Body talk on social network sites and body dissatisfaction among college students: The mediating roles of appearance ideals internalization and appearance comparison

Vol.16,No.3(2022)

The present study investigated the association between body talk on social networking sites (SNS) and body dissatisfaction as well as the mediating effects of appearance ideals internalization and appearance comparison in this relationship. Participants were 476 Chinese college students who completed questionnaires regarding SNS body talk, thin-ideal internalization, muscular-ideal internalization, general attractiveness internalization, appearance comparison, and body dissatisfaction. Results indicated that SNS body talk was positively linked to body dissatisfaction. The relationship between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction was mediated by thin-ideal internalization and muscular-ideal internalization while the mediating effects of general attractiveness internalization and appearance comparison in this relationship were nonsignificant. Moderated mediation analysis further revealed that thin-ideal internalization mediated the association for women but not men and that other indirect effects did not differ among genders. The findings of this study provide more insights into the relationship between SNS use and body image.

SNS body talk; internalization of appearance ideals; appearance comparison; body dissatisfaction

Yuhui Wang

Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Beijing University of Technology; Beijing Social Governance Research Center, Beijing University of Technology

Yuhui Wang (Ph.D, Renmin University of China, 2020) is a researcher in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Beijing University of Technology, China. Her research focuses on social media use and body image.

Jingyu Geng

Department of Psychology, Renmin University of China

Jingyu Geng is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Psychology, Renmin University of China, China. She is interested in Internet use and the development of young people.

Ke Di

Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Beijing University of Technology

Ke Di (MA, University of Melbourne, 2013) is a lecturer in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Beijing University of Technology, China. Her research focuses on foreign language education and language teaching pedagogy.

Xiaoyuan Chu

Department of Psychology, Renmin University of China; School of Economics and Management, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications

Xiaoyuan Chu (Ph.D, Beijing Normal University, 2016) is an associate professor in the School of Economics and Management, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunication, China. His research focuses on social media use and cyberpsychology.

Li Lei

School of Education, Renmin University of China

Li Lei (Ph.D, Beijing Normal University, 1997) is a professor in the School of Education, Renmin University of China, China. His research interests include Internet use and the development of adolescents.

Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Arroyo, A., & Brunner, S. R. (2016). Negative body talk as an outcome of friends’ fitness posts on social networking sites: Body surveillance and social comparison as potential moderators. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 44(3), 216–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2016.1192293

Bell, H. S., Donovan, C. L., & Ramme, R. (2016). Is athletic really ideal? An examination of the mediating role of body dissatisfaction in predicting disordered eating and compulsive exercise. Eating Behaviors, 21, 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.12.012

Bucchianeri, M. M., Arikian, A. J., Hannan, P. J., Eisenberg, M. E., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2013). Body dissatisfaction from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Body Image, 10(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.09.001

Buote, V. M., Wilson, A. E., Strahan, E. J., Gazzola, S. B., & Papps, F. (2011). Setting the bar: Divergent sociocultural norms for women's and men's ideal appearance in real-world contexts. Body Image, 8(4), 322–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.06.002

Cafri, G., Yamamiya, Y., Brannick, M., & Thompson, J. K. (2005). The influence of sociocultural factors on body image: A meta‐analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 12(4), 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpi053

Calogero, R. M., Davis, W. N., & Thompson, J. K. (2004). The Sociocultural Attitudes Toward Appearance Questionnaire (SATAQ-3): Reliability and normative comparisons of eating disordered patients. Body Image, 1(2), 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.01.004

Cash, T. F. (2000). Multidimensional Body–Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ). American Psychological Association and Oxford University Press.

Chen, H., Gao, X., & Jackson, T. (2007). Predictive models for understanding body dissatisfaction among young males and females in China. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(6), 1345–1356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.015

Chow, C. M., & Tan, C. C. (2016). Weight status, negative body talk, and body dissatisfaction: A dyadic analysis of male friends. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(8), 1597–1606. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314559621

Davis, L. L., Fowler, S. A., Best, L. A., & Both, L. E. (2020). The role of body image in the prediction of life satisfaction and flourishing in men and women. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(2), 505–524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00093-y

De Jesus, A. Y., Ricciardelli, L. A., Frisén, A., Smolak, L., Yager, Z., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., Diedrichs, P. C., Franko, D., Holmqvist, K., & Gattario, K. H. (2015). Media internalization and conformity to traditional masculine norms in relation to body image concerns among men. Eating Behaviors, 18, 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.04.004

Donovan, C. L., Uhlmann, L. R., & Loxton, N. J. (2020). Strong is the new skinny, but is it ideal?: A test of the tripartite influence model using a new measure of fit-ideal internalisation. Body Image, 35, 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.09.002

Engeln, R., Sladek, M. R., & Waldron, H. (2013). Body talk among college men: Content, correlates, and effects. Body Image, 10(3), 300–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.02.001

Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2015). Negative comparisons about one's appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body Image, 12, 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.10.004

Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2016). Social media and body image concerns: Current research and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.005

Fardouly, J., Willburger, B. K., & Vartanian, L. R. (2018). Instagram use and young women’s body image concerns and self-objectification: Testing mediational pathways. New Media & Society, 20(4), 1380–1395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817694499

Feltman, C. E., & Szymanski, D. M. (2018). Instagram use and self-objectification: The roles of internalization, comparison, appearance commentary, and feminism. Sex Roles, 78(5–6), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0796-1

Girard, M., Chabrol, H., & Rodgers, R. F. (2018). Support for a modified tripartite dual pathway model of body image concerns and risky body change behaviors in French young men. Sex Roles, 78(11–12), 799–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0850-z

Greenberg, B. S. (1988). Some uncommon television images and the drench hypothesis. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Television as a social issue (pp. 88–102). Sage.

