The selfie production model: Rethinking selfie taking, editing, and posting practices

Vol.15,No.4(2021)

With the rise of digital technologies, selfies are a contemporary and popular form of digitally produced self-expression for Saudi women. Informed by Goffman’s (1959) self-presentation theory and Hall’s (1966) proxemics theory, this study explores the process of producing and posting selfies on Instagram and Snapchat platforms, and examines how these practices are shaped by cultural norms and platform affordances. Methodologically, an ethnographic approach was employed to observe selfie practices involving: focus groups, face-to-face interviews, online observation, and photo-elicitation interviews. The sample consisted of 35 Saudi women between 18-57 years old. The results were used to develop a framework for understanding selfie production consisting of six processes: the motivation process, pre-photo process, platform affordances process, audience customization process, assessment of cultural norms process, and the process of reposting selfie. Also, the study identified a number of strategies practiced by Saudi women to present a more desirable self, including: digitally editing the selfie using beautifying filters, arranging the background, retaking the selfie, and adding digital makeup. Cultural norms were found to heavily influence selfie practices, as selfie takers carefully select particular audiences with whom to share the selfie, while blocking others from viewing the selfie using “virtual walls” depending on veiling practices, habitual proximity, and the appropriateness of the content. The model and the identified strategies make an important empirical contribution that provides a new way of thinking about selfie practices outside Euromerica.

selfie; women; platform affordances; self-presentation; culture; Saudi Arabia; Snapchat; Instagram; selfie model

Afnan Qutub

King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Dr. Afnan Qutub is an assistant professor in Digital Media at King Abdulaziz University in Saudi Arabia. She graduated with a PhD degree in Philosophy from Leicester University, United Kingdom. She completed an M.A. degree in Communication Studies from California State University, Los Angeles. Her research interests include media representation, critical and cultural studies, feminist media studies, and internet studies. She published a number of works. A previous essay of hers, entitled “The presentation of Muslim women in the media: Saving Muslim women from their misery” was published in 2017 of GRIN Verlag. A recent study titled “Saudi women’s motives of using nick names in online spaces” was published in July 2020 by the Media and Communication Journal of the University of Cairo. She co-authored a book titled "New media and Public Relations theories: Practices and application" in 2021.

Alghadir, A. H., Aly, F., & Zafar, H. (2012). Effect of face veil on ventilator function among Saudi adult females. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 28(1), 71–74. http://pjms.com.pk/index.php/pjms/article/view/1472

Al-Harbi, A. (2018, February 27). Amazing numbers of Snapchat users. Saudi Gazette. http://saudigazette.com.sa/article/529276/Opinion/Local-Viewpoint/Amazing-number-of-SnapChat-users

Al-Kandari, A. A., & Abdelaziz, Y. A. (2018). Selfie-taking motives and social psychological dispositions as predictors of selfie-related activities among university students in Kuwait. Mobile Media & Communication, 6(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157917737124

Alsaggaf, R. M. (2015) Identity construction and social capital: A qualitative study of the use of Facebook by Saudi women [Doctoral dissertation, University of Leicester]. https://hdl.handle.net/2381/35977

Al-Saggaf, Y. (2011). Saudi females on Facebook: An ethnographic study. International Journal of Emerging Technologies and Society, 9(1), 1–19.

Al-Senaidy, A. M., Ahmad, T., & Shafi, M. M. (2012). Privacy and security concerns in SNS: A Saudi Arabian users point of view. International Journal of Computer Applications, 49(14). https://doi.org/10.5120/7692-1014

Ardévol, E., & Gómez-Cruz, E. (2012). Private body, public image: Self-portrait in the practice of digital photography. Revista de Dialectologia y Tradiciones Populares, 67(1), 181–208. https://doi.org/10.3989/RDTP.2012.07

Boden, D., & Molotch, H. L. (1994). The compulsion of proximity. In R. Friedland & D. Boden (Eds.), Nowhere: Space, time and modernity (pp. 257–286). University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520342095-009

Browne, K. (2005). Snowball sampling: Using social networks to research non‐heterosexual women. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000081663

Carbon, C.-C. (2017). Universal principles of depicting oneself across the centuries: From renaissance self-portraits to selfie-photographs. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 245. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00245

Chae, J. (2017). Virtual makeover: Selfie-taking and social media use increase selfie-editing frequency through social comparison. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 370–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.007

Chua, T. H. H., & Chang. L. (2016). Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 55(Part A), 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.011

Cohen, R., Newton-John, T., & Slater, A. (2017). ‘Selfie’-objectification: The role of selfies in self-objectification and disordered eating in young women. Computers in Human Behavior, 79, 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.027

Costa, E. (2018). Affordances-in-practice: An ethnographic critique of social media logic and context collapse. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3641–3656. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818756290

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

Davis, C., Powell, H., & Lachlan, K. (2013). Straight talk about communication research methods. Kendall Hunt Publishing Company.

Dhir, A., Torsheim, T., Pallesen, S., & Andreassen, C. S. (2017). Do online privacy concerns predict selfie behavior among adolescents, young adults and adults? Frontiers in Psychology. 8, Article 815. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00815

Etgar, S., & Amichai-Hamburger, Y. (2017). Not all selfies took alike: Distinct selfie motivations are related to different personality characteristics. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 842. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00842

Fatanti, M. N., & Suyadnya, I. W. (2015). Beyond user gaze: How Instagram creates tourism destination brand? Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 211, 1089–1095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.145

Fox, J., & Rooney, M. C. (2015). The dark triad and trait self-objectification as predictors of men’s use and self-presentation behaviors on social networking sites. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 161–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.017

Garcia A. C., Standlee A. I., Bechkoff J., Cui Y. (2009). Ethnographic approaches to the Internet and computer-mediated communication. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 38(1), 52–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241607310839

Gibbs, M., Meese, J., Arnold, M., Nansen. B., & Carter, M. (2014). #Funeral and Instagram: Death, social media, and platform vernacular. Information, Communication & Society, 18(3), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.987152

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday Anchor Books.

Griffin, E. (2012). A first look at communication theory. McGraw Hill.

Guta, H., & Karolak, M. (2015). Veiling and blogging: Social media as sites of identity negotiation and expression among Saudi women. Journal of International Women's Studies, 16(2), 115–127. http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol16/iss2/7

Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension. Anchor Books.

Jailanee, F., Malhotra, P., & Ling, R. (2019). R(e)-veiling the hijab: Social media, Islamic fashion, and religious identity in Singapore [ Paper presentation]. The 69th Annual International Communication Association Conference, Washington, D. C.

Joffe, H. (2012). Thematic analysis. In D. Harper, & A. R. Thompson (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: A guide for students and practitioners (pp. 209–221). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119973249.ch15

Keller, J. (2016). Girls’ feminist blogging in a postfeminist age. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315755632

Kim, E., Lee, J.-A., Sung, Y., & Choi, S. M. (2016). Predicting selfie-posting behavior on social networking sites: An extension of theory of planned behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.078

Kozinets, R., Gretzel, U., & Dinhopl, A. (2017). Self in art/Self as art: Museum selfies as identity work. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 731. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00731

Kurniawati, J., Ahimsa-Putra, H. S., Irawanto, B., & Noviani, R. (2019). Selfie objectification: Representation of hijabed women in Instagram. In KnE Social Sciences (pp. 166–180). http://dx.doi.org/10.18502/kss.v3i20.4934

Laird, S. (2013, November 13). Behold the first ‘selfie’ hashtag in Instagram history. Mashable. http://mashable.com/2013/11/19/first-selfie-hashtag-instagram/

Le Renard, A. (2008). "Only for women:" women, the state, and reform in Saudi Arabia. The Middle East Journal, 62(4), 610–629. https://doi.org/10.3751/62.4.13

Lofland, J., & Lofland, L. (1995). Analyzing social setting: A guide to qualitative observation and analyzing. Wadsworth.

