The association of motives with problematic smartphone use: A systematic review

Vol.17,No.1(2023)

Motives for smartphone use may be key factors underlying problematic smartphone use (PSU). However, no study has reviewed the literature investigating the association of motives with PSU. As such, we conducted a systematic review to: (a) determine which smartphone use motives were associated with PSU; and (b) examine the potential indirect and moderating effects of motives in the relationship of psychosocial factors with PSU. We identified 44 studies suitable for inclusion in our systematic review. There was extensive heterogeneity in smartphone use motives measures across the studies, including 55 different labels applied to individual motives dimensions. Categorisation of these motives based on their definitions and item content identified seven motives that were broadly assessed across the included studies. Motives which reflected smartphone use for mood regulation, enhancement, self-identity/conformity, passing time, socialising, and safety were generally positively associated with PSU. There were indirect effects of depression, anxiety, and transdiagnostic factors linked to both psychopathologies on PSU via motives, particularly those reflecting mood regulation. Stress and anxiety variously interacted with pass-time, social, and a composite of enhancement and mood regulation motives to predict PSU. However, the heterogeneity in the measurement of smartphone use motives made it difficult to determine which motives were most robustly associated with PSU. This highlights the need for a valid and comprehensive smartphone use motives measure.

problematic smartphone use; smartphone addiction; smartphone use disorder; motives; compensatory internet use theory; pathway model; systematic review

Beau Mostyn Sullivan

Discipline of Psychology, University of Canberra, Canberra, Australia

Beau Mostyn Sullivan is a PhD candidate (Clinical Psychology) at the University of Canberra. His research interests include aetiological mechanisms underlying problematic technology use, particularly personality traits, psychopathology, and motives.

Amanda M. George

Discipline of Psychology, University of Canberra, Canberra, Australia

Amanda M. George is an Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Canberra on Ngunnawal Country, Australia. Her research focuses on risk-taking behaviours among young adults. She has a particular interest in alcohol use/consequences, risky driving practices and problematic smartphone use.

Agu, E., Pedersen, P., Strong, D., Tulu, B., He, Q., Wang, L., & Li, Y. (2013). The smartphone as a medical device: Assessing enablers, benefits and challenges. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sensing, Communications and Networking (SECON) (pp. 76–80). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/SAHCN.2013.6644964

AlBarashdi, H. S., & Bouazza, A. (2019). Smartphone usage, gratifications, and addiction: A mixed-methods research. In X. Xu (Ed.), Impacts of mobile use and experience on contemporary society (pp. 86–111). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-7885-7.ch006

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Augner, C., Vlasak, T., Aichhorn, W., & Barth, A. (2022). Tackling the ‘digital pandemic’: The effectiveness of psychological intervention strategies in problematic internet and smartphone use—A meta-analysis. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 56(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674211042793

Bachrach, R. L., Merrill, J. E., Bytschkow, K. M., & Read, J. P. (2012). Development and initial validation of a measure of motives for pregaming in college students. Addictive Behaviors, 37(9), 1038–1045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.013

Baggio, S., Starcevic, V., Studer, J., Simon, O., Gainsbury, S. M., Gmel, G., & Billieux, J. (2018). Technology-mediated addictive behaviors constitute a spectrum of related yet distinct conditions: A network perspective. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 32(5), 564–572. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000379

Bianchi, A., & Phillips, J. G. (2005). Psychological predictors of problem mobile phone use. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 8(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2005.8.39

Billieux, J., Maurage, P., Lopez-Fernandez, O., Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Current Addiction Reports, 2(2), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y

Brand, M., Wegmann, E., Stark, R., Müller, A., Wölfling, K., Robbins, T. W., & Potenza, M. N. (2019). The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 104, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.032

Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 252–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033

Busch, P. A., & McCarthy, S. (2021). Antecedents and consequences of problematic smartphone use: A systematic literature review of an emerging research area. Computers in Human Behavior, 114, Article 106414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106414

Canale, N., Moretta, T., Pancani, L., Buodo, G., Vieno, A., Dalmaso, M., & Billieux, J. (2021). A test of the pathway model of problematic smartphone use. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10(1), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00103

Casale, S., Fioravanti, G., Gioia, F., Redditi, E., & Spada, M. (2022). Fear of missing out and fear of not being up to date: Investigating different pathways towards social and process problematic smartphone use. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03368-5

Casale, S., Fioravanti, G., & Spada, M. M. (2021). Modelling the contribution of metacognitions and expectancies to problematic smartphone use. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10(3), 788–798. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00066

Chang, K., Li, X., Zhang, L., & Zhang, H. (2022). A double-edged impact of social smartphone use on smartphone addiction: A parallel mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 808192. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.808192

Chen, A., & Roberts, N. (2019). Connecting personality traits to social networking site addiction: The mediating role of motives. Information Technology & People, 33(2), 633–656. https://doi.org/10.1108/itp-01-2019-0025

Chen, C., Zhang, K. Z. K., Gong, X., & Lee, M. (2019). Dual mechanisms of reinforcement reward and habit in driving smartphone addiction. Internet Research, 29(6), 1551–1570. https://doi.org/10.1108/intr-11-2018-0489

Chen, C., Zhang, K. Z. K., Gong, X., Zhao, S. J., Lee, M. K. O., & Liang, L. (2017). Examining the effects of motives and gender differences on smartphone addiction. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 891–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.002

Chen, H. T., & Kim, Y. (2013). Problematic use of social network sites: The interactive relationship between gratifications sought and privacy concerns. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(11), 806–812. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0608

Chen, I. H., Pakpour, A. H., Leung, H., Potenza, M. N., Su, J.-A., Lin, C.-Y., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Comparing generalized and specific problematic smartphone/internet use: Longitudinal relationships between smartphone application-based addiction and social media addiction and psychological distress. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(2), 410–419. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00023

Chen, Y., Li, R., & Liu, X. (2021). Problematic smartphone usage among Chinese adolescents: Role of social/non-social loneliness, use motivations, and grade difference. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02458-0

Cheng, Y., & Meng, J. (2021). The association between depression and problematic smartphone behaviors through smartphone use in a clinical sample. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(3), 441–453. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.258

Chóliz, M. (2012). Mobile-phone addiction in adolescence: The Test of Mobile Phone Dependence (TMD). Progress in Health Sciences, 2(1), 33–44. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284690452_Mobile-phone_addiction_in_adolescence_The_Test_of_Mobile_Phone_Dependence_TMD

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis.

Cooper, M. L. (1994). Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 6(2), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117

Cooper, M. L., Kuntsche, E., Levitt, A., Barber, L. L., & Wolf, S. (2015). Motivational models of substance use: A review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco. In K. J. Sher (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of substance use disorder: Volume 1 (pp. 375–421). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199381678.013.017

Cougle, J. R., Fitch, K. E., Fincham, F. D., Riccardi, C. J., Keough, M. E., & Timpano, K. R. (2012). Excessive reassurance seeking and anxiety pathology: Tests of incremental associations and directionality. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(1), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.10.001

Cox, W. M., & Klinger, E. (1988). A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(2), 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.168

Cox, W. M., & Klinger, E. (2004). A motivational model of alcohol use: Determinants of use and change. In W. M. Cox & E. Klinger (Eds.), Handbook of motivational counseling: concepts, approaches, and assessment. John Wiley & Sons.

Csathó, Á., & Birkás, B. (2018). Early-life stressors, personality development, and fast life strategies: An evolutionary perspective on malevolent personality features. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 305. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00305

Davazdahemami, B., Hammer, B., & Soror, A. (2016). Addiction to mobile phone or addiction through mobile phone? In 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 1467–1476). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2016.186.

