.1864523

Young-Jones, A., Fursa, S., Byrket, J. S., & Sly, J. S. (2014). Bullying affects more than feelings: The long-term implications of victimization on academic motivation in higher education. Social Psychology of Education, 18(1), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9287-1

Yubero, S., & Larrañaga, E. (2010). El valor de la lectura en relación con el comportamiento lector. Un estudio sobre los hábitos lectores y el estilo de vida en niños [The value of reading in relation to reading behavior. A study on reading habits and lifestyle in children]. Ocnos, 6, 7–20. https://doi.org/10.18239/ocnos_2010.06.01

Yubero, S., & Larrañaga, E. (2014). Textos literarios para la prevención del acoso [Literary texts for bullying prevention]. INFAD Revista de Psicología, 5(1), 313–318. https://doi.org/10.17060/ijodaep.2014.n1.v5.688

Authors’ Contribution

Inmaculada Méndez: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision. Irma Elizabeth Rojas Gómez: conceptualization, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision. Cecilia Ruiz-Esteban: investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision. María Dolores Delgado: data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision. José Manuel García-Fernández: methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

November 18, 2022

Revisions received:

April 5, 2023

October 16, 2023

January 11, 2024

May 13, 2024

Accepted for publication:

July 10, 2024

Editor in charge:

Fabio Sticca

Introduction

Bullying refers to aggressive, intentional, and persistent behaviour exhibited by an individual or group against a person who cannot easily defend themselves. It is considered an asymmetric relationship because there is an imbalance of forces; the victim cannot protect himself (Olweus, 2013; Olweus & Limber, 2018). These situations often manifest as verbal, physical, and material violence; sexual aggression; and cyberbullying (Sastre, 2016). Cyberbullying involves using Information and Communication Technologies (internet, cell phone, etc.) intentionally and over a prolonged period to ridicule, humiliate, or discredit the victim through comments, rumours, images, videos, etc. (Cañas et al., 2019; Íñiguez-Berrozpe et al., 2020). Similar to traditional bullying, cyberbullying is characterised by premeditated and intentional behaviours that occur repetitively and continuously over time (Garaigordobil & Martínez-Valderrey, 2018). However, cyberbullying also differs from traditional bullying in specific ways, such as the anonymity of the bully, the difficulty of moving away from the virtual environment, the possibility of reaching a larger audience, the impunity of the aggressor, and the concealment of the aggressor’s identity (Casas et al., 2013; Íñiguez-Berrozpe et al., 2020; Martínez-Ferrer et al., 2018; Molero et al., 2022). Online violence is related to real-life violence (offline), and several types of violence may occur successively or simultaneously online and in real life (Del Moral & Sanjuán, 2019). Existing studies on primary education show that, in the educational stage, students are often involved in bullying and cyberbullying (Jiménez et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Álvarez et al., 2022). A strong relationship was found between being an aggressor in bullying and cyberbullying, as well as in the case of the victim, in both media, being higher in the case of bullying than in cyberbullying (García-Fernández et al., 2015). Notably, online and offline violence may be interrelated (Kowalski et al., 2014). As the roles of victim and aggressor are becoming increasingly blurred in cyberspace, victims of bullying can become the aggressors of cyberbullying, and vice versa (Del Moral & Sanjuán, 2019; Walrave & Heirman, 2011). Thus, violence experienced by minors increases the likelihood of them exercising violence on others. Specifically, it was found that victims who suffered from violence online have the need to exert violence in the same environment or others (Gutiérrez Ángel, 2019). Both bullying and cyberbullying have repercussions that can lead to psychological problems (e.g., depression, fear, anxiety), which affect 94% of offline victims and 88.5% of cyber victims (Ballesteros et al., 2018). The effects on victims lead to various health problems, such as anxiety symptoms, phobias or fears related to school, sleep problems, headaches, stomach pains, depressive symptoms, and suicide attempts. (Alonso & Romero, 2020; Gutiérrez Ángel, 2019). Meanwhile, aggressors may struggle with adjusting to social situations, engage in disruptive behaviour, and consume legal and illegal drugs, among other issues (Alonso & Romero, 2020; Cerezo & Méndez, 2012; Gutiérrez Ángel, 2019). The prolonged role of bystanders in bullying over time leads to a loss of empathy, internalisation of antisocial behaviours, and desensitisation, which can provoke feelings of guilt in some cases (Bartau-Rojas et al., 2018; John et al., 2018; Laninga-Wijnen et al., 2021; Olweus & Limber, 2018; Polanco-Levicán & Salvo-Garrido, 2021). It also affects their emotional well-being, as it causes fear, feelings of submission, hopelessness, and even sadness (Gutiérrez Ángel, 2019; Martín-Cortés et al., 2020).

