The privacy implications of online bonding, bridging and boundary crossing: An experimental study using emoticons in a social network map

Xiaoyi Guan1, Mary Tate2Abstract

Keywords: Privacy, social capital, social network sites, visualization, experiment

Introduction

Social network sites (SNS) are a “phenomenon” of the last decade, occupying a large proportion of time spent online (Smith, 2009), and potentially changing the way we live, work, and interact. Although the landscape of social network sites is diversifying, and “niche” sites are establishing large user bases around a specific function (for example LinkedIn specialises in professional connections), most social network sites have features in common. Most provide the ability to: present oneself (a “profile”) for others to peruse; regularly share and update information (“status”); and contact and search for people, sometimes for specific purposes such as professional recommendations or shared interests.

Associated with the growth of participation in online social networks, and the proliferation of different networks for different purposes, has been an increase in “boundary crossing”, where existing members of disparate networks overlap. This has a number of important implications for how people manage these relationships, what information they disclose, and to whom. For example, colleagues, managers and clients might already belong to an individual’s professional networks. What issues arise when they also join socially-oriented networks? Is it rude or career-limiting to refuse to “friend” a superior, a client, or a family member? Does boundary-crossing in online social networks affect what people will disclose online?

In this experimental study, we investigated the privacy implications and willingness of members to share information about their feelings and emotional state online with other people who are members of different, but inter-connected, offline networks, with differing levels intimacy. We began with a set of friends with close emotional ties, and then, over the course of the experiment, added additional members with weaker ties, and finally, added a professional contact in a senior position.

In the rest of this paper we first offer a brief literature review of online social networks, social capital, and privacy and boundary crossing; we then describe the research design and our results; followed by a discussion and conclusion.

Literature Review

Social networks and social networking sites

Behaviour and interaction in social networking sites is often studied using a social network lens. Social ties between people connected in social networks have traditionally been described as a combination of time, emotional intensity, mutual confiding (intimacy) and reciprocal services, and can be characterised as “strong”, “weak”, or “absent” (Granvotter, 1973).

It has been suggested that online social network sites such as Facebook “flatten” social networks. Rather than maintaining membership of a diversity of networks, including work, family, and social connections, online social networks reduce this complexity to a binary “friend or not” (boyd, 2003). Many people are prepared to accept as “friends” anyone they are acquainted with, even if they don’t know the person particularly well or trust them (Gross & Aquisti, 2005). The nature and strength of social ties may not be adequately represented in online connections. The nuances of different offline social networks are reflected in differing degrees of trust and intimacy (Gerstein, 1984). Participants may choose to share private information with people in some offline social networks but not others (Gerstein, 1984); while in online social networks, information that has been shared may be available to a large number of friends, acquaintances, even strangers (Gross & Aquisti, 2005), or colleagues and potential employers (Dominion_Post_newspaper, 2012; Rosenblum, 2007). Increasingly privacy settings are more granular and can be applied to (for example) status updates and photo albums. Nevertheless, the replicable and persistent properties of digital information on SNS make all information shared by an individual, including that originally disclosed in a “private” setting, a potential privacy risk (boyd, 2007).

There have been a range of opinions concerning the impact of sharing information online with a large, “flat” social network on privacy and relationships. Some researchers have highlighted potentially negative effects of online social networks, including using virtual intimacy that allows people to “log off” to avoid the complexities of real intimacy (Rosenblum, 2007). However the impact of online networks on relationships is not always negative. It has been suggested that people can use social networking sites to maintain and strengthen “weak ties” with colleagues they are not already close to, and in some cases, leveraging these online contacts into closer offline bonds (DiMicco et al., 2008). Other researchers have acknowledged the complexities that arise from intersecting online and offline social networks; suggesting that issues arise from “boundary crossing” where people participate in multiple online social networks with different functions (such as the mainly social focus of Facebook, and the mainly professional focus of LinkedIn) (Skeels & Grundin, 2009). Overall, “It remains to be investigated how similar or different are the mental models people apply to personal information revelation within a traditional network of friends compared to those that are applied in an online network“ (Gross & Aquisti, 2005, p. 73).

Social Capital

Social capital can be considered as the collective value of all connections (strong and weak ties) among and within social networks, and is built on patterns of behaviour, information exchange, trust, and reciprocity within social networks (Putnam, 1995). Participation in SNS may increase one’s social capital (Ellison, Heino, & Gibbs, 2006). In Putnam’s (2000) study, he referred to bonding social capital as “tightly-knit” relations between individuals in emotionally close relationships, such as family and close friends. Bonding social capital is built on strong ties involving intimacy between individuals (Parks, 2009). As Putnam (2000) saw it, bridging social capital refers to the loose connections between individuals who may provide useful information or new perspectives for one another, but typically not emotional support. Bridging social capital relates to social ties between individuals with weaker ties (Parks, 2009).

The use of SNS is theorized to increase bridging social capital by facilitating the development of weak and diverse ties (Donath & boyd, 2004). SNS may be appropriate for bridging social capital, because low level relationships can be maintained with relatively little time or energy (Donath & boyd, 2004), and the technology to maintain bridging social capital is becoming cheaper and easier (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007). The design of Facebook use can help users accumulate and maintain bridging social capital, because it facilitates the easy maintenance of weak ties (Ellison et al., 2007).