Deloitte. (2018). Global Mobile Consumer Survey: US edition. https://www2.deloitte.com/tr/en/pages/technology-media-and-telecommunications/articles/global-mobile-consumer-survey-us-edition.html

Deloitte. (2019a). Global Mobile Consumer Survey 2019: Australian cut. https://content.deloitte.com.au/mobile-consumer-survey-2019

Deloitte. (2019b). Global Mobile Consumer Survey 2019: UK cut. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/technology-media-telecommunications/deloitte-uk-plateauing-at-the-peak-the-state-of-the-smartphone.pdf

De-Sola Gutiérrez, J., Rodríguez de Fonseca, F., & Rubio, G. (2016). Cell-phone addiction: A review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 7, Article 175. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00175

Elhai, J. D., Dvorak, R. D., Levine, J. C., & Hall, B. J. (2017). Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. Journal of Affective Disorders, 207, 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.030

Elhai, J. D., Gallinari, E. F., Rozgonjuk, D., & Yang, H. (2020). Depression, anxiety and fear of missing out as correlates of social, non-social and problematic smartphone use. Addictive Behaviors, 105, Article 106335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106335

Elhai, J. D., Hall, B. J., Levine, J. C., & Dvorak, R. D. (2017). Types of smartphone usage and relations with problematic smartphone behaviors: The role of content consumption vs. social smartphone use. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 11(2), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.5817/cp2017-2-3

Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., Alghraibeh, A. M., Alafnan, A. A., Aldraiweesh, A. A., & Hall, B. J. (2018). Fear of missing out: Testing relationships with negative affectivity, online social engagement, and problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.020

Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., Dvorak, R. D., & Hall, B. J. (2017). Non-social features of smartphone use are most related to depression, anxiety and problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.023

Elhai, J. D., Yang, H., Dempsey, A. E., & Montag, C. (2020). Rumination and negative smartphone use expectancies are associated with greater levels of problematic smartphone use: A latent class analysis. Psychiatry Research, 285, Article 112845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112845

Elhai, J. D., Yang, H., & Montag, C. (2019). Cognitive- and emotion-related dysfunctional coping processes: Transdiagnostic mechanisms explaining depression and anxiety’s relations with problematic smartphone use. Current Addiction Reports, 6(4), 410–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00260-4

Farhat, K., Aslam, W., Arif, I., & Ahmed, Z. (2021). Does the dark side of personality traits explain compulsive smartphone use of higher education students? The interaction effect of dark side of personality with desirability and feasibility of smartphone use. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, 11(1), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/22779752211000479

Foerster, M., Roser, K., Schoeni, A., & Röösli, M. (2015). Problematic mobile phone use in adolescents: Derivation of a short scale MPPUS-10. International Journal of Public Health, 60(2), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-015-0660-4

French, D., McKillop, D., & Stewart, E. (2020). The effectiveness of smartphone apps in improving financial capability. The European Journal of Finance, 26(4–5), 302–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847x.2019.1639526

Frost, R. L., & Rickwood, D. J. (2017). A systematic review of the mental health outcomes associated with Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 576–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.001

Fu, X., Liu, J., Liu, R.-D., Ding, Y., Wang, J., Zhen, R., & Jin, F. (2020). Parental monitoring and adolescent problematic mobile phone use: The mediating role of escape motivation and the moderating role of shyness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), Article 1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051487

Fullwood, C., Quinn, S., Kaye, L. K., & Redding, C. (2017). My virtual friend: A qualitative analysis of the attitudes and experiences of smartphone users: Implications for smartphone attachment. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.029

Gentina, E., & Rowe, F. (2020). Effects of materialism on problematic smartphone dependency among adolescents: The role of gender and gratifications. International Journal of Information Management, 54(2), Article 102134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102134

George, A. M., Zamboanga, B. L., Martin, J. L., & Olthuis, J. V. (2018). Examining the factor structure of the Motives for Playing Drinking Games measure among Australian university students. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37(6), 782–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12830

Golubchik, P., Manor, I., Shoval, G., & Weizman, A. (2020). Levels of proneness to boredom in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on and off methylphenidate treatment. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 30(3), 173–176. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2019.0151

Griffiths, M. D. (2021). Internet use disorders: What's new and what's not? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(4), 934–937. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00072

Hallauer, C. J., Rooney, E. A., Billieux, J., Hall, B. J., & Elhai, J. (2022). Mindfulness mediates relations between anxiety with problematic smartphone use severity. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 16(1), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.5817/cp2022-1-4

Han, J., & Hur, G.-H. (2004). Construction and validation of mobile phone addiction scale. Korean Journal of Journalism & Communication Studies, 48(6), 138–165. https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE00957680

Hao, Z., Jin, L., Huang, J., & Wu, H. (2022). Stress, academic burnout, smartphone use types and problematic smartphone use: The moderation effects of resilience. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 150, 324–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.03.019

Harris, B., Regan, T., Schueler, J., & Fields, S. A. (2020). Problematic mobile phone and smartphone use scales: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 672. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00672

Hind, J., & Sibbald, S. L. (2014). Smartphone applications for mental health—A rapid review. Western Undergraduate Research Journal: Health and Natural Sciences, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.5206/wurjhns.2014-15.16

Horwood, S., & Anglim, J. (2018). Personality and problematic smartphone use: A facet-level analysis using the five factor model and HEXACO frameworks. Computers in Human Behavior, 85, 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.013

Horwood, S., & Anglim, J. (2019). Problematic smartphone usage and subjective and psychological well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.02.028

Horwood, S., Anglim, J., & Mallawaarachchi, S. R. (2021). Problematic smartphone use in a large nationally representative sample: Age, reporting biases, and technology concerns. Computers in Human Behavior, 122, Article 106848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106848

Hwang, Y., & Park, N. (2015). Adolescents’ characteristics and motives in predicting problematic mobile phone use. International Telecommunications Policy Review, 22(2), 43–66. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2635956

Jiang, X., Lu, Y., Hong, Y., Zhang, Y., & Chen, L. (2022). A network comparison of motives behind online sexual activities and problematic pornography use during the COVID-19 outbreak and the post-pandemic period. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), Article 5870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105870

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). Utilization of mass communication by the individual. In J. G. Blumler & E. Katz (Eds.), The uses of mass communications: Current perspectives on gratifications research (pp. 19–32). Sage.

Khang, H., Kim, J. K., & Kim, Y. (2013). Self-traits and motivations as antecedents of digital media flow and addiction: The internet, mobile phones, and video games. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2416–2424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.027

Kim, D., Lee, Y., Lee, J., Nam, J. K., & Chung, Y. (2014). Development of Korean smartphone addiction proneness scale for youth. PloS One, 9(5), Article e97920. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097920

Kim, J.-H. (2017). Smartphone-mediated communication vs. face-to-face interaction: Two routes to social support and problematic use of smartphone. Computers in Human Behavior, 67, 282–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.004

Kim, J.-H., Seo, M., & David, P. (2015). Alleviating depression only to become problematic mobile phone users: Can face-to-face communication be the antidote? Computers in Human Behavior, 51(Part A), 440–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.030

Kuntsche, E., Knibbe, R., Gmel, G., & Engels, R. (2005). Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(7), 841–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002

Kuntsche, E., Wiers, R. W., Janssen, T., & Gmel, G. (2010). Same wording, distinct concepts? Testing differences between expectancies and motives in a mediation model of alcohol outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18(5), 436–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019724

Kwon, M., Kim, D.-J., Cho, H., & Yang, S. (2013). The Smartphone Addiction Scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PloS One, 8(12), Article e83558. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083558

Kwon, M., Lee, J.-Y., Won, W.-Y., Park, J.-W., Min, J.-A., Hahn, C., Gu, X., Choi, J.-H., & Kim, D.-J. (2013). Development and validation of a Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS). PloS One, 8(2), Article e56936. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056936

Lee, C., & Lee, S.-J. (2017). Prevalence and predictors of smartphone addiction proneness among Korean adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 77, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.04.002

Leung, L. (2008). Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. Journal of Children and Media, 2(2), 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482790802078565

Leung, L., & Wei, R. (2000). More than just talk on the move: Uses and gratifications of the cellular phone. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 77(2), 308–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900007700206

Li, J., Zhan, D., Zhou, Y., & Gao, X. (2021). Loneliness and problematic mobile phone use among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of escape motivation and self-control. Addictive Behaviors, 118, Article 106857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106857

Lin, Y.-H., Fang, C.-H., & Hsu, C.-L. (2014). Determining uses and gratifications for mobile phone apps. In J. J. Park, Y. Pan, C.-S. Kim, & Y. Yang (Eds.), Lecture notes in electrical engineering: Future information technology (Vol. 309, pp. 661–668). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-55038-6_103

Malkovsky, E., Merrifield, C., Goldberg, Y., & Danckert, J. (2012). Exploring the relationship between boredom and sustained attention. Experimental Brain Research, 221(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-012-3147-z

Männikkö, N., Billieux, J., Nordström, T., Koivisto, K., & Kääriäinen, M. (2017). Problematic gaming behaviour in Finnish adolescents and young adults: Relation to game genres, gaming motives and self-awareness of problematic use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15(2), 324–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-016-9726-7

