Adolescent coping: In-person and cyber-victimization

Vol.13,No.4(2019)

Cyber-victimization has become a serious concern facing adolescents in the digital age. Given the differences and similarities between cyber-victimization and in-person victimization, research needs to examine whether prior understanding of coping with in-person victimization applies to coping with cyber-victimization. The purpose of this study was to compare the use and effectiveness of coping strategies in both in-person and cyber-victimization contexts in a sample of adolescents (N = 321; 11-15 years old) in the United States. Results indicated that adolescents tend to use more strategies overall to cope with in-person victimization than cyber-victimization, and female adolescents used more distraction and social support from friends than male adolescents. Adolescents also used problem solving, social support from friends and family/adults, and distraction more frequently than distancing and retaliation; when problem solving was used, adolescents felt positive about the outcome, regardless of victimization type. The use of retaliation was negatively associated with coping efficacy for both situations. Further, social support from friends and social support from family/adults were associated with coping efficacy for cyber-victimization. Our findings can be used to inform interventionists about which strategies adolescents perceive work best to cope with cyber-victimization.

Victimization; bullying; cyberbullying; coping; coping efficacy

Stacey B. Armstrong

Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Ferris State University, Big Rapids, Michigan, USA

Stacey B. Armstrong, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychology at Ferris State University. Her research interests include the strategies adolescents use to cope with cyber-victimization, the nuances of how adolescents learn strategies to cope with cyber-victimization, and the developmental effects of screen time in children, adolescents, and emerging adults.

Eric F. Dubow

Department of Psychology, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio, USA

Eric F. Dubow Ph.D., is Research Professor at the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research and Distinguished Professor of Psychology at Bowling Green State University. His research interests include: the development of risk and protective factors in children's adjustment; the development and implementation of school-based intervention programs to enhance coping skills in handling stressful and traumatic events; the development of aggression over time and across generations; and effects of exposure to ethnic-political violence and potential protective factors. He is the editor of the journal Developmental Psychology and the Bulletin Editor for the International Society for Research on Aggression.

Sarah E. Domoff

Department of Psychology, Central Michigan University, Mt. Pleasant, Michigan, USA Center for Human Growth and Development, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

Sarah E. Domoff, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor in Clinical Psychology in the Department of Psychology at Central Michigan University and Research Faculty Affiliate at the Center for Human Growth and Development at the University of Michigan. Dr. Domoff completed her doctoral training at Bowling Green State University in Clinical Psychology (Clinical Child concentration) and post-doctoral training at the University of Michigan. Dr. Domoff's research on low-income children's media use has been funded through a National Research Service Award through the NICHD. Dr. Domoff's research examines health outcomes associated with children's media use, such as obesity risk and sleep health. In her research, Dr. Domoff utilizes observational methodology, mixed-methods, and novel audio-recording and passive sensing technology to understand the potential impact of new media use on the health and development of children and adolescents.

Agatston, P. W., Kowalski, R., & Limber, S. (2007). Students’ perspectives on cyber bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(Suppl. 6), S59-S60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.003

Aricak, T., Siyahhan, S., Uzunhasanoglu, A., Saribeyoglu, S., Ciplak, S., Yilmaz, N., & Memmedov, C. (2008). Cyberbullying among Turkish adolescents. Cyberpsychology & Behavior 11, 253-261. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0016

Bird, G. W., & Harris, R. L. (1990). A comparison of role strain and coping strategies by gender and family structure among early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 10, 141-158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431690102003

Björkqvist, K., Lagerspetz, K. M. J., & Ӧsterman, K. (1992). The Direct & Indirect Aggression Scales (DIAS) [Measurement instrument]. Åbo Akademi University, Department of Social Sciences, Vasa, Finland.

Bushman, B. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2001). Is it time to pull the plug on hostile versus instrumental aggression dichotomy? Psychological Review, 108, 273-279. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.1.273

Camodeca, M., & Goossens, F. A. (2005). Aggression, social cognitions, anger, and sadness in bullies and victims. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 186-197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00347.x

Causey, D. L., & Dubow, E. F. (1992). Development of a self-report coping measure for elementary school children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 21, 47-59. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2101_8

Connor-Smith, J. K., Compas, B. E., Wadsworth, M. E., Thomsen, A. H., & Saltzman, H. (2000). Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 976-992. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.976

Craig, W., Pepler, D., & Blais, J. (2007). Responding to bullying: What works? School Psychology International, 28, 465-477. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034307084136

Dehue, F., Bolman, C., & Völlink, T. (2008). Cyberbullying: Youngsters' experiences and parental perception. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11, 217-223. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0008

Frisén, A., Berne, S., & Marin, L. (2014). Swedish pupils' suggested coping strategies if cyberbullied: Differences related to age and gender. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 55, 578-584. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12143

Griffith, M. A., Dubow, E. F., & Ippolito, M. F. (2000). Developmental and cross-situational differences in adolescents’ coping strategies. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 183-204. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005104632102

Hampel, P., & Petermann, F. (2006). Perceived stress, coping, and adjustment in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 409-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.014

Hankin, B. L., Mermelstein, R., & Roesch, L. (2007). Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Development, 78, 279-295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hunter, S. C., & Boyle, J. M. E. (2004). Appraisal and coping strategy use in victims of school bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 83-107. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709904322848833

Jacobs, N. C. L., Dehue, F., Völlink, T., & Lechner, L. (2014). Determinants of adolescents' ineffective and improved coping with cyberbullying: A Delphi study. Journal of Adolescence, 37(4), 373-385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.02.011

Juvonen, J., & Gross, E. F. (2008). Extending the school grounds?—Bullying experiences in cyberspace. Journal of School Health, 78, 496-505. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00335.x

Kowalski, R. M., & Limber, S. P. (2013). Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(Suppl. 1), S13-S20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.018

Li, Q. (2006). Cyberbullying in schools: A research of gender differences. School Psychology International, 27, 157-170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034306064547

Li, Q. (2007). New bottle but old wine: A research of cyberbullying in schools. Computers in Human Behavior, 23, 1777-1791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2005.10.005

Lodge, J., & Frydenberg, E. (2007). Cyber-bullying in Australian schools: Profiles of adolescent coping and insights for school practitioners. Educational & Developmental Psychologist, 24(1), 45-58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0816512200029096

Machackova, H., Cerna, A., Sevcikova, A., Dedkova, L., & Daneback, K. (2013). Effectiveness of coping strategies for victims of cyberbullying. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 7(3), article 5. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2013-3-5

Machmutow, K., Perren, S., Sticca, F., & Alsaker, F. D. (2012). Peer victimisation and depressive symptoms: Can specific coping strategies buffer the negative impact of cybervictimisation? Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 17, 403-420. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2012.704310

Mishna, F., Saini, M., & Solomon, S. (2009). Ongoing and online: Children and youth's perceptions of cyber bullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 1222-1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.05.004

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Ortega, R., Elipe, P., Mora‐Merchán, J. A., Genta, M. L., Brighi, A., Guarini, A., . . . Tippett, N. (2012). The emotional impact of bullying and cyberbullying on victims: A European cross‐national study. Aggressive Behavior, 38, 342-356. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21440

Pabian, S., & Vandebosch, H. (2016). An investigation of short-term longitudinal associations between social anxiety and victimization and perpetration of traditional bullying and cyberbullying. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 328-339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0259-3

Palladino, B. E., Nocentini, A., & Menesini, E. (2012). Online and offline peer led models against bullying and cyberbullying. Psicothema, 24, 634-639.

