Caregiving strategies, parental practices, and the use of Facebook groups among Israeli mothers of adolescents

Vol.15,No.3(2021)

Facebook offers a “village” for mothers to come together and seek and share parenting information, but while there has been substantial research examining both positive and negative aspects of parents’ Facebook use, there is no research on use of Facebook by mothers of adolescents and its association with parent-adolescent relationships. Given the intense challenges of raising adolescents and the dearth of research into potential benefits and drawbacks of mothers of adolescents seeking support from Facebook, we sought to fill this gap by focusing on the caregiving and parenting practices of mothers of adolescents who were members of mothers’ groups on Facebook. The sample included 74 Israeli dyads of mothers (Mage = 43.73, SD = 4.41), who participated in Facebook groups for mothers and their adolescent children (Mage = 12.26, SD = 3.11) during 2019. Mothers reported on their Facebook use and caregiving strategies. The adolescents answered a parenting practices questionnaire. It was found that higher permissiveness and greater psychological intrusiveness were related to higher use of Facebook by the mothers. Among mothers who were high on hyperactivation, greater permissiveness and psychological intrusiveness were related to higher Facebook use to a greater extent than among mothers who were low on hyperactivation. Alongside Facebook’s benefits as a community for mothers come serious risks for some mothers. As research in this area grows, an examination of the characteristics of Facebook use by mothers of adolescent children involved in Facebook mothers’ groups is meaningful.

Facebook use; mothers; adolescents; parenting practices; caregiving strategies

Alon Goldberg

Tel-Hai College, Department of Education, Upper Galilee

Alon Goldberg, Ph.D. is a senior lecturer in the Department of Education and the head of Psychology Studies at the department of Multi-Disciplinary Studies at Tel-Hai Academic College in Israel. His Ph.D. degree is in the field of Counseling and Human development. His research interests include parent-adolescent relationships, parents' adjustment to child's disease, higher sensitivity personality and in the last years focuses on the adjustment of adult children to their parents' disease.

Yael Grinshtain

Tel-Hai College, Department of Education, Upper Galilee

Yael Grinshtain, Ph.D., is a senior faculty member in the Department of Education at Tel-Hai Academic College. Her research interests include gender and ethnicity in the teaching profession and in educational leadership; parental engagement at home and at school including help seeking and help giving orientations; social and cultural aspects of rural education. In her research she implements qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches.

Yair Amichai-Hamburger

The Research Center for Internet Psychology, Sammy Ofer School of Communication, Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya

Yair Amichai-Hamburger, Ph.D. is a professor of Psychology and Communication, and director of the Research Centre for Internet Psychology (CIP) at the Interdisciplinary Centre, IDC, Herzlia. He has written widely on the impact of the Internet on wellbeing.

Abel, S., Machin, T., & Brownlow, C. (2019). Support, socialise and advocate: An exploration of the stated purposes of Facebook autism groups. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 61, 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2019.01.009

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc.

Amaro, L. M., Joseph, N. T., & de los Santos, T. M. (2019). Relationships of online social comparison and parenting satisfaction among new mothers: The mediating roles of belonging and emotion. Journal of Family Communication, 19(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2019.1586711

Amichai-Hamburger, Y. (2017). Internet psychology: The basics. Routledge.

Amichai-Hamburger, Y., Gazit, T., Bar-Ilan, J., Perez, O., Aharony, N., & Bronstein, J., & Dyne, T. S. (2016). Psychological factors behind the lack of participation in online discussions. Computers in Human Behavior, 55(Part A), 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.009

Amichai-Hamburger, Y., & Vinitzky, G. (2010). Social network use and personality. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1289–1295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.018

Ammari, T., & Schoenebeck, S. (2015). Networked empowerment on Facebook groups for parents of children with special needs. In CHI '15: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2805–2814). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702324

Ammari, T., Schoenebeck, S. Y., & Morris, M. R. (2014, May). Accessing social support and overcoming judgment on social media among parents of children with special needs [Paper presentation]. Eighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Ann Arbor, MI, United States.

Appel, M., & Gnambs, T. (2019). Shyness and social media use: A meta-analytic summary of moderating and mediating effects. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 294–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.04.018

Archer, C. (2019). How influencer ‘mumpreneur’ bloggers and ‘everyday’ mums frame presenting their children online. Media International Australia, 170(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X19828365

Archer, C., & Kao, K.-T. (2018). Mother, baby and Facebook make three: Does social media provide social support for new mothers? Media International Australia, 168(1), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X18783016

Bartholomew, M. K., Schoppe-Sullivan, S., Glassman, M., Dush, C. M. K., & Sullivan, J. M. (2012). New parents’ Facebook use at the transition to parenthood. Family Relations, 61(3), 455–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00708.x

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129836

Belsky, J., & Jaffee, S. R. (2006). The multiple determinants of parenting. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (2nd ed., pp. 38–85). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Blum-Ross, A., & Livingstone, S. (2017). “Sharenting”, parent blogging, and the boundaries of the digital self. Popular Communication, 15(2), 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2016.1223300

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Attachment (2nd ed., Vol. 1). Basic Books.

Brosch, A. (2016). When the child is born into the Internet: Sharenting as a growing trend among parents on Facebook. The New Educational Review, 43(1), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.15804/tner.2016.43.1.19

Chae, J. (2015). “Am I a better mother than you?”: Media and 21st-century motherhood in the context of social comparison theory. Communication Research, 42(4), 503–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214534969

Chalklen, C., & Anderson, H. (2017). Mothering on Facebook: Exploring the privacy/openness paradox. Social Media + Society 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117707187

Chang, C. (2019). Ambivalent Facebook users: Anxious attachment style and goal cognition. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(8), 2528–2548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407518791310

Collins, W. A., & Laursen, B. (2006). Parent–adolescent relationships. In P. Noller & J. A. Feeney (Eds.), Close relationships: Functions, forms and processes (pp. 111–125). Psychology Press.

