Why do we trust in online reviews? Integrative literature review and future research directions

Vol.17,No.2(2023)

Online reviews are an important information source in decision-making processes. Basing decisions on online reviews, however, requires consumers to trust. Consequently, studying trust has become a major research concern. This article provides an integrative literature review of 70 articles published between 2005 and 2021 that, using both quantitative and qualitative approaches, investigated which factors affect trust in the context of online reviews. Results show that research examined 77 different factors for their effect on trust. For most factors—such as integrity of reviewer, quality of argument, and consistency of review with other reviews—, the findings are relatively distinct. The impact of some other factors—such as homophily, two-sidedness of reviews, and emotionality of reviews—is less clear. To synthesize and systematize the results, I develop a conceptual framework based on a model of the online review process. This framework identifies six groups of factors, namely factors related to reviewers, opinion seekers, platforms, communities, option providers, and external actors. On a more general level, the review finds that research uses many different operationalizations of trust, yet rarely embraces more comprehensive concepts of trust. Based on an assessment of the state of the field, I suggest that future research should corroborate, integrate, and expand upon this body of knowledge.

online reviews; eWOM; trust; credibility; literature review; theory

Nils S. Borchers

Institute of Media Studies, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany

Nils S. Borchers is a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer at the Chair of Empirical Media Research, Institute of Media Studies at the U of Tübingen. Nils earned his PhD at U of Mannheim and his MA at the U of Münster. His research interests include digital communication, peer-to-peer-communication, strategic communication, and critical advertising studies.

Borchers, N. S. (2021). Online-Bewertungs-Kompetenz: Grundlegende Kompetenzen im Umgang mit Peer-Bewertungen als Informationsquelle in Entscheidungsprozessen [Online review literacy: Fundamental competences in using online reviews as information sources in decision processes]. In M. Seifert & S. Jöckel (Eds.), Bildung, Wissen und Kompetenz(-en) in digitalen Medien [Education, knowledge, and competencies in digital media] (pp. 159-174). Freie Universität Berlin. https://doi.org/10.48541/dcr.v8.9

Ayeh, J. K., Au, N., & Law, R. (2013). “Do we believe in TripAdvisor?” Examining credibility perceptions and online travelers’ attitude toward using user-generated content. Journal of Travel Research, 52(4), 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512475217

Babić Rosario, A., de Valck, K., & Sotgiu, F. (2020). Conceptualizing the electronic word-of-mouth process: What we know and need to know about eWOM creation, exposure, and evaluation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(3), 422–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00706-1

Bae, S., & Lee, T. (2011). Product type and consumers’ perception of online consumer reviews. Electronic Markets, 21(4), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-011-0072-0

Baker, M. A., & Kim, K. (2019). Value destruction in exaggerated online reviews: The effects of emotion, language, and trustworthiness. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1956–1976. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2018-0247

Banerjee, S., & Chua, A. Y. K. (2019). Trust in online hotel reviews across review polarity and hotel category. Computers in Human Behavior, 90, 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.09.010

Barber, B. (1983). The logic and limits of trust. Rutgers University Press.

Bartosiak, M. (2021). Can you tell me where to stay? The effect of presentation format on the persuasiveness of hotel online reviews. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(8), 1109–1122. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1765749

Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2016). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review (2nd ed.). Sage.

Bore, I., Rutherford, C., Glasgow, S., Taheri, B., & Antony, J. (2017). A systematic literature review on eWOM in the hotel industry: Current trends and suggestions for future research. Hospitality & Society, 7(1), 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1386/hosp.7.1.63_1

BrightLocal (2022). Local consumer review survey 2022. https://www.brightlocal.com/research/local-consumer-review-survey/

Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., Guinalíu, M., & Ekinci, Y. (2015). Do online hotel rating schemes influence booking behaviors? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 49, 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.05.005

Cheung, C. M. K., & Thandani, D. R. (2010). The state of electronic word-of-mouth research: A literature analysis. In PACIS 2010 Proceedings (pp. 1580–1587). AIS eLibrary.

Cheung, M. Y., Luo, C., Sia, C. L., & Chen, H. (2009). Credibility of electronic word-of-mouth: Informational and normative determinants of online consumer recommendations. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 13(4), 9–38. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEC1086-4415130402

Chevalier, J. A., & Mayzlin, D. (2006). The effect of word of mouth on sales: Online book reviews. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(3), 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.43.3.345

Clare, C. J., Wright, G., Sandiford, P., & Caceres, A. P. (2018). Why should I believe this? Deciphering the qualities of a credible online customer review. Journal of Marketing Communications, 24(8), 823–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2016.1138138

Craciun, G., & Moore, K. (2019). Credibility of negative online product reviews: Reviewer gender, reputation and emotion effects. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.010

de Langhe, B., Fernbach, P. M., & Lichtenstein, D. R. (2016). Navigating by the stars: Investigating the actual and perceived validity of online user ratings. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(6), 817–833. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucv047

Dimoka, A. (2010). What does the brain tell us about trust and distrust? Evidence from a functional neuroimaging study. MIS Quarterly, 34(2), 373–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/20721433

Dou, X., Walden, J. A., Lee, S., & Lee, J. Y. (2012). Does source matter? Examining source effects in online product reviews. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1555–1563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.03.015

Duffy, A. (2017). Trusting me, trusting you: Evaluating three forms of trust on an information-rich consumer review website. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 16(3), 212–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1628

Filieri, R. (2016). What makes an online consumer review trustworthy? Annals of Tourism Research, 58, 46–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.12.019

Flanagin, A. J., & Metzger, M. J. (2013). Trusting expert- versus user-generated ratings online: The role of information volume, valence, and consumer characteristics. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1626–1634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.001

Fukuyama, F. (1996). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Free Press.

Geertz, C. (2017). Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. In The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays (3rd ed., pp. 3–30). Basic Books.

Gefen, D. (2002). Reflections on the dimensions of trust and trustworthiness among online consumers. ACM SIGMIS Database: DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 33(3), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1145/569905.569910

Gefen, D., Benbasat, I., & Pavlou, P. (2008). A research agenda for trust in online environments. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(4), 275–286. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222240411

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003). Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 27(1), 51–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036519

Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Polity.

Gössling, S., Hall, C. M., & Andersson, A.-C. (2018). The manager’s dilemma: A conceptualization of online review manipulation strategies. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(5), 484–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1127337

Grabner-Kräuter, S., & Waiguny, M. K. J. (2015). Insights into the impact of online physician reviews on patients’ decision making: Randomized experiment. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(4), Article e93. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3991

Graf, H. (2018). Media practices and forced migration: Trust online and offline. Media and Communication, 6(2), 149–157. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v6i2.1281

Hardin, R. (1992). The street-level epistemology of trust. Analyse & Kritik, 14(2), 152–176. https://doi.org/10.1515/auk-1992-0204

Hoffjann, O. (2013). Trust in public relations. In D. Gefen (Ed.), Psychology of trust: New research (pp. 59–73). Nova.

Ismagilova, E., Slade, E., Rana, N. P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2020). The effect of characteristics of source credibility on consumer behaviour: A meta-analysis. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Service, 53, Article 101736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.01.005

Khoo, C. S. G., Na, J.‐C., & Jaidka, K. (2011). Analysis of the macro-level discourse structure of literature reviews. Online Information Review, 35(2), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684521111128032

King, R. A., Racherla, P., & Bush, V. D. (2014). What we know and don’t know about online word-of-mouth: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(3), 167–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2014.02.001

Kohring, M. (2004). Vertrauen in Journalismus: Theorie und Empirie [Trust in journalism: Theory and empirical evidence]. Universitätsverlag Konstanz.

Kohring, M., & Matthes, J. (2007). Trust in news media: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Communication Research, 34(2), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650206298071

Krueger, F., & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2019). Toward a model of interpersonal trust drawn from neuroscience, psychology, and economics. Trends in Neurosciences, 42(2), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2018.10.004

Lappas, T. (2012). Fake reviews: The malicious perspective. In G. Bouma, A. Ittoo, E. Métais, & H. Wortmann (Eds.), Natural language processing and information systems (pp. 23–34). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-31178-9_3

Lewis, J. D., & Weigert, A. (1985). Trust as a social reality. Social Forces, 63(4), 967–985. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/63.4.967

Lim, Y.-s., & Van Der Heide, B. (2015). Evaluating the wisdom of strangers: The perceived credibility of online consumer reviews on Yelp. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12093

Lis, B. (2013). In eWOM we trust. A framework of factors that determine the eWOM credibility. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 5(3), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-013-0261-9

Luhmann, N. (1990). Essays on self-reference. Columbia University Press.

Luhmann, N. (2018). Trust and power. Polity (Original work published 1968, 1975).

Maslowska, E., Malthouse, E. C., & Bernritter, S. F. (2017). Too good to be true: The role of online reviews’ features in probability to buy. International Journal of Advertising, 36(1), 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1195622

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9508080335

McGeer, V., & Pettit, P. (2017). The empowering theory of trust. In P. Faulkner & T. Simpson (Eds.), The philosophy of trust (pp. 14–34). Oxford University Press.

