Until the shaken snowglobe settles: Feeling unsettled when using social media during COVID-19

Vol.18,No.2(2024)

Previous research establishing the connection between social media and well-being is particularly relevant in light of findings of increased social media use during the COVID-19 pandemic. While research has fairly consistently established a relationship between media use, anxiety, depression and other indices of well-being, it has been less consistent in tying these variations to technology and user related factors. Researchers advocating for the interdependence of these factors suggest that the way users attune to the medium is decisive regarding its meaning for the user. Taking up the call for research to explore the dynamic interplay between users and technology and its relationship to well-being, we adopted a phenomenological approach using a reflexive thematic analysis method to highlight our participants’ concerns when using and engaging with social media during COVID-19. Specifically, we illuminate how participants are attuning to social media such that they experience it unsettlingly. Results revealed being unsettled during COVID-19 in the face of social media comprises three distinct movements: rupture, recollection, and resolution. Being unsettled emerges when an individual is experientially efficaciously detached from the past and its future instead engulfed in an encompassing and expanding now that is unclear and ambiguous. These results shed light on the inconsistencies found in previous literature and the importance of an experiential dimension in psychological research.

well-being; COVID-19; social media; unsettled; qualitative; phenomenology

Brittany Landrum

Psychology Department, University of Dallas, Irving, Texas, USA

Brittany Landrum has a PhD in Experimental Psychology and is currently an Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of Dallas. Her recent research has focused on qualitative research methods, technology, gender, and online learning. Her scholarly interests include quantitative and qualitative research methodology, mixed methods, and philosophical foundations of research.

Gilbert Garza

Psychology Department, University of Dallas, Irving, Texas, USA

Gilbert Garza holds a PhD in psychology from Duquesne University and is currently Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Dallas. His scholarly interests include technology, media, qualitative and phenomenological research methodology, mixed methods research, and the philosophical foundations of and the relationship between quantitative and qualitative research.

Bendau, A., Petzold, M. B., Pyrkosch, L., Mascarell Maricic, L., Betzler, F., Rogoll, J., Große, J., Ströhle, A., & Plag, J. (2020). Associations between COVID‑19 related media consumption and symptoms of anxiety, depression and COVID‑19 related fear in the general population in Germany. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 271(2), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-020-01171-6

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., Davey, L., & Jenkinson, E. (2022). Doing reflexive thematic analysis. In S. Bager-Charleson & A. McBeath (Eds.), Supporting research in counselling and psychotherapy: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13942-0_2

Chao, M., Xue, D., Liu, T., Yang, H., & Hall, B. J. (2020). Media use and acute psychological outcomes during COVID-19 outbreak in China. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 74, 102248. https://doi.org/1016/j.janxdis.2020.102248

Churchill, S. (2022). Essentials of existential phenomenological research. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000257-000

Coleman, R. (2020). Making, managing and experiencing ‘the now’: Digital media and the compression and pacing of ‘real-time.’ New Media & Society, 22(9), 1680–1698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820914871

Coleman, R., & Lyon, D. (2023). Recalibrating everyday futures during the COVID-19 pandemic: Futures fissured, on standby and reset in mass observation responses. Sociology, 57(2), 421–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380385231156651

Cresswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed method research (2nd ed.). Sage.

Dahlberg, K., Drew, N., & Nyström, M. (2001). Reflective life-world research. Studentlitteratur.

Dyar, C., Crosby, S., Newcomb, M. E., Mustanski, B., & Kaysen, D. (2022). Doomscrolling: Prospective associations between daily COVID news exposure, internalizing symptoms, and substance use among sexual and gender minority individuals assigned female at birth. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 11(1), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000585

Ellis, W. E., Dumas, T. M., & Forbes, L. M. (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 52(3), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000215

Ellison, N. B., Pyle, C., & Vitak, J. (2022). Scholarship on well-being and social media: A sociotechnical perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, Article 101340. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101340

Fraser, A. M., Stockdale, L. A., Bryce, C. I., & Alexander, B. L. (2021). College students’ media habits, concern for themselves and others, and mental health in the era of COVID-19. Psychology of Popular Media, 11(2), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000345

Gao, J., Zheng, P., Jia, Y., Chen, H., Mao, Y., Chen, S., Wang, Y., Fu, H., & Dai, J. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE, 15(4), Article e0231924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924

Garza, G. (2004). Thematic moment analysis: A didactic application of a procedure for phenomenological analysis of narrative data. The Humanistic Psychologist, 32(2), 120–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873267.2004.9961749

Garza, G. (2011). Thematic collation: An illustrative analysis of the experience of regret. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 8(1), 40–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780880903490839

Garza, G., & Landrum, B. (2015). Meanings of compulsive hoarding: An archival project-ive life-world approach. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(2), 138–61.

Goodwin, R., Palgi, Y., Hamama-Raz, Y., & Ben-Ezra, M. (2013). In the eye of the storm or the bullseye of the media: Social media use during hurricane Sandy as a predictor of post-traumatic stress. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(8), 1099–1100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.04.006

Griffioen, N., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., van Rooij, M., & Granic, I. (2021). From wellbeing to social media and back: A multi-method approach to assessing the bi-directional relationship between wellbeing and social media use. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 789302. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.789302

Hall, B. J., Xiong, Y. X., Yip, P. S. Y., Lao, C. K., Shi, W., Sou, E. K. L., Chang, K., Wang, L., & Lam, A. I. F. (2019). The association between disaster exposure and media use on post-traumatic stress disorder following typhoon Hato in Macao, China. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1558709

Hammad, M. A., & Alqarni, T. M. (2021). Psychosocial effects of social media on the Saudi society during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 16(3), Article e0248811. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248811

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time. (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Harper & Row. (Original work published 1927).

