Motives for Creating a Private Website and Personality of Personal Homepage Owners in Terms of Extraversion and Heuristic Orientation

David Weibel1, Bartholomäus Wissmath2, Rudolf Groner3Abstract

Keywords: personal homepages, personality, extraversion, cognitive style, heuristics, algorithms.

Introduction

According to Döring (2002), no one’s life is insignificant, no matter where someone is, what he or she does or how old the person is. Ergo, growing numbers of people use the internet to present themselves on personal homepages. Roberts, Foehr, and Rideout (2005) found that in the USA, 32 percent of adolescent internet users provide a personal homepage. Similarly, in German speaking countries—where this study was conducted—millions of individuals create their personal webpage (Schütz & Machilek, 2003) and present private information to the whole world. People make pictures public, provide videos, or write blogs. What are the reasons for such behavior? The purpose of the present study is to answer this question by investigating whether homepage owners differ from the general population in terms of extraversion and heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation as cognitive style.

Extraversion is considered a key variable in the context of new media (cf. Weibel, Wissmath, & Mast, in press). We claim extraversion to be particularly important in the context of homepages, since previous research showed that individuals scoring high on extraversion enjoy social activities and like to share information with others (e.g. Costa & McCrae, 1992). Running a homepage enables one to achieve both needs at the same time. Still, Marcus, Machilek, and Schütz (2006) found homepage owners to be rather introverted. Their findings are, however, somehow confusing (see below). Therefore, one purpose was to investigate this issue again.

A further personality dimension that could be key to understand and predict media usage patterns and digital self-presentation is heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation (Groner & Groner, 1991). One of the central features to classify current media applications is to what extent the user may shape the media environment. Theoretical reasoning (cf. Groner & Groner) suggests that individuals scoring high on heuristic orientation should prefer media offering ample degrees of freedom in design and construction. However, this has not yet been investigated empirically. Therefore, heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation was included as second dependent variable besides extraversion.

Furthermore, we pursue the aim (1) to identify motives for creating a personal homepage and (2) to study whether individuals with certain motives are prone to certain cognitive styles and whether there is a relation between different motives and the degree of extraversion. So far, this has not yet been investigated. Since nowadays, homepages are widely used to write blogs (Guadagno, Okdie, & Eno, 2008), an additional aim was to analyse whether individuals who write blogs differ from those who do not write blogs. To date this question has not yet been answered.

Conceptual Background

Defining the term ”personal homepage”

Weaver (2000) suggests a homepage to be “personal” if it is wholly under the control of individuals. According to Dominick (1999), a personal homepage is as a website, which is designed and maintained “by an individual who may not be affiliated with a larger institution, and contains whatever information the author chooses to be there”. Dillon and Gushrowski (2000) define personal websites as homepages, which provide personal information about people, whereby the content is self-selected. A further definition is provided by Wynn and Katz (1997) who describe personal homepages as autobiographical windows and thereby as a construction of the self. Furthermore, personal homepages can also be described as platforms for individuals to deliberately create an identity, which is presented to others (Vazire & Gosling, 2004). Guadagno et al. (2008) refer to personal homepages as web pages, which are regularly updated and personalized. In this definition blogs are included.

Motivation to build a personal homepage

A personal homepage is a new channel of mass communication (cf. Papacharissi, 2002) which allows people to present almost anything they want in an inexpensive, highly flexible way with a potential world-wide audience. Schütz and Machilek (2003) assume that a personal homepage is a chance for individuals to act as producer instead of consumer of mass communication. Accordingly, Eighmey and McCord (1998) describe people with private webpages as active gratification seekers interacting with media instead of just passively use media contents.

The motives to build a personal homepage were investigated by Papacharissi (2002). In her survey, she came to the conclusion that people design personal homepages to experience entertainment, information, social interaction, self-expression, passing time, professional advancement and because it is a new trend and an alternative way of communication. Another survey in the context of Cyworld mini-homepages—Cyworlds is Korea's dominant social networking site—found that the main reasons are entertainment and self-expression, followed by the professional advancement and passing time (Jung, Youn & McClung, 2007). Jung et al. (2007) conclude that people create own websites because it is enjoying and interesting. A further survey showed that adolescents have personal homepages because they want to learn how to showcase themselves and because they enjoy their own accomplishments (Schmitt, Dayanim, & Matthias, 2008).