McKnight, D. H., & Chervany, N. L. (2001). What trust means in e-commerce customer relationships: An interdisciplinary conceptual typology. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 6(2), 35–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10864415.2001.11044235

Meyer, S. B., & Ward, P. R. (2013). Differentiating between trust and dependence of patients with coronary heart disease: Furthering the sociology of trust. Health, Risk & Society, 15(3), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2013.776017

Mishra, A. K. (1996). Organizational responses to crisis: The centrality of trust. In R. Kramer & T. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 261–287). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452243610.n13

Möllering, G. (2001). The nature of trust: From Georg Simmel to a theory of expectation interpretation and suspension. Sociology, 35(2), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0038038501000190

Moran, G., & Muzellec, L. (2017). eWOM credibility on social networking sites: A framework. Journal of Marketing Communications, 23(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2014.969756

Morgner, C. (2018). Trust and society: Suggestions for further development of Niklas Luhmann’s theory of trust. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne De Sociologie, 55(2), 232–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12191

Mudambi, S. M., & Schuff, D. (2010). What makes a helpful online review? A study of customer reviews on Amazon.com. MIS Quarterly, 34(1), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.2307/20721420

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191

Ohanian, R. (1991). The impact of celebrity spokespersons’ perceived image on consumers’ intention to purchase. Journal of Advertising Research, 31(1), 46–54. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1991-26094-001

Open Science Collaboration (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), Article aac4716. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716

O’Reilly, K., MacMillan, A., Mumuni, A. G., & Lancendorfer, K. M. (2016). Extending our understanding of eWOM impact: The role of source credibility and message relevance. Journal of Internet Commerce, 15(2), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2016.1143215

Prendergast, G., Ko, D., & Yin, Y. V. S. (2010). Online word of mouth and consumer purchase intentions. International Journal of Advertising, 29(5), 687–708. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0265048710201427

Rani, A., & Shivaprasad, H. N. (2018). Determinants of electronic word of mouth persuasiveness: A conceptual model and research propositions. Journal of Contemporary Management Research, 12(2), 1–16. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/determinants-electronic-word-mouth-persuasiveness/docview/2171578064/se-2

Romero, L. S., & Mitchell, D. E. (2017). Toward understanding trust: A response to Adams and Miskell. Educational Administration Quarterly, 54(1), 152–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X17722017

Rotter, J. B. (1971). Generalized expectancies for interpersonal trust. American Psychologist, 26(5), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031464

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393–404. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.926617

Seckler, M., Heinz, S., Forde, S., Tuch, A. N., & Opwis, K. (2015). Trust and distrust on the web: User experiences and website characteristics. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.064

Smith, D., Menon, S., & Sivakumar, K. (2005). Online peer and editorial recommendations, trust, and choice in virtual markets. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19(3), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20041

Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4(3), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283

Tzieropoulos, H. (2013). The trust game in neuroscience: A short review. Social Neuroscience, 8(5), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2013.832375

Van Der Heide, B., & Lim, Y.-s. (2016). On the conditional cueing of credibility heuristics: The case of online influence. Communication Research, 43(5), 672–693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214565915

van Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford University Press.

Wang, S., Cunningham, N. R., & Eastin, M. S. (2015). The impact of eWOM message characteristics on the perceived effectiveness of online consumer reviews. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 15(2), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2015.1091755

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

Wrightsman, L. S. (1991). Interpersonal trust and attitudes toward human nature. In J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 373–412). Academic. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-590241-0.50012-5

Zhang, X., Wu, Y., & Wang, W. (2021). eWOM, what are we suspecting? Motivation, truthfulness or identity. Journal of Information Communication & Ethics in Society, 19(1), 104–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICES-12-2019-0135

Author’s Contribution

This study was devised and conducted by Nils S. Borchers.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

September 22, 2021

Revisions received:

September 28, 2022

February 20, 2023

Accepted for publication:

February 22, 2023

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

Online reviews of such diverse “objects” as cameras, hotels, physicians, and university lecturers have become a mass phenomenon. Many internet users search through reviews of peer consumers, peer patients, peer students, etc. before taking decisions so that online reviews have gained a considerable impact in many areas of everyday lives (e.g., Chevalier & Mayzlin, 2006; Maslowska et al., 2017). Basing decisions on online reviews requires the trust of opinion seekers in the evaluations of their peers. Accordingly, trust in and credibility of online reviews are of specific importance for explaining the effects of reviews. However, trusting in online reviewers and their reviews is a high-risk undertaking. For example, the opinion seeker usually lacks information on both the reviewer’s motives to provide the review and the reviewer’s qualification to evaluate the reviewed object. Furthermore, the providers of the reviewed objects benefit from positive evaluations of their offerings and thus have strong incentives to influence reviews in their favor (Lappas, 2012). Yet despite these obstacles, surveys indicate that internet users widely trust online reviews: For example, an US industry survey (BrightLocal, 2022) found that 49 percent of consumers trust online reviews as much as they trust personal recommendations from family and friends.

Studying trust has become a main concern in research on online reviews. As this review article will show, I identified 70 research articles published in peer-reviewed journals that examined trust in online review contexts. However, a focused overview of their findings is still missing. There exist various literature reviews (Bore et al., 2017; C. M. K. Cheung & Thandani, 2010; Ismagilova et al., 2020; King et al., 2014; Rani & Shivaprasad, 2018) and conceptual frameworks (Moran & Muzellec, 2017) that address research on electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) communication. These works are, however, neither focused exclusively on online reviews nor on trust and credibility. To close this gap, this article sets out to provide an integrative literature review of empirical studies on trust in online review contexts. It contributes to the field by collecting existing findings, offering a framework for organizing these findings, and identifying shortcomings and research desiderata to indicate future research directions.

Theorizing Trust in Online Review Contexts

In this section, I will put forward a suggestion on how to theorize trust in online review contexts. To do so, I will first introduce my theoretical understandings of online reviews and trust. Then, I will bring the two understandings together to develop a framework for organizing the empirical findings in the field.

Online Reviews

Online reviews are usually discussed as a specific format of eWOM communication. eWOM is defined as “consumer-generated, consumption-related communication that employs digital tools and is directed primarily to other consumers“ (Babić Rosario et al., 2020). eWOM thus serves as an umbrella concept that includes not only online reviews, but also other types of computer-mediated peer-consumer conversations. In contrast to other eWOM formats, online reviews are usually posted on specific online review platforms. These platforms can be both integrated within retailer homepages (e.g., Amazon, Bookings), fan communities (e.g., Metalstorm, The Metal Archives), and social networking sites (e.g., Facebook), as well as created independently (e.g., Yelp, HealthGrades). Online reviews have been defined as “peer-generated product evaluations posted on company or third-party websites” (Mudambi & Schuff, 2008, p. 186). For the current study, I heavily draw on this definition but specify that I consider all studies relevant that examine peer evaluations in the review section of a review platform. These reviews may be posted on an actual platform or generated specifically for a scientific study. It should be noted that this approach leads to an exclusion of online reviews published on individual blogs, e.g., by social media influencers. I decided to exclude these reviews because the conditions under which trust in online reviews emerges on review platforms differs markedly from the conditions under which it emerges on blogs.

Trust

Trust is a common social phenomenon that can be observed in many, if not all, areas of everyday life. Yet, when trying to pinpoint trust, the fuzziness of the concept becomes apparent. Many researchers have tackled trust from the perspective of their respective fields and presented a wide range of conceptualizations (see Gefen et al., 2003, for an overview). However, many scholars agree that in a trust relationship, a trustor acts on the grounds of the expectation that a trustee acts in a specific way, although the trustee could also act differently (Barber, 1983; Gefen et al., 2003; Giddens, 1990; Hardin, 1992; Luhmann, 1968, 1975/2018; Möllering, 2001). For example, a consumer (aka the trustor) who reads an online review of a camera might expect that the reviewer (aka the trustee) has collected sufficient information about and gained extensive experience of the camera before publishing a review. The tricky point here is that the trustor cannot be sure whether the trustee actually acts in the expected way. This uncertainty makes trust risky because the trustee could always act differently than expected, but the trustor will find out whether the trustee fulfilled their expectations only after having trusted them (Gefen et al., 2003; Luhmann, 1968, 1975/2018). For example, a consumer buys the particular camera just to find out that the reviewer did not discuss relevant dysfunctionalities and weaknesses. Alternatively, some authors highlight the vulnerability of the trustor as a key characteristic of trust (e.g,. McGeer & Pettit, 2017; Mishra, 1996; Rousseau et al., 1998) and thus emphasize the consequences of entering a relationship whose outcomes are uncertain because they depend on the trustee.

For this review, I chose to draw on a concept that was, at its core, developed by Luhmann (1968, 1975/2018). Luhmann shares the definition of trust relationships that I just introduced. Imperative for the Luhmannian understanding of trust then is the notion of “own selectivity” (Luhmann, 1990). The concept of own selectivity starts from the observation that, in most situations, a person faces more than one option how to act and therefore must make a decision. It highlights that only this person can make the decision. In a next analytical step, Luhmann introduces a second person to the situation to highlight the social consequences of own selectivity. In their actions, the second person depends on the first person and therefore has to find ways to cope with the first person’s own selectivity as the general autonomy to decide what to do. For Luhmann, trust is a mechanism that helps the second person (the trustor) to do so by acting on the grounds of the assumption that the first person (the trustee) will act as expected. Other such mechanisms are, for example, familiarity, contracts, and hope (Kohring, 2004). A consequence of this understanding of trust is that trust is always addressed to another social actor such as online reviewers and not to entities without own selectivity such as online reviews. This position also explains why, in trying to be analytically rigorous, I use the somewhat cumbersome formulation “trust in online review contexts” instead of “trust in online reviews.”

Since trusting is a risky business, trustors try to identify reasons to trust (Kohring, 2004). Such reasons serve as legitimation for entering a trust relationship because they reduce the perceived risk. For instance, in the camera example, the educational background of the reviewer or the conformity of a review with other reviews on the same camera may function as reasons to trust. Reasons to trust usually refer to particular dimensions of trust (Kohring, 2004). While trust is regarded as a multidimensional concept (Gefen, 2002; Lewis & Weigert, 1985; Romero & Mitchell, 2017), there exists less consensus about which dimensions constitute trust. Some authors argue in support of general principles that address the risk and vulnerability of the trustor such as benevolence (McKnight & Chervany, 2001; Romero & Mitchell, 2017), honesty (Fukuyama, 1995; Seckler et al., 2015), or reliability (Mishra, 1996; Rotter, 1971). In contrast, Luhmann (1968, 1975/2018) argues that the dimensions of trust depend on the social context of the trust relationship. That is to say that the dimensions of trust will be different in different social contexts. For example, the dimensions of trust in a writer of online reviews differs from those of trust in a judge or in a politician because online review author, judge, and politician fulfill different functions in society. In this review, I follow this second line of reasoning.