Parris, L., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., & Cutts, H. (2012). High school students’ perceptions of coping with cyberbullying. Youth & Society, 44, 284-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X11398881

Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2006). Bullies move beyond the schoolyard. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 4, 148-169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204006286288

Price, M., & Dalgleish, J. (2010). Cyberbullying: Experiences, impacts and coping strategies as described by Australian young people. Youth Studies Australia, 29(2), 51-59. Available at: https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=213627997089283;res=IELHSS

Raskauskas, J., & Stoltz, A. D. (2007). Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 43, 564-575. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.564

Riebel, J. R. S. J., Jaeger, R. S., & Fischer, U. C. (2009). Cyberbullying in Germany–an exploration of prevalence, overlapping with real life bullying and coping strategies. Psychology Science Quarterly, 51, 298-314. Available at: https://doaj.org/article/162a303760964515901c63304d958d2b

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 98-131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98

Roth, S., & Cohen, L. J. (1986). Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist. 41, 813-819. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.7.813

Selkie, E. M., Fales, J. L., & Moreno, M. A. (2016). Cyberbullying prevalence among US middle and high school–aged adolescents: A systematic review and quality assessment. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58, 125-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.026

Slonje, R., & Smith, P. K. (2008). Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49, 147-154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00611.x

Slonje, R., Smith, P. K., & Frisén, A. (2013). The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 26-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.024

Tokunaga, R. S. (2010). Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 277-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014

Völlink, T., Bolman, C. A. W., Eppingbroek, A., & Dehue, F. (2013). Emotion-focused coping worsens depressive feelings and health complaints in cyberbullied children. Journal of Criminology, 2013, article 416976. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/416976

Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2015). The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56, 483-488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.002

Weinstein, E. C., Selman, R. L., Thomas, S., Kim, J.-E., White, A. E., & Dinakar, K. (2016). How to cope with digital stress: The recommendations adolescents offer their peers online. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31, 415-441. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558415587326

Williams, K. R., & Guerra, N. G. (2007). Prevalence and predictors of Internet bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(Suppl. 6), S14-S21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.018

Wolak, J., Mitchell, K. J., & Finkelhor, D. (2007). Does online harassment constitute bullying? An exploration of online harassment by known peers and online-only contacts. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, S51-S58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.019

Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2007). Prevalence and frequency of internet harassment instigation: Implications for adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 189-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.03.005

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Skinner, E. A. (2015). Adolescent vulnerability and the distress of rejection: Associations of adjustment problems and gender with control, emotions, and coping. Journal of Adolescence, 45, 149-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.09.004

Editorial Record:

First submission received:

September 26, 2017

Revisions received:

May 5, 2018, April 10

2019, and August 8, 2019

Accepted for publication:

August 21, 2019

Editor in charge:

Lenka Dedkova

Introduction

In the past ten to fifteen years, parents, teachers, school administrators, and academic researchers have become more aware of peer stressors occurring online (frequently referred to as cyberbullying) with prevalence rates for experiencing online victimization reaching 72% (Selkie, Fales, & Moreno, 2016). High prevalence rates suggest that victimization occurring online can be a common experience for many adolescents, and it is cause for concern as it has been linked to a number of problematic internalizing and externalizing behaviors (see Ortega et al., 2012; Pabian & Vandebosch, 2016; Raskauskas & Stoltz, 2007; Waasdorp & Bradshaw, 2015) and negative consequences at school (see Kowalski & Limber, 2013; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2007). Due to these problematic outcomes, we sought to explore the ways in which adolescents cope with both in-person and cyber-victimization. In-person victimization is any behavior directed toward another individual that is intended to cause harm and that the target is motivated to avoid (Bushman & Anderson, 2001), while cyber-victimization is any electronic behavior directed toward an individual person that is intended to cause harm and that target is motivated to avoid (adapted from Bushman & Anderson, 2001). Because of the associated problematic outcomes of cyber-victimization, it is important to understand how adolescents cope with cyber-victimization, compare the strategies used for cyber-victimization with those used in response to in-person victimization, and identify effective coping strategies used to address both situations. Comparing in-person and cyber-victimization coping is helpful for applied purposes. For instance, many cyber-victimization programs, which are administered to adolescents in the academic setting, are based on in-person coping programs. However, there is little theoretical support suggesting that effective coping strategies for in-person victimization also apply to cyber-victimization events.

Coping With Cyber-Victimization

In the cyber-victimization literature, a number of studies have identified strategies used to address victimization occurring online. However, little attention has been given to studying coping using established models. For instance, some coping strategies (e.g., behavioral, emotional, cognitive) are directed toward the stressor while others are directed away from the stressor (Roth & Cohen, 1986).

In strategies directed toward the stressor, social support has been the focus of many early studies evaluating how adolescents cope with cyber-victimization. For instance, some research suggested that a relatively small number of students seek adult social support when they or someone they know experiences cyber-victimization. A number of studies found that between 34-90% of adolescents denied telling anyone about cyber-victimization (Agatston, Kowalski, & Limber, 2007; Juvonen & Gross, 2008; Li, 2007). Researchers have posited that adolescents do not report cyber-victimization events because the youth are concerned that they will lose their online privileges, thus perceiving it to be ineffective. However, there are mixed results on this front. One study found that 71% of their research sample reported they would seek out help from an adult (Frisén, Berne, & Marin, 2014). Problem solving, also directed at the stressor, appears to be heavily relied upon by many adolescents. Youths stated they would institute stricter privacy settings on their social networking and instant messaging accounts, change their username, change their account password, block unwanted messages or people, and/or confront the perpetrator in effort to effectively solve the problem (Aricak et al., 2008; Juvonen & Gross, 2008; Patchin & Hinduja, 2006; Tokunaga, 2010; Weinstein et al., 2016). Another coping strategy, retaliation, also referred to as “bullying back,” is used by adolescents in response to cyber-victimization (Camodeca & Goossens, 2005; Price & Dalgleish, 2010; Riebel, Jaeger, & Fischer, 2009) to “get even” with their perpetrator or to “get back” at him/her.

In terms of strategies directed away from the stressor, distancing (e.g., acting like the cyber-victimization never happened, just ignoring the problem altogether) has also been identified as a common strategy used by adolescents (Juvonen & Gross, 2008; Parris, Varjas, Meyers, & Cutts, 2012; Weinstein et al., 2016). Lastly, engaging in an activity with the intention of taking one’s mind off the problem (i.e., distraction) has been under-investigated as a cyber-victimization coping strategy. One study evaluated adolescent use of physical activity as a form of distraction to cope with cyber-victimization (Lodge & Frydenberg, 2007).

Gender Differences in Cyber-Victimization Coping

Gender differences have been identified in adolescents’ coping. For in-person interpersonal stressors, female adolescents appear to utilize more social support and problem solving, while male adolescents tend to use more externalizing/retaliation (Causey & Dubow, 1992; Hampel & Peterman, 2006; Hunter & Boyle, 2004). These results are consistent with cultural socialization trends that suggest female adolescents are socialized to use more social support (Bird & Harris, 1990) and experience interpersonal stressors more frequently and are more distressed by them (Hankin, Mermelstein, & Roesch, 2007; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Gender differences in the use of distraction appear to present more mixed results across studies (see Hampel & Peterman, 2006; Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, 2015). When it comes to coping with cyber-victimization specifically, there has been less investigation; however, some trends have emerged generally matching in-person interpersonal stressor coping and cultural socialization trends. For example, female adolescents have been shown to use more social support (from adults and friends), while male adolescents report using more retaliation (Frisén et al., 2014; Machmutow, Perren, Sticca, & Alasker, 2012). Compelling evidence of gender differences in the use of other coping strategies such as distancing, distraction, and problem solving is not readily available; therefore, continued research is needed.

Cyber-Victimization Coping Efficacy

In addition to the little attention that has been given to studying cyber-victimization coping using established coping models, adolescents’ perceptions of whether coping strategies worked (i.e., “perceived efficacy”) has been relatively understudied. Researchers have begun to explore the efficacy of coping strategies (i.e., does the coping strategy work or help the adolescent) for cyber-victimization. One way to assess coping efficacy is to determine whether the coping strategy makes the cyber-victimization stop. Strategies identified as successfully stopping the victimization were primarily problem-solving strategies, but also included seeking support and ignoring the perpetrator intentionally (Machackova, Cerna, Sevcikova, Dedkova, & Daneback, 2013). Another way researchers have evaluated coping efficacy includes analyzing how well the strategy buffers the negative impacts of cyber-victimization (e.g., depressive symptoms, health complaints; Machmutow et al., 2012; Völlink, Bolman, Eppingbroek, & Dehue, 2013). The results of these studies showed that problem solving and seeking social support from peers and family decreased self-reported depression and physical complaints, while the use of retaliation and ignoring the problem was related to higher levels of depression and physical symptoms in the face of cyber-victimization.

