Singles Seeking a Relationship and Pornography Spam E-mail: An Understanding of Consumer Purchasing Behavior and Behaviors Antecedent to Purchasing

Joshua Fogel1, Sam Shlivko22 Law student, New York Law School, New York, NY, USA

Abstract

Keywords: Internet, pornography, gender, advertising, e-commerce

Introduction

The Internet contains websites with sexually explicit materials (SEM) and pornography. College students find these websites of interest with most studies reporting prevalence rates of viewing these websites for SEM and pornography ranging from 40% to 47% (Boies, 2002; Buzzell, Foss, & Middleton, 2006; Goodson, McCormick, & Evans, 2000; Selwyn, 2008). Two studies differ from this pattern and most likely occur due to predominance or exclusivity of either males or females in the sample. One study of a sample of mostly female Russian college students reports a lower prevalence of only 5.8% that ever used the Internet for entertainment purposes of pornography (Palesh, Saltzman, & Koopman, 2004). The other study of only male Canadian college students reports higher prevalence rates for the past 6 months of 77% for Internet nudity and 62% for Internet sexual activity, while prevalence of 32% for Internet explicit material is similar to the majority of prevalence studies quoted above (Morrison, Ellis, Morrison, Bearden, & Harriman, 2006). With regard to prevalence of “unwanted pornography,” there is apparently only one study of college students in the United States which reports that 58.7% received unwanted pornography through either e-mail or instant messages (Finn, 2004).

A comprehensive review quotes that no research exists on what type of Internet pornography is preferred (whether initially, for repeated usage, or for avoidance) for amateur online pornography, deviant online pornography, or commercial mainstream pornography (Doring, 2009). With regard to a particular type of commercial pornography where marketing is done through spam e-mail, we are aware of only three studies conducted among college students with regard to spam e-mail and online pornography. First, in an experimental study, pornography spam e-mail with links to non-active commercial pornography websites were considered more offensive than non-sexual commercial spam e-mail (Khoo & Senn, 2004). Second, sexually explicit unsolicited Internet pop-up messages and sexually explicit unsolicited e-mail inbox messages had greater perceived positive attitudes than sexually explicit unsolicited junk e-mail messages. Predictors of positive attitudes for these three types of messages included curiosity for online SEM and being male (Nosko, Wood, & Desmarais, 2007). Third, those high in sexual disposition (versus those with low sexual disposition) and also those high in antisocial disposition (versus those with low antisocial disposition) had greater levels of opening a message or link in a message that you did not want that showed actual pictures of naked people or of people having sex (Shim, Lee, & Paul, 2007). Also, there was a statistical interaction among those with high antisocial disposition where those with high sexual disposition had greater interest in the message content than those with low sexual disposition (Shim et al., 2007).

To our knowledge, there are no studies on actual behavior of purchasing the pornography advertised in spam e-mail. We are aware that pornography spam e-mail advertisements arrive in the e-mail inboxes of college students. From a marketing perspective, it is useful to understand what type of consumer response the individuals sending these spam e-mails advertisements are receiving. We are also aware that spam e-mail marketing and especially marketing of pornography content may not be the most ethical marketing approach. Also, from a psychology perspective, it is useful to understand the behavior of college students and what personal demographic variables and selected psychological variables may be associated with the behavior of opening/reading and also purchasing of products advertised in pornography spam e-mail.

Research Question 1: Based upon this review, we have an overall research question related to the following topics. Is spam e-mail a venue for college students to: a) receive spam e-mail on pornography?, b) open and read spam e-mail on pornography?, and c) purchase from the website provided from the spam e-mail on pornography?

Single Status and Online SEM / Pornography

Personal demographic characteristics are associated with online SEM and pornography use. A comprehensive review reports that among adults, those who are not married are more likely than those married to use online pornography (Doring, 2009). Also, those adults happily married are less likely to view online SEM than those either unhappily married or not married (Stack, Wasserman, & Kern, 2004). Among adolescents, those with greater attitudes toward uncommitted sexual exploration (i.e., those who are not willing to enter into a committed relationship with exclusively one partner) are strongly associated with exposure to online SEM (Peter & Valkenburg, 2008). A review of studies of non-Internet pornography reports that single men are the greatest users of pornography and also that those married view less pornography than single men (Traeen, Nilsen, & Stigum, 2006).

