Social and Psychological Correlates of Internet Use among College Students

Nancy Shields1 , Jeremy Kane2

Abstract

Keywords: Internet use, college students, depression, challenge hypothesis, rich-get-richer

Introduction

The advent of the widespread use of the Internet in the 1990s was met with both fear and enthusiasm regarding the potential impact on social relationships and psychological well-being (Bargh & McKenna, 2004). However, a relatively early study by Kraut and associates (Kraut et al., 1998) seemed to set the tone for much of the research that would follow. They found that use of the Internet appeared to increase loneliness, depression, and stress among a sample of 169 adults. They called this the “Internet Paradox” in that a technology that theoretically would increase communication could instead have negative social and psychological effects. Even though the results actually reversed in a follow-up study published several years later (Kraut et al. 2002), the original study inspired a significant amount of research designed to assess potential negative effects of Internet use. Young and Rogers’ (1998) study was also influential in generating interest in the relationship between Internet “addiction” and depression.

Accordingly, studies on Internet addiction have proliferated (Byun et al. 2009; Chou, Condron, & Belland, 2005). Surprisingly, relatively few of the studies have focused on college students, even though college students have been found to have both high levels of Internet use (Kandell, 1998; Pew Internet and American Life, 2002) as well as depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2009; Peterson, 2002; Voelker, 2003). The studies on college students differ in terms of whether they measure Internet addiction or simply Internet use, and the specific social and psychological variables they investigate. The results are mixed – some studies find negative relationships (e.g., Morahan-Martin & Schumaker, 2000; Morahan-Martin & Schumaker, 2003), some positive relationships (e.g., Morgan & Cotton, 2003), and others no relationships (e.g., Anderson, 2001).

Relatively recent studies focusing on Internet addiction among college students have tended to find primarily negative correlates. Morahan-Martin and Schumaker (2000) investigated the relationship between pathological Internet use (PIU) and loneliness among 277 undergraduate students. They found that loneliness was associated with pathological use. In a later reanalysis of the same data (Morahan-Martin & Schumaker, 2003), they found that lonely users were more likely than the non-lonely to seek emotional support online, find more satisfaction with online versus offline friends, and to be experiencing more disturbances in their daily lives. Also using the PUI scale, Niemz, Griffins and Banyard (2005) studied 371 British college students and found that pathological users reported more perceived academic, social and interpersonal problems as well as lower self-esteem. However, there was not a difference between pathological and non-pathological users on the General Heath Questionnaire, a measure of anxiety, depression and self-confidence. Chak and Leung’s (2004) study included 722 Internet users between the ages of 12 and 26, some of which were college students. They found that Internet addiction was associated with shyness, external locus of control, and a belief in the effect of chance on outcomes. Fortson, Scotti, Chen, Malone and Del Ben (2007) found that abuse of and dependence on the on the Internet was associated with depression and lower levels of face-to-face interaction among 411 undergraduates. However, depression was not related to amount of time online.

Two additional studies on Internet addiction involved college students in Taiwan. Chou and Hsiao (2000) studied the relationships between Internet addiction and perceived impact on academics, daily life routine, and relationships with friends, family and teachers among 171 college students. Addiction was only related to perceived impact on studies and daily routines. In a more recent study of 216 Taiwanese college students, Ko, Yen, Chen, Chen, and Yen (2008) found that major depression was related to addiction, but only for men.

Many of these studies investigate relationships that are relevant to a current debate in the research on Internet use concerning whether Internet use functions to extend the social networks of individuals who already have very active social lives (extraverts), or if it is used by individuals with low levels of social contact offline to compensate for a lack of “real life” social interaction. These two models have been described as “The Rich Get Richer Approach” and the “Social Compensation Approach,” respectively (Stamoulis & Farley, 2010). Although Stamoulis and Farley (2010) recognize that results from past studies concerning these two models have been inconsistent (Livingstone, & Helsper, 2007; Peter, Valkenburg, & Schouten, 2005; Sheldon, 2008), they found strong support for the social compensation approach. They found that low involvement in extracurricular activities and lower levels of face-to-face interaction was related to more risk-taking behaviors on the Internet among a sample of adolescents. The studies by Morahan-Martin (2000, 2003), Niemz et al. (2005), Chak and Leung (2004), and Fortson et al. (2007) are also consistent with the social compensation model. However, studies by Sheldon (2008), Park (2010), and Peter et al. (2005) support the “Rich get Richer” model. Park (2010) found that wireless Internet use among college students was positively correlated with face-to-face interaction with friends and acquaintances, and Sheldon (2008) found that college students who were more willing to communicate offline had more online friendships. Peter et al. (2005) also found that extraverted adolescents self-disclosed more and spent more time communicating online.

