An exploration of the relationship between real-world sexual experience and online sexual activity among 17 year old adolescents

Anna Sevcikova1, Štěpán Konečný2

Abstract

Keywords: adolescence, sexuality, Internet, Czech Republic

Introduction

One of the many life stage virtues in adolescence is the development of physical and emotional intimacy in relationships with others (Collins & Sroufe, 1999; Erikson, 1968; Weinstein & Rosen, 1991) the topic of sexuality being particularly emphasized during this period. A great number of teenagers become sexually active during adolescence (Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2004) when undergoing physiological changes that lead to an increased interest in sex (Weinstein & Rosen, 1991). With increasing age the importance of the sexual dimension and sexual experience grows (Furman & Werner, 1997; Weinberg Lottes, & Shaver, 1995; Weiss & Zvěřina, 2004).

Prior research has shown that adolescents may have experience in several offline sexual activities such as autoerotic activities (Halpern, Udry, Suchindran, & Campbell, 2000) and necking or petting (Weiss & Zvěřina, 2004). Further, some have already had intercourse or practiced oral sex (Weinberg et al., 1995). Younger adolescents also report sexual behaviour. For example, in one study three quarters of both sexes were found to have engaged in talking about sex, kissing and hugging, watching or reading pornography (primarily boys), and humping or feigning intercourse before age 12 (Larsson & Svedin, 2002). Based on another study, over 80% of youth had participated in non-coital, partnered sexual activities (typically mutual masturbation and oral-genital contact) before age 16 (Bauserman & Davis, 1996). Late adolescence is the time of coital debut; the sexual debut of women occurs on average at the age of 17, and for men on average at the age of 16 (Baumeister, 2000; DeLamater & Friedrich, 2002; Hopkins, 2000). Placing this in a Czech context, most adolescents experience their first coitus at the age of 17-18 (Weiss & Zvěřina, 2004). In summary, the aforementioned studies show that adolescents behave sexually and that the issue of sexuality becomes very topical in their lives. This can manifest as an increased need to come in contact with themes related to sex, or to engage in sex-related issues. Adolescent sexual development mostly occurs within the context of romantic relationships (Brown, Feiring, & Furman, 1999). However, in recent times adolescents have also begun to turn to the Internet as a source for the development of their interests in sex-related issues.

Sexual activities on the Internet

The Internet can be understood as an environment providing easy access to various material of a sexual nature in an anonymous setting (Cooper, 1998). It was found that adolescents, for whom sexuality is an important developmental issue, are active in using the Internet in a sexually related context for various purposes: (a) They seek answers to their questions regarding sexuality and health online (Boies, 2002; Graya, Klein, Noyce, Sesselberg, & Cantrill, 2005; Subrahmanyam, 2007; Suzuki & Calzo, 2004). (b) They discuss sexually relevant topics and take part in sexually-tinged conversations (Subrahmanyam, Smahel, & Greenfield, 2006; Smahel & Subrahmanyam, 2007). (c) They experience cybersex (Vybíral, Smahel, & Divínová, 2004). (d) They search for romantic partners on the Internet, namely in chat rooms (Smahel & Subrahmanyam, 2007). (e) In the context of seeking romantic partners they create sexual self-representations (Siibak, 2009; Subrahmanyam, Greenfield, & Tynes, 2004; Subrahmanyam et al., 2006). To conclude, adolescents engage in various online sexual activities, this can include any activity that involves sexuality for purposes such as recreation, entertainment, exploration, support, education or romantic partner seeking (Cooper & Griffin-Shelley, 2002).

Czech adolescents appear to be active in using the Internet for sexual purposes. A study of 681 12- to 20-year-olds showed that 16% of teenage boys and 15% of teenage girls engaged in “virtual sexual” activities (Smahel, 2006). Additionally, no differences were found among the age groups of 12-14, 15-17 and 18-20 year olds. Adolescents are also unique in utilizing sexual content. Although the percentage range of adolescents being exposed to sexually explicit materials at a young age varies across countries (Livingstone, Haddon, Goerzig, & Ólafsson, 2010; Peter & Valkenburg, 2006; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2005) a representative survey has shown that the Czech Republic has the 2nd highest rate in Europe of adolescent exposure to sexual images online, 29% (Livingstone et al., 2010). Further, Czech teens seem to be very experienced in sending or posting sexual messages on the Internet, with 11 % reporting this activity, the highest reported percentage in Europe (Livingstone et al., 2010).

A sex-oriented literature review made by Subrahmanyam and Smahel (2010) shows that research on creating sexually relevant content (construction of sexual selves online) and online sexual interaction seems to be eclipsed by research focused on exposure to sexually explicit media (the Internet included) at a young age and its impact on attitudes towards an adolescents´ sexuality and sexual behaviour in physical life (see Braun-Courville & Rojas, 2008; Brown & L’Engle, 2009; Flood, 2007; Lo & Wei, 2005; Peter & Valkenburg, 2006; Wolak, Mitchell & Finkelhor, 2007 etc.). In other words, the relationship between sexually related online activities and sexual behaviour in physical life among adolescents was predominantly studied in the context of exposure to sexually explicit online materials. However, the ways in which adolescents are involved in sex related themes online seems to be broader. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to shed light on the relationship between using the Internet for sexual purposes and sexual experience gained in real life among older adolescents, in particular, among 17-year-olds who are familiar with the Internet (Lupač & Sládek, 2008).

Hypotheses in the context of current studies

The relationship between online sexual activities and offline sexual behaviour can be viewed similarly to the broader comparison of behaviour on the Internet with that in real life. According to Smahel (2003), behaviour on the Internet and in physical life corresponds to the actual state of an adolescent´s identity, with one apparent difference: the safe environment of the Internet allows adolescents to experiment more with their own sexuality (Subrahmanyam et al., 2004). Furthermore, adolescents in the environment of so-called weblogs look not only for continuity with their identity as presented in real life, but also for affirmation of their own self-representation among peers, and among their online friends (Huffaker & Calvert, 2005). This interconnectedness of virtual and real life has been confirmed in other studies, which show that adolescents on the Internet affiliate with people they already know in their offline lives (Gross, 2004) or that they use the Internet to intensify their real life love relationships (Subrahmanyam & Greenfield, 2008). Based on the concept of continuity of the adolescents´ lives offline and online, it is possible to assume that offline sexual behaviour is reflected in the use of the Internet.

H1: Adolescents who have no off-line sexual experience will use the Internet less for sexual purposes than adolescents who have off-line sexual experience.

The first hypothesis claims there is a difference between the off-line sexually experienced and the inexperienced. The second hypothesis develops this further and tests whether online sexual practices increase gradually in line with offline experience.

H2: There will be differences in the extent of Internet use for sexual purposes between adolescents who have kissed, petted, had oral sex, and had sexual intercourse.

Method

Participants

For this cross-sectional study a sample was taken from a Czech longitudinal research project, a part of the European Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood (ELSPAC). The Czech part of this project has been running since 1991, when the research sample consisted of all children whose residential addresses were in the city of Brno and who were born in the period March 1st 1991 – June 30th 1992 (approximately 5000 families) and all children whose residential addresses were in the district of Znojmo and were born between April 1st 1991 and June 30th 1992 (approximately 1500 families). Since the prenatal period the mothers of the respondents have repeatedly completed questionnaires. Since 1999, the respondents have taken part in broader psychological assessments. These have taken place at intervals of about 2-3 years, when the respondents were 8, 11, 13, 15 and 17 years old. The present study was conducted on 462 respondents (237 girls and 225 boys) of those families remaining active in the longitudinal study. It was carried out within the last wider examination in 2008/2009 when the respondents reached the age of 17. The respondents were sent a letter asking them to participate in our research. Despite the amount of longitudinal data from previous research waves it was not possible to monitor any trends in this area as our research, concerned with sexual behaviour on the Internet, was presented to the respondents for the first time.

Procedure

Respondents who agreed to participate in the research were invited to the Institute where they were asked to fill in computer-administered questionnaires. These included questions related to sexual behaviour in real life, and online sexual activities. Computer administration of the questionnaires ensured anonymity which is crucial when responding to such sensitive issues. Because of the significant amount of time required, the respondents were allowed to interrupt filling in their questionnaires whenever they wished to and to return to them at a later time, usually at home via the Internet. However, they could not change their previous answers when they logged on again from a different location.

Measurement

This study was preceded by a pilot study of 110 participants. Through this pilot study the most common sexual behaviours of adolescents on the Internet were looked at. This helped refine the wording of the questions concerning online sexual activities. A list of these activities included, obtaining information about sex on the Internet, talking about sex, talking about sexual experiences, exchanging erotic photos, and experimenting with “sex on the Internet”. Individuals were asked whether they had looked for sex-related information such as sexual guidelines and problems, not erotic videos or photos. Online sexually related interaction was measured through questions about whether participants had talked about sex, whether they had discussed their own sexual experience or whether they had discussed their online partner´s sexual experience, and whether this had happened with known or unknown people. Further, respondents were asked whether they had sent erotic photos of themselves to others, or received erotic photos from others. And finally, they were asked whether they had ever tried to have online sex with someone.

A graded scale (1 = never, 2 = only once, 3 = several times over the past year, 4 = at least once a month, and 5 = at least once a week) was used to measure the extent of internet use for sexual activities. However, because of low frequency at the extreme ends of the scale this was later changed to only one interval. A scale was created by summing each of the ten items. A higher score indicated greater experience with using the internet for sexual purposes. The scale had good internal consistency (α = 0. 872).

The second series of questions dealt with offline sexual behaviour, with a special focus on having experience with “kissing”, “petting, embracing, caressing intimate parts”, “oral sex”, and “sexual intercourse”. Non-coital sexual activities were considered to precede intercourse (Weinberg et al.,1995; Weiss & Zvěřina, 2001). Due to the normal distribution of the collected data we used T-tests and Pearson correlations in SPSS v. 15.

Results

For adolescents actual real life sexual activities were more frequent than online sexual activities, as proven by our results. Real sexual activities occurred among 54 - 90% of participants depending on the type of activity; whereas 12 - 60% had been involved in different kinds of online sexual experiences (see Table 1 for details).

Adolescents confirmed the highly sensitive nature of the topic through their reduced willingness to answer questions concerning oral sex and sexual intercourse experience. These were skipped by 52% of participants. The most common real-life sexual activity was kissing and the least common was sexual intercourse. The only difference between boys and girls was found in petting, where girls reported petting with someone more often than boys did, χ2 (1) = 8,87, p< 0.01. Concerning virtual sex life, the most frequent sexual activity was communication about sex, and about the sexual experiences of themselves or others. The least frequent was sending erotic photos of themselves and having sex on the Internet.

To discover the possible relationship between real-life sexual experiences and sexual activities on the Internet the participants were split into two groups. The first group contained those adolescents who had reported any offline sexual experience (such as “kissing”, “petting, embracing or caressing intimate parts”, “oral sex”, and “sexual intercourse”). The second group was made up of those who indicated that they had never kissed, petted, had oral sex, or sexual intercourse with anyone. Both groups were compared based on their level of online sexual activities (by t-test).

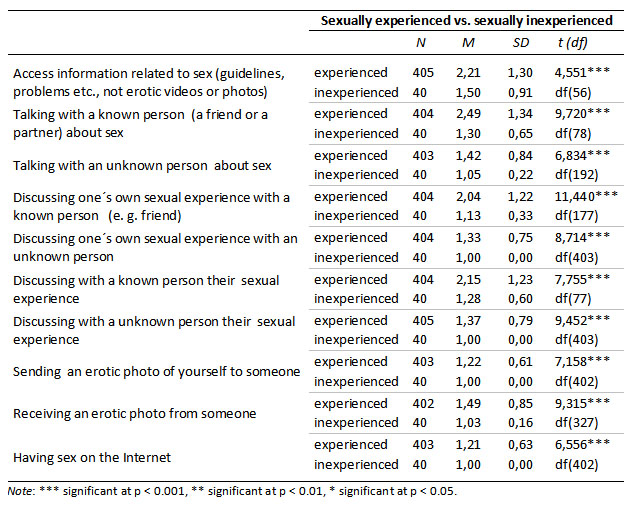

As Table 2 indicates, sexually experienced adolescents were significantly more interested in sexual contents and communication on the Internet than inexperienced ones. At the same time it is apparent that even those more sexually experienced adolescents had relatively low scores on this scale (1.21 to 2.49). We may conclude that hypothesis 1, which assumes that there is a difference between the off-line sexually experienced and the inexperienced, was confirmed.

In order to test the second assumption regarding the relationship between the growth of sexual experience offline, and the growth in Internet use for sexual purposes, four mutually exclusive groups were created. The first group included only those adolescents who had kissed; the second, only those who had kissed and simultaneously petted; the third, only those who had experienced oral sex, kissing and petting; and the final group included only those who had experience with sexual intercourse including kissing, petting or oral sex. The groups were mutually exclusive in that the highest level of experience was used as the defining characteristic, e.g. those with kissing, petting and oral sex experience were excluded from the groups “experience with kissing” and “experience with petting” and grouped in “experience with oral sex”.

In Table 3 adolescents who had kissed are compared with those who had never experienced an intimate kiss. Table 4 shows the findings from the comparison of those who had kissed and petted offline and those who reported no petting.

In Table 5 individuals who had experience with kissing, petting, and oral sex are compared with those who had not had oral sex. Finally in Table 6 individuals who had experience with kissing, petting, oral sex and sexual intercourse are compared with those who did not report any sexual intercourse. Due to a gradual distinction in the level of sexual experience, t-tests were used to analyse how individuals with different real life sexual experience differed in using the Internet.

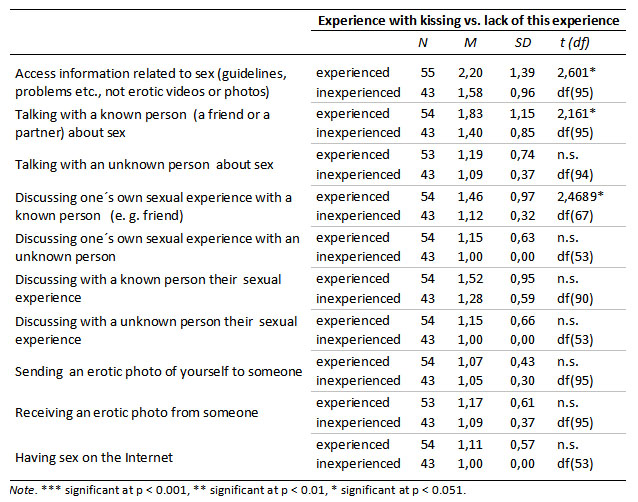

From Table 3 it is apparent that individuals with kissing experience used the Internet to search for sexually relevant information, to talk about sex with a known person, and to share their sexual experiences more often than those adolescents who had no kissing experience. The only significant difference between adolescents with or without experience with petting was found in the frequency of accessing information related to sex (see Table 4). The most interesting thing was that it was the only significant case where inexperienced individuals were more active on the Internet than experienced ones.

From Table 5 and Table 6 is evident that the next two levels of sexual activity documented an increasing interest in internet use for sexual purposes among our respondents. Our results suggest that those individuals with oral sex and sexual intercourse experience were more likely to engage in a wide range of online sexual activities than those having no experience with oral sex or sexual intercourse. The only exceptions here were in “Discussing with an unknown person about unknown’s sexual experience” and “Having sex on the Internet”, where the differences between experienced and inexperienced adolescents were not significant.

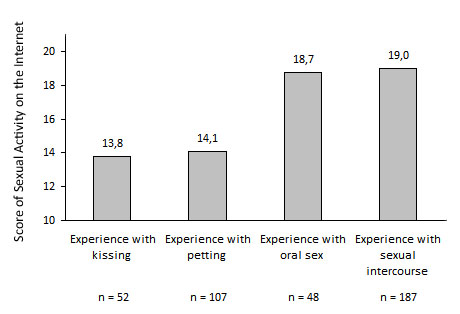

To analyse how the groups differed in Internet use, a scale of online sexual activities was developed. Through this the differences in internet use for sexual purposes compared to offline sexual experience was examined. Differences between sexual activities on Internet and sexual experiences in real life were confirmed, F(3,389) = 19.510, p < 0,001, r = 0.36. The Bonferroni post hoc test showed that the group “experienced with kissing” (M = 13.8, SD = 6.19) significantly differed from “experienced with oral sex” (M = 18,7, SD = 5,79), p < 0.001, and from “experienced with intercourse” (M = 19, SD = 7,41), p < 0,001. Similar findings were found for those “experienced with petting” (M = 14.08, SD = 4.13) and for “experienced with oral sex” (p < 0.001) and “experienced with intercourse” (p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between adolescents “experienced with kissing” and “experienced with petting”, as well as none between those “experienced with oral sex” and “experienced with intercourse” (see Figure 1). In conclusion, hypothesis H2 was rejected: Internet use for sexual purposes is similar for those who have only experienced off-line kissing and petting, it then suddenly increases, and is again similar at this higher rate for those who have experienced off-line oral sex and sexual intercourse, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Discussion

This research aimed to explore the relationship between online sexual activities and offline sexual experiences. A positive relationship was found between being sexually experienced offline and the range of use of the Internet for sexual purposes. Respectively, sexually experienced adolescents were more likely to use the Internet for sexual activities than sexually inexperienced ones.

Although the Internet allows access to a range of sexual content, establishing (romantic) contacts, or engaging in sexually-related discussion, this study’s findings suggest that sexually inexperienced 17 year olds are less likely to compensate for their lack of offline sexual experience through enhanced Internet use. The only exception was found in regards to the level of experience with petting; here less experienced adolescents looked for more information related to sex online. This might be explained as follows: certain skills are required to establish intimate contacts and to gain experience with some offline sexual practices (Brown et al., 1999) which may encourage individuals to engage in sex-related interactions on the Internet. This can mean that a non-interactive sexual behaviour on the Internet, such as looking for sexual information, is a suitable way for approaching sex among those who lack offline experience. While a greater openness to sex-related interaction on the Internet such as talking about sex, discussing sexual experience, exchanging erotic photos, and partly having virtual sex, is connected to a higher degree of offline sexual experience. However, further research is required to examine whether this openness towards sexual interaction enhances sexual activity in physical life, or whether it follows offline sexual experience, in the sense that adolescents use the Internet to reinforce their existing romantic relationships (Subrahmanyam & Greenfield, 2008).

The findings suggest that increased offline sexual experience is related to engaging in interactive activities such as discussing one’s sexual experiences, having virtual sex and exchanging erotic photos. However, it has been shown that the extent of the sexual activities performed online did not gradually develop with the acquisition of offline sexual experience. There was a notable difference in the use of the Internet for sexual purposes among adolescents who had kissed or petted and those who had practiced oral sex or sexual intercourse. Apart from accessing sexually relevant information, talking about sex and discussing one´s own sexual experience with a known person, the adolescents with kissing experience did not differ from those with no kissing experience. Further, young people who have petted did not differ in their internet use from their peers with no petting experience, with one exception relating to accessing information. The data suggests that the approach of corresponding the offline behaviour of adolescents to their behaviour on the Internet (Smahel, 2003) is not directly applicable in the area of sexuality. One possible explanation could be that both kissing and necking are considered by adolescents as less serious sexual experiences than oral sex or sexual intercourse, and thus they do not warrant being discussed online or stimulate broader internet use for sexual purposes. However, the findings may be viewed differently when taking into consideration the effects of the internet on adolescent´s sexuality. For example exposure to sexual content on the Internet may stimulate offline sexual activity (Brown & L´Engle, 2009). In relation to the present study, we may assume that internet use for sexual purposes to a small extent has a small effect on offline sexual behaviours.

The study suggests that the adolescents who had experienced oral sex and/or sexual intercourse were more likely to be “sexually” active on the Internet and engage in a wide range of measured online sexual activities. This result may be partly explained by a difference in adolescent’s perception of offline sexual activities. As prior research has shown, sexual practices with genitals such as oral sex and intercourse are very close in the sense that it is not clear whether oral sex precedes coitus or vice-versa. Some studies have shown that the first participation in oral sex by adolescents follows their first coitus (Weinberg et al., 1995), whereas others have found the opposite (Schwartz, 1999). However, in relation to the acquisition of sexual experiences both activities follow kissing or petting (including caressing the intimate parts of the body). This may imply that these sexual practices have a different meaning for adolescents than kissing and petting. Thus this closeness between oral sex and coitus is reflected in online sexual activity, those having experience with one of the aforementioned offline sexual practices using the Internet for similar sexual purposes, purposes which are different from those who do not report any experience with oral sex or intercourse.

There were several limitations to this study which must be considered when assessing its findings. Firstly, there was no official trend available on how adolescents acquire offline sexual experience; for example whether petting necessarily precedes sexual intercourse. Secondly, thanks to new media there are many sexual materials accessible to adolescents. These may affect the sexual scripts that they have adopted. Thirdly, the battery on online sexual activities did not include watching online pornography which represents a non-interactive behaviour. Neglecting this activity may raise questions about the aforementioned conclusion that the sexually inexperienced are less likely to compensate their lack of offline sexual experiences by enhanced Internet use for sexual purposes. Finally, the findings come from a cross-sectional study, which limits insight into the role of the Internet in emerging adolescent sexuality. It is not known if turning to the Internet for sexual purposes preceded the acquisition of sexual experiences offline, or vice versa. A longitudinal study could show clearly how the Internet becomes a part of the sexual lives of adolescents: how engaging in online sexual activities changes adolescents, and which of them is preferred by younger adolescents and older adolescents.

Conclusions

The study shows that those with sexual experience offline are more likely to use the Internet for sexual purposes than those who are not experienced at all. Although the Internet offers a wide range of possibilities for sexual interactions, less sexually experienced 17-year-olds do not seem to compensate for their lack of sexual experiences by using the Internet. Those that had experienced kissing or petting appeared to use the Internet for sexual purposes similarly; the rate and range of use then increased to a higher level which was similar for both those who had experienced oral sex or sexual intercourse. In conclusion, the relationship between the gradual extension of sexual experience offline and the gradual extension of using the Internet for sexual purposes is rather weak.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (MSM0021622406), the Czech Science Foundation (P407/11/0585) and the Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University.

References

Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 247–374.

Bauserman, R., & Davis C. (1996). Perceptions of early sexual experiences and adult sexual adjustment. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 8, 37–59.

Boies, S.C. (2002). University students´ uses of and reactions to online sexual information and entertainment: links to online and offline sexual behaviour. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 11(2), 77-89.

Braun-Courville, D.K., & Rojas, M. (2009). Exposure to sexually explicit web sites and adolescent sexual attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, 156–162.

Brown, B.B., Feiring, C., & Furman, W. (1999). Missing the love boat: why researchers have shied away from adolescent romance. In W. Furman, B.B. Brown, C. Feiring (Eds.), The development of romantic relationships in adolescence (pp. 1-16). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, D. J., & L’Engle, L. K. (2009). X-Rated: Sexual attitudes and behaviors associated with U.S. early adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit media. Communication Research, 36, 129-151.

Buzwell, S., & Rosenthal, D. (1996). Constructing a sexual self: Adolescent´s sexual self-perceptions and sexual risk taking. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 6, 489-513.

Collins, W. A., & Sroufe, L. A. (1999). Capacity for intimate relationships: A developmental construction. In W. Furman, B. B. Brown, C. Feiring (Eds.), The development of romantic relationships in adolescence (pp. 125-147). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cooper, A. (1998). Sexuality and the Internet: surfing its way into the new Millennium. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1 (2), 187-194.

Cooper, A., & Griffin-Shelley, E. (2002), The Internet: The new sexual revolution. In A. Cooper (Ed.), Sex and the internet: A guidebook for clinicians (pp. 1-15). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

DeLamater, J., & Friedrich, W. N. (2002). Human sexual development. Journal of Sex Research, 39, 10–14.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Osm věků člověka [Eight ages of man]. Praha: KÚP.

Flood, M. (2007). Exposure to pornography among youth in Australia. Journal Sociology, 43, 45-60

Furman, W., & Werner, E.A. (1997). Adolescent romantic relationships: a developmental perspective. New Directions for Child Development, 78, 21-36.

Graya, N.J., Klein, J.D., Noyce, P.R., Sesselberg, T.S., & Cantrill, J.A. (2005). Health information-seeking behaviour in adolescence: the place of the internet. Social Science & Medicine, 60, 1467–1478.

Gross, E.F. (2004). Adolescent Internet use: what we expect, what teens report. Applied Developmental Psychology, 25, 633-649.

Halpern, C. J. T., Udry, J. R., Suchindran, C., & Campbell, B. (2000). Adolescent males’ willingness to report masturbation. Journal of Sex Research, 37, 327–332.

Hopkins, K. W. (2000). Testing Reiss’s autonomy theory on changes in non-marital coital attitudes and behaviors of U.S. teenagers: 1960–1990. Scandinavian Journal of Sexology, 3, 113–125.

Huffaker, D. A., & Calvert, S. L. (2005). Gender, identity, and language use in teenage blogs. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10 (2). Retrieved from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10/issue2/huffaker.html

Larsson, I., & Svedin, C. G. (2002). Sexual experiences in childhood: Young adults’ recollections. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31, 263–273.

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K., with members of the EU Kids Online network (2010). Risks and safety on the internet. The perspective of European children. Full findings and policy implications from the EU Kids Online survey of 9-16 year olds and their parents in 25 countries.

