Exploring individuals’ descriptive and injunctive norms of ghosting

Vol.16,No.3(2022)

In this project, we explored descriptive and injunctive norms of ghosting and whether norms differed based on prior experiences with ghosting in romantic relationships. Ghosting is the act of unilaterally ceasing communication with a partner to dissolve a relationship. Perceived norms contribute to intentions and behaviors, but scholars have not previously investigated individuals’ perceived norms of ghosting (i.e., how common they think it is, how they think others react to ghosting). Adults (N = 863) on Prolific, residing in the United States, completed an online survey assessing their knowledge of, experience with, and perceived norms about ghosting in romantic relationships. A portion of these analyses were pre-registered on Open Science Framework. Descriptive norms regarding adults in general (i.e., societal-level) and their friends (i.e., personal-level) differed based on participants’ prior experience with ghosting in romantic relationships. Some injunctive norms at both the societal- and personal-levels also differed based on prior experience with ghosting in romantic relationships. Participants with prior ghosting experience thought ghosting of romantic partners was more common than those with no prior experience. Regardless of prior ghosting experience, participants tended to believe that individuals felt embarrassed/inadequate after being ghosted by a romantic partner. These analyses provide understanding about descriptive and injunctive norms regarding ghosting in romantic relationships and may be helpful to dating app developers in how they frame messaging about ghosting.

descriptive norms; ghosting; injunctive norms; norms; relationship dissolution

Darcey N. Powell

Department of Psychology, Roanoke College

Darcey N. Powell is an Associate Professor of Developmental Psychology at Roanoke College. Her research focuses on transitions in close relationships.

Gili Freedman

Department of Psychology, St. Mary’s College of Maryland

Gili Freedman is an Assistant Professor of Social Psychology at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. Her research focuses on the two-sided nature of social exclusion, gender biases, and how we can use narratives and games to create interventions.

Benjamin Le

Department of Psychology, Haverford College

Benjamin Le is a Professor of Psychology at Haverford College. His research has focused on the maintenance, persistence, and termination of romantic relationships.

Kiping D. Williams

Department of Psychological Sciences, Purdue University

Kipling D. Williams is a Distinguished Professor of Psychological Sciences at Purdue University. His research interests focus on the causes and consequences of ostracism.

Ajzen, I. (2013). Theory of Planned Behaviour Questionnaire. Measurement Instrument Database for the Social Science. https://www.midss.org/sites/default/files/tpb.construction.pdf

Armstrong, E. A., Hamilton, L. T., Armstrong, E. M., & Lotus Seeley, J. (2014). “Good girls”: Gender, social class, and slut discourse on campus. Social Psychology Quarterly, 77(2), 100–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272514521220https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272514521220

Auster, C. J., Faulkner, C. L., & Klingenstein, H. J. (2018). Hooking up and the “ritual retelling”: Gender beliefs in post-hookup conversations with same-sex and cross-sex friends. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 4, Article 2378023118807044. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023118807044

Baxter, L. A. (1982). Strategies for ending relationships: Two studies. Western Journal of Speech Communication, 46(3), 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570318209374082

Blanton, H., & Christie, C. (2003). Deviance regulation: A theory of action and identity. Review of General Psychology, 7(2), 115–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.7.2.115

Borgueta, M. (2016). The psychology of ghosting: Why people do it and a better way to break up. Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lantern/the-psychology-of-ghostin_b_7999858.html

Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2003). Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 64(3), 331–341. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331

Brubaker, J. R., Ananny, M., & Crawford, K. (2014). Departing glances: A sociotechnical account of “leaving” Grindr. New Media & Society, 18(3), 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814542311

Byron, P., & Albury, K. (2018). ‘There are literally no rules when it comes to these things’: Ethical practice and the use of dating/hook-up apps. In A. S. Dobson, B. Robards, & N. Carah (Eds.), Digital intimate publics and social media (pp. 213–229). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97607-5_13

Campo, S., & Cameron, K. A. (2006). Differential effects of exposure to social norms campaigns: A cause for concern. Health Communication, 19(3), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc1903_3

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public areas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015–1026. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015

Collins, E. S., & Spelman, P. J. (2013). Associations of descriptive and reflective injunctive norms with risky college drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(4), 1175–1181. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032828

Collins, T. J., & Gillath, O. (2012). Attachment, breakup strategies, and associated outcomes: The effects of security enhancement on the selection of breakup strategies. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(2), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.01.008

Comunello, F., Parisi, L., & leracitano, F. (2021). Negotiating gender scripts in mobile dating apps: Between affordances, usage norms and practices. Information, Communication & Society, 24(8), 1140–1156. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1787485

Cronbach, L. J. (1955). Processes affecting scores on “understanding of others” and “assumed similarity”. Psychological Bulletin, 52(3), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0044919

Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1960). A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24(4), 349–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0047358

De Meyer, S., Kågesten, A., Mmari, K., McEachran, J., Chilet-Rossell, E., Kabiru, C. W., Maina, B., Jerves, E. M., Currie, C., & Michielsen, K. (2017). “Boys should have the courage to ask a girl out”: Gender norms in early adolescent romantic relationships. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(4), S42–S47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.03.007

De Wiele, C. V., & Campbell, J. F. (2019). From swiping to ghosting: Conceptualizing rejection in mobile dating. In A. Hetsroni & M. Tuncez (Eds.), It happened on Tinder: Reflections and studies on internet-infused dating (pp. 158–175). Institute of Network Cultures.

Engle, J. (2019, January 15). Have you ever been ghosted? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/25/learning/have-you-ever-been-ghosted.html

Etcheverry, P. E., & Agnew, C. R. (2004). Subjective norms and the prediction of romantic relationship state and fate. Personal Relationships, 11(4), 408–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00090.x

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley.

Fitzpatrick, C., & Birnholtz, J. (2018). “I shut the door”: Interactions, tensions, and negotiations from a location-based social app. New Media & Society, 20(7), 2469–2488. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817725064

Freedman, G., Powell, D. N., Le, B., & Williams, K. D. (2019). Ghosting and destiny: Implicit theories of relationships predict beliefs about ghosting. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(3), 905–924. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517748791

Gilovich, T. (1990). Differential construal and the false consensus effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(4), 623–634. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.4.623

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor Books

Goldstein, N. J., & Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Using social norms as a lever of social influence. In A. R. Pratkanis (Ed.), The science of social influence: Advances and future progress (pp. 167–191). Psychology Press.

Hanson, K. R. (2021a). Becoming a (gendered) dating app user: An analysis of how heterosexual college students navigate decision and interactional ambiguity on dating apps. Sexuality & Culture, 25, 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09758-w

Hanson, K. R. (2021b). Collective exclusion: How white heterosexual dating app norms reproduce status quo hookup culture. Sociological Inquiry. 92(S1), 894–918. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12426

Hobbs, M., Owen, S., & Gerber, L. (2017). Liquid love? Dating apps, sex, relationships and the digital transformation of intimacy. Journal of Sociology, 53(2), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783316662718

Hoch, S. J. (1987). Perceived consensus and predictive accuracy: The pros and cons of projection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(2), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.2.221

Hornsey, M. J. (2008). Social identity theory and self-categorization theory: A historical review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00066.x

Horton, H. (2018, October 29). Dating apps crack down on ‘ghosting’, as ‘epidemic’ of ignoring partners puts off users. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/10/29/dating-apps-crack-ghosting-epidemic-ignoring-partners-puts-users/

Keeling, R. P. (2000). Social norms research in college health. Journal of American College Health, 49(2), 53–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480009596284

Kenny, D. A. (1994). Interpersonal perception: A social relations analysis. Guilford.