Melodia, F., Canale, N., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). The role of avoidance coping and escape motives in problematic online gaming: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(2), 996–1022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00422-w

Meng, H., Cao, H., Hao, R., Zhou, N., Liang, Y., Wu, L., Jiang, L., Ma, R., Li, B., Deng, L., Lin, Z., Lin, X., & Zhang, J. (2020). Smartphone use motivation and problematic smartphone use in a national representative sample of Chinese adolescents: The mediating roles of smartphone use time for various activities. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(1), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00004

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L. A., & PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Montag, C., Wegmann, E., Sariyska, R., Demetrovics, Z., & Brand, M. (2021). How to overcome taxonomical problems in the study of internet use disorders and what to do with “smartphone addiction”? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(4), 908–914. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.59

Nabilla, S. P., Christia, M., & Dannisworo, C. A. (2019). The relationship between boredom proneness and sensation seeking among adolescent and adult former drug users. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 229, 420–443. https://doi.org/10.2991/iciap-18.2019.35

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2014). Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort

Paek, K.-S. (2019). The factors related to the smartphone addiction of undergraduate students. Medico Legal Update, 19(1), 732–737. https://doi.org/10.37506/mlu.v19i1.1007

Panova, T., & Carbonell, X. (2018). Is smartphone addiction really an addiction? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 252–259. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.49

Park, N., Kim, Y.-C., Shon, H. Y., & Shim, H. (2013). Factors influencing smartphone use and dependency in South Korea. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1763–1770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.008

Park, N., & Lee, H. (2014). Nature of youth smartphone addiction in Korea: Diverse dimensions of smartphone use and individual traits. Journal of Communication Research, 51(1), 100–132. https://doi.org/10.22174/jcr.2014.51.1.100

Pivetta, E., Harkin, L., Billieux, J., Kanjo, E., & Kuss, D. J. (2019). Problematic smartphone use: An empirically validated model. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.06.013

Rozgonjuk, D., Elhai, J. D., Täht, K., Vassil, K., Levine, J. C., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2019). Non-social smartphone use mediates the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and problematic smartphone use: Evidence from a repeated-measures study. Computers in Human Behavior, 96, 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.02.013

Rubin, A. M. (2002). The uses-and-gratifications perspective of media effects. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 525–548). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Sever, M., & Özdemir, S. (2022). Stress and entertainment motivation are related to problematic smartphone use: Fear of missing out as a mediator. Addicta: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 9(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.5152/ADDICTA.2021.21067

Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., & Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ, 349, Article g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

Shen, X., & Wang, J.-L. (2019). Loneliness and excessive smartphone use among Chinese college students: Moderated mediation effect of perceived stress and motivation. Computers in Human Behavior, 95, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.012

Shen, X., Wang, H.-Z., Rost, D. H., Gaskin, J., & Wang, J.-L. (2021). State anxiety moderates the association between motivations and excessive smartphone use. Current Psychology, 40(4), 1937–1945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-0127-5

Song, I., Larose, R., Eastin, M. S., & Lin, C. A. (2004). Internet gratifications and internet addiction: On the uses and abuses of new media. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(4), 384–394. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2004.7.384

Starcevic, V., King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Schimmenti, A., Castro-Calvo, J., Giardina, A., & Billieux, J. (2021). “Diagnostic inflation” will not resolve taxonomical problems in the study of addictive online behaviours. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(4), 915–919. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00083

Su, S., Pan, T.-T., Liu, Q.-X., Chen, X.-W., Wang, Y.-J., & Li, M.-Y. (2014). Development of the Smartphone Addiction Scale for college students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 28(5), 392–397. http://caod.oriprobe.com/articles/41739378/Development_of_the_Smartphone_Addiction_Scale_for_College_Students.htm

Sundar, S. S., & Limperos, A. M. (2013). Uses and grats 2.0: New gratifications for new media. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 57(4), 504–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2013.845827

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., Bolle, C. L., Hegner, S. M., & Kommers, P. A. M. (2015). Modeling habitual and addictive smartphone behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.039

Vanden Abeele, M. M. (2016). Mobile lifestyles: Conceptualizing heterogeneity in mobile youth culture. New Media & Society, 18(6), 908–926. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814551349

Vezzoli, M., Zogmaister, C., & Coen, S. (2021). Love, desire, and problematic behaviors: Exploring young adults’ smartphone use from a uses and gratifications perspective. Psychology of Popular Media. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000375

Walsh, S. P., White, K. M., & Young, R. M. (2009). The phone connection: A qualitative exploration of how belongingness and social identification relate to mobile phone use amongst Australian youth. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 19(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.983

Walsh, S. P., White, K. M., & Young, R. M. (2010). Needing to connect: The effect of self and others on young people’s involvement with their mobile phones. Australian Journal of Psychology, 62(4), 194–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530903567229

Wang, J.-L., Wang, H.-Z., Gaskin, J., & Wang, L.-H. (2015). The role of stress and motivation in problematic smartphone use among college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 53, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.005

Wanga, H. P., Joseph, T., & Chuma, M. B. (2020). Social distancing: Role of smartphone during coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic era. International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing, 9(5), 181–188. https://ijcsmc.com/docs/papers/May2020/V9I5202016.pdf

Wei, R. (2008). Motivations for using the mobile phone for mass communications and entertainment. Telematics and Informatics, 25(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2006.03.001

Wen, F., Ding, Y., Yang, C., Ma, S., Zhu, J., Xiao, H., & Zuo, B. (2022). Influence of smartphone use motives on smartphone addiction during the COVID-19 epidemic in China: The moderating effect of age. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03355-w

Whiteside, S. P., & Lynam, D. R. (2001). The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(4), 669–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(00)00064-7

Wickord, L.-C., & Quaiser-Pohl, C. M. (2022). Does the type of smartphone usage behavior influence problematic smartphone use and the related stress perception? Behavioral Sciences, 12(4), Article 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12040099

World Health Organization. (2018). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th revision). https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

Yang, Z., Asbury, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2021). “A cancer in the minds of youth?” A qualitative study of problematic smartphone use among undergraduate students. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19, 934–946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00204-z

Yu, S., & Sussman, S. (2020). Does smartphone addiction fall on a continuum of addictive behaviors? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), Article 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020422

Zhang, K. Z. K., Chen, C., & Lee, M. K. (2014). Understanding the role of motives in smartphone addiction. PACIS 2014 Proceedings, Article 131. https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2014/131

Zhang, K. Z. K., Chen, C., Zhao, S. J., & Lee, M. K. O. (2014, December 14–17). Compulsive smartphone use: The roles of flow, reinforcement motives, and convenience [Paper presentation]. 35th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2014), Auckland, New Zealand. https://scholars.cityu.edu.hk/en/publications/publication(8e37651b-6664-4d45-a285-f35648368203).html

Zhang, M. X., & Wu, A. M. S. (2022). Effects of childhood adversity on smartphone addiction: The multiple mediation of life history strategies and smartphone use motivations. Computers in Human Behavior, 134, Article 107298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107298

Zhen, R., Liu, R.-D., Hong, W., & Zhou, X. (2019). How do interpersonal relationships relieve adolescents’ problematic mobile phone use? The roles of loneliness and motivation to use mobile phones. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), Article 2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132286

Zhitomirsky-Geffet, M., & Blau, M. (2016). Cross-generational analysis of predictive factors of addictive behavior in smartphone usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 682–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.061

Authors’ Contribution

Beau Mostyn Sullivan: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft. Amanda M. George: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, supervision, writing—review & editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

April 3, 2022

Revisions received:

September 18, 2022

November 28, 2022

Accepted for publication:

December 11, 2022

Editor in charge:

Maèva Flayelle

Introduction

Smartphones can offer a range of benefits, such as helping people connect (Wanga et al., 2020), manage their finances (French et al., 2020), and access physical (Agu et al., 2013) and mental health (Hind & Sibbald, 2014) interventions. Given these benefits, it is unsurprising that smartphones have become ubiquitous (Deloitte, 2018, 2019a, 2019b). However, despite the smartphone’s popularity, around 42% of Australians report a belief that they use them excessively, with this rising to 70% among young adults aged 18–24 years (Deloitte, 2019a). Similar rates of excessive use have been reported in other Western countries (Deloitte, 2018, 2019b). For some people, excessive and uncontrolled smartphone use results in harm or functional impairment in daily life, termed problematic smartphone use (PSU; Elhai, Yang, et al., 2020).