Marwick, A., & boyd. D. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810365313

Maxwell, J. (1996). Qualitative research design: An interpretative approach. Sage.

McLean, S. A., Paxton, S. J., Wertheim, E. H., & Masters, J. (2015). Photoshopping the selfie: Self photo editing and photo investment are associated with body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(8), 1132–1140. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22449

Meyrowitz, J. W. (1997). The separation of social space from physical space. In T. O’Sullivan & Y. Jewkes (Eds.), The media study reader (pp. 45–52). Edward Arnold.

Miclot, S. (2015). The selfie phenomena. [Doctoral dissertation, Colorado Technical University].

Monteiro, S. (2020). ‘Welcome to selfiestan’: Identity and the networked gaze in Indian mobile media. Media, Culture & Society, 42(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719846610

Nemer, D., & Freeman, G. (2015). Empowering the marginalized: Rethinking selfies in the slums of Brazil. International Journal of Communication, 9, 1832–1847. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/3155/1403

Pearce, W., Ozkula, S. M., Greene, A. K., Teeling, L., Bansard, J. S., Omena, J. J., & Rabello, E. T. (2020). Visual cross-platform analysis: Digital methods to research social media images. Information, Communication & Society, 23(2), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1486871

Piwek, L., & Joinson, A. (2016). “What do they snapchat about?” Patterns of use in time-limited instant messaging service. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 358–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.026

Pogjed, D. (2015). Online proxemics. Systema: Connecting Matter, Life, Culture, and Technology, 3(1), 105–118.

Rettberg, J. (2014). Seeing ourselves through technology: How we use selfies, blogs, and wearable devices to see and shape ourselves. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137476661

Rose, G. (2012). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. Sage.

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

Senft, T. M., & Baym, N. K. (2015). What does the selfie say? Investigating a global phenomenon. International Journal of Communication, 9, 1588–1606. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/4067/1387

Shipley, J. W. (2015). Selfie love: Public lives in an era of celebrity pleasure, violence, and social media. American Anthropologist, 117(2), 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.12247

Simon, S. (1996) Gender in translation: Cultural identity and the politics of transmission. Routledge.

Smith, L. R., & Sanderson, J. (2015). I'm going to Instagram it! An analysis of athlete self-presentation on Instagram. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(2), 342–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2015.1029125

Souza, F., de las Casas, D., Flores, V., Youn, S., Cha, M., Quercia, D., & Almeida, V. (2015). Dawn of the selfie era: The whos, wheres, and hows of selfies on Instagram [Paper presentation]. ACM Conference on Online Social Networks 2015, Stanford University, California, USA.Strauss, A., & Corbin. J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage. https://doi.org/10.1145/2817946.2817948

Temple, B., & Young, A. (2004). Qualitative research and translation dilemmas. Qualitative Research, 4(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794104044430

Thumim, N. (2015). Self-representation and digital culture. Palgrave Macmillan.

Tracy, S. (2013). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. Willey-Blackwell.

Vaterlaus, J. M., Barnett, K., Roche, C., & Young, J. A. (2016). “Snapchat is more personal”: An exploratory study on Snapchat behaviors and young adult interpersonal relationships. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 594–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.029

Vitak, J. (2012). The impact of context collapse and privacy on social network site disclosures. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(4), 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2012.732140

Wright, T. (2016). The photography handbook. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315651200

Yang, Q., & Li, Z. (2014). A picture is worth a thousand words: Chinese college students' self-presentation on social networking sites. Journal of Communications Media Studies, 6(1), 70–94.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

August 5, 2020

Revisions received:

June 17, 2021

July 31, 2021

August 11, 2021

Accepted for publication:

August 12, 2021

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

A selfie is an informal photograph of oneself usually taken using a mobile phone and posted on social networking sites (SNS) (Rettberg, 2014). Selfie-taking is a practice and a gesture that signals different messages to different individuals and audiences (Senft & Baym, 2015). For instance, while a number of researchers perceive selfies as evidence of narcissism (Fox & Rooney, 2015), other studies observe selfies as a tool for self-documentation (Ardévol & Gómez-Cruz, 2012). In addition, selfie practice is identified as a social practice, as a cultural artifact, as an advertising tool (Senft & Baym), and as an empowerment tool (Nemer & Freeman, 2015). Most of the empirical work on selfies has been carried out within Western cultures.

Among the Saudis, there are many restrictions related to women’s public self-expression (Le Renard, 2008). Indeed, Saudi women are encouraged to use a face covering or niqab in public (Alghadir et al., 2012). The niqab is a cultural norm and a social obligation in Saudi Arabia. However, posting selfies has recently become a trend among Saudi women, which challenges this tradition, albeit in a digital space. Taking into account both the cultural norms of Saudi society and the trends on popular SNS, this study attempts to reflect on Saudi women’s selfie taking, editing, and posting practices.

Previous research has discussed the photo sharing strategies of Saudi women on social media platforms (Al-Saggaf, 2011; Al-Senaidy et al., 2012; Guta & Karolak, 2015), yet these studies have not identified the process and platforms that might influence and/or shape women’s decisions to post self-expressive images. Furthermore, previous studies were conducted on older platforms such as Facebook (Al-Saggaf, 2011), which have become less popular over time and have been largely eclipsed by platforms such as Instagram and Snapchat. Most importantly, the earlier literature does not explicate the processes of taking, editing, and posting selfies. Given the above limitations, the current study examines the process of selfie production through examining selfies posted by Saudi women on Instagram and Snapchat, taking into account cultural and technological factors. The technological factors include using digital enhancing effects and choosing who has access to the selfie.

Theoretical Framework

This study was guided by Goffman’s (1959) self-presentation theory, Hall’s (1966) proxemics theory, the concept of platform affordances (Costa, 2018), and platform vernacular (Gibbs et al., 2014) to explain selfie practices. Goffman’s (1959) self-presentation theory was reframed to explain variations in selfie performances shared with multiple audiences on two separate platforms. His dramaturgical analysis can help us see how selfie producers present variations on appearances, clothes, face filters, and veils, when sharing the image with an Instagram audience, a Snapchat audience for the public story, and the private snap viewers.

Goffman’s (1959) dramaturgical model presents the world as a stage in which people’s performances vary depending on the situation and audience. In his view, self-presentation is centered on playing to the audience to meet their expectations. His term “front stage” refers to an individual’s performance in a public setting that requires impression management strategies like applying makeup or costumes. On the other hand, “back stage” behavior occurs in a private environment where individuals feel more relaxed. While Goffman focused on the individual’s appearance and behaviors as display in front of an audience, Hall (1966) focused on boundaries and territorial spaces, which, for the purposes of this study, were termed “virtual walls.” The virtual walls determine who can access the public story selfie, the private snap selfie, or the Instagram selfie—and who is to be blocked or rejected.

In sum, the contrasting concepts of front stage and back stage selves point to Goffman’s focus on the characteristics and content displayed when responding to and communicating with an audience, in this case, selfie viewers. The idea of “virtual walls” reflects Hall’s (1966) concern with self-boundary formation, which likens online spaces to a protective bubble surrounding the selfie producer.

