The Rise of Fame: An Historical Content Analysis

Yalda T. Uhls1, Patricia M. Greenfield2Los Angeles, USA

Abstract

Keywords: tween, adolescence, TV, fame, content, media, values

Introduction

"In the future, everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes" (Andy Warhol, 1968). Over forty years after this famous quote, Andy Warhol’s prediction seems to have come to pass. Internet platforms such as online video-sharing sites, online publishing websites, and social networking sites allow nearly anyone to connect with a virtual audience of friends and strangers, giving everyone the potential for fame. Hollywood has always glamorized being rich, successful, and famous; however, in the past few years, a plethora of shows popular with tweens that feature extraordinarily successful teenage protagonists have been created (Martin, 2009). These shows then become part of supersystems (Kinder, 1991) that extend across multiple media, including web-based advertising, YouTube, online communities such as fan clubs, and video games (both online and offline). The present study aimed to document that this emphasis on fame in tween TV, all the more powerful because of its multimedia extensions, constituted a shift in values from earlier decades.

Promoted by the rapid growth of technology, supersystems surrounding popular TV characters are ubiquitous and global (Buckingham, 2007a). An example is the tween TV series, Hannah Montana, one of the shows analyzed in the present study. Hannah Montana, with a global audience of over 200 million, yielded 31,600,000 hits on Google and 727,000 videos on YouTube on January 31, 2011. It has also spawned a website, online fan club, and online video game site. Adding to its online presence, Miley Cyrus, the star of Hannah Montana, is at the center of online communities, notably fan clubs. Typing ''Miley Cyrus fan club'' into the Google search box yielded 1,370,000 results in a Google search on February 1, 2011.

Indeed, in the last few years, children surpassed adults as the number-one consumers of online video; YouTube.com, Disney.com and Nick.com are children's (age 2-11) top three online video destinations (Nielsen, 2008). Both Disney.com and Nick.com effectively act as marketing sites for the programming on their cable channels, with video, text, and game playing devoted to their products (disney.com, nick.com, 2011). YouTube, a consumer-driven video sharing site, can also serve to highlight popular TV characters and actors (e.g. inputting ''Miley Cyrus'' in YouTube search box returned 987,000 results on February 7, 2011). As such, in the current media-saturated environment, tweens are exposed to popular TV characters not only while watching TV programming, but potentially even more intensively and interactively while on the Internet. The Internet thus provides another all-encompassing platform to cultivate children's interest in television programming.

New communication tools, moreover, increase access to TV programming. The latest report by the Kaiser Family Foundation, which has measured media consumption every five years since 1999, found that, in 2009, youth spent nearly an hour a day watching TV content on platforms other than a traditional television set, including Internet, cell phones and Ipods. In a typical day, 59% watched live TV, while the remaining 41% accessed TV in a variety of different manners (Rideout, Foehr, & Roberts, 2010). Popular television programs are often available to watch online within a day of airing on websites such as Hulu and Netflix (http://hulu.com, http://netflix.com). TV shows are also available 24/7 on computers, digital recording devices, and mobile devices, allowing one to watch TV from nearly anywhere in the world where one can access the Internet (Uhls, Espinoza, Greenfield, Subrahmanyam, & Smahel, 2011). Because of this kind of proliferation, synergy, and cross-media convergence, TV content often saturates the media environment on a multitude of platforms.

Characters like Hannah Montana also reach beyond the United States. U.S.-based TV companies that create children's programming for their cable channels (i.e., Disney Channel, the home of Hannah Montana, and Nickelodeon), dominate the children's market in many countries, running more than thirty branded children's channels in Europe (Buckingham, 2007a). These US corporations work hard to reach audiences everywhere, as this quote from Bob Iger, CEO of Walt Disney, demonstrates: “reaching ‘dramatically and deeply,…’ has allowed Disney to, ‘...enter the hearts and minds of people all over the world” (Iger, 2007). Hence, the results of our historical content analysis may have international significance. Clearly, the online presence of these shows greatly magnifies their global presence.

Are successful teens portraying rich and famous lifestyles and values on television aimed at a young audience a new phenomenon? Has culture change in the United States expanded the importance of individualistic values on TV shows, notably fame and wealth, in recent years? Has it reduced the importance of communitarian values? To answer these questions, we examined the values of the most popular American television shows targeted to tweens every ten years for the last five decades.

The Theoretical Framework

Greenfield's Theory of Social Change and Human Development posits that, as learning environments move towards high technology, as living environments become increasingly urbanized, as education levels increase, and as people become wealthier, psychological development moves in the direction of increasing individualism, while traditional, familistic, and communitarian values decline (Greenfield, 2009a; Lerner, 1958; Manago & Greenfield, 2011). According to the theory, socio-demographic shifts drive changes in cultural values, which, in turn, alter the learning environment; a changed learning environment, in turn, transforms individual development (Greenfield, 2009a).

In the United States over the last five decades, the environment has, in fact, become more urban (U.S. Census, 1990; U.S. Census Bureau, 2000) while household income has risen (ClearPictureOnline.com, 2008) and the rate of university attendance has climbed steeply (Brock, 2010). Although technology has developed and spread over the last fifty years in the United States (Howe, 2010), the rise has been particularly sharp over the last decade. In this period, the use and availability of the Internet and digital media have substantially grown (Rideout et al., 2010; Uhls et al., 2011). As such, media technologies have become an ever more important part of the informal learning environment (Greenfield, 1984; Greenfield, 2009b).

Greenfield’s theory predicts that these sociodemographic shifts will produce ever more individualistic values, accompanied by a decline in communitarian values. A corollary is that these value shifts will be manifest in popular television shows that are a key component of the learning environment of tweens. Because fame and personal wealth are highly individualistic values, we expected an increase in their portrayal on popular TV over the decades, along with a decrease in the portrayal of communitarian values such as community feeling and tradition.