Latent ties are social links that are technically possible but not usually activated socially (Haythornthwaite, 2005). Facebook supports latent ties, because it makes one’s connections visible to a wide range of individuals, and enables network members to identify those who might be useful in some capacity (and therefore activated into a weak tie). In a study within a single organization, an SNS (limited to employees of the enterprise) was found to have little impact on the relationships between employees that already considered themselves to have strong ties, but was found to assist in building bridging social capital based on latent ties, by assisting previously unconnected individuals with similar personal and professional interests to find each other (DiMicco et al., 2008). In some cases, participation in the workplace SNS also contributed to building stronger bonds and emotional intimacy between participants who had previously not known each other (DiMicco et al., 2008)

Boundary crossing relationships are defined as that sub-set of weak or latent ties where inherent tensions exist “from mixing personal and professional personas, lack of delineation of hierarchy, status, or power boundaries, and the risk of inappropriate communication [that arises]” (Skeels & Grundin, 2009, p. 6). By contrast, with studies that identified advantages for the use of SNSs in the workplace, perceived issues and risks arising from boundary crossing relationships on SNS have been found to cause anxiety (Skeels & Grundin, 2009).

Privacy

Closely related to the issue of social ties and social capital is the notion of privacy. Privacy is a widely debated concept with a long provenance. In our study, we use the seminal definition by Warren & Brandeis (1890), who define privacy as the right of “all persons whatsoever their position or station, from having matters which they may properly prefer to keep private, made public against their will’ (pp. 214-215). Although this definition is over one hundred years old, it is still relevant. The original need for privacy protection in law arose in response to a similar phenomenon to the one we are currently investigating: the ability for personal information (especially in the form of photographs), to be disseminated in popular media without the consent or knowledge of the individual.

Privacy is implicit in the notion of intimacy: “privacy is not merely a good technique for furthering … respect, love, friendship and trust, rather, without privacy they are simply inconceivable“ (Freid, 1970, p. 140).There has been a great deal of media and research attention to the issue of online privacy. Online social networks have been associated with an increased range of privacy risks, including wide dissemination and lack of “damage control” for overly hasty posts, and external risks from disclosure of information to employers, media and social predators (Rosenblum, 2007). It has been suggested that in addition to changing the nature of social networks, online social networking has changed the nature of privacy (Rosenblum, 2007). Tensions can arise between a culture of online disclosure, and a desire for privacy (Kane, 2010). Despite this, “the exhibitionism and voyeurism implied by participation in social network sites has ill-defined but nonetheless very real limits, and the expectations of privacy have somehow survived the publishing free-for-all“ (Calore, 2006, p. 1).

The privacy controls and settings offered by social network sites have become much more sophisticated, but it is less clear whether or not they are always used (Skeels & Grundin, 2009). It has been suggested that many SNS users are “oblivious, unconcerned, or just pragmatic” about their online privacy (Gross & Aquisti, 2005, p. 78), and not all users change their online behaviour to protect their privacy (Dwyer, Hiltz, & Passerini, 2007). Some users appear to assume that only people who comment on their posts are reading them (Skeels & Grundin, 2009). Complex privacy issues tend to arise in boundary crossing situations. Disclosures that are appropriate for bonding with close friends may not be appropriate for colleagues or managers. Similarly, people in senior positions in the workplace may wish to keep aspects of their personal life private, which limits what they will disclose on SNS (Skeels & Grundin, 2009). When people’s SNS connections span a range of personal and professional relationships, they are likely to be more cautious overall about what they disclose online (Skeels & Grundin, 2009). This enriches the findings of DiMicco et al. (2008), suggesting that while participation in SNS can be used to enlarge participants’ networks, and identify people that are likely to be compatible and develop closer ties with them, many participants perceive disclosure as potentially risky, and are cautious about what they will share in boundary crossing SNS.

Research Propositions

Based on previous studies of social ties, and privacy concerns in SNS, we developed the following propositions:

- “Bonding”: Participants in SNS will not be concerned about privacy, and will be willing to disclose their emotional status to other participants in an online network of people with whom they have close ties.

- “Bridging”: Participants in SNS will be more concerned about privacy and less willing to disclose their emotional status to other participants in an online network of people with whom they have weak or latent offline ties.

- “Boundary crossing”: Participants in SNS will be extremely concerned about privacy and unwilling to disclose their emotional status to other participants in an online network that includes “boundary crossing” relationships.

Research design and data collection

This research adopted an innovative design which used a combination of: social network visualisation tools, screen capture, and a personal (offline) diary to explore the nature of disclosures and social capital in boundary crossing SNS. The experiment investigated the willingness of participants to disclose their feelings online to different groups of participants. Emoticons were used to represent emotional state.

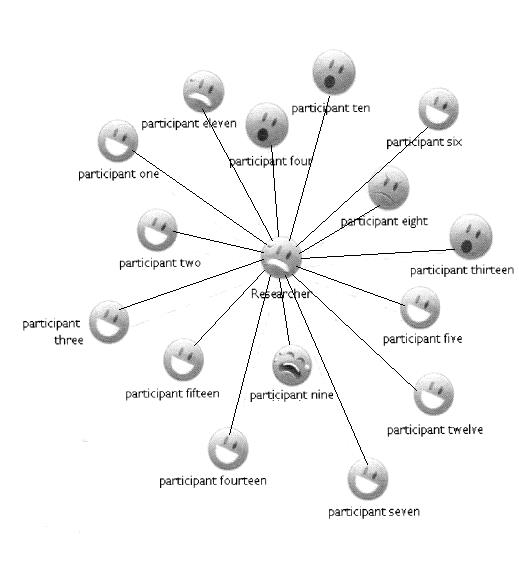

Since previous studies indicated that participants in SNS are not always aware of who may be reading their status updates, we created a dedicated online social network visualization for the purpose of the study. Visualizing a social network can become a powerful tool to allow for users to see how they are connected to any other person in their social networks (Torres, 2004). A visual representation of a social network can reveal latent connections and enhance the intuitive understanding of the social dynamics of a group and indicate a representation of “nearness” that users can easily comprehend Torres (2004). Since we were investigating the behaviour of people in SNS with strong ties, weak/latent ties, and boundary-crossing relationships, it was important that our participants could easily see who was in their network. Since previous research had found that Facebook users are not always aware of who is looking at their profiles, we used an application that provides a network visualisation of relationships and connectedness in Facebook. Participants created dedicated Facebook profiles (separate from their normal profiles) for the study and for inclusion in the visualizer http://vansande.org/facebook/visualizer/.