Further, other researchers have evaluated coping efficacy using other methods, such as the Delphi technique, which “is an iterative process used to reach consensus among experts” (Jacobs, Dehue, Völlink, & Lechner, 2014, p. 375). This evaluation method revealed that strategies such as wishful thinking and emotional expression (e.g., retaliation, avoidance) were related to ineffective coping, while strategies like problem solving and social support were related to what the researchers termed “improved coping” (see Jacobs et al., 2014).

These conceptualizations of coping efficacy tend to be objective views of how the situation turned out. While understanding objectively whether the coping strategy stopped the online victimization or decreased negative impacts, the adolescents’ perception of efficacy is also important. Examples of perceived coping efficacy include the adolescents’ views of whether the situation turned out well or whether the adolescent felt he or she learned something from coping with the situation. These perceptions of coping strategy efficacy can occur independently of whether the victimization stopped or negative impacts of the victimization were buffered. When studying adolescents’ perceptions of efficacy, strategies like reaching out to someone (i.e., social support), problem solving, ignoring the problem, and retaliating were all reported as having some degree of helpfulness (Price & Dalgleish, 2010). We were unable to find additional literature evaluating perceived cyber-victimization coping efficacy, suggesting that further research is needed to more comprehensively understand perceptions of coping efficacy when coping with cyber-events.

The Present Study

Given the rates of cyber-victimization and its harmful effects, researchers and interventionists must understand if and how coping with cyber-victimization differs from coping with in-person victimization. Additionally, examining adolescents’ perceptions of coping efficacy when responding to in-person and cyber-victimization is needed. Understanding whether coping strategy utilization and perceived efficacy differ between in-person victimization and cyber-victimization has practical implications, such as facilitating the critical examination of anti-bullying curricula to ensure the most appropriate coping strategies are being taught and reinforced to adolescents for each type of victimization.

The purposes of this study are to (1) determine which coping strategies participants think they would use for each type of victimization, (2) explore gender differences in the use of coping strategies, and (3) test which strategies predict adolescents’ feelings of efficacy in coping with cyber- and in-person victimization. To explore these aims, we identified the following hypotheses:

- Based on the current cyber-victimization body of literature, we predicted that in response to being cyber-victimized, adolescents would use higher levels of problem solving and social support from friends compared to in-person victimization. A number of studies have shown that adolescents commonly report using problem solving strategies (e.g., instituting stricter privacy settings on accounts; Juvonen & Gross, 2008; Tokunaga, 2010; Weinstein et al., 2016) and are more willing to seek out support from friends rather than adults in situations of cyber-victimization (Slonje, Smith, & Frisén, 2013). With respect to in-person victimization, we hypothesized that adolescents would report utilizing more social support from family and adults than for cyber-victimization because of the literature’s compelling evidence that adolescents utilize little to no social support from family/adults in cyber-victimization situations (Agatston et al., 2007; Slonje & Smith, 2008).

- We predicted that female adolescents would report using more social support (from both family/adults and from friends) and problem solving than male adolescents, and male adolescents would use more retaliation than female adolescents. Our predictions were based on studies evaluating gender differences in coping with cyber-victimization (Frisén et al., 2014; Machmutow et al., 2012).

- We predicted that adolescents would report feeling that their coping was effective when they used higher levels of problem solving and social support from family/adults and friends. Existing research exploring the effective use of coping strategies provided the grounds for our prediction on coping efficacy in the current study (Jacobs et al., 2014, Machackova et al., 2013; Völlink et al., 2013).

Method

Participants and Procedures

In the fall of 2012, we surveyed 321 7th (n = 161) and 8th graders (n = 156) from one middle school (which included 6th through 8th graders) in a suburban school district outside of a moderately-sized Midwestern city (51% male, 67% White). Adolescents ranged in age from 11 to 15 years old (M = 12.87, SD = 0.72). Research suggests that cyber-victimization peaks around 8th grade (Williams & Guerra, 2007). We chose to study the 7th and 8th graders because older students tend to have more access to smartphones and the internet. In total, including all grades (6th-8th), there are over 500 enrolled students each year, and at the time of the survey, there were 361 students enrolled in the 7th and 8th grades. At this school, 19% of students at the junior high school are eligible for low-cost or free lunches, which is lower than the average for the county in which the school exists (53%), according to propublica.org. Approximately 80% of the student population at this school is White, 7% of the students are Asian or Pacific Islander, and 5% are African American. There are also roughly equal percentages of male and female students (52% male, 48% female). This sample’s sociodemographic characteristics are comparable to those of the school as a whole, and therefore we believe that our results can be generalized to suburban schools with similar demographic compositions.

Parents were mailed a study description with an opt-out of participation attachment (granted by investigator’s Institutional Review Board) that was to be returned if they did not want their child to participate. This process ensured a larger and more representative sample than if active parental consent were required from each parent. Of the total students enrolled in these two grades, 93% completed the survey (n = 334); non-completion was the result of opt-outs and absences. However, 13 participants’ surveys were not included in the analyses due to noticeable patterns in response styles, leaving a total of 321 student participants. Participation was strictly voluntary, and the students had the option to withdraw from the study at any time, though no students declined to participate.

The measures were administered in several class sessions at the school during 45-minute periods. Each student was given a brief description of the rationale behind the study and asked for his or her assent to participate. The first author and three graduate and undergraduate assistants were available to answer students’ questions regarding the completion of the measures during the sessions. To ensure participant privacy, all measures were completed anonymously (no identifying information was collected) and no incentives were provided for participation.

In the present study we used hypothetical coping so we could include the most participants in our analyses. Prior to carrying out this study, it was unknown how many youths in our sample experienced both in-person and cyber-victimization. Further, we use hypothetical coping to decrease the risk of underreporting less socially acceptable strategies such as retaliation. We believed that some adolescents would not accurately report retrospective coping because of worries about possible negative consequences if they endorse prior use of maladaptive coping skills.

The sample of students who participated in the study ranged in their use of electronic media. For instance, 71% of the sample indicated that they used instant messaging one time or more during the week, 75% reported that they frequent social networking websites one time or more per week, and 67% reported that they use text messaging most days to every day of the week.

Measures

Experiences with in-person and cyber-victimization. The introduction to the coping survey about in-person and cyber-victimization presented a short list of stressors to prompt the participant to think about various in-person and online experiences they had during the previous year. The directions used for in-person victimization were:

Even when things are going well for teenagers, almost everyone still has some problems with other kids. When we say ‘problems with other kids,’ we mean when another kid says mean things or does mean things to you in-person. Please put a check mark in the ‘Yes’ box if any of the problems with other kids listed below happened to you during the last year. If these things did not happen to you in the past year, put a check mark in the ‘No’ box.

For cyber-victimization, the directions were:

Another type of problem is cyber-problems. When we say ‘cyber-problems,’ we mean when another kid says mean things or does mean things to you on the internet, through texting, or on cell phones. Please put a check mark in the ‘Yes’ box if any of the cyber-problems with other kids listed below happened to you during the last year. If these things did not happen to you in the past year, put a check mark in the ‘No’ box.

A short list of stressors for in-person and cyber-victimization was also provided. The short list of stressors included seven in-person victimization experiences adapted from the Direct and Indirect Aggression Scales (Björkqvist, Lagerspetz, & Ӧsterman, 1992) and eight cyber-victimization experiences adapted from the Internet Experiences Questionnaire (Raskauskas & Stoltz, 2007). For example, in-person victimization items included, “Another kid hit, pushed, shoved, or kicked me;” and “Another kid spread rumors about me whether they were true or not.” Examples for cyber-victimization included, “Another kid said mean things or did mean things to me on the internet, through text messaging, or on a cell phone;” and “Another kid made a threatening or aggressive comment to me online or on a cell phone.” Experiences with victimization were used in our analyses as a binary variable (i.e., 0 = no experience in the last 12 months; 1 = at least one experience in the last 12 months). Each participant was assigned a sum score of problems he or she experienced for both in-person and cyber-victimization.