Halliwell, E., & Harvey, M. (2006). Examination of a sociocultural model of disordered eating among male and female adolescents. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11(2), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910705X39214

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Homan, K. (2010). Athletic-ideal and thin-ideal internalization as prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction, dieting, and compulsive exercise. Body Image, 7(3), 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.02.004

Hummel, A. C., & Smith, A. R. (2015). Ask and you shall receive: Desire and receipt of feedback via Facebook predicts disordered eating concerns. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(4), 436–442. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22336

iiMedia Research. (2020, March 20). 2019-2020 China mobile social industry annual research report. https://www.iimedia.cn/c400/70165.html

Jackson, K. L., Janssen, I., Appelhans, B. M., Kazlauskaite, R., Karavolos, K., Dugan, S. A., Avery, E. A., Ship-Johnson, K. J., Powell, L. H., & Kravitz, H. M. (2014). Body image satisfaction and depression in midlife women: The study of women's health across the nation (SWAN). Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 17(3), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0416-9

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2015). Predictors of cosmetic surgery consideration among young Chinese women and men. Sex Roles, 73(5–6), 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0514-9

Jarman, H. K., Marques, M. D., McLean, S. A., Slater, A., & Paxton, S. J. (2021). Social media, body satisfaction and well-being among adolescents: A mediation model of appearance-ideal internalization and comparison. Body Image, 36, 139–148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.11.005

Jones, D. C., & Crawford, J. K. (2006). The peer appearance culture during adolescence: Gender and body mass variations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(2), Article 243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-9006-5

Jones, D. C., Vigfusdottir, T. H., & Lee, Y. (2004). Body image and the appearance culture among adolescent girls and boys: An examination of friend conversations, peer criticism, appearance magazines, and the internalization of appearance ideals. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19(3), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558403258847

Karazsia, B. T., & Crowther, J. H. (2009). Social body comparison and internalization: Mediators of social influences on men's muscularity-oriented body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 6(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.12.003

Keery, H., van den Berg, P., & Thompson, J. K. (2004). An evaluation of the tripartite influence model of body dissatisfaction and eating disturbance with adolescent girls. Body Image, 1(3), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.03.001

Kim, J. W., & Chock, T. M. (2015). Body image 2.0: Associations between social grooming on Facebook and body image concerns. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.009

Lin, L., Flynn, M., & O’Dell, D. (2021). Measuring positive and negative body talk in men and women: The development and validation of the Body Talk Scale. Body Image, 37, 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.01.013

Lockwood, P., & Kunda, Z. (1997). Superstars and me: Predicting the impact of role models on the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.91

Matera, C., Nerini, A., & Stefanile, C. (2013). The role of peer influence on girls’ body dissatisfaction and dieting. European Review of Applied Psychology, 63(2), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2012.08.002

Mccreary, D. R., & Sasse, D. K. (2000). An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. Journal of American College Health, 48(6), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480009596271

McNeill, L. S., & Firman, J. L. (2014). Ideal body image: A male perspective on self. Australasian Marketing Journal, 22(2), 136–143. https://doi.org//10.1016/j.ausmj.2014.04.001

Meier, E. P., & Gray, J. (2014). Facebook photo activity associated with body image disturbance in adolescent girls. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(4), 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0305

Mills, J., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2017). Fat talk and body image disturbance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41(1), 114–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684316675317

Myers, T. A., & Crowther, J. H. (2009). Social comparison as a predictor of body dissatisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(4), 683–698. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016763

Nichter, M., & Vuckovic, N. (1994). Fat talk: Body image among adolescent girls. In N. L. Sault (Ed.), Many mirrors: Body image and social relations. Rutgers University Press.

Paterna, A., Alcaraz‐Ibáñez, M., Fuller‐Tyszkiewicz, M., & Sicilia, Á. (2021). Internalization of body shape ideals and body dissatisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(9), 1575–1600. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23568

Pope, H. G., Jr., Gruber, A. J., Mangweth, B., Bureau, B., deCol, C., Jouvent, R., & Hudson, J. I. (2000). Body image perception among men in three countries. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(8), 1297–1301. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1297

Ramme, R. A., Donovan, C. L., & Bell, H. S. (2016). A test of athletic internalisation as a mediator in the relationship between sociocultural influences and body dissatisfaction in women. Body Image, 16, 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.01.002

Rodgers, R., Chabrol, H., & Paxton, S. J. (2011). An exploration of the tripartite influence model of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among Australian and French college women. Body Image, 8(3), 208–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.04.009

Rodgers, R. F., Slater, A., Gordon, C. S., McLean, S. A., Jarman, H. K., & Paxton, S. J. (2020). A biopsychosocial model of social media use and body image concerns, disordered eating, and muscle-building behaviors among adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(2), 399–409. https:/doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01190-0

Rousseau, A., Eggermont, S., & Frison, E. (2017). The reciprocal and indirect relationships between passive Facebook use, comparison on Facebook, and adolescents' body dissatisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.056

Schaefer, L. M., Harriger, J. A., Heinberg, L. J., Soderberg, T., & Thompson, J. K. (2017). Development and validation of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire‐4‐Revised (SATAQ‐4R). International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(2), 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22590

Sharp, G., Tiggemann, M., & Mattiske, J. (2014). The role of media and peer influences in Australian women's attitudes towards cosmetic surgery. Body Image, 11(4), 482–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.07.009

Sharpe, H., Naumann, U., Treasure, J., & Schmidt, U. (2013). Is fat talking a causal risk factor for body dissatisfaction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46(7), 643–652. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22151

Shin, K., You, S., & Kim, E. (2016). Sociocultural pressure, internalization, BMI, exercise, and body dissatisfaction in Korean female college students. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(13), 1712–1720. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316634450

Shroff, H., & Thompson, J. K. (2006). Peer influences, body-image dissatisfaction, eating dysfunction and self-esteem in adolescent girls. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(4), 533–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105306065015

Smolak, L., Murnen, S. K., & Thompson, J. K. (2005). Sociocultural influences and muscle building in adolescent boys. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 6(4), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.6.4.227

Stice, E. (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(5), 825–848. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.128.5.825

Stojcic, I., Dong, X., & Ren, X. (2020). Body image and sociocultural predictors of body image dissatisfaction in Croatian and Chinese women. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 731. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00731

Stratton, R., Donovan, C., Bramwell, S., & Loxton, N. J. (2015). Don’t stop till you get enough: Factors driving men towards muscularity. Body Image, 15, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.07.002

Taniguchi, E., & Lee, H. E. (2012). Cross-cultural differences between Japanese and American female college students in the effects of witnessing fat talk on Facebook. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 41(3), 260–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2012.728769

Taniguchi, E., & Lee, H. E. (2013). Effects of witnessing fat talk on body satisfaction and psychological well-being: A cross-cultural comparison of Korea and the United States. Social Behavior and Personality, 41(8), 1279–1295. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2013.41.8.1279

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. American Psychological Association.