While a belief in individualism is as old as the American nation, the belief began to move from the political into the personal realm in the 1960s (Yankelovich, 1998). Most relevant to the present study, Putnam, observing American behavior in the decades since the sixties, documented the augmentation of individualistic values and the diminution of communitarian values (Putnam, 2000). We thus chose to examine shows over a period of 50 years, as this design allowed us to examine television programming over an extended period of social change (Baumeister, 1987; Lasch, 1991).

The existence of such change was reinforced by survey evidence of cultural shifts in behavior and values in recent decades in the United States. For example, a meta-analysis of 85 samples of U.S. university students over a period from 1979 to 2006 revealed that narcissistic personality traits increased 30% (Twenge, Konrath, Foster, Campbell, & Bushman, 2008). In the same period of time, U.S. students gained a greater desire for money (Dey, Astin, & Korn, 1991; Twenge, Campbell, Hoffman, & Lance, 2010). Conversely, a meta-analysis of 72 studies from 1977-2009 revealed that empathy levels dropped over 40% with the biggest drop after the year 2000 (Konrath, O’Brien, & Hsing, 2010). The valuing of tradition has also decreased across the generations (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010; Rozin, 2003). We expected these generational differences to be transmitted to tweens in the informal learning environments of popular TV programs aimed at this audience and omnipresent on the Internet.

Media Socialization During the Tween Years

A key developmental task during the tween years, age 9-11, is to form a belief system that integrates the many messages communicated via a variety of socializing agents including parents, school and media (Eder & Nenga, 2003; Harter, 1990). Social models provided by the entertainment environment of mass media convey a large amount of information about human values, styles of thinking, and behavior (Bandura, 2001). Characters on TV influence people in a wide variety of domains including work (Hoffner et al., 2006; Hoffner, Levine, & Toohey, 2008; Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, & Signorelli, 1979), moral values (Rosenkoetter, 2001) and family life (Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, & Signorelli, 1980; Comstock & Paik, 1991). Pertinent to the present study, university students in the U.S. identified more with TV characters perceived to have higher paying jobs and higher status than with characters who held less glamorous jobs (Hoffner et al., 2008). Accordingly, it is likely that tweens observing teenage characters with high status jobs that emphasize public recognition and material success will aspire to be like these social models.

Today, in the United States, young people spend more time using media than nearly any other activity except sleep (Brooks-Gunn & Donahue, 2008). The Kaiser study found that, in 2009, American youth, age 8 - 18, spent an average of nearly seven and one-half hours a day, seven days a week with media, defined as television, music, computer, video games, print, and movies. Tweens especially love media (Rideout et. al, 2010). Marketers and television programmers correspondingly focus their efforts on this demographic, creating content and products that “speak” directly to tweens (Buckingham, 2007b). Given the media-saturated environment that many tweens live in, it is likely this milieu has a large influence on the development of value priorities (Rohan, 2000). It is thus critical to understand what messages are being communicated through media during this important period of late childhood and early adolescence when media use is so high.

A New Method for Content Analysis

While numerous content analyses have examined violence, sexual content, and even physical affection in media (Ward, 1995; Wilson et al., 1998; Calliser & Robinson, 2010), to our knowledge an assessment of the depiction of aspirational values in TV content has not been conducted. Values, often embedded in overall themes or in choices that characters make, are diffuse, implicit, and require personal interpretation; they are therefore difficult to quantify through categorizing discrete behaviors. For example, it would be rare for a character in a television show to declare, “I value such and such” or “I aspire to this.” Content analysis methods traditionally interpret communication through categorization of molecular and discrete behaviors (Krippendorff, 2004). Testing a few coding schemes led to the conclusion that traditional content analysis would not work. Instead, we developed a new method that utilized a large sample of participants rather than a few researchers to assess the programs.

This method was also innovative in utilizing personality measures to assess content. We asked participants, recruited from online sites, to answer survey questions regarding how central, or important, certain values, drawn from a well-validated personality index (Kasser & Ryan, 1996a) were to textual descriptions of popular television shows for tweens. Our interest was in value priorities (i.e., the relative importance of each value in a list of aspirations) and how these priorities changed throughout five decades. We also utilized a list of desire-for-fame characteristics (Maltby et al., 2008) by asking participants if the main character in each show exhibited the characteristics. Again the interest was in how modeling a desire for fame in media content could have changed over the decades.

Hypotheses

Given our theoretical framework (Greenfield, 2009a), historical shifts in communication technologies, along with shifting sociodemographics, values, and behavior in the United States, led us to predict that fame, financial success, and other individualistic values would have become increasingly central in popular TV over the last fifty years, while communitarian values (e.g., community feeling, tradition) would diminish in importance over this same period of time. As a corollary to the predicted increase in the importance of fame, we also hypothesized that characters in the shows would manifest an increasing desire for fame over the decades, with the highpoint reached in 2007.

Method

Measures

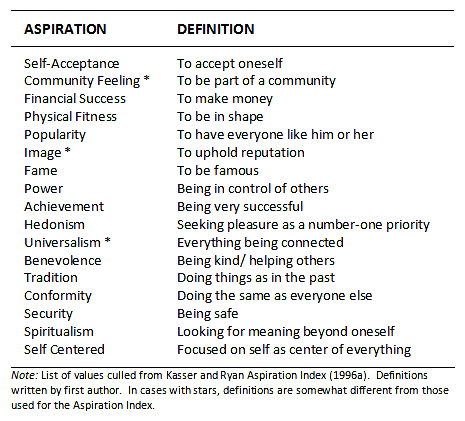

Values. The list of values was culled from a personality index developed to measure a participant's personal aspirations (Kasser & Ryan, 1996). This scale, validated with both adults and adolescents in over 17 countries, corresponds and builds upon Schwartz' list of value types (Schwartz & Bilsky, 1987). A total of 17 values were rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (Not at all important) to 4 (Extremely important) with an additional choice of ''Not applicable.'' Supplementary values not on the index were included, such as fame and achievement, in order to test the specific hypothesis in question. Each value also had a short description written by this study's first author. A full list of values, along with their description, is in Table 1.

Desire for Fame. To assess how much the main character in each show appeared to desire fame, we used a recently developed list of traits that individuals who desire to be famous are thought to exhibit (Maltby et al., 2008). The seven characteristics were ambition, glamour, meaning derived through comparison with others, psychological vulnerability, attention seeking, conceitedness, and social access. We added three additional qualities that we believed to be characteristic of those who desire fame: materialism, extraversion, and performing in front of others, making ten characteristics in all. The ten characteristics were rated on a 3-point scale: 1 Not at all present, 2 Somewhat present, and 3 Present. ''Not applicable'' was a fourth alternative.

Background Knowledge of Shows. After completing the evaluation of the shows, participants were asked how well they knew each of the tested TV shows. Participants had a choice of four answers: Don't Know Show, Watched Once, Familar, and Avid Fan. This show-specific background knowledge was considered a control variable; we wanted to make sure that differences among the decades in value ratings were not a function of differential show knowledge. From this measure, we could relate show knowledge to participant ratings, in hopes of ruling out program familiarity as a factor in the ratings.

Participants

A request was placed for survey participants on Craig's List, Facebook, and the Children's Digital Media Center@LA website for approximately six weeks. In this time period, a total of 60 adults living in the United States completed the questionnaires. Out of the forty two participants who provided their gender, twenty six were female. Of the twenty-one who provided information about their ethnicity, seventeen were European American while the remaining four were African American, Asian American, Native American, and Latino, with one from each ethnic group. Forty-one participants indicated their age and of these, the average age was 39, with a range of 18-59 years, with seven under 25, seven between 25-35, 13 between 36-45 and 14 over 45. Because of this age range, our sample included participants who grew up, and even were tweens, in most of the decades from which shows were drawn; hence, familiarity with the tested TV shows was not concentrated in a single decade, but distributed rather evenly over the decades being assessed.

Sampling Shows

For each of five decades, we selected the two most popular shows in a given year for the tween audience in the United States, as judged by Nielsen ratings. Popularity was considered a good index of cultural significance. Nielsen ratings were obtained for 1967, 1977, 1987, 1997, and 2007. Selecting two TV shows per decade for five decades yielded a total of ten shows. Table 2 lists the ten TV shows and the sources of the Neilsen ratings.

For the first two decades, ratings for popular shows were not broken down by age; but because, at this point in history, families usually owned only one television, the likelihood was that tweens watched the shows with their parents. For the last three decades, as televisions multiplied in households and audiences became more segmented (Xlane and The Economist, 2009), Nielsen ratings were available for the tween age group. The TV programs selected as stimuli (1) were the most popular ones with youth from 9 to 11 years of age (this was the age breakdown offered by Nielsen for the last three decades) and (2) aired for more than one season, in order to assess popular programming that represented more than a single year out of the decade sampled.

Construction of the Surveys

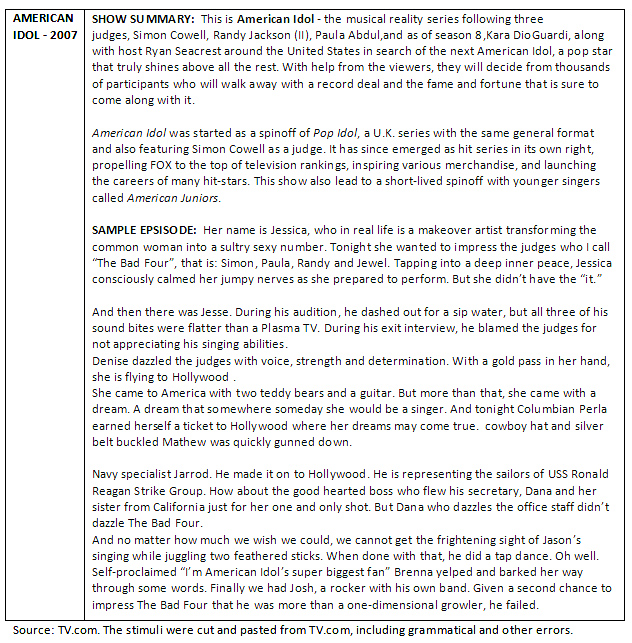

We located textual summaries on the website TV.com, the largest database we could find about TV programming, of every measured show over the fifty-year time period. Participants were provided two descriptions for each TV show: the first textual description, ranging from 125-300 words, described the show over its entire run of several seasons; the second textual description, ranging from 200-800 words, summarized one sample episode on one particular date. The episode chosen was the first with a full description (i.e. more than two sentences) in the year measured. The full show and episode descriptions are available on http://www.tv.com by searching for the show title. Unfortunately, space precludes presenting the full set of stimuli that were made available to our participants. However, Table 3 provides a sense of the stimuli by presenting the global show description and description of the episode selected for the study for one 2007 show, American Idol.

Textual descriptions of the TV series plus one episode from each show constituted the most ideal set of stimuli because this procedure eliminated the repetition that would have occurred had we asked a few research assistants to assess a whole season of shows. Such repetition would have made independent judgments of each episode improbable. By shortening the amount of time required to assess the shows, our method also allowed us to base assessments on 60 raters rather than just a few research assistants.

After pilot testing one survey with textual descriptions of all ten shows, we determined that the survey would take too long and that most participants would abandon the questionnaire before finishing. We therefore divided the survey in half, randomly drawing one show from each decade for Survey 1 and utilizing the remaining show from the same decade for Survey 2. The descriptions of the shows and their corresponding episodes, were placed in random order on each survey (i.e. not ordered according to time). Thus each survey was exactly the same except for the specific shows (see Table 2 for a list of shows in each survey). Because each survey utilized a different TV program from the same year, we felt that the same pattern of results replicated across the two surveys could provide greater generalizability of the findings than one survey alone.

Procedure

The recruitment statement posted online offered participants the chance to be entered into a drawing for five DVDs in exchange for taking the survey. Each participant was randomly offered one of the two surveys. After clicking on a link to the survey, the participants read an informed consent form; they indicated assent by continuing with the survey. They then were asked to read textual descriptions of the five shows, as well as one episode description per show, and to answer the questions with the information they were given. Given that we could not control whether a participant used prior knowledge of a particular show and that this knowledge could enrich understanding of a program's conveyed values, we told participants that they could draw on this knowledge, if available, to answer the questions. We later measured this knowledge in order to assess its impact on the ratings.

After reading the show and episode descriptions, participants were asked the same four questions about each of five shows, one from each decade; two questions were free-form text boxes and two were fill-in-the-bubble Likert scales. The first text box asked participants to write what they believed to be the main theme of the program; the next text box asked the same question about the specific episode described. These questions were intended to help the participant to think critically about the show. The next question asked participants to rate how important each of 17 values were to the show; if they did not feel that the value was relevant, they were given the option to answer "Not applicable." The last question asked them to consider the same show and episode descriptions to indicate how central each of a list of 10 personality characterics was for the main character or group of main characters. After answering these questions about each of the five shows, participants were asked how familiar they were with the ten measured TV shows. Finally, basic demographic data were collected. Participants were then thanked for their help and told to email the researcher if they wanted to be entered into the DVD drawing.

Analysis

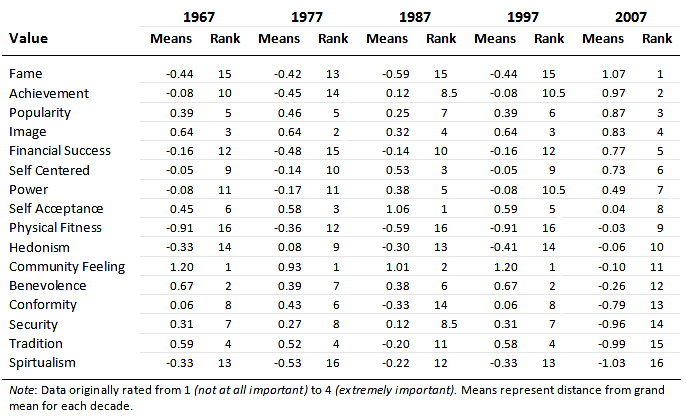

We combined data from the two surveys for each year in the five decades (i.e. two TV shows from 1967 represented 1967 and so on) and ranked the values in order of importance for each year. Given our interest in value priorities, that is, how important each value was compared to the other values on the list, we controlled for individuals' yearly grand means, by measuring the difference between each individual value rating and that individual's grand mean for the decade.

Unfortunately, due to a problem with the survey platform, participants' ratings for the importance of universalism in the 1967 show on Survey 2 were missing, so this variable was not used in the analyses. The relative mean importance for each of the remaining 16 values was then ranked from furthest above individuals' yearly grand mean to furthest below for each decade (i.e. how far above or below each value was relative to the participant's average for that year).

To test for significant differences between the decades, we ran a repeated-measures analysis of variance that treated decade as a five-level independent variable (i.e. each year represented a level) and survey (Survey 1 or 2) as a between-subjects variable. Participants’ absolute rating of importance for each value under consideration was the dependent variable. If the participant answered ''Not applicable,'' this answer was treated as missing data and left out of the analysis. In cases where we found a significant interaction between survey and decade, we ran a separate ANOVA for each survey.

For the characteristics indicating a character or characters' desire for fame, as with the values, we carried out a repeated-measures analysis of variance, treating decade as a five-level independent variable and survey (Survey 1 and 2) as a between-subjects variable. The dependent variables were the seven characteristics identified by Maltby et al. to measure a person's implicit desire to be famous and the three variables we added: materialism, extraversion, and performing in front of others; a separate analysis was carried out for each characteristic. The response “Not applicable” was treated as missing data. In cases where the interaction between survey and characteristic was statistically significant, we also examined the main effect of decade for Survey 1 and 2 separately, as we did for the value analysis. If the main effect of decade was significant for each individual survey, we concluded that the effect of decade was robust and not affected by which survey the participant took.

Results

Value Change in Popular Tween Television from 1967 to 2007

As predicted, fame, financial success, and other individualistic values, notably achievement, rose in importance across the decades. Fame, the main focus of the study, made the most dramatic shift. Table 4 shows that fame rose from the bottom of the value rankings in 1967 (number 15 out of 16) to the top value in 2007. Financial success also rose in importance, as predicted; it was ranked 12th in 1967, rising to fifth in 2007. Two other individualisitic values showed a major increase in relative importance: Achievement rose from tenth place to second place across the decades, while physical fitness moved from sixteenth place to ninth place. In contrast, communitarian values, as predicted, declined in relative importance over time. Three communitarian values – community feeling, tradition, and benevolence – showed sharp declines in relative importance from 1967 to 2007 (Table 4). Community feeling started out as the top-ranked value in 1967 and fell to number 11. Tradition was ranked fourth in 1967 and fell to 15th place in 2007. Benevolence went from second place to 12th place across the decades. Of all the values assessed, these three showed the largest decline in relative importance from 1967 to 2007.

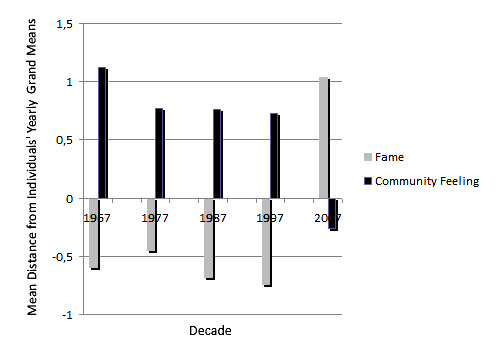

Figure 1 provides a graphic example of this pattern. It shows how community feeling, the value that was top in 1967, and fame, the value that was top in 2007, flip in 2007, with fame for the first time above the yearly grand mean and community feeling below.

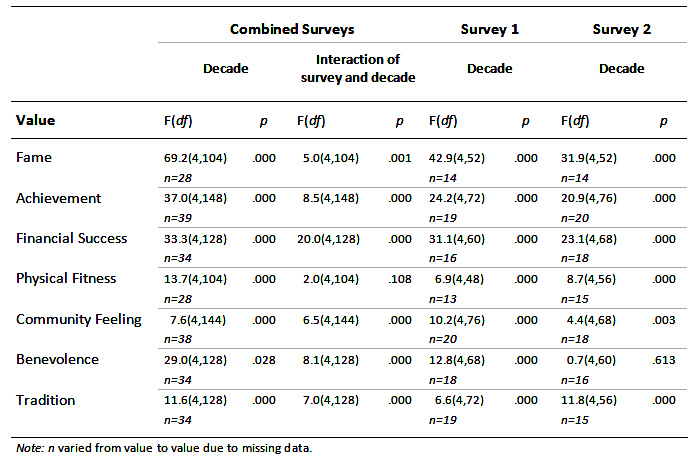

In order to assess the statistical significance of the historical change in the relative importance of values, we carried out repeated measures analyses of variance. Here the dependent variable switched from relative rankings to absolute ratings in order to have scores that could be compared across time. The increasing relative importance of the individualistic values of fame, financial success, achievement, and physical fitness shown in Table 4 was confirmed by statistically significant changes over time revealed in the repeated-measures ANOVAs (Table 5). Similarly, the declining importance of the communitarian values of community feeling and tradition shown in Table 4 was confirmed by statistically significant changes over time revealed in the repeated-measures ANOVAs (Table 5). These six variables showed significant change over time not only as a main effect (both survey forms together) but also for each survey individually, even when there was a significant interaction of survey and decade. Benevolence showed significant overall decline over the decades, but there was a significant interaction between survey and decade, and the change was statistically significant only for Survey 1.

Historical Change in Main Characters' Desire for Fame in Tween Television from 1967 to 2007

Historical change in the seven traits from Maltby et al.’s (2008) desire-for-fame list (ambition, comparison to others, attention seeking, conceitedness, social access, psychological vulnerability, and glamour), as well as our three added dimensions (materialism, extraversion, and performing in front of others) was assessed across the five decades. Participants answered if the quality was present, somewhat present, or not at all present, in the main character or group of characters, with an option for “not applicable.” Confirming our hypothesis, participants rated each component of desire for fame most present in 2007 (Table 6).

Repeated-measures analyses of variance showed that, for nine of the ten personality traits, the change was statistically significant across the decades, in both the combined surveys and each survey individually (Table 7). In accord with our hypothesis, desire for fame was considered most present in the main character or group of main characters in the 2007 shows than in shows of earlier decades.

Control Analyses: Age and Show Knowledge

To see whether differential show knowledge on the part of different cohorts might have accounted for the results, we first correlated age and show knowledge for each decade. (Show knowledge in this analysis was an average of the two shows rated in each decade.) There was a significant correlation between age and show knowledge for every decade except the most recent, a decade in which every age group could potentially have equal access to the shows. For the older shows (1967 and 1977), the correlation was positive (1967: r = .595, p < .001; 1977: r = .451, p = .003, two-tailed tests), indicating that older participants had greater knowledge of the shows from the two earliest decades. For the newer shows (1987 and 1997), the correlation was negative (1987: r = -.333, p = .033; 1997: r = -.398, p = .010), indicating that younger participants had greater knowledge of the shows from later decades.

Because age affected show knowledge, which might, in turn, affect value ratings, we correlated age with ratings of all of the values in every decade that had shown significant changes over the decades: fame, financial success, achievement, physical fitness, community feeling, and tradition. There were a only a few significant correlations: fame ratings were negatively correlated with age in 1977 (r = -.351, p = .031) and 1987 (r = -.346, p =.039), indicating that younger participants gave higher ratings to the fame value in these two measured years. Achievement ratings were negatively correlated with age in 1967 (r = -.377, p = .015), indicating that younger participants gave higher ratings to the achievement value for this decade. Similarly, ratings of physical activity were negatively correlated with age in 1967 (r = -.501, p =. 002), indicating that younger participants gave higher ratings to physical activity. In order to be conservative, we then used age as a covariate in the analyses of these three values, fame, achievement, and physical activity, and reran the repeated measures analyses of variance with age as a covariate. The historical rise in the presence of fame, achievement, and physical activity, shown in the repeated measures analyses reported above and also in Table 5, remained significant, and there were no significant interactions with age in the repeated measures analyses of covariance for ratings of these values.

We also took another approach to considering whether historical differences in show knowledge could be driving the historical changes in program values our participants identified in tween television. The pattern over the decades for show knowledge is presented in Figure 2. This pattern differs from the historical pattern for either the individualistic or the communitarian values portrayed on popular TV shows. Compared with other decades, 2007 is in the middle of the range for show knowledge (i.e. greater knowledge of the 1967 and 1977 shows than of the 2007 shows; less knowledge of the 1987 and 1997 shows than of the 2007 shows). In contrast, the 2007 shows are at the extremes of the historical distributions for the variables of interest: individualistic values have their greatest importance in 2007, while communitarian values have their lowest importance. These discrepant distributions of show knowledge and the variables of interest provide additional evidence that the findings concerning value change over the decades cannot be attributed to differential show knowledge.

Discussion

Historical Change in Portrayed Values and in Sensitivity to those Values

The results confirmed our hypotheses. Fame became more important in tween television over time, going from number 15 out of 16 in almost every other decade to first in 2007. There was also evidence in the correlations of fame ratings with age that younger cohorts were more attuned to the value of fame in a given situation than older ones: for the 1977 and 1987 shows, younger participants rated fame as a more important value than did older participants. This is an example of what Kitayama, Markus, and colleagues (1997) conceptualize as the mutual constitution of culture and psychological processes. That is, the newest television shows are cultural products that embody and portray the value of fame; and, at the same time, the interpretive processes of younger participants, exposed to this type of cultural product at more impressionable ages, project the value of fame on older television shows more so than do older participants, who have not been exposed to cultural situations emphasizing fame so early in life. The same kind of analysis is applicable to the two other individualistic values, achievement and physical activity, in which there is not only an historical rise over time in their cultural importance, but also a significant tendency for younger cohorts to be more attuned to these values. Thus not only do the values embodied in television shows change over the decades, but also the people watching them evolve in consonant directions.

Community feeling was ranked as one of the most important values in popular TV shows for every decade except 2007, when it was ranked eleventh out of 16. This reversal in the importance of the two values paints a picture of fairly dramatic change in 2007 in value priorities as depicted in Figure 1. As predicted, financial success showed the same pattern as fame, although the increase in 2007 was not as sharp. Similarly, other communitarian values - benevolence and tradition - showed the same pattern as community feeling, with a sharp drop in importance between 1967 and 2007.

Overall, the pattern of results provides new empirical support for Greenfield’s (2009a) Theory of Social Change and Human Development. The theoretically based prediction was that the importance of fame, wealth, and other individualistic values in tween television in the United States would rise as the society became richer, more urbanized, more educated, and more technological; however, the rise did not follow the gradual rising pattern of the first three of these sociodemographic variables in these decades. Nor did the predicted decline in communitarian values show a gradual decline through the decades. Instead, there was stability in the relative importance of these values between 1967 and 1997, followed by sudden shifts in the decade between 1997 and 2007. These shifts were correlated with the explosion of communication technologies from the late 1990s into the new millenium. This temporal correlation gives rise to the possibility that technology was the most important cause of these changes in value priorities.

What is the evidence for the explosion of technology during this time period? From 1999 to 2009, children’s access to home Internet doubled to a penetration of 84%, as did access to high-speed Internet. Ownership of digital devices also grew rapidly, with ownership of an Ipod or other MP3 player increasing fourfold to 76% (Rideout et al., 2010). These changes are not isolated to the United States: home access to the Internet was recently reported in the European Union for 85% of children, age 9-16 (EU Kids Online, 2010). Internet access and ownership of digital devices were not the only changes in the learning environment due to technological advances. New, rapidly growing applications such as YouTube, MySpace and Facebook were created within the last decade (Uhls et al, 2011; Xlane and The Economist, 2009). These sites grew rapidly; two billion videos a day are watched on YouTube around the world, and Facebook currently has 500 million users (Uhls et al., 2011). On these kinds of website, one can broadcast oneself to an invisible audience - totally anonymously on YouTube; and filled with “friends,” many of whom are but casual acquaintances, on Facebook. Indeed, social networking sites give emerging adults the potential for and, often, subsequent aspirations for a larger audience (Xlane and The Economist, 2009; Manago, Graham, Greenfield, & Salimkhan, 2008). An ethnographic study of youth practices with new media found that today’s youth are quite familiar with the concept of the YouTube celebrity, and discourses of fame exist around new media technologies (Ito et al., 2009), while a recent focus-group study with tweens found that fame had become the number-one aspirational value, in comparison to others studied in the present research (Uhls & Greenfield, under revision).

The Trend Continues

The trend we identify in the present quantitative study has continued with more recent television programs aimed at this same age group: in Big Time Rush, which debuted in 2009, a group of Minnesota teens are discovered and then become the latest chart-topping boy band; in True Jackson, which debuted in 2008, a fifteen year old girl is the vice president of a fashion company, replete with office, assistant and expense acount. In addition to True Jackson, six other of the top ten television shows for age 9-14 in 2009 feature teenage characters with successful careers in different arenas such as television, music, and fashion (about.com, 2011). In 2009, an article in the Los Angeles Times suggested that the majority of fictional programming targeted to tweens focuses on the lure of achieving celebrity at a young age (Martin, 2009). It is worthwhile to note that all of these shows have aired since the data were collected for this study. In an even more recent example, a recently announced American reality TV show, hosted by the former American Idol judge Simon Cowell, will offer contestants as young as 12 the chance to compete for a $5 million dollar recording contract (Kaufman, 2011).

Moreover, the success of these adolescent characters includes other arenas such as the Internet. For example, one of the most popular current shows is iCarly, about a teenage girl who lives alone with her older brother and who runs a very popular web show with her best friend. Nor is this kind of content restricted to television. Indeed, iCarly is in part a tween reality show, featuring an online podcast talent show to which the audience can submit their own segments. In addition, with popular video games such as Guitar Hero, where one’s avatar is a rock star, or online sites such as Stardoll.com, where the site states what it is about under its logo – “fame, fashion and friends”, content developers are providing tools with these types of message embedded in the design. Television content providers may believe that they are merely reflecting the day-to-day values and desires of children as this quote by Dan Schneider, creator of the popular tween shows iCarly and Victorious, indicates: “If there is anything I've learned about kids today -- and I'm not saying this is good or bad -- it's that they all want to be stars" (Martin, 2009). Yet, like the debate over nature and nurture, the likelihood is that TV content and cultural values interact and affect each other. In either case, media content providers must be cognizant of the messages they are sending young people, and research must continue to describe objectively what the content portrays.

Limitations of Current Study

This study examined only one year in each decade. In order to be certain that the results truly represent each decade, it would be ideal to test more shows per decade, spread out over several years. Given that it was already difficult to have participants answer questions about just five shows without abandoning the survey, it may be difficult to achieve reliable results without participant fatigue. However, note that the two shows most popular in 2007 were still popular in 2009. It is entirely possible that the popularity of shows representing the other decades also had longevity beyond the two years required for inclusion in the survey.

Future Directions

Given that values for fame are indeed prevalent in popular TV and furthermore that a lifestyle of enormous success, wealth, and renown is depicted as normative for adolescent characters, research must explore how this could affect development. Therefore, our future research will examine the developmental implications of this focus on fame and other extrinsic aspirations in this important learning environment. It is one thing to know that the content has changed, but until one measures the target audience and begins to examine how they interpret the messages in these programs, it will be difficult to know if and how youth values are affected. A full program of research, using methods such as qualitative focus groups, correlational surveys, and experimental manipulations, would be ideal fully to explore the mechanisms involved. We have begun on this path with a focus-group study of tweens (Uhls & Greenfield, under revision) This study also expands the consideration of fame-oriented media practices to YouTube, perhaps the most important media tool promoting the value of fame to children and tweens.

Once designed, the method created for this content analysis was relatively easy to administer and could take advantage of the relatively easy recruitment of undergraduate participants. This method could be used for a number of other content analyses examining many different thematic arenas portrayed in media. For example, how is academic learning portrayed in popular shows? If research found that school was portrayed as boring, or exciting only for children who were not popular, this portrayal might have a negative influence on academic motivation for many children.

Implications

The changes in multimedia content and the possibilities for the interactive construction of fame on YouTube may have a measurable impact on the goals and desires of emerging adults. Reynolds et al. (2006) tracked changes in high school students’ educational and occupational plans over twenty-five years and found that in the later decades, senior students’ ambitions outpaced what they were likely to achieve (Reynolds, Stewart, MacDonald, & Sischo, 2006); fame may be one of those ambitions. In so far as fame in and of itself is an unrealistic ambition disconnected from academic achievement, it could undermine motivation to succeed in school and thus result in dissatisfaction later in life (Buckingham, 2007a; Kirst & Venezia, 2004). Moreover, aspirations for material wealth and fame have been found to correlate with lower well-being (Kasser, Ryan, Couchman, & Sheldon, 2004; Kasser & Ryan, 1993; Kasser & Ryan, 1996b). Future research can subject these implications to empirical test.

Children during the preadolescent and adolescent years are wrestling with moral and identity development (Hart & Gustavo, 2005; Massey, Gebhardt, & Garnefski, 2008). Media, ever prevalent in the lives of today’s youth, are an important source of information for their developing concepts of what the social world outside their immediate environment is all about. However, early adolescents are not watching characters in everyday environments; instead they are watching and likely identifying with youth who have enormously successful careers to the point of becoming famous. If tweens observe characters they admire succeeding and achieving wide public recognition and material success with little effort or training, they are likely to believe that this success is entirely possible and easy to achieve. This is an important issue for future research.

Author Note

We would like to thank Kaveri Subrahmanyam and Adriana Manago, the ATS consulting group at UCLA, and the CDMC@LA group for their support and feedback. We want to express our appreciation to Montgomery Bissell, Kristen Gillespie-Lynch, Jaana Juvonen, and Tim Kasser for their extremely helpful notes and to Goldie Salmikhan for her help with table design and execution. Many thanks to the Greenfield lab group and our research assistants, Mark Anthony Sy and Darrab Zarrabi. This research was aided by a UCLA first-year and summer fellowship and a grant from the American Association of University Women awarded to the first author.

References

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology, 3, 265-299.

Baumeister, R. F. (1987). How the self became a problem: A psychological review of historical research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 163-176.

Brock, T. (2010). Young adults and higher education: Barriers and breakthroughs to success. Future of Children, 20, 109-132.

Brooks-Gunn, J. B., & Donahue, E. H. (2008). Children and electronic media: Introducing the issue. The Future of Children, 18 (1), 3-10.

Buckingham, D. (2007a). Childhood in the age of global media. Children’s Geographies, 5, 43-54.

Buckingham, D. (2007b). Selling childhood. Journal of Children and Media, 1, 15-24.

Calliser, M. A., & Robinson, T. (2010). Content analysis of physical affection within television families during the 2006-2007 season of U.S. children’s programming. Journal of Children and Media, 4, 155-173.

ClearPictureOnline.com. (2008). Retrieved from http://www.clearpictureonline.com/1960-Food-College-Income.html

Comstock, G., & Paik, H. (1991). Television and the American child. New York: Academic Press.

Dey, E. L., Astin, E. W., & Korn, W. S. (1991). American freshman: 40 year norms. The American Freshman. HERI: UCLA.

Eder, D., & Nenga, S. K. (2003). Socialization in adolescence. In J. Delamater (Ed.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 157-175). New York: Kluwer Academic/ Plenum Publishers.

EU Kids Online. (2010). Risks and safety on the Internet. EU Kids Online. Retrieved from http://www2.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/EUKidsOnline/EU%20Kids%20Online%20reports.aspx

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1979). Living with television: The dynamics of the cultivation process. Perspectives on media effects (pp. 17-40). Hilldale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorelli, N. (1980). Media and the family: Images and Impact. Paper presented at the Research Forum on Family Issues, Washington DC.

Greenfield, P. M. (1984). Mind & media: The effects of television, video games & computers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Greenfield, P. M. (2009a). Linking social change and developmental change: Shifting pathways of human development. Developmental Psychology, 45, 401-418.

Greenfield, P. M. (2009b). Technology and informal education: What is taught, what is learned. Science, 323, 69-71.

Hart, D., & Gustavo, C. (2005). Moral development in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15, 223-233.

Harter, S. (1990). Developmental differences in the nature of self representations: Implications for the understanding, assessment, and treatment of maladaptive behavior. Cognitive Theory and Research, 14, 113-142.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61-135.

Hoffner, C. A., Levine, K. J., Sullivan, Q. E., Crowell, D., Pedrick, L., & Berndt, P. (2006). TV characters at work: Television’s role in the occupational aspirations of economically disadvantaged youth. Journal of Career Development, 33, 3-18.

Hoffner, C. A., Levine, K. J., & Toohey, R. A. (2008). Socialization to work in late adolescnce: The role of television and family. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 52, 282-301.

Howe, W. (2010). A brief history of the Internet. Retrieved from http://www.walthowe.com/navnet/history.html

Iger, B. (2007). Luncheon with Pacific Council, Burbank, CA.

Ito, M., Baumer, S., Bittanti, M., boyd, d., Cody, R., Herr-Stephenson, B., & Tripp, L. (2009). Hanging out, messing around, and geeking out: Kids living and learning with new media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 410-422.

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996a). Aspiration Index. Retrieved from http://faculty.knox.edu/tkasser/aspirations.html

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996b). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 280-287.

Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Sheldon, K. M. (2004). Materialistic values: Their causes and consequences. In T. Kasser & A. D. Kanner (Eds.), Psychology and consumer culture: The struggle for a good life in a materialistic world (pp. 11-28). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kaufman, G. (2011). Simon Cowell’s X factor offers life-changing $5M prize. Retrieved from http://www.mtv.com/news/articles/1657461/simon-cowell-x-factor.jhtml

Kinder, M. (1991). Playing with power in movies, television, and video games: From muppet babies to teenage mutant ninja turtles. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Kirst, M. W., & Venezia, A. (Eds.). (2004). From high school to college: Improving opportunities for success in postsecondary education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Kitayama, S., Markus, H. R., Hatsumo, H., & Norasakkunkit, V. (1997). Individual and collective processes in the construction of the self: Self-enhancement in the United States and self-criticism in Japan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1245-1267.

Konrath, S. H., O’Brien, E. H., & Hsing, C. (2010). Changes in dispositional empathy in American college students over time: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 180-198.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Lasch, C. (1991). The culture of narcissism: American life in an age of diminishing expectations. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Lerner, D. (1958). The passing of traditional society: Modernizing in the Middle East. New York: Free Press.

Maltby, J., Day, L., Giles, D., Gillett, R., Quick, M., Langcaster-James, H., & Linley, A. P. (2008). Implicit theories of a desire for fame. British Journal of Psychology, 99, 279-292.

Manago, A., & Greenfield, P. M. (2011). The construction of independent values among Maya women at the forefront of social change: Four case studies. Ethos, 39, 1-29.

Manago, A. M., Graham, M. B., Greenfield, P. M., & Salimkhan, G. (2008). Self-presentation and gender on MySpace. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29, 446-458.

Martin, D. (2009, November 22). Child’s Play. Los Angeles Times.

Massey, E. K., Gebhardt, W. A., & Garnefski, N. (2008). Adolescent goal content and pursuit: A review of the literature for the past 16 years. Developmental Review, 28, 421-460.

Nielsen Online. (2008). The video generation: Kids and teens consume more video content than adults at home (News release).

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Reynolds, J., Stewart, M., MacDonald, R., & Sischo, L. (2006). Have adolescents become too ambitious? High school seniors’ educational and occupational plans, 1976 to 2000. Social Problems, 53, 186-206.

Rideout, V. J., Foehr, U. G., & Roberts, D. F. (2010). Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8-18 year-olds. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Rohan, M. (2000). A rose by any name? The values construct. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4, 255-277.

Rosenkoetter, L. I. (2001). Television and Morality. In D. G. Singer & J. L. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 463-473). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Rozin, P. (2003). Five potential principles for understanding cultural differences in relation to individual differences. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 273-283.

Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1987). Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 550-562.

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, S. M., Hoffman, B. J., & Lance, C. E. (2010). Generational differences in work values: Leisure and extrinsic values increasing, social and intrinsic values decreasing. Journal of Management, 1-26. doi:10.1177/0149206309352246

Twenge, J. M., Konrath, S., Foster, J. D., Campbell, W. K., & Bushman, B. (2008). Egos inflating over time: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of the narcissistic personaity inventory. Journal Of Personality, 76, 875-903.

U.S. Census. (1990). Population 1790 to 1990. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/www/censusdata/files/table-4.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2000). Geographic comparison table. Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/GCTTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-_box_head_nbr=GCT-P1&-ds_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U&-format=US-1

Wilson, B. J., Kunkel, D., Linz, D., Potterm, J., Donnerstein, E., Smith, S. L., Blumenthal, E., et al. (1998). Violence in television programming overall: University of California study. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Uhls, Y. T., & Greenfield, P. M. (Under revision). The value of fame: Preadolescent perceptions of popular media and their relationship to future aspirations.

Uhls, Y. T., Espinoza, G., Greenfield, P. M., Subrahmanyam, K., & Smahel, D. (2011). Internet and other interactive media. In B. A. Brown & M. Prinstein (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Adolescence. Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

Ward, L. M. (1995). Talking about sex: Common themes about sexuality in the prime-time television programs that children and adolescents view most. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24, 595-615.

Xlane and The Economist. (2009). Did you know: Best of shift happens. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hyZRS0BnpAI

Yankelovich, Y. (1998). How American individualism is evolving. The Public Perspective, 1. Retrieved from http://danyankelovich.com/howamerican.pdf

Correspondence to:

Yalda T. Uhls

Email: yaldatuhls(at)gmail.com