The Audience and Selfie

Goffman’s dramaturgical theory asserted that a major motive for self-presentation is centered on playing to the audience (Goffman, 1959). Individuals often adjust their self-presentation strategies according to their environments and who they think is observing them. This includes trying to make a good impression to manipulate the audience. More often than not, Saudi social media users will adjust their behavior to the “preferences and expectations of the audience” (Alsaggaf, 2015, p. 206). Relating selfie sharing to Goffman’s theatrical performance, it is possible that those who share selfies are performing to present a more desirable self in virtual spaces.

Although Goffman’s ideas of the social self as distinct from the real self originally discussed self-presentation in face-to-face contexts, later scholars extended his theory to computer-mediated communication (Boden & Molotch, 1994; Meyrowitz, 1997; Smith & Sanderson, 2015; Thumim, 2015). According to Miclot (2015), Goffman’s theory has created a foundation for exploring the virtual self in a selfie as well as the real physical self. Goffman suggested that people’s social self-presentation emerges from a theatrical perspective; today, social media users are more aware of their image on SNS and invest more time into adding their realities to the shared image. In particular, Saudi social media users were found to construct their online identities on Facebook in terms of both the imagined audience and audience segregations in order to meet cultural norms (Alsaggaf, 2015). Accordingly, it is expected that Saudi selfie producers will manage and divide online audiences when sharing selfies to suit the cultural norms and audiences’ expectations using virtual walls.

Previous studies (Chua & Chang, 2016; McLean et al., 2015) have confirmed that women’s use selfie of editing strategies—including adding text, captions, emojis, or adjusting the brightness of the selfie—is significant in extending Goffman’s twin concepts of front stage and back stage performance. While people are cautious of the self they present for the front stage, a more relaxed self is constructed for the back stage (Goffman, 1959). It is possible to extend the concepts of front stage and back stage performances to selfie practices. For instance, a veiled selfie that is posted on Instagram where followers of both genders view the account could represent a front stage as a space. Conversely, an unveiled selfie might be shared with a small group of girlfriends on Snapchat could represent a backstage performance. Further, the selfie produced after a series of technological enhancements and additions could also constitute the construction of a front stage performance. While dramaturgical theory helps explain human interaction as influenced by the presence of an audience, proxemic theory sheds light on boundary formation based on physical space

Proxemic Theory

Hall introduced proxemic theory in 1966. Hall (1966) argued that humans are territorial and that they utilize fences, walls, furniture, and gardens to mark their spaces (Griffin, 2012). Although this theory of nonverbal communication tends to explain how individuals perceive and use physical space, the principles of proxemics may be applied to online communications and selfie behaviors (Dhir et al., 2017). In particular, the practice of allowing particular users to access one’s photo while blocking others could be understood as digital markers of territory.

In Hall’s view, there are four types of spatial zones associated with the types of interpersonal relationships: the intimate zone, the personal zone, the social zone, and the public zone. Hall (1966) categorized the four zones based on the inches between people in physical space. In online communications, proxemics may be determined by the habitual proximity, which is the level of closeness felt based on previous experiences of physical space, such as getting closer to individuals whom we already know (Pogjed, 2015). In this study, the level of closeness between users is based on intimacy and not on other factors. On social occasions in offline settings, there are separate spaces for women and men; on these occasions young adults would generally gather and sit next to each other away from mothers and older women. In the current research, the concept of “virtual walls” is used to describe how Saudi women mark their spaces when using Instagram and Snapchat to share selfies—to keep different audiences apart based on gender and age factors. The amount of communication with others and the sharing of personal versus non-personal content may also indicate online proximity. Additionally, people can use virtual walls to decide who belongs to their various circles (e.g., who do they follow on Instagram or view on Snapchat).

Given the gender segregation that takes place in offline environments in Saudi society, those gender boundaries are transferred to online spaces is unsurprising. For example, it is expected that a Saudi woman who takes a group selfie with her girlfriends is likely to post it as a private message instead of a public post, so that men who are unrelated to her girlfriends would not be able to view the selfie. All in all, Hall’s (1966) proxemics theory provides a general framework that requires further investigation before applying its principles to cultures with different internal divisions. For instance, it is essential to consider gender segregation in relation to proxemics: both concepts are closely interwoven in Saudi culture.

Selfie and Platform Vernacular

The platform vernacular refers to how the architecture and design of a platform influence the content produced, the process of interacting with content, and the communication habits of the users (Gibbs et al., 2014). Platform vernaculars are strongly informed by the affordances of the platform (Pearce et al., 2020). For instance, the anonymous nature of Tumblr’s audience allows feminists to address sensitive issues such as activism and rape, which could be judged negatively if seen by a Facebook community that includes family members and friends (Keller, 2016). Thus, this study explored Instagram and Snapchat affordances that informed the production, editing, and sharing of selfies. Snapchat and Instagram vary in a number of affordances, such as viewing time, controlling and customizing viewers, available selfie filters, the option of adding comments and “likes” to selfies, privacy settings, notifications of viewers’ screenshot of a selfie, and the option of creating and using a Bitmoji avatar with a selfie.

Previous studies have examined selfie behaviors on both platforms. Kim et al. (2016) and Laird (2013) confirmed that photo sharing and posting is a popular activity on Instagram. Even though selfie taking and sharing are now very common on Snapchat (Piwek & Joinson, 2016), Instagram is still one of the leading platforms for the selfie phenomenon (Souza et al., 2015).

Snapchat includes features from multiple digital communications, like the ability to post to a mass audience (as in Facebook), the ability to send private instant messages (as in SMS Text messaging), the ability to send audio and visual content to private individuals or groups (as in WhatsApp). Additionally, Snapchat allows users to share timed images and to control the viewing time (Piwek & Joinson, 2016). Other features, like adding selfie filters, adding location and time filters, and writing on the snapped image, are exclusive to the Snapchat application compared to other apps like WhatsApp, Twitter, etc. Snapchat is typically used for small networks and close relationships (Piwek & Joinson, 2016; Vaterlaus et al., 2016); conversely, Facebook is generally associated with large networks (Vitak, 2012). All in all, the hybrid image-text nature of Snapchat might lead to escalating selfie posting and sharing.

Many reasons make Snapchat particularly desirable for Saudi women. The privacy and affordances of Snapchat, such as allowing the receiver to see the image for a particular duration, in addition to notifying the sender if the picture is viewed by the receiver (Piwek & Joinson, 2016), would suggest that Saudi women’s selfie sharing would increase given their cultural normative context. Other control and privacy features provided by and exclusive to Snapchat include the disappearance of the image after 24 hours. Additionally, Snapchat offer the ability to send public and private selfies easily, and the ability to know which snapper took a screenshot of the selfie. These features may predict why selfies may become popular on Snapchat among Saudi women; indeed, Al-Harbi (2018) confirmed that out of the 9,000,000 Saudi Snapchat users, 55% are female.

With these digital affordances in mind, the current study attempts to understand how Saudi women post and share their selfies on Instagram and Snapchat and the cultural codes that influence their choices.

Online Image Sharing in Saudi Culture

Saudi women hold differing opinions about sharing their photos online, according to Al-Saggaf’s (2011) ethnographic study. Previous studies of Saudi women identified three categories which describe Saudi women’s photo sharing on social media. The first category includes women who share current photos and real information when representing themselves online, but their profile is set to not be seen by the public (Al-Senaidy et al., 2012). The second category consists of Saudi women who use childhood pictures to represent themselves rather than pictures of themselves as adults. The third category includes women who post a random picture from the internet instead of using a personal photo (Guta & Karolak, 2015).