Klinkenberg, D., & Rose, S. (1994). Dating scripts of gay men and lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality, 26(4), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v26n04_02

Koessler, R. B., Kohut, T., & Campbell, L. (2019a). When your boo becomes a ghost: The association between breakup strategy and breakup role in experiences of relationship dissolution. Collabra: Psychology, 5(1), Article 29. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.230

Koessler, R. B., Kohut, T., & Campbell, L. (2019b). Integration and expansion of qualitative analyses of relationship dissolution through ghosting. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/3kvdx

Kuperberg, A., & Padgett, J. E. (2015). Dating and hooking up in college: Meeting contexts, sex, and variation by gender, partner’s gender, and class standing. Journal of Sex Research, 52(5), 517–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.901284

Larimer, M. E., Turner, A. P., Mallett, K. A., & Geisner, I. M. (2004). Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(3), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203

LeFebvre, L. (2017). Ghosting as a relationship dissolution strategy in the technological age. In N. M. Punyanunt-Carter & J. S. Wrench (Eds.), The impact of social media in modern romantic relationships (pp. 219–235). Lexington Books.

LeFebvre, L. E., Allen, M. Rasner, R. D., Gardstad, S., Wilms, A., & Parrish, C. (2019). Ghosting in emerging adults’ romantic relationships: The digital dissolution disappearance strategy. Imagination, Cognition and Personality: Consciousness in Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice, 39(2), 125–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276236618820519

LeFebvre, L., & Fan, X. (2020). Ghosted? Navigating strategies for reducing uncertainty and implications surrounding ambiguous loss. Personal Relationships, 27(2), 433–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12322

LeFebvre, L. E., Rasner, R. D., & Allen, M. (2020). “I guess I’ll never know…”: Non-initiators account-making after being ghosted. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 25(5), 395–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2019.1694299

Manning, M. (2009). The effects of subjective norms on behaviour in the Theory of Planned Behavior: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48, 649-705. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466608X39313

Manning, J., Denker, K. J., & Johnson, R. (2019). Justifications for ‘ghosting out’ of developing or ongoing romantic relationships: Anxieties regarding digitally-mediated romantic interaction. In A. Hetsroni & M. Tuncez (Eds.), It happened on Tinder: Reflections and studies on internet-infused dating (pp. 114–132). Institute of Network Cultures.

Montaño, D. E., & Kasprzyk, D. (2008). Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 67–96). Jossey-Bass.

Navarro, R., Larrañaga, E., Yubero, S., & Víllora, B. (2020). Psychological correlates of ghosting and breadcrumbing experiences: A preliminary study among adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), Article 1116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031116

Navarro, R., Larrañaga, E., Yubero, S., & Víllora, B. (2021). Individual, interpersonal and relationship factors associated with ghosting intention and behaviors in adult relationships: Examining the associations over and above being a recipient of ghosting. Telematics and Informatics, 57, Article 101513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101513

Pancani, L., Mazzoni, D., Aureli, N., & Riva, P. (2021). Ghosting and orbiting: An analysis of victims’ experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(7), 1987–2007. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211000417

Paulhus, D. L., & Reid, D. B. (1991). Enhancement and denial in socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(2), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.2.307

Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S., & Acquisti, A. (2017). Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.01.006

Potârca, G., Mills, M., & Neberich, W. (2015). Relationship preferences among gay and lesbian online daters: Individual and contextual influences. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(2), 523–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12177

Powell, D. N., Freedman, G., Williams, K. D., Le, B., & Green, H. (2021). A multi-study examination of the role of attachment and implicit theories of relationships in ghosting experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(7), 2225–2248. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211009308

Pruchniewska, U. (2020). “I like that it’s my choice a couple different times”: Gender, affordances, and user experience on bumble dating. International Journal of Communication, 14, 2422–2439. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/12657

Reed, E., Silverman, J. G., Raj, A., Decker, M. R., & Miller, E. (2011). Male perpetration of teen dating violence: Associations with neighborhood violence involvement, gender attitudes, and perceived peer and neighborhood norms. Journal of Urban Health, 88(2), 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9545-x

Rimal, R. N., & Real, K. (2003). Understanding the influence of perceived norms on behavior. Communication Theory, 13(2), 184–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00288.x

Rivis, A., & Sheeran, P. (2003). Descriptive norms as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analysis. Current Psychology, 22(3), 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-003-1018-2

Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13(3), 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(77)90049-X

Schultz, P. W., Nolan, J. M., Cialdini, R. B., Goldstein, N. J., & Griskevicius, V. (2007). The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychological Science, 18(5), 429–434. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40064634

Sharabi, L. L., & Timmermans, E. (2021). Why settle when there are plenty of fish in the sea? Rusbult’s investment model applied to online dating. New Media & Society, 23(10), 2926–2946. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820937660

Simon, T. R., Miller, S., Gorman-Smith, D., Orpinas, P., & Sullivan, T. (2010). Physical dating violence norms and behavior among sixth-grade students from four U.S. sites. Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(3), 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431609333301

Sobieraj, S., & Humphreys, L. (2022). The Tinder games: Collective mobile dating app usage and gender conforming behavior. Mobile Media & Communication, 10(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579211005001

Sun Park, H., & Smith, S. W. (2007). Distinctiveness and influence of subjective norms, personal descriptive and injunctive norms, and societal descriptive and injunctive norms on behavioral intent: A case of two behaviors critical to organ donation. Human Communication Research, 33(2), 194–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2007.00296.x

Statista. (2021, May). Online dating in the United States – Statistics & facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/2158/online-dating/#dossierKeyfigures

Thomas, J. O., & Dubar, R. T. (2021). Disappearing in the age of hypervisibility: Definition, context, and perceived psychological consequences of social media ghosting. Psychology of Popular Media, 10(3), 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000343.supp

Timmermans, E., Hermans, A-M., Opree, S. J. (2020). Gone with the wind: Exploring mobile daters’ ghosting experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(2), 783-801. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520970287

Tom Tong, S., & Walther, J. B. (2011). Just say “no thanks”: Romantic rejection in computer-mediated communication. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28(4), 488–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407510384895

Vogels, E. A. (2020, February 6). 10 facts about Americans and online dating. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/02/06/10-facts-about-americans-and-online-dating/

Zhang, J., & Yasseri, T. (2016). What happens after you both swipe right: A statistical description of mobile dating communications. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1607.03320

Zou, X., Tam, K.-P., Morris, M. W., Lee, S.-I., Lau, I. Y.-M., & Chiu, C.-y. (2009). Culture as common sense: Perceived consensus versus personal beliefs as mechanisms of cultural influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(4), 579–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016399

Authors’ Contribution

Darcey N. Powell: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, resources, visualization, writing - original, writing – reviewing and editing. Gili Freedman: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, resources, writing – reviewing and editing. Benjamin Le: conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, writing - reviewing and editing. Kipling D. Williams: conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, writing – reviewing and editing.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

