Cyber-bullying: An exploration of bystander behavior and motivation

Emily Shultz1, Rebecca Heilman2, Kathleen J. Hart3Abstract

Keywords: Cyber-bullying; bystander; intervention; motivation

Introduction

As society continues to embrace communication on social-networking sites, cyber-bullying (CB) has become a more common occurrence and a substantial concern. Tokunaga (2010) provided an integrative definition of CB derived from a meta-synthesis of current research and theories, describing it as “any behavior performed through electronic or digital media by individuals or groups that repeatedly communicates hostile or aggressive messages intended to inflict harm or discomfort on others” (p. 278). Previous studies have used similar definitions of CB (Freis & Gurung, 2013; Hinduja & Patchin, 2012, 2013; Li, 2010), but it is not clear that these definitions reflect the views of the general public. Indeed, it may be difficult to differentiate teasing from CB. Desmet et al. (2012) conducted focus groups in which they asked participants to describe CB and differentiate it from other forms of communication. Whereas participants defined ‘teasing’ as a communication among friends that was not intended to be hurtful and where the object of the teasing may even find the comments funny, they defined CB as communication that involves intentional harm. Similarly, in a comparison study of CB definitions across six European countries, Menesini et al. (2012) concluded that among the five definitional criteria for CB (intentionality, imbalance of power, repetition, anonymity, and public vs. private), the two clearest dimensions across the countries were imbalance of power and intentionality.

Thus, the definition of CB often relies on the perceptions and judgments of bystanders (observers) to the interaction to identify when the bully is asserting himself/herself over the victim, and when he or she is causing intentional harm to the recipient. Clearly, a bystander’s perception may vary by the context of the interaction and the specific lens through which he or she views the situation; this lens can be influenced by culture, age, sex, and social relationships with the involved parties (Thornberg et al., 2012).

Although the prevalence of CB depends on the definition utilized and the specific sample under study, previous research indicates that CB is prevalent in a wide variety of settings. In a meta-analysis of CB, Tokunaga (2010) found that, on average, approximately 20-40% of youths reported being victimized by a cyber-bully, whereas Hinduja and Patchin (2012) found that approximately 6-30% of adolescents have been the victims of some form of CB. Addressing the rate of perpetrators, Hinduja and Patchin (2013) found that 28% of adolescents self-reported engaging in CB behaviors towards others, with the likelihood to engage in CB influenced by peers’ engagement in CB. They found that 62% of the students who said “all” or “most” of their friends had cyber-bullied others in the previous six months reported that they had also engaged in CB in the last 30 days, whereas only 4% of the students who said “none” of their friends had cyber-bullied others reported engaging in CB.

Tokunaga’s (2010) meta-synthesis suggests that there may be a curvilinear relationship between age and frequency of CB victimization, such that the highest frequency of victimization occurs between the ages of 12 and 13, with a lower rate of victimization occurring from ages 10 to 12 and 14 to 20. Although the majority of prior research has examined CB within elementary and high school settings where CB may occur most frequently, examining the young adult population should not be neglected because of their frequent utilization of social networking sites. Previous studies indicated that college students report spending from 30 minutes (Pempek, Yermolayeva, & Calvert, 2009) to 60 - 120 minutes each day on Facebook (Kalpidou, Costin, & Morris, 2011). Schenk and Fremouw (2012) reported that approximately 9% of college students were victims of CB and that the victims scored higher than matched controls on psychological factors such as depression and anxiety, and in suicidal ideation. Considering the negative mental health impact of CB even in college aged participants, it is important to gain greater understanding of this phenomenon in this age group.

The social dynamics of CB are distinct from traditional bullying because of factors attributable to the electronic device, including feelings of anonymity and the ability to communicate without physical face-to-face interactions (Tokunaga, 2010). As previous scholars have established, these differences indicate that CB should be examined with a separate theoretical lens (Tokunaga, 2010). In fact, previous research has suggested that CB may be worse for victims than traditional bullying methods because there is seemingly no escape and the harmful material is preserved and easily spread (Freis & Gurung, 2013; Li, 2010). Similarly, Barlinska, Szuster, and Winiewski (2013) postulated that victims may experience more harm from CB than face-to-face bullying because online contact increases the likelihood for negative bystander behavior, in that bystanders may spread the CB content to wider audiences by virtue of the platform (such as a Facebook page viewed by a large number of “friends”), or by forwarding it to other media sites. Thus, as CB becomes a prominent method of bullying that may cause significant psychological harm to victims, it is essential to understand the ways in which bystanders respond to CB, and their motives for doing so.

CB Bystander Intervention Strategies

An analysis of bystander behavior has identified both active and passive reactions to CB from individuals who witness it. Among the active reactions to CB, bystanders’ distinct intervention strategies are apparent. Under the assumption that those who witness the act of CB actively choose to intervene in the CB situation by deleting or forwarding a CB message, Barlinska et al. (2013) operationally defined negative bystander behavior as choosing to forward a negative instant message rather than delete it from the system, which spreads the CB message to a wider audience and perpetuates the CB, thus potentially increasing psychological harm to the victim. In this situation, the bystander becomes a bully by actively engaging in the negative comments about the victim. Freis and Gurung (2013) utilized a live chat feature to observe bystander responses of female college students as they interacted with two confederates (one “victim” and one “bully”) and identified a series of intervention strategies among participants. They categorized the responses as: say “stop/bully;” foster discussion; try and change the topic; comfort the victim; attack the bully; pass; and other. Although 91% of their participants chose to intervene using one or more of the defined strategies during the interaction, 44% of the sample still said “pass” at some time during the conversation. Furthermore, those who intervened were more likely to utilize indirect forms of intervention, such as changing or avoiding the topic rather than engaging in a direct intervention (e.g., saying “stop/bully” or comforting the victim).