These categories suggest that while some tend to present a front stage performance, as in the first groups, others prefer to present a back stage performance when sharing their photos online

Most importantly, Guta and Karolak’s (2015) study explored the parallels between social rules in Saudi culture and women’s experience of building profiles on SNS. With that in mind, the current study explores how cultural codes may inform the process of producing, editing, and sharing selfies with online viewers. Further, researchers investigating how social media influence the choices of Muslim women in Singapore about the wearing of the hijab and veiling found that social media could expand the choices of Muslim women by offering them multiple representations of veiling and hijab styles; it also has a constraining effect as it exposes them to others’ criticism (Jailanee et al., 2019).

As these studies indicate, the diversity of female Saudi user practices in terms of communicating their identity could be perceived in multiple aspects, such as the publicity of the profile, the number of accounts on a platform, the appearance of the female user (e.g., veiled vs. unveiled), the selection of the name used on the profile, and the audience accessing the account.

Method

This qualitative study used an ethnographic approach to explore participants’ habits and experiences of selfie posting. A combination of qualitative data collection methods was used to examine the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: How do platform affordances inform selfie production?

RQ2: How do cultural factors play a role in presenting oneself through selfies?

The purpose of ethnography is to describe and explain the behaviors of a particular socio-cultural group. This study attempts to understand women’s selfie behaviors in the Saudi cultural context, which is in part defined by cultural norms such as veiling, gender segregation, and religious beliefs. Ethnography focuses on shared and collective meanings and beliefs constructed by a group of people within a particular space (Creswell, 2013). This study used an ethnographic approach as it was intended to study people in their everyday lives. Most importantly, ethnography allows one to understand a particular context within which participants act, in addition to understanding the influence of this context on participants’ actions (Maxwell, 1996). Researchers have pointed out that using an online setting as a shortcut to data collection is one of the ethical issues involved with cyber research (Garcia et al., 2009). To avoid this pitfall, the current study collected data from offline settings, such as face-to-face interviews and focus groups, followed by an online observation.

In the current ethnography, the researcher observed and analyzed the selfies posted by Saudi women in online spaces, discussed the meaning of selfie practices with two focus groups, and listened to personal examples and cases of selfie posting during face-to-face interviews with 25 selfie takers. As the overall goal of the ethnography was to collect the richest possible data (J. Lofland & L. Lofland, 1995), the study was designed to observe how selfie practices took place online and how Saudi women talked about the selfie experience collectively and individually. These data collection methods were challenging in terms of the time required, and the complexity of asking for permission to access personal photos in a conservative culture (i.e., Saudi Arabia). However, this approach allowed the researcher to notice how the details of daily practices of selfie taking and sharing are formed in relation to cultural codes. Considering the sensitivity of the collected data, which included personal photos, network sampling was used to recruit participants. The study obtained approval from the Ethical Approval Board at the University of Leicester and participants signed a consent form to give permission to access their photos.

Sampling

This study used a combination of network sampling and snowball sampling procedures. Network sampling is a sampling method that uses social, workplace, or community networks for locating and recruiting the study participants (Davis et al., 2013). Snowball sampling is a type of sample in which a researcher identifies study participants who fit the criteria of the study, asks them to make referrals for other participants who in turn suggest other participants and so on (Tracy, 2013). Network and snowball sampling are useful when researching sensitive matters (Browne, 2005). Where this study is concerned, it would be expected that Saudi women would refuse to participate in the study when approached by a stranger asking for access to their personal photos.

The rationale for adopting these types of sampling was the cultural sensitivity that exists regarding the viewing and sharing of photos taken by and of Saudi women. Participants are more likely to trust the researcher and to participate in the research when introduced to the project by someone familiar (the researcher’s female acquaintances in this case) or someone who has already participated in the project.

This study had very specific sample requirements: Saudi women who have Instagram or Snapchat accounts on which they regularly (at least three per week) post selfies and who are willing to allow the researcher to access these accounts. Therefore, networking sampling was appropriate to approach such a narrow selection of participants. Hence, the researcher’s personal networks, including relatives, co-workers, friends, reading club members, and self-development trainees, used their connections and positions to recruit participants. The snowball sampling was used for a secondary sampling in which initial recruits were used to recruit further participants. Only two participants were approached and interviewed using snowball sampling. Thus, network sampling was a more useful strategy as Saudi women were more willing to participate when approached by someone they know and trust rather than a participant who took a part in a research project and suggest participating in the study. In terms of anonymity, the original names were changed to maintain the anonymity of participants.

All participants had private accounts on Instagram and Snapchat and posted selfies either veiled or non-veiled. Participants wore a headscarf and modest clothing in the veiled selfie while none of the participants wore the niqab in the study. The majority of participants were between 18-35 years old as users within this age range tend to take selfies more than younger or older groups.

Interviews

There were two rounds of interviews: face-to-face interviews and photo-elicitation interviews. The face-to-face interviews were conducted with 25 Saudi women, aged between 18 and 57 years, who had Instagram/Snapchat accounts, and who regularly posted selfies to them. During the first round of interviews, participants were introduced to the research topic and signed a consent form allowing the researcher to access their photos. It took about six months to recruit the sample and complete the face-to-face interviews.

Secondly, the photo-elicitation interviews aimed to explore participants’ personal impressions about their selfies. The photo-elicitation interviews were conducted after the researcher observed the selfies posted online. Photo-elicitation is a visual method designed to analyze photography, and it is based on the idea of incorporating photos into research interviews (Rose, 2012). It is a useful method when aiming to understand how participants perceive their sense of self or to examine the meaning of their behavior (Wright, 2016).

In the photo-elicitation interviews, participants were asked to describe how their selfies relate to social codes and how they met viewers’ expectations. This interview was designed to give participants the chance to comment on aspects that were significant to them, including appearance, cultural values, technical features, and/or the people in their selfies.

The open-ended questions include: “Describe how each of those selfies represents your virtual self and your real self within your culture”, “What are you communicating to the members of your virtual communities in these selfies and why?”, “Based on your selfies, how do you think people perceive you?”, and “If you were to delete a certain selfie from your profile, which one would it be and why?”. As was the case with the focus groups, the interviews were conducted in Arabic, transcribed, and then translated into English.

Online Observation

The online observation was conducted after the face-to-face interviews and was later followed by a photo-elicitation interview. The observation included collecting relevant data like selfies posted on Snapchat and Instagram accounts. During online observations, the researcher focused on the following elements in selfies posted by participants: users’ profile biographies, events, Instagram/Snapchat filters, collaged images, caption and image integration, facial expressions, context, number of friends (followers), number of followers, comments on a selfie, number of likes on a selfie, participants’ response to comments and likes on their selfie, indications of family and social life, appearance in selfies, and the use of face filters. A total of 340 selfies posted in 2018 were collected from 23 participants’ accounts on Snapchat and Instagram. The collected selfies were posted on the participants’ accounts and the researcher could access them; selfies shared through private messages could not be accessed. The online observation lasted for eight months.

Although the face-to-face interviews were conducted with 25 participants, two participants were excluded from the online observation for failing to post enough selfies during the observation period or for not accepting the researcher’s friend request, which prevented me from accessing their account.

Focus Groups

The two focus groups each lasted approximately 40–60 minutes. The researcher collected the focus group data within three weeks. In line with the ethics protocol of the University of Leicester, all participants signed an informed consent form before taking part. The researcher planned a discussion guide in advance and that shaped the conversation. As Tracy (2013) advised, having a discussion guide helps the researcher to address topics naturally as they arise during the focus group discussion. Although there was a discussion guide, participants were given the opportunity to lead the discussion during the focus groups, to expand on important relevant issues, and to talk about examples and stories related to their selfie posting experience.

