Do questions matter on children’s answers about internet risk and safety?

Cristina Ponte1, José Alberto Simões2, Ana Jorge32 CESNOVA & Department of Sociology, New University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

3 CIMJ, New University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

Abstract

Keywords: EU Kids Online; children and the Internet; online risk; qualitative methods; critical discourse analysis

Introduction

Research has evidenced that children and young people growing up in different social and economic backgrounds have significantly different media experiences. This is visible internationally (e.g. Livingstone, Görzig, & Ólafsson, 2011, on Europe) and at national level (e.g. Seiter, 2005, on the US; Livingstone & Helsper, 2007, on the UK; Paus-Hasebrink & Bichler, 2008, on Austria). The Portuguese context, characterized by low levels of educational achievement among the adult population and by a great and fast expansion of internet access among children and young people in recent years constitutes a particular case for analyzing digital experiences among children living in less privileged families.

Digital inclusion was a major national policy in Portugal after 2005 having a particular focus on children and youth in 2008-2010. The national policies for digital inclusion, e-Escolas and e-Escolinhas, promoted owning laptops and internet access for students in the education system. This policy had a huge social impact: a large proportion of parents with low levels of income and education showed the desire to provide their children these modern resources, in contrast with the poor conditions they had experienced in their childhood (Ponte, 2012). By 2010, more than 800 thousand families had taken part in these programs, placing Portuguese children as European leaders in accessing the internet through their own laptops, as shown in the EU Kids Online survey (66%; EU average: 23%). However, this did not translate in a frequent use: only 54% accessed the internet daily (EU average: 57%) (Livingstone, Haddon, Görzig, & Ólafsson, 2011).

This research on deprived children follows our participation in two international research projects: the EU Kids Online project which provided the theoretical framework and the national results of the European survey in 2010; the Digital Inclusion and Participation project (2009-2011), which was focused on digital uses of minority groups in Portugal and the US, among them deprived children and youth1. When we decided to adapt the EU Kids Online questionnaire to a purposive sample of socially disadvantaged children, our aims were not only to know their contexts of access, usages and forms of mediation bearing in mind the national results from the European survey. We also wanted to pay attention to children’s perceptions of online risk and safety, expressed in their own terms, and to compare them with the answers from the national survey.

The sample was composed through Escolhas [Choices], a nationwide program of social intervention, aiming to promote social inclusion of socially vulnerable children and young people (6-24 years-old). The program has been running for a decade and puts a focus on the integration, embracing digital inclusion as one of its pillars. Mostly located in metropolitan areas, each one of the 132 centers has at least six PCs, broadband access and a printer; local teams are composed by 3-4 technicians and include a young person living in the community who acts as mediator. According to Escolhas’ statistics, in 2011, 10,700 children and young people between 6 and 17 years-old attended these centers.

Results from this purposive survey compared with the national results from the EU Kids Online revealed that we are not facing a completely digitally excluded group of children and young people, although their access to technology is ultimately influenced by their social and cultural background: Escolhas children are apparently more oriented towards entertainment, and some digital skills (especially informational ones) appear to be less present. Although the data are not completely conclusive, some findings go against the main interpretation that considers ‘social exclusion’ and ‘digital exclusion’ as equivalents (Simões, Ponte and Jorge, 2013).

The purpose of this article is to analyse children’s answers on risk perception through open-ended questions used in the EU Kids Online questionnaire and in the questionnaires used with this purposive sample. Our research questions are: what are children’s perceptions of risk situations and safety on the internet? How do they express them? Do children’s positions as active or passive persons vary according to the questions they are asked? What are the lessons learnt and clues for further research? Before analysing the results, next sections will discuss the concept of risk and the framework used in the EU Kids Online project, as well as the methodological tools based on previous experience with cognitive testing (Haddon and Ponte, 2012) and on critical discourse analysis.

Online Risks Within the Risk Experience

There is no consensus regarding what online risks consist of, not only because the very notion of what constitutes a risky activity varies across cultural and social settings but also because different persons might have different experiences and perceptions of what is risky to them. The issue, however, is far more complex than that. In existing literature, the debate around what constitutes a risk tends to oscillate between more “realist” perspectives, that believe risks as having an objective existence independently of social processes, and more “constructionist” ones, for which – at least in some of its versions – risks are a matter of pure construction (Lupton, 1999a). Although there are considerable differences among constructionist perspectives, they all seem to agree that “risk cannot be simply accepted as an unproblematic fact, a phenomenon that can be isolated from its social, cultural and historical contexts” (Lupton, 1999b, p. 2).

The way people engage with and construct different notions of risk in the context of their everyday lives is part of a more complex and less restrictive definition of the concept (Tulloch & Lupton, 2003). In Risk Society, Beck (1992 [1986]) defines risk as a way of dealing with hazards and insecurities brought about by modernization. In this context, reflexivity appears as a way of dealing with the uncertainties of practices that need to be monitored and evaluated constantly. However, in Beck’s definition, people are mainly regarded as rational and calculating actors, choosing between various perspectives of risk provided by expert knowledge systems (Lupton, 1999a, p. 108). Consequently, little attention seems to be paid to the way lay actors build their own assessments of the world. As Wynne notices, lay knowledge tends to be far more contextual, localized and individualized, reflexively aware of diversity and change, than the universalizing tendencies of expert knowledge (Wynne, 1996).

Within the constructionist perspectives introduced by Lupton (1999a, pp. 84-171), besides the role played by subjectivity, it is noted that the relation of the self with otherness plays an important part in the way risk is experienced and understood. What is “strange”, “unknown” or “different” somehow embodies the anxieties and fears around what counts for as a risk across different contexts. However, the relation with otherness also involves ambivalence: what is strange and different is rejected as a reason for apprehension, but at the same time it appears as a source of fascination and desire. This brings us to another dimension of risk that should be acknowledged: pleasure. Although usual discourses about risk tend to stress its negative nature, many experiences and understandings involve positive outcomes. This might explain why many adults and adolescents are willingly engaged in extreme sports or other similar activities, which test boundaries and control over their bodies’ integrity. In this way, transgression and desire appear as counterpart notions of fear and repulsion. As such, risk-taking cannot be ignored as part of what might define risk or how it is represented in distinct discourses.

In this manifold view of risk, it is crucial to consider the discourses that contribute to build something as a “risk”. These discourses not only define risk, they also attempt its regulation through distinct strategies and practices, requiring awareness and management by institutions or individuals. As pointed out by the “governmentality” perspective (Lupton, 1999a, pp. 87-99), risk management includes several regulatory strategies more or less noticeable, developed by governments, institutions and experts, as well as self-regulatory practices carried out by lay persons in their daily lives.

This brings us to online risks and the practices and discourses built around the experiences and uses by different people. When it comes to children and young people, discourses about the internet and online technologies tend to be polarized, either noticing its positive effects as means of knowledge, learning and communication or observing its negative consequences, such as pornography or contact with paedophiles, among many others. The problem with these polarized views is that they tend to divert the public opinion from the actual online experiences. In fact, discursive constructions around “moral panics” prevent us from focusing on the genuine threats that someone might experience online (Livingstone, 2009). Nonetheless, different risks have different levels of social acceptance: pornography, in some of its forms, tends to be socially and culturally tolerated or even accepted, whereas paedophilia is generally considered as hideous. Likewise, activities such as contacting online someone we never met offline are more ambiguous: they might be or not perceived as a risk and have (or not) a negative consequence.

Two assumptions are specific about online risk when it comes to children, and somehow explain the moral and media panics it provokes: not only do children’s online risks seem to be vaster (in variety and number) but also control over what happens online is apparently weaker than in regard to offline risks. As Livingstone points out, two forms of cultural protection seem to be undermined when we consider online risks among children: “individual literacy (reading ability, rational thought, critical judgement) and the mediating practices of parents or teachers” (Livingstone, 2009, p. 151). However, this image of the child in danger or in a vulnerable position is complemented by a counter-image of the child as agent, actively engaged in risky experiences and situations. As mentioned, risk-taking also characterizes many adolescents’ uses of the internet. Since part of growing up involves risk-taking, the internet appears just as another realm for exploring risky situations.

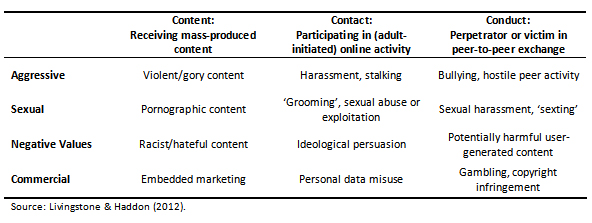

Another important distinction has to do with differentiating risk from harm. Several children may be involved in risky online activities but not all experience harm. The EU Kids Online research has distinguished risky from harmful situations on the internet, exploring factors for resilience and classifying the risks of harm to children in an inclusive and heuristically adjustable approach. The classification, as shown in Table 1, distinguishes content risks (in which the child is positioned as recipient of mass distributed content), contact risks (in which the child is participant in an interactive situation predominantly driven by adults) and conduct risks (where the child is an actor in an interaction) (see Livingstone & Haddon, 2009; Livingstone, Haddon, Görzig, & Ólafsson, 2011). These risky situations may lead to harmful consequences or to opportunities, namely the one of acquiring resilience, making choices and producing counter-narratives.

Although this distinction has to do with the role the child plays in the communication process, it can be more analytical than empirical, since in some occasions these roles may change or even overlap. While it is possible to distinguish, identify and classify such practices according to the above proposal, nevertheless listening to children’s insights on risks also opens room for unexpected considerations and reveals life horizons beyond the online environment, as we will see.

Methodological Approaches

Our initial aim was to compare, as far as possible, the Portuguese results of 1000 respondents on access, uses, activities, skills, mediation and risk experiences with the ones from a sample of children and young people attending Escolhas, in order to identify similarities and differences. It was not ignored that EU Kids Online was a representative sample with a considerable dimension obtained using a random route method, while the Escolhas sample was purposive, obtained from specific contexts, and substantially smaller; therefore, the purpose was not to make generalizations about the population at stake.

Firstly, we selected 23 questions from the face-to-face questionnaire following its protocols and guidelines. However, a discussion with Escolhas local coordinators and monitors made clear that even the 14+ year-olds would be unable to answer many of the questions by themselves, hence implying the reduction of sentences to a minimum of information. After a pilot test, the final questionnaire was divided into two versions: one for younger (9-13) and another for older (14-16) participants. The version for the 9-13 was a structured interview of 29 questions on access, usages and forms of mediation; the version for the 14-16 was a self-completion questionnaire of 29 questions which also included two on aggressive and sexual risks. Both questionnaires included a final open-ended question on coping with online safety.

In fact, avoiding an association between children and youth living in socially deprived environments and negative experiences, a frequent social practice with impact on their identity construction, we decided to reconfigure the EU Kids Online question: at Escolhas, younger children were asked on safety awareness and precautions; the older group, which had already been asked two closed-ended questions on risk, was asked in a position of peers’ advisors. Given this reformulation, the open-ended questions remain only partially comparable. The conditions in which children were asked also diverge: the EU Kids Online survey was conducted at children’s home, while Escolhas survey occurred in informal youth spaces, which these children frequently attended and were familiar with. Table 2 presents the open-ended questions, its placement in the survey and information on the location of the interview.

The interviews at Escolhas occurred between March and May 2011, in 19 centres in the metropolitan areas of Lisbon and Oporto, almost a year after the EU Kids Online fieldwork. Children were informed about the aims of the interview (i.e., examine their habits and uses of the internet). After being invited to fill in the questionnaire and answer to the questions, they received a gift, a t-shirt with a safety message on the internet. While some refused to participate, others accepted the invitation by answering with different levels of personal involvement and attention.

Let´s now present the analytical tools. As cognitive research has shown, in order to analyse how children answer a question, one has to evaluate their understanding of the question, his/her ability to answer, any ambiguity or other difficulty that may emerge and in general how he/she feels about the process of answering. Although these actions could suggest a linear routing, they actually involve numerous iterations of and intersections between the different phases: comprehension, retrieval, judgement and response (Tourangeau, Rips, & Rasinski, 2000).

Comprehension covers such elements as how respondents interpret the question, their basic literacy in terms of whether they can understand it or whether there are vocabulary problems that mislead them, confusing intended and literal meanings, misinterpreting the intended meaning and whether long and overly complex questions are difficult to understand.

Retrieval refers to the process whereby, having understood the question, the respondent has to recall the relevant information from long-term memory, being this information factual or attitudinal. Difficulties in remembering may reflect the fact that the information requested is judged as being not important enough, too distant in the past or too frequent.

Judgement is the process by which respondents formulate their answers. Some respondents may not have thought much about the topic until being asked the question. Others may feel ambivalent about what exactly counts as the correct answer. The emotional and moral charge of sensitive topics also affects these judgements and the willingness of interviewees to respond.

Response is the final task and involves choosing the words. This can be influenced by the effects of social distance between the respondent and the interviewer (potentially affecting the rapport), by concerns about the anonymity and privacy of responses as well, and whether, in the case of sensitive questions, the respondent is comfortable at all to provide an answer.

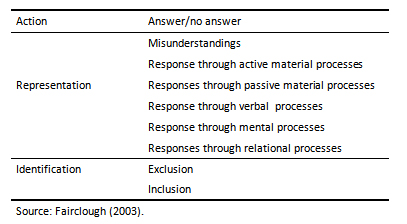

Taking into account this cognitive context and considering children’s answers as texts, we opted for the textual analysis as explored by Fairclough (2003). The author distinguishes three simultaneous meanings contained in a text: action, representation and identification.

Action includes the categories of the speech function (statement, demand, etc.) and the grammatical mood (declarative, interrogative, etc.). Answering a question related to risky/safe online experience implies a cognitive process that refers to: understanding (what is this?); retrieving (when did this happen?); judgement (do I want to answer this? How will I answer?); and a response translated into an action (no answer; answer).

Representation is the process by which extra-linguistic reality is semantically depicted in multiple ways by the discourse in clauses. An essential tool in the analysis of representation is the semantic concept of transitivity, defined by Fowler (1991, p. 71) as “the way the clause is used to analyse events and situations as being of certain types”. According to this semantic perspective, clauses contain processes (generally realised as verbs), participants (subjects, objects, indirect objects of verbs) and circumstances (adverbial elements such as time and place).

For the purpose of this analysis, we use four representational processes: material, mental, verbal and relational (Thompson, 1996).

a) Material processes refer to acts such as doing, happening, creating and changing; participants of these acts are either actors (those who do) or goals (those whom things are done for). Bothering/safe experiences on the internet are considered as active material processes when the child’s response describes what he/she or a person about his/her age does (for instance, send a message to go somewhere); they are considered as passive material processes when the child reports what is done by others affecting him/her or a person of his/her age (e.g. strangers trying to enter into conversation);

b) Verbal processes are those referring to all the actions that are about saying something (promising, talking or warning).

c) Mental processes are related to the internal world of the mind, such as feeling, liking, wanting, thinking or seeing a certain phenomenon. In these children’s answers, the dominant mental process is related to the act of seeing. Feelings and evaluations also appear, but less frequently.

d) Relational processes are the ones by which a person sets up a relationship between an object and a quality. In this case, they happen when the child associates the internet as the space of pornography, violent videos or unknown people.

Integrated in these processes, the memory retrieval may activate factual representations, presenting specific social events experienced by the child or other people about his/her age in the past, or it may reproduce “generalized attitudinal representations over series of social events” (Fairclough, 2003, pp. 137-8). This is particularly visible in answers related to sexuality, as we will see. They largely present the self-incorporation of generalised regulatory risk strategies, such as the case of representing sexual risk and harm through mental processes (e.g. to see naked people).

Identification is the third component of meaning. It reports the style, the “discoursal aspects of identities” (Fairclough, 2003, p. 159). Styles of identification may be more or less charged by moral judgements, “statements about desirability and undesirability, what is good and what is bad” (Fairclough, 2003, p. 172); and by modality, the degree of affinity towards representations (Hodge and Kress, 1988). Looking at how the child answers to the question contributes to signal possible different forms of identification with the issue. We will distinguish between exclusion, by which the child places himself/herself out of the representation, and inclusion, with or without personal commitment.

Table 3 presents a grid for qualitative content analysis based on these theoretical contributions and on an exploratory analysis on children’s answers. All answers were submitted to this grid and classified accordingly, using MAXQda software.

Results and Discussion

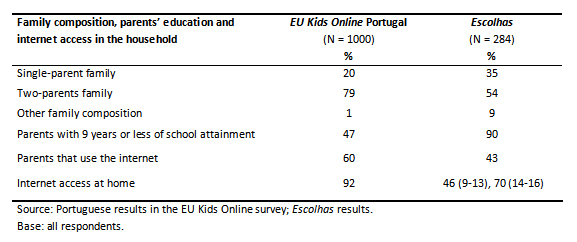

Before presenting how children in both samples answered to the open-ended questions, we briefly compare their contexts. As Table 4 shows, the proportion of families that do not fit the normative pattern regarding household composition is clearly higher in Escolhas: two-parents families represent about half (54%) of the sample, far below the 79% in the EU Kids Online sample; conversely, single-parent families have a higher proportion (35%, against 20%), and situations where a grandparent or an uncle takes up the role of guardian are also slightly more common (9% against 1%). According to the national results, almost half (47%) of the Portuguese households with children accessing the internet have a parent who only achieved the basic level of education (9 years or less) (Ponte et al., 2012); among Escolhas this percentage reaches almost the entire sample (90%). The internet access at home is also much scarcer among Escolhas, particularly among younger children. This lack of access may be related to parents’ lower levels of education, thus postponing children’s internet access at home, and to the fact that most of the parents are themselves non-internet users.

Let´s now look at the questions introduced in Table 2 using the grid for qualitative content analysis (Table 3). As far as Action is concerned, in the EU Kids Online sample 44% answered Q1; among Escolhas, 73% answered Q2 or Q3. Besides constraints associated with time and fatigue, the latter two questions, opening up room to express personal positive statements, may have contributed to a greater will of responding.

In what regards Representation, among Escolhas some answers didn’t fit with what was expected. For younger children, safety on the internet was understood retrieving concrete or generic facts and judgements that revealed economic constraints, lack of hardware skills or even fear of damaging material that is not their own:

- We have to pay for the internet every day or otherwise they will cut off the internet. (Girl, 10, Escolhas)

- You can’t be around the computer all the time with water, as happened to my mother. (Girl, 9, Escolhas)

- You can’t punch it when it’s not working, nor switch it on and off all the time. (Boy, 11, Escolhas)

- Be careful about what you put your hands on, it might not be yours and get ruined. (Boy, 12, Escolhas)

Based on children’s representations on risk and safety, Table 5 presents a hierarchy of common topics, allowing us to compare answers.

The top three positions express a reverse picture: while bothering is clearly related to contents, safety almost ignores those topics, stressing contact and conduct practices instead. It is worth noting that sexual and violent contents are almost absent from the Escolhas sample, answering on safety.

Facing unwanted sexual and violent contents are the key experiences associated with Q1, both being in 27% of the responses. Both are part of a perennial cultural repertoire on negative media effects over children. Hence, these answers placing children as recipients of mass-produced content suggest the self-incorporation of those dominant perspectives on media risk. They may also reproduce an awareness of what is the socially desirable answer or the third person effect in communication (Davison, 1983). The location of the interview in the household and the parents’ proximity may also have had a possible influence: in fact, the Portuguese parents express the highest concern with children seeing inappropriate material on the internet (61%; EU average: 32%) (Livingstone, Ólafsson, O’Neill, & Donoso, 2012).

Besides mass-produced contents, bothering experiences related to sexuality include conduct and contact situations, although receiving much lower values (respectively 5% and 3%). As the answers below illustrate, these sexual references cover a diversity of levels and meanings:

- Men who mess with boys. (Girl, 12, EU Kids Online)

- When I opened the Messenger there was a character there that said that doing nudity didn´t matter. (Girl, 13, EU Kids Online)

- See people having sex or naked people. (Boy, 14, EU Kids Online)

- Pornography. (Boy, 15, EU Kids Online)

- See erotic images or people to do sex. (Girl, 9, EU Kids Online)

- Erotic pictures or things that you do not usually see and hear at home. (Girl, 16, EU Kids Online)

Some answers to Q1 suggest family attitudes where a cultural silence involving youth and sexual education is prevalent, where sexual images and words seem to be taboo, as expressed by the last citation. Other results from the EU Kids Online survey confirm this picture: among children who have seen sexual images online, the Portuguese parents have the lowest account on sustaining that their children have seen such images (2%; EU average: 35%), with 54% answering ‘no’ and 43% declaring they don’t know (Livingstone, Haddon, Görzig, & Ólafsson, 2011, p. 55).

By contrast, among Escolhas respondents, only two answers explicitly report sexual contents (in both cases, the word is pornography), and explicit references to violent, aggressive or negative contents are almost absent. Some reasons may be considered for this difference. The online environment among Escolhas may be more “supervised” due to the access in a semi-public place with filters and monitors. Another possible reason is that the distinct questions (bother things affecting others vs own safe practices) may have induced different understandings related to various positions and internet uses (e.g., receiving contents or unwanted contacts; being involved in communicative acts). Nevertheless, the traditional moral concerns with children and the media related with sexual and violent contents didn´t come up immediately to children’s minds when they were asked about safe uses of the internet. In this case, concerns with contacts and conducts seem to be much more relevant than those related to contents.

Both samples use ambiguous expressions, such as inappropriate contents, dangerous sites or bad things, which don’t fit easily with the categories of risk introduced in Table 1. The weight of these generic and morally charged expressions is almost the same: 10% for EU Kids Online, 11% for Escolhas. It seems as though these risks are in such a taboo domain that they can’t be referred to.

Although in Escolhas there are almost no explicit references to sexual risks, the expression contacts from adults with bad intentions can be a way of referring to them. The lack of explicit sexual references may be also related to a more frequent use of restricted codes in language-based subjects among working class environments (Bernstein, 1974). Verbalising experiences related to sexuality in a formal situation such as answering a questionnaire is also a sensitive situation and it may have activated the use of ambiguous words.

Recalling the ambivalence of the relation between the self and the otherness, the verbal process of talking with strangers involves simultaneously contact and conduct. It is the third representation of risks among the EU Kids Online sample and it leads among Escolhas. Two other topics related with online exposure and self-protection emerged from both samples: being contacted by strangers and self-disclosure of personal data. The three topics interestingly place online contacts and conducts ahead of the (more passive) position of online recipients of mass-produced contents.

Talking with strangers is a frequent reported social event related to online risks. Again the Portuguese parents express a high concern with their children being contacted by strangers (65%; EU average: 33%) (Livingstone et al., 2012). However, for children living the online experience and facing the trivialization of expressions such as “being friends” on Facebook, what does this image of the stranger mean? Meeting new people is part of social life, and this is particularly important in adolescence; the pleasure of having contacts and exchanging correspondence is anchored in the memories of teenage years. Talking with strangers has to be related with this human and social experience, and we need to consider how it may generate harmful experiences as well as stimulating opportunities.

The issue is particularly relevant among Escolhas respondents, where children’s subjective experience of safety on the internet involves mainly awareness in contacting others out of their personal contacts. In fact, almost half of the answers (46%) report communicative exchanges with people they don’t know personally, far above the unidirectional experience of being contacted by strangers (14%). These answers link online safety with avoiding or being careful about talking with strangers. Also in the EU Kids Online survey, children’s statement about talking with strangers - involving both contact and conduct - duplicates the statement about being contacted by strangers (respectively 18% and 9%). Taking into account that the question was on what bothered a person of their age, it is worth to consider this position of agency. Interestingly, mentions to offline meetings are relatively low (3% in EU Kids Online; 5% in Escolhas). Thus, contacting/being contacted by unknown people may represent a potential risk of harm or an opportunity for pleasure – the exploration of self-competences, as expressed in this counter-narrative of a teenage girl: I’ve talked and met with unknown people and it always turned out OK. If everyone has the caution and attention I do, no harm will happen. (Girl, 14, Escolhas).

It is worth noting how the ways of answering the question differ in incorporating risk management, i.e., in the judgement of the situation. Examples below suggest a distinction between talking with strangers under specific conditions (keeping reserve about personal information, for instance) as a safe way of using the internet, against a vision that identifies the act of talk itself as harmful:

- Not talk about my things to people I don’t know. (Boy, 9, Escolhas)

- Talk with unknown people who may be someone else. (Boy, 10, EU Kids Online)

- Be careful with the person you talk to, not telling your real address and not putting my picture there. (Girl, 10, Escolhas)

- Talking in a chat with people who you do not know can be dangerous. (Boy, 12, EU Kids Online)

- Speaking [to] unknown people, thinking that they are one thing and they are the opposite. (Girl, 16, EU Kids Online)

Presenting low values in both samples, aggression by known people, as it happens with peers, is more present in the EU Kids Online survey. Commercial contents associated with negative experiences are also higher than among Escolhas, maybe due to a more intensive use. In both samples, commercial risks are reported mainly by older respondents:

- When stuff to win headphones show up, don’t pay attention. (Boy, 13, Escolhas)

- Advertising messages that they send to our mail. (Boy, 15, EU Kids Online)

- When one opens certain pages on the internet and pop-ups appear. (Boy, 16, EU Kids Online)

Interestingly, two topics related with risk control, namely self-inhibition and technical problems, emerge from Escolhas respondents and both are residual in the EU Kids Online survey. Especially for younger deprived children, safety is related with limited internet use. They mention that they feel safe online because they just do a limited number of activities or that they are there for short periods of time. If this avoids facing unexpected and problematic situations, it also prevents children from improving their internet experience and going further into other layers of opportunities. The structural conditions in which they access the internet (see Table 4) suggest that these younger children face more restrictive infra-structures and less parental mediation at home; some impose themselves self-regulation so as to avoid the unknown:

- I don’t have e-mail, I don’t have Facebook. (Girl, 9, Escolhas)

- Playing! It has no danger. (Boy, 9, Escolhas)

- I put a game up there, but I don’t play anything else. (Girl, 9, Escolhas)

- Sort of, playin’ stuff, seeing stuff that is to learn, seeing stories and nothing else. (Boy, 11, Escolhas)

- Not going to world sites. (Boy, 13, Escolhas)

While at national level, technical risks seem to be a past problem solved by adequate virus protection of personal devices, they appear in 10% of Escolhas answers. It is worth noting that children express not only the need of attention to virus but also to the material that doesn’t belong to them:

- It’s having the antivirus turned on. (Boy, 11, Escolhas)

- Being careful with what we handle. It may not be ours and we may damage it. (Girl, 12, Escolhas)

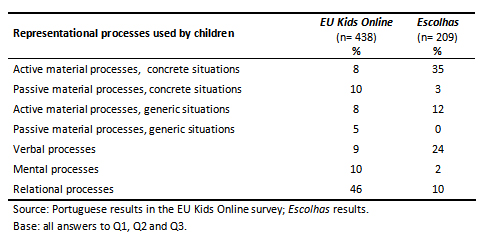

Exploring these representations, Table 6 presents results on material, verbal, mental and relational processes. Material processes are divided in four subtypes distinguishing child’s active or passive position, on the one hand, and the retrieval of concrete or generic situations, on the other.

As Table 6 shows, children represent textually their answers in two contrasting ways. Answers on bothering experiences of others are dominated by relational processes. They also include more mental processes mainly related with seeing, and more passive material processes, placing the child as the goal of someone else. In contrast, more than half of the answers on safety use active material processes, these being expressed by the child’s agency and retrieved in factual, concrete situations.

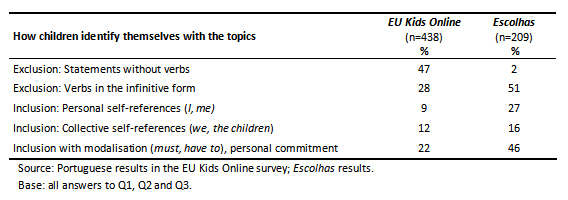

Moving to the third level of analysis, Identification, the choices on editing responses are narrowly tied with the ways children present themselves inside or outside the representation. Thus, as identification is deeply related with representation, it is not a surprise that most of exclusion occurred with Q1, while inclusion in different forms appears strongly related to Q2 and Q3, as seen in Table 7.

(multiple coding).

As Table 7 shows, two out of three Q1 answers place the respondent outside of what he/she is reporting. This suggests a self-presentation of distance from those bothering things that happen to others:

- Violent games can bother sensitive people and stuff. (Girl, 12, EU Kids Online)

- Things about drugs and alcohol, sexual relations. (Girl, 13, EU Kids Online)

- Sexual images and movies, images of people abusing children, threatening conversations (Girl, 15, EU Kids Online)

By contrast, answers to questions that invited children to consider internet safety (Q2) and to advice peers on online safety (Q3) present high values of inclusion. This happens both at an individual level (I, my experience…) and as members of a group (we, the children):

- Don’t talk to people I don’t know. A week ago I was checking who I knew on Facebook and sending the other away. (Boy, 9, Escolhas)

- I don’t talk to people I don’t know, and I set the social networking profiles private. (Girl, 13, Escolhas)

Almost half of Q2 and Q3 answers expressed personal commitment with what is said, this being twice the response to Q1. The use of the imperative mood to an imagined audience suggests that young respondents appreciated the position of advisors:

- Being careful with what we do on the internet, about who we talk to, about things we don’t know how to do, virus and stuff, we have to ask for help to an adult. (Boy, 12, Escolhas)

- Don’t answer to what is not appropriate for you. Sometimes, certain things appear here and I leave them for later. (Boy, 13, Escolhas)

- That internet, as everything else, has positive aspects. We should only use things with the proper information. We must have precautions with everything; the internet is just one more thing to add up to the list. (Girl, 15, Escolhas)

Even Q1 opened room for commitment, such as the incorporation of self-regulatory practices or challenging political entities:

- Movies that have red dot, that is not suitable for my age. (Boy, 11, EU Kids Online)

- Sites that are not suitable for our age and we must be careful, our personal data may be used for very dangerous purposes. (Girl, 14, EU Kids Online)

- Excessive violence, porn, commercial products that are totally annoying and I think the European Union should use its power at computer level to block websites that we all know where we can find that content (Boy, 15, EU Kids Online)

Conclusion

Comparing two samples of children, this article analysed to what extent the way questions are phrased and the contexts in which they are asked matter for children’s answers on risk and safety. From a theoretical point of view, we discussed the concept of risk by considering different constructionist perspectives and the great deal of ambivalence of the concept. This ambiguity is evident in children’s discourses about what is a “bothering situation” or a “safe activity” online. Methodological frameworks borrowed from cognitive sciences and from critical discourse analysis were also helpful in the process of making clear how particular social notions emerge from those discourses.

Part of the different considerations on what risk and safety mean has to do with the way questions are phrased but also with how they are understood by children and how those questions activate particular cognitive processes which are social and culturally embedded. In fact, the open-ended questions allowed us to capture non-expected interpretations and perceptions, by positioning children at the centre of discourses. This means that research not only has to pay attention to the types of risks that may involve children. It should also allow children to choose different subject positions to place themselves: as agents or as receivers, as mediators or advisors, etc.

The open-ended question in the EU Kids Online survey about what bothers children of their age received a higher refusal to response and led to more socially expectable responses, stressing sexual risks, violence and other negative contents of the media. Interestingly, risks related to commercial content were also pointed out, in spite of being less associated with the negative side of the internet in the adult discourse. As expected, due to the question itself, half of the answers represent the action of being bothering through reified relational processes, and the exclusion of self-identification is largely dominant. Although being a minority, self-inclusion illustrates the incorporation of regulatory orientations and the acknowledgement of public competences and responsibilities.

As discussed, the two questions on children’s safety strategies place the Escolhas respondents in higher active roles of exchange and activity. Not only have they included themselves as advisors, namely expressing personal commitment. They also represented the safe action using mainly active material and verbal processes that stress children’s conducts. Different reasons may be related to their low concern with contents: the influence of a less frequent internet access, which includes a filtered and monitored environment; instead of searching for new contents, a practice that implies higher informational skills, the preference for communicative practices among older users and their consideration that contact with unknown people may be an opportunity for enlarging their social capital; and a defensive and restricted risk-management expressed by younger users, avoiding the exploitation of the unknown in all its forms.

Among Escolhas, age differentiation is visible. Having less internet access at home and being more far from the online experience, younger children struggled more to answer the question on internet safety and some even expressed unexpected concerns. Among older respondents, differences regarding the EU Kids Online national sample are less evident and we may see some highly articulated answers and advice on online safety. Considering that they are beneficiaries of a national intervention program, it seems that their social and economic deprivation does not result necessarily in a digital exclusion.

This process of comparing and exploring children’s answers to the open-ended questions led us to acknowledge the relevance of the different ways of wording the issue of online risk and safety. Unexpected answers stressed the need of listening to children expressing their internet experience in their own terms. The hegemonic discourse on negative media contents clearly emerged in the question about online bothering; this visibility suggests the self-reproduction of a regulatory orientation and the children’s positioning as passive recipients. Distinctively, the questions on safety stressed the ambivalence of communicative processes such as talking, which intrinsically combines contact and conduct positions. It seems that respondents prefer to talk about their internet practices in a positive perspective, as someone who is recognized as competent and allowing for a more participatory role. This final note may be useful for research on children’s discourses on online experiences. Research supported in children’s own reports is needed for our (adult) understanding of their risk perceptions.

Notes

1. This project, led by Cristina Ponte (FCSH, UNL), José Azevedo (University of Oporto) and Joseph Straubhaar (UT at Austin) was funded by the UTAustin|Portugal Program. See http://digital_inclusion.up.pt (English version available).

References

Bernstein, B. (1974). Class, codes and control. London: Routledge.

Davison, W. P., (1983) The third-person effect in communication. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 47, 1-15.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse. Textual analysis for social research. London: Routledge.

Fowler, R. (1991). Language in the news. London: Routledge.

Haddon, L., & Ponte, C. (2012). A pan-European study on children’s online experiences: Contributions from cognitive testing. (OBS*) Observatorio, 6 , 239-257. Retrieved from: http://obs.obercom.pt/index.php/obs/article/view/579

Hodge, R., & Kress, G. (1988). Social semiotics. New York: Cornell Paperbacks.

Livingstone, S. (2009). Children and the Internet. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. J. (2007). Gradations in digital inclusion: Children, young people and the digital divide. New Media and Society, 9, 671-696.

Livingstone, S., & Haddon, L. (2009). EU Kids Online: Final report. LSE, London: EU Kids Online. Retrieved from: http://www2.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research.../EUKidsOnlineFinalReport.pdf

Livingstone, S., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2011). Disadvantaged children and online risks. LSE, London: EU Kids Online. Retrieved from: http://www2.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/...ShortReportDisadvantaged.pdf

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the internet. The perspective of European children. Full findings and policy implications from the EU Kids Online survey of 9-16 year olds and their parents in 25 countries. LSE, London: EU Kids Online. Retrieved from: http://www2.cnrs.fr/sites/en/fichier/rapport_english.pdf

Livingstone, S., & Haddon, L. (2012). Theoretical framework: the EU Kids Online project. In S. Livingstone, L. Haddon, & A. Görzig (Eds.), Children, risk and safety on the internet (pp. 1-14). Bristol, Policy Press.

Livingstone, S., Ólafsson, K., O’Neill, B., & Donoso, V. (2012). Towards a better internet for children: Findings and recommendations from EU Kids Online to inform the CEO coalition. LSE, London: EU Kids Online. Retrieved from: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/44213/1/Towards%20a%20better%20internet%20for%20children%28LSERO%29.pdf

Lupton, D. (1999a). Risk. London: Routledge.

Lupton, D. (1999b). Introduction: risk and sociocultural theory. In D. Lupton (Ed.), Risk and sociocultural theory: New directions and perspectives (pp. 1-10 ). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Paus-Hasebrink, I., & Bichler, M. (2008) Mediensozialisationsforschung. Theoretische fundierung und fallbeispiel sozial benachteiligte kinder. [Research on media socialisation. Theoretical basis and case study socially disadvantaged children]. Innsbruck: Studienverlag.

Ponte, C. (2012). Em família com a Internet? Acessos e usos dos meios digitais em famílias portuguesas [Living in family with the digital? Accesses and uses of digital media among Portuguese families]. Educação Online, 11, 1-29. Retrieved from: http://www.maxwell.lambda.ele.puc-rio.br/rev_edu_online.php?strSecao=input0

Ponte, C., Jorge, A., Simões, J. A., & Cardoso, D. S. (2012). Crianças e Internet em Portugal [Children and the internet in Portugal]. Coimbra: MinervaCoimbra.

Seiter, E. (2005). The Internet playground. Children's access, entertainment, and miss-education. New York: Peter Lang.

Simões, J. A., Ponte, C., & Jorge, A. (2013). Online experiences of socially disadvantaged children and young people in Portugal. Communications: the European Journal of Communication Research, 38, 85–106.

Thompson, G. (1996). Introducing functional grammar. London: Arnold.

Tourangeau, R., Ribs, L., & Rasinski, K. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tulloch, J., & Lupton, D. (2003), Risk and everyday life. London: Sage Publications.

Wynne, B. (1996). May the sheep safely graze? A reflexive view of the expert-lay knowledge divide. In S. Lash, B. Szerszinski, & B. Wynne (Eds), Risk, environment and modernity: towards a new ecology (pp. 44-83). London: Sage.

Correspondence to:

Cristina Ponte

Department of Communication

FCSH, New University of Lisbon

Av. de Berna, 26-C

1069-061 Lisboa

Email: cristina.ponte(at)fcsh.unl.pt