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO, 2019) has declared bullying and cyberbullying global problems. A total of 32% of schoolchildren worldwide have been victims of some form of bullying by their peers on one or more occasions in the last month. The report by UNESCO, which comprises World Health Survey data from 144 countries, stated that the prevalence of bullying ranged from 7.1 to 74%. A total of 25% of schoolchildren in Europe have suffered from bullying, while 15.4% have been victims in Spain (UNESCO, 2019). Similarly, Save the Children in Spain (Del Moral & Sanjuán, 2019) reported that 39.65% of schoolchildren had suffered cyberbullying at least once, and 27.43% experienced cyberbullying one to two times in their lives. During the COVID-19 pandemic, an increase in cases of cyberbullying on social networks was observed, mainly consisting of group attacks; two or more aggressors participated in 72.4% of cyberbullying cases (ANAR Foundation & Mutua Madrileña Foundation, 2022). The recent 2023 report showed a slight decrease in the data compared to previous years. Nonetheless, it should be noted that 11.8% considered that someone in their class was a victim of bullying, and 7.4% considered that someone in their class was a victim of cyberbullying. A total of 90.8% of students identified their classmates as cyberbullying harassers, with 53.6% from the same class and 37.2% from other classes or courses. Furthermore, 23.3% admitted having experienced bullying or cyberbullying. According to teachers in Spain, approximately 9.6% of cases of bullying and cyberbullying at school remain unresolved (ANAR Foundation & Mutua Madrileña Foundation, 2023).

Various authors have stated that the aggressor, victim, and bystander are among the roles played by schoolchildren directly involved in bullying and cyberbullying (Gutiérrez Ángel, 2019). Each role is exemplified by its defining characteristics, as summarised below.

First, aggressors and cyber-aggressors usually have difficulties regulating and managing their emotions (Estévez et al., 2019; Megías et al., 2018; Méndez et al., 2019), lack social communication skills and assertiveness, and cannot relate to their peers (Cañas et al., 2022; Del Moral & Sanjuán, 2019; Guy et al., 2019). They also exhibit negative attitudes towards school and learning (Nunamaker & Mosier, 2023), have high school absenteeism and poor performance, and tend to refuse to attend school (Bartau-Rojas et al., 2018; Laninga-Wijnen et al., 2021; Olweus & Limber, 2018; Saiz et al., 2019). Furthermore, many tend to repeat an academic year (Méndez & Cerezo, 2018), which implies low motivation towards academic tasks, especially towards reading, including the time dedicated to it and its use (Botello, 2016; Rojas et al., 2021; Turunen et al., 2019, 2017, 2021).

Second, victims are unable to defend themselves from aggressors’ actions since they are usually in an imbalanced power situation (Olweus, 2013). They typically exhibit passive behaviour when faced with intimidation by an aggressor (Díaz-Aguado et al., 2013) and are usually discriminated against for reasons or distinctions such as sex, religion, origin, or disability (Clark et al., 2022; Malecki et al., 2020). Schoolchildren who present a victim or cyber victim profile tend to have low self-esteem (Saint-Georges & Vaillancourt, 2020) and academic self-concept (Caputo, 2014); communication difficulties; low assertiveness; feelings of fear, guilt, and anxiety (Bartau-Rojas et al., 2018; Garaigordobil & Machimbarrena, 2019; John et al., 2018; Laninga-Wijnen et al., 2021; Molero et al., 2022; Saiz et al., 2019); and insecurities (Fisher et al., 2018; Rezapour et al., 2019). They are likely to have difficulties with school performance (Juvonen et al., 2010; Nakamoto & Schwartz, 2010; Samara et al., 2021) due to lack of school (Samara et al., 2021; Young-Jones et al., 2014) and extrinsic motivation (Caputo, 2014). Additionally, a significant negative relationship was found between victims and performance in science, mathematics, and reading (Huang, 2022; Salvo-Garrido et al., 2023).