Tiggemann, M., Hayden, S., Brown, Z., & Veldhuis, J. (2018). The effect of Instagram “likes” on women’s social comparison and body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 26, 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.07.002

Tylka, T. L. (2011). Refinement of the tripartite influence model for men: Dual body image pathways to body change behaviors. Body Image, 8(3), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.04.008

Tylka, T. L., Bergeron, D., & Schwartz, J. P. (2005). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Male Body Attitudes Scale (MBAS). Body Image, 2(2), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.001

van den Berg, P., Paxton, S. J., Keery, H., Wall, M., Guo, J., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2007). Body dissatisfaction and body comparison with media images in males and females. Body Image, 4(3), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.04.003

Vartanian, L. R., Hayward, L. E., Smyth, J. M., Paxton, S. J., & Touyz, S. W. (2018). Risk and resiliency factors related to body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: The identity disruption model. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(4), 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22835

Walker, M., Thornton, L., De Choudhury, M., Teevan, J., Bulik, C. M., Levinson, C. A., & Zerwas, S. (2015). Facebook use and disordered eating in college-aged women. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(2), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.026

Wang, K., Liang, R., Ma, Z -L., Chen, J., Cheung, E. F. C., Roalf, D. R., Gur, R. C., & Chan, R. C. K. (2018). Body image attitude among Chinese college students. PsyCh Journal, 7(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.200

Wang, Y., Wang, X., Yang, J., Zeng, P., & Lei, L. (2020). Body talk on social networking sites, body surveillance, and body shame among young adults: The roles of self-compassion and gender. Sex Roles, 82(11–12), 731–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01084-2

Wang, Y., Yang, J., Wang, J., Yin, L., & Lei, L. (2020). Body talk on social networking sites and body dissatisfaction among young women: A moderated mediation model of peer appearance pressure and self-compassion. Current Psychology, 41, 1584–1594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00704-5

Webb, J. B., Vinoski, E. R., Bonar, A. S., Davies, A. E., & Etzel, L. (2017). Fat is fashionable and fit: A comparative content analysis of Fatspiration and Health at Every Size® Instagram images. Body Image, 22, 53–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.05.003

Yamamiya, Y., Shroff, H., & Thompson, J. K. (2008). The tripartite influence model of body image and eating disturbance: A replication with a Japanese sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(1), 88–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20444

Authors’ Contribution

Yuhui Wang: conceptualization, writing-original draft, and funding acquisition. Jingyu Geng: methodology and formal analysis. Ke Di: writing-review & editing. Xiaoyuan Chu: investigation and visualization. Li Lei: supervision and conceptualization.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

December 2, 2020

Revisions received:

June 8, 2021

October 2, 2021

January 16, 2022

April 9, 2022

Accepted for publication:

May 4, 2022

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

Body dissatisfaction has been a common concern in related academia as it is associated with many health problems, such as eating disorders, depression, low self-esteem, decreased life satisfaction, and low subjective well-being (Davis et al., 2020; K. L. Jackson et al., 2014; Stice, 2002; K. Wang et al., 2018). In recent years, body dissatisfaction has also become increasingly prevalent among Chinese. A recent study focusing on Chinese college students found that over 87% of the participants were dissatisfied with their bodies and the extent of body dissatisfaction was comparable for men and women (K. Wang et al., 2018). Considering the prevalence of body dissatisfaction among Chinese people, the present study thus focused on young Chinese adults to explore the potential antecedents of body dissatisfaction.

Stemming from sociocultural theory, Thompson et al. (1999) proposed the tripartite influence model to explain the development of body dissatisfaction, in which sociocultural influences (i.e., media, peers, and family) have direct and indirect effects (via the mediating role of appearance ideals internalization and appearance comparison) on body dissatisfaction. This theoretical framework is originally developed to explain female body dissatisfaction in Western culture, and now it has been supported among boys and men (Karazsia & Crowther, 2009; Smolak et al., 2005; Tylka, 2011), as well as populations from various non-Western countries (Chen et al., 2007; Shin et al., 2016; Yamamiya et al., 2008). In the last two decades, with the popularity of social networking sites (SNS), scholars applied the tripartite influence model to examine the influence of SNS use on body image concerns and have gained empirical support (e.g., Fardouly et al., 2018; Feltman & Szymanski, 2018). Some researchers, however, suggested examining the effect of specific SNS activities on body dissatisfaction because they did not find a significant association between general SNS use (e.g., total use time and frequency) and body image concerns (Kim & Chock, 2015; Meier & Gray, 2014). A representative activity on SNS that might relate to body image concerns is interpersonal appearance-related interaction.

Nichter and Vuckovic (1994) originally coined the term ‘‘fat talk’’ to refer to conversations about the body size/shape among groups of girls and women (typically in a negative manner). As more and more boys and men are engaging in appearance conversations and the contents they are talking about are not just about body fat, but also about muscle-building and other physical features, the term “body talk” is developed to refer to appearance-related interactions in general. It is defined as interpersonal interactions that focus attention on physical appearance, reinforce the value of appearance, and promote the construction of appearance ideals, which is also known as appearance conversation (Jones & Crawford, 2006; Y. Wang, Wang, et al., 2020). Previous research has documented that offline fat talk or body talk is a risk factor of body dissatisfaction (see reviews; Mills & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, 2017; Sharpe et al., 2013). As body talk happens mostly in peer interactions and SNS have become popular platforms for friends to communicate with each other, the present study thus focused on body talk with friends on SNS (hereinafter termed as SNS body talk) to explore its association with body dissatisfaction as well as the mediating roles of appearance ideals internalization and appearance comparison in this relationship. The potential gender differences in these associations were also investigated.

SNS Body Talk and Body Dissatisfaction

Nowadays, it is ubiquitous to use SNS, especially among young people. For example, the number of Chinese SNS users in 2019 was 862 million and it is expected to exceed 900 million by 2020, with young people accounting for 43.8% (iiMedia Research, 2020). SNS may provide spaces for the propagation of body talk (Hummel & Smith, 2015; Walker et al., 2015). Specifically, when SNS users post updates or photographs related to physical appearance, some of their SNS friends may leave comments, and the posters would, in turn, reply to these comments. Similarly, users could also actively comment on their friends’ appearance-related status on SNS and gain feedback. As a result, with the interaction of “comment-reply”, body talk would be induced (Walker et al., 2015). For instance, a previous study showed that exposure to friends’ fitness posts on SNS was positively related to body talk (Arroyo & Brunner, 2016).

Limited research, however, has investigated the influence of SNS body talk on body dissatisfaction. To our knowledge, two studies examined the impacts of viewing body talk on Facebook on women’s body dissatisfaction. They revealed that, in the Japanese context, women who witnessed thin-promoting comments reported lower levels of body satisfaction than those who browsed thin-discouraging ones, while this finding was not observed for women from Korea and U.S. (Taniguchi & Lee, 2012, 2013). It is important to note that passive exposure to others’ comments cannot represent active engagement and the interactive feature of body talk. Recently, one study examined the relationship between engaging in body talk on SNS and body dissatisfaction and found that SNS body talk was positively associated with body dissatisfaction among women (Y. Wang, Yang, et al., 2020). However, this study was conducted by using a sample of women and thus could not examine the possible gender differences. Therefore, the present study would examine the relationship between engaging in SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction among both men and women.