Conceptualising Problematic Smartphone Use

PSU is referred to synonymously with various terms in the literature, including smartphone addiction, smartphone use disorder, and problematic smartphone use (Elhai, Yang, et al., 2020). Likened to a behavioural addiction, research has found PSU to include the core components of addiction, such as excessive use, withdrawal, salience, mood modification, and loss of control (De-Sola Gutiérrez et al., 2016; Yu & Sussman, 2020). Despite similarities to addictive disorders, it has been argued that the consequences of PSU are less severe (Panova & Carbonell, 2018) and it is not recognised as a behavioural addiction in diagnostic manuals (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; World Health Organization, 2018). While some authors have emphasised understanding how PSU is similar to established addictive behaviours, others have focussed on its unique presentation. For example, Billieux et al. (2015) proposed that PSU is comprised of three distinct addictive (e.g., cravings), antisocial (e.g., phubbing), and risky (e.g., use while driving) patterns of smartphone use.

In addition to debate about whether PSU should be considered an addiction, there has been controversy about whether people become addicted to smartphone devices or their content (i.e., applications; Davazdahemami et al., 2016). There is now relative consensus that smartphone content is the primary object of problematic engagement (Elhai et al., 2019; Griffiths, 2021). Given this, it has been suggested that, like problematic internet use, PSU is an umbrella construct masking a spectrum of discrete problematic behaviours (e.g., social networking, gaming; Panova & Carbonell, 2018; Starcevic et al., 2021). However, it has also been argued that generalised PSU—that is, the excessive engagement in a range of content on a smartphone—may be a unique construct (I. H. Chen et al., 2020; Griffiths, 2021; Montag et al., 2021), an assertion supported with network analysis (Baggio et al., 2018). The distinctiveness of PSU may be due to the portability of the smartphone facilitating constant access to online (and offline) content (Elhai, Yang, et al., 2020) and unique patterns of problematic behaviour. This can include attachment to the device, use while driving, or use during face-to-face social interactions (Baggio et al., 2018). Therefore, the present study focuses on generalised PSU.

Regardless of conceptual controversy, PSU has been associated with several negative outcomes. In a recent systematic review, Busch and McCarthy (2021) found that PSU was robustly associated with poorer emotional health, such as depression, anxiety, and loneliness. PSU has also been associated with several other negative outcomes across a range of domains, including poor time management, lack of sleep, reduced productivity, interpersonal conflict, and use of a phone while driving (Busch & McCarthy, 2021). A challenge is that many emotional health variables may also be considered antecedents, and research is yet to confirm casual direction (see Elhai, Dvorak, et al., 2017). Notwithstanding this limitation, given the potential harms associated with PSU, it is important to identify risk factors for PSU.

Risk Factors and Aetiology of Problematic Smartphone Use

Research has generally found that adolescents and young adults report higher levels of PSU compared with older age groups (reviewed in Busch & McCarthy, 2021). Horwood et al. (2021) found that PSU levels remained consistent and relatively high from 18–35 years of age, before declining. However, Horwood et al. (2021) noted that higher levels of PSU among younger people may be a generational cohort effect. Most studies have also found that PSU levels are higher among females, but results are somewhat inconsistent (reviewed in Busch & McCarthy, 2021). While understanding demographic risk factors may be important for directing interventions, it is crucial that research identifies psychosocial factors associated with PSU. This will enhance understanding of what causes PSU and may inform interventions, such as challenging maladaptive motives for smartphone use in a clinical setting.

Arguably, the most comprehensive model of PSU proposes that it is driven by three causal pathways (Billieux et al., 2015). The excessive reassurance pathway describes those whose PSU is related to low psychosocial wellbeing (e.g., depression, anxiety) driving a desire to excessively maintain relationships and seek reassurance from others via a smartphone. The impulsive pathway describes those whose PSU is due to heightened levels of impulsive, aggressive, or psychopathic traits, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Finally, the extraversion pathway asserts that some people with heightened levels of extraversion, sensation seeking, and reward sensitivity engage in PSU for stimulation and socialising (Billieux et al., 2015). These pathways were proposed to differentially drive addictive, antisocial, and dangerous patterns of PSU (Billieux et al., 2015). Research has empirically validated the model, although risk factors from the extraversion pathway (except for sensation seeking) have shown limited associations with PSU (Canale et al., 2021; Pivetta et al., 2019). While this pathway model synthesises how various psychosocial factors may influence PSU, it does not explicitly identify variables that may mediate the pathways—except for excessive reassurance seeking, a safety behaviour engaged in by people with psychopathological symptoms, such as depression and anxiety (Cougle et al., 2012). In recent years, research has shifted to investigating variables that may mediate the effects of more distal risk factors (e.g., psychopathology, personality) on PSU (Brand et al., 2019; Elhai et al., 2019), with motives identified as one promising construct (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014; Panova & Carbonell, 2018).

The Role of Motives in Problematic Smartphone Use

Motives have been defined as the reasons why a person engages in a behaviour, reflecting the needs and desires they seek to gratify (Cox & Klinger, 2004; Rubin, 2002; Sundar & Limperos, 2013). Motives, as they are conceptualised in the PSU literature, have roots in the media and substance use literature. The Alcohol Use Motivational Model (Cox & Klinger, 1988) describes motives as the value placed on achieving a desired effect of drinking (e.g., I drink to have fun; Cox & Klinger, 2004). This is in contrast with the related construct of expectancies, which reflects beliefs about the effects of a given behaviour (e.g., drinking is fun; Cox & Klinger, 2004). In the Alcohol Use Motivational Model, expectancies are thought to be important for forming motives, but motives are the more proximal determinant of behaviour (Kuntsche et al., 2010). In fact, the model considers motives to be the final common pathway to behaviour, funneling all other influences, such as psychosocial wellbeing and personality (Cox & Klinger, 2004). The model proposes four categories of motives based on crossing dimensions of valence (desired effect is reward or avoidance of punishment) and source (desired effect is derived internally or externally; Cox & Klinger, 2004). A couple of studies have found that coping, enhancement, and conformity smartphone use motives, which were adapted from the Alcohol Use Motivational Model (Cooper, 1994), predicted PSU, but social motives did not (C. Chen et al., 2017; K. Z. K. Zhang, Chen, & Lee, 2014). However, given the model was developed to explain alcohol use, further research is required to determine whether it is applicable to PSU.

The majority of research which has investigated the association of motives with PSU has been conducted from a Uses and Gratifications Theory (Katz, 1974) and/or Compensatory Internet Use Theory (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014) perspective. The Uses and Gratifications Theory proposes that motives drive the choice to use different types of media (Rubin, 2002; Sundar & Limperos, 2013). Based on this premise, research has identified a range of motives for using different types of media, including the internet (Song et al., 2004), mobile phones, and smartphones (e.g., Leung & Wei, 2000; Lin et al., 2014; Wei, 2008). The Compensatory Internet Use Theory builds on the Uses and Gratifications Theory by integrating it with research that has investigated the association of psychosocial wellbeing with problematic internet use (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). Specifically, it frames problematic internet use as an effort to avoid negative emotions or circumstances, so motives to alleviate negative emotions should mediate or moderate the association of low psychosocial wellbeing with problematic internet use (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). Several studies grounded by the Uses and Gratifications Theory and/or Compensatory Internet Use Theory have found that a range of motives are associated with PSU and mediate or moderate the effect of other psychosocial factors on PSU (e.g., Cheng & Meng, 2021; Elhai, Hall, et al., 2017; J.-H. Kim et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2021). However, neither theory was developed to explain PSU specifically and the latter does not consider the role of motives in potential positive reinforcement pathways to PSU, such as Billieux et al.’s (2015) extraversion pathway.

Motives for Generalised and Specific Problematic Smartphone Use

Of note, theoretical models of problematic internet use, such as the Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution model (Brand et al., 2016, 2019), have conceptualised motives as important for identifying problematic engagement in specific types of online content accessible via a smartphone. For example, motives reflecting a desire for achievement were found to be a key predictor of problematic video gaming (Männikkö et al., 2017), whereas self-presentation motives were found to be a key predictor of problematic social networking (H. T. Chen & Kim, 2013). However, findings from research that identified unique motives for the problematic use of specific types of online content also suggests there are likely core motives (e.g., motives to cope with negative emotions) that influence the problematic engagement in content generally, irrespective of the type (A. Chen & Roberts, 2019; Jiang et al., 2022; Melodia et al., 2022). A body of literature has focussed on identifying what core motives influence generalised PSU (e.g., C. Chen et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2015; K. Z. K. Zhang, Chen & Lee, 2014), but there remains a lack of consensus on what these motives are. Therefore, the present review focusses on understanding the core motives associated with generalised PSU.