Machackova, Dedkova, Sevcikova, and Cerna (2013) suggested that bystander behavior could be differentiated into confrontational versus supportive behavior. Whereas confrontational bystander behavior involves the bystander directly confronting the bully in defense of the victim, supportive bystander behavior encourages the victim and includes behavior such as telling the victim to ignore it, trying to comfort the victim, or recommending the victim to tell someone who could help. They found that 76% of bystanders self-reported offering some form of support in a prior CB situation and many participants reported offering more than one form of support. Specifically, from the least endorsed to the most frequently endorsed items, their participants reported: telling the victim to ignore it (55%); trying to comfort the victim (54%); telling the victim it was not worth the worry (53%); telling the victim they were sorry about what happened (51%); keeping the victim occupied so he/she would not think about the CB (40%); recommending the victim tell someone who could help (36%), and/or; giving the victim technical advice about how to make the CB stop (35%). Studies by Machackova et al. (2013) and Fries and Gurung (2012) mark beginning attempts to identify the types of responses bystanders might employ when they encounter CB.

CB Bystander Motivations

In order to gain an understanding of bystander response to CB, several studies have attempted to identify the underlying factors and motivations that prompt bystanders to confront or support, remain silent, or contribute to the victimization. Previous research has suggested that personality traits, including empathy, extraversion, and self-efficacy, can increase the likelihood that a bystander will choose to supportively intervene in CB (Freis & Gurung, 2013; Polyhonen, Juvonen, & Salmivalli, 2010). Freis and Gurung (2013) found that individuals with high empathy and high extraversion were more likely to intervene in CB situations than those who were lower in these traits. Using a middle childhood and early adolescence sample, Polyhonen et al. (2010) found that a strong sense of self-efficacy and greater social status within the peer group was associated with defending victimized classmates in traditional bullying situations. Bystander’s behavior may also be influenced by priming effects. For example, Barlinska et al. (2013) found that when bystanders were exposed to either affective or cognitive empathy stimuli, they were less likely to forward CB material onto wider audiences and were more likely to simply delete the CB content than participants who had not been exposed to those stimuli.

Although there are differences between traditional bullying and CB in the method of bullying, a common element of bullying remains consistent, in that it involves attacking another individual either physically, verbally or emotionally. Furthermore, bystander’s behavior online may also relate to their behavior to bullying offline, as suggested by the Co-construction theory (Wright & Li, 2011). This theory is supported by previous research that demonstrated the positive relationship between prosocial behaviors face-to-face to online prosocial behaviors (Wright & Li, 2011). Generally, prosocial behavior motivations include altruism, which is a desire to improve the welfare of others, and reciprocity, which is a desire to be helped in the future by those whom they helped. These motivations have also been positively correlated with prosocial behavior online, specifically in anonymous online gaming scenarios (Wang & Wang, 2008). Furthermore, Machackova et al. (2013) indicated prosocial behavior as the only individual characteristic that was a significant predictor of supportive bystander behavior in a hierarchal regression model. It is important to note that, although other individual factors (such as age, sex, self-esteem, and problematic relationships) yielded no effect on supportive behavior, Machackova et al. found that contextual factors (such as existing relationships with the victim, upset feelings evoked by witnessing victimization, and direct requests for help from the victim) were significantly related to supportive bystander behavior in the regression model.

Considering the parallels between offline and online prosocial behavior, bystander motivations in traditional bullying provide an initial framework for examining bystander motivations in CB. Thornberg et al. (2012) described a set of motive domains that might influence bystander motivation to intervene in traditional bullying situations: interpretation of harm, emotional reactions, social evaluating, moral evaluating, and intervention self-efficacy. According to this model, bystanders intervene if they perceive that the bullying is causing significant harm to the victim. Researchers emphasized that an interpretation of no harm could be due to a habituation of bullying behavior. Within the domain of emotional reactions, empathy encourages bystanders to intervene, whereas fear of being victimized and audience excitement (desire to watch the bullying because it provides entertainment) demotivates bystanders to intervene. The social evaluating component explains that friendship with a victim motivates the bystander to intervene, while friendship with a bully and a highly socially ranked bully demotivates the bystander to intervene. Bystanders also engage in a moral evaluation of the bullying situation: A bystander’s belief that bullying is wrong motivates intervention, but moral disengagement (i.e., bystanders believe it is not their moral responsibility to intervene) demotivates intervention. Additionally, if bystanders blame the victim, they are less likely to intervene. Finally, bystanders select an intervention strategy based on how effective they believe their actions would be.

Gaps in the Current CB Research

Although there has been research on CB in recent years, this research has been mainly focused on victim and bully behavior, and methodological limitations of the studies prevent generalizable, conclusive findings regarding bystander behavior. Some research has utilized simulations of realistic CB situations (Barlinska, et al., 2013; Freis & Gurung, 2013); however, other studies have only utilized self-report measures of prosocial behavior in bullying situations (Machackova et al., 2013; Wright & Li, 2011). Furthermore, CB has not been examined in the full variety of digital settings. For example, prosocial behavior has been studied in anonymous digital venues such as online gaming, but there is a lack of research in identifiable digital venues such as social networking sites (Wang & Wang, 2008). Additionally, a majority of the research on CB has been conducted with middle and high school students, ignoring an analysis of bystander behavior of young adults, who are highly active online (Kalpidou et al., 2011; Pempek et al., 2009) and who report incidents of CB (Schenk & Fremouw, 2012). The most vivid disparity, however, is the lack of understanding of bystander behavior and the motivation for bystanders’ responses to CB. Although Thornberg et al. (2012) addressed bystander motivations in traditional bullying and Freis and Gurung (2013) conducted an exploratory study of bystander behavior in an anonymous, live chat CB scenario, there is a gap in the research regarding bystander motivation in other CB situations, including those found on frequently used social networking sites and within the young adult population.