The Mediating Role of Appearance Ideals Internalization

According to the tripartite influence model, appearance ideals internalization is an important mediator between sociocultural influences and body dissatisfaction (Thompson et al., 1999). Appearance ideals internalization refers to the extent to which an individual cognitively buys into socially prescribed appearance ideals and expresses a desire to attain such ideals. The mediating role of appearance ideals internalization in the relationship between sociocultural pressures and body image concerns has been documented by previous research (e.g., Feltman & Szymanski, 2018; Shin et al., 2016). Body talk could direct attention to appearance-related issues, reinforce sociocultural standards of beauty, and promote the internalization of appearance ideals. The positive association between body talk and appearance ideals internalization has been identified in previous research (see Mills & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, 2017, for a review). In fact, there is some evidence that appearance ideals internalization mediates the relationship between offline body talk and body dissatisfaction (Matera et al., 2013; Sharp et al., 2014).

Thin ideal has been the dominant description of female attractiveness and its internalization has repeatedly been documented to predict body dissatisfaction (see Cafri et al., 2005, for a review). Recently, a new female cultural appearance ideal has appeared alongside the thin ideal, which is more athletic or muscular, termed as athletic/muscular ideal (Stojcic et al., 2020). Research on the relationship between muscular-ideal internalization and body dissatisfaction among women has somewhat inconsistent findings. One study found a positive association between athletic-ideal internalization and body dissatisfaction (Calogero et al., 2004), while the other one showed that muscular-ideal internalization was not associated with body dissatisfaction (Bell et al., 2016). Furthermore, research examining the role of thin-ideal internalization and muscular-ideal internalization in female body dissatisfaction simultaneously found that both of these two factors were positively and significantly associated with body dissatisfaction (Vartanian et al., 2018). Another study, however, showed that athletic-ideal internalization predicted changes in compulsive exercise over time but not body dissatisfaction or dieting, while thin-ideal internalization predicted changes in all three outcomes (Homan, 2010). Ramme et al. (2016) further found that thin-ideal internalization mediated the relationship between sociocultural influences and body dissatisfaction, while athletic-ideal internalization did not.

Early research on male body image has documented that the ideal body shape for men is with high muscularity (Mccreary & Sasse, 2000; Pope et al., 2000). Recently, however, male ideal body has shifted from being purely muscular to being low in body fat and high in muscularity (McNeill & Firman, 2014). K. Wang et al. (2018) found that for Chinese men who were not satisfied with their body, the proportion of those who want a slender figure (53.4%) was comparable to that of those who desire a fuller one (46.6%). Research focusing on the relationship between appearance ideals internalization and body dissatisfaction found that thin-ideal internalization and muscular-ideal internalization were positively and significantly associated with body dissatisfaction for men (Vartanian et al., 2018). However, to our knowledge, research that simultaneously examines the mediating roles of both thin-ideal internalization and muscular-ideal internalization in the relationship between sociocultural influences and male body dissatisfaction remains insufficient.

Although some studies have examined the role of thin-ideal internalization and muscular-ideal internalization in the development of body dissatisfaction for women or men, the mediating effects of thin-ideal internalization and muscular-ideal internalization in the relationship between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction among both men and women are still unclear. Furthermore, prior research focusing on the mediating role of appearance ideals internalization in the relation between offline body talk and body dissatisfaction did not distinguish different types of internalization in one study. Schaefer et al. (2017) developed the sociocultural attitudes toward appearance questionnaire-4-revised (SATAQ-4R), which addressed the limitations in previous scale and measured internalization from three dimensions: thin-ideal internalization, muscular-ideal internalization, and general attractiveness internalization. The present study hence simultaneously examined the mediating role of thin-ideal internalization, muscular-ideal internalization, and general attractiveness internalization in the relationship between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction among both young men and women.

The Mediating Role of Appearance Comparison

Another important mechanism underlying the link between sociocultural influences and body dissatisfaction, which was proposed in the tripartite influence model, is appearance comparison (Thompson et al., 1999). According to this model, exposure to sociocultural influences would contribute to a greater tendency to make social appearance comparisons, such as comparing with images in the media, which in turn would result in body dissatisfaction because the idealized nature of images would make upward appearance comparisons particularly likely. The mediating role of appearance comparison has been identified by a wide range of research. For example, previous studies showed that appearance comparison mediated the link between SNS use and body image concerns (Fardouly & Vartanian, 2015; Kim & Chock, 2015). With regard to the present study, appearance comparison might mediate the relationship between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction.

Body talk involves scrutiny of one’s own appearance or that of others, thus it is not surprising that those who engage in body talk would commonly participate in appearance-comparing behaviors (Mills & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, 2017). For instance, a meta-analysis identified the significant cross-sectional and prospective correlations between body talk and appearance comparison (Mills & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, 2017). Specific to SNS body talk, a study found that there was a positive association between body talk on Facebook and appearance comparison (Walker et al., 2015). In turn, appearance comparison would lead to body dissatisfaction according to the tripartite influence model (Thompson et al., 1999). In line with this, previous research has demonstrated that social comparison mediates the association between offline body talk and body dissatisfaction (Matera et al., 2013; Shroff & Thompson, 2006). Therefore, we expected that appearance comparison would mediate the association between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction.

The Role of Gender

Gender issue has always been an important topic in body image. Although body talk is regarded as a phenomenon among girls and women in the early stage of research (Nichter & Vuckovic, 1994) and has been linked to female body dissatisfaction in a wide range of research (see Mills & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, 2017, for a review), this kind of appearance-related interaction is also documented among boys and men (Chow & Tan, 2016; Engeln et al., 2013). The association between body talk and body dissatisfaction is also confirmed in men although the effect size is smaller for them than that for women (Sharpe et al., 2013).

Research focusing on the relationship between appearance ideals internalization and body dissatisfaction found that thin-ideal and muscular-ideal internalization were associated with body dissatisfaction for adolescent boys and girls (Jarman et al., 2021; Rodgers et al., 2020) as well as young men and women (Vartanian et al., 2018). A recent meta-analysis further showed that the relationship between the appearance ideals internalization and body dissatisfaction did not significantly differ across genders (Paterna et al., 2021). Most of the studies in this meta-analysis, however, were conducted by using Western samples. In the Chinese context, research on gender differences in the associations of different types of internalization with body dissatisfaction is scarce. A study focusing on Chinese college students revealed that most of the women preferred a slender figure, which was underweight and far smaller than the most attractive female figure chosen by men. For men who were dissatisfied with their body, 53.4% desired a slender figure and 46.6% wanted a fuller one (K. Wang et al., 2018). Extending from this research, it is reasonable to expect that the role of thin-ideal internalization in body dissatisfaction would be stronger for women than men, while the effect of muscular-ideal internalization on body dissatisfaction would be stronger for men than women in the present sample. Regarding the role of general attractiveness internalization, it was examined largely for exploratory purposes considering the limited research.