A considerable debate in trust research circles around the question whether trust should be considered a belief, an attitude, an intention, or a combination of these (for an overview, see Gefen et al., 2003). The Luhmannian line of understanding trust brings up yet another possibility: From its perspective, trust can be regarded as a social relation between two (or more) persons. Accordingly, it holds that trust emerges in and through the relationship rather than “residing” in the trustor. This perspective allows to adjourn the debate on belief, attitude, and intention without neglecting its relevance.

Luhmann’s concept of trust has proven to be productive for the study of trust in mediated communication (e.g., Graf, 2018; Hoffjann, 2013; Kohring, 2004). Like any other concept, however, Luhmann’s concept opens specific perspectives while, at the same time, suffering from its blind spots. This is why I want to emphasize that there exist other trust concepts (e.g., Barber, 1983; Giddens, 1990; Lewis & Weigert, 1985; McGeer & Pettit, 2017; Möllering, 2001) that are worth exploring and that will open different perspectives on trust in online review contexts. Beyond the question of which particular concept to adopt, I suggest that engaging with more comprehensive concepts of trust is fruitful because it sharpens the analytical capabilities of research on trust in online review contexts.

Trust in Online Review Contexts

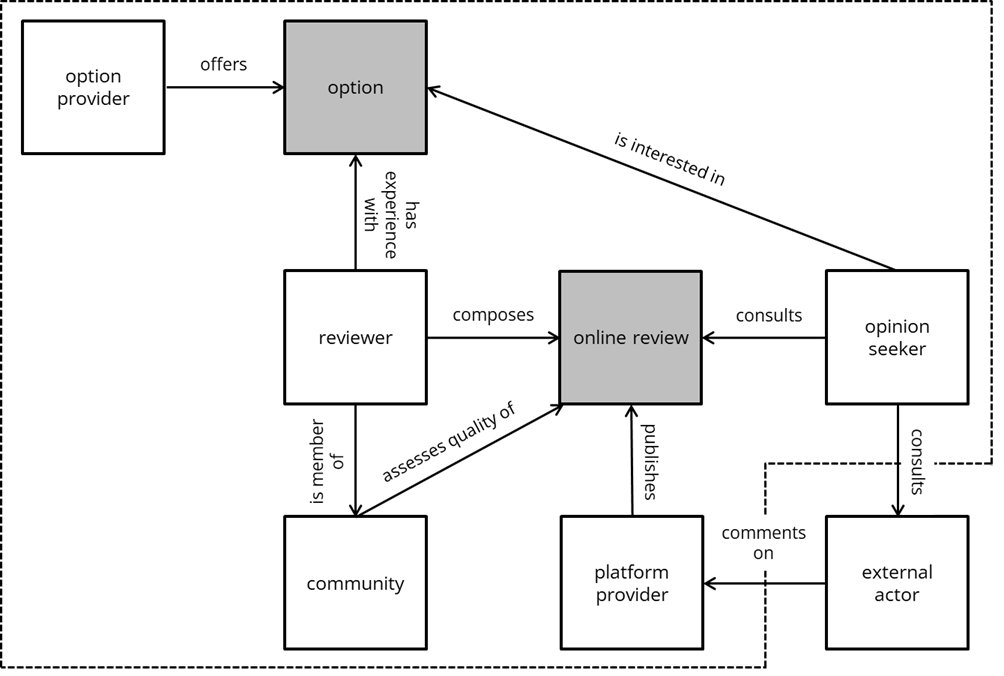

As Duffy (2017) pointed out, there are different forms of trust in online review contexts. To identify relevant trust relationships, I employed a model of the ideal online review process (Figure 1). The model identifies the various actors involved in the review process: An option provider (e.g., camera manufacturer or physician) offers a specific option (e.g., camera that can be bought or health treatment that can be received). A reviewer, who, ideally, has experience with using this option, composes a review to share this experience. The review is (usually) published on a platform, provided by a platform provider (e.g., Amazon or Healthgrades). A community of platform users assesses the quality of the review (e.g., via comments, flagging, helpfulness votes). An opinion seeker who is interested in the option consults the review as part of their decision making on whether to select the option. In addition to reading the review, the opinion seeker might collect further information provided by an external actor, i.e., an actor who is neither associated with the platform nor the option. Note also that the model only captures the most basic operation of the online review process, which is one opinion seeker consulting one review. In most cases, the opinion seeker will consult more than one review and compare the reviews with each other.

Figure 1. Model of the Ideal Online Review Process.

Note. White boxes symbolize actors within the process. Gray boxes symbolize cultural artifacts. Arrows symbolize relations between actors and artifacts. Dotted lines frame the core of the online review process. Note that the model indicates relations only for the ideal case in which all actors act in a way that facilitates the best online review quality.

From the perspective of the opinion seeker, the involvement of other actors poses risks due to each actor’s own selectivity: The opinion seeker cannot know whether these actors act in a way that ensures good review quality and thus might disappoint expectations directed toward them. For example, platform providers might sell specific editing options to option providers, option providers might pay reviewers to write tendentious reviews (Gössling et al., 2018), reviewers might be unconsciously biased toward premium brands (de Langhe et al., 2016), and community members might have different views on what constitutes a helpful review. Because of these risks, the opinion seeker needs to trust in one or more of the involved actors if they consult online reviews as a source of information in the decision-making process. This conclusion implies that trust in online review contexts usually goes beyond the sole trust in the reviewer to also involve other actors as trustees. The model of the online review process provides a framework for organizing research on trust in online reviews. It allows for attribution of the examined factors to specific actors in the online review process, by indicating to whose actor’s selective actions the factor refers.

Considering the various actors also helps to reflect on four distinctive features of trust in online review contexts that, in combination, distinguish this setting from offline settings. First, while pooling recommendations in offline settings usually includes familiar trustees such as friends, family members, and colleagues, trust in online review contexts is directed at anonymous strangers such as reviewers and platform communities (Borchers, 2021). This mechanism allows opinion seekers to benefit from the experiences of other internet users beyond local, temporal, and social constraints, yet it comes at the price of drastically reduced familiarity with the trustees. Second, review platforms allow their users to share experiences and thus facilitate trust between strangers. However, they provide not only the technical infrastructure for the online review process, but also the terms and conditions for publishing and accessing online reviews (van Dijck, 2013). These terms and conditions reflect the commercial interests of platform providers. Third, quality management is delegated to the community and usually takes place only after the publication. This is different from other (offline) sources to which opinion seekers could turn such as travel books when looking for accommodation or consumer safety groups when looking for a new smoothie maker. Fourth, the online review process is expected to be a peer-to-peer communication process (Borchers, 2021). Peer-to-peer communication implies that the roles of reviewer and opinion seeker are generally interchangeable. Consequently, all opinion seekers could also act as reviewers and vice versa. Such role flexibility does not exist in most other social contexts, such as traditional advertising or journalism.

Research Questions

Trust in online reviews has emerged as an eminent topic in the research on eWOM. This review article aims at providing an overview of the state of research. First, it addresses the research designs that researchers apply. Research designs determine what researchers can see. For example, standardized surveys make exactly those attitudes, intentions, behaviors etc. visible that the surveys ask for. In contrast, observations do not predefine what is to see and thus expand the perspective of the researcher, yet they usually fail to see the broader picture beyond individual cases because they focus on only a few participants.

RQ1: Which research designs are applied in studies on trust in online review contexts?

Second, this review examines the theoretical conceptualizations that inform studies on trust in online review contexts. Like methods, theoretical conceptualizations allow researchers to see specific aspects of a phenomenon because they direct the view of the researcher.

RQ2: How do studies on trust in online review contexts conceptualize trust?

While the RQ1 and RQ2 provide information on how researchers produced their findings, the third research question aims at the actual findings and accounts for the factors that explain trust in online review contexts.

RQ3: Which factors have which effects on trust in online review contexts?

Method

Methodological Framework: Integrative Literature Review

To answer the research questions, I conducted an integrative literature review (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). The integrative literature review “reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way” (Torraco, 2005, p. 356). It aims at generating a summary of research trends as well as new perspectives and frameworks on the reviewed topic (Khoo et al., 2011; Torraco, 2005). The integrative literature review supports my objectives in going beyond the description of existing research and allowing for the application of a new conceptual framework and the development of future research directions.

Data Collection

An appropriate and comprehensive literature search strategy is important for enhancing the rigor of literature reviews. The strategy should allow identification of all relevant articles to ensure that the review is based on an adequate corpus and can yield accurate results (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

Databases

Online reviews are studied in different disciplines, such as marketing, communication, psychology, information systems, and tourism. To take the diversity of the research field into account, I considered a variety of established international academic databases: (1) Business Source Premier, (2) Communication & Mass Media Complete, (3) PsycARTICLES, (4) PsycINFO, (5) PSYNDEX, (6) Library Information Science and Technology Abstracts, and (7) Web of Science.

Search Term

The research literature discusses online reviews under various labels. I therefore included alternative labels in the search term by varying (a) the term “online” with “internet,” “digital,” and, as a large share of existing studies is interested in consumer behavior, “consumer;” and (b) the term “review” with “rating” and “recommendation.” In addition, I searched for the term “eWOM” or “electronic word-of-mouth” (in different variants) because eWOM is an umbrella concept that includes online reviews. Furthermore, research on trust relies on two theoretical concepts, trust and credibility (Kohring & Matthes, 2007). As the two terms are closely connected, I decided to include both in the search term. These considerations resulted in the search term displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Final Search Term for Integrative Literature Review.

|

Block |

Search Term Entered in Topic Field |

|

Dependent variable |

(trust* OR cred*) |

|

|

AND |

|

Study context |

(ewom OR “electronic word-of-mouth“ OR “electronic word of mouth“ OR “word-of-mouse“ OR “word of mouse“ OR “online review“ OR “online rating“ OR “online recommendation“ OR “internet review“ OR “internet rating“ OR “internet recommendation“ OR “digital review“ OR “digital rating“ OR “digital recommendation“ OR “consumer review“ OR “consumer rating“ OR “consumer recommendation”) |

Selection Criteria

I included an article in the corpus of this review if it met the following content criteria: (1) The article explains the perception of trust (or credibility, respectively) in an online review or the reviewer (see section 2.1), i.e., it conceptualizes trust in online review contexts as a dependent or mediating variable. Articles that focused on trust in other social actors, such as brands or platforms, were not included. I also did not consider articles that examined trust exclusively as an independent or moderating variable. (2) The article focuses on online reviews. Articles on other eWOM formats, including blog posts, forum postings, or social media commentaries, were excluded. Articles were also excluded if they studied online reviews posted outside of review platforms. If in doubt whether an article studied online reviews, for example if the article addressed eWOM and did not specify the eWOM format, I excluded it to ensure a clean data set. (3) The article presents the results of an empirical study.

Furthermore, I introduced three formal criteria: (4) The article is published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. (5) The article is published in English. (6) The article is published before January 1, 2021, the cutoff date of the query.

Article Selection

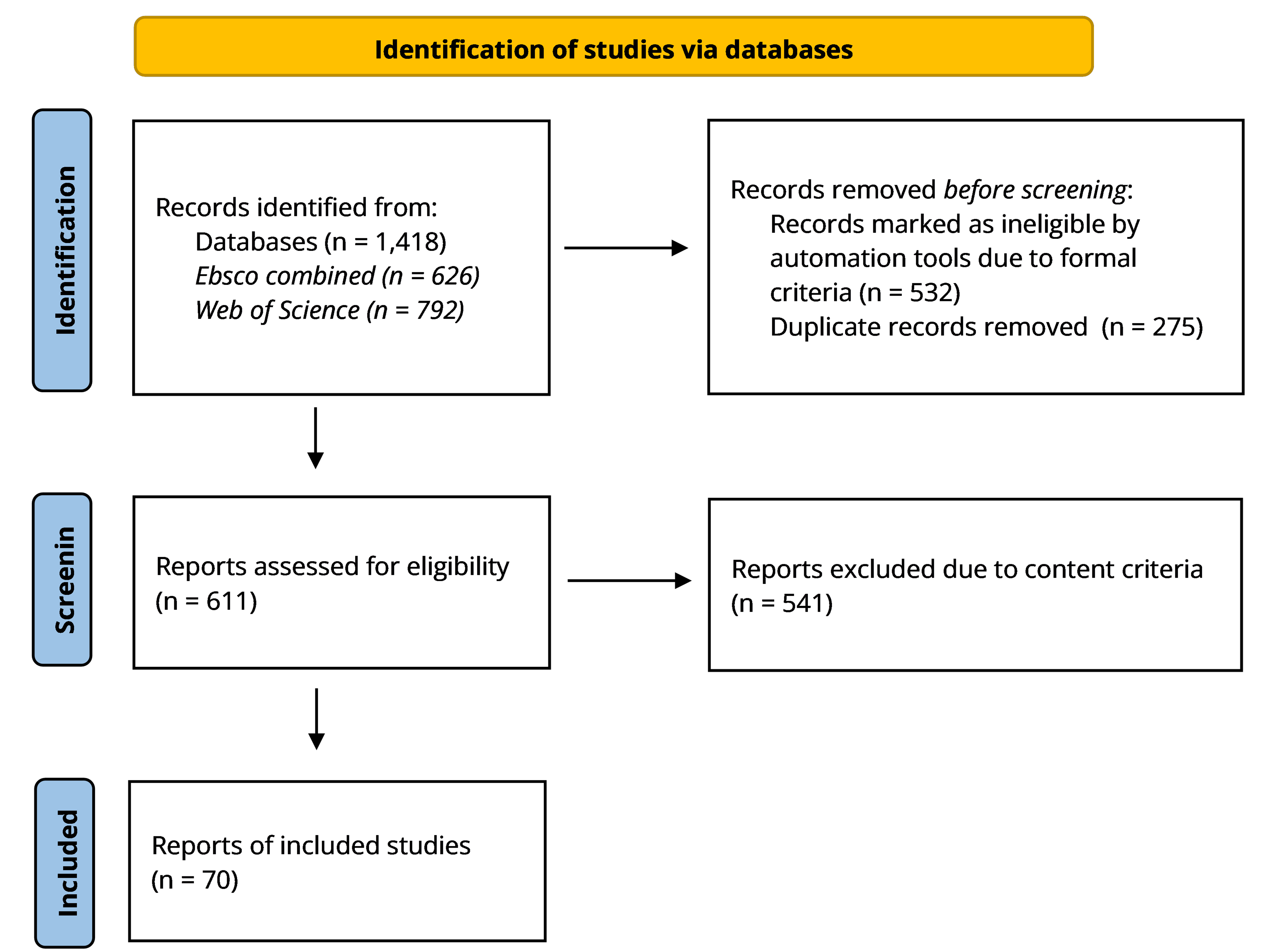

The full text query yielded 1,418 records in the seven databases. The combined Ebsco databases (databases 1–6) produced 626 hits, and Web of Science produced 792 hits. As the first step, I removed all articles that did not meet the formal criteria. 510 records were published in other formats than in peer-reviewed scientific journals, another 22 records were published in languages other than English, while all remaining articles were published before the cutoff date of the query. Applying the formal criteria thus led to the exclusion of 532 records. I then controlled the remaining 886 records for duplicates. This procedure identified 275 duplicates, reducing the number of records to 611. As the next step, I used the content criteria to decide whether the article should be included in the sample. To do so, I reviewed the title, keywords, and abstract. If this information did not suffice to make a decision, I examined the full text of the article. This procedure yielded to the exclusion of another 541 records. The final sample thus comprised 70 articles (see Appendix A). Figure 2 displays the selection process.

Data Analysis

For data analysis, I followed Whittemore and Knafl’s (2005) instructions for integrative literature reviews. They propose the following procedure: (1) Data reduction: I coded the articles for concepts of trust, theories, methods, examined factors, and results. (2) Data display: I synthesized the data from the individual articles and organized it into subgroups. This process was guided by Kohring’s (2004) concept of trust and the online review process model. I put particular attention to the identification of different factors discussed under the same label and similar factors discussed under different labels. (3) Data comparison: I examined the synthesized findings to identify strengths, shortcomings, and desiderata of the field. I placed emphasis on a critical analysis as described by Torraco (2005). (4) Conclusion drawing: I critically assessed the current state of research to develop future research directions.

Figure 2. Overview of Article Selection Process.

Note. Adapted from Page et al., 2020 (modified).

Results

Corpus Characteristics and Bibliometrics

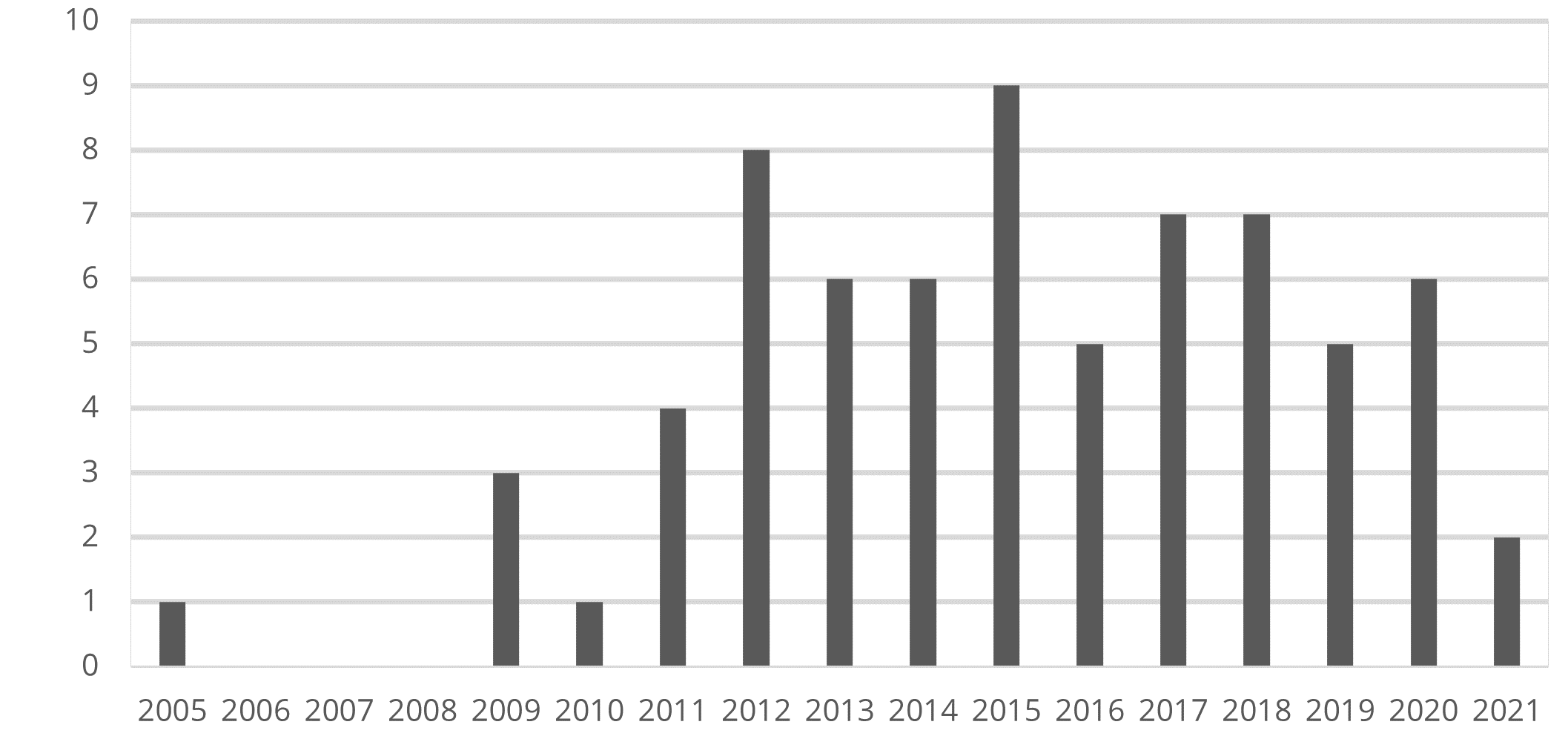

I identified 70 articles on trust in online review contexts that met the selection criteria. The first article on the topic was published in 2005, but more profound scholarly interest in the topic started growing only in 2011 (see Figure 3). Articles were published in 43 individual journals (see Table 2). The large number of journals indicates a high fragmentation of the research field. Only five journals published more than two articles on the topic.

Figure 3. Number of Publications per Year of Articles on Trust in Online Review Contexts.

Note. The database search for this literature review was conducted in early 2021 and covers research activities before January 1, 2021. The database search yielded two articles (Bartosiak, 2021; Zhang et al., 2021) that were registered as online first versions for 2020. These articles have been published in a journal issue in the meantime and are thus displayed as 2021 in this figure.

Table 2. Journals That Have Published Articles on Trust in Online Review Contexts.

|

Journal Name |

Number of Published Articles |

|

Computers in Human Behavior |

10 |

|

Decision Support Systems |

3 |

|

International Journal of Hospitality Management |

3 |

|

Internet Research |

3 |

|

Journal of Business Research |

3 |

|

10 other journals |

10 x 2 |

|

28 other journals |

28 x 1 |

|

|

70 |

Research Designs

Research on trust in online reviews applies several methods (see Table 3). Experiments are the most employed method by far, followed by standardized surveys. Accordingly, there is a predominance of articles that adopt quantitative approaches (64 articles) over articles that adopt qualitative (2 articles) or mixed quantitative-qualitative designs (4 articles). Using student samples is a common procedure in the field (30 studies), although most studies rely on general population samples (49 studies). The samples demonstrate geographical diversity (see Table 4). Most studied review objects are hotels (21 studies), electronics (e.g., cameras, TV sets; 16 studies), and restaurants (15 studies). Many studies, especially surveys, do not specify a review platform, but adopt platform-independent approaches, while some focus on existing platforms. Platforms studied most often are TripAdvisor (12 studies), Amazon (6 studies), and Yelp (5 studies), which clearly indicates a Western bias.

Table 3. Methods Applied in Studies on Trust in Online Review Contexts.

|

Method |

Number of Studies Employing Method |

|

Experiment |

50 |

|

Standardized survey |

25 |

|

Qualitative interviews |

4 |

|

Computational methods |

1 |

|

Critical incident technique |

1 |

|

Grounded theory methodology (incl. qualitative interviews and other data gathering techniques) |

1 |

|

|

82 |

|

Note. Number of reported studies differs from number of articles because some articles (a) report findings from more than one study or (b) apply multi-method designs. |

|

Table 4. Sample Origins in Studies on Trust in Online Review Contexts.

|

Sample Origin |

Number of Studies Using Sample |

|

USA |

22 |

|

China |

10 |

|

Multinational |

9 |

|

Germany |

5 |

|

Taiwan |

5 |

|

South Korea |

4 |

|

Others |

13 |

|

Not specified |

14 |

|

thereof Amazon Mechanical Turk |

11 |

|

|

82 |

|

Note. Number of reported studies differs from number of articles because some articles report findings from more than one study. |

|

Conceptualizing and Measuring Trust

Few studies are informed by more comprehensive concepts of trust. Although it is admittedly hard to determine what is a “more comprehensive concept” and when such a concept “informs” a study, I identified eight articles that related to a conceptual work on trust at least on the level of a definition of trust and not only in passing. The works by Mayer et al. (1995; 6 references) and McKnight and Chervany (2001; 5 references) found some resonance in the field. This resonance might result from the fact that the first and widely cited study in the field (Smith et al., 2005) is informed by these works.

Trust is more often conceptualized on the level of its operationalization for empirical inquiries. I therefore examined reported scales and items that were used to measure trust. I identified a total number of 46 scales that have been used in the field. 38 scales draw on items that originate from previous research, i.e., studies either adopting a complete scale or combining different scales, while eight studies used their own scales. Although the scale presented by Ohanian (1990, 1991) was used much more frequently than others (informing 15 articles), the variety of scales again suggests a great heterogeneity of the field. Qualitative studies used wordings that are similar to the wordings of items in quantitative studies. Where articles reported questions from interview guides, there was a tendency to ask respondents for trust or trustworthiness directly rather than breaking the concept down to its various dimensions.

Examined Factors and Their Effect on Trust

Research has examined the impact of 77 factors on the emergence of trust in online review contexts. I used the model of the online review process to systemize these factors by organizing them according to the actors upon whose own selectivity they touch. For most factors, this process should be self-evident. For example, I assigned the experience of the reviewer in writing reviews to the reviewer since experience will help a reviewer to compose a sound review. Experience thus indicates that trusting this particular reviewer might be less risky. Yet for some other factors, this process may appear to have less face validity. For example, I sorted status badges that reviewers can earn on some platforms in the category “platform-related factors” and not “reviewer-related factors.” I did this although one might think that the badge indicates that a reviewer is trustworthy. However, it is the platform provider who decides whether the platform awards such badges, who determines what the criteria are for acquiring a badge, and who ensures a robust award process. The same logic applies to some of the factors that I systemized as “community-related.” For example, whether a particular review is consistent with other reviews of the same review object depends on the decision that the other reviewers made when writing their reviews. These other reviewers constitute the community. Obviously, the particular reviewer can also tune in the review to the community’s voice. From the perspective of the opinion seeker, however, the other reviews constitute the background against which to assess the consistency of a particular review. The opinion seeker thus has to determine how to respond to this background: Should they base their own assessment of the particular review on these other reviews, or should they discard them? In other words: The opinion seeker has to decide whether to trust in the community. I therefore categorized the consistency of a particular review with other reviews as a community-related factor.

Reviewer-Related Factors

The most exhaustively studied actor in the field is the reviewer. The opinion seeker’s perception of the reviewer’s states and traits is informed by the review that the reviewer wrote as well as by other information that the reviewer provides on the platform, usually when adding information to the user profile. Table 5 presents the reviewer-related factors that have been examined. Research literature often treats review characteristics independently from the reviewer. However, the reviewer is the author of the review and the review depends on their own selectivity. For example, Bannerjee and Chua (2019) examined how the attractiveness of review titles impacts trust but essentially, it is the reviewer who concocts this title. Table 6 presents the findings on review-related factors as a subset of reviewer-related factors.

Table 5. Examined Reviewer-Related Factorsa.

|

Factor |

Effect on Trust |

Articleb |

|

|

Gender of reviewer |

+ |

for indicated gender |

Craciun and Moore (2019) |

|

Personal identifying information of reviewer information provided on reviewer, e.g., real name, residence, preferences |

+ |

for provided information |

Kusumasondjaja et al. (2012); Xie et al. (2011) |

|

Profile picture of reviewer provision of profile picture or choice of avatar |

+ |

for provided profile picture (VS no profile picture provided) / for provided human avatar (VS dinosaur avatar) |

Filieri (2016); McGloin et al. (2014); Xu (2014) |

|

+ |

for high physical attractiveness of the reviewer picture |

Lin and Xu (2017) |

|

|

Authenticity of reviewer extent to which the identity of reviewer appears to be authentic or fake |

- |

for low authenticity |

Ahmed and Sun (2018); Dinh and Doan (2020); Zhang et al. (2021) |

|

Object knowledge of reviewer extent to which reviewer has expertise, competence, or ability regarding the reviewed object, e.g., many reviews within the product category of the reviewed option, is “competent,” “experienced,” “well-qualified” |

+ |

for vast knowledge |

Clare et al. (2018); Filieri (2016); Hsiao et al. (2010); J. Lee and Hong (2019); Lis (2013); Naujoks and Benkenstein (2020); O’Reilly et al. (2016); Smith et al. (2005); X. Wang et al. (2015) |

|

0 |

for vast knowledge |

Mumuni et al. (2020) |

|

|

- |

for self-claimed vast knowledge |

Willemsen et al. (2012) |

|

|

- |

for low knowledge |

Duffy (2017) |

|

|

Duration of platform membership of reviewer period the reviewer has been registered as review platform member |

+ |

for long duration |

Banerjee et al. (2017) |

|

Integrity of reviewer extent to which reviewer is independent form influences by a third-party, e.g., by endorsements, monetary incentives |

+ |

for high integrity |

Dickinger (2011); Dou et al. (2012); Filieri (2016); Hsiao et al. (2010); O’Reilly et al. (2016); Reimer and Benkenstein (2018) |

|

- |

for low integrity |

Ahmed and Sun (2018) |

|

|

|

0 |

for high integrity |

Hussain et al. (2018)c |

|

Motives of reviewer motives of reviewer to write the review |

+ |

for review object-related motives |

Dou et al. (2012); Qiu et al. (2012) |

|

- |

for ulterior motives |

Willemsen et al. (2012) |

|

|

- |

for non-benevolent motives |

Duffy (2017) |

|

|

0 |

for non-benevolent motives |

Zhang et al. (2021) |

|

|

Trustworthiness of reviewer extent to which reviewer is credible, e.g., “dependable,” “honest,” “reliable,” “believable” |

+ |

for high trustworthiness |

C. M.-Y. Cheung et al. (2012); M. Y. Cheung et al. (2009); Clare et al. (2018); Lis (2013); Luo et al. (2014, 2015); Mumuni et al. (2020) |

|

0 |

for high trustworthiness |

Filieri et al. (2015) |

|

|

Homophily extent to which reviewer is similar to opinion seeker, e.g., regarding gender, age, job, taste |

+ |

for high homophily |

Ayeh et al. (2013); Smith et al. (2005); Su et al. (2017) |

|

0 |

for high homophily |

Lin and Xu (2017) |

|

|

Social closeness of reviewer extent to which opinion seeker feels socially close to reviewer, e.g., wishing to have reviewer as friend or colleague |

0 |

for high social closeness |

Lin and Xu (2017) |

|

Note. Effects on trust are indicated as follows: + indicates a significant positive effect of factor on trust in the online review process; - indicates a significant negative effect of factor on trust in the online review process; 0 indicates that there is no significant effect of factor on trust in the online review process. aFor table including interactions, see Appendix B, Table B1. bFor full references, see Appendix A. cHussain et al. (2018) adopt concept and items from a study on reviewer motives for eWOM contribution. The authors test it as antecedent of eWOM credibility as perceived by an opinion seeker. It is not explained how this concept that refers to reviewers informs the examination of the opinion seeker’s perceptions and how items were possibly adjusted.

|

|||

Table 6. Examined Review-Related Factorsa.

|

Factor |

Effect on Trust |

Articleb |

|

|

Pictures of reviewed option review provides pictures of reviewed option |

+ |

for provided pictures |

Filieri (2016) |

|

Attractiveness of title of review extend to which the review title catches the attention |

+ |

for attractive title |

Banerjee and Chua (2019) |

|

Conciseness of title of review extent to which the title of the review provides a concise preview on review |

0 |

for high conciseness |

Banerjee and Chua (2019) |

|

Style of review way in which the reviewer wrote the review, e.g., foreign words, technical terms, orthographical errors, or “easy to read,” “well written” |

0 |

for lexical complexity |

Jensen et al. (2013) |

|

+ |

for correct orthography |

McGloin et al. (2014) |

|

|

0 |

for correct orthography |

Cox et al. (2017) |

|

|

Quality of review general quality of review |

+ |

for high quality of review |

Filieri (2015, 2016); Filieri et al. (2015) |

|

0 |

for high quality of review |

Mahat and Hanafiah (2020); S. Wang et al. (2015); Willemsen et al. (2012) |

|

|

Argument quality of review extent to which reviewer presents sound arguments in review |

+ |

for high quality of argument |

C. M.-Y. Cheung et al. (2012); M. Y. Cheung et al. (2009); Luo et al. (2013, 2014, 2015); Racherla et al. (2012); Reimer and Benkenstein (2016) |

|

Information load of review extent to which the review is rich with information, e.g., length, details, scope, or information-richness |

+ |

for high information load |

Baker and Kim (2019); Banerjee and Chua (2019); Dickinger (2011); Duffy (2017); Luo et al. (2013) |

|

- |

for too high or too low information load |

Furner et al. (2016) |

|

|

+ |

for moderate information load |

Furner et al. (2016) |

|

|

+ |

for review with factual, detailed, and relevant information |

Filieri (2016) |

|

|

0 |

for high information load |

Tsang and Prendergast (2009) |

|

|

Two-sidedness of review extent to which reviewer discusses positive and negative aspects of the reviewed product |

+ |

for two-sided review |

C. M.-Y. Cheung et al. (2012); Clare et al. (2018); Filieri (2016); Jensen et al. (2013); Luo et al. (2014) |

|

0 |

for two-sided review |

M. Y. Cheung et al. (2009); Luo et al. (2015) |

|

|

Helpfulness of review extent to which reviewer provides helpful information |

+ |

for high helpfulness |

Clare et al. (2018); Mahat and Hanafiah (2020) |

|

Emotionality of review extent to which reviewer uses emotion-laden words, e.g., “love,” capital letters, emoticons and exclamation marks, no quantified criteria |

+ |

for high emotionality |

S. Wang et al. (2015) |

|

- |

for high emotionality |

Baker and Kim (2019); Clare et al. (2018); Craciun and Moore (2019); Jensen et al. (2013) |

|

|

+ |

for low emotionality |

Luo et al. (2015) |

|

|

Subjectivity of review extent to which reviewer shared subjective information |

+ |

weaker for subjective information than for objective information |

Hong and Park (2012); K.-T. Lee and Koo (2012) |

|

Trustworthiness of descriptions in review extent to which the provided information is “trustworthy,” “reliable,” “credible” |

+ |

for high trustworthiness |

Mahat and Hanafiah (2020) |

|

0 |

for high trustworthiness |

Banerjee and Chua (2019) |

|

|

Consistency of review text and rating extent to which (textual) review and associated (numerical) rating are consistent |

+

|

for high consistency |

Tsang and Prendergast (2009) |

|

Timeliness of review extent to which the review is up-to-date |

+ |

for high timeliness |

Clare et al. (2018) |

|

Valence of review (positive) extent to which the review praises the review object |

+ |

for positive valence |

Banerjee et al. (2017); Lim and Van Der Heide (2015); Lin and Xu (2017) |

|

0 |

for valence review (vs. neutral) |

Baker & Kim (2019) |

|

|

- |

for overtly positive valence |

Filieri (2016); Prendergast et al. (2018) |

|

|

Valence of review (negative) extent to which the review criticizes the review object |

0 |

for negative valence |

M. Y. Cheung et al. (2009); Willemsen et al. (2012) |

|

0 |

for valence review (vs. neutral) |

Baker and Kim (2019) |

|

|

- |

for overtly negative valence |

Filieri (2016); Prendergast et al. (2018) |

|

|

Note. Effects on trust are indicated as follows: + indicates a significant positive effect of factor on trust in the online review process; - indicates a significant negative effect of factor on trust in the online review process; 0 indicates that there is no significant effect of factor on trust in the online review process. aFor table including interactions, see Appendix B, Table B2. bFor full references, see Appendix A. |

|||

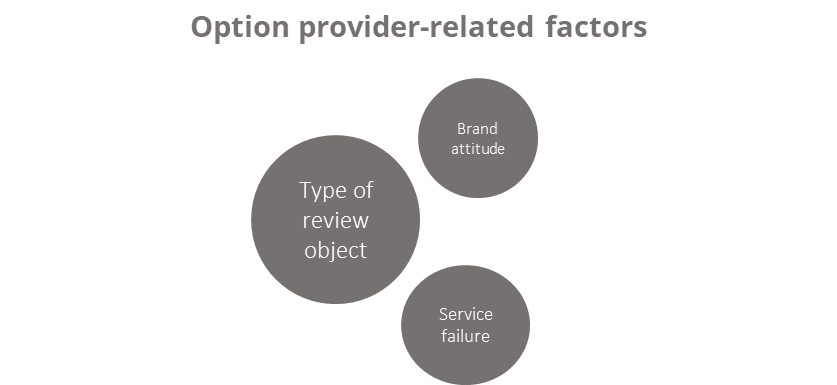

Option Provider-Related Factors

The impact of the provider of the reviewed option has been examined only rudimentarily (see Table 7). Notably, Bae and Lee (2011) found that the type of review object influences trust relationships. This factor should be treated with consideration. While the option provider decides which type of options they offer at a market, the review object itself is not an actor in its own right and thus does not possess own selectivity. According to the trust concept informing this literature review, the type of review object should thus rather be theorized as moderator variables than as independent variable.

Table 7. Examined Option Provider-Related Factorsa.

|

Factor |

Effect on Trust |

Articleb |

|

|

Brand attitude extent of brand commitment and attitude of opinion seeker toward reviewed brand |

0 |

for high brand attitude |

Jensen and Yetgin (2017) |

|

Type of review object

|

+ |

stronger for experience good than for search good |

Bae and Lee (2011) |

|

Note. Effects on trust are indicated as follows: + indicates a significant positive effect of factor on trust in the online review process; - indicates a significant negative effect of factor on trust in the online review process; 0 indicates that there is no significant effect of factor on trust in the online review process. aFor table including interactions, see Appendix B, Table B3. bFor full references, see Appendix A. |

|||

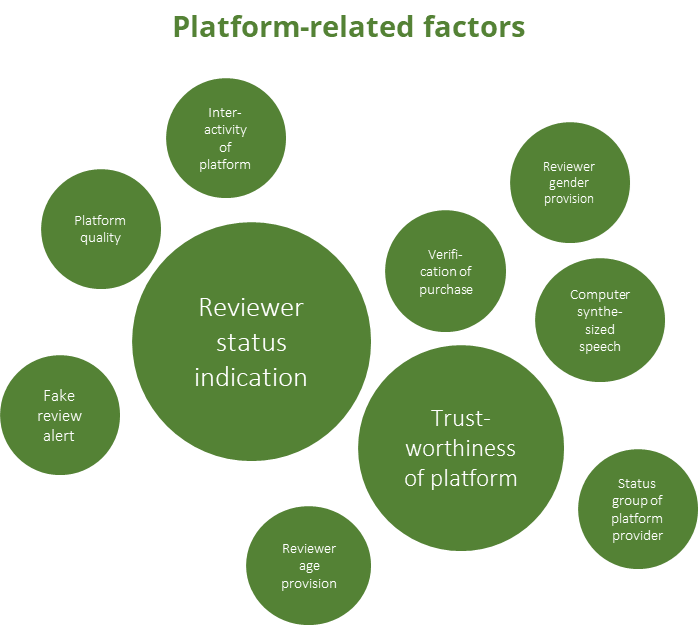

Platform-Related Factors

Research has examined factors that refer to (1) the platform provider as an actor in the online review process and (2) to the information that a platform offers about other actors. For example, platforms might use algorithms to create meta-information, such as marking suspected non-authentic reviews and reporting the status of a platform user. An understanding of studied platform factors can be gained from Table 8.