The Present Study

Despite the theoretical importance of motives to problematic behaviour, a growing literature investigating their role in PSU, and prior reviews of motives for substance use (Cooper et al., 2015; Kuntsche et al., 2005), no prior study has reviewed the literature investigating the association of motives with PSU. Through our review, we aimed to identify which motives were associated with PSU. Moreover, we aimed to examine whether motives mediate and/or moderate the association of other psychosocial factors with PSU. This was to assess the theoretical proposition that motives act as a final common pathway to PSU, and their integration with the pathway model.

Method

Search Strategy

We used the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2015; Shamseer et al., 2015) to inform methodology. We searched for articles in the Web of Science, SCOPUS, PubMed, ProQuest, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, SAGE, Wiley Online Library, and Google Scholar. Our search terms included synonyms used in the literature for motives and PSU. We used proximity operators limited to five words and restricted our search to title, abstract, and keywords were possible and appropriate. For example, to search Web of Science we entered “(motiv* OR gratification* OR reason* OR need*) AND ((problem* OR addict* OR dependen* OR compulsive OR excessive) NEAR/5 (smartphone* OR “smart phone*” OR mobilephone* OR “mobile phone*” OR cellphone* OR “cell phone*”))”. All citations identified were uploaded into Covidence.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included studies which quantitatively tested the motives-PSU relationship, were written in English, and were published from 2008 to the time of writing this paper.1 Studies were considered to have measured PSU if they included scales labelled with synonymous terms, such as smartphone addiction, problematic mobile phone use, and mobile phone involvement. Studies which examined the association of motives with objective measures of PSU would have also been retained, but none were identified through our search strategy. While young adults are the primary population of interest, we included all relevant studies irrespective of the age range of the sample. This was because initial searches indicated that there were a limited number of total studies (N = 44), with only seven restricting their sample to young adults and seven to adolescents. However, several additional studies (n = 16) used university student convenience samples not restricted to young adults, but likely comprised primarily of young adults.2 Therefore, while young adults are not the only sampled population in the included studies, they and adolescents constituted the majority of participants across most included studies (n = 30). We excluded qualitative studies (Fullwood et al., 2017; Walsh et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2021).

Noting motives and expectancies are conceptually distinct, we excluded one study (Y. Chen et al., 2021) because it operationalised smartphone use motives with items that appeared to include a mix of motives (e.g., because I don’t want to be alone) and expectancies (e.g., playing smartphone is cool). Five other studies (C. Chen et al., 2017, 2019; Wen et al., 2022; K. Z. K. Zhang, Chen, & Lee, 2014; M. X. Zhang & Wu, 2022) operationalised motives with a variable labelled “perceived enjoyment”, the items of which better reflected expectancies. However, we retained these studies because they included other variables that reflected different motives, but we excluded perceived enjoyment from our analysis. We included three studies (Casale et al., 2021; Elhai, Yang, et al., 2020; Hallauer et al., 2022) that tested the associations of the Smartphone Use Expectancies Scale with PSU, given the measure’s items were more consistent with motives (e.g., I use my smartphone to experience pleasure).

As per PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2015; Shamseer et al., 2015), studies were assessed for risk of bias with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's (NHLBI) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (NHLBI, 2014), consistent with prior research in the problematic social media use literature (Frost & Rickwood, 2017). The tool allows poor, fair, and good quality studies to be distinguished. The first and second authors independently assessed study quality and disagreements were resolved via discussion. Given almost all studies were cross-sectional and one was longitudinal (Rozgonjuk et al., 2019), clear causal inferences could not be drawn, so the maximum possible rating was fair.

Results

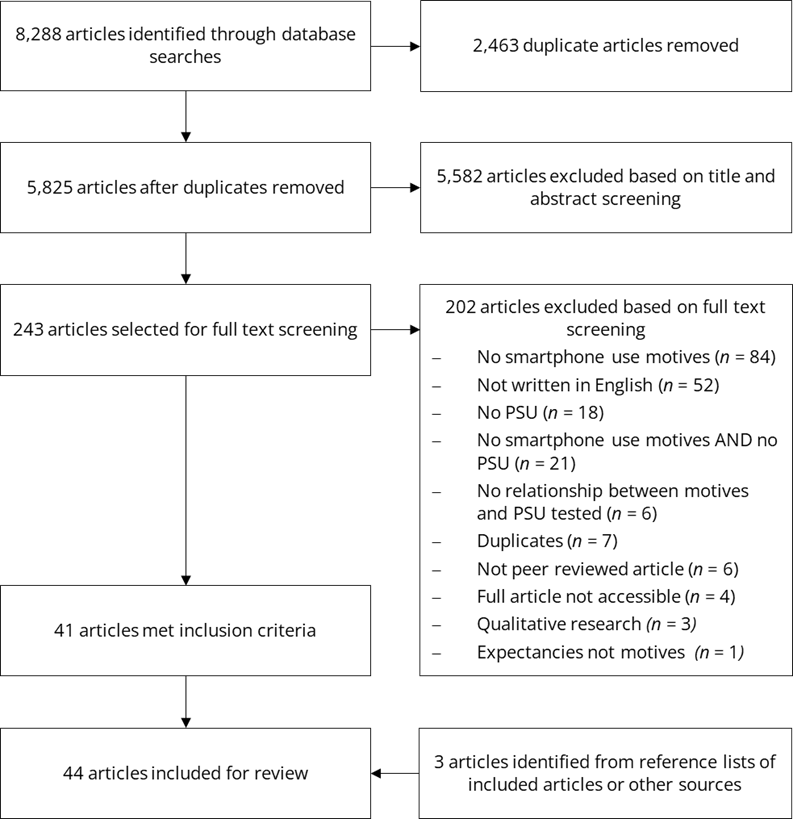

Our searches identified 8,288 journal articles for uploading into Covidence. A total of 2,463 duplicate articles were automatically removed by Covidence, with an additional seven duplicates removed during the screening process. A total of 41 articles met the inclusion criteria. One additional article was identified through examination of reference lists (Elhai, Yang, et al., 2020) and two through other sources (Hallauer et al., 2022; Horwood & Anglim, 2019). The screening process is summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart for Study Inclusion.

Note. PSU = problematic smartphone use.

Risk of Bias

Due to homogeneity of study design, the risk of bias findings lacked variation. Most studies (n = 40) were of fair quality. For example, they included clear research aims, adequately sized and described (albeit often convenience) samples, and/or key covariates (e.g., age, gender). A minority of studies (AlBarashdi & Bouazza, 2019; Lin et al., 2014; Park et al., 2013; Zhitomirsky-Geffet & Blau, 2016) were assessed as poor (e.g., did not control for confounds, used measures that were not well defined, and/or provided a limited description of the population sampled). Given this lack of variation, we have not emphasised the specific risk of bias grade, but discuss several factors that influence risk of bias (e.g., study characteristics, measures) throughout.

Heterogeneity in Smartphone Use Motives Measures

Across the 44 included studies, there were 19 different smartphone use motives measures with a combined 72 motives dimensions (characteristics of the 19 smartphone use motives measures are summarised in Table 1). The number of motives dimensions in each measure varied from two to eight and there were 55 different labels applied to those dimensions. This extensive heterogeneity limited our ability to integrate findings across studies and determine which motives were associated with PSU. Only one measure (Lin et al., 2014) developed items with in-depth interviews asking people why they used their smartphone. All other measures had either an unclear genesis (n = 6) or were largely adapted from prior measures designed to assess motives for using the internet, video games, social networking sites, email, instant messenger applications, online shopping sites, telephones, pagers, television, and alcohol (n = 13).

Table 1. Overview of Smartphone Use Motives Measures Used in the 44 Included Studies.

|

Title/Description |

Authora |

Motive Dimension Labelb |

Genesisc |

|

Smartphone Usage Behaviour Questionnaire |

AlBarashdi and Bouazza (2019) |

1) Social interaction 2) Information sharing and entertainment 3) Self-identity and conforming 4) Self-developing and safety 5) Freedom and privacy 6) Self-express and gossip |

|

|

Smartphone Use Expectancies Scale |

Elhai, Yang, et al. (2020) |

1) Positive expectancies 2) Negative expectancies |

|

|

Motives for Mobile Phone Use |

Hwang and Park (2015) |

1) Instrumental 2) Entertainment 3) Self-identity |

|

|

Dispositional Media Use Motives |

Khang et al. (2013) |

1) Information seeking 2) Social relationship 3) Pastime 4) Self-presence |

|

|

Motivations for Smartphone Use |

J.-H. Kim (2017) |

1) Escape 2) Relationship |

|

|

Motivations for Mobile Phone Use |

J.-H. Kim et al. (2015) |

1) Alleviation 2) Pass-time |

|

|

Motives for Smartphone Use |

Lee and Lee (2017) |

1) Obtaining infotainment 2) Gaining peer acceptance 3) Finding new people |

|

|

Motives for Mobile Phone Application Use |

Lin et al. (2014) |

1) Social benefits 2) Immediate access and mobility 3) Entertainment 4) Self-status seeking 5) Pursuit of happiness 6) Information seeking 7) Socialising |

|

|

Smartphone Use Motivations |

Meng et al. (2020) |

1) Instrumental 2) Self-expression 3) Hedonic 4) Social relationship |

|

|

Motivation for Using a Smartphone |

Paek (2019) |

1) Information seeking 2) Convenience 3) Social interaction 4) Entertainment 5) Passing time |

|

|

Smartphone Use Motivations |

Park and Lee (2014) |

1) Search for information 2) Chat with others 3) Pass leisure time 4) Care for others 5) Follow the trend 6) Easy access to others |

|

|

Motivation for Social Inclusion and Instrumental Use |

Park et al. (2013) |

1) Social inclusion 2) Instrumental |

NR |

|

Smartphone Usage Motivation Scale |

Shen et al. (2021) |

1) Social interaction 2) Entertainment |

|

|

Mobile Phone Uses and Gratifications Scale |

Vanden Abeele (2016) |

1) Pass time 2) Fashion, identity, and status 3) Safety 4) Micro-coordination, mobility, and immediacy 5) School 6) Love 7) Social relationships 8) Avoid face-to-face contact |

|

|

Process and Social Smartphone Usage |

Van Deursen et al. (2015) |

1) Process usage 2) Social usage |

|

|

Smartphone Usage Motivation Scale |

Wang et al. (2015) |

1) Entertainment 2) Escapism |

|

|

Smartphone Use Motives |

K. Z. K. Zhang, Chen, and Lee (2014) |

1) Perceived enjoyment 2) Information seeking 3) Social relationship 4) Mood regulation 5) Pastime 6) Conformity |

|

|

Reinforcement Motives for Smartphone Use |

K. Z. K. Zhang, Chen, Zhao, and Lee (2014) |

1) Mood regulation 2) Instant gratification |

|

|

Motivations for Smartphone Use |

Zhitomirsky-Geffet and Blau (2016) |

1) Virtual community 2) Emotional 3) Information 4) Follow the social environment |

|

|

Note. a The Author column includes references for the study where the motives measure was first used/constructed in the context of smartphone use, as opposed to the study where the measure was first developed to assess motives for different behaviours. b The Motive Dimension Label column includes all motives dimensions assessed in the smartphone use motives measures. c The Genesis column describes how items for the smartphone use motives measures were developed. NR = not reported. |

|||

Categorising Smartphone Use Motives

Despite heterogeneity in the labels applied to smartphone use motives dimensions across the 19 measures, examination of the definitions/items used to operationalise them suggested many measured similar constructs. For example, J.-H. Kim’s (2017) “relationship” motives included the item I use/play with my smartphone to improve relationships with friends and family and Shen et al.’s (2021) “social interaction” motives included the item I use my smartphone to keep in touch with my friends and family. Therefore, to enable synthesis of findings, we used the same approach as Kuntsche et al. (2005) in their systematic review of drinking motives, grouping smartphone use motives dimensions into categories based on their items (where available) and descriptions. These motives categories were: (a) smartphone use to communicate, maintain relationships, and obtain social benefits (“social”); (b) smartphone use to gain identity and approval from a social group, and avoid social disapproval (“self-identity/conformity”); (c) smartphone use to obtain information (“information seeking”); (d) smartphone use to reduce negative emotions (“mood regulation”); (e) smartphone use to avoid boredom (“pass-time”); (f) smartphone use to obtain pleasure (“enhancement”); and (g) smartphone use to feel safe (“safety”). How each of the motives dimensions from the included studies aligns with our proposed motives categories is included in the Appendix.

It is important to note that there remained some heterogeneity within our proposed motives categories, particularly “social” motives. Four smartphone use motives measures (AlBarashdi & Bouazza, 2019; Lin et al., 2014; Park & Lee, 2014; Vanden Abeele, 2016) differentiated multiple types of social motives (e.g., smartphone use for general socialising, smartphone use for more meaningful social interactions, and smartphone use because it facilitates constant access to others). Given few studies/measures distinguished between different social motives, we grouped them together as “social” motives for the purpose of synthesising results, consistent with Kuntsche et al.’s (2005) approach in their review of drinking motives.

Ten motives dimensions could not be categorised due to conceptual overlap (see superscript in Table 2). For example, Van Deursen et al.’s (2015) process motives included the item I use my smartphone in order to escape from real-life, consistent with “mood regulation” motives. However, it also included the items I use my smartphone because it is entertaining, I use my smartphone in order to stay up to date on the latest news, and I use my smartphone because it helps me passing time, consistent with “enhancement”, “information seeking”, and “pass-time” motives, respectively. We were also unable to categorise the five motives dimensions in Paek’s (2019) study, given descriptions or example items were not available. Motives that could not be categorised were excluded from the following synthesis, except where we examined demographic differences, indirect effects, or moderating effects. This was because findings from the latter studies provide insight into how motives may operate in more complex mechanisms and whether they could be a final pathway to PSU.

The Association of Motives with Problematic Smartphone Use

Table 2 summarises the characteristics and findings from all 44 reviewed studies. Only one study used a longitudinal design (Rozgonjuk et al., 2019) and the remainder were cross-sectional. University students (n = 21) and school students (n = 7) were the most sampled populations. Most studies were conducted in East Asia (n = 20) or the United States of America (n = 11). Ten previously validated PSU scales were used across 33 of the included studies and 10 studies adapted their own PSU measure from scales designed to assess different problematic behaviours (e.g., problematic internet use and online video gaming). While the established PSU scales used had somewhat varied content and factor structures, they were mostly developed through a behavioural addiction framework, incorporating previous behavioural addiction research, and adapting internet addiction measures and diagnostic criteria for gambling addiction. Only one of the PSU scales was developed by directly adapting the diagnostic criteria for substance dependence (Chóliz, 2012). For additional analysis of PSU measures, see reviews by Harris et al. (2020) and Yu and Sussman (2020). The following paragraphs synthesise findings for the association of motives with PSU; the strength of both bivariate and multivariate associations were described as per Cohen’s (1988) conventions.

