Distinguishing high engagement from problematic symptoms in Instagram users: Associations with big five personality, psychological distress, and motives in an Italian sample

Vol.18,No.5(2024)

Building on recent findings by Fournier and colleagues (2023), the present study examined the fit of a bi-dimensional model of problematic Instagram use, distinguishing between non-pathological high engagement and problematic symptoms mirroring addictive tendencies. A sample of 696 Italian adults completed an online survey assessing problematic Instagram use, personality traits, psychological distress, usage motives for Instagram use, and Instagram usage metrics. Confirmatory factor analysis supported the bi-dimensional model, with high engagement (salience and tolerance) and problematic symptoms (relapse, withdrawal, conflict, and mood modification) as distinct factors. Neuroticism, depression, emotional dysregulation, loneliness, and FoMO and the diversion motive were more strongly correlated with problematic symptoms. In turn, social interaction, documentation, and self-promotion were more associated with high engagement. Frequency of sharing posts and stories were also more strongly correlated with high engagement. These findings highlight the importance of distinguishing between high engagement and addiction-like symptoms in understanding problematic Instagram use and inform the development of targeted interventions.

problematic Instagram use; emotional dysregulation; depression; FoMO; factor analysis

Davide Marengo

Department of Psychology, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

Davide Marengo is assistant professor of psychometrics at the Department of Psychology, University of Turin, Italy. His main interest is in the area of psychoinformatics, and specifically in the identification of digital markers of individual differences in personality and well-being in digital traces of computer mediated communication. He also has interest in research on the predictors and consequence of social media addiction in adolescence and young adulthood.

Alessandro Mignogna

Department of Psychology, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

Alessandro Mignogna is a psychology graduate with a keen interest in the association between use of media technology and mental health and addiction outcomes.

Jon D. Elhai

Department of Psychology, University of Toledo, Toledo, Ohio, USA; Department of Psychiatry, University of Toledo, Toledo, Ohio, USA

Jon D. Elhai is Distinguished Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at the University of Toledo in Toledo, Ohio, USA. He has an area of research on posttraumatic stress disorder, studying the disorder’s underlying symptom dimensions and relations with cognitive coping processes and externalizing behaviors. He also has a program of research on cyberpsychology and internet addictions, examining problematic internet and smartphone use, and the fear of missing out on rewarding experiences (FOMO).

Michele Settanni

Department of Psychology, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

Michele Settanni is professor of Psychometrics at the University of Turin in Turin, Italy. His main interest is in the assessment of symptoms of psychological distress and well-being based on questionnaire data as well as indicators of technology use. He also has interest in research on the predictors and consequence of social media addiction in adolescence and young adulthood.

Abravanel, B. T., & Sinha, R. (2015). Emotion dysregulation mediates the relationship between lifetime cumulative adversity and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 61, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.11.012

Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517

Ballarotto, G., Marzilli, E., Cerniglia, L., Cimino, S., & Tambelli, R. (2021). How does psychological distress due to the COVID-19 pandemic impact on internet addiction and Instagram addiction in emerging adults? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), Article 11382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111382

Ballarotto, G., Volpi, B., & Tambelli, R. (2021). Adolescent attachment to parents and peers and the use of Instagram: The mediation role of psychopathological risk. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), Article 3965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083965

Balta, S., Emirtekin, E., Kircaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Neuroticism, trait fear of missing out, and phubbing: The mediating role of state fear of missing out and problematic Instagram use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18, 628–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9959-8

Boffo, M., Mannarini, S., & Munari, C. (2012). Exploratory structure equation modeling of the UCLA Loneliness Scale: A contribution to the Italian adaptation. TPM-Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 19(4), 345–363. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2012-33845-007

Bottaro, R., Valenti, G. D., & Faraci, P. (2023). Assessment of an epidemic urgency: Psychometric evidence for the UCLA Loneliness Scale. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 2843–2855. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S406523

Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders: An interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 252–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033

Casale, S., & Fioravanti, G. (2020). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Fear of Missing Out Scale in emerging adults and adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 102, Article 106179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106179

