Adolescents’ intention and willingness to engage in risky photo disclosure on social networking sites: Testing the prototype willingness model

Vol.15,No.2(2021)

Researchers state that around 80-90% of adolescents share photos on social networking sites (SNS) (Anderson & Jiang, 2018), which may have positive and negative consequences on adolescents’ health. However, it is still unclear why adolescents engage in such kind of behaviour. Thus, the aim of this study is to find out if the Prototype Willingness Model (PWM) can explain adolescents’ risky photo disclosure on SNS. To reach this aim, a survey study was conducted among a sample of adolescents (N = 586; Mage = 14.65, SDage = 1.36; 56.9% female). Students were asked to fill in hard copy questionnaires, assessing the factors of reasoned (intention) and reactive (willingness) pathways of the PWM and risky photo disclosure on SNS. In order to test adolescents’ intention and willingness of risky photo disclosure on SNS, structural equation modelling (SEM) analysis was performed using Mplus. The results of the hypothesized model showed acceptable model fit: χ² = 3950.467, p < .001; RMSEA = .064, 90% CI [.062, .067], CFI = .935, TLI = .931. According to the results, we can state that adolescents’ risky photo disclosure on SNS is better explained by the factors of the reasoned pathway (intention) than the reactive pathway (willingness).

Prototype willingness model; risky behaviour online; photo disclosure; adolescents

Ugnė Paluckaitė

Department of Psychology, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania

Ugnė Paluckaitė is a PhD Candidate at the Department of Psychology in Vytautas Magnus University. Before PhD studies, she earned her Master of School Psychology degree from Vytautas Magnus University. She currently works as an assistant at Vytautas Magnus University and as a psychologist at Vytautas Magnus University Psychology Clinic and Radviliškis community house. Her research interests include adults and adolescents online and offline self-disclosure, communication on the Internet, risky behaviour on the Internet.

Kristina Žardeckaitė-Matulaitienė

Department of Psychology, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania

Kristina Žardeckaitė-Matulaitienė is a professor at the Department of Psychology in Vytautas Magnus University. Before PhD studies, she earned her Master of Health Psychology degree from Vytautas Magnus University. She currently works as a professor at Vytautas Magnus University and as a psychologist at Vytautas Magnus University Psychology Clinic. Her research interests include effectiveness of psychological interventions; psychological aspects of risky behaviour (drug usage, risky sexual behaviour, risky driving, emigration), interpersonal communication research (interpersonal relationships, verbal and nonverbal communication, relationship satisfaction), gender issues in psychology research (gender similarities and differences, gender stereotypes), research in religiosity/spirituality, counselling psychology research.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Anderson, M., & Jiang, J. (2018). Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

Armenta, B. E., Whitbeck, L. B., & Gentzler, K. C. (2016). Interactive effects within the prototype willingness model: Predicting the drinking behavior of indigenous early adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000104

Branley, D. B., & Covey, J. (2018). Risky behavior via social media: The role of reasoned and social reactive pathways. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.09.036

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Choi, G. Y., & Behm-Morawitz, E. (2018). Teach me about yourself(ie): Exploring selfie-takers’ technology usage and digital literacy skills. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 7(3), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000130

Christofides, E., Muise, A., & Desmarais, S. (2012). Hey mom, what’s on your Facebook? Comparing Facebook disclosure and privacy in adolescents and adults. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(1), 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611408619

Dorsch, I., & Ilhan, A. (2016). Photo publication behavior of adolescents on Facebook. In K. Knautz & K. S. Baran (Eds.), Facets of Facebook: Use and users (pp. 45–71). De Gruyter Saur. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110418163-003

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. W. W. Norton & Co.

Frater, J., Kuijer, R., & Kingham, S. (2017). Why adolescents don’t bicycle to school: Does the prototype/willingness model augment the theory of planned behaviour to explain intentions? Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 46(Part A), 250–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2017.03.005

Gámez-Guadix, M., Borrajo, E., & Almendros, C. (2016). Risky online behaviours among adolescents: Longitudinal relations among problematic Internet use, cyberbullying perpetration, and meeting strangers online. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(1), 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.013

Gerrard, M., Gibbons, F. X., Houlihan, A. E., Stock, M. L., & Pomery, E. A. (2008). A dual-process approach to health risk decision making: The prototype willingness model. Developmental Review, 28(1), 29–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2007.10.001

Gibbons, F. X., & Gerrard, M. (1995). Predicting young adults’ health risk behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(3), 505–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.3.505

Gibbons, F. X., Gerrard, M., Blanton, H., & Russell, D. W. (1998). Reasoned action and social reaction: Willingness and intention as independent predictors of health risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1164–1180. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1164

Gibbons, F. X., Gerrard, M., Cleveland, M. J., Wills, T. A., & Brody, G. (2004). Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(4), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517