Table 2. Summary of Reviewed Studies.

|

Author |

Sample |

Design |

PSU measure |

Motives measure |

Bivariate Results with PSU |

Multivariate Results with PSU |

|

AlBarashdi and Bouazza (2019) |

849 university students in Oman |

Cross-sectional |

Adapted |

Adapted |

Social interactiona; Information sharing and entertainmenth; self-identity and conformingc r = .12; self-developing and safetyg r = .16; freedom and privacya; self-express and gossipa r = .15 |

N/A |

|

Casale et al. (2022) |

364 participants in Italy aged 18–75 years (Mage = 36.80, SD = 15.32) |

Cross-sectional |

SAS—SV |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

Processh r = .28; Sociala r = .19 |

Controlling for age and gender: FOMO → social → PSU; FOMO → meta-cognitions → social → PSU; FOBU → process → PSU β = .01; FOBU → meta-cognitions → process → PSU β = .004 Controlling for age, gender, FOMO, meta-cognitions: Social Controlling for age, gender, FOBU, meta-cognitions: Process β = .09 |

|

Casale et al. (2021) |

535 participants aged 18–65 years (Mage = 27.38, SD = 9.05) |

Cross-sectional |

SAS—SV |

Smartphone Use Expectancies Scale (Elhai, Yang, et al., 2020) |

PSUEf r = .43; NSUEb r = .57 |

Controlling for metacognitions about smartphone use, age, and gender: Impulsivity → PSUEf; Impulsivity → NSUEb; psychological distress → PSUEf β = .17; psychological distress → NSUEb β = .26; boredom proneness → PSUEf β = .15; boredom proneness → NSUEb β = .38; PSUEf → PSU β = .19; NSUEb → PSU β = .12 |

|

Chang et al. (2022) |

909 university students in China aged 17–25 years (Mage = 20.21, SD = 1.27) |

Cross-sectional |

SAS—C |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

Sociala r = .11 |

N/A |

|

C. Chen et al. (2019) |

379 participants in China (91.29% aged 18–30 years) |

Cross-sectional |

Adapted |

Smartphone Use Motives (K. Z. K. Zhang, Chen, & Lee, 2014) |

N/A |

Controlling for age, income, education, habit, perceived enjoyment: mood regulationb β = .42 |

|

C. Chen et al. (2017) |

384 university students in China (91.1% aged 18–30 years) |

Cross-sectional |

Adapted |

Smartphone Use Motives (K. Z. K. Zhang, Chen, & Lee, 2014) |

N/A |

Controlling for perceived enjoyment: social relationshipsa; mood regulationb β = .22; pastimed β = .16; conformityc β = .20 |

|

Cheng and Meng (2021) |

317 participants in the USA aged 18–35 years (Mage = 30.25, SD = 6.04), previously diagnosed with depression |

Cross-sectional |

SAS |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

Processh r = .56; sociala r = .30 |

Controlling for depression and smartphone usage: processh β = .35; sociala |

|

Elhai, Gallinari, et al. (2020) |

316 university students in the USA aged 18–25 years (Mage = 19.21, SD = 1.74) |

Cross-sectional |

SAS—SV |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

Processh r = .31; sociala r = .20 |

Controlling for gender: depression → FOMO β = .39; anxiety → FOMO β = .27; FOMO → processh β = .24; FOMO → sociala; FOMO → PSU β = .09; processh → PSU β = .18; sociala → PSU |

|

Elhai, Hall, et al. (2017) |

309 participants in the USA aged 18 years or more (Mage = 33.15, SD = 10.21) |

Cross-sectional |

SAS |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

Processh → PSU facets: positive anticipation r = .50; withdrawal r = .32; cyberspace relationships r = .34; overuse r = .38; tolerance r = .22 positive anticipation r = .27; withdrawal r = .15; cyberspace relationships; overuse r = .23; tolerance |

Controlling for age, gender: Processh → PSU facets: positive anticipation β = .49; withdrawal; cyberspace relationships; overuse β = .24; tolerance positive anticipation β = .28; withdrawal; cyberspace relationships; overuse β = .25; tolerance |

|

Elhai et al. (2018) |

305 university students in the USA (Mage = 19.44, SD = 2.16) |

Cross-sectional |

SAS |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

Processh r = .53; sociala r = .23 |

N/A |

|

Elhai, Levine, et al. (2017) |

308 participants in the USA aged 18 years or more (Mage = 33.15, SD = 10.21) |

Cross-sectional |

SAS |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

Processh r = .40; sociala r = .16 |

Controlling for age, gender: processh β = .57; sociala β = .19; depression → sociala → PSU; anxiety → processh → PSU β = .28; anxiety → sociala → PSU |

|

Elhai, Yang, et al. (2020) |

286 university students in the USA aged 18–25 years (Mage = 19.72, SD = 2.60) |

Cross-sectional |

SAS—SV |

Adapted |

PSUEf r = .39; NSUEb r = .55 |

Controlling for gender, rumination, depression, and anxiety: NSUEb B = .10; PSUEf |

|

Farhat et al. (2021) |

200 participants (96% aged 36 years or less) |

Cross-sectional |

Adapted |

Reinforcement Motives for Smartphone Use (K. Z. K. Zhang, Chen, Zhao, & Lee 2014) |

N/A |

Controlling for convenience and flow: mood regulationb β = .16; instant gratificationf β = .14 |

|

Fu et al. (2020) |

584 school students in China aged 13–18 years (Mage = 16.13, SD = 2.80) |

Cross-sectional |

MPPUS—SV |

Motivations for Smartphone Use (J.-H. Kim, 2017) |

Escapeb r = .61 |

Controlling for age, gender: Parental monitoring → escapeb β = .10; escapeb → PSU β = .61 |

|

Gentina and Rowe (2020) |

463 school students in France aged 16–18 years (Mage = 16.8) |

Cross-sectional |

MPI |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

N/A |

Processh β = .39; sociala β = .14; youth materialism → processh → PSU β = .21; youth materialism → sociala → PSU |

|

Hallauer et al. (2022) |

352 university students in the USA aged 18–53 years (Mage = 19.79, SD = 3.43) |

Cross-sectional |

SAS—SV |

Smartphone Use Expectancies Scale (Elhai, Yang, et al., 2020) |

PSUEf r = .49; NSUEb r = .54 |

Controlling for mindfulness, gender, age, and social distancing: Depression → PSUEf; depression → NSUEb; anxiety → PSUEf β = .21; anxiety → NSUEb β = .23; PSUEf → PSU β = .43; NSUEb → PSU β = .39; depression → PSUEf → PSU; depression → NSUEb → PSU; anxiety → PSUEf → PSU; anxiety → NSUEb → PSU |

|

Hao et al. (2022) |

766 university students in China aged 17 year or more (Mage = 20.10, SD = 1.15) |

Cross-sectional |

SAS—SV |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

Processh r = .25; sociala r = −.10 |

Controlling for age, gender, and academic burnout: Processh β = .04; Sociala |

|

Horwood and Anglim (2018) |

393 university students in Australia (Mage = 24.4, SD = 7.1) |

Cross-sectional |

MPPUS |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

Processh r = .60; sociala r = .27 |

N/A |

|

Horwood and Anglim (2019) |

539 university students in Australia aged 18–65 years (Mage = 25.1, SD = 7.8) |

Cross-sectional |

MPPUS |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

Processh r = .64; sociala r = .31 |

N/A |

|

Hwang and Park (2015) |

550 school students in South Korea aged 14–19 years (Mage = 17.68, SD = 3.35) |

Cross-sectional |

MPPUS |

Adapted |

N/A |

Controlling for age, gender, peer conformity, impulsivity, imitation, loneliness, social anxiety, amount of smartphone use: Regression on attachment PSU facet: Instrumentalh β = .14; entertainmenth; self-identityc Regression on withdrawal PSU facet: entertainmenth; self-identityc entertainmenth; self-identityc |

|

Khang et al. (2013) |

290 university students in the USA (Mage = 21, SD = 3.72) |

Cross-sectional |

MPAS |

Adapted |

N/A |

Controlling for time spent on smartphone, self-esteem, self-efficacy, self-control, media flow: information seekinge; social relationshipa β = .11; pastimed β = .24; self-presencec β = .27 |

|

J.-H. Kim (2017) |

930 participants in the USA aged 13–40 years (Mage = 25.56, SD = 8.20). |

Cross-sectional |

MPPUS and SAS |

Adapted |

Escapeb r = .58; relationshipa r = .31 |

Loneliness → escapeb → SMC → PSU b = 0.005; Loneliness → relationshipa → F2F contact → PSU b = 0.0003 |

|

J.-H. Kim et al. (2015) |

395 participants in the USA aged 18–68 (Mage = 31.64, SD = 9.69). |

Cross-sectional |

Adapted |

Adapted |

N/A |

Alleviationb β = .37; pass-timed β = .26; depression → alleviationb→ PSU β = .12; depression → pass-timed → PSU |

|

Lee and Lee (2017) |

3,000 school students in South Korea from grade |

Cross-sectional |

SAPS |

Adapted |

Obtaining infotainmenth r = .24; gaining peer acceptancec r = .46; finding new peopleh r = .21 |

