The Development and Validation of the Online Victimization Scale for Adolescents

Brendesha M. Tynes1, Chad A. Rose2, David R. Williams3Abstract

Keywords: online victimization, racial discrimination, scale, adolescent, Internet

Introduction

The Development and Validation of the Online Victimization Scale

Recent research shows that online victimization is a growing public health concern. From 2000 to 2005 the number of youth who report making rude or nasty comments to someone online doubled from 14% to 28% (Wolak, Mitchell, & Finkelhor, 2006). Studies have found that more than 30% of youth 17 and under experience cyberbullying (Hinduja & Patchin, 2008; Patchin & Hinduja, 2006) one in three females and one in ten males experience unwanted sexual solicitation online (Ybarra, Leaf, Diener-West, 2004). In addition, up to 71% of adolescents report either witnessing or personally experiencing racial victimization on the Internet (Tynes, Giang, Williams, & Thompson, 2008). Associations have been found between these online victimization experiences and depressive symptomatology (Tynes et al., 2008; Ybarra, 2004; Ybarra et al., 2004), multiple psychosocial challenges including substance use and delinquency (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004), and suicidal ideation (Hinduja & Patchin, 2009). Moreover, unwanted sexual solicitation and online racial victimization contribute a unique amount of variance to these outcomes over and above offline victimization (Mitchell, Ybarra, & Finkelhor, 2007; Tynes et al., 2008).

With the burgeoning body of literature documenting the prevalence of online victimization and its associations with ill-health, there are increasing differences in definitions and measurement for these experiences. For example, scholars have primarily utilized questionnaires that were developed for their specific studies. As a result, it has been difficult to make generalizations across studies about the nature and frequency of online victimization, as well as its impact on well-being. A comprehensive measure is needed to promote systematic study as the field of new media studies matures.

This study introduces a short instrument, the Online Victimization Scale (OVS), designed to measure adolescents’ general, sexual and racial victimization experiences. The definition of online victimization is adapted from Hinduja and Patchin’s (2009) definition of cyberbullying and includes disparaging remarks, symbols, images or behaviors that inflict harm through the use of computers, cell phones and other electronic devices. Harm may be experienced in one incident or repeatedly over time across domains related to the most salient aspects of the physical self, including appearance, gender and race. This definition includes hateful or sexual websites and images that an adolescent may inadvertently stumble upon while perusing the web as well as harm that may be “willful” or deliberate. This definition also accounts for experiences that may be vicariously experienced by online peers and adults.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical foundation for the scale is based on online re-embodiment theory posited in response to theorists such as Sherry Turkle (1995) who argue that the disembodiment of the Internet allows users to escape their physical selves for more fantasy-driven selves. These scholars argue that technological advances such as broadband have made participants more acutely aware of the body and that a convergence of technologies on the internet have brought forth visual and audio images that more closely represent the bodily form (Gies, 2008). Moreover Gies argues “the body is always present in the way in which we speak” (p 318). In this case even before the advent of new technologies that recreate the body, it was being done through text (Burkhalter, 1999; Tynes, Reynolds, & Greenfield, 2004). Indeed, computer mediated communication can actually enhance the importance of the body and cause interlocutors to constantly recreate their own and others’. Boler (2007) notes that these constructions of self and other are often stereotypical and include sexualized, gendered, and racialized bodies. This notion is borne out in empirical research on the internet (Subrahmanyam, Greenfield, & Tynes, 2004, Tynes et al, 2004). For example age, sex, location and race are consistently demanded of speakers and used to make meaning about and with online friends and potential romantic partners in chat rooms (although they are much less frequently used by adolescents today) (Boler, 2002; Tynes et al, 2004).

In addition, postings on the Internet including vocabulary, spelling mistakes and uses of idioms, reveals a speaker’s social status and cultural capital, their education, nationality, ethnicity, age and gender” (Gies, 2008). Drawing on this literature, the three central assumptions of re-embodiment theory are 1) electronic cues including images, video, writing and speech shape the online body, 2) the body enjoys heightened importance online, and 3) the social ills commonly associated with physical indicators of difference (e.g. racism) are recreated online (Smith & Kollock, 1999).

The design of the study also draws on theoretical contributions of Harrell (2000) and Quintana & McKown (2008). In much of the research to date on racial discrimination in face-to-face settings, direct experiences, or those that are directed explicitly at the individual, are assessed. In Quintana and McKown’s recent model of the influences of racism on the developing child, the authors note that vicarious experiences, those directed at same-race adults and peers in the child’s life, are equally detrimental. Similarly, Harrell’s (2000) multidimensional model of racism-related stress also stresses the importance of measuring daily racism microstressors as well as vicarious experiences. Daily racism microstressors (subtle, seemingly innocuous putdowns) are important to assess. Like Quintana & McKown vicarious experiences are deemed to impact the target. This includes witnessing jokes that are cracked about people in one’s ethnic group.

Measuring Online Victimization

Scholars have primarily used pencil and paper, telephone and online surveys to measure online victimization, a term used here that includes cyberbullying, electronic bullying, online harassment, unwanted sexual solicitation and exposure to unwanted sexual solicitation (Berson, Berson, & Ferron, 2002; Cassidy, Jackson, & Brown, 2009; Finkelhor, Mitchell, & Wolak, 2000; Kowalski & Limber, 2007; Shariff, 2008; Wang, Iannotti, Nansel, 2009; Williams & Guerra, 2007; Ybarra, Espelage & Mitchell, 2007). Although some scholars have also utilized focus groups (Agatston, Kowalski, & Limber, 2007; Smith, et al., 2008) and interviews (Tynes, 2007), we focus on surveys and specifically on those that have been used with adolescent populations. Table 1 outlines representative studies along with a brief description of the questionnaires used in each and prevalence rates of online victimization. It begins with the Youth Internet Safety Survey I & II (Finkelhor, Mitchell, & Wolak, 2000; Wolak et al., 2006). This survey was conducted by the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children in collaboration with the Crimes Against Children Research Center and was one of the first telephone surveys of child and adolescent internet use, sexual solicitation, harassment and exposure to unwanted materials online (Finkelhor, Mitchell, & Wolak, 2000; Wolak et al., 2006). Although there are differing definitions of online victimization, many studies through 2007 primarily focused on general or sexual online victimization (Berson, et al, 2002; Finkelhor et al, 2000; Li, 2006). For general online victimization participants experienced derogatory remarks or images and the items either did not assess a specific reason or the questionnaire asked if the victimization was due to appearance or ability. For sexual victimization, items assessed having sexual discussions against the respondents will or being shown unwanted sexual material (Finkelhor, et al, 2000).

