A social identity perspective on the effect of social information on online video enjoyment

Vol.14,No.4(2020)

To date, videos are often presented on social media platforms where they are accompanied by social information in the form of user comments. Research suggests that this social information can alter viewers’ video enjoyment. The present study aimed to learn more about two factors that may enhance this effect by conducting a 2x2 between-subjects experiment with a control group (N = 290, Mage = 20.82, SDage = 2.49) in the Netherlands. First, we investigated the role that the source of social information (i.e., in-group vs. out-group) plays in the effect of social information. Second, we explored how writing a comment while watching a video (i.e., commenting vs. no commenting) may alter the effect of the source of social information. Results indicated that social information created by in-group members is more influential than social information created by out-group members. However, writing a comment did not increase viewers’ susceptibility to the effects of social information. These results are discussed in light of the social identity framework, leading to new insights into what may bolster the effect of social information on video enjoyment when individuals watch videos presented on social media.

social information; user comments; enjoyment; social identification; information source

A. Marthe Möller

University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

A. Marthe Möller (MSc, University of Amsterdam) is a PhD candidate at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (University of Amsterdam).

Rinaldo Kühne

University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Dr. Rinaldo Kühne (PhD, University of Zurich) is an assistant professor at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (University of Amsterdam).

Susanne E. Baumgartner

University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Dr. Susanne E. Baumgartner (PhD, University of Amsterdam) is an assistant professor at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (University of Amsterdam).

Jochen Peter

University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Prof. dr. Jochen Peter (PhD, University of Amsterdam) is a full professor at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (University of Amsterdam).

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596

Billig, M., & Tajfel, H. (1973). Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 3(1), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420030103

Chae, B. G., Dahl, D. W., & Zhu, R. J. (2017). “Our” brand's failure leads to “their” product derogation. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(4), 466–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2017.04.002

Christ, T. J. (2007). Experimental control and threats to internal validity of concurrent and nonconcurrent multiple baseline designs. Psychology in the Schools, 44(5), 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20237

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Hayes, A. F. (2018). PROCESS [Macro]. http://afhayes.com/introduction-to-mediation-moderation-and-conditional-process-analysis.html

Hixson, T. K. (2006). Mission possible: Targeting trailers to movie audiences. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 14(3), 210–224. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jt.5740182

Hogg, M. A., & Hains, S. C. (1996). Intergroup relations and group solidarity: Effects of group identification and social beliefs on depersonalized attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.295

Hogg, M. A., & Turner, J. C. (1985). Interpersonal attraction, social identification and psychological group formation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 15(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420150105

Hsueh, M., Yogeeswaran, K., & Malinen, S. (2015). “Leave your comment below”: Can biased online comments influence our own prejudicial attitudes and behaviors? Human Communication Research, 41(4), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12059

Isart Digital. (2016). Nobody Nose Cleopatra. [Animated Short Film]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Tc7PMuHTJQ

Khan, M. L. (2017). Social media engagement: What motivates user participation and consumption on YouTube? Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.024

Lin, C. A., & Xu, X. (2017). Effectiveness of online consumer reviews: The influence of valence, reviewer ethnicity, social distance and source trustworthiness. Internet Research, 27(2), 362–380. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-01-2016-0017

Mackie, D. M. (1986). Social identification effects in group polarization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(4), 720–728. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.4.720

Mackie, D. M., Worth, L. T., & Asuncion, A. G. (1990). Processing of persuasive in-group messages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(5), 812–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.812

McCroskey, J. C., Richmond, V. P., & Daly, J. A. (1975). The development of a measure of perceived homophily in interpersonal communication. Human Communication Research, 1(4), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1975.tb00281.x

McCroskey, L. L., McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (2006). Analysis and improvement of the measurement of interpersonal attraction and homophily. Communication Quarterly, 54(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370500270322

Möller, A. M., Baumgartner, S. E., Kühne, R., & Peter, J. (2019). The effects of social information on the enjoyment of online videos: An eye tracking study on the role of attention. Media Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1679647

Möller, A. M., & Kühne, R. (2019). The effects of user comments on hedonic and eudaimonic entertainment experiences when watching online videos. Communications, 44(4), 427–446. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2018-2015

Oh, J., & Sundar, S. S. (2020). What happens when you click and drag: Unpacking the relationship between on-screen interaction and user engagement with an anti-smoking website. Health Communication, 35(3), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1560578

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers' perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191

Oliver, M. B., Weaver, J. B., III, & Sargent, S. L. (2000). An examination of factors related to sex differences in enjoyment of sad films. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 44(2), 282–300. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4402_8

Pirlott, A. G., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2016). Design approaches to experimental mediation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 66, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.09.012

Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., & Jans, L. (2013). A single‐item measure of social identification: Reliability, validity, and utility. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(4), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12006

Reichelt, J., Sievert, J., & Jacob, F. (2014). How credibility affects eWOM reading: The influences of expertise, trustworthiness, and similarity on utilitarian and social functions. Journal of Marketing Communications, 20(1–2), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2013.797758

Reicher, S. D., Spears, R., & Postmes, T. (1995). A social identity model of deindividuation phenomena. European Review of Social Psychology, 6(1), 161–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779443000049

Ren, Y., Harper, F. M., Drenner, S., Terveen, L., Kiesler, S., Riedl, J., & Kraut, R. E. (2012). Building member attachment in online communities: Applying theories of group identity and interpersonal bonds. MIS Quarterly, 36(3), 841–864. https://doi.org/10.2307/41703483

Samu, S., & Bhatnagar, N. (2008). The efficacy of anti-smoking advertisements: The role of source, message, and individual characteristics. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 13(3), 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.326

Slater, D. M., Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2015). Message variability and heterogeneity: A core challenge for communication research. Annals of the International Communication Association, 39(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2015.11679170

Spencer, S. J., Zanna, M. P., & Fong, G. T. (2005). Establishing a causal chain: Why experiments are often more effective than mediational analyses in examining psychological processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 845–851. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.845

Stone-Romero, E. F., & Rosopa, P. J. (2008). The relative validity of inferences about mediation as a function of research design characteristics. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 326–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428107300342

Suckfüll, M. (2010). Films that move us: Moments of narrative impact in an animated short film. Projections, 4(2), 41–63. https://doi.org/10.3167/proj.2010.040204

Sundar, S. S. (2004). Theorizing interactivity’s effects. The Information Society, 20(5), 385–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240490508072

Tajfel, H. (1970). Experiments in intergroup discrimination. Scientific American, 223(5), 96–103. www.jstor.org/stable/24927662

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Social Science Information, 13(2), 65–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847401300204

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology, 33, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.33.020182.000245

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1(2), 149–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420010202

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (2nd ed., pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall Publishers.