Grigutytė, N., Raižienė, S., Pakalniškienė, V., & Povilaitis, R. (2018). Lietuvos vaikų naudojimosi internetu 2010 ir 2018 metais ypatumų palyginimas [The comparison of Lithuanian children usage of the Internet from 2010 to 2018]. Psichologija, 580, 57–71. https://doi.org/10.15388/Psichol.2018.3

Houghton, S., Lawrence, D., Hunter, S. C., Rosenberg, M., Zadow, C., Wood, L., & Shilton, T. (2018). Reciprocal relationships between trajectories of depressive symptoms and screen media use during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(11), 2453–2467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0901-y

Huang, G. C., Soto, D., Fujimoto, K., & Valente, T. W. (2014). The interplay of friendship networks and social networking sites: Longitudinal analysis of selection and influence effects on adolescent smoking and alcohol use. American Journal of Public Health, 104(8), e51–e59. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302038

Kofoed, J., & Larsen, M. C. (2017). A snap of intimacy: Photo-sharing practices among young people on social media. First Monday, 21(11). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v21i11.6905

Krasnova, H., & Veltri, N. F. (2011). Behind the curtains of privacy calculus on social networking sites: The study of Germany and the USA. In Wirtschaftsinformatik Proceedings 2011 (pp. 891–900). Association for Information Systems. https://aisel.aisnet.org/wi2011/26

Krasnova, H., Veltri, N. F., & Günther, O. (2012). Self-disclosure and privacy calculus on social networking sites: The role of culture. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 4(3), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-012-0216-6

Lithuanian Ministry of Education and Science. (2018). Lietuva. Švietimo būklės apžvalga 2018. Gera mokykla [Lithuania. The review on education in Lithuania. A good school]. ŠAC.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the internet: The perspective of European children. Full findings. EU Kids Online.

Malik, A., Dhir, A., & Nieminen, M. (2016). Uses and gratifications of digital photo sharing on Facebook. Telematics and Informatics, 33(1), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.06.009

Moore, S., & Gullone, E. (1996). Predicting adolescent risk behavior using a personalized cost-benefit analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 25(3), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01537389

Moreno, M. A., Christakis, D. A., Egan, K. G., Brockman, L. N., & Becker, T. (2012). Associations between displayed alcohol references on Facebook and problem drinking among college students. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(2), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.180

Mubarak, S., & Mubarak, M. A. (2016). Online self-disclosure and wellbeing of adolescents: A systematic literature review [Paper presentation]. Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Adelaide, Australia. https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.03527

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus user's guide (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

Paluckaitė, U., & Žardeckaitė-Matulaitienė, K. (2017). Risks and consequences of adolescents’ online self-disclosure. In Conference Proceedings: The Future of Education (pp. 179–181). LibreriaUniversitaria.

Paluckaitė, U., & Žardeckaitė-Matulaitienė, K. (2019). A systematic literature review on psychosocial factors of adolescents’ online self-disclosure. New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences, 6(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.18844/prosoc.v6i1.4154

Sherman, L. E., Payton, A. A., Hernandez, L. M., Greenfield, P. M., & Dapretto, M. (2016). The power of the Like in adolescence: Effects of peer influence on neural and behavioral responses to social media. Psychological Science, 27(7), 1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616645673

Steinberg, L., & Cauffman, E. (1996). Maturity of judgment in adolescence: Psychosocial factors in adolescent decision making. Law and Human Behavior, 20(3), 249–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01499023

Stevens, R., Dunaev, J., Malven, E., Bleakley, A., & Hull, S. (2016). Social media in the sexual lives of African American and Latino youth: Challenges and opportunities in the digital neighborhood. Media and Communication, 4(3), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i3.524

Sung, Y., Lee, J.-A., Kim, E., & Choi, S. M. (2016). Why we post selfies: Understanding motivations for posting pictures of oneself. Personality and Individual Differences, 97, 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.032

Todd, J., Kothe, E., Mullan, B., & Monds, L. (2016). Reasoned versus reactive prediction of behaviour: A meta-analysis of the prototype willingness model. Health Psychology Review, 10(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.922895

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2011). Online communication among adolescents: An integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.020

Van Duijvenvoorde, A. C., Peters, S., Braams, B. R., & Crone, E. A. (2016). What motivates adolescents? Neural responses to rewards and their influence on adolescents’ risk taking, learning, and cognitive control. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.037

Van Gool, E., Van Ouytsel, J., Ponnet, K., & Walrave, M. (2015). To share or not to share? Adolescents’ self-disclosure about peer relationships on Facebook: An application of the prototype willingness model. Computers in Human Behavior, 44, 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.036

Walrave, M., Ponnet, K., Van Ouytsel, J., Van Gool, E., Heirman, W., & Verbeek, A. (2015). Whether or not to engage in sexting: Explaining adolescent sexting behaviour by applying the prototype willingness model. Telematics and Informatics, 32(4), 796–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.03.008

Walrave, M., Van Ouytsel, J., Ponnet, K., & Temple, J. R. (2018). Sharing and caring? The role of social media and privacy in sexting behaviour. In M. Walrave, J. Van Ouytsel, K. Ponnet, & J. R. Temple (Eds.), Sexting: Motives and risk in online sexual self-presentation (pp. 1–17). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71882-8_1

White, R. M. B., Knight, G. P., Jensen, M., & Gonzales, N. A. (2018). Ethnic socialization in neighborhood contexts: Implications for ethnic attitude and identity development among Mexican‐origin adolescents. Child Development, 89(3), 1004–1021. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12772

Williams, A. L., & Merten, M. J. (2008). A review of online social networking profiles by adolescents: Implications for future research and intervention. Adolescence, 43(170), 253–274.