Coping. For both in-person and cyber-victimization, the participants responded to how often they would use 28 coping strategies. The coping items were adapted from subscales from Causey and Dubow’s (1992) Self-Report Coping Scale for youth and from Connor-Smith et al.’s (2000) Responses to Stress Questionnaire (RSQ). The subscales were: problem solving (five items; e.g., I try to think of different ways to change the problem or fix the situation), seeking social support from a friend (three items; e.g., Ask a friend for advice) and seeking social support from a family member or other adults (four items, e.g., Ask a family member for advice), distancing (six items; e.g., Make believe nothing happened), retaliation (four items; e.g., Do to that person what he or she did to me), and distraction (four items; e.g., I imagine something really fun or exciting happening in my life). See Table 1 for subscale means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alphas.

In-person victimization coping. The specific instructions for the in-person victimization coping items were as follows: “For each item on the list below, circle how much you would do or think each thing if other kids say mean things or do mean things to you in person.” We worded the measures this way because we wanted all adolescents to complete this measure regardless of their experiences with victimization. Participants rated how often they would use specific coping strategies on a 4-point scale (1 = Not at all; 2 = A little; 3 = Sometimes; 4 = A lot; see Appendix A).

Cyber-victimization coping. The specific instructions for the cyber-victimization coping items were as follows: “For each item on the list below, circle how much you would do or think each thing if other kids say mean things or do mean things to you on the internet, through text-messages, or on cell phones.” Participants rated how often they would use specific coping strategies on a 4-point scale (1 = Not at all; 2 = A little; 3 = Sometimes; 4 = A lot; see Appendix A).

Table 1. Subscale and Efficacy Means, Standard Deviations, and Cronbach’s Alphas.

|

|

In-Person |

Cyber |

||||

|

M |

SD |

α |

M |

SD |

α |

|

|

Problem Solving |

2.34 |

0.68 |

.72 |

2.27 |

0.75 |

.83 |

|

Social Support – Family/Adult |

2.20 |

0.87 |

.83 |

2.15 |

0.95 |

.87 |

|

Social Support - Friend |

2.28 |

0.86 |

.73 |

2.36 |

0.94 |

.80 |

|

Distancing |

2.10 |

0.71 |

.74 |

2.0 |

0.78 |

.84 |

|

Retaliation |

1.63 |

0.71 |

.76 |

1.57 |

0.76 |

.82 |

|

Distraction |

2.52 |

0.80 |

.70 |

2.47 |

0.86 |

.81 |

|

Efficacy |

3.50 |

0.83 |

.83 |

3.45 |

0.94 |

.77 |

Table 2. Results of a Principal Axis Factor Analysis With a Promax Rotation for the Coping Items for In-Person Victimization Experiences.

|

Item # |

Item Description |

Factor 1 (Social Support-Family/ |

Factor 2 (Distancing) |

Factor 3 (Retaliation) |

Factor 4 (Problem Solving) |

Factor 5 (Distraction) |

Factor 6 (Social Support-Friend) |

|

14 |

Ask a family member for advice |

.78* |

-.07 |

-.07 |

.15 |

-.14 |

.82 |

|

27 |

Get help from a family member |

.78* |

-.04 |

-.14 |

.11 |

-.12 |

.09 |

|

28 |

Talk to the teacher, counselor, or another adult at school |

.75* |

-.06 |

.02 |

-.02 |

.07 |

-.04 |

|

5a |

Talk to somebody about how it made me feel |

.60* |

.10 |

.03 |

.09 |

-.13 |

.35 |

|

1 |

Tell a friend of family member what happened |

.59* |

-.07 |

-.05 |

-.11 |

-.04 |

.36 |

|

24 |

Say I don’t care |

-.16 |

.71* |

.04 |

.09 |

-.20 |

.22 |

|

10 |

Forget the whole thing |

.01 |

.67* |

-.05 |

-.15 |

.16 |

-.16 |

|

13 |

Tell myself it doesn’t matter |

-.24 |

.64* |

-.09 |

.08 |

.11 |

-.03 |

|

25 |

Ignore it when other people say something about it |

-.02 |

.63* |

-.04 |

.04 |

-.05 |

.05 |

|

16 |

Refuse to think about it |

.33 |

.59* |

.13 |

-.12 |

.16 |

-.25 |

|

3 |

Make believe nothing happened |

-.05 |

.59* |

-.002 |

-.14 |

.21 |

-.12 |

|

22 |

Curse at that person |

.17 |

-.11 |

.79* |

.09 |

.11 |

.06 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

Do to that person what he/she did to you because I felt sad or angry |

-.04 |

.003 |

.76* |

-.05 |

-.08 |

.10 |

|

17 |

Yell at that person to let off steam |

.03 |

.19 |

.73* |

-.01 |

-.17 |

.06 |

|

26 |

Get mad at the person and throw something at him/her or hit him/her |

.01 |

-.18 |

.78* |

-.04 |

.12 |

-.27 |

|

2 |

Try to think of different ways to solve it |

-.07 |

-.12 |

-.07 |

.76* |

.22 |

-.20 |

|

15 |

Know there were things I could do to make it better |

.23 |

.11 |

-.02 |

.68* |

-.07 |

-.11 |

|

9 |

Decide on one way to deal with the problem and do it |

.08 |

-.19 |

.10 |

.63* |

.16 |

-.05 |

|

6 |

Change something so things would work out |

.07 |

.05 |

-.06 |

.62* |

.19 |

-.13 |

|

19 |

Go over in my mind what to do or say |

-.14 |

.03 |

.08 |

.58* |

-.09 |

.29 |

|

11 |

Keep my mind off the problem by: Exercise, video games, see friends, do a hobby, and/or watch TV |

-.15 |

-.05 |

-.01 |

-.03 |

.73* |

.36 |

|

20 |

Do something else to take my mind off it |

-.10 |

.13 |

-.09 |

.21 |

.63* |

.14 |

|

7 |

Think about happy things to take my mind off the problem or how I was feeling |

-.05 |

.10 |

.05 |

.15 |

.62* |

.23 |

|

21 |

Imagine something really fun or exciting happening in my life |

.19 |

.16 |

.01 |

.13 |

.56* |

.06 |

|

12 |

Ask a friend for advice |

.06 |

-.07 |

-.10 |

-.13 |

.32 |

.84* |

|

8 |

Get help from a friend |

.11 |

-.07 |

.02 |

-.15 |

.24 |

.80* |

|

18 |

Ask another kid who had this problem what he or she did |

.28 |

-.01 |

.12 |

-.06 |

.22 |

.47* |

|

23a |

Try to understand why it happened to me |

.33 |

.17 |

.22 |

.21 |

-.04 |

.31 |

|

|

Eigenvalue |

5.14 |

3.14 |

2.59 |

1.40 |

1.40 |

1.20 |

|

|

% variance account for by factor |

19.02% |

12.63% |

9.60% |

5.20% |

5.15% |

4.45% |

|

Note. Principal axis factor analysis was used with a Promax rotation, and results are reported as standardized regression coefficients. |

|||||||

Table 3. Results of a Principal Axis Factor Analysis With a Promax Rotation for the Coping Items for Cyber-Victimization Experiences.