Coyne, S. M., McDaniel, B. T., & Stockdale, L. A. (2017). “Do you dare to compare?” Associations between maternal social comparisons on social networking sites and parenting, mental health, and romantic relationship outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 335–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.081

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113(3), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487

de los Santos, T. M., Amaro, L. M., & Joseph, N. T. (2019). Social comparison and emotion across social networking sites for mothers. Communication Reports, 32(2), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2019.1610470

de Vries, D. A., & Kühne, R. (2015). Facebook and self-perception: Individual susceptibility to negative social comparison on Facebook. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 217–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.029

Doty, J. L., & Dworkin, J. (2014). Online social support for parents: A critical review. Marriage & Family Review, 50(2), 174–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2013.834027

Duggan, M., Lehnhart, A., Lampe, C., & Ellison, N. B. (2015, July 16). Parents and social media. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/07/16/main-findings-14/

Fardouly, J., Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., & Halliwell, E. (2015). Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women's body image concerns and mood. Body Image, 13, 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.12.002

Flynn, S., Noone, C., & Sarma, K. M. (2018). An exploration of the link between adult attachment and problematic Facebook use. BMC Psychology, 6, Article 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0245-0

George, C., & Solomon, J. (2008). The caregiving system: A behavioral systems approach to parenting. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 383–416). The Guilford Press.

Gerson, J., Plagnol, A. C., & Corr, P. J. (2017). Passive and Active Facebook Use Measure (PAUM): Validation and relationship to the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 117, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.05.034

Gibson, L., & Hanson, V. L. (2013). Digital motherhood: How does technology help new mothers? In CHI '13: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 313–322). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2470654.2470700

Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetic theory of social behavior. I and II. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7, 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4

Hart, J., Nailling, E., Bizer, G. Y., & Collins, C. K. (2015). Attachment theory as a framework for explaining engagement with Facebook. Personality and Individual Differences, 77, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.016

Hatzithomas, L., Misirlis, N., Boutsouki, C., & Vlachopoulou, M. (2019). Understanding the role of personality traits on Facebook intensity. International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising, 13(2), 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIMA.2019.099494

Jenkins-Guarnieri, M. A., Wright, S. L., & Hudiburgh, L. M. (2012). The relationships among attachment style, personality traits, interpersonal competency, and Facebook use. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 33(6), 294–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2012.08.001

Jones, J. D., Brett, B. E., Ehrlich, K. B., Lejuez, C. W., & Cassidy, J. (2014). Maternal attachment style and responses to adolescents’ negative emotions: The mediating role of maternal emotion regulation. Parenting, 14(3–4), 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2014.972760

Kaspar, K., & Müller-Jensen, M. (2019). Information seeking behavior on Facebook: The role of censorship endorsement and personality. Current Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00316-8

Laws, R., Walsh, A. D., Hesketh, K. D., Downing, K. L., Kuswara, K., & Campbell, K. J. (2019). Differences between mothers and fathers of young children in their use of the Internet to support healthy family lifestyle behaviors: Cross-sectional study. JMIR, 21(1), Article e11454. https://doi.org/10.2196/11454

Lee, C.-T., Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Memmott-Elison, M. K. (2017). The role of parents and peers on adolescents’ prosocial behavior and substance use. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34(7), 1053–1069. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407516665928

Li, S., & Feng, B. (2015). What to say to an online support-seeker? The influence of others’ responses and support-seekers’ replies. Human Communication Research, 41(3), 303–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12055

Lipu, M., & Siibak, A. (2019). ‘Take it down!’: Estonian parents’ and pre-teens’ opinions and experiences with sharenting. Media International Australia, 170(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X19828366

Lupton, D. (2016). The use and value of digital media for information about pregnancy and early motherhood: A focus group study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16, Article 171. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0971-3

Lupton, D., & Pedersen, S. (2016). An Australian survey of women's use of pregnancy and parenting apps. Women and Birth, 29(4), 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2016.01.008

Marshall, T. C., Lefringhausen, K., & Ferenczi, N. (2015). The Big Five, self-esteem, and narcissism as predictors of the topics people write about in Facebook status updates. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.039

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2012). Adult attachment orientations and relationship processes. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 4(4), 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2012.00142.x

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. The Guilford Press.

Morris, M. R. (2014). Social networking site use by mothers of young children. In CSCW '14: Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (pp. 1272–1282). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2531602.2531603

Oldmeadow, J. A., Quinn, S., & Kowert, R. (2013). Attachment style, social skills, and Facebook use amongst adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 1142–1149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.006

Orton-Johnson, K. (2017). Mummy blogs and representations of motherhood: “Bad mummies” and their readers. Social Media+ Society, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117707186

Reizer, A., Ein‐Dor, T., Shaver, P. (2014). The avoidance cocoon: Examining the interplay between attachment and caregiving in predicting relationship satisfaction. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44(7), 774–786. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2057

Scharf, M. (2014). Parenting in Israel: Together hand in hand, you are mine and I am yours. In H. Selin (Ed.), Parenting across cultures: Childrearing, motherhood and fatherhood in non-Western cultures (pp. 193–206). Springer.

Scharf, M., Mayseless, O., & Rousseau, S. (2016). When somatization is not the only thing you suffer from: Examining comorbid syndromes using latent profile analysis, parenting practices and adolescent functioning. Psychiatry Research, 244, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.07.015

Scharf, M., & Shulman, S. (2006). Intergenerational transmission of experiences in adolescence: The challenges in parenting adolescents. In O. Mayseless (Ed.), Parenting representations: Theory, research, and clinical implications (pp. 319–351). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511499869.012

Schoenebeck, S. (2013). The secret life of online moms: Anonymity and disinhibition on YouBeMom.com. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 7(1), 555–562. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/14379

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Yavorsky, J. E., Bartholomew, M. K., Sullivan, J. M., Lee, M. A., Dush, C. M. K., & Glassman, M. (2017). Doing gender online: New mothers’ psychological characteristics, Facebook use, and depressive symptoms. Sex Roles, 76(5–6), 276–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0640-z

Seidman, G. (2013). Self-presentation and belonging on Facebook: How personality influences social media use and motivations. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(3), 402–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.10.009

Shaver, P. R., Mikulincer, M., & Shemesh-Iron, M. (2010). A behavioral-systems perspective on prosocial behavior. In M. Mikulincer & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature (pp. 73–91). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12061-004

Sorensen, S. (2016). Protecting children’s right to privacy in the digital age: Parents as trustees of children’s rights. Children’s Legal Rights Journal, 36(3), Article 2. https://lawecommons.luc.edu/clrj/vol36/iss3/2

Steinberg, L., & Silk, J. S. (2002). Parenting adolescents. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Children and parenting (Vol. 1, pp. 103–133). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Steinberg, L., & Steinberg, W. (1994). Crossing paths: How your child’s adolescence triggers your own crisis. Simon & Schuster.