Houston, J. B., First, J., & Danforth, L. M. (2019). Student coping with the effects of disaster media coverage: A qualitative study of school staff perceptions. School Mental Health: A Multidisciplinary Research and Practice Journal, 11(3), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9295-y

Husserl, E. (1960). Cartesian meditations: An introduction to phenomenology (D. Cairns, Trans.). Martinus Nijhoff (Original work published 1929). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-4952-7_1

Keles, B., McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

Landrum, B., & Davis, M. (2023). Experiencing oneself in the other’s eyes: A phenomenologically inspired reflexive thematic analysis of embodiment for female athletes. Qualitative Psychology, 10(2), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000256

Landrum, B., & Garza, G. (2015). Mending fences: Defining the domains and approaches of quantitative and qualitative research. Qualitative Psychology, 2, 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000030

Levitt, H. M., Motulsky, S. L., Wertz, F. J., Morrow, S. L., & Ponterotto, J. G. (2017). Recommendations for designing and reviewing qualitative research in psychology: Promoting methodological integrity. Qualitative Psychology, 4(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000082

Li, M., Xu, Z., He, X., Zhang, J., Song, R., Duan, W., Liu, T., & Yang, H. (2021). Sense of coherence and mental health in college students after returning to school during COVID-19: The moderating role of media exposure. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 687928. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.687928

Liu, T., Zhang, S., & Zhang, H. (2022). Exposure to COVID-19-related media content and mental health during the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in China. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 63(4), 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12805

Lupinacci, L. (2021). “Absentmindedly scrolling through nothing”: Liveness and compulsory continuous connectedness in social media. Media, Culture & Society, 43(2), 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720939454

McNaughton-Cassill, M. E., & Smith, T. (2002). My world is ok, but yours is not: Television news, the optimism gap, and stress. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 18(1), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.916

Nakayama, C., Sato, O., Sugita, M., Nakayama, T., Kuroda, Y., Orui, M., Iwasa, H., Yasumura, S., & Rudd, R. E. (2019). Lingering health-related anxiety about radiation among Fukushima residents as correlated with media information following the accident at Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. PLoS ONE, 14(5), Article e0217285. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217285

Neira, C. J. B., & Barber, B. L. (2014). Social networking site use: Linked to adolescents’ social self‐concept, self‐esteem, and depressed mood. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66(1), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12034

O’Reilly, M., Dogra, N., Whiteman, N., Hughes, J., Eruyar, S., & Reilly, P. (2018). Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing? Exploring the perspectives of adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 23(4), 601–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104518775154

O’Reilly, M., Dogra, N., Hughes, J., Reilly, P., George, R., & Whiteman, N. (2019). Potential of social media in promoting mental health in adolescents. Health Promotion International, 34(5), 981–991. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day056

Price, M., Legrand, A. C., Brier, Z. M. F., van Stolk-Cooke, K., Peck, K., Dodds, P. S., Danforth, C. M., & Adams, Z. W. (2022). Doomscrolling during COVID-19: The negative association between daily social and traditional media consumption and mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 14(8), 1338–1346. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001202

Roche, S. P., Pickett, J. T., & Gertz, M. (2016). The scary world of online news? Internet news exposure and public attitudes toward crime and justice. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 32(2), 215–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-015-9261-x

Schutz, A., & Luckmann, T. (1973). The structures of the life-world (R. Zaner & H. T. Engelhart, Jr., Trans.). Northwestern University Press.

Şentürk, E., Geniş, B., Menkü, B. E., & Cosar, B. (2021). The effects of social media news that users trusted and verified on anxiety level and disease control perception in COVID-19 pandemic. Klinik Psikiyatri Dergisi: The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 24(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.5505/kpd.2020.69772

Shabahang, R., Kim, S., Hosseinkhanzadeh, A. A., Aruguete, M. S., & Kakabaraee, K. (2022). “Give your thumb a break” from surfing tragic posts: Potential corrosive consequences of social media users’ doomscrolling. Media Psychology, 26(4), 460–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2022.2157287

Sharma, B., Lee, S. S., & Johnson, B. K. (2022). The dark at the end of the tunnel: Doomscrolling on social media newsfeeds. Technology, Mind, and Behavior, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000059

Valkenburg, P., Beyens, I., Meier, A., & Vanden Abeele, M. (2022). Advancing our understanding of the associations between social media use and well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101357

Valkenburg, P., & Peter, J. (2013). The differential susceptibility to media effects model. Journal of Communication, 63(2), 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12024

Vernon, L., Modecki, K. L., & Barber, B. L. (2017). Tracking effects of problematic social networking on adolescent psychopathology: The mediating role of sleep disruptions. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1188702

von Eckartsberg, R. (1998). Existential-phenomenological research. In R. Valle (Ed.), Phenomenological inquiry in psychology: Existential and transpersonal dimensions (pp. 21-61). Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0125-5_2

Zhang, M. (2020, November 6). When at home: A phenomenological study of zoom class experience [Paper presentation]. Technology and the Future of the Home Conference, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, MO, USA. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3671805

Zhao, N., & Zhou, G. (2020). Social media use and mental health during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Moderator role of disaster stressor and mediator role of negative affect. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 12(4), 1019–1038. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12226

Authors’ Contribution

Brittany Landrum: conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, methodology, writing—review & editing. Gilbert Garza: conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

September 23, 2022

Revisions received:

July 13, 2023

January 2, 2024

Accepted for publication:

March 4, 2024

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

Picture a souvenir snowglobe. A staple of souvenir shops and a common trinket, it depicts a typically idyllic scene that when shaken disperses particles in an illusion of snowfall temporarily occluding the scene until the particles settle. Since March of 2020 many of us have had the experience of living in such a trinket in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its fallout. In the absence of in-person connections, we turned towards electronic communication encountering a wide range of opinions, beliefs, and information about the pandemic. The current study seeks to explore the intentional horizons of attunement during the experience of being unsettled upon encountering something on social media.

The Complex Relationship Between Media and Well-Being

Research exploring the link between media and well-being is vast with wide ranging approaches, areas of focus and conclusions. In their review of the literature, Keles et al. (2020) found a general correlation between social media use and mental health—anxiety, depression, and distress—but noted that the relationship was complex and inconsistent. Furthermore, Valkenburg et al. (2022) highlighted the often contradictory and inconclusive patterns that have emerged in this field, noting that social media use is neither wholly beneficial nor detrimental to one’s mental health, citing a growing need to address these contradictory findings. These relationships are particularly important to explore in the context of COVID-19 as Ellis et al. (2020) and Fraser et al. (2021) both found that social media duration increased during the pandemic and in turn negatively impacted mental health outcomes.

Indeed, research focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic has found anxiety, depression, and social isolation were positively associated with social media exposure (Gao et al., 2020; Hammad & Alqarni, 2021) including both the duration and frequency of social media use (Bendau et al., 2020). Similarly, Ellis et al. (2020) found that more time on social media and virtually connecting to friends was related to higher reported depression symptomatology, however, time engaging with family in person was related to less reported depression symptomatology among teens during the COVID-19 crisis. These findings are similar to related literature exploring other natural disasters, including a positive relationship between the use of social media to learn about Hurricane Sandy and post-traumatic stress responses (Goodwin et al., 2013), the use of internet sources and consuming less local TV content being associated with more anxiety following the Fukushima nuclear disaster (Nakayama et al., 2019), and typhoon survivors who met the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) reporting higher media consumption (including TV, radio, online news, and social media; Hall et al., 2019). Together this literature has shown a prevailing link between media and negative well-being outcomes giving rise to threads focusing on either technology-related factors or user-related variables.

Technology Factors

In focusing on technology-related factors, literature has explored types of media and types of content. Consumption of legacy media and social media have been inconsistently related to mental well-being outcomes (e.g., Chao et al., 2020; Roche et al., 2016). Bendau et al. (2020) found that more frequent use of all types of media was associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Compared to people not using social media at all, users who reported social media being their primary source of information reported more unspecific anxiety and COVID-19 specific anxiety. In contrast, those who used official websites as their primary source of information reported less of both types of anxiety. However, Fraser et al. (2021) found that anxiety and depression were unrelated to consumption of TV, social media, and video games during COVID-19. Price et al. (2022) found that while social media consumption was positively associated with depression and PTSD during the pandemic, consumption of legacy media was not.

Regarding type of content on media, Li et al. (2021) found that exposure to negative COVID-19 information (e.g., deaths) was associated with greater stress, depression, and anxiety but no relationship to well-being was found for exposure to positive COVID-19 information (e.g., heroic stories). While Chao et al. (2020) similarly found that exposure to negative COVID-19 news was related to depression and negative affect, they contrastingly found that positive news exposure was associated with positive affect and less depression. Some literature focused on doomscrolling, a phenomenon which emerged in research during the pandemic, describing an individual engaging with content that is experienced as negative. Increased engagement with media in this way had an abiding negative association with mental health, specifically with anxiety, depression, satisfaction with life, and fear of missing out (Shabahang et al., 2022; Sharma et al., 2022). Additionally, Dyar et al. (2022) found a bidirectional association between consumption of COVID-19 news and COVID-19 distress, suggesting that the user’s level of comfort regarding news consumption might be driving the type of content sought. These inconsistent findings suggest that technology factors alone may not be singularly decisive in relationship to well-being. To address these inconsistencies, another thread in the literature has explored user-related factors.

User Factors

Making user engagement with media the focus of their inquiry, McNaughton-Cassill and Smith (2002) distinguished between active attention paid and mere exposure, and found TV attention, but not TV exposure, positively correlated with trait anxiety. Moreover, those with high attention paid to TV reported a higher perception of the severity of problems at the national and community level compared to those with low attention paid to TV. Correspondingly, Neira and Barber (2014) and Vernon et al. (2017) found that investment in social media was associated with higher depression. Employing a user-centered approach, Griffioen et al. (2021) found that a social stress manipulation did not impact subsequent time spent on social media nor impact reported reasons for engaging with social media. Additionally, the use of social media following the manipulation did not predict well-being measures finding no support for a bidirectional relationship between social media and well-being. While these user-centered studies have inconsistent results, much like the technology focused ones, they emphasize how users are engaging with social media, opening up the possibility of exploring how the impacts of social media might differ between individuals.

Exploring well-being differences between four different categories of COVID-19 media exposure (ranging from slightly to highly), Liu et al. (2022) found that while stress, anxiety, and depression did not differ, positive and negative affect were significantly higher in the highly exposed group compared to the other three. While seemingly contradictory, these results would suggest that individuals are engaging with this technology in a variety of ways not disconnected from the types of content they are exposed to and actively seeking out. In a similarly user-centered vein, Şentürk et al. (2020) found that greater trust in both official and unofficial social media accounts was associated with users believing they had more effective micro control over COVID-19 (personal precautions), while less exposure to negative social media COVID-19 content and greater trust in official social media accounts was associated with believing they had more effective macro control over COVID-19 (government precautions). Overall, greater state anxiety was negatively correlated with trust in official social media accounts. Together these studies suggest that the impact of any medium depends on how the user regards and engages with it.

Houston et al. (2019) interviewed school staff who described how children responded to disaster media and how staff helped them to understand and cope with the events depicted. The staff and children understood media differently in view of their different socially networked concerns and the meaning of these events in their lives. In a pair of studies, O’Reilly et al. asked adolescents about the perceived threats (O’Reilly et al., 2018) and perceived benefits (O’Reilly et al., 2019) of social media on mental health. In the former, adolescents pointed to the addictiveness of engaging with social media and the potential for cyberbullying; in the latter, they described the ability to find resources on mental health to learn about well-being. These studies reveal how social media is neither wholly good nor bad, but its meaning depends on the user’s concerns. When seeking to learn more about health, social media can be experienced as beneficial given this aim and the opportunity to find resources on this topic. When a user finds themselves unable to stop using social media at the cost of forsaking other activities, social media can be experienced as detrimental. Hence, the technology and content appear meaningful—as either threatening or beneficial—in light of how the adolescents understand their concerns and aims. These qualitative studies highlight how the users’ dispositions toward the media are important in discerning its meaning and impact. Juxtaposing the user-centered literature with the technology-focused literature begs the question of how these two threads might jointly contribute to well-being.

Integration

While the studies on user-related factors shed unique light on the importance of how users are engaging with social media, these findings do not resolve the inconsistencies found in the technology-focused studies but add new questions about how individuals are differentially impacted by social media as well as questions about how technology factors might interconnect with user factors. Indeed, what these two prevailing threads in the literature reveal is that an exclusive focus on one dimension may cover over the importance of the other. As the effects of social media can vary not only across individuals but even within individuals, Valkenburg et al. (2022) advocate for further research, utilizing “person-specific methods” (p. 5), to explore this complex relationship by focusing on how individuals actively engage with and agentically interact with social media. To emphasize the dynamic interplay between both user and technology, two theoretical approaches have been proposed: the Differential Susceptibility to Media Effects Model (DSMM; Valkenburg & Peter, 2013) and the Sociotechnical Perspective (Ellison et al., 2022). Both emphasize that technology alone is not working independently on a passive social media user. Specifically, DSMM emphasizes that a person’s susceptibility to the effects of media is mediated by their cognitive, emotional, and excitative states (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013). These person-specific variables emphasize how individuals relate differently to social media content and in turn are impacted by this content. Using the DSMM, Zhao and Zhou (2020) found that exposure to disaster content on social media was positively associated with depression but only for those who scored high on COVID-19 stress. Exploring both user and technology-related variables, their results highlight how certain individuals may be more susceptible to the effects of social media, which in turn might predict social media engagement and type of content sought.

The Sociotechnical Perspective emphasizes how media are situated socially, advocating for a balanced perspective on both the role that technology plays as well as the agentic users who engage with this technology (Ellison et al., 2022). In this light, social media are mutually intertwined with the people who use them and together they reciprocally influence each other. Social media—as technology—offers new ways of engaging with others, accessing content, sharing information, and spending our time. How users seek out, engage with and interact with social media in light of the possibilities afforded by this technology has implications for how we experience the world, ourselves, others, our place in the world, and time. Seeing these two dimensions as interdependent opens up the possibility of exploring new understandings that would not be seen when looking at either dimension in isolation. One of these possibilities is the way time is experienced, particularly when one is engaging with online spaces.

Online Temporality

In the scientific literature, time is often measured in increments of duration or frequency. In the literature we reviewed above, time has been measured as average daily media usage and times accessed per day (Bendau et al., 2020), closed-ended hourly time intervals per day (Ellis et al., 2020; Fraser et al., 2021), and closed-ended frequency rating scales (e.g., never to very often; Chao et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2020). These operationalized definitions capture how much clock time or objective time has passed or how often one uses media-capturing dimensions of magnitude. Yet, time is also experienced—it can pass slowly or quickly, expand or contract, flow continuously or be interrupted. Indeed, there are two important lived dimensions of time: the not yet and already (Heidegger, 1927/1962) highlighting how time is experienced dynamically rather than proceeding linearly. In this light, time can be explored in more ways than just duration or frequency. For example, rather than seeing time as a series of equal intervals, Coleman (2020) explored how time is lived as a dynamic interplay across the dimensions of past, present and future. In researching digital time, Coleman reveals how ‘the now’ becomes focal, eclipsing the other two dimensions as people engage with and interact with online content. Moreover, during COVID-19, Coleman and Lyon (2023) discovered how time can become fissured, where the present and future are increasingly disconnected and severed. In tune with the idea that the amount of time on social media is less crucial than its meaning, Fraser et al. (2021) found that mental health outcomes were not directly related to consumption of media during COVID-19. They found that mental health moderated the relationship between change in social media consumption prior to and during COVID-19 and concern for society and users’ future. The relationship between social media consumption change and concern for society was strongest at high levels of depression, while the relationship between social media consumption change and concern for their future was strongest at high levels of anxiety. These three studies highlight how an expanded understanding of time—including one’s future self, the self that one is aiming to be—enables researchers to explore how time is lived by users as they interact with and engage with social media. This focus on lived time may shed new light on the past inconsistencies of the link between social media and well-being.

By adopting a phenomenological approach which incorporates this lived experience of time, Lupinacci (2021) explored how users engage with social media, shedding light on the unsettledness and ambivalence afforded by the continuous connectedness proffered by this medium. In a similar vein, Zhang (2020) adopted a phenomenological approach to explore how spatial and temporal dimensions were lived in a Zoom class during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results showed how changes in the way participants experienced space and time had profound impacts on their understanding of themselves and their situations. Both of these studies highlight a proclivity to seek a feeling of at-homeness or settledness when our past-present-future and our bodies-in-space are connected. By focusing on the ways in which a person is concerned with and how they are interacting with social media in light of their concerns, a more nuanced conception of social media and well-being can be discovered.

The Current Study

The literature has indicated that there is a relationship between social media use and well-being but has not yet uncovered how this relationship emerges. Ellison et al. (2022) and Valkenburg et al. (2022) advocate for an approach that equally emphasizes the two poles of the relationship—the social media user and the technology being used—in order to address the conflicting findings on the relationship between them and well-being. Social media are meaningful in light of the individuals who are engaging with them, as they take up posts, content, and activities out of their concerns and involvement with the world. In short, social media are not beneficial or threatening or anything else absent someone’s engagement with it. To speak of social media is to already imply and implicate the person to whom it appears, the person engaging with and experiencing social media.

Taking up these calls for future research, we adopted a phenomenological approach which emphasizes the interconnectedness of a person and the world they bring to light out of their concerns and involvement (Heidegger, 1927/1962). As a person-specific approach, our phenomenological method is particularly suited to explore these complex and nuanced patterns of engagement with social media highlighted by Valkenburg et al. (2022) to begin uncovering the dimensions of how this relationship is lived. This approach enables us to explore one of these dimensions—time as experienced—to help shed light on how using social media transforms one’s temporal and spatial place in the world. Drawing on both Zhang (2020) and Lupinacci (2021), our research expands upon the experience of unsettledness while using social media during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our phenomenological approach is poised to answer this question (RQ1): how must a person be engaged with and interact with social media such that the experience is unsettling? That someone feels unsettled when using social media speaks to how they are intentionally constituting and experiencing the situation. As the occasion for, not the cause of, experiencing, social media are understood as the lived situation we can ask about to shed light on how someone must be attuning to and engaging with their world such that they feel this way. Our focus in this paper is to explore unsettled experiencing by examining how participants meaningfully engaged with social media during the pandemic. Unsettled experiencing entails possible selves in relation to who we are aiming to be, and thus deals with dimensions of temporality, which we detail below. As we began our research during the COVID-19 pandemic, our specific research question centred on the experience of being unsettled but our findings have implications for other aspects of well-being, including positive and transformative experiences which we will explore in the discussion.

Methods

Approach

Quantitative and qualitative research have different epistemological foundations and generate different knowledge claims (Landrum & Garza, 2015). Specifically, quantitative research focuses on dimensions of magnitude, while qualitative research focuses on meaning, each bringing into relief aspects of the topic being investigated that the other cannot. The complementarity of these approaches enable us to further explore the inconsistencies noted in the relationship between social media and well-being in the literature as a case in point. To address the call for future research exploring the integration of technology and the user, we adopted an explicitly phenomenological approach, which understands meaning as originating in the intentional relationship of consciousness to its objects. In a phenomenological qualitative approach, the focus is on the world of experience and engagement. This world has historically been termed the lifeworld which can only be discerned by bracketing our natural attitude, or our ordinary, taken for granted presumption of the world as existing independent of our involvement (Dahlberg et al., 2001; Husserl, 1929/1960; Schutz & Luckmann, 1973). The lifeworld describes “the locus of interaction between ourselves and our perceptual environments and the world of experienced horizons within which we meaningfully dwell together” (von Eckartsberg, 1998, p. 4). In the natural attitude, the object in question, such as social media, is treated as existing independent of someone’s concerns, with a predetermined and predefined meaning, as seen in examples of social media content being described as threatening, positive, negative, or even benign. Seen in this way, the object in question has an impact (or not) on the person exposed to it. Yet, each of these meaning-filled descriptions implicate a person who takes up the object in this way (i.e., a person sees social media as unsettling). Every encounter entails an interplay between what appears and how it appears (Husserl, 1929/1960), the latter of which Husserl calls intentionality and Heidegger (1927/1962) calls concern. In adopting a phenomenological approach and bracketing the natural attitude, we are in a position to start to uncover and discern how a person must be looking such that social media is experienced a certain way. Thus, social media appears to a person who is actively, agentically, and intentionally constituting their world. What are the horizons of their concern? Who are the selves they are aiming to be and the worlds they aim to occupy such that one unsettlingly attends to social media? In conducting a phenomenological study, our focus on intentionality aims to shed light on an individual’s concerns or projects (Heidegger, 1927/1962), how someone is engaged with their world, their constitutive meaning-making stance towards a world of their concerns, the future possibilities of self and world that one is aiming towards. We drew from Heidegger’s insights about human temporality for our analysis by illuminating the participants’ projects and highlighting how they were attuning to their possibilities. Lived temporality is not a linear conception where the future follows from the past through the present but rather where past, present, and future all reciprocally and dynamically inform each other. This focus on one’s projective lifeworld (Garza & Landrum, 2015) is an attunement to the future directedness and the not yet of one’s intentional presence—similar to Churchill’s (2022) focus on in-order-to motives over because motives. In the former, we were concerned with how our participants were concerned with the world and their future possibilities that lie ahead of them in contrast to the latter where elements or factors explain an experience as a consequence of certain facts. In our results, focusing on intentionality meant we attended to the ways people were engaged with social media such that they experienced themselves and the world in an unsettling way. In contrast to the literature that focuses on either the technology aspects or user aspects whereby social media has impacts on well-being rooted in a linearly deterministic conception of temporality, we take as our starting point the interplay of a user and their concerns as they engage with and interact with social media, focusing on their interdependence. Our results aimed to disclose how our participants take up social media meaningfully, illuminating their projects and their concerns about “the self [and world] that awaits me in the future” (Churchill, 2022, p. 16). In sum, by focusing on intentionality, we were able to answer our research question: how must a person be engaged with and interacting with social media such that the experience is unsettling?

Data Collection

Using purposive sampling, data were collected from undergraduate psychology students from a small religiously affiliated university in North Texas taking an upper-level class on qualitative research methods during the fall of 2021 in the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Purposive sampling involves collecting data from those who are thought to have special knowledge or have experience with the phenomenon of interest (Cresswell & Plano Clark, 2011). As our students were in the midst of experiencing the changes brought about by COVID-19 including taking online classes, practicing social distancing, and wearing masks as well as having experience with social media, they were selected as suitable participants given our research aims. We asked our students to write a description of being unsettled as part of a class assignment to demonstrate qualitative data gathering techniques. Students were informed that their responses would be shared with others and might be used in research projects. They were informed that in all cases their responses would be anonymous and identifying information would be removed or changed. Students were given an alternative assignment to complete if they were uncomfortable sharing or did not consent. Students who consented were given the following prompt (adapted from Garza, 2004):

“Describe a specific situation in which you were engaging with social media about the COVID pandemic and felt upset, rattled, shaken, or unsettled. Describe the situation as completely as possible. Describe this situation like a story with a beginning, middle and end, how you came to be on social media, how this experience affected your understanding of yourself, others and the world as well as your future and possibilities. How did this situation conclude or resolve for you?”

After obtaining 30 responses, we eliminated those that were deemed to be off-topic, insufficiently detailed, reflective or which offered theoretical explanations for why (i.e., because motives) they felt the way they did. We followed up with five responses to inquire about additional details (e.g., Can you tell me more about what this situation was like for you?) and to elicit further written descriptions. These five responses were chosen as part of our purposive sampling as they provided information-rich descriptions (Braun & Clarke, 2022). The protocol was approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board (#2022031).

Participants

All of the participants were college seniors between the ages of 19 and 21. Lauren (Latina female) feels ostracized and diminished in view of her skepticism regarding COVID-19 precautions. When she comes across social media content that is at odds with her views, she feels silenced, bullied, and rejected. She longs for the possibility of open discussion and reciprocal understanding. Samantha (Latina female) describes feeling betrayed by her friends who she had previously thought were on the same page regarding COVID-19 precautions in preparation for Samantha’s birthday party. When she discovers through social media that these friends had been lax with precautions, Samantha begins to question who shares her understanding of the situation and her standing in these others’ eyes. Mirabel (Latina female) discovers that her cousin has posted outlandish and conspiratorial views about COVID-19 which threatens her and her grandmother’s sense of safety. Mirabel finds that what she considers to be dangerous attitudes towards COVID-19 are closer to home than she imagined. Dana (white female) is surprised at the degree of hostility expressed in response to her pro-mask social media post. Particularly unsettling was the response from a woman she knew from her church community. She was bewildered at how the woman lashed out at her post and began to question her church community and its values. Watching a video on YouTube, Willow (black female) is at first amused by a catchy up-tempo song which quickly turns to being horrified by the graphics which depict the number of COVID-19 deaths by country. She comes to consider the possibility that she is more affected by the pandemic than she realized.

Data Analysis

We selected five descriptions for our analysis, treating them as a corpus. To analyse the data, we used the phenomenologically-inspired reflexive thematic analysis technique (Landrum & Davis, 2023), a modification of Braun et al.’s technique (2022). This technique takes into account reflexivity by explicitly acknowledging that the participants’ intentionality is refracted through the researchers’ projects and concerns, which are an integral part of the themes that emerge. First, we read the data several times to get a sense of the whole and compile our initial thoughts and observations about the experiences. This step enabled us to become familiar with each piece of data and write a summary for each one. Second, we read the data with our research question—“What does it mean to be unsettled?”—in mind in order to identify the aspects—or moments (Garza, 2004)—of the data that shed light on the phenomenon. These moments were then coded (Braun & Clarke, 2006) with our working notes and impressions of what we found particularly meaningful and revelatory for each moment to begin to highlight the role of intentionality. This process of coding moments was ongoing as we continued to read the data. After coding the moments, we then collated thematically similar moments together to arrive at our initial list of themes across the entire corpus (Garza, 2011). These themes were then transformed so as to thematize intentionality by taking the participants’ naive descriptions and explicitly illuminating how the participants were taking up their world in an unsettled way. Finally, the transformed themes were presented as a thematic narrative and a thematic map to visually illustrate our findings.

Results

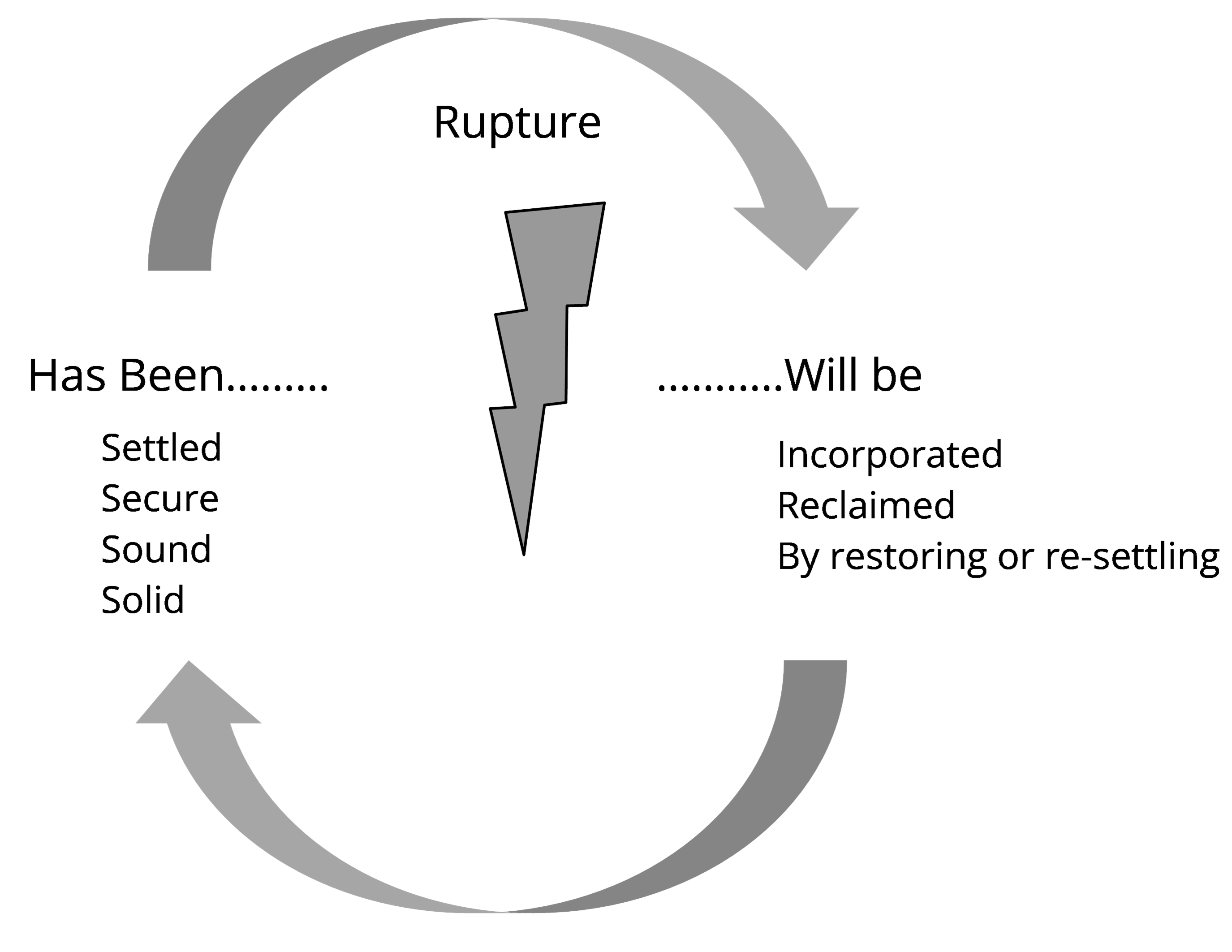

The corpus revealed how being unsettled in COVID-19 played out in three distinct movements. The rupture brought to light a recollection of what has been and what might be. The rift and rupture called the participants’ standing into question, dislodging their previously secure place and footing in the world. In being unsettled, the participants attempted to resolve this discrepancy, reclaim, restore, and resettle their sense of self, relationships with others, possibilities, and place in the world.

Figure 1. The Experience of Being Unsettled.

Note. In being unsettled, participants experienced a rupture in their worlds that brought to light what has been and what would have been as they confronted what this rupture portended for what will be.

Rupture

Being unsettled during COVID-19 entailed a rupture which occurred across dimensions of self, relationships with others, the participants’ place and standing in the world, and temporality. In experiencing this rupture, participants attuned to different possibilities for themselves and were pulled between an acceptable and desirable path and a disconcerting and uncertain place. For instance, Lauren discovered that in the eyes of others her views on COVID-19 were unwelcome and dismissed. She said, “I was frustrated that I felt that I couldn’t say what I wanted to even when (seemingly) everyone else could, simply because I hold unpopular opinions.” Similarly, Dana found certain avenues of expression to be inaccessible to her if she wished to maintain her social connections. She expressed, “I was very hesitant to post anything about COVID-19 because it had become so politicized by then.” For Willow, social media was a place of ambiguity as it both insulated her but served as an ever present reminder of the looming threat of COVID-19:

“The little media I consumed was the news, [YouTube], and TikTok; the first was anxiety-inducing and sobering while the latter two were distracting and entertaining, easily making the anxiety go away until the next meme put another whole [sic] in my bubble. Simply put, social media both reinforced and thinned my bubble.”

In being unsettled, participants were divided between a project to remain true and faithful to their own beliefs even as that commitment came to be understood as exacting a price with respect to being alongside others. The rift called into question their understood place in the world, highlighting an adversarial space of confrontation, ‘cancellation,’ and debasement as the participants discerned with and against whom they stood metaphorically in light of their position on the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, Samantha, in order to maintain and preserve her beliefs about COVID-19 precautions, found herself cutting off friends who were at odds with her views. She described,

“I was already annoyed that I couldn’t do what I originally had wanted to do for my birthday because of [COVID-19], so I was even more irritated that my friends didn’t care and would put me and the 6 other people I had invited in danger.”

Similarly, Dana described, “A lady I have respected for years…essentially insulted me ‘to my face’” highlighting that in being unsettled, Dana reevaluated and reassessed her relationships in light of COVID-19. Thus, for Dana, to be unsettled was to attempt to gain purchase in a shared social world where her standing was subject to sudden transformation and even reversal based on her consonance or dissonance from others. For a moment, Samantha questioned her own views about precautions and its implications with respect to her social bonds.

“For a second I felt like I was being TOO paranoid about [COVID-19]. Then I also kinda wanted not to get together at all, but my other friends were very supportive and wanted to celebrate my bday with me so I didn’t cancel.”

Being unsettled meant participants found themselves in a world where their aims to faithfully be themselves alongside others also included the possibility of being cut off and distanced from certain others. Lauren held contrasting views about COVID-19 precautions, but she too was faced with forsaking a valued standing in relation with others or remaining silent about her views. She stated, “I felt like there wasn’t a channel I could go through to have an honest conversation about my thoughts without being told that I am an uncharitable, self-serving individual and that I care more about ideals than people.” These realignments in social circles affected even long-standing familial relationships as Mirabel discovered:

“When it’s your family member the ‘crazy’ is a little too close for comfort. It feels very in my face and the reality that not only could these people exist, but that I could also love them and generally interact with them makes them more human. They are harder to dismiss and this is what is so irritating.”

In experiencing a rupture, the participants saw the world as they had previously understood it and as they had hoped it would be as inaccessible from their current position. As Willow noted, “I realized that the situation wouldn’t just go away and was actually progressing in a worse direction.” Being unsettled ultimately meant that participants found their aimed at self alongside others to be displaced from a world they had understood and been striving for. Willow attuned to the increasing encroachment of COVID as a threat to her insular and safe space. She wrote,

“For a time, watching the news and obeying the mandates created this distance between me and the pandemic that made it possible for me to just enjoy my time inside…I lived in a rather nice bubble, quite apropos I’d say, that was sometimes not as airtight as I would have liked.”

This rupture harkened to the eruption of previously unseen fissures between what has been and what might have been as the participants discerned what COVID-19 portended for the world, their social standing, and sense of self.

Recollection

The rupture laid bare the past and its anticipated future from the occluded vantage point of the uncertain now. In being unsettled, the participants oriented to what has been and what might be as witness not agent, as passive not active. Being unsettled was for participants to find themselves experientially detached from their agency in an attempt to recapture the past and carry it forward to the future. Samantha bemoaned the lived necessity of the choice that entailed the loss of her anticipated and carefully planned birthday celebration. She said,

“You only turn 21 once, I was finally/officially allowed to go out to clubs and bars and I wanted to go with my squad and experience a normal 21st birthday night out on the town…but it just sucks when you picture doing something for so long and then something out of your control ruins it.”

In longing to return, recover and reconnect their past and future, the participants precariously navigated and attempted to weave together a previously coherent temporality. The rupture brought to light what had previously been solid and secure as now fractured and contingent. Dana began to question her prior relationships and understandings in the aftermath of feeling disrespected in response to her post on masks. After the woman who had ‘attacked’ her posted “[Dana] knows that I love her and would never hurt her,” Dana questioned, “Do I know that, though? She had hurt me. Why deny it?” Similarly, Samantha questioned whether her friends have her back and respect her, writing:

“I was just irritated that those friends didn’t tell me they went to a party after I basically told them I would be uncomfy if they did. So seeing them on social media not caring about/respecting the boundaries I made for my friends and my own safety was annoying.”

Mirabel described a similar social disruption in writing, “It was crazy that people could distort scientific facts to boost their political beliefs, candidate or party.” In laying bare what has been lost, the participants discovered a previously settled and taken-for-granted situation.

How the participants would recover this anticipated future was a plaguing question as they attempted to find their footing and secure their place in the world again. The essence of being unsettled while engaging social media during COVID-19 was to experience the pandemic as rupturing the anticipated continuity of past and future through now, to find the past and future efficaciously disconnected, and to feel called to reconnect these dimensions of time but feeling unable to do so. Willow pondered the current situation, unsure how it happened; “I stopped smiling in amusement at the stupidity of the video, and nostalgia at the music, and thought, ‘What the [heck] [sic] is going on with this country?’”

The participants’ upsetness and discomfort with where they currently found themselves was an expression of their investment in the way things had been prior to the rupture. Mirabel remarked on the overwhelming presence of COVID-19 in her life writing, “The constant presence of the gloomy reality was exhausting…[COVID-19] was everywhere. There was no escaping the reality of how the virus had taken over the world, the town and my life in particular.” Lauren longed for the way things were as she described the current state of her relationships: “I have either been cut off from relationships or there has been a serious strain placed on relationships due to this lack of being able to openly discuss differences.” In being unsettled, the participants felt disconnected and displaced from where they currently found themselves, a stranger in their own world. As Willow stated, “I was somehow filled with pure disbelief and a sudden crystal-clear awareness of just how much [COVID-19] has spread, and, with wry amusement, how the US just had to be number one.” The uncanniness that the rupture brought stood in stark contrast to what has been and threw into question what comes next.

Resolution

In resolving the feeling of being unsettled, the fractured aspects of self and world and disconnected timeline begin to be woven together through the participants’ understanding of how their world has changed. Resolution meant to give the rupture a place with respect to what has been and what will be. By resolving the rupture, the participants’ world is not necessarily the same as before nor harmoniously reconciled. For Lauren, her valuation of certain social relationships came at the price of silencing herself and not being true to herself. She described, “I’ve even recognized myself downplaying my opinions for the sake of keeping the peace.” In contrast, Mirabel gave voice to her feelings, reclaiming her agency enabling her to reconcile and make sense of her current situation and its possible future. She wrote, “Nonetheless I know I do not have to let myself become upset, I am responsible for my emotions and I can disagree without becoming angry.” Among the many possibilities for resolution, an individual may attempt to rejoin the previous timeline, living the rupture as a temporary and isolated event. Alternatively, a person may deny and attempt to forget the changes the rupture has wrought. Or, finally another option may be to live the rupture as demarcating two distinct regions of time—before and since.

The rupture may forever change the world and a person’s place in it. The move to resolve the fracturing of the rupture brought to mind the Japanese art form kintsugi where the pieces of broken objects are rejoined in a way that highlights and accentuates the breaks. For example, Samantha proceeded with her party, albeit on a smaller scale. She said, “I ended up having an amazing time with a handful of my closest friends doing something more chill than originally planned.” Dana, likewise, continued her relationship with the lady she felt had insulted her but acknowledged the fractures that still persist. She described, “Nevertheless, the damage had been done. I did my best to patch up the comment section and smooth things over, since I do respect this lady and, until the pandemic, she had always been such a kind human being.” Another alternative may be to repair the pieces by making the fractures invisible. This appeared in Samantha’s description of her friends who partied as if COVID-19 posed no threat. Throughout Willow’s description, she used numerous minimizing statements that downplayed how COVID has changed her world (e.g., “a simple moment”, “a bit unsettled”, “minor time”, “just a tiny moment”, “wasn’t overwhelming or life-changing”). Whichever way was taken, the unsettling rupture receded and fell by the wayside as an individual marched towards the reclaimed future where the rupture was no longer unending and interminable. When a person re-settles and resituates themselves, the rupture moves from an ongoing now to what has been and their future is now no longer engulfed and clouded by the rupture.

Discussion

A guiding image which has emerged from the analysis of data is that of a snow globe. The phenomenon of being unsettled during COVID-19 is akin to having an established and settled world shaken metaphorically. As in a snow globe, the shaking obscures the sense that the world had previously made and raises the question of what will resolve when the ‘snow’ settles. Being unsettled is to remain in a disconnected now, separated from a past and its future. Being unsettled is to find oneself disrupted, looking forlornly at a previously sought after but now uncertain future, seeking to recover and restore at-homeness and settledness in the world again. Being unsettled ultimately means that a person finds themselves to be displaced from a world they understood and aimed at.

Return to the Literature

Past literature has established a relationship between social media use and well-being, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Bendau et al., 2020; Ellis et al., 2020). However, inconsistencies were seen in literature that explored technology-related factors, including whether legacy and social media have similar effects on well-being (e.g., Price et al., 2022) and how different types of content might impact well-being (e.g., Chao et al., 2020; Shabahang et al., 2022). Literature focusing on user-related factors revealed how a user’s concerns shaped the type of content sought and its impact on well-being (e.g., Griffioen et al., 2021; Neira & Barber, 2014) but likewise showed inconsistencies. In these attempts to parse out user specific variables as distinct and separate from social media content, these two threads in the literature occlude how the user interacts with technology and how technology is understood in light of one’s concerns and engagement with it. Literature that explored this very connection pointed to the importance of the concerns out of which the meaning of the media emerges for its user (e.g., Ellison et al., 2022; Valkenburg et al., 2022; Zhao & Zhou, 2020). By adopting a phenomenological qualitative approach, we are adding to this integration literature, highlighting how users are concerned and engaged with social media meaningfully. The conflicting findings on whether a person is exploring news content, seeking information, or making connections on social media or other devices all aim to explain well-being as the outcome or predictor of social media use. Our study instead explores how a user takes up social media content out of their concerns and projects, whereby being unsettled is one way of taking up and engaging with technology.

As seen in Hall et al. (2019), the consonance or dissonance of content with a person’s own views are tied to media’s impacts on well-being. Our own research reveals how being unsettled unfolds when a user encounters conflicting and contrasting points of view that raise questions about their grasp of the world. These alternative view points are taken up meaningfully by participants as threats, rupturing what had been a solid and secure foundation. Being unsettled is when what they thought they knew and took to be the case are called into question when they encounter something challenging on social media. Social media content is neither upsetting nor affirming independent of someone looking. Thus, content that disaffirms and conflicts with a person’s valued projects for the world is lived as upsetting and unsettling and presumably content that is consistent with the world in which a person is aiming would be affirming and encouraging. Fraser et al. (2021) explored two types of concerns—a person’s future and for society—which were affected by social media exposure. As a moderator, anxiety was not the outcome of consuming social media but rather a way in which a person took up content. Our study also highlights that content that is experienced as unsettling raises questions with respect to a person’s social standing and their anticipated future and the future of the world.

One of the possibilities that emerges when considering both the user and their use of technology together is exploring how people experience their world, including their lived sense of time going beyond just the concern with one’s future as established by Fraser et al. (2021). Our results show a striving for connectivity between how I have been, how I am, and how I will be that when thrown into question is experienced as unsetting. Thus, in engaging with social media, this online digital space opens up new horizons of possibilities for the user, their future selves, and the world they aim to inhabit. How one experiences time in this new digital space goes beyond previous conceptions of time as how long one spends on social media and how frequently one visits social media sites. Lived temporality is part of the ongoing constitutive understanding of who I am, who I will be and the suitability of the world for me. Temporality, as a dimension of the lifeworld, is not disconnected from my sense of self, how I find myself, how I understand others, the world and my place in it. As seen in both Lupinacci (2021) and Zhang (2020), when users interacted with online spaces, the lived temporal dimensions of the ever-present ‘now,’ a present disconnected and fissured from an aimed-at future, and a portal transporting one to a new space illuminate how the user’s world is reconfigured and transformed. This is reflected in the connection we discerned where our participants aimed to return to the world pre-COVID and re-attain the future this past promised. Well-being emerges as a possibility in light of an attempt by the user to knit back the world that was torn asunder. Their confrontation with social media content was experienced as consonant or dissonant in light of the user’s self, who they are aiming to be and the world as they would have it. Social media content is neither soothing nor detrimental on its own but always in reference to the user’s projects for themselves and the world. Well-being is not the outcome of social media use but harbingers of how the user is fairing with respect to their projects.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

“The overall aim of lifeworld research is the description and elucidation of the lived world in a way that expands our understanding of human experience” (Dahlberg et al., 2001, p. 49). Our sample comprised our own students who represent a rather resilient group in that their experiences of being unsettled tended towards resolution, and we can imagine that other participants might be in the midst of the experience and not yet heading towards resolution. Our results are indeed tied to our perspectives and our method is one that explicitly acknowledges the inherent reflexivity of our procedure. The data appear to us in light of our concerns and projects. Our goals as researchers inform what about the data appeared meaningful and how it appeared meaningful to us in light of these concerns. Just as our participants were in the midst of experiencing the pandemic, we too as researchers were experiencing this right alongside them. As experientially close to the phenomenon of interest, this heightened our attunement to the concerns and projects of our participants. Our immersion in the world being described by our participants enabled us to dwell emphatically and illuminate the experiential dimensions of meaning to provide insight into this phenomenon. The validity of this research, as of all qualitative research, is to be understood in light of ‘fidelity’ across the data, the method, and the findings (Levitt et al., 2017).

These female students attended a private religiously affiliated school in the southwestern United States and came from middle to upper middle-class backgrounds. The similar experiences among our participants mean that our sample was homogenous. Pursuing a strategy of heterogeneity for maximum variation (Braun & Clarke, 2022) could possibly generate different insights, particularly by exploring more generally the experience of a person having their worldview threatened. As our findings illustrate, exploring how a person is concerned with and taking up social media meaningfully provides new ways of understanding the relationship between social media and well-being. By emphasizing that social media content, attributes, and affordances are intertwined with a user’s concerns, attitudes, cognitions, and perceptions, we can shift our understanding of well-being from that which is the effect or predictor of social media use to understanding well-being as a way of engaging, that is how a person engages content, including anxiously, depressively, unsettingly. In this view, we can explore how the world is experienced, how users understand themselves, others, time, and their place in the world. How social media can be experienced affirmingly, beneficially, joyfully are fruitful opportunities for future qualitative research. We invite future researchers to quantitatively explore other ways of operationalizing engagement and concerns, particularly using user-related variables, such as prior experience, concern for one’s future, social connectedness, as moderators to continue exploring how social media interacts with well-being in line with DSMM (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013). These person-specific variables capture how people are engaging with and interacting with the platforms, emphasizing active agentic involvement. Operationalizations of communications technology usage should recognize that their value is inseparable from the user’s concerns.

Conclusion

Our data illuminate that regardless of how a person views COVID-19 and its place in their life, being unsettled is marked by calling into question their previous hold on the world and the way things had been and where they are headed. In empathically dwelling with the data, we have gained an appreciation for those on different sides of the debate as we collectively attempt to reconcile and make sense of how the pandemic has changed and continues to shape our worlds. By conducting a phenomenological qualitative study focusing on dimensions of meaning, our study sheds light on and complements the previous literature, particularly illuminating the apparent inconsistencies found in past studies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2024 Brittany Landrum, Gilbert Garza