The focus group discussions mainly concentrated on the following matters: the experience and motivations behind selfie taking and sharing on SNS, selfie posting on Snapchat and Instagram platforms, and the cultural factors involved in presenting oneself through selfies. The first focus group included four participants, while the second group consisted of six participants. The ten participants in the two focus groups were recruited via the same sampling as women for interviews, but the participants in focus groups and interviews did not overlap. The objective of the group discussions was to learn about popular selfie posting platforms and trends, as well as to understand to what extent Saudi women shape this experience in relation to cultural norms. The group discussions used open-ended questions like “what motivates you to take a selfie?”, “which platform do you use to share selfies?”, “how do cultural factors play a role in presenting oneself through selfies?”, “which social media do you prefer to take and share selfies?”, “what do you like about this particular platform?”, and “why do you share your selfies with others on social media?”.

This study conducted multiple forms of data collection to enhance the validity of the results. The focus group identified general beliefs, feelings, and behaviours related to selfie posting. The in-depth interview emphasised participants’ preferences, narratives, intentions, and knowledge related to selfie posting. The observation provided visual data and insights on selfie activities, as they happened on SNS, such as face filters and enhancing effects added to selfie. Finally, photo-elicitation interviews helped in understanding participants’ reflections and in enhancing the validity of the data.

Coding

The data was analyzed using three levels of coding: (1) developing a coding frame, (2) creating conceptual categories, and (3) developing themes. Firstly, all the data was examined, including interview transcripts, field notes, selfie images, participants’ reflections and reactions, to develop a coding frame. This process was conducted using manual coding, in which each code is named, defined, and assigned to text and image from the data. Joffe (2012) stated that this is an essential step in conducting thematic analysis.

Secondly, similar codes were grouped, which were developed at the first level, into conceptual categories. A category is a higher level of coding in which concepts are grouped together (Strauss & Corbin, 1990, p. 61). Thirdly, major themes were identified relying on the categories developed in the previous step. A theme is an extended phrase that recognises what a set of data means. Themes can include many forms of ideas, such as participant narrative, description of behaviour, iconic statement, and explanation of a phenomenon (Saldaña, 2016). Themes may contain manifest content that can be directly observed, and latent content such as indirect references in transcripts. Deductive themes are drawn from earlier theories, whereas inductive themes are generated from raw data (Joffe, 2012, p. 210). The researcher used a dual deductive-inductive and manifest-latent set of themes to understand the selfie phenomenon and construct the model.

Results

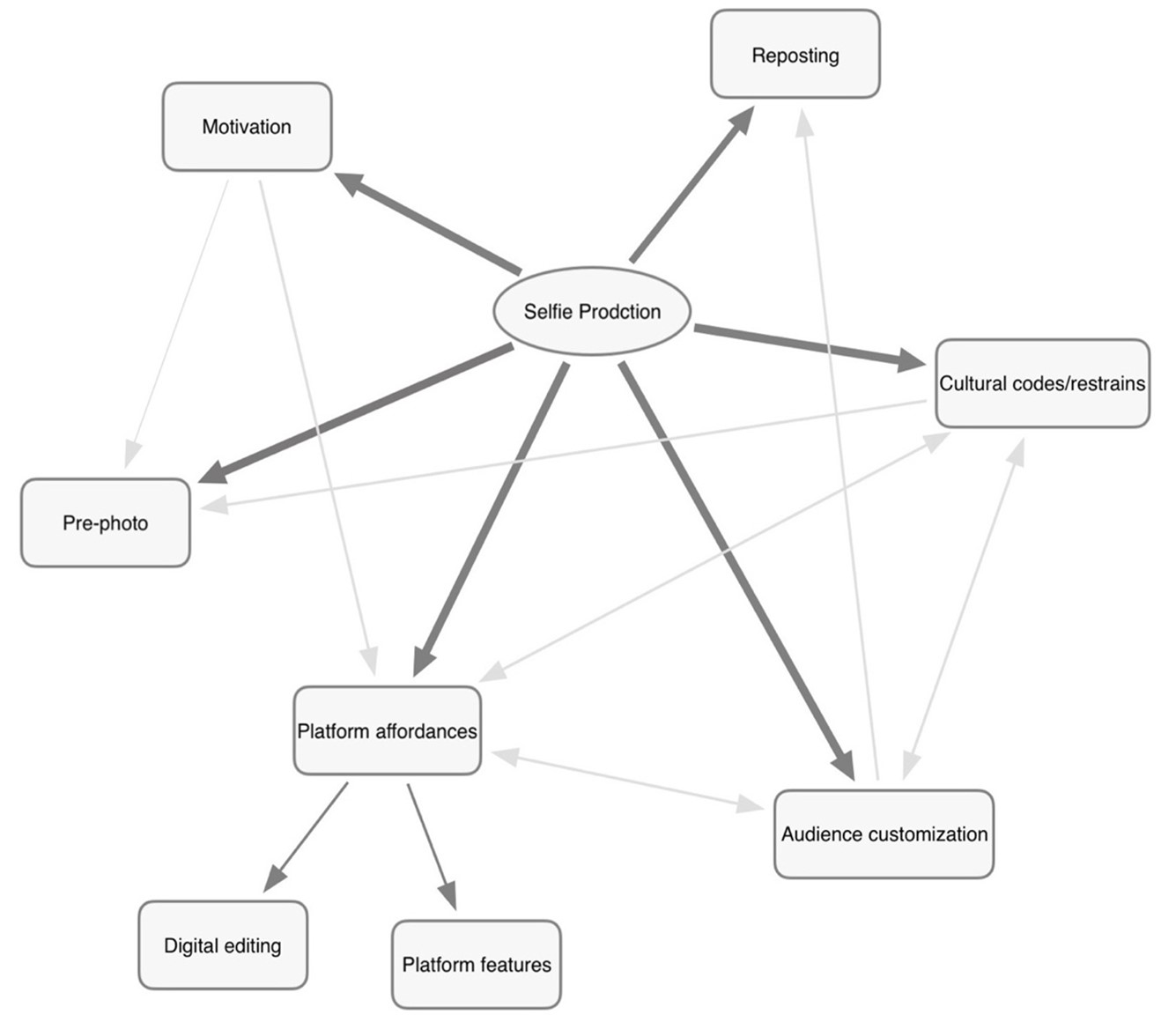

The findings of this study describe a selfie framework that highlights the role of cultural norms and digital affordances in shaping Saudi women’s selfie practices. It ultimately resulted in a six-process selfie production model (see Fig 1) that illustrates the experience of selfie taking, editing, and posting as encompassing six distinct processes: the motivation to take selfie, pre-photo process, platform affordances decisions, decisions reflecting cultural norms, audience customizing, and reposting the selfie. Some processes were noticed during the observation phase, while other processes were identified in statements made by participants during the interviews and focus groups.

Figure 1. The Selfie Production Model.

The six processes are described below, but note that these processes do not necessarily occur in a linear fashion, and due to selfie users’ varying creative processes. Selfie producers may choose to post a selfie, and then later decide to remove and/or edit it. Also, not every posted selfie is reproduced on other platforms. In other words, not all processes apply to every selfie, but at least two are always evident. Importantly, these processes interact, as indicated by the lighter-color arrows: for instance, cultural codes inform both the preparations process and the digital affordances used to produce the selfie.

