Personality and Motivational Factors Predicting Internet Abuse at Work

Jengchung V. Chen1 , William H. Ross2 , Hsiao-Han Yang3

Abstract

Keywords: locus of control, uses and gratifications theory, Internet abuse, cyberloafing

Introduction

Many companies today use the Internet as a communication medium to improve efficiency and effectiveness; workers can access vast quantities of useful, work-related information. However, some employees also engage in Internet Abuse — Internet use that is not required by work or is outside of regular work usage (Mahatanankoon, Anandarajan, & Igbaria, 2004). Research on workplace Internet abuse at work (also called “cyberloafing” or “cyberslacking”) suggests that employees are likely to use non-work e-mail, and visit shopping-related websites, news, entertainment, and sports-related websites (Blanchard & Henle, 2008; Lee, Seong, & Jongheon, 2008). Such activities may result in negative consequences for both the company and its employees (Lee, Yoon, & Kim, 2008). Why do people engage in Internet abuse at work? The present study examines the effect of (1) the personality variable called Locus of Control and (2) motivational factors rooted in Uses & Gratifications theory on Internet abuse.

Locus of Control (LOC)

Rotter (1966) proposes that if a person tends to believe he/she has mastery over his/her own life and that his/her behavior leads directly to important outcomes, then he/she is high in internal LOC. If a person believes the results of his/her behavior are controlled by external forces (e.g., other people, luck), then he or she is high in external LOC.

Rotter proposes that internal and external LOC are two ends of a one-dimensional continuum. Yet, when researchers explore the factor structure of various LOC scales, they frequently find that internal and external LOC items load on separate factors (e.g., Macan, Trusty, & Tremble, 1996; Roberts & Ho, 1996). This two-factor solution suggests that each scale measures a person’s tendency to explain events in terms of internal attributions (e.g., effort, ability) or external attributions (e.g., luck, task difficulty), or both. Such explanations reflect general attribution theory (e.g., Clifford, 1976; Hyman, Stanley, & Burrows, 1991; Weiner, 1974).

Internet use has been shown to vary, based on personality factors (Weibel, Wissmath, & Groner, 2010). Research suggests those high in internal LOC welcome the opportunity to use computers, and believe that they can control the computer (Potosky & Bobko, 2001; Woodrow, 1990). Internal LOC individuals can also discipline their own computer use without feelings of restlessness or depression. By contrast, individuals with external LOC exhibit less self-control over their Internet use, and are more likely to stay on the Internet for extended periods of time (Chak & Leung, 2004). Research comparing those who admitted having been reprimanded at work or school for problematic Internet use with others also reports that the reprimanded group had diminished impulse control (Davis, Flett, & Besser, 2002). This suggests that those high in external LOC may be more likely to misuse computers at work. This may occur because of diminished self-control tendencies and/or a belief that being punished for misusing the internet is a random event. Together, these findings suggest our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: External locus of control predicts Internet abuse at work; those who are high (as opposed to those who are low) in external locus of control will report frequently abusing the Internet at work.

Uses and Gratifications Theory

Uses and Gratifications (U & G) theory, developed in the field of Communication Studies (Katz, Blumler, & Gurevitch, 1974) suggests that people select and use particular media in order to receive satisfaction from having needs, interests, or goals fulfilled (Stafford, 2008). The interactive nature of the Internet makes it a medium well-suited to examination from a U & G framework (Charney & Greenberg, 2002). Past research reveals that believing the Internet can satisfy several personal needs is an important indicator when predicting excessive and problematic Internet use among college students (Chou & Hsiao, 2000; Song, Larose, Eastin, & Lin, 2004).

There are a variety of possible needs and desires that one could seek to gratify through the Internet (Roy, 2009). However, a few dimensions have attracted the interest of researchers (e.g., Lin, 2007; Song, Larose, Eastin, & Lin, 2004; Wu, Wang, & Tsai, 2010) and these dimensions seem relevant for the present investigation.

One U & G dimension involves participating in a virtual community, such as “Facebook,” “MySpace,” and “Second Life.” Barker (2009) suggests that people frequently use social network websites to communicate with close friends, and to pass the time (also see Lin, 2006). A similar motivation is present for those who use micro-blogging sites such as Twitter (Chen, 2011). This suggests that this dimension may predict the frequency with which people contact friends while at work.

A second U & G dimension involves a desire for pleasing aesthetics. Some people change the appearance of their web pages frequently (Raacke & Bonds-Raacke, 2008), suggesting that they may be particularly concerned with web page aesthetics and self-presentation issues. Others seek beautiful photographs to download for computer “screensaver” or “wallpaper” files. Even some virtual communities, such as Second Life, attract members, in part, because they can alter the appearance of their “avatar” (character) as well as customizing their possessions and landscape.

Third, many people use the Internet for diversion and entertainment. This can take a variety of forms including watching videos, listening to music, playing video games (Mottram & Fleming, 2009), and shopping. Internet shopping is quite common (e.g., on average, 3.7 million people shop or seek product information at American-based QVC.com each month, Quantcast, 2009). Logically, this U & G dimension seems particularly relevant for some forms of Internet abuse at work, such as shopping and searching for non-work-related information.

A fourth U & G dimension involves maintaining relationships. In addition to using social networking websites for this purpose, Internet-based e-mail may be used to communicate with friends and family (Weiser, 2000). Some people include personal content in their e-mail messages and find such exchanges particularly gratifying (Boneva, Kraut, & Frohlich, 2001). These findings, combined with Chou and Hsiao’s (2000) study in which “social communications with online parties” emerged as a predictor for the amount of time people spent on the Internet, suggest that many people tend to focus on gratifying social needs when utilizing many Internet services. Maintaining relationships may play a part in Internet abuse at work – particularly when it comes to contacting friends while at work.

In summary, numerous studies suggest that many people use the Internet for personal gratification purposes. This suggests the following:

Hypothesis 2: Internet Uses & Gratifications theory predicts Internet abuse at work. Specifically, (a) the dimension of “finding diversion and entertainment” predicts shopping and searching for non-work-related information at work, and (b) the dimensions of “participating in a virtual community” and “maintaining relationships” predict the frequency of contacting friends from the workplace.

Demographic Factors

Very little research relates demographic factors such as education level, sex, and age to Internet abuse at work, although some research has related these variables to Internet use generally. Frequently, these studies produce contradictory or nonsignificant findings. An exhaustive review of these factors is beyond the scope of the present paper. However, a brief review of some relevant research may suggest additional hypotheses for each of these three demographic variables.

Education Level

One early study reports that education level is positively related to both the amount of time spent on the Internet each day and the amount of time spent for personal, rather than business-related, reasons (Korgaonkar & Wolin, 1999). Similarly, Rock, Hira, and Loibl (2010) report that, after controlling for income, better-educated Americans were more likely than others to use the Internet for personal financial purposes (e.g., online banking). Other research suggests that among samples of children (e.g., Calvert, Rideout, Woolard, Barr, & Strouse, 2005), young people (Vromen, 2007), and the elderly (Eastman, & Iyer, 2004), education level predicts Internet use.

Turning to research directly investigating Internet abuse at work, Garrett & Danzinger (2008) report that education level predicts the self-reported frequency of personal Internet use. Another study reports that education level predicts total amount of e-mail use and has a marginal effect (p = .06) for the amount of personal, non-work-related e-mail sent at work (Phillips & Reddie, 2007). Using a composite measure of several Internet-based communication methods, Vitak, Crouse, and LaRose (2011) do not replicate the Phillips & Reddie finding. However, they do report that education predicts “Cyberslacking variety” – the number of different types of Internet abuse a person admits to performing. This finding is significant even after people report the amount of control that they have at work (perhaps tapping into external locus of control beliefs; such a belief was also significant). Together, these findings suggest that education level may be positively related to Internet abuse at work. Therefore, we offer the following:

Hypothesis 3: Education level is positively related to the frequency of Internet abuse at work.

Age

Most research on Internet use has tended to use one specific age group (such as college-age adults) as subjects, thus limiting scientists’ ability to test the age-Internet abuse relationship. Among studies with participants drawn from multiple age groups, some report that age is positively related to the amount of time spent on the Internet for personal reasons (Korgaonkar & Wolin, 1999; Rock, Hira, & Loibl, 2010). However, Akman and Mishra (2010) report that in Turkey, age is negatively related to the amount of time spent accessing information, and is marginally related (p = .063) to using Internet-based electronic services such as shopping and banking. Similarly, Phillips and Reddie (2007) report that younger workers spend more time on personal e-mail than older workers. Vitak et al. (2011) report that age is negatively related to Internet abuse at work among Americans.

Some studies show a positive relationship between age and Internet use or abuse. Others show a negative relationship. With research studies showing opposite effects it seems imprudent to offer a specific hypothesis; yet it seems wise to control for age.

Gender

Much of the research on gender differences suggests that both women and men use the Internet with similar frequency (e.g., Akman & Mishra, 2010; Korgaonkar & Wolin, 1999; Teo & Lim, 2000) and similar motivations (e.g., a desire to participate in a virtual community) often lead both men and women to use specific sites such as multi-player games (e.g., Chen, Chen, & Ross, 2010). Even so, men and women often use the Internet in slightly different ways. For example, while both men and women frequent social networking websites, women are more likely than men to mention their “significant other” in their posts (Mangnuson & Dundes, 2008). Women are also more sensitive to symbolic and social aspects of the photographs they post to social networking websites (Siibak, 2009). Thus, it seems unlikely that frequency measures of Internet abuse behaviors, such as those employed in the present study, will vary based on the respondent’s gender.

Other research offers contradictory conclusions. Vitak et al. (2011) report small but significant effects such that men are more likely to use the Internet for personal communication (e.g., through social networking websites, e-mail, and instant messaging); Garrett and Danzinger (2008) also report that men are more likely to use the Internet for personal reasons when at work. However, Fang and Yen (2006) as well as Akman and Mishra (2010) report that women are more likely to use the Internet for personal communication (primarily via e-mail).

The present study investigates the frequency of various forms of Internet abuse. As noted, frequency measures reported in the published literature either show contradictory or nonsignificant gender effects. Therefore, no hypothesis regarding gender will be offered.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

A random sample of full-time employees with Internet access at work (n = 221 men and 99 women) of the Southern Taiwan Science Park served as subjects via an online survey as part of a larger research program (see Chen, Chen, & Yang, 2008). The park has shown exponential growth; at the time of the survey, between 41,000 and 47,000 employees in this science park worked in the following industries: integrated computer circuits (22%), optical electronics (63%), telecommunication (2%), precision machinery (3%), biotechnology (6%), computer peripherals (1%), and other industries (3%). The survey respondents generally reflected this industrial composition, although more respondents came from biotechnology and computer peripheral industries and fewer came from optical electronics industries. The sample composition was as follows: integrated computer circuits (21%), optical electronics (20%), telecommunication (7%), precision machinery (4%), biotechnology (17%), computer peripherals (22%), and other industries (9%). The survey was available for three weeks. To encourage responses, the names of those completing the survey were entered in a lottery for gift certificates at a department store located in the science park store and for specific prizes, including one of five iPhones. The initial response rate was 351 but 31 surveys were excluded due to missing data.

In terms of education level, 4% (n = 13) had a high school education or less, 8% (n = 25) had some college or a two-year college degree, 49% (n = 157) had a four year degree, 38% (n = 123) had a master’s degree, and less than 1% (n = 2) held Ph.D. degrees. When compared to the characteristics of the employees reported independently by park administration in 2006 (Southern Taiwan Science Park, 2011), the sample was somewhat better educated than all employees in the park (i.e., 32% of the employees throughout the science park had only a high school education, 27% had some college, 25% had bachelor’s degrees and only 14% had a master’s degree).

Regarding age, 84% (n = 268) of the participants were between 20 and 30 years old, 14% (n = 46) were between 30 and 40 years old, and 2% (n = 6) were over 40 years old. Among the respondents, 13% (n = 42) were technicians, 58% (n = 186) were engineers, 3% (n = 8) were department-level managers, 12% (n = 40) were mid-level assistant managers, less than 2% (n = 5) were middle-level or upper-level managers, and 12% (n = 39) held other positions.

Measurement Instruments

Locus of control. This variable was measured by a nine-item Chinese-language scale. This measure used five-point Likert-type rating scales with anchors ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree.” It consisted of two subscales: an internal Locus of Control (LOC) scale comprised of four items (alpha = .56; sample item, “The reason I can achieve my goals is that I work very hard”), where higher scores reflected an internal LOC, and an external LOC scale comprised of five items (alpha = .67; sample item, “I feel that if someone achieves something big it is merely because of good luck”), where higher scores reflected an external LOC. The two scales were essentially uncorrelated (r = -.08, ns). A factor analysis using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 17) tested this factor structure using principal components factor extraction with varimax rotation. Two factors emerged for explaining 43.7% of the variance. Rotated factor loadings ranged from .57 to .71.

Internet Uses and Gratifications. The following Internet Uses & Gratifications scales (Song et al., 2004) were used in the present study: Virtual Community (alpha = .85; sample item, “Find more interesting people than in real life”), Aesthetic Experience (alpha = .87; sample item, “See attractive graphics”), Diversion & Entertainment (alpha = .85; sample item, “Feel entertained”) and Maintaining Relationships (alpha = .67; sample item, “Get in touch with people I know”). Because each scale produced somewhat different patterns of correlations (see below), they were kept distinct. However, because they were intercorrelated, the total score from these scales was also reported (alpha = .88). These measures used five-point Likert-type rating scales with anchors ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree.”

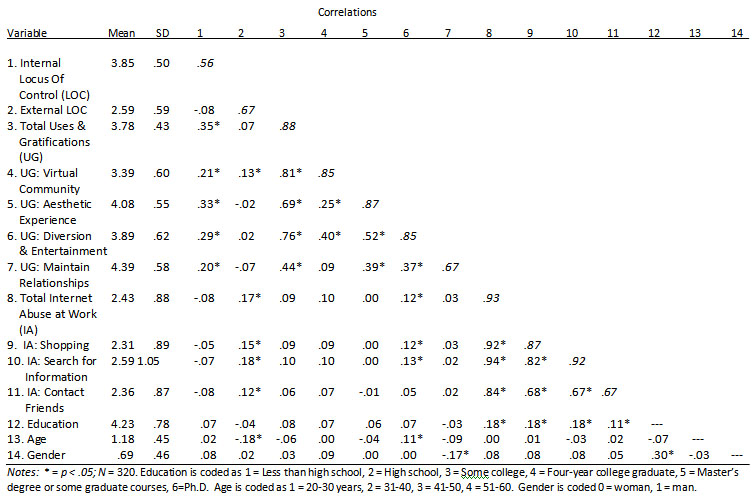

Internet Abuse at Work. This variable was measured using a set of scales developed by Mahatanankoon et al. (2004). These measures ask employees about the extent to which they performed three types of non-work-related Internet activities while at work. These were: (1) conducting personal business such as shopping (alpha = .87; sample item, “Conducting personal investment and banking activities”), (2) searching for non-work-related information (alpha = .92; sample item, “Researching personal hobbies”), and (3) contacting friends (alpha = .67; sample item, “Sending e-cards, e-flowers, e-gifts, etc. to friends and family”). These scales used five-point Likert-type rating scales with anchors ranging from “Never” to “Always.” Again, because the subscales were highly correlated an average score across all the items from this measure was also computed (alpha = .93). Scale correlations (with coefficient alphas along the diagonal) are found in Table 1.

Results

Shopping while at work

A hierarchical multiple regression investigated the factors predicting Internet abuse in the form of shopping while at work. At step one, the demographic variables of education level, gender, and age were entered. This model was significant, but with modest effects, F (3, 316) = 3.443; p = .017; R2 = 3.2%. Gender was not significant (B = .05; Std. Error = .111; Beta = .026; t-value = .447; ns); neither was age (B = .048; Std. Error = .110; Beta = .024; t-value = .437; ns). The only demographic variable that was significant was education level (B = .192; Std. Error = .066; Beta = .169; t-value = 2.902; p < .01).

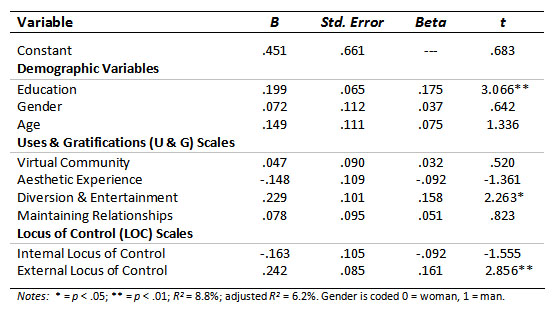

At step two, the personality and motivational variables, as measured by the LOC and the Internet Uses & Gratifications scales were entered. The effects for this model were also significant, F (9, 310) = 3.330; p = .001; R2 = 8.8%; adjusted R2 = 6.2%; Δ R2 = 5.7%; Δ F (6, 310) = 3.202; p = .005. The results for the second model are presented in Table 2.

It can be seen from Table 2 that education level continued to be a significant predictor for shopping while at work, with more educated employees being more likely to engage in this form of Internet abuse. Both the desire for “finding diversion and entertainment” and the external LOC personality variable also significantly predicted the frequency of online shopping while at work. These latter findings support both Hypotheses 1 and 2a.

Searching for Information

A hierarchical multiple regression investigated a second form of Internet abuse: searching for non-work-related information while at work. At step one of the regression, the demographic variables of education level, gender, and age were entered. This model was significant, F (3, 316) = 3.798; p = .011; R2 = 3.5%. Gender was not significant (B = .074; Std. Error = .132; Beta = .032; t-value = .560; ns); neither was age (B = -.034; Std. Error = .130; Beta = -.014; t-value = .257; ns). Education level was the only demographic variable that produced significant effects (B = .233; Std. Error = .078; Beta = .173; t-value = 2.981; p < .01).

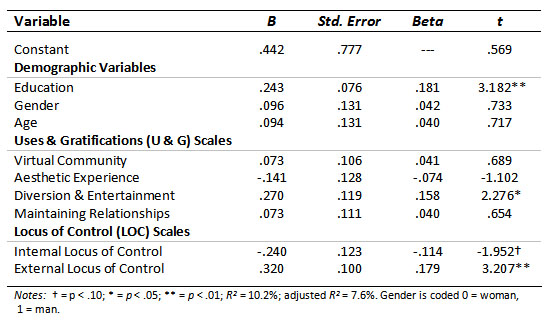

At step two, the personality and motivational variables, as measured by the LOC and the Internet Uses & Gratifications scales were entered. The effects for this model were also significant, F (9, 310) = 3.898; p < .001; R2 = 10.2%; adjusted R2 = 7.6%; Δ R2 = 6.7%; Δ F (6, 310) = 3.846; p = .001. The results for the second model are presented in Table 3.

It can be seen from Table 3 that education level continued to be a significant predictor for searching for non-work-related information. Both the desire for “finding diversion and entertainment” and the external LOC personality variable also significantly predicted the frequency of this form of Internet abuse while at work. These latter findings support both Hypotheses 1 and 2a.

Contacting Friends

A third hierarchical multiple regression investigated the factors predicting how frequently employees used the Internet to contact friends while at work. At step one, the demographic variables of education level, gender, and age were entered. This model was not significant, F (3, 316) = 1.497; p = .21 (ns); R2 = 1.4%. Gender was not significant (B = .036; Std. Error = .119; Beta = .017; t-value = .298; ns); neither was age (B = .058; Std. Error = .118; Beta = .028; t-value = .493; ns). Educational level had a marginally-significant effect (B = .133; Std. Error = .071; Beta = .111; t-value = 1.889; p = .06).

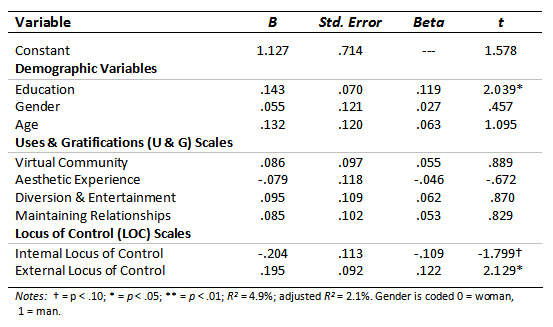

At step two, the personality and motivational variables, as measured by the LOC and the Internet Uses & Gratifications scales were entered. Although close, the effects for this model did not meet conventional significant levels, F (9, 310) = 1.75; p = .075 (ns); R2 = 4.9%; adjusted R2 = 2.1%; Δ R2 = 3.5%; Δ F (6, 310) = 1.878; p = .084 (ns). The results for the second model are presented in Table 4.

It can be seen from Table 4 that in the second model education level emerged as a significant predictor (t-value = 2.039; p < .05) of an employee contacting his or her friends via the Internet when that employee was supposed to be working. Neither the desire to participate in a virtual community nor the desire to use the Internet to maintain existing relationships predicted the frequency of contacting friends while at work. This failed to support Hypothesis 2b. While internal LOC had a marginal effect (t-value = 1.799; p = .073), external LOC had a significant effect (t-value = 2.129; p = .034), consistent with Hypothesis 1. Nevertheless, any specific significant results must be interpreted with caution because the overall regression was not statistically significant.

Discussion

The results provided some support for the hypotheses: External LOC predicted Internet Abuse at Work in the forms of shopping at work, searching for non-work-related information, and contacting friends when one was supposed to be working (supporting Hypothesis 1). Concepts derived from Uses & Gratifications theory – specifically the desire to find diversion and entertainment over the Internet – predicted the frequency of shopping from work and searching for non-work-related information (supporting Hypothesis 2a). However, neither the desire to participate in a virtual community nor the desire to maintain relationships predicted the frequency of contacting friends via the Internet while at work (Hypothesis 2b). Education was positively related with all three forms of Internet abuse (supporting Hypothesis 3).

Collectively, these results suggested that both Locus of Control and the desire to find diversion and entertainment predicted certain forms of Internet abuse at work. For some employees, the belief that external factors, such as luck, controlled one’s outcomes probably meant that they believed that receiving punishment for abusing the Internet was a random event beyond their control; therefore, abusing the Internet was worth the risk. This also perhaps reflected a lack of self-control or a failure to set work-related goals. If one did not set goals, then it was easy to fill one’s time with distractions from the Internet. For other employees, Internet abuse appeared to be more goal-oriented. Employees appeared to identify specific needs to be fulfilled – primarily the desire to find diversion and entertainment – and then used the Internet at work to fulfill those needs when they were supposed to be working.

These results extended findings from previous research in several ways. First, previous research had typically considered Internet abuse at work as a unitary concept: either a person used the Internet for personal reasons at work or they did not. While the present study’s findings could be considered at that level (using the correlations found in Table 1), the present findings provided a more fine-grained analysis and demonstrated that factors that predicted some forms of Internet abuse at work did not predict other forms of Internet abuse. Other recently-published research has also begun to look at specific predictors for different forms of Internet abuse. For example, Vitak et al. (2011) reported that while gender did not predict many forms of Internet abuse, men were more likely than women to read weblogs (‘blogs’) and to watch YouTube videos; they also found that people with creative jobs were likely to post blogs rather than work. Future research must continue to explore such personality, motivational, demographic, and organizational factors and how they predict specific forms of Internet abuse at work.

Second, measures constructed to measure concepts derived from Uses & Gratifications theory are multidimensional (e.g., Roy, 2009; Song et al., 2004). Yet when investigators used confirmatory factor analysis and structural equations modeling, so many items were sometimes removed that these measures became unidimensional (e.g., Chen, Chen, & Yang, 2008) and the scales no longer retained their richness and complexity. The present study kept several measures distinct, allowing us to determine which specific motivational variables predicted specific behaviors. This latter approach is more consistent with Uses & Gratifications theory and with research investigating the use of other media (e.g., Yung, Juran, & McMillan, 2009).

Third, much of the previous research on Internet abuse emphasized the role of Internet addiction. This pathological variable was defined as a person having a compulsive desire to use the Internet frequently and for long periods, other aspects of his/her life suffering from excessive Internet use, and the person experiencing withdrawal symptoms when Internet use was reduced (Young, 1998). Previous research demonstrated that using the Internet for personal gratification purposes was related to Internet addiction (Charney & Greenberg, 2002; Chou & Hsiao, 2000; LaRose, 2011). Similarly, Locus of Control was shown to predict Internet Addiction (Chak & Leung, 2004); Internet addiction, in turn, could predict Internet use (in terms of number of hours spent on the Internet; Chak & Leung, 2004) and Internet abuse at work (Chen, Chen, & Yang, 2008; Griffiths, 2003). However, the present study demonstrated that external LOC and the desire to use the Internet for personal gratification purposes predicted Internet abuse at work directly, without necessarily invoking the intervening concept of Internet addiction.

Of course, intervening variables might play a role. Locus of Control is a broad personality factor that could be classified as a distal predictor of Internet abuse at work. More proximal personality factors such as impulsivity, self-control, conscientiousness, or sensitivity to organizational rewards and punishments could have an even greater impact on this type of behavior. Future research should incorporate proximal factors and investigate the role of such factors in conjunction with LOC for predicting Internet abuse at work.

Implications for Managers

The present study reminds managers that employees abuse the Internet at work for a variety of motives. A wise manager will seek to understand the motives of various individuals and demographic groups within his or her department and will seek to provide constructive, work-related channels for those motives. Managers should also develop Internet abuse policies and shape employee beliefs that Internet abuse will result in punishment. A commonly-reported belief among those high in external LOC is that their fate is controlled by powerful others (Levenson, 1974). Therefore, managers may consider shaping that belief so that external LOC workers will believe that they will be caught if they abuse the Internet. Because many employees have both a positive attitude toward using the Internet for personal matters and a habit of Internet abuse (Vitak et al., 2011) it may be impossible to prevent all personal Internet use at work. Therefore, managers may also want to provide opportunities for employees to conduct personal business on the Internet – on their own time, during breaks at work.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The present study was limited in that data were collected via one questionnaire. It is possible that common method variance accounted for much of the variance in the data. To test this possibility, a factor analysis with all questionnaire items (excluding age, gender, and education) was conducted. A one-factor solution clearly did not fit the data well (depending upon the criteria used for factor identification, e.g., a “Scree test”, there were at least three factors, and as many as six factors, collectively accounting for between 42.4% and 57.6% of the variance). Further, the second factor accounted for a substantial amount of variance relative to the first factor (11.7% vs. 23.1%). Thus, the results seem unlikely to be primarily due to common method variance.

The size of the statistically-significant effects were modest, explaining only about 5 to 11% of the variance in various forms of Internet abuse behaviors. This suggests that additional personality variables, such as self-regulation or situational variables, such as the perceived consequences of misbehavior, may add to our ability to explain various types of Internet abuse. Additional research in these areas is warranted.

Education emerged as a significant predictor, supporting Hypothesis 3, yet the reason for this is unclear. Given that education and income level are often correlated (Garrett & Danziger, 2008), perhaps better-educated workers had more discretionary income that they could spend shopping (we did not have access to income data so we could not test this). Yet even if education was a surrogate for income level, this would not account for education’s effects on other forms of Internet abuse. Perhaps more educated workers had jobs that afforded them more autonomy at work and thus more opportunity to engage in undetected Internet abuse.

In order to test this possibility a cross tabulation statistic was computed. Because of relatively few people in numerous education and position categories, it was necessary to collapse education into three levels: (1) less than a four-year college degree, (2) a four-year college degree, and (3) graduate-level college education. Similarly, positions were collapsed into three categories: (1) managerial, (2) technical/engineering, and (3) other. It seemed reasonable to assume that managerial and technical/engineer jobs offered more autonomy than did other types of jobs (e.g., receptionists, secretaries). A chi-square of education level X type of position was significant, chi-square (4) = 15.938, p = .003; phi = .22. Among those with less than a four-year degree (n = 38), eight were managers (21%), 25 were in technical/engineering positions (66%), and five were in other jobs (13%). Among those with a four-year college degree (n = 157), 27 worked as managers (17%), 101 worked in technical/engineering positions (64%), and 29 worked in other types of jobs (19%). Among those with graduate education (n = 125), 18 worked as managers (14%), 102 worked in technical or engineering jobs (82%), and five worked in other positions (4%). While the percentage of managers remained fairly constant across the education levels, clearly the percentage of technicians and engineers increased for those with a graduate education and the percentage working in other positions decreased. Without additional information about various jobs it is difficult to know whether autonomy accounted for the education effects, but this additional analysis seems consistent with that interpretation. Others (e.g. Garrett & Danziger, 2008) also suggest that autonomy at work affords significant opportunities for Internet abuse.

Another limitation is that the present study did not measure work norms. Some authors have suggested that workgroup norms might play a significant role in workplace Internet abuse (Lee, Yoon, & Kim, 2008) and that norms might interact with personality variables, including LOC (Blanchard & Henle, 2008). Future research must determine whether, and under what conditions, those with external LOC who believe that others control their fate are more susceptible to influence by workplace norms regarding various forms of Internet abuse. For example, workplace norms regarding contact friends through the Internet may be subject to different workplace norms than shopping, online gambling, or searching for information. How norms are communicated and enforced may have differential effects based, in part, upon the employee’s personality.

Finally, this study only identified antecedents of Internet abuse. It did not examine preventative measures, such as electronic monitoring or rehabilitative measures (e.g., employee counseling, see Young, 2007). Additional research must identify effective approaches for reducing unproductive behavior, given that different factors predict Internet abuse.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that external Locus of Control – the attributions and beliefs that the outcomes one receives are random and/or under the control of unpredictable, powerful others – is related to several forms of Internet abuse at work. The study also demonstrates that the desire to use the Internet to find diversion and entertainment correlates with two specific forms of Internet abuse: (1) online shopping, and (2) searching for non-work-related information. This research study suggests that investigators should continue to examine personality and motivational predictors of Internet abuse, and should investigate whether different variables predict distinct forms of Internet abuse. Finally, Internet abuse at work is not necessarily dependent upon the pathologically-oriented concept of Internet addiction; the present study demonstrates that there can be a direct link between personality and motivational variables and Internet abuse at work.

Managers need to attend to the many and varied causes of Internet abuse at work. By identifying such causes, managers may be able to tailor prevention approaches for their workgroups. Also, the present study identifies variables that Human Resource managers may find useful to measure when hiring new employees. However, there is a limited ability of any one personality variable or attitude to predict specific workplace behaviors. Thus, this research should be viewed as a first step. Future research may also identify additional variables that, when used in conjunction with these, will enhance managers’ ability to predict who is likely to misuse their computer. Thus, much research is needed to identify both additional antecedent factors and effective responses to Internet abuse at work.

Authors’ note

Thanks to Dr. Chun-Hsiung Liao for financial support for data collection. The present study involves the analysis and reanalysis (using different theoretical models, different measures, and different statistics) of parts a larger data set, some of which was employed with a previously-published study (Chen, Chen, & Yang, 2008). The authors also thank Dr. Charlie Chen and Tong Ye for assistance with translation.

References

Barker, V. (2009). Older adolescents' motivations for social network site use: The influence of gender, group identity, and collective self-esteem. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12, 209-213.

Blanchard, A.L., & Henle, C.A. (2008) Correlates of different forms of cyberloafing: The role of norms and external locus of control. Computers in Human Behavior, 24, 1067-1084.

Boneva, B., Kraut, R., & Frohlich, D. (2001). Using e-mail for personal relationships: The difference gender makes. American Behavioral Scientist, 45, 530-550.

Calvert, S. L., Rideout, V. J., Woolard, J. L., Barr, R. F., & Strouse, G. A. (2005). Age, ethnicity, and socioeconomic patterns in early computer use. American Behavioral Scientist, 48, 590-607.

Chak, K., & Leung, L. (2004). Shyness and locus of control as predictors of Internet addiction and Internet use. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7, 559-570.

Charney T. R, & Greenberg B. (2002). Uses and gratifications of the Internet. In C. A. Lin & D. J. Atkin (Eds.), Communication, technology, and society: New media adoption and uses (pp. 379 - 446). Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Chen, G. M. (2011). Tweet this: A uses and gratifications perspective on how active Twitter use gratifies a need to connect with others. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 755-762.

Chen, K., Chen, J. V., & Ross, W. H. (2010). Antecedents of online game dependency: The implications of multimedia realism and uses and gratifications theory. Journal of Database Management, 21(2), 69-99.

Chen, J.V., Chen, C.C., & Yang, H.H. (2008). An empirical evaluation of key factors contributing to internet abuse in the workplace. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 108, 87-106.

Chou, C., & Hsiao, M. C. (2000). Internet addiction, usage, gratification, and pleasure experience: the Taiwan college students' case. Computers & Education, 35, 65-80.

Clifford, M. (1976). A revised measure of locus of control. Child Study Journal, 6, 85-90.

Davis, R. A., Flett, G. L., & Besser, A. (2002). Validation of a new scale for measuring problematic Internet use: Implications for pre-employment screening. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 5, 331-345.

De Brabander, B, & Boone, C. (1990). Sex differences in perceived locus of control. The Journal of Social Psychology, 130, 271-272.

Eastman, J. K., & Iyer, R. (2004). The elderly's uses and attitudes towards the Internet. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 21(3), 208-220.

Fang, X., & Yen, D. C. (2006). Demographics and behavior of Internet users in China. Technology in Society, 28, 363-387.

Garrett, R. K., & Danzinger, J. N. (2008). On cyberslacking: Workplace status and personal Internet use at work. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11, 287-292.

Griffiths, M. (2003). Internet abuse in the workplace: Issues and concerns for employers and employment counselors. Journal of Employment Counseling, 40(2), 87-96.

Hansemark, O. C. (2003). Need for achievement, locus of control, and the prediction of business start-ups: A longitudinal study. Journal of Economic Psychology, 24, 301-319.

Hyman, G., Stanley, R., & Burrows, G. (1991). The relationship between three multidimensional locus of control scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51(2), 403-412.

Katz, E., Blumler, J., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). The use of mass communication. Beverly Hills, California: Sage.

Korgaonkar, P. K., & Wolin, L. D. (1999). A multivariate analysis of web usage. Journal of Advertising Research, 39(2), 53-68.

LaRose, R. (2011). Uses and gratifications of Internet addiction. In K. S. Young & C. de Abreu (Eds.), Internet addiction: A handbook and guide to evaluation and treatment (pp. 55-72). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Lee, S, Yoon, S.N., & Kim, J. (2008). The role of pluralistic ignorance in Internet abuse. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 48(3), 38-43.

Levenson, H. (1974). Activism and powerful others: Distinctions within the concept of internal-external control. Journal of Personality Assessment, 38, 377-383.

Lin, C. A. (2007). Interactive media technology and electronic shopping. In C. A. Lin, D. J. Atkin (Eds.), Communication technology and social change: Theory and implications (pp. 203-222). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Lin, H. F. (2006). Understanding behavioral intention to participate in virtual communities. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9, 540-547.

Macan, T., Trusty, M., & Trimble, S. (1996). Spector's work locus of control scale: Dimensionality and validity evidence. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 56, 349-357.

Magnuson, M. J., & Dundes, L. (2008). Gender differences in "social portraits" reflected in MySpace profiles. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11, 239-241.

Mahatanankoon, P., Anandarajan, M., & Igbaria M. (2004). Development of a measure of personal web usage in the workplace. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7, 93-104.

Mottram, A, & Fleming, M.J. (2009). Extraversion, impulsivity, and online group membership as predictors of problematic Internet use. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12, 319-321.

Potosky, D., & Bobko, P. (2001). A model for predicting computer experience from attitudes toward computers. Journal of Business and Psychology, 15, 391-404.

Quantcast. Demographics: Data as of May, 2009. Retrieved from http://www.quantcast.com/qvc.com#demographics

Phillips, J. G., & Reddie, L. (2007). Decisional style and self-reported E-mail use in the workplace. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(5), 2414-2428.

Raacke, J., & Bonds-Raacke, J. (2008). MySpace and Facebook: Applying the uses and gratifications theory to exploring friend-networking sites. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11, 169-174.

Roberts, L., & Ho, R. (1996). Development of an Australian health locus of control scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 20, 629-639.

Rock, W., Hira, T. K., & Loibl, C. (2010). The use of the Internet as a source of financial information by households in the United States: A national survey. International Journal of Management, 27, 754-769.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80, 1-28.

Roy, S. K. (2009). Internet uses and gratifications: A survey in the Indian context. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(4), 878-886.

Siibak, A. (2009). Constructing the self through photo selection: Visual impression management on social networking websites. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 3(1). Retrieved from http://www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2009061501&article=1

Song, I., Larose, R., Eastin, M. S, & Lin, C.A. (2004). Internet gratifications and Internet addiction: On the uses and abuses of new media. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7, 384-394.

Southern Taiwan Science Park (2011, January 20). Statistics: Employee's educational backgrounds. Retrieved from http://www.stsipa.gov.tw/STSIPA_UPLOAD/Statistic/1281526257525.pdf

Teo, T. S. H., & Lim, V. K. G. (2000). Gender differences in Internet usage and task preferences. Behaviour & Information Technology, 19(4), 283-295.

Stafford T. F. (2008). Social and usage-process motivations for consumer Internet access. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing, 20, 1-21.

Vitak, J., Crouse, J., & LaRose, R. (2011). Personal Internet use at work: Understanding cyberslacking. Computers in Human Behavior, in press. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.03.002.

Vromen, A. (2007). Australian young people's participatory practices and internet use. Information, Communication & Society, 10(1), 48-68.

Weibel, D., Wissmath, B., & Groner, R. (2010). Motives for creating a private website and personality of personal homepage owners in terms of extraversion and heuristic orientation. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 4(1). Retrieved from http://cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2010053101&article=5

Weiner, B. (1974). Achievement motivation and attribution theory. Morristown, N.J.: General Learning Press.

Weiser E. B. (2000). Gender differences in internet use patterns and Internet application preferences: A two-sample comparison. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 3, 167-178.

Woodrow, J. (1990). Locus of control and student teacher computer attitudes. Computers in Education, 14, 421-432.

Wu, J., Wang, S., & Tsai, H. (2010). Falling in love with online games: The uses and gratifications perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1862-1871.

Young, K. S. (1998). Caught in the net: How to recognize the signs of Internet addiction and a winning strategy for recovery. New York, NY: Wiley.

Young, K. S. (2007). Cognitive behavior therapy with Internet addicts: Treatment outcomes and implications. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10, 671-679.

Yung, K. C., Juran, K., & McMillan, S. J. (2009). Motivators for the intention to use mobile TV. International Journal of Advertising, 28(1), 147-167.

Correspondence to:

William H. Ross, Ph.D.

Department of Management

University of Wisconsin – La Crosse

1725 State Street

La Crosse, WI 54601

USA

Email: ross.will(at)uwlax.edu