Since membership of social network sites and networks of individuals often span geographic and cultural boundaries, depiction of emotions included in the social network diagram needs to be widely understood. Recent studies of psycho-biology suggest that some emotions are biologically rooted with universally recognised facial expressions (Ekman, 1989). Members of different cultures, including visually isolated ones, matched a facial expression to a specific emotion with a consistent degree of agreement. Regardless of their cultural background, the respondents recognized and labelled five basic facial expressions of enjoyment, anger, fear, sadness, disgust and surprise in the same way (Izard, 1994). Emoticons were developed to express these five expressions, and card sorting was used to ensure that research participants interpreted them consistently. Emoticons were used as a proxy for emotional states in the experiment. Participants used one of the emoticons as their profile picture on their dedicated Facebook account, so that their emotional status would be visible to all the other participants in the network visualizer.

The experiment was conducted over ten days. Three scenarios were used.

- Days 1-4: A group of eleven people (participants 1-11) with strong offline ties (bonding social capital) began sharing their emotional statuses online with the other participants.

- Days 5-7: An additional group of four people (participants 12-15) with weak/latent offline ties to some of the original eleven (bridging social capital) was introduced to the network. All participants (the existing and new members) were required to update their emotional status daily. The new participants were peers but not close friends. The nature of the connection was that some of the people in both groups worked part time as teaching assistants in the same university department.

- Day 8-10: A professional participant (participant 16) in a position of power relative to the existing participants was added to the network (boundary crossing social capital). All participants were required to update their emotional status daily.

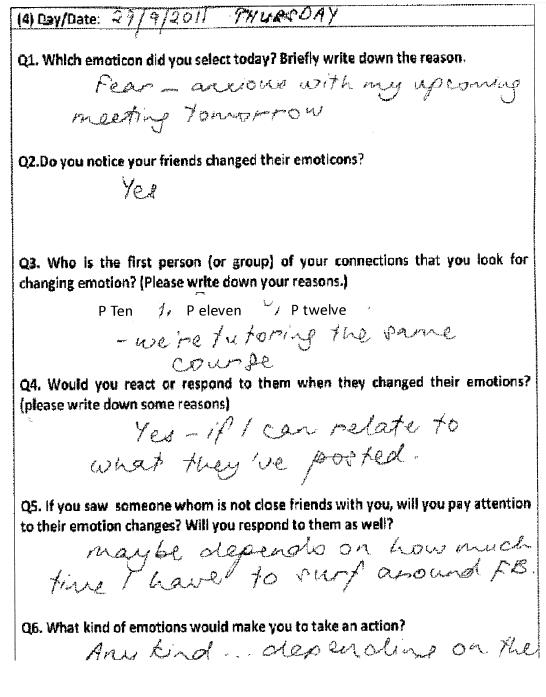

During the 10-day experiment, all participants were given the same instructions. Participants were asked to update their emotional status at least once each day, and to check the emotional status of other participants using the visualizer. Since the visualizer was based on Facebook accounts created for the study, participants could also use all the normal facilities of Facebook to communicate with each other, and make posts. The researcher was a participant and was able to observe all activity. In addition, participants recorded their daily activities on a written diary, and submitted their diaries at the end of the experiment. Finally, a semi-structured interview was conducted with participants at the end of the experiment. A screenshot of the visualizer and an example of a daily diary are included as Appendix A.

A convenience sample was used, based on participants acting in different roles within a university department. In terms of their regular (pre-experimental) use of SNS; all participants self-identified as active Facebook users, with between 100 and 400 connections, and updated their information daily. Five participants were males, and eleven were females. Two users were in their thirties, and thirteen were in their early twenties. The professional participant was in her fifties. Of the sixteen participants, most had previously used Facebook only to interact with people they already considered to be friends. Only three participants had included people they only had a professional relationship with (for example, their colleagues or students) in their regular Facebook network. The others used their Facebook networks only to keep in touch with friends and family from school, university, and also, for people who has moved away from home town to attend university, contacts in their home towns and countries. Only two participants currently used the privacy controls available, both of these had professional as well as social connections in their network.

Results

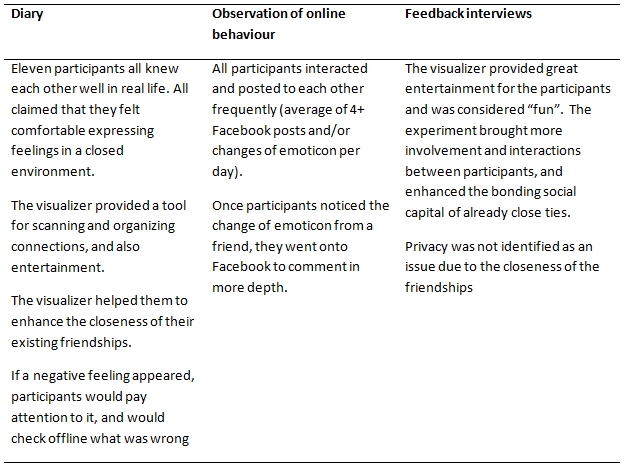

Scenario 1

In Day One, eleven participants (five males and six females) joined in the experiment. All of them claimed that they knew each other very well and had close ties in real life. During the first four days, these eleven participants put up emotional statuses on Facebook at least once a day, often several times/day. Participants were positive about the experience in their diary entries:

Participant 1 (interview): “This is a really fun thing to do, because we already knew each other quite well. It just gives more chance to be connected. I feel much closer and comfortable in a closed group. And yes, I do check all these friends’ activities quite a lot. I think it’s just because we are studying the same thing and also working together. There are so many things I can share or link with them.”