Most existing measures either do not assess racial victimization or use one to two items to measure online victimization related to race. The Shariff (2008) questionnaire assesses victimization that can be attributed to race with one item (e.g. called a negative name or harassed because of ethnicity). Other items measure exclusion and threats but, it is unclear whether they are due to a person’s race or ethnicity. The varying types of racial discrimination that have become increasingly prevalent in the past couple of years are not captured in this type of question; this includes the racist images that have circulated online following the racial theme parties that have been thrown across the country and exclusion or threats specifically due to race.

In addition, drawing on previously discussed models of racism and discrimination, a measure is needed that captures both experiences directed at the individual and those experienced vicariously through same race peers and adults. For example, a student doing a report on the Civil Rights Movement may stumble on to the site martinlutherking.org. This site (at the time of writing this article) has disparaging statements about Dr. King that are cloaked as truth. The statements do not necessarily explicitly use racial epithets against Blacks, but it includes countless things that are untrue about Dr. King and Blacks. These statements may be just as hurtful as being called a racial epithet directly. A measure of online victimization should not only include general and sexual victimization but should account for the multiple dimensions of racial discrimination an adolescent may face online.

In addition to neglecting or missing aspects of race-related victimization, early measures cited use a dichotomous response scale in which respondents indicate whether or not they have been victimized by responding yes or no (Finkelhor, et.al., 2000). Other, more recent measures have a 3-point response scale, never, occasionally & often (Shariff, 2008). These responses may potentially make it difficult to determine exactly how often a respondent experiences online victimization because often for one respondent may mean occasionally for another. Even measures such as those used in Li (2006) or Raskauskas & Stoltz (2007) may mask how often a respondent is victimized. For example, they may ask the number of times in the past year victimization has occurred with the highest option being 10 or more times or 16 or more times. If victimization occurs nearly on a daily basis or almost once a month, two respondents might click the same item. To the contrary, these two respondents may be having vastly different experiences. A measure is needed with responses that show the variation in frequency of victimization from never to daily.

The differing prevalence rates of online victimization may be attributed to the fact that questionnaires were developed for specific studies, there are differing definitions in that some respondents are told, for example, the victimization should be repeated (Kowalski & Limber, 2007). There were also different time frames including the past school year (Raskauskas & Stoltz, 2007) the past year (Finkelhor, et. al., 2000), the past couple of months (Kowalski & Limber, 2007; Kowalski, Limber, & Agatson, 2008) or no time frame given.

Despite the fact that measuring online victimization has gotten increasingly more advanced over the years, a multidimensional, comprehensive scale that can be used across studies that is psychometrically sound is needed. This report outlines two studies. In both studies, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses, to investigate the psychometric properties of online victimization. The hypothesized factorial structure of the OVS includes general, sexual, individual and vicarious racial victimization. A secondary aim of these studies was to determine the convergent validity of the OVS by examining associations between the OVS factors and psychological adjustment measures as found with existing online victimization questionnaires and measures of racism related stress.

General Method

The purpose of the following studies is twofold: 1) to conduct confirmatory factor analyses to determine the factor structure of the Online Victimization Scale and 2) to determine whether there is convergent validity between scores on the OVS and theoretically related measures. Three and four factor models will be tested to determine the best fit for the data.

Scale Construction

Drawing on the theoretical framework and items from the Youth Internet Safety Survey I (YISS I; Finkelhor, et al., 2000), the OVS was created. As this questionnaire primarily measures general online victimization, called online harassment in their study, unwanted sexual solicitation, aggressive solicitation and exposure to unwanted sexual material, these types of victimization were also assessed in the OVS. More specifically YISS I asks, for example, “In the past year, did you ever feel worried or threatened because someone was bothering or harassing you online.” This item was adapted for the OVS and specific reasons for being threatened were added: “I have been threatened online because of the way I look, act or dress.” The OVS also assesses whether respondents have been harassed or bothered, but asks specifically if it is for no apparent reason or if it is because of something that happened at school. This is particularly important given that many online incidents begin with problems offline. An item in the YISS I inquires whether “In the past year, did anyone ever use the Internet to threaten or embarrass you by posting or sending messages about you for other people to see.” This item was adapted and shortened for the OVS: “People have posted mean or rude things about me on the internet.”

In terms of the sexual victimization items the YISS I asks respondents “In the past year did you ever open a message or a link in a message that showed you actual pictures of naked people.” The OVS adapts this item and asks “I have received unwanted sexual SPAM, e-mails or messages.” Similarly, the YISS I assesses “In the past year, did anyone on the Internet ever try to get you to talk about sex when you did not want to?” and the OVS asks “People have continued to have sexual discussions with me even after I told them to stop.” The primary difference in terms of the sexual victimization items is in the responses. Respondents for the YISS I are asked to indicate yes or no. The OVS adapts these responses to the victimization experiences and rather than dichotomous responses, it determines whether the experience never happened, happened once, a few times a year, a few times a month, a few times a week or occurs on a daily basis. Another key difference is that the OVS captures a common practice that includes spreading rumors about an individual’s sexual behavior.

Race related items were developed based on theory (e.g. Harrell, 2000), previous studies of race on the Internet (e.g. Tynes, Reynolds, & Greenfield, 2004; Tynes, 2005; Tynes, 2007) and visits to a number of online sites where race is discussed, including hate sites such as stormfront.org and Facebook.

Following the theoretical arguments outlined previously as well as extant literature on online victimization, we posit that victimization will be associated with the most salient aspects of the physical body offline in the following domains: general, sexual, and racial. The general domain includes physical appearance, offline behavior, style of dress & online writing style. The sexual-gender domain includes stereotyping based on gender, sexual solicitation, and risk factors commonly associated with this form of victimization. The racial domain includes racial epithets, images and stereotyping based on race or ethnicity directed at the individual and vicarious experiences by same and cross race peers.

Fifty-four items were originally created in the OVS-Preliminary version of the scale. Four focus groups were then conducted to determine the age-appropriateness of the items and whether content adequately represented online experiences of teens. A total of 20 adolescents ages 14-18 participated in the 4 focus group groups. Seventy five percent were female, 80% were White and 20% were African American. Upon completion of a pencil and paper version of the scale, participants were then asked to review the items and discuss any that should be removed or modified. After incorporating student feedback, the questionnaire’s final form was 51 items, with wording adjusted as participants suggested. Twenty eight items assessed victimization experiences and risk factors for sexual victimization, 12 stress associated with victimization, 3 location of experiences, 4 their worst internet experience and their responses and 4 internet safety.

Study 1

Method

Participants

Participants were 222 students between the ages of 14 and 19 (53% female, mean age = 16.4, SD = 1.3) from three small urban high schools in The Midwest. The self-reported ethnicity of participants was 51% White, 33% African American, 5% Asian, 2% Latino, 2% Indian, 6% biracial, and 1% other. The grade level of the study participants ranged from 9th to 12th (17% 9th grade, 26% 10th grade, 18% 11th grade, 37% 12th grade and 2% unreported). Mother’s highest level of education was elementary 1%, high school 50%, college 34% and graduate school 15%. Father’s highest education level was .elementary 1%, high school 51%, college 35% and graduate school 13%.

Measures

In addition to the OVS, a demographic questionnaire was used. Participants to indicate their school, grade, age, gender, mother’s highest level of education and ethnicity.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from 3 Midwestern US high schools. Researchers introduced the study at high school faculty meetings explaining that little is known about how the Internet may impact academic and mental health outcomes. Teachers were given a script to read verbatim and fliers to hand out to students in their classes. The teachers read the script to their students describing the study as students read the flier. Teachers instructed the students to complete the surveys on their own and without consultation from peers. The fliers included a website address for the study and were complete with instructions on how to log on.

Surveymonkey.com was used as the online survey tool because of its simplicity and user-friendly interface. Students completed the surveys either on school computers during lunch time or afterschool, logging on to the website listed on the flier. Incentives for participation were provided, including a drawing for an Ipod and $5 for each student given directly to the schools. The online survey settings ensured that the participants completed the survey only once. Online assent was obtained from participants prior to participation. Per university Institutional Review Board approval, parent consent was waived to allow participants to freely respond to sensitive questions related to Internet experiences. Participants were assured that they could discontinue the study at any time if they felt discomfort.

Results

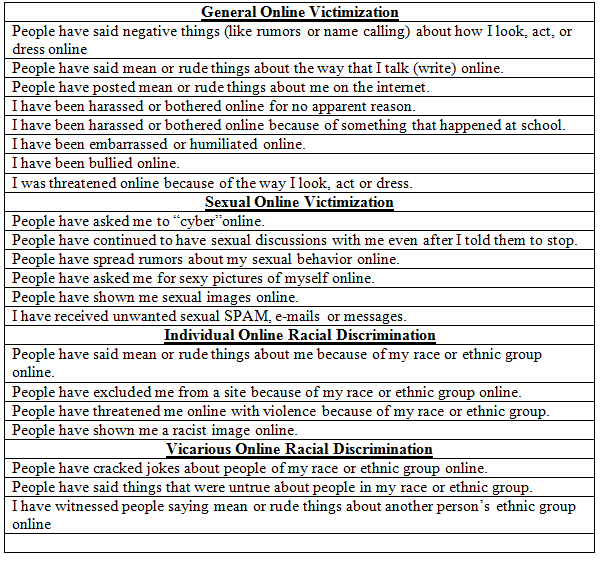

The 28 quantitative items on the OVS included four domains of online victimization (General Victimization, Sexual Victimization, Individual Racial Discrimination, Vicarious Racial Discrimination). These four domains were used to construct the theoretical four-factor online victimization model, which was investigated through a confirmatory factor analytic procedure. However, our preliminary theoretical investigation led to the dismissal of seven of the 28 items because they did not directly relate to the investigated construct. Specifically, items were dismissed from consideration for the sexual victimization construct because they were determined to assess risk factors, not necessarily direct online sexual victimization. Overall, the theoretical four-factor model examined direct general online victimization (8 items), direct sexual online harassment (6 items), direct racial discrimination (4 items) and vicarious racial discrimination (3 items). See Table 2

Theoretical Factors

Online Victimization. The General Online Victimization factor is comprised of an 8-item experiential dimension of general victimization the respondent experienced online. Items addressed personal victimization experienced by the respondent online (e.g. “I have been embarrassed or humiliated online”), whether these experiences resulted from offline interaction (e.g. I have been harassed or bothered online because of something that happened at school), and specific victimization regarding the respondent’s appearance (e.g. “I was threatened online because of the way I look, act, or dress”) or writing style (e.g. People have said negative things (like rumors or name calling) about how I look, act, or dress online). Items also tap into the repeated nature of online victimization (e.g. I have been bullied online). Factor loadings from the subsequent confirmatory factor analytic procedure ranged from .54 to .80 with a Cronbach’s alpha of .84.

Online Sexual Victimization. The Online Sexual Victimization factor is comprised of a 6-item experiential dimension of sexual victimization the respondent experienced online. Items addressed individual sexual victimization directly experienced by the respondent online (e.g., “People have asked me for sexy pictures of myself online”). Factor loadings from the subsequent confirmatory factor analytic procedure ranged from .53 to .70 with a Cronbach's alpha of .76.

IndividualOnline Racial Discrimination. The Individual Online Racial Discrimination factor is comprised of a 4-tiem experiential dimension of racial discrimination the respondent experienced online. Items addressed individual racial discrimination directly experienced by the respondent online (e.g., “People have said mean or rude things about me because of my race or ethnic group online”). Factor loadings from the subsequent confirmatory factor analytic procedure ranged from .53 to .71 with a Cronbach’s Alpha of .66.

Vicarious Online Racial Discrimination. The Vicarious Online Racial Discrimination factor is comprised of a 3-item vicarious experiential dimension of racial discrimination the respondent experienced online. Items addressed vicarious experiences directed at same race and cross race peers witnessed online by the respondent (e.g., “I have witnessed people saying mean or rude things about another person’s ethnic group online”). Factor loadings from the subsequent confirmatory factor analytic procedure ranged from .79 to .89 with a Cronbach’s alpha of .87.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

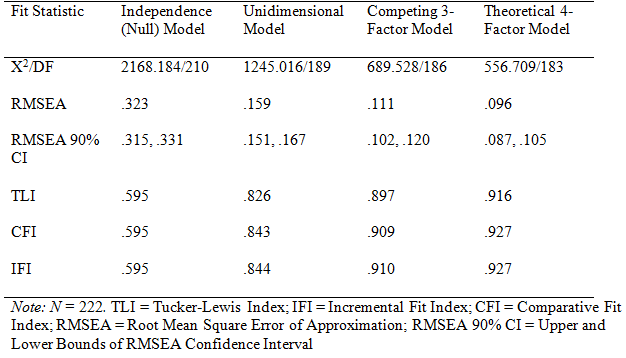

To examine the fit of the theoretical four-factor model, we conducted a maximum-likelihood estimation confirmatory factor analysis in LISREL 8.80 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2007). Additionally, this theoretically based model was compared to a competing three-factor model, a unidimensional model, and the independent (null) model (Bollen & Long, 1993). The competing three-factor model was theory driven, and was comprised of the Online Victimization factor, Online Sexual Victimization factor, and an aggregate Racial Discrimination factor (i.e., Individual Online Racial Discrimination, Vicarious Online Racial Discrimination).

First, we examined the chi-square statistic divided by the degrees of freedom to assess overall model fit. While chi-square is overly sensitive to sample size, it is usually the null-hypothesis significance test (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), and a chi-square/df ratio below 3 is often considered an acceptable fit (Kline, 1998). In addition to the Chi-square statistic, we examined several relative fit indices that may be more appropriate in predicting model fit because they are less reliant on sample size (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Immekus & Maller, 2009). For the current confirmatory factor analysis we used the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) or the Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), where TLI, IFI, and CFI scores greater than .90, are generally considered an acceptable fit of the data (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Pinterits et al., 2009; Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Müller, 2003; Steele et al., 2006). Additionally, RMSEA scores of above .1 are considered a poor fit, between .08 and .1 a mediocre fit, between .05 and .08 an acceptable fit, .01 and .05 a close fit, and .00 an exact fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1992; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Based on the 21 items from the OVS, we examined the theoretical four-factor model against the competing three-factor model, independence model, and unideminsional model, and it was determined that the hypothesized four-factor model demonstrated more acceptable model fit when compared to all other models (see Table 3). As hypothesized, the Independence model (χ2(210) = 2168.184, RMSEA = .323, TLI = .595, CFI = .595, IFI = .595) and the Unidimensional model (χ2(189) = 1245.016, RMSEA = .159, TLI = .826, CFI = .843, IFI = .844) demonstrated poor model fit. Theoretically, however, we hypothesized that the competing three-factor model (χ2(186) = 689.528, RMSEA = .111, TLI = .897, CFI = .909, IFI = .910) and the Theoretical four-factor model (χ2(183) = 556.709, RMSEA = .096, TLI = .916, CFI = .927, IFI = .927) would be relatively similar due to the high correlations between constructs and similarities between the models. This hypothesis was confirmed, however, the theoretical four-factor model demonstrated better model fit (Figure 1), and fell within the acceptable limits of the selected fit indices (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Factor Correlations, Skewness and Kurtosis

As hypothesized, and due to the experiential nature of the victimization experienced by the respondent, all four factors were significantly correlated. While it was hypothesized the four factors, including the error terms, would be correlated, and modeling the correlated residuals may be theoretically appropriate and increase overall model fit (Byrne & Shavelson, 1996), an a priori decision was made to model only individual item residuals. Overall, each of the four factors were significantly correlated with one another (r = .37 - .60, p < .01) and individual correlation statistics are provided in Table 5.

In addition to the correlations, Online victimization, Online Sexual Victimization, Individual Online Racial Discrimination, and Vicarious Online Racial Discrimination were positively skewed (z = 2.49, 3.44, .95, 1.62 respectively). Despite the positive skewness, respondents responses covered the possible Likert-type scale range (1 = Never to 6 = Everyday), indicating that some respondents experience very high and very low levels of victimization. Additionally, it is conceivable to believe that a majority of the respondents would score on the lower end of the scales due to the nature of the experiential items.

Demographic Differences

To assess demographic differences, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted across the four online victimization factors as the dependent variables and gender, ethnicity, and age as the independent variables. An overall MANOVA effect was found for gender (Wilks’ = .91, F(3,150) = 2.75, p < .05, partial 2 = .09), ethnicity (Wilks’ = .72, F(3,150) = 1.66, p < .05, partial 2 = .08), and Age (Wilks’ = .73, F(3,150) = 2.34, p < .01, partial 2 = .07). Univariate analyses for gender revealed a significant difference for general online victimization (F(1,153) = 7.25, p < .01, partial 2 = .06) and individual online racial discrimination (F(1,153) = 1.18, p < .05, partial 2 = .05) where females reported higher scores (M (SE) = 1.77(.11), 1.56(.07)) than males (1.47(.11), 1.49(.08)) respectively. Univariate analyses for ethnicity revealed a significant difference on individual online racial discrimination (F(6,148) = 3.30, p < .01, partial 2 = .14) and vicarious online racial discrimination (F(6,148) = 2.57, p < .05, partial 2 = .11). Tukey Post Hoc tests revealed that Asian Americans (1.78(.15)) and Biracial students (1.93(.16)) experienced significantly more individual online racial discrimination than African Americans (1.33(.08)), and Biracial students experienced significantly more individual online racial discrimination than Whites (1.35(.06)). Additionally, Asian Americans (3.76(.44)) reported significantly more vicarious online racial discrimination than African Americans (1.94(.25)). Finally, univariate analyses for age revealed a significant difference for general online victimization (F(4,149) = 5.64 , p < .01, partial 2 = .16) and individual online racial discrimination (F(4,149) = 6.63, p < .01, partial 2 = .18). Interestingly, the Tukey Post Hoc test only revealed a significant difference between 17 and 18 year olds on individual online racial discrimination, where 17 year olds (1.41(.11)) reported higher rates than 18 year old students (1.32(.11)).

Study 2

Method

Participants

Participants were 254 students between the ages of 14 and 19 (52% female, mean age = 15.9, SD = 1.1) from three Midwestern, United States high schools. The self-reported ethnicity of participants was 52.6% White, 27.5% African American, 4.9% Asian, 3.6% Latino, .4% Native American 7.7% biracial, and 3.2% other. The grade level of the study participants ranged from 9th to 12th (13% 9th grade, 28% 10th grade, 41% 11th grade, 18% 12th grade).

Measures

The Online Victimization Scale is a 21-item measure that assesses online victimization in four domains: general (e.g. I have been bullied online and People have said negative things -like rumors or name calling- about how I look, act, or dress online), sexual (e.g. People have continued to have sexual discussions with me even after I told them to stop) and individual racial discrimination (e.g. People have said mean or rude things about me because of my race or ethnic group online) and vicarious online racial discrimination (e.g. People have cracked jokes about people of my race or ethnic group online.). Responses range from 1=Never to 6=Everyday. The measure is designed to be used on adolescents ages 11-18 in research, clinical and educational settings.

Demographic Questionnaire. Participants to indicate their school, grade, age, gender, mother’s highest level of education and ethnicity.

Psychological Adjustment Measures. To validate the Online Victimization Scale the following measures that have been associated with victimization in offline settings were used. Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1992). This 10-item self-report measure assesses cognitive, affective, and behavioral signs of depression in school-age children and adolescents ages 7-17. Each item is composed of three choices (e.g., I am sad all the time, I am sad every once in a while, I am never sad) and respondents picked one indicate their feelings over the past two weeks (α =.83).

Profile of Mood States-Adolescents (POMS-A, Terry, Lane, Lane & Keohane, 1999). This scale is a shortened version of the POMS, a 65-item measure used on adults. It is a 24-item measure of six mood states of adolescents: anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, tension and vigor. For this study to assess anxiety, four items from the Tension-Anxiety Subscale (α=.75) were used. Each item (e.g., anxious, etc.) is rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely).

The Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSE; Rosenberg, 1965) is a 10-item measure used to assess global self-esteem. Items range from those that would only be endorsed by those with low self-esteem to those endorsed solely by those with high self-esteem (e.g. I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others.). Respondents indicate on a 4-point scale whether they Strongly Agree to Disagree with each of the statement (α=.86).

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS, Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) is a 14-item measure of general distress. Respondents indicate the frequency with which they experience each item. For example, “In the last month how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly.”

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS, Diener, Emmons, Larsen & Griffin, 1985). This scale has 5 items and assesses an individual’s judgments about their overall satisfaction with life. On a 7-point scale, respondents are asked to indicate their agreement (1 = strongly disagree) or disagreement (7 = strongly disagree). Scores range from 5 to 35; higher scores indicate greater life satisfaction.

Results

To further examine the structure of the theoretical four-factor model from Study 1, the confirmatory factor analytic procedure was repeated for Study 2. As in the previous study, 21 items from the OVS were used to create four distinct theoretical factors (Online Victimization, Online Sexual Victimization, Individual Online Racial Discrimination, Vicarious Online Racial Discrimination). Factor loadings and alpha coefficients mirrored the results of Study 1, where loadings for Online Victimization ranged from .47 to .79 (α = .88), Online Sexual Victimization ranged from .50 to .84 (α = .83), Individual Online Racial Discrimination ranged from .64 to .70 (α = .71), and Vicarious Racial Discrimination ranged from .74 to .82 (α = .83).

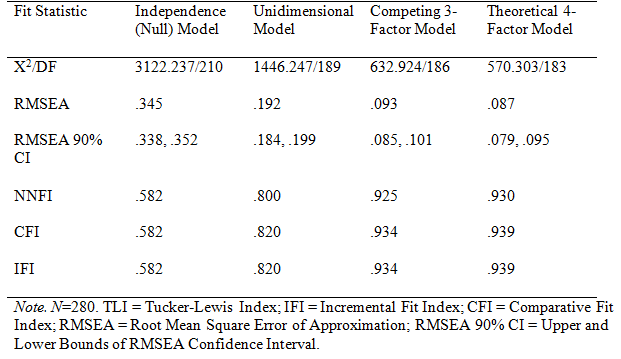

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Staying consistent with Study 1, we conducted a maximum-likelihood estimation confirmatory factor analysis in LISREL 8.80 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2007). Additionally, this theoretically based model was compared to a competing three-factor model, a unidimensional model, and the independent (null) model (Bollen & Long, 1993). The competing three-factor model maintained theoretical integrity, and was comprised of the Online Victimization factor, Online Sexual Victimization factor, and an aggregate Racial Discrimination factor (i.e., Individual Online Racial Discrimination, Vicarious Online Racial Discrimination).

As in Study 1, it was determined that the hypothesized four-factor model demonstrated more acceptable model fit when compared to the independence, unidimensional, and competing three-factor models (see Table 4). As hypothesized, the Independence model (χ2(210) = 3122.237, RMSEA = .345, TLI = .582, CFI = .582, IFI = .582) and the Unidimensional model (χ2(189) = 1446.247, RMSEA = .192, TLI = .800, CFI = .820, IFI = .820) demonstrated poor model fit. Theoretically, however, we hypothesized that the competing three-factor model (χ2(186) = 632.924, RMSEA = .093, TLI = .925, CFI = .934, IFI = .934) and the theoretical four-factor model (χ2(183) = 570.303, RMSEA = .087, TLI = .930, CFI = .939, IFI = .939) would be relatively similar due to the high correlations between constructs, similarities between the models, and the results from Study 1. While this hypothesis was confirmed, and both models are tenable for respondents from Study 2, the theoretical four-factor model demonstrated slightly better model fit (Figure 2), and fell within the acceptable limits of the selected fit indices (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Demographic Differences

Similar to Study 1, we assessed demographic differences using a MANOVA across the four online victimization factors as the dependent variables and gender, race, and age as the independent variables. An overall MANOVA effect was not found for Age (Wilks’ = .90, F(3,232) = 1.31, p > .05, partial 2 = .03). However, a significant MANOVA effect was found for gender (Wilks’ = .94, F(3,232) = 3.08, p < .05, partial 2 = .06) and ethnicity (Wilks’ = .83, F(3,232) = 1.89, p < .01, partial 2 = .05). Univariate analyses for gender revealed a significant difference for individual online racial discrimination (F(1,234) = 10.57, p < .01, partial 2 = .05) where males reported higher scores (M (SE) = 1.58(.08)) than females (1.34(.08). Univariate analyses for ethnicity revealed a significant difference in individual online racial discrimination (F(5,230) = 4.52, p < .01, partial 2 = .10). Due to the sample size discrepancy between racial groupings, post hoc analyses (i.e., Tukey, Scheffe) did not reveal any significant difference between race and the individual online racial discrimination factor.

To extend Study 1 and determine the convergent validity of the theoretical four-factor model, Pearson correlations were performed on the CFA factors from Study 2 and measures of adjustment. As hypothesized, the four factors in the CFA were shown to be significantly correlated with all psychological adjustment measures at the p < .01 level, with the exception of individual online racial discrimination and perceived stress (see Table 3). General victimization, for example, was associated with higher levels of general perceived stress (r=.30, p<.01) as well as increased anxiety (r=.41, p<.01) and depression (r=.29, p<.01). The general victimization subscale was also related to decreased levels of self esteem (r=-.29, p < .01) and satisfaction with life (r=-.34, p<01).

Discussion

Confirmatory factor analyses were conducted to determine the factor structure of the Online Victimization Scale. Four distinct subscales were found: general victimization, sexual harassment, individual racial discrimination, and vicarious racial discrimination. Results showed a good model fit for the data for the four factors that make up the Online Victimization Scale. In addition, to validate the OVS, each of the subscales were compared to measures that have been traditionally associated with victimization in offline and online settings. As expected online victimization subscales were associated with depressive symptomatology, anxiety, perceived stress and decreased self esteem and satisfaction with life.

Although the measurement of online victimization has gotten increasingly more sophisticated through the years (Cassidy, et.al., 2009; Shariff, 2008), inconsistencies in definitions of online victimization, time frame, responses and the fact that questionnaires are created for specific studies have yielded vastly different prevalence rates. For example, just among adolescents in the US, rates of victimization may range from 9.8% to 48% (Hinduja & Patchin, 2009; Raskauskas & Stoltz, 2007; Wang, et.al., 2009). The OVS provides a psychometrically sound measure that can be used across studies. Ultimately, the burgeoning field of new media studies may be able to more systematically study online victimization with the OVS.

In addition, the OVS moves beyond assessment of whether online victimization has occurred and assesses reasons why the experiences occurred, including physical appearance, social status (as evidenced in dress and writing style), and experiences that extend from the school settings. Measures that do provide this level of detail may provide respondents with responses that mask the true frequency of victimization. Moreover, they still may not include varying types of sexual or racial victimization.

The most important contribution the OVS makes to the literature is its focus on racial discrimination in online contexts. Though these racially discriminatory experiences are common online (Tynes et al, 2008), to date, this aspect of online victimization has largely been neglected. When it is assessed it is with 1-2 items that ascertain if respondent has been called a name because of race or ethnicity. This does not account for racist images, cloaked websites, racist jokes and vicarious online racial discrimination. Considering the growing amount of online hate activity since the nomination and election of President Barack Obama in the US (Chen, 2009; Daniels, 2009; Hanna, 2009) and the fact that online racial discrimination is associated with increased anxiety and depressive symptoms (Tynes, et.al., 2008), more scholarly attention should be paid to these domains of online victimization.

Results of this study are consistent with findings using offline measures which have found that racism and racial discrimination are associated with poor health outcomes (Paradies, 2006; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). For example, using the Adolescent Discrimination Distress Index (Fisher, 2000), the authors measured the level of perceived discrimination in 3 contexts: institutional, educational and peer and found that higher levels of discrimination distress in educational and peer contexts were related to lower self esteem. Items in the scale assume face to face contact, and therefore do not account for the racial insults, threats and exclusion that may take place in an individual’s online life. Because the developmental literature indicates that risk associated with negative adjustment outcomes is compounded as youth experience stressors across differing environments (Compas, 1995; Rutter, 1996) a measure that assesses online experiences will help to capture unique experiences and impact of online interaction.

This study is also consistent with questionnaires and measures of online victimization that have found associations with distress and depressive symptoms. For example, 38% of harassed youth have reported being distressed (Ybarra, Mitchell, & Wolak, 2006). In addition , using the Cyberbullying Victimization Scale (Hinduja & Patchin, 2009) a measure of victimization in online contexts such as social network sites, chat rooms and email, researchers found that of the recent victims, 49.5% of females and 44.1% of males felt saddened by the incident and 56% and 50% felt angry. Research using The Problematic Internet Use Scale also found associations with depressive symptoms (Mitchell, Sabina, Finkelhor, & Wells, 2009). The OVS builds on previous questionnaires and measures however, in that it accounts for direct and vicarious race-related victimization experiences. With the creation of the OVS, research at the intersection of Internet Studies, developmental psychology and public health may now use a psychometrically sound measure across studies.

Although recent research has shown differences in victimization based on age and gender, results revealed no differences in this study (Wolak, et.al, 2006). Females and older adolescents have been noted to experience more sexual victimization than their male and younger counterparts. This departure in the literature is attributable to the fact that this sample is generally older than those in other studies. We, for example, did not include any youth below age 14 and the average age of the sample was approximately 16 years of age. This is about the time when victimization is at its height.

Study1 found that Asian American and biracial students experienced significantly more individual online racial discrimination than African Americans and Whites. These findings depart from recent literature that shows no differences in online victimization between racial groups (Hinduja & Patchin, 2009). It should be noted, however, that the sample of Asians and Biracial participants was particularly small however, so findings may not be generalizable to youth across the United States. In addition, the fact that there were no differences in vicarious racial discrimination between Black and White youth or White and Latino youth can be attributed to the scale’s measurement of cross race peer victimization.

A limitation of the measure is that the items do not differentiate between strangers and known peers that commit victimization. Recent research has shown that cyberbullying is overwhelmingly perpetrated by people the victim knows (Hinduja & Patchin, 2009). There is also research focusing differential effects of discrimination based on the race of the perpetrator (Mays & Cochran, 1998). Another limitation is that the items on victimization related to sexual orientation and witnessing others’ general victimization experiences did not fit the final model, though these are important aspects of online victimization. A final limitation is that sexual victimization items should distinguish between whether an adult is asking to meet the person online or a peer and should also determine whether showing the sexual images, etc were unwanted. Future research should address these limitations.

Following the theoretical framework of re-embodiment, this study showed that victimization does occur along the most salient aspects of the offline physical body, including physical appearance and or ability, and the sexual and racial domains. And just as in face-to-face settings victimization has consequences for mental health. Future studies should assess whether online victimization impacts other domains offline including academic performance. As the boundary between online and offline is becoming increasingly blurred and more youth are reporting being victimized because of offline experiences, Internet safety programs should be designed to better equip youth to manage being personally victimized because of their behavior, race or gender.

References

Agatson, P.W., Kowalski, R., & Limber, S. (2007). Students’ perspective on cyberbullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, S59-S60.

Benson, I.R., Berson, M.J., & Ferron, J.M. (2002). Emerging risk of Violence in the Digital Age: Lessons for Educators from an Online Study of Adolescent Girls in the United States. Median: A Middle School Computer Technologies Journal, 5(2), 1-8.

Boler, M. (2002). The new digital cartesianism: Bodies and spaces in online education. In S. Fletcher (Ed.), Philosophy of Education Society (pp. 331–340). Champaign, IL: Philosophy of Education Society.

Boler, M. (2007). Hypes, hopes and actualities: New digital cartesianism and bodies in cyberspace. New Media and Society 9(1), 139–68.

Bollen, K. A., & Long, J. S. (1993). Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods and Research, 21, 230-258.

Burkhalter, M. (1999). Reading race online. In M. Smith & P. Kollock (Eds.), Communities in Cyberspace (pp. 60—75). London: Routledge.

Byrne, B.M., & Shavelson, R.J. (1996). On the structure of social self-concept for pre-, early, and late adolescents: A test of the Shavelson, Hubner, and Stanton (1976) Model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 599-613.

Casssidy, W., Jackson, M., & Brown, K.N. (2009). Sticks and stones can break my bones, but how can pixels hurt me? Students’ experiences with cyber-bullying. School Psychology International, 30, 383-402.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233-255.

Chen, S. (2009). Growing Hate Groups Blame Obama, Economy. Available at: http://www.cnn.com/2009/US/02/26/. Accessed March 15, 2009.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. Journal of Health & Social Behavior, 24(4), 385-396.

Compas, B. E. (1995). Promoting successful coping during adolescence. In M. Rutter (Ed.), Psychosocial Disturbances in Young People: Challenges for Prevention (pp. 247-273). New York: Cambridge University Press. Daniels, J. (2009). Cyber Racism: White Supremacy Online and the New Attack on Civil Rights. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71-75.

Finkelhor, D., Mitchell, K., & Wolak, J.(2000). Online Victimization: A Report on the Nation's Youth (No. 6-00-020). Alexandria, VA, National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

Fisher, C.B., Wallace, S.A., & Fenton, R.E. (2000). Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 679-695.

Gies, L. (2008). How material are cyberbodies: Broadband internet and embodied subjectivity. Crime Media Culture, 4(3), 311-330.

Hanna, J. (2009). Hate Groups Riled Up Researchers Say. Available at: http://www.cnn.com/2009/US/06/11/. Accessed September 25.

Harrell, S.P. (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry,70(1), 42-57.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. (2008). Cyberbullying: An Exploratory Analysis of Factors Related to Offending and Victimization. Deviant Behavior, 29, 1-29.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2009). Bullying Beyond the Schoolyard: Preventing and Responding to Cyberbullying. California, Corwin Press.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55.

Immekus, J. C., & Maller, S. J. (2009). Item parameter invariance of the Kaufman Adolescent and Adult Intelligence Test across male and female samples. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69, 994-1012.

Jöreskog, K., & Sörbom, D. (2007). LISREL 8.80 [computer software]. Chicago: Scientific Software International, Inc.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Kovacs, M. (1992). Children’s Depression Inventory Manual. Tonawanda, NY, Multi-Health Systems.

Kowalski, R.M., & Limber, S.P. (2007). Electronic bullying among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, S22-S30.

Kowalski, R.M. & Limber, S.P., & Agatson, P.W. (2008). Cyberbulling. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing.

Li, Q. (2006). Cyberbullying in schools. A research of gender differences. School Psychology International, 27, 1-14.

Mays, V. M., Cochran, S. D. (1998). Racial discrimination and health outcomes in African Americans. In: Proceedings of the 27th Public Health Conference on Records and Statistics and the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics 47th Annual Symposium. Washington, D.C.: USDHHS.

Mitchell, K.J., Sabina, C, & Finkelhor, D., & Wells, M. (2009). Index of Problematic Online Experiences: Item Characteristics and Correlation with Negative Symptomatology. Cyberberpsychology and Behavior, 12(6), 707-711.

Mitchell, K.J., Ybarra, M., & Finkelhor, D. (2007). The Relative Importance of Online Victimization in Understanding Depression, Delinquency and Substance Use. Child Maltreatment, 12, 314-324.

Paradies Y. (2006). A Systematic Review of Empirical Research on Self-Reported Racism and Health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35, 888-901.

Patchin, J., & Hinduja, S. (2006). Bullies move beyond the schoolyard: A preliminary look at cyberbullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 4, 148-169.

Pinterits, E. J., Poteat, V. P., & Spanierman, L. B. (2009). The White Privilege Attitudes Scale: Development and initial validation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 417-429.

Quintana, S. M., & McKown, C. (2008). Introduction: Race, racism and the developing child. In S. Quintana and C.McKown (Eds.), Handbook of Race, Racism and the Developing Child (pp. 299-316). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Raskauskas, J. & Stoltz, A.D. (2007). Involvement in traditonal and electronic bullying among adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 43(3), 564-575.

Rosenberg, M. (1965) Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press.

Rutter M. (1996). Stress research: Accomplishments and tasks ahead. In: Haggerty RJ, Sherrod LR, Garmezy N et al. (Eds), Stress, Risk, and Resilience in Children and Adolescents: Process, Mechanisms, and Interventions (pp. 354-385). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research, 8, 23-74.

Shariff, S. (2008). Cyber-Bullying: Issues and Solutions for the School, the Classroom and the Home. New York, Routledge.

Smith, M., & Kollock, P. (1999). Introduction. Communities in cyberspace. London: Routledge.

Smith, P.K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett N. (2008). Cyberbullying: it’s nature and impact in secondary pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 376-385.

Steele, R. G., Little, T. D., Ilardi, S. S., Forehand, R., Brody, G. H., & Hunter, H. L. (2006). A confirmatory comparison of the factor structure of the Children’s Depression Inventory between European American and African American youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15, 779-794.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon

Subrahmanyam, K., Greenfield, P., & Tynes, B. (2004). Constructing sexuality and identity in an online teen chat room. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25(6) 651-666.

Terry, P. C., Lane, A. M., Lane, H. J., Keohane, L. (1999). Development and validation of a mood measure for adolescents. Journal of Sports Sciences, 17, 861-872.

Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Tynes, B. (2005). Children, adolescents and the culture of online hate. In D. Singer, N. Dowd & R. Wilson (Eds.), Handbook of Children, Culture and Violence (pp. 267-290).Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Tynes, B. (2007). Role-taking in online “classrooms”: What adolescents are learning about race and ethnicity. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1312-1320.

Tynes, B., Giang, M., Williams, D., & Thompson, G. (2008). Online racial discrimination and psychological adjustment among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43, 565-569.

Wang, J., Iannotti, R.J., & Nansel, T.R. (2009). School bullying among U.S. adolescents: physical, verbal, relational and cyber. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(4), 368-375.

Tynes, B., Reynolds, L., & Greenfield, P.M. (2004). Adolescence, race and ethnicity on the internet: A comparison of discourse in monitored and unmonitored chat rooms. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25(6) 667-684.

Williams, D., & Guerra, N.G. (2007). Prevalence and predictors of internet bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, S14- S21.

Williams, D., & Mohammed, S. (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 20-47.

Wolak, J., Mitchell, K. J., & Finkelhor, D. (2006). Online Victimization: 5 Years Later (No. 07-06-025). Alexandria, VA, National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

Ybarra, M. L. (2004). Linkages between depressive symptomatology and internet harassment among young regular internet users. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7, 247-257.

Ybarra, M., Leaf, P., & Diener-West, M. (2004). Sex differences in youth-reported depressive symptomatology and unwanted internet sexual solicitation. Journal of Medical Informatics Research, 6.

Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2004).Youth engaging in online harassment: Associations with caregiver-child relationships, internet use, and personal characteristics. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 319-336.

Ybarra, M.L., Mitchell, K.J., Wolak, J, & Finkelhor, D. (2006). Examining characteristics and associated distress related to internet harassment: Findings from the Second Youth Internet Safety Survey. Pediatrics,118, 1169-1177.

Ybarra, M.L., Espelage, D.L., & Mitchell, K.J.(2007). The co-occurrence of internet harrasment and unwanted sexual solicitation victimazation and perpetration: Associations with psychosocial indicators. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, S31-S41.

Correspondence to:

Brendesha Tynes

Email:tynes(at)uiuc.edu