In terms of the relationship between appearance comparison and body dissatisfaction, it has been documented that appearance comparison has a positive association with body dissatisfaction among adolescents and young adults (Chen et al., 2007; van den Berg et al., 2007). A meta-analysis also showed that this relationship was confirmed for both genders with the effect size being smaller for men than that for women (Myers & Crowther, 2009). As for the mediating role of appearance comparison, research focusing on gender differences showed inconsistent findings. Some studies found that appearance comparison functioned as a mediator between sociocultural pressures and body dissatisfaction among women but not men (Chen et al., 2007; van den Berg et al., 2007). In contract, another study supported that comparisons on Facebook mediated the relationship between passive Facebook use and body dissatisfaction among boys but not girls (Rousseau et al., 2017). Considering these inconsistent findings, no specific prediction on gender differences in terms of the role of appearance comparison was made in the present study.

The Present Study

Taken together, the present study aimed to investigate: (1) whether SNS body talk is related to body dissatisfaction; (2) whether appearance ideals internalization (i.e., thin-ideal internalization, muscular-ideal internalization, and general attractiveness internalization) mediates the relation between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction; (3) whether appearance comparison mediates the relation between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction; (4) whether there are gender differences in the direct and indirect associations between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction mentioned above. Based on the tripartite influence model and literature review, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H1: SNS body talk would be positively linked to body dissatisfaction.

H2a: The positive link from SNS body talk to body dissatisfaction would be mediated by thin-ideal internalization,

H2b: The positive link from SNS body talk to body dissatisfaction would be mediated by muscular-ideal internalization.

H2c: The positive link from SNS body talk to body dissatisfaction would be mediated by general attractiveness internalization.

H3: The positive link from SNS body talk to body dissatisfaction would be mediated by appearance comparison.

H4a: Regarding gender differences, we predicted that the role of thin-ideal internalization in body dissatisfaction would be stronger for women than men.

H4b: The effect of muscular-ideal internalization on body dissatisfaction would be stronger for men than women.

The potential gender differences in other paths in the hypothesized model were examined largely for exploratory purposes. Taken together, the present study would provide a better understanding of how SNS use influence body image by examining the association between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction as well as the mediating mechanisms underlying this relationship.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited by means of convenience sampling from two universities in China. The research assistants contacted 4 teachers to collect data in their class and they agreed. The study was advertised as research on Internet use and mental health. Ethical approval was gained from the first author’s University Ethics Committee. The survey was administered in classrooms by trained research assistants. Participants were asked to complete a list of questions regarding demographic items, SNS body talk, appearance ideals internalization, appearance comparison, and body dissatisfaction and they were free to withdraw at any time. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection. Participants were voluntary to take part in the survey and they received no reward for the participation. A total of 480 students participated in the research and 4 students who were not able to complete the surveys were removed, which means the completion rate was 99.17%. These students major in electronic commerce, computer application technology, information management and animation production technology.

Data from 476 participants were analyzed in the present study. In the final sample, 280 were women (59%) and 196 were men. The participants’ ages ranged from 16 to 22, with an average age of 19.65 years (SD = 1.23). Based on the self-reported height and weight, body mass indices (BMI: kg/m2) ranged from 14.88 to 31.74 (M = 20.77, SD = 2.95).

Measures

SNS Body Talk

Following previous research (Y. Wang, Wang, et al., 2020), appearance conversations with friends scale (Jones et al., 2004) was slightly modified to measure SNS body talk. Adaptations were made by adding a description on SNS to the original items (see Appendix A). A representative item was: On SNS, my friends and I talk about the size and shape of our bodies. Participants responded to 5 items on 5-point response scale (1 = never to 5 = very frequently). Items were averaged with a higher score indicating the participants talk about their bodies on SNS more frequently. In this research, Cronbach’s α was .90 for men and .88 for women, respectively.

Appearance Ideals Internalization

Appearance ideals internalization was assessed using the subscales of (SATAQ-4R; Schaefer et al., 2017). Internalization of thinness, muscularity, and general attractiveness were measured using Internalization: Thin/Low Body Fat (IT), Internalization: Muscular (IM), and Internalization: General Attractiveness (IG) subscales, respectively (see Appendix B). Representative items were: I want my body to look very thin (IT); It is important for me to look muscular (IM); and I don’t really think much about my appearance (IG). Participants were asked to respond on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree). Items were averaged to form a total score with higher scores indicating higher levels of appearance ideals internalization. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alphas were acceptable for thin-ideal internalization (α = .70 for men and α = .74 for women), muscular-ideal internalization (α = .79 for men and α = .76 for women), and general attractiveness internalization (α = .77 for men and α = .74 for women).

Appearance Comparison

Appearance comparison was measured using the scale developed by Fardouly and Vartanian (2015). Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement to 3 statements (see Appendix C), such as: I compare my physical appearance to the physical appearance of others when using SNS. Participants responded on a 5-point scale (1 = definitely disagree, 5 = definitely agree). Items were averaged to form a total score with higher score indicating higher tendency to compare appearance in general on SNS. In this research, Cronbach’s α was .83 for men and .90 for women, respectively.

Body Dissatisfaction

Body dissatisfaction was assessed using Body Areas Satisfaction Scale (BASS), a subscale of Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ; Cash, 2000). Participants were asked to report their levels of satisfaction on nine items with aspects of one’s appearance and overall appearance (see Appendix D). The BASS used a 5-point response scale ranging from 1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied. Responses across the items were reversed and averaged, with higher scores representing higher levels of body dissatisfaction. In this research, Cronbach’s α was .89 for men and .88 for women, respectively.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated separately for men and women first, followed by bivariate associations among the variables of interest. Second, the mediation effects of appearance ideals internalization and appearance comparison in the relation between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction were tested using Model 4 of the PROCESS v3.4 macro (Hayes, 2013). Then, moderated mediation analysis was performed using Hayes’s (2013) PROCESS v3.4 macro for SPSS (Model 59) to test the role of gender in the mediation model. We calculated z-scores for each variable prior to the analyses to obtain standardized estimates (Aiken et al., 1991) given that the PROCESS macro does not report standardized estimates for moderated mediation models. This macro used the bootstrapping technique to test the significance of the direct and indirect effects by repeatedly sampling cases from the data and estimating the model in each resample. In the present study, we generated 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) on the basis of 1000 bootstrap samples to estimate the effects. CIs that did not include zero indicated that the effects were statistically significant.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for all variables are presented separately for men and women in Table 1. For men, SNS body talk was positively associated with thin-ideal internalization, general attractiveness internalization, appearance comparison, and body dissatisfaction. The relationship between SNS body talk and muscular-ideal internalization was not significant. Appearance comparison was positively associated with body dissatisfaction, while the associations of internalizations with body dissatisfaction were not significant. For women, SNS body talk was positively associated with thin-ideal internalization, muscular-ideal internalization, general attractiveness internalization, and appearance comparison. Thin-ideal internalization, general attractiveness internalization, and appearance comparison were significantly and positively related to body dissatisfaction, while the relationship between muscular-ideal internalization and body dissatisfaction was nonsignificant.