Several people commented positively on the value of the visualizer for scanning their networks quickly:

Participant 3 (interview): “If anyone put up something, I will notice, for sure. If it’s a negative thing, I think I will immediately ask the person what went wrong. ”

Participant 7 (diary): “The application was great fun to look at who’s connecting with whom. I think it’s all about networking. It’s a better tool to organize friends in this way than what Facebook does. Good to see who my connections are, and someone whom I might know connects to my friends.”

In the feedback interviews, participants also commented that they saw the visualizer as a tool to bring them more closely together. As a close group, they had a lot of inside stories to tell and share. The use of emoticons in the visualizer offered a unique way of getting friends’ attention first and sharing stories after.

Participant 9 (interview): “Because we all work together, and we talked a lot, it feels fun if someone put a strange face, and I would know what happened to him/her. It just gives me a way to feel more close to that friend. For example, if someone had an assignment due, and he/she put up a face to show the stress, I will immediately know what was going on, maybe, comment on her wall to cheer her up a little. But if I don’t what happened to the person, I might not do anything to it, because I don’t want to ask the wrong thing. ”

Participant 8 (interview): “Sometimes it (putting up an emoticon) was really good…and you know someone will understand without telling them what exactly happened. I think it’s just because those people know you so well in real life. Like this, they know about my life, and if I was putting up a sad face, they could relate and talk to me on the right things. It gives me more comfort than a general greeting from someone who might not know what was going on.”

Meanwhile, if someone posted a negative feeling, they went back to the Facebook page to post comments to ask the reasons why. Participants were not concerned about privacy and were not afraid of expressing their emotional status in the context of the experiment, as they knew it was a closed group.

Participant 6 (interview): “Maybe privacy is an issue, that’s why I prefer a closed group who can share feelings, and not worrying too much about what others think, because people already know me quite well. Because we know each other in daily life, it brings us more involvement and interactions.”

Although even then, some concern was expressed about the impression others might form if the facility was over-used.

Participant 3 (interview): “If it’s on the public page, I don’t think I will change my emotions often, maybe only if it’s something so extreme happened to my life.This time, because no one can see us, and those people already knew who I am in the real life, that’s why I don’t mind changing things just for fun. But also, I wouldn’t do it too much, because they might think I have nothing else to do.”

To sum up, this phase of the experiment was viewed positively by the participants, who felt that it enhanced the close ties they already had with the other participants. Using the visualizer was seen as fun, and the ability to quickly scan their friends’ emotional states was seen as useful for identifying events that should be responded to, and also as offering an added dimension of closeness in an already close group, accustomed to interacting on a daily basis. All participants agreed that they were not anxious about the privacy consequences of sharing feelings with close friends, and in a closed environment.

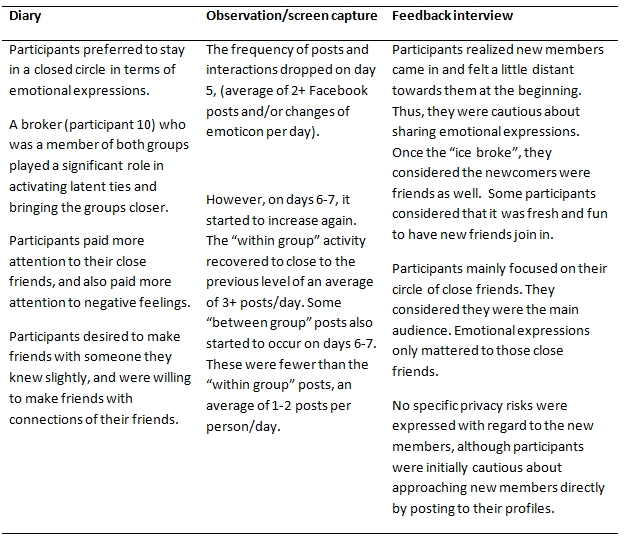

Scenario 2

From day 5 till day 7, another group of four participants joined the experiment. These four considered themselves as having a close relationship with each other. The two groups were engaged in similar activities and professional spheres at the same institution, and knew of each other, without being closely connected. Participant 10 from this group was the only person who knew most of participants in both groups. Initially, each group tended to stay close to their own circles and interact only within their group of close friends. There was little interaction across two groups, although they were aware of the presence of the others. However, participants did not express major privacy concerns.

Participant 3(interview): “I wouldn’t too much worry about those people looking at my status. I know they are friends too, just not my close friends. I think the whole thing is quite casual, I cannot see any harm there. People know me already. That’s why I don’t care that much. ”

Participant 9 (diary): “I know them, at least their names, and I know they are nice people. So I don’t worry about those emotion things. I think I just want to stay close to my friends (from first group); those people won’t notice me anyway. They have their own circles. ”

There was some evidence of activating latent ties between the groups. This was conducted through participant 10, who belonged to both groups. She was actively posting emoticons and feeds on Facebook, which attracted attention from both groups. Participants began to comment on her Facebook page following a change in her emoticon. Once this happened, some participants from the two groups began to comment on each other’s posts actively.

Participant 5 (interview): “Sometimes, I feel like getting to know people, but it’s difficult to go up to them and introduce myself. If I can see my friends connecting to them, I will ask them to bring me in. I think that could be a better way to make friends. ”

Participant 3 (interview): “I know who they (participant thirteen & participant fifteen) are, we once met….They are really really nice, so I don’t see any problem with talking to them [online]. Well, I might not take the first move to approach them on Facebook, but once I saw they joined in, I was quite happy. And yea, nothing serious, it’s relaxing. I think we can all be friends. ”

However, others used to opportunity to bridge the latent ties they already had with the new members into closer connections.

Participant 7 (diary): “I have known participant ten [member of both groups] since first year, we are quite good friends. We are always on Facebook and commenting each other. It’s good to see she’s here; we are doing not much different as we do every day. One thing I found quite interesting was that those participants from her group came to join us. First time, I thought it might be awkward. But I found they were really nice. I know their names for a long time, now it’s really good to know them a bit better.”

Participant 8 (interview):“I’m kind of person don’t want to go up to people first. You know, sometimes, I feel bad if I smile at someone, but they not smile back. So I think if they don’t do anything, I won’t do anything either. Good thing was that they started to comment on my posts. This was like an open door to me. I can feel their friendliness. So I started to talk to them, and see them as my friends now.”

Participant 5 (diary): “I only looked at those people I have been really close to at the start. After participant ten posted something on Facebook, and people from their group commented, I started to notice them. I think it’s a good way of making new friends.”

Others however did not feel it was appropriate to interact with the newcomers:

Participant 6 (diary): “Yeah, I noticed those people coming. Actually, I know some of the names, but I don’t know most of them in person. I met participant eleven and twelve a couple of times at university. So, I know who they are. But I don't think I will talk to them on Facebook, because I don’t know what to say. I will feel embarrassed if they don’t talk back to me.”

Some participants claimed that when they opened the visualizer, they noticed the negative emotions first. Then they looked at whether or not the negative emotions belonged to their close friends. If this was the case, they would immediately react to the situation, such as sending an instant message. If they thought they could see the friend in person, they would go and approach them and ask. However, if the negative feelings belonged to a member of the other group, they did not take immediate action.

Participant 12 (interview): “I won’t do anything if I see my friend’s friend put up a negative feeling on Facebook. Because I don't know the person that well, and don’t know what happened to him/her. He/she probably doesn’t want to tell the stories to people they don’t know as well. Or, sometimes, they just need a bit quiet time. But, I might tell my friend who connected with them, and ask if they want to check out what happened to those people.”

Participant 3 (interview) also indicated that he would not pay attention to people who are not close friends. Even though the negative feelings might concern him, he would not respond or react to them.

“No, I wouldn’t look at people’s Facebook or emotion statuses unless I know them very well. I might notice the negative feelings, like, if someone put up a big crying face, I might wonder what happened. But no, I won’t do anything to it. Maybe just check this person’s Facebook feeds to see what was going on.”

Overall, when the new group was introduced, mediated by participant 10, the two groups slowly began to interact. Although the number of interactions was not high, participant 10 played a significant role of breaking the ice and encouraging groups to activate weak ties. Most participants considered this was a really good way of making new friends. However, the participants were mainly focussed on their closed circle, and reported a much greater interest in the emotional statuses of their close friends, as well as a much greater willingness to follow up with offline contact. Interestingly, participants were not overly concerned with privacy issues; seemed to respect each other’s privacy, and were not overly concerned about disclosure. This seemed to be because the participants were all peers, and the environment was a closed network, with a casual and social focus.

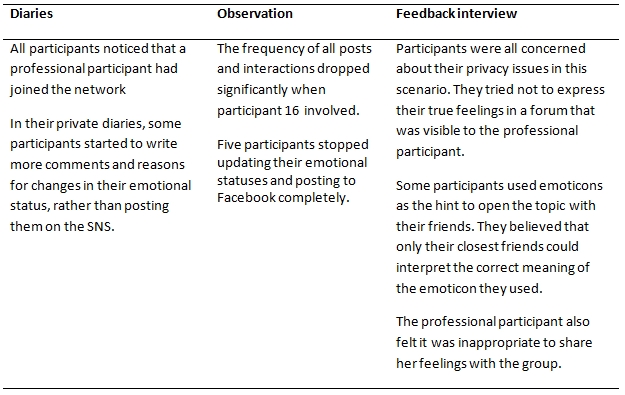

Scenario 3

From day 8 to day 10, the professional participant joined in the experiment. This sixteenth participant was a university senior lecturer who had multiple senior professional relationships (lecturer, supervisor, employer) with the participants. She was a regular user of SNS for professional contact, family contacts, friends and also keeping in touch with former students. All participants knew who she was and her role in the organization before she joined. She was widely liked and generally trusted. Despite this, the introduction of this participant had a dramatic effect on group behaviour. Five participants stopped updating their statuses completely. Three of these were males. In written diaries there were no specific mentions of participant 16. However, they kept recording their reasons for the changed emotional statuses in diaries. It was obvious that participants were anxious about privacy and stopped their activities in the public space. Through the feedback interview, participant 11 stated his perspective.

“Yeah, yeah, I did notice she (participant 16) joined. That was a bit of a shock. I know it was for the experiment, in real life, I don’t think I will accept her as my Facebook friend, because to me, Facebook is too casual. I only want my close friends or causal colleagues to see, not someone like her, too professional. Maybe LinkedIn will be better place for people who want to connect with professionals. Well, but I think it is hard to say no anyway. I know nowadays, a lot of employers go on Facebook to check people’s profiles. ”

Participant 14 also commented on this phenomenon during the interview.

“I was so excited to see she’s joining us. You know, that means someone wants to be our friend. That is really interesting and fresh. But after a while, I start to realize that she is a lecturer. So, I might need to watch out what I am going to say on Facebook. I don’t want her to misinterpret my words, or any expressions. Because I don’t know her that much, I don’t want to ruin anything. Especially, don’t want those professional connections to misinterpret my behaviours.”

On day 9 and 10, some participants left a smiley face on the visualizer, and did not change them until the project finished. Nonetheless, they wrote down the comments on the diary. Participant 14 emphasized the privacy issues associated with the new participant.

“On day 9, I was going to write my assignment. It was going to be due two days after. I was so stressed out; because I thought I left it till the last minute. So, I tried to put a crying face, or something can mean ‘stress’ on my page. But suddenly, I remembered there was a lecturer there. I don’t want her to know I didn’t start my assignment yet. And also I was afraid that someone might ask me about that. So I decided not to put anything on. I will tell my friends sometime I see them, but maybe not on Facebook.”