Terry, D. J., & Hogg, M. A. (1996). Group norms and the attitude-behavior relationship: A role for group identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(8), 776–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296228002

Turner, J. C. (1982). Towards a cognitive redefinition of the social group. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Social identity and intergroup relations (pp. 15–40). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249222.n46

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Basil Blackwell Ltd.

Turner, J. C., Oakes, P. J., Haslam, S. A., & McGarty, C. (1994). Self and collective: Cognition and social context. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 454–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205002

Turner, J. C., & Reynolds, K. J. (2012). Self-categorization theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 399–417). Sage.

Van Noort, G., Voorveld, H. A. M., & van Reijmersdal, E. A. (2012). Interactivity in brand web sites: Cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses explained by consumers’ online flow experience. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26(4), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2011.11.002

Waddell, T. F., & Bailey, E. (2019). Is social television the “anti-laugh track?” testing the effect of negative comments and canned laughter on comedy reception. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8(1), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000154

Waddell, T. F., & Sundar, S. S. (2017). #thisshowsucks! The overpowering influence of negative social media comments on television viewers. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 61(2), 393–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2017.1309414

Walther, J. B., DeAndrea, D., Kim, J., & Anthony, J. C. (2010). The influence of online comments on perceptions of antimarijuana public service announcements on YouTube. Human Communication Research, 36(4), 469–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01384.x

Wang, Z., Walther, J. B., & Hancock, J. T. (2009). Social identification and interpersonal communication in computer-mediated communication: What you do versus who you are in virtual groups. Human Communication Research, 35(1), 59–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2008.01338.x

Winter, S., Krämer, N. C., Benninghoff, B., & Gallus, C. (2018). Shared entertainment, shared opinions: The influence of social TV comments on the evaluation of talent shows. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 62(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2017.1402903

Wirth, W., Hofer, M., & Schramm, H. (2012). Beyond pleasure: Exploring the eudaimonic entertainment experience. Human Communication Research, 38(4), 406–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2012.01434.x

Xu, Q., & Sundar, S. S. (2016). Interactivity and memory: Information processing of interactive versus non-interactive content. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 620–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.046Yanovitzky, I., Stewart, L. P., & Lederman, L. C. (2006). Social distance, perceived drinking by peers, and alcohol use by college students. Health Communication, 19(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc1901_1

Editorial Record

First submission received:

January 21, 2020

Revisions received:

July 4, 2020

September 4, 2020

October 16, 2020

Accepted for publication:

October 20, 2020

Editor in charge:

David Smahel

Introduction

Increasingly, audiences use social media platforms such as YouTube to access online videos. These platforms typically present videos together with video (dis)likes and user comments. As video (dis)likes and user comments can indicate how other viewers experience videos, scholars refer to video (dis)likes and user comments as social information (e.g., Hsueh et al., 2015; Möller et al., 2019). Scholars have started to investigate how social information alters viewers’ enjoyment when they watch online videos to understand how entertainment experiences arise in response to online media content. Their research indicates that negative social information, in particular, can decrease viewers’ video enjoyment (Möller et al., 2019; Waddell & Bailey, 2019; Waddell & Sundar, 2017).

To date, research on the effects of social information on video viewers’ entertainment experiences has mainly focused on how the valence of social information (i.e., its positivity or negativity) alters viewers’ video enjoyment. However, the valence effect of social information on video enjoyment may be altered by specific characteristics of the social information, for example whether social information is written by others whom viewers perceive as in-group members or by others whom viewers perceive as out-group members. According to the literature on social influence, the extent to which a receiver acknowledges the source of information as a member of the same group determines the influence that the information has on the receiver (Terry & Hogg, 1996; Turner, 1982; Turner et al., 1994). Hence, this study aims to learn more about how the source of social information (i.e., in-group versus out-group) alters the effect of social information on video enjoyment. Moreover, as the effect of the source of information is explained by social identification with that source (Terry & Hogg, 1996; Turner, 1982; Turner et al., 1994), we also test the mediating role of social identification in this effect.

Another factor that may alter the influence of social information on video enjoyment is whether video viewers write their own comment in response to online videos. Khan (2017) notes that there are two different ways in which individuals can use YouTube, namely through passive consumption (e.g., reading comments or watching videos) or active participation (e.g., writing comments). Extant research suggests that active participation on websites can increase individuals’ focus on the content of those websites (e.g., Oh & Sundar, 2020; Van Noort et al., 2012; Xu & Sundar, 2016). Applied to the case of social information about online videos, this means that writing one’s own comment in response to a video may increase viewers’ focus on the social information. This may make them more susceptible not only to the influence of social information itself, but also to the influence of the source of social information. This study aims to learn more about this by investigating the role of writing one’s own comment.

The Source of Social Information

In response to the rising popularity of online videos presented on social media, researchers have studied how enjoyment emerges when individuals watch videos and read user comments. They found that negative social information about a video can decrease the enjoyment that viewers experience in response to that video (Möller et al., 2019; Waddell & Bailey, 2019; Waddell & Sundar, 2017). Waddell and Bailey (2019) as well as Waddell and Sundar (2017) suggest that when video viewers see social information and notice that others disliked a video, they apply a bandwagon heuristic stating that if other viewers disliked a video, they should do so as well. Similarly, Winter et al. (2018) argued that viewers’ video experiences might be altered through a conformity effect whereby viewers adjust their opinions about a video to the opinion expressed by the group.

The notion that video viewers adjust their own video evaluations so that they fit in with the group gives rise to the question of whether video viewers’ tendency to adjust their evaluation depends on the source of social information. A theoretical perspective on the role of the source of information is offered by literature on social identity and the Social Categorization Theory (Tajfel, 1974; Turner et al., 1987). This literature has been used by scholars to investigate various types of user-generated information, such as movie reviews and product reviews (e.g., Chae et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2012), and it is useful to study the current topic of social information about online videos as well. Social Categorization Theory (Turner et al., 1987) suggests that individuals are more likely to conform to information provided by people whom they regard as members of their in-group than to information that is provided by people who are not part of the same group (Terry & Hogg, 1996; Turner, 1982; Turner et al., 1994).

