Couple boundaries for social networking in middle adulthood: Associations of trust and satisfaction

Aaron M. Norton1, Joyce Baptist22 School of Family Studies and Human Services, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA

Abstract

Keywords: boundaries; couple relationships; marriage; social networking; trust

Introduction

In the beginning, researchers theorized that computer-mediated communication would be incapable of replicating face-to-face communication because it lacked the visual and verbal social cues of offline relationships (Riva, 2002). The lack of visual and verbal social cues, however, has not deterred the formation of intimate, romantic relationships that can and often do continue successfully offline with little to no difficulty (Riva, 2002; Whitty, 2008). The abundance and ease of online relationship formation has more recently led to investigating how the Internet may harm couple relationships through behaviors such as intrusion, addiction, and Internet infidelity (e.g., Elphinston & Noller, 2011; Hertlein & Piercy, 2006; Kerkhof, Finkenauer, & Muusses, 2011).

This new body of research demonstrates that internet use is associated with violations of fidelity and decreased relationship satisfaction. Excessive use and attachment to social networking sites, such as Facebook, has been shown to be associated with increased relationship dissatisfaction and jealousy (Elphinston & Noller, 2011) while increased partner-monitoring of such activities is associated with decreased relationship trust (Darvell, Walsh, & White, 2011). The Internet can also violate relationships through online affairs, which have been shown to be remarkably similar to offline affairs in the way that it impacts relationships. In a survey of 91 women and three men whose partners engaged in online affairs and compulsive sexual behavior, Schneider (2003) found that participants reported decreased relationship trust and satisfaction through feelings of betrayal, rejection, abandonment, loneliness, jealousy, humiliation, and anger. Overall, this emerging body of research assesses how Internet use is linked with decreased relationship satisfaction and trust.

What we do not know is how couples safeguard their relationship from Internet-related issues. We begin by exploring how increased relationship satisfaction and trust may be linked with reversing the negative impact of the Internet by protecting relationships via boundary setting. Relationship satisfaction that is strongly associated with positive marital behaviors, such as being more open with sharing information and tasks (Stafford & Canary, 1991), may contribute to clear, open boundaries. Clear boundaries that promote sharing, may help prevent opportunities for online infidelity.

In a similar vein, trust, that is said to develop over time (Lewicki & Bunker, 1995), may manifest in behaviors that can strengthen relationships. Such behaviors allow relationships to progress from behavioral-focused trust to trust based on shared core values and identity. In the final stage of the three stages of trust that we expect in long-term married relationships, couples are expected to be openly sharing an identity, time in the same place, and goals and core values (Lewicki & Bunker, 1995). This type of trust could mean not needing to have rules or boundaries but instead freely share all online communication that in turn can contribute to further trust and satisfaction. At this stage actions that challenge shared core values create a sense of moral violation that can be difficult to repair. Using a sample of long-term married couples that have established trust (Lewicki & Bunker, 1995), we examine the following hypotheses:

H1: Relationship satisfaction will be related to boundary setting.

H2: Relationship trust will be related to boundary setting.

In the interest of understanding gender differences, we examined if the pathways from relationship satisfaction and trust to boundary setting differed between men and women.

Social Networking in Middle Adulthood

Age is strongly correlated with internet use, where younger individuals tend to report greater Internet and social media use. As of May 2013, 85% of American adults 18 and older use the Internet, with 97% of 18 to 29 year olds, 93% of 30 to 39 year olds, 88% of 50 to 64 year olds, and 57% of Americans 65 years old and older reported regular internet use (Fox & Rainie, 2014; Zickuhr, 2013). For adults who are online, 73% use a social networking site, with 87% social media usage for 18 to 29 year olds, 68% for 30 to 49 year olds, 49% of 50 to 64 year olds, and 29% of 65 years and older (Duggan & Smith, 2013; Zickuhr & Smith, 2012). Moreover, adoption of social networking sites has increased exponentially over the past decade, where 8% of all adults were social networking users in 2005, 60% were in 2010, and 72% in 2013. For adults aged 50 to 64 years old, 7% used social networking sites in 2005, 49% in 2012, and 60% in 2013 (Brenner & Smith, 2013). Consequently, middle-age adults who have been in long-term committed relationships have had to work out its role and use within their already existing relationship. And the number of middle-age adults who are doing this is increasing dramatically each year. However, most studies so far only address social media use with adolescent and emerging adult samples. Very little is understood about how older, married couples are managing social networking in long-term committed relationships.

Relational Boundaries for Social Networking

When couples form committed relationships, one of the primary challenges is the maintenance of a unique couple subsystem separate and distinct from all other systems. As couples navigate the marital relationship, boundaries are formed to address how outside systems -- friends, the in-laws -- interact with the couple subsystem. The boundaries, a set of rules and expectations that define who or what participates in the subsystem and how that interaction occurs, function to maintain freedom from interference by other subsystems (Minuchin, 1974). For example, individuals may limit the types of interactions with opposite-sex friends in order to maintain the fidelity of their relationship. Through the maintenance of this rule, a boundary for fidelity is maintained and the relationship is further safeguarded from affairs.

Mutual support and loyalty are common expectations in couple relationships that in turn create boundaries to protect the structure and fidelity of relationships (Thieme, 1997), the breakdown of which is associated with relational affairs (Butler, Harper, & Seedall, 2009; Butler, Seedall, & Harper, 2008; Duba, Kindsvatter, & Lara, 2008; Fife, Weeks, & Gambescia, 2008; Gordon, Baucom, & Snyder 2004). Stafford and Canary (1991) identified various relationship maintenance strategies that show each partner’s responsibility to the other, such as openness, sharing friendship networks, displays of positivity, assuring the future and commitment of the relationship, and completing tasks. As a result, some couples may establish an expectation that they openly disclose all financial information to each other, thereby increasing the desire for the relationship maintenance behavior of openness. This behavior may then create a boundary to assure that the couple system is able to jointly mitigate any interference that may come from financial suprasystems and thereby reinforce the distinct structure of the marital relationship.

While there appears to be some set rules and boundaries that apply to offline relationships, it is unclear how or if these rules apply to Internet behaviors. Some research has been conducted examining rules for cell phone use. For instance, several researchers have found that couples have rules about how frequently contact with others outside the relationship is appropriate, how conflict is managed, whether is it appropriate to access and check partner’s text messages, call logs, and social media accounts, whether it is appropriate to flirt with others online, and how access to each partner’s social media is managed (Duran, Kelly, & Rotaru, 2011; Helsper & Whitty, 2010; Miller-Ott, Kelly, & Duran, 2012).

Preliminary research on the nature of online relationships indicates that they are formed and develop differently than offline relationships. Online cross-sex relationships have been found to develop more easily than offline relationships and the differences between offline and online friendships diminish across time (Chan & Cheng 2004). Applying this outcome to intimate relationships, these findings indicate that a partner may more easily develop a cross-sex friendship online and that the depth and commitment of that relationship will more closely resemble that of its offline counterpart as the duration of the relationship increases. Consequently, a partner may develop an affair more easily online than offline (Hertlein & Blumer, 2013). One reason that this may occur is that the traditional relationship rules or expectancies that caution couples from developing an intimate relationship with an offline individual may not apply to online relationships. To begin, we need to first understand what kind of unique rules and expectations couples have for social networking. Based on the literature, five questions were asked regarding Internet-related information -- sharing of passwords, identity of friends and social networking sites, and restrictions of friends and behaviors. Confirmatory factor analysis was utilized to test for the fit of latent variables for Internet boundaries.

Relationship Satisfaction as a Key Factor in Boundary Setting

While decreased relationship satisfaction is associated with negative impacts of the Internet such as online infidelity (Darvell et al., 2011), increased relationship satisfaction is associated with positive marital interactions (Karney & Bradbury, 1997) and cooperative behavior (Tallman & Hsiao, 2004). More specifically, relationship satisfaction is highly associated with maintenance behaviors -- openness, positivity, shared networks and tasks, and assurance (Stafford & Canary, 1991). Essentially, the happier individuals are in their marriage, the more motivated they become to maintain that satisfaction through maintenance behaviors; when couples are highly satisfied, they become more likely to share friends and be open with each other. The same may be true of social networking boundaries, where the more satisfied couples are the more likely they may be to have clear, open boundaries.

It is also important to consider how relationship satisfaction may impact marriage across time. The research on the long-term trajectory of marital happiness shows that relationship satisfaction is stable over time for many couples. Anderson, Van Ryzin and Doherty (2010) analyzed the longitudinal course of marital happiness using growth curve modeling for 706 individuals that spanned 50 years of marriage. The authors found that the traditional U-shaped curve of marital happiness did not hold true, but that there were five trajectories of marital happiness, four of which represent stable trajectories and one declining trajectory. We hypotheses that relationship satisfaction, an enduring factor in marriages, will continue to impact marital behavior, such as boundary setting, in long-term intimate relationships.

The Trajectory of Trust in Relationships

Trust is a dynamic, transformative component of romantic relationships that changes and grows with the relationship (Holmes, 1991; Lewicki & Bunker, 1995; Zak, Gold, Ryckman, & Lenney, 1998). Trust is a key factor in relationship quality (Fletcher, Simpson, & Thomas, 2000) and is highly correlated with relationship satisfaction and stability (Campbell, Simpson, Boldry, & Rubin, 2010). Few relationships endure where trust has not been established, maintained, and nurtured. As Boon & Holmes (1991) stated, “The weaving together of two lives is a complex process, fraught with the potential for conflict of interest and bounded on all sides by people’s vulnerabilities and fears. The capacity to trust is an essential ingredient in fulfilling the promise of such relationships” (p. 201). Trust is one of the most powerful relationship factors that is associated with many behaviors within romantic relationships (e.g. Fletcher et al., 2000; Holmes, 1991; Lewicki & Bunker, 1995; Klacsmann, 2007).

Lewicki and Bunker (1995) theorize that trust may change across time in romantic relationships. Accordingly, trust progresses across three stages of development: calculus-based, knowledge-based trust, and identification-based trust. Calculus-based trust is based on a social-exchange perspective where trust is “an ongoing, market-oriented, economic calculation whose value is derived by comparing the outcomes resulting from creating and sustaining the relationship to the costs of maintaining or severing it” (Lewicki & Bunker, 1995, p. 145). At this first stage, trust is driven by the benefits and costs of cheating, breaking, or staying in the relationship. As trust continues to develop, it becomes predicated upon deeper interpersonal familiarity that emerges with repeated interaction. Knowledge-based trust relies on information gathered about the other person in a way allows for predicting the other’s behavior. Individuals learn how and when a party will be trustworthy or untrustworthy. As long as the other person remains predictable, then this form of trust is secured and grown. Identification-based trust is achieved when the other’s desires and intentions are fully internalized. At this stage, individuals share strong emotional bonds and similar values that form the environment for self-disclosure.

By the time individuals reach the final stage of trust development each side thinks, feels, and acts like the other where they each endorse the others’ wants, goals, and desires. Lewicki and Bunker (1995) described three elements necessary in this stage: sharing a name or identity (such as a surname), colocation (spending time in the same place), and the sharing of goals and values. Through this process, each internalizes the other’s values, goals, wants, and desires. They act for the other not only because they believe that is what the other wants, but because they want it as well.

Trust is a strong relationship process that has been shown to directly impact relationship expectations, quality, and views of partners’ motivations (Zak et al., 1998). As trust develops across time, expectations for one’s partner are formed based on traits, experience, and self-perception. It is possible that increased trust displaces the need for relationship rules and setting of boundaries or that rules and boundaries are a manifestation of distrust. As trust develops and grows, the utility of such rules and boundaries may become obsolete in the marriage. However, the opposite may be true as well. Rules and boundaries may serve to protect and ensure continued trust and fidelity in the relationship. Given the importance of trust in maintaining relationships, we hypotheses that trust will be related to boundary setting in relationships.

Method

Participants and Data Collection

Participants consisted of 255 parents recruited from 235 students across three undergraduate courses in a family studies program of a large Midwestern university. The study was approved by the university’s Institution Research Board. Potential participants were invited through email via their children (i.e., university students) to voluntarily complete an online survey. The researchers did not have direct contact with the participants, but rather elicited students to forward requests for research participation to their parents. The parents’ data was not matched to their student children and therefore total response rates from the recruitment sample were not able to be calculated. Fifty participants were eliminated from the final analysis. These were participants who did not identify their relationship status as “currently married” (N = 37), provided duplicate responses (N = 1), or completed only the demographic questions were omitted (N = 12). Chi-square and ANOVA tests indicated no significant differences among demographic variables between the participants who were dropped and those included in the final analysis.

The data was also scanned to determine whether participants (parents of students) were married couples. A dyadic analysis was not appropriate for the sample because married spouses could not be matched with the available data. Instead, male (N = 98) and female (N = 107) groups were created to conduct group comparisons and test relationships among variables within each group, separately by sex.

The final analysis included 205 married individuals, with 98 male and 107 female participants. All missing data was handled using maximum likelihood method. The mean age of participants was 52 years (SD = 5.51) for men and 51 years (SD = 5.54) for women and the mean marital length was 28 years for both men (SD = 7.20) and women (SD = 6.93; see Table 1). Of this, 196 participants were White (95.6%), 2 were Latino (1.0%), 3 were Black (1.5%), and 1 was Asian (0.5%). Furthermore, 74.1% participants identified the best description of their daily activities and responsibilities as “full-time, working”, 10.7% as “part-time, working”, 2.0% as “unemployed or laid off”, 8.3% as “keeping house or raising children full-time”, and 4.9% as “retired.” For educational level, 25.9% held a high school diploma or GED, 10.7% an associate degree, 42.4% a bachelor’s degree, 15.1% a master’s degree, 0.5% a doctoral, and 1.5% with other professional training or credentials.

Measures

Five Internet boundaries were identified as dependent variables in the current study. Participants were asked to respond along a 7-point Likert-type scale, where 1 indicated “completely agree” and 7 “completely disagree”, with the following statements: “You and your partner share all passwords to each other’s social Internet accounts (e.g. Facebook, twitter, email, online games)” (abbreviated to share passwords), “You and your partner know all of each other’s Internet friends” (abbreviated to know friends), “You and your partner have access to each other social networking sites” (abbreviated to account access), “My partner and I agree that we do not have online relationships with former romantic partners” (abbreviated to no former partners), and “My partner and I agree that we do not flirt with online friends” (abbreviated to no flirting). The scores were then reverse coded so that higher scores on each item represented greater agreement on the item.

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted using Amos 18 (Arbuckle, 2009) to test for the fit of latent variables accounting for Internet boundaries. These tests were conducted for men and women as one group. Model fit indices are considered acceptable when the Chi-square is non-significant, the CFI and TLI is greater than 0.90, and the RMSEA is less than 0.08 (Kline, 2011). CFA for a two-factor model produced an acceptable fit (χ2 (4) = 5.68, p = .22; TLI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.05, 90% CI: .00 to .12). The first factor was labeled Openness (share passwords: λ = .81, know friends: λ = .82, and account access: λ = .91), and the second factor was labeled Fidelity (no former partners: λ = .86 and no flirting: λ = .98). Chi-square difference test of a single-factor and the two-factor model indicated that the two-factor model fit the data significantly better than a single-factor model (χ2diff (1) = 196.83, p < .001). Following the CFA results, internal reliability estimates were conducted for both factors. The Cronbach’s alpha was .86 for men and .90 for women for Openness and .94 for men and .86 for women for Fidelity. The ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale (ENRICH; Fowers & Olson, 1993) is a 10-item scale. Respondents responded to items using a 5-point Likert scale from “1 for strongly disagree to 5 for strongly agree”. Sample responses include: “I am very happy with how we handle role responsibilities in our marriage” and “I am not happy about our communication and feel my partner does not understand me.” After reverse coding negative items, all scores were summed so that higher scores indicated greater satisfaction. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current study was .85 for men and .86 for women.

The Trust in Close Relationships Scale (TCR; Holmes & Rempel, 1989) is a 16-item scale that consists of three dimensions of trust: faith, dependability, and predictability. Participants responded to items along a 7-point scale from 1 for “completely agree” to 7 for “completely disagree”. Sample items include: “My partner behaves in a very consistent manner,” and “My partner has proven to be trustworthy and I am willing to let my partner engage in activities which other partners find too threatening.” Positive items were reverse coded and summed so that higher scores indicated higher trust. Cronbach’s alpha for the current study was strong at .93 for men and .90 for women.

and Dependent Variables.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Preliminary analyses were conducted and no problems were detected with normality (where skewness was less than 3 and kurtosis less than 10) or multicollinearity of study variables (Kline, 2011). An examination of the intercorrelations of study variables indicated that the relationships between the five Internet boundaries and relationship satisfaction and trust were positively related and statistically significant, with the exception of the Satisfaction and Account Access (see Table 2). Next, the research questions were tested using t-tests, confirmatory factor analysis, and structural equation modeling.

Data indicated that participants generally agreed with all five Internet boundaries (M > 5.50) -- share passwords, know friends, account access, no former partners, and no flirting. Further examination of the difference of use between men and women indicated one significant difference. Women were found to have significantly greater agreeability than men with “no flirting” as a boundary (t(203) = -2.01, p < .05; M = 6.31, SD = 1.57 for men; M = 6.69, SD = 1.01 for women). These results suggest men and women in this study did not differ on average in the degree they shared passwords and online friends, had access to their partners’ online accounts, and had no contact with former romantic partners.

(N = 98 for Men, N = 107 for Women).

Multiple Sample Structural Equation Model

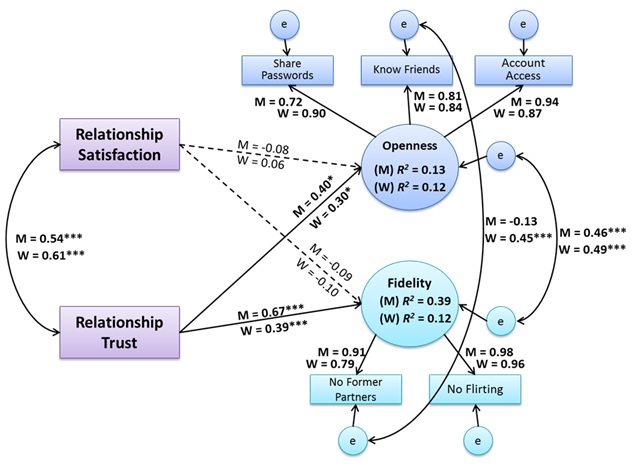

A multiple-sample structural equation model (SEM) using Amos 18 (Arbuckle, 2009) tested trust and satisfaction as predictors of Internet Openness and Fidelity for samples of men and women simultaneously. First, control variables (i.e., relationship length, education level, race, and age) were included in the model. However, these control variables did not change the pattern of significance. Thus, to increase parsimony and power, those controls were removed from the model to increase ease of interpretation of the primary results. Second, the model was tested for configural and weak invariance using MPlus 6.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2010) to determine if the model measured similar constructs for both men and women. Results indicated that the change in CFI did not exceed 0.01, meaning that the model measured the constructs – Internet boundaries, trust and satisfaction – equivalently for men and women (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). These results made comparing the groups possible. The structural equation model showed good model fit (χ2 (18) = 18.17, p = .45; TLI = 1.00; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.01, 90% CI: 0.00 – 0.06) (see Figure 1 and Table 3).

Figure 1. Multiple Sample Structural Equation Model of Internet Boundaries (N = 205). Group comparisons

of structural model by gender (M = Men, W = Women). Model fit indices: χ2 (18) = 18.17, p = .45; TLI = 1.00; CFI = 1.00;

RMSEA = 0.01, 90% CI: 0.00 – 0.06. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

For men, H1 was not supported: The paths from Satisfaction to both Openness and Fidelity were not significant, while H2 was supported: The paths were significant from Trust to Openness (Β = .40, p < .01) and from Trust to Fidelity (Β = .67, p < .001). The correlations for the factors, Openness and Fidelity (r = .46, p < .001), and the exogenous variables, Satisfaction and Trust (r = .54, p < .001), were significant. The model for men accounted for 39 percent of the explained variance in Fidelity and 12 percent of the variance in Openness.

For women, H1 was not supported: The paths from Satisfaction to both Openness and Fidelity were not significant, while H2 was supported: The paths were significant from Trust to Openness (Β = .30, p < .05) and from Trust to Fidelity (Β = .39, p < .001). The correlations between the residuals for the factors, Openness and Fidelity (r = .49, p < .001), and the exogenous variables, Satisfaction and Trust (r = .61, p < .001), were significant. For women, the model accounted for 12 percent of the variance in Openness and Fidelity respectively.

Comparison between men and women: The paths from Trust to Openness and Fidelity were significant and the paths from Satisfaction to the Openness and Fidelity were not significant. Only two significant differences between the strength of parallel paths for men and women were found. First, the path from Trust to Fidelity was found to be significantly stronger for men than women (t (203)= -3.97, p < .05; Β = .67, p < .001 for men; Β = .39, p < .001 for women; see Figure 1). Second, the correlation from “no former partners” to “know friends” was significantly stronger for women than men (t(203) = -3.16, p < .05; r = .45, p < .001 for women; r = -.13, p = ns for men).

for Men and Women Multiple Sample Structural Equation Model (N =205).

Discussion

Internet Boundaries

Identifying boundary setting for Internet use is a new area that has not been fully investigated. This exploratory study examined five possible Internet boundaries married individuals may use for social networking and how their use is associated with relational trust and satisfaction. Overall, findings suggest that many couples may have boundaries for social networking. More specifically, confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the five boundary items best fit into two broader latent constructs. The first, Openness, refers to individuals’ beliefs that each partner’s social networking activity should be open for the partner to view through sharing passwords, knowing each other’s online friends, and having access to each other’s online social networking accounts, such as email, Facebook, Twitter, and online games. The second boundary, Fidelity, refers to the individuals’ beliefs that emotional fidelity extends to online activity through not flirting with others online and having no online relationships with former romantic partners.

These results suggest that there are at least two main constructs that capture the possible myriad of ways in which married individuals maintain their relationships online. Openness speaks of sharing and not hiding or having secret relationships. Fidelity speaks of setting limits for online contact. Both strategies appear to complement each other. In some ways, these strategies reflect the relationship maintenance strategies -- assurances and sharing social networks -- identified by Canary and Stafford (1994). For example, the act of sharing information such as passwords to social networking sites can be reassuring to one’s partner and send the message that one has nothing to hide. Similar explanations apply to curbing flirtatious communication that can be construed as an act of fidelity thereby helping to maintain the relationship.

Finally, results revealed one significant difference between men and women for the five social networking boundaries. The correlation between “know friends” and “no former partners” was strong for women while nearly nonexistent for men. This indicates that one way women, but not men, may expect their partner to assure them that they have no online relationships with former romantic partners is to share their online friends. Therefore, sharing friends may be a significant link to online fidelity for women. Further research would be appropriate to determine the validity of this finding.

The Role of Trust

Factors that are associated with boundaries for Internet use were examined. Trust but not relationship satisfaction was significantly related to the use of Internet boundaries for both men and women. Furthermore, trust had stronger association with fidelity-type Internet boundaries for men than for women.

Results indicate that those with higher ratings of trust in their marital relationship also show greater acceptability for Openness and Fidelity pertaining to social networking in this cross-sectional study. The results are supported by Lewicki and Bunker’s (1995) stage development theory of trust that posits that at the highest level of trust, the full internalization of the other’s desires and intentions means understanding each other, agreeing on what each other wants and supporting the pursuit of common goals. Given that participants in this study were married for an average of 27 years and that the mean score of trust was high (M = 94.32), it is possible that this highest level of trust had been reached by many participants in the current study. Trust at this stage for these participants is evidenced by behaviors that protect the relationship and demonstrate care and concern for the well-being of their partners.

Interestingly, results are contrary to a popular belief that trust implies increased privacy. Rather, trust is associated with greater transparency for Internet social networking. This finding supports the idea that Internet boundaries serve to protect relationships because increased trust is associated with increased Openness. As couples are less open, it is possible that secrecy could form, which has been identified as a necessary cause for infidelity (Duba et al., 2008; Woolley & Gold, 2010). Without secrecy, infidelity does not typically occur. Therefore, openness may function as a protective factor in relationships.

These results are also congruent with past research on trust in relationships where trust is highly related to expectations (Holmes, 1991). According to trust development theory, the long marital length of the sample population represents couples that would have developed the final stage of trust, where expectations and faith defines trust (Holmes, 1991; Lewicki & Bunker, 1995). It is theorized that boundaries are created from expectations and rules that protect the relationship from harm. In the current study it appears that the greater the trust, the more likely that trust is expressed through Internet boundaries that represent expectations for fidelity and openness. This explanation does not support a common belief that trust implies a lack of need to prove or show fidelity. Rather, it supports that mature relational trust represents expectations based on the partner’s behaviors and motivations. Therefore, the finding that higher trust is associated with increased boundary use is congruent with trust development theory.

The Role of Satisfaction

Relationship satisfaction did not appear to relate to the use of Internet boundaries, suggesting that the setting of boundaries for Internet use has a different function than relationship maintenance behaviors (Canary & Stafford, 1994). As expected and consistent with previous findings, relationship satisfaction and trust shared a strong positive relationship (Campbell et al. 2010; Fleeson & Leicht 2006; Goldberg, 1982). The lack of relationship between satisfaction and the Internet boundaries Openness and Fidelity, however, indicates that trust and satisfaction have different roles in marriage. Therefore, trust and satisfaction may be expressed very differently. It may be that relationship satisfaction is more closely associated with other kinds of boundaries, such as how it is used for communication purposes between the partners (Miller-Ott et al., 2012). As satisfaction is most often included as an outcome variable, it is not yet clear what the role of satisfaction may be. The current study indicates that satisfaction may not be linked to expectations and rules related to Internet use.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. To begin, data were gathered at a single time point, and therefore no conclusions of causality, prediction, or directionality can be stated with empirical support. To better understand how Openness and Fidelity are impacted by or impact trust and satisfaction, data across multiple time points would be necessary.

The sample in this data set represented a fairly homogenous group of White middle-aged parents, with an average age of 52 years, who tended to have higher education, and have children in family studies programs. Results lack generalizability to the general populous. Also, there are likely many couples who took the survey, but were not able to be appropriately matched. Consequently, the gender differences found could be an artifact of non-independence of the data. Furthermore, Internet boundaries may be different across generational cohorts, especially with the younger cohorts who have been raised in a digital society. Replication of these findings across a broader, more diverse sample is needed.

Finally, possible spurious and confounding variables were not tested. The exploratory nature of this study made a search for these variables impractical. However, the presence of a relationship among the study variables indicates a necessity to replicate the findings while controlling for possible spurious associations. It is possible that the results found between trust and the Internet boundaries may be a result of a hidden factor, such as age, commitment, or beliefs about social networking. The implications of these findings therefore should be taken with caution.

Implications

Despite these limitations, the current study adds a key component to the literature on how middle-aged, married individuals manage social networking within their relationships. The majority of current research on social networking and intimate relationships uses first-year undergraduate students in relatively new relationships, most often with an average relationship length of only one or two years. This is one of the first studies to examine social networking with long-term married adults. It is important that researchers continue to examine this population as the effects may be quite different than those found in younger couples.

This study is also one of the first to look at how couples’ boundaries for social networking are associated with relationship processes. It is important that we better understand the ways that the Internet benefits romantic relationships so that clinicians can better utilize this system within treatment. As the Internet’s many utilities grows and as it starts to hold greater presence in the ways in which couples connect and communicate, it becomes ever more important for the field to better understand how couples use it so that clinicians can find ways to integrate it in therapy.

Internet boundaries is a new area of couple research. These findings indicate that married individuals hold varying boundaries for social networking in their relationship. The purpose that these boundaries serve and what other boundaries may exist are unknown. Further investigation into the nature, purpose, and effects that these boundaries have in couple relationships is needed. Refinement is further needed for the currently identified Internet boundaries. As this was an exploratory study, the creation and testing of an empirically supported measure for Internet boundaries was not intended. The creation of an empirically validated measure for Openness, Fidelity, and other boundaries would help future researchers investigate the nature of Internet boundaries more fully. To begin, a qualitative inquiry to generate other possible boundaries may be helpful into creating such a measurement tool. Beyond creating empirically validated scales, it would be appropriate to begin investigating more fully how Internet infidelity impacts and is impacted by the use of Internet boundaries. Data in the current study was insufficient to make such an investigation. A larger sample with a history of Internet infidelity would allow for such an examination.

For clinicians, the findings suggest that the boundaries of Openness and Fidelity are associated with trust in romantic relationships. It may be then, that when trust is broken through online infidelity, an investigation into the violated boundaries may reveal a starting point for understanding the contributing factors of the infidelity. Further investigation into the boundaries violated through the development of the online infidelity could allow clinicians a starting point in treating infidelity.

Conclusion

Little is understood about the impact of technology in couple relationships or how couples manage its influence. The present study contributes to the literature by identifying two Internet boundaries and presenting how trust and satisfaction are related to the use of Internet boundaries. Findings suggest that couples in long-term committed relationships have boundaries or rules for social networking. Furthermore, trusting one’s partner, but not relationship satisfaction, contributes to behaviors that reflect sharing online social networking information and curb online flirting and relationships with former romantic partners. These findings correspond with trust development theory where it is expected that long-term committed relationships would display trust by engaging in behaviors that promote the relationship.

References

Arbuckle, J. L. (2009). Amos 18 user's guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS.

Boon, S. D., & Holmes, J. G. (1991). The dynamics of interpersonal trust: Resolving uncertainty in the face of risk. In R. A. Hinde & J. Groebel (Eds.), Cooperation and prosocial behavior (p. 190-211). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Brenner, J., & Smith, A. (2013). 72% of online adults are social networking site users. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/social-networking-sites.aspx

Butler, M. H., Harper, J. M., & Seedall, R. B. (2009). Facilitated disclosure versus clinical accommodation of infidelity secrets: An early pivot point in couple therapy. Part 1: Couple relationship ethics, pragmatics, and attachment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 35, 125-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00106.x

Butler, M. H., Seedall, R. B., & Harper, J. M. (2008). Facilitated disclosure versus clinical accommodation of infidelity secrets: An early pivot point in couple therapy. Part 2: Therapy ethics, pragmatics, and protocol. American Journal of Family Therapy, 36, 265-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01926180701291253

Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Boldry, J. G., & Rubin, H. (2010). Trust, variability in relationship evaluations, and relationship processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 14-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0019714

Canary, D. J., & Stafford, L. (1994). Maintaining relationships through strategic and routine interactions. In D. J. Canary & L. Stafford (Eds.), Communication and Relationship Maintenance. (pp. 3-22). New York: Academic Press.

Chan, D. K., & Cheng, G. H. (2004). A comparison of offline and online friendship qualities at different stages of relationship development. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21, 305-320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407504042834

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233-255.

Darvell, M. J., Walsh, S. P., & White, K. M. (2011). Facebook tells me so: Applying the theory of planned behavior to understand partner-monitoring behavior on Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14, 717-722. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0035

Duba, J. D., Kindsvatter, A., & Lara, T. (2008). Treating infidelity: Considering narratives of attachment. The Family Journal, 16, 293-299. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1066480708323198

Duggan, M., & Smith, A. (2013). Social media update 2013. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Social-Media-Update.aspx

Duran, R. L., Kelly, L., & Rotaru, T. (2011). Mobile phones in romantic relationships and the dialectic of autonomy vs. connection. Communication Quarterly, 59, 19-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2011.541336

Elphinston, R. A., & Noller, P. (2011). Time to face it! Facebook intrusion and the implications for romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14, 631-635. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0318

Fife, S. T., Weeks, G. R., & Gambescia, N. (2008). Treating infidelity: An integrative approach. The Family Journal, 16, 316-323. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1066480708323205

Fleeson, W., & Leicht, C. (2006). On delineating and integrating the study of variability and stability in personality psychology: Interpersonal trust as illustration. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 5-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.004

Fletcher, G. J. O., Simpson, J. A., & Thomas, G. (2000). The measurement of perceived relationship quality components: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 340-354. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167200265007

Fowers, B. J., & Olson, D. H. (1993). ENRICH marital satisfaction scale: A brief research and clinical tool. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 176-185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.7.2.176

Fox, S., & Rainie, L. (2014). The web at 25. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewInternet.org/2014/02/25/the-web-at-25-in-the-u-s

Goldberg, M. (1982). The dynamics of marital interaction and marital conflict. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 5, 449-467.

Gordon, K. C., Baucom, D. H., & Snyder, D. K. (2004). An integrative intervention for promoting recovery from extramarital affairs. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 30, 213-231. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01235.x

Helsper, E. & Whitty, M. (2010). Netiquette within married couples: Agreement about acceptable online behavior and surveillance between partners. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 916-926. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.02.006

Hertlein, K. M., & Blumer, M. L. (2013). The couple and family technology framework: Intimate relationships in a digital age Brunner-Routledge.

Hertlein, K. M., & Piercy, F. P. (2006). Internet infidelity: A critical review of the literature. The Family Journal, 14, 366-371. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1066480706290508

Holmes, J. G. (1991). Trust and the appraisal process in close relationships. In W. H. Jones, & D. Perlman (Eds.), Advances in personal relationships (pp. 57-104). Oxford, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Holmes, J. G., & Rempel, J. K. (1989). Trust in close relationships. In C. Hendrick (Ed.), Close relationships. Review of personality and social psychology, Vol. 10 (pp. 187-220). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1997). Neuroticism, marital interaction, and the trajectory of marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1075-1092. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.5.1075

Kerkhof, P., Finkenauer, C., & Muusses, L. D. (2011). Relational consequences of compulsive internet use: A longitudinal study among newlyweds. Human Communication Research, 37, 147-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01397.x

Klacsmann, A. N. (2008). Recovering from infidelity: Attachment, trust, shattered assumptions, and forgiveness from a betrayed partner's perspective. ProQuest.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. (1995). Trust in relationships: A model of trust development and decline. In B. Bunker & J. Rubin (Eds.), Conflict, cooperation and justice (pp. 133-173). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Miller-Ott, A. E., Kelly, L., & Duran, R. L. (2012). The effects of cell phone usage rules on satisfaction in romantic relationships. Communication Quarterly, 60(1), 17-34.

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families and family therapy. USA: Harvard University Press.

Muthén, L.K., & Muthén, B.O. (1998-2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Riva, G. (2002). The sociocognitive psychology of computer-mediated communication: The present and future of technology-based interactions. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 5, 581-598. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/109493102321018222

Schneider, J. P. (2003). The impact of compulsive cybersex behaviours on the family. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 18, 329-354. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/146819903100153946

Stafford, L., & Canary, D. J. (1991). Maintenance strategies and romantic relationship type, gender and relational characteristics. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 8, 217-242. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407591082004

Tallman, I., & Hsiao, Y. (2004). Resources, cooperation, and problem solving in early marriage. Social Psychology Quarterly, 67, 172-188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/019027250406700204

Thieme, A. L. (1997). Relationship rules that guide expressions of love and their connection to intimacy, dominant dialectical moments, and love ways. ProQuest Information & Learning. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 57(12-A), 4984-4984. (Electronic; Print). (1997-95011-036)

Whitty, M. T. (2008). Liberating or debilitating? An examination of romantic relationships, sexual relationships and friendships on the net. Computers in Human Behavior, 24, 1837-1850. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.02.009

Woolley, S. & Gold, L. (2010). Healing affairs using emotionally focused couple therapy. American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy Annual Conference, Atlanta, GA.

Zak, A. M., Gold, J. A., Ryckman, R. M., & Lenney, E. (1998). Assessments of trust in intimate relationships and the self-perception process. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138, 217-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224549809600373

Zickuhr, K. (2013). Who’s not online and why. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Non-internet-users.aspx

Zickuhr, K. & Smith, A. (2012). Digital differences. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Digital-differences.aspx

Correspondence to:

Aaron Norton, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Family Therapy

Department of Family Sciences

Texas Woman's University

Email: anorton(at)twu.edu