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for Study Variables.

|

Variables |

M (SD) |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

Women |

Men |

||||||||

|

1. BMI |

20.14 (2.60) |

21.68 (3.17) |

1 |

.13 |

−.10 |

.19** |

−.16* |

.09 |

.18* |

|

2. SNS body talk |

2.24 (0.75) |

2.15 (0.82) |

−.11 |

1 |

.13 |

.39** |

.23** |

.74** |

.14* |

|

3. Internalization (M) |

2.58 (0.67) |

3.29 (0.79) |

−.05 |

.20** |

1 |

.29** |

.64** |

.12 |

−.01 |

|

4. Internalization (T) |

3.24 (0.73) |

2.77 (0.75) |

.11 |

.14** |

.11 |

1 |

.37** |

.29** |

.10 |

|

5. Internalization (G) |

3.51 (0.58) |

3.34 (0.69) |

−.04 |

.24** |

.11 |

.63** |

1 |

.21** |

.08 |

|

6. Appearance comparison |

2.13 (0.81) |

2.14 (0.88) |

.01 |

.68** |

.24** |

.28** |

.32** |

1 |

.21** |

|

7. Body dissatisfaction |

2.91 (0.67) |

2.56 (0.68) |

.30** |

.09 |

.03 |

.27** |

.18** |

.15** |

1 |

|

Note. Internalization (M) = Muscular-ideal internalization, Internalization (T) = Thin-ideal internalization, Internalization (G) = General attractiveness internalization. Correlations for men and women are displayed above and below the diagonal, respectively. *p < .05. **p < .01. |

|||||||||

Testing for Mediation Effects

BMI had a significant association with body dissatisfaction, thus was entered as a covariate in the following analyses. Regression analysis showed that SNS body talk positively and significantly predicted body dissatisfaction, b = .13, t = 2.94, p = .003, which supported H1. To further investigate how SNS body talk was related to body dissatisfaction, we tested the mediating role of appearance ideals internalization and appearance comparison using multiple mediation analysis. As shown in Table 2, SNS body talk was significantly and positively related to thin-ideal internalization (Model 1), muscular-ideal internalization (Model 2), general attractiveness internalization (Model 3), and appearance comparison (Model 4). In Model 5, thin-ideal internalization was positively associated with body dissatisfaction significantly. Muscular-ideal internalization negatively predicted body dissatisfaction. The links from appearance comparison and general attractiveness internalization to body dissatisfaction were nonsignificant.

For the indirect effects, as presented in Table 3, the indirect effects of SNS body talk on body dissatisfaction through thin-ideal internalization and muscular-ideal internalization were significant. The mediating effects of general attractiveness internalization and appearance comparison in the association between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction were nonsignificant. Note, however, that the indirect effects had small effect size. Thus, the results of the mediation analysis should be interpreted with caution.

Table 2. Testing the Mediation Model.

|

Model |

DV |

IV |

b |

SE |

t |

p |

95% CI |

F |

R2 |

p |

|

Model 1 |

Internalization (T) |

SNS body talk |

.25 |

.04 |

5.57 |

< .001 |

[.17, .35] |

16.32 |

.06 |

< .001 |

|

Model 2 |

Internalization (M) |

SNS body talk |

.13 |

.05 |

2.86 |

.004 |

[.05, .24] |

4.50 |

.02 |

.011 |

|

Model 3 |

Internalization (G) |

SNS body talk |

.23 |

.04 |

5.32 |

< .001 |

[.01, .08] |

18.21 |

.07 |

< .001 |

|

Model 4 |

Appearance comparison |

SNS body talk |

.71 |

.03 |

21.83 |

< .001 |

[.69, .83] |

239.46 |

.50 |

< .001 |

|

Model 5 |

Body dissatisfaction |

SNS body talk |

−.01 |

.06 |

−0.11 |

.910 |

[−.13, .11] |

10.56 |

.12 |

< .001 |

|

Internalization (T) |

.17 |

.05 |

3.19 |

.002 |

[.06, .25] |

|||||

|

Internalization (M) |

−.16 |

.05 |

−3.37 |

< .001 |

[−.01, .18] |

|||||

|

Internalization (G) |

.10 |

.05 |

1.89 |

.061 |

[−.001, .24] |

|||||

|

Appearance comparison |

.12 |

.06 |

1.95 |

.053 |

[−.004, .21] |

|||||

|

Note. Internalization (T) = Thin-ideal internalization, Internalization (M) = Muscular-ideal internalization, Internalization (G) = General attractiveness internalization.

|

||||||||||

Table 3. Testing the Indirect Effects and Conditional Indirect Effects.

|

|

Indirect effect |

SE |

95% CI |

|

|

Mediation model (indirect effects) |

|

|

|

|

|

SNS body talk → Internalization (T) → body dissatisfaction |

.04 |

.02 |

[.01, .08] |

|

|

SNS body talk → Internalization (M) → body dissatisfaction |

−.02 |

.01 |

[−.04, −.003] |

|

|

SNS body talk → Internalization (G) → body dissatisfaction |

.02 |

.02 |

[−.01, .18] |

|

|

SNS body talk → Appearance comparison → body dissatisfaction |

.09 |

.05 |

[−.01, .18] |

|

|

Moderated mediation model (conditional indirect effects) |

|

|

|

|

|

SNS body talk → Internalization (T) → Body dissatisfaction (men) |

−.01 |

.03 |

[−.08, .06] |

|

|

SNS body talk → Internalization (T) → Body dissatisfaction (women) |

.03 |

.02 |

[.002, .08] |

|

|

SNS body talk → Internalization (M) → Body dissatisfaction (men) |

−.01 |

.02 |

[−.05, .02] |

|

|

SNS body talk → Internalization (M) → Body dissatisfaction (women) |

−.01 |

.01 |

[−.03, .03] |

|

|

SNS body talk → Internalization (G) → Body dissatisfaction (men) |

.03 |

.03 |

[−.01, .09] |

|

|

SNS body talk → Internalization (G) → Body dissatisfaction (women) |

.01 |

.02 |

[−.04, .06] |

|

|

SNS body talk → Appearance comparison → Body dissatisfaction (men) |

.15 |

.08 |

[−.001, .30] |

|

|

SNS body talk → Appearance comparison → Body dissatisfaction (women) |

.04 |

.06 |

[−.07, .15] |

|

|

Note. Internalization (T) = Thin-ideal internalization, Internalization (M) = Muscular-ideal internalization, Internalization (G) = General attractiveness internalization. |