Personality of personal homepage owners

Previous studies showed that there are individual differences in Internet use (e.g. Amichai-Hamburger, 2000; Amichai-Hamburger & Ben-Artzi, 2003; Goby, 2006;). Since individuals perceive themselves anonymous in the Internet, their online behavior may differ from their offline behavior. Postmes, Spears, and Lea (2002) suggest that this difference occurs due to depersonalization and deindividuation. Thus, information that is more revealing than homepage owners realize is often provided on personal homepages (Guadagno, Okdie, & Eno, 2008).

Personal homepages have special appeal to persons who are willing to invest time to create and maintain a homepage (Marcus et al., 2006). Furthermore, personal homepages are supposed to be appealing to people with narcistic and exhibitionistic tendencies (Lemay, 1996). Wallace (1999) describes personal webpages as a playground for post-modern personalities and as a place where people can create and experiment with multiple personalities. Marcus et al. (2006) came to the result that compared with the general adult population, web site owner score lower on extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, but higher on openness to experience. The latter finding is in line with the findings of a study by Vazire and Gosling (2004). In the context of blogs, Guadagno et al. (2008) state that personality factors impact the likelihood of being a blogger.

Heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation as a dimension of cognitive style

According to Riding, Glass, and Douglas (1993), a cognitive style can be defined as an individual’s predispositions of recalling, perceiving, organizing, processing, thinking, and problem solving. Within our study we investigate the cognitive style dimension “heuristic versus algorithmic orientation”, which was introduced by Groner and Groner (1991). Their concept is based on the concept of heuristic problem solving which has a long tradition in philosophy as well as in cognitive psychology (for a review of the classic work see Groner, Groner & Bischof , 1983). An algorithm is a sequence of well-defined steps to complete a task or solve a problem in a well-defined task environment (Groner & Groner, 1991; Groner, Groner, & Bischof, 1983). If these steps are accomplished in an appropriate way, the algorithm generates the desired result automatically. In contrast, heuristics are open in the sense that they are not restricted to a specific well-defined task environment and consequently do not guarantee solutions. Heuristics are rather guidelines to solve problems or make decisions and are typically applied when facing complex problems or when information is incomplete. The concept of heuristic versus algorithmic orientation as cognitive style refers to two possible ways to solve a problem (Groner & Groner): (1) a heuristic and (2) an algorithmic way. Algorithmic-oriented people generally try to solve problems by exactly following rules and tend to cope with new situations in a given, well-defined, mechanical, and well-known way. In contrast, heuristic-oriented persons are rather responsive to new problems in a novel way by trying to adapt themselves to the particular situation. Thus, heuristic orientation is characterised by trial and error, own considerations, improvisation, unorthodox procedures, and playful approaches. In contrast, algorithmic persons do not put established approaches into question as long as they work. If this is not the case anymore, they search for a new algorithm.

Introversion vs. extraversion

Introversion-extraversion is defined as the degree to which a person’s basic orientation is turned inward toward the self (introversion) or outward toward the external world (extraversion) (e.g. Cohen & Schmidt, 1979; Costa & McCrae, 1992; Ryckman, 2004). People scoring high on extraversion can be described as sociable, gregarious, and assertive, and they like to share information and interact with others. Furthermore, they prefer occupations that permit them to work directly with other people. In contrast, introverts are more reserved, rather shy, less outgoing and less sociable. They tend to withdraw into themselves. Extraversion vs. introversion is usually understood as continuum (cf. Cohen & Schmidt, 1979).

Hypothesis and research questions

Creating a homepage can be understood as a creative process, which requires problem solving skills (Killoran, 2002). Homepages can principally be created in an algorithmic way by strictly following the tutorial of a homepage provider or by using a programming language (e.g. HTML; Java). This rather refers to an algorithmic than a heuristic way of thinking. However, to achieve the best solution, respectively to create a homepage that represent the intentions of the user, some degree of improvisation and trial and error is usually required. This again refers to heuristic problem solving and may thus be appealing for individuals with a heuristic orientation. Additionally, there are ample degrees of freedom in designing and constructing a homepage. This should also appeal to heuristic oriented individuals. Hence, one purpose of our study is to investigate, whether homepage owners are rather heuristic or algorithmic oriented compared to the general population. This leads us to the first research question:

Research Question 1: Do personal homepages owners have a different cognitive style in terms of heuristic versus algorithmic orientation compared to the general population?