Empirical support for the notion that the source of information plays an important role for individuals’ susceptibility to the influence of this information has been found in multiple studies (Mackie, 1986; Mackie et al., 1990; Samu & Bhatnagar, 2008; Terry & Hogg, 1996; Yanovitzky et al., 2006). For example, Mackie (1986) found that, during a discussion about the usage of standardized tests in universities, individuals’ attitudes changed toward the opinion expressed by other discussants only if those individuals regarded themselves and the other discussants as members of the same group. In a study about smoking cessation, Samu and Bhatnagar (2008) found that individuals were more influenced by information about an anti-smoking advertisement provided by one’s friends (i.e., in-group) than by information provided by strangers (i.e., out-group). In the case of social information about online videos, this implies that video viewers’ enjoyment is influenced more by social information provided by a source that belongs to the same group as the viewers than by social information provided by a source that belongs to a different group.

For a more thorough explanation of the role of groups, scholars have used the concept of social identification (Reicher et al., 1995; Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner et al., 1987). Social identification is central to Social Categorization Theory and it is based on the notion that people’s self-concept consists of two different types of identity. First, personal identity refers to individual characteristics that people use to describe themselves (e.g., motivated, optimistic, or patient). The second type of identity is social identity. Individuals’ social identity is determined by the groups, or social categories, to which they feel that they belong. One’s social identity can be, for example, woman, democrat, or dentist (Reicher et al., 1995; Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner et al., 1987). However, while individuals can base their social identity on meaningful factors such as their profession, one’s social identity can also be based on arbitrary groups. Literature on the minimal-group paradigm indicates that individuals can base their social identity on their membership of a group even if they know that they were assigned to this group based on random or meaningless criteria (Billig & Tajfel, 1973; Tajfel, 1970; Tajfel et al., 1971).

Social Categorization Theory primarily focuses on social identity and it deals with the antecedents and consequences of social identification: the act of positioning oneself within a specific group while distancing oneself from other groups, and attaching value to one’s membership of this group, leading a person to adopt this group membership as a part of her social identity (Reicher et al., 1995; Tajfel, 1974, 1982; Turner et al., 1987, 1994; Turner & Reynolds, 2012). When studying the effect of viewers’ shared group membership with the source of social information on video enjoyment, social identification is an important concept. Research indicates that as individuals identify with a group of people more, they are more susceptible to the influence of that group (Mackie, 1986; Mackie et al., 1990; Samu & Bhatnagar, 2008; Terry & Hogg, 1996; Yanovitzky et al., 2006). Individuals’ social identification with other people, in turn, is determined by their awareness of a common social category membership with those people (Turner, 1982; Turner et al., 1987, 1994). In sum, individuals who are exposed to information provided by people of whom it is clear that they belong to their in-group (either because they have something meaningful in common or merely because they were assigned to be in the same group) are likely to identify with the creators of that information more. This, in turn, makes these individuals more susceptible to the influence of the information.

In line with the literature on social identity, scholars studying social information and video enjoyment explored the role of social identification. Walther et al. (2010) and Winter and colleagues (2018) conducted studies on the effect of user comments in which they also measured viewers’ social identification with the commenters. They found that while the valence of social information affected viewers’ video evaluations, it did so more among video viewers who experienced a stronger sense of social identification with the commenters. Although this provides some support for Social Categorization theory in this context, these studies only found evidence for the notion that when viewers identify with the source of social information more strongly, they are more susceptible to the influence of that social information. However, as these studies did not manipulate the source of social information, it remains unclear whether social information created by in-group members alters viewers’ enjoyment more than social information created by out-group members. Moreover, it is unclear whether an effect of the source of social information on video enjoyment is mediated by social identification as indicated by the literature on social identity.

In sum, we pose the following hypotheses (note that H1 is a replication of earlier research that is necessary for H2 and H3):

H1: Video viewers who are exposed to negative social information experience less enjoyment than video viewers who are not exposed to negative social information.

H2: Video viewers who are exposed to negative social information provided by a source that belongs to the same group experience less enjoyment than video viewers who are exposed to negative social information provided by a source that does not belong to the same group.

H3: The effect of a shared group membership with the source of negative social information on video enjoyment is mediated by social identification: (a) When video viewers belong to the same group as the source of negative social information, they identify more with this source compared to when they do not belong to the same group. (b) As video viewers’ identification with the source of negative social information increases, they experience less enjoyment.

Writing One’s Own Comment

When individuals watch videos presented on social media platforms, the way in which they use these platforms can vary. Investigating YouTube usage, Khan (2017) notes that in addition to passive consumption (e.g., watching videos and reading comments), video viewers can actively participate on the platform, for example by writing their own comments. These different ways of using social media platforms may be relevant for how video viewers respond to social information. Specifically, writing one’s own comment in response to a video may increase video viewers’ focus on the social information that was created by other viewers. Support for this notion is provided by Winter et al. (2018). In their study, Winter and his colleagues (2018) asked participants to watch an episode of a talent show on television. While they were watching the episode, participants could read comments about the episode written by others and write their own comments on a tablet. The researchers found that the valence of the comments that participants were exposed to influenced the valence of the comments that participants wrote themselves, indicating that participants paid attention to the comments written by others. This implies that when viewers write their own comment to express their opinion about a video, they first focus on the comments that were written by previous viewers to acquire a sense of how others evaluated the video. As a consequence, they may be more susceptible to the influence of social information.

Additional empirical support for the idea that individuals who actively participate on websites are focused on the content presented on these websites and are more susceptible to its influence can be found in the literature on persuasive communication. Several studies investigated how various forms of active participation on websites can alter how people perceive the content of these websites (e.g., Oh & Sundar, 2020; Van Noort et al., 2012; Xu & Sundar, 2016). Overall, the studies suggest that when individuals are actively interacting with the content of a website as opposed to only passively reading it, their focus on this content increases, making them more susceptible to its influence. For individuals watching online videos, this implies that writing a comment in response to a video can make viewers more susceptible to the influence of its social information. We thus hypothesize:

H4: Video viewers who write a comment in response to a video that is accompanied by negative social information experience less enjoyment than video viewers who do not write a comment in response to a video that is accompanied by negative social information.

In addition to increasing video viewers’ susceptibility to the effect of social information, writing one’s own comment may also impact viewers’ social identification with the source of social information. In their study on social identification in the context of online communities, Ren et al. (2012) proposed that focusing people’s attention on a group and its activities increases their identification with the group. As stated above, writing one’s own comment in response to a video is likely to increase viewers’ focus on the social information created by previous viewers. Similarly, writing one’s own comment can draw viewers’ attention to the source of the social information, making them more susceptible to the influence of that source. Based on this, it seems plausible that the effect of a shared group membership with the source of social information on social identification is stronger for individuals who write their own comment in response to a video. We hypothesize:

H5: The effect of a shared group membership with the source of negative social information on viewers’ identification with the source of negative social information is moderated by writing one’s own comment: The effect is stronger for video viewers who write their own comment than for video viewers who do not write their own comment.