||||

Testing for the Moderated Mediation Model

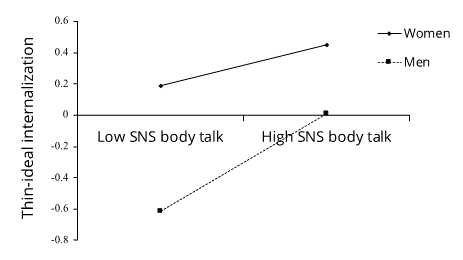

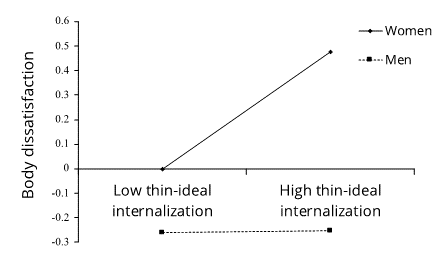

We tested the potential gender differences in the mediation model. Specifically, the moderating roles of gender in the direct and indirect associations between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction were examined. Results showed that two paths in the mediation model varied by gender. First, the path from SNS body talk to thin-ideal internalization was moderated by gender, b = .19, p = .028, 95% CI = [.020, .352]. As presented in Figure 1, simple slop analysis showed that the relationship was stronger among men, bsimple = .33, p < .001, 95% CI = [.209, .453], than women, bsimple = .15, p = .011, 95% CI = [.034, .257]. Second, the link from thin-ideal internalization to body dissatisfaction varied by gender, b = −.24, p = .029, 95% CI = [−.454, −.024]. As shown in Figure 2, thin-ideal internalization was significantly associated with body dissatisfaction only among women, bsimple = .22, p = .005, 95% CI = [.068, .371], not men, bsimple = −.02, p = .801, 95% CI = [−.175, .135]. No significant gender differences were found in other paths within the mediation model.

In terms of conditional indirect effects, as shown in Table 3, the indirect effect of thin-ideal internalization in the relationship between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction for men was nonsignificant. In contrast, the indirect effect of thin-ideal internalization for women was significant. Additionally, the indirect effects of muscular-ideal internalization, general attractiveness internalization, and appearance comparison were not significant for both men and women. Notably, the results of the moderated mediation analysis should be interpreted with caution given that the effect size of the indirect effects was small.

Figure 1. The Interaction Between SNS Body Talk and Gender on Thin-Ideal Internalization.

Figure 2. The Interaction Between Thin-Ideal Internalization and Gender on Body Dissatisfaction.

Discussion

Grounded in the tripartite influence model (Thompson et al., 1999), the present study provided a preliminary investigation of the association between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction among young men and women. Consistent with our hypothesis, SNS body talk was positively linked to body dissatisfaction. This finding is in accordance with previous research on the relationship between offline body talk and body dissatisfaction (Mills & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, 2017). SNS have become important platforms for interpersonal interactions and thus provide new forums for online body talk (Hummel & Smith, 2015; Walker et al., 2015). These appearance-related interactions on SNS remind people of the importance of physical appearance and socially reinforce the importance of beauty ideals (Tiggemann et al., 2018). As a result, it is not surprising to find that SNS body talk would have a positive association with body dissatisfaction. Additionally, this study offers a novel perspective to explore how SNS use affects individuals’ body image. Although the negative influence of SNS use on body image has been documented by numerous studies (see Fardouly & Vartanian, 2016, for a review), some scholars suggest that specific activities might be more strongly related to body image concerns compared with general SNS use (Kim & Chock, 2015; Meier & Gray, 2014). Based on this suggestion, our study examined the association between a specific activity (i.e., body talk) on SNS and body dissatisfaction, which extended literature on SNS use and body image. Given its novelty, more explorations are needed in future research to further clarify the relationship between SNS body talk and body image concerns.

Consistent with our hypothesis, thin-ideal internalization mediated the association between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction. Notably, gender differences emerged in this indirect effect that thin-ideal internalization functioned as a mediator for women while this indirect effect was not significant for men. This result indicated that SNS body talk could induce women to internalize the thin ideal (Mills & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, 2017), which in turn would increase their body dissatisfaction (Paterna et al., 2021). This finding is consistent with the proposition of the tripartite influence model (Thompson et al., 1999) and the empirical findings that sociocultural influences exerted their effects on women’s body dissatisfaction through thin-ideal internalization (e.g., Donovan et al., 2020; Ramme et al., 2016). For men the situation is different that sociocultural influences, such as SNS body talk in this study, could increase their internalization of low body fat, which in turn would lead to body fat dissatisfaction but might not be detrimental to their overall body dissatisfaction (Girard et al., 2018). This is because the male ideal is not clearly defined—at least much less clearly defined than female ideal (Buote et al., 2011), and male body attitudes are multidimensional (De Jesus et al., 2015; Tylka et al., 2005). For example, height is one of the major concerns regarding body image and even more important than weight concern for Chinese men (K. Wang et al., 2018).

Another interesting finding is that the path from SNS body talk to thin-ideal internalization was significantly stronger among men than women. This finding might be explained by the “drench effect”, which posits that an extraordinary, uncharacteristic, and sudden stimulus would have a heavier effect on individuals’ beliefs (Greenberg, 1988). In the current study, SNS body talk, especially talking about body fat, may be a more novel phenomenon for men compared with women. Thus, men would be more susceptible to the influence of SNS body talk. In other words, the same level of body talk may have a greater effect on thin-ideal internalization among men.

In terms of muscular-ideal internalization, our results showed that muscular-ideal internalization mediated the association between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction and no gender difference emerged in this indirect effect. This finding indicated that the indirect effect of muscular-ideal internalization in the relationship between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction is equivalent for men and women. It is common to engage in muscle talk when men talk about their physical appearance (Engeln et al., 2013), and this encouragement of muscular ideal would induce them to internalize this ideal and drive for muscularity (Stratton et al., 2015). In turn, male body satisfaction would be influenced, depending on whether the muscular ideal could be attained. Since research has found that women engage in muscle talk as frequently as men do (Lin et al., 2021), it is possible that such type of appearance conversation would also link to muscular-ideal internalization in women, which in turn would have an influence on female body dissatisfaction.