Since an own homepage in an expression of the self within a mass medium, one could expect homepage owners to score high on extraversion. A vast body of research (Costa & McCrae, 1992) showed that individuals scoring high on extraversion enjoy sharing personal information with others and furthermore show an affinity towards social activities. Running personal homepages was found to be a social activity (e.g. Bargh & McKenna, 2004; Papacharissi, 2002; Schütz & Machilek, 2003) and is clearly a way to share information about the self with others. Thus, in the light of previous literature, one would expect operating a homepage may be appealing for extraverted individuals. On the other side, the act of constructing a homepage is a rather solitary and not a very gregarious task. This could indicate that homepage owners are rather introverted. Thus, Goby found that introverts prefer to communicate offline, whereas individuals with more extraversion features tend to communicate online. Accordingly, Marcus et al. (2006) found people with an own homepage to be more introverted than the general population but to score higher on openness to experience. However, this result is somehow surprising because the results of previous research indicate a robust positive correlation between extraversion and openness to experience (for review see Aluja, Garcia, & Garcia, 2003). Thus, the result of the study of Marcus et al. is not conclusive. Therefore, we aim to test the relationship between extraversion and homepage owners once again by answering the following research question:

Research Question 2: Do personal homepages owners score differently on extraversion compared to the general population?

An additional purpose of our study is to explore motives for creating and maintaining a personal homepage. Thereby, we pursue the aim to investigate whether different motives are related to different degrees of heuristic orientation and different degrees of extraversion. This leads us to the research questions three to five:

Research question 3: What are the motives for people to create and maintain a personal homepage?

Research question 4: Are different motives to create a homepage related to a different cognitive style in terms of heuristic versus algorithmic orientation?

Research question 5: Do individuals with different motives score differently on extraversion?

A last purpose was to examine whether those homepage owners who use their homepage to write blogs differ from those who do not write blogs. This leads us to the last two research question.

Research question 6: Do blog writers have a different cognitive style in terms of heuristic versus algorithmic orientation compared to non-blog writers?

Research question 7: Research Question 2: Do blog writers score differently on extraversion compared to non-blog writers?

Method

Sample

To gather our sample, we used the yahoo directory (www.yahoo.de), which is popular in German speaking countries (cf. Schütz & Machilek, 2003). There, we searched for entries under “personal homepages”. Only originally designed homepages, which provided an e-mail address were considered, but not social networking sites. Thereby, we defined a personal homepage as a website, which is operated by a single individual who predominantly presents information about his or her private identity. Homepages, which were created for commercial reasons (e.g. personal fitness coach; music teacher) were not considered. Questionnaires were sent via e-mail to 650 German and Swiss people who operate a personal homepage. We obtained 102 completed questionnaires (response rate = 15.7%). Of these, 33 individuals indicated that they write blogs on their homepage. The average age of the webpage owners was 27.42 years (SD = 10.82) with a range from 13 to 62 years. Eighty percent of the participants were men.

Measuring Instruments

Extraversion and heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation were captured by means of self report, respectively questionnaires.

Heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation.

To measure the cognitive style in terms of heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation, the short form of the heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation scale by Groner and Groner (1991) was used. The scale has been used in several previous studies (Hofmann, 1996; Schuller, 1996; Haller & Courvoisier, in press; Haller, Courvoisier & Cropley, 2010) and consists of 30 items (example items for heuristic orientation “Even though it is possible to get lost, I never look a signposts when I walk through a forest”, “If a tool does not function properly I first try to fix it by myself before bringing it into maintenance”; example items for algorithmic orientation: “If I were a teacher I only would use well established methods of instruction to be sure that I do a proper job”, “I enjoy to do something following exactly a given method in order to avoid too much reflection”). The subjects rated the items on a four-point Likert scale with a value of 0 indicating the lowest amount of heuristic or algorithmic orientation, and 3 the highest. As proposed by the authors, the sum of all items went into the analysis as final score. Thereby, 15 items measuring heuristic orientation were weighted positive (+1), and the 15 items measuring algorithmic orientation were weighted negative (-1). High scores on the negative weighted items mean algorithmic orientation, high scores on the positive weighted items refer to heuristic orientation. Thus, the higher the score summing over all items, the more heuristic is the general orientation. According to the authors, the scale is highly reliable (retest reliability r = .85). In our study, high reliability was revealed for the heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .89). No items were excluded.