Hypothesis 1: Based upon the literature reviewed for online SEM and pornography use, we believe that there may be greater interest among those who are “single and seeking a relationship” versus those who are not for spam e-mail on pornography. We compare those who are single and seeking a relationship to those who are not for receiving, opening/reading, and also purchasing from spam e-mail on pornography.

Personal Demographic Characteristics and Online SEM / Pornography

Age is a relevant demographic factor. Younger age is associated with Internet use of pornography among adult users of Internet pornography. Also, older age among adolescents is associated with adolescent use of Internet pornography (Doring, 2009). This comprehensive review also reports that race/ethnicity is associated with Internet pornography use where adolescent users of Internet pornography are more likely to be African American (Doring, 2009). Also, another study reports that among college students, twice as many Hispanics as whites were anxious about being caught viewing Internet pornography (Goodson et al., 2000).

A number of studies all report differences between men and women for viewing online SEM and pornography where men are more likely to view this content than women among college students (Boies, 2002; Byers, Menzies, & O'Grady, 2004; O'Reilly, Knox, & Zusman, 2007; Selwyn, 2008) and among young adults (Hald, 2006). One study explores the reasons for use and reports that men are significantly more likely than women to use Internet pornography for relationship purposes, mood management, habitual use, and fantasy motivation. Also by mood management, there were greater differences among men between those erotophobic (defined as sexually conservative and who try to avoid sexual stimulation and sexual behavior) and those erotophilic (defined as sexually liberal and who are more willing to experience sexual stimulation and sexual behavior) than among women. Greater levels of Internet pornography use for mood management occurred for those erotophilic as compared to those erotophobic (Paul & Shim, 2008).

Internet Demographic Characteristics and Online SEM /Pornography

With regard to Internet demographic characteristics, there are mixed findings for hours of Internet use. One study reports no association for hours of Internet use per day and either visiting a sexually explicit website or for downloading pornography (Buzzell et al., 2006). Another study reports a significant positive association for hours of Internet use per week and use of online SEM (Byers et al., 2004). Also, number of spam e-mails received had a positive correlation with receiving sexual spam e-mail among those of college age (<24 years) and working age (ages 24-60) (Grimes, Hough, & Signorella, 2007).

Hypothesis 2: After adjusting for “single and seeking a relationship” status, are personal demographic variables (age, gender, race/ethnicity) and Internet demographic variables (hours of daily Internet use, number of spam e-mails received daily) among college students associated with: a) receiving spam e-mail on pornography?, b) opening and reading spam e-mail on pornography?, and c) purchasing from the website provided from the spam e-mail on pornography? Based upon the literature reviewed above, we believe that each of these personal demographic and Internet demographic variables may potentially be associated with the pornography spam e-mail outcomes.

Psychological Characteristics and Online SEM /Pornography

Besides personal and Internet demographic characteristics, psychological characteristics are potentially of interest to understand the motivation for use of websites with SEM and pornography. Curiosity about sex and sexual arousal are reported in a number of studies as reasons for use of websites with SEM and pornography (Boies, 2002; Goodson et al., 2000; Goodson, McCormick, & Evans, 2001; Lam & Chan, 2007). Also, among male college students, there were significant inverse correlations of Internet pornography use with both genital satisfaction and also sexual self-esteem, while no relationship occurred for body self-esteem (Morrison et al., 2006). Furthermore, although not shown to be statistically significant by online dating, the compensation hypothesis suggests that those with high dating anxiety and low physical self-esteem are more likely than those with low dating anxiety and high physical self-esteem to look for casual partners on the Internet (Peter & Valkenburg, 2007). Also, although higher frequency of masturbation was associated among both men and women for general (i.e., not exclusively online) pornography use (Hald, 2006), and masturbation is sometimes used for stress relief (Zamboni & Crawford, 2002), there are apparently no studies on the association of online pornography use with stress or stress relief.

Hypothesis 3: After adjusting for “single and seeking a relationship” status and demographic variables, are psychological variables (self-esteem, perceived stress) among college students associated with: a) receiving spam e-mail on pornography?, b) opening and reading spam e-mail on pornography?, and c) purchasing from the website provided from the spam e-mail on pornography? Based upon the literature reviewed above, we believe that self-esteem and perceived stress may potentially be associated with the pornography spam e-mail outcomes. This hypothesis is more exploratory as there is either conflicting or limited literature on the relationship of pornography to these particular psychological variables.

