Risky eBusiness: An Examination of Risk-taking, Online Disclosiveness, and Cyberstalking Victimization

Andrew Welsh1, Jennifer A. A. Lavoie2Abstract

Keywords: cyberstalking, routine activity theory, social networking, online disclosure

Introduction

Members of Generation Y have been identified as the fastest growing demographic among Internet users (Jones & Fox, 2009). Given the ubiquity of cyberspace for this demographic it is not surprising that one of the primary uses of the Internet for this group is social communication (Greenwood, 2009). The rapid expansion of online social networking sites (SNS) have increased social connectivity across peer groups while simultaneously raising concerns about privacy and risks for online victimization (Gross & Acquisti, 2005). Concerns stem from available empirical research suggesting that many SNS users do not restrict access to information on their profiles (Kolek & Saunders, 2008). The European Commission (EC), as part of the Safer Internet Programme, has similarly identified online disclosure as a risky online behaviour for young people (Donoso, 2011; Safer Social Networking Principles of the EU, 2009).

Other researchers have noted that SNS users exhibit a lack of awareness of the risks for online victimization associated with Internet social communication and online disclosure of information (Bugeja, 2006; Kornblum & Marklein, 2006; Marcum, Ricketts, & Higgins, 2010). Further, past research has identified links between Internet use and various forms of online victimization among children, youth, and young adults, including cyberbullying (Ybarra, 2004), pedophile contact and grooming (Beech, Elliot, Birgden, & Findlater, 2008; Briggs, Simon, & Simonsen, 2011), sexual solicitation, and exposure to unwanted sexual materials among adolescents and young adults (Mitchell, Finkelhor, & Wolak, 2007; Ybarra, Mitchell, Finkelhor, & Wolak, 2007).

Other streams of research have asserted that the incidence of cyberstalking has similarly increased among college and university students (Barak, 2005; Bocij, 2003; Finn, 2004; Lee, 1998; Olsen, 2002). To date, no study has directly examined the relationship between the sharing of personal information on SNS, or online disclosiveness, and the risk for cyberstalking. Cohen and Felson’s (1979) Routine Activity Theory argues that the risk for victimization increases when suitable or attractive targets are in close proximity to motivated offenders in the absence of effective guardianship. From this theoretical perspective, individuals who frequently use the Internet to interact with and meet new people while disclosing a great deal of personal information with few restrictions may be increasing their risk for victimization. The general purpose of this study was to investigate whether levels of online disclosure could account for the risk of cyberstalking using Routine Activity Theory as an explanatory framework. To provide a sufficient background of the relevance of this study to the larger research on cyberstalking, several issues are discussed including: (1) information-sharing and privacy on SNSs, (2) an overview of the general empirical literature on cyberstalking, and (3) a review of extant research on RAT and cybercrime.

Social Networking Sites and Privacy

A social networking site (SNS) refers to an Internet website where users can establish virtual identities through the creation of profile pages, containing a range of personal information, that can be linked to other users’ profile pages (Boyd & Ellison, 2007; Lenhart & Madden, 2007). Presently, most SNSs allow people from diverse backgrounds to connect to a global cyber-community with few boundaries. A typical Facebook profile allows users to share a diverse range of information including contact information, personal demographic information such as gender, birth date, hometown, academic concentration, personal interests, relationship status, name of partner, and political affiliation.

This ease of connectedness and accessibility of personal information has raised concerns about privacy and personal safety. Among Generation Y youth and young adults, online social networking has always existed and has evolved to become an essential form of communication among peers (Junco & Mastrodicasa, 2007). Some critics claim that this familiarity has resulted in a disconnect between perceptions of privacy, the permanency of shared information on the Internet, and personal safety (Barrett, 2006; Hass, 2006). Indeed early research suggested that SNS users revealed a considerable amount of personal information. Gross and Acquisti (2005) reported that among a population of 4000 university students, 860 student Facebook profiles disclosed both current residence and at least two classes being attended. Similarly, Govani and Pashley (2007) found that 60% of student profiles on a social networking site at an American university contained a profile image, birthdate, relationship status, and American Online (AOL) Instant Messenger (AIM) screen name. While early SNSs provided privacy options, default settings typically left personal profile information largely accessible (Gross & Acquisti, 2005). Problems with the laxness of early privacy setting controls were compounded by an indiscriminate willingness of SNS users to accept friend requests and a general lack of awareness of these default privacy settings (Govani & Pashley (2007).

Concerns over privacy and online disclosure have resulted in recent efforts to improve privacy setting controls for SNS users (e.g., Safer Social Networking Principles of the EU, 2009). Facebook has made numerous changes to privacy settings over the last several years, providing users with the ability to scale privacy settings to allow selected personal information to be viewed by different social network categories. Today a Facebook user can allow the public to see their general profile information while limiting access to other personal information based upon personally determined friendship categories. However, the expansion of privacy controls on some SNSs has led to a vast range of customizable settings thereby creating a potential for confusion among users while default privacy settings often still leave personal information publicly accessible (see Boyd & Hargittai, 2010).

More recent research examining privacy settings and online disclosure does show that the implementation of privacy settings has increased (Boyd & Hargittai, 2010). Hinduja and Patchin (2008), for instance, found that 40% of surveyed youth set their profile information to private, limiting the accessibility of personal information to those approved as friends. Yet there is still variability in findings from the emerging literature. Numerous factors may influence online disclosure and the use of privacy settings including friend network size (Lewis, Kaufman, & Christakis, 2008; Stutzman & Kramer-Duffield, 2010), gender (Boyd, 2008, Lewis et al., 2008; Stutzman & Kramer-Duffield, 2010), frequency of SNS use and proficiency (Boyd & Hargittai, 2010), and perceptions of privacy and privacy concern (Boyd, 2008; Livingstone, 2008; Raynes-Goldie, 2010; Young & Quan-Hasse, 2009). Two important findings emerge from this research. First, extant research shows that a number of SNS users may still share a great deal of personal information thereby likely increasing personal risk for victimization. Second, the research indicates that there is individual variability in online disclosiveness that could potentially serve to mediate the risk for online victimization.

Cyberstalking

Similar to traditional stalking, the term cyberstalking does not refer to a homogenous social phenomenon but rather describes a range or pattern of interrelated behaviours. A form of online or cyberharassment, attempts to pinpoint a specific meaning for cyberstalking are further complicated by its conceptual overlap with cyberbullying (Jameson, 2008/2009). Although the two terms have been used interchangeably, cyberbullying and cyberstalking have often been distinguished based upon age demographic with the former referring to a type of cyberharassment involving children and youth and the latter describing forms of cyberharassment among adults (Campbell, 2005; Jameson, 2008/2009; Miller, 2006).

In his research on patterns of cyberstalking, Spitzberg and his colleagues (Spitzberg & Rhea, 1999; Spitzberg, Marshall, & Cupach, 2001) have identified three major categories of cyberstalking that vary in their level of seriousness: Hyper-Intimacy, Threat, and Real-Life Transfer. Aspects of Hyper-Intimacy may include repeated, unsolicited efforts at cyber-communication with the victim, sending tokens of affection, giving exaggerated messages of affection, or sending pornographic messages. The second cyberstalking aspect, Threat, refers to online invasions of privacy and may include intimidating e-mails or text messages, and various forms of electronic sabotage, such as spamming or sending viruses (Bocij, 2002; Burgess & Baker, 2002; Finn, 2004; Finn & Banach, 2000; McGrath & Casey, 2002; Spitzberg & Hoobler, 2002). Third, Real-Life Transfer refers to physical intrusions into the victim’s life that have emerged from initial online encounters including being followed or physically harmed by a person who the victim originally met online.

Studies on the prevalence of cyberstalking generally suggest that the rates of victimization are low with more commonly experienced forms of cyberstalking being relatively minor in nature (Alexy, Burgess, Baker, & Smoyak, 2005; Finkelhor, Mitchell, & Wolak, 2000; Fisher, Cullen, & Turner, 2002). Spitzberg and Hoobler (2002), for instance, reported that 18% of 232 undergraduate students had received sexually harassing messages, but only 3% of students had been threatened by someone they had initially met online. Similarly, Bocij (2003) reported that a third of survey respondents had experienced at least one of 11 distinct cyberstalking behaviours. Finn (2004) found that 10% to 15% of respondents in a sample of 339 U.S. undergraduate students reported receiving repeated e-mail or Instant Messenger messages that “threatened, insulted, or harassed,” and more than half of the students received unwanted pornography. The extent to which cyberstalking victimization results in contact-related behaviours is unclear. In the ‘offline’ stalking literature, research has generally reported that approximately a third of stalking cases involve physical violence (Meloy, 2003; Blaauw, Winkel, Arensman, Sheridan, & Freeve, 2002) with most reported violence being minor in nature (Rosenfeld, 2004). Some research suggests that physical contact between the cyberstalker and victim is similarly rare (Pittaro, 2007.

A third major area of inquiry in cyberstalking literature has investigated whether cyberstalking represents a distinct social problem from traditional stalking behaviors (e.g. Bocij &McFarlane, 2002) or whether electronic media merely provides an extension of such behaviour (e.g., Burgess & Baker, 2002; Meloy, 1998; Ogilvie, 2000). The rationale underlying the argument that cyberstalkers are distinct has rested on the assumption that the Internet and the expansive opportunities it offers to monitor and contact individuals may prompt stalking behaviour from people who would otherwise not engage in such behaviour in face-to-face social settings (Finn, 2004; McGrath & Casey, 2002). While some studies have identified differences in stalking patterns between cyberstalkers and traditional stalkers (Lucks, 2004), other studies suggest that the Internet merely provides stalkers with an additional means to exert control over victims, Sheridan and Grant (2007) found that only 7% of self-reported stalking victims indicated that they solely had been stalked online. While nearly half of these participants had received an e-mail from their stalker, the majority of respondents were harassed in the real-world. Regardless of whether cyberstalking represents a unique behavior or merely represents another form of traditional stalking, existing research on information-sharing and privacy on SNSs and research on patterns of cyberstalking suggest that online disclosiveness could potentially increase the risk for cyberstalking.

Risk-Taking and Information-Sharing on the Internet

The Routine Activities Theory (RAT), developed by Cohen and Felson (1979), offers a potentially useful framework for conceptualizing the link between user activities on SNSs, online disclosiveness, and cyberstalking. Other scholars have identified RAT as a useful theoretical framework for understanding various forms of cybercrime (e.g., Bossler & Holt, 2009; Grabosky & Smith, 2001; Holt & Bossler, 2009; Newman & Clarke, 2003; Pease, 2001). Briefly, according to RAT, the risk for criminal victimization is influenced by our daily activities with three factors contributing to individual differences in victimization: motivated offenders, suitable targets, and effective guardianship. The concept of a motivated offender is broad and refers to any individual with both the intent and the means to commit a crime. The second factor, target suitability, refers to whether an individual is both available as a victim and is desirable to the motivated offender. Capable or effective guardianship refers to the ability of an individual to prevent a crime from occurring (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Levels of online disclosure or the extent to which individuals limit accessibility to online personal information would be an illustration of effective guardianship in an online social networking context.

In spite of the potential suitability of employing RAT to explain the risk for online harassment, some scholars have expressed scepticism about the theoretical relevance of RAT to cybercrime. Generally, RAT emphasizes the importance of physical proximity, drawing links between the amount of time spent in public domains and the risk for any particular form of victimization (Mustaine, & Tewksbury, 1999). For example, an individual who spends a great deal of time in nightclubs during peak times of usage is typically at greater risk than an individual who spends his or her evenings in their personal residence. According to Yar (2005), the theoretical construct of proximity poses specific problems for the application of RAT to cybercrime. Specifically, Yar argues that online environments are spatially and temporally disconnected such that virtual environments exist continually across the globe regardless of user activities, thereby limiting the relevance of daily lifestyle routines.

While Yar (2005) believes that the a-spatial characteristics of the Internet present different victim-offender relationships limiting the applicability of RAT to cybercrime, other scholars have disagreed with this assessment (Alshalan, 2006; Bossler & Holt, 2009; Yucedal, 2010). Yucedal (2010), for example, suggests that the level of risk for victimization on the Internet is not equivalent for all users. Specifically, Yucedal has suggested the Internet be conceptualized as a “place”, somewhat akin to a series of neighbourhoods, where users do in fact engage in different activities and face different risks. The risks of online victimization while checking e-mail or browsing a reputable news site are undoubtedly different than the risks associated with downloading materials from a pornographic website or posting in an online chatroom. We find this particular view instructive as a theoretical guide for examining the relationship between online disclosiveness and risk for cyberstalking. The rapid growth and expansion of SNSs illustrate that the Internet has increasingly become a social environment where users interact with one another in a variety of ways, thereby influencing their level of risk.

Few studies have directly examined risk-taking behaviours and the risk for general or “offline” stalking. Across the few existing studies, factors relevant to target suitability and proximity to motivated offenders have been linked to the risk for stalking. Fisher, Cullen, and Turner (2000) reported that rates of stalking victimization were higher among younger female college students who lived alone, dated frequently, and had a propensity to be in places with alcohol. Mustaine and Tewskbury (1999) found that several lifestyle factors influenced the risk for stalking victimization among female college students including drinking and drug use, employment status, and residential location. These findings suggest that lifestyle behaviours that increase exposure to motivated offenders are important predictors of stalking. Measures of guardianship behaviors and the risk for stalking victimization are mixed. Mustaine and Tewksbury found that women who employed protective measures, such as carrying mace, experienced higher rates of stalking victimization. They argued that these self-protective measures might in fact be a response to past stalking victimization rather than antecedents of stalking. Another possibility is that guardianship efforts do not directly impact victimization but rather act to mediate the relationship between target suitability, proximity to motivated offenders, and the risk for victimization.

The application of RAT to cyberstalking has been similarly neglected in the literature. Nevertheless, links between the concepts of RAT and risk for various cybercrimes have been identified. Hidujua and Patchin (2008) found that the amount of time spent online increased the risk for cyber-bullying among adolescents. Bossler and Holt (2009) found that risk-taking or deviant behaviours online increased exposure to motivated offenders thereby elevating the risk for malware infections. Interestingly, Bossler and Holt reported that engaging in online guardianship behaviours, such as password management, did not reduce the threat of malware victimization. Similarly, Holt and Bossler (2009) discovered that spending more time in online chatrooms and engaging in deviant activities online increased the odds of online harassment. Most recently, Marcum, Ricketts, and Higgins (2010) found that the disclosure of personal information online and engaging in online communication activities (e.g., Instant Messaging, chatrooms) increased the likelihood of various forms of online victimization (e.g., exposure to unwanted sexually explicit material, harassment, unwanted sexual solicitation). Consistent with the findings reported by Bossler and Holt (2009), Marcum and her colleagues (2010) reported that online guardianship efforts failed to have a consistent impact of the risk for victimization. Some guardianship efforts, such as monitored Internet use, served as a protective factor for Internet users. Comparatively, the use of protective software did not reduce the risk of victimization.

Taken together, there is some preliminary support for the ability of the theoretical concepts of RAT to account for online victimization, including cyberstalking (Bossler & Holt, 2009; Hidujua & Patchin, 2008; Holt & Bossler, 2009; Marcum et al., 2010). Factors that increase exposure to potential offenders (e.g., using social communication sites such as Instant Messaging, chat rooms) and increase target suitability (e.g., viewing pornography, pirating software and media, hacking) appear to elevate the risk for online victimization. No previous research has specifically examined how RAT might account for links between SNS use and cyberstalking as a specific victimization outcome. Furthermore, the small body of existing research on RAT and cybercrime has reported mixed findings on the effectiveness of guardianship efforts. No previous research has looked at guardianship efforts that might specifically protect users on SNSs from cyberstalking, such as online disclosiveness, and whether such efforts directly influence victimization or serve as a mediator between lifestyle activities and the risk for victimization. As such, the general purpose of this study was to build upon the growing research literature and examine the utility of RAT as an explanatory framework for the risk of cyberstalking. Specifically, the present study investigated whether online disclosiveness, or the protection of personal information online, would mediate the relationship between aspects of online activity, such as exposure and risk-taking, and cyberstalking. The following questions were examined:

1. Does an increased exposure to SNSs increase the risk for cyberstalking victimization? This question pertains to the proximity component of RAT and its ability to account for cyberstalking risk.

2. Does an increased willingness to disclose personal information on SNSs increase the risk for cyberstalking victimization? Online disclosiveness, or a willingness to share personal information, measures the guardianship component of RAT and its ability to account for cyberstalking risk.

3. Do risk-taking traits that increase target suitability contribute to the risk for cyberstalking victimization? Domains of personal risk-taking pertain to the target suitability component of RAT and its ability to account for cyberstalking risk.

4. Do online guardianship efforts (i.e., online disclosiveness) mediate the relationship between online exposure and risk-taking traits on the risk for cyberstalking victimization?

Method

Participants

A total of 390 participants provided data for this study. Participants were undergraduate students at a small university campus in Southern Ontario, Canada. Two convenience sampling approaches were used to recruit participants. Most participants were students in an introductory psychology class who volunteered for the study to fulfill a course research requirement. Other participants were recruited through classroom advertisements requesting participation in exchange for $5.00. Participants were informed that they would be participating in a study of risk factors for negative online experiences associated with the use of SNSs on the Internet. The majority of participants were female undergraduate students (83.8%, n = 327). Participants’ ages ranged from 17 to 51 years (M = 20.03, SD = 4.23) and most participants indicated they were Caucasian (88.2%, n = 343). Given established gender differences in prevalence and experience of stalking victimization (Meloy, 1996; Zona, Sharma, & Lane, 1993), as well as the high proportion of females in the sample, analyses for the present study focused solely on female participants who indicated that they used online SNSs on a regular basis (n = 321).

Measures

Online Exposure. To assess “proximity” to potential offenders (Cohen & Felson, 1979), a measure of Online Exposure was developed for the study. Participants were asked to indicate how frequently they used the Internet for 17 different online activities (e.g., email, social networking) on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Never, 5 = Always). Possible total scores ranged from 17 to 84, with higher scores indicating greater levels of Internet usage. Mean Online Exposure scores indicated a moderate level of proximity to online risk among study participants (M = 31.24, SD = 5.69, range: 19-50). Internal reliability for this measure was adequate (Cronbach’s α = .71).

Online Disclosure. Guardianship, which refers to the ability of people or objects to protect themselves against criminal acts (Cohen & Felson, 1979), was measured with a self-report Online Disclosure scale developed for this study. Participants were asked to indicate on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Very unlikely, 5 = Very likely) how likely they would be to reveal 24 different forms of personal information on a social networking Internet site (e.g., e-mail address, course schedule, personal images of alcohol consumption). Possible total scores ranged from 24 to 120, with higher scores indicating higher levels of online disclosure. Participants in the sample exhibited moderate levels of Online Disclosure with personal information (M = 73.64, SD = 14.72, range: 29-110). Internal reliability for this measure was very good (Cronbach’s α = .89).

Risk-taking. Target suitability refers to whether an individual is both available and desirable as a victim to a potential offender (Cohen & Felson, 1979). A general dispositional measure of risk-taking, the 30 item Domain-Specific Risk-Taking (DOSPERT) Scale (Blais & Weber, 2006, Weber, Blais, & Betz, 2002), was used to evaluate the likelihood with which respondents might engage in risky behaviours across five discrete domains (Ethical, Financial, Health/Safety, Recreational, and Social). Ratings for each item are made on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Extremely Unlikely, 7 = Extremely Likely). Each domain is comprised of six items. Scores are aggregated across items of each domain to obtain subscale scores each ranging from 6 to 42. Higher scores indicate greater risk-taking in the domain (Blais & Weber, 2006). Internal reliability for the five subscales in the present sample ranged from adequate to good (Cronbach’s α = 0.71 to .85). Analyses of the DOSPERT risk-taking domains indicated that in the present study mean levels of risk-taking were highest in the Social domain (M = 29.68, SD = 6.57) compared to the other domains (t’s ranged from 37.01 to 14.01, all p’s < .001)1. Mean levels of risk-taking among the Recreational (M = 22.63, SD = 9.45) and Health/Safety (M = 21.99, SD = 7.19) domains did not significantly differ, t = 1.41, p > .05, but both were significantly higher than the Ethical and Financial domains, t’s ranged from 14.32 to 22.92, all p’s <.001.2 The lowest mean levels of risk-taking were reported in the Ethical (M = 14.58, SD = 6.51) and Financial (M = 14.19, SD = 6.31) domains.

CyberStalking. The Cyber-Obsessional Pursuit (COP) Scale is a 24-item scale developed by Spitzberg and colleagues (Spitzberg & Rhea, 1999; Spitzberg et al., 2001). The scale is designed to measure the extent of an individual’s experiences of cyber-obsessional pursuit, or online stalking victimization. Participants were asked to indicate the frequency with which they have experienced 24 forms of cyberstalking on a five-point scale (1 = Never, 5 = Over 5 Times). Total scores range from 24 to 120, with higher scores indicating an increased frequency of experienced cyberstalking. The COP consists of three subscales: Hyperintimacy (six items, e.g., exaggerated messages of affection), Real-life transfer (five items, e.g., meeting first online and then following you), and Threat (seven items, e.g., sending threatening messages), each demonstrating moderate to good internal reliability (α ranging from .74 - .88; Spitzberg & Hoobler, 2002). Mean scores on the COP subscales were highest for the Hyper-Intimacy scale (M = 13.49, SD = 5.69), followed next by the Threat scale (M = 9.81, SD = 3.37), and then by the Real-Life Transfer scale (M = 6.02, SD = 1.89). A series of three paired t-tests indicated that these means differences were significant [t’s (df = 319) ranging from 26.80 to 14.40, all p’s <.001). Internal reliability for COP subscales ranged from adequate to good (Cronbach’s α ranged from .73 to .85).

Results

Statistical Analyses

According to Baron and Kenny (1986), mediation is said to exist when the influence of the independent variable (IV) on the dependent variable (DV) is explained after controlling for the effect of the IV on the mediator and the effect of the mediator on the DV. Statistical evidence of meditational effects can be established by estimating a series of regression equations showing that: 1) the IV predicts the DV; 2) the IV predicts the mediator; and 3) the mediator predicts the outcome in a model controlling for the effects of the IV (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Testing and discussion of the mediation analyses is organized into the following three sections: (1) Analysis of the relationship between the IVs and the three types of cyberstalking victimization outcomes, (2) Analysis of the relationship between the IVs and the mediator variable, and (3) Analyzing the relationship between the IVs, mediator and DV.

Step 1 – Analyzing the Relationship between the Independent and Dependent Variables

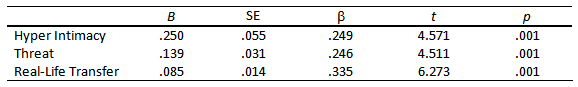

Three sets of multiple linear regressions were conducted to examine the relationship between the IVs (Online Exposure, Online Disclosure, DOSPERT risk-taking domains) and the COP scales measuring cyberstalking victimization. First, a series of standard multiple linear regression models were conducted to determine whether online exposure was predictive of each of the three forms of cyberstalking victimization. Each of the COP subscales was independently regressed on the Online Exposure scale total scores. Prior to conducting analyses, assumptions underpinning the use of multiple regression including multicollinearity, normality, linearity, homoscedasticity, and multivariate outliers, were tested. A total of two cases were excluded for the model predicting Threats, and five outliers were excluded from the model predicting the experience of Real-Life Transfer. Results indicated that Online Exposure was significantly associated with all three cyberstalking victimization outcomes. Online Exposure positively predicted Hyper-Intimacy, R2 = .06, Radj2 = .06, F (1, 317) = 20.90, p <. 001; Threat, R2 = .06, Radj2 = .06, F (1, 316) = 20.346, p < .001, and Real Life Transfer, R2 = .11, Radj2 = .11, F (1, 313) = 39.36, p < .001 (See Table 1).

A second series of standard multiple linear regression models were estimated to determine whether Online Disclosure was predictive of cyberstalking victimization. Each of COP subscales were separately regressed on Online Disclosure scale total scores. Two cases were excluded for the model predicting Threats, and six outliers were excluded from the model predicting the experience of Real-Life Transfer. Results indicated that online disclosure was significantly associated with all three cyberstalking victimization outcomes. Online Disclosure positively predicted Hyper-Intimacy, R2 = .09, Radj2 = .08, F (1, 315) = 29.81, p < .001; Threat, R2 = .20, Radj2 = .20, F (1, 315) = 79.56, p<.001; Real-Life Transfer, R2 = .16, Radj2 = .16, F (1, 310) = 60.71, p < .001 (see Table 2).

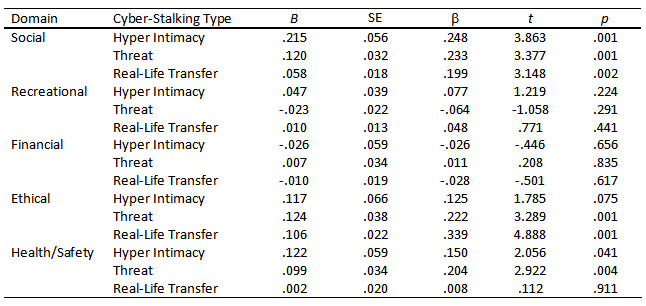

A third series of standard multiple linear regression models was conducted to determine whether the risk-taking domains of the DOSPERT were predictive of each of the three forms of cyberstalking victimization. Each of the COP subscales was independently regressed on the set of five DOSPERT domains. A total of four outliers were excluded for each of the three analyses. As hypothesized, all three regression models indicated that risk-taking was predicting of COP victimization scores. In the first regression model in which Hyper-Intimacy victimization scores were regressed on all five DOSPERT domains was statistically significant, R2 = .21, Radj2 = .19 F (5, 299) = 15.55, p < .001. As shown in Table 3, two of the five DOSPERT domains (Social, Health/Safety risk-taking) significantly contributed to the model. Similarly, the model regressing Threat scores on the five DOSPERT risk-taking domains was significant, R2 = .26, Radj2 = .25 F (5, 300) = 21.38, p < .001, such that Social, Ethical and Health/Safety risk-taking domains significantly contributed to the model. Consistently, social and ethical risk-taking domains were predictive of Real Life Transfer scores, R2 = .23, Radj2 = .21 F (5, 300) = 17.49 p < .001.

Step 2 – Analyzing the Relationship between the Independent and Mediator Variables

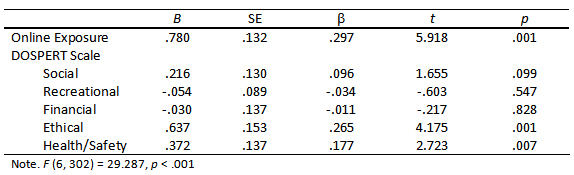

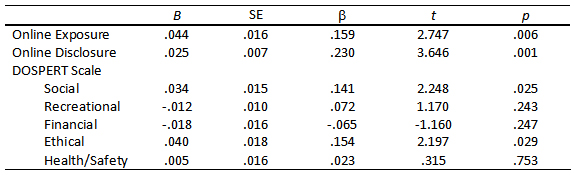

At Step 2, a standard multiple linear regression was conducted to determine whether Online Exposure and the five domains of risk-taking of the DOSPERT were predictive of Online Disclosure. Online Disclosure scale scores (DV) were regressed on the Online Exposure total scale scores and the set of five DOSPERT risk-taking domain scale scores (IVs). Four outliers were excluded from the analysis. Regression results indicated that the overall model significantly predicted Online Disclosure, R2 = .37, Radj2 = .36, F (6, 302) = 29.287, p < .001. A summary of regression coefficients is presented in Table 4 and indicates that two of the five domains of risk-taking as measured by the DOSPERT (Ethical, Health/Safety) significantly contributed to the model predicting Online Disclosure. Online Exposure did not contribute to the model.

Step 3 – Analyzing the Relationship between the Independent, Mediator, and Dependent Variables

To test whether Online Disclosure mediated the relationship between the IVs and cyberstalking victimization , three multiple regression models were estimated in which each of the three cyberstalking victimization outcomes (DV) were independently regressed on the five risk-taking domains and Online Exposure (IVs) simultaneously with Online Disclosure (mediator). Specifically, a series of standard multiple linear regression models was conducted to determine whether the full model of variables was predictive of each of the three forms of cyberstalking victimization. Each of the COP subscales was independently regressed on the total scale scores for Online Exposure, Online Disclosure, and the five DOSPERT risk-taking domains. A total of four outliers were excluded from the models predicting the experience of Hyper-Intimacy and Threats, and seven cases were excluded for the model predicting Real-Life Transfer.

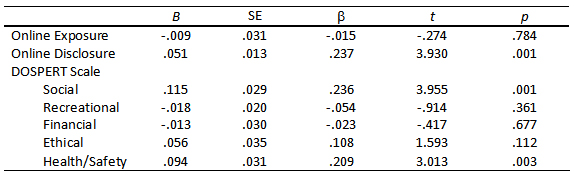

The first regression model in which Hyper-Intimacy victimization scores were regressed on all model variables was statistically significant, R2 = .22, Radj2 = .20 F (7, 299) = 11.72, p < .001. A summary of regression coefficients is presented in Table 5 and indicates that only one of the five DOSPERT domains of risk-taking (Social) significantly contributed to the model. Contrary to expectation, neither Online Exposure nor Online Disclosure significantly contributed to Hyper-Intimacy COP scores. The second regression model in which Threat scores on the COP scale were regressed on the full model of variables was also significant, R2 = .32, Radj2 = .31 F (7, 300) = 19.81, p < .001. As shown in Table 6, Online Disclosure and the Social and Health/Safety risk-taking domains on the DOSPERT all significantly contributed to the model. Finally, in the second regression model, the full set of model variables was predictive of Real Life Transfer scores, R2 = .28, Radj2 = .26 F (7, 297) = 15.71 p < .001. Online Exposure and Online Disclosure were both significant contributors in the model. Additionally, Social and Ethical risk-taking were the only significant contributors of the five DOSPERT risk-taking domains (see Table 7).

Discussion

The general purpose of the present study was to address the ability of the theoretical concepts of RAT to account for the risk for cyberstalking. More specifically, we sought to determine whether online disclosiveness, an online guardianship effort, would mediate the effects of target suitability and proximity to motivated offenders on cyberstalking outcomes. Overall, our study has provided further support for the ability of RAT concepts to account for aspects of cyberstalking victimization. Analyses of the mediator effects of online disclosure, however, were mixed. Specific findings are discussed below.

Target suitability in the current study was assessed with a personality measure of proclivity for risk-taking, the DOSPERT (Weber et al., 2002). Full model multivariate testing showed that only one domain of risk-taking measured by the DOSPERT, higher levels of Social risk-taking, was directly related to all three cyberstalking victimization outcomes (i.e., Hyper-Intimacy, Threat, and Real-Life Transfer). Only two other risk-taking domains measured on the DOSPERT were directly associated with COP subscales in the full multivariate model. Higher levels of ethical risk-taking was associated with higher levels of Real-Life Transfer on the COP. Additionally, higher levels of Health/Safety risk-taking was associated with higher levels of Threat on the COP. Both Ethical and Health/Safety risk-taking predicted levels of Online Disclosure. In contrast, social risk-taking was not statistically associated with Online Disclosure.

Across our multivariate models, Social risk-taking played a consistently important role in the risk for cyberstalking, suggesting that Social risk-taking may increase the target suitability of individuals for cyberstalking. The Internet is a social environment and the very function of SNSs is to facilitate social communication and the sharing of personal information (Greenwood, 2009). It is not unreasonable then to suggest that individuals who would take social risks in real-world settings might also be more likely to take social risks in an online environment. Social-risk taking in a cyber-environment, for instance, might take the form of posting sexually-themed photographs or sharing photographs of alcohol consumption from a party. High social risk-takers may also be more likely to accept “friend” requests and develop large social networks. Such activities may not only increase the likelihood that these individuals will be exposed to potential offenders, but may also serve to increase their attractiveness as potential victims based upon their availability to motivated offenders.

Two domains of risk taking on the DOSPERT (i.e., Recreational, Financial risk-taking) were not relevant to either levels of Online Disclosure or the COP scales. Items measuring aspects of Social, Ethical, and Health/Safety risk-taking may tap into user motivations for interacting on SNSs or interpersonal aspects of SNSs. Comparatively, the items measuring Financial and Recreational risk-taking may not correspond as closely to interpersonal dimensions that play a role in risk-taking on SNSs. Individuals likely to engage in recreational risk-taking behaviours (e.g., whitewater rafting, bungee jumping) may have different motivations for SNS use, or differing levels of frequency of SNS use, that differentially impact their risk for forms of online victimization, such as cyberstalking. Furthermore, our results indicated that the Financial risk-taking domain of the DOSPERT had little relevance to the undergraduate student sample in the study. Most of these subscale items concerned activities that were likely unfamiliar to young adults (e.g., Investing 10% of your annual income in a moderate growth mutual fund) thereby limiting its applicability.

Online Exposure, or proximity to motivated offenders, was measured with a scale that requested participants to indicate how frequently they use the Internet for a variety of activities. Findings from the full model multivariate analyses indicated that higher levels of online exposure were related to high levels of both Hyper-Intimacy and Real-Life Transfer on the COP scale. The relationship between Online Exposure and the Threat subscale of the COP was mediated by the role of Online Disclosure. These results confirm that those participants who not only use SNSs regularly, but also spend a great deal of time online for a variety of purposes, increase their risk for cyberstalking. According to RAT, this risk could in part stem from the “digital” proximity that frequent Internet usage creates for users. People who frequently use the Internet for social networking, banking, downloading and sharing media, or blogging are in effect increasing the extent to which they have online contact with other Internet users. With regard to cyberstalking, such increased exposure to motivated or potential offenders may fuel fantasies or obsession with victims (Hyper-Intimacy), increase the opportunities to communicate (Threat), and provide motivated offenders with information about personal schedules and whereabouts (Real-Life Transfer).

Our findings regarding the role of Online Disclosure as a guardianship effort were mixed. Findings from the full multivariate models showed that higher levels of Online Disclosure were associated with higher levels of Threat and Real-Life Transfer on the COP scale. Comparatively, self-reported levels of Online Disclosure did not predict levels of Hyper-Intimacy. Posting or sharing high levels of personal information on SNSs appears to increase the risk for certain cyberstalking behaviours. The absence of a relationship between Online Disclosure and the Hyper-Intimacy subscale of the COP may be accounted for by the impact of Online Exposure. In the full multivariate model, Online Exposure predicted levels of Online Disclosure and also directly predicted levels of Hyper-Intimacy. Past research has shown that some categories of traditional stalkers develop fixations with victims with whom they have had only minimal social contact (Cupach & Spitzberg, 1998; Meloy, 1996). On the COP scale, Hyper-Intimacy represents the lower severity levels of cyberstalking behaviours. The mere presence of information on a Facebook profile, such as a profile picture and e-mail address, could facilitate Hyper-Intimacy. In contrast, aspects of both Threat and Real-Life Transfer on the COP scale presume some increased level of online interaction and sharing of personal information. As such, higher levels of Online Disclosure might not be a necessary prerequisite for online behaviours that would constitute Hyper-Intimacy.

In addition, Online Disclosure does not appear to be a complete mediator of the relationship between variables measuring target suitability and proximity to motivated offenders and cyberstalking. The Ethical and Health/Safety risk-taking domains of the DOSPERT were related to the Threat and Real-Life Transfer subscales of the COP in the absence of Online Disclosure. However, the effects of these variables on cyberstalking victimization disappeared in the full model multivariate analyses that included Online Disclosure suggesting that disclosiveness mediated the effects of these aspects of risk-taking on the risk for cyberstalking. Levels of social risk-taking and Online Exposure influenced the risk for cyberstalking regardless of levels of Online Disclosure.

Overall, these findings build on the growing empirical support for the relevance of RAT to risk for victimization in cyber-environments. Our mixed findings regarding the role of Online Disclosure as a guardianship effort or a mediator of the relationship between target suitability, proximity to motivated offenders and the risk for online victimization may in part be accounted for by methodological limitations. First, findings pertaining to Online Disclosure may be an artefact of the use of a cross-sectional design. Mustaine and Tewksbury (1999) have argued that victims may enact guardianship measures in response to victimization experiences as opposed to levels of guardianship acting as a risk factor for victimization. In other words, people may increasingly enact guardianship efforts as cyberstalking experiences increase in frequency and severity. This may explain in part why Online Disclosure was not associated with self-reported levels of Hyper-Intimacy on the COP scale. Forms of Hyper-Intimacy, which are less serious forms of cyberstalking, may trigger subsequent online guardianship efforts. Future research examining the relationship between guardianship efforts and any form of online victimization should employ prospective longitudinal research designs.

Second, the operational definitions adopted for the theoretical components of RAT may account for the mixed findings concerning Online Disclosure. Resent research indicates that proximity, target suitability, and guardianship can be measured in numerous ways. The operationalization of guardianship adopted in the current study, Online Disclosure, focused on the willingness of participants to share personal information on SNSs. In recent years, several SNSs, including Facebook, have made a series of changes to privacy-control settings. Some evidence suggests that the implementations of privacy-settings by SNS users has increased, but variability still exists and there is a continuing lack of clarity about the factors that influence privacy monitoring on SNSs. Guardianship efforts on SNSs may not only include decisions around what information to share but also the level of privacy to assign to personal information. Moreover, while target suitability was measured with a general dispositional measure of risk-taking, research also illustrates that numerous individual differences, including SNS user motivation, may also be an aspect of target suitability relevant to both the use of privacy settings on SNSs and cyberstalking victimization risk. Future research should adopt multiple measures of the theoretical components of RAT in accordance with the growing empirical literature, particularly user motivation and user incorporation of privacy control settings.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings suggest that increasing amounts of time spent engaging with online social networking and high levels of online disclosure of personal information contribute to risks for cyberstalking. Contrary to criticisms of RAT and its purported limited applicability to cybercrime, this study also provides additional support for the relevance of the concepts of RAT and it ability to explain links between online activities and cybercrime. Lastly, given past research that has observed that some SNS users are either unaware of or simply fail to implement privacy measures, our findings support concerns about online safety for some Internet users. Regardless of the directions or modes that social networking may eventually adopt, the trend of increasing social connectivity in online environments is unlikely to abate. As such, future research must continue to explore the links between risky online behaviour and cybercrime.

Notes

1. A total of four pair-wise t-tests were conducted to examine differences between the Social domain and the four other DOSPERT domains (i.e., Social-Recreational, Social-Financial, Social–Ethical, and Social-Health/Safety). Notably, because a total of ten pair-wise t-tests were conducted a Bonferroni correction of α =.05/10 = .005 was applied to all tests to control for inflated family wise error.

2. A total of four pair-wise t-tests were conducted to examine these differences (i.e., Recreational-Ethical, Recreational-Financial, Health/Safety-Ethical, Health/Safety-Financial)

References

Alexy, E. M., Burgess, A. W., Baker, T., & Smoyak, S. A. (2005). Perceptions of cyberstalking among college students. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 5, 279-289.

Alshalan, A. (2006). Cyber-crime fear and victimization: An analysis of a national survey (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database (3238924).

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182.

Barrett, J. (2006, May/June). Social networking: A new tech tool and a new security concern for teens and schools. MultiMedia & Internet@Schools, 13, 8-11.

Bateman, P. J., Pike, J. C., & Butler, B. S. (2011). To disclose or not: Publicness in social networking sites. Information Technology & People, 24, 78-100.

Beech, A. R., Elliot, I. A., Birgden, A., & Findlater, D. (2008). The Internet and child sex offending: A criminological review. Aggression and Violent Offending, 13, 216-228.

Blais, A. R., & Weber, E. U. (2006). A domain-specific risk-taking (DOSPERT) scale for adult populations. Judgement and Decision Making, 1, 33-47.

Blaauw, E., Winkel, F. W., Arensman, E., Sheridan, L., & Freeve, A. (2002). The toll of stalking. The relationship between features of stalking and psychopathology of victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17, 50−63.

Bocij, P. (2003) Victims of cyberstalking: An exploratory study of harassment perpetrated via the internet. First Monday, 8, 10. Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1086/1006

Bocij, P., & McFarlane, L. (2002). Online harassment: Towards a definition of cyberstalking. Prison Service Journal, 139, 31-38.

Bocij, P., & McFarlane, L. (2003). Cyberstalking: The technology of hate. Police Journal, 76, 204-221.

Bossler, A. M., & Holt, T. J. (2009). Online activities, guardianship, and malware infection: An examination of routine activities theory. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 3, 400-420.

Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 13, 210-230.

Boyd, D. M., & Hargittai, E. (2010). Facebook privacy settings: Who cares? First Monday, 15, 13-20.

Briggs, P., Simon, W. T., & Simonsen, S. (2011). An exploratory study of Internet-initiated sexual offenses and the chat room sex offender: Has the Internet enabled a new typology of sex offender. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 23, 72-91.

Bugeja, M. J. (2006, January 27). Facing the Facebook. Chronicle of Higher Education, pp. C1, C4.

Burgess, A. W., & Baker, T. (2002). Cyberstalking. In J. C. W. Boon & L. Sheridan (Eds.), Stalking and psychosexual obsession: Psychological perspectives for prevention, policing and treatment (pp. 201-219). Chichester: Wiley.

Campbell, M. A. (2005). Cyberbullying: An old problem in a new guise? Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 15, 68-76.

Cohen, L., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44, 588-608.

Debatin, B., Lovejoy, J. P., Horn, A. K., & Hughes, B. N. (2009). Facebook and online privacy: Attitudes, behaviours, and unintended consequences. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 15, 83-108.

Donoso, V. (2011). Assessment of the implementation of the Safer Social Networking Principles for the EU on 9 services: Summary Report. Retrieved from European Commission, Information Society, Safer Internet Programme website: http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/activities/social_networking/docs/final_reports_sept_11/report_phase_b_1.pdf

Finkelhor, D., Mitchell, K. J., & Wolak, J. (2000). Online victimization: A report on the nation’s youth. National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

Finn, J. (2004). A survey of online harassment at a university campus. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19, 468-483.

Finn, J., & Banach, M. (2000). Victimization online: The downside of seeking human services for women on the Internet. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 3, 785-797.

Fisher, B. S., Cullen, F. T., & Turner, M. G. (2002). Being pursued: Stalking victimization in a national study of college women. Criminology and Public Policy, 1, 257-308.

Govani, T., & Pashley, H. (2005). Student awareness of the privacy implications when using Facebook. Retrieved from http://lorrie.cranor.org/courses/fa05/tubzhlp.pdf

Grabosky, P. N., & Smith, R. (2001). Telecommunication fraud in the digital age: The convergence of technologies. In D. S. Wall (Ed.), Crime and the Internet (pp. 29-43). London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Greenwood, B. (2009). Pew reports: Internet age barrier vanishing. Information Today. Retrieved April 4, 2011, from http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/infotoday/...

Gross, R., & Acquisti, A. (2005). Information revelation and privacy in online social networks. Retrieved from http://www.heinz.cmu.edu/~acquisti/papers/privacy-facebook-gross-acquisti.pdf

Hass, N. (2006, January 8). In your Facebook.com. New York Times, pp. 30-31.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2008a). Personal information of adolescents on the Internet: A quantitative content analysis of MySpace. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 125-146.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2008b). Cyberbullying: An exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behavior, 29, 29-156.

Holt, T. J., & Bossler, A. M. (2009). Examining the applicability of lifestyle-routine activities theory for cybercrime victimization. Deviant Behavior, 30, 1-25.

Jameson, S. (2008). Cyberharassment: Striking a balance between free speech and privacy. CommLaw Conspectus, 17, 231-266.

Jones, S., & Fox, S. (2009). Generations online in 2009. Retrieved from Pew Internet & American Life Project website: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/Generations-Online-in-2009/Generational-Differences-in-Online-Activities.aspx

Junco, R., & Mastrodicasa, J. (2007). Connecting to the Net.Generation: What higher education professionals need to know about today’s students. Washington, D.C.: National Association of Student Personnel Administrators.

Kolek, E. & Saunders, D. (2008). Online disclosure: An empirical examination of undergraduate Facebook profiles. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 45, 1-25.

Kornblum, J., & Marklein, M. B. (2006, March, 9). What you say online could haunt you. USA Today, p. 1A.

Lenhart, A., & Madden, M. (2007). Social networking and teens: An overview. Retrieved from Pew Internet & American Life Project website: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2007/Social-Networking-Websites-and-Teens.aspx

Lucks, B. D. (2004). Cyberstalking: Identifying and examining electronic crime in cyberspace. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 65(2-B), 1073.

Marchum, C. D., Ricketts, M. L., & Higgins, G. E. (2010). Assessing sex experiences of online victimization: an examination of adolescent online behaviors using routine activity theory. Criminal Justice Review, 35, 412-437.

McGrath, M. G., & Casey, E. (2002). Forensic psychiatry and the internet: Practical perspectives on sexual predators and obsessional harassers in cyberspace. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 30, 81-94.

Meloy, J. R. (1996). Stalking (obsessional following): A review of some preliminary studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 1, 147-162.

Meloy, J. R. (1998). The psychology of stalking: Clinical and forensic perspectives. New York: Academic Press.

Meloy, J. R. (2003). When stalkers become violent: The threat to public figures and private lives. Psychiatric Annals, 33, 659−665.

Miller, C. (2006). Cyberharassment: Its forms and perpetrators. Law Enforcement Technology, 33, 26-30.

Mitchell, K., Finkelhor, D., & Wolak, J. (2007). Youth internet users at risk for the more serious online sexual solicitations. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 32, 532-537.

Mustaine, E. R, & Tewksbury, R. (1999). A routine activity theory explanation for women’s stalking victimizations. Violence Against Women, 5, 43-62.

Newman, G., & Clarke, R. (2003). Superhighway robbery: Preventing e-commerce crime. Cullompton, UK: Willan Press.

Ogilvie, E. (2000). Cyberstalking. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 166, 1-6.

Pease, K. (2001). Crime futures and foresight: Challenging criminal behaviour in the information age. In D. Wall (Ed.), Crime and the internet (pp. 18-28). New York: Routledge.

Pittaro, M. L. (2007). Cyber stalking: An analysis of online harassment and intimidation. International Journal of Online Harassment and Intimidation, 1, 180-197.

Raynes-Goldie, K. (2010). Aliases, creeping, and wall cleaning: Understanding privacy in the age of Facebook. First Monday, 15, 1. Retrieved from http://ojphi.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2775/2432

Rosenfeld, B. (2004). Violence risk factors in stalking and obsessional harassment. A review and preliminary meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 31, 9−36.

Safer Social Networking Principles of the EU. (2009). Retrieved from European Commission, Information Society website http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/activities/social_networking/docs/sn_principles.pdf

Sheridan, L. P., & Grant, T. (2007). Is cyberstalking different? Psychology, Crime, & Law, 13, 627-640.

Spitzberg, B. H., & Cupach, W. R. (2007). The state of the art of stalking: Taking stock of the emerging literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 12, 64-86.

Spitzberg, B. H., & Hoobler, G. (2002). Cyberstalking and the technologies of interpersonal terrorism. New Media & Society, 4, 71-92.

Spitzberg, B. H., & Rhea, J. (1999). Obsessive relational intrusion and sexual coercion victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14, 3-20.

Spitzberg, B. H., Marshall, L., & Cupach, W. R. (2001). Obsessive relational intrusion, coping, and sexual coercion victimization. Communication Reports, 14, 19-30.

Tewksbury, R., & Mustaine, E. E. (2003). College students’ lifestyles and self-protective behaviors: Futher considerations of the guardianship concept in routine activity theory. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 30, 302-327.

Weber, E. U., Blais, A. R., & Betz, N. E. (2002). A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: Measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 15, 263-290.

Yar, M. (2005). The novelty of ‘cybercrime’: An assessment in light of routine activity theory. European Journal of Criminology, 2, 407-427.

Ybarra, M. L. (2004). Linkages between depressive symptomology and Internet harassment among young regular internet users. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7, 247-257.

Ybarra, M. L., Mitchell, K. J, Finkelhor, D., & Wolak, J. (2007). Internet prevention messages: Targeting the right online behaviors. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 161, 138-145.

Young, A. L., & Quan-Haase, A. (2009). Information revelation and Internet privacy concerns on social network sites: A case study of Facebook. Paper presented at Fourth International Conference on Communities and Technologies, Penn State University.

Yucedal, B. (2010). Victimization in cyberspace: An application of Routine Activity and Lifestyle Exposure theories (Doctoral dissertation, Kent State University). Retrieved from http://etd.ohiolink.edu/send-pdf.cgi/YUCEDAL%20BEHZAT.pdf?kent1279290984

Zona, M. A., Sharma, K. K., & Lane, J. C. (1993). A comparative study of erotomanic and obsessional subjects in a forensic sample. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 38, 894-903.

Correspondence to:

Andrew Welsh

Department of Criminology

Wilfrid Laurier University – Laurier Brantford

73 George St.

Brantford, Ontario, N3T 2Y3

(519) 756-8228

Email: awelsh(at)wlu.ca