June 15, 2021

Revisions received:

January 18, 2022

February 28, 2022

Accepted for publication:

June 13, 2022

Editor in charge:

Michel Walrave

Introduction

Ghosting, the act of cutting off all communication with a partner without informing them of your intention to do so and ignoring their attempts to reconnect (Freedman et al., 2019; Koessler et al., 2019b, LeFebvre, 2017), has received a great deal of attention in the popular press. Several press articles have discussed how common the phenomenon is among unmarried individuals (Borgueta, 2016; Engle, 2019). However, research on the topic has reported wide ranges for the frequency of ghosting (Freedman et al., 2019; Koessler et al., 2019b; LeFebvre et al., 2019; Timmermans et al., 2020), especially in romantic relationships. For example, in a sample of emerging adults aware of the term of ghosting, only 4% of the sample had no prior experiences with ghosting (LeFebvre et al., 2019). However, in broader samples of adults, more than half of the participants had no prior experiences with ghosting (Freedman et al., 2019). As such, it is unclear how common individuals believe ghosting among romantic partners to be. Additionally, while research has explored how individuals react to ghosting (Koessler et al., 2019a; LeFebvre & Fan, 2020; Timmermans et al., 2020), it is unclear how individuals perceive others’ reactions to ghosting. Therefore, the aims of this study were to explore the norms individuals hold about rates of and reactions to ghosting romantic partners. Understanding the norms individuals possess about ghosting is important as perceived norms may contribute to individuals’ intentions for engaging in future ghosting behaviors, as well as how they evaluate their own ghosting behaviors.

Perceived Norms and Behavior

Though individuals’ perceived norms do not wholly predict behavior (Rimal & Real, 2003), norms can influence engagement in behaviors (e.g., Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Goldstein & Cialdini, 2007; Manning, 2009; Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2008; Rivis & Sheeran, 2003). Specifically, norms describe how individuals should act or do act (Rimal & Real, 2003). However, norms are based on internalized information and are not always accurate representations of others’ thoughts and behaviors (Rimal & Real, 2003). Moreover, there are several types of norms that individuals may hold. For example, subjective norms represent individuals’ perceptions of the extent to which others want them to engage or would support them in engaging in the behavior or action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Sun Park & Smith, 2007). Injunctive norms represent individuals’ perceptions of what behavior or action they ought to take in a specific situation based on beliefs about morally appropriate conduct (Goldstein & Cialdini, 2007). Inherently, then, injunctive norms also provide information on penalties that may be enforced for not complying with the general course of action in a specific situation (Rimal & Real, 2003). Descriptive norms represent individuals’ perceptions of what behavior or action is typically taken by others in that specific situation (Cialdini et al., 1990; Rimal & Real, 2003). As such, descriptive norms also provide information on what proportion of individuals do not take that action in the specific situation (Rimal & Real, 2003). This study specifically focused on individuals’ injunctive and descriptive norms related to ghosting.

Deviance regulation theory asserts that individuals diverge from norms when it may be advantageous to do so to create a positive perception of themselves, and individuals avoid diverging from norms when it could disadvantage their reputation (Blanton & Christie, 2003). Thus, it is imperative to understand what is perceived to be normative by the target individual (see Goldstein & Cialdini, 2007). By understanding individuals’ perceptions of what is normative, one is able to predict what actions they may choose in a specific situation and instances in which they may deviate from the norm to foster a more positive perception of themselves. Therefore, both injunctive and descriptive norms are likely important for understanding individuals’ ghosting behavior.

Like many other theories in social psychology (Crowne & Marlow, 1960; Goffman, 1959; Paulhus & Reid, 1991), social identity and self-categorization theories posit that individuals’ actions are often motivated by seeking a positive perception of themselves (Hornsey, 2008). Moreover, how others in a specific context behave can contribute to what individuals perceive as actions that promote positive perceptions in that specific context (Hornsey, 2008). Additionally, it is important to note that, norms can occur at the personal level (perceptions of those important to the target individual) and at the societal level (perceptions of others, in general; Sun Park & Smith, 2007). Thus, social identity and self-categorization theories (see Goldstein & Cialdini, 2007) suggest that individuals’ perceptions of their friends’ behaviors (i.e., norms at the personal-level) should have more influence on their actual behavior than their perceptions of the average adults’ behaviors (i.e., at the societal-level). As such, this study examined individuals’ societal- and personal-level norms.

Additionally, norms predict behavior across a range of contexts. For example, emerging adults’ norms related to alcohol consumption in college are associated with their own drinking behaviors in college (Borsari & Carey, 2003; E. S. Collins & Spelman, 2013; Larimer et al., 2004). Additionally, adolescents’ norms related to dating violence have been associated with their own engagement in such behaviors (Reed et al., 2011; Simon et al., 2010). Within the realm of romantic relationships, researchers have explored the impact of perceived norms on the initiation and continuation of romantic relationships. For example, cross-cultural research on adolescents demonstrated early development of norms about the expectations and behaviors of boys and girls in romantic relationships (De Meyer et al., 2017). Furthermore, longitudinal research on emerging adults revealed the impact of norms on their commitment to their romantic relationship, and especially in situations of low relationship dependence (i.e., low satisfaction, low investment, and high quality of alternatives; Etcheverry & Agnew, 2004). However, researchers have not thoroughly explored perceived norms around romantic relationship dissolution strategies.

Ghosting as a Romantic Relationship Dissolution Strategy

To end a romantic relationship, there are many strategies that individuals can use. One strategy that has gained a great deal of attention recently in both the popular and scholarly press is ghosting. Ghosting can be conceptualized as an extreme form of the avoidance and withdrawal tactic for romantic relationship dissolution (Baxter, 1982; T. J. Collins & Gillath, 2012). Ghosting tends to be perceived by initiators as an easier way to end a relationship with a romantic partner (LeFebvre et al., 2019; Manning et al., 2019; Thomas & Dubar, 2021). However, like other avoidance and withdrawal tactics (T. J. Collins & Gillath, 2012), it is generally perceived to be less acceptable than other methods of ending a relationship (Freedman et al., 2019). Moreover, recipients of ghosting experience more distress, uncertainty, and other negative emotions than when the relationship is ended more directly (Koessler et al., 2019a; LeFebvre & Fan, 2020; LeFebvre et al., 2020; Pancani et al., 2021). Additional research has more broadly explored individuals’ motivations to use ghosting (Koessler et al., 2019a, 2019b; LeFebvre et al., 2019, 2020; Manning et al., 2019; Timmermans et al., 2020) and various correlates of ghosting behaviors (Freedman et al., 2019; Navarro et al., 2020, 2021; Powell et al., 2021). Most of this research, though, has predominately compared individuals—mostly emerging adults—who have ghosted to those who have not, and those who have been ghosted to those who have not; less research has accounted for the fact that some individuals may have both ghosted and been ghosted (e.g., LeFebvre et al., 2019; Manning et al., 2019; Powell et al., 2021).