Present Study

The current research involved a realistic CB simulation on a social-networking site, utilized a young adult sample, and categorized bystanders’ open responses in order to examine patterns of their responses. Primarily, we were interested in understanding young adults’ responses to CB when they are the bystanders in that situation. Therefore, we presented a conversation in which two “friends” berated a third friend for behavior at a party. Participants had the opportunity to contribute to the conversation, which allowed us to categorize the types of comments they made into intervention strategies. We also asked participants to explain why they responded (or did not respond) at two different time points in the conversation simulation, which provided information about their motivation for their responses. We then examined how the broad categories of responses differed by participant’s empathy and social identification (i.e., whether they identified with the bullies or victim), hypothesizing that individuals high in empathy would more frequently identify with the CB victim, and respond more frequently using supportive forms of intervention than individuals who were low in this trait. In an exploratory capacity, we examined bystanders’ open-responses to an online conversation in order to establish a more comprehensive understanding of bystanders’ role in CB.

Method

Participants

Students (N = 149) volunteered to participate in this online study to earn research credit for their courses in the psychology department at a private university in the Midwest region of the United States. The title of the study as posted on recruitment information indicated it would involve Facebook, but they were not given specific information about the nature or purpose of the study. The sample was 69% women and 28% men (approximately 3% of our sample was missing this data) with a mean age of 20.34 (SD = 1.26, range = 18 to 27 years). The majority of the participants were juniors (40%), followed by sophomores (21%), seniors or 5+ year students (17%), and first year students (18%). The sample was 84% Caucasian, 6% Black or African American, 2% Hispanic, and 4% other or mixed racial background. Nine respondents (6% of the original sample) were excluded from analyses because they identified themselves as non-Facebook users. Participants were Facebook members for an average of 5.56 years (SD = 1.40 years, range = 2 - 9 years). Members reported logging-in an average of 5.25 times per day (SD = 4.74, range = 0 - 25 times) and spending 13.93 minutes per log-in (SD = 31.35, range = 0 - 360 minutes).

Measures and Stimuli

Empathy. The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI, Davis, 1980) is a 28-item scale that measures individual differences in empathy. The scale has been found to have high internal reliability (α ranging from .71 to.77) and high test-retest reliability (rs ranging from .62 to .71, Davis, 1980; 1983). The scale yields four subscales of empathy measuring perspective taking, fantasy, empathetic concern and personal distress. The items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (does not describe me well) to 5 (describes me very well). We used the Total IRI score for our analyses; this score ranges from 0 – 140 and in our sample, ranged from 66 to 121 (M = 96.17, SD = 11.31, α = .82).

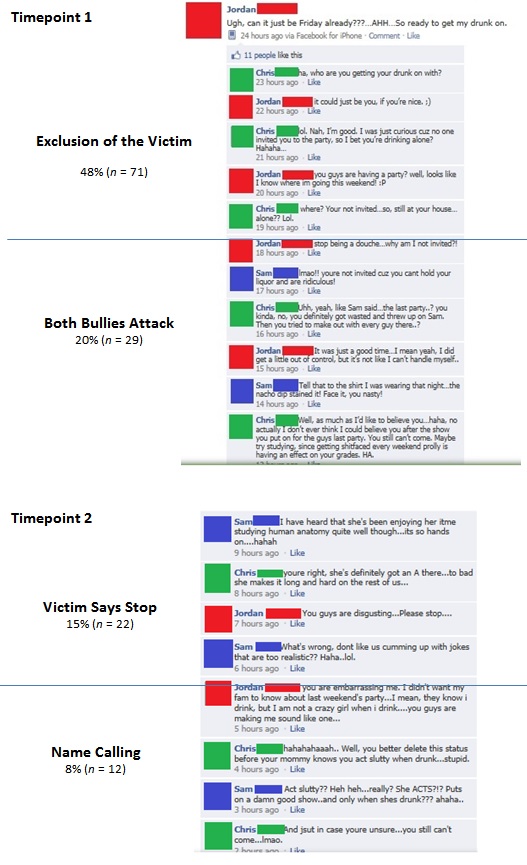

Facebook conversation. Participants viewed a fictitious Facebook conversation created by the researchers in two parts (Time 1 / Time 2). The conversation involved an online interaction among three college students; two students (“Sam” and “Chris”) posted comments on the third student’s (“Jordan’s”) feed in which they made negative comments about that student’s behavior at a recent party (see Appendix for the conversations). The conversation portrayed several types of CB, including exclusion (intentionally excluding a person from a group), flaming (sending angry, rude or vulgar messages), harassment (repeatedly sending offensive messages), denigration (put-downs), and outing and trickery (posting material that contains sensitive, private, or embarrassing information), as defined and established in previous research (Li, 2010).

The instructions to participants above the Facebook conversation read, “Imagine that these three people live in your dorm hall, or are close friends from high school and that this conversation has shown up on your newsfeed. Please read the conversation and click ‘next’ when you are finished to continue to the next page.” After reading the conversation (Time 1), participants were directed to the following page where they were asked, “Please select the person from the conversation that you feel you most identify with: Jordan (the status updater), Chris (the first commenter), or Sam (the second commenter).” This one-item question was used to measure participants’ social identification with a victim (Jordan) or a bully (Sam or Chris). Participants then were asked an open-answer question, “If you joined the conversation you just read, where would you join and what would your comment be?” Participants typed their response in a text box. The final question was to assess possible motivators of the bystanders and was also posed in an open-answer format: “Please explain why you chose to comment or why you chose not to comment on the conversation.”

Participants continued to another screen where the instructions for the second portion of the conversation (Time 2) stated, “This is a continuation of the Facebook conversation you read previously.” After they read the second screen, participants answered the same series of questions that were posed at Time 1. Lastly, participants were prompted to describe where in the conversation (considering what was presented in both Time 1 and Time 2) they thought bullying occurred; they were given the option to indicate that no bullying occurred, and to explain their reasoning for their response. As the conversation continued, the statements made to the victim gradually increased in vitriol.

Procedure

This study received approval by Institutional Review Board of the university where the study was conducted. Students were recruited through an online posting of study opportunities or a participant pool bulletin board that each included the study specific URL. If they chose to participate, students logged onto any computer with access to the internet and used the URL to access the online study stimulus materials and measures. Only those with the URL were able to participate.

When participants utilized the study URL, they first agreed to the statement of informed consent which described the study as a 30 minute task involving several short surveys inquiring about their personal Facebook use and attitudes, and responses to a brief scenario. They were informed that the purpose of the study was to examine the relationship between personality traits and Facebook interactions. To minimize ordering effects, participants were randomly assigned by the survey website to either read the Facebook conversation and answer questions about it, then complete the randomly ordered personality measures, or complete the randomly ordered personality measures then read and answer questions about the Facebook conversation. At the conclusion of the study, participants were given information about the complete purpose of the study and were notified that all individuals depicted in the Facebook conversation, and the conversation itself, were fictitious.

Development of categories. Using a deductive-inductive process for coding (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003), two of the authors coded participants’ responses to the Facebook simulation, including the participant’s direct comment and their stated reason for commenting or remaining silent. We decided to code comments and stated reasons separately for Time 1 and Time 2, the two parts of the conversation, because some participants drastically changed their responses based on the severity of the bullying and we wanted to capture these changes. We refined coding procedures for CB responses and bystander motivators while keeping consistent with grounded theory methods, until inter-rater discrepancies were resolved and consensus was reached. Utilizing previous literature (Freis & Gurung, 2013; Thornberg et al., 2012) and deductive reasoning, several bystander intervention strategies were established for coding purposes. We then employed inductive reasoning by altering coding categories in accordance with the participants’ responses to cyber-bullying. This deductive-inductive procedure led to the agreed upon final set of definitions for each category addressing bystander intervention strategy and motivation.

We coded participants’ direct comments to the Facebook conversation into several categories of intervention strategy, initially using pre-determined categories of bullying intervention from Freis and Gurung (2013): say “stop/bully”, foster discussion, try and change topic, comfort victim, attack bully, pass, and other. However, since their study involved a live response design and in a different digital venue (a private conversation), many comments did not fit into any of these categories (try and change topic; and pass), so, in keeping with grounded theory, we grouped similar comments together and created themes from the existing data (Allen, 2012; Thornberg et al., 2012). Confrontational and supportive intervention strategies were established as distinct categories, a distinction suggested by Machackova et al. (2013), with confrontational intervention indicating that the participant attacked the bullies (e.g., “you guys are jerks,” “get a life”), and supportive intervention indicating that the participant defended the victim (e.g., “give her a break,” “leave her alone,” “you guys need to stop”). Each comment was coded as one distinct intervention strategy, and if a participant utilized a combination of the strategies, the most prominent strategy was selected. Given the wide diversity of comments offered by the participants, we ultimately sorted responses into the following additional categories: would not comment; conversation does not belong on Facebook/online (e.g., “Facebook is not the place for this”); and joining the bullies (e.g., “lol”). We also created a second set of broader categories in order to take into account whether the intervention took place online or offline: no mention of intervention; supportive intervention online, supportive intervention offline, and confrontational intervention online. The final list of comment categories we used are listed in detail in Table 1, including examples of comments from participants.

To determine bystander motivators, participants stated reasons as to why they chose to comment or remain silent, which were initially coded by each rater who independently formed categories by grouping together similar responses and deriving descriptive themes in a collaborative coding process (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003). We sorted participants’ responses to the question “Why did you choose to comment or not comment?” into three overarching categories: Would not comment; would comment; and, indecisive/miscellaneous. In each of these broad categories, the motivators were further divided into a total of 14 subcategories, based on distinct themes that emerged from the responses. We allowed for responses to be in more than one subcategory because many participants provided multiple reasons for their response to the simulation. The bystander motivation themes, subcategories, and representative examples are listed in detail in Table 2. The categories of comments and motivators, although created with qualitative methods, were used quantitatively to describe trends in responding and to allow for comparison of response types by identification with the bully vs. victim and by empathy scores.

Results

Identification of Bullying

We first examined whether participants believed that bullying occurred, and where in the conversation they believed it occurred. The overwhelming majority (91%) responded that the conversation included bullying. Of these participants, the majority (48%, n = 71) responded that bullying began at the beginning of the conversation (when the victim was being excluded), 20% (n = 29) responded that bullying began when both bullies attacked (these elements occurred in Time 1, before the first opportunity for the participant to respond). In Time 2, 15% (n = 22) responded that bullying began when the victim said stop and 8% (n = 12) responded that bullying began with name calling. The Appendix presents the conversation, labels the types of bullying presented at different parts of the conversation, and the percentage of individuals who identified bullying as beginning in that portion of the conversation.

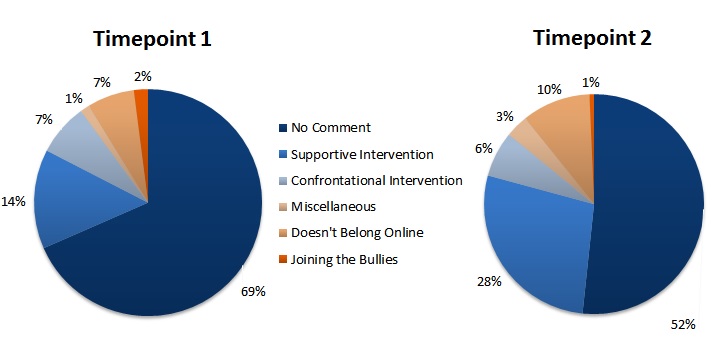

Bystander comments. By separately categorizing comments at the two parts of the conversation (Time 1/ Time 2), we were able to capture how participant’s behavior may have changed as the bullying became more severe over the course of the conversation. Although the rate of responding increased from Time 1 (30%) to Time 2 (47%) in the conversation, the majority of participants (52%) did not comment at either time point in response to the bullying simulation. Among those participants who commented, their comments were fairly long (Mlength = 26.2 words at Time 1; 27.5 words at Time 2). Figure 1 displays the frequency of responses within the identified categories (would not comment, confrontational intervention, supportive intervention, does not belong online, and miscellaneous) at each of the two time points. Among participants who chose to comment, the most frequent response was to engage in a supportive intervention (Time 1: 14%, n = 21; Time 2: 28%, n = 41).

Figure 1. Intervention categories in response to Facebook cyber-bullying simulation, including only the analysis of participant’s responses in the comments section of the survey (N= 149).

We also examined participants’ reactions to the conversation by categorizing their stated reason for their response. Some participants (Time 1: 9%, n = 14; Time 2: 11%, n = 16) who declined to comment indicated in their reason that they would choose to intervene offline in a supportive way, such as talking to the victim in person. By including the analysis of participants’ responses in the reason section of the survey and taking into account whether the intervention would occur online or offline, we created broader intervention categories (no mention of intervention; supportive intervention online, supportive intervention offline, and confrontational intervention online); the frequency of responses with these categories, separated by time point, are depicted in Figure 2. At Time 1, when bullies were excluding the victim, 38% (n = 57) of participants intervened, and at Time 2, when bullies were name calling, 58% (n = 86) of participants intervened in some way. At both time points, only a small percentage of participants responded in a way that confronted the bullies directly (Time 1: 7%, n = 10; Time 2: 9%, n = 13).

Figure 2. Broader intervention categories in response to Facebook cyber-bullying simulation, including the analysis of participant’s responses in the reason section of the survey and the valence of response online vs. offline (N= 149).

Empathy and social identification. Given the previous research that has suggested that factors such as empathy and social identification may increase the likelihood of bystander intervention (Freis & Gurung, 2013; Thornberg et al., 2012), we examined the frequency of participants’ identification with the bullies versus victim at the two response opportunities. At Time 1, the majority of the participants (64%) reported identifying with the bully (vs. 36% who identified with the victim), but by Time 2, a greater majority (83%) reported that they now identified with the victim (vs. 17% who reported identification with bully). Whereas the IRI (empathy) total scores of those who identified with the bully at Time 1 did not differ from those who identified with the victim at Time 1, t (146) = 1.12, p = .26, there was a significant difference in the IRI scores of those who identified with the bullies vs. with the victim at Time 2, t (146) = 3.23, p = .001. Table 3 summarizes the means, standard deviations and t-test findings for the IRI by bully/victim identification at each time period.

with the Bully or the Victim at Time 1 and Time 2.

Secondly, we examined if the frequency of participants’ interventions differed by their identification with the victim versus one of the bullies. Chi squares analysis utilizing the broader comment categories from Figure 2 (no mention of intervention, supportive intervention online, supportive intervention offline, and confrontational intervention online) indicated that individuals who identified with the victim were more likely to supportively intervene than individuals who identified with one of the bullies, at both Time 1, χ2 (149, 3) = 22.82; and Time 2, χ2 (149, 3) = 9.72, p < .05. These results are displayed in Table 4.

at Time 1 and Time 2.

In light of these findings, we examined whether participants’ empathy differed across the comment categories. Using the comment categories from Figure 2, we conducted ANOVAs to compare the IRI scores of participants who engaged in the four different types of broad responses at each time period (no mention of intervention, supportive intervention online, supportive intervention offline, and confrontational intervention online). However, we did not find differences in empathy scores at Time 1, F = 1.67, p = .18, or at Time 2, F = 1.62, p = .19.

Bystander motivators. As previously explained and displayed in Table 2, participants’ reasons for commenting or not commenting were sorted into 14 themes to better understand bystander’s motivators within three overall categories: motivator for not commenting; motivator for commenting, and; indecisive, other response options or miscellaneous. The accompanying paragraphs briefly describe the development of each of the themes to enlighten the reader on how we conceptualized the stated motivations of the participants.

Motivators for not commenting. Some participants indicated that they “did not want to be involved,” or they indicated that they purposely avoided commenting or intervening because they did not feel comfortable responding to the simulated CB situation. This theme encompassed a variety of responses, including individuals responding that a comment was not their place, was none of their business, they wanted to avoid drama, were afraid that the bullies would attack them too, and/or found the conversation uncomfortable or awkward.

The previous theme was distinguished by participants who were demotivated to comment because of fear, avoidance, and/or uncomfortableness; however, there were also participants who were unwilling to intervene because they felt “helpless and/ or their comment would cause more trouble.” These individuals indicated that they disagreed with the way the victim was being treated, but also specifically stated that they believed their comment would not be effective, or that their comment would cause the conflict to escalate.

Other participants stated that they found the conversation “stupid, immature and/ or unnecessary.” We interpreted their stated motivators to convey that a group of participants chose not to comment because they found the conversation unworthy of their time or pointless.

Lastly, another sub-group of participants indicated that their beliefs “against alcohol/ drinking/ partying” demotivated them to comment. These individuals further explained that they did not comment because they disagreed with the topic of conversation and did not want to be associated with those topics.

Motivators for commenting. Some participants commented in order to intervene on behalf of the victim. A subset of participants “wanted to defend the victim (Jordan) and stop the conversation,” which we interpreted to communicate that their moral convictions motivated them to intervene. Within this theme, often times individuals thought about Jordan as one of their friends and indicated that they intervened because they felt that no one should be treated in such a manner.

Other participants commented because they “wanted to mediate in the conversation” in order to encourage empathy for the victim; for example, these responses included statements indicating that the victim should be given a second chance and should not be harshly judged for a single incident. In contrast to individuals who chose to “defend the victim” who explicitly chose the victim’s side, individuals who expressed wishes to “mediate” in the conversation did not explicitly choose sides and instead expressed that their comment was an effort to indirectly stop the bullying in a manner that was neither confrontational nor overly supportive toward the victim.

There were also some participants that commented on the conversation in a manner that was extremely supportive, such as those who commented to “convince the victim (Jordan) that the other commenters are not worth her time and/ or invite her to another event”, in order to reach out with social support to her. It is interesting that some participants’ comments were neither supportive nor confrontational. Thus, another theme was created to encompass the participants who commented with statements indicating they would “remind all commenters that this is a public media site.” Many of them wrote that they wanted all parties involved to be more conscious about what they were writing online for everyone to read.

In contrast to the other motivators for commenting, a small group of participants explained that they would comment to join in with the bullies because “it’s fun to participate in negative interactions.” These participants stated that because it was among a group of friends, the conversation was entertaining. These participants may have interpreted the interaction as teasing, although the nature of their brief comments does not clearly establish this possible interpretation.

Indecisive, Other response options, or miscellaneous motivators. Another group of participants stated that they were still “on the fence” about whether they would comment or not. They explained that they would consider other factors including their relationships with each of the commenters and if they were at the party where the events occurred. We felt that this observation was important to distinguish from other themes because it was an indication that contextual factors were influencing CB and bystander behavior.

Although some participants were still debating about how to react, many participants explicitly “recognized it was cyberbullying, wrong and/ or mean,” even if they chose not to comment or intervene on behalf of the victim. Other participants revealed that although they would not comment publicly on the status, they would prefer to “intervene offline” by texting, messaging, or privately communicating with the victim or bullies.

Lastly, expressing similar ideas regarding internet privacy, two final themes are: “Facebook is not the right forum” and “the victim (Jordan) should delete this status.” These participants expressed that the public nature of Facebook made both the conversation, and any participation in it, inappropriate. Furthermore, we inferred that some participants might have believed that the victim had some control of the situation and were attributing some responsibility to her when they stated that “the victim should delete the status.”

Discussion

As society’s social interactions move increasingly online, CB is an area of growing concern for individuals who utilize social networking frequently. In our sample of college students, Facebook use appears to remain prevalent, despite some media claims that it is “dying” among younger users (Bercovici, 2013). However, whether occurring on Facebook or through other media, such as Twitter, there are now a variety of means for individuals to engage in CB. Since previous research has mainly focused on bystander responses in digital venues such as online gaming sites and chat rooms where posting is done anonymously, it is worthwhile to separately explore bystander responses in distinct digital venues, including social networking sites, like Facebook, where the poster is identifiable.

The analysis of bystander behavior and motivation to a CB simulation in the current study revealed that although the majority (91%) of participants believed that bullying had occurred, fewer than half of the participants (Time 1: 31%; Time 2: 47%) reported that they would use a supportive intervention method (whether online comments or offline interventions) to offer support to the victim, which reflects a low bystander response rate to CB on Facebook. This level of response has been found in previous studies. For example, Li (2010) found that a majority of participants (70%) who claimed to have witnessed CB did not intervene or actively respond (Li, 2010). However, the bystander response rate in a naturalistic study of traditional bullying was 19% (Hawkins, Pepler, & Craig, 2001), which is significantly lower than the response rate in our study, indicating that individuals may be more likely to intervene online than in a face-to-face encounter. We speculate, with some evidence from previous research, that individuals may be more likely to intervene online than face-to-face because of the relative anonymity of typing a response, rather than verbally standing up for a victim (Tokunaga, 2010).

We also found that some bystanders preferred more indirect strategies of intervention (Time 1: 9%; Time 2: 10%), such as intervening offline/ in private or providing support for the victim, rather than directly defending the victim to the bullies. Although participants expressed that they would intervene offline or in private, unfortunately, we do not know how often participants would actually take these actions. In a live discussion study by Freis and Gurung (2013), the majority (90%) of participants tried to intervene in some way, yet 44% of participants still said “pass” at some point during the conversation, indicating their unwillingness to respond. Notably, of the posts in the Freis and Gurung study that involved intervention, only 3% utilized direct language; the majority involved changing the subject, which was not considered an intervention method in the current study (since we did not utilize a “live” response design, this category was not applicable). Future studies could build on our findings by including options for offline interventions and explore more specifically how and when bystanders intervene in this way.

Beyond examining the frequency and type of bystander intervention, we also explored the motivations for bystander behavior and the relationship between behavior, empathy and social identification with the bully versus victim. Asking participants to comment at two different points in the conversation allowed us to document ways in which their likelihood to respond and their view of the situation might shift as the intensity of the bullies’ comments increased. With regard to social identification, there was a significant shift from Time 1 to Time 2. Whereas most students (64%) identified with the bullies at Time 1, 83% identified with the victim at Time 2, when the bullies’ comments were at their meanest. These findings are notable, at least in part because nearly half (48%) of the participants identified that bullying began when the bullies were excluding the victim in the initial posts of the feed and by the time the bullies’ posts involved attacking the victim, an additional 20% of participants felt that bullying had occurred.

Despite this high level of acknowledgement that bullying was occurring, the majority felt that they related to the bullies, rather than the victim, at Time 1. Perhaps this is an indication of the frequency with which young adults engage in harmful posting through social media; it may also explain, at least in part, why only a minority of participants (28%) posted in support of the victim at this time point (Time 1). Analysis of participants’ empathy scores revealed no difference in empathy scores by social identification at Time 1, but as both social identification with the victim shifted by the end of the conversation (Time 2), so did the empathy scores of the bully vs. victim identification groups. Those participants who reported identification with the victim at Time 2 had significantly higher empathy scores than those who identified with the bullies. Our findings seem to point to a more nuanced understanding of the role of empathy in CB. In our simulation, which began with less severe bullying (exclusion), our participants’ identification with the bully could signal their comfort with or perhaps desensitization to that type of online interaction. As the bullying increased, those participants with greater empathy may have found themselves experiencing greater pity for the victim’s plight.

The designs of previous studies that have examined empathy and CB have differed from ours in the type of response that was required, thus making it difficult to compare their findings to ours. For example, Barlinska et al. (2013) examined whether or not individuals would continue spreading a CB message to other friends or delete the CB message, and found that when participants were induced with either cognitive or affective empathy, they were less likely to forward the CB in an aggressive response. Other studies (Freis & Gurung, 2013; Machackova et al., 2013) have found that individuals who respond with empathy may be more likely to intervene in a prosocial manner. However, our analysis of empathy by broad response categories did not find significant differences at either time point.

Our findings serve as a reminder that there are likely a variety of factors that interplay and influence the likelihood that a bystander will respond in CB. For example, the rationale that some participants gave for their inaction is characterized by responses that expressed “feeling helpless” or that an additional comment “would cause more trouble.” Interestingly, these bystander motivator themes overlapped with previously established themes of moral evaluating and intervention self-efficacy, which were identified in a qualitative analysis of traditional bullying (Thornberg et al., 2012). While the majority of participants in the current study identified the simulation as CB (“moral evaluating”), they did not believe that their intervention would produce a beneficial result (“intervention self-efficacy”). Several participants in our study openly acknowledged that they were “on the fence” about whether they would intervene or not, which could indicate that this internal debate was still transpiring. Similarly, Li (2010) determined that, whereas 45% reported that CB should be stopped, 47% of their respondents thought there was nothing that can be done about CB. Our results are also consistent with the ideas Hazler (1996) reported about the reasons that observers remain bystanders, including: they do not know what to do (similar to our theme of “feeling helpless”), they are fearful of becoming a target for the bullies (similar to several participants in our study that stated “I don’t want to risk getting made fun of as well”, within the “do not want to be involved” theme), and they do not want to cause additional problems (similar to our theme of “my comment would cause more trouble”). Self-efficacy continues to be an important aspect of bystander motivations, as indicated by multiple studies.

When Gini, Albiero, Benelli, and Altoe (2008) examined whether the constructs of empathy or social self-efficacy (i.e., the individual’s overall belief in his/ her competence and assertiveness in social situations) differentiated passive and defending bystander groups in bullying situations, they concluded that empathy did not differentiate between the two groups, but high social self-efficacy was associated with defending behavior by bystanders and low social self-efficacy was associated with passive behavior by bystanders. These findings demonstrate that it may be most important to examine how effective the bystander believes their intervention will be. Future research could examine ways to improve bystander’s social self-efficacy online, such as assertiveness training, to enhance response rates in CB.

While some participants expressed their unwillingness to respond because they didn’t think their comment would be effective, others indicated that they simply “did not want to get involved.” These themes are similar to the previously established motivations in the literature of moral evaluation (Thornberg et al., 2013) and evaluation of fairness (Desmet et al., 2012). Bullying may be considered unfair when the bully attacks factors that are out of the victim’s control (e.g., appearance, handicap, ethnicity), however bullying may be considered fair when a victim is blamed for his or her own behavior (Desmet et al., 2012). In our study, several participants explained that they found the conversation is “stupid, immature or unnecessary,” or that they were “against alcohol/ drinking/ partying.” These themes indicate that the participants chose not to comment because perhaps they believed it was partly the victim’s fault for choosing to engage in certain behaviors (i.e., drinking and partying as well as posting the status) and therefore, perhaps assessed that the behavior made the victim “fair game” for cyber-bullying. A related theme from our study was that the victim “should delete this status,” implying that the victim has some control over the situation, and should assume some responsibility for the malicious content of the conversation.

Previous literature also indicates that bystanders may not have wanted to comment because they did not want to be involved in what they consider to be “drama” (Allen, 2012). In a qualitative analysis of aggressive text messaging, Allen (2012) interviewed high school students and “drama” was a central theme they identified. They explained that “drama” implies that the relevance of the conflict is exaggerated and that extraneous people become involved in a trivial issue. Participants in the current study indicated multiple motivations similar to what Allen (2012) labeled as “drama”; some participants even directly used the term “drama” in their reason for not commenting, including themes where participants indicated not wanting to get involved (e.g. “avoid drama”); thinking the conversation is stupid, immature, or unnecessary (e.g. “petty and unproductive”); and believing that the additional comment would cause more trouble (e.g. “adds more drama”). We also determined bystander motivations in the middle ground response category related to “drama”, including claiming social media is not the correct forum for this behavior (e.g. “it's drama that doesn’t belong on the internet”) and indicating wishes to intervene offline (e.g. “I usually try to deal with things in person and off of the internet and social media. Posting said things is a recipe for disaster”). Future research should try to better understand how the notion of “drama” demotivates bystanders to intervene on behalf of the victim.

Other participants in the current study may have misjudged the situation and believed that the bullies were teasing or being funny, as explained by our motivator theme “It’s fun to participate in negative interactions”. In previous research, adolescents said teasing was distinct from CB because teasing was amongst friends and was not intended to cause harm (Desmet et al., 2012). If a participant perceived that the interaction was amongst friends, this may have motivated them to join in the conversation, similar to the social evaluating motivation identified by Thornberg et al. (2013). One participant in our study specifically stated, “since it’s close friends, it’s fun to mess around.” Furthermore, similar to the emotional reactions motivation identified by Thornberg et al. (2013), one bystander in our study stated, “it’s entertaining” as a reason for commenting. This may explain why a few individuals (Time 1: 2%, Time 2: 1%) actually “joined the bullies” in their comment. However, our CB simulation was most clearly not simply a case of teasing, especially when the victim specifically directed the bullies to stop when they made harassing comments. This finding indicates that although the majority of participants agreed that the simulation included CB at some point of the conversation, a sub-group of participants did not perceive it that way. Future efforts to reduce CB could include specific education about the differences between teasing and CB, and could extend this education to college-aged young adults.

By comparing our specific motivations in bystander behavior to previous studies in this area, we are able to reinforce specific themes that are consistent, as explained above. However, there are also a few unique motivator themes that were identified in the current study. One is that bystanders stated that “Facebook is not the right forum”, which may indicate their discomfort with seeing CB and/ or conflict in a public, identifiable venue. Similarly, participants stated that they believed that “Jordan (the victim) should delete this status”, and often even suggested this directly to the victim. Another unique motivation identified in the current study was that some bystanders would prefer to “intervene offline.” These motivations revolve around similar themes of internet behavior and privacy, and reflect that college-aged young adults are both judging others based on their online behavior and are also thinking about how they themselves are perceived by others online. Future studies should include these unique motivations in examinations of bystander behavior in CB as well as compare motivations across the context of different age groups.

Although the current study contributes to the contemporary knowledge about bystander behavior in CB, there are several limitations that should be considered and expanded upon for future studies. One limitation is that we were unable to associate bystander’s behavior (commenting or not commenting) with their motivations (their stated reasons) because of the exploratory nature of the study. Future studies could utilize the categories and motivations established in this study as a framework for more extensive quantitative research on the predictors of bystander behavior. Another limitation of our study design is that the participants did not personally know the victim or perpetrators, but only were asked to imagine that they did. Previous studies have indicated the bystander’s social relationship to the victim to be an important factor in their decision to intervene (Desmet et al., 2012).

Although the situation was created to be as realistic as possible, participants may have altered their behavior to present their ideal selves and ideal behavior, which may have resulted in an inflated response rate in our study, and therefore, perhaps there would be an even lower percentage of instances of bystander intervention in an actual CB situation. On the other hand, an alternate interpretation of our results could be that participants were not motivated to comment on the simulation because it was artificial and there was no possibility for spontaneous responding, as there would be in a real CB situation. Future studies could engage in natural observation of a CB scenario between friends or more closely simulating a live online conversation, and then asking questions about the motivation of the participants afterwards. Furthermore, the current study focused on multiple types of CB in an identifiable venue. In order to achieve a broader understanding of CB across its forms, future research could create CB scenarios that exclusively include only one type of CB (i.e. exclusion, flaming, harassment, cyberstalking, denigration, masquerade, outing, or trickery) as well as CB on anonymous forums such as Youtube, discussion boards, or online gaming networks (Li, 2010). A future goal would be to explore the prevention styles and bystander intervention strategies that work optimally for each type of CB.

Despite the current study’s limitations, it certainly adds to the current literature on bystander behavior by establishing a low response rate of young adult bystanders to CB on social-networking sites and identifying some of the possible motivations for their behavior. Whereas there is a multitude of research conducted with middle school and adolescent populations in the areas of both traditional and cyber-bullying, few studies have been conducted with young adults who are the most likely age-group to utilize social networking sites on a near-daily basis (Pempek et al., 2009). Clearly, additional work in this area, especially if conducted across diverse age groups, will be helpful in understanding how CB is experienced by both victims and bystanders. Researchers should continue to study and improve prevention and intervention methods for CB to create better social well-being for all users of the internet and technology.

References

Auerbach, C. F., & Silverstein, L. B. (2003). An introduction to coding and analysis: Qualitative data. New York City: New York University Press.

Barlinska, J., Szuster, A., & Winiewski, M. (2013). Cyberbullying among adolescent bystanders: Role of the communication medium, form of violence, and empathy. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 23, 37-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/casp.2137

Bercovici, J. (2013, October 30). Facebook admits its seen a drop in usage among teens. Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffbercovici/2013 /10/30/facebook-admits-its-seen-a-drop-in-usage-among teens/?&_suid=139519519461508640762534923851

Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 85.

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 113-126.

Desmet, A., Bastiaensens, S., Van Cleemput, K., Poels, K., Vandebosch, H., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2012). Mobilizing bystanders of cyber-bullying: An exploratory study into behavioural determinants of defending the victim. Annual Review of Cybertherapy and Telemedicine , 58-63.

Freis, S. D., & Gurung, R. A. (2013). A Facebook analysis of helping behavior in online bullying. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2, 11-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0030239

Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., & Altoe, G. (2008). Determinants of adolescents’ active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 93-105.

Hawkins, D., Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. M. (2001). Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Social Development, 10, 512-527.

Hazler, R. J. (1996). Breaking the cycle of violence: Interventions for bullying and victimization. Taylor & Francis.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, W. (2012). School climate 2.0: Reducing teen technology misuse by reshaping the environment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. (2013). Social influences on cyberbullying behaviors among middle and high school students. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 42, 711-722. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9902-4

Kalpidou, M., Costin, D., & Morris, J. (2011). The relationship between Facebook and the well-being of undergraduate college students. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14, 183-189.

Li, Q. (2010). Cyberbullying in high school: A study of students’ behaviors and beliefs about this new phenomenon. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma, 19, 372-392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10926771003788979

Machackova, H., Dedkova, L., Sevcikova, A., & Cerna, A. (2013). Bystanders’ support of cyberbullied schoolmates. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 23, 25-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/casp.2135

Menesini, E., Nocentini, A., Palladino, B., Frisen, A., Berne, S., Ortega-Ruiz, R., … & Smith, P. K. (2012). Cyberbullying definition among adolescents: A comparison across six European countries. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15, 455-463. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/cyber.2012.0040

Pempek, T. A., Yermolayeva, Y. A., & Calvert, S. L. (2009). College students' social networking experiences on Facebook. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30, 227-238.

Polyhonen, V., Juvonen, J., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). What does it take to stand up for the victim of bullying? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56, 142-163.

Schenk, A. M., & Fremouw, W. J. (2012). Prevalence, psychological impact, and coping of cyberbully victims among college students. Journal of School Violence, 11, 21-37.

Thornberg, R., Tenenbaum, L., Varjas, J., Meyers, K., Jungert, T., & Vanegas, G. (2012). Bystander motivation in bullying incidents: To intervene or not to intervene. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13, 247-252.

Tokunaga, R. S. (2010). Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 277-287. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014

Wang, C. C., & Wang, C. H. (2008). Helping others in online games: Prosocial behavior in cyberspace. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11, 344-346.

Wright, M. F., & Li, Y. (2011). The associations between young adults' face-to-face prosocial behaviors and their online prosocial behaviors. Computers in Human Behavior, 27, 1959-1962.

Appendix

Figure A1. Fictitious Facebook conversation separated into four parts, and within each part, the percentage of participants who indicated the bullying began at that section (N = 149).

Correspondence to:

Emily Shultz

Email: emily.shultz(at)nationwidechildrens.org