Method

The hypotheses of this study were tested with a 2 (social information source: in-group vs. out-group) x 2 (writing one’s own comment: commenting vs. no commenting) between-subjects experimental design with a control group. The data collection for this study started in January 2019 and was completed in March 2019. The authors received Institutional Review Board approval for this study by the ethical committee of their university.

Participants

We ran a power analysis using G*power version 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007), to determine the required sample size needed to detect an effect with ηp2 = .035. The results of this analysis (α error probability = 0.05, 1-β error probability = 0.8, numerator df = 1, number of groups = 5) indicated that a sample size of 219 participants was required. Participants in the experiment were Communication Science and Psychology students of a large Dutch university who were recruited through the website of the university laboratory. As data from student populations may be prone to problems that lead to exclusion of a sometimes large number of participants, we recruited a total of 296 students. Because participants’ prior attitudes toward the video used as stimulus material in our study could bias the results, only the data of participants who had not seen the video before partaking in the study were included in the analyses. Hence, the data of six participants were excluded because these participants had already seen the video. This resulted in a final sample size of 290 participants (Mage = 20.82, SDage = 2.49, 22.1% male) who were randomly assigned to one of five conditions, namely the in-group/no commenting condition (n = 54), the in-group/commenting condition (n = 59), the out-group/no commenting condition (n = 57), the out-group/commenting condition (n = 60), or the control condition (n = 60).

Procedure

After consenting to participate, participants were led to a cubicle with a desktop computer. Participants in the experimental conditions first answered a number of questions about their media usage. These questions were part of the manipulation of group membership (see the description of the stimulus material provided below). Afterwards, an online video and user comments were presented to the participants in the experimental conditions. While watching the video, participants in the commenting conditions were asked to write their own comment about the video in a textbox below the comments supposedly written by other viewers. Participants in the control condition only watched the video presented on a webpage that did not depict any comments. After watching the video, all participants filled in a survey.

Upon completion of the study, participants received a reward of their choice (i.e., either €5 or extra course credits). Once the data collection for the study was completed, all participants were debriefed with an email.

Stimulus Material and Manipulation of the Independent Variables

All participants watched the same 6-minute animated short film titled Nobody Nose Cleopatra (Isart Digital, 2016) which is publicly available on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Tc7PMuHTJQ). The selection of an animated short film as the single stimulus material for this study was based on three reasons. First, by using an animated short film as the stimulus material for our study, we follow previous studies that used similar videos as their stimulus material (i.e., Möller et al., 2019; Möller & Kühne, 2019). Using an animated short film as stimulus material in this study ensured comparability with extant research on the effects of social information. Second, an animated short film is suitable stimulus material to study the effects of social information on video enjoyment. Unlike episodes of television series used in other studies (e.g., Waddell & Bailey, 2019; Waddell & Sundar, 2017; Winter et al., 2018), animated short films are not aired on television on a regular basis and do not feature famous actors that participants may know. So, participants are unlikely to hold preexisting attitudes towards it based on what they have seen on television or on celebrities that are featured in it (Suckfüll, 2010). Third, animated short films are frequently watched on YouTube and numerous videos of animated short films are available on the platform. The specific video that was used as the stimulus material for this study presents a narrative which characterizes the genre of animated short films. By using one specific video that is representative for animated short films in general, we increase the external validity of our study (Slater et al., 2015).

Figure 1. Social Information Presented to Participants in the Experimental Conditions.

In addition to watching the video, participants in the four experimental conditions saw the same four comments displayed on the left side of the video (see Figure 1). All four comments referred to the video negatively. Negative comments were used because previous studies consistently showed that they can reduce video enjoyment, while the results regarding positive social information are less consistent (Möller et al., 2019; Waddell & Bailey, 2019; Waddell & Sundar, 2017).

Social Information Source

Participants in the in-group source conditions saw user comments that were manipulated to look as if they were written by people who belonged to the same group. Participants in the out-group source conditions saw comments that were manipulated to look as if they were written by members of a different group. The distinction between groups was based on a short test that participants completed at the start of the study. In this test, participants stated their opinion about several statements about media usage (e.g., “When I feel tired, I prefer watching television over reading a book.”). They were led to believe that, based on their opinions about these statements, they can be categorized as either ‘horizontal’ or ‘vertical’ media content processors. Unknown to the participants, all participants were informed that they were horizontal content processors, regardless of the answers they had provided. Subsequently, participants in the in-group source conditions were told that they would watch the video together with some comments written by other people with the same, horizontal content processing style. Instructions for participants in the out-group source conditions said that the comments were written by people who have a different content processing style, namely a vertical content processing style. When participants watched the video, a short text above the comments repeated whether the people who wrote the comments belonged to the same group or to a different group of content processors.

The manipulation of group membership was based on previous studies that manipulated group membership using a minimal-group paradigm (i.e., Billig & Tajfel, 1973; Tajfel, 1970; Wang et al., 2009). For example, Wang et al. (2009) asked participants to indicate in which month they were born and then told them that based on this information, they could be categorized into specific groups using Egyptian Zodiac. We followed this approach and asked participants to provide some information about themselves which we then allegedly used to categorize them into a specific group. On the one hand, we aimed for participants to believe that they would be categorized into distinct groups. On the other hand, we also aimed for participants to believe that they would be categorized into groups that did not differ in terms such as status or likeability. In addition, we aimed for the manipulation to be logically related to the cover story of our study which was that the study aimed at learning more about individuals’ experiences of online videos.

To achieve these goals, we adjusted the approach used by Wang et al. (2009) and asked participants to provide information about their media usage by answering eight short questions. We told them that based on this information, they could be categorized into one of two groups of media content processors, either horizontal media content processors or vertical media content processors. Because this distinction between people was based on the fictional concept of media content processors, participants had no prior information about this categorization which could lead them to assume that the groups differed in their likeability or status. In addition, laypersons are likely to perceive a connection between processing style and the experience of online videos, making it plausible that this categorization was related to the cover story of the study.

Commenting

Participants in the commenting conditions saw a textbox below the four comments in which they were asked to write their own comment. Participants in the no commenting conditions were not asked to write their own comment.

Measures

During the study, participants answered several questions. Unless stated otherwise, they did so by indicating how much they (dis)agreed with statements (further described below) on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Results of analyses provided in the measures section are based on the data of all participants (N = 290), unless stated otherwise.