Finally, the bystanders are those who play various roles in both bullying and cyberbullying, as, in some way, they are aware of the problems among students (Caballo et al., 2012; Gutiérrez Ángel, 2019; Polanco-Levicán & Salvo-Garrido, 2021). They may play a more or less active role depending on whether they show supportive attitudes towards the aggressor or defend the victim (Bartau-Rojas et al., 2018; John et al., 2018; Laninga-Wijnen et al., 2021; Olweus & Limber, 2018). If they identify more with the aggressor, they may present mechanisms of moral disconnection and may not intervene in intimidation situations in the victim’s defence (Gini et al., 2014; Méndez et al., 2020). Only some bystanders actively intervene in bullying and cyberbullying situations, while others ignore and do not report aggressors or support victims (Caballo et al., 2012; Méndez et al., 2020).

Bullying, Cyberbullying, and Interest in Reading

Among the existing perspectives on motivation, self-determination theory stands out; it is a continuum ranging from self-determination to lack of control (Deci & Ryan, 1992). Hence, students have control over their learning and can determine the autonomy exercised at each moment. The six sub-theories that make up this theory has allowed to it to expand continually (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). Among these sub-theories, the theory of Basic Psychological Needs is the most important. Individuals have three innate and universal needs: the degree of effectiveness in a given context, the degree of autonomy and control, and the degree of relationships, which refers to the feeling of belonging to a group. Their satisfaction is associated with high levels of self-determined motivation. However, low levels can be dangerous for an individual’s behaviour, as they can lead to bullying or cyberbullying (Menéndez Santurio et al., 2021).

The data were obtained from the Program for International Student Assessment in Spain. Reading scores in the Spain-PISA-2018 report (INEE, 2020) indicate that reading performance is lower than the average of the European Union, which has been maintained in the 2022 PISA report (INEE, 2023). In the PISA 2018 report (INEE, 2020), an indicator allows us to assess whether a student has suffered any harassment. This indicator reflects students’ experiences of a series of bullying situations. Thus, the values showed that schoolchildren who were mostly exposed to bullying situations were negatively associated with school performance, specifically reading. Therefore, the rate of exposure to bullying is correlated with poor reading performance. An analysis of this indicator reveals that, on average, among the countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 7% of the variance in reading performance is explained by this factor. This is only one percentage point higher than in the European Union, where the same percentage of explained variance in Spain is 6%. Similarly, feelings of being accepted, respected, and supported at school were positively associated with academic performance. Furthermore, a strong relationship between academic performance and the enjoyment of reading were found (Botello, 2016; Dezcallar Sáez et al., 2014; INEE, 2020). Reading interest and motivation can promote better attitudes towards studying (Artola et al., 2018; Merisuo-Storm & Soininen, 2014; Morgan et al., 2007). However, compulsory reading usually causes students to reject reading and have less motivation (Yubero & Larrañaga, 2010), leading to school problems.

Despite these findings, only a few studies have analysed how different levels of interest in reading are associated with involvement in bullying and cyberbullying (Botello, 2016; Rojas et al., 2021; Turunen et al., 2019, 2017, 2021). According to Turunen at al. (2019, 2021), victims tend to have decreased reading performance, although temporary. Meanwhile, Botello (2016) stated that having books at home, parental supervision of schoolwork, and parents who dedicate time to reading positively impact students’ performance and book use, especially for victims. However, in the case of the aggressor, they often have low motivation towards academic tasks, especially regarding reading, indcluding the time dedicated for it and its use (Botello, 2016; Rojas et al., 2021; Turunen et al., 2019, 2017, 2021). A previous study also confirmed that a lack of fluency and reading comprehension predict involvement in bullying and cyberbullying as aggressors (Turunen et al., 2021).

Surprisingly, students with higher reading skills and who did not present reading difficulties participated more in the role of active bystanders (Rojas et al., 2021). Additionally, those who feel safe and happy and have good relationships with their peers enjoy studying (Merisuo-Storm & Soininen, 2014). These students do not usually become involved in the aggressor-victim dyad (Blewitt et al., 2021; Turunen et al., 2021).

Therefore, it is necessary to examine the value of reading (reading attitudes and interests) among schoolchildren who are directly involved in bullying and cyberbullying. The main objective of this study was to identify schoolchildren’s profiles according to their levels of aggressiveness and victimisation in bullying and cyberbullying. We also examined whether schoolchildren with different profiles of aggression and victimisation have different reading values (reading attitudes and interests). The main hypotheses of the study were as follows: 1) the combinations of aggressiveness and victimisation among schoolchildren result in different profiles of bullying and cyberbullying (aggressor, victim, and bystander); and 2) schoolchildren directly involved in the bullying and cyberbullying dyad as aggressors and victims would present lower reading attitudes and interests compared to bystanders.

