Disinformation in Poland: Thematic classification based on content analysis of fake news from 2019

Vol.15,No.4(2021)

The paper presents a qualitative study of fake news on Polish-language internet media that seeks to arrive at their thematic classification in order to identify areas particularly vulnerable to disinformation in Poland. Fake news examples from 2019 were selected using popular Polish fact-checking sites (N = 192) and subjected to textual analysis and coding procedure to establish the thematic categories and specific topics most often encountered in this type of disinformation, with the following thematic categories identified in the process: political and economic; social; gossip/rumour; extreme; pseudo-scientific; worldview; historical; and commercial. The study culminates in a critical interpretation of results and discussion of the phenomenon in its Polish and international contexts. Among discussed conclusions is the dominance of content related to the government, Catholic Church, and LGBT issues in the Polish context, as well as the longevity of health-based fake news, especially anti-vaccination content, that points to the global impact of fake news and calls for action to prevent its spread.

content analysis; disinformation; fact-checking; misinformation

Klaudia A. Rosińska

Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University, Warsaw, Poland

Klaudia A. Rosińska is a media scholar and educator specializing in fake news and disinformation with a doctorate in media and theology. Her most recent publication is a book on "Fake news. Genesis, significance, counteraction" (PWN, 2021). She is also an author of articles on individual susceptibility to fake news and disinformation in Poland and a participant in international conferences in the area of cybersecurity. She spent 2019 at the University of Toronto as a recipient of the Joanna DeMone Visiting Graduate Student Scholarship. Currently works at the Academy of Social and Media Culture in Toruń.

Aldwairi, M., & Alwahedi A. (2018). Detecting fake news in social media networks. Procedia Computer Science, 141, 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.171

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Bastos, M. T., & Mercea, D. (2019). The Brexit botnet and user-generated hyperpartisan news. Social Science Computer Review, 37(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317734157

Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317

Brennen, J. S., Simon, F., Howard, P. N., & Kleis Nielsen, R. (2020, April 7). Types, sources, and claims of COVID-19 misinformation. Reuters Institute. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/types-sources-and-claims-covid-19-misinformation

Ceron, W., de-Lima-Santos, M-F., & Quiles, M. G. (2021). Fake news agenda in the era of COVID-19: Identifying trends through fact-checking content. Online Social Networks and Media, 21, Article 100116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.osnem.2020.100116

Chan, M. S., Jones, C. R., Hall Jamieson, K., & Albarracín, D. (2017). Debunking: A meta-analysis of the psychological efficacy of messages countering misinformation. Psychological Science, 28(11), 1531–1546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617714579

Cinelli, M., Quattrociocchi, W., Galeazzi, A., Valensise, C. M., Brugnoli, E., Schmidt, A. L., Zola, P., Zollo, F., & Scala, A. (2020). The covid-19 social media infodemic. Scientific Reports, 10, Article 16598. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

Conroy, N. K., Rubin V. L., & Chen Y. (2015). Automatic deception detection: Methods for finding fake news. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 52(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2015.145052010082

Davies, N. (2014). Serce Europy [Heart of Europe]. Wydawnictwo Znak Horyzont.

Devitt, A. & Ahmad K. (2007). Sentiment polarity identification in financial news: A cohesion-based approach. In A. Zaenen & A. van den Bosch (Eds.), Proceedings of the 45th Annual Meeting of the Association of Computational Linguistics (pp. 984–991). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/P07-1124

Domagała, B. (2018). Polak-katolik w oglądzie socjologicznym (Analiza wyników badań i wybranych problemów debaty publicznej) [Pole-Catholic in Sociological View (Analysis Results of Sociological Researchs and Selected Options of Public Debate)]. Humanistyka i Przyrodoznawstwo, 24, 267–280. https://doi.org/10.31648/hip.2620

Escolà-Gascón, Á., Marín, F.-X., Rusiñol, J., & Gallifa, J. (2021). Evidence of the psychological effects of pseudoscientific information about COVID-19 on rural and urban populations. Psychiatry Research, 295, Article 113628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113628

European Commission. (2018). A multi-dimensional approach to disinformation: Report of the independent high level group on fake news and online disinformation. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/6ef4df8b-4cea-11e8-be1d-01aa75ed71a1

EUvsDisinfo. (2019, July 26). Tinder will warn its users that Poland is a country dangerous for LGBT community. https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/tinder-will-warn-its-users-that-poland-is-a-country-dangerous-for-lgbt/

Evelyn, K. (2021, January 8). Capitol attack: The five people who died. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/jan/08/capitol-attack-police-officer-five-deaths?fbclid=IwAR2I31gwJ7ThLmSCcKj-VCpCFQOItug8GmPYOcyKIiE-BYbm2P6Zy6Vv8UQ

García-Marín, D. (2020). Infodemia global. Desórdenes informativos, narrativas fake y fact-checking en la crisis de la Covid-19 [Global infodemic. Information disorders, fake narratives and fact-checking in the Covid-19 crisis]. Profesional de la Información, 29(4), Article e290411. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.jul.11

Golbeck, J. A., Mauriello, M. L., Auxier, B., Bhanushali, K. H., Bonk, C., Bouzaghrane, M. A., Buntain, C., Chanduka, R., Cheakalos, P., Everett, J. B., Falak, W., Gieringer, C., Graney, J., Hoffman, K. M., Huth, L., Ma, Z., Jha, M., Khan, M., Kori, V., ... Visnansky, G. (2018). Fake news vs satire: A dataset and analysis. In WebSci '18: Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Web Science (pp. 17–21). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3201064.3201100

Golicyn A. (2007). Nowe kłamstwa w miejsce starych komunistyczna strategia podstępu i dezinformacji [New lies to replace the old communist strategy of deception and disinformation]. Wydawnictwo Biblioteka Służby Kontrwywiadu Wojskowego.

Gorwa, R. (2017). Computational propaganda in Poland: False amplifiers and the digital public sphere. In P. Howard & S. Woolley (Eds.), Computational Propaganda Research Project (pp. 1–32). University of Oxford.

Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B., & Lazer, D. (2019). Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science, 363(6425), 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau2706

Hänska-Ahy, M., & Bauchowitz, S. (2017). Tweeting for Brexit: How social media influenced the referendum. In J. Mair, T. Clark, N. Fowler, R. Snoddy, & R. Tait (Eds.), Brexit, Trump and the media (pp. 31–35). Abramis Academic Publishing.

Heine, S. J., Proulx, T., & Vohs, K. D. (2006). The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 88–110. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_1

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Horne, B. D., & Adalı, S. (2017, May). This just in: Fake news packs a lot in title, uses simpler, repetitive content in text body, more similar to satire than real news. In Eleventh International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (pp. 759–766). AAAI Publications.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Ireton, C., & Posetti, J. (2018). Journalism, fake news & disinformation: Handbook for journalism education and training. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265552

Izak, K. (2015). Nie tylko islam. Ekstremizm i terroryzm religijny [Not only Islam. Religious extremism and terrorism]. Przegląd Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego, 12(7), 183–210.