Method

Participants and Procedures

College students (n=200) from an undergraduate commuter college located in New York City were surveyed. The response rate was 94.3% [(200 completed / 212 approached) *100%]. Students were approached in person by the researchers and completed anonymous surveys at the college in classrooms, the cafeteria, the library, and other public places. This used a convenience sample method. The researchers administering the survey did not see the content completed by the participant while the participant was completing it. As the survey was anonymous, once it was placed in the pile with the other surveys, which almost always happened since groups of students were approached, there was no way to identify and link the content completed to any participant. We believe that participants answered honestly due to our explanation to participants of the above anonymous data collection approach. Participants provided informed consent. The survey was exempt from Institutional Board Review and was conducted in an ethical manner in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Data were collected during May 2007.

Measures

Single and Seeking a Relationship Status

Participants were asked, “Are you single and seeking a relationship?” Response choices were measured categorically with either “no” or “yes.”

Demographic Variables

Demographic variables included continuous variables of age (years), hours of Internet use (daily), and number of spam e-mails received (daily). Categorical variables included sex (man/woman) and race/ethnicity (white/non-white).

Spam E-mail Items

These items were: 1) Did you receive spam e-mail about pornography in the past year?, 2) If yes, did you open and read the e-mail?, and 3) If you opened and read the e-mail, did you purchase anything from the website provided?

Psychological Questionnaires

Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale

The Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale contains 10 items and is measured with a Likert-style scale from 1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree (Rosenberg, 1986). A sample item is, “I take a positive attitude toward myself.” There are 5 reverse-coded items. A higher score indicates greater levels of self-esteem. This is a reliable and valid measure and has Cronbach alpha reliability that ranges from 0.77 to 0.88 (Rosenberg, 1986). The Cronbach alpha reliability calculated in this sample was 0.87.

Perceived Stress Scale

The Perceived Stress Scale contains 10 items and is measured with a Likert-style scale from 0=never to 4=very often (Cohen & Williamson, 1988). A sample item is, “In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and "stressed"?” There are 4 reverse-coded items. A higher score indicates greater levels of perceived stress. This is a reliable and valid measure and has Cronbach alpha reliability that ranges from 0.80 to 0.86 (Cohen & Williamson, 1988). The Cronbach alpha reliability calculated in this sample was 0.84.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe the demographic and psychological variables. This included mean and standard deviation values for the continuous variables and percentage and frequency for the categorical variables. Also, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare age as the dependent variable with the three variables of 1) received spam e-mail about pornography topics, 2) opened and read spam e-mail about pornography topics, and 3) purchased from spam e-mail about pornography topics. As appropriate, either Pearson chi square analyses or the Fisher’s exact test were used to compare the responses of those single and seeking a relationship to those who were not for the separate questions of received, opened/read, and purchased from spam e-mail about pornography topics. Lastly, we conducted a series of logistic regression analyses with three different outcome variables of 1) received spam e-mail about pornography topics, 2) opened and read spam e-mail about pornography topics, and 3) purchased from spam e-mail about pornography topics. For each outcome variable there were three models conducted. Model 1 included just the independent variable of single and seeking a relationship status. Model 2 included the independent variable of single and seeking a relationship status and also the demographic variables of age, sex, race/ethnicity, hours of Internet use, and number of spam e-mails received. Model 3 included all the variables included in Model 2 and also the psychological variables of self-esteem and perceived stress. The analyses were conducted with SPSS version 17 (SPSS, 2008).

Results

There were 71 (35.5%) participants who were single and seeking a relationship while 129 (64.5%) participants were not single and seeking a relationship. The mean age was 20.9 years (SD=1.99). Age ranged from age 16 (n=1) to age 28 (n=1). Of the 198 individuals reporting age, 95.5% (n=189) had age ranges from 18 through 24 years. The ANOVA analyses did not show any significant differences with regard to age for 1) received spam e-mail about pornography topics (p=0.50), 2) opened and read spam e-mail about pornography topics (p=0.41), and 3) purchased from spam e-mail about pornography topics (p=0.41). Also, the sample consisted of 64.5% (n=129) women and 56.5% non-whites (n=113). Daily Internet use was a mean of 3.9 hours (SD=2.45) and the mean number of spam e-mails received daily was 28.2 (SD=61.86). For the psychological variables, mean self-esteem was 30.7 (SD=5.47) and mean perceived stress was 19.2 (SD=6.13).

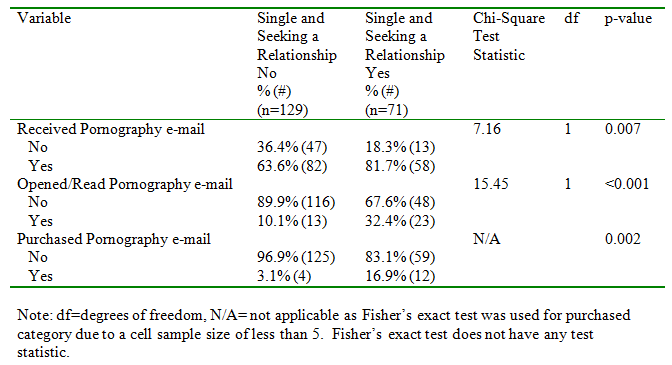

Table 1 shows comparisons for the status of single and seeking a relationship and spam e-mail behaviors. Those who were single and seeking a relationship reported that they received significantly more pornography spam e-mail than those who were not single and seeking a relationship. Almost one-third of those who were single and seeking a relationship reported that they opened and read pornography spam e-mail. This significantly differed from the approximately 10% of pornography spam e-mail opened and read by those who were not single and seeking a relationship. Also, those who were single and seeking a relationship had significantly greater percentages than those who were not to purchase from the website provided in the pornography spam e-mail. Almost 17% of those who were single and seeking a relationship did so while only approximately 3% did so from those who were not single and seeking a relationship.

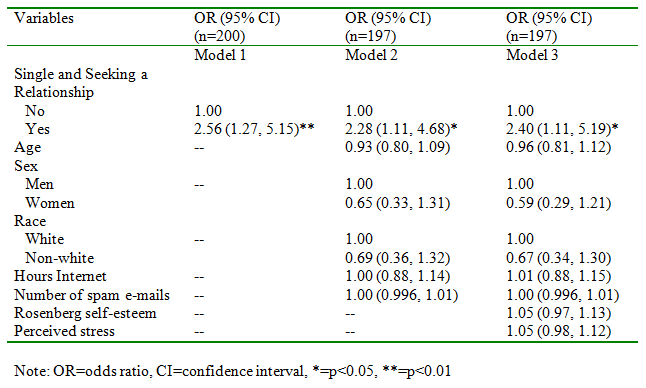

Table 2 shows the logistic regression analyses for received pornography spam e-mail. In all 3 models, those with a status of single and seeking a relationship were significantly associated with increased odds for having received pornography spam e-mail. The odds ratios were above 2 and were relatively similar for all 3 models, although the odds ratios were slightly lower in the two multivariate models. None of the demographic or psychological variables were significantly associated with having received pornography spam e-mail.

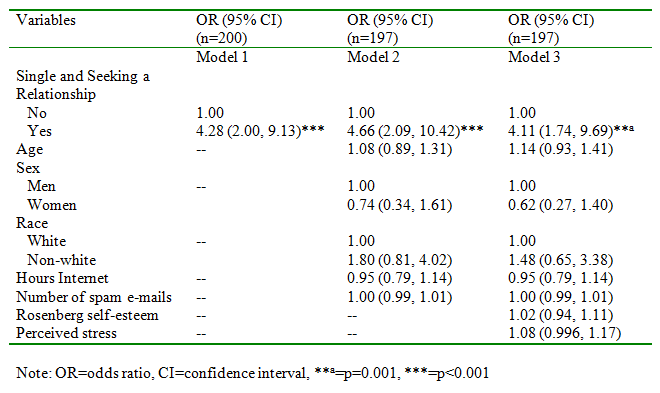

Table 3 shows the logistic regression analyses for opened and read pornography spam e-mail. In all 3 models, those with a status of single and seeking a relationship were significantly associated with increased odds for having opened and read pornography spam e-mail. The odds ratios were above 4 and were relatively similar for all 3 models, although the odds ratios were slightly higher in Model 2. None of the demographic variables were significantly associated with having opened and read pornography spam e-mail. In Model 3, increased perceived stress approached significance (p=0.06) for having opened and read pornography spam e-mail.

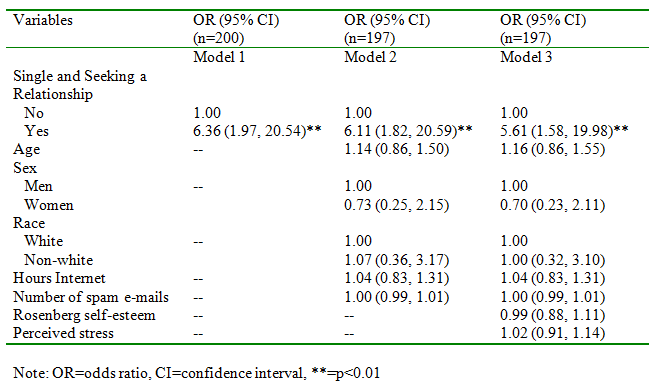

Table 4 shows the logistic regression analyses for purchased from pornography spam e-mail. In all 3 models, those with a status of single and seeking a relationship were significantly associated with increased odds for having purchased from pornography spam e-mail. The odds ratios were above 6 for both the univariate model and the model adjusting for demographic variables, while the odds ratio was above 5 for the model that adjusted for both demographic and psychological variables. None of the demographic or psychological variables were significantly associated with having purchased from pornography spam e-mail.

Discussion

We found strong support for the first hypothesis that those single and seeking a relationship had significantly greater percentages than those who were not single and seeking a relationship for receiving, opening/reading and also purchasing from spam e-mail about pornography. A similar significant pattern was found for those single and seeking a relationship in the different multivariate analyses adjusting for demographic and psychological variables. We did not find any support for the second hypothesis for demographic variables. No demographic variables were associated with receiving, opening/reading and also purchasing from spam e-mail about pornography. We did not find any support for the third hypothesis for psychological variables. No psychological variables were associated with receiving, opening/reading and also purchasing from spam e-mail about pornography.

Prevalence of Spam E-mail about Online Pornography

Both those single and seeking a relationship and those not single and seeking a relationship had very high percentages of individuals receiving pornography spam e-mail, with more than 60% from both groups receiving these e-mails. This was expected, as pornography is often a topic included in spam e-mail with more than half of e-mail users from all age groups in 2007 reporting receiving pornography spam e-mail (Fallows, 2007). The significantly higher levels for receiving pornography spam e-mail among those single and seeking a relationship may have occurred due to their greater interest in this topic. Also, these individuals may be part of a community for singles and/or talk about their single status on social network communities. Being part of such communities may expose them to receive pornography spam e-mail whether through a community e-mail or even through harvesting of the e-mail addresses of these individuals from those who send such spam e-mail. Also, those single and seeking a relationship may have placed their e-mail addresses on websites or registered on websites offering pornography topics.

With regard to opening/reading and purchasing from spam e-mail on pornography, as hypothesized, those single and seeking a relationship had significantly greater percentages that those not single and seeking a relationship for both opening/reading and also purchasing from pornography spam e-mail. A number of studies report that college students pay to register with online websites in order to obtain SEM and/or pornography with reported prevalence ranges of 1.5% to 5% (Byers et al., 2004; Goodson et al., 2001; Lam & Chan, 2007; Selwyn, 2008). In our study, the overall prevalence rate for purchasing from pornography spam e-mail was slightly higher at 8% [(4+12)/200]. We found that a major prevalence difference exists from previous research on prevalence rates when focusing on those single and seeking a relationship versus those who were not. Those single and seeking a relationship had 16.9% who purchased from pornography spam e-mail which is much higher than previous prevalence rates. Among those not single and seeking a relationship, the prevalence rates of 3.1% are very similar to the previously reported prevalence rates. Also, the fact that a small percentage of individuals who were not single and seeking a relationship purchased pornography from spam e-mail is not necessarily contrary to our hypothesis. There will be some individuals who are curious about pornography and will purchase these pornography products.

Single and Seeking a Relationship and Online Pornography Spam E-mail

We found an increasing incremental pattern for the odds ratios for receiving, opening/reading, and purchasing online pornography from spam e-mail among those single and seeking a relationship as compared to those who were not single and seeking a relationship. This pattern was consistent even after adjusting for numerous demographic and psychological variables. This pattern differs from the relatively similar odds ratio patterns reported for opening/reading and purchasing from spam e-mail for sexual performance products (Fogel & Shlivko, 2009) and weight loss products (Fogel & Shlivko, 2010) when comparing those with a particular health concern to those who did not have that particular health concern. We suggest that those single and seeking a relationship who open/read and/or purchase pornography from spam e-mail have different needs than those with physical health concerns and who have an interest in physical health products from spam e-mail. Among those single and seeking a relationship versus those who are not single and seeking a relationship, there is an increasing interest pattern that results in odds ratios increasing from 2 for receiving, to 4 for opening/reading, and depending upon the model of 5 to 6 for purchasing.