Two participants believed that emotional expression in a boundary crossing “public” space (even though this was still a controlled experimental situation with only one boundary crossing member) was a danger, and might impact on their professional image (in interviews):

Participant 3: “I wouldn’t do much about emotions on Facebook, if I have added someone from professional places, for example, my work colleagues. They might join my Facebook, but I don’t know well enough to let them know my feelings. And also, I don’t want them to think me as an emotional person.”

Participant 12: “I don’t mind showing feelings to my very close friends, but not to everyone on Facebook. It’s dangerous, because you never know who’s watching you. Especially, I knew some employers start to check those social networks.”

Participant 8 made an interesting point in the interview, which showed that some people are willing to express feelings to others, but they tend to alter the way they do it, if they are in the public situation.

“I might just post, say a sad face on the wall, and let my friends talk to me privately. I think she (participant 16) cannot know what exactly that face stands for, but my close friends would know. So it might be a good way to hide true reasons on the public spaces. Of course, I also feel closer to my friends, as it seemed we shared a secret together.”

In conclusion, scenario 3 indicated that developing and maintaining their professional image was important and raised privacy concerns for participants. The professional participant also commented on her experience in the diary:

“I did notice today that [participant 3] was stressed about something, which seemed to be something to do with her work. I stopped by to see if there was anything I could do.”

However, overall, she did not spend a great deal of time on the experiment:

“I only had a couple of interactions with people that I had added for the experiment, and I only looked at the network maps once a day as I had agreed to. I only posted to people I already knew before the experiment, I didn’t post to anyone else. I sent my condolences to someone who was attending a funeral, and congratulated someone who was happy, because I knew what she was happy about. A lot of the time it didn’t mean much to me. Some of the people I only knew by name.”

She did not feel it was appropriate to share her own feelings:

“I probably wouldn’t do that very much anyway. But with this group, I just posted a smiley face and left it there.” At the end, she wondered: Will the people in the study all “unfriend” me now? Well, we will see what happens.”

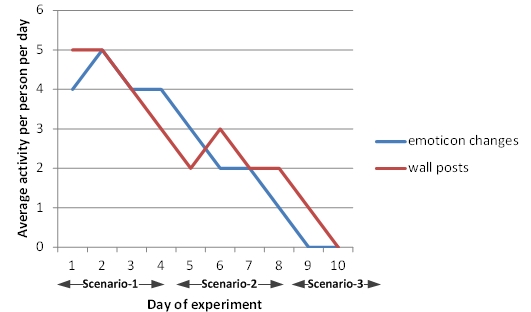

Discussion and Theory Extraction

Propositions one and three were strongly supported by the study, while findings for proposition 2 indicate participants have a nuanced approach to privacy and emotional disclosure in SNS, rather than the “flat” approach suggested in some previous research. The study results are discussed in the context of the research propositions, and some further insights arising from the study are also offered. A summary of the average activity per participant per day during the three phases of the experiment is included as Figure 1.

Bonding, bridging and boundary crossing

Proposition 1: “Bonding”: Participants in SNS will be not be concerned about privacy, and will be willing to disclose their emotional status to other participants in an online network of people with whom they have close ties.

This was strongly supported. Participants were not only willing to share their emotional statuses, they found it enjoyable and fun, and believed it enhanced their already close bonds. Offline and online relationships complemented each other. Participants enquired offline about online posts of emotional status. Our results contradicted the findings of DiMicco et al. (2008), who found that in a closed workplace group, participants with strong ties did not interact extensively online. However, DiMicco et al. (2008) did not specify the nature of interactions, while in our study participants agreed to share emotional statuses. This suggests that when participants are encouraged to share emotional statuses online in a closed group, SNS can complement and enhance their close ties and encourage bonding. Their online interactions mirrored their offline interactions in terms of time, emotional intensity, and mutual confiding (intimacy).

Proposition 2: “Bridging”: Participants in SNS will be more concerned about privacy and less willing to disclose their emotional status to other participants in an online network of people with whom they have weak or latent offline ties.

This proposition was supported, showing a complex and nuanced picture of privacy and willingness to disclose in a situation of weak or latent ties. Several participants welcomed the opportunity to activate the latent ties. After some initial caution, participants were willing to disclose their emotional statuses to the wider group. This was facilitated in particular by Participant 10, who had close relationships to members of both groups. People were influenced by the knowledge that the group was still limited to the experiment participants, and that the new participants were peers. However, their reactions to disclosure changed from the first scenario. Most participants were initially wary of the newcomers. They felt that the updates to their emotional statuses were aimed at their close friends and not the wider group, and conversely, that they should not follow up emotional disclosures from less well-connected people with more intimate posts or enquiries. Our study contradicts studies that found that online relationships in SNS are “flat” binaries of friend or not (boyd, 2003), that are shallow and disengaged (Gross & Aquisti, 2005, Rosenblum, 2007).

Disconfirming some previous studies (Kane, 2010), we did not see any evidence of voyeurism or exhibitionism in the emotional disclosures and behaviours of our participants. Instead, some participants expressed anxiety about being perceived as exhibitionist. Perhaps the online environment provides additional opportunities for people who tend towards that sort of behaviour (we are unable to comment on that), but we found no evidence that emotional disclosure in an SNS context encourages either.

However, following cautious initial contact, some of the latent ties bridged in the experiment began to develop into relationships of greater intimacy. This confirms previous studies that SNS can be used for scanning and activating weak and latent ties (DiMicco et al., 2008, Haythornwaite, 2005).

Proposition 3: “Boundary crossing”: Participants in SNS will be extremely concerned about privacy and unwilling to disclose their emotional status to other participants in an online network that includes “boundary crossing” relationships.

The introduction of just one professional member had a dramatic effect on the behaviour of the participants, even though the new member was well known, liked and trusted as a lecturer and mentor. Five participants were so unwilling to disclose their emotional status to a network that now included a boundary crossing relationship that they withdrew from that part of the experiment entirely (they no longer posted any changes to their emotional status). All participants expressed privacy concerns in their diaries or the follow-up interview. A significant gap opened up between the emotions expressed in the private diaries, and the emotions expressed in the SNS, even though only one new member had joined. Emotional disclosure in this relationship was seen as extremely risky. This suggests that the efficacy of SNS in strengthening latent ties depends greatly on the nature of those ties and the network purpose. Participants indicated that dedicated professional networks might be different, but in a social network aimed at sharing feelings, participants were uncomfortable with being authentic in the presence of a boundary crossing relationship, and felt the need to manage their online image and present only positive impressions. The professional participant also reported in the interview that she did not feel it would be appropriate to share her feelings with the group. This strongly supports the findings of Skeels and Grundin (2009) about privacy concerns in boundary-crossing relationships.

Other implications of the study

In addition to the findings relevant to the research propositions, other key themes emerged from the study, in particular with regard to the role of the visualizer.

Social Identity

Some of our results suggest interesting opportunities for future research using a lens of social identity theory for examining “public” and “private” behaviour in SNSs. Briefly, social identity theory posits that identity is derived primarily from group memberships. It further proposes that “people strive to achieve or maintain a positive social identity thus boosting their self-esteem, and that this positive identity derives largely from favourable comparisons that can be made between the in-group and relevant out-groups“ (Brown, 2000, p. 747). The observations of participant 8, describing how she updated a status in a public space which carried a meaning only her close friends would understand, like “sharing a secret”, suggests that the small group of closely bonded initial participants was forming an “in-group” with its own identity and forms of communication which could maintain its identity within the wider group. This ability to reintroduce intimacy into a “public” space is interesting, and may have parallels with the formation of “in-groups” in other semi-public contexts such as professional relationships.

Visualization

An innovative aspect of the study was the use of the SNS visualizer, with emoticons representing the participants’ current emotional statuses showing as nodes in the visualizer. This had several interesting impacts for both researcher and participants.

From the perspective of the researchers, the use of the visualizer increased the rigour of the experimental conditions. Our participants were extremely conscious of what they were disclosing and to whom. Our participants could not assume, as previous researchers had suggested, that while anyone in your network could look at your posts, only close friends and those that actively interacted with you were actually doing so. The behaviours we observed were carried out in full knowledge of who would be observing them. This was clear from the diaries: participants commented on new arrivals in the network, and actively reflected on their impact on the group, whether or not those participants interacted with them. The visualizer enabled us to make effective use of emoticons as a proxy for emotional status, and the willingness to disclose emotional status to others in the visualizer as a proxy for strong bonds. Participants were conscious that their selected emoticon would be the first thing about them that other participants saw. The fact that the level of activity shown in updating emoticons (and in some cases, following up with further posts or offline interactions) was closely related to the strength of the existing bonds claimed by the participants suggests that willingness to post emoticons on a SNS can be a useful proxy for the closeness of social ties between individuals and groups. The visualizer also ensured that participants were clear about who the other SNS participants were during each phase of the experiment, and were making informed privacy choices.

Further, the visualizer attracted comment from some of the participants. Several commented positively on the ability to quickly scan their networks: “This one is showing everyone in the same time, so you don’t have to go to Facebook to check. And it’s quite simple and good idea. I think this is another way to remind me who my friends are,” and “if they choose a particularly negative [emoticon], I might look to see if there was a reason why that they have chosen that. There are some people who I normally don't get feeds from because they send so many in, it clogs my wall. So yes, if I saw an emoticon for them I might… go and look if I want to know what’s happening,” and “If I saw an angry or sad face on my friend’s node I would want to know why so I would probably try to investigate I suppose or try to see how they are.” This suggests that the visualizer can further enhance, for participants, the existing “scanning” and “bridging” capabilities of Facebook (Donath & boyd, 2004; Ellison, 2007).

Others felt that the visualizer and the use of emoticons was a useful way to broadcast important events. Most participants also agreed that using emoticons to express negative feelings of that moment, such as sadness, to a wide network, could sometimes be useful and effective. “When my grandad passed away and I was thinking: I wish there was a way I could let everyone know at once, so I don't have to go through story re-telling many times, and I thought the idea of posting a sad emoticon would be perfect for something like this.”

Overall, the visualizer was effective both as a research tool for investigating intimacy in SNS groups, and as a tool for enhancing the experience of the participants. It was seen by participants as enhancing their interactions, enabling rapid scanning of their network, and contributing to the enjoyment of participating in a SNS. It was also a valuable tool for reinforcing to participants information about the membership of their network. Out study suggests that when participants were reminded, via the visualizer, that their network contained members with whom they had weak ties and boundary crossing relationships, they changed their behaviour accordingly. This suggests that SNS users might be well advised to use SNS visualization tools (which are freely available), as a matter of course, to remind themselves about the membership of their SNSs, and ensure their behaviour is appropriate to the audience.

Limitations and Further research

Our study took place largely within a university context (although several participants at the time of study were employed full-time in the IT industry). Professional associations existed between some participants who worked as teaching assistants in the same department. The results of the experiment would likely have been different in another context. Also, participants in the experiment were aware that they were observed, which may have influenced their behaviour. It was necessary for the researchers to have a presence in the network and to have links to all the participants in order to be able to capture data for the study.

Many other factors might also potentially influence online disclosure of emotional statuses. Gender, age, culture, experience with SNS, and personality characteristics such as extroversion and introversion could all be significant. Further research could use a similar experimental design to investigate the contribution of other factors to online social bonding and privacy behaviour.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this experimental study makes a two-fold contribution. First, it contributes to understanding the role of interaction on SNS in building and maintaining social capital, with the associated need for appropriate privacy controls. We provide a more nuanced understanding of online privacy expectations and behaviours in situations where different levels and types of interpersonal bonds and social capital exist. Overall, our findings contradict suggestions that users were “oblivious or unconcerned” about their privacy (Gross & Aquisti, 2005) and instead we found our participants were “pragmatic” (Gross & Aquisti, 2005), making informed judgements about the nature of the bonds in their SNS relationships, and the risks involved in disclosure, and adjusting their behaviour accordingly. We did not find evidence that online friendships are “flat” or superficial. The limits of online expectations of privacy, and the differences in behaviour between individuals with strong bonds and individuals with weak or latent ties were tacitly understood and observed by participants.

The permanence of digital interactions is frequently contrasted with offline communication. In our view, this is a somewhat arbitrary distinction. There are many situations that afford breaches of privacy. People have the capacity to eavesdrop, secretly record conversations, open other people’s mail, and so on, but by and large, they do not. Email has matured in this respect; many emails contain privacy warnings in the event that they are received in error. SNSs are also maturing, providing more nuanced privacy settings. In our study, the “boundary crossing” participant did not, in fact, spend a great deal of time investigating the other participants, was less interested in their activities than they imagined she might be, and recognised that the nature of the connections did not justify mutual intimacy and sharing. In our view, the “ill-defined, but real” boundaries of online privacy were observed. Perhaps rather than considering SNS participants to be naïve to make posts that might be embarrassing in a boundary-crossing context, the debate should be reframed; should we ask instead “why are [for example] employers accessing information that was not intended for them to see?”

A second contribution is our innovative methodology, using the visualizer, allowed both participants and researchers to rapidly scan social networks. We found that willingness to disclose the five “universal” human emotions as represented by emoticons to other participants provided a good proxy for the existence of close, weak, and boundary-crossing social ties between participants. We further found that the visualizer was a valuable and enjoyable tool to assist participants to scan their networks, observe appropriate online etiquette, and improve their social capital.

References

boyd, d. (2003). Reflections on friendster, trust and intimacy. Paper presented at the Intimate (Ubiquitous) Computing Workshop (Ubicomp, 2003), Seattle, Washington.

boyd, d. (2007). Social network sites: Public, private, or what? Knowledge Tree, 13, May. Retrieved from: http://kt.flexiblelearning.net.au/tkt2007/edition-13/social-network-sites-public-private-or-what/.

Brown, R. (2000). Social identity theory: Past achievements, current problems, and future challenges. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30, 745-778.

Calore, M. (2006). Privacy fears shock Facebook. Wired News, 6 September.

DiMicco, J., Millen, D., Geyer, W., Dugan, C., Brownholtz, B., & Muller, M. (2008). Motivations for social networking at work. Paper presented at the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW'08), San Diego. CA.

Dominion_Post_newspaper. (2012, 11 May). Job seekers asked for Facebook passwords, Dominion Post.

Donath, J., & boyd, d. (2004). Public displays of connection. BT Technology Journal, 22, 71-82.

Dwyer, C.,Hiltz, S. R., & Passerini, K. (2007). Trust and privacy concern within social networking sites: a comparison of Facebook and Myspace. Paper presented at the Thirteenth Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS), Colarado.

Ekman, P. (1989). The argument and evidence about universal in facial expressions of emotions. In H. Wagner & A. Mansteaded (Eds.), Handbook of Social Psychophysiology (pp. 143-164). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Ellison, N., Heino, R., & Gibbs, J. (2006). Managing impressions online: self-presentation processes in the online dating environment. . Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11, 415-441.

Ellison, N., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook "friends": Social capital and college student's use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12, 1143-1168.

Freid, C. (1970). An anatomy of values: Problems of personal and social choice. Cambridge, MA Harvard University Press.

Gerstein, S. (1984). Intimacy and privacy. In F. D. Schoeman (Ed.), Philosophical Dimensions of Privacy: An Anthology (pp. 265-271). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Granvotter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360-1380.

Gross, R., & Aquisti, A. (2005). Information revelation and privacy in online social networks. Paper presented at the ACM Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society (WPES'05), Alexandia, VA.

Haythornthwaite, C. (2005). Social networks and Internet connectivity effects. Information, Communication & Society, 8, 125-147.

Izard, C. (1994). Innate and universal facial expressions: Evidence from developmental and cross-cultural research. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 288-299.

Kane, B. (2010). Balancing anonymity, polularity & micro-celebrity: The Crossroads of social networking and privacy. Albany Kaw Journal of Science and Technology, 20, 327-363.

Parks, M. R. (2009). Explicating and applying boundary conditions in theories of behaviour on social network sites. Paper presented at the International Communication Association (ICA) Meeting Chicago, IL.

Putnam, R. (1995). Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6, 65-78.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Rosenblum, D. (2007). What anyone can know: The Privacy risks of social networking sites. IEEE Security and Privacy, 5, 40-49.

Skeels, M., & Grundin, J. (2009). When social networks cross boundaries: A Case study of workplace use of Facebook and LinkedIn. Paper presented at the Group'05, Sanibel Island, Florida.

Smith, J. (2009). December data is in: Facebook surpasses MySpace in US uniques. Inside Facebook, 8. Retrieved from http://www.insidefacebook.com/2009/01/08/december-data-is-in-facebook-surpasses-myspace-in-us-uniques/

Torres, P. (2004). Visualizing social networks: A social network visualization of groups in the online chat community of Habbo Hotel (thesis). Masters of Fine Arts, Parson's School of Design.

Warren, S., & Brandeis, L. (1890). The right to privacy. Harvard Law Review, 4, 193-220.

Appendix A

Correspondence to:

Mary Tate, BA(Hons) Massey; PhD Victoria

Senior Lecturer;

RH 504, School of Information Management

Victoria University of Wellington,

PO Box 600, Wellington, New Zealand

+64 4 463-5265

Email: mary.tate(at)vuw.ac.nz

Web page: http://www.victoria.ac.nz/sim/staff/mary-tate.aspx