Furthermore, only one study has quantitatively examined perceived acceptability of ghosting. Freedman and colleagues (2019) reported that individuals were more likely to indicate that ghosting was a more acceptable way to end short-term or newly initiated relationships than long-term relationships. While the article referred to acceptability as a subset of individuals’ “perceptions of ghosting,” the items regarding acceptability could also be interpreted as subjective norms. As such, information regarding descriptive and injunctive norms remains missing from the literature

Technology’s Role in Ghosting

It is believed that ghosting has become a more regularly implemented form of relationship dissolution due to the rise in technology-mediated communication (LeFebvre, 2017). Contributing to the high rates at which couples engage in technology-mediated communication is the increasing frequency with which prospective partners meet and get acquainted through dating apps (DeWiele & Campbell, 2019; Statista, 2021; Vogels, 2020). Dating apps have employed a gamification approach to encourage consistent usage (DeWiele & Campbell, 2019; Hanson, 2021a; Sobieraj & Humphreys, 2022), and, as a result, many interactions are brief and without much depth (Hobbs et al., 2017; Zhang & Yasseri, 2016). Furthermore, many users acknowledge a “hook-up” culture and more direct expressions of sexual intentions associated with dating apps, and this is especially true for men’s stated motives for using dating apps (Fitzpatrick & Birnholtz, 2018; Hanson, 2021a, 2021b; Hobbs et al., 2017).

Focusing on relationship dissolution, qualitative research has found that some users find it easier to ghost connections on dating apps than to directly reject them (DeWiele & Campbell, 2019; Timmermans et al., 2020), and many users perceive ghosting to be quite common and somewhat expected on dating apps (DeWiele & Campbell, 2019; Timmermans et al., 2020; Thomas & Dubar, 2021). Users’ options to block or “unmatch” with a prospective partner and users’ patterns of deleting and reinstalling apps for various reasons (Brubaker et al., 2016; DeWiele & Campbell, 2019; Sharabi & Timmermans, 2021) both lead to a high rate of unanswered messages (Tom Tong & Walther, 2010; Zhang & Yasseri, 2016). Additionally, one reason that users may block or “unmatch” with prospective partners, thereby ghosting them, is in response to undesirable or inappropriate behaviors (Thomas & Dubar, 2021; Timmermans et al., 2020).

Furthermore, prior experimental research demonstrated that individuals are more likely to be polite in their online rejection of a prospective mate if they share acquaintances or expect future interactions (Tom Tong & Walther, 2010), both of which may be less likely when partners meet through a dating app. However, the research also noted that many participants indicated they would have simply ignored the online request for a date (Tom Tong & Walther, 2010), thereby ghosting the prospective partner. Moreover, they found that their participants were interested in using a pre-written “no thanks” option to reject a prospective partner when contacted online via a dating site by someone they had not met before or with whom they did not share acquaintances (Tom Tong & Walther, 2010). Furthermore, Tom Tong and Walther (2010) asserted that online daters may be more likely to use a pre-written rejection than ghost a prospective partner or write their own tailored rejection. Acknowledging the prevalence of ghosting on dating apps (De Wiele & Campbell, 2019; Thomas & Dubar, 2021; Timmermans et al., 2020), one app implemented a notification system to discourage users from ghosting others (Horton, 2018). That dating app’s implementation supports the idea that the setting in which messaging is provided to change behavior should match the setting in which the behavior occurs (Goldstein & Cialdini, 2007). Understanding individuals’ norms for ghosting could foster the development of campaigns to reduce individuals’ intentions to use ghosting, as well as help to tailor the messaging provided to dating app users when attempting to reduce the frequency of ghosting.

The Present Study

The present study contributes to the current literature on ghosting in three specific ways. Primarily, this study provides a first glimpse into individuals’ injunctive and descriptive norms of a specific relationship dissolution strategy (i.e., ghosting) at the personal- and societal-levels. With this focus, we add to the field’s understanding of how ghosting experiences have shaped individuals’ perceptions and behaviors within the realm of relationship dissolution. Moreover, the present study continues to refine the literature by comparing individuals who have both ghosted and been ghosted, who have only ghosted, who have only been ghosted, and who have no prior experience with ghosting. Furthermore, the present study broadens the literature by sampling a wide array of adults, encompassing various ages and various relationship experiences, rather than focusing solely on emerging adults’ experiences as most prior research on ghosting has done.

These data are from a larger project on individual differences in ghosting which was pre-registered on Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/tscd8). The analyses in the present study explored individuals’ injunctive and descriptive norms pertaining to the act of ghosting and examine whether norms differed based on their prior experiences with ghosting. A subset of the conducted analyses were pre-registered on OSF. Specifically, it was hypothesized that:

H1: ghosters will think that others (personal-level and societal-level) feel more positively about ghosting than those who have neither ghosted nor been ghosted.

H2: that ghostees will think that others (personal-level and societal-level) feel less positively about ghosting than those who have neither ghosted nor been ghosted.

Additional analyses explored whether descriptive norms differed based on individuals’ prior experience with ghosting (i.e., only ghosted, only been ghosted, both, or neither).

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from Prolific if they were over the age of 18, from the United States, and had an approval rate at or above 85%. Although 984 individuals began the study, 41 (4.2%) failed the first attention check (Phrasing: It is important that you pay attention to this study. Can you drag the bar to the ninety percent mark?) and 39 (4%) did not answer it. Additionally, of the 984 individuals, 32 (3.3%) failed the second attention check (Phrasing: In order to facilitate our research we are interested in knowing certain factors about you. Specifically, we are interested in whether you actually take the time to read the directions; if you do not read the instructions and then you answer questions, we will have trouble interpreting the data. So, in order to demonstrate that you have read the instructions, please click on "I have read the instructions" at the bottom of the list of states in order to proceed. Do not click on the state you are from. Thank you very much.) and 49 (5%) did not answer it. Lastly, of the 984 individuals, 13 (1.3%) stated that we should not use their data (Phrasing: It is very important that we have high-quality data, and the accuracy of responses will directly impact our research findings, so if you feel that we should not use your data for any reason, click "no" below, and we will remove your responses from the study with no penalty to you— you'll still be paid! It's just important that we have truthful and accurate responses here. Thank you for your time. Should we use your data from this study?) and 39 (4%) did not answer the question. Individuals who did not answer or incorrectly answered either attention check, or indicated that we should not use their data were removed for analysis. Therefore, the analytic sample consisted of 863 participants (Mage = 33.35 years, SDage = 11.63; 50.9% men, 47.5% women, 1.3% other, 0.3% did not disclose; 74.3% heterosexual, 12.17% bisexual, 5.9% gay, 5% lesbian, 1.85% asexual, 0.78% did not disclose; 67.8% White, 8.3% Asian/Asian American, 7.8% African/African-American/Black, 6.1% Hispanic/Latino, 6.4% Multiracial, 3.5% other or did not disclose). A majority of the sample was either single (42.1%) or married/in a long-term committed relationship (33.4%; 6.6% dating casually, 15.3% dating seriously, 2.5% engaged, 0.1% did not answer). Furthermore, while most participants were not currently students (76.9%; 0.6% in high school, 14.9% in college, 6.0% in grad school, 1.3% in professional school, 0.2% did not disclose), most participants had some college experience (26.0%) or had earned a degree (9.3% associate’s degree, 38.4% bachelor’s degree, 12.2% master’s degree, 2.5% professional or doctoral degree; 1.0% less than high school, 10.7% high school degree/GED). This sample is similar to the demographic distribution of Prolific users (Peer et al., 2017).

Measures

Knowledge of Ghosting

Participants indicated whether they had heard of ghosting (Yes/No) and their prior experience with ghosting (Selected one): whether they had ever been ghosted by a romantic partner, had ever ghosted a romantic partner, both been ghosted by and ghosted a romantic partner, or had neither been ghosted by nor ghosted a romantic partner.

Descriptive Norms of Ghosting

A series of questions were developed, guided by Ajzen (2013), to gauge participants’ descriptive norms of ghosting and of being ghosted at both the societal- and personal-level. Questions at the societal-level asked about adults more broadly, whereas questions at the personal-level asked about friends (see Table 1). All questions were answered using a sliding bar scale of 0 to 100 in which participants could select whole number responses. See supplemental document on OSF comparing participants’ responses across the descriptive norms.

Table 1. Descriptive Norms.

|

Question |

M (SD) |

Mdn |

Mode |

|

Ghosted a Romantic Partner (Societal-Level) |

|||

|

What percentage of the adult population do you believe has previously ghosted a romantic partner? |

39.44 (21.35) |

35 |

30 |

|

What percentage of the adult population do you believe would be willing to ghost a romantic partner? |

49.44 (23.35) |

50 |

50 |

|

How many times do you think an average individual ghosts a romantic partner during their adult life? |

10.30 (16.38) |

3 |

2 |

|

Ghosted a Romantic Partner (Personal-Level) |

|||

|

What percentage of your friends do you believe have previously ghosted a romantic partner? |

29.87 (26.39) |

23 |

10 |

|

What percentage of your friends do you believe would be willing to ghost a romantic partner? |

39.08 (28.95) |

35 |

50 |

|

How many times, on average, do you think your friends have ghosted a romantic partner during their adult life? |

9.17 (16.43) |

2 |

1 |

|

Been Ghosted by a Romantic Partner (Societal-Level) |

|||

|

What percentage of the adult population do you think has been ghosted by a romantic partner? |

39.53 (22.55) |

35 |

50 |

|

How many times do you think an average individual is ghosted by a romantic partner during their adult life? |

11.16 (18.31) |

3 |

2 |

|

Been Ghosted by a Romantic Partner (Personal-Level) |

|||

|

What percentage of your friends do you think has previously been ghosted by a romantic partner? |

28.15 (24.87) |

20 |

10 |

|

How many times, on average, do you think your friends have been ghosted by a romantic partner during their adult life? |

9.49 (16.47) |

2 |

1 |

Injunctive Norms of Ghosting

A series of questions were developed, guided by Ajzen (2013), to gauge participants’ injunctive norms of ghosting and of being ghosted at both the societal- and personal-level (see Table 2). All questions were answered using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree). See supplemental document on OSF comparing participants’ responses across the injunctive norms.

Table 2. Injunctive Norms.

|

Question |

M(SD) |

Mdn |

Mode |

|

Ghosted a Romantic Partner (Societal-Level) |

|||

|

The average individual feels guilty when they ghost a romantic partner. |

4.75 (1.46) |

5 |

5 |

|

The average individual feels relieved when they ghost a romantic partner. |

4.48 (1.48) |

5 |

5 |

|

The average individual is supportive of others ghosting a romantic partner. |

3.21 (1.39) |

3 |

3 |

|

Ghosted a Romantic Partner (Personal-Level) |

|||

|

My friends would feel guilty if they ghost a romantic partner. |

5.03 (1.41) |

5 |

5 |

|

My friends would feel relieved if they ghost a romantic partner. |

4.22 (1.47) |

4 |

5 |

|

My friends would be supportive of me ghosting a romantic partner. |

3.45 (1.62) |

3 |

2 |

|

Been Ghosted by a Romantic Partner (Societal-Level) |

|||

|

The average individual probably feels embarrassed when ghosted by a romantic partner. |

5.68 (1.27) |

6 |

6 |

|

The average individual probably feels relieved when ghosted by a romantic partner. |

2.53 (1.31) |

2 |

2 |

|

Been Ghosted by a Romantic Partner (Personal-Level) |

|||

|

My friends would feel inadequate if ghosted by a romantic partner. |

5.34 (1.23) |

5 |

6 |

|

My friends would feel relieved if ghosted by a romantic partner. |

2.55 (1.27) |

2 |

2 |

Demographics

Participants answered questions about their age, gender, ethnicity, education, sexual orientation, and relationship status.

Procedure

These data are from a larger study on individual differences in ghosting experiences (i.e., only had ghosted, only had been ghosted, both, or neither) collected in October of 2018. Participants were first asked if they had heard of ghosting. Regardless of how they answered, they were presented with the following information: For the purposes of this study, ghosting is defined as the following: “When one ends a romantic relationship or friendship by cutting off all contact (including social media) and ignoring attempts to reach out”. Participants were then asked to indicate their prior experience with ghosting. Participants then answered a series of questions on their norms about ghosting. Finally, participants shared demographic information and were asked whether their data should be used for analysis. On average, the full survey took participants almost 12 minutes to complete (M = 11.94 minutes, SD = 11.47, Mdn = 9.92). After data were collected, participants were compensated $1.19 for their participation.

Results

Ghosting Knowledge and Experiences

A majority of the sample (85.5%) indicated that they had heard of ghosting (14.5% had not). However, slightly less than half had some prior experience with ghosting: 19.8% had only been ghosted by a former romantic partner (i.e., Only Ghostee), 8.6% had only ghosted a former romantic partner (i.e., Only Ghoster), 17.5% had been both ghosted by and ghosted a former romantic partner (i.e., Both); 54% had no prior experiences with ghosting (i.e., Neither; one person did not answer the question).