Methods

Participants

The participants were 326 students in the second cycle of primary education (3rd and 4th grade) from five different educational centres in the region of Murcia in the Southeast of Spain, aged 8–10 years old (M = 8.98, SD = 0.84); 53.1% were girls. The distribution was homogeneous regarding sex and years (χ2 = 3.72, p = .156; see Table 1), and the socioeconomic levels of the students from different geographic areas and educational centres in the study were average. Regarding the level of education of the parents, we found the following distribution: primary studies (9% of fathers and 11.3% of mothers), secondary studies on vocational training or high school (26.4 % of fathers and 23.5% of mothers), and university studies (17.2% of fathers and 12.1% of mothers). This was a representative sample of second-cycle primary school students with a confidence level of 90% and a margin of error of 5%.

Table 1. Sample Distribution According to Age and Sex.

|

Variables |

Age |

8 years |

9 years |

10 years |

|

Sex |

Boys |

54 (16.6%) |

52 (16%) |

47 (14.4%) |

|

Girls |

61 (18.7%) |

44 (13.5%) |

68 (20.9%) |

Instruments

First, a multimodal school interaction questionnaire (Caballo et al., 2012) was used to collect information on the frequency of students’ experiences of bullying and cyberbullying since the beginning of their school year. The questionnaire comprised 36 items ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (many times). It assessed the following dimensions.

Intimidating behaviours (aggressor role) refer to the typical behaviours exercised by the harasser in the different manifestations of harassment and the behaviours that justify them (α = .75; an example of items: e.g., I have messed with a classmate; insulting, criticising, calling names, etc.).

Victimisation received (victim role) refers to situations of intimidation and harassment experienced by the victims (e.g., I have been insulted).

Extreme victim or cyberbullying (the role of the victim in extreme situations such as cyberbullying) refers to more extreme victimisation situations than the victimisation factor received since it includes conditions with more extreme harassment that are less manageable and difficult for the victim to control. Similarly, it integrates cyberbullying situations (α = .76; an example of items: e.g., They have messed with me through the phone; calls or messages).

Active bystander (bystander in defence of bullied students) refers to situations where an observant student acts in defence of the student who is harassed (α = .76; an example of items: e.g., I get involved to stop the situation if they are doing physical harm to a classmate).

Passive bystander (bystander who does not act in bullying situations in defence of the bullied) refers to situations where the student does not respond to scenarios where they see a classmate being harassed (α = .72; an example of items: e.g., If someone is threatened, I stay still without doing anything or leave).

Cronbach’s alpha reliability values were high (α = .81), both in the original scale (Caballo et al., 2012) and in our study (α = .81). The instrument also collects information on sociodemographic characteristics (sex, grade, and age) and provides information on the places where bullying occurs.

Second, we used the scale of reading attitudes and interests developed by Meirisuo-Storm and Soininen (2012) and created a Spanish version, which was validated by Artola et al. (2018). This scale comprises 26 items rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (I love it or find it easy) to 4 (I hate it or find it very difficult). The higher the score, the lower the reading attitude and interest level. This study used the following questionnaire dimensions.

Motivation towards reading is the motivation with which the student tackles reading, including having an interest in reading, enjoying reading adventure books, and having fun doing academic homework (α = .73; an example of items: e.g., Do you like to read books?).

Reading interests refer to the reading interests that attract the student to read, such as liking story books, reading at home in your free time, and going to the library, among others (α = .78; an example of items: e.g., Do you like to read at home in your free time?).

Attitudes towards the study pertain to the attitudes presented by students, which include easy understanding of the books read at school and remembering and knowing what was read at school, among others (α = .77; an example of items: e.g., Is it easy for you to understand the books you read at school?).

Attitudes towards social or collective reading are the attitudes shown by students regarding social or collective reading, such as enjoying reading to other classmates, doing class work and activities with other classmates, and telling other classmates about the book they are reading (α = .70; an example of items: e.g., Do you like doing class work and activities with a classmate?).

The test shows that the adequate Cronbach’s alpha reliability values (α = .89) have similar values in our study (α = .79).

Procedure

Authorisation to collect data was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia (ID: 2415/2019). Once authorisation was received, the educational centres in the region of Murcia were chosen for convenience, given the availability of the schools participating in the study, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the total number of centres, we invited to participate in the study, we were able to collect information from five centres (2019–2020 academic school calendar). Therefore, this was a cross-sectional study that used convenience sampling.