The Motivation Process

In this process, the selfie taker becomes motivated to capture a selfie for many possible reasons. This study found that selfie producers’ decisions to take selfies are primarily informed by two primary motives: to seek attention, and to communicate the self. Secondary motivations were entertainment, experimenting with face filters, empowering others, and educating others about current events. Selfie takers who were motivated to communicate the self and to seek viewers’ attention were more likely to use digital enhancing affordances provided by Snapchat, such as the black and white filter (which can hide undesired facial features) or the flower crown filter (which makes the complexion seem fairer and to glow).

In terms of context and activity, participants were most likely to take selfies when dressed up and feeling attractive, while away on a trip, when going out (which they felt would be “worth documenting”), while doing something “interesting” in their spare time, to counteract being bored (such as at women’s social events), or to pass time while in the back seat of a car. In these contexts, the decision to take a selfie was related to the notion of impression management. As Khansa, a 32-year-old professional, explained: “I usually capture selfie images when I am looking elegant as if I am going to a wedding party or getting back from a social gathering.” Khansa’s expression indicates that selfie producers signal to others that they are doing something interesting or they are looking desirable. Therefore, they are motivated to share these images online instead of archiving them in a photo album in a smart phone.

Pre-Photo Process

In this process, selfie producers employed a series of preparation strategies such as arranging the area appearing in the background, posing next to an interesting object (e.g., a statue, a bouquet of flowers, or a landscape feature), applying makeup, putting on a veil, or removing an unwanted object like a cigarette.

For instance, 22-year-old Donia explained: “my family knows that I smoke, it is just not appropriate to post this kind of selfie in front of relatives who might and would judge me or my parents.” This illustrates the fact that smoking a hookah or cigarette is negatively perceived when done by women in Saudi Arabia, so during this process, a selfie taker would be motivated to remove it from display. Donia’s case exemplifies how cultural codes process informs the pre-photo process.

Figure 2. Positioning the Selfie With Other Objects.

Fig 2 is an example of the strategy of positioning the selfie next to an interesting object. This selfie includes a waterfall in Ireland deliberately chosen as the background. My interviews revealed how photos such as these were usually the result of several attempts, as the selfie taker ensured that the background was just right, all subjects were looking towards the camera, and they all had presentable facial expressions and outfits.

Carbon’s (2017) argued that, unlike traditional self-portraits, selfie producing involves little preparation. In contrast, the findings here the importance of pre-photo preparations. Participants referred to a range of practices including:

- Avoiding posting funny looking selfies, chubby face selfies, and scary looking selfies in an archived account like Instagram. Instead, these are only posted on Snapchat.

- Taking the selfie from above to give the appearance of being thinner.

- Being cautious about tiny facial defects which may not be obvious to others.

- Applying face makeup just for the purpose of taking and sharing a selfie.

- Taking a selfie in front of the mirror to display a full image of the photographer.

- Arranging the background which will appear in the selfie.

- Making sure that other members in a group selfie are looking good before posting.

The strategies observed reveal that selfie producers place much emphasis on the social self (i.e., the front stage). During interviews, selfie producers agreed that taking a selfie from above makes the face looks thinner and covers up a chubby neck. The effect of the camera angle is a technological affordance, but the meaning of the resulting image is context-dependent.

In addition to the above strategies, the majority of the participants stated that they usually do not post online the first selfie taken. Instead, they take a few photos until they are satisfied with the one to be shared. This action of selfie retaking is significant, as it reveals that social media users usually build their online content aware of the imagined audience who will view the posted image (Marwick & boyd, 2011).

Another enhancing strategy is to take a selfie according to the best side of the face. Lamar, a 19-year-old student, was asked what interests her about selfie communication. She said: “If I take a selfie of myself it is going to appear better than a photograph taken by someone else because I know the beautiful angles in my face.” Other participants indicated that, before taking selfies that they intend to share, they have to make some preparations. This includes actual makeup and arranging the location, both of which, in Goffman’s view, are part of staging a front stage performance.

Platform Affordances Process

The pre-photo process includes actions taking place before capturing the selfie. This next process outlines the digital editing applied after the selfie has been captured, and selfie takers’ decisions about posting on Snapchat or Instagram based on the application affordances. This process answers the first research question “how do the platform affordances inform selfie production?”

Digital Editing

Selfie takers make decisions about how to edit the selfie in terms of content by personalizing the selfie using digital editing effects such as face filters, geofilters, Bitmoji avatars, black and white filters, occasional filters, and seasonal filters. Other possibilities include adding text (e.g., details about time or temperature), a caption, or an emoji to the selfie. The following interview with two college students illustrates how selfie producers rationalized the editing process.

Researcher: What is your opinion on editing selfies prior to posting?

Merna: I think people who do so are smart…so some people try to make their nose look smaller, their lips look fuller…

Researcher: So, this editing you are talking about is different from applying the filters provided by Snapchat and Instagram?

Shaza: Yes. Using these features, we can control the brightness of the selfie, make it a black and white selfie, or edit the whiteness of the eye.

Merna: Snapchat has its own filtering options that have to do with brightness, adding location or time, and selfie filters.

Researcher: So, what interests you in applying these makeovers and edits to your selfies?

Merna: To appear prettier. It is that simple.

Shaza: Exactly, we want our selfies to make us seem prettier than in reality.

This shows that the process of digitally enhancing one’s selfie is directly linked to presenting a front stage self in online spaces. This also reveals that selfie producers make a conscious effort to use editing in applications other than Snapchat and Instagram to ensure that all facial imperfections are fixed. The significance lies in shaping the performance and the production of selfies to suit a variety of online audiences using technological tools. This reflects dominant platform practices among users.

Selfie editing has been considered in prior research (Chae, 2017; Chua & Chang, 2016; McLean et al., 2015), yet studies have not recognized the virtual makeover step as a part of the broader selfie production process. Chua and Chang (2016) specified that selfie producers used digital effects to brighten the skin, to enhance color and effects, to change the size of the nose, to remove acne, and to blur facial imperfections. However, the present study specified six new strategies used by female selfie takers that allow them to present a desirable digital self, including:

- Applying beautifying face filters like “flower crown” and “butterflies”.

- Applying digital makeup, as in the case of “eyelashes and a lipstick filter”, “makeup filters”, “contouring filters”, “makeup and gems filter”.

- Using a black and white filter to disguise undesired facial features.

- Adding geofilters of interesting locations to the selfie to impress others.

- Removing less glamorous selfies when posted by others (as in group selfies).

- Setting the phone on Airplane mode before posting selfies on Snapchat, to see how the selfie or series of selfies would look to viewers without actually posting them, then deciding whether to post the selfie (i.e., process four of the selfie model).

These strategies are used to communicate the image of a desirable self in online spaces, in accordance with Yang and Li’s (2014) study that found that women tend to post positive images on SNS to meet their social needs with the goal of receiving responses from others. Indeed, in Saudi culture, digital spaces maybe some of the only spaces in which women can share images of themselves in relatively safe “public” spaces. The enhancing digital strategies also show the association between platform affordances process and motivation process as the desire to seek attention informed using particular digital makeover such as contouring filters.

Note that selfie producers may use digital enhancing effects to modify very minor facial details that might not be noticed by the viewer. For example, one participant, Merna, indicated in an interview that she applied editing effects to hide acne that the researcher had not noticed. Arwa self-consciously felt that her forehead was too big, and so uses a flower crown filter because it covers a large area of her forehead. In her interview, Maha indicated that there are freckles in some parts of her face; therefore, she never posts selfies unless she applies actual or digital makeup. Digital makeup is a term used in the current study to refer to technological effects like makeup filters, contouring filters, and skin brightening filters which digitally blur facial imperfections in a manner similar to physical makeup.