Cunningham, S., Hudson, C. C., & Harkness, K. (2021). Social media and depression symptoms: A meta-analysis. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49, 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00715-7

We are social. Digital 2021. https://wearesocial.com/digital-2021

Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., Alghraibeh, A. M., Alafnan, A. A., Aldraiweesh, A. A., & Hall, B. J. (2018). Fear of missing out: Testing relationships with negative affectivity, online social engagement, and problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.020

Fabris, M. A., Marengo, D., Longobardi, C., & Settanni, M. (2020). Investigating the links between fear of missing out, social media addiction, and emotional symptoms in adolescence: The role of stress associated with neglect and negative reactions on social media. Addictive Behaviors, 106, Article 106364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106364

Fournier, L., Schimmenti, A., Musetti, A., Boursier, V., Flayelle, M., Cataldo, I., Starcevic, V., & Billieux, J. (2023). Deconstructing the components model of addiction: An illustration through “addictive” use of social media. Addictive Behaviors, 143, Article 107694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107694

Giromini, L., Velotti, P., de Campora, G., Bonalume, L., & Cesare Zavattini, G. (2012). Cultural adaptation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale: Reliability and validity of an Italian version. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(9), 989–1007. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21876

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Social networking addiction: An overview of preliminary findings. In K. P. Rosenberg & L. C. Feder (Eds.), Behavioral addictions (pp. 119–141). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407724-9.00006-9

Guido, G., Peluso, A. M., Capestro, M., & Miglietta, M. (2015). An Italian version of the 10-item Big Five Inventory: An application to hedonic and utilitarian shopping values. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.053

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang, C. (2022). A meta-analysis of the problematic social media use and mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 68(1), 12–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020978434

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574

Kaufman, E. A., Xia, M., Fosco, G., Yaptangco, M., Skidmore, C. R., & Crowell, S. E. (2016). The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Short Form (DERS-SF): Validation and replication in adolescent and adult samples. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(3), 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9529-3

Kırcaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Problematic Instagram use: The role of perceived feeling of presence and escapism. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17, 909–921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9895-7

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), Article 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030311

Mazzotti, E., Fassone, G., Picardi, A., Sagoni, E., Ramieri, L., Lega, I., Camaioni, D., Abeni, D., & Pasquini, P. (2003). II Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) per lo screening dei disturbi psichiatrici: Uno studio di validazione nei confronti della Intervista Clinica Strutturata per il DSM-IV asse I (SCID-I) [The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) for the screening of psychiatric disorders: A validation study versus the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV axis I (SCID-I)]. Italian Journal of Psychopathology, 9(3), 235–242. https://old.jpsychopathol.it/article/il-patient-health-questionnaire-phq-per-lo-screening-dei-disturbi-psichiatrici-uno-studio-di-validazione-nei-confronti-della-intervista-clinica-strutturata-per-il-dsm-iv-asse-i-scid-i/

Meynadier, J., Malouff, J. M., Schutte, N. S., & Loi, N. M. (2024). Meta-analysis of associations between five-factor personality traits and problematic social media use. Current Psychology, 43, 23016–23035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06052-y

Monacis, L., de Palo, V., Griffiths, M. D., & Sinatra, M. (2017). Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(2), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.023

Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Whaite, E. O., Lin, L. Y., Rosen, D., Colditz, J. B., Radovic, A., & Miller, E. (2017). Social media use and perceived social isolation among young adults in the US. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.010

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001.

Rammstedt, B., Kemper, C. J., Klein, M. C., Beierlein, C., & Kovaleva, A. (2013). A short scale for assessing the big five dimensions of personality: 10 Item Big Five Inventory (BFI-10). methods, data, analyses, 7(2), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.12758/mda.2013.013

Sheldon, P., & Newman, M. (2019). Instagram and American teens: Understanding motives for its use and relationship to excessive reassurance-seeking and interpersonal rejection. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 8(1), 1–16. https://thejsms.org/index.php/JSMS/article/view/423

Sheskin, D. J. (2004). Handbook of parametric and nonparametric statistical procedures (3rd ed.). Chapman & Hall/CRC.