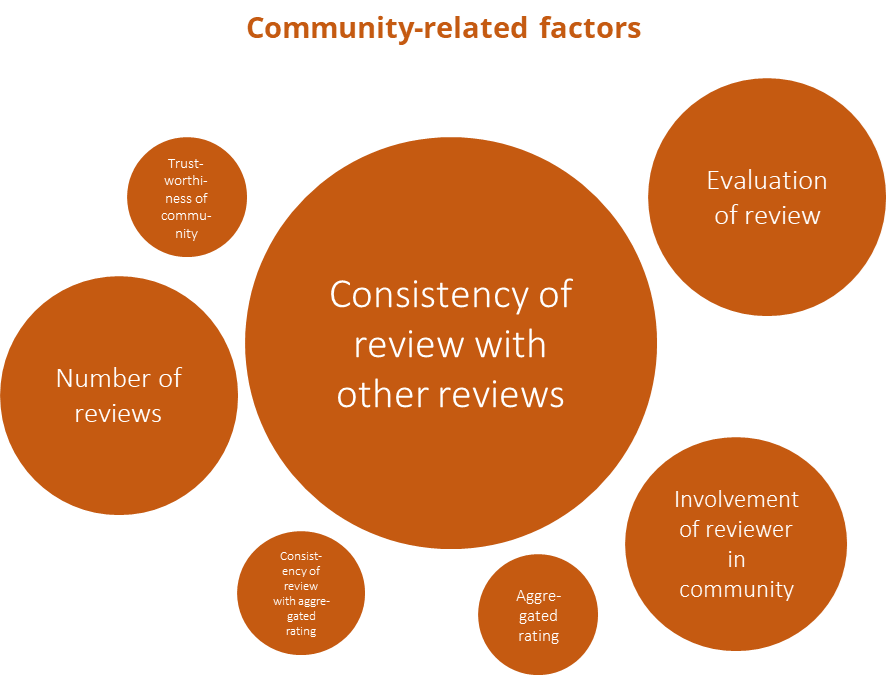

Community-Related Factors

With regard to the community, research has focused on two different types of factors: (1) meta-information provided by the community that relates to the quality assessment of the specific review via comments or recommendation ratings (e.g., usefulness and helpfulness), and (2) context information that is derived from considering the specific review and its author within the platform environment, such as the consistency of the specific review with other reviews on the same object or the total number of reviews on the object. Table 9 provides an overview on examined community factors.

Table 8. Platform-Related Factorsa.

|

Factor |

Effect on Trust |

Articleb |

|

|

Platform quality extent to which the platform is perceived as qualitative, e.g., “well-organized,” “guarantees user privacy” |

+ |

for high quality |

Filieri et al. (2015) |

|

Trustworthiness of platform extent to which the platform is credible, e.g., “trustworthy,” “believable” |

+ |

for high trustworthiness |

Hsiao et al. (2010); J. Lee et al. (2011) |

|

0 |

for high trustworthiness |

J. Lee and Hong (2019) |

|

|

Reviewer status indication platform provides indication of reviewer status, e.g., “top reviewer” |

+ |

for indicated high status |

Banerjee et al. (2017); X. Wang et al. (2015) |

|

0 |

for indicated high status |

Willemsen et al. (2012) |

|

|

Reviewer age provision platform provides age of reviewer |

+ |

if opinion seeker recalls age |

Su et al. (2017) |

|

Reviewer gender provision platform provides gender of reviewer |

+ |

if opinion seeker recalls gender |

Su et al. (2017) |

|

Verification of purchase platform verifies that reviewer has experience with the reviewed option |

+ |

for verification |

Clare et al. (2018) |

|

Interactivity of platform extent to which platform provides interactive features |

+ |

for high interactivity |

Hajli (2018) |

|

Computer synthesized speech computer voice reads review text aloud |

0 |

for computer synthesized speech |

Bartosiak (2021) |

|

Note. Effects on trust are indicated as follows: + indicates a significant positive effect of factor on trust in the online review process; - indicates a significant negative effect of factor on trust in the online review process; 0 indicates that there is no significant effect of factor on trust in the online review process. aFor table including interactions, see Appendix B, Table B4. bFor full references, see Appendix A. |

|||

Table 9. Examined Community-Related Factorsa.

|

Factor |

Effect on Trust |

Articleb |

|

|

Number of reviews total number of reviews or comparisons of high and low numbers of reviews |

+ |

for high number of reviews |

Flanagin and Metzger (2013); Hong and Pittman (2020); Hsiao et al. (2010) |

|

Aggregated rating average rating accumulated through each reviewer’s contribution |

0 |

for lower ratings |

Hong and Pittman (2020) |

|

Consistency of review with other reviews extent to which review accords with other reviews or comments, “consistent,” “similar,” “seem to say the same thing” |

+ |

for high consistency |

C. M.-Y. Cheung et al. (2012); M. Y. Cheung et al. (2009); Clare et al. (2018); Doh and Hwang (2009); Filieri (2016); Hong and Park (2012); Luo et al. (2014; 2015); Van Der Heide and Lim (2016) |

|

- |

for low consistency |

Baker and Kim (2019) |

|

|

- |

for high consistency |

Munzel (2015) |

|

|

Consistency of review with aggregated rating extent to which review accords with average rating |

+ |

stronger for high consistency |

Hong and Pittman (2020) |

|

Evaluation of review extent to which the community evaluated the review positively or negatively, e.g., marking it as “helpful,” “highly rated by other members” |

+ |

for positive evaluation |

M. Y. Cheung et al. (2009); Lis (2013); Luo et al. (2014, 2015) |

|

Trustworthiness of community extend to which the community is trustworthy |

+ |

for high trustworthiness |

J. Lee and Hong (2019) |

|

Involvement of reviewer in community extent to which reviewer is involved in community, e.g., has many friends or followers |

+ |

for high involvement in community |

Banerjee et al. (2017); Xu (2014) |

|

Note. Effects on trust are indicated as follows: + indicates a significant positive effect of factor on trust in the online review process; - indicates a significant negative effect of factor on trust in the online review process; 0 indicates that there is no significant effect of factor on trust in the online review process. aFor table including interactions, see Appendix B, Table B5. bFor full references, see Appendix A. |

|||

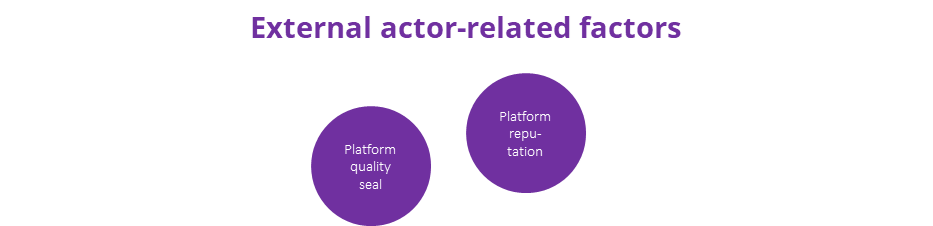

External Actors-Related Factors

External actors have only occasionally been considered in the field. The little interest in these factors is not surprising, given that external actors remain outside the core online review process. Table 10 summarizes the findings on this factor category.

Table 10. Examined External Actor-Related Factorsa.

|

Factor |

Effect on Trust |

Articleb |

|

|

Platform quality seal quality seal award to platform by third party |

+ |

for awarded seals |

Munzel (2015) |

|

Platform reputation general reputation of platform |

+ |

for good reputation |

Hsiao et al. (2010) |

|

Note. Relations are indicated as follows: + denotes a significant positive relation between factor and trust in the online review process; - denotes a significant negative impact of factor on trust in the online review process; 0 denotes no significant impact of factor on trust in the online review process. aFor table including interactions, see Appendix B, Table B6. bFor full references, see Appendix A. |

|||

Opinion Seeker-Related Factors

Individual characteristics of the opinion seeker can be associated with their willingness to trust. Studies examined the effects of knowledge, states, and, most often, traits on trust in online review contexts (see Table 11).

Table 11. Examined Opinion Seeker-Related Factorsa.

|

Factor |

Effect on Trust |

Articleb |

|

|

Age of opinion seeker |

0 |

for age |

Reimer and Benkenstein (2016); X. Wang et al. (2015) |

|

Gender of opinion seeker

|

0 |

for gender |

Reimer and Benkenstein (2016); X. Wang et al. (2015); Xu (2014) |

|

+ |

stronger for female users than for male users |

Prendergast et al. (2018) |

|

|

Race of opinion seeker |

0 |

for race |

Xu (2014) |

|

Education of opinion seeker formal education of opinion seeker, e.g., school or university education |

0 |

for education |

Cox et al. (2017); Reimer and Benkenstein (2016) |

|

Inertia of opinion seeker extent to which opinion seeker is resistant to changing approaches used to evaluate online reviews |

+

|

for high inertia |

Y.-C. Lee (2014) |

|

Illusion of control of opinion seeker extent to which opinion seeker thinks she/he has the ability to assess the truthfulness of the reviewer properly |

+ |

for high illusion of power |

Y.-C. Lee (2014) |

|

Opinion seeking of opinion seeker extent to which the opinion seeker seeks opinions of others in decision processes |

+ |

for high opinion seeking |

Hussain et al. (2018) |

|

Attitude of opinion seeker toward online reviews extent to which opinion seeker is receptive or skeptical toward online reviews |

0 |

for receptive attitude |

Grabner-Kräuter and Waiguny (2015); Qiu et al. (2012) |

|

+ |

for receptive attitude |

Clare et al. (2018); Mahat and Hanafiah (2020) |

|

|

- |

for skeptical attitude |

Reimer and Benkenstein (2016); Zhang et al. (2019, 2021) |

|

|

Experience of opinion seeker with reviews extent to which opinion seeker has experience with reading or writing online reviews |