Strange, C., Fisher, C., Howat, P., & Wood, L. (2018). ‘Easier to isolate yourself… there’s no need to leave the house’ – A qualitative study on the paradoxes of online communication for parents with young children. Computers in Human Behavior, 83, 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.040

Taraban, L., & Shaw, D. S. (2018). Parenting in context: Revisiting Belsky’s classic process of parenting model in early childhood. Developmental Review, 48, 55–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.03.006

Tokić Milaković, A., Glatz, T., & Pećnik, N. (2018). How do parents facilitate or inhibit adolescent disclosure? The role of adolescents’ psychological needs satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(8), 1118–1138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517705228

Weinberger, D. A., Feldman, S. S., & Ford, M. E. (1989). Validation of the Weinberger Parenting Inventory for preadolescents and their parents. Unpublished manuscript.

Editorial Record

First submission received:

June 12, 2020

Revisions received:

October 16, 2020

March 24, 2021

May 3, 2021

Accepted for publication:

May 17, 2021

Editor in charge:

Michel Walrave

Introduction

Facebook offers a “village” for mothers to come together and seek and share parenting information. There has been substantial research examining parents’ Facebook use, including studies that have revealed that mothers use Facebook as a parenting support network much more than fathers do (Duggan et al., 2015). As Archer and Kao (2018) indicated, “Mothers are increasingly seeing social media in general, and Facebook in particular, as a ubiquitous part of their parenting experience” (p. 134).

Facebook use, though, comes with risks for mothers, including possible overuse, comparison and judgment of each other, and privacy concerns. While there have been ample studies focused on Facebook use by mothers of infants and young children or “new” parents (Archer & Kao, 2018; Bartholomew et al., 2012; Lupton, 2016; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2017), few have studied Facebook use by parents of adolescents (Lipu & Siibak, 2019). Given the intense challenges of raising adolescents and the dearth of research into potential benefits and drawbacks of mothers of adolescents seeking support from Facebook, we sought to fill this gap by focusing on the parenting behavior of mothers of adolescents as related to their use of mothers’ Facebook groups.

Facebook Use

Facebook as a social medium provides a way for people to connect with each other and exchange experiences during challenging periods, usually following two main patterns: active use, characterized by posting messages or uploading photos, and passive use, based on checking others’ pages, pictures, and updates (Amichai-Hamburger et al., 2016; Gerson et al., 2017). Facebook use in general and the impact of individuals’ differences on their Facebook use are broadly discussed in the literature (Amichai-Hamburger & Vinitzky, 2010; Appel & Gnambs, 2019; Jenkins-Guarnieri et al., 2012; Kaspar & Müller-Jensen, 2019; Marshall et al., 2015). Individuals who have social difficulties in “real life” (neuroticism, anxiety, etc.) have been found to seek more information on Facebook (Kaspar & Müller-Jensen, 2019) and to use it to meet needs for belongingness, acceptance, and social contact and to bring out the best in themselves (Hatzithomas et al., 2019; Seidman, 2013). However, social network use has been found to be associated with negative outcomes, such as negative social comparison, negative body image, unhappiness, etc. (e.g., Amichai-Hamburger, 2017; de Vries & Kühne, 2015; Fardouly et al., 2015).

Both active and passive use of Facebook offer parents the opportunity to upload their own material and respond to other people’s content (Blum-Ross & Livingstone, 2017; Brosch, 2016). Parents can use Facebook for several major purposes. For mothers, Facebook is a source of knowledge that enables them to become familiar with concerning issues of parenting and child-rearing by seeking information, comparing themselves with other mothers, assessing their own performance, getting support, and expressing emotions (Archer, 2019; de los Santos et al., 2019; Li & Feng, 2015). Mothers of special-needs or LGBTQ children were found to use social media sites to alleviate feelings of marginalization and stigmatization by interacting with other parents in their position (Abel et al., 2019; Ammari et al., 2014; Ammari & Schoenebeck, 2015). Finally, mothers with infants and young children have found Facebook mothers’ groups to be a platform to meet other mothers living nearby in person, coping with their sense of loneliness (Gibson & Hanson, 2013; Lupton, 2016; Lupton & Pedersen, 2016; Morris, 2014).

As the benefits of Facebook as a platform for sharing, participating, and gaining support for parents are clear, it is worth also mentioning the “dark side” of this communication method, it can provide a platform for antagonistic cultures and norms (e.g., Schoenebeck, 2013). Overusing social media by parents to share content based on their children, such as photos, activities, etc. (referred to as “sharenting”) (Blum-Ross & Livingstone, 2017), may adversely affect both parents and children. The publication of photos, stories, dilemmas, practices, and decisions can be viewed as intruding on children’s privacy (Chalklen & Anderson, 2017; Sorensen, 2016) and create conflicts and disagreements between children and parents (Lipu & Siibak, 2019). Mothers who are involved in social media sites specifically for mothers might practice social comparison and experience judgment regarding their motherhood that might negatively affect their motherhood practices (Chae, 2015; Coyne et al., 2017; Orton-Johnson, 2017).