Lo, V.-h., & Wei, R. (2005). Exposure to internet pornography and taiwanese adolescents' sexual attitudes and behavior. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 49, 221-237.

Lupač, P., & Sládek, J. (2008). The deepening of digital divide in the Czech Republic. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 1 (2). Retrieved from http://cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2008060203

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. (2006). Adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit material on the Internet. Communication Research, 33, 178-204.

Savin-Williams, R., & Diamond, L. (2004). Sex. In R. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 189–232). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Schwartz, I.M. (1999). Sexual activity prior to coital initiation: A comparison between males and females. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 28, 63–69.

Siibak, A. (2009). Constructing the self through the photo selection: Visual impression management on social networking websites. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 3(1). Retrieved from http://cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2009061501&article=1

Smahel, D. (2003). Souvislosti reálné a virtuální identity dospívajících [Connections between the real and virtual identity of adolescents]. In P. Mareš, T. Potočný (Eds.), Modernizace a česká rodina [Families, children, and youth in the age of transformation] (pp. 315-330). Brno: Barrister & Principal.

Smahel, D. (2006). Czech adolescents' partnership relations and sexuality in the Internet environment. Paper presented at the Society for Research on Adolescence Biennial Meeting. Retrieved from http://www.terapie.cz/materials/smahel-SRA-SF-2006.pdf

Smahel, D., & Subrahmanyam, K. (2007). „Any girls want to chat press 911“: partner selection in monitored and unmonitored teen chat rooms. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10 (3), 346-353.

Subrahmanyam, K. (2007). Adolescent Online Communication: Old Issues, New Intensities. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 1 (1). Retrieved from http://www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2007070701&article=%28search%20in%20Issues%29

Subrahmanyam, K., & Greenfield, P.M. (2008). Online communication and adolescent relationships. Future of Children, 18 (1), 119-146. Retrieved from http://futureofchildren.org/futureofchildren/publications/docs/18_01_06.pdf

Subrahmanyam, K., Greenfield, P.M., & Tynes, B. (2004). Constructing sexuality and identity in an online teen chat room. Applied developmental psychology, 25, 651-666.

Subrahmanyam, K. & Smahel, D. (2010). Digital youth: The role of media in development. Springer: New York.

Subrahmanyam, K., Smahel, D., & Greenfield, P. (2006). Connecting developmental constructions to the Internet: identity presentation and exploration in online teen chat rooms. Developmental psychology, 42, 395-406.

Suzuki, L.K., & Calzo, J.P. (2004). The search for peer advice in cyberspace: an examination of online teen bulletin boards about health and sexuality. Applied Developmental Psychology 25, 685-698.

Vybíral, Z., Smahel, D., & Divínová, R. (2004). Growing up in virtual reality – adolescents and the Internet. In P. Mareš (Ed.). Society, reproduction, and contemporary challenges (pp. 169-188). Brno: Barrister & Principal. Retrieved from http://www.terapie.cz/materials/czech-adolescents-internet.pdf

Weinberg, M. S., Lottes, I. L., & Shaver, F. M. (1995). Swedish or American heterosexual college youth: who is more permissive? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 24, 409–437.

Weinstein, E., & Rosen, E. (1991). The development of adolescent sexual intimacy: implications for counseling. Adolescence, 26, 331–340.

Weiss, P., & Zvěřina, J. (2001). Sexuální chování v ČR - situace a trendy [Sexual behavior in CZ - a situation and trends]. Praha: Portál.

Weiss, P., & Zvěřina, J. (2004). Sexuální chování v ČR: srovnání výzkumů z let 1993, 1998 a 2003 [Sexual behavior in CZ: a comparison of researches from 1993, 1998, 2003]. Retrieved from http://sex.systemic.cz/archive/cze/textbook2005/weiss2.pdf

Wolak, J., Mitchell, K.J., & Finkelhor, D. (2007). Unwanted and wanted exposure to online pornography in a national survey of youth internet users. Pediatrics, 119, 247-257.

Ybarra, M.L., & Mitchell, K.J. (2005). Exposure to Internet pornography among children and adolescents: A national survey. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 8, 473-486.

Correspondence to:

Anna Ševčíková

Faculty of Social Studies

Masaryk University

Jostova 10

60200 Brno

The Czech Republic

e-mail: asevciko(at)fss.muni.cz