The routine emphasis on these selfie practices should be interpreted as referencing a front stage level of the self. Importantly, this process demonstrated how the platform affordances enable selfie producers to hide facial imperfections and to add glamorous effects: that is, to present a variety of online selfie presentations. Note also that this process connects to audience customizing: in most cases, different types of face filters were associated with different audiences, such as the use of beauty filters for a public audience, versus silly ones for users who really “knew” the subject. These practices suggest that front stage presentation is juxtaposed with back stage presentation.

Choice of Platform

Selfie producers strategically select the platform used to post a selfie. Here different affordances on Instagram and Snapchat are contrasted. Regarding Snapchat and Instagram affordances, both platforms are designed for editing and sharing photographic content, but each is known to have distinctive features. Huda pointed this out when discussing differences between selfies shared on Snapchat and on Instagram:

Well, Snapchat selfie is a momentary image to capture a moment, so I will take the selfie in that moment regardless of all unattractive details like a messy background.. I mean the selfies are funny and spontaneous…but because Instagram selfies are permanent, I mean my images will be lasting in my Instagram account and followers can view it as many times as they like, unlike Snapchat selfies that are temporary.

This illustrates how Snapchat’s 24-hour limit for viewing an image make it a personal form of communication between close friends, rather than communication with random public users. On Snapchat, selfie takers are freer to choose either funny, beautifying, or ugly face filters to serve attention seeking or experimentation motives. On the other hand, Instagram offers affordances like posting status updates, check-ins, the ability to publicly “like” an image (Fatanti & Suyadnya, 2015), color editing, and permanent archiving of photos in one’s profile.

These affordances influence selfie producers’ decisions about editing the photos before posting them online. For example, selfies posted on an Instagram profile will be displayed permanently unless they are deleted by the user. Layla referred to this saying: “For Instagram selfies, you would choose the best position of a selfie, because the selfie is a record that will always be there.” Another participant indicated,

“Selfies that I post on Snapchat are reflections of my daily life with my girlfriends while being in a hookah café or dancing in a house. And so I am not adding my parents to Snapchat because this is my private zone, whereas they can view my Instagram selfies which are more professional and mature.”

Her example here shows how the selection of the platform is strongly connected with the audience customizing process, as each platform gives access more appropriate to a certain kind of audience. Thus, selfie takers decisions which platform to use are shaped by the technical features of the platform, audience’s expectations, and the cultural norms.

Audience Customization and Online Proxemics

These findings show that selfie producers make decisions about which audiences can view a selfie based on relational proxemics with viewers and cultural codes. Some types of selfies are allowed to be viewed by an audience within the public proxemics, as in the case of Instagram followers.

The data showed that both platform affordances and cultural codes played key roles in managing and segregating selfie viewers’ audiences. Thus, while unveiled and personal selfies are appropriately viewed by a close group of girlfriends and are thus posted on Snapchat, veiled selfies were shared with a broader audience via Instagram. While some selfies were posted on Snapchat’s public story or an Instagram public profile, others were shared through private messages to selected individuals or groups. For instance, Hanadi explained posting varying selfies on the platforms: “Instagram selfies are always veiled because there are male relatives and male colleagues who are in my network and are able to view my selfies. But my Snapchat account includes only girls.”

These findings assert that Saudi selfie posters were constructing “virtual walls”, a concept which was introduced earlier in the theoretical framework. For instance, posting a selfie while smoking a hookah as a private snap with a girlfriend creates a separation between the performance sent to a particular viewer, and the broader, public Instagram audiences or those who can see the public story of Snapchat.

Specifically, findings show three circles of selfie viewers based on the level of virtual intimacy. A public audience includes male users such as colleagues, relatives, or friends; a personal audience includes family members and girlfriends; and a private audience or “team of best friends” includes close girlfriends who are in the same age range as the selfie producer and who usually socialize with her.

This framework of three circles of intimacy shows that Saudi selfie producers intentionally decide to keep different categories online social contexts separated from one another, which might reflect wanting to have a separate space for close girlfriends within a male-dominated society. A previous study (Costa, 2018) confirmed that SNS users created up to twelve Facebook accounts to distinguish social spheres and social groups from one another. However, the current study is the first to identify three distinct circles of selfie viewers, and to introduce the concept of virtual walls in relation to SNS communication.

Distinctions between spaces in offline settings extend to selfie behaviors online, and transitioning between digital spaces is a reproduction of moving between traditional offline environments in Saudi. While women dress up and do not wear a veil in women’s gatherings, they change their appearance when they leave the host’s house, and they wear the hijab when appearing in public. The researcher also identified a parallel between the level of formality maintained in selfie practices, and dealing with non-mahram males in offline spaces. In addition, the architecture of platforms played an important role in allowing selfie producers to control their presentations easily, presenting a performance that suits the intended viewing audience.

To illustrate the third circle, Rotana commented, “My selfie is a credible way to communicate who I am to my girlfriends, but I don’t fully express who I am to general snappers [i.e., the public].” When I asked her why there are distinctions between expressing herself to girlfriends and others, she said, “Because there are people who I don’t allow to see all of my actions.” Thus, selfie producers think about their relational closeness with viewers when choosing the virtual space in which the image is posted.

The main distinction between the second “personal” circle and the third “private” circle is that users from the second personal circle may judge or post negative comments on the selfie, while viewers from the third network are likely to support the selfie producer and to share secret performances. Selfie interactions within the third circle demonstrate that Saudi selfie producers actively shape an online private space to interact with others away from the supervision of parents and the judgment of relatives. Therefore, age and gender are essential considerations in audience composition. According to the data, participants excluded older female family members and men who might be judgmental from viewing the selfies shared with close girlfriends forming the third private circle.

In the context of online proxemics, the researcher investigated reasons for excluding users from viewing selfies. The findings identified three main reasons for blocking selfie viewers: passive viewers, power relations, and the evil eye. The evil eye or Aian is a common concept in Middle Eastern cultures that refers to accidents and damages caused by the envy of others. Passive viewers refer to users who view the selfie without interacting with it using comments or likes. Secondary reasons for blocking selfie viewers included loss of interest, or violations of privacy. Blocking certain viewers could be understood as a way of attracting viewers who would interact positively with the image. However, in the Saudi context, a more subtle reading of blocking actions would be that women who face power differentials and who are not allowed to express themselves publicly (i.e., in the offline environment), attempt to compensate by using self-portraiture in digital spaces from which dominant family members or judgmental relatives are excluded.

Decisions About Cultural Norms

In this process, selfie takers consider the appropriateness of selfie content in relation to social norms, cultural codes, and family traditions. Selfie producers think deeply about whether or not to share their selfie with their online network. Most importantly, participants try to predict how others will react to the posted selfie, what kind of comments they will receive, and the number of Likes they will receive. As an illustration, I asked Shaza (21 years old) and Merna (22 years old), “Before uploading your selfies online, do you think of what people value in you or how you want them to perceive you?” They replied:

Shaza: I see the selfie 200 times and I think a lot about how people will view it.

Merna: And what would they see in it? And I ask someone who is sitting close to me about her opinion before I post it.

Shaza: And I zoom the picture and look at it closely.

Researcher: So there is a lot of processes?

Shaza: Yes, and deep thinking.

Looking at a selfie and its details up to 200 times before uploading the image, asking for another opinion prior to posting the selfie, and zooming in on the selfie to examine it meticulously illustrates how carefully selfie takers consider viewers’ reactions. Only after such considerations do selfie producers make a final decision whether or not to post the image online.

To get a sense of the contexts that might be informed by cultural codes, participants were asked during the interviews about the selfies they did not post. Participants’ responses indicated that users will decide not to post selfies online for many reasons, including: the selfie included inappropriate jokes, the producer was wearing revealing clothes, the selfie was taken while dating someone (i.e., showing an illegal relationship), it was an intimate selfie with a spouse, the selfie taker was smoking a hookah, the selfie included someone who did not want their picture shared online, the selfie included an inappropriate hand gesture, the selfie included an undesirable item like a cigarette, or the background was untidy. These cases indicate selfie takers consider how their audience might interpret the image in relation to conservative Saudi cultural norms. They also demonstrate that people tend to maintain their cultural identity (Hall, 1966) through connecting with the values, religious beliefs, aesthetics, and ethnicity of a particular social group or culture. Although this process addressed the second research question about the role of cultural norms in shaping selfie practices, the cases presented earlier in the platform affordances process and audience customizations process indicated that decisions about cultural norms occurs in many processes.

Reposting the Selfie

After posting a selfie on a selected platform like Snapchat, users consider whether or not to reproduce the selfie in other social media platforms like Instagram, WhatsApp, or Path. The reasons for reproducing the selfie include: the digital enhancing effects available on a particular platform, positive reactions to a selfie on one platform, and the desire to share a selfie with other audiences. For instance, Mona said: “I usually share selfies that I posted on Snapchat on WhatsApp as my parents don’t have Snapchat.” Additionally, Eman explained “the face filters and pictures of Snapchat are amazing, so I would usually share Snapchat selfies that I like on Instagram”—that is, the first platform is used for digital makeovers while the second is used to archive desirable selfies. This suggests that Snapchat is the back stage where a selfie taker prepares for a front stage performance.

Discussion

The six-process selfie model suggests that both the “imagined audience” and cultural codes are in the minds of female Saudi selfie producers. Thus, controlling the image, deciding who can have access to it, and in what context it may be shared online were motivated by seeking attention from an audience who interpret the selfie in light of Saudi social conventions.

The selfie model was one of the original contributions that emerged from this study. However, a number of previous studies referred to individual processes of the model. Al-Kandari and Abdelaziz (2018) noted that documentation is a predictor for taking selfies, which is part of the motivation process as proposed in the model. Similarly, Etgar and Amichai-Hamburger (2017) identified documentation, belonging, and self-approval as motivators for taking selfies, which also points to the motivation process of this study. Others emphasized the pre-photo process by analyzing the positioning and posing in a selfie as in mirror selfies (Shipley, 2015) and selfies taken in museums next to works of art (Kozinets et al., 2017). In both cases, the positioning of the subject in relation to other objects is part of the “pre-photo” process. Editing selfies to present a desirable self has also been identified (Al-Kandari & Abdelaziz, 2018; Chae, 2017; Chua & Chang, 2016; McLean et al., 2015), which was addressed in the digital editing portion of the platform affordances process. Costa’s (2018) study conducted in Turkey asserted that the imagined audiences on SNS guide users to adjust their performances actively, including posting different content to different audiences using different profile accounts. Therefore, her study also points to platform affordances and audience customization that were proposed in the model of this study, in which selfie users select carefully who might view and access their selfies. Keller’s study (2016) on feminism and Tumblr also pointed to the platform affordances process in the model.

By bringing together various processes of selfie production, this study makes a significant contribution to knowledge by providing a holistic understanding of various processes in selfie production processes which ideally alerts later scholars to other dimensions of selfie production which they may have missed.

These findings mirror Hall’s (1966) four spaces: intimate, personal, social, and public. In fact, it was found that Saudi selfie posting was fundamentally based on audience segregation: segregating the audience based on virtual intimacy and cultural codes like veiling practices was particularly significant in the case of Saudi women. Extending Hall’s (1966) proxemics to selfie communication, it was found that selfie producers take into consideration three circles of selfie viewers: a general audience, a personal audience (including judgmental individuals), and a private audience consisting of non-judgmental females in the same age range.

The Saudi cultural context that is based on gender segregation informed the reproduction of the offline setting in online selfie communications. As Hall’s theory positioned family members in the intimate zone and friends in the personal zone, this study thus revealed some contrasts, it showed that virtual walls are used to include and exclude members according to their virtual intimacy with the selfie producers. But due to Saudi gender roles, this study found alternate maps of intimacy. In an offline setting, this marking of spaces is informed by cultural norms and practices; however, in online spaces, the marking of spaces is also determined by both technological affordances and cultural norms.

Cultural norms were found to shape selfie practices in terms of considering veiling practices and the appropriateness of content as selfie producers either chose not to share the selfie or limit those who can view it (see the hookah example above). Recent studies (Kurniawati et al., 2019) have also addressed the role of veiling on selfie practices posted by Indonesian women. Using social semiotics, the study aimed to understand the representational meaning of veiled selfies based on the Instagram accounts of celebrities. The study concluded that celebrities posted veiled selfies to attract the attention of followers and facilitate their business.

Further, Monteiro’s study (2020) highlighted how Indian culture shapes selfie practices. Using critical technology approach, the study explored selfies in relation to the cultural Hindu ritual of darshan. The study explored intersections between smartphone marketing, the use of selfies in Hindu politics, and the cultural influence of darshan practice. The study reported that the interaction between the device and the user has become a fundamental component of performing the self. Combined with the current study, this body of research outlines the importance and potential of understanding selfie practices in relation to cultural contexts.

Limitation and Future Research

The study limitations stem from the sampling type, snowball network sampling, used for collecting the data, as it resulted in a narrow selection of highly educated participants and a strong regional focus. Considering the Saudi cultural codes, accessing female personal photos required a level of trust which impacted the researcher’s choices to use a network and snowball sampling. As a result, most participants came from Jeddah and they were middle or upper social class.

In addition to the narrow selection of population in terms of class and demographics, the size of the sample which included 35 Saudi females was small. However, the objective of this study was to not produce generalisations about selfie production. Instead, this ethnographic study was aimed at a deep exploration of the processes of taking, editing, and sharing selfies with a view to understanding how selfie production is informed by Saudi cultural norms and by platform affordances. Future studies could focus on different regions in Saudi or try to reach participants from lower social classes or younger age groups or include a larger sample size.

Finally, the translation of the conversations and transcripts from Arabic to English is another limitation. According to Simon (1996) and Temple and Young (2004), translating data in qualitative research may result in semantic loss of those meanings, especially when translating cultural meanings that are embedded in linguistic expressions. Some meanings and expressions in Arabic which do not have exact translations were translated to their closest meaning in English. An example would be the word ‘temaileh’ which was translated as ‘to show off’.

Conclusion

The identification of the selfie model for the process of taking, editing, and sharing selfies was one of the important contributions of this study. Selfie and other social media researchers may assess the selfie model in different research settings, for example, a younger sample, or a cross-gender sample. They could undertake longitudinal studies, or they could investigate social media platforms other than Snapchat and Instagram.

This study identified six processes that inform Saudi women’s selfie practices: the motivation process, pre-photo process, platform affordances process, cultural norms process, audience customizing process, and reposting the selfie.

Future selfie studies could investigate whether these processes also apply to Western cultures. Indeed, as SNS environment, and peer influences make for depictions of an idealized female body (Cohen et al., 2017), an investigation of male selfie takers would be useful to see whether or not such processes are gender-specific. A cross-gender study might provide novel insights into how each gender conceptualizes selfie presentations. It is hoped that future scholars might test this model in other geographical and cultural contexts.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2021 Afnan Qutub