Adolescents

Adolescence is an especially challenging period for children and parents because of major biological, cognitive, and emotional changes that children undergo at that age (Scharf & Shulman, 2006) and because of changes in parent–adolescent relationships. Adolescents spend increasingly less time with their parents and more time with peers (Lee et al., 2017; Scharf & Shulman, 2006), making it more difficult for parents to monitor adolescents’ whereabouts. Moreover, this period was reported to be one of the lowest points in parents’ lives (L. Steinberg & W. Steinberg, 1994) as they address their own concerns about their growing midlife needs (L. Steinberg & Silk, 2002), along with their efforts to support adolescents’ growing need for autonomy, individuation, and more egalitarian relationships (Tokić Milaković et al., 2018). These changes may increase parent–adolescent conflict, parental feelings of ineffectiveness, and parental strain (Collins & Laursen, 2006), which might be reflected in parenting practices.

Parenting Practices and Caregiving Strategies

Parenting practices are specific behaviors that parents use to socialize their children. These behaviors are shaped by multiple factors that include individual characteristics of the parent and child, as well as sociocultural and contextual factors (Belsky, 1984). Parental characteristics and parental psychological functioning are the most important determinants of parenting because they most affect parenting practices (Belsky, 1984; Belsky & Jaffee, 2006; Darling & L. Steinberg, 1993; Taraban & Shaw, 2018).

Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1982) suggests that an individual’s caregiving behaviors (i.e., reactions to others’ needs) are regulated by the caregiving system. The caregiving system is aimed at concern for others (e.g., a partner), responding to their needs, and relieving their distress (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016; Shaver et al., 2010). The caregiving system, which is reciprocal to and highly associated with the attachment system, emerged over the course of evolution to increase viability for people’s children (George & Solomon, 2008; Hamilton, 1964). It has matured of late, with greater development during the transition to parenthood, integrating early experiences of a person’s life with the influences of the childbirth experience, child temperament, and sociocultural factors (e.g., “intensive parenting” ideology or authoritative societies), and has become a flexible system with a diversity of caregiving behaviors (George & Solomon, 2008).

Caregiving behaviors are activated by another’s signal of distress (e.g., a person in pain), which guides the caregiver to react to another person’s needs and\or to provide support; these behaviors are deactivated when the stimuli end or change and the system’s goals are achieved (i.e., relief of another’s pain; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). This process is regulated by mental representations of caregiving: representations of the self as a caregiver and of the other as worthy to receive care. Hence, while some individuals will develop positive representations of the self and the other, others will develop negative mental representations of caregiving with hyperactivation or deactivation caregiving strategies (Shaver et al., 2010).

Hyperactivation strategies are associated with excessive willingness to help the other, exaggerated appraisals of the other’s needs, anxieties\insecurities about the effectiveness of the care they provide, and chronically activated caregiving (Shaver et al., 2010). In the context of childrearing, it might be expressed as lower child-centeredness, inconsistent and unwelcome\uninvited care or gestures toward the child (intrusiveness) that is often asynchronous with the child’s needs (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016), which, in turn, may exacerbate negative representations of the self and the child (e.g., “I am a bad parent” or “what a stubborn child”), further intensify parents’ emotional difficulties (Shaver et al., 2010), and may lead to higher Facebook use in order to seek a sense of belonging and to be well-liked (Chang, 2019; Hart et al., 2015; Oldmeadow et al., 2013). By contrast, deactivation strategies are associated with discomfort when helping others, attempts to avoid calls for caregiving, emotional distancing from people in need, and feelings of boredom while caring for others (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012; Shaver et al., 2010). For parents, misinterpreting information that signals a child’s needs (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016) might lead to avoidant, detached, cold, harsh parenting (Jones et al., 2014). Individuals high in deactivation caregiving strategies might have more restrained use of social networks such as Facebook, due to the individual’s low extroversion (Hart et al., 2015). However, the impersonal communication and separation from others that Facebook provides might encourage them to be involved in it when experiencing emotional distress (e.g., mothering an adolescent child) and result in highly intrusive behavior (Flynn et al., 2018).

The Current Study

The current study examines the association between parenting practices and characteristics of caregiving strategies among mothers of adolescents and their use of mothers’ Facebook groups. It focuses on Israeli mothers who are members of Facebook groups for mothers of adolescents.

Israeli parents who were characterized by proximal parenting, reduced parental authority, and heightened permissiveness were found to have experienced more difficulties exerting parental authority during adolescence (Scharf, 2014). These difficulties might enhance parental strain as the adolescent child spends increasingly less time with the parent and more time with peers (Lee et al., 2017). As their parenting is challenged, parents might develop negative representations of the self and the child, further intensifying any emotional difficulties (Shaver et al., 2010), which may lead these parents to use ineffective care strategies (i.e., hyperactivation and\or deactivation) or negative parenting practices (i.e., permissiveness, psychological intrusiveness, inconsistency) and to be less attuned to their adolescent child’s needs (low child-centeredness).

Mothers’ use of Facebook groups as a source of knowledge, for seeking information, for comparing themselves with other mothers, for assessing their own parenting, and for sharing both positive and negative emotions has been found to have an influence over their satisfaction with their parenting (Amaro et al., 2019). While some mothers have indicated that Facebook groups have a positive influence on their parenting, some mothers have found the platform to be judgmental (Strange et al., 2018), competitive (Chae, 2015) report on parental role overload, and lower levels of parental competence (Coyne et al., 2017) and therefore exacerbate negative parenting behaviors and ineffective caregiving strategies (Collins & Laursen, 2006; Shaver et al., 2010). It also has been found that high involvement of mothers of young children in Facebook groups might be experienced by the child as intrusive parenting behavior (Chalklen & Anderson, 2017; Sorensen, 2016) and might intensify mother–child conflicts (Lipu & Siibak, 2019).

The current study examined the combined effect of caregiving strategies with parental practices on the involvement of mothers of adolescents in mothers’ Facebook groups. Based on the literature, we examined two central research hypotheses:

Hyperactivation and deactivation caregiving strategies will be positively correlated with the use of mothers’ Facebook groups. Higher levels of hyperactivation and deactivation caregiving strategies will be associated with higher levels of mothers’ use of Facebook groups.

Negative parenting practices (i.e., permissiveness, psychological intrusiveness, and inconsistency) will be positively correlated with the use of mothers’ Facebook groups, whereas child-centered parenting will be negatively correlated with the use of mothers’ Facebook groups. Higher levels of permissiveness, psychological intrusiveness, and inconsistent parenting practices and lower levels of child-centered parenting behavior will be associated with higher levels of mothers’ use of Facebook groups.