First, we interviewed the management or guidance teams to request collaboration and access to educational centres. Following their approval, we asked for informed consent from parents and minors. A total of 62 participants were excluded from the study due to a lack of consent and incomplete or poorly completed instruments. The instruments mentioned in the previous section were administered in a 50–60-minute session in the presence of a researcher to clarify possible doubts. The students’ contributions were anonymous and voluntary, and confidentiality was maintained throughout the process.

Data Analysis

A latent profile analysis (LPA) was employed to explore combinations of aggression and victimisation among schoolchildren using the multimodal school interaction questionnaire. This questionnaire collected information on the frequency of students’ experiences in bullying and cyberbullying (Caballo et al., 2012). Information on the student subgroups based on their roles in bullying and cyberbullying allowed us to identify how the participants were grouped precisely. The following criteria were used to define the number of classes that adequately fit the data: the lowest values in the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC);

p-values < .05, associated with the Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) and the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood-Ratio Test (LRT); and entropy values close to 1. Similarly, solutions that included small classes (< 25 classified cases) were not considered to obtain a significant class classification. Following the theory of psychological viability, which includes the evidence of the theoretical framework and the levels of aggression and victimisation of the instrument, the psychological meaning was adjusted for each subgroup. The results revealed that it was possible to obtain information from three clearly differentiated profiles depending on the instrument: a) a group with low values of aggressiveness and victimisation (unifying the dimensions of a passive and active bystander); b) a group with high values of aggressiveness (intimidator dimension); and c) a group with high values of victimisation (combining the dimensions of victim and cyberbullying).

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to examine the differences among the groups’ reading attitudes and interests. In the post hoc analysis, the Bonferroni method was employed. The partial eta squared value (ηp2) and Cohen’s d (1998) were estimated to determine the differences’ magnitude. We used SPSS Windows software version 24.0 and MPlus version 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012).

Results

Table 2 lists the models used in this study. The models had two to six clusters, but the three-cluster model was selected because it was the model for which the LRT turned out to be significant, and each cluster had over 25 participants.

Table 2. Fit of All Latent Class Models.

|

Models |

AIC |

BIC |

BIC-adjusted |

LRT |

LRT-adjusted |

Entropy |

Size |

|

2 |

1780.464 |

1806.973 |

1784.769 |

.0042 |

.0054 |

.772 |

0 |

|

3 |

1734.340 |

1772.209 |

1740.490 |

.0105 |

.0129 |

.807 |

0 |

|

4 |

1704.966 |

1754.196 |

1712.961 |

.1240 |

.1344 |

.820 |

1 |

|

5 |

1710.966 |

1771.557 |

1720.806 |

.3516 |

.3584 |

.690 |

1 |

|

6 |

1677.977 |

1749.928 |

1689.661 |

.7006 |

.6948 |

.886 |

2 |

|

Note. AIC, Akaike Information Criterion; BIC, Bayesian Information Criterion; LRT, Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood-ratio test, Size: number of clusters with less than 25 subjects. Values in italics show the selected model. |