Descriptive Norms

Individual Differences in Societal-Level Norms

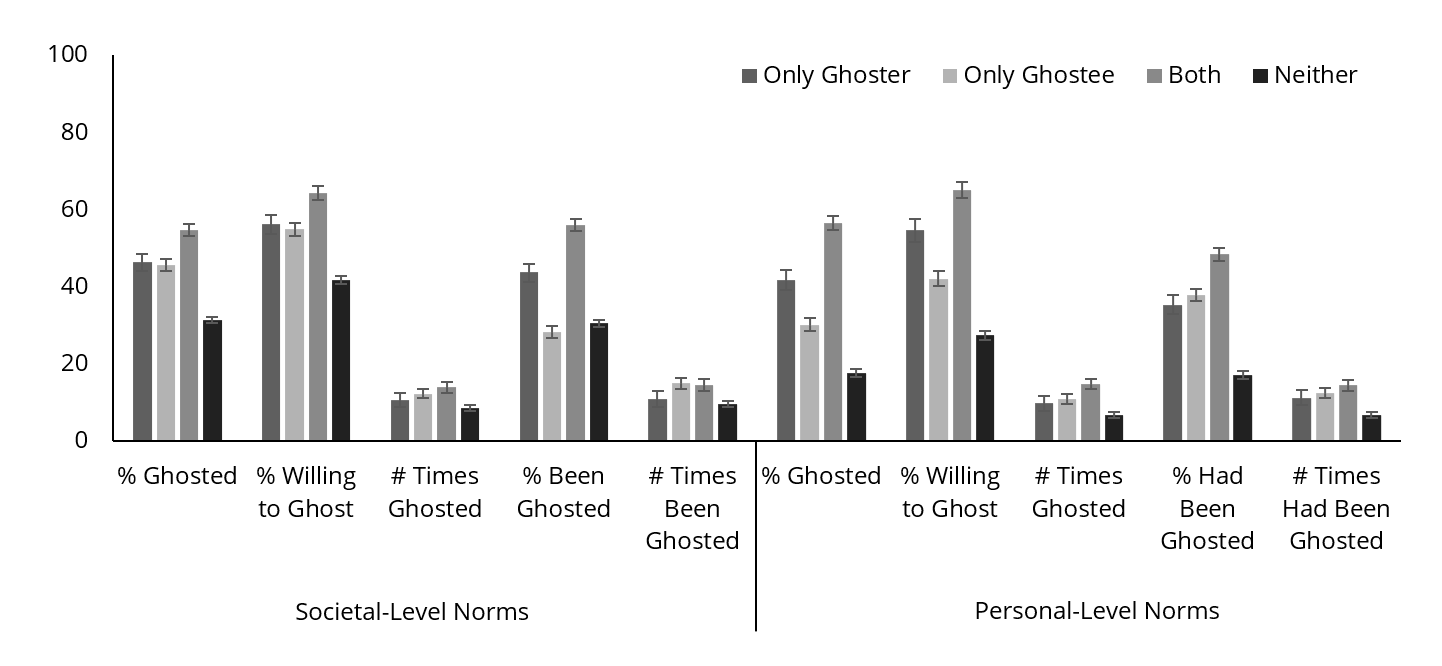

An exploratory MANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed differences in participants’ societal-level descriptive norms based on their prior experience with ghosting, Wilk’s λ = .76, F(15, 2344) = 16.43, p < .001, ηp2 = .09. Specifically, differences were demonstrated across all norms: proportion who ghosted, F(3, 853) = 67.64, p < .001, ηp2 = .19, proportion willing to ghost, F(3, 853) = 48.75, p < .001, ηp2 = .15, times ghosted, F(3, 853) = 5.16, p = .018, ηp2 = .02, proportion who had been ghosted, F(3, 853) = 76.78, p < .001, ηp2 = .21, and times had been ghosted, F(3, 853) = 5.11, p = .002, ηp2 = .02 (see Figure 1). For all societal-level norms (i.e., adults, in general), the Both group held higher descriptive norms than the Neither group (p’s ≤ .022). Additionally, the Both group believed more adults had ghosted and that a larger proportion had been ghosted than the Only Ghoster and the Only Ghostee groups (p’s ≤ .014). The Both group also believed more adults were willing to ghost than the Only Ghostee group (p = .001). The Only Ghoster and Only Ghostee groups believed more adults had ghosted, were willing to ghost, and had been ghosted than the Neither group (p’s < .001). Finally, the Only Ghostee group believed more adults had been ghosted a higher number of times than the Neither group (p = .007). No other comparisons were statistically significant (see OSF table supplement for exact p-values).

Figure 1. Participants’ Societal- and Personal-Level Descriptive Norms Based on Ghosting Experience.

Note. Error bars denote standard error. % = Percentage; # = Number.

Associations With Personal-Level Norms

An exploratory MANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed differences in participants’ personal-level descriptive norms based on their prior experience with ghosting, Wilk’s λ = .63, F(15, 2335) = 28.46, p < .001, ηp2 = .14. Specifically, differences were demonstrated across all norms: proportion who ghosted, F(3, 850) = 133.55, p < .001, ηp2 = .32, proportion willing to ghost, F(3, 850) = 98.16, p < .001, ηp2 = .26, times ghosted, F(3, 850) = 10.21, p < .001, ηp2 = .04, proportion who had been ghosted, F(3, 850) = 99.99, p < .001, ηp2 = .26, and times had been ghosted, F(3, 850) = 11.41, p < .001, ηp2 = .04 (see Figure 1). For all personal-level norms (i.e., friends), the Both group held higher descriptive norms than the Neither group (p’s ≤ .001). Additionally, the Both group believed a larger proportion of their friends had ghosted, were willing to ghost, and had been ghosted than the Only Ghoster and Only Ghostee groups (p’s ≤ .018). The Only Ghoster and Only Ghostee groups also believed that a larger proportion of their friends had ghosted, were willing to ghost, and had been ghosted than the Neither group (p’s ≤ .001). The Only Ghoster believed a larger proportion of their friends were willing to ghost than the Only Ghostee group (p = .002). Finally, the Only Ghostee group believed their friends had ghosted and been ghosted more times than the Neither group (p’s ≤ .032). No other comparisons were statistically significant (see OSF table supplement for exact p-values).

Injunctive Norms

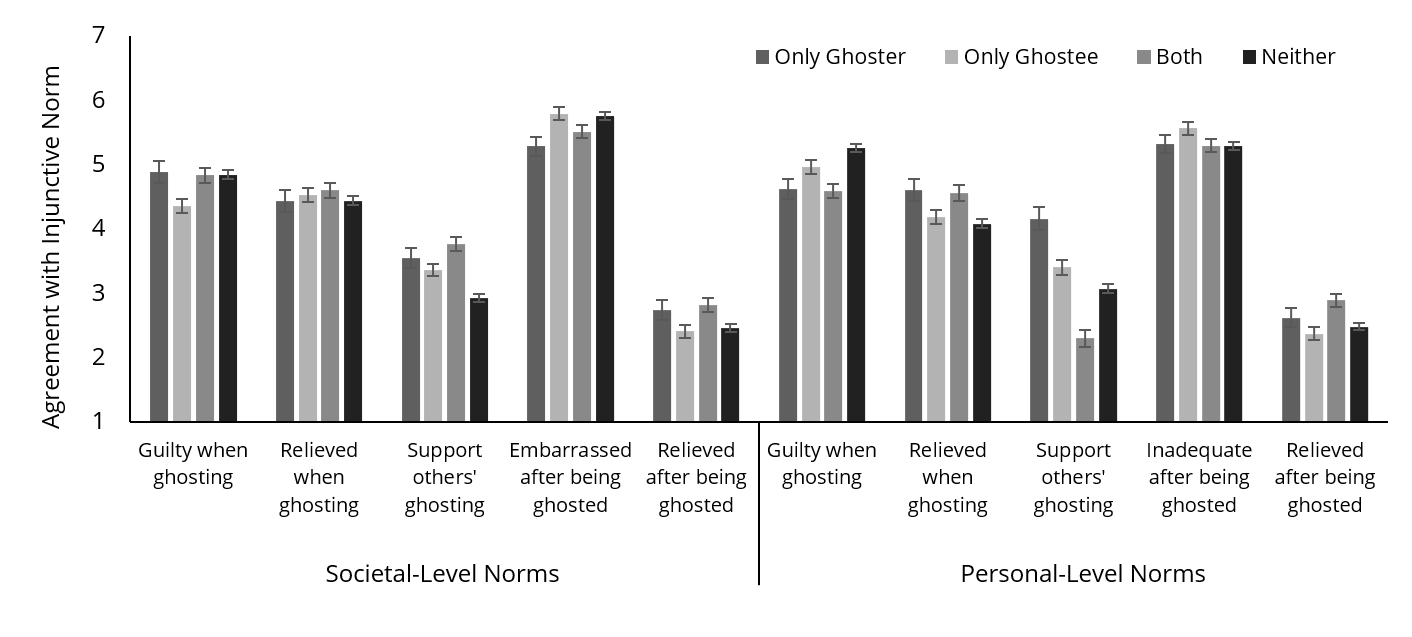

Associations With Societal-Level Norms

A pre-registered MANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analyses was conducted to examine the pre-registered hypotheses that H1: ghosters will think that others (personal-level and societal-level) feel more positively about ghosting than those who have neither ghosted nor been ghosted and H2: that ghostees will think that others (personal-level and societal-level) feel less positively about ghosting than those who have neither ghosted nor been ghosted. The MANOVA revealed differences in participants’ societal-level injunctive norms based on their prior experience with ghosting, Wilk’s λ = .90, F(15, 2350) = 5.86, p < .001, ηp2 = .03. Specifically, differences were demonstrated across the following norms: guilty when ghosting, F(3, 855) = 5.36, p = .001, ηp2 = .02, supportive of ghosting, F(3, 855) = 18.11, p < .001, ηp2 = .06, embarrassed/inadequate after being ghosted, F(3, 855) = 4.27, p = .005, ηp2 = .02, and relieved after being ghosted, F(3, 855) = 4.12, p = .007, ηp2 = .01; no difference was found for relief when ghosting, F(3, 855) = .54, p = .659, ηp2 = .00 (see Figure 2). The Only Ghostee group less strongly endorsed that adults feel guilty when ghosting than the other three groups (p’s ≤ .044). The Only Ghostee, Only Ghosted, and Both groups more strongly endorsed that adults support others’ ghosting than the Neither group (p’s ≤ .002); the Only Ghostee group also endorsed it less strongly than the Both group (p = .035). The Only Ghostee and Neither groups more strongly endorsed that adults feel embarrassed/inadequate after being ghosted than the Only Ghoster group (p’s ≤ .027). Lastly, the Only Ghostee and Neither groups less strongly endorsed that adults feel relieved after being ghosted than the Both group (p ≤ .031). No other comparisons were statistically significant (see OSF table supplement for exact p-values).

The pre-registered hypothesis that ghosters will think that others, at the societal-level, feel more positively about ghosting than those who have neither ghosted nor been ghosted was partially supported. Specifically, individuals who had only ghosted a romantic partner believed that adults were more supportive of others’ ghosting and that adults who had been ghosted were less likely to feel embarrassed/inadequate after being ghosted. The pre-registered hypothesis that ghostees will think that others, at the societal-level, feel less positively about ghosting than those who have neither ghosted nor been ghosted was not supported. On the contrary, individuals who had only been ghosted by a romantic partner believed that adults felt less guilty when ghosting and were more supportive of others’ ghosting than those with no prior experience with ghosting.

Associations With Personal-Level Norms

A pre-registered MANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analyses was conducted to examine the pre-registered hypotheses that H1: ghosters will think that others (personal-level and societal-level) feel more positively about ghosting than those who have neither ghosted nor been ghosted and H2: that ghostees will think that others (personal-level and societal-level) feel less positively about ghosting than those who have neither ghosted nor been ghosted. The MANOVA revealed differences in participants’ personal-level injunctive norms based on their prior experience with ghosting, Wilk’s λ = .90, F(15, 2339) = 7.43, p < .001, ηp2 = .04. Specifically, differences were demonstrated across the following norms: guilty when ghosting, F(3, 851) = 11.58, p < .001, ηp2 = .04, relief when ghosting, F(3, 851) = 6.02, p < .001, ηp2 = .02, supportive of ghosting, F(3, 851) = 29.67, p < .001, ηp2 = .10, and relieved after being ghosting, F(3, 851) = 5.41, p = .001, ηp2 = .02; no difference was found for embarrassed/inadequate after being ghosted, F(3, 851) = 2.15, p = .093, ηp2 = .01 (see Figure 2). The Neither group more strongly endorsed that their friends feel guilty when ghosting than the Only Ghoster and Both groups (p’s ≤ .001). The Neither group less strongly endorsed that their friends feel relief when ghosting than the Only Ghoster and Both groups (p’s ≤ .025). The Neither and Only Ghostee groups less strongly endorsed that their friends support others’ ghosting than the Only Ghoster and Both groups (p’s ≤ .003). Lastly, the Neither and Only Ghostee groups less strongly endorsed that their friends feel relieved after being ghosted than the Both group (p’s ≤ .003). No other comparisons were statistically significant (see OSF table supplement for exact p-values).1

The pre-registered hypothesis that ghosters will think that others, at the personal-level, feel more positively about ghosting than those who have neither ghosted nor been ghosted was largely supported. Specifically, individuals who had only ghosted believed that their friends feel less guilty when ghosting, more relief when ghosting, and were more supportive of others’ ghosting than those with no prior experience with ghosting. Furthermore, individuals who had both ghosted and been ghosted believed that their friends feel similarly across those injunctive norms, and that their friends feel more relieved after being ghosted than those with no prior experience with ghosting. The pre-registered hypothesis that ghostees will think that others, at the personal-level, feel less positively about ghosting than those who have neither ghosted nor been ghosted was largely not supported. Rather, individuals who had only been ghosted were not significantly different in their person-level injunctive norms from individuals who had no prior experience with ghosting.

Figure 2. Participants’ Societal- and Personal-Level Injunctive Norms Based on Ghosting Experience.

Note. Error bars denote standard error.

Discussion

These analyses demonstrate the first step in understanding the descriptive and injunctive norms individuals possess about ghosting. Specifically, we examined whether descriptive norms at the societal-level (e.g., adults, in general) and at the personal-level (i.e., friends) for ghosting a romantic partner and for being ghosted by a romantic partner differed based on participants’ prior experience with ghosting. Given that norms can influence intentions to engage in specific behaviors as well as influence how individuals evaluate their own behaviors, understanding the norms individuals possess about ghosting extends our understanding regarding the perceived acceptability of ghosting and the reasons why some individuals choose to ghost a romantic partner rather than use a different relationship dissolution strategy.

Similar to other research, a majority of our participants had heard of ghosting but varied in their direct experience with ghosting. It may be that most adults are aware of the concept of ghosting because of the attention it has received in the popular press (e.g., Borgueta, 2016; Engle, 2019) and in television shows (e.g., MTV’s Ghosted: Love Gone Missing). Further, it may be that fewer of our participants had first-hand experiences with ghosting than some other studies (e.g., Koessler et al., 2019a; LeFebvre et al., 2019; Navarro et al., 2020) because we did not restrict the age range of our sample.

The analyses demonstrated individual differences in perceived norms of ghosting based on participants’ prior experience with ghosting. Specifically, those with any prior experience with ghosting, and especially those who had both ghosted and been ghosted, believed ghosting to be more common among adults, in general, and among their friends. Those without prior ghosting experience were less likely to believe that ghosting is common among adults, in general, or among their friends. These results are in line with research on assumed similarity and the false consensus effect (Cronbach, 1955; Gilovich, 1990; Ross et al., 1976). Further, Kenny (1994) asserted that assumed similarity is stronger the closer the individuals are (i.e., friends versus adults, in general), and the pattern of descriptive norm results demonstrate more nuance based on ghosting experience at the personal-level than at the societal-level. Additionally, the false consensus effect is strongest when presented with more general or vague information (Gilovich, 1990). As such, the difference in descriptive norms based on prior experience with ghosting may have been even larger had participants not been provided with an explicit description of what ghosting meant before answering questions about their perceived norms for ghosting.

Individuals’ prior experiences with ghosting were also associated with how they believed others felt about ghosting. However, while there were significant differences based on ghosting experience, the pattern of results for endorsing each injunctive norm was more similar between societal- and personal-level norms than they were for descriptive norms. For example, regardless of prior experience with ghosting, participants tended to agree that adults, in general, as well as their friends, did not feel relieved but, rather, felt embarrassed/inadequate after being ghosted. As such, there may be a perceived consensus (Hoch, 1987; Zou et al., 2009) among individuals regarding the emotional ramifications of ghosting, regardless of prior experience with ghosting.

Implications

Although frequently thought of as an “easier” method of relationship dissolution (DeWiele & Campbell, 2019; LeFebvre et al., 2019; Manning et al., 2019; Thomas & Dubar, 2021; Timmermans et al., 2020), ghosting can have negative impacts (Koessler et al., 2019a; LeFebvre & Fan, 2020; LeFebvre et al., 2020; Pancani et al., 2021). As such, it may be beneficial to seek ways to reduce rates of ghosting. One such way to do so may be to correct individuals’ perceived norms about ghosting in a place where ghosting commonly (but not solely) occurs—dating apps (DeWiele & Campbell, 2019; Thomas & Dubar, 2021; Timmermans et al., 2020).

As alluded to previously, at least one dating app has employed a system designed to reduce rates of ghosting on their app when messages have gone unanswered after a specific period of time (Horton, 2018). Dating app developers might employ a similar system when users are choosing to “unmatch” or block a prospective partner, or when choosing to delete their app, so that individuals with whom they were recently communicating are not simply ghosted. Guided by prior research (Tom Tong & Walther, 2010), users could be encouraged to do so using a pre-written message or by tailoring their own messaging. Within the system to encourage users to send a closing message could be an acknowledgement of their own experiences with ghosting compared to norms of ghosting. Specifically, the system could acknowledge the user’s own prior experiences of ghosting or being ghosted by others on the dating app. Semi-individualized messages acknowledging their own prior experiences would be important because of wide variability in descriptive norms and the demonstrated differences in norms based on prior ghosting experiences noted in this study. As such, a singular message about perceived rates of ghosting may influence behavior in unintended directions (Goldstein & Cialdini, 2007).

Prior attempts to modify or correct perceived norms have not always shifted behavior in the ways intended (e.g., Campo & Cameron, 2006; Keeling, 2000; Schultz et al., 2007). Supporting deviance regulation theory (see Goldstein & Cialdini, 2007), our results reiterate the importance of understanding the individuals’ own experiences, and subsequently their perceptions of what is normative, before attempting to modify their behavior with specific messaging. Focusing on injunctive norms, for example, if the user believes not ghosting a romantic partner is normative, then incorporating the message, Those who ghost a romantic partner are (insert negative adjective: inconsiderate, selfish, etc.) may reduce the likelihood of them ghosting prospective romantic partners. On the other hand, if the user believes ghosting a romantic partner is normative, then incorporating the message, Those who do not ghost a romantic partner are (insert a positive adjective: considerate, selfless, etc.) may reduce the likelihood of them ghosting prospective romantic partners.

Furthermore, and supporting social identity and self-categorization theories (see Goldstein & Cialdini, 2007), in the present study, participants’ prior experience with ghosting was a better predictor of norms, especially descriptive norms, at the personal-level than at the societal-level. Thus, guided by social identity and self-categorization theories, dating apps might suggest messaging to modify or correct perceived norms of ghosting such as, Your friends don’t typically ghost their prospective partners, you shouldn’t either, rather than Other users don’t typically ghost their romantic partners, you shouldn’t either.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study benefits from having been pre-registered, but many of the analyses in this manuscript were exploratory. Additional work should be conducted to replicate these results. Further, for the half of the sample with prior ghosting experience, the study did not ask their total number of experiences as an initiator or recipient of ghosting, nor did it ask how long it had been since participants’ most recent ghosting experience. For example, one-third of the sample was in a long-term/committed relationship and unlikely to have had a recent ghosting experience. It may be that individuals’ cumulative number of ghosting experiences and/or the recency of their ghosting experience impacts their perceived norms. Additionally, participants were not asked about their prior experience with online dating technologies (e.g., dating websites, dating apps). Such information could be informative and associated with participants’ norms, given that usage of dating technologies has been linked with higher rates and expectations of ghosting (De Wiele & Campbell, 2019; Thomas & Dubar, 2021).

Other individual differences may also impact perceptions of ghosting norms. For example, research on relationship-related behaviors and perceived norms have noted differences based on gender (e.g., Auster et al., 2018; De Meyer et al., 2017; Hanson, 2021a), sexual orientation (e.g., Klinkenberg & Rose, 1994; Potârca et al., 2015), social status (e.g., Armstrong et al., 2014), and the intersectionality of factors (e.g., Kuperberg & Padgett, 2015). Focused on ghosting within dating apps, the design of specific dating apps may also impact individuals’ perceptions of ghosting norms. For example, other research has demonstrated differences in users’ actual and expected behaviors across specific dating apps (e.g., which genders initiate conversations, potential anonymity of users; Bryon & Albury, 2018; Comunello et al., 2021; Pruchniewska, 2020).

Moreover, to date, all ghosting research has been cross-sectional. It would be interesting for scholars to explore whether, and if so how, participants’ perceived norms of ghosting may change over time. Lastly, it could be beneficial to begin examining the utility of specific messaging in an effort to decrease ghosting.

Conclusion

This study provides a detailed glimpse into individuals’ descriptive and injunctive norms of ghosting in romantic relationships. Although norms may not be a fully accurate reflection of others’ behaviors (Rimal & Real, 2003), they have been demonstrated to influence behavioral intentions (Goldstein & Cialdini, 2007). Our research shows that, despite the negative emotions individuals believe to be normative of ghosting, individuals who believe that ghosting is normative also indicate that they are more likely to have ghosted and/or been ghosted. This study suggests that individuals tend to think their friends have had fewer experiences with romantic ghosting (as an initiator or as a recipient) than adults more broadly in society have had, and those who have both ghosted and been ghosted possess the highest descriptive norms (i.e., believe it to be more common) than those with only one-sided or no prior experiences with ghosting. This study also suggests that individuals tend to believe both their friends and adults feel guilty when ghosting romantic partners and that both groups of individuals feel embarrassed or inadequate when they are ghosted by a romantic partner. Further, these results suggest that a key consideration when attempting to modify individuals’ perceptions of norms of ghosting, especially their descriptive norms, is to identify the individual’s prior experience with ghosting and then phrase messaging at the personal-level (i.e., what their friends may or may not do).

Footnotes

1 The four MANOVAs were also conducted controlling for participants’ marital status (i.e., single, dating, or married/long-term committed relationship) and the results were consistent with what is reported in the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2022 Darcey N. Powell, Gili Freedman, Benjamin Le, and Kipling D. Williams.