We also explored hyperactivation and deactivation caregiving strategies as moderators of the relationship between parenting and the level of use of mothers’ Facebook groups.

Method

Participants

The sample included 74 dyads of mothers who participated in motherhood Facebook groups and their adolescent child. The mothers were 35 to 57 years old (M = 43.73, SD = 4.41), and their adolescents were 10 to 16 years old (M = 12.26, SD = 3.11), 34 boys (45.9%) and 40 girls (54.1%). Most mothers were married (n = 68, 91.9%); the rest were divorced. The mothers had been married 11 to 28 years (M = 16.88, SD = 3.76) and had up to four children (M = 2.31, SD = 0.81). Most mothers were secular (n = 64, 86.5%) and had a graduate degree (n = 66, 89.2%). Most were employed (n = 71, 95.9%) and estimated their family income as moderate (n = 63, 85.1%).

Procedure

With the permission of the administrators of mothers’ groups designated for mothers of adolescent children in Israel, group members (mothers of adolescents) were invited to participate in the study, which was presented as “Motherhood and Facebook Use” and posted to the Facebook groups for a two-month period during 2019. After digitally signing informed consent forms, those who accepted the invitation were asked to recruit their adolescent children to participate in the study with them. The participant mothers and adolescents received separate links (with a corresponding ID code) and were asked to choose a mutual ID code for identification and coordination. They then completed an online questionnaire separately and privately. Mothers completed a demographic questionnaire and the self-reporting Caregiving System Scale (CSS) and an adaptation of the Passive and Active Use Measure (PAUM), and adolescents completed the Weinberger Parenting Inventory (WPI). Participants were informed that their anonymity would be preserved throughout the study and that they could discontinue participation at any time. There was no financial incentive for participating, but we offered to share information about the study results with the participants.

Instruments

Background Questionnaire

We collected information about participants’ gender and age, mothers’ family status and education, family income level, and number of children in the family.

WPI

The WPI Hebrew version is a highly valid (e.g., Scharf et al., 2016) 50-item adolescent-report instrument (Weinberger et al., 1989) that assesses on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (strongly agree) the adolescent’s perceptions of parenting: child-centeredness (e.g., “She frequently tells me she is proud of me”; α = .82), psychological intrusiveness (e.g., “She tries to manage my life more than she should”; α = .82), permissiveness (e.g., “She lets me get away with too much”; α = .86), harsh discipline (e.g., “I feel the punishment she gives me is unfair”; α = .80), and inconsistency (e.g., “She tells me one thing and does another”; α = .84).

The harsh discipline scale was removed because of the low levels reported in the current study (M = 1.24, SD = 0.32).

PAUM

The PAUM (Gerson et al., 2017) is a 13-item self-report questionnaire. For the current study it was translated into Hebrew and adapted to examine the use of Facebook groups. Respondents were asked, “How frequently do you perform the following activities as a member in a mothers of adolescents Facebook group?” to assess active use (e.g., “Browsing the newsfeed actively, liking and commenting on posts, pictures and updates”; α = .86) and passive use (e.g., “Looking through other members’ profiles, posts, etc.”; α = .86). Answers are presented on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (never; 0% of the time) to 5 (very frequently; close to 100% of the time). Active and passive use correlated at r = .80 (p < .001) and were thus aggregated into a total score (α = .85) representing level of use of mothers’ Facebook group.

CSS

The CSS is a 20-item self-report scale (Shaver et al., 2010) that rates, on a 7-point Likert scale, the extent to which respondents agree with each item for how they feel, think, and behave when caring for others, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). The CSS has two subscales of 10 items each that assess caregiving strategies: hyperactivating (e.g., “I sometimes feel that I intrude too much while trying to help others”) and deactivating (e.g., “When I notice or realize that someone seems to need help, I often prefer not to get involved”). For each subscale, higher scores represent greater levels of hyperactivating or deactivating strategies. The Hebrew version has shown solid reliability (e.g., Reizer et al., 2014). Internal consistency for hyperactivation was .81 and for deactivation was .80.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS (ver. 25). Descriptive statistics were first calculated for the study variables. Simple correlations were calculated between the extent of Facebook use and major demographic variables, to assess the need to control for demographic variables in the data analysis. A multiple hierarchical regression was run to evaluate the extent to which the study variables predicted Facebook use. Moderation was examined with a series of multiple regressions, in which Facebook use served as the dependent variable, each of the parenting practices as an independent variable, and hyperactivation and deactivation as the moderating variables. All variables were standardized, and age and number of children were controlled for. Significant interactions were interpreted with simple-slopes analysis (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

Table 1 shows that mean Facebook use is relatively high. Hyperactivation mean is high, while deactivation is low on average, and among the various parenting practices, child-centeredness and psychological intrusiveness have the highest mean. Intercorrelations between the study variables reveal that the extent of Facebook use is positively related to permissive parenting and psychological intrusiveness. A high level of hyperactivation is negatively related to inconsistent parenting, and a high level of deactivation is positively related to inconsistent parenting and negatively related to child-centeredness. Child-centeredness is negatively related to inconsistent parenting. Permissiveness, inconsistent parenting, and psychological intrusiveness are all positively interrelated.

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations for the Study Variables (N = 74).

|

|

M (SD) |

2. |

3. |

4. |

5. |

6. |

7. |

|

1. Facebook use |

3.35 (0.72) |

-.02 |

-.13 |

.01 |

.32** |

.17 |

.56*** |

|

2. Hyperactivation |

4.92 (0.97) |

|

-.13 |

.13 |

-.01 |

-.35** |

-.21 |

|

3. Deactivation |

2.71 (0.82) |

|

|

-.25* |

.16 |

.30** |

-.05 |

|

4. Child-centeredness |

4.16 (0.54) |

|

|

|

-.22 |

-.42*** |

.17 |

|

5. Permissiveness |

2.57 (0.76) |

|

|

|

|

.39*** |

.26* |

|

6. Inconsistency |

2.59 (0.70) |

|

|

|

|

|

.39*** |

|

7. Psychological intrusiveness |

3.98 (0.61) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .0401. |

|||||||

To assess which of the study variables contributed significantly to the extent of Facebook use, simple correlations were first calculated between the extent of Facebook use and major demographic variables. Child age and gender were not significantly correlated with the extent of Facebook use. Mother’s age was negatively related to Facebook use (r = -.26, p = .026), as was the number of children (r = -.23, p = .044; coded dichotomously: 0 = one or two children, 1 = three or four children). These were unrelated to each other (r = .17, p = .151); thus, both were controlled for in further analyses.