Surprisingly, muscular-ideal internalization was negatively related to body dissatisfaction, the direction of which is inconsistent with our prediction. The attainability of appearance ideals might provide somewhat explanation for this unexpected result. If an ideal is perceived attainable, it may serve to inspire individuals and motivate them to alter their behaviors, which in turn can generate positive outcomes (Lockwood & Kunda, 1997). Specific to appearance ideal, it has been documented that muscular development is considered as a more easily attainable feature than thinness and attractiveness (Buote et al., 2011; Paterna et al., 2021). Therefore, it is possible that individuals who internalized muscular-ideal could be inspired and motivated to alter their appearance and gain muscularity relatively easily by ways of working out, resulting in positive impact on body image. In line with this, a recent study found that muscular-ideal internalization was positively related to body satisfaction and well-being (Jarman et al., 2021). Additionally, it is also possible that there is a positive link from body satisfaction to muscular-ideal internalization. That is, individuals who are satisfied with their body usually have a fit/toned body and thus buy into a muscular ideal, although this needs to be confirmed using a longitudinal design. Hence, more follow-up research is necessary to figure out the relationship between muscular-ideal internalization and body dissatisfaction.

Regarding general attractiveness internalization, we did not find a mediating role in the association between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction, neither for women nor for men. Specifically, null finding was found for the path from general attractiveness internalization to body dissatisfaction. A possible explanation for the lack of this association might be traced back to the measures. Specifically, general attractiveness internalization reflects a more general desire for an attractive appearance (Schaefer et al., 2017) and for Chinese people facial appearance concern may be more culturally-salient than overall body dissatisfaction (T. Jackson & Chen, 2015). As a result, general attractiveness internalization had no mediating effect in the relationship between SNS body talk and overall body dissatisfaction. More explorations of different types of appearance ideals internalization and different dimensions of appearance dissatisfaction as well as their relationships among Chinese samples are needed in future research. Alternatively, sample size might interpret the null result to some extent. Thus, future research with larger sample size is needed to better understand this issue.

Lastly, our results showed that appearance comparison did not have a mediating effect as the association between appearance comparison and body dissatisfaction was not significant. This unexpected result might be explained by the following reasons. First, similar to the null result between general attractiveness internalization and body dissatisfaction, the sample size might somewhat influence the significance of the link between appearance comparison and body dissatisfaction. Another explanation for the lack of association between appearance comparison and body dissatisfaction might be that appearance comparison and appearance ideals internalization play a serial mediating role in the relationship between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction, as suggested by research examining and extending the tripartite influence model which found that appearance comparison has an indirect effect on body dissatisfaction through appearance ideals internalization (e.g., Halliwell & Harvey, 2006; Keery et al., 2004; Rodgers et al., 2011).

The present study has some contributions. Our findings showed that SNS body talk was associated with body dissatisfaction, which could contribute to our understanding of the relationship between SNS use and body dissatisfaction and provide a novel perspective to investigate the influence of SNS on body image in future research. Furthermore, our study examined the mediating roles of appearance ideals internalization and appearance comparison in the relationship between SNS body talk and body dissatisfaction, which might extend the tripartite influence model in the context of SNS body talk. The findings indicate that the final model was characterized by greater gender similarities than differences despite gender differences as found in some paths, i.e., the path from SNS body talk to thin-ideal internalization and the path from thin-ideal internalization to body dissatisfaction. From a practical perspective, the findings of the present study indicate that internalization of a unique appearance ideal plays a vital role in the development of body dissatisfaction. Policy makers should take measures to decrease individual’s internalization by reducing the propaganda of and emphasis on a specific physical appearance in the media. For example, various body types could be encouraged in the media to challenge the sociocultural normative body ideals, such as fat acceptance movement on social media (Webb et al., 2017).

Some limitations should be addressed in the present study. First, sample size in the present study, especially when analyzed separately for men and women, was small which might influence the significance of the results and the magnitudes of effect sizes. Thus, future research with larger sample size is needed to better understand this issue. In addition to the sample-size issue, the present study only focused on Chinese college students. Previous research has shown that age and culture differences emerged in body image (e.g., Bucchianeri et al., 2013; Stojcic et al., 2020), which might further influence the associations examined in the present study. Future research should replicate our findings in samples from diverse age groups or cultural backgrounds. Second, the design of this study was cross-sectional, therefore causal inference about both direct and mediating effects could not be determined. More longitudinal or experimental research is needed to examine the bidirectional or causal relationships. Third, data were collected based on self-report measures, which might affect the validity of this study. Other methods, such as content analysis, could be used to analyze SNS body talk in order to gain more insights. In addition, the present study focused on body talk with SNS friends, future research could distinguish body talk with close friends, body talk with online friends, or a more general SNS body talk because the influence of sociocultural pressures from varied sources and comparison to specific target groups (e.g., family members, close friends, and distant peer target groups) is different (Fardouly & Vartanian, 2015). Similarly, more specific scales to measure dissatisfaction of different dimensions of body image should be developed to provide more insights into research on body image concerns.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

This research was sponsored by the International Research Cooperation Seed Fund of Beijing University of Technology (No. 2021B30) and the Project funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020M680268). The authors thank Junli Wang, Xiaoxiao Yang, Yixin Jiang and Shiqing Song for assistance in data collection and thank Hongxia Wang for assistance in research design.

Appendix

Appendix A: SNS Body Talk

- My friends and I talk about how our bodies look in our clothes on SNS.

- My friends and I talk about what we would like our bodies to look like on SNS.

- My friends and I talk about how important it is to always look attractive on SNS.

- My friends and I talk about the size and shape of our bodies on SNS.

- My friends and I talk about what we can do to always look our best on SNS.

Appendix B: Appearance Ideals Internalization

- It is important for me to look muscular. M

- It is important for me to look good in the clothes I wear. G

- I want my body to look very thin. T

- I think a lot about looking muscular. M

- I think a lot about my appearance. G

- I think a lot about looking thin. T

- I want to be good looking. G

- I want my body to look muscular. M

- I don’t really think much about my appearance. G *

- I don’t want my body to look muscular. M *

- I want my body to look very lean. T

- It is important to me to be attractive. G

- I think a lot about having very little body fat. T

- I don’t think much about how I look. G *

- I would like to have a body that looks very muscular. M

Note. M = internalization: muscularity; T = internalization: thin/low body fat; G = internalization: general attractiveness; * = item reversed.

Appendix C: Appearance Comparison

1 When using SNS, I compare my physical appearance to the physical appearance of others.

2 When using SNS, I compare how I am dressed to how other people are dressed.

3 When using SNS, I sometimes compare my figure to the figures of other people.

Appendix D: Body Dissatisfaction

Dissatisfaction-satisfaction with discrete aspects of one’s appearance (i.e., face, hair, lower torso, mid torso, upper torso, muscle tone, weight and height) and overall appearance.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2022 Yuhui Wang, Jingyu Geng, Ke Di, Xiaoyuan Chu, and Li Lei.