|

Item # |

Item Description |

Factor 1 (Distancing) |

Factor 2 (Problem Solving) |

Factor 3 (Social Support-Family/Adult) |

Factor 4 (Distraction) |

Factor 5 (Retaliation) |

Factor 6 (Social Support-Friend) |

|

13 |

Tell myself it doesn’t matter |

.82* |

.01 |

.02 |

-.10 |

-.03 |

-.01 |

|

10 |

Forget the whole thing |

.80* |

-.03 |

.01 |

.06 |

.07 |

-.10 |

|

24 |

Say I don’t care |

.78* |

.03 |

-.07 |

-.19 |

-.004 |

.14 |

|

16 |

Refuse to think about it |

.73* |

-.05 |

.02 |

.16 |

.05 |

-.03 |

|

25 |

Ignore it when other people say something about it |

.71* |

-.03 |

.07 |

.03 |

.03 |

.03 |

|

3 |

Make believe nothing happened |

.58* |

.06 |

-.07 |

.22 |

-.10 |

-.03 |

|

19 |

Go over in my mind what to do or say |

-.03 |

.82* |

-.20 |

-.09 |

.05 |

.25 |

|

15 |

Know there were things I could do to make it better |

.05 |

.81* |

.14 |

.01 |

.01 |

-.22 |

|

6 |

Change something so things would work out |

-.10 |

.72* |

.02 |

.20 |

-.04 |

-.19 |

|

2 |

Try to think of different ways to solve it |

-.05 |

.69* |

.18 |

.07 |

-.02 |

-.05 |

|

9 |

Decide on one way to deal with the problem and do it |

.14 |

.63* |

.26 |

-.14 |

.02 |

-.11 |

|

23a |

Try to understand why it happened to me |

-.04 |

.59* |

-.20 |

.01 |

.01 |

.31 |

|

14 |

Ask a family member for advice |

-.02 |

.10 |

.85* |

-.07 |

-.03 |

.07 |

|

27 |

Get help from a family member |

-.01 |

.11 |

.86* |

-.05 |

-.04 |

.03 |

|

28 |

Talk to the teacher, counselor, or another adult at school |

-.003 |

-.10 |

.76* |

.07 |

.07 |

.07 |

|

1 |

Tell a friend of family member what happened |

.05 |

.06 |

.66* |

-.02 |

-.07 |

.26 |

|

21 |

Imagine something really fun or exciting happening in my life |

-.004 |

.04 |

.04 |

.84* |

.00 |

-.08 |

|

11 |

Keep my mind off the problem by: Exercise, video games, see friends, do a hobby, and/or watch TV |

-.01 |

-.12 |

.01 |

.79* |

.01 |

.05 |

|

20 |

Do something else to take my mind off it |

.10 |

.05 |

-.04 |

.74* |

-.06 |

.09 |

|

7 |

Think about happy things to take my mind off the problem or how I was feeling |

.02 |

.13 |

-.10 |

.71* |

-.01 |

.10 |

|

5a |

Talk to somebody about how it made me feel |

-.01 |

.09 |

.28 |

.62* |

-.04 |

-.02 |

|

17 |

Yell at that person to let off steam |

.08 |

.03 |

-.02 |

-.07 |

.87* |

.01 |

|

26 |

Get mad at the person and throw something at him/her or hit him/her |

-.09 |

-.19 |

.21 |

.11 |

.80* |

-.01 |

|

22 |

Curse at that person |

.03 |

.11 |

-.14 |

-.06 |

.79* |

.11 |

|

4 |

Do to that person what he/she did to you because I felt sad or angry |

.01 |

.06 |

-.06 |

-.001 |

.76* |

.04 |

|

12 |

Ask a friend for advice |

-.01 |

-.11 |

.12 |

.06 |

-.06 |

.88* |

|

8 |

Get help from a friend |

.04 |

-.08 |

.17 |

.01 |

.003 |

.87* |

|

18 |

Ask another kid who had this problem what he or she did |

-.09 |

.13 |

.16 |

.25 |

.20 |

.39* |

|

|

Eigenvalues |

6.90 |

3.82 |

2.55 |

1.50 |

1.44 |

1.25 |

|

|

% variance account for by factor |

25.54% |

14.15% |

9.43% |

5.56% |

5.34% |

4.62% |

|

Note. Principal axis factor analysis was used with a Promax rotation, and results are reported as standardized regression coefficients. |

|||||||

Analysis of fit. Because we combined subscales from two separate coping measures (Self-Report Coping Measure for Youth and the Responses to Stress Questionnaire), we first computed two principal axis factor analyses with Promax rotations, one for each victimization type. The results of the factor analyses indicated that 26 of the 28 items loaded onto the respective factors, based on their highest loading, for in-person and cyber-victimization (Tables 2 and 3). The items “talk to somebody about how it made me feel” and “try to understand why it happened to me” generally had a low standardized regression coefficient on both the in-person and cyber-victimization factor analyses and/or failed to load consistently across measures. These items were dropped from subsequent analyses and were not considered in the calculation of the subscales. The final six-factor solution utilized three items on the social support-friend factor, four items on the social support-adult/family factor, five items on the problem solving factor, six items on the distancing factor, four items on the retaliation factor, and four items on the distraction factor. Items loading on each factor were averaged to yield subscale scores (α’s: .64- .85).

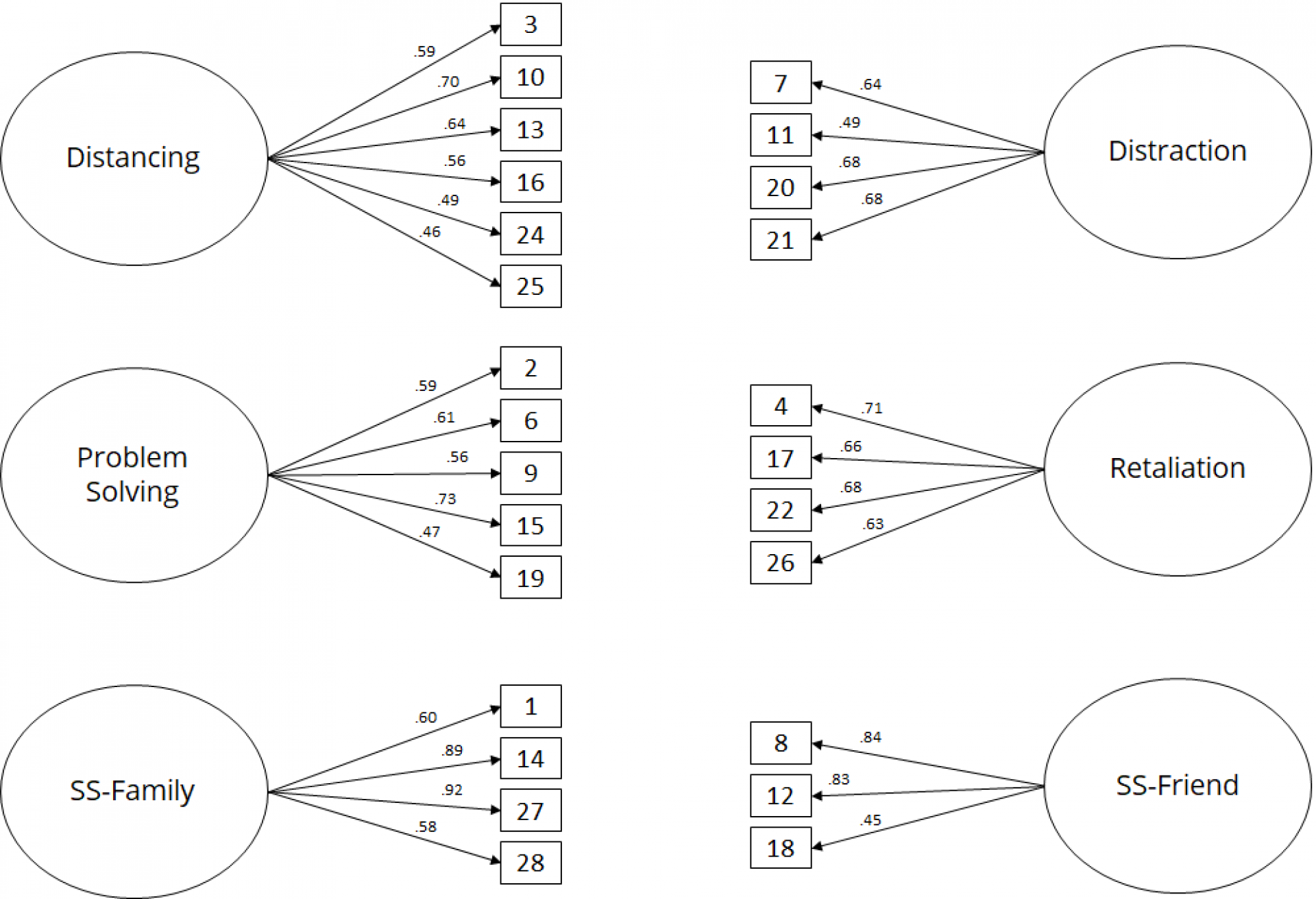

Figure 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the In-Person Victimization Coping Scale. Please reference Table 2 for items. Standardized estimates are listed above the arrows, all p < .01