Sun, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2021). A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addictive Behaviors, 114, Article 106699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106699

Young, K. S., & Brand, M. (2017). Merging theoretical models and therapy approaches in the context of internet gaming disorder: A personal perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 289710. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01853

Authors’ Contribution

Davide Marengo: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, formal analysis, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft. Alessandro Mignogna: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft. Jon D. Elhai: methodology, validation, writing—review & editing. Michele Settanni: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, validation, project administration.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

July 26, 2022

Revisions received:

March 28, 2023

December 17, 2023

May 28, 2024

September 13, 2024

Accepted for publication:

September 20, 2024

Editor in charge:

Maèva Flayelle

Introduction

The rapid proliferation of social media platforms has spurred extensive research into the behavioral patterns associated with their use, particularly concerning problematic usage behaviors that might mirror addiction. Problematic social media use encompasses both excessive and compulsive use of social media that interferes with an individual’s daily life, productivity, relationships, and overall well-being and may elicit addiction-like symptoms (Griffiths et al., 2014; Kuss & Griffiths, 2017). There is an overlap in the literature between the terms “problematic social media use” and “social media addiction” or “addictive social media use,” such that these terms are often considered interchangeable (Sun & Zhang, 2021). Due to the lack of an official clinical diagnosis of social media addiction and ongoing debate on the nature of the construct itself (Fournier et al., 2023), we refrain from using “addiction” terminology and instead refer to problematic social media use.

In a recent study Fournier and colleagues (2023) critically evaluated the validity of the components model in the context of behavioral addictions, specifically focusing on problematic social media use as assessed using the Bergen Social Media Addiction scale (Andreassen et al., 2012; Monacis et al., 2017). Their findings suggested that not all components traditionally associated with addiction may be central to behavioral addictions, highlighting the potential conflation of central and peripheral features within psychometric assessments derived from this model. The study by Fournier and colleagues underscores the necessity of re-examining the psychometric instruments used to assess behavioral addictions to avoid pathologizing non-pathological behaviors.

The present study aims to examine the fit of the model identified by Fournier and colleagues to an adaptation of the Bergen Social Media Addiction scale for the assessment of problematic Instagram usage behaviors and symptoms. Focusing on Instagram is particularly relevant as it is one of the most popular social media platforms globally, especially among young adults, making it a critical context for studying social media behaviors (We are social, 2021). In keeping with Fournier and colleagues (2023), we compare a traditional one-factor model, which has shown some support in the literature (e.g., Ballarotto, Marzilli, et al., 2021; Ballarotto, Volpi, & Tambelli, 2021), to a two-factor model distinguishing between two components of problematic social media use: a primary dimension indicating non-pathological high engagement in the platform (i.e., tolerance and salience symptoms) and a secondary dimension reflecting addiction-like symptoms such as relapse, withdrawal, conflict, and mood modification. In order to establish the construct validity of the emerging model, we explore associations with various psychological correlates, including Big Five personality traits (i.e., Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, Openness), depression (PHQ-8; Mazzotti et al., 2003), difficulties in emotional regulation (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004), loneliness (Hughes et al., 2004), Fear of Missing Out (FoMO; Przybylski et al., 2013), and motives for Instagram use (Social Interaction, Documentation, Self-Promotion, Diversion, Creativity; Sheldon & Newman, 2019). These specific measures are examined in alignment with the Interaction of Person–Affect–Cognition–Execution (I-PACE) model (Brand et al., 2016; Young & Brand, 2017), which posits that individual predispositions (such as personality traits and usage motives), affective responses (such as emotional regulation difficulties, depression, loneliness) and cognitive biases (such as FoMO), all contribute to influence problematic internet use behaviors, including those involving social media use. By investigating these associations, the present study aims to shed light on the nuanced psychological landscape that underpins problematic social media use, offering valuable insights for developing more targeted interventions and preventive strategies.