Manipulation Checks

Three questions were asked to participants in the experimental conditions (n = 230) to verify if our manipulations were perceived as intended. First, we checked if participants perceived the comments as negative. Participants completed the following sentence: “In the user comments, the video was discussed…”. They did so by either selecting one point from a scale ranging from 1 (very negatively) to 7 (very positively), or by selecting I cannot remember. Second, we checked whether participants were aware if the people who wrote the comments were similar to, or different from them in terms of their content processing style. Participants chose one out of three options stating that (1) the comments were written by people who are similar to me in terms of their content processing style, (2) the comments were written by people wo are different from me in terms of their content processing style, or (3) I cannot remember. Third, we verified if participants knew whether or not they could write a comment while watching the video. Participants selected one of three options, namely (1) on the page with the video, I could watch the video and read user comments, (2) on the page with the video, I could watch the video, read user comments, and write my own comment, or (3) I cannot remember.

Video Enjoyment

Participants’ enjoyment of the video was measured using Wirth et al.’s (2012) scale to assess individuals’ hedonic entertainment experiences. Participants indicated their (dis)agreement with three statements, namely: “I felt well entertained watching the video”, “It was fun watching the video”, and “It was pleasurable watching the video”. By averaging participants’ scores on the three items, we created an overall video enjoyment score (see Table 1 for detailed information about the results of a factor analysis, scale reliability indices and descriptive scale statistics).

Table 1. Results of Factor Analyses, Scale Reliability Indices and Descriptive Scale Statistics.

|

|

Eigenvaluea |

Explained variancea |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

M (SD) |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

|

Video enjoyment |

2.62 |

87.34% |

.93 |

5.04 (1.34) |

-0.92 |

0.48 |

|

Social identification |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

2.50 (1.48) |

1.01 |

0.17 |

|

Perceived similarity |

2.95 |

73.77% |

.88 |

2.49 (1.03) |

0.48 |

-0.11 |

|

Social attraction |

3.14 |

78.36% |

.91 |

3.56 (1.08) |

-0.13 |

0.02 |

|

Perceived trustworthiness |

2.99 |

59.86% |

.83 |

4.22 (0.92) |

-0.80 |

1.70 |

|

Perceived social distance |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

5.36 (1.23) |

-0.67 |

0.23 |

|

Genre preference |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

5.17 (1.53) |

-0.82 |

-0.05 |

|

Note. aThe items of the video enjoyment, perceived similarity, social attraction, and perceived trustworthiness scales were subjected |

||||||

Social Identification

Participants’ social identification with the people who wrote the comments was measured using Postmes et al.’s (2013) single-item measure of social identification. Because participants in the control condition were not exposed to any comments, the measure of social identification was only administered in the four experimental conditions (n = 230). Participants were asked to indicate their (dis)agreement with the following item: “I identify with the people who wrote the comments about the video” (see Table 1).

Alternative Mediators

In addition to social identification, literature has used perceived similarity (Billig & Tajfel, 1973), social attraction (e.g., Hogg & Hains, 1996; Hogg & Turner, 1985), perceived trustworthiness (e.g., Lin & Xu, 2017; Reichelt et al., 2014) and perceived social distance (e.g., Lin & Xu, 2017; Yanovitzky et al., 2006) to explain social influences. Although scholars consider social identification to be a distinct concept and the key factor explaining the influence of information sources (Turner, 1982; Turner et al., 1987), these alternative factors may play a role in the effect of social information source on enjoyment. In the current case of the source of negative social information and video enjoyment, individuals may experience more similarity to the source, may feel more social attraction to the source, may have more trust in the source, and may perceive a smaller social distance to the source if that source belongs to the same social group. This, in turn, may decrease individuals’ video enjoyment. To control for these alternative mediators for the effect of the source of social information, we measured them among participants in the experimental conditions (n = 230).

Participants’ perceived similarity to the people who wrote the comments was measured with the four items of the perceived attitude similarity dimension of J. C. McCroskey et al. (1975) perceived homophily scale. Social attraction was measured using four items that are part of the social attraction dimension of the interpersonal attraction scale developed by L. L. McCroskey et al. (2006). Perceived trustworthiness was measured by a scale consisting of five indicators based on the perceived trustworthiness component of the source-credibility scale as developed by Ohanian (1990).

For each scale, we assessed whether the items loaded on one factor. Furthermore, we checked whether reliable scales could be formed based on these items. Results of factor analyses and reliability checks confirmed that this was indeed the case for all three scales (see Table 1). Finally, participants’ perceived social distance to the people who wrote the comments was measured with A. Aron et al.’s (1992) inclusion-of-other-in-the-self measure. For each participant, this led to a score between 1 and 7 where a higher score indicates a larger perceived social distance to the people who wrote the comments (see Table 1).

Genre Preference

One question asked participants to indicate how much they (dis)liked animated films and videos. Participants could do so by selecting one out of seven options ranging from 1 (dislike a great deal) to 7 (like a great deal). This question served as a randomization check (see Table 1).

Results

Randomization Check

Individuals’ entertainment experiences in response to media content are dependent on their media genre preferences and their biological sex (Hixson, 2006; Oliver et al., 2000). To minimize the risk that these two factors affect our results, we tested whether the randomization across conditions with regard to these two factors was successful. Participants’ preference for animated films and videos did not differ between conditions, F(4, 285) = 2.01, p = .094. However, participant’s biological sex differed between the conditions, χ2(4, N = 290) = 16.46, p = .002. Therefore, when testing the hypotheses, we conducted an additional series of analyses with biological sex as a covariate. However, including biological sex as a covariate did not alter the results of any hypothesis test, and, thus, we report the findings of the analyses without covariates below.

Manipulation Checks

To check if participants perceived the user comments presented alongside the video as negative, we inspected their scores on the item assessing how positive or negative they perceived the comments to be. Descriptive statistics showed that overall, participants perceived the comments as negative (M = 1.49, SD = 0.73). Furthermore, 98.7% of participants believed that the comments were somewhat negative, negative, or very negative. Based on this, we deemed the manipulation of the valence of the user comments successful.

Next, we checked whether participants in the experimental conditions perceived themselves to be similar to the people who wrote the comments in terms of their content processing style. Three participants indicated that they did not remember whether or not they were similar to the people who wrote the comments. To test whether our manipulation was successful among the participants who did believe that they knew whether or not they were similar to the people who wrote the comments, we ran a binary logistic regression using the data of these participants (n = 227). This analysis included social information source, writing one’s own comment, and the interaction term of these two variables as the predictor variables and participants’ answer to the questions about who wrote the comments as the dependent variable. The model explained 70% of the variance (Nagelkerke R2) and correctly classified 87.2% of the cases. Participants in the in-group conditions were more likely to indicate that they were similar to the people who wrote the comments (e4.16 = 63.78, p < .001), controlling for whether or not they could write their own comment.

A further look at the data showed that 85 participants (75.2%) in the in-group conditions (n = 113) realized that the people who wrote the comments were similar to them in terms of their content processing style. However, 27 participants (23.9%) indicated that they believed that the people who wrote the comments were different from them. The results further showed that 113 participants (96.6%) in the out-group conditions (n = 117) realized that they differed from the people who wrote the comments in terms of their content processing style. In addition, two participants (1.7%) believed that they were similar to the people who wrote the comments. Thus, while these results show that overall, our manipulation was successful, 32 out of 230 participants (13.9%) did not remember or did not remember correctly if the comments were posted by in-group or out-group members. As the effect of information source requires individuals to be aware of their common social group membership with that source (Turner, 1982; Turner et al., 1987) and following the procedure of previous studies (e.g., Mackie, 1986; Samu & Bhatnagar, 2008), the data of these 32 participants were excluded when testing the hypotheses.

To check whether the manipulation of writing one’s own comment worked, we ran a binary logistic regression on the data of participants in the experimental conditions (n = 230). The analysis included writing one’s own comment, social information source, and the interaction term of these two variables as the predictor variables. Participants’ answer to the questions about whether they could write their own comment while watching the video was included as the dependent variable. The model explained 85% of the variance (Nagelkerke R2) and correctly classified 95.2% of the cases. Participants who were in the commenting conditions were more likely to indicate that they could write their own comment (e5.88 = 357.50, p < .001), controlling for the source of the social information.

To learn more about the effect of our manipulation, we checked how many participants correctly remembered whether they could write a comment. We found that 113 participants (95.0%) in the commenting conditions (n = 119) realized that they could write their own comment while watching the video. However, further manual inspection of the data showed that of these 113 participants, one participant did not actually write a comment. In addition, six participants (5.0%) in the commenting conditions were not aware that they could write their own comment. Further inspection of the data provided by these six participants showed that although they believed it was not possible to write their own comment, five of them did in fact write a comment while watching the video. In the no commenting conditions (n = 111), 106 participants (95.5%) knew that they could not write their own comment while five participants (4.5%) believed that they could write their own comment while watching the video. However, it is certain that none of these five participants wrote their own comment, as it was not possible for them to do so. In sum, the results show that, overall, our manipulation was successful. However, one participant was neither aware that (s)he could write a comment despite the fact that (s)he was in the commenting condition, nor did (s)he actually write a comment. Therefore, the data of this one participant were excluded when testing the analyses.

Based on the results of the manipulation checks reported here, the data of a total of 33 participants were excluded from the analyses testing the hypotheses. Given the number of participants that were excluded from the analyses, we conclude the results section with a discussion of the analyses run on the full sample.

Tests of Hypotheses

The first hypothesis stated that exposure to negative social information decreases the enjoyment of video viewers. To test this, we ran an ANOVA using Welch’s test. The analysis included a dummy variable indicating whether participants were exposed to negative social information as the independent variable and participants’ video enjoyment as the dependent variable. Supporting Hypothesis 1, the results showed that participants who saw negative social information experienced less enjoyment (M = 4.87, SD = 1.32) than participants who did not see negative social information (M = 5.52, SD = 1.40), F(1, 93.53) = 10.07, p = .002, ηp2 = .04.

Hypothesis 2 stated that negative social information provided by one’s in-group would lead to less video enjoyment than negative social information provided by one’s out-group. Hypothesis 4 stated that writing one’s own comment in response to the video decreases video enjoyment. To test this, we analyzed the data of participants in the experimental conditions (n = 197). We ran a two-factorial ANOVA with social information source and commenting as the independent variables, and participants’ video enjoyment as the dependent variable. Results showed that participants who saw negative social information provided by in-group members experienced less video enjoyment (M = 4.65, SD = 1.47) than participants who saw the same information provided by out-group members (M = 5.04, SD = 1.18), F(3, 193) = 4.20, p = .042, ηp2 = .021, supporting Hypothesis 2. However, there was no difference in video enjoyment between participants who did and who did not write their own comment, p = .759, contradicting Hypothesis 4 (see Figure 2 for an overview of the enjoyment scores across conditions).

Figure 2. Video Enjoyment Across Conditions (Error Bars Depict the 95% Confidence Intervals).

Hypothesis 3 stated that the effect of a shared group membership with the source of social information on video enjoyment is mediated by viewers’ social identification with the source. To test this, we used PROCESS (Hayes, 2018) (version 3, model 4) with which we analyzed the data of participants in the four experimental conditions (n = 197). The source of social information was included as the independent variable, participants’ social identification with the source of the social information was the mediator, and participants’ video enjoyment was the dependent variable. In addition, writing one’s own comment was included as a covariate2. The results showed no effect of a shared group membership with the source of social information on participants’ social identification with that source, p =.070. In addition, the indirect effect of a shared group membership with the source of social information on viewers’ video enjoyment via social identification was not significant, Bootstrapped 95% CI [-.54, .04]. However, an increase in participants’ social identification with the source of negative social information led to less enjoyment, B = -.64, SE = .04, p < .001, 95% CI [-.72, -.55]. Overall, these results do not support Hypothesis 33.

Hypothesis 5 proposed that the effect of a shared group membership with the source of social information on social identification was moderated by writing one’s own comment in response to the video. To test this, we ran an ANOVA that included the source of the negative social information and writing one’s own comment in response to the video as independent variables and participants’ identification with the source of the social information as the dependent variable. The results showed no interaction effect of the source of social information and writing one’s own comment on participants’ social identification with the source of social information, p = .3144. Hypothesis 5 was not supported.