Figure 2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Cyber-Victimization Coping Scale. Please reference Table 3 for items. Standardized estimates are listed above the arrows, all p < .01

We followed up our analyses with two confirmatory factor analyses, one for in-person victimization coping and one for cyber-victimization coping to confirm the structure of our measures using Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Adequate fit was determined by the following criteria (Hu & Bentler, 1999): Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < .06, Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR) < .09, and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > .95. The six-factor model demonstrated appropriate fit for both the cyber-victimization coping measure (χ2 (284) = 472.41, p < .01; RMSEA = .046, CFI = .939, SRMR = .058) and in-person victimization coping measure (χ2 (284) = 471.57, p < .01; RMSEA = .045, CFI = .911, SRMR = .061). All item loadings on specified factors were significant and above .40 (see Figures 1 and 2).

Perceived in-person and cyber-victimization coping efficacy. After rating how the participants would have handled an experience of in-person and cyber-victimization, we assessed whether they felt efficacious in their coping for both situations separately. To evaluate coping efficacy, we asked adolescents to rate how well the situation would turn out given their coping efforts. Specifically, for in-person victimization we used the prompt: “Think about the same situation when other kids say mean things or do mean things to you in person. Thinking about the things you would do to deal with the problem, please rate how much you agree or disagree with the following statements about how things would turn out.” For cyber-victimization we used the prompt: “Think about the same situation when other kids say mean things or do mean things to you on the internet, through text-messages, or on cell phones. Thinking about the things you would do to deal with the problem, please rate how much you agree or disagree with the following statements about how things would turn out.” We worded the measure prompts this way because we wanted all adolescents to complete the measure regardless of their experiences with both types of victimization.

Participants were asked to rate six statements according to how well the problem would turn out given their coping efforts (e.g., “I would handle the event well given the circumstances,” “I would do a good job solving the problem;” Griffith, Dubow, & Ippolito, 2000; Causey & Dubow, 1992). Participants responded on a 5-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Sort of disagree; 3 = Agree and disagree; 4 = Sort of agree; 5 = Strongly agree; see Appendix B) and scores were derived by averaging the responses to the items with higher scores reflecting higher levels of perceived efficacy (in-person α = .77; cyber α = .83). See Table 1 for efficacy means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alphas.

Analysis

We used IBM SPSS Statistics (version 24) to conduct our analyses. To evaluate whether the same students reported different levels of coping to handle with in-person and cyber-victimization, we computed a repeated measures MANCOVA (R-MANCOVA) with two within-subjects factors: 1) situation (in-person vs. cyber-victimization) and 2) coping (problem solving, social support from friends, social support from family/adults, distraction, distancing, retaliation). We included gender, grade level, race (white/non-white), and recent experience with in-person and cyber-victimization. We followed up this analysis with a series of paired t-tests (Bonferroni corrected) to determine if specific coping strategies differed between in-person victimization and cyber-victimization.

We also examined whether specific coping strategies uniquely predicted ratings of coping efficacy by computing two hierarchical linear regressions, one for efficacy in coping with in-person victimization and one for efficacy in coping with cyber-victimization. In each regression, the first step included the background variables of participant gender, grade, race, and recent experience with in-person and cyber-victimization. The second step included the six coping strategies.

Results

Coping Strategies Used for In-Person and Cyber-Victimization

In our sample of adolescents, 53% reported having experienced a cyber-victimization event, and 79% experienced an in-person victimization event in the last 12 months. The repeated measures ANOVA resulted in significant main effects for situation (F(1, 282) = 5.57, p < .05) and coping strategies (F(5, 278) = 30.29, p < .05). In addition, there was a significant interaction between situation and coping strategies (F(5, 278) = 3.14, p < .05; see Figure 3) which was followed up with a series of paired t-tests. Results indicated that adolescents reported that they would use more strategies in general to cope with in-person victimization. Further, they reported they would use more problem solving, retaliation, distraction, distancing, and social support from family/adults for in-person victimization, and they would use social support from friends more for cyber-victimization.

Figure 3. Use of Coping by Situation. *p < .05; Participants rated how often they would use specific coping strategies on a 4-point scale; 1 = Not at all, 2 = A little, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = A lot.

Demographic Differences in the Use of Coping Strategies

In the repeated measures ANOVA, we found a main effect for gender (F(1, 282) = 20.40, p < .05), indicating that female adolescents reported using more coping strategies than male adolescents. We also found a significant interaction for gender x coping strategies (F(5, 278) = 9.20, p < .05; see Figure 4). Paired t-tests specified that female adolescents reported that they would use more distraction and social support from both friends and family/adults than male adolescents.

Figure 4. Use of Coping by Gender. *p < .05; Participants rated how often they would use specific coping strategies on a 4-point scale; 1 = Not at all, 2 = A little, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = A lot.

In addition, we found an interaction effect for having experienced cyber-victimization in the last 12 months x coping (F(5, 278) = 3.78, p < .05). Specifically, adolescents reported that they would use less problem solving and social support from family/adults with cyber-victimization if they had a recent cyber-victimization event in the last year compared to if they did not have a recent history of cyber-victimization.

A significant 3-way gender x coping x situation interaction also emerged (F(5, 278) = 3.67, p < .05). Paired t-tests revealed that female adolescents reported that they would use social support from friends more for cyber-victimization than for in-person victimization (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Use of Coping by Situation and Gender. *p < .05; Participants rated how often they would use specific coping strategies on a 4-point scale; 1 = Not at all, 2 = A little, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = A lot.

Predictors of Coping Efficacy

To examine predictors of coping efficacy, we computed one hierarchical linear regression for each type of victimization.

Coping strategies predicting coping efficacy for in-person victimization. In the first step, the background variables (gender, grade, race, whether they had experienced in-person victimization in the last 12 months) accounted for 4% of the variance in coping efficacy; 8th graders reported higher levels of coping efficacy than 7th graders, (β = .18, p < .05). In the second step, coping strategies accounted for an additional and significant 35% of the variance in perceived coping efficacy. Problem solving (β = .43, p < .05) positively predicted perceived coping efficacy for in-person stressors, while retaliation was inversely related to perceived coping efficacy (β = -.24, p < .05; see Table 4).

Coping strategies predicting coping efficacy for cyber-victimization. In the first step, the background variables (gender, grade, race, whether they had experienced cyber-victimization in the last 12 months) accounted for 6% of the variance in coping efficacy; 8th graders (β = .15, p < .05), female adolescents (β = .14, p < .05), and students with no exposure to cyber-victimization in the last 12 months (β = -.15, p < .05) reported higher levels of coping efficacy, compared to 7th graders, male adolescents, and those who were exposed to a cyber-victimization situation, respectively. In the second step, coping strategies were entered, which accounted for an additional 37% of the variance in perceived coping efficacy. Problem solving (β = .39, p < .05), social support from family/adult (β = .16, p < .05), and social support from friends (β = .13, p < .05) positively predicted perceived coping efficacy for cyber-victimization, while retaliation was inversely related to perceived coping efficacy (β = -.11, p < .05; see Table 4).