Methods

Procedure and Sample

The sample was recruited online by sharing a link to an online survey implemented via the LimeSurvey web app. Criteria for participation in the research were being an Italian resident with fluency in the Italian language; having an Instagram account and engaging in online activity (either by posting and/or browsing the platform); and Italian legal age (≥18 years old). Online dissemination of the research was implemented using a snowball sampling approach, starting with a seed of six students enrolled in a Master’s Degree course in Psychology; the seed students shared a link to the research page on social media and via online private communication with acquaintances. Data collection took place in January 2021. A sample of 810 participants accessed the online survey and provided online consent to participate in the survey. Upon presenting the online consent form, participants were informed about the anonymity of the study, which was obtained by not recording personal information, including participants’ names, surnames, email addresses, or IP addresses.

Before analyzing the data, we removed responses of N = 100 participants who did not fill in the questionnaire except for the consent form. Additionally, we found N = 14 observations missing data on the study variables: because these observations accounted for only 2% of the sample, listwise deletion was applied and no additional investigation was performed on those missing data. The final sample consisted of 696 adults aged 18 to 63 (M = 25.60, SD = 6.94), of which 62.4% (N = 434) were female and 37.6% (N = 262) male. Regarding education level, 5.3% (N = 37) had at most a middle-school certificate, 39.7% (N = 276) held at most a high school diploma, 35.5% (N = 247) held at most a bachelor’s degree, and 19.5% (N = 136) held a master degree or higher education level. Finally, we collected information on participants’ current relationship status: based on collected responses, 42.0% (N = 294) reported not being in a relationship at the moment (i.e., single, or widow, or divorced), 44.7% (N = 310) reported being in non-cohabiting relationship, and 13.1% (N = 91) reported being involved in a cohabiting relationship (i.e., married or unmarried cohabiting couple).

Instruments

Big Five Personality Traits

We administered the Big Five Inventory—10 item (BFI-10, Rammstedt et al., 2013; adaptation to Italian language by Guido et al., 2015) an ultra-short measure to evaluate Big Five personality, namely agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness; the BFI-10 includes two statements per trait rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). Being based on two items, reliability cannot be assessed using Cronbach’s; however, based on findings by the original study, test-retest correlations over a period of 6 to 8 weeks are expected to vary between r = .65 (Openness) and r = . 79 (Extraversion; Rammsted & John, 2007; Rammsted et al., 2013).

Depressive Symptoms

Participants’ tendencies toward depressive symptoms were assessed by administering the 8-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8), based on the original PHQ-9. The PHQ-8 is validated in the Italian language (Mazzotti et al., 2003) and assesses the frequency of depressive symptoms over the prior 2 weeks based on criteria for a major depressive disorder episode from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), 4th Edition. The PHQ-8 is identical in content and scoring to the PHQ-9 but does not include the item assessing suicidal/self-injury thoughts. For each symptom, participants are asked to rate the frequency of each symptom using the following 4-point rating scale: not at all (value of 0), several days (1), more than half the days (2), and nearly every day (3) over the past 2 weeks. The scale showed good reliability based on Cronbach’s alpha (α = .83).

Emotional Dysregulation

We administered an Italian adaptation of the short form of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS-SF; Giromini et al., 2012; Gratz & Roemer, 2004, Kaufman et al., 2016), consisting of 18 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Almost never) to 5 (Almost always). Example items of the DERS-SF are: When I’m upset, I believe that I will end up feeling depressed, When I’m upset, I feel guilty for feeling that way, and I am confused about how I feel. A total score was computed by taking the average of item responses. The scale showed good reliability (α = .87).

Loneliness

We administered the 3-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al., 2004; Italian adaptation of the full scale by Boffo et al., 2012; validation of the 3-item version by Bottaro et al., 2023). This scale includes three questions that evaluate dimensions of loneliness: relational connectedness, social connectedness, and self-perceived isolation. Participants responded to how often they feel: 1) a lack of companionship, 2) left out, and 3) isolated from others. The response options are: Hardly ever (1), Some of the time (2), and Often (3). The scale showed acceptable reliability (α = .73).

Fear of Missing Out

We administered an Italian version of the FoMO scale (Casale & Fioravanti, 2020; Przybylski et al., 2013). This scale comprises 10 items, each framed as a statement that articulates pervasive feelings of fear, worry, and anxiety about potentially missing out on rewarding experiences that others are having. Sample items include the following: I fear others have more rewarding experiences than me, I get anxious when I don’t know what my friends are up to, and It bothers me when I miss an opportunity to meet up with friends. Items were rated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true of me) to 5 (Extremely true of me). Responses were summed to create a total score. For the purpose of the present study, the score showed good reliability (α = .83).

Motives for Instagram Use

We administered an Italian adaptation of the Motives for Instagram Use scale by Sheldon and Newman (2019), which consists of 18 items providing an assessment of five motives for Instagram use, namely Social Interaction (5 items; example item: To see what other people share), Documentation (4 items; example item: To describe my life through images), Self-Promotion (3 items; example item: To self-promote myself), Diversion (2 items; example item: To escape reality), and Creativity (4 items; example item: To create art). Items are rated using a 5-point scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). To our knowledge, the adaptation presented here has never undergone a psychometric validation to the Italian context. Scores for each motive were computed by averaging item responses; all motive scales showed adequate reliability based on Cronbach’s alpha (Social Interaction: α = .78; Documentation: α = .86; Self-Promotion: α = .62; Diversion: α = .79; Creativity: α = .70).

Instagram Metrics

We asked participants to access the Instagram platform and report the following metrics: average weekly time spent on Instagram in minutes, number of posts and stories they shared over the last week, as well as the number of followers they had and the number of accounts they were following.

Problematic Instagram Use

We also administered an adaptation of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (Andreassen et al., 2012; Monacis et al., 2017), a 6-item self-report questionnaire developed to measure six components of problematic usage of a social media platform: salience (Item: How often have you spent a lot of time thinking about social media or planned use of Instagram?); mood modification (Item: How often during have you used Instagram in order to forget about personal problems?); tolerance (Item: How often during the last year have you felt an urge to use Instagram more and more?); withdrawal (Item: How often have you become restless or troubled if you have been prohibited from using Instagram?); conflict (Item: How often have you used Instagram so much that it has had a negative impact on your job/study); and relapse (Item: How often have you tried to cut down on the use of Instagram without success?). Our adaptation involved asking about Instagram use specifically. Each item is scored on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (Very rarely) to 5 (Very often). A total score can be computed by averaging item responses. Note that the instrument administered in the present study does not coincide with the version validated by Ballarotto, Volpi, and Tambelli (2021), because the aforementioned study was not yet published at the time of implementation of our study.

Results

Model Fit

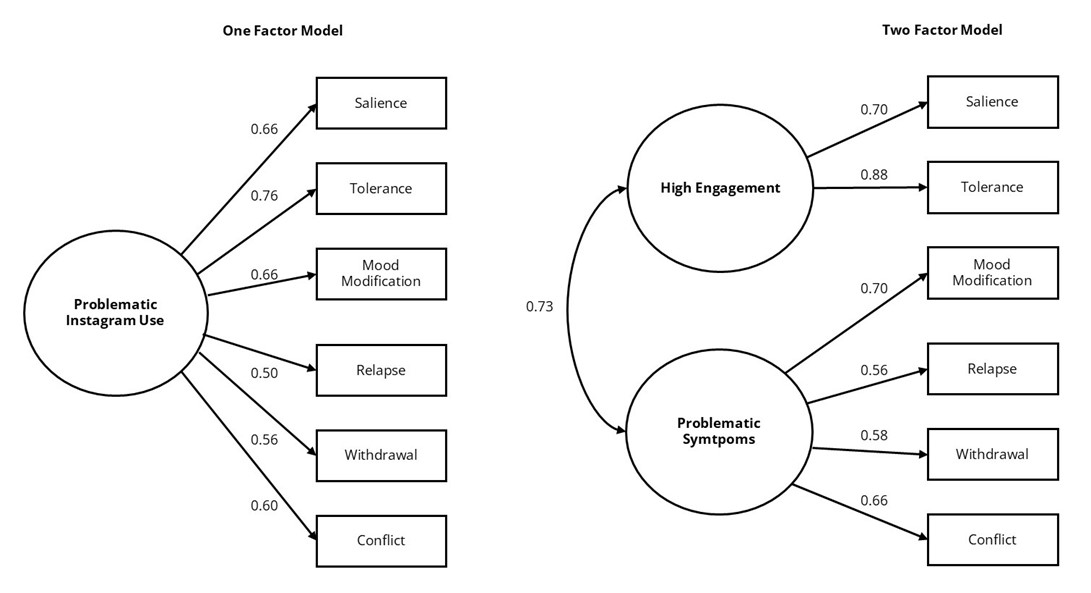

First, we examined the fit of two competing confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models for problematic Instagram use (see Figure 1). Parameter estimation was performed using Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation. In contrast with findings reported by Ballarotto, Volpi and Tambelli (2021), our version of Problematic Instagram use scale showed problematic fit to a one-factor structure confirmatory factor analysis model, χ2 (9) = 113, p < .001, CFI = .91, TLI = .84, RMSEA = .13, AIC = 10,958, BIC = 11,039. We thus explored the fit to the data of an alternative model of problematic social media use as a bi-dimensional construct. In doing this, we follow the model recently proposed by Fournier and colleagues (2023), which distinguishes between a primary dimension comprising the two components of tolerance and salience, and a secondary dimension comprising the four components of mood modification, relapse, withdrawal, and conflict. The first dimension reflects individual differences in non-pathological aspects of social media overuse (salience, tolerance), while the second dimension reflects addiction-like symptoms of social media use, including addiction-like symptoms (i.e., relapse, withdrawal, conflict) and the mood modification symptom. The two-factor model showed good fit to the data, χ2 (8) = 17.2, p = .028, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .04, AIC = 10,864, BIC = 10,951, based on widely accepted criteria (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Additionally, the two dimensions’ scores showed adequate reliability based on McDonald’s omega (ω) coefficient (High engagement: ω = 0.766; Problematic symptoms: ω = 0.721). As noted by Fournier and colleagues (2023), the first dimension does reflect non-pathological tendencies toward high engagement to the platform, while the second dimension is expected to reflect addiction-like symptoms, and thus might show a stronger association with psychological symptoms. In keeping with this reasoning, for the purpose of the present study, we labeled the first dimension “High engagement”, while the second dimension was labeled “Problematic symptoms”. Diagrams for the two models are visualized in Figure 1, which also reports the estimated standardized parameters for loadings and latent correlations.

Figure 1. Diagram for the Tested Confirmatory Factor Analysis Models for Problematic Instagram Use.

Bivariate Associations Between Psychological Variables and Measures of Problematic Instagram Use

Next, we used Spearman correlations to investigate correlations between personality traits, psychological measures, usage motives, and problematic Instagram use measures. For comparison purposes with previous studies, we also report correlations computed with the total score (see Table 1).

Among personality traits, neuroticism shows moderate correlations with the Problematic symptoms score and the total score for problematic Instagram use, and a small correlation with the High engagement score. Other personality traits such as extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness showed small to negligible correlations with the Problematic symptoms score, with the highest being a small negative correlation with Conscientiousness. In turn, Extraversion showed the strongest association with the High engagement score. Affective and psychological distress measures, including PHQ8, DERS, and the loneliness scales demonstrated moderate positive correlations with the Problematic symptoms score and the total score, and small correlation with the High engagement score. FoMO also showed moderate positive correlations with both dimensions. Among motives for Instagram use, diversion showed a strong correlation with both the Problematic symptoms and total scores, and a moderate positive correlation with the High engagement score. Other usage motives such as social interaction, documentation, and self-promotion showed small-to-moderate correlations with the High engagement and the total score, while correlations with Problematic symptoms were positive but small. Creativity showed small correlations all scores.

Finally, we employed Fisher’s z-transformation procedure to test the significance of the difference between correlations with high engagement and problematic symptoms (Sheskin, 2004). Results are reported in the table, indicating in bold those correlations that showed a stronger association with either the Problematic symptoms or High engagement score. Findings highlighted how certain psychological measures, namely neuroticism, conscientiousness, depressive symptoms, emotional dysregulation, FoMO, and the diversion motive showed stronger associations with the Problematic symptoms score than with High engagement score. In turn, extraversion, and the social interaction, self-promotion, documentation motives for Instagram use were more strongly associated with the High engagement score. The latter also showed a stronger association with the number of posts and stories shared on the platform.

Table 1. Correlations Between Personality Psychological Distress Variables, Usage Motives for Instagram,

and Indicators of Problematic Instagram Use.

|

|

Problematic Instagram Use |

||

|

High Engagement |

Problematic Symptoms |

Total score |

|

|

Personality |

|

|

|

|

Extraversion |

.12** |

.01 |

.07 |

|

Agreeableness |

−.09* |

−.10** |

−.11** |

|

Conscientiousness |

−.03 |

−.19** |

−.14** |

|

Neuroticism |

.23** |

.33** |

.33** |

|

Openness |

.05 |

.03 |

.05 |

|

PHQ8 |

.25** |

.38** |

.37** |

|

DERS |

.26** |

.43** |

.41** |

|

FoMO |

.32** |

.40** |

.41** |

|

Loneliness |

.19** |

.35** |

.31** |

|

Usage motives |

|

|

|

|

Social Interaction |

.40** |

.23** |

.34** |

|

Documentation |

.37** |

.23** |

.33** |

|

Self-Promotion |

.38** |

.22** |

.33** |

|

Diversion |

.37** |

.54** |

.53** |

|

Creativity |

.28** |

.21** |

.28** |

|

Instagram metrics |

|

|

|

|

Following |

.21** |

.19** |

.24** |

|

Followers |

.32** |

.27** |

.33** |

|

Number of posts (week) |

.17** |

.05 |

.13** |

|

Number of stories (week) |

.32** |

.19** |

.29** |

|

Time spent on the platform (minutes/day) |

.38** |

.38** |

.43** |

|

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01. Correlations in bold indicate a significant difference in strength of correlation between the High Engagement and Problematic Symptoms scores. |

|||

Discussion

The present study set out to examine the fit of a bi-dimensional model of problematic Instagram use, distinguishing between high engagement and addiction-like symptoms. The results indicate that the bi-dimensional model, which differentiates between non-pathological high engagement (salience and tolerance) and problematic symptoms (relapse, withdrawal, conflict, and mood modification), provides a better fit than a one-factor model. This aligns with the findings of Fournier et al. (2023), who emphasized the importance of separating these dimensions to avoid conflating normal high engagement with pathological use. Fournier et al. (2023) demonstrated that certain components traditionally associated with addiction, such as salience and tolerance, may not necessarily indicate pathological behavior in the context of social media use. Their work calls into question the validity of using these components as central features of behavioral addictions and suggests that current psychometric instruments may pathologize normal levels of engagement. Our findings support this perspective, showing that high engagement and problematic symptoms are distinct, albeit strongly correlated constructs, showing different patterns of associations with psychological correlates, usage motives, and Instagram usage metrics. Indeed, results of correlational analyses performed in present study to determine the construct validity of the two-dimensional model of problematic Instagram use highlighted that association with several psychological measures, usage motives, and Instagram usage metrics differed across the two dimensions. More specifically, the results aligned with those reported by Fournier and colleagues (2023), indicating that measures theoretically linked to psychopathological symptoms were more strongly associated with problematic Instagram use symptoms than with high engagement behaviors. In showing this, the findings also aligned with the I-PACE model, underscoring how the correlates and potential drivers of problematic social media use may span multiple domains, namely personal, affective, and cognitive factors.

Regarding personality, neuroticism showed a moderate correlation with problematic symptoms, indicating that individuals high in neuroticism are more likely to exhibit problematic Instagram use symptoms. This is consistent with prior research linking neuroticism to various forms of addictive behaviors (Balta et al., 2020). Of note, neuroticism also showed a positive correlation with high engagement in the platform, but strength of association was significantly lower. Other personality traits, such as extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness, had smaller correlations, with conscientiousness showing a negative association with problematic symptoms, suggesting that higher conscientiousness may be a protective factor against problematic use.