|||||||

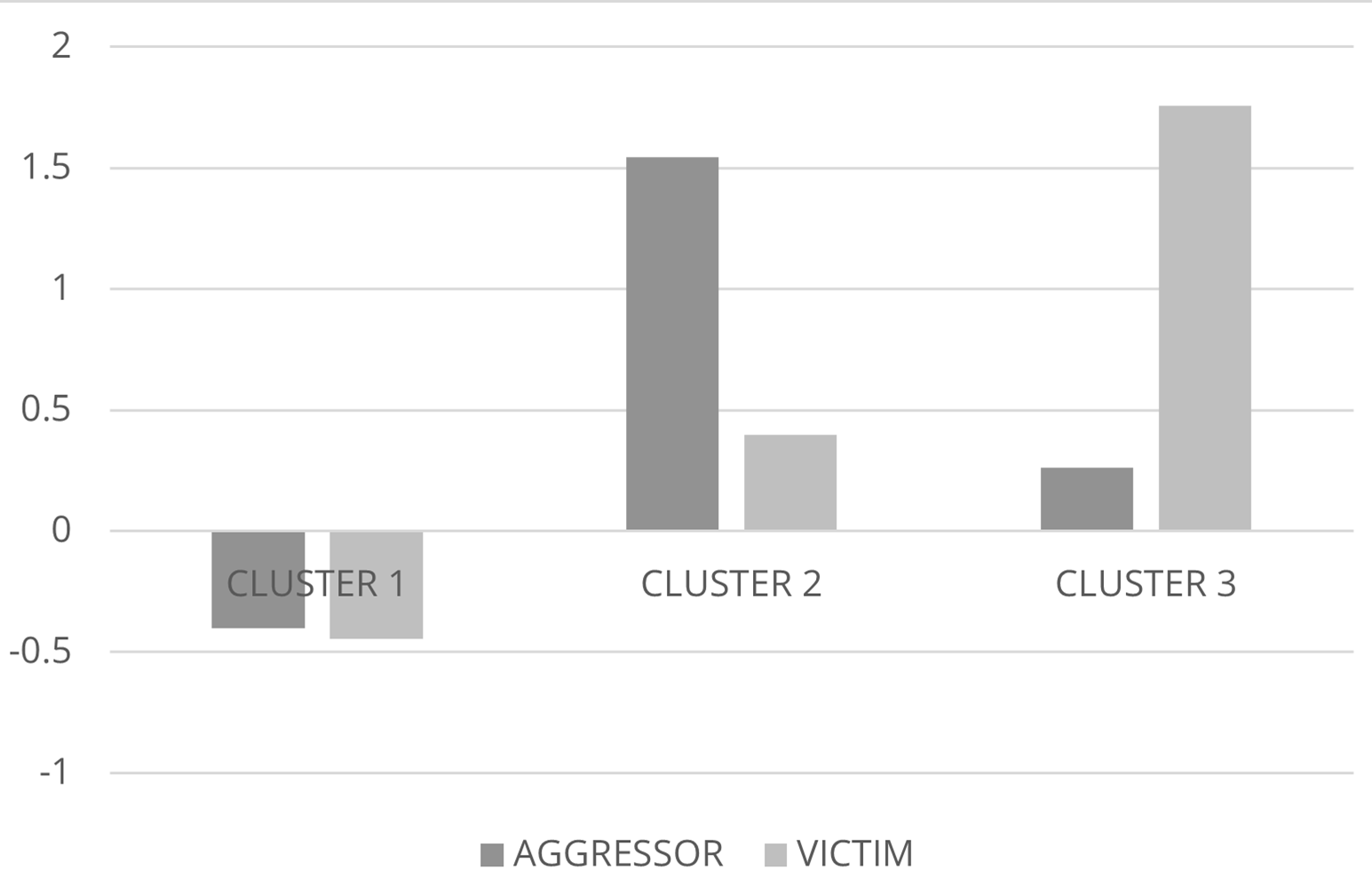

Figure 1 shows the three profiles obtained from students involved in bullying and cyberbullying, based on the standardised mean scores for aggressiveness and victimisation, which are detailed below. The first group included 234 students (71.8% of the participants) with low levels of aggressive and victimised behaviours and could be considered bystanders (unifying the dimensions of passive and active bystanders). The second group included 48 students (14.7% of the participants) with aggressive behaviours and were considered aggressors. The third group included 44 students (13.5% of the participants) who presented high rates of victimisation and were considered victims.

These results allow us to support the proposed hypothesis since the combinations of aggression and victimisation among students have given rise to different profiles in bullying and cyberbullying (aggressor, victim, and bystander).

Figure 1. Graphical Representation of Standardized Mean Scores of the Three-Cluster Model.

The MANOVA comparisons between the groups are presented in Table 3. Cohen’s d indices for the post-hoc contrast group and significant differences are shown in Table 4.

Table 3. Means and Standard Deviations Obtained by the Three Groups of Bullying and Cyberbullying and

Values of the Partial Eta Squared (ηp2) for Each Dimension of Reading Attitudes and Interests.

|

|

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

Group 3 |

Significance |

|||||

|

Dimensions |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

F(2,323) |

p |

η2 |

|

Motivation toward reading |

7.82 |

2.18 |

8.72 |

2.67 |

8.18 |

2.80 |

3.05 |

.049 |

.02 |

|

Reading interests |

12.29 |

3.84 |

14.47 |

5.01 |

11.68 |

4.06 |

6.86 |

.001 |

.04 |

|

Attitudes toward the study |

8.00 |

2.43 |

8.31 |

2.36 |

9.45 |

2.72 |

6.47 |

.002 |

.04 |

|

Collective reading |

7.09 |

2.74 |

9.45 |

3.89 |

8.59 |

3.59 |

14.32 |

< .001 |

.08 |

|

Note. Cluster 1 (low levels of aggressive behavior and victimization); Cluster 2 (high rates of aggressiveness), and Cluster 3 (high rates of victimization). |

|||||||||

Table 4. Cohen’s d Indexes for Post Hoc Contrast Groups.

|

Dimensions |

Group1–Group 2 |

Group1–Group 3 |

Group 2–Group 3 |

|

Motivation toward reading |

−.40* |

n.s. |

n.s. |

|

Reading interests |

−.54** |

n.s. |

.61** |

|

Attitudes toward the study |

n.s |

−.59** |

n.s. |

|

Collective reading |

−.80*** |

−.52** |

n.s. |

|

Note. *p < .05, **p < .005, ***p < .001, n.s. = not significance. |

|||

First, the post-hoc contrasts indicated that the students in Group 1 (bystanders) presented greater motivation (i.e., lower values in the dimension of motivation towards reading) than those in Group 2 (bullies). The differences between Groups 1 and 3 and between Groups 2 and 3 were not significant.

Regarding reading interest, the post-hoc contrasts showed that the students in Group 1 (bystanders) have better values (i.e., lower values in the reading interest dimension) than those in Group 2 (aggressors). Meanwhile, students in Group 3 (victims) have more suitable values (i.e., lower values in the reading interests dimension) than those in Group 2 (aggressors). The differences between Groups 1 and 3 were not statistically significant.

In attitudes towards studying, the post hoc contrasts indicated that the students in Group 1 (bystanders) presented the most suitable values (lower values in the dimension attitudes towards studying) compared to Groups 2 (aggressors) and 3 (victims). No significant differences were found between Groups 2 and 3.

Finally, in the collective attitude dimension, post hoc contrasts showed that students in Group 1 (bystanders) presented better values (lowest values in the collective attitude dimension) than those in Group 3 (victims). The differences between Groups 1 and 2 and between Groups 2 and 3 were not significant.

The results support the hypothesis that schoolchildren directly involved in the dyad of bullying and cyberbullying as aggressors and victims presented lower attitudes and reading interests compared to bystanders.

Discussion

Three different profiles were found: students’ roles as aggressors (Group 2), victims (Group 3), and bystanders (Group 1). This finding supports the first hypothesis, which states that the combinations of aggression and victimisation among students would result in different profiles of bullying and cyberbullying (aggressor, victim, and bystander), considering the dimensions of the measurement instrument used (Caballo et al., 2012).

Moreover, schoolchildren directly involved in bullying and cyberbullying have lower reading interests and less favourable reading attitudes than bystanders. These results are consistent with the hypothesis proposed. Students who played the role of bystanders have the best values regarding motivation towards reading, reading interests, attitudes towards studying, and collective attitudes. This implies that these students seemed to be highly motivated towards reading. Furthermore, they have greater reading interest and a more positive attitude towards studying and social or collective reading than aggressors and victims. This suggests that passive or active bystanders have a different place in the dyad aggressor-victim (Bartau-Rojas et al., 2018; John et al., 2018; Laninga-Wijnen et al., 2021; Olweus & Limber, 2018). According to Merisuo-Storm and Soininen (2014), students can feel safe and happy, have good relationships with their classmates, and enjoy studying. They may not even experience difficulties in reading (Blewitt et al., 2021; Turunen et al., 2021). Some studies have shown that those who actively defend the victim in front of the bystander who supports the aggressor tend to assume a more critical position regarding harassment (Cuperman, 2010; Wee et al., 2022). Consistent with our study, previous research also found that bullying and cyberbullying aggressors tend to show low motivation towards school tasks (Valle et al., 2006), especially towards reading (Botello, 2016; Rojas et al., 2021). Similarly, victims are more likely to exhibit low school motivation (Garaigordobil & Machimbarrena, 2019). This can affect motivation and reading performance, as revealed in our study (Botello, 2016; Caputo, 2014; Rojas et al., 2021; Young-Jones et al., 2014).

Thus, according to self-determination theory, a positive and supportive social environment is key to academic motivation, which includes students’ involvement in school and educational tasks. Therefore, negative social experiences caused by bullying and cyberbullying can impact academic motivation (Menéndez Santurio et al., 2021). Coexistence problems among schoolchildren lead to strained interactions, especially in those directly involved in the aggressor-victim dyad, thereby affecting students’ motivation to learn (Valle et al., 2006) and academic performance, among others (Nunamaker & Mosier, 2023). Those with difficulties or low interest in reading are usually worried about their position in the group as they try to seek acceptance. This can lead them to show frustration and compensate for their worries with aggressive behaviours by intimidating others (Blewitt et al., 2021; Turunen et al., 2019, 2021).

This study has some limitations. It is a cross-sectional study limited to a specific age group. Thus, the use of questionnaires may be affected by social desirability. Furthermore, data collection was interrupted due to the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, we propose longitudinal studies to analyse the association of reading attitudes and interests with the roles of aggressor and victim in bullying and cyberbullying. Future studies should also consider the teaching staff and family’s point of view. This includes analysing other variables of interest, such as difficulties in reading and students with special educational needs. Furthermore, it would be interesting to analyse family variables that may influence reading habits, motivation for reading, and improvements in bullying and cyberbullying problems. However, more research on early childhood education should be conducted to obtain comparative results (De Vicente-Yagüe & González Romero, 2019; Méndez et al., 2020).

Notably, in the current educational context, this study’s applicability and implications are relevant at the theoretical level since they allow for subsequent research and at the practical level for necessary measures. First, this study’s results provide insights into bullying and cyberbullying for researchers and theorists by presenting a more exhaustive knowledge of the profiles of students involved in bullying and cyberbullying and their relationship with reading attitudes and interests. Through the profiles, it is possible to identify schoolchildren who have low reading motivation and who, in turn, could be directly involved as aggressors and victims of bullying and cyberbullying. Second, this study aims to propose preventive actions to improve school coexistence. Programs focusing on the specific roles of students in bullying and cyberbullying (victims, aggressors, and bystanders) can be employed based on our results. Evidence suggests that current policies and intervention programs administered through the education system that address inclusion and bullying to raise awareness and understanding of victimisation are effective. However, the problem has not been completely eradicated, and they do not provide long-term solutions (Nunamaker & Mosier, 2023). Programs aimed at bullying prevention have reduced approximately 20% cases of aggression, 15–16% cases of victimisation among schoolchildren, (Gaffney, Ttofi et al., 2019), and 10–15% cases of cyberbullying (Gaffney, Farrington et al., 2019). Therefore, exploring additional strategies is essential. Given that reading and writing are imperative parts of the learning process, school curriculum interventions that include these teaching tools should be viewed as effective avenues to address bullying and cyberbullying. This is why actions aimed at promoting reading interest, attitudes towards social or collective reading and studying, and motivation for reading are essential. Additionally, reading can promote values such as coexistence (Correa, 2008; Valderrama & Rubio, 2018). Some interventions have used picture books to encourage cooperative work, conflict resolution, respect, school mediation, empathy, and family involvement among students (Cocco et al., 2023; Merisuo-Storm & Soininen, 2014; Wee et al., 2022; Yubero & Larrañaga, 2014). Through books, it is possible to make various aspects of bullying visible (Cocco et al., 2023; Hoster, 2007; Larrañaga et al., 2015). These strategies can facilitate the identification of students’ roles as aggressors, as they tend to have more difficulty empathising with the victim in the story, show denial, and criticise the victim’s behaviour (Cuperman, 2010). The stories in books teaches victims how to fight and confront problems and how words and actions shape people. They also inspire them to defend their rights assertively through different characters and events (Gallagher, 2009).

Additionally, the role of bystanders in prevention and intervention programs is particularly relevant because they can influence the development of programs owing to their active role in defending the victim (Gaffney, Farrington et al., 2019; Gaffney, Ttofi et al., 2019). For example, bullying can be experienced from the perspective of a bully or victim. However, through reading and subsequent guided classroom discussions, teachers can help bystanders (passive and active) to be aware and to reconsider their preconceived notions of the labels ‘victim’ and ‘bully’ (Pytash et al., 2013). Thus, the aggressor-victim dyad is broken through bullying and cyberbullying prevention programs that includes all those involved. This facilitates a dynamic and integral way to educate in solidarity about the management of justice, cooperation, help, respect, dialogue, school mediation, and more (Gutiérrez Ángel, 2019; Íñiguez-Berrozpe et al., 2020; Larrañaga et al., 2015; Yubero & Larrañaga, 2014).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2024 Inmaculada Méndez, Irma Elizabeth Rojas Gómez, Cecilia Ruiz-Esteban, María Dolores Delgado, José Manuel García-Fernández