Table 4. Hierarchical Regressions Predicting Coping Efficacy for In-Person and Cyber-Victimization.

|

Variable |

In-Person Victimization |

Cyber-Victimization |

||||||||||

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||||||

|

B |

SE B |

β |

B |

SE B |

β |

B |

SE B |

β |

B |

SE B |

β |

|

|

Gendera |

.05 |

.10 |

.03 |

-.20 |

.09 |

-.12 |

.26 |

.11 |

.14* |

-.08 |

.10 |

-.04 |

|

Gradeb |

.29 |

.10 |

.18* |

.28 |

.08 |

.17* |

.29 |

.11 |

.15* |

.23 |

.09 |

.12* |

|

Racec |

.09 |

.10 |

.05 |

.10 |

.09 |

.06 |

-.13 |

.12 |

-.06 |

-.07 |

.10 |

-.03 |

|

Experienced an in-person/cyber-victimization event in the last 12-months |

-.04 |

.12 |

-.02 |

.05 |

.10 |

.02 |

-.28 |

.11 |

-.15* |

-.07 |

.10 |

-.04 |

|

Distancing |

.00 |

.06 |

.00 |

|

|

|

.10 |

.06 |

.08 |

|||

|

Distraction |

.07 |

.06 |

.07 |

|

|

|

.06 |

.07 |

.06 |

|||

|

Social Support – Family/adult |

.07 |

.06 |

.07 |

|

|

|

.16 |

.06 |

.16* |

|||

|

Social Support - Friend |

.03 |

.06 |

.03 |

|

|

|

.13 |

.06 |

.13* |

|||

|

Problem Solving |

.53 |

.07 |

.43* |

|

|

|

.52 |

.07 |

.39* |

|||

|

Retaliation |

-.28 |

.06 |

-.24* |

|

|

|

-.13 |

.06 |

-.11* |

|||

|

R2 |

.04 |

.35 |

.06 |

.37 |

||||||||

|

F for change in R2 |

2.70* |

23.56* |

4.38* |

23.05* |

||||||||

|

Note. a Gender: 0 = Male, 1 = Female. bRace: 0 = White, 1 = Other. cGrade: 7th = 0, 8th = 1. dPS = Problem solving; SS-Friend = Social Support-Friend; SS-Family = Social Support-Family. |

||||||||||||

Discussion

Our study investigated how adolescents would cope with in-person and cyber-victimization. We identified gender differences in coping strategies and explored perceptions of coping efficacy by victimization type. Exploring the similarities and differences in adolescent coping with in-person and cyber-victimization is important for informing intervention programming for adolescents. It is critical that interventionists highlight coping strategies that are conceptually efficacious and endorsed by adolescents as being beneficial to them.

In the current study, we predicted that there would be significant differences in the use of problem solving, social support from friends, and social support from family/adults for coping with in-person and cyber-victimization. We found that for in-person victimization, adolescents reported that they would use more strategies overall when compared to coping with cyber-victimization. Specifically, adolescents reported they would use more distancing, distraction, problem solving, retaliation, and social support from family/adults when coping with in-person victimization.

It is possible that because adolescents experience in-person victimization more frequently than cyberbullying, they are more willing to try a variety of methods when coping with in-person victimization problems. Of significance is the fact that 79% of adolescents reported experiencing at least one in-person victimization situation in the past year, compared to 53% who reported experiencing at least one cyber-victimization situation in the past year. Also, if the in-person victimization is persistent and repeated over time, adolescents may use many different methods of coping to either stop the perpetrator from victimizing them or to help themselves feel better. Craig, Pepler, and Blais (2007) found that when students are victimized repeatedly, they feel a lack of power as the victimization becomes increasingly harder to stop. Adolescents in these kinds of situations may feel a lack of power and therefore begin to use as many coping strategies as possible in an attempt to stop the victimization or improve their emotional state.

Gender differences emerged in this study as well. Compared to male adolescents, female adolescents indicated that they would use more coping strategies in general, and specifically, they reported they would use more distraction and social support from their friends and family/adults. We hypothesized that female adolescents would use more social support from friends and family/adults as this finding has been supported in past literature (Frisén et al., 2014).

It is common for gender differences to emerge when evaluating adolescent coping. The results of the current study are consistent with existing literature exploring adolescent coping with in-person stressors. In the literature, female adolescents used more social support (Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, 2015) to cope compared to male adolescents. Our results are also consistent with the limited research available assessing the gender differences that exist when coping with cyber-victimization. For instance, in Machmutow et al. (2012), female adolescents were more likely to recommend the use of social support coping strategies to a victim in a hypothetical situation. Thus, we may infer that the strategies recommended are likely the strategies an adolescent would use if she were in a similar situation. In addition, Frisén et al. (2014) and Li (2006) explored gender differences in coping strategies used by cyber-victims. Their results also support the current findings, suggesting that female adolescents, compared to male adolescents, were more likely to reach out for social support. It is also suspected that female adolescents are socialized to use more social support (Bird & Harris, 1990) and there is some evidence that interpersonal stress occurs more frequently and is more distressing to female adolescents than male adolescents (Hankin, Mermelstein, & Roesch, 2007; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). However, given the limited research evaluating such differences in coping with cyber-victimization, more research is needed to further explore and/or confirm these findings.

An additional aim of this study was to examine adolescents’ perceptions of how well they would cope with peer stressors, and if this was related to the coping strategy they reported they would use. Perceived coping efficacy was shown to be positively related to problem solving, whereas retaliation inversely predicted coping efficacy for both situations. These findings appear to be consistent with research on youth’s coping efficacy with other stressors (e.g., peer stress, transition to high school). Reliance on approach coping strategies (e.g., problem solving, social support) was positively related to coping efficacy, while reliance on avoidance strategies (e.g., distancing), was negatively related to coping efficacy (Griffith et al., 2000). The present study suggests similar patterns in terms of cyber-victimization coping, which is consistent with other research evaluating the relation between coping strategies and improved and ineffective coping (Jacobs et al., 2014). More specifically, their study revealed that a reliance on problem-focused coping (also see Palladino, Nocentini, & Menesini, 2012; Price & Dalgleish, 2010; Völlink et al., 2013) was strongly associated with improved coping, whereas other strategies like passive coping (also see Dehue, Bolman, & Völlink, 2008; Palladino et al., 2012; Völlink et al., 2013), lack of social support (also see Wolak, Mitchell, Finkelhor, 2007), and emotion-focused coping (e.g., retaliation; also see Dehue et al., 2008; Völlink et al., 2013) were associated with ineffective coping. In the present study, retaliation was found to be inversely associated with efficacy, suggesting that adolescents did not feel the situation turned out well in retrospect. Longitudinal research investigating the frequency of cyber-victimization, depressive symptoms, and coping found that cyber-victimization was positively associated with retaliation, thus suggesting that victims of this type of stress may use retaliation to cope. In addition, the use of this coping strategy, for in-person victimization, has been linked to further victimization and perpetuation of the problem (Craig et al., 2007) with other researchers discouraging the use of this strategy for the same reason (Price & Dalgleish, 2010). It is suspected that this is also the case for cyber-victimization.

While we predicted the outcomes for problem solving and retaliation for in-person and cyber-victimization, our hypothesis was only partially supported. Social support from friends and family/adults was shown to be positively associated with coping efficacy, but only for cyber-victimization. In light of the research suggesting that many adolescents do not tell adults when cyber-victimization is happening (Agatston et al., 2007; Juvonen & Gross, 2008; Li, 2007), we were surprised to find that in our study adolescents believed they would feel more efficacious if they sought out help from an adult. We suspect that when coping with cyber-victimization, adolescents may desire adult support to navigate these complex situations. Therefore, they reported they believe they would seek out social support from friends and family to be effective. However, it is important to keep in mind that there were differences in self-reported perceived coping between those adolescents who did and did not experience cyber-victimization in the past year. Specifically, those who had a recent experience with cyber-victimization said they would use less social support from adults and family than those who had not had a recent cyber-victimization event. This difference may explain why our results were unexpected. It will be important for future research to specifically evaluate how self-reported coping differs in youths who have experienced recent cyber-victimization. It is possible that students may believe they would seek out adult social support before a cyber-victimization event occurs, but then choose different strategies to cope when an actual event happens.