Kaur, H., & Thomas, N. (2020). 'Fake news' about a covid-19 vaccine has become a second pandemic, Red Cross chief says. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/12/01/media/red-cross-chief-warns-vaccine-mistrust-trnd/index.html

Lim, C. (2018). Checking how fact-checkers check. Research & Politics, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018786848

Meyer, R. (2018, March 8). The grim conclusions of the largest-ever study of fake news. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/03/largest-study-ever-fake-news-mit-twitter/555104/

Mikulska-Jolles, A. (2020). Fake newsy i dezinformacja w kampaniach wyborczych w Polsce w 2019 roku - raport z obserwacji [Fake news and disinformation in election campaigns in Poland in 2019 - observation report]. Helsińska Fundacja Praw Człowieka. https://www.hfhr.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Fake-newsy-i-dezinformacja_final.pdf

Ministerstwo Spraw Wewnętrznych i Administracji. (2020, October 28). Oświadczenie Ministra Spraw Wewnętrznych i Administracji ws. ataków na kościoły [Statement by the Minister of the Interior and Administration on attacks on churches]. https://www.gov.pl/web/mswia/oswiadczenie-ministra-spraw-wewnetrznych-i-administracji-ws-atakow-na-koscioly

Narayanan, V., Barash, V., Kelly, J., Kollanyi, B., Neudert, L.-M., & Howard, P. N. (2018). Polarization, partisanship and junk news consumption over social media in the US. Project on Computational Propaganda. http://comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/93/2018/02/2018-1.pdf

Olteanu, A., Castillo, C., Diaz, F., & Kıcıman, E. (2019). Social data: Biases, methodological pitfalls, and ethical boundaries. Frontiers in Big Data, 2, Article 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2019.00013

Pennycook, G., Cannon, T. D., & Rand, D. G. (2018). Prior exposure increases perceived accuracy of fake news. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(12), 1865–1880. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000465

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2019). Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition, 188, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.011

Piontek, D., & Annusewicz, O. (2013). Polityka popularna: Celebrytyzacja polityki, politainment, tabloidyzacja [Popular Politics: Celebritization of Politics, Politainment, Tabloidization]. Kwartalnik Naukowy OAP UW "e-Politikon", 5, 6–28.

Potthast, M., Kiesel, J., Reinartz, K., Bevendor, J., & Stein, B. (2018). A stylometric inquiry into hyperpartisan and fake news. In I. Gurevych & Y. Miyao (Eds.), Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (pp. 231–240). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P18-1022

Prier, J. (2017). Commanding the trend: Social media as information warfare. Strategic Studies Quarterly, 11(4), 50–85. https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/SSQ/documents/Volume-11_Issue-4/Prier.pdf

Ratzinger, J. (2005). Prawda, wiara, tolerancja. Chrześcijaństwo a religie świata [Truth And Tolerance: Christian Belief And World Religions]. Wydawnictwo Jedność.

Rose, J. (2017). Brexit, Trump, and post-truth politics. Public Integrity, 19(6), 555–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2017.1285540

Rubin, V. L., Conroy, N., Chen, Y., & Cornwell, S. (2016). Fake news or truth? Using satirical cues to detect potentially misleading news. In T. Fornaciari, E. Fitzpatrick & J. Bachenko (Eds.), Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Computational Approaches to Deception Detection (pp. 7–17). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/W16-0802

Salaverría, R., Buslón, N., López-Pan, F., León, B., López-Goñi, I., Erviti, M.-C. (2020). Desinformación en tiempos de pandemia: tipología de los bulos sobre la Covid-19 [Disinformation in times of pandemic: typology of hoaxes about Covid-19]. El Profesional de la Información, 29(3), Article e290315. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.15

Shahi, G. K., & Nandini, D. (2020). FakeCovid - A multilingual cross-domain fact check news dataset for COVID-19. In Workshop Proceedings of the 14th International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (pp. 1–9). AAAI. https://doi.org/10.36190/2020.14

Shu, K., Sliva, A., Wang, S., Tang, J., & Liu, H. (2017). Fake news detection on social media: A data mining perspective. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter, 19(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1145/3137597.3137600

Silverman, C., & Singer-Vine, J. (2016, December 6). Most Americans who see fake news believe it, new survey says. Buzzfeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/fake-news-survey

Świerczek, M. (2018). „System matrioszek”, czyli dezinformacja doskonała. Wstęp do zagadnienia [The “Matryoshka System”, or the perfect disinformation. Introduction to the topic]. Przegląd Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego, 10(19), 210–228.

Tambini, D. (2017). Fake news: Public policy responses (Media Policy Project). London School of Economics and Political Science. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/73015/1/LSE%20MPP%20Policy%20Brief%2020%20-%20Fake%20news_final.pdf

Tandoc, E. C., Jr. (2019). The facts of fake news: A research review. Sociology Compass, 13(9), Article e12724. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12724

Tandoc, E. C., Jr., Thomas, R. J., & Bishop, L. (2021). What is (fake) news? Analyzing news values (and more) in fake stories. Media and Communication, 9(1), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i1.3331

Vargo, C. J., Guo, L., & Amazeen, M. A. (2018). The agenda-setting power of fake news: A big data analysis of the online media landscape from 2014 to 2016. New Media & Society, 20(5), 2028–2049. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817712086

Vo, N., & Lee, K. (2018). The rise of guardians: Fact-checking URL recommendation to combat fake news. In SIGIR '18: The 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval (pp. 275–284). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3209978.3210037

Wachowicz, M. J. (2019). Ujęcie teoretyczne pojęcia dezinformacji [Theoretical concept of disinformation]. Wiedza Obronna, 1(2), 226–253. https://doi.org/10.34752/x40y-nc78

Wardle, C. (2017). Fake news. It’s complicated. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.com/fake-newscomplicated/30

Zhang, X., Ghorbani, A. A. (2020). An overview of online fake news: Characterization, detection, and discussion. Information Processing & Management, 57(2), Article 102025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2019.03.004

Zimdars, M. (2016, April 30). False, misleading, clickbait-y, and satirical “news” sources. Cusd80. https://www.cusd80.com/cms/lib/AZ01001175/Centricity/Domain/8219/Fake%20News%20Resource.pdf

Editorial Record

First submission received:

February 9, 2021

Revisions received:

July 2, 2021

October 4, 2021

Accepted for publication:

October 7, 2021

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

In today’s reality, disinformation has become a global problem and an increasingly common tool of information warfare (Bennett & Livingston, 2018; Prier, 2017). Fake news constitutes one element of disinformation and can exert enormous influence on significant social decisions, as exemplified by the 2016 US presidential election, or by Brexit in the UK (Bastos & Mercea, 2019; Hänska-Ahy & Bauchowitz, 2017; Rose, 2017). In response, various institutions and organizations are working to identify ways of countering the fake news phenomenon (European Commission Report, 2018; Ireton & Posetti, 2018). Since disinformation via fake news feeds on sensitive areas of public discourse of particular countries to give rise to strong social emotions (Golbeck et al., 2018), global solutions to the problem can suffer from a shortfall of local contexts. This study aims to address this situation.

After a year of the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, the phenomenon of disinformation via fake news has become more real than ever before. Some researchers have already begun to speak of “infodemia” (Cinelli et al., 2020) having equally tragic consequences as the virus. Pseudoscientific information about the effects of the virus and its potential remedies can clearly impact people’s health decisions. Even more worrisome is false information about SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, which Francesco Rocca, the current IFRC president, calls “a second pandemic” (Kaur & Thomas, 2020). With many people resisting vaccination due to false information, the resurgence of pseudoscientific and health-oriented fake news during this pandemic calls for immediate measures to combat the growth of their influence. Much false information, moreover, continues to emerge around political and social issues and points to the ever-more serious levels of disinformation affecting current international relations.

There is sufficient evidence by now to indicate that fake news based in social conflicts of a given country and circulating within its media can seep into the media space of other countries, becoming a tool of inciting and strengthening of both internal and international conflicts. This effect is called strategic disinformation, a term that dates to the Soviet Union (Wachowicz, 2019). In the Russian formulation, strategic disinformation means systematic efforts aimed at spreading fake news and at falsifying or blocking information about the real situation and politics of the communist world (Golicyn, 2007). Practices of disinformation aim to confuse, lead astray, and exert a biased influence on the non-communist world, to undermine its politics and lead its Western opponents to unwittingly contribute to the realization of communist aims (Świerczek, 2018). To realize these aims, existing divisions, doubts, or group-based conflicts in Western societies must be identified and reinforced by means of disinformation and propaganda that produces a new, false narration in the process. Developing means of mass communication only simplified this task, with mass produced and distributed fake news constituting an almost impossible to trace tool of influence and destabilization. For this tool to be effective, however, it is key to identify the areas conducive to conflict in each individual country and to produce fake news that stirs up the social emotions prevailing there.