Several studies have examined the association between time on the Internet and social and psychological factors, and these studies seem less likely to find negative associations. Morgan and Cotton’s (2003) study of college freshmen found that increased time spent shopping, playing games and doing research was associated with higher levels of depression, but sending e-mail and visiting chat rooms was associated with lower levels. Using path analysis, LaRose, Eastin and Gregg (2001) found that higher Internet use was only indirectly associated with depression and the relationship was mediated by Internet self-efficacy and anticipated Internet stress among 171 college students. They also found that higher use of e-mail to communicate with known others was related to fewer symptoms of depression. Anderson (2001) studied the relationships between Internet use and perceived effects on academics, extracurricular activities, sleep patterns and real-life relationships among a large sample (1,300) of college students. Only sleep patterns were associated with Internet use. Finally, Gordon, Juang and Syed (2007) studied depression, social anxiety, and family cohesion and Internet use for particular purposes among 312 college students. Only Internet use for coping purposes was associated with depression, social anxiety and family cohesion.

A limitation of almost all of these studies is that the extent to which the samples represent particular student populations is unknown. Some samples were generated by administration of questionnaires to college classes (Anderson, 2001; Chou & Hsiao, 2000; Gordon et al., 2007; LaRose et al., 2001; Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2000, 2003), yet none of the studies reported an estimated response rate or an analysis of the extent to which the sample was representative of the student population. Other studies have used self-selected samples (Ko et al., 2008), subject pools (Fortson et al., 2007) or Internet snowballing (Chak & Leung, 2004; Niemz et al., 2005). Samples that are self-selected or employ snowballing may be especially at risk of over-representing heavy Internet users. Byun et al. (2009) also note similar sampling problems with Internet addiction studies.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of our study was to investigate several questions that have been raised by the research on Internet use and addiction among college students. First, we sought to investigate the extent of Internet use (and types of use) and examine the relationship between Internet use and a variety of social and psychological variables such as depression, extent of face-to-face interaction, and stress related to interpersonal relationships among a sample of college students. Because of the mixed findings in the literature, we expected both positive and negative associations with Internet use. In terms of positive associations, we expected Internet use for the purpose of connecting with others, e.g., e-mail, (LaRose et al., 2001; Morgan & Cotton, 2003) to be related to fewer symptoms of depression and interpersonal problems.

We also investigate the relationship between Internet use (for work, school, and personal use) and academic performance. Although several studies have found a negative association between Internet use or addiction and perceived impact on academics (Anderson, 2001; Chou & Hsiao, 2000; Kubey, Lavin & Barrows, 2001; Niemz et al. 2005), we were unable to find any studies that investigated the relationship between actual academic performance and Internet use among college students. Based on the literature, we expected higher levels of Internet use for non-academic purposes to be associated with lower academic performance.

A final purpose was to investigate the relationship between frequency of Internet use and frequency of use of alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drugs. Excessive drug and alcohol use has been identified with depression and numerous other social difficulties (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1999; Naimi, Brewer, Mokad, Denny, Sedula, & Marks, 2003). We reasoned that if excessive use of the Internet serves a similar purpose as the excessive use of alcohol and drugs, it could be associated with drug or alcohol use. Even though excessive Internet use has been widely described as an addiction and measured in ways similar to addiction to substances as defined by Rozin and Stoess (1993) (craving, lack of control over use, withdrawal symptoms, and tolerance), relatively few studies have investigated the relationship between Internet addiction and addiction to other behaviors (exercise, gambling, TV viewing, and video games) or substances (alcohol, caffeine, cigarettes, and chocolate) (Greenberg, Lewis, & Dodd, 1999). Even though most past research has not found individuals to have multiple addictions, Greenberg et al. (1999) did find correlations between Internet addiction and addiction to all the other behaviors and substances among a sample of 64 male and 65 female college students. Ko, Yen, Chen, Chen, Wu, & Yen (2006) also found a correlation between Internet addiction and substance use among a large sample of Taiwanese youth. Yen, Yen, Chen, Chen and Ko (2007) analyzed data from the same sample and examined family factors associated with both internet addiction and substance use. They found that the two had similar relationships to family factors. Yen, Ko, Yen, Chen, Chung and Chen (2008) found that both Internet addiction and substance use was associated with hostility and depression in the same sample. Accordingly, we predicted that high Internet use would be associated with high levels of drug and alcohol use, although we recognize that the studies cited above (Greenberg et al., 1999; Ko et al., 2006; Yen et al., 2007; Yen et al., 2008) investigated Internet addiction, not Internet use per se.

Methods

Variables and measures

Internet use: Our measures of Internet use were based on a recent study of Internet use among children and adolescents ages 8-18 (Rideout, Foehr & Roberts, 2010), with some adjustments to make the questions appropriate for college students. Students were asked:

1. The number of devices with Internet access they owned (laptop, desktop computer, cell phone and other portable devices). The number of devices owned was counted for an overall measure.

2. The total number of times they had used an Internet browser on the previous day (0, 1-3, 4-6, 7-9, 10 or more times). They were also asked about frequency of use on the last day they were at work, for school-related activities on the previous day, and for personal activities on the previous day (0, 1-3, 4-6, 7-8, 10 or more).

3. How often they use the Internet for the following purposes in a typical week: e-mail, social networking, search engine, videos, message board, instant messages, games, news sites, music, to make a purchase, visit website with sexually explicit content, and other (never, rarely, once a week, 2-5 times, daily, 2-5 times a day, more than 5 times a day). The items were averaged for an overall score.

4. How often they start or end their day by accessing the Internet (never, very rarely, occasionally, frequently, very frequently).

Depression: Respondents completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977), a highly reliable measure of depression (Alpha = .91 for our sample). The traditional scoring instructions were used.

Social activities and relationships: Students were also asked the following questions:

1. How often others complain about the amount of time they spend on the Internet (6 point scale from never to very frequently).

2. Time spent in face-to-face interaction with family or friends on the previous day (5 point scale from none to more than 3 hours).

3. Rated stress experienced from arguments with parents, or dissatisfaction with a relationship with a significant other (6 point scale from none to very high). The items were based on a study of depression among college students by Furr, Westefeld, McConnell and Jenkins (2001).

Drug use: Students were asked about their use of the following drugs:

1. How often they had used marihuana in the past 12 months (7 point scale from never to more than 20 times).

2. If they had ever used cocaine, crack cocaine, ecstasy, LSD, PCP, Ketamine, mushrooms, other hallucinogens, heroin, amphetamines or methamphetamine. The number of “yes” responses was summed to form a scale (0-11).

3. How often they had engaged in binge drinking in the past 12 months as defined by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism – five or more drinks in a row for men and four for women on a single occasion (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010) (7 point scale from never to more than 20 times).

Academic performance: Students were asked to self-report:

1. Their grades in the past 12 months (mostly As, As and Bs, Bs, Bs and Cs, Cs, Cs and Ds, Ds, Ds and Fs, Fs).

Participants

Four-hundred and fifty students in eight undergraduate Sociology, Anthropology, and Criminology courses at a public commuter university in the Midwest were invited to participate in an online survey. They received a small amount of extra course credit for their participation. After two reminders, 215 students responded, producing a response rate of 48%; a relatively high response rate for an Internet survey (Sue & Ritter, 2007). The median age of respondents was 23, which is exactly the same as the median age of the campus population. Seventy-four percent were women, which is higher than the campus population (59%), but similar to the gender breakdown of Sociology majors on the campus (72% female). In terms of race, 62% were white, 24% were African American, and the rest identified with other racial categories. The percentage of white students on campus is also 62%, but the percentage of African American students is lower, 18%. A higher percentage of Sociology majors are African American (32%), which probably accounts for this difference. Compared with the campus overall, women and African Americans appear to be overrepresented, which is probably due to Sociology majors being overrepresented in the sample.

Using a method described by Silvo, Saunders, Chang and Jiang (2006) to investigate response bias, we also examined correlations between order of response (early and late responders) and the key demographic, Internet, and other variables. The method assumes that late responders are similar to non-responders. The variables included age, gender, race, several measures of Internet use, the measure of depression, alcohol and drug use, and self-reported GPA. Only one significant correlation was found; late responders tended to have lower GPAs (r = -.146, p < .05). In summary, the sample appears to be fairly representative of Sociology majors on this campus, except that it probably over-represents students with higher GPAs.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Means, standard deviations, ranges and modal categories for all major study variables can be found in Table 1. Overall, Internet use was high among the students. The modal category for the number of times the respondent used the Internet on the previous day was 10 or more times. Internet use for work was relatively uncommon (modal category = none), but use for school and personal use was high (modal category = more than 3 hours on the previous day). E-mail use, using networking sites, and using a search engine were the most common activities (modal category = daily), while instant messaging, playing games, and visiting sexually explicit web sites was uncommon (modal category = never). Most students did not start or end their days on the Internet (modal categories = rarely and very rarely, respectively). Students owned an average of 2.17 Internet enabled devices.

The mean depression score was 14.6, below the cutoff of 16 for a diagnosis of depression, but still relatively high. It was rare for others to complain about the student’s use of the Internet (modal category = never), and face-to face interaction on the previous day was high (modal category = more than 3 hours). Stress from arguments with parents and dissatisfaction with a significant other was low (modal categories = none). Marijuana use in the past 12 month, and illicit drug use ever was relatively rare (modal categories = never, none), but binge drinking in the past 12 months was more common (mean = 2.94 on a 7 point scale, modal category = never). Self-reported GPAs were high (mean = 6.98 on a 9 point scale, modal category = mostly As and Bs).

Preliminary analysis

Several variables were investigated as possible control variables - gender, age, race (white/other), relationship status (single/other), children (yes/no), and if the student lived with his or her parents (yes/no). Average Internet use per week was correlated with age (r = -.17, p < .05, N = 200), gender (r = -.24, p < .001, N = 203), and the presence of children (r = -.15, p < .05, N = 202). Younger respondents, men, and respondents without children reported more average Internet use. In addition, men were more likely to use a search engine (r = -.17, p < .05, N = 200), watch videos (r = -.27, p < .001, N = 203), use a message board (r = -.16, p < .05, N = 203) visit a news site (r = -.15, p < .05, N = 203), use “other” web applications (r = -.26, p < .001, N = 203), and they were much more likely to visit a web site with sexually explicit content (r = -.55, p < .001, N = 205). Older respondents were less likely to visit a networking site (r = -.21, p < .01, N = 197), use a search engine (r = -.21, p < .01, N = 197), watch videos (r = -.22, p < .01, N = 199) and listen to music (r = -.29, p < .001, N = 201). Accordingly, gender and age were included as control variables in all further analyses. Parental status was not controlled because it was highly correlated with age (r = .63, p < .001, N = 200).

Most forms of Internet use were weakly to moderately correlated with one another. Controlling for age and gender, some of the strongest correlations were between personal use and times used on the previous day (r = .56, p < .001), ending the day on the internet (r = .41, p < .001), using a search engine (r = .42, p < .001), and playing games (r = .41, p < .001). Starting and ending the day on the Internet was moderately correlated (r = .46, p < .001), as was using social networking sites and instant messaging (r = .40, p < .001). Listening to music and watching videos (r = .55, p < .001) and listening to music and instant messaging (r = .40, p < .001) were also moderately correlated. However, none of the correlations were so high as to cause problems with collinearity in the regression models that follow.

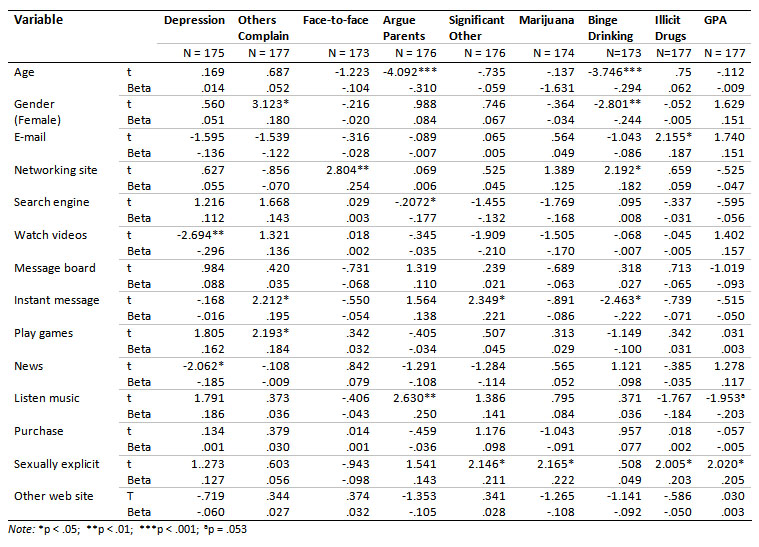

Regression analyses

Using OLS regression, two regression models were evaluated. The first model examined the relationships between general Internet use characteristics and depression, how often others complained about the respondent’s use of the internet, amount of face-to-face interaction on the previous day, stress from arguments with parents, stress from dissatisfaction with a significant other, marijuana use in the past year, illicit drug use over the lifetime, and GPA (Table 2). The second model focused on specific types of Internet use (Table 3) and the same dependent variables. Gender and age were included in the models as control variables.

Depression

Depression was negatively associated with starting the day on the Internet, and positively associated with ending the day on the Internet (Table 2). Viewing videos and visiting news sites was associated with lower levels of depression (Table 3).

Face-to-face interaction

The total numbers of devices owned, more Internet use for personal purposes (Table 2), and more time on social networking sites were all associated with higher levels of face-to-face interaction (Table 3).

Interpersonal problems

Others were more likely to complain about the respondent’s use of the Internet for personal use and work (Table 2). Others were also more likely to complain when the respondent was a woman, about instant messaging, and playing games (Table 3). Arguments with parents were associated with ending the day on the Internet (Table 2), using a search engine and listening to music (Table 3). Dissatisfaction with a relationship with a significant other was positively related to ending the day on the Internet (Table 2) more instant messaging, and visiting a sexually explicit website (Table 3).

Alcohol and drug use

More use of marijuana was related to visiting a sexually explicit web site (Table 3). Use of illicit drugs was associated with sending more e-mail and visiting a sexually explicit web site (Table 3). Binge drinking was related to more use of social networking sites and sending fewer instant messages (Table 3).

GPA

Use of the Internet for work purposes was negatively associated with GPA and starting the day on the Internet was positively associated with GPA (Table 2). GPA was negatively related to listening to music and positively associated with visiting a sexually explicit web site (Table 3).

Discussion

We found that use of the Internet for personal and school-related purposes was high among our sample of college students, but lower for work-related purposes. This is probably related to the integration of an Internet course delivery system (Blackboard™) at this university, and the fact that the students were young and probably did not hold professional level work positions that might require the use of the Internet. Similar to findings from other research (Pew, 2002), the use of e-mail was the most common way to communicate with others, but visiting networking sites was almost as frequent. The use of search engines was also common. Other uses of the Internet were much less common, especially visiting a sexually explicit web site, even though the growing acceptability of the use of pornography has been emphasized by the media and some analyses of popular culture (e.g., Paul, 2005). Consistent with other research on depression among college students, we also found symptoms of depression to be relatively high (American Psychiatric Association, 2009; Peterson, 2002; Voelker, 2003), but we did not find a gender difference, possibly because our sample was 74% female. The use of illicit drugs was low, but binge drinking was much more common, even though the modal category was “never.” Similar to other research (Odell, Korgen, Schumacher, & Delucchi, 2000; Sherman et al., 2000) we did find that an age and gender “digital divide” in Internet use still exists, with younger students and men reporting more use of the Internet. There was no gender or age difference in the use of e-mail, but older respondents were less likely to visit networking sites. However, we found no evidence of a racial difference in Internet use, which may reflect the widespread availability of Internet access to all students on this campus (Cotton, 2006). Moderate correlations between types of Internet use indicated that students who use the Internet for one purpose are likely to use it for multiple purposes, suggesting that the use of the Internet is a “normal” part of everyday life for these college students (Wellman & Haythornthwaite, 2002).

The frequency of Internet use was not related to symptoms of depression, and most specific types of Internet use were also unrelated, suggesting that Internet use is not a major cause or consequence of depression. However, the significant relationships that did emerge were primarily positive relationships. The findings lend some support to our original hypothesis that use of the Internet for social connection would be associated with fewer symptoms of depression and social problems, even though the use of e-mail was not significantly related to fewer symptoms of depression as predicted. Starting the day on the Internet was related to fewer symptoms of depression, possibly because starting the day on the Internet is an indication of a desire for social connectivity. It is interesting that the two specific types of Internet use that were related to fewer symptoms of depression were visiting news sites and viewing videos. Although we did not ask respondents about the specific videos they were viewing, it is possible that some of them were news related. In addition, many videos on sites such as YouTube are designed to be entertaining and are often humorous. Diddi and LaRose (2006) studied the formation of news habits (including Internet news sites) among a sample of college students. They found that Internet news seeking was related to surveillance needs, escapism, and entertainment, but the surveillance need was the strongest. Accordingly, Internet news seeking may bring about a feeling of connection with the social world, provide an escape from problems in one’s own life, as well as simply entertain. In addition, since many news stories portray extremely negative events (natural disasters, violent crime), the news consumer may feel fortunate by comparison. The only Internet behavior that was associated with more symptoms of depression was ending the day on the Internet. It was also associated with stress from arguments with parents and dissatisfaction with a significant other. Ending the day on the Internet might indicate a desire to escape from interpersonal problems.

Respondents reported that others were most likely to complain about frequent use of the Internet for personal purposes, work, instant messaging, and playing games. These are activities that individuals are likely performing in the co-presence of another person such as a family member or friend (e.g., surfing the Internet, sending e-mails or instant messages to co-workers or friends, and playing games, all of which distract from the focus of the current interaction). It is interesting that complaining was not related to visiting a sexually explicit website, which is an activity that one is not likely to perform in the presence of another person. Others were also more likely to complain about the Internet use of women, but only in the model that controlled for specific types of Internet use. It could be that women, often cast into the role of “nurturer,” are expected to be more attentive and sensitive to the needs of others in social interaction.

Consistent with “The Rich Get Richer” approach, in the few cases where Internet use was related to the amount of face-to-face interaction, all of the relationships were positive and there were no negative effects. Face-to-face interaction was related to owning more Internet enabled devices, high levels of use of the Internet for personal use, and visiting networking sites more frequently. Accordingly, it appears that Internet use does not necessarily replace actual social interaction as some had feared (Bargh & McKenna, 2004), but rather might be used to augment and facilitate social interaction. Park (2010), Sheldon (2008) and Peter et al. (2005) also found support for the “Rich Get Richer” approach.

On the other hand, some of our findings are consistent with the social compensation approach. In terms of stress from arguments with parents and dissatisfaction with significant others, the few significant relationships between Internet use and quality of relationships that were found tended to be negative. In addition to ending the day on the Internet (which has already been discussed) listening to music was associated with more arguments with parents (which might be a response to stress), and instant messaging and visiting a sexually explicit web site was associated with dissatisfaction with a significant other. Since instant messages tend to be sent close associates, the messages might actually be directed toward the significant other, and visiting sexually explicit web sites might be a way to compensate for sexual dissatisfaction with the significant other. These findings do suggest that using the Internet may be used to compensate for problematic relationships offline. These findings are consistent with the study conducted by Stamoulis and Farley (2010), and a study by Livingstone and Helsper (2007) that found that children and adolescents who are less satisfied with their lives are more likely to turn to the Internet for social communication. The exception was the negative relationship between using a search engine and arguments with parents; more use was actually associated with fewer arguments. Obtaining information through a search engine might be a way of ending arguments or resolving conflicts. That we found support for both the “Rich Get Richer” and the social compensation approaches (as did Peter et al., 2005) suggests the possibility that the Internet can be used for both purposes, and warrants more attention in future research.

We also investigated the actual use of substances (alcohol, illicit drugs, and marijuana) and Internet use. Consistent with previous research (Department of Health and Human Services, 2010), men and younger individuals were more likely to engage in binge drinking. For the most part, substance use was not associated with Internet use, but there were a few exceptions which were all related to specific types of Internet use. Binge drinking was associated with visiting a networking site, suggesting that certain types of Internet use may be used to promote social activities or those individuals with wider social networks are more likely to engage in binge drinking. The latter interpretation might be more likely, since binge drinking was actually associated with less use of instant messaging. Illicit drug use was associated with using e-mail, but since we did not ask for specific purposes of using e-mail, it is not clear why this relationship was found, except that e-mail might be used to promote social activities with others that involve drug use (similar to binge drinking). Of the other specific types of Internet use, only visiting a sexually explicit web site was associated with marijuana use and illicit drug use, which suggests that only this specific type of Internet use might be similar to actual use of substances. A similar argument has been made by Meerkerk, Van Den Eijnden and Garretsen (2006), who found in a longitudinal project that viewing erotica had the highest potential for the development of compulsive Internet use. This finding is not inconsistent with the findings of Greenberg et al. (1999), Ko et al. (2006), Yen et al. (2007), and Yen et al. (2008) regarding similarities between substance use and Internet use, but it is important to note that their research focused on Internet addiction rather than simply Internet use. Their measure of Internet addiction might have been tapping the viewing of sexually explicit content on web sites.

For the most part, Internet use did not have a strong impact on academic performance. GPA was negatively associated with higher levels of Internet use for work, and listening to music. This suggests that perhaps more demanding positions that require Internet use might interfere with academics, and listening to music may leave less time for studying or interfere with concentration. In fact, listening to music was negatively correlated with the number of hours the student spent studying (r = .19, p < .05). Starting the day on the Internet was positively associated with GPA, perhaps because the Internet is being used to obtain academically related information, or it is being used to complete course assignments.

Perhaps the most surprising finding was that visiting a sexually explicit site was positively associated with GPA. After investigating the relationships between visiting sexually explicit sites and other variables that might be related to GPA, we also found that visiting sexually explicit web sites was positively related to receiving a scholarship. It could be that more talented students simply have more time to visit these sites. A recent study on pornography-seeking behavior (Markey & Markey, 2010) may also shed light on this finding. Markey and Markey (2010) tested the “challenge hypothesis” in the context of vicariously winning or losing political elections. The challenge hypothesis argues that testosterone levels rise in response to a challenge, that winners of competitions experience greater increases, and higher testosterone levels are associated with increased sexual behavior. Based on data from the 2004, 2006, and 2008 elections, Markey and Markey (2010) found increases in Internet pornography-seeking behavior in states that voted for the winning political party. Achieving a high GPA may also be experienced as a challenge and success could be related to higher levels of pornography seeking. More research is needed to clarify this finding.

Limitations

One of the major limitations of our study is that it is cross-sectional, and therefore we are unable to establish causal relationships. The interpretations that we offer are based on the literature and plausible reasons for the associations that were found. Longitudinal research in this area is rare (Meerkerk et al., 2006; Kraut, et. al., 2002 are exceptions), and is needed to establish causal relationships. Our sample also over-represents women, African Americans, and students with higher GPAs. Accordingly, it should be noted that the findings related to GPA may not generalize to students with lower GPAs. The measure of GPA (although commonly used in research) was a self-report measure and may be inflated. The sample does appear to be representative of social science majors at this Midwestern, public, commuter university (sociology in particular), but the findings may not generalize to other majors or other types of universities.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we find that Internet use is associated with both positive and negative social and psychological variables, but should be understood in terms of specific types of Internet use rather than simply time on the Internet. Gordon et al. (2007) also argue that the reasons why individuals use the Internet must be taken into account in order to understand associations. Our findings on face-to-face interaction do not suggest that Internet use has replaced “real” social relationships. A considerable amount of past research has focused on the concept of Internet addiction, which has tended to emphasize the negative side of Internet use. Our findings suggest that this emphasis may have been misleading. Some of our most interesting findings had to do with the positive relationship between use of the Internet for news gathering and fewer symptoms of depression, and the positive and negative associations between viewing sexually explicit web sites and several social variables.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lauren Argue, Jonathan Bratcher, Robert Glass, Nathanael Marks, and Marquetta Wilson for their assistance in the construction of the questionnaire.

Notes

A condensed version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Applied and Clinical Sociology, October 2010, St. Louis, MO.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2009). Healthy minds. Healthy lives. Retrieved from http://www.healthyminds.org/More-Info-For/College-Age-Students.aspx

Anderson, K. J. (2001). Internet use among college students: An exploratory study. Journal of American College Health, 50(1), 21-26.

Bargh, J. A., & McKenna, K.Y. A. (2004). The Internet and social life. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 573-590.

Byun, S., Ruffini, B., Mills, J., et al. (2009). Internet addiction: Metasynthesis of 1996-2006 quantitative research. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12(2), 203-207.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/quickstats/binge_drinking.htm

Chak, K., & Leung, L. (2004). Shyness and locus of control as predictors of Internet addiction and Internet use. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(5), 559-570.

Chou, C., Condron, L., & Belland, J. C. (2005) A review of research on Internet addiction. Educational Psychology Review, 17, 363-388.

Chou, C., & Hsiao, M. (2000). Internet addiction, usage, gratification, and pleasure experience: the Taiwan college students’ case. Computers and Education, 35, 65-80.

Cotton, S. (2006). A disappearing digital divide among college students? Social Science Computer Review, 24(4), 497-506.

Department of Health & Human Services. (2010). Alcohol and drug information. Retrieved from http://ncadi.samhsa.gov/govpubs/rpo995/

Diddi, A., & LaRose, R. (2006). Getting hooked on the news: Uses and gratifications and the formation of news habits among college students in an Internet environment. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 50(2), 193-210.

Fortson, B. L., Scotti, J. R., Chen, Y., Malone, J., & Del Ben, K. S. (2007). Internet use, abuse, and dependence among students at a southeastern regional university. Journal of American College Health, 56(2), 137-144.

Furr, S. R., Westefeld, J. S., McConnell, G. N., & Jenkins, J. M. (2001). Suicide and depression among college students: A decade later. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32(1), 97-100.

Gordon, C. F., Juang, L. P., & Syed, M. (2007). Internet use and well-being among college students: Beyond frequency of use. Journal of College Student Development, 48(6), 674-688.

Greenberg, J. L., Lewis, S. E., & Dodd, D. K. (1999). Overlapping addictions and self-esteem among college men and women. Addictive Behaviors, 24(4), 565-571.

Kandall, J. J. (1998). Internet addiction on campus: The vulnerability of college students. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(1), 11-17.

Ko, C., Yen, J., Chen, C., Chen, S., Wu, K. & Yen, C. (2006). Tridimensional personality of adolescents with Internet addiction and substance use experience. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 51(14), 887-893.

Ko, C., Yen, J., Chen, C. S., Chen, C. C., & Yen, C. (2008). Psychiatric comorbidity of Internet addiction in college students: An interview study. CNS Spectr., 13(2), 147-153.

Kraut, R., Kiesler, S., Boneva, B., Cummings, J., Helgeson, V., & Crawford, A. (2002). Internet paradox revisited. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 1(2), 49-74.

Kraut, R., Patterson, M., Landmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukophadhyay, T., & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox: a social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist, 53, 1017-1031.

Kubey, R. W., Lavin, M. J., & Barrows, J. R. (2001). Internet use and collegiate academic performance decrements: Early findings. Journal of Communication, 51(2), 366-382.

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. (2007). Taking risks when communicating on the Internet: the role of offline social-psychological factors in young people’s vulnerability to online risks. Information, Communication & Society, 10 (5), 619-644. doi:10.1080/13691180701657998

LaRose, R. Eastin, M. S., & Gregg, J. (2001). Reformulating the Internet paradox: Social cognitive explanations of Internet use and depression. Journal of Online Behavior, 1(2). Retrieved from http://www.behavior.net/JOB/v1n1/paradox.html

Markey, P. M., & Markey, C. N. (2010). Changes in pornography-seeking behaviors following political elections: an examination of the challenge hypothesis. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(6), 442-446.

Meerkerk, G., Van Den Eijenden, R., & Garretsen, H. (2006). Predicting compulsive Internet use: It’s all about sex! CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9(1), 95-103.

Morahan-Martin, J., & Schumacher, P. (2000). Incidence and correlates of pathological Internet use among college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 16, 13-29.

Morahan-Martin, J., & Schumacher, P. (2003). Loneliness and social uses of the Internet. Computers in Human Behavior, 19, 659-671.

Morgan, C., & Cotton, S. R. (2004). The relationship between Internet activities and depressive symptoms in a sample of college freshmen. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 6(2), 133-142.

Naimi, T. S., Brewer, R. D., Mokad, A., Denny, C., Sedula, M. K., & Marks, J. S. (2003). Binge drinking among U.S. adults. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289, 70-75.

Niemz, K., Griffins, M., & Banyard, P. (2005). Prevalence of pathological Internet use among university students and correlations with self-esteem, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) and disinhibition. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 8(6), 562-570.

Odell, P. M., Korgen, K. O., Schumacher, P., & Delucchi, M. (2000). Internet use among female and male college students. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 3(5), 855-862.

Park, N. (2010). Integration of Internet use with public spaces: College students’ use of the wireless Internet and offline socializing. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 4(2). Retrieved from http://www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2010112501&article=4

Paul, P. (2005). Pornified: How pornography is transforming our lives, our relationships and our families. Time Books.

Peter, J., Valkenburg, P., & Schouten, A. (2005). Developing a model of adolescent friendship formation on the Internet. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 8(5), 423-430. doi:10.1089/cpb.2005.8.423

Peterson, K. S. (2008). Depression among college students rising. USA Today, Retrieved from http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/mental/2002-05-22-college-depression.htm

Pew Internet and American Life. (2002, September 15). The internet goes to college: How students are living in the future with today’s technology. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED472669.pdf

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385-401.

Rideout, V. J., Foehr, U. G., & Roberts, D. F. (2010). Generation M2: media in the lives of 8- to 18-year-olds. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/8010.cfm

Rozin, P., & Stoess, C. (1993). Is there a general tendency to become addicted? Addictive Behaviors, 18, 81-87.

Sheldon, P. (2008). The relationship between unwillingness-to-communicate and students’ Facebook use. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 20(2), 67-75. doi:10.1027/1864-1105.20.2.67

Sherman, R. C., End, C., Kraan, E., Cole, A., Campbell, J., Birchmeier, A., & Klausner, J. (2000). The internet gender gap among college students: Forgotten but not gone? CyberPsychology & Behavior, 3(5), 885-894.

Sivo, S. A., Saunders, C., Chang, Q., & Jiang, J. J. (2006). How low should you go? Low response rates and the validity of inference in IS questionnaire research. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 7(6), 351-414.

Stamoulis, K., & Farley, F. (2010) Conceptual approaches to adolescent risk-taking. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 4(1). Retrieved from http://www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2010050501

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (1999). The relationship between mental health and substance abuse among adolescents. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration.

Sue, V. M., & Ritter, L. A. (2007). Conducting online surveys. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore: Sage.

Voelker, R. (2003). Mounting student depression taxing campus mental health services. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(16), 2055-2056.

Wellman, B., & Haythornthwaite, C. (2002). (Eds.) The Internet in everyday life. Blackwell.

Yen, J., Yen, C., Chen, C., Chen, S., & Ko, C. (2007). Family factors of Internet addiction and substance use experience in Taiwanese adolescents. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10(3), doi:10.1089/cpb.2006.9948

Yen, J., Ko, C., Yen, C., Chen, S., Chung, W., & Chen C. (2008). Psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with Internet addiction: Comparison with substance use. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 62, 9-16.

Young, K., & Rodgers, R. (1998). The relationship between depression and Internet addiction. CyberPsychology, 1, 25-28.

Correspondence to:

Nancy Shields, Ph.D.

314-516-5093

Department of Anthropology, Sociology and Languages

One University Boulevard

574A Clark Hall

St. Louis, MO 63121

Email: Nancy_Shields(at)umsl.edu