Extraversion.

The extraversion-subscale of the German version (Borkenau & Ostendorf, 1993) of the NEO Personality Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1992) was used to assess the participants’ extraversion (example item “I am spontaneous”). The subscale has 12 items and according to the authors, the instrument is reliable (Cronbach’s alpha = .80). The subjects rated the items on a five-point Likert scale with a value of 0 indicating the lowest amount of extraversion and 4 the highest. Finally, the mean score of all items went into the analysis. The extraversion scale turned out to be reliable (Cronbach’s alpha = .79). No items were excluded.

Motives to create an own homepage.

The motivation to create a personal website was assessed with the following open question: “Please name the main motive for creating your personal homepage”. The motives were categorized by means of content analyses. First, different categories were chosen, based on previous research (Jung et al., 2007; Papacharissi, 2002; Schmitt et. al, 2008) as well as on the obtained answers. The categorizations were then carried out by two persons. Interrater-reliability (Cohen’s kappa = .78) indicates “substantial agreement” (Landis & Koch, 1977).

Procedure

The data of our study was compared with the data of the norming samples of the NEO Personality Inventory (Borkenau & Ostendorf, 1993) and the heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation scale (Groner & Groner, 1991). Because these samples were chosen in a way that they represent the general population, we operationalized the general population as the norming samples. The norming sample of the NEO Personality inventory consisted of five distinct age groups (16 to 20 years; 21 to 24 years; 25 to 29 years; 30 to 49 years; 50 to 80 years) with equally distributed gender. The median of the norming sample of the heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation scale is 33 years with a range from 13 to 76 years. The gender is equally distributed. On first sight, the sample of our study and the two norming samples are not comparable: In our study, gender is not equally distributed (more males than females) and the participants of the present study were younger than the individuals of the norming sample. However, previous studies showed neither gender nor age effects for extraversion (Lang, Lüdtke, & Asendorpf, 2001; McCrae et al., 1999) and for heuristic versus algorithmic orientation (Groner & Groner, 1991). Additionally, we neither found an age effect in our study: The correlation between age and heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation (-.05) as well as the correlation between age and extraversion (-.09) were not significant (p > .20). Thus, a comparison between the actual sample and the norming sample is appropriate.

Results

To answer the two first research questions, the data of our study was compared with the data of norming samples of the NEO Personality Inventory (Borkenau & Ostendorf, 1993) and the heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation scale (Groner & Groner, 1991) by means of z tests (The z Test is used to test whether a difference between a sample mean and the population mean is statistical significant. A z Test can only be used if the variance of the population is known.). As mentioned in the methods section, we define the norming sample as general population.

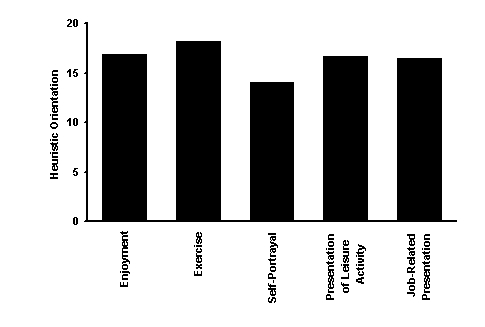

The findings show that the homepage owners scored higher on heuristic orientation (M = 16.44, SD = 9.36) than the general population (M = 11.81, SD = 12.84). This difference is highly significant, z = 3.64, p < .01 (two-tailed), d = .40. Thus, people with an own homepage are rather heuristic oriented compared to the general population. This result is shown in figure 1.