0 |

for vast experience |

Filieri et al. (2015)

|

|

+ |

for vast experience |

López and Sicilia (2014) |

|

|

Experience of opinion seeker with online shopping extent to which the opinion seeker has experience with online shopping |

0 |

for high experience |

Bae and Lee (2011) |

|

Internet structural assurance of opinion seeker extent to which the opinion seeker believes that internet structures like regulations or legal recourses safeguard safe activities online |

+ |

for high internet structural assurance |

Zhang et al. (2019) |

|

Internet usage of opinion seeker extent to which the opinion seeker has experience with using the internet |

0 |

for high internet usage |

X. Wang et al. (2015) |

|

Involvement of opinion seeker extent to which opinion seeker is involved with review object category or in handling reviews |

0 |

for high involvement |

Hussain et al. (2018); Jensen and Yetgin (2017); Reimer and Benkenstein (2016); Xu (2014) |

|

Other involvement of opinion seeker |

+ |

for high other involvement |

Hussain et al. (2018)c |

|

Motivation of opinion seeker extent to which the opinion seeker is motivated to consult the review |

+ |

for high motivation |

Chih et al. (2013) |

|

Object knowledge of opinion seeker extent to which opinion seeker possesses knowledge or expertise of reviewed object category |

0 |

for vast object knowledge |

Bae and Lee (2011); Dickinger (2011); Flanagin and Metzger (2013); X. Wang et al. (2015); Willemsen et al. (2012) |

|

+ |

if review corresponds to object knowledge |

M. Y. Cheung et al. (2009); Clare et al. (2018) |

|

|

Disconfirmation with previous reviews extent to which online reviews have afforded good decisions in the past |

- |

for high disconfirmation |

Nam et al. (2020) |

|

Sense of virtual community of opinion seeker extent to which opinion seeker feels a sense of belonging to community, e.g., “I feel membership to this community,” “I feel that I belong” |

+ |

for high sense of virtual community |

Filieri (2016) |

|

Self-worth reinforcement of opinion seeker extent to which reviewer is motivated to write review to gain attention3 |

+ |

for high self-worth reinforcement |

Hussain et al. (2018)d |

|

Platform familiarity of opinion seeker extent to which opinion seeker is familiar with platform |

+ |

for high familiarity |

Casaló et al. (2015) |

|

Note. Effects on trust are indicated as follows: + indicates a significant positive effect of factor on trust in the online review process; - indicates a significant negative effect of factor on trust in the online review process; 0 indicates that there is no significant effect of factor on trust in the online review process. aFor table including interactions, see Appendix B, Table B7. bFor full references, see Appendix A. cHussain et al. (2018) do not specify the concept and items. Referenced sources do not address the concept. dHussain et al. (2018) adopt concept and items from a study on reviewer motives for eWOM contribution. The authors test it as antecedent of eWOM credibility as perceived by an opinion seeker. It is not explained how this concept that refers to reviewers informs the examination of the opinion seeker’s perceptions and how items were possibly adjusted. |

|||

Discussion

Assessment of the State of Research

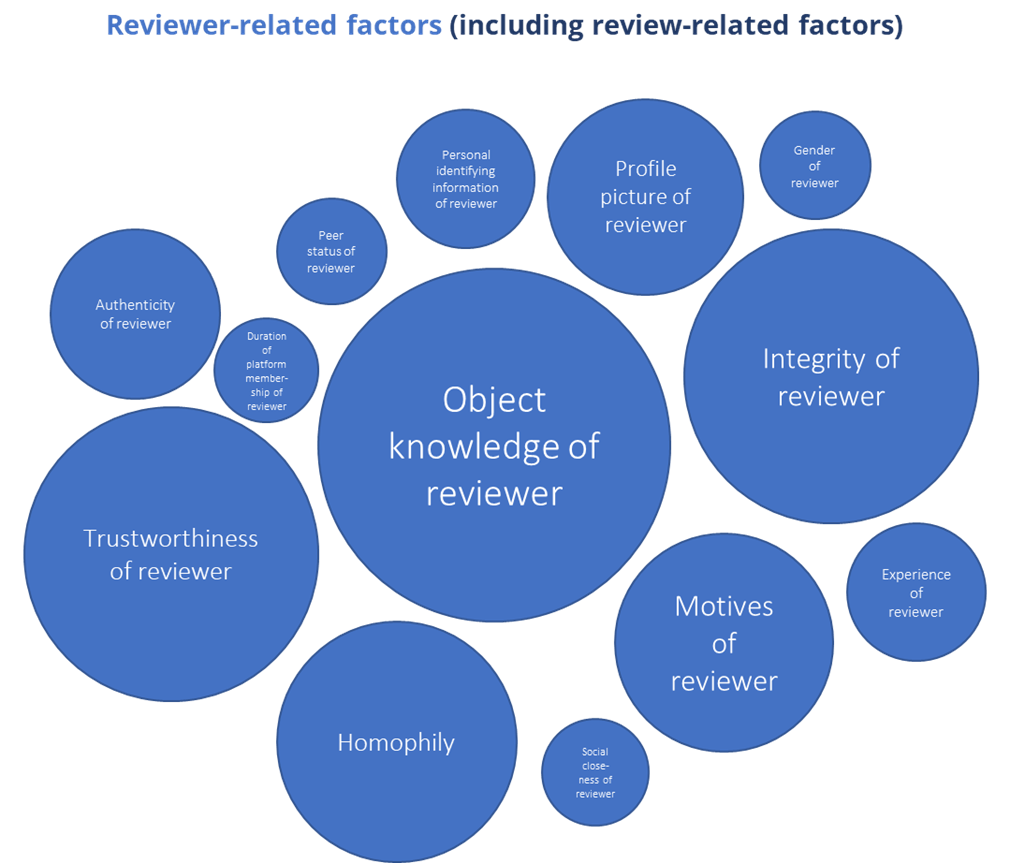

Research on online reviews has examined a considerable number of factors and how they influence trust. Figure 4 provides an overview of examined factors and their frequency of their consideration in research. For most factors, the findings are relatively distinct, whereas the impact of some others is less clear. In general, however, the field appears to be rather fragmented and heterogeneous. Research uses many different operationalizations of trust and is spread over various journals and disciplines.

The Role of Theory

This literature review set out to synthesize and systemize the existing findings. At the same time, however, the review also brings to light some of the field’s theoretical shortcomings and empirical gaps. Based on this analysis, the main shortcoming of previous research is a certain lack of awareness and reflection of the research’s formal object “trust” (or “credibility,” respectively). In general, the reviewed studies do not refer to comprehensive concepts of trust (e.g., Barber, 1983; Giddens, 1990; Kohring, 2004; Lewis & Weigert, 1985; Luhmann, 1968, 1975/2018; Möllering, 2001) that could more accurately capture the complexity of trust relationships and help interpret the results. This finding echoes a longstanding dissatisfaction with the state of empirical trust research in general. Already in 1991, Wrightsman (1991, p. 411) cautioned that “the general concept of trust deserves much more theoretical analysis. Measurement has advanced more rapidly than conceptual clarification.” Ten years later, McKnight and Chervany (2001, p. 38) emphasized that in the absence of such theoretical analysis, “the plethora of empirical studies (…) has brought trust research to so confusing a state.” For the sake of this review article, I adapted the trust concept advanced by Luhmann (1968, 1975/2018) and other authors following in his footsteps (e.g., Kohring, 2004; Meyer & Ward, 2013; Morgner, 2018) to the online review context. This is not to say that the line of reasoning on trust that I drew on is the only possible line for informing research on trust in online review contexts. Every theoretical perspective enables researchers to see certain aspects while obscuring others, as does this. Nevertheless, my conceptual choice permits the identification of some unfortunate consequences that result from the scarce engagement with trust concepts.

Figure 4. Considered Factors in Research on Trust in Online Reviews.

Note. Size of bubble corresponds to frequency of consideration (number of studies) of the factor in research on trust in online reviews.

This review brings to light some of the field’s theoretical shortcomings. First, its scarce engagement with trust concepts leads to a fuzzy understanding of who or what the trustor trusts in. Two trust objects are referenced in the studies, the reviewer and the review itself, and sometimes both. The theoretical foundation proposed here could help to resolve this issue. For example, I argued above that trust refers to the own selectivity of actors and that therefore, trust in online reviews should analytically be attributed to their actions. Unsurprisingly, studies consistently report significant correlations between trustworthiness of reviewer and trust in reviews (e.g., M. Y. Cheung et al., 2009; Clare et al., 2018). Furthermore, the online review process model revealed that there are more actors involved in the process than only reviewer and opinion seeker so that the emergence of trust relationships becomes more complex.

Second, the scarce engagement impacts the possibilities to interpret data in meaningful ways. On the one hand, many scales are imported from research on trust in social contexts other than online reviews. From the perspective of the trust concept adopted in this article, trust depends on expectations that are specific for a social context so that dimensions of trust potentially differ from context to context. This perspective thus increases sensitivity for the risk that imported scales might result in neglecting the peculiarities of trust in online reviews. For instance, the scale used most frequently in the field (Ohanian, 1990, 1991) measures trustworthiness of celebrity endorsers in an advertising and marketing context. It seems at least debatable whether trustors’ expectations about celebrity endorsers are similar to their expectations about online reviewers. For example, different from celebrity endorsers, online reviewers are expected to be independent from the option provider. On the other hand, I found that there is a great heterogeneity of items to measure trust. This heterogeneity makes it difficult to compare findings across studies. The trust concept adopted here can inform the operationalization of trust and protect research from inconsistencies when composing scales of items that relate to trust in different ways, for example to dimensions of trust, reasons to trust, and abstract synonyms of trust (e.g., Ayeh et al., 2013; Dou et al., 2012).