Identifying the specific subjects and themes that are especially prone to fake news in particular countries can also serve to forewarn the international community of the vulnerability of these areas to disinformation. This study thus aims to identify some of the key points on the thematic map of fake news in Polish internet media, meaning areas particularly vulnerable to disinformation. Before proceeding, however, it is necessary to first define the phenomenon and consider its existing scholarly classifications.

Defining and Classifying the Phenomenon

There is no single and unambiguous definition of fake news: literature on the subject offers various perspectives on the phenomenon and emphasizes its different aspects, pointing to its complexity and broad impact. From the perspective of media studies, existing definitions can be divided in line with their narrow or broad view of the issue. In the narrow perspective, fake news is defined as media messages that are presented as real news despite not being based on facts. Of particular importance in the context of disinformation is the intentionality of its production and distribution among an unaware audience, with fake news in the narrow perspective being created to deceive the audience (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017; Conroy et al., 2015; Potthast et al., 2018; Vargo et al., 2018). In the narrow view, the most popular type of fake news has been identified with political and economic content (Aldwairi & Alwahedi, 2018; Horne & Adalı, 2017; Meyer, 2018; Silverman & Singer-Vine, 2016). While some fake news is produced intentionally for disinformation purposes, however, others become ‘fake’, so to speak, in the process of reception. This kind of fake news can also be harmful, since it distracts the attention of internet users and contributes to an informational overload. A broader view at fake news thus focuses not on the intention of the producer but rather the falsity of the content and its distribution. Broad definitions include in their classification satirical and mocking news, as well as all kinds of fabrications, provocations, and mystifications, along with journalistic errors. From a broad perspective, fake news is a product of both intentional disinformation and unintentional misinformation (Gorwa, 2017; Rubin et al., 2016).

For the purpose of this article, a definition that combines both the narrow and broad perspectives of fake news was established to provide a framework for the forthcoming analysis. Accordingly, fake news is any false communication presented in the media as news without actually being real, and it can be created intentionally, or become fake news in the process of distribution via social media, beyond its original author’s reach. With this definition in mind, it is worthwhile to consider the most important of its existing classifications to better understand the specificity and functioning of fake news. Such reflection can illuminate the real dangers of fake news on the internet and the areas of life that it can impact, and in the process help to establish the thematic categories in need of further analysis.

The various classifications of fake news that have emerged so far often concentrate on the type of falsification that they use (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017; Conroy, et al., 2015; Tambini, 2017; Wardle, 2017; Zhang & Ghorbani, 2020). Some of them reference the means of manipulation used in fake news, while others the place of their publication, or their degree of falsity (Shu et al., 2017; Zimdars, 2016); taken together, they help to create an outline of areas of potential concern to this study. Looking at fake news as a tool of intentional disinformation produced to deceive its audience, as Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow (2017) have done, allows to distinguish two types: spectacular and fabricated. Fake news is classified as spectacular when based on religious beliefs and prejudices, while fabricated fake news refer to those produced for some political or financial advantage, as well as those that cause harm. This distinction already presents fake news as relating to specific areas of human life, whether politics, religion, or ideology. Other classifications reveal more such areas of relevance. Xichen Zhang and Ali A. Ghorbani (2020) add two more types of fake news to the existing classifications – fake reviews and fake commercials – thus factoring in consumption as an important aspect of human experience.

Classifications that take a broad view of view fake news include parody, journalistic errors, as well as a type of radical fake news that is ideologically-oriented and draws on an authority (Conroy, et al., 2015; Tambini, 2017). The last category in particular signals a new area of influence of fake news. With the use of contemporary authority figures from various fields of people’s lives (such as music, sports, and religious or social movements), it is now possible to convey a particular message to new audiences that are not necessarily directly interested in politics or economics. Such fake news influences its recipients indirectly, by engaging their passions and interests, which potentially makes them more dangerous. In addition, Melissa Zimdars’ analysis of fake news websites (2016) brings new categories to considerations of the phenomenon, with eleven types of unreliable web sites emerging from her research: (1) Fake news; (2) Satire; (3) Extreme Bias; (4) Conspiracy Theory; (5) Rumor Mill; (6) State News; (7) Junk Science; (8) Hate News; (9) Clickbait; (10) Proceed with Caution; (11) Political.

While a review of media studies literature shows fake news to be a diverse phenomenon composed of multiple aspects, the range of existing classifications is missing a comprehensive approach to the phenomenon in a thematic context. It is the mechanism of fake news that has often received critical attention. This is precisely why a detailed study of the subject areas that fake news has infiltrated thus far is necessary. Such work will enable the mapping of issues that are particularly prone to disinformation through fake news, aiding the development and deployment of preventive measures in those areas. The lack of qualitative analyses and thematic classifications of fake news, which could help to identify areas particularly vulnerable to and threatened by the occurrence of fake news (Conroy et al., 2015; Golbeck et al., 2018), constitutes a gap worth bridging.

The few recent studies on the thematics of fake news that analyzed articles from factchecking portals have already brought some interesting results. A study of fake news about COVID 19 conducted by Brennen et al. (2020) revealed that reconfigured content accounted for 59% of the analyzed sample, followed by fabricated content (38%) and satire, or parody (3%). A different study by Garcia-Marin (2020), which used an international fake news database made available by the IFCN, also indicates a shift in how fake news about COVID-19 are produced, showing an increase in content that is partially based on facts in comparison with that which is entirely made-up. Both sets of authors note that verifying fake news based on facts is considerably more difficult and time-consuming than exposing entirely fabricated information. Consequently, the impact of such fake news on its recipients can be more enduring. A team of Spanish researchers (Salaverría et al., 2020) conducted a more detailed thematic analysis of fake news in Spain between March 14 and April 14 of 2020, which reveals that, beside a large number of fake news about health (including those that question the science related to the COVID-19 pandemic), a lot of false political content had also gained in popularity. This indicates that some thematic areas are permanently vulnerable to disinformation, regardless of external factors such as the pandemic. Similarly, researchers in Brazil undertook an interesting study of tweets (Ceron et al., 2021) that points to certain groups of political and health topics as characteristic of infodemia as well as to how such false content spreads. Their research shows a relationship between subjects that are of political and social significance in Brazil and the increase of fake news in these areas, which is not necessarily due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This study also backs the hypothesis that some disinformation trends are ongoing and closely tied to politics, irrespective of changing external circumstances.

A retrospective analysis by Edson Tandoc and colleagues (2021), in turn, reveals that the largest part of the analyzed fake content from the years of 2017-2018 in the United Stated pertained to the government’s politics (51.6%), followed by crimes and terrorist acts (19.5%) and science, health, and technology (10.3%). Their research also shows that “newsness” of fake news is a significant factor that corresponds on a thematic level with a country’s media ecosystem and the real news that are published. This insight makes the value of thematic analysis of fake news within the context of a given country’s media culture more apparent. Such analysis can help to create a thematic map of areas that are particularly at risk of disinformation and enable predictions about the potential rise of fake news in these popular categories, similarly to how this happens in the case of real news. This, in turn, can contribute to making the means of countering disinformation more efficient, for example in advance and during periods of election campaigns.

With this in mind, the study poses two key research questions: (1) What are the thematic categories of fake news in Polish-language online media? and, (2) What specific topics are covered by fake news in the top five of the identified categories?