Controlling for gender, school type, socio economic status, attachment to parents, attachment to friends, attachment to teachers: Obtaining infotainmenth β = .10; gaining peer acceptancec β = .37; finding new peopleh β = .06 |

|

Li et al. (2021) |

1,034 school students in China aged |

Cross-sectional |

MPAI |

Motivations for Smartphone Use (J.-H. Kim, 2017) |

Escapeb r = .52 |

Controlling for gender and loneliness: escapeb β = .44 Controlling for gender: loneliness → escapeb → PSU β = .11; Escapeb x self-control β = −.05; Escapeb x Impulsivity |

|

Lin et al. (2014) |

441 participants |

Cross-sectional |

Adapted |

Adapted |

N/A |

Social benefitsa β = −.23; immediate access and mobilitya β = −.22; entertainmentf β = −..24; self-status seekingc β = .45; pursuit of happinessh β = .49; information seekinge β = .17; socialisinga |

|

Meng et al. (2020) |

8,261 school students in China aged |

Cross-sectional |

Adapted |

Adapted |

Instrumentale r = −.22; self-expressionc r = .10; hedonich r = .21; social relationshipsa r = .09 |

Controlling for age, gender, school grade, relationship with parents, parents’ age, parents’ education level, living district location, living district type, family annual income, smartphone functions: instrumentale β = −.23; self-expressionc; hedonich; social relationshipsa β = −.17 |

|

Paek (2019) |

339 university students in South Korea aged 18–28 years (Mage = 21.47, SD = 1.86) |

Cross-sectional |

SAPS |

Adapted |

Information seekingh; convenienceh; social interactionh r = .12; entertainmenth r = .33; passing timeh r = .23 |

Controlling for gender, academic achievement, perceived stress: passing timeh β = .16 |

|

Park et al. (2013) |

852 participants in South Korea aged 17–49 years |

Cross-sectional |

Not reported |

NR |

Social inclusiona r = .46; Instrumentale use r = .36 |

Controlling for innovativeness, behavioural activation system, locus of control, perceived relationship control, perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness: Social inclusiona β = .25; instrumentale |

|

Park and Lee (2014) |

275 university students in South Korea |

Cross-sectional |

Adapted |

Adapted |

Search for informatione; chat with othersa t = 2.59; pass leisure timed; care for othersa t = 4.14; follow the trendc t = 3.73; easy access to othersa t = 2.65 |

N/A |

|

Rozgonjuk et al. (2019) |

261 University students in the USA (Mage = 19.73, SD = 3.52) |

Longitudinal |

SAS—SV |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

Processh r = .31; sociala r = .15 |

Processh β = .39; sociala β = .16; intolerance of uncertainty → processh → PSU β = .17; intolerance of uncertainty → sociala → PSU |

|

Sever and Özdemir (2022) |

380 university students in Turkey aged |

Cross-sectional |

SAS—SV |

Smartphone Usage Motivation Scale (Wang et al., 2015) |

Entertainmenth r = .37; escapismd r = .51 |

Controlling for perceived stress and FOMO: Entertainmenth β = .15; escapismd β = .29 |

|

Shen et al. (2021) |

549 university students in China (Mage = 18.39, SD = 1.92) |

Cross-sectional |

SAS—C |

Adapted |

High PSU group: entertainmenth r = .29 Low PSU group: entertainmenth |

Controlling for age, gender, anxiety: High PSU group entertainmenth model: entertainmenth x anxiety β = .26 social interactiona x anxiety β = .79 entertainmenth x anxiety social interactiona x anxiety |

|

Shen and Wang (2019) |

549 university students in China (Mage = 18.39, SD = 1.92) |

Cross-sectional |

SAS—C |

Smartphone Usage Motivation Scale (Wang et al., 2015) |

Entertainmenth r = .24; escapismd r = .41 |

Controlling for age, gender, stress, stress x entertainmenth: Entertainmenth model: loneliness → entertainmenth → PSU β = −.05; Stress x entertainmenth β = .29 Escapismd model: loneliness → escapismd → PSU β = .12; stress x escapismd |

|

Van Deursen et al. (2015) |

386 participants in the Netherlands aged 15–88 years (Mage = 35.2, SD = 14.7) |

Cross-sectional |

MPPUS |

Adapted |

Processh r = .43; sociala r = .18 |

Controlling for age, gender, emotional intelligence, social stress, self-regulation, habitual smartphone behaviour: processh β = .15; sociala |

|

Vezzoli et al. (2021) |

528 university students aged 18–29 years (Mage = 22.38, SD = 2.06) |

Cross-sectional |

TMPD |

Mobile Phone Uses and Gratifications Scale (Vanden Abeele, 2016) |

N/A |

Pass-timed β = .35; statusc β = .33; safetyg β = .09; avoid F2F contacta β = .09; micro-coordinationa; schoola; lovea; social relationshipsa |

|

Wang et al. (2015) |

549 university students in China (Mage = 18.39, SD = 1.92). |

Cross-sectional |

SAS—C |

Adapted |

High PSU group: escapismd r = .22 Low PSU group: escapismd r = .35 |

Controlling for age, gender, stress: High PSU group entertainmenth model: entertainmenth x stress β = .21 escapismd x stress β = .12 entertainmenth x stress β = .13 escapismd x stress |

|

Wen et al. (2022) |

746 adolescents aged 12–18 years (Mage = 15.83, SD = 1.89) and 600 adults aged 19–59 years (Mage = 38.50, SD = 10.64) in China |

Cross-sectional |

SAS-SV |

Smartphone Use Motives (K. Z. K. Zhang, Chen, & Lee, 2014) |

Social relationshipsa r = .11; mood regulationb r = .33; pastimed r = .36; conformityc r = .30 |

Controlling for gender, education level, and perceived enjoyment: Social relationshipsa r = .15; mood regulationb r = .14; pastimed β = .13; conformityc β = .16 Age x social relationships β = −.06; Age x mood regulation; Age x pastime; age x conformity |

|

Wickord and Quaiser-Pohl (2022) |

108 participants in Germany aged 17–70 (Mage = 31.8, SD = 12.2) |

Cross-sectional |

MPPUS-SV |

Process and Social Smartphone Usage (Van Deursen et al., 2015) |

Processh r = .56; sociala r = .28 |

Controlling for habitual use, age, and gender: Processh β = .28; sociala |

|

K. Z. K. Zhang, Chen, Zhao, & Lee (2014) |

384 university students in China (91.1% aged 18–30 years) |

Cross-sectional |

Adapted |

Adapted |

N/A |

Controlling for convenience, flow: mood regulationb β = .38; instant gratificationf β = .23 |

|

K. Z. K. Zhang, Chen, & Lee (2014) |

394 university students in China (91.3% aged 18–30 years) |

Cross-sectional |

Adapted |

Adapted |

N/A |

Controlling for perceived enjoyment: information seekinge; social relationshipsa; mood regulationb β = .17; pastimed β = .16; conformityc β = .15 |

|

M. X. Zhang and Wu (2022) |

956 university students in China aged |

Cross-sectional |

SPAI |

Smartphone Use Motives (K. Z. K. Zhang, Chen, & Lee, 2014) |

Social relationshipsa r = .19; mood regulationb r = .34; pastimed r = .40; conformityc r = .32 |

Controlling for age, gender, perceived enjoyment, childhood adversity, and slow life history strategy: social relationshipsa; mood regulationb β = .10; pastimed β = .27; conformityc β = .18 Controlling for age and gender: Slow life history strategy → pastime → PSU β = −.01; Slow life history strategy → conformity → PSU β = .007; Slow life history strategy → mood regulation → PSU; Slow life history strategy → social → PSU |

|

Zhen et al. (2019) |

4,509 school students in China aged |

Cross-sectional |

MPPUS—SV |

Motivations for Smartphone Use (J.-H. Kim, 2017) |

Escapeb r = .64; relationshipa r = .35 |

Escapeb β = .57; relationshipa β = .08; PCR → escapeb → PSU β = −.08; PCR → relationshipa → PSU β = −.00; PCR → loneliness → escapeb → PSU β = −.02; TSR → escapeb → PSU β = −.04; TSR → relationshipa → PSU; TSR → loneliness → escapeb → PSU β = −.02 |

|

Zhitomirsky-Geffet and Blau (2016) |

209 participants in Israel aged 13–68 years |

Cross-sectional |

SAS |

Adapted |

PSU behaviour factor: emotionalb; informatione; social environmentc r = .32 emotionalb r = .30; informatione; social environmentc r = .33 emotionalb; informatione r = −.24; social environmentc r = .40 |

Controlling for Big 5 personality factors, PSU emotional and social factors, and smartphone application usage: virtual communitya; emotionalb; informatione; social environmentc |

|