Demographic Variables and Online Pornography Spam E-mail

We did not find any relationship for any of the demographic variables for either receiving, opening/reading, or purchasing from online pornography spam e-mail. This is especially surprising for the demographic variable of sex, as numerous studies (Boies, 2002; Byers et al., 2004; Hald, 2006; O'Reilly et al., 2007; Selwyn, 2008) report that men are more likely to view online SEM and pornography than women. Also, in univariate analyses (data not shown) comparing sex to all three outcomes of receiving, opening/reading, or purchasing from online pornography spam e-mail, we did not find any significant differences between men and women. Our study suggests that unlike by online SEM and pornography, interest in spam e-mail for pornography is different from online SEM and pornography and there are no sex differences.

Psychological Variables and Online Pornography Spam E-mail

We did not find any statistical significance for self-esteem or perceived stress and receiving, opening/reading, or purchasing from online pornography spam e-mail. Although these psychological concerns can potentially be related to both offline and online pornography use, they are not relevant for online pornography spam e-mail.

Theoretical Considerations

What are some possible theoretical considerations for our finding that the status of single and seeking a relationship is significantly associated with the antecedents (i.e., receiving and also opening/reading) of purchasing from online pornography spam e-mail and also the behavior of purchasing from online pornography spam e-mail? First, this behavior may be occurring due the presence of an “uncommitted casual context” (Peter & Valkenburg, 2008) among those who were single and seeking a relationship. The lack of a committed relationship to one person can remove any possible barriers about avoiding pornography due to an exclusive romantic partner being angry about viewing such pornography content. Those who are single and seeking a relationship now are available to seek information about online pornography and to purchase from online pornography spam e-mail. Second, the recreation hypothesis suggests that sexual permissiveness is a key aspect for an individual to seek casual dates online (Peter & Valkenburg, 2007). Those who are single may allow themselves to be more sexually permissive, especially when receiving online pornography spam e-mail. They may then choose to see if this pornography is of interest and purchase these products too.

Study Limitations and Future Research

This study is only from one college and may not generalize to a national sample or to other colleges. Our lack of significance for sex differences is possibly contrary to much of the published literature on pornography and further studies would be useful to replicate this finding. Also, we did not inquire about sexual orientation or type of pornography websites where products were purchased. The topics advertised on particular websites and also targeting of audiences with a particular sexual orientation may have influenced the opening/reading and/or purchasing behavior. Lastly, we did not inquire if these individuals purchased only once or were frequent purchasers of the online pornography products advertised in the spam e-mail. Future research would be useful to measure actual frequency of purchases and also the particular types of pornography content viewed. Another area for future research is to include a third category of “single but not seeking a relationship.” Although in our sample we did not have individuals omitting an answer of yes/no to our question of “single and seeking a relationship,” there are some college students that are single and may not be interested in seeking a relationship. Lastly, it also would be useful to explore the many other potential psychological variables that can be related to viewing pornography and how they are associated with opening/reading and also purchasing spam e-mail on pornography.

Conclusions

Spam e-mail on pornography is of interest to college students. Those single and seeking a relationship are a group with a special interest in pornography spam e-mail. They are quite likely to open/read and also purchase from the pornography spam e-mail. Unlike previous research, there are no sex differences for interest in pornography spam e-mail.

References

Boies, S. C. (2002). University students' uses of and reactions to online sexual information and entertainment: Links to online and offline sexual behaviour. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 11(2), 77-89.

Buzzell, T., Foss, D., & Middleton, Z. (2006). Explaining use of online pornography: A test of self-control theory and opportunities for deviance. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 13(2), 96-116.

Byers, L. J., Menzies, K. S., & O'Grady, W. L. (2004). The impact of computer variables on the viewing and sending of sexually explicit material on the Internet: testing Cooper's 'triple-a engine'. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 13(3-4), 157-170.

Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health: Claremont symposium on applied social psychology (pp. 31-67). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Doring, N. M. (2009). The internet’s impact on sexuality: A critical review of 15 years of research. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(5), 1089-1101.

Fallows, D. (2007). Spam 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2010 from http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media/Files/Reports/2007/... Finn, J. (2004). A survey of online harassment at a university campus. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(4), 468-483.

Fogel, J., & Shlivko, S. (2009). Consumers with sexual performance problems and spam e-mail for sexual performance products. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce, 14(1). Retrieved March 7, 2010 from http://www.arraydev.com/commerce/jibc/2009-04/Fogel1.pdf

Fogel, J., & Shlivko, S. (2010). Weight problems and spam e-mail for weight loss products. Southern Medical Journal, 103(1), 31-36.

Goodson, P., McCormick, D., & Evans, A. (2000). Sex on the Internet: College students' emotional arousal when viewing sexually explicit materials on-line. Journal of Sex Education & Therapy, 25(4), 252-260.

Goodson, P., McCormick, D., & Evans, A. (2001). Searching for sexually explicit materials on the Internet: An exploratory study of college students' behavior and attitudes. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 30(2), 101-118.

Grimes, G. A., Hough, M. G., & Signorella, M. L. (2007). Email end users and spam: Relations of gender and age group to attitudes and actions. Computers in Human Behavior, 23, 318-332.

Hald, G. M. (2006). Gender differences in pornography consumption among young heterosexual Danish adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(5), 577-585.

Khoo, P. K., & Senn, C. Y. (2004). Not wanted in the inbox!: Evaluations of unsolicited and harassing e-mail. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28(3), 204-214.

Lam, C. B., & Chan, D. K.-S. (2007). The use of cyberpornography by young men in Hong Kong: Some psychosocial correlates. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(4), 588-598.

Morrison, T. G., Ellis, S. R., Morrison, M. A., Bearden, A., & Harriman, R. L. (2006). Exposure to sexually explicit material and variations in body esteem, genital attitudes, and sexual esteem among a sample of Canadian men. The Journal of Men's Studies, 14(2), 209-222.

Nosko, A., Wood, E., & Desmarais, S. (2007). Unsolicited online sexual material: What affects our attitudes and likelihood to search for more? Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 16(1-2), 1-10.

O'Reilly, S., Knox, D., & Zusman, M. E. (2007). College student attitudes toward pornography use. College Student Journal, 41(2), 402-406.

Palesh, O., Saltzman, K., & Koopman, C. (2004). Internet use and attitudes towards illicit internet use behavior in a sample of Russian college students. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(5), 553-558.

Paul, B., & Shim, J. W. (2008). Gender, sexual affect, and motivations for Internet pornography use. International Journal of Sexual Health, 20(3), 187-199.

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2007). Who looks for casual dates on the internet? A test of the compensation and the recreation hypothesis. New Media & Society, 9(3), 455-474.

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2008). Adolescents' exposure to sexually explicit Internet material, sexaul uncertaintly, and attitudes towrd uncommitted sexual exploration: Is there a link? Communication Research, 35(5), 579-601.

Rosenberg, M. (1986). Conceiving the Self. Malabar, FL: Krieger.

Selwyn, N. (2008). A safe haven for misbehaving? An investigation of online misbehavior among university students. Social Science Computer Review, 26(4), 446-465.

Shim, J. W., Lee, S., & Paul, B. (2007). Who responds to unsolicited sexually explicit materials on the internet?: The role of individual differences. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10(1), 71-79.

SPSS. (2008). SPSS, Version 17. Chicago: SPSS.

Stack, S., Wasserman, I., & Kern, R. (2004). Adult social bonds and use of Internet pornography. Social Science Quarterly, 85(1), 75-88.

Traeen, B., Nilsen, T. S., & Stigum, H. (2006). Use of pornography in traditional media and on the Internet in Norway. Journal of Sex Research, 43(3), 245-254.

Zamboni, B. D., & Crawford, I. (2002). Using masturbation in sex therapy: Relationships between masturbation, sexual desire, and sexual fantasy. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 14(2-3), 123-141.

Correspondence to:

Joshua Fogel, PhD

Brooklyn College of the City University of New York

Department of Finance and Business Management, 218A

2900 Bedford Avenue

Brooklyn, NY 11210

USA

Phone: (718) 951-3857

Fax: (718) 951-4867

e-mail: joshua.fogel(at)gmail.com