Method

The study’s methodology, which will be detailed shortly, involved the content analysis of a sample of 192 fake news instances from Polish-language online media published in 2019, a year of two electoral campaigns in Poland – to the European Parliament in May, and the Polish Parliament in October. Its aim was to arrive at a thematic classification of fake news and to identify their specificity in the context of Polish social and media realities. The content analysis of the entire fake news sample led to the identification of key words, which then served as a basis for defining the thematic areas referenced by each example of fake news. The same type of analysis was subsequently repeated to determine the type of manipulation used in each instance.

Content analysis is a broadly applied qualitative and quantitative research technique (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) that comprises three approaches: conventional, targeted or summarizing. For the purposes of this study, a targeted approach was employed to create the codes and categories, which relies on using existing literature in the field of study. Accordingly, preliminary analytic categories were determined based on past research, as sketched out above, before being subjected to a coding procedure.

Despite obvious limitations of content analysis, such as the sample size and accessibility of sources, a qualitative method was chosen for this study due largely to the complexity of the fake news phenomenon. The extensive range of stylistic tools used in a fake message continues to challenge machine data analytics and constitutes a problem for only quantitative approaches to the issue (Aldwairi & Alwahedi, 2018 Devitt & Ahmad, 2007). Another significant factor for choosing a quantitative approach is the social and media context of fake news, which makes it difficult to account for both the vast spectrum of information and communication technologies across the world and the range of individual access to them (Olteanu et al., 2019). In addition, qualitative analysis was deemed more suitable since it revealed the specific differences in techniques of manipulation deployed in fake news as well as the specificity of each fake news example in the Polish context.

Data Collection

The data collection procedure involved several steps, starting with the selection of three fact-checking Polish organizations engaged in detecting and verifying fake news for the purpose of data collection that work independently of each other. Notably, portals engaged in verifying information are currently one of the fundamental methods of counteracting fake news (Lim, 2018). Their value rests on the ongoing verification of news and identifying fake news in the process. The result of verification is equally important to its process, which fact-checking organizations detail on their portals. Their audience can thus learn about the methods of manipulation used in fake news along with means of verifying new information.

For the purpose of this study, the following portals were selected: Demagog.org – the first fact-checking organization in Poland (with 31 797 likes, 33 586 followers on Facebook and 11 600 on Twitter); Demaskator24 – a portal created by experienced journalists and reporters from the Polska Press group (with 342 likes, 356 followers on Facebook and 109 on Twitter) and Konkret24 – a portal owned by the TVN media group, Poland’s largest private television network (with 19 615 likes, 20 927 followers on Facebook and 12 700 on Twitter). The selected portals are very active in verifying false information in Polish-language online media and have considerable reach, particularly on social media. Importantly, their different financing sources serve to mitigate possible thematic bias of their information selection.

Specifically, while both Demaskator24 and Konkret24 are media organizations, they belong to different media companies. In the case of the first portal, its creator – the Polska Press group - is currently financed by a state-owned company “Orlen,” having previously been part of the German holding company Verlagsgruppe Passau. In its coverage of news, the group usually takes a moderately conservative point-of-view. The TVN media group behind the second portal, in turn, belongs to the U.S conglomerate Discovery Communications and tends to present a liberal worldview. In effect, the two organizations have different audiences, with their fact-checking likely reaching different groups, which is of significance also to analyzing the variety of fake news contents. Finally, the organization Demagog is not a media, but a public benefit organization, and thus the most financially independent of the three, receiving its funding from various sources and grants. It is also the only of the selected organizations affiliated with the International Fact Checking Network, which upholds international standards in the verification process and guarantees objectivity. Additionally, as of September 2019, Demagog has begun to work with Facebook on an on-going basis by joining its program for information verification: whenever Demagog assesses given content as false, Facebook displays it lower down in its News Feed, which effectively curtails its reach, decreasing the number of its recipients as well limiting its spread. Based on key differences between the three selected portals, it is reasonable to surmise that analyzing the different content published by them will bring reliable and credible information about the significant fake news that circulate within Polish social media.

The database of each organization was searched for all records containing the phrase “fake news” in 2019 (research commenced at the onset of 2020 to include the entire year in the search), with the content creation date as the only set limit. The decision to search only for “fake news”, as opposed to other terms for the phenomenon (such as disinformation or misinformation), stems from the specificity of the Polish language, which does not yet have a clear equivalent for these other terms, with fake news used to describe all false information on social media. This search yielded 37 texts containing the term on Demagog.org, 44 on Demaskator24, and 158 on Konkret24, and led to a database of 239 news pieces related to the issue of fake news. The considerable difference in the number of texts accessed through these portals is related to differences in their already mentioned financing, with Konkret24, Demaskator24 and Demagog.org. Each identified piece of news was then reviewed in line with the definition adopted in the study, with news that repeated across the three sites, statistical reports on fake news, as well as false statements of politicians (classified instead as political manipulation) all being eliminated at this stage. This preliminary analysis comprised fake news titles and headlines and resulted in a database of 192 examples of fake news, which then underwent a coding procedure.

Coding Themes and Procedure

This coding encompassed the contents of fake news, including their title, headline, and body of the text, with key words used in the title and accompanying images being the decisive factor in a given content’s thematic categorization. Determining the main subject of each fake news instance was prerequisite to identifying the thematic areas of concern for the phenomenon, which proposed, in turn, on basis of a literature review, with classification of websites producing fake news (Zimdars, 2016) proving particularly useful to the process.

Figure 1. Fake News About United Right Politicians.

Source: Facebook.com

An illustrative example of the process of thematic categorization is the fake news about politicians from the United Right, Poland’s ruling political alliance, supposedly holding up crosses in the European Parliament (Figure 1).

In this instance, key to the content’s categorization was a photo showing the politicians in question as well as its mocking title (in English: “A strong group of exorcists already in action!”). The photo is, in fact, a photomontage, with image editing software used to add the crosses to the image, and its aim is clearly to mock the featured politicians. Based on these two elements, the content’s theme was categorized as political and economic, rather than worldview based, since it targeted politicians rather than religion itself. Notably, this fake news has resurfaced in 2020, once again attracting recipients willing to believe it.

Critical textual analysis of every fake news instance in the database yielded by data collection served as a basis of a code book that aided the preliminary classification of key words related to fake news. The code book included two questions: (1) Which thematic category does a given fake news fall under? and (2) What manipulation techniques does a given fake news utilize? To facilitate the coding process, a glossary of terms typical of each category was also created. The thematic criterion initially comprised the following content categories: extreme; commercial; conspiratorial; gossip or rumor based; political and economic; disinformative or misleading; pseudo-scientific; satirical; sociohistorical; worldview or ideology based; and manipulative. The criterion of types of manipulation used in fake news, in turn, was composed of the following categories: intentional misleading; fabrication; false context; false association; quote manipulation; manipulation of authentic photos or videos; manipulation of authentic data; conspiracy theories; satire, joke, or irony; and intimidation. To aid decisions regarding qualification, the code book provided thorough descriptions of each category including examples and classifying instructions as well as a glossary of terms characteristic of the given type or topic. This constituted the foundation of the first round of coding.

Table 1. Thematic Categories of Fake News.

|

Thematic Category |

Description |

|

political and economic |

content about specific politicians in Poland and abroad, or legal, political, or economic actions |

|

social |

content about social events, activists, public benefit and minority organizations, as well as dangers and threats to human and animal health |

|

gossip/rumour |

content about celebrities, actors and public figures without a political or activist profile |

|

extreme |

content about drastic, catastrophic, or brutal events taking place in Poland or around the world |

|

pseudoscientific |

content that calls on supposedly scientific research or highly reputable institutions without identifying concrete sources or by manipulating them to create a false theory |

|

worldview |

content about religion, faith, and spiritual figures as well as various non-religious ideologies, views, and beliefs |

|

historical |

content about historical events or the distant past of public figures |

|

commercial |

content such as false product reviews and advertising campaigns or commercial click-bait aimed at accumulating views, ‘likes’ and comments (such as manipulated photos of animals) |

Two competent judges were asked to code 20 examples from the study’s fake news database to test the clarity of received instructions, with both receiving a complete code book along with individual training in coding. Based on their feedback, the code book instructions were then modified. In particular, the socio-historical category was split into two distinct themes: social and historical. The first category encompassed news from contemporary social life that show a false version of events or manipulate facts about a given subject (example from the database: “Nazi march during the Independence March”), and the latter referred to content about people and events of the past (example from the database: fake news that Lech Wałęsa did not collaborate with the PPR’s Security Services). Furthermore, categories initially labelled as disinformative or misleading, manipulative, satirical, and conspiratorial were eliminated since, on a thematic level, they were found to constitute sub-categories of the social, gossip/rumour, and political and economic themes, with the only difference being in desired effect. For this reason, a new code book was prepared for the second round of coding, which focussed only on the following thematic categories: political and economic; social; gossip/rumour; extreme; pseudo-scientific; worldview; historical; and commercial (Table 1).

The second and comprehensive round of coding involved both judges individually coding the 192 fake news examples in the database by theme and type, in line with the revised code book. To identify the themes and types of manipulation used in each instance, the coders read all of the posts, which were copied and pasted into the coding sheet, along with their descriptions on the attached fact-checking sites. As a final step, the results received from both judges, were analyzed for consistency using the Cohen’s kappa coefficient (1960), which was seen as most appropriate in accounting for the diversity of classifications and the probability of random consistency. The value of that coefficient was 0.86 for the thematic criterion, and 0.90 for the typological criterion, with both values indicative of a very good level of consistency.

Results

RQ 1: What are the thematic categories of fake news in Polish-language online media?

Table 2. Frequency of Fake News by Theme, Including Subcategories in top Five Areas (2019).

|

Themes and topics |

Number of texts |

Annual Frequency of Occurance (%) |

|

Political and economic |

68 |

35% |

|

Public figures |

41 |

|

|

International relations |

11 |

|

|

Environment |

9 |

|

|

Political parties |

5 |

|

|

Law |

2 |

|

|

Social |

50 |

26% |

|

LGBTQ |

15 |

|

|

World news |

12 |

|

|

Health and food |

8 |

|

|

Current affairs |

6 |

|

|

International relations |

5 |

|

|

Animals |

4 |

|

|

Worldview |

20 |

10% |

|

Religious beliefs |

10 |

|

|

International affairs |

9 |

|

|

Law |

1 |

|

|

Pseudo-scientific |

17 |

9% |

|

Health |

16 |

|

|

Global warming |

1 |

|

|

Extreme |

17 |

9% |

|

Child endangerment |

5 |

|

|

Tragic world news |

5 |

|

|

Acts of violence |

5 |

|

|

Natural disasters |

1 |

|

|

Abortion |

1 |

|

|

Gossip/Rumour |

12 |

6% |

|

Commercial |

6 |

3% |

|

Historical |

2 |

1% |

|

|

192 |

100% |

The conducted analysis enabled classification of fake news in Polish media from 2019 according to specified thematic categories, including the identification of key topics within the most popular areas (Table 2). Within the parameters of this study, political and economic content was definitely most popular, with this theme representing 35% of sampled fake news. Social themes were the second most popular category with 26% of the total, followed by the worldview/ideological thematic category (10%), with pseudoscientific and extreme themes (9% respectively) and gossip/rumour (6%) having only slightly lower percentage shares. The percentage points of the final two categories, in turn, were significantly smaller, at 3% for commercial and 1% for historical content. Looking at the most numerous categories identified by the study already points to a certain specificity of Polish media realities in which fake news presently function.

RQ 2: What are the specific topics covered by the top five of identified thematic categories?

The subcategories, or individual topics, of the most popular thematic areas emerged from the decisions of competent judges and the key words they identified to describe each sample.

Political and Economic Category

The most popular thematic category of political and economic content thus included five topics: public figures, international relations, environment, political parties, and law. The public figures subcategory included fake news about politicians, leaders, as well as heads of state, and among the analyzed examples was one titled “President Duda kneels before Jarosław Kaczyński” (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Fake News “President Duda Kneels Before Jarosław Kaczyński.”

Source: Facebook.com

This content appeared on the Facebook page “PiS na księżyc” (in English: Law & Justice to the moon”) and met with considerable interest among the Facebook users, attracting 5 400 shares, 339 comments, and over 2 100 reactions. The image shown is an alteration of the original photograph, which shows President Andrzej Duda kneeling at a 12th century Cistercian Abbey in Jędrzejów (the Polish president visited it during the previous electoral campaign, on August 10, 2015, as part of his tour of Polish districts). In the manipulated image, the figure of the Law & Justice Party leader, Jarosław Kaczyński, has been added in a way that makes it seem that President Duda is kneeling in front of him. The image builds on the quite popular belief in Poland that Jarosław Kaczyński is the country’s unofficial leader, and that its President is actually his subordinate. The falsification aimed to strengthen this belief and simultaneously weaken President Duda’s re-election campaign and chances. Jarosław Kaczyński was also the direct object of fake news, in which an image of someone else’s Security Service (SB) file from the PPR era was altered to show Kaczyński’s photo from his youth to implicate him as a secret Security Service collaborator. Another manipulated image of a politician, titled “Adam Andruszkiewicz with a swastika,” showed him wearing a shirt with the Nazi Germany symbol on it, where the symbol was actually superimposed on what was originally just a white shirt. A similar method was used to alter a photo of Bernadeta Krynicka, a Law & Justice member of Parliament; where the original shows her with a rifle beside a shooting range target, the manipulated photo replaces the image on the target with the International Symbol for Access, creating the impression that Krynicka is taking aim at the disabled. Each of these examples of image manipulations aims to mock or slander the featured political figure by linking it with socially unacceptable behaviors. Notably, altered photographs of politicians from Poland’s ruling party were the most frequent form of manipulation in this thematic subcategory, with most fake news about public figures (25 out of 41) taking aim at members of the United Right, which clearly points to their anti-government tendency. Of additional significance is the fact that examples concerning the ruling coalition were verified by all three of the fact-checking organizations selected for this study, which confirms the popularity of such fake news.

In comparison, only 7 politically-themed examples were about politicians unaffiliated with the United Right. These included manipulated statements supposedly made by the former Prime Minister Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz about Poland’s restitution of Jewish property during an interview; while he is clear in the interview that he considers such action to be impossible, the fake news presents his words as supportive of Poland paying compensation. Manipulation of context was likewise at play in two fake news examples about Poland’s former President Lech Wałęsa, as well as in one about the MP Paweł Kukiz and another about the euro-deputy Sylwia Spurek. Yet another example in this group concerned rumours of three senators from the Civic Platform, Poland’s main opposition party, supposedly joining the ruling Law and Justice party and thereby giving it a majority in the Senate, which turned out to be only gossip. In all these cases, their verification was undertaken only by portals Konkret24 and Demaskator24, but not by the independent Demagog. Some politically-themed content concerned foreign politicians, such as a fake video showing an intoxicated Nancy Pelosi that aimed at diminishing the democratic US Speaker of the House, or news about Donald Trump calling the Italian President “Mozzarella,” meant to tarnish the image of the now former President of the USA. Content about Angela Merkel arguing against free speech, which targeted growing anti-EU sentiments in Poland, also appeared. In the area of international relations, the sampled content included fake news about deportations of Poles from the US, meant to heighten the perceived threat of a break in alliance with the USA among Polish society, as well as about Swedes seeking asylum in Poland, and the introduction of a ban on firearms in France – false information that deepens the perception of Christian values being disavowed in the EU.

Social Category

Social themes, the second most popular category, encompassed the following topics: current affairs, world news, international relations, health and food, and animals. Under currentaffairs were texts about a teachers’ strike in Poland in 2019 and about The Great Orchestra of Holiday Help (Wielka Orkiestra Świątecznej Pomocy), a charity fundraiser that takes place annually in January. World news, in turn, contained texts falsely claiming that Great Britain is banning the phrase “Ladies and Gentlemen,” which targeted gender identity politics. Some content concerned LGBT minorities, as exemplified by fake news with a graphic suggesting that pedophilia is a sexual orientation within these communities (Figure 3) or about the warning supposedly issued by Tinder for its LGBT members about dangers they face in Poland (Figure 4).

The second fake news example claims that Poland is on the list of countries that trigger a Traveler Alert feature on the application Tinder, which warns its users when they are in a country deemed unsafe or with laws that discriminate based on sexual orientation. While the feature does in fact exist on Tinder, Poland is not one of the countries that trigger it. The fake news nevertheless spread among journalists on news portals such as Wirtualna Polska and wirtualnemedia.pl, and its reach was considerable. In time it became apparent that the original version of this fake news appeared on the portal Sputnik, an active tool of Russian disinformation. The first portal to expose the news as fake – EUvsDisinfo (2019) – considered Sputnik’s article an example of pro-Kremlin propaganda (https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/tinder-will-warn-its-users-that-poland-is-a-country-dangerous-for-lgbt). As these two examples clearly show, fake news on the subject of the LGBT communities aim to entrench existing antagonisms and sense of endangerment both among people who identify as LGBT and those who consider these minorities a threat. Indeed, this division is on the rise in Poland and vulnerable to becoming only deeper through practices of disinformation.

Figure 3. Fake Graphic Positing Pedophilia as a Sexual Orientation in the LGBT Community.

Source: Twitter.com

Source: Twitter.com

Figure 4. Fake News About a Tinder Traveler Alert Warning Being Issued for Poland.

Source: Twitter.com

Source: Twitter.com

Worldview Category

A look at worldview themes in the studied sample, which mainly part consisted of religious topics and in especially issues of the Catholic Church and of Christian values, is also in order. Such fake news reported, for example, that the Google corporation was removing crosses from churches, or that there was a secret plans to transform the Notre Dame Cathedral into a shipping arcade, or that religion is considered a mental illness in Ireland. The common denominator of such content is its aim to incite fear of religious discrimination against Christians. In fact, reinforcing the perception of endangerment among Catholics was a noticeable current of disinformation through fake news in 2019, which is partially tied to that year’s two elections and immigration politics, but also to the weakened position of the Catholic Church in Poland. Some the worldview fake news concerned international events (such as the destruction of a Christmas tree by immigrants in Holland, or child marriages in the Islamic culture), civil matters (such as a text about a Catholic priest becoming a Police Commander), and legal issues (fake news of the radical Catholic association “Ordo Iuris” wanting to change the law in order to cover the breasts of the Mermaid of Warsaw statue). These last two examples represent an opposite trend in fake news of presenting Catholics abusing their privileges, or as a threat to freedom, but such instances are noticeably less frequent in Poland.

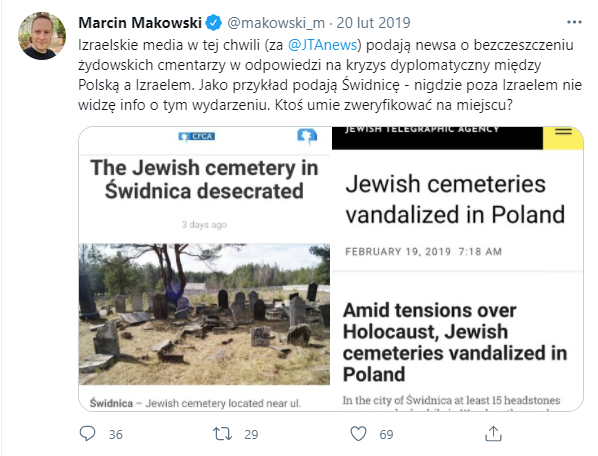

A single, but thought-provoking example of worldview-themed fake news comes from the portal Publiszer and reports on the supposed devastation of a Jewish graveyard in Świdnica (Figure 5). Its classification under the worldview theme follows from the utilized image of a graveyard (a place with religious connotations in Poland) and the implication of anti-Semitism it conveys. Its publication attempts to inscribe this act of vandalism onto the diplomatic tension between Poland and Israel by suggesting that the devastation was motivated by anti-Semitism. The case was made using a statement supposedly made by the now former Prime Minister of Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu, during the US-led Middle East Conference in Warsaw, as reported by the portal of The Jerusalem Post newspaper, namely that “Poles helped Germans murder Jews during the Holocaust.” The report was later debunked by Anna Azari, Israel’s Ambassador to Poland, as well as by Netanyahu’s chancellery, but the Publiszer article nevertheless suggests that these statements provoked the anti-Semitic action in Świdnica. In reality, no such action had taken place; the photographed graveyard is actually in Olkusz and the image is from 2015.

Figure 5. Fake News About the Devastation of a Jewish

Graveyard in Świdnica.

Source: Facebook.com

Figure 6. A Post With a Composite of Israeli Headlines

Referencing the Graveyard in Świdnica.

Source: Twitter.com

As Polish journalists quickly noted on Twitter, however, the fake news had spread to international media, with a series of publications citing Polish sources coming out in Israel in the days that followed (Figure 6). Shortly thereafter, the Polish Ambassador to Israel, Marek Magierowski, asked for the removal of these articles based on their proven falsity. As a result, The Times of Israel removed fragments about Świdnica from their article, noting the error, while the editors of The Jerusalem Post changed their text entirely. The situation nevertheless shows that matters of religion and worldview are significant both domestically, in Poland, and in the realm of international relations.

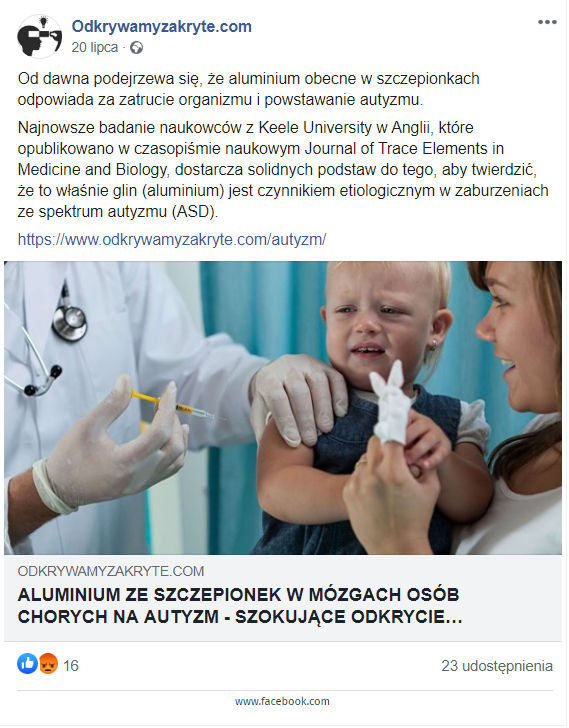

Pseudoscientific Category

The pseudoscientific theme was split into two topic areas: health and global warming. Of note among health-related content are texts linking vaccinations with autism, as well as fearmongering theories about the 5G network killing people, or chemotherapy spreading cancer throughout the entire body. The most enduring fake news from this thematic area asserted a correlation between autism and trace amounts of aluminium in vaccines (Figure 7). This fake news was often shared by portals that promote alternative medical treatments and frequently publish untrue or manipulated information using scientific research to validate their claims. In this specific case, the text describes research into the link between autism and aluminium in vaccines conducted by scientists from Keele University in England, which was published in The Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. The study’s reviewers criticized its authors for looking only at individuals with diagnosed autism and entirely omitting healthy subjects, resulting in conclusions that lacked any comparative analysis. Their results are thus unreliable, a fact not mentioned in the fake news, which posited the correlation as already proven.

Figure 7. Fake News About the Correlation Between Vaccines and Autism.

Source: Facebook.com

Extreme Category

Extreme content accounted for the same number of texts as the pseudoscientific category, and was subdivided into five topics: child endangerment, meaning fake news about kidnappings and physical abuse of children; tragic news from around the world, for instance about terror attacks in Munich and Paris, or brutal rapes in India; acts of violence, such as texts about an attack on civilians by US soldiers stationed in Poland, or the stabbing of a pregnant woman by an Israeli citizen; natural disasters, for example about the supposed damages caused by hurricane Dorian; and abortion, about the use of aborted fetuses in the cosmetic industry. Much of the extreme content is strongly influenced by texts about acts of violence, which is reflected in the phenomenon of tabloidization of news in Polish media (Piontek & Annusewicz, 2013). Within this thematic category, fake news about fires in Siberia met with significant interest (Figure 8). The report of burning Siberian forests and Russia’s conscious decision not to intervene was accompanied by photos of suffering animals. In fact, however, the images were made by the US artists Jim Tschetter and Mike McMillan and related to fires in California in 2000 rather than Siberia. Notably, posts about forest fires in Siberia with illustrative graphics and inadequate photos appeared not only in Poland, but also in Italy, Bulgaria, and Greece. This example was also the only fake news in the studied sample that aimed directly at Russia’s domestic politics and its negative ecological effects.

Figure 8. Fake News About Forest Fires in Siberia.

Source: Twitter.com

Discussion

The research presented here classifies fake news into thematic categories using content analysis to provide a basis for identifying areas particularly vulnerable to the phenomenon in the Polish social context. The process yielded eight thematic categories of fake news (Figure 1), with study results showing an anti-government or anti-nationalist tendency in a majority of analysed fake news content, as revealed by the top five identified categories and confirmed by their detailed analysis. The thematic areas of highest significance for Poland are thus politics, especially the actions of current government; society, especially issues of sexual orientation and LGBT minorities; religion, primarily the issues of the Catholic Church and of the Islamic culture; and health, with focus on information about vaccines and pharmacological treatment.

Political and economic content emerged as the most frequently affected thematic area, which confirms conclusions of researchers identifying it as the most popular type of fake news (Aldwairi, 2018; Horne & Adalı, 2017; Meyer, 2018; Silverman, 2016). As already mentioned, among the 41 examples of fake news about politicians in the studied sample, 25 were about figures from the ruling Law and Justice party, with a number of examples also relating to changes in the law and Poland’s international politics. Political and economic content emerged as the most frequently affected thematic area, which confirms conclusions of researchers identifying it as the most popular type of fake news (Aldwairi, 2018; Horne & Adalı, 2017; Meyer, 2018; Silverman, 2016). The political and economic content most often aimed against the government and relied on stoking a sense of separateness and the national sentiments that run deep among Poles, stirring the perception of either their endangerment or superiority. The strong patriotic values that the ruling party embraced in their promotional materials during the parliamentary 2019 election campaign thus became frequent fodder for politically-themed fake news that year. On the one hand, such fake news alienates that part of Polish society who still holds patriotism as a core value; on the other, in framing patriotism as a point of embarrassment rather than pride, such attacks erode the ground on which Polish society can build a broader understanding of its national identity. In the end, the only party to benefit from this situation is social conflict itself.

The second most substantial area of fake news in the Polish context, namely socially-themed content, contains many texts related to issues of gender identity and LGBT minorities. These issues were widely discussed by all of Poland’s political parties during the election campaign, which notably increased the occurrence of related fake news. The debate around the theme of sexuality has been ongoing in Poland for many years, in fact, with only its scale expanding during political campaigns (Mikulska-Jolles, 2020). In a Polish context, this subject can thus be considered as permanently vulnerable to disinformation. Much of the false content suggested either that LGBT people face danger in Poland, or that the LGBT community poses a threat to Poles. This is a key observation that shows a kind of dualism typically at work in fake news. On the one hand, this thematic content reinforces the majority’s defensive reaction against sexual minorities by suggesting that they are aggressive and authoritarian, while on the other it strengthens the sense of endangerment of LGBT communities in Poland and encourages more aggressive battles for its rights, which are presented as threatened or disrespected. The radicalism on both sides of the debate is thus boosted through manipulation of specific fears. The aggression provoked by such fake news appears to be the intended aim of politicians with extreme views, although this hypothesis requires further testing and a new set of categories for analysis.

The high number of fake news in the worldview category, and particularly of religious topics, was another telling finding in terms of the specifics of Polish media reality. Since Polish society remains strongly tied to Catholicism (Domagała, 2018), topics related to the Catholic Church are markedly sensitive and vulnerable to disinformation. A considerable portion of fake news in this category concerned negative representations of the Catholic Church in Poland or potential attacks of foreign corporations on it, with some aiming also at the nature of Islam, especially in the contexts of child marriages, terrorist attacks, and other threats associated with Islamic culture. A recognizable dualism again makes its appearance here. The strong impression of danger created by fake news of attacks on the Catholic Church can be interpreted as intentional fuel for promoting religious radicalism in Polish society (Izak, 2015). Paradoxically, this goes against the official position of the Catholic Church, which has clearly signalled its opposition to religious extremism after the Second Vatican Council (Ratzinger, 2005). On the other hand, some of the content suggests aggression by the Catholic Church, which may aim at fragmenting its community through disinformation about religious subjects. In addition, bolstering fundamentalism can serve to weaken the Polish national collective, which has drawn its strength from social solidarity in the past (Davies, 2014). For these reasons, the worldview category of fake news requires further, more detailed analysis in the Polish context.

The significant amount of (thematically) pseudoscientific fake news about health was another key finding of the study. Health is the second most popular individual topic in the studied sample, with 14 health-oriented articles having a strong anti-vaccination current. This was also an area where many fake news repeated from previous years, which points to the longevity of false pseudoscientific messaging (Golbeck et al., 2018; Pennycook & Rand, 2019). Based on this analysis, pseudoscientific and health-oriented fake news remain in circulation and recipients’ consciousness longer than other types of disinformation, with their influence being renewed by new circumstances. Of significance here is the fact that most pseudoscientific fake news were translated copies of English-language texts. In contrast to political and social content, pseudoscientific fake news appears to be more global in character and reflective of general anti-scientific tendencies. There is certainly good reason to think that both the sense of danger and the intensification of chaos in media messaging factor significantly into the number and perception of pseudoscientific fake news (Heine et al., 2006). In the current pandemic situation, this is a particularly negative prospect. Analysis indicates that anti-vaccination tendencies are long-lasting and can survive in the social consciousness for decades, which makes monitoring fake news about the coronavirus in real time to counteract its spread of utmost importance.

While providing new insight into the phenomenon of fake news in Poland, the scope of this study had necessary limits, with one related to data collection. Fact-checking sites, which were a key source in this study, can display a bias in identifying fake news (Pennycook & Rand, 2019). They are, for one, financed by different kinds of media organizations that often hold specific points of view. While a triple verification of these sites was sufficient for this qualitative analysis, it is certainly an area for development in terms of quantitative analysis that is ultimately needed to verify conclusions presented here, and which requires access to more data from more diverse sources. Another limit concerns the time span covered by analysis, with the year of 2019 chosen for reasons of methodology in this study. Expanding the publication timeframe of analysed materials would undoubtedly add nuance to the resulting image of the fake news phenomenon. The amount of fake news about the coronavirus that emerged only a year later (Escolà-Gascón et al., 2021) makes considering the possible impact of this global situation on the thematic map of fake news in Poland arrived at through the study a worthwhile endeavour.

To get a preliminary sense of what such analysis may reveal and to add more depth to this discussion, a sample of 299 examples of fake news in Poland from 2020 was assessed. The fact that the Polish presidential election took place that year is helpful from a comparative perspective, though it must also be noted that all examples were sourced from the portal Demagog, deemed most impartial for being both independent and IFCN accredited. Based on this prefatory analysis and somewhat surprisingly, the Covid-19 pandemic did not impact the key fissures in information pertaining to both political and religious matters in Poland. While the Covid-19 crisis increased the number of pseudoscientific fake news in 2020 to 33% in the sampled data (97 instances), many of these repeated fake news about vaccines from 2019, with the only difference being in their overt targeting of the coronavirus vaccines. This again points to the longevity of pseudoscientific misinformation. Given that new content that was directly related to the coronavirus and measures of protection against it also appeared in the 2020 sample (for example, fake news about negative effects of wearing face masks), it is not unreasonable to expect its return in an updated form on occasion of another global health crisis.

Despite a notable increase in health-related fake news in 2020, the largest part of the sampled data still concerned politics (45%, or 135 instances) and still displayed an anti-government tendency, with 39% of the political content (52 instances) aimed at undercutting the ruling party in comparison to the 19% (25 instances) directed at its opposition. Indeed, if the sampled data is representative of the fake news phenomenon in Poland in 2020, the percentage of anti-government content grew from the previous year, with the pandemic intensifying political disinformation, now aimed also at health policies. This result finds partial collaboration in the research of Edson Tandoc and colleagues (2021), which found that the greatest number of analyzed fake news in USA during 2017-2018 related to its government’s politics (51.6%). It is thus feasible to surmise that the tendency of fake news to target governments in power is part of a broader action of disinformation, which possibly aims to destabilize societies and undermine their trust in the government.

The active role of fake news in the US presidential election of 2016 (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017; Grinberg et al., 2019) and the events around the more recent election of 2020 provide solid ground for a comparative exploration of the phenomenon of politically motivated fake news in Poland and the USA. The case of the United States already reveals some long-term effects of disinformation via fake news, including escalation of social conflicts. Fake news from 2016 fuelled negative emotion toward political powers in the media and worked to strengthen oppositional attitudes towards the Democratic Party then in power. These attitudes found their main outlet on social media, and indeed are one possible reason behind Donald Trump’s election to the office of the US president (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017). During his presidential term, however, media narration about domestic social conflicts intensified, heightening the sense of threat felt by various groups. His presidential term was characterized by numerous protests, including the Women’s March in 2017 and, more recently and perhaps most significantly, Black Lives Matter (Cambridge Dictionary). Leaving aside their merits and looking only at the emotions at play in street protests signals an escalation in social conflicts and a transfer of social life from virtual to real spaces. One of the aims of Russian strategic disinformation, to recall, is a strong emotional incitement of the population, precisely through false narrations about various dangers it faces. This seems noteworthy in light of the attack on the United States Capitol on January 6th, 2021. After Joe Biden’s electoral victory in the 2020 presidential election, during the period of transition, news about the falsification of the election intensified, escalating negative social emotions that found an outlet in a crowd storming the Capitol Building, which ended with the death of five people and multiple injuries (Evelyn, 2021). These events clearly speak to the intensification of social conflicts in the United States. These conflicts, moreover, are growing on both sides of the political spectrum and share in their oppositional character toward democratically elected representatives. It is a worrying demonstration of the dangers of social polarization, which has already been linked to higher occurrence of fake news, especially among people on the farther extremeof the political spectrum (Narayanan et al., 2018).

The varied social dynamic in Poland and the United States makes their comparison in relation to the fake news phenomenon valuable not only in terms of identifying commonalities, but also by way of pin-pointing aspects that are specific to each cultural context. While disinformation in Poland is often anti-government in character and capitalizes on feelings of social endangerment, especially among minority groups, there are significant differences between the affected groups that follow from the specific demographics and histories of each nation. Some of these differences are likely to emerge on analysis of the socially-themed fake news, which continue to play a significant part in the phenomenon in Poland. The preliminary look at fake news in Poland from 2020, for instance, shows the impact of the tightening abortion laws in the country, with the subject of women’s rights appearing alongside LGBT topics within the social category, which constituted 12% (or 37 cases) of the sample. The subject of abortion also affected the number and tone of fake news related to the Catholic Church (11%, or 32 instances). Whereas in 2019, more fake news presented the church as a victim of oppressive actions, in 2020 this tendency reversed, with the church more frequently appearing as the oppressor, discriminatory of both women and minorities. The cumulative effect of both these fake news currents – the first strengthening the sense of external threats among Catholics, the second doing likewise among those opposed to the Catholic Church – has likely played a part in the increase of street violence, attacks on church properties, and destruction of monuments observed during 2020 (https://www.gov.pl/web/mswia/oswiadczenie-ministra-spraw-wewnetrznych-i-administracji-ws-atakow-na-koscioly), echoing the transfer of social emotions from virtual to real spaces mentioned above in relation to the USA.

This cursory look at fake news from 2020 suggests that the thematic analysis of data from 2019 conducted in this study accurately identified key areas of vulnerability to the phenomenon in the Polish context, and that analyses of this kind are both necessary and useful in predicting and possibly counteracting future fake news targets. Such results can be utilized by fact-checking organizations in their work of debunking disinformation, for instance by matching themes that see an increase in the number and popularity of fake news with groups of so-called guardians who will effectively distribute verified information within given subject areas. Such guardians are active internet users who selflessly engage in disseminating truthful content and have a significant influence on disproving fake content (Vo & Lee, 2018). It is already proven that the debunking effect grows in effectiveness and longevity as the number of verified articles that discredit fake news increases and when internet users encounter them over time more frequently (Chan et al., 2017; Pennycook et al., 2018; Tandoc, 2019). Additionally, knowledge of the specific topics that are characteristic of disinformation and of key words that occur in such contexts can aid the creation of more effective automatic verification process with the help of AI and machine learning. Development of automated procedures can make the process of fighting disinformation more efficient and has already been utilized to some extent in the case of fake news about Covid-19 (Shahi & Nadini, 2020).

Identifying the thematic areas and topics most at risk of disinformation attacks in Poland is a step to better understanding their social specificity and sphere of influence, both at home and elsewhere. The conclusions drawn here ketch out varied paths for future research, which should cover longer periods and intervals of time to arrive at more detailed information about the evolution of fake news. Cultural differentiation, especially among countries that make up the European Union (from the Polish and European perspective, in any case), is an important factor to consider. Poland is not a W.E.I.R.D. nation (Henrich et al., 2010) and the specificity of its culture and media space has a marked impact on the collected data and offered conclusions. This only makes possible differences between subjects most at risk of disinformation in individual countries a more intriguing and pressing question to address. Such research could prove foundational to a specialized network for information verification in the future; multilateral research undertaken by individual nations as well as regional and global coalitions could shed much needed light on the phenomenon.

Acknowledgement

First and foremost, I want to extend my sincere thanks to Agnieszka Polakowska for her translation, conversations and comments that significantly improved the manuscript and to Professor Tamara Trojanowska for her support of this paper. My gratitude goes to the Institute of Media Education and Journalism at the Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University in Warsaw for its financial support of this publication. I feel a deep sense of gratitude to Dr. Anna Miotk and Dr. Bartłomiej Łódzki for their content analysis and coding procedure and the four anonymous reviewers' comments and suggestions. Last but not least, I want to thank the editor of this journal, Dr. Lenka Dedkova, for her helpful advice.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2021 Klaudia A. Rosińska