Online Depression Communities: Does Gender Matter?

Galit NimrodAbstract

Keywords: online support groups, mental illness, coping, well-being

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2012), depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide, affecting 121 million people. Its symptoms include depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, feelings of guilt or low self-worth, disturbed sleep or appetite, low energy, and poor concentration. At its worst, depression can lead to suicide, associated with the loss of about 850,000 lives every year. Depression may be chronic and dispositional (endogenous), reflected in symptoms that endure for much of the lifespan, or a product of stress or saddening circumstances (exogenous) such as the loss of a job or a loved one. Nevertheless, even the milder and more transient forms can have debilitating effects on performance and quality of life.

The prevalence of depression and anxiety, as well as comorbidity – the occurrence of more than one disorder concurrently, is about twice as common in women than in men. There are multiple explanations for this difference, including gender roles, gender-based violence, and the interaction between biological and social vulnerability (Afifi, 2007; WHO, 2002). There are also gender differences in perceptions of distress and in patterns of healthcare seeking among those suffering from mental health problems. Women are more likely to recognize that they have an emotional problem than men with similar symptoms. In addition, women are more likely than men to seek help for a psychological problem by turning to family and friends and by using outpatient mental health services. Men may seek care at a later stage after the onset of symptoms, or delay until symptoms become severe (Biddle, Gunnell, Sharp & Donovan, 2004; Oliver, Pearson, Coe & Gunnell, 2005).

Men’s tendency to postpone help-seeking puts them at risk. While they consider the use of psychotropic drugs as indicating loss of autonomy, they tend to use alcohol and recreational drugs more than women. These may provide them with temporary relief from strain, but put them at an additional physical and psychological risk (Afifi, 2007; WHO, 2002). Another gender-related risk results from care providers. Doctors are more likely to diagnose depression in women compared to men, even when they have similar scores on standardized measures of depression or present with identical symptoms (Afifi, 2007). These two risk factors may explain why the rate of death by suicide is higher for men than for women in almost all parts of the world (WHO, 2002). Thus, women are at a greater risk for depression, and men, regardless of the causes, are at a greater risk for mistimed and inadequate treatment.

Depression may be successfully treated in a variety of ways, including the use of drugs and psychotherapy. Yet, less than 25 percent of those affected (and in some countries less than 10 percent) receive such treatments. Moreover, among those who receive treatment, 20 to 40 percent are resistant to it (WHO, 2012). Such findings lead depression scholars to recognize the importance of alternative techniques, particularly for the prevention of depression but also for “self-help” when it occurs (e.g., Wasserman, 2006; Neidegger, 2008). Online depression communities (i.e., online peer-to-peer support groups) may be considered as an alternative technique for those unable to receive treatment or resistant to it. Such communities may also complement treatment, and play an important role in motivating untreated and undiagnosed community members to seek professional help (Powell, McCarthy & Eysenbach, 2003).

Online communities operate through diverse applications – email lists, chat rooms, or forums/bulletin boards, but the latter seems to be the dominant technology. Compared with other immediate support alternatives (e.g., telephone hotlines) and face-to-face support groups, they have several advantages, including accessibility, anonymity, invisibility and status neutralization, greater individual control over the time and pace of interactions, opportunity for multi-conversing, and opportunity for archival search (Barak, 2007, Barak, Boniel-Nissim & Suler, 2008; McKenna & Bargh, 2000; Meier, 2004). These characteristics, along with availability, may explain why people with stigmatized illnesses, and in particular people with depression, turn to online communities for help in understanding and coping with symptoms (Lamberg, 2003).These characteristics may also make men more comfortable discussing their distress. The communities offer a unique variation of intimate communication that encourages greater participation by men and an opportunity to provide support for those depressed men who avoid the traditional mental healthcare system.

Online depression communities have grown into a mass social phenomenon estimated at dozens of such communities worldwide, with hundreds of thousands of members. Parallel to their increased prevalence, a growing body of research has tried to explore the communities’ potential role in the management of depressive disorders (for a review, see Griffiths, Calear & Banfield, 2009a; Griffiths, Calear, Banfield & Tam, 2009b). Existing studies of online depression communities explored three main issues: (a) members’ characteristics and participation patterns, (b) the contents posted in the communities, and (c) the impact of participation. However, relatively few of them have addressed gender issues. The following part of the literature review briefly describes the gender-related findings reported in previous studies of online depression communities with regard to each of these three main issues.

Members’ characteristics and participation patterns. Previous studies have been inconsistent with regard to the predominant gender reported. When gender was based on self-report among survey respondents (e.g., Houston, Cooper & Ford, 2002; Powell et al., 2003), members of online depression communities were found to be predominantly women. When gender was inferred from posts, studies reported more male users (e.g., Fekete, 2002; Salem, Bogat & Reid, 1997). Obviously, these differences are methodology-related, but they may also suggest that while men are a minority in the communities, they are significantly more active than women in their posting patterns. Yet, as Salem and colleagues (Salem et al., 1997) reported that the frequency of posting is equal for men and women, the difference may result from having a higher rate of lurkers (members who just read others’ posts) among women. Nevertheless, knowledge regarding the differences between male and female users of online depression communities in terms of their participation patterns, as well as in socio-demographics other than gender, is limited. Most studies simply refer to community members as a homogeneous group.

Contents posted in the communities. In recent years, several studies have utilized content analysis to examine messages posted in online depression communities. Most aimed to answer specific questions related to depression, such as the experience of taking anti-depressant medications (Pestello & Davis-Berman, 2008), or how suicidal identities are tested out, authenticated and validated (Horne & Wiggins, 2008). Salem and colleagues (Salem et al., 1997) examined gender differences and found that men made more experiential knowledge comments than women, and women made more group process comments than men did. Men were also more likely than women to use disclosure as a means of sharing experiential knowledge with other members. Hausner, Hajak and Spieb (2008) explored female-to-male ratio of requests for help in two online forums, English and German, and demonstrated that women were more likely than men to post requests for help. Their findings also indicated that the British forum had a significantly higher proportion of men than the German forum (compared to the expected rate in each country based on “sex ratio of regular Internet users” and “epidemiologically expected sex ratio”). The authors explained this difference by the fact that the website on which the British forum was held also included relevant mental health references and articles written by professionals. They claimed that men were more inclined to visit and actively participate in seemingly scientifically-oriented sites.

These findings are consistent with previous studies that identified gender differences in communication patterns within health-related online support groups (for review see Mo, Malik & Coulson, 2009). On the whole, these studies demonstrated that women tend to prioritize emotion-focused issues, whereas men focus largely on practical tasks and information. However, in studies that analyzed messages posted to mixed-gender support groups, these differences were less evident. A closer examination revealed that a group is likely to adopt the communication style of the predominant gender. This may imply that the gender differences in communication patterns result from social norms and expectations, rather than from different interests. In fact, it is possible that men and women share the same interest in issues discussed in the groups. However, none of the existing studies on online depression communities examined gender differences with regard to psychographic measures (such as motivations, interests and attitudes).

Impact of participation. A recent systematic review of the literature on online communities and depression (Griffiths et al., 2009a) has identified only two quantitative studies that focused on the clinical impact of online communities dedicated to people with depression. One of them indicated limited impact, demonstrating that a combination of Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) and online community was more effective in alleviating depression than community participation alone (Andersson, Bergström, Holländare, Carlbring, Kaldo & Ekselius, 2005). The second study indicated positive impact, reporting that women, people who work full-time and heavy users of the communities were more likely to have resolution of depression during follow-up than men, people who work part-time and less frequent users (Houston et al., 2002). The findings of this study suggested that women benefit more than men from participation in online depression communities. Nevertheless, the credibility of both studies is in doubt, as both did not apply randomized controlled trials of the effectiveness (Griffiths, Crisp, Christensen, Mackinnon & Bennett, 2010).

This clinical approach was harshly criticized by several scholars (Barak, Grohol & Pector, 2004; Barak et al., 2008; van Uden-Kraan, Drossaert, Taal, Shaw, Seydel & Laar, 2008), who objected to the application of particular therapeutic measurements in studies evaluating the effects of online communities. They claimed that separating the communities’ impact from other interventions was unrealistic and faulty, since none is a substitute for actual treatment; and that the communities should be viewed as complementary to professional care, as this means of emotional support can provide empowerment, stress relief and improved general well-being.

Support for this argument may be found in survey studies that investigated subjective variables such as the perceived benefits and/or the reason for participating in online depression communities. Houston and colleagues (Houston et al., 2002), for example, reported that emotional support was the main reason for participation, and that the majority of members agreed that participation alleviated their symptoms. Powell, McCarthy and Eysenbach (2003) found that most repeat visitors reported gaining knowledge of depression, and about half of them indicated that they were “able to discuss subjects that they felt unable to discuss elsewhere,” and that they “felt less isolated”. Similar findings were found in other studies (e.g., Alexander, Peterson & Hollingshead, 2003; Barak, 2007) which reported that members’ feedback was that the community provided them with help and understanding, an outlet for expression, and a place to turn to when alone, and that participation was a process that led to a sense of relief and a change in their lives. There is almost no evidence for perceived disadvantages of the communities (Griffiths et al., 2009b). While these studies provide substantial support for the positive impact of online depression communities on outcomes other than the level of depression, they lack differentiation among members. Hence, no study so far has examined whether the non-clinical benefits gained from participation vary among different segments of community members. Consequently, so far no study on online depression communities has examined gender differences with regard to their non-clinical benefits.

In summary, the existing body of knowledge on online depression communities lacks profound investigation of gender differences. We know very little about the differences in participation patterns and socio-demographics other than gender between male and female users of such communities. In addition, no study, thus far, examined gender differences with regard to the non-clinical benefits of participation, and none of the previous studies examined gender differences with regard to psychographic measures such as interests and motivations. Such investigation may be most helpful in understanding members’ participation patterns (c.f., Assael, 2005; Leung, 2003). In addition, just as in any other media use, it may be useful in explaining the benefits members gain from participation (Ruggiero, 2000).

The present study

The present study aimed to provide some of the missing information in the current body of knowledge. The main goal of this study was to explore gender differences in online depression communities. For that purpose, the study examined existing members of online communities, and combined an examination of members’ participation patterns (i.e., behavioral aspects) and psychological aspects. The latter included participants’ interests, perceived benefits, and level of depression. Hence, the study not only combined behavioral and psychological measures, it also combined clinical (i.e., objective) and non-clinical (i.e., subjective) measures of members’ well-being. Specifically, it was designed to answer the following questions:

1. Can men and women in online depression communities be differentiated using background characteristics (other than gender), level of depression, and participation patterns?

2. Are there differences among the groups in the interests they have in the issues discussed in the communities and the perceived benefits gained from participation?

3. Is there an association between the differentiating variables and the level of depression of community members? If so, do these associations vary for men and women?

By addressing these questions, the relationships between gender, members’ behavior and well-being were explored, and some general conclusions regarding the impact of participation in online depression communities on men and women were drawn.

Method

Data Collection and Sample

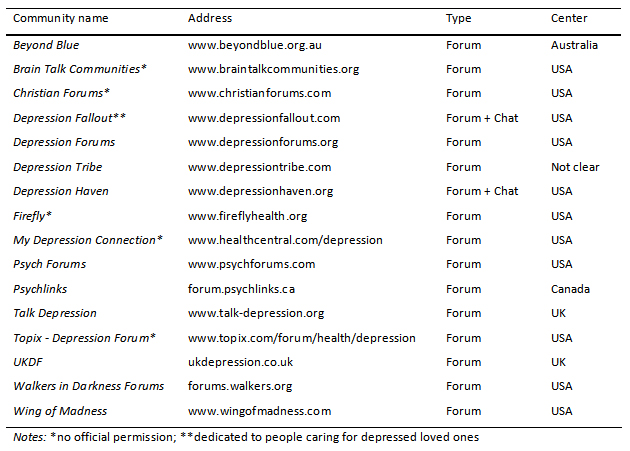

The study was based on an online survey of 793 members of 16 online depression communities. In order to recruit participants, the principal investigator (PI) contacted the administrators of 30 leading communities and asked for their permission to post a call for volunteers on their websites. The communities were quite homogeneous in their nature. All of them were established forum-based communities with many members and a large volume of daily activity. All of them aimed to provide peer-to-peer support for individuals in need, and they all enabled full anonymity. In addition, all the communities were English-language based and targeted global audiences. Eleven community administrators approved and even posted the call on the PI’s behalf, two said that they would examine the request but never answered, and one refused. Others did not respond even after three requests. In these cases, the PI independently posted messages in the communities. Of the 16 unauthorized messages posted, only five survived. Others were deleted by community administrators after a short period (between several hours to a couple of days) and the PI was banned. The remaining 16 (11 approved and five non-approved) communities surveyed are listed in Table 1. Yet, it is assumed that some respondents were recruited by the short-lived posts in the other 11 communities.

The call for volunteers included a short description of the research aims, and a link to the survey website (a survey-monkey application). The first page of the website included a longer description of the study, a consent form, and the PI’s contact information. Volunteers were asked to read the instructions and confirm their consent to participate. Then, they were asked to fill in an online survey. They were invited to contact the PI with regard to any question they may have, but none did. There were no sampling criteria and participation was anonymous. Therefore, the study was exempted from human subjects review. Data collection lasted two months, and ended when the questionnaire was filled by 1,000 people. After screening out those who did not sign the consent form (6% of the sample) and questionnaires with less than 80% of the questions answered (15% of the sample), the final sample size was 793. As the questionnaire was rather long, it is assumed that if there were any outliers in the sample, they were part of the group that did not bother to fill more than 80% of the questions. Therefore, they probably were not included in the final sample.

Sample Characteristics

Seventy percent of the sample participants were female and 30% were men. The sample included community members ranging in age from 12 to 71 years. Most were 20-50 years old, and the mean was 36 years (SD = 12.69). Forty-eight percent were single, 36% were married and most of the rest were divorced. The average number of years of education was 14.71 (SD = 3.22). Half of the respondents reported having average income and 35% reported income lower than average. Fifty-eight percent were from the US, 21% were from the British islands, seven percent from Canada, and six percent from Australia. Relatively few (8%) resided in non-English speaking countries. Regarding health, 50% perceived their health as good or excellent, and only 16% perceived their health as poor. Most respondents (75%) were diagnosed with depression. The most frequent diagnosis was major depression (72%), followed by bipolar disorder (15%) and dysthymia (5%). Depression scores ranged between 11 (least depressed) and 33 (most depressed), with a mean score of 24.09 (higher than 21 – the cutoff for depression).

Twenty-seven percent of the respondents were first-timers. Of those who were repeat visitors, 21% were relatively new members (less than a month) and 39% were “veterans” (more than a year). Thirty-five of the repeat visitors were “heavy users,” who visited their community every day or nearly every day, and 36% were “medium users” (at least once a week). Most repeat visitors (82%) reported being active (i.e., posting) at least to some extent, and 51% of the “posters” both opened new discussions and replied to others’ posts. Most respondents (92%) found the community either after intentional searching for online depression community or coincidentally, while surfing the web; and 34% reported visiting online depression communities other than the community from which they were referred to the survey. Only one percent learned about the communities from their therapists.

Measurement

The questionnaire included mostly closed and some open-ended questions regarding the following areas:

Participation patterns. The interview began with several general questions that examined how users learned about the community, and when they visited it for the first time. Additional questions looked at current usage patterns, including frequency of visits, posting behavior, and visiting other communities. Respondents were also asked to report if there were factors constraining their participation in the community, and if so, what they were.

Interest in issues discussed in the communities. Respondents were presented with a list of the nine main subjects discussed in the communities (Nimrod, 2012), including ‘symptoms’, ‘relationships’, ‘coping’, ‘life’, ‘formal care’, ‘medications’, ‘causes’, ‘suicide’, and ‘work’. They were asked to rate their interest in these topics using a four-point scale ranging from “have no interest” to “very interested”.

Benefits of participation. Respondents were presented with a list of 13 statements, which describe various benefits from participation in online depression communities. This list was based on the literature review (especially Alexander et al., 2003; Barak, 2007; Houston et al. 2002; Powell et al., 2003). Respondents were asked to rate the extent to which each of the statements described the benefits they gained from participation, using a five-point scale ranging from “totally disagree” to “totally agree.” Sample questions include items such as “I better understand my condition”, “I feel connected with others”, and “My condition is under better control”.

Level of depression. Depressive symptoms were measured by the Iowa short form (Kohout, Berkman, Evans & Cornoni-Huntley, 1993) of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), asking 11 of the original 20 questions with three rather than four response categories. This is a self-report instrument that asks respondents to describe their mood over the past week, on a 3-point frequency scale (1 = rarely or almost none of the time, 2 = some or a little of the time, 3 = most or all of the time). Sample questions include items such as “In the past week I felt depressed”, “In the past week I felt lonely”, and “In the past week, I enjoyed life” (reverse coded). The CES-D has been shown to be a reliable measure for assessing the number, types, and duration of depressive symptoms across racial, gender, and age categories. High internal consistency has been reported with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.85 to 0.90 across studies (Radloff, 1977).The Iowa short-form has been found to perform as satisfactorily as the original 20-item CES-D (Carpenter et al., 1998). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in this study was 0.87.

Background questionnaire. The last part of the interview included a background questionnaire with demographic and sociodemographic questions. The variables examined were: age, gender, perceived health, marital status, education, economic status, country of residence, having been diagnosed with depression (and if so, what the diagnosis was).

Data Analysis

The data was analyzed in five steps, the first being an examination of the differences between men and women in their background characteristics and participation patterns, using cross-tabulations and Chi-squared tests as well as T-tests. The next step included calculating the depression score for each respondent, and then the average for each group of users. Differences between the groups were examined by T-test.

For the purpose of data reduction, the third step was factor analyses that identified the structures of respondents’ interests and perceived benefits. The factor analyses were conducted on the interest data and on the perceived benefits data separately, using principal components extraction and Quartimax rotation with Kaiser normalisation. This rotation solution rotated the loadings so that the variance of the squared loading in each column was maximized, and provided a clear interpretation of the factors. To control the number of factors extracted from the data, a minimum eigenvalue of 1.0 was used with attributes loading at greater than 0.4. Each factor was interpreted and labeled, based upon each rotated factor loading, especially on the highest loading of each factor. T-tests were used to compare the mean scores of each group for the interests and benefits factors identified.

To examine the association between the differentiating variables and community members’ level of depression, the fourth step included a series of Pearson correlation tests. The last step of the analysis was linear regression, with all the differentiating variables as independent variables and with the level of depression as the dependent variable. To identify gender differences, tests in the fourth and the fifth steps were conducted separately for men and women. A confidence interval of 95% was used in all tests and only statistically significant findings are presented in this article.

Results

Differences between men and women in background, participation patterns and level of depression

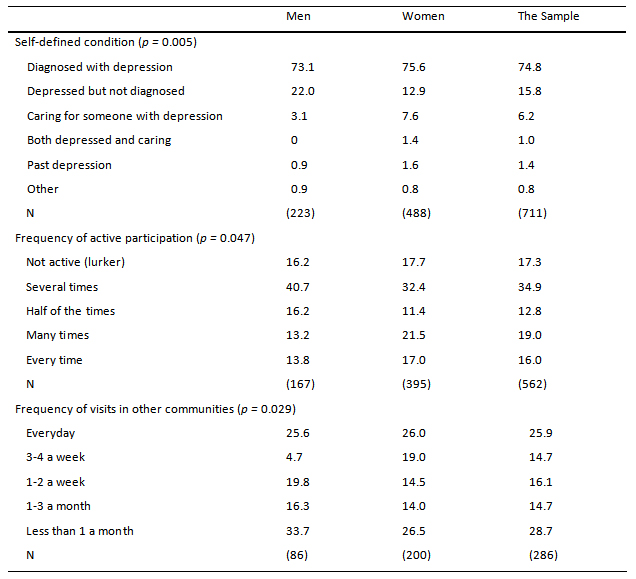

No differences were found between men and women in their socio-demographic characteristics (including age, economic status, education, family status, health perception, and country of residence). Similarly, no differences were found between men and women in their level of depression and type of diagnosis (among the diagnosed participants). However, there were significant differences (p = 0.005) in the self-defined condition, as more men than women reported being depressed but not diagnosed (22.0% vs. 12.9%).

Further analysis identified significant differences between men and women in the frequency of active participation and the frequency of visits in other online depression communities. Results indicated that female posters were significantly more active than male posters (p = 0.047), and among those who visited other communities, women visited them more frequently (p = 0.029). Results are presented in Table 2. No differences were found with regard to other participation patterns, including active participation (rate of posters vs. lurkers), type of active participation (open, respond, both), rate of participants who also visit other communities, rate of newcomers, membership duration, constraints on participation, and how users learned about the community.

Differences between men and women in interests and perceived benefits

The factor analysis of the interest data identified two factors that explained 54.5% of the variance. With the minimum factor loading level of 0.4, all interests were included in one of the factors and none were included in both. The first factor, labeled ‘living with depression,’ explained 40.7% of the variance and showed a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.738. It included issues related to general daily challenges such as “daily living with depression” and “coping with depression”, as well as more specific issues such as relationships, work and suicidal thoughts. The common characteristic of these interests was that they were all associated with daily living. The second factor, ‘information’, explained 13.8% of the variance and showed a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.730. It consisted of interests that were associated with knowledge regarding depression, such as symptoms and causes, as well as with practical information about formal care and medications.

Factor analysis of benefits data identified two factors that explained 65.3% of the variance. With the minimum factor loading level of 0.4, all benefits were included in one of the factors and four were included in both. The first factor, labeled ‘offline improvement’, explained 56.6% of the variance and showed a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.927. It included benefits that resulted from participation in online communities, but were reflected mainly in respondents’ personal lives (e.g., “My condition is under better control” and “I handle my relationships with others better”). The common characteristic of these benefits was that they were all associated with improvement in daily functioning. The second factor, ‘online support’, explained 8.7% of the variance and showed a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.891. It consisted of benefits that were associated with the online interaction itself (e.g., “I feel understood” and “I can share my difficulties with other participants”). Most of them were associated with social support. (For more information about this analysis see Nimrod, in press).

The results of the T-tests (see Table 3) indicated that women were significantly more interested in ‘living with depression’ than men (p = 0.002). No difference was found with regard to ‘information’. Analysis also showed that women reported significantly more ‘online support’ than men (p = 0.003). No difference was found with regard to ‘offline improvement’. Moreover, an examination of the correlations between the interest factors and the benefit factors revealed a significant correlation between the interest in ‘living with depression’ and the benefit of ‘online support’ among women. Pearson was .151 (p = 0.001, N = 481). Hence, the more interested women were, the more they experienced online support. Such correlation was not found among men.

Associations between interests, benefits, active participation and level of depression

The study examined not only gender differences, but also the associations between the main differentiating variables (i.e., active participation, interest in ‘living with depression’, and the benefit of ‘online support’) and the level of depression of community members. Because being diagnosed may overlap with the level of depression, and the frequency of visits in other online communities was relevant to a relatively small proportion of the sample, these two variables were not included.

Correlation between the interest in ‘living with depression’ and the level of depression was significant for women but not for men. Pearson was .135 (p = 0.002, N = 499). The more depressed women were, the more interested they were. Correlation between the frequency of active participation and the level of depression was significant for men but not for women. Pearson was -.254 (p = 0.001, N = 167). The more active men were, the less depressed they were. Similarly, correlation between the benefit of ‘online support’ and the level of depression was significant for men but not for women. Pearson was -.215 (p = 0.001, N = 220). The more men reported this benefit, the less depressed they were.

Correlation between the frequency of active participation and the benefit factor ‘online support’ was significant for both groups. Pearson correlations was.321 for men (p = 0.001, N = 156) and .280 for women (p = 0.001, N = 374). The more active members were, the more they reported ‘online support’. Similarly, the correlation between the interest in ‘living with depression’ and the frequency of active participation was significant for both groups. Pearson correlations was .223 for men (p = 0.001, N = 154) and .206 for women (p = 0.001, N = 369). The more members reported interest in ‘living with depression’, the more active they were. A graphic illustration of these findings is presented in Figure 1.

In the final linear regression, conducted separately for men and for women, the three differentiating variables (active participation, interest in ‘living with depression’, and the benefit of ‘online support’) were included as independent variables and the level of depression was the dependent variable. Among women, none of these variables predicted the level of depression. Among men, only the frequency of active participation predicted the level of depression: the Beta was .297 (p = 0.018; R2= 0.183, F = 3.255).

Figure 1. Associations between the main differentiating variables and the level of depression. p < 0.01 for all correlations presented. Higher depression scores indicate more depressive symptoms.

Discussion

Considering the sample size in this study, as well as the fact that sample characteristics were quite similar to those found in previous research (Griffiths et al., 2009b), this study seems to be quite representative of members of online depression support groups. It is the first study to examine gender differences in online depression communities by combining behavioral and psychological aspects. It is also the first to combine clinical (i.e., objective) and non-clinical (i.e., subjective) measures of members’ well-being. This combination provided some of the missing information in the current body of knowledge, produced a detailed understanding regarding online support group members, and may serve as a basis for several arguments regarding the impact of participation in online depression communities.

As the prevalence of depression is about twice as common in women than in men (Afifi, 2007; WHO, 2002), the female to male proportion in this study reflects their ratio in the general population in most parts of the world. Apparently, unlike offline help-seeking behaviors among those coping with mental health problems (Biddle et al., 2004; Oliver et al., 2005), there are no gender differences in turning to online communities. This may be explained by the anonymity and invisibility that these communities offer, along with their availability (Barak, 2007; Barak et al., 2008; McKenna & Bargh, 2000; Meier, 2004). Under these conditions, men probably find seeking help easier, and feel more comfortable discussing their condition and receiving support. The fact that there were no differences between men and women in their socio-demographic characteristics and level of depression strengthens this argument, as there were no other variables (e.g., education, income or higher level of depression) that could explain membership in online depression communities.

Despite the lack of differences with regard to turning to online communities, the study demonstrated several significant gender differences in members’ condition, involvement, behavior, and benefits resulting from participation. Overall, women were more interested in the issues discussed in the communities, specifically in ‘living with depression’. This may be explained by their tendency to focus on emotional issues (Mo et al., 2009). This higher level of interest may explain why they were also significantly more active posters, and even showed higher level of visits in online depression communities other than the community from which they were referred to the survey. Women also reported more benefits from participation, which probably resulted from their higher level of involvement, and had lower rates of undiagnosed depression, which may be explained by the fact that women are more likely than men to seek help for psychological problems by turning to formal care providers (Biddle et al., 2004; Oliver et al., 2005).

Men in this study had the same level of interest in issues related to ‘information’ (e.g., causes, symptoms, treatment) as women, but lower interest in ‘living with depression’. This is consistent with previous research on members of online depression communities (Hausner et al., 2008; Salem et al., 1997), as well as with previous studies of communication patterns within health-related online support groups, which showed that women prioritize emotion-focused issues, whereas men focus on practical tasks and information (Mo et al., 2009). The fact that men in this study reported less ‘online support’ than women is consistent with previous research as well, as Houston and colleagues (Houston et al., 2002) suggested that women benefit more than men do from participation in online depression communities. It is important to note, however, that there were no gender differences in reporting ‘offline improvement’. Hence, while participation itself is more rewarding for women, the perceived outcome is similar for men and women.

The findings regarding active participation contradicted a previous study, which demonstrated that the frequency of posting is equal for men and women (Salem et al., 1997). This may result from different methodologies, as the previous study was based on content analysis and the current study was based on self-report. These findings also negate the aforementioned suggested explanation for the inconsistent findings with regard to the predominant gender in depression online communities. Having more ‘lurkers’ among women could have explained the male dominance found in studies based on content analysis (e.g., Fekete, 2002; Salem at al., 1997). As this was not the case, the only explanation for the inconsistency is the different methodologies used.

Because the current study was not longitudinal, causality could not be examined. However, results indicated associations between interests, behavior, perceived benefits and depression. In fact, the study revealed gender differences not only in members’ interests, active participation and perceived benefits, but also in the associations between the main differentiating variables and the level of depression of community members. Although the correlations were relatively weak, they were significant and provided a solid ground for some general suggestions regarding the impact of participation in online depression communities on men and women. Among women, there was an association between their interest in ‘living with depression’ and the level of depression, and between that interest and the benefit of ‘online support’. This interest also correlated with active participation, which in turn correlated with ‘online support’ as well. Women’s greater benefits may thus be attributed, to some extent, to their greater interest and active involvement.

Men’s lower interest in the group processes and emotional issues may explain why they were less active and reported less ‘online support’ then women. It seems that their main motivation is receiving instrumental rather than emotional support, which appeared to work in their detriment. Just like among women, there was a significant association between active participation and ‘online support’ among men. In addition, unlike among women, there were also significant associations between ‘online support’ and level of depression, and between active participation and level of depression among men. These associations, along with the results of the regression model, suggest that active participation may be even more beneficial for men than for women. It may provide positive change not only in their general sense of well-being, but also in their clinical condition.

While only a longitudinal research could provide concrete support for this claim, it seems that using strategies for promoting active participation among men is likely to enhance the benefits they gain from the online communities. Such strategies may include familiar techniques such as having a visible and active moderator, using ‘ice-breakers’, offering mentoring partnerships, and even holding offline events to strengthen online relationships (cf., Bernstein-Wax, 2007; Schultz & Beach, 2004). However, new strategies may need to be developed exclusively for men, which would promote interest in the group and enhance emotional exchange.

The lack of differences among study participants in the level of depression, along with the higher proportion among men of members who reported being depressed but not diagnosed, are consistent with previous research that demonstrated that men tend to postpone help-seeking until symptoms become severe (Biddle et al., 2004; Oliver et al., 2005). However, as online depression communities play an important role in motivating untreated and undiagnosed community members to seek professional help (Powell et al., 2003), they may be the ‘first stop’ from which men continue to seek formal care. This may decrease the risks of mistimed treatment for men, including the use of alcohol and recreational drugs (Afifi, 2007; WHO, 2002). Hopefully, it may even decrease the rate of death by suicide that is currently higher for men than women (WHO, 2002). Anyhow, the findings of this study support previous claims (e.g., Barak et al., 2008; van Uden-Kraan et al., 2008) that the online depression communities may complement treatment and serve as an as alternative for “self-help” regardless of members’ gender.

Limitations and future research

Notwithstanding the strengths of this study, it has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First of all, there is an inherent bias in this sample – in favor of those who use the Internet and, more specifically, those who are willing to engage with others. This group might be less depressed than those who truly avoid any contact with others, and therefore not representative of people with acute depression. The bias also results from the fact that only 16 leading communities were examined in this study. Hence, the participants may be different from users of other leading depression communities as well as from small and possibly more intimate communities. In addition, despite a multi-national composition, most respondents lived in English-speaking Western countries. Moreover, since the present study was a cross-sectional study, only associations were examined and not causalities.

Future research, then, should investigate online depression communities using longitudinal methods. This includes longitudinal quantitative surveys that will examine causality and longitudinal qualitative interviews that will capture the perspectives of users over time. Future studies should also examine non-English communities to explore cultural variations. Because of the many benefits communities offer, further studies should also look for ways to promote participation among people with depression who do not visit online communities, and more active participation among men. With only 1% referred to the communities by their therapist, additional research should also examine professionals’ awareness and attitudes, and consider educational activities.

Acknowledgements:

The study was supported by a grant from NARSAD, The Mental Health Research Association. The Author wishes to thank research assistant Shirley Dorchin for help in preparing this article. In addition, the author thanks the administrators of the following communities for their collaboration: Beyond Blue, Depression Forums, Depression Haven, Depression Tribe, Depression Fallout, Psychlinks, Psych Forums, Talk Depression, UKDF, Walkers in Darkness, and Wing of Madness.

References

Alexander, S. C., Peterson, J. L., & Hollingshead, A. B. (2003). Help is at your keyboard: support groups on the Internet. In: L. R. Frey (ed.), Group communication in context: Studies of bona fide groups, 2nd edition, pp. 309-334. London, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Andersson, G., Bergström, J., Holländare, F., Carlbring, P., Kaldo, V., & Ekselius, L. (2005). Internet-based self-help for depression: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 187, 456-461.

Assael, H. (2005). A demographic and psychographic profile of heavy internet users and users by type of internet usage. Journal of Advertising Research, 45, 93-123.

Barak, A. (2007). Emotional support and suicide prevention through the Internet: A field project report. Computers in Human Behavior, 23, 971-984

Barak, A., Boniel-Nissim, M., & Suler, J. (2008). Fostering empowerment in online support groups. Computers in Human Behavior, 24, 1867-1883.

Barak, A., Grohol, J. M., & Pector, E. (2004). Methodology, validity, and applicability: A critique on Eysenbach et al. British Medical Journal, 328, 1166.

Bernstein-Wax, J. (2007). What motivates participation in online communities? Retrieved from: http://www.mediamanagementcenter.org/social/whitepapers/BernsteinWax.pdf

Biddle, L., Gunnell, D., Sharp, D. & Donovan, J. L. (2004). Factors influencing help-seeking in mentally distressed young adults: a cross-sectional survey. The British Journal of General Practice, 54, 48-53a.

Carpenter, J. S., Andrykowski, M. A., Wilson, J., Hall, L. A., Rayens, M. K., Sachs, B., & Cunningham, L. L. C. (1998). Psychometrics for two short forms of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies - Depression Scale. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 19, 481-494.

Fekete, S. (2002). The Internet - a new source of data on suicide, depression and anxiety: A preliminary study. Archive of Suicide Research, 6, 351-361.

Griffiths, K. M., Calear, A. L. & Banfield, M. (2009a). Systematic review on Internet Support Groups (ISGs) and depression (1): Do ISGs reduce depressive symptoms? Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11, e40.

Griffiths, K. M., Calear, A. L., Banfield, M., & Tam, A. (2009b). Systematic review on Internet Support Groups (ISGs) and depression: What is known about depression ISGs? Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11, e41.

Griffiths, K. M., Crisp, D., Christensen, H, Mackinnon, A. J., & Bennett, K. (2010). The ANU WellBeing study: A protocol for a quasi-factorial randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of an Internet support group and an automated Internet intervention for depression. BMC Psychiatry, 10. Retrieved from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/10/20/

Hausner, H., Hajak, G., & Spieb, H. (2008). Gender differences in help-seeking behavior on two Internet forums for individuals with self-reported depression. Gender Medicine, 5, 181-185.

Horne, J., & Wiggins, S. (2008). Doing being 'on the edge': Managing the dilemma of being authentically suicidal in an online forum. Sociology of Health & Illness, 31, 170-184.

Houston, T. K., Cooper, L. A., & Ford, D. E. (2002). Internet support groups for Depression: A 1-Year prospective cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 2062-2066.

Kohout, F. J., Berkman, L. F., Evans, D. A., & Cornoni-Huntley, J. C. (1993). Two shorter forms of the CES-D depressive symptoms index. Journal of Aging and Health, 5, 179-192.

Lamberg, L. (2003). Online empathy for mood disorders: Patients turn to Internet support groups. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289, 3073-3077.

Leung, L. (2003). Impacts of Net-generation attributes, seductive properties of the Internet, and gratifications-obtained on Internet use. Telematics and Informatics, 20, 107-129

McKenna, K. Y. A., & Bargh, J. A. (2000). Plan 9 from cyberspace: The implications of the Internet for personality and social psychology. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 4, 57-75.

Meier, A. (2004). Technology-mediated groups. In C. D. Garvin, L. M. Gutie’rrez & M. J. Galinsky (Eds.), Handbook of social work with groups (pp. 479–503). New York: Guilford.

Mo, P. K. H., Malik, S. H., & Coulson, N. S. (2009). Gender differences in computer-mediated communication: A systematic literature review of online health-related support groups. Patient Education and Counseling, 75, 16-24.

Nimrod, G. (2012). From knowledge to hope: Online depression communities. International Journal of Disability and Human Development, 11, 23-30.

Nimrod, G. (in press). Online depression communities: Participants' interests and perceived benefits gained. Health Communication.

Nydegger, R. (2008). Understanding and treating depression. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Oliver, M. I., Pearson, N., Coe, N., & Gunnell, D. (2005). Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: cross-sectional study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 297 -301.

Pestello, F. G., & Davis-Berman, J. (2008). Taking anti-depressant medication: A qualitative examination of Internet postings. Journal of Mental Health, 17, 349-360.

Powell, J., McCarthy, N., & Eysenbach, G. (2003). Cross-sectional survey of users of Internet depression communities. BMC Psychiatry, 3. Retrieved from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/3/19

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385-401.

Ruggiero, T. E. (2000). Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass Communication & Society, 3, 3-37.

Salem, D. A., Bogat, G. A., & Reid, C. (1997). Mutual help goes on-line. Journal of Community Psychology, 25, 189–207.

Schultz, N., & Beach, B. (2004). From lurkers to posters. Retrieved from: http://toolboxes.flexiblelearning.net.au.../lurkerstoposters.pdf

van Uden-Kraan, C. F., Drossaert, C. H. C., Taal, E., Shaw, B. R., Seydel, E. R., & Laar, M. A. F. J. van de (2008). Empowering processes and outcomes of participation in online support groups for patients with breast cancer, arthritis, or fibromyalgia. Qualitative Health Research, 18, 405-417.

Wasserman, D. (2006). Depression: The facts. New York: Oxford University Press.

World Health Organization (2012). Depression. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/definition/en/

World Health Organization (2002). Gender and Mental Health. Retrieved from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/gender/2002/a85573.pdf

Correspondence to:

Galit Nimrod, Ph.D.

The Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences

Department of Communication Studies, and The Center for Multidisciplinary Research in Aging

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

POB 653

Beer-Sheva 84105

Israel

Phone: 972-8-6477194

Fax: 972-8-6472855

Email: gnimrod(at)bgu.ac.il