Xie, W., & Kang, C. (2015). See you, see me: Teenagers’ self-disclosure and regret of posting on social network site. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 398–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.059

Youn, S. (2005) Teenagers’ perceptions of online privacy and coping behaviors: A risk–benefit appraisal approach. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 49(1), 86–110. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4901_6

Yuen, C. Y. M. (2013). Ethnicity, level of study, gender, religious affiliation and life satisfaction of adolescents from diverse cultures in Hong Kong. Journal of Youth Studies, 16(6), 776–791. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2012.756973

Editorial Record

First submission received:

February 3, 2020

Revisions received:

May 18, 2020

October 16, 2020

March 8, 2021

Accepted for publication:

March 13, 2021

Editor in charge:

Michel Walrave

Introduction

Researchers in social and psychological sciences, state that adolescents’ online behaviour, is one of the most important concerns, gaining a lot of scientists’ attention (Branley & Covey, 2018; Walrave et al., 2018). The growing rate of researchers’ interest in adolescents’ online behaviour, is related to their extensive and growing usage of the Internet. The report of Pew Research Centre (Anderson & Jiang, 2018) states that almost every adolescent is using the Internet daily. Also, 45% of them use the Internet almost constantly. Thus, according to such an enormous usage, scientists state that nowadays adolescents are developing more in online settings, rather than in offline settings (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2016; Van Duijvenvoorde et al., 2016; Yuen, 2013).

One of the most popular online activities among teenagers, is using social networking sites (SNS) (Van Gool et al., 2015). On SNS, teenagers can communicate with others and share their opinions, attitudes, feelings or any other information about themselves. Thus, it is possible to state that adolescents’ activities on SNS, are highly related to self-disclosure. Online self-disclosure can be verbal and non-verbal (Paluckaitė & Žardeckaitė-Matulaitienė, 2017). One of the most popular non-verbal types of online self-disclosure, is sharing photos (Dorsch & Ilhan, 2016; Kofoed & Larsen, 2017). Around 80-90% of adolescents share their photos on SNS (Anderson & Jiang, 2018; Grigutytė et al., 2018). This is because it can help teenagers to express and experiment with their identity and it is one of the most important goals at the period of adolescence (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2016; Houghton et al., 2018; Van Gool et al., 2015). On the other hand, sharing photos online can be risky and cause negative consequences, such as cyberbullying (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2016; Livingstone et al., 2011), the feelings of guilt or regret (Christofides et al., 2012), conflicts with parents or peers and problems at school (Youn, 2005). As a result, it is said, that any kind of adolescents’ self-disclosure on SNS, is a risky behaviour (Van Gool et al., 2015; Walrave et al., 2018). Moreover, it is also stated that sharing risky photos on SNS is risky too (Sherman et al., 2016). However, in this article, only the photos including inappropriate content, (a person who is not fully dressed or age forbidden behaviour is shown) (Williams & Merten, 2008) is called as a risky photo disclosure on SNS.

It is essential to mention that the majority of studies, analysing online photo disclosure, are based on young adults (mostly university or college students) (Paluckaitė & Žardeckaitė-Matulaitienė, 2019). Thus, the analysis of adolescents’ risky photo disclosure online, is still scarce. Besides, researchers state that there is no theoretical explanation of adolescents’ risky photo disclosure on social networking sites (Houghton et al., 2018; Malik et al., 2016; S. Mubarak & M. A. Mubarak, 2016). It is said, that the Prototype willingness model (PWM) can explain adolescents’ risky online behaviour (Branley & Covey, 2018; Van Gool et al., 2015; Walrave et al., 2015). The recent study of Branley and Covey (2018) shows promising results in explaining risky behaviour on social media, while implementing PWM. This study, therefore, aims to find out if the PWM can explain adolescents’ risky photo disclosure on SNS. As a result, this study focuses specifically upon photo disclosure online.

Adolescents’ Risky Photo Disclosure on SNS

Adolescents’ self-disclosure on SNS can be defined as the information which the user shares on his/her profile, or during communication with others (Krasnova et al., 2012; Krasnova & Veltri, 2011). As previously mentioned, online self-disclosure can be verbal and non-verbal (Paluckaitė & Žardeckaitė-Matulaitienė, 2017). Verbal online self-disclosure refers to sharing opinion, feelings and facts of oneself, whereas non-verbal self-disclosure can be defined as sharing visual information, such as photos or videos online. Furthermore, the combination of verbal and non-verbal disclosure, may also occur in videos posted online, for example, vlogs and stories (Paluckaitė & Žardeckaitė-Matulaitienė, 2017). More importantly, sharing photos online, is an everyday activity among adolescents today (Anderson & Jiang, 2018). According to Xie and Kang (2015), around 91% of adolescents share photos online. Another report organised by the Pew Research centre (Anderson & Jiang, 2018) found that 99% of adolescents have posted at least one photo online. Thus, according to this rapid engagement in photo disclosure on SNS, the phenomenon becomes a more important factor of their psychosocial development. According to the popularity of photo disclosure online, this study is limited to only sharing pictures online.

There are different kinds of photos that adolescents share online. Williams and Merten (2008) distinguish appropriate and inappropriate photos. Appropriate photos are those in which the person is fully clothed (i.e., his or her naked body or its intimate parts are not visible) and are not engaged in any potentially risky behaviour. Inappropriate photos are usually associated with the display of a naked body (such as a person without a T-shirt) and the display of potentially risky behaviours such as carrying a weapon, fights, and use of psychoactive substances (Williams & Merten, 2008). According to Dorsch and Ilhan (2016), the majority of adolescents (around 90%) are likely to post their portrait photos online. Other authors (e.g., Anderson & Jiang, 2018; Sung et al., 2016) also state that the most popular type of photos teenagers share online, is what is known as a “selfie”. Taking and posting 'selfies', in general, is called to be a prosocial behaviour, as it helps adolescents to gain skills in media literacy (Choi & Behm-Morawitz, 2018) and to maintain personal relationships (Sung et al., 2016). However, adolescents are also likely to share risky or inappropriate photos on SNS. For example, the study of Dorsch and Ilhan (2016) shows that 98% of the adolescents, state that they would never share photos where their naked body is shown. Hence, we may predict that in general teenagers have a negative attitude towards risky photo disclosure on SNS. However, the study of Stevens and colleagues (2016) shows that around 25-33% of adolescents are likely to post or share provocative or sexual content photos online. Another study of Dorsch and Ilhan (2016) shows that 19% of adolescents are likely to share photos where they are smoking and 15% of them shared photos where they are drinking alcohol or are posing with it. A simulation by Sherman et al. (2016) with photos of teenagers published on the Internet, showed that when teenagers saw appropriate or inappropriate photos with a lot of 'likes', they were also more likely to like those photos. Besides, young people often publish different kinds of content, portraying risky behaviour, which may lead to their peers’ involvement in such kind of behaviour (Huang et al., 2014). Moreover, it is stated that following or observing the content (mostly photos) of alcohol on Facebook or Myspace, increases adolescents’ likelihood of engaging in problematic alcohol use (Moreno et al., 2012).

In this study, risky photo disclosure on SNS is defined as (by Dorsch & Ilhan, 2016; Kofoed & Larsen, 2017):

- Sharing a photo of non-verbal aggression (e.g., showing middle finger);

- Sharing photos where a teenager is smoking or holding any type of cigarette;

- Sharing photos where a teenager is drinking or holding a cup/glass of alcohol;

- Sharing partly nude photos (e.g., wearing a swimsuit);

- Sharing nude photos;

- Sharing a photo where physical or sexual contact (e.g., hug, kiss) is visible.

Prototype Willingness Model

Importantly, adolescence is a critical period for the development of a person’s identity, curiosity and experimentation with different values, beliefs and behaviour which occurs at this particular age (Erikson, 1950; Yuen, 2013). This is why, adolescence is the period when the likelihood of engaging in risky behaviour is the highest and such behaviour online, is not acceptable. It is said that adolescents’ cognitive immaturity, is the main factor of their engagement in risky behaviours (Steinberg & Cauffman, 1996; White et al., 2018). In other words, adolescents do not perceive the possible consequences of their behaviour (Moore & Gullone, 1996). Thus, adolescents may also not be aware that their disclosure on SNS can be risky (Christofides et al., 2012). Moreover, even if adolescents know that they may experience any negative consequences from their behaviour, they still may participate in an activity, until they learn from their experience (Christofides et al., 2012; Moore & Gullone, 1996). Thus, the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991) in general, is used when explaining risky adolescents' behaviour. Basically, TPB states that risky behaviour is accurately planned and reasoned, while the person rationally weighs the costs and the benefits of the behaviour. However, it is also stated that adolescents’ risky behaviour is not always planned (Gerrard et al., 2008; Gibbons et al., 2004).

It is said that the prototype/willingness model (PWM), suggested by Gibbons & Gerrard (1995), as an alternative to the TPB, can better explain risky adolescents’ behaviour (Gerrard et al., 2008; Gibbons et al., 1998). PWM is founded on the basis of social context, where risky adolescents’ behaviour mostly occurs, stating that adolescents may engage in risky behaviours not only because they plan or intent to do so, but also because they are willing to engage in a particular behaviour (Gerrard et al., 2008; Gibbons et al., 1998). According to the PWM, there are two ways to decide how to behave. One way, is a rational or reasoned way (based on planned actions), and the other, is a reactive way (based on situational factors). Adolescents’ risky behaviour is thought to be adequately explained by the prototype/willingness model. Unlike other theories or models of risky behaviour, the prototype/willingness model recognises the importance of social context in the manifestation of risky behaviour (Armenta et al., 2016).

PWM was created to explain risky behaviours of adolescents, such as smoking or alcohol use (Gibbons et al., 1998). This model, like TPB, states that attitudes and subjective peer norms influence one’s intention to act in one way or another. However, it is argued that subjective peer norms in TPB are measured as prescriptive norms (what a person would do) and in PWM as descriptive norms (what a person does) (Frater et al., 2017). Valkenburg & Peter (2011) states that peer influence has a significant impact on adolescents' behaviour online. As a result, we may predict that PWM, including injunctive and descriptive peer norms in understanding teenagers’ behaviour, is an important characteristic which can help to explain risky behaviour in adolescence.

Besides, according to Frater et al. (2017), the PWM model must include not only the intention to behave, (as in TPB) but also the willingness to behave. This means that PWM recognises that adolescents' decisions, especially those involving risky behaviours, are made when adolescents find themselves in certain situations. For example, being in a peer group or being able to consume alcohol, when they have to decide how they will behave. In this context, Gibbons and others (1998) state that in such situations, adolescents are more likely to consider what they are currently prepared to do, rather than what they plan to do. That is, the willingness to act and the intention to behave differ by the main principle of decision making. This includes the reactive decision making (behavioural willingness) and the deliberate decision making (intention to behave) (Frater et al., 2017). The meta-analysis on PWM of Todd and colleagues (2016) shows that both, intention and willingness are important factors of adolescents’ risky behaviour. Authors conclude that intention to engage in behaviour explains 15.6% of the variance while willingness adds statistically significant 4.9% to the prediction of the behaviour.

Recently, PWM has been used to explain some of the risky behaviours engaged by teenagers on the SNS (Branley & Covey, 2018; Van Gool et al., 2015). For example, a study by Walrave and others (2015) showed that subjective peer norms have a more considerable influence on the adolescents' intention to send sexting messages to their peers. Moreover, the results of this study showed that the willingness and attitudes towards such behaviour also influence teenagers’ sexting on the Internet. A recent study of Branley and Covey (2018) provides a possible explanation of non-verbal disclosure on social media by adopting the PWM. Authors analysed sharing embarrassing photos, current location (by text or special social media feature), engaging in and sharing pranks or stunts and sexual communication with strangers (e.g., sharing sexual photos). The results of their study show that variables of reactive pathway add an additional explanation of willingness by 6.2%. Authors also mention, that future research should focus on intention, not only on willingness, while explaining risky behaviour on social media. Thus, in this study, both, intention and willingness are taken into account.

Considering that PWM adequately explains the risky behaviour engaged by teenagers in real and virtual environments, it can be expected that it can also explain teenagers' risky photo self-disclosure on SNS, as it was already partly proven by Branley and Covey (2018). In other words, we can expect that the PWM may adequately explain the risky photo disclosure of teenagers on SNS. Thus, according to the information provided above, the aim of this study is to find out if PWM can explain adolescents’ risky photo disclosure on social networking sites. According to the information provided above, the PWM of adolescents’ risky photo disclosure is proposed.

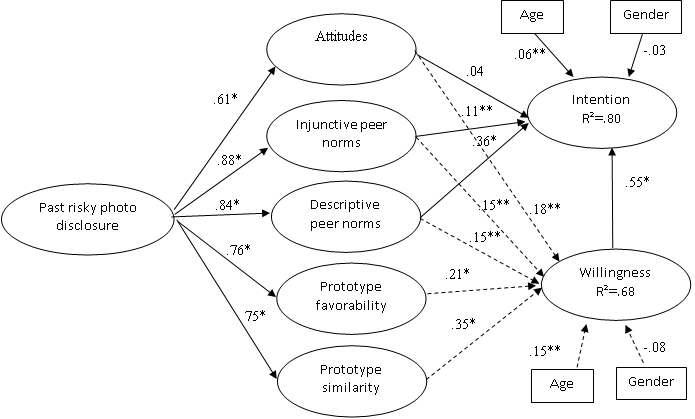

Figure 1. The Proposed Model of Adolescents' Risky Photo Disclosure on SNS.

Note. *p ˂ .001, **p ˂ .05. Reasoned pathway →; reactive pathway ⇢.

Figure 1 presents the adjusted model of PWM on adolescents’ risky photo disclosure on SNS. The model is based on the basics of PWM suggested by Gerrard and others (2008). It is important to mention, that this model, is extended by adding two important control variables: age and gender.

According to this model, we can assume that past risky photo disclosure is an important factor, related to intention, subjective peer norms and prototype similarity and favourability. Moreover, adolescents’ intention to share risky photos on SNS depends on the attitudes towards risky photo disclosure on SNS, injunctive and descriptive peer norms of risky photo disclosure on SNS and past risky photo disclosure. The adolescents’ willingness to engage in risky photo disclosure on SNS depends on a few factors. These are: the attitudes towards risky photo disclosure on SNS, the injunctive and descriptive peer norms of risky photo disclosure on SNS, and past risky photo disclosure on SNS.

Method

Participants

Five hundred and eighty-six students from different Lithuanian schools participated in this study. Their aged varied from 13 to 17 years (Mage = 14.65, SDage = 1.36). The majority of them were females (56.9%). Data was collected in November 2019.

Procedure

The study sample is based on randomly selected schools across Lithuania. Schools were selected using a one stage cluster sampling, where two selection criteria were adopted. The first criterion is a type of school: primary school, pro-gymnasium, and gymnasium. In sum, there are 836 schools (348 primary schools, 134 pro-gymnasiums, 354 gymnasiums) in Lithuania where adolescents between ages of 12 to 18 years old are studying. The second criterion is geographical area: the biggest cities of Lithuania (more than 80.000 inhabitants), smaller cities (more than 3.000 inhabitants), and towns or villages (less than 3.000 inhabitants). According to Lithuanian Ministry of Education and Science (2018), 45.3% of 12–17 years adolescents are studying in the biggest cities of Lithuania, 37.6% of them in smaller cities, and 17.1% in towns or villages. This data shows that almost half of Lithuanian adolescents are studying in the biggest Lithuanian cities, so, it was decided to double the number of chosen schools in those cities. Adopting the cluster sampling criteria and using a random number generator, 12 schools were chosen. This included 6 different types of schools from the biggest cities, 3 different types of schools from smaller cities, and 3 different types of schools from the town/village. After the schools were selected, their administration representatives were contacted. When the agreement from the school was collected, the date and time of the study were discussed.

Active parental consents were collected before the study. Only those students whose parents agreed to their participation, could take part in the study. The study was conducted during the lessons, when students had to fill in the hard-copy questionnaires. After they completed the questionnaires, the students were given sweets.

Measures

Past Risky Photo Disclosure on SNS

Past risky photo disclosure on SNS, was measured by 6-item subscale of self-developed Adolescents’ Photo Disclosure Scale on SNS. The created scale, consisted of 10-items, measuring both, appropriate (4 items) and risky photo disclosure (6 items) on SNS. However, according to the goal of the study, only the subscale of risky photo disclosure was chosen. The subscale presents six types of risky photos descriptions: sharing a photo of non-verbal aggression (e.g., showing middle finger), sharing photos where teen is smoking or holding any type of cigarette, sharing photos where teen is drinking or holding a cup/glass of alcohol; sharing partly nude photos (e.g., wearing swimsuit); sharing nude photos; sharing a photo where sexual contact is visible. For example, “in the last two months, on the SNS which I use most often, I've shared a photo where I smoke or pose with any type of cigarette”. Adolescents were asked to rate on each statement, how often in the past two months, had they shared different kinds of photos on SNS. Adolescents were asked to rate each statement on how often (from 1 = “never” to

5 = “very often”), in the past two months, have they shared different kinds of photos on SNS.

As the scale was self-developed and not pre-tested, exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory (CFA) factor analysis using Mplus were conducted. The results of the EFA showed that there are two factors and they present a sufficient fit to the data: RMSEA = .059, 90% CI [.044, .074], CFI = .986, TLI = .975, SRMR = .051 (χ² = 78.240, df = 26, p ˂ .001). CFA confirmed a two-factor model: RMSEA = .067, 90% CI [.054, .080], CFI = .976, TLI = .968 (χ² = 123.179, df = 34, p ˂ .001). According to the given results from the EFA and CFA, it could be stated that a self-developed scale of adolescents' photo disclosure on SNS has two subscales: neutral and risky photo disclosure. Cronbach’s α of the scale is .77 (neutral photo self-disclosure subscale’s Cronbach’s α = .69 and risky photo self-disclosure subscale’s Cronbach’s α = .84). In this study, only the subscale of risky photo self-disclosure was used.

PWM Measures

Further in this section the measures of PWM variables are presented. These measures are based on the studies of Walrave et al. (2015) and Van Gool et al. (2015).

Attitudes Towards Risky Photo Disclosure

Attitudes towards risky photo disclosure, was measured by a 6-item scale, based on an imaginary situation. Each item was measured by the risky photo disclosure subscale. Participants were asked to evaluate each situation on a semantic differential scale, which ranged from inappropriate to appropriate. An example from this scale is: “Sharing photos on SNS, where mine and another person’s sexual contact is visible”. Cronbach’s α of the scale is .88.

Injunctive Peer Norms

Injunctive peer norms were measured by a 6-item scale, which required the participants to rate if their significant peers would agree if they shared risky photos on SNS. An example from this scale is “Your peers, who are important for you, would agree that on SNS you share a photo where yours and another person’s sexual contact is visible: would totally disagree (1) – would totally agree (5)”. Participants were asked about each type of photo measured in the risky photo disclosure subscale. Cronbach’s α of the scale is .87.

Descriptive Peer Norms

Descriptive peer norms were measured by a 6-item scale, which required the participants to rate how often, in their opinion, significant peers share risky photos on SNS. An example from this scale is “How often your peers, who are important to you, on SNS, share photos where his/her and another person’s sexual contact (e.g., hug, kiss) is visible: never (1) – very often (5)”. Cronbach’s α of the scale is .86.

Prototype Favourability

Prototype favourability was measured by a 6-item scale, which required the participants to rate how likeable it is that a typical person of their age would share risky photos on SNS. An example from this scale is “How likeable is typical your age person who shares photos on SNS where his/her and another person’s sexual contact (e.g., hug, kiss) is visible: totally not (1) – totally yes (5)”. Cronbach’s α of the scale is .87.

Prototype Similarity

Prototype similarity was measured by a 6-item scale, which required the participants to rate how similar they are to their peers who share risky photos on SNS. An example from this scale is “How similar are you to your peer who shares photos on SNS where his/her and another person’s sexual contact (e.g., hug, kiss) is visible: totally not similar (1) – totally similar (5)”. Cronbach’s α of the scale is .85.

Intention

Intention was measured by a 6-item scale, which required the participants to rate their intention to share risky photos on SNS in the upcoming two months. An example from this scale is “Do you intend, in the upcoming 2 months, to share photos on SNS where yours and another person’s sexual contact is visible: no intended at all (1) – totally intended (5)”. Cronbach’s α of the scale is .81.

Willingness

Willingness was measured by a 6-item scale, which required the participants to rate their willingness to share risky photos on SNS in the upcoming two months. An example from this scale is “Imagine that you are using SNS right now and you see how your peers are sharing photos where his/her and another person’s sexual contact (e.g., hug, kiss) is visible. Will you share a photo where yours and another person’s sexual contact is visible?: totally disagree (1) – totally agree (5)”. Cronbach’s α of the scale is .86.

Socio-Demographic Questions

Adolescents were also asked about their age and gender. These variables are used as control variables in this study.

Results

Data analysis

The proposed model was analysed using Mplus 7.4 (L. K. Muthén & B. O. Muthén, 2012). The model fit was assessed by Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). Model fit was measured based on: RMSEA < .05, CFI, TLI > .95 presents a good model fit; RMSEA .05–.08, CFI, TLI > .90 presents an acceptable model fit (Brown, 2015; Little, 2013).

The results of the main model’s constructs are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. The Means and Standard Deviations of the Main Constructs of PWM.

|

PWM constructs |

M |

SD |

|

Past behaviour |

7.62 |

3.18 |

|

Attitudes |

31.08 |

13.57 |

|

Descriptive peer norms |

10.34 |

4.86 |

|

Injunctive peer norms |

10.19 |

5.23 |

|

Prototype favourability |

11.23 |

5.80 |

|

Prototype similarity |

8.39 |

4.79 |

|

Intention |

8.19 |

3.64 |

|

Willingness |

8.43 |

3.99 |

The results of the model are presented in the next section.

SEM results

The results of SEM are presented in Figure 2. The proposed adolescents’ risky photo disclosure on SNS model shows an acceptable model fit: χ² = 3950.467, p < .001; RMSEA = .064, 90% CI [.062, .067], CFI = .935, TLI = .931.

The study shows that past risky photo disclosure on SNS is statistically significantly related to all mediated variables of PWM. Past risky behaviour has the biggest impact on injunctive peer norms (β = .88). According to the results, it can be stated that adolescents’ intention to engage in risky photo disclosure on SNS is statistically significantly explained by subjective peer norms and the willingness to engage in such behaviour, where willingness (β = .55) has the biggest impact. However, attitudes do not have a statistically significant impact on intention. The independent variables of this reasoned pathway, explain intention by 80%. Thus, those adolescents who experience more social pressure from their peers, and those who are more willing to share risky photos on SNS, are more likely to have a higher intention to reveal risky photos on social networks.

Figure 2. PWM of Adolescents’ Risky Photo Disclosure on SNS.

Note. *p ˂ .001, **p ˂ .05. Reasoned pathway →; reactive pathway ⇢.

This study also shows that adolescents’ willingness to engage in risky photo disclosure on SNS is statistically significantly explained only by attitudes, injunctive and descriptive peer norms, prototype favourability and similarity, where prototype similarity (β = .35) has the biggest impact. The independent variables of this reasoned pathway explain willingness by 68%. Thus, those adolescents who have a more positive attitude towards risky photo disclosure, experience more social pressure from their peers. Also, those who perceive the prototype to be positive and resembles themselves, are more willing to reveal risky photos on social networks.

Moreover, the results also show that only age statistically significantly and positively predicts, both intention and willingness to engage in risky photo disclosure on SNS. Thus, older adolescents have a greater intention and are more willing to engage in such behaviour.

Discussion

The results of the study show that PWM can explain risky photo disclosure of adolescents on SNS. Moreover, it is essential to mention that PWM variables explain adolescents’ intention to share risky photos on SNS better than willingness. As it was already mentioned, the study of Branley and Covey (2018) shows that willingness is a good predictor of sharing embarrassing and sexual photos on SNS, however, Branley and Covey also highlighted that intention was not included in their study and suggested that this should be investigated in future research. Thus, the current study included a measure of intention. The results expand the explanation of adolescents’ risky photo disclosure on SNS, showing that intention is an important predictive factor of such behaviour. The same results were found in the study of Van Gool and colleagues (2015): intention can better explain adolescents’ disclosure than willingness. However, it is important to address that Van Gool and colleagues (2015) analysed verbal self-disclosure on SNS. Therefore, it is possible to state that intention can explain both, verbal and non-verbal, adolescents’ disclosure on SNS better than willingness. According to Gibbons and others (2004), it is possible that with age, adolescents’ ability to weigh costs and benefits of risky behaviour might increase. Thus, it could be stated that the sample of adolescents in this study are more cognitively mature. Also, they are more able to make reasoned decisions than reactive ones. Moreover, the age range of the sample in this study, is in the range of middle and late adolescence. Thus, it may also explain why PWM variables explain adolescents’ intention to share risky photos on SNS better than willingness (Gibbons et al., 2004).

However, at the same time, willingness is also an essential explanation of adolescents’ risky photo disclosure online. This is because the variables of the reactive pathway explain more than 50% of willingness. It is also important to mention that willingness is the strongest predictor of adolescents’ intention to share risky photos online. This study demonstrates that all variables of the reactive pathway of PWM can explain adolescents’ willingness to engage in risky photo disclosure. The strongest predictor of adolescents’ willingness to engage in risky photo disclosure is prototype similarity. This means that the more similar an adolescent feels to a peer, who is disclosing risky photos online, the more willing he/she is to disclose his/her risky photos on social networking sites. These results differ from the study of Branley and Covey (2018), where similarity didn’t have a statistically significant impact on adolescents’ willingness to share embarrassing photos online. The results may differ, because authors used a different method to measure prototype similarity (participants were asked to rate the prototype’s personality traits). According to Gibbons and Gerrard (1995), if the similarity is high, then the willingness to engage in risky behaviour will also be higher. Similarly, to the study of Branley and Covey (2018), prototype favourability was the strong predictor of adolescents’ willingness to disclose risky photos online. Thus, it may be stated that not only personal attitudes and subjective peer norms have an important role in adolescents’ behaviour online, but the image/prototype of a typical discloser online also drives adolescents’ behaviour.

This study shows that two main factors correlate, which are age and gender, also important characteristics when defining adolescents’ intention and willingness to engage in risky photo disclosure on social networking sites. This study demonstrates that only age positively predicts both adolescents’ intention and willingness to engage in risky photo disclosure online. This resulted in older adolescents’ to be intending on and willing to engage in risky photo disclosure on social networking sites. As it was briefly discussed above, according to the PWM, it is expected that younger adolescents should be more willing and older ones should be more intended to engage in risky behaviours (Gibbons et al., 2004). However, according to the study of Branley and Covey (2018), willingness becomes less critical in adulthood. Thus, it may be stated that sharing risky photos online is more of a common behaviour amongst older adolescents.

Despite the meaningful results presented above, this study has some limitations. Firstly, it was found that attitudes were not related to adolescents’ intention to engage in risky photo disclosure online. This might be due to the measurement bias, as in this study, it was measured by a single semantic differential item. Thus, further research should address this limitation by adjusting more reliable measure of attitudes. Another significant limitation is that this study does not cover other essential control variables. An example of this, is personal characteristics, which might be important in explaining the mechanism of adolescents’ risky photo disclosure on social networking sites. Thus, it would be meaningful to expand the model with significant personal or social characteristics, in order to have a more thorough understanding of adolescents’ online behaviour. Moreover, research of adolescents’ online self-disclosure also shows that there might be cultural differences among such kind of behaviour (Krasnova et al., 2012). According to this, future studies may consider including the variable of culture, while analysing adolescents’ risky photo disclosure online.

Conclusion

The results of this study show that PWM can explain adolescents’ risky photo disclosure on SNS. To be more precise, the results show that adolescents’ risky photo disclosure on SNS is better explained by the factors of reasoned pathway (intention) than the reactive pathway (willingness). However, this study also reveals that both reasoned and reactive pathways of adolescents’ risky behaviour online, should be considered in order to have a better explanation of such behaviour.

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by Vytautas Magnus University Science Fund for Research Cluster Projects (VMU Rector’s order No. 435a, May 31, 2019; Projects registration No. P-S-19-06).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2021 Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace