Cyberbullying in Adolescent Victims: Perception and Coping

Veronika Šléglová1, Alena Cerna2

Abstract

The present qualitative explorative study deals with cyberbullying from the perspective of adolescents. It focuses mainly on the impacts and consequences of cyberbullying, and on the coping strategies chosen by victims to deal with the situation. The data was obtained through semi-structured interviews with 15 adolescents aged 14-18 years, all of whom were cyberbullying victims.

It was found that cyberbullying experiences led to changes in the victims' behaviour, and that these could be positive in the form of behavioural changes in cyberspace. Mainly this was due to victims creating a cognitive pattern of bullies, which consequently helped them to recognise aggressive people. Bullying also provoked feelings of caution, and brought about restriction in the use of risky online sources of threats as victims tried to prevent its recurrence. Critical impacts occurred in almost all of the respondents’ cases in the form of lower self-esteem, loneliness and disillusionment and distrust of people: The more extreme impacts were self-harm and increased aggression towards friends and family.

Based on their experience, the victims of cyberbullying developed coping strategies in order to cope with cyberbullying. These strategies took several forms: technical defence, activity directed at the aggressor, avoidance, defensive strategies, and social support. The activities of the victims when dealing with this stressful situation varied, which was probably influenced by different contexts, personal traits, and the development of the respondents. The findings further revealed that some coping strategies (i.e. technical coping or telling parents) are in many situations either non-functional or just cannot be used, a theme which is further discussed with respect to previous research in the field.

Keywords:cyberbullying, adolescence, coping, bully, victim

Introduction

Cyberbullying has been repeatedly analysed in the last few years, but its definition has often varied in different studies. This sometimes had striking impacts on results, and as it is difficult to reach consensus, the "definition" is still debated by researchers across the world. However, with respect to the most current research in the field and for the purpose of this study, we define cyberbullying as "an aggressive, intentional act or behaviour that is carried out by a group or an individual repeatedly and over time against a victim who cannot easily defend him or herself" (Smith & Slonje, 2007, p. 249). This terminology was further expounded on by Price and Dalgleish (2010, p. 51): "Cyberbullying is the collective label used to define forms of bullying that use electronic means such as the internet and mobile phones to aggressively and intentionally harm someone. Like "traditional" bullying, cyberbullying typically involves repeated behaviour and a power imbalance between aggressor and victim." Across these definitions, the attributes of intentionality, repetition, and imbalance of power are stressed, and they arguably represent the most important identifiers of cyberbullying. If those identifiers are present, we can speak about direct cyberbullying; but, given the opportunities of online space, the aggressor has even more opportunities to reach the victim when compared to traditional offline settings. That is why Aftab (no date) distinguishes between direct cyberbullying (which is more common and what the present study is primarily focused on), and indirect cyberbullying (or cyberbullying by proxy). Indirect cyberbullying is represented by the situation when someone else does the "dirty work“ for the aggressor, i.e. the administrator, who blocks the victim´s profile after the agressor´s report, etc. The term refers mainly to the fact that people who are being used to represent the aggressor in the role of the cyberbully often do not know about being used in this way. That is considered dangerous as adults are often unconsciously involved in it.

Victims’ reactions and the impacts of cyberbullying

Victims of cyberbullying, faced with such a distress situation, which is often difficult to escape, show a variety of reactions. Beran and Li (2005) investigated reactions to cyber harassment, focusing on the incidence of different emotions and the subsequent behaviour of the victims in connection with cyber harassment. The emotions were those of anger, sadness, anxiety, embarrassment, crying, fear, and self-blame. Other impacts were also discovered: worsened concentration and school grades, and absence from school. The authors were inclined to connect this with the theory of social dominance, wherein the victims feel they are in a subordinate position with respect to the aggressor, which consequently causes negative emotions and affects the victims’ behaviour in the school environment. The authors added that many respondents mentioned that they were not affected by cyber harassment. The authors thought this was due to the fact that harassment is considered "normal“ or is "expected.“

In connection to cyberbullying – for example in Campfield’s (2006) research - most victims also showed signs of stress, triggered by bullying. From a clinical point of view, the victims showed internalised symptoms, loneliness and low self-esteem connected to externalisation, and overall problems (both emotional and behavioural). These were triggered by aggressive acts such as (e.g. Campfield, 2006): having cell phone pictures of the victims taken without their permission; putting down or embarrassing the victims on the Internet; hurtful emails from peers, offensive, sexual emails from peers, emails threatening victims with physical harm; lies or rumours started about the victims over the Internet.

Another form of cyberbullying is the combination of traditional bullying and cyberbullying. The individuals experiencing this combination become global victims. In the case of those who are victimised in multiple ways and environments, there is a higher probability of an outbreak of extreme stress (Shariff & Churchill, 2010). Campfield (2006) characterises these victims' cases as a "double whammy" and her research confirms the presence of a whole range of problems caused by double bullying: social problems, behaviour problems, perception of negative evaluation by peers, low self-esteem, and loneliness.

Based on the various manifestations of cyberbullying, Dehue, Bolman and Völlink (2008) researched the emotional reactions of adolescents to cyberbullying. Most often the experience of bullying provoked feelings of anger in the victims (10.3%), sadness (4.9%), not liking going to school (3.6%), and disillusionment and distrust of peers (2.9%).

The only study exploring connections between psychosocial, psychiatric, psychosomatic elements and the experiences of cyber-victims and cyberbullies is a Finnish study, the findings of which show a number of basic facts (Sourander et al., 2010): Girls in the role of the aggressor may be physically weaker than their victims; on average 34% of the respondents who experienced cyberbullying consequently feared for their own safety. Further, fearing for one’s safety is likely stronger in the case of cyberbullying than in traditional bullying because traditional bullying takes place mainly in the school environment and the victim at least feels safe at home. When cyberbullied, the victims are accessible around the clock, and there is no time when text messages, emails, or other messages cannot be sent; the reactions of adolescents when in contact with strangers are also indirectly pointed out – the findings show that cyberbullying by an adult of the same/opposite gender, a stranger or a group of people triggers feelings of fear in the victims, which can subsequently indicate possible trauma. This is connected to a much higher imbalance of power in comparison to cyberbullying by the victim’s peers.

Much like traditional bullying, cyberbullying is connected to a wide range of psychiatric and psychosomatic problems. Adolescent victims who came from a non-two-biological-parent family, experienced (Sourander et. al, 2010) more frequent psychosomatic problems, headaches, sleep disorders, repeated stomach-aches; a higher number of perceived problems; emotional and peer-related problems; and feeling insecure at school and neglected by teachers. These manifestations also occurred in the cases of adolescent-aggressors, along with signs of hyperactivity, frequent smoking, drunkenness, and low levels of positive prosocial behaviour (Sourander et al., 2010).

Hinduja’s and Patchins’s (2010) research focused on students’, both aggressors’ and victims’, experiences with traditional and cyberbullying within the 30 days prior to the research. The authors looked into the correlations between these experiences and thoughts of suicide. Youths who experienced traditional bullying or cyberbullying, as either an offender or a victim, had more suicidal thoughts and were more likely to attempt suicide than those who had not experienced such forms of peer aggression. Also, victimization was more strongly related to suicidal thoughts and behaviors than offending.

The impacts of cyberbullying can be measured by an impact factor – Smith et al. (2008) calculated "an impact factor to display the severity of each subcategory of cyberbullying in comparison to traditional bullying (−1 = less effect, 0 = same effect and +1 = more effect, divided by total number of respondents excluding "don’t know’s“). If an impact factor is positive, that category is perceived as having more of an effect compared to traditional bullying; if negative, then less of an effect". This is based on perceiving the issues on the basis of the intensity of their impacts on a particular victim. Picture/video clips had the highest impact factor which shows that many students believe this the worst of all forms of cyberbullying. Phone calls also scored highly on the impact factor. Text messages and websites have, according to the students, a neutral score; the respondents evaluated this in the same way as the issue of traditional bullying. Email, chat rooms and IM had impact factors slightly lower and the students perceived these forms as less effective and mainly less hurtful to the victims (Smith et al., 2008).

Price and Dalgleish’s research (2010) on cyberbullying victims, which also followed up on the impact of cyberbullying, quotes self-esteem (78%), self-evaluation (70%) and friendship as the most common impacts in victims. 35% of the respondents stated negative impacts on school grades, 28% on school attendance, and 19% on family relationships. Many of the respondents stated a wide impact on emotional behaviour. 75% of the respondents felt sad, 54% mentioned feelings of extreme sadness. Moreover, 58% felt frustrated, 48% embarrassed, and 48% felt fear, including 29% who felt terrified. 3% were thinking of suicide and 2% self-harmed due to cyberbullying (Price & Dalgleish, 2010).

Coping strategies in cyberbullying

According to available research and the experiences described above, cyberbullying can produce a number of negative, stressful, even traumatic feelings which often bring about intense impacts on the well-being and other behaviour of the victims (e.g. Beran & Li, 2005; Campfield, 2006; Dehue, Bolman & Völlink, 2008, etc.). In extreme cases, cyberbullying may have fatal results. Coping strategies in cyberbullying are, when compared to the number of studies on general coping strategies, a new issue. Research into coping with cyberbullying has only begun in the last few years.

The efficiency of a coping strategy lies in its capacity to reduce immediate stress as well as to prevent its long-term consequences, such as, influences on psychical well-being, or the development of an illness. The effectiveness of a given coping strategy may appear different to the individual employing it than to those observing and evaluating it (Snyder, 1999).

Traditionally, coping strategies have been divided into dichotomous categories - probably the most well-known coping models are the transactional model (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and the approach-avoidance model (Roth & Cohen, 1986). In the transactional model, coping is defined as problem-focused and emotion-focused; the approach-avoidance model describes particular strategies which can be categorised either as approach or avoidance. The individual’s consideration as to whether they have the resources for a solution to the given situation is the most important aspect in both of these models. In the approach-avoidance model, the individual considers whether they have the resources for coping with the situation and subsequently chooses either the approach mode (focused on a direct solution to the problem), or the avoidance mode (Roth & Cohen, 1986). In cyberbullying, this mode takes the form of leaving a website, deleting threatening messages etc. In the context of cyberbullying, some studies include technical coping or directly addressing the bully in this model (Parris, Varjas, Meyers & Cutts, 2011). In the transactional model (Lazarus & Folkman, 1986), there is a process of primary and secondary appraisal: In the primary mode, there is an appraisal of whether an event is a threat; in the secondary appraisal, individuals choose a particular coping strategy which is appropriate to the resources at their disposal. Research into this indicates that classifying strategies into known general categories can be problematic, and may depend on the construction of the measuring tool (Riebel, Jäger & Fisher, 2009). Some coping strategies may fall into two categories at the same time, even into those considered opposite e.g. problem-focused and emotion-focused (Parris et al., 2011). Skinner, Edge, Altman and Sherwood (2003) thus call for a change in the use of the categories of emotion-focused vs. problem-focused, approach vs. avoidance, and cognitive vs. behavioural, and instead suggest a hierarchical arrangement of coping strategies.

Studies that deal directly with coping strategies build their schematic distribution differently. Parris et al. (2011) carried out qualitative ethnographic research into the coping strategies applied directly to cyberbullying among high-school students. They devised categories which characterise the coping strategies used in the context of reactions to cyberbullying. They divided the coping strategies of the respondents in terms of reactive and preventive coping. Reactive coping included avoiding, accepting, justification, and seeking social support. Preventive coping (strategies aimed at preventing or reducing the probability of the incidence of cyberbullying) included talking in person (face-to-face contact in order to prevent misunderstanding), increased security and awareness, and also a category "no way to prevent cyberbullying“ occured as a representation of helplessnes regarding prevention.

Another view is using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods: Price and Dalgleish (2010) researched the coping strategies used by Australian participants to manage cyberbullying. Their findings were similar to those of Parris et al. (2011), including confiding in friends and teachers, staying offline, not using websites/software used by the bully, doing nothing specific, blocking the bully etc. Dehue et al. (2008) describes activities used by the respondents in reaction to cyberbullying: pretending to ignore it (7.2%), actually ignoring it (6.9%), bullying the bully (5.7%), or deleting the bully’s messages (3.1%).

Other studies focusing on coping strategies to deal with cyberbullying define similar or identical reactions to cyberbullying (e.g. Staksrud & Livingstone, 2009; Smith & Slonje, 2007), but no further context of those reactions was examined.

Apart from particular coping strategies, and the perceived impacts of cyberbullying on the individual respondents, there are questions concerning the efficiency of particular coping strategies: The efficiency of these strategies for the victims themselves remains uncharted territory (Parris et al., 2011, Riebel, Jäger & Fisher, 2009), and the same can be said about traditional bullying (Tenenbaum et al., 2011).

As stated in the overview of existing studies, there are many possible coping strategies, but our study focuses specifically on the victim’s view of the impacts of cyberbullying and on the subsequent solutions of the problem. In the present study, we focus on adolescent victims of direct cyberbullying, using in-depth approach. As adolescents represent the majority of cyberbullying victims (Ševčíková & Šmahel, 2009), primarily due to their much more frequent online activities (Lupač & Sládek, 2008; Šmahel & Lupač, 2008; Wolak, Mitchell & Finkelhor, 2006), we focused on this age group.

Our goal is to bring greater understanding of both the victim’s experience of cyberbullying, which has been mainly quantitatively analysed so far, and to provide insights into coping strategies and – quite innovatively – the background of selecting (or non-selecting) particular ways to cope and the victim´s perception of the effectiveness of selected coping strategies. The analysis of coping strategies in cyberbullying is considered essential in this study, especially with regard to how difficult it is to better understand these strategies by putting them into dichotomous categories. Based on previous research, it seems it becomes very difficult to label multiform reactions as "emotion-focused“ or "problem-focused.“ Further, it seems that the line between "approach“ and "avoidance“ in the "approach-avoidance“ model is too thin (e.g. Parris, Varjas, Meyers & Cutts, 2011).

Another important aim of this study is to monitor the impacts cyberbullying may have on the victims, and the consequences it may lead to. Our assumption is that the victim´s experience with cyberbullying is multi-faceted, and to grasp that reality we should take a deeper look into particular stories, which is still missing in up-to-date research. Thus, through an in-depth approach, our aim is to address the gap that might be given by the character of previous research and the fact that research on cyberbullying has been only carried out past few years, so still can only be understood as a young discipline. In order to address that gap, we propose research questions as follows:

How does the experience of cyberbullying manifest itself in adolescent victims?

In what ways do adolescent victims cope with cyberbullying?

Methods

Participants and context

In the first round of selecting respondents, users of the Czech social sites (or community servers) Libimseti.cz, Lide.cz and Xchat between the ages of 11-18 were contacted. These sites were chosen due to the large number of users aged between 11-18 on which the research focuses. Also, these sites are very well known Czech community servers among contemporary Czech youth. The contact was carried out in the form of an invitation, which included all information on the research, and a description of the situation that can be classified as cyberbullying. In the invitation, we explained the situation as follows: "For the purpose of research, we are looking for young people aged 11-18 years who have experienced any of the following situations: Someone has been repeatedly harassed over the Internet for a long period of time – has received inappropriate messages on ICQ and Facebook from their classmates, friends, or strangers; someone is deliberately denigrating and mocking them on some website or a blog or is regulating their photos and videos or is impersonating them on the Internet. " The selection of respondents was conditioned by age (11-18) and the online activity of the users (only active users were contacted – on Libimseti.cz, this meant having logged on in the last week, for Lide.cz and Xchat this meant having had regular chat sessions). Overall, 18,950 users from all regions of the Czech Republic were contacted.

In the next step, those respondents who had replied to the invitation were asked to participate in an ICQ or Skype chat interview. Overall, 35 respondents (30 girls and 5 boys) responded via e-mail (riziko.na.internetu@email.cz) or a social site message. The disproportion between girls and boys was caused mainly by their use of the selected websites – girls’ having many more accounts than boys. The comparatively low feedback probably lies in the incidence of cyberbullying among adolescents, which, according to Ybarra et al. (2007), ranges from 2 to 3%. According to Ševčíková and Šmahel (2009), the incidence is around 3.6% in young adolescents and around 3.2% in middle and older adolescents in the Czech Republic. It is also possible that, even though the approached users had experienced cyberbullying, they did not want to be interviewed (as some stated in their replies to the invitation).

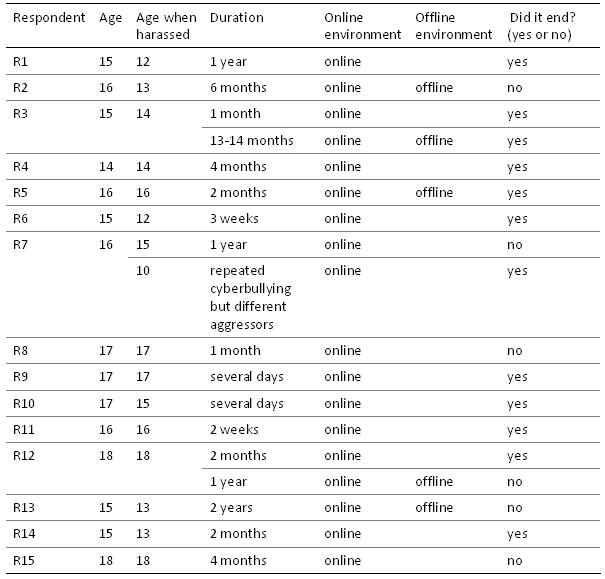

The research sample included 15 respondents (13 girls and 2 boys), between the ages of 14-18 years. Out of the original 35 respondents, their experiences with online bullying were assessed as cyberbullying. Other respondents who replied to the invitation and have had experience with cyberbullying did not respond to the subsequent request for an online interview or in further contact with them we found that their experience was not cyberbullying. The duration of the cyberbullying differed from case to case: in some cases, it occurred for a few days, in others for much longer, even up to two years. It needs to be mentioned that in eight cases bullying took place in the past, or started in the past and is still taking place. Thus, the respondents were younger when they experienced cyberbullying than they were at the time of the interview. In six cases, bullying is still taking place (respondent no. 7 experienced cyberbullying a year ago and is now experiencing cyberbullying again from another aggressor – see Table 1). The respondents described their situations without expressing any knowledge of the concept of cyberbullying itself. This information was not provided to them because an awareness of what in fact had happened to them could have distorted their description of the situation, and led them to think of different concepts.

The data was gathered over three months on the three aforementioned websites, where all users meeting the selection criteria (aged 11 – 18 and active on the websites) were contacted. Responses to the interview invitation, whether positive or negative, were replied to within several hours of receipt. It is probable that the respondents who replied to the invitation trusted the researcher, which was consequently reflected in the amount and quality of information provided to the researcher. Potentially, this trust was built through the detailed information on the research project and the interviewer’s identity made publicly available on the given websites as well as on the research’s Facebook page.

Table 1. Basic information about respondents.

Instrumentation and Data Analysis

For data gathering, semi-structured interviews were used. These were carried out using ICQ and Skype chat; these are types of online Instant Messengers, allowing to asses online interviews in real time. The interviews focused generally on cyberbullying, however, the focus of the present study is narrowed down to the impacts of, and coping strategies in cyberbullying: Both of these emerged as essential and strong categories in the course of the interviews. This form of online interview was preferred to face-to-face interviews due to the geographical spread of the respondents - there were respondents from all regions of the Czech Republic - making it more accessible in terms of time and finances; and also due to the nature of the research, it dealing with a primarily virtual-reality phenomenon. The respondents themselves tried to actively ascertain if their anonymity was guaranteed, and stated that they preferred online contact. Further, as respondents feel safer, being anonymous and "invisible“ online, they are willing to disclose more personal information (Coomber, 1997; Joinson, 2001). When researching sensitive issues like cyberbullying, online interviews can in fact allow researchers to acquire more information than in face-to-face interviews, despite the other advantages of the face-to-face environment over virtual reality.

The qualitative method of grounded theory was used in the research – it explores phenomena inductively, based on the systematic gathering of theoretical and analytical data. Then, corresponding to the field studied, a theory is created explaining the issue. The analysis, or coding, is carried out in three stages: open, axial, and selective coding.

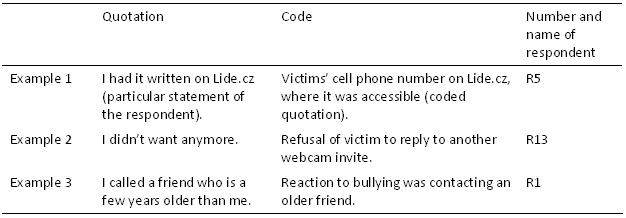

The stage of open coding was carried out using ATLAS.ti 6.0. It was carried out through creating codes representing the respondents’ statements. Here are some examples of coding:

Table 2. Examples of coding.

Next in axial coding, the individual codes were divided into 36 categories, which were then merged and dimensionalised. In the last stage of selective coding, relations and connections between categories and subcategories were found.

Individual categories, subcategories and their connections are depicted in the Figure 1:

Figure 1. Paradigmatic model of coping strategies and the impacts of cyberbullying.

Results

The category of impacts and consequences of cyberbullying was divided into two parts: changes in online behaviour, and offline psychological impacts. Another category which emerged during the coding was that of coping strategies, where respondents stated the ways they dealt with cyberbullying.

Impacts and Consequences of Cyberbullying: Changes in online behaviour

Changes in online behaviour were one of the consequences of cyberbullying: they involved more careful and more cautious approaches of the victims to further communication, use of the Internet and their movements in virtual reality. These changes manifested themselves in:

(1) The creation of a cognitive pattern for identification of aggressors - respondent no. 14 a 15-year old female, stated that she learned to assess people on the basis of their language use:

"5 words are enough for me to know whether to end the conversation or not.“

Similarly, respondent no. 8, a 17-year-old male, believed he could recognise aggressors based on their style of communication:

"For example I’m detached from it, but there are a lot of people who don’t have the will power and they get pushed into things and they have no idea who’s sitting on the other side and that something could be made public on the Internet."

(2) The restriction of risky online sources of threats or the adoption of a more cautious approach – in the case of restricting risky online sources of threats, respondent no. 11 (female, age 16) mentioned restricting personal information which had previously been public on the Internet:

"I deleted all my pics from the net."

Respondent no. 4 (female, age 14) reacted in a similar way:

"Now I know I shouldn’t give my phone number to just anyone."

Three respondents either completely abandoned the possibility of getting in touch with people online, or they severely restricted it. They are now much more cautious in virtual reality, and they choose to communicate primarily with users they know offline. Respondent no. 11 (female, age 16) also added that she realised how real the experience of cyberbullying was:

"It showed me that it can actually happen, and it’s not just something people tell you about. Now I know it’s real."

Respondent no. 7 (female, age 16) thought about her future and her approach towards cyberbullying in regards to her future children. She is ready to adopt a much more cautious approach towards her activities in the online environment: "I am definitely supportive of parents checking their children’s net and messages. Too bad my parents did not do that. I am definitely going to do that."

In some cases, there were no significant changes in the respondents’ online behaviour despite their experience with cyberbullying. The 18 year old female respondent no. 12 explains it in her view of the Internet:

"I know the Internet is never going to be so protected as to completely get rid of this…that’s one of the negative sides of democracy."

Impacts and Consequences of Cyberbullying: Offline psychological impact

The psychological impact on the respondents varied greatly. The impacts seems to depend on the intensity of the cyberbullying, its duration, and, as mentioned above, on the psychosocial context of the respondents, their degree of resilience to the stress of cyberbullying, and other aspects which could not be further studied and analysed here. The respondents described the following impacts of cyberbullying: Two respondents claimed that the experience of cyberbullying had no impact – no. 8 (male, age 17) perceived the intensity of cyberbullying as lower than the other respondents. The other respondent no. 10 (male, age 17) is still experiencing cyberbullying and thinks (perhaps due to the continuation of the problem) he will keep visiting the website.

"I will not allow them to treat me that way."

Negative emotions caused by bullying, which had ceased, occurred in the case of the 16-year-old female no. 11. The impact of bullying has had lasting consequences, influencing her state of mind:

"It’s still in my psyche…but I know I’m never going to repeat that and it’s going to stay with me forever."

The 15-year-old female respondent no. 14 describes her feelings when thinking of the aggressor in a similarly negative manner, and the impact of bullying in her case is also lasting:

"He is still in my head and it makes me sick."

A feeling of helplessness was one of the recurring emotions. It was characterised mainly by having no opportunity or possibility to act or deal with the problem:

"It’s horrible because I know I can’t do anything, just ignore him and delete." (female no. 1, age 15).

The 15-year-old female no. 14 even likened cyberbullying to hunting and it is thus possible that she felt helpless like prey:

"I think he didn’t want to accept my refusal… that it was like hunting for him…and he couldn’t be a bad hunter, couldn’t lose his prey."

Disillusionment and distrust of other people, caused by cyberbullying, occurred in the cases of six respondents – for example in the case of the 16-year-old female no. 7 where its manifestation is intensifying:

"I see bad things in everyone."

The 15-year-old female respondent no. 13 specifies her feelings of disillusionment and distrust in this way:

"I don’t trust guys, I’m careful.“

Disillusionment and distrust also occurred in the cases of three female respondents. Female no. 1 associates the occurrence of disillusionment and distrust with her own self-change:

"I’m no longer so naive and I don’t trust everyone.“

Lower self-confidence occurred in the case of the 18-year-old female no. 15 in reaction to negative comments from Facebook-group members who targeted her weight. She mentioned lower confidence and also speculated about the truth of the comments:

"I’m maybe no longer so confident…or I think about whether they were right that I’m bigger etc."

Nightmares occurred in the case of the 16-year-old female respondent no. 7 during her first experience with cyberbullying, when she was ten:

"I couldn’t sleep a few nights and had weird dreams, I know that…they were about someone forcing me to do something I didn’t want to do etc. Or someone was chasing me. I experienced a period during which I just couldn’t go to sleep alone."

Social isolation manifested itself in the case of the 15-year-old female no. 3, who experienced both offline and cyberbullying:

"I don’t want to meet new people…and I’ve been a nervous wreck ever since…and I don’t go out much.“

Reluctance towards meeting new people, which was successfully overcome, occurred after cyberbullying in the case of the 16-year-old female no. 5:

"I didn’t want to date anymore, I saw the bad side in everyone and was afraid I would end up like that again.“

The 15-year-old female respondent no. 3 also mentioned an increasing feeling of loneliness, which may have been caused by less contact with her girlfriends who she used to go out with prior to experiencing cyberbullying:

"I kind of wander about on my own."

Impacts of cyberbullying in terms of changes in physical manifestations occurred in the cases of three female respondents. In two cases, self-harm manifested in the form of cutting. One of them started cutting herself after being cyberbullied:

"Ever since I’ve been cutting myself whenever I feel really anxious."

The 16-year-old female respondent no. 11 cut herself during stressful situations and cyberbullying caused regression in her behaviour:

"I used to cut myself before and as I was feeling down I started doing it again."

The 15-year-old female no. 3 gained weight (10 kilos) when dealing with traditional and cyberbullying. She also showed signs of physical aggression targeted at other people. This is a case of, as she calls it herself, a change in her personality:

"I deal with conflicts physically when the other person’s argument is equally strong…when someone is being fresh I slap them and leave…I have been a nervous wreck ever since."

The 15-year-old female respondent no. 14 experienced a similar type of aggression. While thinking about her aggressor she hurt her male friend during a sharp-weapon practice:

"I remembered this guy [aggressor’s name] and I got mad, and I cut fast and cut through his hand…luckily I managed to slow down and didn’t cut it off completely…but he ended up with a katana to the bone."

Coping strategies: Technical Coping

The activities of the victims when dealing with the stressful situations of cyberbullying were various, and it is probable that they were dependent on other contexts, personal traits, and the respondents’ evolution. One of the most frequently used coping mechanisms was the use of technical aspects of the given tool, which helped restrict communication from the aggressor. To name a few examples:

Contacting administrators (server administrators, Internet help pages, asking mobile providers to block particular numbers) and reporting the user-bully. Blocking the aggressors (putting them on ignore lists on ICQ, Facebook, Lide.cz, Libimseti.cz and Skype). Communicating with the aggressors from a different account/user name (newly created, friend’s account).

Technical coping was the most frequently used mechanism, but it often did not work permanently or was insufficient. One of the reasons for this was the administrators’ disregard for notices of bullying. Even though the respondents reported aggressive users, the administrators did not react:

"I sent them three notices and nothing happened." (female no. 14, age 15)

The 18-year-old female respondent no. 12 found herself in a similar situation as she was trying to prevent the aggressor from contacting her:

"Well I put his address into blocked and I reported him, but I kept getting messages…I do not know whether it was someone’s mistake or it could not be done."

During the same phase, the 17-year-old male no. 10 experienced indirect cyberbullying by administrators. During a chat session, where he was repeatedly bullied and attacked by a female aggressor, the administrators warned the bully but did not deal with the problem any further. Later, male no. 10 became furious about being cyber bullied and used foul language in the chat room – the administrators expelled him from the room instead of looking into the aggressor’s behaviour.

In the case of the 15-year-old female no. 1, the aggressor created a false account on Libimseti.cz, the Czech social networking site, where he published slanderous and negative information and, using the victim’s name, contacted other female users. When she reported this to the administrators, saying that it was a false account and asked for its deletion, no one reacted and the account remains active.

Another limitation of technical coping is the aggressor’s ability to create a new account immediately after having the false account blocked or deleted by the victim. This scenario occurred in the case of the 15-year-old female no. 14 where even after a fifth blockage of the bully’s account, he again created a new one. The 17-year-old female no. 11 blocked her aggressor as well, but the aggressor created a new profile within a week.

In one case, technical coping turned into a disadvantage – after having her photograph stolen and made public on a Facebook-group page, the 18-year-old female no. 15 wanted to delete the photograph, but did not have the administration rights which would allow her to do so. When she tried to contact the female aggressor, who had made the photograph public, it was not possible, because the aggressor had her account protected so well that she could not be contacted by anyone unrequested. In this respondent’s case, cyberbullying is repeated but in a different manner than in traditional bullying: the photograph remains on Facebook which means that cyberbullying did not stop with comments the respondent saw and perceives as bullying, but it may in fact continue due to new comments added by other users.

Coping strategies: Activity Directed at the Aggressor

This involves three communication dimensions which function as expressions of reaction, leading from the victim to the aggressor. They are described here from the weakest to the strongest dimension: Threatening to report the incident to the authorities, the respondents used reporting of cyberbullying as one of their defence mechanisms:

"I said that unless he left me alone I would tell someone." (female no. 5, age 16)

Defensive feedback means emphasising a lack of interest/need to end communication. It can be provided through different communication forms. The first takes the form of a plea to the aggressor:

"Please I do not want to see you again, I have a headache and my mom is angry with me. I do not want to be with you anymore, I am scared of you." (female no. 13, age 15)

The second communication form is that of an order.

"Yeah when there was too much of it I told him I had had enough." (female no. 4, age 14)

The third form is that of an announcement.

"I told him I am not obliged to write to him, that I do not want to write to anyone I do not know, and that I do not want him writing to me ever again." (female no. 7, age 16)

Aggression is an open expression of negative emotions directed at the aggressor. The term "open“ means a direct expression the victim communicates to the aggressor via the channels used for cyberbullying:

"So I gave up and told him to go to hell." (female no. 4, age 14)

Interviewer: "And how did you pay her back."

"I do not remember - it was something vulgar." (male no. 10, age 17)

The 15-year-old female respondent no. 14 reacted in an interesting manner: as bullying was increasing, she did not hesitate to indirectly threaten the bully with violence:

"I got angry and sent him some of my photos from fencing practice and knife throwing."

Inside (hidden) aggression is also understood as a type of aggression, which the victim does not express toward the aggressor in an open and direct way, but rather forms a negative emotion which then helps the victim cope with bullying and helps let off steam. Even though this is a feeling toward the aggressor, this category belongs among coping strategies. Potentially, it represents an opportunity to come to terms with anger the victims cannot express directly at the aggressor as they do not meet the aggressor in person. Generalisations, labelling, or obscenities addressed to the aggressor belong in this category as well. For example, the 17-year-old male respondent no. 10 used labelling as a defence mechanism against his female aggressor even though he only knew her language from the chat room and from cyber-attacks:

"No, she does not say anything about herself, she just curses – I know she is an alcoholic and impulsive and irritable, I remember that."

Vulgar labelling of the aggressor was often used as an expression of anger or even hatred. During the interview, the 15-year-old female respondent no. 1 called the aggressor an "asshole."

"That the asshole would start threatening me even more."

The 15-year-old female respondent no. 3 called the aggressor "the biggest pig of the century," and she used this label during open aggression when she tried to stop communication with the aggressor:

"I do not talk to pigs."

In the case of this respondent, there is a clearly visible development of her approach toward the aggressor. At the beginning, her perception of him was neutral:

"As a normal person, neither as an unimpressive someone who waits somewhere in the corner to be noticed, nor as someone who likes to brag."

Afterwards, her perception changed completely and she started seeing the aggressor as "someone who is not right in the head." (female no. 3, age 15)

The 18-year-old female no. 15 describes her female aggressor in detail with very negative overtones:

"That she is a pathetic pseudo-beauty who thinks she is god knows what, but she is nothing…only idiots care about things like that…and she seems to me like a little stupid kid really."

The 17-year-old male respondent no. 8 considers all aggressors in general as mentally unstable, incapable of keeping a partner; as having trouble meeting people offline. Mental instability or calling the aggressor "ill“ emerged also in the case of the 15-year-old female no. 14 in a similar fashion to labelling and generalisations. For instance, the respondent associated particular symptoms with the aggressor and defined him in detail:

"I think he was hot-tempered and moody, could be hurt easily…I have a feeling that he was schizophrenic or had a persecution complex…I felt really sorry for him…I remember that he was self-conscious about his looks and sometimes there were mistakes in the messages…as if he was talking to someone else but a strange person wrote it, in my view a very ill person."

Coping strategies: Avoiding Stressful Situations

Considering that blocking an aggressor and other types of technical coping which can restrict the aggressor’s activity do not constitute mere passive avoidance it is not included in this section. In fact, technical coping is considered an active attempt at problem solving.

Avoidance did not only occur in cyberspace but also offline in three females respondents, in these cases offline contact was involved. For six months during cyberbullying, female respondent no. 3 walked directly home from school trying to avoid meeting the aggressors. When respondent no. 13 met the aggressor she pretended she was being accompanied by someone; female no. 12 opted for a similar strategy, trying to avoid staying alone with the aggressor on the school premises.

In cyberspace, avoiding took the forms of: not replying; not answering/hanging up the phone; deleting or temporary disabling of the risky online sources of threats, where cyberbullying took/takes place; creating an account at another server.

Offline avoidance took the form of: waiting until the bully stopped; not thinking about the problem, not reacting and not contacting the aggressor.

According to the victims’ statements, this offline avoidance manifested itself in these ways:

"It went away.“ (female no. 5, age 16)

"I guess I tried not to think about it." (female no. 7, age 16)

"I was never rude to him, I did not talk to him about it, I kinda ignored his messages." (female no. 12, age 18)

"I stared out of the window until he went away." (female no. 13, age 15)

Coping strategies: Defensive Strategies (Diversion tactics)

The respondents sought numerous offline activities and devoted their time to them in order draw their attention away from the reality of bullying:

Excessive consumption of food became a tool which helped suppress the victims’ fear of the aggressor: "In the morning straight to school and then straight back from school and then the rest of the day at home, and as I was scared I was just eating eating eating…" (female no. 3, 15 years)

Devoting attention to hobbies (horses, music, collecting cars, reading) and sports and exercise. Much like the excessive consumption of food, hobbies and sports gave the victims an opportunity to take their minds off their problems and forget that something bad is happening in their lives, or it provided them with a way of coping with their fear of the aggressor:

"I play sports a lot and I do it competitively. It always helps me to go to practice where there is no time to think." (female no. 7, age 16)

The 15-year-old female no. 13 perceived sport as a way of coping with her fear of the aggressor:

"It lets off steam and nerves..learn to live with the fear."

Coping strategies: Personal psychical help

Manifested in the form of own defence mechanisms which were successful in the cases of cyberbullying. In particular, sport activities had such effect on the female victim that it gave her a sense of comfort because she became able to defend herself:

"I always squeezed the blade of my favourite sword more firmly in my hand…I feel completely safe with it…I know I can use it 100%." (female no. 14, age 15)

A safe social environment helped the respondents not to think about the situation; instead they focused on the hospitable environment. "When I was somewhere among people and did not have to think about it." (female no. 11, age 16)

Trivialising and generalising the situation was opted for as a defence mechanism by the victims when they did not want to fully admit the existence of cyberbullying. "I usually send him smileys…like I do not take him seriously." (female no. 12, age 18)

Trivialising occurred in the case of the 17-year-old male respondent no. 10 and the 15-year-old female respondent no. 14 who pointed out how widespread cyberbullying is. They emphasized the commonality of the phenomenon and their attitude was similar to "it can happen to anyone".

"I mean it is happening all around and all the time…I think that if every other girl could talk, she would tell you the same things, maybe even worse…" (female no. 14, age 15)

Coping strategies: Social Support

Seeking social support as a method of coping with this bothersome situation involved many dimensions:

Confiding and receiving positive feedback and help was the most widely used form of social support. It was used by ten respondents. It took various forms, which the respondents perceived as helpful: The first form was reassurance;"When he was outside with me he reassured me that nothing bad would happen.“ (Female no. 1, age 15)

The second was psychical support;

"Well they understood and tried to help, Tina went with me to see the mobile provider." (Female no. 4, age 14)

"I mean she helped me with her talks, like she kept my head above the water." (Female no. 6, 15 years)

"I remember that they accompanied me to my house and waited until I waved from the window that I was ok." (female no. 13, age 15)

Sharing bad experiences – in the cases of two respondents (the 16-year-old female no. 5 and the 15-year-old female no. 14), their friends found themselves in a similar or identical situation and could thus share their experiences:

"We understood one another, but I felt sorry for her because she got it worse." (female no. 5, age 16)

Trivialising and making fun of bullying:

"He helped me by deleting it and we laughed at it together." (female no. 7, age 16)

Actually dealing with the aggressor;

"A friend of mine who helps me started dealing with it and told me to keep writing the guy and when he is on ICQ I should tell him and that he will log onto my ICQ and will take care of it." (female no. 11, age 16)

"But he stopped because I think my mum wrote to him" (female no. 6, age 15)

Friends of the 18-year-old female respondent no. 15 dealt with the aggressor indirectly as they took part in the discussion under her stolen photograph. The respondent felt positive about this:

"I felt relieved…and, mainly, they supported me."

Not confiding in anyone occurred in the cases of five respondents. Male no. 8 explained that he did not want to trouble his girlfriend with issues which were mere trifles for him. Female respondent no. 2 feels guilty for her situation and this was why she did not confide: "I thought that since I caused it I have to help myself." During the first of her two experiences with cyberbullying, female respondent no. 3 also pointed out that she would rather deal with her problems by herself:

"I will gladly combat my issues."

Male respondent no. 10 did not want to "add to the worries" of his parents and friends, and he also thought they would not understand the situation and their reaction would be exaggerated:

"I did not tell anyone because if I had told my parents they would have immediately called the cops and I do not want that."

Another aspect of social support is its source. It is important to differentiate between confiding in friends and in family. Many respondents were too worried about their parents’ reactions to confide in them. These worries can be strongly connected to family set-up and principles. For instance, the 15-year-old female respondent no. 13 confided in her friends who then notified the respondent’s stepmother. However, the stepmother ignored the situation and even accused the respondent of making the problem up:

"Yes, to my best friend. She told my stepmother but she did not like me and she did not care, she said I was making stuff up."

There were seven instances of respondents being helped only by friends, not by family. Some of the respondents mentioned why they did not tell their parents about cyberbullying. Female no. 1 – in a similar manner to male no. 10 above – quoted her mother’s reaction. The respondent told her mother about being bullied by someone she met on the Internet and the mother reacted by calling the police: That is why the respondent did not confide in her again:

Interviewer: "And why did you not tell them?"

Respondent: "Dunno, I was afraid, my mum had already gone to the police because one guy wrote some rude text messages to me."

Female respondent no. 15 thinks that it would "be too much" for her parents, even though she knows they would support her. But they do not know anything about this issue.

"They do not understand the Internet and I have no desire to explain it to them time and again…I only have one set of nerves"

Thus, the respondents did not look for help from their parents because they thought that their parents would not understand the situation or would overreact – by contacting the police. In the case of female no. 13 the cause may have been the disruptive environment she had been growing up in, and so even though her stepmother did know about the bullying, she did not help the respondent.

However, in four cases parents were perceived as positive social support, both present and helpful in dealing with cyberbullying. Female no. 6, whose mother solved her daughter‘s problems with cyberbullying and was supportive the whole time, described what particular social support had been provided by her mother, and added that her mother supports her in every situation:

Respondent: "She held me, told me things that calmed me down…I mean she said things that helped me, she held my head above the water in this way."

Interviewer: "I understand, and what did she tell you, for example ?"

Respondent: "That I am a pretty girl, that I should not do anything silly and look for someone on the Internet, that I can find a nice guy and that the one who is writing to me does not mean anything, that it will stop, that I will fall in love and get disappointed again many times."

The 16-year-old female respondent no. 7 regrets the fact that her parents did not supervise her online activities more when she was ten years old, the time period when she experienced cyberbullying for the first time:

"I am definitely supportive of parents checking their children’s net and messages. Too bad my parents did not do that. I am definitely going to do that."

The reasons for seeking and not seeking social support can be diverse and the respondents explained them in some cases using their own personal characteristics. The 16-year-old female no. 7 called herself the "type of person who holds everything inside;" as opposed to the 18-year-old female no. 12, who explained her reason for confiding in her sister and her friends in these words: "I love to talk and so when it comes to it, I say it.." The 15-year-old female respondent no. 13 explains the reason why she did not want her friends to act against the aggressor even though she told them about her experience with traditional and cyberbullying:

Interviewer: "And did they want to deal with him in some way?"

Respondent: "... the gipsy? It is not easy, yeah they did but they did not do anything and mainly I did not want them to, he was a psycho and I will not let anyone get his ass kicked for me."

In the case of this female respondent, one can also see another possible influence on the respondent’s actions – the environment in which she grew up, the geographical region where the respondent lives. This area is characterised by cohabitation and code mixing of the language of Czech youngsters and Roma youngsters – the respondent points this out in the very first message her aggressor wrote to her. He used the expression "čáje" which the respondent explains "means ‘chick’“ in the Roma language…here in the city we use some words borrowed from their language."

The environmental and educational contexts of the respondents also possibly influenced what occurred. For example, in the case of the 15-year-old female no. 6 a probable protective attitude existed on the part of her mother. She was the only parent, with the exception of the 14-year-old female no. 4’s parents, who signed the informed consent form, and who showed interest in the research and was worried about its authenticity. She was subsequently sent an explanatory e-mail.

Discussion

In the present study, two essential phenomena connected with cyberbullying are presented, as described by the respondents: impacts and consequences of cyberbullying and the coping strategies in cyberbullying.

In this study, the impacts and consequences of cyberbullying refer to changes in online behaviour and its offline psychological impact. It has been discovered that, apart from the emotional impact, the consequences of cyberbullying can be perceived as positive in the form of cyberspace behavioural changes. Subjectively speaking, this occurred mainly where a cognitive pattern for bullies was created, allowing the victims to more easily recognise bullies due to their experience with cyberbullying. As one female respondent stated: "I certainly have changed ... I learned how to tell what people are like quite well ... who they are, and I need 5 words and then I know whether or not to end the conversation." Bullying also provoked feelings of caution, and brought about restrictions in the use of risky online sources of threats in order to prevent the recurrence of the phenomenon. This implies that the cyberbullying’s impact on the victim causes them to create preventive coping methods, partly as described by Parris et al. (2011); in their research, they asked students (non-victims) about what a person can do to cope with threatening online communication. Students also often mentioned increased security and awareness as something to avoid the situation at first (not just after being bullied) and that it is good to know that something like that can actually happen. In our respondents, the awareness of the fact that cyberbullying can actually happen through being victimized was actually something that made them change their behaviour greatly. The experience of cyberbullying can therefore be considered as having some positive traits, as we assume from the subjective opinions of our respondents. Also, in the study of Parris et al. (2011), there were respondents who stated that there is no way to prevent cyberbullying; and those were non-victims (or at least researchers did not know). It is thus an interesting insight into victims' experience as direct victims of cyberbullying can develop a clear idea of how to accomplish this, and how to behave in the future in order to reduce new potential risks.

Some critical impacts occurred in the form of lowered self-esteem and loneliness. This was also found in the research of Campfield (2006), and was confirmed by Price and Dalgleish, where it was found that the most frequent impacts of cyberbullying were lowered self-esteem (78%) and self-evaluation (70%). We are aware that this also depends on the particular person and his or her story and social context, but this is perhaps something that various studies could confirm, using different designs across cultural contexts. It is very similar regarding distrust - in the present study, in the cases of the six female respondents, cyberbullying brought about a disillusionment in, and distrust of people, which corresponds to the findings of Dehue et al. (2008), who mention the category of reaction to cyberbullying: "I don’t trust other boys and girls any more." (p. 220).

The more serious impacts of cyberbullying took the form of self-harm, which also occurred in some cases in the research by Price and Dalgleish (2010) – 2% of respondents started harming themselves due to cyberbullying. Of course, there are many variables (both situational and personal and - as self-harming is increasingly common in adolescents in general - even cultural) that make a person vulnerable to do this, but it is useful to keep in mind that self-harming might come along with other serious conditions in cyberbullying victims, and that both cyberbullying and self-harming are very often barely visible to anyone who might help.

Coping strategies, as described by the respondents in the present study, included technical coping, activity directed at the aggressor, avoidance, defensive strategies, and social support. The coping mechanism of avoidance is connected to the basic coping mechanisms of displacement and repression by Freud (1946). As a coping strategy, avoidance occurs also in Parris et al. (2011) and Price and Dalgleish (2010). While avoidance can be understood as the avoidance-mode, it is important to distinguish between consciously choosing to avoid or ignore, which the victim may opt for after considering all possibilities and deciding it is the most efficient mechanism; and avoidance as in "closing one’s eyes“ to reality, experiencing an intense feeling of helplessness. The fact that ignoring it can be an efficient way of coping with cyberbullying was also mentioned by respondents in Parris et al. (2011). On the other hand, one of our respondents perceived avoidance as a lack of possibilities to protect herself - "It’s horrible because I know I can’t do anything, just ignore him and delete". We would like to emphasize the contrast, which we saw in this regard, seeing our respondents' stories. It is thus another reminder for us to keep in mind how important it is to be careful while interpreting any data, especially quantitative where it is difficult to see context and personal reasons for choosing avoidance or ignorance, or, in general, any coping strategy.

The mechanism of sublimation is also described as one of Freud’s defence mechanisms – it corresponds to seeking defensive strategies and focusing on an alternative goal. This occurred, for example, in the cases of the female respondents who did or, after experiencing cyberbullying, started doing sports competitively. Trivialising and generalising the situation also falls into the defensive strategies category – the respondents did not take the situation seriously or they justified it, stating that it is common and pointing out its wide range of impacts. This strategy corresponds to research by Parris et al. (2011), where it is called justification. This can be considered both as emotional and as cognitive coping. The coping strategy of seeking social support also matches the findings in Parris et al. (2011), who quote social support as one of the basic coping mechanisms. Activity directed at the aggressor which, along with notifying the aggressor about unrequested contact, manifested itself also in the incidence of internal or open aggression, could be assessed as a ground-breaking element in the distinction between problem-focused and emotion-focused coping (Lazarus, 1984). This aggression is manifested directly at the aggressor with the aim of enabling emotional coping releasing negative emotions and letting off anger at the aggressor, emotions which cannot be let off offline. Yet again, it needs to be pointed out that the classification of coping strategies into categories can be problematic and depends on the type of measuring tool used (Riebel, Jäger & Fischer, 2009). Some coping strategies can also be classified in more than one category, even opposing ones (e.g. problem-focused and emotion-focused) (Parris et al., 2011).

Technical coping was the most frequently used mechanism, but it often did not work permanently or was insufficient. One of the reasons for this was the administrators’ disregard for notices of bullying. Even though the respondents reported aggressive users (sometimes repeatedly) the administrators did not react. As a result, the respondents perceived technical coping as insufficient. This can be identified as indirect bullying, when adults – in this case administrators – indirectly help aggressor to bully the victim. The fact that technical coping failed so many times and in so many ways (nothing happened vs. indirect bullying occured) was quite surprising. It is often said that contrary to traditional bullying, victims of cyberbullying can use wide variety of tools, which are not available offline (Price & Dalgleish, 2010). Also, it is often suggested to young people that they should take advantage of these tools and use them whenever they feel threatened. As studies regarding the effectiveness of particular coping strategies are still missing, we strongly suggest this to be addressed in future research, either to confirm that or acquire some more information.

There were instances of respondents being helped only by friends, not by family. Some of the respondents mentioned why they did not tell their parents about cyberbullying. As one of our respondents quoted her mother’s reaction - after being bullied by someone the respondent met on the Internet the mother reacted by calling the police. That is why the respondent did not confide in her again. The fact that adolescents tend not to tell their parents about cyberbullying is also quoted in other studies (Riebel et al., 2009); the victims of cyberbullying have a higher tendency, as opposed to the victims of traditional bullying, to not speak about the event to anyone, and not to seek any help (Dehue et al., 2008; Li, 2006; Heirman & Walrave, 2008), or rather to tell only their friends (Slonje & Smith, 2008). The reasons may vary – some studies quote, for example, fear of parents forbidding the use of technologies, or restricting their usage in uncomfortable ways (Kowalski et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2008). Our respondents quoted similar fears of their parents overreacting. However, in the previous studies researchers either just asked the victims if they have told someone and, given the limits of the focus of the particular study or instrument used, could not further search for reasons (and just attributed some); or their respondents were not victims but students, asked something like "what would they do, if...“. For us, it was important to get a deeper understanding of what actual victims felt and thought about telling parents or peers when it happened, and what reasons did they have for not telling. Based on our findings, we suggest that besides the technical part (digital divide) it is the overall situation in the family (e.g. if parents are divorced, who the young person lives with and many more) that has a strong impact on adolescent behaviour regarding this. However, the main point is that the respondents feared that their parents would not understand their situation (also in the sense that the parents do not know how cyber reality works and do not understand it) (Campbell, 2005) or they stated that they would rather deal with the situation themselves, which can be connected with both the previous reasons. Another reason why cyberbullying victims may avoid confiding in their parents and also, for example, in their friends, is a feeling that not only is there no way to prevent cyberbullying, but also while it occurs, there is nothing at all anyone can do about it (Mishna et al., 2009; Smith, et al., 2008). Feelings of helplessness were repeatedly mentioned by the respondents. The fact is that, as mentioned above, technical coping, though some respondents tried using it, did not work at all, or not in a sufficiently to prevent another threat (the administrators do not react or react insufficiently, the bully creates a new account and continues attacking etc.). This may spur a discussion on how to adequately ensure that the technological side does not lag behind the increasing risks. The feeling of helplessness may be also closely connected to the failure of technical support, the inappropriate reactions of parents, or to the feeling that parents cannot help.

Campfield (2006) mentions an interesting manifestation in one victim – trivialising, wherein the victims do not even realise that cyberbullying is something wrong because the event takes place outside of reality. This also occurred in our respondents, and was not always related to "outside reality“ reason. Some of our respondents just looked at cyberbullying as something that happens all the time to different people. It is a question whether this attitude is positive, as it seems to ensure that the victim is not strongly affected by cyberbullying, or if we should be concerned, as trivialising in one case could lead to trivialising the situation globally.

In our study, we are aware of some limitations that should be mentioned. The first limitation is the size of the sample. It is quite difficult to find victims of cyberbullying, who are willing to talk about their experiences or who have actually had any experience with cyberbullying. Despite taking the rather small size of our sample into account, we think that our categories were saturated, as is needed in qualitative approach.

Another limitation is the terminology. The term cyberbullying is not clearly conceptualised yet. As can be observed in numerous studies, the terms cyberbullying, cyberharrasment and cyberstalking are often used interchangeably. This is why we are working with cyberbullying as a fluid term – in the future our results can be used, read and interpreted differently.

Also, we decided to do interviews via Internet – using ICQ or Skype chat – because we wanted to keep victims anonymous and safe, with the possibilities given by online environment regarding self-disclosure. However, we are aware of the possibility of face-to-face interview and the fact that these could bring different results, e.g. by focusing on nonverbal clues. Moreover, the online environment is the place where cyberbullying takes place; we are well aware that that could be a factor making victims feel uncomfortable or unsafe. Another problem in our interviews is that one can see a slight rigidity due to the use of semi-structured interviews. Due to this rigidity, the data from the first respondents may be more extensive. Later, we continuously modified the structure of the interviews and the answers were more detailed.

The last limitation is that the study is situated in the Czech cultural context. Therefore, our findings have to be interpreted with regard to Czech cultural context. The psychosocial context of the victims and their environment appears in the study indirectly in those statements where victims described relationships and the reactions by their parents or friends. It is evident that these relationships influence the victims’ view of cyberbullying, in particular the impacts of, and solutions to it. A hypothesis worth exploring is that if the adolescents live in a stable family-and-friend environment, they cope with cyberbullying better and their cyberbullying experience is not as strong as those whose family environment is unstable and disrupted. So far, this hypothesis has only been explored in the psychosocial study by Sourander et al. (2010).

Another possible research could be into the issue of bystanders: parents and peers, who are aware of cyberbullying and who, for example, help the victim deal with it. This is a possible and desirable focus for subsequent studies – prevention of this phenomenon.

It remains unanswered whether the parents of adolescents are really so technically illiterate as far as virtual reality is concerned. As mentioned above, the respondents mentioned that their parents do not understand the issue and that they would overreact or would not understand this bullying at all. Teaching the issue of cyberbullying to parents, and highlighting the dangers and possible solutions to cyberbullying when it occurs can be a form of prevention. It is also essential in the preventive context, to focus on younger children who are starting to work with the Internet.

Based on our findings, we concluded that the victims of cyberbullying perceive and cope with it in different ways, which may be affected by many other factors. According to that, it would be useful to focus on connecting cyberbullying (i.e. telling parents, emotional impact of cyberbullying) with the psychosocial contexts of the victims, their educational environment, and other contextual variables which influence the victims (see e.g. Campfield, 2006; Sourander et al., 2010).

Also, as mentioned above, further research should be done on the success and efficiency of different coping strategies, as there is generally not a lot known about the efficiency of different strategies (Parris et al., 2011). Acquiring this information is important in terms of prevention and education of both children and adults.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (LD11008, MSM0021622406), the Czech Science Foundation (GAP407/11/0585) and the Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University.

References

Aftab, P. (n.d.). wired SAFETY. Retrieved from http://www.wiredsafety.org/

Beran, L., & Li. Q. (2005). Cyber-Harassment: A Study of a New Method for an Old Behavior. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 32, 265-277. Retrieved from http://people.ucalgary.ca/.../2005CyberBeranLi_JECR.pdf

Campfield, D. C. (2006). Cyberbullying and victimization: Psychosocial Characteristics of Bullies, Victims, and Bully-victims (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://etd.lib.umt.edu/theses/available/.../umi-umt-1107.pdf

Campbell, M. (2005). Cyber bullying: An old problem in a new guise? Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 15, 68-76.

Coomber, R. (1997). Using the Internet for survey research. Sociological Research Online, 2(2). Retrieved from http://www.socresonline.org.uk/2/2/2.html

Coyne, I., & Monks, C. P. (2011). An Overview of Bullying and Abuse. In C. P. Monks & I. Coyne (Eds.), Bullying in Different Contexts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dehue, F., Bolman, C., & Völlink, T. (2008). Cyberbullying: Youngster’s Experiences and Parental Perception. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11, 217-332.

Freud, A. (1946). The ego and the mechanisms of defense. New York: International Universities Press.

Heirman, W., & Walrave, M. (2008). Assessing concerns and issues about the mediation of technology in cyberbullying. Cyberpsychology, 2, 1-11. Retreived from http://www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2008111401

Hinduja. S. & Patchin, J. V. (2010). Bullying, Cyberbullying and Suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 14, 206-221. Retrieved from http://pdfserve.informaworld.com/864382_935828505_924722304.pdf

Joinson, A. N. (2001). Self-disclosure in computer-mediated communication: The role of self-awareness and visual anonymity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31, 177-192.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkmann, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and doping. New York: Springer.

Lupač, P., & Sládek, J. (2008). The Deepening of the Digital Divide in the Czech Republic. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 2(1), article 2. Retrieved from http://cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2008060203&article=2

Mishna, F., Saini, M., & Solomon, S. (2009). Ongoing and online: Children and youth's perceptions of cyberbullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 1222-1228.

Parris, L., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., & Cutts, H. (2011). High School Student’s Perceptions of Coping With Cyberbullying. Youth & Society, 20, 1-23.

Price, M., & Dalgleish, J. (2010). Cyberbullying: Experiences, impacts and coping strategies as described by Australian young people. Youth Studies Australia, 29, 51-59.

Riebel, J., Jäger, R. S., & Fischer, U. C. (2009). Cyberbullying in Germany – an exploration of prevalence, overlapping with real life bullying and coping strategies. Psychology Science Quarterly, 51, 298-314.

Roth, S., & Cohen, L. J. (1986). Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist, 41, 813-819.

Shariff, S., & Churchill, A. H. (Eds.). (2010). Truths and Myths of Cyber-bullying: International Perspectives on Stakeholder Responsibility and Children's Safety. New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien: New Literacies and Digital Epistemologies.

Skinner, E., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 216-269.

Smith, P. K., & Slonje, R. (2007). Cyberbullying: the nature and extent of a new kind of bullying, in and out of school In S. R. Jimerson (Ed.), The International Handbook of School Bullying. New York: Routledge.

Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 376–385.

Snyder, C. R. (1999). Coping: The Psychology of What Works. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sourander, A., Klomek , A. B., Ikonen, M., Lindroos, J., Luntamo, T., Koskelainen, M. Ristkari, T., & Helenius, H. (2010). Psychosocial Risk Factors Associated With Cyberbullying Among Adolescents: A Population-Based Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 67, 720-728.

Staksrud, E. & Livingstone, S. (2007). Children and online risk: powerless victims or resourceful participants? Information, communication and society, 12, 364-387.

Subbiah, L., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., & Parris, L. (in press). Coping with bullying: Victims’ self-reported coping strategies and perceived effectiveness.

Ševčíková, A., & Šmahel, D. (2009). Online Harassment and Cyberbullying in the Czech Republic: Comparison Across Age Groups. Zeitschrift für Psychologie / Journal of Psychology, 217, 227-229.

Šmahel, D., & Lupač, P. (2008). The Internet in Czech Republic 2008: Four Years of WIP in the Czech Repubilc. Retrieved from World Internet Project website: http://www.worldinternetproject.net/_files/_Published/_oldis/Czech_Republic_2008_Four%20Years.pdf

Tenenbaum, L. S., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., & Parris, L. (2011). Coping strategies and perceived effectiveness in fourth through eighth grade victims of bullying. School Psychology International, 32, 263–287.

Wolak, J., Mitchell, K., & Finkelhor, D. (2006). Online Victimization of Youth: Five Years Later. National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. Retrieved from http://www.missingkids.com/en_US/publications/NC167.pdf

Ybarra, M., Espelage, D. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2007). The Co-occurrence of Internet Harassment and Unwanted Sexual Solicitation Victimization and Perpetration: Associations with Psychosocial Indicators. Journal of Adolescent Health, 4, 31–41.

Correspondence to:

Alena Černá

Institute for Research on Children, Youth and Family

Faculty of Social Studies

Masaryk University

Jostova 10

60200 Brno

The Czech Republic

e-mail: cernaale(at)gmail.com