Analyses of Alternative Mediators

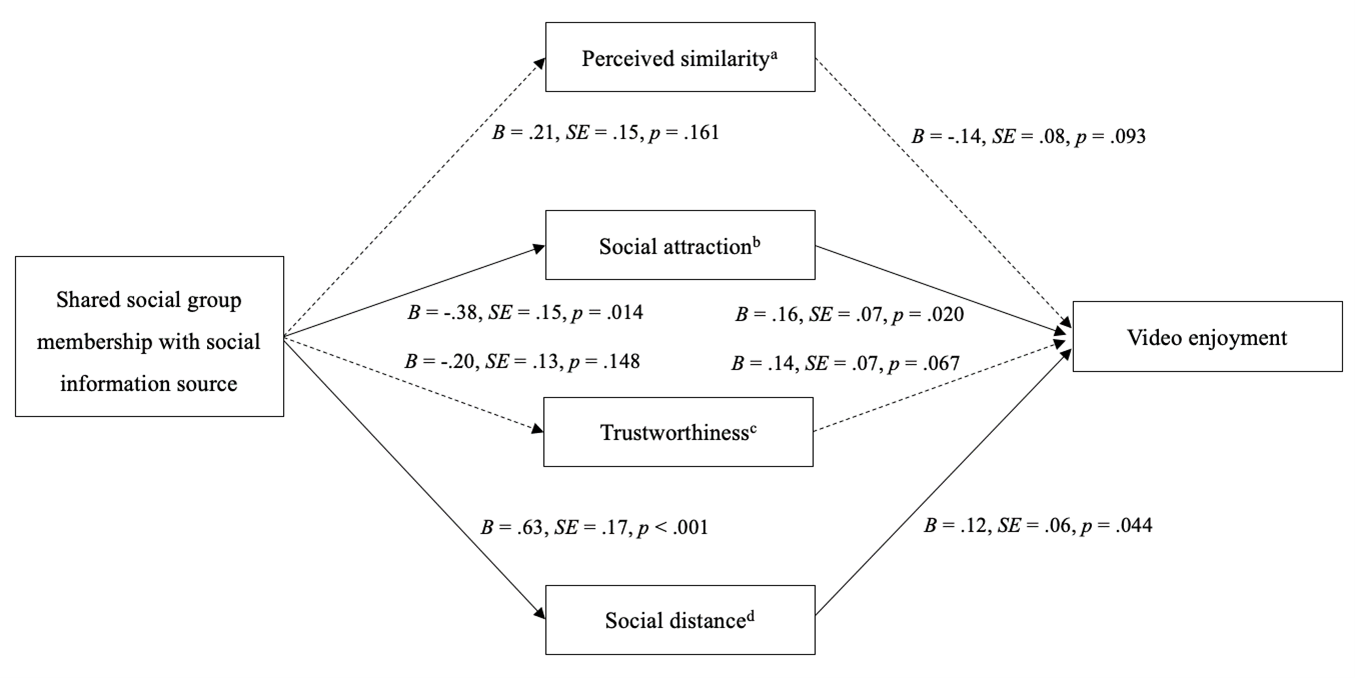

To investigate the role of the alternative mediators, we ran PROCESS (version 3, model 4) once again and included the alternative mediators. The resulting model included social information source as the independent variable, video enjoyment as the dependent variable, five mediators (i.e., social identification, perceived similarity, social attraction, trustworthiness, and social distance), and writing one’s own comment as a covariate. The results (see Figure 3) showed that participants’ perceived similarity to the source of the social information and their perceived trustworthiness of the source of social information were not affected by the source of social information, nor did they affect video enjoyment. Although social attraction correlated with the source of social information and with video enjoyment, these relations were not in a direction that one would expect based on the literature. Specifically, when the source of social information consisted of in-group members, participants experienced less social attraction to the source than when it consisted of out-group members. Moreover, as participants felt more social attraction toward the source of the negative social information, their video enjoyment increased. Both relations are in the opposite direction of what would be expected if social attraction played a similar role as social identification.

Figure 3. Role of Alternative Mediators.

Note. Bootstrapped Confidence Intervals of Indirect effects: a95% CI [-.10, .02], bIndirect effect 95% CI [-.15, -.002],

cIndirect effect 95% CI [-.09, .01], dIndirect effect 95% CI [.00, .18].

Finally, we found that participants perceived the social distance to the source of social information to be larger when that source consisted of in-group members than when it consisted of out-group members. In addition, an increase in perceived social distance to the source of negative social led to more video enjoyment. Although the latter is to be expected based on the literature discussed above, the fact that participants who saw social information provided by their in-group experienced a greater social distance to that group is not. Therefore, social distance does not seem to explain the effect of a shared group membership with the source of social information in a way that is similar to that of social identification.

Analyses on the Full Sample

Given that the data of 33 participants were excluded based on the results of the manipulation checks, we repeated the analyses testing the hypotheses using the full sample (N = 290). As to H1, results showed that participants who were exposed to negative social information experienced less enjoyment (M = 4.92, SD = 1.30) than participants who were not exposed to negative social information (M = 5.52, SD = 1.40), F(1, 87.37) = 9.07, p = .003, ηp2 = .03, supporting the hypothesis. These results corroborate the original findings.

We then ran the ANOVA testing Hypotheses 2 and 4 on the full sample of participants in the experimental conditions (n = 230). Results showed no difference between participants who saw negative social information provided by in-group members and participants who saw negative social information provided by out-group members in terms of video enjoyment, p = .161. There was also no difference in the video enjoyment of participants who could write their own comment in response to the video and those who could not, p = .777. Thus, when using the full sample, neither Hypothesis 2 nor Hypothesis 4 was supported. The results regarding Hypothesis 2 are in contrast to the original results based on the sample excluding participants who failed the manipulation checks.

Next, we ran PROCESS (version 3, model 4) using the data of all participants in the experimental conditions (n = 230) to test Hypothesis 3. Results showed that a shared group membership with the source of negative social information did not affect participants’ social identification with that source, p = .421. In addition, the indirect effect of the source of social information on video enjoyment via social identification was not significant, Bootstrapped 95% CI [-.35, .14]. However, an increase in participants’ social identification with the source of negative social information decreased their video enjoyment B = -.63, SE = .04, p < .001, 95% CI [-.71, -.55]. In line with the original findings, Hypothesis 3 was not supported.

Finally, we tested Hypothesis 5 using the data of all participants in the experimental conditions (n = 230). As in the original findings, we found no interaction effect of the source of social information and writing one’s own comment on social identification, p = .994.

Discussion

By studying the role of the source of social information and of writing one’s own comment in response to a video, the current study offers two contributions to the literature on the effects of social information on video enjoyment. First, it replicated the finding of extant research indicating that exposure to negative social information decreases viewers’ video enjoyment. Second, it advanced our knowledge about what makes this effect more likely to occur when individuals watch videos on social media. Our results showed that the influence of social information on video enjoyment was affected by a shared group membership with the source of social information. However, in contrast to our expectations, writing one’s own comment did not play a role in this process.

Negative social information created by in-group members led to less video enjoyment than negative social information created by out-group members. Similar to previous studies on the effects of social information on video enjoyment (i.e., Möller et al., 2019; Winter et al., 2018), our study found a modest effect of social information on video enjoyment. However, because social information is an inherent part of the content presented on social media and all viewers of a video are exposed to it, such a modest effect can alter the entertainment experiences of large groups of people. This is an important result in its own, but it is also relevant because viewers’ experiences while watching a video may affect their subsequent behavior: If viewers do not experience sufficient enjoyment while watching a video, they may stop watching it, or it may make them less willing to repeat the activity. Our results indicate that this is more likely to happen if videos are accompanied by negative social information that is created by viewers’ in-group members.

The effect of a shared group membership only occurred when tested exclusively among participants who were aware that they belonged to the same group as the source of the social information. Analyses on the full sample including viewers who were not aware if they belonged to the same group as the source of the social information did not show an effect of a shared group membership. These findings are in line with the notion of Social Categorization Theory that in order for individuals to comply with a group, a common social category membership with that group must be salient (Turner, 1982; Turner et al., 1987). However, it should be noted that excluding participants who did not know if they shared a group membership with the source of social information from our analyses negatively affects the random assignment procedure, leading to reduced internal validity (Christ, 2007). Although the exclusion of these participants is theoretically plausible, implications of excluding participants have to be considered when discussing the findings of this study.

The fact that not all of the participants realized that they (did not) belong to the same group as the source of the social information gives rise to the question of when social media users feel that they (do not) belong to the same social group as other viewers. In the current study, participants were explicitly told that they did (not) belong to the same social group as the people who wrote the comments based on the minimal-group paradigm. Apart from this information, they did not know anything else about the people who wrote the comments. However, on social media, there are likely to be multiple cues available about people who write comments, such as their age, gender, or their preferences. Thus, in real life settings, the effect of the source of social information is likely to be stronger than the effect reported here, as video viewers’ shared group membership with the people who write comments is based on more meaningful information.

Our results also showed that the source of social information did not affect participants’ social identification with that source. Thus, our results failed to support our hypothesis that the effect of a shared group membership with the source of social information on video enjoyment is mediated by social identification. A possible explanation is that participants did not believe that the user comments which they saw were created by other participants as they were told. However, our finding that the source of social information did affect viewers’ social attraction and social distance to that source contradicts this notion. The results regarding these alternative mediators did not, however, provide any theory-consistent mediation mechanisms that could explain the effect of the source of social information on video enjoyment. In fact, the alternative mediators were either not simultaneously related to predictor and outcome, or the direction of at least one relationship contradicted the theoretical expectations.

Our results further indicated that social identification with the source of negative social information negatively predicted viewers’ video enjoyment. However, because in the current study social identification was measured and not manipulated, our results do not preclude that the causal relationship between the two variables is reversed (Pirlott & MacKinnon, 2016; Spencer et al., 2005; Stone-Romero & Rosopa, 2008). Thus, it is possible that less video enjoyment leads viewers to experience more social identification with the source of the social information. For example, video viewers who experience less enjoyment may identify with the creators of social information more strongly because they agree with the negative opinion about the video as reflected in the comments.

Finally, according to our results, writing one’s own comment does not affect video enjoyment, nor does it moderate the effect of a shared social group membership with the source of the social information on social identification with the source. This contradicts our expectations based on the literature on interactivity showing that various forms of active user participation increase users’ focus on the content of websites. There are two possible explanations for this finding. On the one hand, interactivity is a broad concept (Sundar, 2004) and can be operationalized in different ways. The results of our study imply that the findings of extant research on specific operationalizations of interactivity (e.g., using a contact form) cannot be generalized to different operationalizations of the concept. On the other hand, our finding that writing one’s own comment has no effect may be due to the fact that participants in our study wrote a comment because they were instructed to do so, and not because they choose to do so. Outside of experimental lab settings, media users may choose to add their own comment to social information because the previously created comments caught their interest, making them more susceptible to the influence of these comments. In that case, writing a comment would still be a relevant variable to the influence of social information on video enjoyment. Additional research is necessary to fully understand this process.

Our study is subject to at least three limitations. First, the participant sample used in this study was a convenience sample with an average age of approximately 20 years old. Although this is an appropriate sample of social media users in the sense that these platforms are frequently used by young people, our sample existed exclusively of university students, which limits the external validity of our findings. Second, to collect the data for this study, participants were asked to come to the lab and watch an online video. While this approach helped to ensure that participants paid sufficient attention to the video and the questions, it also added a certain level of artificiality that reduced the ecological validity of our findings.

A third limitation is that we used a single video as the stimulus material for our study. On the one hand, we do not have a clear reason to assume that the effect of social information differs depending on the specific entertainment video that it accompanies, because previous studies consistently reported a valence effect while using various types of entertainment content (e.g., Möller et al., 2019; Möller & Kühne, 2019; Waddell & Bailey, 2019; Waddell & Sundar, 2017; Winter et al., 2018). On the other hand, the effects of social information may differ when it accompanies other media genres, such as videos containing political messages. There are two reasons why this may be the case. First, content characteristics are likely to differ between videos from different genres. Hence, the stimulus material used in this study is not representative of all video genres that are available online. Second, serious media content such as political videos are likely to be processed in a more systematic way than purely hedonic content, which may lead viewers to be more critical of the social information that accompanies them. Based on this, we suggest that scholars investigate how the effects of social information depend on the specific media genre that individuals are exposed to.

The current study contributes to the literature on the emergence of enjoyment in response to online content by investigating when the social information accompanying online videos is most likely to change viewers’ video enjoyment. In doing so, this study focused on two factors that are likely to vary when individuals use social media, namely the source of social information and whether or not viewers write their own comments in response to a video. Its results indicate that viewers’ shared group membership with the source of social information is an influential factor that needs to be considered. For future research, it seems that studying the effects of online social information from the theoretical lens of Social Categorization Theory is a promising approach that can advance our knowledge of how entertainment experiences emerge in online contexts.

Footnotes

- For all ANOVA’s that were run to test the hypotheses, we verified whether the assumptions of homoscedasticity and normality were met. For this model, results of Levene’s test indicated that the assumption of homoscedasticity was violated, F(3, 193) = 3.24, p = .023. Therefore, we also ran Welch’s test to test this hypothesis. Results indicated that social information provided by one’s in-group led to less enjoyment than social information provided by one’s out-group (p = .050).

- To verify if including this variable in the model substantially altered the results, we ran the model again without the variable indicating whether participants wrote their own comment. The results corroborated the original findings.

- We ran this model a second time using heteroscedasticity-consistent estimators. The results corroborated the original findings.

- Results of Levene’s test indicated that the assumption of homoscedasticity was violated, F(3, 193) = 4.23, p = .006. Therefore, we ran a model with heteroscedasticity-consistent estimators. The results corroborated the original findings.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected for the current study as well as the script used to analyze the data are available via the Open Science Framework (see: https://osf.io/hu84t/).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2020 Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace