The culture and politics of Internet use among young people in Kuwait

Ildiko KaposiAbstract

Keywords: Internet; democratization; youth; Kuwait

Introduction

Recent years have seen a rise in scholarly and popular expectations of greater openness, freedom, and democracy brought about by new media in Middle East countries. Information and communication technologies (ICTs) supposedly enable a fragmentation and contestation of political and religious authority, enabling the development of a Muslim public sphere (Eickelman & Anderson, 2003). The developments are aided by the increasingly important role the internet plays in the socialization of the young, providing them with a sense of empowerment (Hofheinz, 2007). Unlike the often heavily controlled traditional media, the ‘virtual public sphere’ youth inhabit provides dynamic spaces for the exchange of ideas, interaction and debate, and it can serve as a place for political practices that challenge existing political power structures (Sreberny & Khiabany, 2010). The diffusion of technology is demonstrated to have had a causal role in democratization in Muslim countries, prompting the declaration that revolution in the Middle East will be digitized (Howard, 2010).

Howard’s claim was inspired by the wave of protests that erupted in Iran following the contested elections in 2009. Since then the world has witnessed the ‘Arab Spring’, routinely recorded in news media as a string of Facebook/Twitter/YouTube/Web 2.0 revolutions. These readings of the events lend new weight to optimistic beliefs about the inevitability of progress that technology brings. From this perspective, the internet as a ‘technology of freedom’ (Pool, 1983) that is democratic by nature is actively contributing to social change and the democratisation of public life.

While these narratives remain influential, technologies – I believe – can be most helpfully understood in terms of their affordances (Hutchby, 2001), a perspective that holds discourses important for making sense of technologies are important but proposes that possible interpretations of technologies are constrained by common-sense understandings of ordinary actors in everyday life. Affordances are the possibilities that objects offer for action, and the uses of objects are also material aspects of the thing as it is encountered in the course of action. Consequently, the ‘impact’ of technologies on social interaction can be best approached through an analytical focus on what people do with technologies in ordinary, everyday life. The ‘impact’ of the internet on society, culture and democracy can thus be understood by exploring what people do with/around/via it, including the discourses that surround new technologies. The internet is part of the fabric of everyday life for those who use it, and online experiences cannot be interpreted without the proper contextualisation of these in citizens’ lives.

Research Question and Method

I am going to focus on the role and meanings of the internet in the context of the Gulf Arab country of Kuwait. My research centers on youth and explores what role the internet plays in the lives of young people, and what ICTs mean for youth in Kuwait. The questions of what happens when young people engage with ICTs in their everyday lives, and what meanings and interpretations internet users construct for themselves about the complex relationships between society, culture, democracy and the internet, led me to an ethnographic approach. I followed ethnography as defined by Hammersley and Atkinson, for whom “The ethnographer participates, overtly or covertly, in people’s daily lives for an extended period of time, watching what happens, listening to what is said, asking questions; in fact collecting whatever data are available to throw light on the issues with which he or she is concerned” (Hammersley & Atkinson, 1990, p. 2).

Kuwait was chosen because of my familiarity with it, and the day-to-day contact I had with college youth in the country through my work at the American University of Kuwait. In addition to these advantages, Kuwait offers a unique context for exploring the dynamics of the internet and social change because of its mixed heritage of democratic and authoritarian rule, and the ongoing tensions of cultural openness and its narrowing (also referred to as Saudi Arabianisation) that shape contemporary life in Kuwait. Research data were collected from five years of observation, casual personal communications, informal interviews with youth, as well as a handful of semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted in Spring 2012 with students at the American University and Kuwait University. While the research cannot claim to rely on a representative sample of Kuwaiti youth, it did try to include a variety of perspectives due to the diversity of sources along gender and sectarian lines. Among the youth interviewed there were males and females, students from a private and a public university, citizens and non-citizen Arab residents of Kuwait, ultra-religious and openly liberal persons, Sunnis and Shiites. True to the qualitative research tradition, my interest was to explore the range of meanings young people construct around the internet, instead of making survey-based generalizations about the population of Kuwait. Nonetheless, the interpretations offered shed light on the different possible ways of understanding the internet and can contribute to our understanding of how local contexts and traditions continue to shape the meaning of new technologies.

In taking this approach the article also serves as a follow-up to Deborah Wheeler’s ethnographic research on the internet in Kuwait (Wheeler, 2006). The contexts of internet use have changed significantly since Wheeler’s fieldwork in the late 1990s, and the political, social, and above all technological developments justify revisiting the older research. Wheeler’s analysis and conclusions offer helpful starting points for comparison across time, to see how the shifting and changing Kuwaiti context and the changing technological scene may produce new constellations of internet–society relations in Kuwait.

Results

The Internet in Kuwait

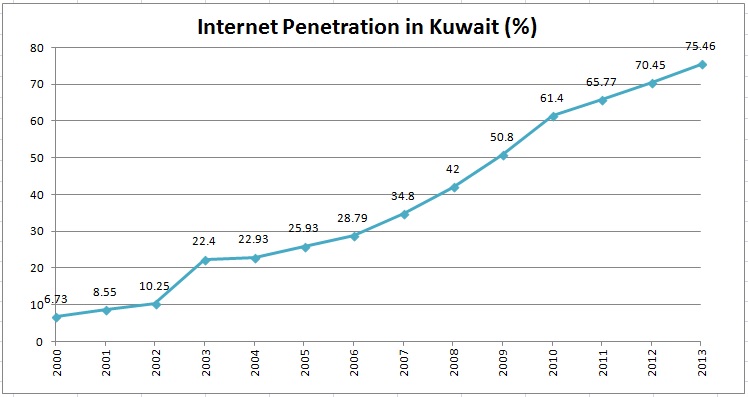

Writing about the diffusion of the internet in the Arab world, Khalil Rinnawi discusses the ambivalent attitudes that governments have towards the new technology. He sums up the situation as “schizophrenic” (Rinnawi, 2011, p. 123), meaning that while Arab governments covet the developmental advantages promised by the internet, they also try to restrain the development of the internet for fear of disruption to religious and political authority structures that the mass use of new technologies may bring about. In the end, the diffusion of the internet is the outcome of a series of on-going negotiations between governmental, business, religious, and popular considerations, and in this context it is potentially significant that Kuwait is unique among the Gulf Cooperation Countries in experimenting with its own, contradictory but genuine model of democracy (Tetreault, 2000). Among other influences this unique democratic tradition may have played a role in Kuwait being among the first Arab countries to link to the then-backbone of the internet, NSFNET, via its university in 1992. In 1997 Kuwait privatized its telecommunications sector to provide internet services (Rinnawi, 2011), and by 1998, a survey found that Kuwait had the highest per capita density of internet users in the Muslim world (Wheeler, 2006). The number of internet users continued to steadily grow in subsequent years, approaching 80 percent of the population by the end of 2013 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Internet penetration in Kuwait. Data source: International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

The growth in the number of internet users tells only one part of the story, though. While more and more people from Kuwait were going online, the internet itself underwent a transformation. The rise of Web 2.0 boosted expectations that the internet can realize its potential as a platform of participatory culture and free expression (O’Reilly & Battelle, 2009). Kuwait’s internet users quickly embraced Web 2.0, and the developing community of bloggers attracted the attention of the US embassy in 2005 when the Americans observed that bloggers represented “a growing population of highly educated, westernized Kuwaitis looking for an outlet for their energy and creativity” (“Kuwaiti Bloggers”, 2005). As more social networking sites came along, internet users from Kuwait were finding their way to them. The number of Facebook users in early 2011 was 795,100, a 22.82 percent penetration of the population (Arab Social Media Report, 2011). By December 2011 the number went up to 880,720, meaning that 80 percent of the then 1.1 million internet users in Kuwait were also on Facebook (Internet World Stats, 2012). Kuwait also had 113,000 Twitter users in March 2011, the Kuwaiti users were the top generators of tweets in the Arab world (Arab Social Media Report, 2011), and by March 2013 the number of users grew to 225,000 (Arab Social Media Report, 2013).

Social media use is aided by a high mobile phone penetration of 156 percent (Middle East Market Review, 2011). An increasingly high percentage of mobile phones are smartphones: between 2009 and 2011 smartphones came to account for 80 percent of the mobile phone market (“Smartphones in Kuwait”, 2011). Mobile has practically become synonymous with smartphone in Kuwait, to the extent that even public information campaigns about the dangers of messaging while driving will feature the latest models (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Billboard campaign against texting while driving, 2012.

Photo taken by author.

Smartphones made internet access mobile and truly ubiquitous. It is no exaggeration to claim that the internet is everywhere in Kuwait, a standard component of all facets of everyday life. In dealing with government, the media, or businesses, Kuwaitis will have access to institutions and services online. The internet is also an important venue for socializing, staying in touch with family and friends, making new friends, following celebrities, sharing ideas and gossip, finding information about anything ranging from recipes through health issues and beauty tips to current affairs, learning about what is going on in the country, finding out about news, checking out parliamentary candidates, and so on and so forth. Even prisoners feel like they must have internet access: in February 2012, local newspapers reported that an investigation was opened in the Central Jail when police discovered two internet routers installed and activated at two separate locations in the prison building, as well as 35 smartphones with Wi-Fi capabilities (“Five-Star Jail”, 2012).

The significance of the growing popularity of social media did not escape the attention of the state or the private sector. In what seems to offer a manifestation of government “schizophrenic” approach to new technologies, censorship in this realm of communication was intensified, while at the same time some key decision-makers were lauding the power of the internet: as Kuwait’s former minister of foreign affairs said in a public lecture, “It has long been recognized that the press is the ‘fourth branch’ of government. In today’s world, I think social networking is the ‘fifth branch’” (Al-Sabah, 2011).

Unlike the government’s mixed reactions, private corporations have shown little ambivalence in recognizing the potential of social media and have been harnessing its trends. It is symbolic of these developments that Social Media Day, an annual celebration of “the digital social revolution” is sponsored by Zain, one of the major telecom companies (Figure 3). Many of the most popular bloggers and microbloggers (known as social media influencers in the advertising industry) started selling advertising space and receiving payments for postings. The 2014 rate card prices for tweets and postings range between 200-800 Kuwaiti Dinars (GBP 410-1,660) on average but top bloggers can earn as much as 1,200 Kuwaiti Dinars (GBP 2,500) for a post or an appearance (Ghaliah Rate Card, 2014). There are well-publicised success stories circulating in public about Kuwaitis who have given up their day job to live off their earnings from blogging PR messages.

Figure 3. Social Media Day, 2012. Source: Jacqui

(http://www.couchavenue.com/2012/07/01/zain-celebrates-social-media-day/).

The commercialization of the internet and social media sits comfortably with Kuwaiti traditions that have valued business entrepreneurship highly since the pre-oil days when trade and commerce were the main sources of revenue for the community. The country’s new-found oil wealth, coupled with an excessive rentier welfare state system, has by now infused Kuwait’s culture with materialistic and consumerist values that permeate society. The question then is, what opportunities are left for critical communication in the virtual public sphere between increased government encroachment and the “corporate colonization of online attention” (Dahlberg, 2005).

The Internet in Their Own Words

Wheeler (2006) discusses young Kuwaitis’ attraction to all things fashionable and trendy as one of the reasons why new technologies would be adopted in the country. My research confirmed this: young Kuwaitis continue to be obsessed with the trendy and the cool. Even those who are otherwise very critical about Kuwaitis’ obsession with trends admit that the initial attraction of the internet for them had a lot to do with the need to fit in with the rest of Kuwaiti youth.

By now, the internet has become inextricably woven into the fabric of everyday life in Kuwait. Its integration into day-to-day existence goes beyond using technology as a tool for solving tasks, seeking information or making arrangements. It is an essential platform for sociability, similarly to youth elsewhere in the world (Lüders, 2011). ICTs have become a habit and a necessity for many, and the internet, accessed through smart phones, is a constant accompanying element even of family or social gatherings (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A weekly gathering of friends, October 2013.

The people in the picture were not research participants.

Photo courtesy of Alaa M. Hajar.

The young people I interviewed offer passionate declarations of their attachment to social media, the internet, and their smartphones, repeatedly referring to technology use as a habit, as essential to life as eating and drinking, a part of being normal. As Mohammad (22) summed up the relationship: “If it was up to me, I would live my life on the Internet.” Such strong attachment to the internet has provoked at least some concern among Kuwaiti researchers. A 2002-03 survey on internet use among Kuwait University students concluded that despite beneficial effects, the internet for some students is also a means of escape that undermines family and social life (Bastaki, Al-Nesafi, & Al-Obaid, 2004). As 83.4 percent of respondents claimed feeling miserable when refraining from internet use, the same study also concluded that a high proportion of students developed some form of internet addiction. Similarly, the need to map this perceived threat inspired another survey, also conducted among Kuwait University students, that aimed to find out about students’ perceptions of internet addiction (Hamade, 2009). This survey concluded that only a small number of students were addicted to the internet, while the rest demonstrated the ability to distinguish between useful and dangerous uses of the technology.

The pathologisation of internet use implied in these surveys is, I believe, a mistake and additionally, it may position academic research as supportive of establishment policing the country’s youth. Nonetheless, both surveys and my ethnographic approach arrived at the conclusion, namely that the internet is irresistible and possesses a magnetic quality for young people in Kuwait. A recurring theme in my communications with young Kuwaitis is their readiness to use the language of psychopathology in explaining what the internet means for them. But the object of pathologisation is reversed in these accounts: it is not the internet, rather Kuwaiti society that is seen to be detrimental to one’s psychological and intellectual development. There is immense pressure on young people to guard their reputation by obeying social and cultural rules that often seem arcane to them, as well as discriminatory, especially against women. Students like Hamad (21) provide an incisive analysis of hypocrisy, oppression, suppression, and frustration that frame the existence of Kuwaiti youth, especially if they are unconventional: “People are just oppressed, specifically women, they’re just oppressed. They want to say what they think or be what they want to be, but they can’t”. The internet offers a way out of what young people feel to be a stifling, suffocating social, cultural, and political environment. Indeed, therapy and therapeutic are terms they frequently associate with their online activities. Kuwaiti youth feel as if they could be their “true selves” online, able to express themselves and speak their mind without fear of social recrimination. The two areas where freedom is most felt online would be politics and sex, with religion mixed into these as it often is in the Islamic countries of the Gulf. For the purposes of analysis I am going to discuss these separately, although sexuality in the shape of body politics is also a politically relevant arena.

Sex and the City-State: Private Sins, Public Mores

Much of the frustration felt by young people concerns sexuality, which is hardly surprising given their age group pitted against the uncompromising social control mechanisms that are in place to regulate the human body. Wheeler (2006) found that the biggest attraction of the internet for youth were the opportunities to circumvent conservative social norms and allow young people of the opposite sex to meet, communicate, socialize, flirt, build relationships, and even find a marriage partner online without the restrictions of societal and parental supervision. By 2014 these socio-culturally unorthodox practices have become more and more common, and lost much of their shock value compared to the 1990s. The normalisation of these practices has begun to occur offline as well, as summarized by Fatima (25): “Today I think Kuwait is more open, guys and girls can meet up and be friends. The internet’s not such a big deal because people can just meet outside and can talk like normal human beings”.

This would read as a success story – the internet brings about greater personal freedoms and hence helps society learn to tolerate male-female interactions. At the same time, however, gender segregation (and its subversion and evasion) remains a salient political issue in Kuwait, particularly as it continues to be advocated by the representatives of religious conservative ideologies in public life. But on the internet, segregation is impossible to enforce. It remains a matter of personal choice whether and to what extent young people decide to engage in conversations with members of the opposite sex. The option of anonymity in the online world affords a seemingly risk-free experimentation with broadening one’s circle of acquaintances and friends, as well as a relatively safe environment where the opposite sex can be explored, at least discursively. In Wheeler’s (2006) interpretation such practices of exploring the other may actually be beneficial in preparing young Kuwaitis for communication and understanding between the sexes in marriage. Online explorations can – in the longer run – contribute to maintaining the institution of marriage that is seen as a fundamental building block of society, as well as a religious requirement.

Nevertheless, from conservative religious perspectives relationships developed and played out on the internet are objectionable. As one of my interviewees, a devout Salafi Muslim young man commented on this issue: “Rather than disobey Allah, they should get married. And marriage is half the religion.” Islamic discourses on the subject are circulating widely in society, and the thinking of even those young people who live by different principles incorporates an awareness of conservative religious approaches that are all the more powerful because they inform legislation on sexual matters. As in pre-Enlightenment European societies (Dabhoiwala, 2012), sexuality is a public preoccupation, not an individual and private issue in the Gulf. The socioeconomic structures of these countries revolve around kinship that dominates every facet of life (Alsharekh, 2007). The extended family is all-important, preserving premodern (and pre-Islamic) unwritten tribal rules and customs. The traditional features of tribal organisations include a system of shame and honour that is tied to women’s behaviour, and these concerns inform the laws intended to uphold the honour and property rights of fathers, husbands, and higher-status groups. The workings of sexual policing are symbolic of the central values of traditional culture, and sexual practices deemed deviant remain punishable by law. Cross-dressing, adultery and prostitution are illegal in Kuwait, as are consensual pre-marital sexual relations or bearing a child out of wedlock, any of which can result in a prison sentence.

When it comes to the public representations of sexual matters the boundaries of legal acceptability are firmly drawn by the state to exclude nudity and explicitly sexual materials. Pornography is banned in Kuwait, and internet service providers block all websites with pornographic or sexual content. Based on my communications with young Kuwaitis, they by and large seem to accept the censoring of pornographic material. This finding is consistent with a 2008 study written by two Kuwaiti researchers who conducted a survey on how Kuwait University students deal with pornography (Abbas & Fadhli, 2008). Abbas and Fadhli concluded that on the issue of pornography their sample “almost unanimously prefers being conservative rather than liberal; they support censorship of pornography” (Abbas & Fadhli, 2008, p. 31) due to the students’ Islamic background. The survey results confirm that sexual policing is an integral part of society, not an external imposition; it is brought to life by popular participation in community self-policing to uphold collective standards of behaviour.

Despite strict censorship laws, it is relatively easy to be exposed to pornography online. Most recently, the popularity of the hashtag #kuwait made it a target for pornographers who flooded Twitter with sexual images, there to see for anyone who searched for the country name (Khaled, 2014). Besides accidental exposure, youth also tend to have the technological skills to circumvent the navigational problems posed by website blocking, and if they want to access forbidden content, they will use proxy servers or other means to do so. As a result, pornography can continue to be one of the internet’s attractions for youth. As Dana (20), who has strong feminist views, explained: “Isn’t it obvious [what attracts young people in Kuwait to the internet]? Porn, all the way. Especially the guys, they’re addicted. In such a patriarchal society, in a society of meat eaters, they tend to be addicted to porn.”

Young Kuwaitis can easily become consumers of pornographic products circulated and reproduced online from print or video. To my knowledge, they are much less likely to take advantage of Web 2.0 as a platform of participatory culture and free expression in the sense of producing and sharing their own sexually explicit material. Nonetheless, there exists a subculture of Kuwaiti users who do approach social networking in a sexually explicit way. In 2012-13, several young Kuwaiti men showed me accounts on different social networking sites where the user’s profile picture was sexually suggestive, semi-nude or nude, accompanied by sexually suggestive or explicit self-descriptions. The purpose of the accounts was clearly to find sex partners or to sell sexual services. Given Kuwait’s climate of strict public mores, users who engage in such self-presentation practices online take a major risk. They do try to protect themselves by hiding their identity behind anonymous/false name accounts and filtering the people who could contact them. But even in the absence of users’ clearly established individual identities, the estimated two to three hundred people who constitute this circle highlight a sexual subculture whose existence had been an anathema to public culture. Eventually, these visible subcultures caught the eye of the authorities, and by 2014 news media were reporting on police crackdowns on websites and social media accounts dedicated to prostitution and “indecent activities” (Al-Arbash, 2014; “Steps Taken”, 2014).

In making this subculture visible, the internet is contributing to a broadening of the range of ideas that surface and move into a more public domain. The virtuality of these naked bodies and the saucy messages they emit could be interpreted as risqué forms of identity performances afforded by the internet where the body is released from the confines of traditional shapes, genders or boundaries. Yet, as Slater (1998) found in his research on trading sexpics on Internet Relay Chat, the parties to the seemingly limitless transgressions do not approach sexual expression online forms of deconstructive and utopian possibilities of identity play. Instead, they try to connect and fix bodies and identities and continue to search for authentication by attempting to “fix the other in a body or body-like presence, one which persists over time and is locatable in space” (Slater, 1998, p. 92). In the case of Kuwaiti sexual avatars and messages, locating the users in Kuwait is possible if they ask for phone credit top-ups from those who show an interest. More subtle anchors fixing user identities to the space of Kuwait would include language (the Kuwaiti dialect) and flying the Kuwaiti flag in users’ posts. To the discerning eye, the quality of the avatar pictures also serves as a way of authenticating the user behind: pictures that are too perfect (i.e. their resolution is too perfect) are probably fake, while photos of lower quality taken with a camera phone signal that it is probably the actual person posing for them. A “real” body without the face visible and posing under a false name is as far as many Kuwaiti online sexual transgressors may go. Even so, the experience of shedding fixed identities and immersing oneself in a closed circle of limitless transgression and uncertainty about the other’s identity can have a profound and lasting impact. One of my 21-year-old interviewees described his excursion into the sexual scene on Twitter as a vertiginously liberating experience despite the ethical hang-ups he felt about talking from behind a cloak of anonymity: “You’re lured by these pictures, by these words, by these actions, you’re just lured into it. I started feeling like I was losing myself. I was getting addicted to it. I was adding more people. I was attracted to these naked pictures. Just adding, and adding, and adding and trying to get to talk to these people. I felt like a predator, I felt really bad; it felt wrong. But in a way, it made me feel a bit liberated, because I can tweet what I want, how I want, and people can read it and they won’t know who I am. Even as a guy, as an adult, I felt a bit liberated because I can tweet whatever I want.”

It is a heady concoction to experience in Kuwait. Sexual taboos are being challenged and knocked down on the internet by young Kuwaitis every day, and that experience is formative even if, as Bataille reminds us, allure is bound up with disgust in matters of transgression (Fuchs, 2009). But would the liberating experience afforded by sexual transgressions be also felt in other spheres like politics, political in the sense of oriented towards the institutions of decision-making? It is political speech that I turn to in the next section.

Political Speech: Red Lines in the Sand?

Kuwaiti media are known as the freest among Gulf countries. In 2009, the International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX) stated the country “ranks high in regional classifications for its relative media freedoms” (IREX, 2009), Freedom House has listed Kuwaiti media as “partly free” each year since 2007, while Rugh (2004) classified the Kuwaiti press as “diverse print media” due to the clear differences that exist between newspapers in terms of political orientation and style. However, even the relatively favourable characterizations of the country’s media highlight the red lines that public expression in Kuwait must not cross. Some of the limitations on free speech arise from the Constitution which, while granting freedom of speech and expression, also prohibits criticism of the Amir – the ruler of Kuwait – or Islam and generally relies on caveats of not transgressing tradition, law or public morals when it mentions the exercise of rights and freedoms.

The limits of acceptable public speech are enforced through censorship that extends to the internet. As discussed above, censorship has targeted pornographic websites, but political speech is also expected to remain within the limits marked out by legal red lines. In Kuwait, the free expression of ideas online led to arrests of bloggers and Twitter users for alleged libel, attacking national unity, defaming the prime minister, insulting and attacking the status of the Amir, threatening national security by publishing disapproval of the Bahraini and Saudi ruling families, support of the Islamic State of Iraq, blasphemy, defaming the Islamic faith and slandering the Prophet Mohammad. While the bloggers and tweeps have usually been released soon after they were taken into custody, or they would receive an Amiri pardon, the news of the arrests reverberate around the internet (as well as in traditional media) and may serve as a deterrent to others who consider voicing critical opinions about forbidden subjects.

Despite the arrests and crackdowns, young people in Kuwait continue to view the internet as a domain of freer expression. They will be free and critical in arguing their points in online political discussions where researchers in 2006 found the topics to be focused on local issues ranging from members of Parliament, elections, and the economy to religion (Nashmi, Cleary, Molleda, & McAdams, 2010). The vigor – if not the rigor – of online political discussions is also helped by the way in which public figures, such as candidates at election time, MPs, or public intellectuals, use the internet to spread their views, attack opponents, and settle ideological scores. As Herman acknowledges, “there are often differences within the elite that open up space for some debate and even occasional (but very rare) attacks on the intent, as well as the tactical means of achieving elite ends” (Herman, 2000, p. 103). Political debates about both the intent and the means of achieving elite ends have not been contained within Kuwait’s ruling family or Parliament, they overflow and take over newspapers, television stations, and the internet. The Kuwaiti public benefits from the ongoing lack of elite consensus because the differences among elites make it difficult for a united propaganda machine to control public debate. When it serves their interests and agendas, political figures will champion free speech and democracy, as in the case when opposition MPs condemned the 2011 arrest of Kuwaiti Twitter users accused of insulting the Amir. The MPs talked about the then-prime minister using the Ministry of Interior to implement a “repressive policing ideology” and “double standards”, “gagging” activists, and attempting to “transform Kuwait into a ‘police state’” (Sharaf, 2011), and their statements were widely reported in the media.

Voicing criticisms about top political authority figures – including the Amir and the ruling family – is neither a new phenomenon nor exclusive to the internet in Kuwait, but traditionally the criticisms tended to be aired in the protected private spaces of the home, a gathering of friends and relatives (diwaniya), or in a circle of trusted colleagues at work. While the internet has not created the critical voices, it now affords an additional platform for making these heard by large audiences. By the account of the young people I interviewed, all the red lines have been crossed online: they share stories about coming across comments that are critical of the Amir of Kuwait to the point of cursing him. Even more telling, they say, is the number of likes added to the curses. Neither do many young people see unlimited freedom online as a bad thing, rather as a phenomenon to be experienced and shared with others, including older generations.

Nonetheless, young Kuwaitis are aware of the risks involved in sharing their political views. Many of them are wary of talking politics or religion in public (including on social media) because of concerns that it can land them in trouble such as physical attacks from the groups offended, or even imprisonment. As Fatima (25) said, “I’m not 100% free; I’m not completely totally free to express my opinions. I only post the things I know are not going to cause me any trouble”. Her caution and self-censorship were echoed by others who claimed to be political in the sense of taking an active interest in public affairs and social issues, but at the same time maintained the need to be careful about what they write online.

The expression of thoughts and opinions is shaped by the ingrained cultural codes of knowing where to say what, creating a compartmentalized free speech whose boundaries are dictated by the perceived audiences of the discussion and the public/private nature of the online venue where the opinions are expressed. The more private a venue, with the more select and carefully screened audience, the greater freedom young people have for self-expression, and the most important mechanism they use for developing the platforms of free speech is seeking out like-minded individuals. In front of an audience whose members share their views it becomes easy and self-affirming to discuss any subject they are concerned with. Identities are confirmed and validated among like-minded people, and the members of online groups can feel a sense of belonging they are often not granted by the traditional social structures in their daily life. The experience can be similar to how political activism and social movements work, by maintaining protected enclaves where ideas and everyday talk that challenge and help change conventional assumptions can brew (Mansbridge, 1999).

However, democratic politics needs public debates, a clash of views played out in front of the polity in order to find solutions acceptable to all. It is through public discussion that new ideas can be picked up, tried, adopted or dropped, filtering out and discarding the worst ideas on public matters, and applying the best ones. This would require going public, broadening the audience for critiques and views articulated in the protected enclaves of like-minded people. Moving into more public arenas of political speech would also involve the toning down of the excesses of activist discourses, necessarily translating political messages so that others would deem acceptable, or at least worthy of discussion. Many young people, however, perceive the social costs of going public with their political opinions high, to the point of being prohibitive. The internet, and social media in particular, may be acting as an incubator for activism, but existing social and cultural norms continue to thwart the transition of online political activist discussions into offline action.

There are some promising signs. Several of the young people I interviewed were encouraged by their experiences with free political expression online to become active in organisations advocating social and political agendas. Some joined the Kuwaiti Human Rights Society and attended rallies that were held to highlight the plight of minority populations. Others have taken advantage of social media to open direct lines of communication with MPs, messaging them with their concerns. Yet others experiment with political self-expression through art, or they dedicate their academic work like Master’s theses to studying and highlighting contentious issues of gender, Islamic feminism, or minority rights. At the same time, there is also widespread apathy among youth, and an acute awareness among the politically minded that actions online can have serious consequences.

Government crackdowns and lawsuits are one source of perceived threats to free speech. Even more salient perhaps is community policing whose logic can extend to the internet, and whose main source is the family. The primacy of kinship in Gulf societies means that a person’s actions would not be judged with reference to the individual exclusively, rather the way youth conduct themselves reflects back on their entire (extended) family. Young women especially can feel like being watched by a thousand eyes, and conduct deemed inappropriate will eventually be reported back to the their families. Even outspoken youth acknowledge that the emotional dynamic is different when criticism of their views comes from “blood relatives”, and they begin to be careful with what they write online once family members and acquaintances start to appear on a platform of hitherto free expression. As Maryam (22) explained, “I love Twitter. But now I’m starting to be careful with what I write, because of family and people I know start to be there. It’s really hard sometimes to post my real opinion because these people are really conservative and I’m more open. It’s not good to add your relatives, they check who’s following you, etc.”

The massive popularity of the internet and social media is thus working against free speech by also installing a system of online participatory surveillance that relies on gossip and rumours as tools of community policing. These currents of influence are a reminder of how porous the boundaries between online and offline worlds can be. In anticipating the flow of influence from the online worlds to the offline political contexts, counterflows of offline social norms to the internet are easy to overlook. The users of new “technologies of freedom” remain embedded in their society, and society’s influence can be traced both ways.

Conclusion

In a way, the problem of analyzing the role of the mutual shaping of online and offline worlds in Kuwait seems to involve uncertainties around which Kuwait we are to consider. For below the surface of official state and society, there exists another, or indeed several other Kuwaits that do not operate under the same public norms and mores, and are in fact articulating themselves in opposition to the country’s increasingly fragile public image. If the Amir is seen as a symbol of national unity, and in this sense is the body that holds the state together, then the verbal treatment meted out to him online is indicative of the disparity between the surface and its alternatives. It is online that popular discontent with the state of the nation is freely bubbling to the surface, and in tandem with the existing fora of political speech such as the Parliament and media, it may well end up influencing the politics of the country.

While Kuwait has not joined the wave of democratization signaled by the Arab Spring, there is considerable political and social turmoil detectable in the tiny emirate. The turmoil is, for the most part, contained within the framework of Kuwait’s indigenous democratic institutions, but the lines that used to clearly delineate the acceptable public norms of social, cultural, and political speech and action are proving to be increasingly blurred. One factor in the crossing of the lines is the influence new media technologies have on Kuwaiti society, especially on youth. Since young people make up the majority of the country’s population, their uses of the internet and experiences online can have a gradually unfolding impact on public life in Kuwait in the longer run.

While historically Kuwait City as a free port has been necessarily open to the influences of other cultures, the internet is now contributing to the further opening up of Kuwaiti society. As a global network, it offers Kuwaitis new opportunities for engaging in conversations with people from around the world, as well as allowing them access to cultures, services, and products from elsewhere. The open communication structures afforded by the internet get used for communicating internally, too. Kuwaitis are continuously pushing the boundaries of admissibility in terms of speech and action online. In this sense the internet does seem to serve as a technology of freedom, allowing experimentation with identity, sexuality, and political speech previously unseen in public or semi-public forums. However, social, cultural, and political traditions continue to significantly shape young people’s uses of the internet in Kuwait.

Whether the internet, itself an excellent ground for brewing enclaves of like-minded groups and encouraging deliberations and political activism, can enable collective action offline remains to be seen. In political terms, the main significance of online engagement can be the low-level but regular political experience it offers participants. Even if the immediate impact remains altogether muffled and limited, new media provide a social space where the social and cultural identities of young citizens can be constantly reformulated and reshaped.

The next chapters in the history of Kuwaiti democracy cannot be written without taking into account the contributions of ICTs. But the processes of democratization, eagerly anticipated and predicted in the literature about internet use in the Middle East, unfold incrementally. It is necessary therefore to continue exploring the ways new media affordances are incorporated into specific social, political, and cultural contexts over longer periods of time. This study was based on an ethnographic approach, which enabled the in-depth exploration of the subject on a particular segment of Kuwaiti society. A clear limitation of this methodological choice was that the sample of youth accessible to the researcher was biased in favour of English-speaking university students, who are likely to be more exposed to non-traditional ways of thinking. Further research would benefit from a survey-based, quantitative approach that would enable us to see the extent to which the patterns found can be generalized to the population of Kuwait.

References

Abbas, H. A., & Fadhli, M. S. (2008). The ethical dilemmas of Internet pornography in the State of Kuwait. SIGCAS Computers and Society, 38(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1413872.1413877

Al-Arbash, F. (2014, April 16). Instagram and prostitutes! Kuwait Times, p. 3.

Al-Sabah, M. (2011, October 6). Kuwait: Bridging the gaps. A nation’s destiny. Perugia, Italy. Retrieved from: http://drmalsabah.com/index.php/lectures/kuwait-bridging-the-gaps-a-nation-s-destiny/

Alsharekh, A. (2007). The Gulf family. Kinship policies and modernity. London: SAQI.

Bastaki, Q., Al-Nesafi, S., & Al-Obaid, T. (2004). Internet use among Kuwait University students. Abstracts of Community Health Projects Conducted by Medical Students at the Kuwait University – Academic year 2002-2003.

Dabhoiwala, F. (2012). The origins of sex. London: Penguin.

Dahlberg, L. (2005). The corporate colonization of online attention and the marginalization of critical communication? Journal of Communication Inquiry, 29, 160-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0196859904272745

Dubai School of Government (2011). Arab Social Media Report, 1(2). Retrieved from: http://www.arabsocialmediareport.com/UserManagement/PDF/ASMR%20Report%202.pdf

Dubai School of Government (2013). Arab Social Media Report (5th Ed.). Retrieved from: http://www.arabsocialmediareport.com/UserManagement/PDF/ASMR_5_Report_Final.pdf

Eickelman, D. F., & Anderson, J. W. (2003). New media in the Muslim world. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Five-star jail. (2012, February 19). Kuwait Times, p. 6.

Fuchs, R. (2009). Taboos and transgressions: Georges Bataille on eroticism and death. Gnosis, 10(3).

Ghaliah digital communication agency rate card (2014). Retrieved from: http://www.ghaliah.com/r/ratecardFiles/14041244924-GtechRateCard.pdf

Hamade, S. (2009). Internet addiction among university students in Kuwait. Digest of Middle East Studies, 18, 4-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1949-3606.2009.tb01101.x

Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (1990). Ethnography. Principles in practice. London and New York: Routledge.

Herman, E. S. (2000). The propaganda model: A retrospective. Journalism Studies, 1, 101-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/146167000361195

Hofheinz, A. (2007). Arab Internet use: Popular trends and public impact. In N. Sakr (Ed.), Arab media and political renewal (pp. 56-79). London: I.B. Tauris.

Howard, P. N. (2010). The digital origins of dictatorship and democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hutchby, I. (2001). Conversation and technology. Cambridge: Polity.

Internet World Stats (2012). Internet usage in the Middle East. Retrieved from: http://www.internetworldstats.com/middle.htm#kw

IREX (2009). Kuwait media sustainability index. Retrieved from: http://www.irex.org/resource/kuwait-media-sustainability-index-msi

Khaled, B. (2014, June 26). X-rated pics hog #Kuwait on Twitter. Kuwait Times. Retrieved from: http://news.kuwaittimes.net/x-rated-pics-hog-kuwait-twitter/

Kuwaiti bloggers: Voices of the future. (2005). Wikileaks. Retrieved from: http://wikileaks.org/cable/2005/02/05KUWAIT514.html#

Lüders, M. (2011). Why and how online sociability became part and parcel of teenage life. In M. Consalvo & C. Ess (Eds.), The handbook of Internet studies (pp. 452-468). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Mansbridge, J. (1999). Everyday talk in the deliberative system. In S. Macedo (Ed.), Deliberative politics. Essays on democracy and disagreement (pp. 211-240). New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Middle East market review. (2011, November). Retrieved from: http://content.yudu.com/Library/A1vbl1/MiddleEastMarketRevi/resources/index.htm?referrerUrl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.telecoms.com%2F38599%2Fmiddle-east-market-review-2011%2F

Nashmi, E., Cleary, J., Molleda, J., & McAdams, M. (2010). Internet political discussions in the Arab world: A look at online forums from Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Jordan. The International Communication Gazette, 72, 719-738. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1748048510380810

O’Reilly, T., & Battelle, J. (2009). Web squared: Web 2.0 five years on. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1357034X98004004005

‚Smartphones‘ in Kuwait take up 80 pct of market (2011, July 14). The Arab Times. Retrieved from: http://www.arabtimesonline.com/NewsDetails/tabid/96/smid/414/ArticleID/171460/reftab/36/Default.aspx

Sreberny, A., & Khiabany, G. (2010). Blogistan. The Internet and politics in Iran. London: I.B. Tauris.

Steps taken to shut down almost 300 immoral sites: Online prostitution by Arab, Asian women widespread (2014, April 10). Arab Times, p. 2.

Tetreault, M. A. (2000). Stories of democracy. Politics and society in contemporary Kuwait. New York: Columbia University Press.

Wheeler, D. L. (2006). The Internet in the Middle East. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Correspondence to:

Ildiko Kaposi

Department of Media

University of Chester

Parkgate Road, Chester

CH1 4BJ

Email: i.kaposi(at)chester.ac.uk