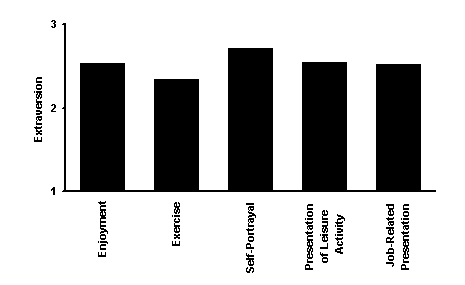

The results concerning the second research question show that homepage owners have higher extraversion scores (M = 2.53, SD = 0.47) than the general population (M = 2.36, SD = 0.57). The difference turned out to be highly significant, z = 3.01, p < .01, d = .31. Figure 2 illustrates this finding

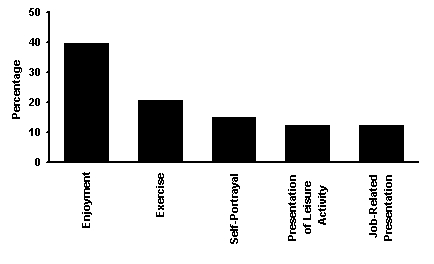

The third research questions concerns the motivation for creating a personal homepage. By means of content analyses, the motives were categorized as follows: enjoyment, exercise, self-portrayal, presentation of leisure activities, and job-related presentation. The majority reported that the main reason for creating a homepage is enjoyment (39.7%) (e.g. “I just like it”), followed by exercise in terms of web design (20.6%) (e.g. “I wanted to learn to know something about web design, that’s why I decided to create my own homepage”), and self-portrayal (15.1%) (e.g. “The main reason is to share my every-day life with colleagues, friends, and everyone who cares”). The rest of the participants constructed and operate a homepage because they want to present their leisure activities (12.3%) (e.g. “I want to document the activities of the choir I attend”) or present their job-related skills (12.3%) (e.g. “It is important to have my CV available online for potential employers”). These findings are illustrated in figure 3.

In order to answer research questions 4 and 5, we analysed whether homepage owners with different motives differ in terms of their heuristic orientation scores and their extraversion scores.

Participants who created a homepage in order to exercise are the most heuristic oriented, followed by participants with the main motives “enjoyment”, “presentation of leisure activity” and “job-related presentations”. Individuals who reported that they had built a homepage to portray themselves scores lowest on heuristic orientation as cognitive style. Statistical analysis showed that only the difference between exercise (M = 18.17, SD = 5.76) and self-portrayal (M = 14.01, SD = 6.40) was significant , t(34) = 2.04, p < .05. Figure 4 shows these findings.

The results for extraversion show that participants who built and maintain a homepage in order portray themselves scored the highest on extraversion, followed by those who use their homepage to present their leisure activity, to enjoy themselves, and to provide their job-related skills. Participants who reported that they had created their homepage to exercise their web design skills scored the lowest on extraversion. Again, only the difference between self-portrayal (M = 2.71, SD = 0.51) and exercise (M = 2.34, SD = 0.44) turned out to be statistically significant, t(34) = 2.33, p < .05. Figure 5 illustrates these results.

To answer the research questions 6 and 7, homepage owners who blog were compared to those who does not write blogs by means of independent t tests. The results reveal no difference in terms of extraversion, t(100) = 0.27, p = 79, as well as no difference in terms of cognitive style, t(100) = 0.15, p = .88.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate personal characteristics of homepage owners and reasons for creating an own homepage. At first sight, languages for programming a homepage may be related to a rather algorithmic way of thinking and problem solving. Nevertheless, we found that personal homepage owners score higher on heuristic orientation than the general population. Though technological advances principally made it possible to create and maintain a website by strictly following the instructions of a provider, the implementation of a personal homepage still seems to be a challenge, which is more likely to be met by highly heuristic oriented individuals. Thus, even when manuals or tutorials are adopted, an optimal solution is not guaranteed. The results suggest that the construction of homepages is thus a rather heuristic process and thus follows a trial and error principle. Therefore, creating a homepage might be more appealing for heuristic oriented individuals. Thus, we can conclude that tasks related to web design might are most suited for users scoring high on heuristic orientation. This is in line with the assumptions of Pahl, Badke-Schaub, and Frankenberger (1999). In a meta-analysis in the context of engineering design, they state that “several investigations revealed a significant correlation between the subjectively perceived problem-solving competence and the eventual quality of the solution achieved”. Thereby, they refer to problem-solving competence in terms of heuristic competence. Building a homepage can also be understood as a design process. Therefore, the relation between heuristic competence and the quality of the solution is also central for the construction of homepages. An additional explanation for the effect could be the fact that the internet is still a relatively new medium and a new realm of self-presentation, which in the first place attracts heuristically oriented individuals.

Taken together, the results for heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation imply that building a homepage requires heuristic problem solving capabilities. An implication of this finding is that manuals to create a homepage are still to be improved so that it gets possible to construct a homepage by means of algorithmic approaches as well (i.e. by just following the rules). Perhaps, when the Internet and personal homepages are wider established and generally accepted guidelines or conventions for digital self-representation emerge, the algorithmic oriented individuals might catch up. Further research should focus on social networks. We assume that social networks are more prone to people with rather algorithmic orientation since opening a facebook account is much easier and offers less degrees of freedom in design and construction than a “traditional” homepage.

Furthermore, we found that homepage owners are more extraverted than the general population. Extraversion can be understood as a tendency of being concerned with obtaining gratifications from what is outside of the self (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Even though, the act of actually creating a homepage is in most cases a solitary activity (cf. Marcus et al., 2006), our findings suggest that owning a personal homepage is an ideal medium to address large audiences—e.g. by writing a blog. Since extraverted individuals are generally turned towards the external world (De Raad, 1998), it seems reasonable that an own website is a form of self-presentation, which is appealing for individuals scoring high on extraversion. However, we did not find different extraversion scores for homepage owners who blog compared to those who do not blog. Thus, it is plausible that another reason account for this difference: Our finding might be because of the fact that extraverted individuals experience interactions with other humans as a gratification (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Terracciano et al., 2005). Since personal websites have been described as a sociable activity (e.g. Bargh & McKenna, 2004), it is plausible that extraverted people more often own a homepage than the general population because of its possibility to interact with others. Our result is contrary to the finding of Marcus et al. (2006) who showed that homepage owners are rather introverted. This difference might have occurred because the understanding of computer usage has changed over the last years. Since computers are increasingly connected they are used more and more to interact in various forms with other humans. Owning a personal homepage might be the pinnacle of addressing large audiences and thus be the realm of extraverts. Introverts, in contrast, might prefer the anonymity of message boards or online games where they adopt a fictional name rather than their real name. As introverts often prefer spending time alone (Ryckman, 2004), they are likely to avoid interactions on the internet. Our results therefore suggest owning a personal homepage to be a form of interaction which is more appealing for users scoring high on extraversion.

Summing up the findings for extraversion, we could show that personal homepages are a manifestation of extraversion in mediated worlds. Vice versa, our study gives deeper insights into extraversion. We now know that individuals with higher extraversion not only like to share information in real world, but also in virtual worlds. This is interesting since this form of interaction is not face-to-face, but still appeals to extraverts. So far, this has not yet been investigated.

The above mentioned findings can be understood more profoundly when the motives to create personal homepages are examined. We found that the main motive for creating a homepage is enjoyment. This in line with the findings of Papacharissi (2002) and Jung et al. (2007). Besides of enjoyment, the most frequently reported motives were exercise in terms of web design, self-portrayal, presentation leisure activity, and presentation of job-related skills. Additional analyses showed that the degree of heuristic orientation and extraversion is dependent on the motive for creating a homepage. Participants who constructed their homepage in order to portray themselves had the highest extraversion scores. The categories enjoyment, presentation of leisure activities, and job-related presentation also seem to particularly appeal to individuals scoring high on extraversion. In contrast, individuals who indicated exercise in terms of web design to be the main motive scored lower on extraversion. Their mean extraversion score was even lower compared to the score of the norming sample. This might a further explanation for the contrary finding of Marcus et al. (2006). Probably, their sample was unbalanced in terms of the participants’ motives. The results moreover show that the motive “excursive” is associated with heuristic orientation. Possibly, creating a homepage is appealing for those individuals because they experience the process of achieving the desired result by means of trial and error or non-orthodox ad-hoc ways as a gratification. In contrast, the scores for heuristic orientation was the lowest—but still higher than in the norming sample—for participants indicating self-portrayal as main motive. For those individuals, not the process itself, but rather the result—i.e. the social interactions due to their homepage—may be the main gratification.

Limitations

There are, however, some limitations concerning this study. First of all, self-selection biases are a common problem with Internet surveys. Thus, it might be that the homepage owners who returned the questionnaire were those individuals with higher extraversion features. This implies that our sample is not necessarily representative for the population of personal webpage owners. Furthermore, the sample is somehow special, since approximately one third of the participants also use their homepage to write blogs. This is surprising since there are applications, which are more popular for blogging than blog on one’s homepage. However, bloggers and non-blogger did not differ in term of extraversion and heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation. Thus, we can conclude that the fact that many of the polled homepage owners use their homepage to write blogs does not account for the difference between homepage owners and the general population. Another problem could be the rather low response rate and the fact that we used directories to gather the sample. It may be that more extraverted homepage owners rather list themselves on a directory. A last limitation lies in the adoption of self-report measures, which might be prone to social desirability or anchoring biases.

Conclusion

Our survey bears three main findings. First of all, we found that personal homepage owners’ personality is different from the general population as their cognitive style is more heuristic. Second, these individuals are more extraverted than the general population. Third, the main motives to create and maintain a personal homepage are enjoyment and self-portrayal, which in turn corroborates the first two findings. The first finding indicates that creating a homepage still rather follows a trial and error principle and is therefore more appealing for people scoring high on heuristic orientation. Since the tendency to communicate with others and to be outgoing is an aspects of extraversion, the second finding lead us to the conclusion that creating a homepage is a process of self-presentation. Thus, it seems that personal homepages are indeed autobiographical windows and a form of interaction and communication. Our finding showing that the extraversion scores were highest for people reporting self-portraying as main motive, support this assumption. On the other hand, ‘exercise’ is the main reason for individuals scoring high a heuristic orientation. This finding seems reasonable since heuristic oriented people like solving problems.

Acknowledgement

This project was supported by a Hans-Sigrist Fellowship grant from the University of Bern.

References

Aluja, A., Garcia, O., & Garcia, L. F. (2003). Relationships among extraversion, openness to experience and sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences, 35, 671–680.

Amichai-Hamburger, Y. (2002). Internet and personality. Computers in Human Behavior, 18, 1–10.

Amichai-Hamburger, Y., & Ben-Artzi, E. (2003). Loneliness and Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 19, 71–80.

Bargh, J., & McKenna, K. (2004). The Internet and Social Life. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 573–590.

Borkenau, P, & Ostendorf, F. (1993). NEO-Fünf-Faktoren Inventar (NEO-FFI) [NEO-Five-Factor-Inventory (NEO-FFI)]. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Cohen, D., & Schmidt, J. P. (1979). Ambiversion: characteristics of midrange responders on the Introversion-Extraversion continuum. Journal of Personality Assessment, 43(5), 514–516.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five Factor Inventory. Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

De Raad, B. (1998). Five big, big five issues: rationale, content, structure, status, and crosscultural assessment. European Psychologist, 3, 113–124.

Dillon, A., & Gushrowski, B. A. (2000). Genres and the Web: Is the personal home page the first uniquely digital genre? Journal of The American Society for Information Science, 51(2), 202–205.

Dominick, J. R. (1999). Who do you think you are? Personal home pages and self-presentation on the World Wide Web. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 76(4), 646–658.

Döring, N. (2002). Personal home pages on the web: a review of research. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 7(3). Available: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/ vol7/issue3/doering.html

Eighmey, J., & McCord, L. (1998). Adding value in the information age: uses and gratifications of sites on the World Wide Web. Journal of Business Research, 41, 187–194.

Goby, V. P. (2006). Personality and online/fffline choices: MBTI profiles and favored communication modes in a Singapore study. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 9(1), 5–13.

Groner R., & Groner M. (1991). Heuristische versus algorithmische Orientierung als Dimension des individuellen kognitiven Stils [heuristic vs. algorithmic orientation as a dimension of cognitive style]. In K. Grawe K, N. Semmer N, & R. Hänni (Eds.), Über die richtige Art, Psychologie zu betreiben (pp. 315–329). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Groner, M., Groner, R., & Bischof, W. F. (1983). Approaches to heuristics: a historical review. In R. Groner, M. Groner, & W. F. Bischof (Eds.), Methods of heuristics (pp. 1–18). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Guadagno, R. E., Okdie, B. M., & Eno, C. A. (2008). Who blogs? Personality predictors of blogging. Computers in Human Behavior, 24, 1993–2004.