Table 2. Multiple Hierarchical Regression for Facebook Use (N = 74).

|

|

B |

SE |

β |

|

Step 1 |

|

|

|

|

Mother’s age |

-0.03 |

0.02 |

-.17 |

|

Number of children |

-0.31 |

0.17 |

-.21 |

|

Adj. R2 |

0.06* |

||

|

Step 2 |

|

|

|

|

Mother’s age |

-0.01 |

0.02 |

-.06 |

|

Number of children |

-0.15 |

0.16 |

-.10 |

|

Hyperactivation |

0.05 |

0.08 |

.06 |

|

Deactivation |

-0.12 |

0.09 |

-.13 |

|

Child-centeredness |

-0.30 |

0.17 |

-.22 |

|

Permissiveness |

0.22 |

0.11 |

.23* |

|

Inconsistency |

-0.16 |

0.15 |

-.15 |

|

Psychological intrusiveness |

0.65 |

0.15 |

.54*** |

|

Adj. R2 |

.33*** |

||

|

F(8, 64) |

5.04*** |

||

|

f2 effect size |

.49 |

||

|

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. |

|||

A multiple hierarchical regression was calculated for the extent of Facebook use. Mother’s age and number of children were entered in the first step, and hyperactivation, deactivation, and parenting practices were entered in the second step (Table 2). Results revealed that 33% of the variance in the extent of Facebook use was explained by the variables under study, with a large effect size. Of these, significant predictors were permissive parenting and psychological intrusiveness. Higher permissiveness and greater psychological intrusiveness were related to mothers’ more frequent use of Facebook.

A series of multiple regressions were run to evaluate the moderating role of hyperactivation and deactivation in the relationship between parenting practices and Facebook use. In these, Facebook use was the dependent variable, each of the parenting practices was an independent variable, and hyperactivation and deactivation were the moderating variables. All variables were standardized, and age and number of children were controlled for. Two interactions between parenting practices and hyperactivation were found to be significant and were interpreted with simple-slopes analysis (Aiken & West, 1991).

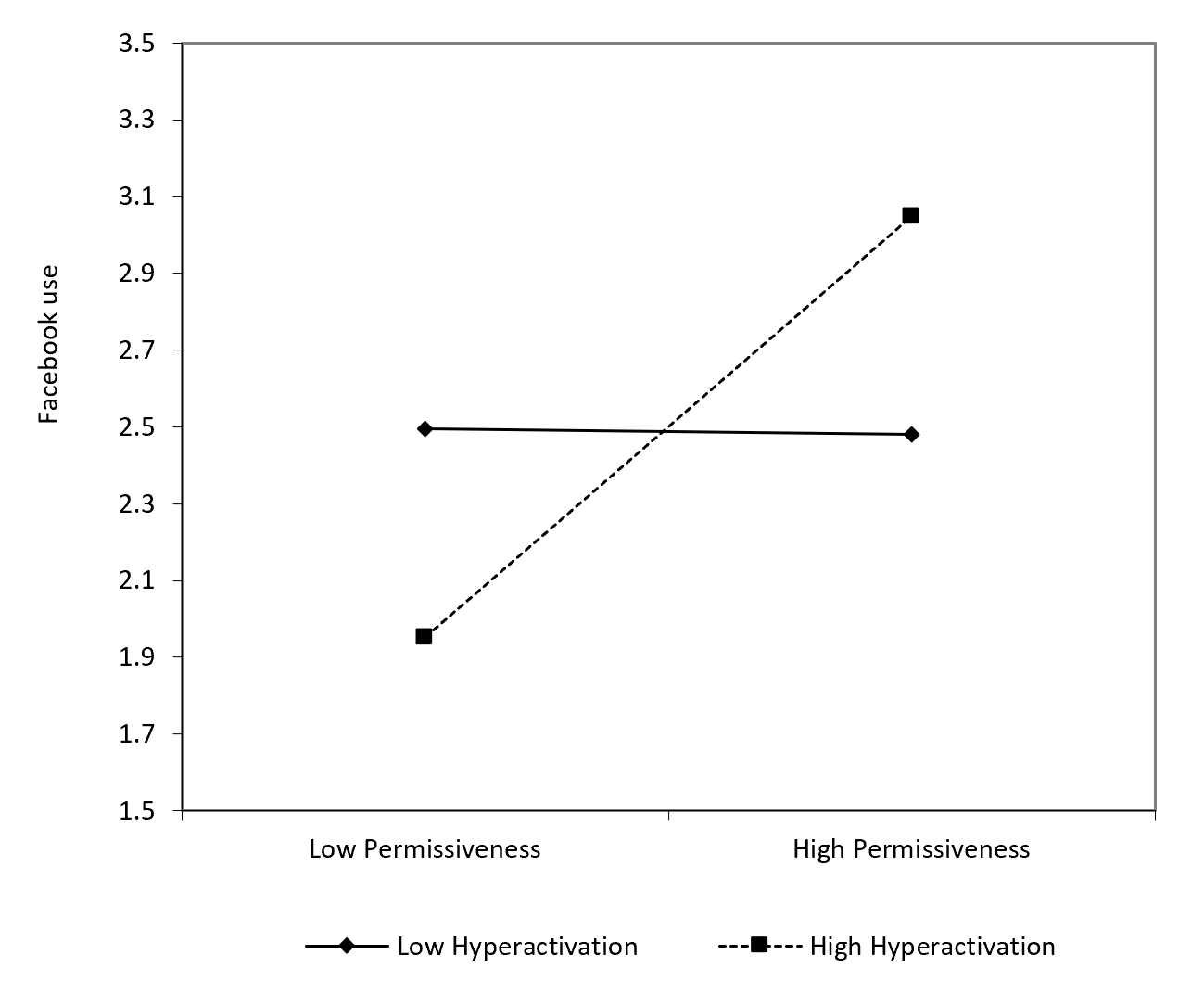

The interaction between permissiveness and hyperactivation was found to be significant in predicting Facebook use, beyond the independent and moderating variables, as well as age and number of children (B = 0.28, SE = 0.12, β = .24, p = .023). Analysis with simple slopes revealed a positive relationship between permissiveness and Facebook use among mothers who were high in hyperactivation (B = 0.55, t = 3.76, p < .001, d = 0.886; a large effect size), but no significant relationship was revealed for mothers who were low in hyperactivation (B = -0.01, t = -0.05, p = .958, d = 0.012; a small effect size; Figure 1). That is, among mothers who were high in hyperactivation, greater permissiveness was related to higher Facebook use.

Figure 1. Hyperactivation as a Moderator Between Permissiveness and Facebook Use.

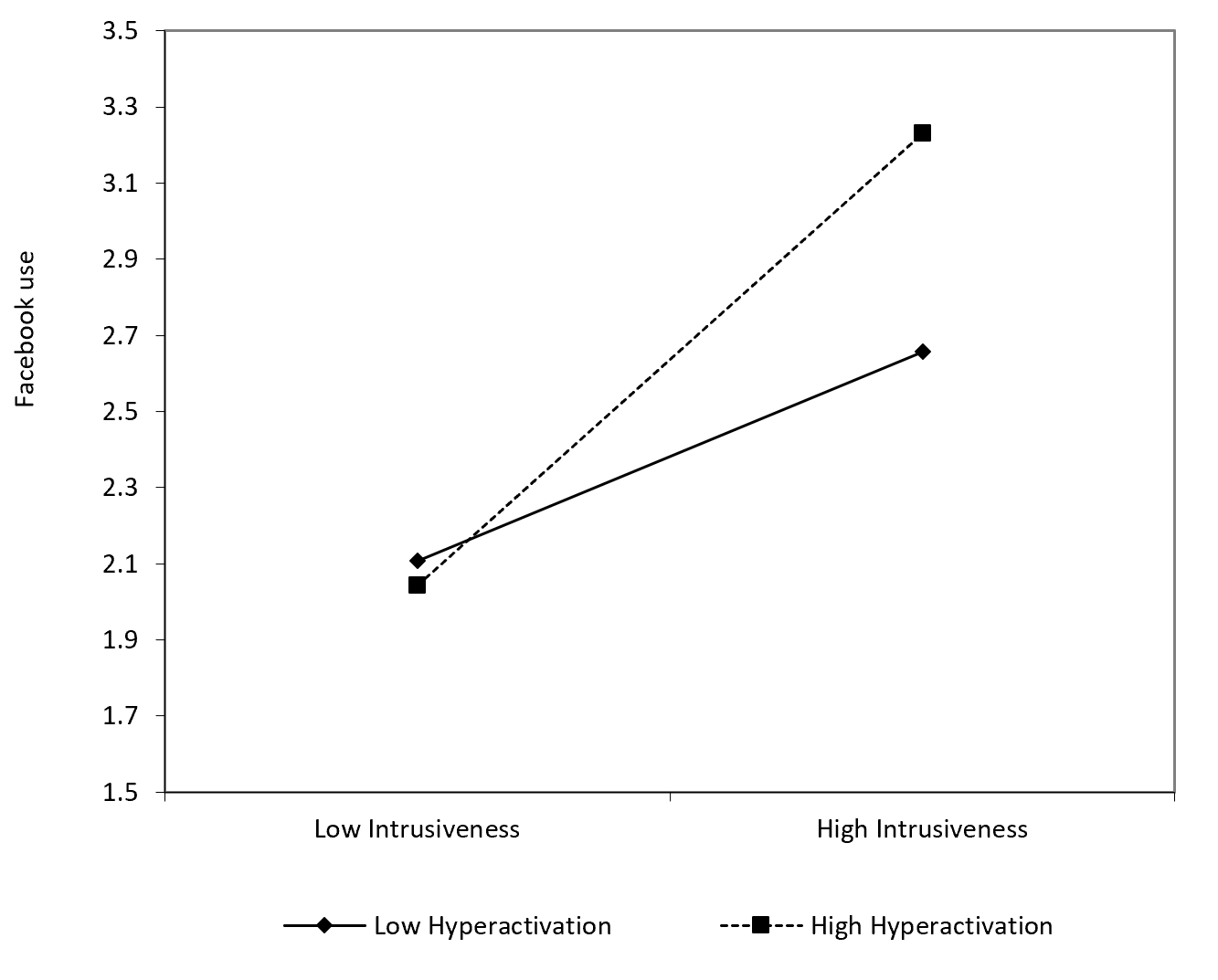

The interaction between psychological intrusiveness and hyperactivation was found to be significant in predicting Facebook use, beyond the independent and moderating variables, as well as age and number of children (B = 0.16, SE = 0.07, β = .22, p = .035). Analysis with simple slopes revealed a positive and strong relationship between psychological intrusiveness and Facebook use among mothers who were high in hyperactivation (B = 0.59, t = 4.44, p < .001, d = 1.047; a large effect size), but revealed a low positive relationship for mothers who were low in hyperactivation (B = 0.27, t = 2.31, p = .024, d = 0.544; a moderate effect size; Figure 2). That is, among mothers who were high in hyperactivation, greater psychological intrusiveness was related to higher Facebook use, to a greater extent than among mothers who were low in hyperactivation.

Figure 2. Hyperactivation as a Moderator Between Psychological Intrusiveness and Facebook Use.

Discussion

In the last two decades, Facebook has become a central social media platform that enables billions of people to share information, to follow other people‘s activities and friends, and to get support, help, and comfort regarding multiple aspects of life (e.g., Doty & Dworkin, 2014). Parents, particularly mothers, use Facebook either actively or passively to cope with the experiences they face as parents (e.g., Laws et al., 2019). Yet there is a lack of research on the characteristics of mothers who become involved in Facebook groups, particularly the characteristics of their parenting of their adolescent children. The current study examined Facebook use, parenting practices, and caregiving strategies among Israeli mothers of adolescents.

