Performing for one’s imagined audience: Social steganography and other privacy strategies of Estonian teens on networked publics

Egle Oolo1, Andra Siibak2Abstract

Keywords: privacy strategies; social steganography; imagined audiences; social media; teens

Introduction

Today’s teenagers are being socialised into a society complicated by shifts between the public and the private (boyd, 2007a). The present day youth who often tend to consider social media, and social networking sites (SNS) in particular, as their space (see boyd, 2007a; Livingstone, 2008, Robards, 2010), sometimes mistakenly regard SNS as private places (Robards, 2010; Marwick, Diaz & Palfrey, 2010) similar to Instant Messenger (IM). In fact, it has been claimed (Marwick & boyd, 2010) that even though the imagined audience on social media is potentially limitless, young people tend to act as if the audience were limited. Furthermore, previous studies (such as Jensen, 2010; Siibak & Murumaa, 2011; Murumaa & Siibak, 2012) indicate that young people are not only often unaware of the omnopticon of social media, but many of the teens have not yet grasped the idea that our interactions on online platforms tend to be public-by-default and private-through-effort (boyd & Marwick, 2011). Hence, even though many authors (see Livingstone, 2008; boyd & Hargittai, 2010; boyd & Marwick, 2011; Janisch, 2011; Christofides, Muise & Desmarais, 2011; Davis & James, 2012) do not agree with the popular conviction that today’s youth do not care about privacy, such an assumption is often expressed by the public.

Although numerous comprehensive studies have been conducted on young people and their attitudes about privacy in networked publics, these studies have usually been focused on one particular platform, mainly Facebook (see Acquisti & Gross, 2006; Debatin et al., 2009; Raynes-Goldie, 2010; Sorensen & Jensen, 2010; boyd & Hargittai, 2010; Christofides, Muise & Desmarais, 2011; Siibak & Murumaa, 2011; Davis & James, 2012). Furthermore, the majority of these studies have made use of quantitative research methods (Acquisti & Gross, 2006; Debatin et al., 2009; boyd & Hargittai, 2010; Christofides, Muise & Desmarais, 2011) and have been based on a sample made up of high school (Youn & Hall, 2008; boyd & Hargittai, 2010; boyd & Marwick, 2011; Siibak & Murumaa, 2011) or college students (Acquisti & Gross, 2006; Tufekci, 2008; Debatin et al., 2009; Raynes-Goldie, 2010; boyd & Hargittai, 2010). Furthermore, most of the studies have been carried out with young people in North America (see Youn, 2005; Tufekci, 2008; Youn & Hall, 2008; Chai et al., 2009; Debatin et al., 2009; boyd & Hargittai, 2010; Marwick & boyd, 2010; boyd & Marwick, 2011; Davis & James, 2012 for the US, and Raynes-Goldie, 2010; Christofides, Muise & Desmarais, 2011 for Canada). Reliable up-to-date information on the privacy practices of European youth comes from the UK (e.g. Livingstone, 2008) and more recently from the project EU Kids Online (Livingstone et al., 2011).

Despite the fact that a lot of studies have been conducted on this topic in America, it is not possible to fully parallel these studies to European studies due to the differences of technological infrastructure, services available, cultural background, age of first starting to use the Internet etc. There is a shortage of qualitative studies presented in English that analyse European young people’s perceptions of privacy in the context of different text-based online communication environments. In addition, only a small number of studies so far (boyd & Marwick, 2011; Siibak & Murumaa, 2011) have aimed to gather knowledge about more complex strategies, e.g. social steganography, teens implement to protect their privacy. The present article aims to fill this gap in literature by offering an in-depth case-study of Estonian teens, cutting edge Internet users who have been found to encounter higher levels of risk concerning privacy (Livingstone et al., 2011). As researchers (Siibak & Murumaa, 2011; Murumaa & Siibak, 2012) have previously explored the perceptions of Estonian high school students about their online audience, this article aims to investigate the attitudes and practices concerning privacy among teenagers who are 13-16 years old.

We believe that as a “higher use, higher risk” and “new use, new risk” (Livingstone et al., 2011) country, where four in five children use the Internet daily (Livingstone et al., 2011: 33), Estonia offers an interesting case study on the topic of online privacy. Furthermore, according to the findings of EU Kids Online network, frequent Internet use is associated with a relatively high incidence of risk online, especially in terms of online privacy issues (Livingstone et al., 2011, p. 144). Privacy is a crucial topic when one considers that Estonian 13-16-year-olds are not only some of the most active SNS users in Europe (85 percent), but also some of the most active (50 percent) in contacting people, through SNS, that they have no connection with in their offline lives (Livingstone, Òlafsson & Staksrud, 2011). In comparison to the 9-16-year-olds in the UK (11 percent) or Ireland (12 percent), who are relatively active in implementing various privacy strategies, 29 percent of Estonian youth have kept their SNS profiles “public” (Livingstone et al., 2011, p. 39). Furthermore, Estonian teens are also quite eager (27 per cent) to publish private information, e.g. addresses and phone numbers, on their SNS profiles (Livingstone et al., 2011, p. 46).

Taking the above-mentioned context into consideration, semi-structured interviews with 13-16-year-old Estonians (N = 15) were carried out in spring 2011 with the aim of analysing the perceptions the young had about privacy and the imagined audience on online communication platforms, i.e. SNS, blogs and IM. We also aimed to explore a range of privacy strategies young people implemented in order to manage and navigate their overlapping extended audience, comprised of “ideal” and “nightmare” readers (Marwick & boyd, 2010). In addition to giving an overview of the main privacy strategies implemented by Estonian teens, the paper also focuses on thoroughly analysing the practices of social steganography used by Estonian youth (Siibak & Murumaa, 2011).

Theoretical Overview

Managing Privacy on Networked Publics

Researchers (e.g. Tufekci, 2008; Debatin et al., 2009; Sorensen & Jensen, 2010) agree that there are discrepancies between users reporting understanding the need for caution in regards to privacy and actually implementing these steps to safeguard their personal data. Furthermore, Acquisti & Gross (2006) have revealed significant discrepancies between privacy concerns and actual information-revealing behaviour in SNS. Although numerous researchers (Robards, 2010; boyd & Marwick, 2011; Janisch, 2011; Davis & James, 2012) today are convinced that teens value privacy, previous studies (Acquisti & Gross, 2006; Debatin et al., 2009; Siibak & Murumaa, 2011; Davis & James, 2012) indicate that many young users do not change their default privacy settings in SNS as they are either not aware of such a possibility, they consider changing privacy settings too time-consuming or they wish to refrain from being isolated in their desire to gain popularity.

In fact, the findings of studies carried out among college students provide a reason to suggest that the young believe the benefits of public participation outweigh the potential consequences of disclosing personal information (Debatin et al., 2009). The other possible reasons for generous information disclosure might lie in a not yet fully-developed sense of privacy, or teens being influenced by social media environments encouraging more disclosure (Christofides, Muise & Desmarais, 2011). Furthermore, young people sometimes tend to justify their views by claiming that they have nothing to hide (Siibak & Murumaa, 2011; boyd, 2008). However, rather than being totally careless about their audience, it should be noted that the young are not referring to the whole audience on SNS when making such claims, but rather that they “have nothing to hide from those Facebook users that are kept in mind while posting” (Siibak & Murumaa, 2011).

The latter statement is also supported by studies focusing on privacy issues related to communicating through IM. Although in IM environments privacy is easier to manage due to one-to-one communication and the text being ephemeral, existing only as long the session is active, young people still need to take into account the potential malicious users who can save or copy-paste the text elsewhere (Grinter & Palen, 2002). Even though a large number of sensitive teen conversations take place via IM (gossip, relationships, dating, personal conversations etc.), Grinter and Palen (2002) argue that young people are highly aware that IM conversations may be copied or distributed. For instance, the findings of their qualitative study among 15-20 IM users (N = 16) indicates that young people use various strategies, e.g. managing access regulation, not engaging in public chat, keeping profiles private, blocking certain people and publicising in their “buddy” lists their reasons for prolonged absences, so as to protect their privacy or avoid being interrupted.

Perceptions of Imagined Audience

Studies suggest that the list of “friends” the users have on SNS most often reflects very different social relations, ranging from “friendship” to random acquaintances, from strong to latent ties, stemming from a range of separate social contexts (boyd, 2007a; Debatin et al., 2009; Sorensen & Jensen, 2010; Livingstone et al., 2011). That also holds true for IM, as most young IM users tend to accept everyone as buddies and allow anyone to contact them (Grinter & Palen, 2002). In fact, the young appear to be far more concerned with people they know and who hold immediate power over them, e.g. parents, teachers and employers, viewing their profiles than complete strangers or abstract authorities (boyd, 2008; Livingstone, 2008; Marwick & boyd, 2010; boyd & Hargittai, 2010; Davis & James, 2012). For instance, the findings of Davis and James (2012, p. 12), who interviewed 10-14-year-old middle school students in the United States (N = 42), indicate that while 79% of their sample wanted privacy from strangers, 83% sought to maintain privacy from a “known other”, such as a parent, teacher, other family member or adult, and 67% named other young people, such as friends, peers, siblings and cousins, as their privacy targets. Furthermore, a survey carried out among American college students (N = 600) revealed that the majority did not consider it very likely that future employers, romantic partners or corporations would look at their profiles (Tufecki, 2008).

The above findings indicate that being visible to strangers is not a big concern for the young, apparently due to the illusion of anonymity the youth share online, i.e. they just do not expect strangers to have any interest in their posts and profiles (boyd, 2008; Murumaa & Siibak, 2012). In other words, young SNS users fail to acknowledge the existence of the Internet omnopticon (Jensen, 2010), where many people watch many others through various friendship ties or links. The potential risks teenagers may confront when failing to acknowledge their extended audience and unknown followers mostly involve stranger-danger, including (online) sexual harassment and (cyber) stalking or bullying. The risks also involve intimacy being revealed to teachers or parents and the resulting family disputes, embarrassment among peers, and situations where personal information published in one context might later cast doubt on them in other contexts (Youn & Hall, 2008; Chai et al., 2009; Harris, 2010; Janisch, 2011). In terms of the latter, Janisch (2011) refers to the possibility that a person may fail to get a job or a position in college because of having broadcast their youthful indiscretions online.

Even if young people do understand that the audience of Twitter or Facebook is potentially limitless, it has been argued (Siibak & Murumaa, 2011; Marwick & boyd, 2010: 7) that while compiling their posts and profiles the young mainly imagine their online audience to consist of “ideal readers”, i.e. their closest friends and online peers who usually represent “the mirror-image of the user”. For instance, focus-groups with 16-20-year-old high school students in Estonia revealed that the young saw their closest “friends” as the main audience of their Facebook posts, while the rest of their contacts and the overall online audience was almost completely forgotten (Siibak & Murumaa, 2011; Murumaa & Siibak, 2012).

Adapting to the Audience: Privacy Strategies

The uncertain range of audience and the unclear communication context pose new challenges to people who have to navigate in these changing contexts (Jensen, 2010). Studies (e.g. Youn, 2005; Tufekci, 2008; Robards, 2010; Marwick & boyd, 2010) indicate that social media users make use of various complex techniques in order to navigate their audience. In fact, Davis and James (2012) conclude that everyone in their sample (N = 42) of 10-14-year-olds used some online privacy strategies, and the majority of them (86%) combined proactive and withholding techniques. In the following section, we will provide an overview of the main privacy strategies used by teens.

Selective information sharing

Survey findings by Debatin et al. (2009) suggest that the most popular strategy American college undergraduates (N = 119) adopt when there has been an invasion of privacy is tightening their privacy settings, i.e. decreasing profile visibility through restricting access to “friends only”. These results are supported by Lenhart and Madden (2007), whose telephone survey of 12-17-year-old Americans indicated that 66% of the young said their SNS profiles were not visible to all users. In making information available but choosing to physically restrict it to people other than friends, young people are being “publicly private” (Lange, 2008, p. 369). In fact, several authors (Davis & James, 2012; boyd & Hargittai, 2010 et al.) claim that this is the most widely used proactive strategy by American tweens and college students.

However, considering the fact that the number of contacts people have in SNS and IM dramatically exceeds the number of contacts people have in traditional social networks, such a tactic can be viewed as a rather weak mechanism for protecting privacy (Debatin et al., 2009). Hence, although many of the young have started to make use of privacy settings, they still seem not to fully understand that their level of privacy protection in SNS is relative to the number of friends, their criteria for accepting friends, and the amount and quality of personal data provided in their profiles (Debatin et al., 2009, p. 102) or status messages in IM.

At the same time, studies suggest one also needs to be familiar with privacy settings in order to protect one’s profile (Debatin et al., 2009). For instance, a recent usability test among 13-17-year-olds (N = 31) in the UK, France and Germany revealed that many SNS users were only familiar with the standard privacy settings and did not use these technological capabilities to protect their privacy (Sidarow, 2011). For instance, Siibak and Murumaa’s (2011) respondents, aged 16-20, had knowledge of the blocking and erasing applications but were not aware of applications for chat for certain groups, being invisible for certain groups only or sharing posts and photos with certain people while excluding others. Inadequate experience and the limited user-friendliness of these settings have been mentioned as the main reasons why not all adolescents apply and modify them (Livingstone, 2008; Siibak & Murumaa, 2011).

Advanced strategic information sharing

Besides applying privacy settings, more innovative selective measures include “super-logoff”, i.e. temporarily deactivating a SNS profile every day after using the site, and “whitewalling”, i.e. deleting every comment after reading it in order to reduce the risk of misinterpretation, and to avoid searchability and persistence (boyd & Marwick, 2011; Janisch, 2011). Both of these above-mentioned techniques, however, are consistently used by very few people. For instance, just one person out of 163 informants boyd and Marwick (2010) interviewed said that they used “super-logoff” and just one claimed to be using “whitewalling”. Rather than engaging in IM chats, teens actively use the option of seeming to be offline to certain buddies by simply blocking them (Grinter & Palen, 2002).

Self-censoring information

Self-censorship is considered to be another useful technique that the young employ, especially if their online friends’ lists include “nightmare readers”, i.e. parents, employers and significant others (Marwick & boyd, 2010). According to Davis and James (2012), 90% of 10-14-year-olds in the US withheld content, such as personal contact information and inappropriate comments containing swear words or sexual content, from SNS and IM. Siibak and Murumaa (2011) have also pointed out that Estonian high school teens engage in self-censorship when their parents sign up on Facebook.

The findings of several studies (Marwick & boyd, 2010; Sorensen & Jensen, 2010; Davis & James, 2012) indicate that SNS users only post things they believe their broadest groups of acquaintances will find non-offensive, using the principle of “the lowest common denominator”. According to Sorensen and Jensen (2010), posts about one’s everyday life, small talk and phatic communication are considered to be safe to be uploaded online. At the same time, posts about dating, sexuality, relationships, serious illness, death, bodily functions, criticism and posts containing swearing or negative statements about individuals tend to be avoided on SNS (Marwick & boyd, 2010; Sorensen & Jensen, 2010; Davis & James, 2012) and only discussed in IM.

Multiple identities on multiple platforms and false information

The findings of various scholars from the US indicate that, in order to navigate the tensions of the extended audience, some SNS users either use multiple accounts, pseudonyms, nicknames and fake accounts (Marwick & boyd, 2010), or intensely insert false information on their profiles (Youn, 2005; Lenhart & Madden, 2007; Marwick, Diaz & Palfrey, 2010; Davis & James, 2012). For instance, a survey among 14-18-year-old Americans (N = 326) revealed 53% of the sample provided incomplete information, e.g. a false name, on SNS in order to handle potential risk associated with information disclosure (Youn, 2005). Canadian Facebook users in their twenties have been found to use aliases (Raynes-Goldie, 2010), or “mirror networks” (boyd, 2007b) to make it difficult for other users to find them via search engines or to attribute their SNS activities to their “real” identities. Likewise, many teens try to separate their friend groups from parents and peers through different communication channels (boyd & Marwick, 2011; Davis & James, 2012). Pseudonyms, nicknames and multiple accounts are even more frequently found in IM (Grinter & Palen, 2002), as they are easy to generate and renew.

Social strategies

However, as structural limitations are often ineffective, many young people use a different tactic to achieve social privacy: they limit the meanings of their messages (boyd & Marwick, 2011), because they wish their private space online to be public to their friends but private to their parents or other unwanted groups (Livingstone, 2008). Semi-structured interviews with high school students (N = 163) suggest that many girls have become accustomed to limiting access to meaning, but not limiting access itself (boyd & Marwick, 2011). This practice is called “social steganography” (boyd, 2010a) and can be defined as hiding information in plain sight. Social steganographic messages are communicated to different audiences simultaneously but are meaningless to the audience at large, as unlocking the meaning of that multi-layered message or post requires both recognizing multiple referents (boyd & Marwick, 2011) and specific cultural awareness to provide the right interpretive lens (boyd, 2010a).

When compiling such posts, teens usually make use of song lyrics and quotes so as to target their messages to particular users who possess the interpretive lens needed to decode the message (Siibak & Murumaa, 2011). Furthermore, while some young people choose to hide in plain sight, others post encoded messages intended as visible displays of inside jokes or “obscure referents” (boyd & Marwick, 2011, p. 22). Both of these practices can be characterized as being “privately public” (Lange, 2008, p. 372), making connections to many people while being relatively private with regard to sharing personal details. So far, the practice of social steganography has been detected only in a few studies (Siibak & Murumaa, 2011; boyd & Marwick, 2011), whereas in others no concrete evidence of such a practice has been found (Davis & James, 2012).

Method and Data

The Method

The data for the present study was gathered using the method of semi-structured interviews, which were conducted online via IM. This environment was chosen as, according to Clarke (2000), qualitative research methods should be carried out in natural environments. In the case of online socialization, the natural environment is the web. In addition to the fact that numerous researchers consider the web to be the most comfortable communication channel for e-savvy teens, we also believed that online interviews offered a valuable new modality for reaching out to a larger group of people concerned about issues of confidentiality and privacy (Clarke, 2000). As all our respondents were active IM users, we decided to carry out the interviews via MSN.

The interviews with the young respondents focused on three main topics. First of all, the respondents were asked to describe and analyse their own Internet usage practices, and then the conversation moved on to their perceptions of privacy and finally to the various privacy strategies they employed when communicating online. The interviews were carried out in Estonian, the mother-tongue of the respondents. The extracts used in the article were translated into English by the first author.

As every respondent had also given us a permission to observe their personal blog posts, tweets and SNS messages, the interviews were supplemented with the observation of their content creation practices, mainly so as to detect the potential usage of social steganography.

The interview transcripts were later analysed horizontally, combining the principles of cross-case analysis and the grounded theory approach described by Corbin and Strauss (1990). The occurred phenomena were flexibly given conceptual labels (open coding) and the labels were grouped into (sub)categories which formed (sub)themes (axial coding). Then, all relevant categories were unified around a core category (selective coding) and irrelevant codes were excluded. A literature search was carried out after all the empirical data was analysed and the core category, i.e. the main topic, had emerged.

The Sample

As the present study focuses on privacy issues when socialising online, the sample consists of Internet users by definition. Furthermore, as we aimed to study active Internet users, all the respondents had to use at least two different interpersonal online communication platforms of the proposed three – IM, SNS and blogs – in order to be part of the study. The gender distribution of the sample was balanced, and the age distribution was as varied as possible to avoid over-representation of certain segments.

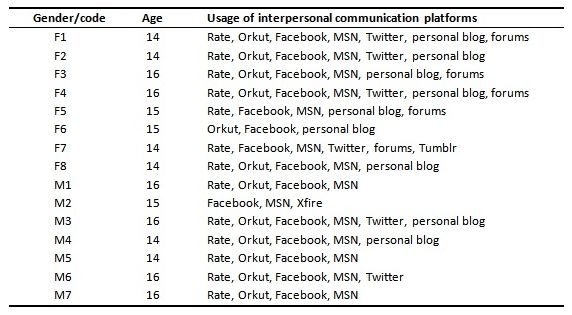

The final sample of the study consisted of 15 respondents 13-16 years of age, seven of which were males and eight females. Table 1 presents an overview of the respondents and their usage of interpersonal communication platforms. To protect the confidentiality of the respondents, only codes are used to mark the respondents.

communication platforms.

The respondents were found using snowball sampling, which means that existing subjects of the study helped to recruit further subjects among their acquaintances. The first informants were sought from the interviewer’s acquaintances and, at the end of the interviews, they were asked to suggest new informants.

As all of our respondents were active on a large array of online communication platforms, they were expected to possess a good understanding of practices and notions that characterise teens’ online information distribution.

Results

Teens’ Perceptions of the Online Audience

Our interviews indicate that the teens had quite a vague understanding of their imagined audience on networked publics. For example, although six of our respondents believed that their Facebook posts would be noticed by all the people in their friends’ lists, and possibly also by their “friends of friends”, reaching from 300 to 2000 (in one case, even 10 000) potential viewers, the teens confessed that they actually had no clue about the size of their Facebook audience.

If you post a message on Facebook, how large an audience do you think it will reach?

M4: In Facebook I know it will reach my friends and friends of friends. I’ve got more than 100 friends, but they could have God knows how many. So, maybe more than 10 000 people?

M5: Very large. It depends on how important the information is. For example, if I post about something crazy then maybe 2000 people. That’s actually not so large.

In contrast to the above-mentioned viewpoint, another six of the respondents were certain that their messages would reach only a fraction of their online contacts, assuming that the audience would probably range from one- to two-thirds of their friends’ list, i.e. about 40−125 users. Three additional interviewees were convinced that although their posts might reach a larger array of people, only the people in their closest friends’ circles would actually be interested in their posts. This assumption clearly derives from the fact that the young are used to receiving feedback only from those closest to them.

F1: Everybody will see it who happens to see it, but I don’t think anyone will have an interest in it besides my friends and acquaintances. It depends on the post, of course. But they are the ones to react, e.g. comment on it.

When it came to assessing the possible audience of their personal blogs and Twitter pages, the suppositions were more homogeneous. Although most of the studied bloggers claimed to keep blogs just for themselves, all the bloggers were aware of the fact that there was an audience keeping an eye on their posts. Furthermore, the interviews revealed that the teens felt motivated by having an audience and getting publicity.

Who are you blogging for? Who are the ones waiting for your posts and reading them?

F3: Most of my friends and everyone who finds the link to my blog. Every time I publish a new post, I tweet about it so that the followers will know.

So, the common understanding held by all the bloggers in our sample indicates that everyone who found their way to their blog and was interested in their writings was welcome because all of their blogs were public. Nevertheless, although the respondents believed they had followers whom they did not personally know, mostly friends, classmates and acquaintances were kept in mind when making the posts.

M4: Actually, I’m keeping the blog mainly for myself, so I can later check what I was up to on different days. But my audience is surprisingly large. There are a lot of foreigners − I also write in English. /…/ I would never talk about my worries in my blog because I’ve got a huge audience and /…/ everybody would change their minds about me. /…/ A blog is a very public place and it can reach anywhere.

Generally, the bloggers in our sample estimated their audience as being up to 33 people, with an average around ten. Although our interviewees stated that they did not discuss deeply personal worries on their blogs because of the potential presence of strangers, they admitted generously sharing their inner thoughts and emotions through a blog post.

Teens’ Perceptions of Privacy on Various Online Platforms

In addition to expressing personal opinions, our findings suggest that the young most frequently engage in small talk and chat about school-work, future plans and relationship issues when communicating online. These topics were discussed in all of the platforms under investigation. Of all of the platforms analysed, MSN was considered to be the best place for communication, from chitchat (questions like “What’s up?”) to talking about one’s worries, anxieties and gossip, as some associated the platform with a sense of privacy.

You want to talk to someone about your parents fighting. Where would you talk about it online and why?

M1: MSN, because it is the most private. I can talk to my loyal friend so that what we talk about won’t spread.

Several respondents, however, did not agree with the statement concerning the private nature of MSN as presented above. In fact, on some occasions, respondents thought the privacy levels of SNS (e.g. Facebook) and IM (i.e. MSN) were the same.

What differences are there between posting messages to different socialising platforms (e.g. Facebook and MSN)?

F1: The difference is that in MSN you’ll get the reply faster.

Do you think there are any differences in the level of privacy?

F1: Umm… I don’t think so. I think it’s the same.

Although the majority of the teens we interviewed preferred to use MSN for private discussions, they did not do it due to its high value on the scale of privacy but primarily because they perceived themselves as skilled users of the platform and enjoyed the swift responses they received from their communication partners, the majority of whom were also constantly logged onto MSN:

If you want to gossip about someone, where would you talk about it and why?

A.K: In MSN, because this is a relaxed environment and you can talk fast and simple there. /…/ chatting somewhere else is pretty uncomfortable and unfamiliar. MSN is really comfy and easy. I am really used to MSN, and that’s why it’s the best place.

When naming the differences between MSN and Facebook, some teens pointed out that in Facebook it is more difficult to get rid of the conversation history than in MSN, which makes MSN a safer place to talk about personal topics. Some respondents also mentioned having a larger number of contacts in SNS who were adults (teachers, parents, relatives, adult acquaintances, municipal government officials etc.) and random acquaintances than in MSN and admitted that this kind of extended audience made them act somewhat differently.

F3: Facebook is more “official”. Actually, it is a very public place and you can't really post there any kind of trash that's on your mind. That's what MSN is for - chatting one-to-one to someone and, if you feel really safe with someone, you can lose control and start blithering about stuff you're not supposed to. You wouldn't post that kind of stuff on Facebook.../.../ There, I keep myself pretty much under control.

As Facebook offers so many different ways of forwarding messages (instant chat, Wall posts, comments, likes and private messages); teens in our sample enjoyed using Facebook, especially because of its simultaneous private and public functions. For example, when the topic was not particularly private, teens preferred to express themselves as publicly as possible. Hence, uploading photos, sending invitations, sharing links, wishing someone “Happy Birthday” and informing people of scores on final exams were often done on public Walls. All our respondents, for instance, confessed wanting to post messages on their Facebook Walls so as to announce their big news, e.g. being accepted to a desired high school. This means that they really enjoyed the publicity and feedback such personal announcements would receive from their Facebook contacts.

In addition to making use of Facebook Walls for sharing personal messages, nine respondents had also set up personal blogs and six had accounts in Twitter, aimed at obtaining even more publicity. Although teens were unsure of the size and composition of their audience in the mentioned platforms, blogs were unanimously regarded as public platforms that could “reach anywhere” (M4).

“Performing” for One’s Audience

The respondents often perceived the imagined audience as being comprised of a relatively small part of the public – the precise group of people that they had in mind when they posted messages. However, as mentioned earlier, some interviewees pointed out that they also had adults and random acquaintances in their Facebook contact lists, because of whom they needed to “perform” differently. In the section below, we will introduce the three main privacy strategies – strategic information sharing, self-censorship and social steganography – our respondents used in order to preserve their privacy.

Strategic information sharing

When posting messages on Facebook or a blog, 13 of our respondents admitted performing somewhat differently than while chatting one-to-one with someone in MSN. One of the most common strategies the young use for maintaining their privacy on social media has to do with strategic information sharing.

The selection of the audience is carried out with the help of privacy settings. Although several of our respondents claimed that they did not want to share their personal information with strangers, not all of them had actually made use of the privacy settings the SNS offer. Even though most of the respondents hid their contact information and, in some cases, also their personal Wall posts, comments or photos from the general public, three of our respondents still made use of default settings and thus revealed all of their personal information to everyone.

F1: I don’t want to turn my profile private because, if I did, I would feel isolated from others :D

F2: I’d rather insert less information about myself than mess with the privacy settings.

Restricting access to personal blogs did not seem to be an option for any of the blog-keepers either, mainly because of the same reasons mentioned in the quotes above. Besides, blogs were set up to introduce inner thoughts and opinions, so it made no sense to write them down and then hide them from the public like a diary.

Self-censorship

The other most often practised privacy strategy for the teens involved self-censorship. Interviewees confessed the urge to think through their posts before uploading them on blogs and especially on Facebook. For example, they mentioned the need to be more polite and mindful of others, using proper grammar/vocabulary as well as being more selective of the topics to be posted on the Walls.

M6: When chatting with my friends and acquaintances in MSN, I am more relaxed. When communicating publicly on Facebook, I have to refrain from posting about anything that somebody wouldn’t want to read about themselves. As I have my municipal government director and many other adult acquaintances on my friends’ list, I have to be really careful not to be too straightforward.

It appears that adult acquaintances and relatives in their friends’ list were mainly kept in mind when thinking through the topics to be uploaded on their Facebook Walls. In the majority of cases, the teens refrained from bringing up very personal information, troubles and embarrassing moments.

F8: If I’m talking to my friend on MSN, it doesn’t matter how I express myself. But on FB, I think of the fact that it’s full of adult relatives.

And how do you form messages when keeping these adult relatives in mind?

F8: I don’t talk about dirty stuff and all the topics I would discuss with people my own age... I don’t write about what my aunts and uncles shouldn’t hear.

In general, the respondents considered their bodies, arguments, gossip, personal problems, accidents and failures, bad grades, quarrels with their families and more personal artwork (e.g. poems) to be too personal or even intrinsically private, to be uploaded on social media.

In contrast to SNS, the practice was implemented slightly more moderately in the blogosphere, as the obvious cues of adult readers were absent and the blogs were more determinedly deemed to be “my own space”, where their own rules held sway. Self-censorship was also not widely used in MSN, where conversations are mostly held with chosen trusted partners.

Sending hidden messages

Almost all of our respondents (14 out of 15) had noticed that their classmates, friends and acquaintances sent hidden messages and two-thirds of the sample confessed practising social steganography themselves. Four of the interviewees who practised this strategy at first claimed not to be using hidden messages. However, when presenting examples or analysing their Facebook, blog or Twitter posts that emerged from the observation of their profiles, they admitted the usage of social steganographic tricks. The observations were very useful in finding out if the respondents used hidden messages, as the practice seemed to be so entwined in the everyday information sharing practices of some of the respondents that they engaged in it almost subconsciously.

F3: I think I have [used social steganography], but not intentionally. For me, it comes automatically – for example, if you miss or think about someone, you might post some relevant lyrics to your blog almost subconsciously.

Social steganographic strategies were mostly used in the public sections of social media. In MSN, secret messages tended to be used in the section “Enter your personal message”, following the name of the user. On Facebook, the practice was mostly used when creating Wall posts, comments or photo captions. The respondents perceived social steganography to also be frequent on personal blogs and Twitter posts. Some respondents were eager to give examples of self-created hidden messages from their personal blogs during the interview, showing that secret messages were quite often posted in the blogosphere.

No matter on what platform the secret messages were posted, they were created in a relatively similar manner. To ensure that their friends and targeted audience could work out the “puzzles”, respondents made use of their common background knowledge, i.e. their “shared code”.

Can you give any personal examples of hidden messages from your profile or blog?

M3: “the lonely wolf was about to cry, because the birds never learned to fly” :D It seems like nonsense

When you posted the message, did you have anyone particular in mind?

M3: Yes :D I did. I knew that one certain person would get the point and others would just regard it as a meaningless rhyme /…/ Nobody was supposed to understand it besides one certain girl./…/ I had used the same sentence previously in our conversations /…/ so I KNEW she would understand. And she did :D

Generally, the respondents created their secret messages using expressions, inside jokes, keywords and citations from movies, games, songs or poems they had enjoyed together or used in their previous conversations, as noted in the quote above. These keywords turned into codes that required some knowledge of the context and/or an interpretive lens from the audience.

M6: Usually I use phrases that seem completely ordinary and bear no special meaning to people who aren’t supposed to understand. Targeted people will get it. There are no certain tricks, just inside jokes or repeatedly used jokes from a recent party /…/ which only a certain group of people have attended.

To create a bland surface for their messages, our respondents made use of different strategies. For example, they made generalisations, used abstract hints and changed their trains of thought so as to make the decoding of the message as complex as possible. Usually, they never mentioned any particular names when giving a hint to someone. In other words, our interviews indicate that teens often talk in circles, with the use of irony, lyrics or modified spelling. Such posts can thus be perceived as a secret language that will be understandable to only those members of the audience who have extra knowledge or those who possess an interpretive lens for decoding it.

The interviews with teens revealed that such secret codes were most often used for expressing romantic feelings. However, none of the teens in our sample were eager to admit using social steganography for the above-mentioned purpose; they just claimed to have perceived their friends doing such a thing.

F1: I have noticed that some acquaintances have uploaded a photo and added an aphorism of love as its heading that seems to be addressed to someone.

M1: I guess my lovesick friends have practised it. One of my friends has something like this written: /.../ “You are the air that I breathe. You are the water that I drink. You are the life that I live”. /.../ It is dedicated to a girl.

In fact, when it comes to communicating romantic feelings, 10 out of our 15 respondents confessed wanting to use social steganography rather than being forthright about their feelings. They believed lyrics or blog posts to be a perfect way to send a hint about their feelings to a particular person without letting everyone know the target of these feelings. Some respondents would click on the “Like” button of their love interests’ profile for exactly the same reason.

Secret messages are also often sent amongst peers on the theme of friendship and relationships in general. Why would teens want to hint at being friends with someone instead of saying it out loud? A girl (16) explains:

F4: It’s because if I was straightforward, what I said might psychologically hurt someone who found out that I wasn't writing about them or that I didn't consider them as important to me as this particular person [I wrote about].

In addition to positive emotions deriving from friendship, the respondents also generally expressed their disappointment and anger towards their peers when quarrels emerged or when companions hurt them.

F7: When a boy hurt my girlfriend, she posted “Life is great, isn’t it” as her MSN status. /.../ She didn’t want everyone to know that the guy had only been playing with her feelings. /.../ Only the people who knew about the situation with that guy understood that she was being sarcastic.

Nine of our respondents admitted having used social steganography every once in a while to express their emotions. Posting lyrics to communicate one's mood is one of the most common social steganographic tricks among teens because they are fluent in pop culture in a way adults are not. At the same time, such messages can be considered the easiest form of self-expression as they do not require much creativity: the message a teen wants to communicate is already there in the relevant lyrics, so one only has to find the right paragraph and post it. In addition to lyrics, a few of our respondents also made use of poetry and aphorisms when posting such messages.

F3: Once I posted rhymes; this is a paragraph from it: “The wind comes, I don’t know where from, don’t know where heading − /.../ I don’t understand, just feel alone.” The wind reminds me of a person who was in my life and was suddenly gone. I posted that poem on my blog about the same time. /.../

Another time, after an incident happened, I posted on Twitter: “This is all that I can take. Now I don’t care about you at all any more. Screw you!” Then, a reply appeared from the right person: “Don’t know if I am the one it’s written about...” and I didn’t even deny it.

When the respondents were asked to judge their skilfulness in creating such secret messages, girls of all ages were quite self-confident about their talent. Two older boys also agreed that they had mastered the art of forming hidden messages rather well, whereas three younger ones admitted not having relevant experience or interest in posting such messages. In fact, boys believed that such hidden messages were mainly created by girls.

M3: Mostly, teens with a higher interest in and understanding of literature and art use it /.../ Girls. Definitely girls :)

All in all, our findings suggest that, rather than masquerading on social media either by creating fake accounts on SNS or providing intentionally false information on their profiles, our respondents preferred to make use of social strategies for protecting their privacy. Giving out intensely false information was very seldom used as a privacy strategy by our respondents – only one respondent had provided false information about his age and none of the teens referred to having separate profiles to communicate to different audiences. None of the respondents engaged in deactivating their accounts or massive deleting of their posts either.

Discussion

It has been argued that young people’s tendency to generously reveal personal information, to create multiple identities and to communicate with strangers online illustrate the fact that they possess a fundamentally different understanding of privacy. The aim of this paper was to analyse Estonian teens’ perceptions about privacy and imagined audience on online communication platforms. The results of our study reveal that even though our respondents had misperceptions about the size of their audience and they were unaware of the true omnopticon of social media (Jensen, 2010), we cannot consider them to be easy-going or careless about privacy.

Our semi-structured interviews with Estonian teens indicate that our respondents were relatively at ease when communicating in IM, but did not consciously distinguish between the privacy factor in one-to-one communication platforms like IM and many-to-many online platforms such as SNS or blogs, which are more public in nature. Thus, in comparison to IM, misperceptions about the size of the audience on social media were ubiquitous. In the light of the interview results, we agree with Harris (2010, p. 77), who has stated that “Facebook and the like occupy some weird twilight zone between public and private information, rather like a diary left on the kitchen table”. The problems of distinguishing between the platforms may be explained by the fact that 13-16-year-olds are still relatively inexperienced users of social media who are more capable of managing “spatial” boundaries than abstract ones. Therefore, they are not totally aware of the threats that the persistence and searchability of new media can pose and cannot foresee that present choices may have consequences in the future, which was also the case with the American college students surveyed by Tufekci (2008). Although young people have a relatively good technical understanding of the Internet, their understanding of the social complexity of its use is somewhat lacking. At the same time, misperceptions of the online audience are also connected to the fact that the young are accustomed to receiving feedback only from their “ideal audience”.

Our results coincide with Siibak and Murumaa (2011) and Murumaa and Siibak (2012), who propose that Estonian students may sometimes fall victim to the illusion of Internet anonymity and the conviction that people outside their list of virtual friends will not have any interest in their activities and the messages they publish online. However, in contradiction to the findings of Siibak and Murumaa (2011), the informational privacy of our interviewees had not yet been breached, i.e. they had not experienced aggression towards one’s personal identity and, therefore, did not feel the need to worry too much about the possible threats to privacy. This lack of worry may also be connected to the third-person effect, meaning that the perceived risk to the privacy of others is greater than the perceived risk to one’s personal privacy (Debatin et al., 2009).

“Why would anyone want to upload that much personal information?” is a question that often puzzles parents and educators. The findings of our study lead us to conclude that having more privacy is not necessarily the most desired outcome for teens. For the young, being seen by those who they wish to be seen by, and in the ways they wish to be seen, are central motivations for using social media. In fact, as Tufekci (2008) has argued, young people see a certain level of self-presentation and self-disclosure as a must because they have their own expectations about levels of participation. And when it comes to privacy protection online, it emerged that the studied teens took these motivations into account and therefore implemented strategies that differed from those used by adult social media users.

Furthermore, we detected almost no usage of deception, aliases, super-logoff or whitewalling by Estonian teens, although many American researchers have noted that “security through obscurity” (boyd, 2007b) is believed to serve as an effective functional barrier by many SNS users. Our findings indicate that false information, regularly deactivating the account or deleting comments do not contribute to Estonian youth’s goal of self-definition and being visible online. In other words, they seem to be asking: why have a profile if it will not say enough about who you are? (Tufekci, 2008). Hence, instead of masquerading with multiple identities or deleting, the findings of this study suggest that Estonian teens prefer working on their unitary identity to multiple audience. However, the lack of alternative widely used social media platforms in Estonia also forces teens to stay on one platform and confront different audience segments simultaneously.

Considering the fact that privacy is dependent on one’s personal needs and choices about self- revelation (Westin, 2003, p. 6), we argue that one should not expect the young to implement the same privacy techniques as adults do. The findings of Debatin et al. (2010) suggest that tightening privacy settings is the most frequent privacy strategy American college students implement on SNS. However, our respondents seemed to believe that the benefits of generous and truthful public communication outweighed the potential negative privacy consequences. At the same time, the findings of other European studies (Sidarow, 2011; Siibak & Murumaa, 2011) indicate that the young may use the default settings because they underestimate the size of the audience and also lack the ability to limit access. The latter might also be the reason why the use of privacy settings in SNS was not widespread among our respondents, although most of them claimed that they did not want to share their personal information with strangers. In the light of the results by Debatin et al. (2010), we may hypothesize that the practices of our respondents will change when they grow older and have more knowledge of privacy concerns. At the same time, in addition to the possible impact of socio-demographics, we should not underestimate the differences in Estonian and American socio-cultural contexts, value systems and societal thought patterns, all of which may influence privacy practices.

Two of the most frequent privacy strategies used by Estonian teens are self-censorship and social steganography. According to Rachels (1975), in addition to choosing whether to share information, a right to privacy also includes the choice of with whom to share it. On social media where multiple audiences are blended into one (Marwick & boyd, 2010), young people are faced with a need to implement different social strategies so as to maintain their privacy, and by doing so also to maintain the variety of social relationships with their Facebook friends, blog readers or Twitter followers. The preference for hidden messages and self-censorship probably derives from the versatility of these techniques: both help the user to remain open to new connections and maintain a public identity while safeguarding the private sphere. The other options of setting up access restrictions, deactivating or whitewalling one’s profile could never serve such an important purpose for young people.

Our findings indicate that young people value and share the norms of contextual integrity described by Nissenbaum (1998). For instance, some of our respondents made extra efforts not to post messages about their relationships or bodies on their Facebook Walls, and preferred to chat about such private issues one-to-one through IM. Self-censorship was also often applied in terms of the language used when making posts on social media’s public sections. Our findings here coincide with Siibak and Murumaa (2011), who found that Estonian high school students self-censor their photos and messages when their parents sign up on Facebook. However, it is evident that the teens may still fall victim to the violation of contextual integrity as they only deal with protecting information of high intimacy rather than examining everything they post. What did not seem to be particularly private (e.g. a photo from a birthday party) in one context may not fit in another context at another time, e.g. applying to college or looking for a job.

Hence, similar to the findings of Siibak and Murumaa (2011), our results indicate that, rather than supporting total avoidance of private topics like love or relationships on networked publics, young people have found a way to target only “ideal readers” (see Marwick & boyd, 2010) with their posts. Given that teens are fluent in pop culture, slang and creating inside jokes (boyd & Marwick, 2011), these codes are cleverly used to construct secret messages. In a context where privacy techniques have been viewed as “an instrument for achieving individual goals of self-realization” (Westin, 1967, p. 39), we suggest that when implementing social steganography as a privacy tactic the young exercise their knowledge of peer and pop culture so as to leave “nightmare readers” (see Marwick & boyd, 2010) and unwanted followers in the dark. The creation of multi-layered messages might also be boosted by high self-esteem regarding the competence in (de)coding them, the prospect of minimizing the risks that emerge when being straightforward about one’s feelings or thoughts and the Estonian historical sociocultural context, which has encouraged the usage of double meanings.

Recently, Davis and James (2012) did not find evidence of the above-mentioned practice among 10-14-year-olds in the US. They explained this result by assuming that early adolescents might either be too young to possess the needed level of sophistication or the informants simply did not mention using hidden messages because they did not view these practices in privacy-related terms (Davis & James, 2012). We believe that the differences in the results lie in the methodology of the research and the way of formulating the questions during the interviews, as the studied age group partly coincides with ours and our findings indicate that 13-14-year-olds do have the ability to create secret messages. We detected the usage of hidden messages largely thanks to having access to the teens’ posts on their SNS profiles and blogs and therefore having access to examples of the usage. This allowed us to ask exceptionally specific additional questions and when no examples occurred in the respondents’ profiles, we decided to describe the phenomena in detail and provide the interviewees with examples of the practice that were probably not presented by other researchers. At the same time, the third-person effect could also be the reason why Davis and James (2012) were unsuccessful in detecting social steganography, as our informants also preferred to talk about social steganographic posts they had seen rather than created themselves.

Our findings give us reason to believe that, similarly to adults, privacy is a relevant concern for teens in Estonia. Although it is said that adults refrain from revealing information online by implementing more strict privacy settings, there are actually a lot of similarities between adolescents and adults in their privacy and disclosure behaviour. According to a study conducted by Christofides, Muise and Desmarais (2011), increased time spent on Facebook, higher need for popularity and lesser awareness of consequences increased the likelihood of disclosure for both groups. Thus we argue that young people hold the same privacy values as adults but use their own complex strategies for protecting privacy. As only a few studies so far (e.g. boyd & Marwick, 2011; Siibak & Murumaa, 2011) have explored the cutting-edge strategies teens use in networked publics, researchers and the general public have often been too hasty in concluding that young people make different value judgements concerning privacy. In fact, we believe that the public should start to acknowledge the fact that today’s online generation highly appreciates their individual rights regarding privacy.

However, what seems to cause problems is the way online danger is seen from different points of view. While adults associate the need for privacy with potential stranger-danger, the young consider direct authority figures as threats to their privacy. This was proved by our respondents revealing that, as “nightmare readers”, they kept adult relatives and acquaintances in mind when making their posts. Several authors (e.g. Davis & James, 2012; Harris, 2010) have expressed their concern that, because adults are in charge, most educational policy has focused on the narrow stranger-danger threat and such suggestions as “do not post anything personal online” and “do not talk to strangers”, which are not relevant for the young, as their privacy concerns extend to known others. We must realise that this probably discourages students from turning to their teachers for help, although, according to Chai et al. (2009), teachers have a great potential for positively developing their students’ digital literacy – including their repertoire of privacy strategies. We agree with Davis and James (2012) that the young need guidance in matters of social complexity, i.e. all the audience segments that may be present (now or in the future), how easy it is to produce, spread and search for information online, and how difficult it is to delete data once it has been posted. For instance, students need to be informed of the fact that SNS profile entries may negatively affect their chances when applying for college or jobs (Janisch, 2011). Hence, we propose that national curricula should include topics so as to ensure that all students became digitally literate.

Nevertheless, the generalisations presented here are made on the basis of the empirical data at hand. Furthermore, the limitation of having a relatively small and homogeneous sample did not allow us to differentiate between the young based on their socio-demographic background or to thoroughly analyse our results in the light of other studies. As some of the interviewees were friends or classmates and a precondition of the respondents was that they used two platforms under investigation, the sample was homogeneous, which may have caused over-representation of some insights and practices. A larger and more random sample that reflects demographic characteristics is needed to obtain representative results regarding Estonian teens.

Despite these limitations, we believe the study has contributed to the existing research by empirically showing that the general conviction of the contemporary online generation having profoundly different perceptions on safeguarding privacy and not caring for its protection might be superficial. Rather, we believe that teens’ social privacy strategies need to be studied more in depth as the young not only have skills which usually differ from those used by adults, but their desired privacy goals may also not coincide with those of adults. As there remains a lack of up-to-date research and case studies in this domain in Europe that are accessible in English, we believe that the present insights not only contribute to the knowledge of Estonian youth but have a wider relevance among European teens. Considering the fact that European adolescents share relatively similar Internet (privacy) practices (Livingstone et al., 2011), we believe the findings of this qualitative study help to highlight some tendencies that should be considered more carefully when assessing teens’ privacy practices in cultural contexts.

At the same time, we agree with Robards (2010), who has suggested that future research should explore online privacy strategies implemented by older age groups – adults and the elderly – in order to compare present day young people’s and their predecessors’ (social) privacy techniques. Consistent with Youn (2005), we believe there is also a need for additional research using individuals between the ages of 10-12 to examine age differences on this issue. In addition, long-term studies are needed to account for the growing complexity of online audience perception, friending and privacy strategies. Also, the aspect of self-efficacy, i.e. teenagers’ judgements of their abilities to apply and modify privacy settings and friending principles in IM were weakly analysed in the present study and should be incorporated in future studies. From the perspective of education, it would be useful to know who peers listen to and imitate in their practices – in other words, who has the most potential in contributing to their digital literacy and how instructions should be presented.

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this article was supported by research grant no. 8527 and the target financed project SF0180017s07 financed by the Estonian Science Foundation. Andra Siibak is also grateful for the support of the personal research funding project PUT44 financed by the Estonian Research Council.

References

Acquisti, A., & Gross, R. (2006). Imagined communities: Awareness, information sharing, and privacy on the Facebook. 6th Workshop on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, Robinson College, Cambridge University, UK. Retrieved from: http://petworkshop.org/2006/preproc/preproc_03.pdf

boyd, d., & Marwick, A. (2011). Social steganography: Privacy in networked publics. International Communication Association. Boston, MA. Retrieved from: http://www.danah.org/papers/2011/Steganography-ICAVersion.pdf

boyd, d., & Hargittai, E. (2010). Facebook privacy settings: Who cares? First Monday, 15(8), 13-20. Retrieved from: http://www.uic.edu/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3086/2589

boyd, d. (2007a). Social network sites: Public, private, or what? Knowledge Tree 13. Retrieved from: http://kt.flexiblelearning.net.au/tkt2007/?page_id=28

boyd, d. (2007b). Why youth (heart) social network sites: The role of networked publics in teenage social life. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, identity and digital media (pp. 119-142). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

boyd, d. (2008). Taken out of context: American teen sociality in networked publics. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. Retrieved from: http://www.danah.org/papers/TakenOutOfContext.pdf

boyd, d. (2010a). Social steganography: Learning to hide in plain sight. Retrieved from: http://www.zephoria.org/thoughts/archives/2010/08/23/social-steganography-learning-to-hide-in-plain-sight.html

Chai, S., Bagchi-Sen, S., Morrell, C., Rao, H. R., & Upadhyaya, S. J. (2009). Internet and online information privacy: An exploratory study of preteens and early teens. Professional Communication IEEE Transactions on, 52, 167-182.

Christofides, E., Muise, A., & Desmarais, S. (2011). Hey mom, what’s on your Facebook? Comparing Facebook disclosure and privacy in adolescents and adults. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 48-54.

Clarke, P. (2000). The Internet as a medium for qualitative research. Retrieved from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.99.9356&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13, 3-21.

Davis, K., & C. James. (2012). Tweens' conceptions of privacy online: Implications for educators. Learning, Media and Technology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2012.658404

Debatin, B., Lovejoy, J. P., Horn A.-K., & Hughes, B. N. (2009). Facebook and online privacy: Attitudes, behaviours, and unintended consequences. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 15, 83–108.

Grinter, R.E., & Palen, L. (2002). Instant messaging in teen life. Proceedings of the 2002 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work, November 16-20, New Orleans. Retrieved from: http://www.cs.colorado.edu/~palen/Papers/grinter-palen-IM.pdf

Harris, F. J. (2010). Teens and privacy: Myths and realities. Knowledge Quest, 39, 74-79.

Janisch, M. (2011). KEEP OUT! Teen strategies for maintaining privacy on social networks. The Four Peaks Review, 1, 49-59.

Jensen, J. L. (2010, October 19-21). The Internet omnopticon - Mutual surveillance in social media. Paper presented at the conference Internet Research 11.0: Sustainability, Participation, Action. Gothenburg, Sweden.

Lange, P. G. (2008). Publicly private and privately public: Social networking on YouTube. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13, 361–380.

Lenhart, A., & Madden, M. (2007). Teens, privacy and online social networks. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from: http://www.pewInternet.org/Reports/2007/Teens-Privacy-and-Online-Social Networks.aspx

Livingstone, S. (2008). Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: Teenagers’ use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media & Society, 10, 393–411.

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the Internet: The perspective of European children. Full Findings. LSE, London: EU Kids Online. Retrieved from: http://www2.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/eukidsonline/eukidsii%20%282009-11%29/eukidsonlineiireports/d4fullfindings.pdf

Livingstone, S., Ólafsson, K., & Staksrud, E. (2011). Social Networking, age and privacy. LSE, London: EU Kids Online. Retrieved from: http://www2.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/eukidsonline/shortsns.pdf

Marwick, A. E., Murgia-Diaz, D., & Palfrey, J. G. (2010). Youth, privacy and reputation (literature review). Harvard Public Law Working Paper 10-29. Retrieved from: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1588163

Marwick, A.E., & boyd, d. (2010). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13, 114-133.

Murumaa, M., & Siibak, A. (2012). The imagined audience on Facebook: Analysis of Estonian teen sketches about typical Facebook users. First Monday, 17(2). Retrieved from: http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3712/3147

Nissenbaum, H. (1998). Protecting privacy in the information age: The problem of privacy in public. Law and Philosophy, 17, 559-596.

Rachels, J. (1975). Why privacy is important. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 4, 323-333. Retrieved from: http://public.callutheran.edu/~chenxi/Phil315_062.pdf

Raynes-Goldie, K. (2010). Aliases, creeping and wall-cleansing. Understanding privacy in the age of Facebook. First Monday, 15(1). Retrieved from: http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2775/2432

Robards, B. (2010). Randoms in my bedroom: Negotiating privacy and unsolicited contact on social network sites. Prism, 7(3). Retrieved from: http://www.prismjournal.org

Sidarow, H. (2011). Usability tests with young people on safety settings of social networking sites. Retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/activities/social_networking/docs/usability_report.pdf

Siibak, A., & Murumaa, M. (2011). Exploring the 'nothing to hide' paradox: Estonian teens experiences and perceptions about privacy online. In: Proceedings of the A Decade In Internet Time: OII Symposium on the Dynamics of the Internet and Society, 21-24 September 2011, University of Oxford (pp. 1-18). Retrieved from: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1928498

Sorensen, A. S., & Jensen, J. L. (2010, October 19-21). Nobody has 257 friends: Strategies of friending, disclosure and privacy on Facebook. Paper presented at the conference Internet Research 11.0: Sustainability, Participation, Action. Gothenburg, Sweden.

Tufekci, Z. (2008). Can you see me now? Audience and disclosure regulation in online social network sites. Bulletin of Science Technology Society, 28, 20-36.

Westin, A. F. (1967). Privacy and freedom. New York: Atheneum.

Youn, S., & Hall, K. (2008). Gender and online privacy among teens: Risk perception, privacy concerns, and protection behaviors. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11, 763-765.

Youn, S. (2005). Teenagers’ perceptions of online privacy and coping behaviors: A risk-benefit appraisal approach. Journal of Broadcasting Electronic Media, 49, 86-110.

Correspondence to:

Andra Siibak

Institute of Journalism and Communication

University of Tartu

Lossi 36

Tartu

Estonia

Email: andra.siibak(at)ut.ee