Haller, C. S., & Courvoisier, D. S. (in press). Personality and thinking style in different creative domains. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts.

Haller, C. S., Courvoisier, D. S., & Cropley, D. H. (2010). Correlates of creativity among visual art students. The International Journal of Creativity & Problem Solving, 20, 53–71.

Hofmann, H. U. (1996). Heuristische versus algorithmische Orientierung als kognitiver Stil. Eine Untersuchung über die Verhaltenswirksamkeit des individuellen kognitiven Stils bei der Lösung von Mathematikproblemen [Heuristic versus algorithmic orientation as a cognitive style. Effects of the individual cognitive style in solving mathematical problems]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 10(2), 77–84.

Jung, T. J., Youn, H., & McClung, S. (2007). Motivations and self-presentation strategies on Korean-based „cyworld“ weblog format personal homepages. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(1), 24–31.

Killoran, J. B. (2002). Under construction: colonization and synthetic institutionalization of Web space. Computers and Composition, 19(1), 19–37.

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159–174.

Lang, F. R., Lüdtke, O., & Asendorpf, J. (2001). Testgu_te und psychometrische Äquivalenz der deutschen Version des Big Five Inventory (BFI) bei jungen, mittelalten und alten Erwachsenen [Validity and psychometric equivalence of the German version of the Big Five Inventory in young, middle-aged and old adults]. Diagnostica, 47, 111–121.

Lemay, L. (1996). Noch mehr Web Publishing mit HTML [More Web publishing with HTML]. Haar: Markt & Technik.

Marcus, B., Machilek, F., & Schütz, A. (2006). Personality in cyberspace: personal web sites as media for personality expressions and impressions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 1014–1031.

McCrae, R. R., Costa, P. T., Jr., Pedroso de Lima, M., Simoes, A., Ostendorf, F., Angleitner, et al. (1999). Age differences in personality across the adult life span: Parallels in five cultures. Developmental Psychology, 35, 466–477.

Pahl, G., Badke-Schaub, P., & Frankenberger, E. (1999). Résumé of 12 years interdisciplinary empirical studies of engineering design in Germany. Design Studie, 20, 481–494. Papacharissi, Z. (2002). The self online: the utility of personal home pages. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media; 46(3), 346–368.

Postmes, T., Spears, R., & Lea, M. (2002). Intergroup differentiation in computer mediated communication: Effects of depersonalization. Group Dynamics, 6, 3–15.

Riding, R. J., Glass, A., & Douglas, G. (1993). Individual differences in thinking: Cognitive and neurophysiological perspectives. Educational Psychology, 13, 267–279.

Roberts, D. F., Foehr, U. G., & Rideout, V. (2005). Generation M: Media in the lives of 8–18 year-olds. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Ryckman R. (2004). Theories of Personality. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

Schmitt, K. L., Dayanim, S., & Matthias, S. (2008). Personal homepage construction as an expression of social development. Development Psychology, 44(2), 496–506.

Schuller, S. (1996). Concept of heuristic competence with respect to heuristic orientation and categorization. Studia Psychologica, 38, 35–43.

Schütz, A., & Machilek, F. (2003). Who owns a personal home page? A discussion of sampling problems and a strategy based on a search engine. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 62, 121–129.

Terracciano, A., Abdel-Khalek, A. M., Ádám, N., Adamovová, L., Ahn, C.-K., Alansari, B. M. et al. (2005) National character does not reflect mean personality trait levels in 49 cultures. Science, 310, 96–100.

Vazire, S., & Gosling, S. D. (2004). E-Perceptions: Personality impressions based on personal Web sites. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 123-132.

Wallace, P. (1999). The psychology of the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weaver, A. E. (2000). Personal web pages as professional activities: an exploratory study. Reference Services Review, 28(2), 171–177.

Weibel, D., Wissmath, B. & Mast, F. W. (in press). Immersion in mediated environments – the role of personality traits. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking.

Wynn, E., & Katz J. E. (1997). Hyperbole over cyberspace: self-presentation and social boundaries in Internet home pages and discourse. The Information Society, 13, 297-327.

Correspondence to:

David Weibel, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology

University of Bern

Muesmattstrasse 45

CH-3000 Bern 9

Switzerland

Email: david.weibel(at)psy.unibe.ch