Depression, as measured by the PHQ-8, was moderately associated with problematic symptoms, which is in line with literature (Cunningham et al., 2021). Difficulties in emotional regulation were also moderately correlated with problematic symptoms, suggesting that individuals who struggle with regulating their emotions are more likely to develop addiction-like behaviors on social media (Abravanel & Sinha, 2015). Loneliness showed a similar pattern, aligning with findings indicating perceived social isolation is positively related to problematic social media use (Primack et al., 2017). FoMO exhibited moderate correlations with both problematic symptoms and high engagement, but the correlation was stronger with problematic symptoms. This aligns with previous findings that FoMO is a significant driver of problematic smartphone and social media use (Elhai et al., 2018; Fabris et al., 2020).

Usage motives such as diversion showed moderate-to-strong correlations with problematic symptoms and high engagement, although the association with problematic symptoms was stronger. Overall, this is compatible with findings indicating that using Instagram for escapism is a key factor in problematic use (Sheldon & Newman, 2019). Social interaction, documentation, and self-promotion were more strongly associated with high engagement, suggesting these motives drive frequent use without necessarily leading to addiction-like symptoms. Finally, the frequency of posting and sharing stories also correlated with high engagement but showed a weaker association with problematic symptoms. This indicates that active content creation is more closely related to high engagement behaviors rather than addiction-like symptoms. Users who frequently post and share stories may do so for reasons such as social interaction and self-promotion, which align with high engagement usage motives (Kırcaburun & Griffiths, 2019).

Overall, it is worthy to note that correlations found between problematic Instagram use symptoms and the many variables, including measures of personality traits and psychological distress, were mostly small to moderate in magnitude. This is consistent with recent meta-analyses on the subject. For example, Huang (2022) and Meynadier et al. (2024) have demonstrated that the associations between problematic social media use and mental health indicators, as well as personality traits, tend to fall within a small-to-moderate range. These findings suggest that while there are consistent relationships between problematic social media use and psychological factors, they are often not particularly strong. In this context, we recommend further investigation into potential moderating factors that may strengthen or weaken the relationship between problematic social media use and psychological outcomes, such as different usage patterns, types of content consumed, and individual susceptibility factors.

While the present study provides valuable insights into the nature of problematic Instagram use, several limitations should be considered. The study’s reliance on a cross-sectional design implies that our analyses are inherently correlational, thus limiting our ability to examine potential bidirectional effects among the study variables. Longitudinal studies are needed to more fully understand the direction and temporal dynamics of these associations. Additionally, the reliance on self-report questionnaires introduces the potential for response biases, such as social desirability bias and recall bias. Future research could benefit from incorporating objective measures of Instagram use, such as digital traces or usage logs, to complement self-reported data. The sample consisted predominantly of young adults with a higher level of education, which may have limited the generalizability of the findings to other age groups and educational backgrounds. The use of a snowball sampling method may have introduced selection bias, as participants who are more active on social media were likely overrepresented. Random sampling methods would enhance the representativeness of the sample. Finally, the study was performed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have influenced social media usage patterns due to lockdowns and increased online activity (We are social, 2021).

Implications and Future Research

These findings have important implications for understanding and addressing problematic social media use. By distinguishing between high engagement and addiction-like symptoms, interventions can be more precisely targeted. For example, strategies to manage FoMO and improve emotional regulation might be particularly effective for those exhibiting addiction-like symptoms.

Future research should continue to explore these dimensions across different social media platforms and cultural contexts to validate the generalizability of these findings. Additionally, longitudinal studies could provide deeper insights into how these psychological correlates influence the development and persistence of problematic social media use symptoms over time.

In conclusion, our study supports the bi-dimensional model of problematic social media use and highlights the importance of considering individual differences in personality, emotional regulation, and motives for use. These insights can guide the development of more effective interventions to promote healthier social media use.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2024 Davide Marengo, Alessandro Mignogna, Jon D. Elhai, Michele Settanni