Our findings should be considered in the context of several limitations, specifically in terms of methodology. First, it could be potentially advantageous to use a different methodology to assess coping and coping efficacy. For instance, instead of using only self-report methods, gaining other sources’ perspectives (e.g., teachers, parents) of the adolescent’s coping and coping efficacy would likely be beneficial. This would provide a unique perspective and would also address the methodological limitation of shared method bias, that is, inflated correlations between coping strategies and coping efficacy because both variables were reported by the same individual whose biases would affect responses on each measure.

Second, when evaluating coping with victimization, the study design required adolescents to report on what they would do to cope. Because this can introduce biases, another option would be to design a longitudinal study that would examine how adolescents cope immediately after encountering a specific stressor, that is, in the moment. This would allow the adolescents to record (in a diary or using ecological momentary assessment [EMA]) how they cope with victimization stressors as the stressors are experienced, which would allow for more accurate reporting of coping strategies and perceived coping efficacy. These response methods would allow adolescents to report, in their own words, how they coped with the situation rather than answering closed-ended questions pre-determined by the researcher. However, the methodology we used allowed participants to remain anonymous, possibly increasing their willingness to be honest in their responses, specifically as it pertains to less socially acceptable coping styles (e.g., retaliation). In addition, the survey method that we used allowed for a less intrusive and time-consuming way to collect data on participants’ coping, potentially decreasing attrition during data collection and thus increasing the representativeness of our sample.

Third, our evaluation of perceived coping efficacy was assessed globally rather than by individual coping strategy. There are some perceived benefits for future research to investigate the efficacy of each individual type of coping (e.g., problem solving, retaliation, distraction) to investigate their nuanced differences. It would be expected that more specific conclusions about coping efficacy could be drawn from a direct analysis of individual coping strategies and coping efficacy.

Fourth, we did not have adolescents generate their own in-person victimization or cyber-victimization situations—the adolescents were provided with a list of common bullying situations. It is possible that some of the adolescents surveyed did not experience any of the situations provided but had experienced a different victimization situation. In the current experimental design, students who did not experience any of the listed situations but who experienced an unlisted situation, would have been categorized into the “no exposure to victimization” category, when, in fact, they experienced a victimization episode. Still, the listed in-person victimization and cyber-victimization problems are quite common in the literature, so we can be reasonably confident the situations are a good representation of the most common ones adolescents are experiencing. However, in this coping survey, adolescents were asked to respond to a generic in-person situation (i.e., Another kid said mean things or did mean things to me in person) and a generic cyber situation (i.e., Another kid said mean things or did mean things to me on the internet, through text-messaging, or on a cell phone), rather than a very specific individually experienced one.

Fifth, in effort to be as inclusive as possible, we did not limit our study to only those students who had experienced recent in-person or cyber-victimization. Rather, we asked students what they would do to cope with in-person or cyber-victimization hypothetically. We followed up our analysis by comparing the self-reported coping strategies adolescents reported of those who had and had not experienced recent victimization and got mixed results. In terms of cyber-victimization, those who had a history of recent online victimization reported less use of problem solving and social support from adults and family members. However, we did not find the same pattern with in-person victimization. Self-reported coping was not related to history of recent in-person victimization. Moving forward, it will be important for researchers to evaluate the role history of victimization plays in self-reported coping, especially for cyber-victimization, as it appears that for some strategies perceived coping may differ from actual coping.

The present findings also suggest several avenues for future research. First, it is possible that resources could be redirected to support combined in-person and cyber-victimization interventions that are focused on training coping strategies for both situations. However, to determine if such programming would be effective, researchers would need to evaluate these programs to determine whether intervention youth improved in their coping efficacy compared to control group youth, and whether improvement was similar for each type of stressor. Such combined programming could be beneficial because it would save on resources, including time and money. Additionally, interventionists may be able to capitalize on the similarities between in-person and cyber-victimization coping (i.e., encouraging problem solving, discouraging retaliation) by facilitating discussion of these strategies for both situations at the same time. Second, given the quickly growing research in cyber-victimization coping, it is important for researchers to continue validating coping measures, such as the Self-report Coping measure (Causey & Dubow, 1992), that are adapted for cyber-victimization stressors to continue investigating how adolescents are coping with cyber-victimization. However, as noted above, other methods of assessing adolescents’ coping should be included as well, such as diary methods which can assess in-the-moment coping strategies as a response to specific stressor incidents. Lastly, given the support we found for overlap between in-person and cyber-victimization coping strategies, future research should seek to support this finding in larger, nationally representative samples using theory-driven analytical methods.

Conclusion

Our results indicated that adolescents perceive some coping strategies to be more effective than others for both types of victimization. Prevention programing for both types of victimization should include a discussion of effective coping strategies so interventionists can encourage the use of problem solving and/or social support strategies and discourage the use of retaliation. This may seem obvious, but adolescents may benefit from learning that their peers do not report efficacy when considering the use of retaliation when coping with both in-person and cyber-victimization, thus decreasing their reliance on these strategies through social consensus.

Further, discussing the benefits of using social support from parents and friends should be emphasized in cyber-victimization prevention programming. Research suggests that a relatively low number of youth seek out social support from adults when coping with cyber-victimization (Agatston et al., 2007), and the current study found that adolescents are more likely to use social support from their friends in cyber-victimization situations and social support from family/adults in in-person victimization situations. However, social support from both friends and family/adults is related to efficacy in cyber-victimization situations. Programming can educate adolescents through discussion that their peers report efficacy when considering the use of social support from friends and family/adults, which may make them more likely to seek social support from family and other adults in their lives (e.g., teachers) when coping with cyber-victimization situations. Further, these programs can combat unhelpful perceptions that many adolescents hold about the use of social support from family/adults in response to cyber-victimization (Dehue et al., 2008; Juvonen & Gross, 2008; Mishna et al., 2009; Slonje et al., 2013)

Prevention programming that discusses efficacious coping strategies will enhance already existing prevention programs by communicating consistent messages to adolescents about what to do/not to do when victimization (in-person and online) occurs. Additionally, we can use this information to begin to combat the expectation that adolescents have about needing to handle complex online situations on their own. Interventions focused on promoting the use of evidence-based coping strategies will support adolescents in developing a healthy relationship with technology in an effort to decrease the negative impact that online victimization can have on adolescents.

Appendix A: Coping with Cyber-Victimization

For each item on the list below, circle how much you would do or think each thing if other kids say mean things or do mean things to you ON THE INTERNET, THROUGH TEXT-MESSAGES, OR ON CELL PHONES.

|

If other kids say mean things or do mean things to me ON THE INTERNET, THROUGH TEXT-MESSAGES, OR ON CELL PHONES, I would… |

Not at all (1) |

A little (2) |

Some-times (3) |

A (4) |

|

1. tell a friend or family member what happened... |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

2. try to think of different ways to solve it… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

3. make believe nothing happened… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

4. do to that person what he/she did to me because I felt sad or angry… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

5. talk to somebody about how it made me feel…a |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

6. change something so things would work out… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

7. think about happy things to take my mind off the problem or how I was feeling… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

8. get help from a friend… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

9. decide on one way to deal with the problem and do it… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

10. forget the whole thing… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

11. keep my mind off the problem by: (Remember to circle a number) Check all that you did: ¨ Exercise ¨ Play video games ¨ See friends ¨ Do a hobby ¨ Watch TV ¨ None of these |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

12. ask a friend for advice … |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

13. tell myself it doesn’t matter… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

14. ask a family member for advice… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

15. know there were things I could do to make it better… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

16. refuse to think about it… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

17. yell at that person to let off steam… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

18. ask another kid who had this problem what he or she did… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

19. go over in my mind what to do or say… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

20. do something else to take my mind off of it… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

21. imagine something really fun or exciting happening in my life… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

22. curse at that person… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

23. try to understand why it happened to me…a |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

24. say I don’t care… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

25. ignore it when people say something about it… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

26. get mad at the person and throw something at him/her or hit him/her… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

27. get help from a family member… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

28. talk to the teacher, counselor, or another adult at school about it… |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |