Compare and despair or compare and explore? Instagram social comparisons of ability and opinion predict adolescent identity development

Vol.14,No.2(2020)

Whilst there is an emerging literature concerning social comparisons on social networking sites (SNSs), very little is known about the extent to which such behaviours inform adolescent identity. Drawing upon the three-factor model of identity development (Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008), this study seeks to determine the relationship between Instagram comparisons of ability and opinion and three identity processes: commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment. 177 British adolescents responded to a paper survey (Mage= 15.45; Female, 54.8%) between December 2018 and February 2019. Instagram social comparisons of ability were positively associated with commitment and in-depth exploration, whilst their relationship with reconsideration of commitment was moderated by gender. In contrast, Instagram social comparisons of opinion were positively related with in-depth exploration and reconsideration of commitment. Findings suggest that although both forms of social comparison behaviour may evoke adolescents to explore their identity, Instagram social comparisons of ability may have less maladaptive identity implications for adolescent males.

Identity development; identity dimensions; variable-centred; adolescent; Instagram; social comparison

Edward John Noon

Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, United Kingdom

Edward Noon is an Associate Lecturer and PhD Candidate at Sheffield Hallam University, England. His research interests involve social networking sites and adolescent development. His doctoral research concerns Instagram social comparisons and adolescent identity development.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Arnett, J. J. (2015). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Berzonsky, M. D. (1990). Self-construction over the lifespan: A process perspective on identity formation. In G. J. Neimeyer & R. A. Neimeyer (Eds.), Advances in personal construct psychology (pp. 155–186). JAI Press.

Berzonsky, M. D. (2011). A social-cognitive perspective on identity construction. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 55–76). Springer.

Brandenberg, G., Ozimek, P., Bierhoff, H.-W., & Janker, C. (2019). The relation between use intensity of private and professional SNS, social comparison, self-esteem, and depressive tendencies in the light of self-regulation. Behaviour & Information Technology, 38(6), 578–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1545049

Butzer, B., & Kuiper, N. A. (2006). Relationships between the frequency of social comparisons and self-concept clarity, intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety, and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(1), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.017

Buunk, B. P., Collins, R. L., Taylor, S. E., VanYperen, N. W., & Dakof, G. A. (1990). The affective consequences of social comparison: Either direction has its ups and downs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1238–1249. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.6.1238

Chou, H.-T. G., & Edge, N. (2012). ‘‘They are happier and having better lives than I am’’: The impact of using Facebook on perceptions of others’ lives. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(2), 117–121. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0324

Corcoran, K., Crusius, J., & Mussweiler, T. (2011). Social comparison: Motives, standards, and mechanisms. In D. Chadee (Ed.), Theories in social psychology (pp. 119–139). Wiley-Blackwell.

Cramer, E. M., Song, H., & Drent, A. M. (2016). Social comparison on Facebook: Motivation, affective consequences, self-esteem, and Facebook fatigue. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 739–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.049

Crocetti, E. (2017). Identity formation in adolescence: The dynamic of forming and consolidating identity commitments. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12226

Crocetti, E., Branje, S., Rubini, M., Koot, H. M., & Meeus, W. (2017). Identity processes and parent-child and sibling relationships in adolescence: A five-wave multi-informant longitudinal study. Child Development, 88(1), 210–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12547

Crocetti, E., Jahromi, P., & Meeus, W. (2012). Identity and civic engagement in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35(3), 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.08.003

Crocetti, E., & Meeus, W. (2014). The identity statuses: Strengths of a person-centered approach. In K. C. McLean, & M. Syed (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of identity development (pp. 97–114). Oxford University Press.

Crocetti, E., Rubini, M., & Meeus, W. (2008). Capturing the dynamics of identity formation in various ethnic groups: Development and validation of a three-dimensional model. Journal of Adolescence, 31(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.09.002

Crocetti, E., Rubini, M., Berzonsky, M. D., & Meeus, W. (2009). Brief report: The Identity Style Inventory – Validation in Italian adolescents and college students. Journal of Adolescence, 32(2), 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.04.002

Crocetti, E., Rubini, M., Luyckx, K., & Meeus, W. (2008). Identity formation in early and middle adolescents from various ethnic groups: From three dimensions to five statuses. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(8), 983–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9222-2

Crocetti, E., Schwartz, S. J., Fermani, A., Klimstra, T., & Meeus, W. (2012). A cross-national study of identity status in Dutch and Italian adolescents: Status distributions and correlates. European Psychologist, 17(3), 171–181. http://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000076

Crocetti, E., Schwartz, S. J., Fermani, A., & Meeus, W. (2010). The Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS): Italian validation and cross-national comparisons. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(3), 172–186. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000024

Crocetti, E., Sica, L. S., Schwartz, S. J., Serafini, T., & Meeus, W. (2013). Identity styles, dimensions, statuses, and functions: Making connections among identity conceptualizations. European Review of Applied Psychology, 63(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2012.09.001

de Vries, D. A., & Kühne, R. (2015). Facebook and self-perception: Individual susceptibility to negative social comparison on Facebook. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 217–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.029

de Vries, D. A., Möller, A. M., Wieringa, M. S., Eigenraam, A. W., & Hamelink, K. (2018). Social comparison as the thief of joy: Emotional consequences of viewing strangers’ Instagram posts. Media Psychology, 21(2), 222–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2016.1267647

Dimitrova, R., Crocetti, E., Buzea, C., Jordanov, V., Kosic, M., Tair, E., Taušová, J., van Cittert, N., & Uka, F. (2016). The Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS): Measurement invariance and cross-national comparisons of youth from seven European countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 32(2), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000241

Erikson E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. W. W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. W. W. Norton & Company.

Feinstein, B. A., Hershenberg, R., Bhatia, V., Latack, J. A., Meuwly, N., & Davila, J. (2013). Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: Rumination as a mechanism. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(3), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033111

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Fox, J., & Moreland, J. J. (2015). The dark side of social networking sites: An exploration of the relational and psychological stressors associated with Facebook use and affordances. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.083

Hair, J. F. Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

Harter, S. (2012). The construction of the self: Developmental and sociocultural foundations (2nd ed.). Guildford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Huang, Y.-T., & Su, S.-F. (2018). Motives for Instagram use and topics of interest among young adults. Future Internet, 10(8), Article 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi10080077

Karaś, D., & Cieciuch, J. (2015). A domain-focused approach to identity formation. Verification of the three-dimensional model in various life domains in emerging adults. Studia Psychologiczne, 54(3), 61–73. http://www.studiapsychologiczne.pl/A-domain-focused-approach-to-identity-formation-Verification-of-the-three-dimensional-model-in-various-life-domains-in-emerging-adults,61107,0,2.html

Klimstra, T. A., Hale, W. W. III., Raaijmakers, Q. A. W., Branje, S. J. T, & Meeus, W. H. J. (2010). Identity formation in adolescence: Change or stability? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(2), 150–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9401-4

Kroger, J. (2004). Identity in formation. In K. Hoover (Ed.), The future of identity: Centennial reflections on the legacy of Erik Erikson (pp. 61–76). Lexington Books.

Lee, E., Lee, J.-A., Moon, J. H., & Sung, Y. (2015). Pictures speak louder than words: Motivations for using Instagram. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(9), 552–556. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0157

Lee, S. Y. (2014). How do people compare themselves with others on social network sites?: The case of Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 32, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.009

Lim, M., & Yang, Y. (2015). Effects of users’ envy and shame on social comparison that occurs on social network services. Computers in Human Behavior, 51(Part A), 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.013

Lin, R., & Utz, S. (2015). The emotional responses of browsing Facebook: Happiness, envy, and the role of tie strength. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.064

Liu, J., Li, C., Carcioppolo, N., & North, M. (2016). Do our Facebook friends make us feel worse? A study of social comparison and emotion. Human Communication Research, 42(4), 619–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12090

Luong, K. T., Knobloch-Westerwick, S., & Frampton, J. (2019). Temporal self impacts on media exposure & effects: A test of the Selective Exposure Self- and Affect-Management (SESAM) model. Media Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1657898

Luyckx, K., Klimstra, T. A., Duriez, B., Van Petegem, S., & Beyers, W. (2013). Personal identity processes from adolescence through the late 20s: Age trends, functionality, and depressive symptoms. Social Development, 22(4), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12027

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023281

Marcia, J. E. (1980). Identity in adolescence. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 159–187). Wiley.

Marcia, J. E. (1993). The status of the statuses: Research review. In J. E. Marcia, A. S. Waterman, D. R. Matteson, S. L. Archer, & J. L. Orlofsky (Eds.), Ego Identity: A handbook for psychosocial research (pp. 22–41). Springer.

Marcia, J. E. (2001). A commentary on Seth Schwartz's, review of identity theory and research. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 1(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532706XMARCIA

Meeus, A., Beullens, K., & Eggermont, S. (2019). Like me (please?): Connecting online self-presentation to pre- and early adolescents’ self-esteem. New Media & Society, 21(11–12), 2386–2403. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819847447

Meeus, W. (2011). The study of adolescent identity formation 2000-2010: A review of longitudinal research. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00716.x

Michikyan, M., Dennis, J., & Subrahmanyam, K. (2015). Can you guess who I am? Real, ideal, and false self-presentation on Facebook among emerging adults. Emerging Adulthood, 3(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696814532442

Morry, M. M., Sucharyna, T. A., & Petty, S. K. (2018). Relationship social comparisons: Your Facebook page affects my relationship and personal well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 83, 140–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.038

Morsunbul, U., Crocetti, E., Cok, F., & Meeus, W. (2014). Brief report: The Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS): Gender and age measurement invariance and convergent validity of the Turkish version. Journal of Adolescence, 37(6), 799–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.05.008

Newman, B. M., & Newman, P. R. (2012). Development through life: A psychosocial approach (11th ed.). Wadsworth.

Noon, E. J. (2018). Social network sites, social comparison, and adolescent identity development: A small-scale quantitative study. PsyPAG Quarterly, 109, 21–25. http://www.psypag.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Quarterly-December-2018.pdf

Noon, E. J., & Meier, A. (2019). Inspired by friends: Adolescents' network homophily moderates the relationship between social comparison, envy, and inspiration on Instagram. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(12), 787–793. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0412

Ofcom. (2018a). Children and parents: Media use and attitudes report 2018. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/134907/children-and-parents-media-use-and-attitudes-2018.pdf

Ofcom. (2018b). Adults’ media use and attitudes report. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/113222/Adults-Media-Use-and-Attitudes-Report-2018.pdf

Palmeroni, N., Claes, L., Verschueren, M., Bogaerts, A., Buelens, T., & Luyckx, K. (2019). Identity distress throughout adolescence and emerging adulthood: Age trends and associations with exploration and commitment processes. Emerging Adulthood. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818821803

Park, S. Y., & Baek, Y. M. (2018). Two faces of social comparison on Facebook: The interplay between social comparison orientation, emotions, and psychological well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 79, 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.028

Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2017). Digital self-harm among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(6), 761–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.06.012

Royal Society for Public Health. (2017a). #StatusOfMind: Social media and young people's mental health and wellbeing. https://www.rsph.org.uk/uploads/assets/uploaded/d125b27c-0b62-41c5-a2c0155a8887cd01.pdf

Royal Society for Public Health. (2017b). Instagram ranked worst for young people's mental health. https://www.rsph.org.uk/about-us/news/instagram-ranked-worst-for-young-people-s-mental-health.html

Saadat, S. H., Shahyad, S., Pakdaman, S., & Shokri, O. (2017). Prediction of social comparison based on perfectionism, self-concept clarity, and self-esteem. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 19(4), Article e43648. https://dx.doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.43648

Salimkhan, G., Manago, A. M., & Greenfield, P. M. (2010). The construction of the virtual self on MySpace. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 4(1), Article 1. https://cyberpsychology.eu/article/view/4231/3275

Sheldon, P., & Bryant, K. (2016). Instagram: Motives for its use and relationship to narcissism and contextual age. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.059

Smith, R. H. (2000). Assimilative and contrastive emotional reactions to upward and downward social comparisons. In J. Suls & L. Wheeler (Eds.), The Plenum series in social/clinical psychology. Handbook of social comparison: Theory and research (pp. 173–200). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Spies Shapiro, L. A., & Margolin, G. (2014). Growing up wired: Social networking sites and adolescent psychosocial development. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-013-0135-1

Suls, J., & Bruchmann, K. (2013). Social comparison and persuasion in health communications. In L. Martin & R. DiMatteo (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Health Communication, Behavior Change, and Treatment Adherence (pp. 251-266). Oxford University Press.

Suls, J., Martin, R., & Wheeler, L. (2000). Three kinds of opinion comparison: The triadic model. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(3), 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0403_2

Taylor, S. E., & Lobel, M. (1989). Social comparison activity under threat: Downward evaluation and upward contacts. Psychological Review, 96(4), 569–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.569

Tobin, S. J., Vanman, E. J., Verreynne, M., & Saeri, A. K. (2015). Threats to belonging on Facebook: Lurking and ostracism. Social Influence, 10(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2014.893924

Toma, C. L., & Hancock, J. T. (2013). Self-affirmation underlies Facebook use. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(3), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212474694

Tsang, S. K. M., Hui, E. K. P., & Law, B. C. M. (2012). Positive identity as a positive youth development construct: A conceptual review. The Scientific World Journal, 2012, Article 529691. https://doi.org/10.1100/2012/529691

Valkenburg, P. M., Peter, J., & Schouten, A. P. (2006). Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9(5), 584–590. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.584

Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Okdie, B. M., Eckles, K., & Franz, B. (2015). Who compares and despairs? The effect of social comparison orientation on social media use and its outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.026

Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Roberts, L. R., & Eckles, K. (2014). Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3(4), 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000047

Wills, T. A. (1981). Downward comparison principles in social psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 90(2), 245–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.90.2.245

Yang, C.-c., & Brown, B. B. (2016). Online self-presentation on Facebook and self development during the college transition. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(2), 402–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0385-y

Yang, C.-c., Holden, S. M., & Carter, M. D. K. (2018). Social media social comparison of ability (but not opinion) predicts lower identity clarity: Identity processing style as a mediator. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(10), 2114–2128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0801-6

Yang, C.-c., Holden, S. M., Carter, M. D. K., & Webb, J. J. (2018). Social media social comparison and identity distress at the college transition: A dual-path model. Journal of Adolescence, 69, 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.09.007

Yang, C.-c., & Robinson, A. (2018). Not necessarily detrimental: Two social comparison orientations and their associations with social media use and college social adjustment. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.020

Yau, J. C., & Reich, S. M. (2019). “It's just a lot of work”: Adolescents’ self‐presentation norms and practices on Facebook and Instagram. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29(1), 196–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12376

Yurchisin, J., Watchravesringkan, K., & McCabe, D. B. (2005). An exploration of identity re-creation in the context of Internet dating. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 33(8), 735–750. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2005.33.8.735

Zimmermann, G., Mahaim, E. B., Mantzouranis, G., Genoud, P. A., & Crocetti, E. (2012). Brief report: The Identity Style Inventory (ISI-3) and the Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS): Factor structure, reliability, and convergent validity in French-speaking university students. Journal of Adolescence, 35(2), 461–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.11.013

Editorial Record:

First submission received:

July 19, 2019

Revisions received:

February 4, 2020

March 4, 2020

Accepted for publication:

March 5, 2020

Editor in charge:

Alexander Schouten

Introduction

Identity development is the primary psychosocial task of adolescence (Erikson, 1950), and over the past decade, young people have increasingly been using SNSs as platforms for self-expression, self-construction, and identity exploration (Patchin & Hinduja, 2017). To date, scholarship concerning SNSs and adolescent identity development has been dominated by the notion that such platforms represent convenient and powerful venues for self-disclosure and self-presentation. For example, studies have found intentional self-presentation on Facebook to be associated with self-reflection (Yang & Brown, 2016), and youth’s identity ‘state’ to be related to their SNS self-presentational style (Michikyan et al., 2015). Furthermore, posting/viewing ‘idealised’ versions of the self on SNSs has been found to support self-affirmation (Toma & Hancock, 2013), whilst the peer validation of the identities presented online can play an important role in boosting self-esteem (Meeus et al. , 2019; Valkenburg et al., 2006), validating self-concept (Salimkhan et al., 2010; Yurchisin et al., 2005), and engendering feelings of affiliation and belonging (Tobin et al., 2015).

However, as SNSs provide opportunities for, and at times prompt, their users to express themselves online (Spies Shapiro & Margolin, 2014), they also afford individuals abundant opportunities for social comparison (Cramer et al., 2016). Whilst scholars have started to investigate the consequences of SNS social comparisons, much of the extant literature has concerned their psycho-emotional outcomes, rather than their identity implications. Of the limited research that has been conducted regarding SNS social comparisons and identity development, participatory samples have consisted of emerging adults (ages 18-25) - rather than adolescents (ages 13-18), whilst generalist approaches to SNS social comparisons have been adopted, whereby respondents have reported their mean comparison behaviour across all SNSs (Yang, Holden, & Carter, 2018; Yang, Holden, Carter, & Webb, 2018). This approach does not enable us to understand the contexts in which the social comparisons measured occurred, and since it is possible that social comparison behaviour differs across platform (Yang, Holden, & Carter, 2018), differentiating between SNSs is necessary. With this in mind, drawing upon neo-Eriksonian conceptions of identity (Crocetti, Rubini, & Meeus, 2008), this study aims to determine how social comparison behaviours on popular image-based SNS Instagram associate with adolescent identity development.

Adolescent Identity Development

Erikson (1950, 1968) believed that the rapid biological changes associated with adolescence, their psychological reverberations, and new societal expectations trigger the need for young people to develop a coherent and synthesised sense of identity. Identity formation begins when one’s childhood identifications - the values and attributes previously adopted from significant others - are no longer deemed satisfactory (Kroger, 2004). To solve one’s identity struggles, sustained reflection upon one’s past, present, and future selves is requisite: adolescents must begin to re-examine, transform, and re-organise their childhood identifications in line with their own talents, interests, and abilities, and identify valued life goals and aspirations (Newman & Newman, 2012). With the countless options and alternatives before them, adolescents tend to experiment with a range of differing vocations, ideologies, and relationships in their quest to overcome this “war within themselves”, and find an identity that truly ‘fits’ (Erikson, 1968, p. 17).

The most influential empirical elaboration of Erikson's identity theory is Marcia's (1966) identity status paradigm. Marcia (1966) conceptualised identity development as a process of exploration and commitment, where exploration refers to the active questioning of various identity alternatives, and commitment involves making a firm choice in an identity domain. Based on the amount of exploration and commitment adolescents experience, Marcia (1966) found that young people can be assigned to one of four identity statuses: in the achievement status, adolescents have explored their identity and made commitments; in the foreclosure status, adolescents have made commitments with little or no exploration; in the moratorium status, adolescents are actively exploring their identity but are yet to form firm commitments; and in the diffusion status, young people have not made commitments, nor are they exploring their identity. Whilst based on the cross-tabulation of exploration and commitment, the four statuses were theorised to vary hierarchically in terms of self-regulatory maturity and complexity of social functioning (Marcia, 1966). A significant amount of research has drawn upon the identity status paradigm, and findings have consistently shown that the identity statuses relate differently to a range of external correlates which reflect this hierarchy, including personality characteristics and interpersonal behaviours (for review see Marcia, 1993).

Since the identity status paradigm intended to measure the outcome of identity conflict during late adolescence (Marcia, 1980), much of the research that has drawn upon this framework has sought to classify individuals. However, several scholars - including Marcia (1993) himself - have noted the importance of studying the process of identity development, rather than just its outcomes. Over the past few decades, several theoretical models have been developed which seek to extend the work of Erikson (1950) and Marica (1966) to better capture the process of identity development during adolescence. One prevailing approach in the literature is the three-factor model proposed by Crocetti, Rubini, and Meeus (2008).

The Three-Factor Model

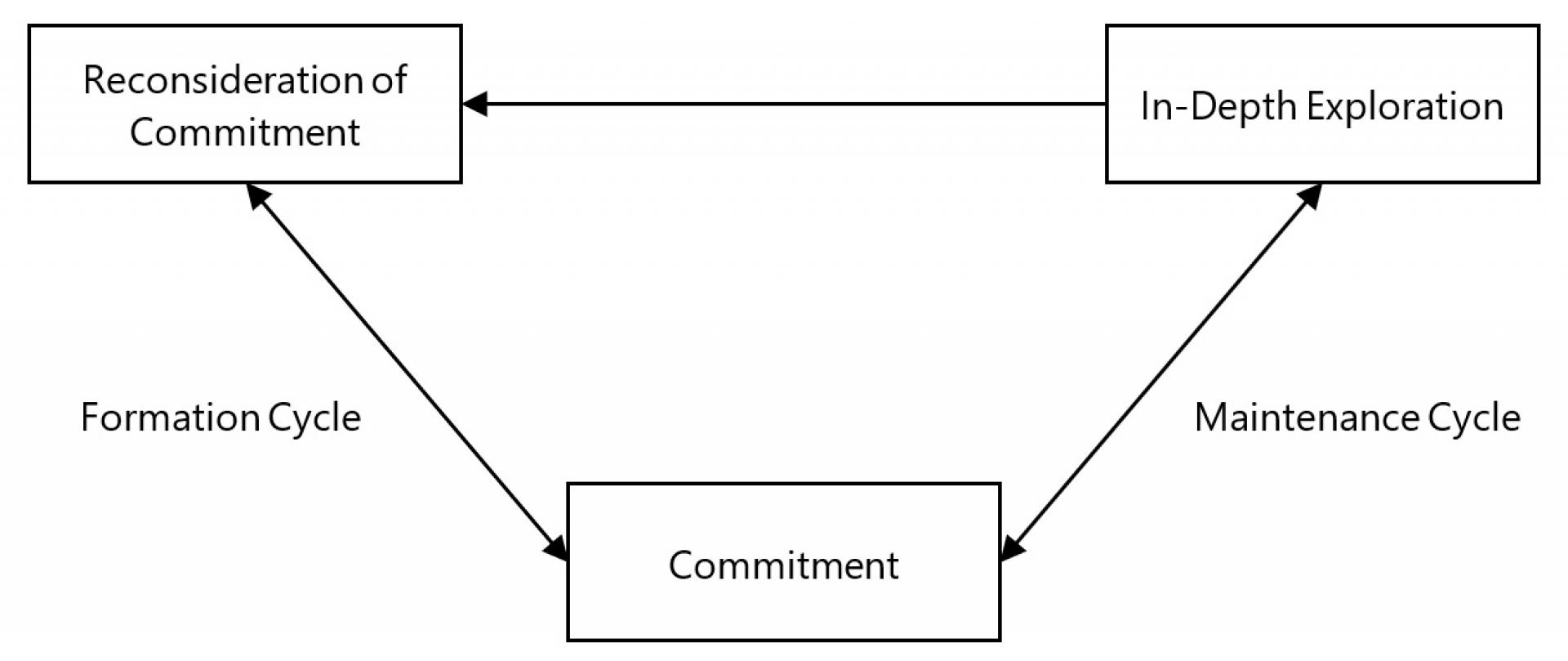

Crocetti, Rubini, and Meeus (2008) hold that one’s identity is shaped and modified through the continuous interplay between three critical identity dimensions: commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment. Here, the authors define commitment as the “enduring choices that [individuals] make in various...domains and the self-confidence they derive from these choices” (Dimitrova et al., 2016, p. 120). Yet, in contrast to Marcia (1966) - who assessed only one form of exploration, the three-factor model distinguishes two exploratory dimensions: in-depth exploration and reconsideration of commitment. In-depth exploration occurs when individuals consciously reflect upon, and seek additional information about, their current commitments, whereas reconsideration of commitment involves comparing present commitments with alternatives.

The three-factor model (Figure 1) assumes that young people enter adolescence with some ideological and interpersonal commitments, most of which are internalised from parents or figures of authority; during adolescence, individuals can then decide whether they wish to maintain or revise their commitments through an iterative dual-cycle process (Crocetti, Schwartz, et al., 2012). Adolescents can explore their current commitments through in-depth exploration. If, following this process, adolescents believe their commitments to be consistent with their overall talents and potential, they are justified and validated. This ‘maintenance cycle’ demonstrates a synthesised identity, derived from growing confidence in one’s current commitments (Meeus, 2011). However, in-depth exploration can also become maladaptive, thus leading adolescents to doubt, or ruminate about, their current commitments. Should in-depth exploration lead adolescents to question their identity commitments, they are then able to utilise the identity ‘formation cycle’. Here, adolescents can compare and contrast their current commitments with more appealing alternatives, and should they deem their prior choices to be inadequate, they are revised (Crocetti, 2017). This cycle captures the troublesome and ‘crisis-like’ nature of identity formation, in that individuals are seeking to overcome the identity confusion caused by their current unsatisfactory commitments. Should a commitment be revised, it is then reconsidered once more, before being developed further through in-depth exploration.

Figure 1. Three-Factor Model of Identity.

Consistent with Eriksonian thought - which holds that identity synthesis is central to psychosocial functioning during adolescence, researchers adopting this variable-centred approach have found identity certainty (i.e., commitment) to be associated with several positive correlates at the individual, relational, and societal levels. For example, commitment is associated with high self-concept clarity (Crocetti et al., 2010); emotional stability (Crocetti & Meeus, 2014); strong peer and familial relationships (Crocetti et al., 2017; Crocetti, Rubini, & Meeus, 2008); and social responsibility, volunteering, and civic engagement (Crocetti, Jahromi, & Meeus, 2012). In terms of in-depth exploration, researchers have empirically evidenced its adaptive and maladaptive implications: although this dimension is positively associated with agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to new experiences (Crocetti, Rubini, & Meeus, 2008), it is also positively related with internalising problems, and negatively associated with self-concept clarity and emotional stability (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, & Meeus, 2008; Crocetti et al., 2010). In contrast, reconsideration of commitment is negatively associated with self-concept clarity, positive personality characteristics, and familial relationships, and positively related with depression and anxiety (Crocetti, Rubini, & Meeus, 2008; Crocetti et al., 2010). Such results emphasise the importance of identity synthesis for adolescent psychosocial functioning and adjustment, and below, I hypothesise how Instagram social comparison behaviour could relate to these three identity processes (i.e., commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment).

Instagram Social Comparisons and Adolescent Identity Development

According to Leon Festinger (1954), individuals have an innate drive to gain accurate and stable self-assessments, and in the absence of objective criteria, they often look to others to evaluate their abilities and opinions. Whilst Festinger’s (1954) original theory emphasised self-evaluation as the primary motive for social comparisons, research has since suggested there are several other common motives for comparing the self to others, including self-improvement (Taylor & Lobel, 1989) and self-enhancement (Wills, 1981). Though social comparisons may also occur spontaneously or unconsciously (Suls & Bruchmann, 2013), they are, nevertheless, a major mechanism of self-knowledge, and can have a profound impact upon our judgements, experiences, and behaviour (Corcoran et al., 2011).

Social comparisons are often operationalised as an habitual trait in the extant literature (Luong et al., 2019), though empirical research with young people has found social comparison behaviours to negatively associate with self-concept clarity (Saadat et al., 2017) and positively relate with intolerance of uncertainty (Butzer & Kuiper, 2006). Facebook-based studies have found similar results in online contexts, with emerging adults scoring high in self-uncertainty reporting the highest scores in Facebook comparison behaviour (Lee, 2014). These results suggest that young people who lack a clear sense of self seek external sources to help make self-definitions, which may support them to better understand who they are and how they fit into society. Thus, this study recognises social comparison processes as goal-orientated behaviour which adolescents may utilise to inform identity development.

Whilst the social comparison literature has historically concerned behaviour in offline contexts, contemporary SNSs - organised around streams of user-generated content - have presented their users with almost limitless opportunities to compare themselves to others. Amongst the most popular SNSs with British adolescents is Instagram, with recent OFCOM (2018a, 2018b) data suggesting that 65% of those aged 12-15 and 64% of those aged 16-24 have an account on the image-sharing platform. Young people typically use Instagram for creative self-expression and peer surveillance (Sheldon & Bryant, 2016), and given that viewing content shared by others is often cited as a key motivation for using Instagram (Huang & Su, 2018; Lee et al., 2015), social comparison behaviour is likely to be commonplace. Furthermore, given its image-centric nature, its facilitation of nonreciprocal connections, and its particularly biased and aesthetic visual culture, relative to alternative SNSs, Instagram represents a unique context for social comparison behaviour. With that being said, Festinger (1954) suggested that social comparison behaviours come in two primary forms - comparisons of ability and comparisons of opinion, and it is hypothesised that when conducted on Instagram, such comparisons may have opposing implications for adolescent identity development.

Social Comparisons of Ability

Social comparisons of ability entail comparisons of achievement and performance (Yang, Holden, & Carter, 2018), and occur when individuals seek to determine how well they are doing relative to others (Festinger, 1954); they are, therefore, highly judgemental and competitive (Park & Baek, 2018). Much of the ability comparison literature focuses on the direction of ability comparisons, and such processes are typically framed in terms of upward and downward comparisons. Individuals conduct upward comparisons with those they deem superior on a given dimension, with the superior other acting as a role model to demonstrate to the comparer how to improve the self. In contrast, downward comparisons occur when individuals compare themselves with those they deem inferior on a given dimension, and such comparisons are typically utilised in an attempt to self-enhance and maintain a positive self-image.

Researchers have investigated a range of ability-based comparisons on SNSs (e.g., de Vries & Kühne, 2015; Vogel et al., 2014), and since Instagram users tend to selectively self-present their ‘ideal self’ on the platform - thus appearing happy, interesting, and/or successful (Yau & Reich, 2019), upward social comparisons of ability - where individuals consider others to be better off than themselves - are understood to be commonplace. Significantly, although upward comparisons can engender positive motivational outcomes, comparisons with superior others can also engender feelings of inadequacy and dissatisfaction (Buunk et al., 1990). It is cause for concern, then, that research has largely found upward comparisons on SNSs to be associated with negative psycho-emotional consequences, including feelings of jealously, envy, and anxiety (Fox & Moreland, 2015; Lim & Yang, 2015), increased depressive symptoms (Feinstein et al., 2013), low self-esteem (Vogel et al., 2014), high negative affect (Vogel et al., 2015), and low positive affect (de Vries et al., 2018). An explicit example of this ‘compare and despair’ phenomenon in an identity-relevant domain was highlighted by Morry et al. (2018), who in their study regarding romantic relationship social comparisons on Facebook found that negative emotions following upward comparisons predicted lower life satisfaction, lower relationship satisfaction, lower relationship commitment, and lower feelings of interpersonal closeness with their partner. Negative self-evaluations in identity-relevant domains not only have a detrimental effect upon one’s emotions, often leading to maladaptive behaviour, but can also disturb identity exploration (Harter, 2012; Tsang et al., 2012). Therefore, by focusing upon the superior achievements and/or abilities of others on Instagram, adolescents may be discouraged when they reflect back upon their own individual progress, thus inhibiting identity exploration and reducing commitment.

There is, though limited, some empirical evidence to support such a conclusion. For example, Yang, Holden, and Carter (2018) found that SNS social comparisons of ability were positively associated with the diffuse-avoidant identity style, which in turn predicted lower identity clarity. Young people adopting the diffuse-avoidant style (Berzonsky, 1990, 2011) actively avoid processing identity-related information, and empirical research has found this style to negatively associate with commitment and in-depth exploration, and positively associate with reconsideration of commitment (e.g., Crocetti et al., 2009; Crocetti et al., 2013; Zimmermann et al., 2012). This identity style therefore reflects a condition of identity uncertainty and avoidance, and Yang, Holden, and Carter (2018) hypothesised that the emerging adults in their study may have adopted this approach to their identity as a coping mechanism to help them escape from the self-threatening SNS content to which they were comparing their abilities. Similarly, in a later study, Yang, Holden, Carter, and Webb (2018, p. 98) found that SNS social comparisons of ability were positively associated with rumination - which later predicted identity distress, and suggested that participants may have “adopt[ed] rumination as a strategy to regulate unpleasant emotions derived from online social comparison[s]”.

Whilst the aforementioned studies were conducted with participatory samples consisting of emerging adults rather than adolescents, their findings do indeed suggest that SNS social comparisons of ability may inhibit identity development through reducing self-certainty, repressing in-depth exploration, and increasing self-doubt. Furthermore, whilst no studies have determined whether these results would replicate with Instagram users, given the positively biased - and perhaps unrealistic - content shared on the platform, feelings of inadequacy following ability comparisons may be particularly commonplace. Indeed, a UK-wide study found that when compared to Youtube, Twitter, Facebook, and Snapchat, Instagram was ranked worst for youth mental health and overall wellbeing (Royal Society for Public Health, 2017a); the researchers working on the study suggested that the image-focused, highly-curated nature of Instagram content drove feelings of inadequacy and anxiety in young people (Royal Society for Public Health, 2017b). Thus, it is possible that the inhibitory effects of such comparisons are not only replicated on Instagram, but in fact exacerbated by experiences on the platform. Therefore, it is predicted that:

H1a: Social comparisons of ability on Instagram will be negatively associated with commitment.

H1b: Social comparisons of ability on Instagram will be negatively associated with in-depth exploration.

H1c: Social comparisons of ability on Instagram will be positively associated with reconsideration of commitment.

Social Comparison of Opinion

Social comparisons of opinion involve comparing one’s beliefs and preferences to those of others (Suls et al., 2000), and stem from the desire to learn about social norms, to clarify or challenge one’s value system, and to regulate one’s behaviour. Here, individuals draw upon the opinions of others to evaluate whether their own beliefs and preferences are accurate or socially acceptable, and as such, others are viewed not as competitors, but as role models, consultants, and informants (Park & Baek, 2018).

In contrast to the rich literature on SNS social comparisons of ability, there are only a handful of published studies regarding SNS social comparisons of opinion, all of which drew upon non-adolescent samples. Amongst these studies, Brandenberg et al. (2019) found that opinion comparisons on Facebook and Xing were not related to self-esteem or depressive symptoms, whilst Park and Baek (2018) reported that opinion comparisons on Facebook positively associated with upward assimilative emotions (optimism and inspiration) and negatively associated with upward contrastive emotions (envy and depression). These findings provide initial evidence to suggest that opinion comparisons on Instagram may not have the detrimental psycho-emotional consequences associated with ability comparisons on the platform. Moreover, in terms of identity and ‘fitting in’, Yang and Robinson (2018) reported a positive indirect association between social comparisons of opinion and college adjustment via frequent Instagram interaction with on-campus friends; Yang, Holden, Carter, and Webb (2018) found that SNS social comparisons of opinion were positively associated with reflection; and Yang, Holden, and Carter (2018) identified that SNS social comparisons of opinion were associated with the informational identity style. This identity style is characterised by active exploration, and is positively associated with commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment (e.g., Crocetti et al., 2009; Crocetti et al., 2013; Zimmermann et al., 2012). The findings of these studies therefore suggest that in contrast to ability comparisons, opinion comparisons on Instagram may positively affect psychological well-being, evoke identity exploration/reconsideration, and support commitment solidification. Based on this, it is assumed that:

h3a: Social comparisons of opinion on Instagram will be positively associated with commitment.

h3b: Social comparisons of opinion on Instagram will be positively associated with in-depth exploration.

h3c: Social comparisons of opinion on Instagram will be positively associated with reconsideration of commitment.

Methods

Participants

Adolescents attending a large mixed-ability Catholic secondary school and sixth form college in central England were invited to complete a paper survey regarding their use of Instagram. Informed consent was obtained by the head teacher loco parentis, student participation was voluntary, and the questionnaire was completed during morning form time so as not to disrupt lesson timetabling. 266 surveys were returned, though there was significant missing data (33.83% of cases, 16.61% of values). An inspection of the data found that missing data was non-ignorable and often appeared monotone in nature, whereby many participants did not complete the questionnaire. Respondents who failed to report a score regarding Instagram-based social comparison behaviour and those with missing data regarding dependent variables (i.e., commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment) (Hair et al., 2014) were excluded from the analysis. Following this initial data cleansing, 192 participants remained. Only 15 (7.81%) of the remaining cases reported missing data, and Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test indicated that missing data was MCAR (χ2(34) = 32.15, p = .56). Given the small proportion of missing data, to ensure unbiased estimates in subsequent analyses, listwise deletion was utilised. Following listwise deletion, 177 valid responses were identified. Respondents were aged between 13-18 years (Mage = 15.45, SD = 1.67), and predominantly identified as White British (79.5%) and female (54.8%).

Measures

Social Comparison Behaviour

To determine Instagram social comparison behaviour, eight items from the Social Media Social Comparison Scale (Yang, Holden, & Carter, 2018) were modified; for each item, the phrase "social media" was replaced with "Instagram". Adolescents were asked to consider how often they compared their abilities and opinions to others on Instagram, and to indicate how well each item applied to them on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very well). Results of a confirmatory factor analysis confirmed a two-factor structure, thus differentiating between ability and opinion comparisons on Instagram (χ2(19) = 20.82, p = .35, CFI =.997, TLI = .996, RMSEA = .02). An example item on the four-item ability comparison subscale was “When using Instagram, I compare how I do things with how others do things”, whilst an example item on the four-item opinion comparison subscale was “When using Instagram, I try to find out what others think about something that I want to learn more about”. Cronbach’s αs were .81 for social comparison of ability and .81 for social comparison of opinion.

Identity Dimensions

To assess participants' identity dimensions, the Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS; Crocetti, Rubini, & Meeus, 2008) was utilised. U-MICS can be employed to investigate identity in terms of a specific ideological or relational domain, or to discern global identity through combining at least one ideological and one relational domain (Crocetti & Meeus, 2014). Marcia (2001) noted that the domains researchers elect to measure are not particularly important, providing they are important; that is, they must be in a life area meaningful to respondents. As with previous studies which used U-MICS to determine adolescent identity (e.g., Crocetti, Rubini, & Meeus, 2008; Dimitrova et al., 2016; Morsunbul et al., 2014), participants’ opinions regarding their education (ideological) and friendships (relational) were measured. U-MICS consists of 13 five-point Likert scale questions (1 = completely untrue, 5 = completely true) - five concerning commitment (“My education gives me security in life”), five assessing in-depth exploration (“I try to find out a lot about my education”), and three measuring reconsideration of commitment (“I often think that it would be better to try to find a different education”). Since measures for two identity domains were utilised, there was a total of 26 items. Significant correlations were found across the education and friendship domains in terms of commitment (r = .39, p < .001), in-depth exploration (r = .38, p < .001), and reconsideration of commitment (r = .16, p = .03). These results are consistent with previous research which has considered the associations between identity domains, with Karaś and Cieciuch (2015) reporting that across eight domains (character, past experiences, family, friends, worldview, interests, aims, and occupation), the intercorrelations between the identity dimensions ranged from r = .32 - .67 for commitment, r = .16 - .51 for in-depth exploration, and r = .08 - .67 for reconsideration of commitment. U-MICS has previously been found to have high cross-cultural, factorial, and convergent validity (e.g., Crocetti et al., 2010; Zimmermann et al., 2012), and in this study, the composite variables reflecting global identity scored high in internal consistency; Cronbach’s α were .88 for commitment, .84 for in-depth exploration, and .77 for reconsideration of commitment.

Results

Exploratory Analysis

Adolescents reported similar levels of ability (M = 2.21, SD = 0.88) and opinion comparison (M = 2.18, SD = 0.88) behaviour on Instagram, and scored higher in commitment (M = 3.59, SD = 0.64) and in-depth exploration (M = 3.29, SD = 0.67) than reconsideration of commitment (M = 2.09, SD = 0.66). Interestingly, a Pearson’s correlation found that ability comparisons were positively correlated with commitment (r = .20, p = .01) and in-depth exploration (r = .36, p < .001), whilst opinion comparisons were positively related with in-depth exploration (r = .34, p < .001) and reconsideration of commitment (r = .26, p = < .001). In terms of demographic differences, age was associated with commitment (r = .15, p = .046) and in-depth exploration (r = .18, p = .02), whilst an independent samples t-test found that female adolescents scored significantly higher than males in Instagram social comparisons of ability (t(175) = 3.05, p = .003), commitment (t(175) = 2.59, p = .01), and in-depth exploration (t(175) = 3.69, p < .001). Given the significant demographic differences found in this exploratory analysis, age and gender were included as covariates in subsequent analyses, as were their respective interactions with Instagram social comparison behaviour. Cronbach’s α, descriptive statistics, and correlation coefficients of the major variables can be found below in Table 1.

Table 1. Mean Scores of Major Variables, Cronbach’s Alpha, and Pearson’s Correlation.

|

|

α |

M |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1. SC Ability |

.81 |

2.21 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

2. SC Opinion |

.81 |

2.18 |

.56*** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

3. Commitment |

.88 |

3.59 |

.20** |

.11 |

1 |

|

|

|

4. Exploration |

.84 |

3.29 |

.36*** |

.34*** |

.58*** |

1 |

|

|

5. Reconsideration |

.77 |

2.09 |

.11 |

.26*** |

-.25*** |

-.02 |

1 |

|

6. Age |

- |

15.45 |

-.06 |

.08 |

.15* |

.18* |

-.09 |

|

Note. Based on N = 177 participants following listwise deletion. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. SC = Social Comparison. |

|||||||

Hypotheses Testing

To control for the moderately strong correlations between Instagram social comparisons of ability and opinion, both social comparison behaviours were entered as predictors in a regression analysis. Furthermore, to control for correlations between the identity dimensions, a multivariate multiple regression was conducted. Thus, age, gender, ability comparisons, ability comparisons x age, ability comparisons x gender, opinion comparisons, opinion comparisons x age, and opinion comparisons x gender were independent variables, whilst commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment were dependant variables. Based upon Wilk’s Lambda (Wilk’s λ = .64), the multivariate test was significant (F(24, 482) = 3.36, p < .001, ηp2 = .14). Instagram comparisons of opinion (λ = .91, F(3, 166) = 5.21, p = .002, ηp2 = .09), gender (λ = .95, F(3, 166) = 2.76, p = .04, ηp2 = .05), and age (λ = .95, F(3, 166) = 2.77, p = .04, ηp2 = .05) were significant multivariate predictors, whilst Instagram comparisons of ability (λ = .96, F(3, 166) = 2.55, p = .06, ηp2 = .04) and Instagram comparisons of ability x gender (λ = .96, F(3, 166) = 2.16, p = .09, ηp2 = .04) were both approaching significance at the p < .05 level.

Given the significant multivariate results, the univariate equations were inspected (Table 2). Significant univariate regression equations predicting commitment (R2 = .09, F(8, 168) = 2.15, p = .03), in-depth exploration (R2 = .23, F(8, 168) = 6.37, p < .001) and reconsideration of commitment (R2 = .15, F(8, 168) = 3.57, p <.001) were found. Instagram social comparisons of ability were positively associated with commitment (β = .18, t = 2.04, p = .04) and in-depth exploration (β = .23, t = 2.70, p = .01), and negatively - though not significantly - related with reconsideration of commitment (β = - 05, t = -.52, p = .60); H1a, H1b, and H1c were therefore rejected. Interestingly, the interaction between Instagram social comparisons of ability and gender significantly predicted reconsideration of commitment (β = -.21, t = -2.38, p = .02). A simple slopes analysis using the PROCESS (Hayes, 2018) macro in SPSS was subsequently conducted to probe the statistically significant moderator effects. The analysis revealed that social comparisons of ability on Instagram were negatively associated with reconsideration of commitment for males (β = -.28, t = -2.02, p = .045), and positively - though not significantly - related with reconsideration of commitment for females (β = .14, t = 1.29, p = .20).

Table 2. Standardised Betas for Association Between Instagram Social Comparison Behaviour and Identity Dimensions.

|

|

Commitment |

Exploration |

Reconsideration |

|

Age |

.16* (.07) |

.19** (.07) |

-.10 (.07) |

|

Gender |

-.14 (.07) |

-.19** (.07) |

.07 (.07) |

|

SC Ability |

.18* (.09) |

.23** (.09) |

-.05 (.09) |

|

SC Ability x Age |

.03 (.10) |

-.05 (.09) |

-.10 (.10) |

|

SC Ability x Gender |

-.02 (.09) |

.004 (.09) |

-.21* (.09) |

|

SC Opinion |

-.02 (.09) |

.17* (.09) |

.27** (.09) |

|

SC Opinion x Age |

.03 (.10) |

-.02 (.09) |

-.09 (.09) |

|

SC Opinion x Gender |

.01 (.10) |

-.06 (.08) |

.04 (.09) |

|

R2 |

.09 |

.23 |

.15 |

|

F |

2.15 (8, 168) |

6.37 (8, 168) |

3.57 (8, 168) |

|

p |

.03 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

|

Note. Based on N = 177 participants following listwise deletion. Standard error in parentheses. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Female = 0, Male = 1. SC = Social Comparison. |

|||

In terms of comparisons of opinion, Instagram social comparisons of opinion were positively associated with in-depth exploration (β = .17, t = 2.01, p = .046) and reconsideration of commitment (β = .27, t = 3.16, p = .002); h3b and h3c were therefore accepted. The relationship between Instagram social comparisons of opinion and commitment was not significant (β = -.02, t = -.26, p = .80), and thus, h3a was rejected. None of the interactions between Instagram social comparisons of opinion and age or gender were nearing significance.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study sought to examine how social comparisons on Instagram associate with adolescent identity development, and guided by the results of previous research (Yang, Holden, & Carter, 2018; Yang, Holden, Carter, & Webb, 2018), it was predicted that ability-based and opinion-based social comparisons would have differing implications for adolescent identity. In terms of social comparisons of ability on Instagram, it was hypothesised that they would associate with reduced commitment, inhibited in-depth exploration, and increased reconsideration of commitment. However, in contrast to these hypotheses, Instagram social comparisons of ability were found to positively associate with commitment and in-depth exploration, whilst for adolescent males, they were also negatively associated with reconsideration of commitment. These findings suggest that rather than reducing self-certainty, suppressing exploration, and increasing self-doubt, such comparisons may compel adolescents to reflect upon their abilities in identity-relevant domains, thus evoking further in-depth exploration, and supporting young people in solidifying their identity commitments.

Whilst these findings suggest that social comparisons of ability on Instagram may help to support adolescents to explore their identity, the results of previous studies had implied that such comparisons may have detrimental implications for identity development during emerging adulthood (Yang, Holden, & Carter, 2018; Yang, Holden, Carter, & Webb, 2018). Although issues relating to identity tend to emerge during the teenage years, many of the enduring decisions made in identity-related domains - such as romantic relationships, career choices, and worldviews - are made during emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000). As such, exploratory behaviour during adolescence is typically considered more transient and tentative (Arnett, 2015), and adolescents are less likely to strongly identify with their commitments (Luyckx et al., 2013). Given the less ‘serious’ and ‘focused’ nature of identity exploration during adolescence, it is possible that some of the potentially detrimental implications of upward comparisons on SNSs - such as self-doubt and rumination - are somewhat attenuated for adolescents, and are experienced more so by individuals during emerging adulthood. Indeed, although identity distress (uncertainty and discomfort) and identity impact (overwhelming emotions which cause disfunction to everyday life) are present during adolescence, they tend to reach their highest levels during emerging adulthood (Palmeroni et al., 2019).

Such reasoning is also supported by the gender differences that were found regarding the relationship between social comparisons of ability on Instagram and reconsideration of commitment. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Klimstra et al., 2010), adolescent males reported less mature identity profiles, scoring lower in commitment and in-depth exploration. Importantly, then, for male participants, social comparisons of ability were associated with reduced reconsideration of commitment, thus suggesting that such behaviour may help to alleviate uncertainty regarding abilities in identity-relevant domains. In contrast, whilst the results were not significant at the p < .05 level for adolescent females (p = .20) - who reported more mature identity profiles, the direction of the relationship between comparisons of ability on Instagram and maladaptive identity outcomes was consistent with that found in research with emerging adults (Yang, Holden, & Carter, 2018; Yang, Holden, Carter, & Webb, 2018). Thus, it appears that the less invested young people are in their identity, the less at-risk they are of experiencing negative psycho-emotional outcomes following comparisons with others who appear superior in identity-related domains of interest. Indeed, in instances where young people have a stronger sense of who they are, what they deem valuable or important, and what society expects of them, their ability to identify significant inadequacies following upward comparisons on SNSs is likely to be heightened.

In addition to possible developmental explanations for these differences, the targets of ability comparisons on Instagram should also be considered. Most comparisons on Instagram tend to be upward in nature, and according to social comparison theory, the perceived similarity between comparer and comparison target moderates the psycho-emotional implications of such comparisons (Smith, 2000). Indeed, in their recent study with adolescent Instagram users, Noon and Meier (2019) found that network homophily (i.e., the extent to which individuals deem their networks to be similar to them) positively moderated the relationship between ability comparisons and benign envy, and negatively moderated the relationship between ability comparisons and malicious envy. Thus, as comparisons with individuals deemed far superior are more likely to elicit negative outcomes (Smith, 2000), it may be that adolescent males are less likely to engage with content from unachievable false role models on Instagram. Furthermore, previous research has also found that tie strength (Lin & Utz, 2015; Liu et al., 2016) and amount of strangers followed (Chou & Edge, 2012; de Vries et al., 2018) can also influence the emotional outcomes of SNS social comparisons of ability. Future research should therefore consider who adolescents are comparing themselves to on SNSs, and the extent to which network composition influences identity development.

In terms of Instagram comparisons of opinion, it was hypothesised that such behaviour would be associated with increased commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment. Though social comparisons of opinion on Instagram did not significantly predict commitment, they were positively associated with both in-depth exploration and reconsideration of commitment. Such results are therefore largely consistent with research with emerging adults, which had previously found that SNS social comparisons of opinion predict identity styles characterised by active identity exploration (Yang, Holden, & Carter, 2018; Yang, Holden, Carter, & Webb, 2018). It appears, then, that opinion-based comparisons on Instagram provoke young people to reflect upon their beliefs and values, thus eliciting identity exploration. Significantly, although a previous small-scale study had reported that opinion comparisons on SNSs were positively related to in-depth exploration but not reconsideration of commitment (Noon, 2018), it is important to note that the findings of this investigation suggest that Instagram comparisons of opinion can elicit both in-depth exploration and reconsideration of commitment.

Limitations

One limitation of this study was sample size, and post-hoc power analyses using SPSS 24 identified that several multivariate predictors that were significant or nearing significance at the p < .05 level reported low observed power (Age = .66; Gender = .66; Instagram social comparisons of ability = .62; Instagram social comparisons of ability x Gender = .54). Indeed, the final sample (N = 177) was not particularly large in this study, nor has it been in previous investigations in this area (e.g., Yang, Holden, & Carter, 2018; Yang, Holden, Carter, & Webb, 2018). In future studies, it would be advantageous for researchers to attain larger samples and revisit the multivariate results. A methodological limitation was that global identity was determined using only two identity domains; this was done, in part, to limit the length of the survey in an attempt to increase response rate. Whilst it is possible to determine a global identity score through combining one ideological and one relational domain using U-MICS (Crocetti & Meeus, 2014), drawing upon different and/or additional domains may have provided a better understanding of participants’ global identity. Indeed, although the domains of education and friendship are amongst the most salient in the lives of adolescents and are used widely across the academic literature, it may be that alternative domains - such as political persuasion and romantic relationship status - are more relevant to Instagram comparisons. Furthermore, researchers should also examine specific identity domains independent of one another to help learn more about which domains adolescents are exploring through SNS social comparisons.

Conclusion

This study sought to consider how social comparison behaviour on Instagram associates with adolescent identity development. Whilst the long-term valence of SNSs social comparisons cannot be determined by this cross-sectional study, findings provide initial evidence to suggest that Instagram-based social comparisons of ability and opinion are largely supportive of adolescent identity development. Furthermore, male adolescents appeared less susceptible to experiencing the negative consequences of ability comparisons on Instagram, and when considered alongside previous studies (Yang, Holden, & Carter, 2018; Yang, Holden, Carter, & Webb, 2018), findings suggest that ability comparisons on SNSs may have more maladaptive identity implications during emerging adulthood. Further research is now required to determine whether these differences between adolescents and emerging adults, and indeed those between male and female adolescents, are determined by developmental factors, network composition factors, or both. Further research is also required to examine how social comparisons on alternative SNSs associate with adolescent identity development. Importantly, image-based platforms such as Instagram provide considerably different comparison opportunities than more text-based platforms such as Twitter, and it is possible that comparisons on opposing platforms differ in how they support, or impede, adolescents’ search for a coherent and synthesised sense of self. Nevertheless, this investigation is the first of its kind to have considered the relationship between Instagram social comparisons and adolescent identity development, and can act as a precedent for future scholarship in this area.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2020 Edward John Noon