We hypothesized that higher levels of hyperactivation and deactivation caregiving strategies would be associated with mothers’ higher involvement in Facebook groups. Mothers who use ineffective caregiving strategies (hyperactivation\deactivation) might experience more emotional difficulties regarding their parenting (Shaver et al., 2010), which might encourage them to seek relief for their distress in social media (Chang, 2019; Hart et al., 2015; Flynn et al., 2018; Oldmeadow et al., 2013). However, we found no significant associations between caregiving strategies and Facebook use. There could be several reasons for this result. The caregiving system includes a broad diversity of care behaviors that caregivers adapt to benefit care receivers throughout the caregivers’ life experiences (George & Solomon, 2008; Shaver et al., 2010). The type of care offered is influenced by the personality of both the caregiver and the recipient, (e.g., extroversion), their emotional states (e.g., depression), sociocultural contexts and ideologies (e.g., who deserves to be cared for), and who the recipient is of the care being proffered (child, partner, other) (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Thus, individuals who score high on the use of deactivation caregiving strategies (i.e., attachment avoidant individuals) might display a more restrained use of Facebook groups due to their low extroversion (Hart et al., 2015). However, when such people are experiencing emotional distress (e.g., mothering an adolescent child), due to the impersonal communication that Facebook provides, they might be more likely to become involved in Facebook groups, which promote highly intrusive behavior (Flynn et al., 2018).

The individual’s utilization of hyperactivation strategies is associated with insecurities as to the effectiveness of the care they provide and their chronically activated caregiving (Shaver et al., 2010). This may in turn lead to higher Facebook use by such people as they seek a sense of belonging and to be well-liked (Chang, 2019; Hart et al., 2015; Oldmeadow et al., 2013). However, their anxieties and insecurities concerning their motherhood might bring them to practice social comparison and experience judgment regarding their motherhood (Coyne et al., 2017), causing them to lower their involvement and choose a different path to cope with their parental challenges.

Finally, it is important to point out that the general caregiving strategies scale (CSS), which was used here to assess caregiving strategies among mothers of adolescents, does not assess specific strategies regarding caring for an adolescent child and thus would not translate to parental behavior such as involvement in mothers’ Facebook groups rather than to involvement in general groups.

We further hypothesized that higher levels of permissive, psychologically intrusive, and inconsistent parenting practices and lower levels of child-centered parenting behavior would be associated with the mothers’ higher involvement in Facebook groups. We found that higher permissiveness and greater psychological intrusiveness were indeed related to more frequent use of Facebook groups by the participants. One explanation for this result could be that the difficulty exerting parental authority over their child, given the nature of reduced parental authority during a child’s adolescence (Scharf, 2014) and their high permissiveness as a parenting practice, caused them strain in the “real world” that could have increased their involvement in Facebook groups (Lee et al., 2017) in order to seek information, share emotions and difficulties about motherhood, and receive support from other parents (Doty & Dworkin, 2014). In doing so, comparing themselves to other mothers, sharing and assessing their parenting could have intensified their emotional difficulties and conflicts with their adolescent children (Lipu & Siibak, 2019), prompting further negative parenting behavior (Collins & Laursen, 2006; Shaver et al., 2010). Regarding intrusiveness, the high involvement of mothers in Facebook groups itself might have been experienced and reported by the adolescent participants here as intrusive parenting behavior (Chalklen & Anderson, 2017; Sorensen, 2016).

We also explored hyperactivation and deactivation caregiving strategies as moderators of the relationship between parenting style and level of involvement in mothers’ Facebook groups, and we found that among mothers who were high in hyperactivation, greater psychological intrusiveness and permissiveness were related to higher Facebook use to a greater extent than among mothers who were low in hyperactivation. High hyperactivation caregiving strategies keep caregiving behaviors chronically activated and are ineffective (Shaver et al., 2010). They include hypervigilance and an exaggerated appraisal of the adolescent child’s needs expressed as negative parenting behavior (e.g., intrusiveness) incompatible with the adolescent child’s needs (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). In the end, such strategies may exacerbate parents’ emotional difficulties (Shaver et al., 2010). Hence, higher intrusive and permissive behavior may increase parental strain (Scharf, 2014), driving mothers to seek information and support from other mothers using mothers’ Facebook groups (Doty & Dworkin, 2014; Lee et al., 2017). Mothers who are not attuned to their adolescents’ needs (i.e., high hyperactivation caregiving) also might become involved in Facebook groups in a way that the adolescent experiences as more intrusive and\or permissive than mothers who care for their adolescent child more effectively (low hyperactivation). Mothers characterized by more effective caregiving strategies (i.e., low hyperactivation) might find alternative platforms to cope with difficulties in their motherhood, thus reporting lower involvement in mothers’ Facebook groups.

Limitations and Future Studies

The current study employed a cross-sectional design. Hence, it is impossible to distinguish whether parenting practices and caregiving strategies reported were the result of mothers’ Facebook involvement or whether difficulties in parenting an adolescent child increase Facebook involvement. In addition, of course adolescents may be overly critical of the parenting they experience, which could be reflected in their reports, and their evaluations also could be influenced by their individual personalities.

Parental stress and perceived difficulties in the parent–adolescent relationship were not assessed and should be addressed in future research. Further, future research should also address other aspects of parenting (e.g., parental competence, parental strain, and “intensive parenting”), parents’ personality characteristics (e.g., social comparison tendencies and neuroticism), and include different methods of assessment (e.g., interviews, observations). Finally, the current study focused on a relatively small sample of mothers and adolescents from Israeli society. Therefore, generalization of the results might be limited.

Authors’ Note

There was no funding for the current research. Data were collected in a manner consistent with ethical standards for the treatment of human subjects, and all participants signed informed consent forms to confirm their participation.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2021 Goldberg, Grinshtain, Amichai-Hamburger